Abstract

Background

Hybrid PET/MR imaging has significant potential in cardiology due to its combination of molecular PET imaging and cardiac MR. Multi-tissue-class MR-based attenuation correction (MRAC) is necessary for accurate PET quantification. Moreover, for thoracic PET imaging, respiration is known to lead to misalignments of MRAC and PET data that result in PET artifacts. These factors can be addressed by using multi-echo MR for tissue segmentation and motion-robust or gated acquisitions. However, the combination of these strategies is not routinely available and can be prone to errors. In this study we examine the qualitative and quantitative impacts of multi-class MRAC compared to a more widely available, simple two-class MRAC for cardiac PET/MR.

Methods and Results

In a cohort of patients with cardiac sarcoidosis, we acquired MRAC data using multi-echo radial gradient-echo MR imaging. Water-fat separation was used to produce attenuation maps with up to 4 tissue classes including water-based soft tissue, fat, lung, and background air. Simultaneously acquired 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET data were subsequently reconstructed using each attenuation map separately. PET uptake values were measured in the myocardium and compared between different PET images. The inclusion of lung and subcutaneous fat in the MRAC maps significantly affected the quantification of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose activity in the myocardium but only moderately altered the appearance of the PET image without introduction of image artifacts.

Conclusions

Optimal MRAC for cardiac PET/MR applications should include segmentation of all tissues in combination with compensation for the respiratory-related motion of the heart. Simple two-class MRAC is adequate for qualitative clinical assessment.

Keywords: PET/MR, attenuation correction, MRAC, nuclear cardiology, cardiac sarcoidosis

Summary

In this study we address a particular aspect of MR-based attenuation correction (MRAC) for cardiac PET/MR not previously discussed in the literature. In general, for PET/MR, it is already known that multi-tissue-class MRAC is necessary for accurate PET quantification. Moreover, for thoracic PET imaging, it has been demonstrated that respiration leads to misalignments of MRAC and PET data that result in PET artifacts. These factors can be addressed by using multi-echo MR for tissue segmentation and motion-robust or gated acquisitions. However, the combination of these strategies is not routinely available and can be prone to errors. In this study we examine the qualitative and quantitative impacts of multi-class MRAC compared to a more widely available, simple two-class MRAC for cardiac PET/MR. We demonstrate there is a modest quantitative impact on PET quantification, therefore recommend the use of multi-echo imaging for segmentation of multi-tissue-class MRAC. Conversely, we show that if a quantitative bias is acceptable, qualitative image interpretation is not strongly affected by opting for a simple MRAC alternative, which may be preferable in clinical and clinical research settings where advanced MRAC techniques are not available.

Introduction

Cardiac applications of hybrid positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance (PET/MR) imaging have recently gained much attention due to the ability to combine two important cardiac imaging modalities into a single scan with perfect co-registration between each data set and at lower radiation doses compared to MR plus PET/computed tomography (CT) [1,2].

To accurately reconstruct PET data it is necessary to know the extent to which all tissues in the body attenuate PET photons emanating from the injected PET tracer. In PET/CT, maps of the linear attenuation coefficients (LAC) of the tissues, known as attenuation maps, are obtained from low-dose CTThe attenuation of CT x-ray beams, which is the basis of the CT image, can be converted to attenuation coefficients for the higher-energy PET photons. In PET/MR, including with the Biograph™ mMR system (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) used in this study, MR-based attenuation correction (MRAC) involves estimating attenuation maps by assigning LAC to tissue classes segmented in the MR images. MRAC is routinely performed using segmentation of multi-echo gradient-echo MR images acquired in a breath-hold [3]. Fat and water separation using a 2-point DIXON method [4] is used to segment the major water-containing soft tissue and fat classes in the body. Linear attenuation coefficients are then assigned to the segmented image to estimate the attenuation map. Typically, 3-class attenuation maps are produced, comprising (water-containing) soft tissue, fat, and background air. Further segmentation allows identification of lung tissue (4-class), which has significantly different linear attenuation for PET photons compared to soft tissue and fat. Recent approaches are also applying methods to identify bone (5-class) using ultra-short and zero echo time MRI [5,6], atlas based methods [7] or PET-driven segmentation methods [8].

Attenuation correction based on breath-hold MR has been shown to be unsuited for cardiac applications [9–12]. Variability in the breath-hold position can lead to discordance in the location of the heart between MRAC and PET data acquisition, resulting in artifacts in the reconstructed PET image. A recent study of 18F-sodium fluoride uptake in the coronary arteries demonstrated that breath-hold MRAC resulted in significant artifacts at the liver-lung and heart-lung interfaces, confounding evaluation of the coronary arteries/vessels [9]. This was solved by employing a motion-robust golden-angle radial stack-of-stars trajectory to acquire the MRAC image data during free breathing. The combination of acquisition over several minutes and repeated acquisition of the center of k-space resulted in MRAC data that reflected the average respiratory location of the heart, analogously to the PET data. In that study, attenuation maps were estimated by thresh-holding image intensity into only two classes, comprising 1) all soft tissue including fat and 2) background air plus lungs. Another study used averaged 2D MR imaging to construct a motion-averaged MRAC for cardiac PET perfusion imaging [12], and another has demonstrated prospective gating of radial imaging data to produce MRAC data at the correct respiratory position for PET data [11]. Despite the success of these techniques, the prospective motion gating methodology is not commonly available, and the use of DIXON water-fat separation is prone to fat-water swap errors. While the latter is not very common and may not impede interpretation of the image by the radiologist, these types of errors can have serious but occult downstream consequences for MRAC [13]. An attractive trade-off for robust clinical cardiac PET/MR imaging is the omission of additional water-fat separation at the cost of quantitative accuracy, provided that qualitative integrity of the image is ensured. In previous abstract form, we have explored the relative impact on quantitative PET data of the tissue classes used in the MRAC [14]. In this study we examine in more detail the quantitative impact of such a trade-off. Using a motion-robust MRAC acquisition to eliminate misalignment artifacts, we compare multi-class MRAC with a simple two-class MRAC for PET measurements in the myocardium in a group of patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Importantly, we also examine the qualitative appearance of the PET images, and test the hypothesis that using a simple 2-class MRAC leads to moderate changes in quantitative PET values but without altering the appearance and qualitative interpretation of PET images.

Materials and Methods

Multi-Echo Radial MRAC

A multi-echo stack-of-stars gradient-echo acquisition was used for MRAC. The acquisition employed a data acquisition and reconstruction technique implemented by Benkert et al. [15]. For attenuation correction, a large axial field of view was used to match the acquisition volume of PET data. The field of view was (500 × 500) mm2 and acquired at an isotropic resolution of 3.1 mm. A three-echo approach was used with echo times of 1.84, 3.48, and 5.12 ms. Other sequence parameters were repetition time 10 ms, flip angle 12o, band width 1010 Hz/pix. A total of 384 radial views were acquired in a scan time of 5 min 51 sec. Water and fat images were decomposed using the previously described method [15] based on the signal-phase of the MR image. Attenuation maps were then composed by masking the fat and water images. LACs were assigned to the mask (LACwater = 0.1 cm−1, LACfat = 0.0854 cm−1) [3]. On a slice-by-slice basis, the summation of fat and water components was used as a template to extract lung, which was identified as all remaining dark space within the mask of the body and assigned the LAC of lung (LAClung = 0.0224 cm−1) [3]. All other background pixels outside the body were assigned a LAC value of zero. Attenuation maps had up to four tissue classes: water-containing soft tissue, fat, lung, and background air (Fig 1). For comparison, the standard breath-held DIXON-based MRAC images were also acquired, and the corresponding 4-class attenuation maps were produced automatically by the scanner.

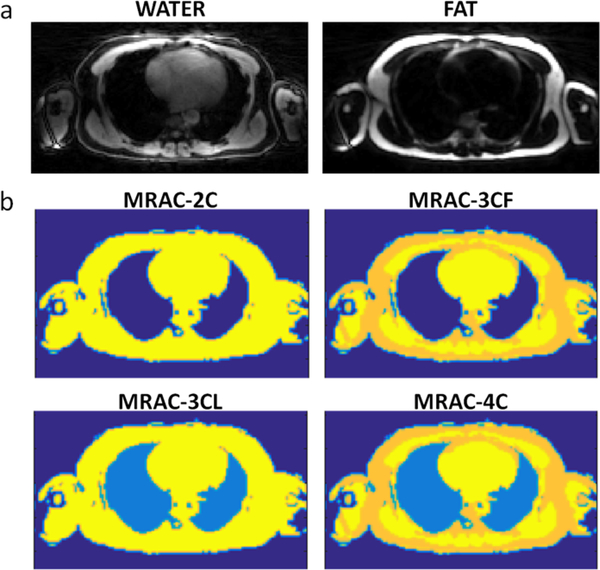

Fig. 1.

a) Water and fat images decomposed from multi-echo radial MR in a slice through the chest including heart and lungs were used to form attenuation maps b) where MRAC-2C is a 2-component attenuation map with the first component including all water-containing soft tissue and fat, and the second component including background air and lung; MRAC-3CF is a 3-component map with water-containing soft tissue, fat, and background (lung set to background air); MRAC-3CL is a 3-component map with water-containing soft tissue (fat set to soft tissue), lung, and background; and MRAC-4C is: a 4-component attenuation map comprising water-containing soft tissue, fat, lung, and background air. The linear attenuation coefficients were, for water-containing soft tissue (yellow) 0.1 cm−1, fat (gold) 0.0854 cm−1, lung (light blue) 0.0224 cm−1 and background air (dark blue) 0 cm−1.

PET Image Reconstruction

PET image reconstruction was carried out offline using research tools (e7 tools, Siemens Healthineers, Knoxville, TN) that are equivalent to those used in online PET reconstructions. The MRAC attenuation maps estimated from multi-echo radial MRAC were inserted into the PET reconstruction in place of the standard breath-hold MRAC attenuation maps. The PET reconstruction employed an ordinary Poisson ordered subsets expectation maximum method with parameters including: 21 subsets, 3 iterations, point-spread function modeling, an image matrix of 344×344×127, and a post-reconstruction Gaussian smoothing with a 2-mm full-width at half maximum. For comparison, an equivalent PET reconstruction performed directly on the scanner was produced using the standard DIXON-based MRAC data.

PET/MR Imaging

PET/MR imaging was performed on the Biograph™ mMR PET/MR system (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). With institutional review board approval and written informed consent, patients undergoing PET/MR to evaluate cardiac sarcoidosis were scanned 30 min after administration of 370 MBq 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) and data were acquired for 60 minutes. The body transmission coil, a flexible 6-channel body array-receiver, and a 6-channel spine array-receiver mounted on the scanner table were used to acquire MR data. For attenuation correction of PET data, only the transmit coil and spine array were included in the attenuation map. Patients were required to have fasted for at least 6 hours and have serum blood glucose levels <200 mg/dL prior to injection of 18F-FDG. Additional MR imaging included standard short-axis cine imaging.

Image Analysis

For each patient, four separate PET images were reconstructed with different attenuation maps segmented from the same MRAC images: 1) MRAC-2C: a 2-component attenuation map with the first component including all water-containing soft tissue and fat, and the second component including background air and lung; 2) MRAC-3CF: a 3-component map with water-containing soft tissue, fat, and background (lung set to background air); 3) MRAC-3CL: a 3-component map with water-containing soft tissue (fat set to soft tissue), lung, and background; and 4) MRAC-4C: a 4-component attenuation map comprising water-containing soft tissue, fat, lung, and background air (Fig. 1).

Qualitative Image Analysis

Firstly, PET images from the standard DIXON-based and multi-echo radial-based MRAC approaches were compared qualitatively for the presence of MRAC-induced artifacts in PET images. Subsequently, to analyze the impact of the different tissue classes included in the MRAC attenuation maps on image interpretation, one blinded reader (VV) assessed the pattern of PET tracer uptake in a mid-ventricular short axis slice for all patients and multi-echo radial-MRAC-type PET images. The uptake pattern was designated as one of: diffuse-symmetrical [more intense diffuse uptake that forms a complete circle in the myocardium], diffuse-asymmetrical [more intense diffuse uptake that is predominantly on one side of the myocardium], focal-on-diffuse-symmetrical [as previously with one or more focally intense region(s)], focal-on-diffuse-asymmetrical [as previously with one or more focally intense region(s)], patchy [more than one focal area on minimally intense uptake in the rest of the myocardium], or focal [one focal area on minimally intense uptake in the rest of the myocardium]. The agreement of the designated uptake pattern was then compared between the different MRAC types for the same patient using the designation of the MRAC-2C PET images as the gold standard with the Cohen kappa statistic.

Quantitative Image Analysis

Myocardial regions of interest were manually drawn in the 17 American Heart Association segments on diastolic short axis MR images. Regions of interest were copied to each fused PET image. Quantitative PET values (standard uptake value – SUVmean and SUVmax) were recorded for each segment. Target to background ratios (TBRmean and TBRmax) were calculated by normalizing SUV to the measured SUVmean of blood in the left ventricle.

Statistics

Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation or as median with interquartile range (25th percentile-75th percentile), as appropriate. To assess the quantitative impact of modified MRAC attenuation maps, two analyses were made. Analysis 1: to establish the quantitative impact of the increased number of tissue segments used in the MRAC attenuation maps, paired t-tests were performed between the PET measurements from different MRAC-type PET images where the two samples comprised all the segments in all patients; paired t-tests were performed between MRAC-2C, as the gold standard, and each of MRAC-3CF, MRAC-3CL, and MRAC-4C. Analysis 2: to establish the relative impact of the attenuation maps on quantitative SUV and TBR PET measurements, i.e. to investigate if TBR measurements are more or less affected than SUV, differences in SUV and TBR between two MRAC-type PET images were compared using a paired t-test. For example, the difference in SUV values between MRAC-3CF and MRAC-2C were found, the equivalent differences for TBR were found, and then a comparison between those differences was made. Values of p < 0.01 were considered significant.

Results

Nine patients [7 male, median age 59, inter-quartile range 57–65] underwent cardiac PET/MR imaging and fulfilled study entry criteria, receiving 359 ± 24 MBq 18F-FDG.

Qualitative Analysis

Comparison of PET images reconstructed using the standard breath-held DIXON and the multi-echo radial-MRAC approaches showed substantial respiratory-related errors in the PET images that used the DIXON MRAC maps. The typical artifact in the PET image, shown in Fig. 2 is the truncation of the lateral wall of the heart caused by the miss-match of the PET and MRAC data. The subsequent qualitative analysis of radial-MRAC types showed only minor differences in the appearance of the PET images reconstructed with different MRAC-type attenuation maps. The semi-quantitative analysis showed agreement in designation in 67% of cases using MRAC-2C as the gold standard. The Cohen kappa statistic for the designation of PET uptake pattern, compared to MRAC-2C, for MRAC-3CF was 0.73, for MRAC-3CL was 0.59, and for MRAC-4C was 0.46 (Table 1). The visual differences tended to alter the SUV levels that led the background to be re-designated, for example, the focal-on-diffuse designation was changed to focal. However, as shown in Fig 3, the effects were subtle, the overall appearance of the PET tracer uptake did not change, and no additional image artifacts were observed.

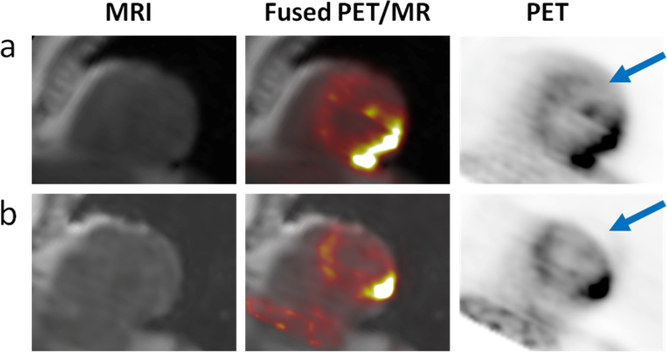

Fig. 2.

The typical respiratory-related artifact can be seen in PET data from the same patient reconstructed with (a) the respiratory motion-robust radial-MRAC and (b) the standard breath-held DIXON-MRAC. When PET images (right) are overlaid on MR images (left), the miss-match in anatomical locations can be observed on the fused images (middle) in this short axis view of the heart. Under breath-hold the diaphragm is often miss-aligned with tidal end-expiration. As the MR images are the basis of the attenuation maps, the subsequent miss-alignment of MRAC and PET data leads to the truncation of the PET data in the later wall (arrows).

Table 1:

Qualitative analysis results

| MRAC type |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient (sex) | MRAC-2C | MRAC-3CL | MRAC-3CF | MRAC-4C | Agrees with MRAC-2C | Disagrees with MRAC-2C |

| 1 (M) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 (F) | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 3 |

| 3 (M) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| 4 (M) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| 5 (F) | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 6 (M) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| 7 (M) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| 8 (M) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| 9 (M) | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

|

| ||||||

| Total | 18 | 9 | ||||

Designation of pattern of PET uptake enumerated as: 1) diffuse-symmetrical, 2) diffuse-asymmetrical, 3) focal-on-diffuse-symmetrical, 4) focal-on-diffuse-asymmetrical, 5) patchy, or 6) focal. Using the designation for MRAC-2C as the gold-standard, the number of the other MRAC-types in agreement or disagreement with the gold standard are totaled on the right.

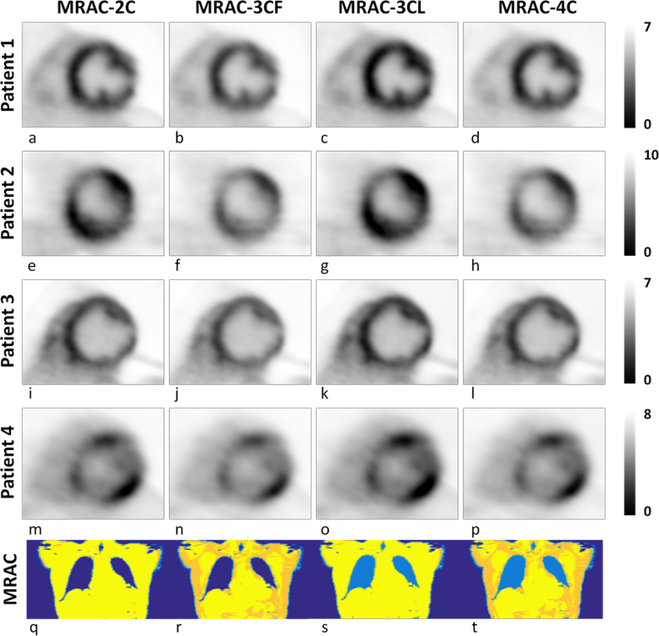

Fig 3.

Mid-ventricle short axis PET images for four patients reconstructed using different MRAC-type attenuation maps. The changes in appearance of the PET images, evaluated by the qualitative image analysis were minor. Patients 1 and 2 were designated differently depending on the MRAC type used: a)-c) Diffuse-symmetrical, d) focal-on-diffuse symmetrical; e) diffuse-asymmetrical, f)-h) focal; Patients 3 and 4 were designated with the same pattern regardless of MRAC-type: i)-l) focal-on-diffuse asymmetrical; m)-p) patchy. Representative (coronal) slices through the respective MRAC maps are also shown (q-t). Color represents linear attenuation coefficient and is segmented into tissue classes: soft tissue (yellow); fat (gold/orange); lung (bright blue); background air (dark blue).

Quantitative Analysis 1

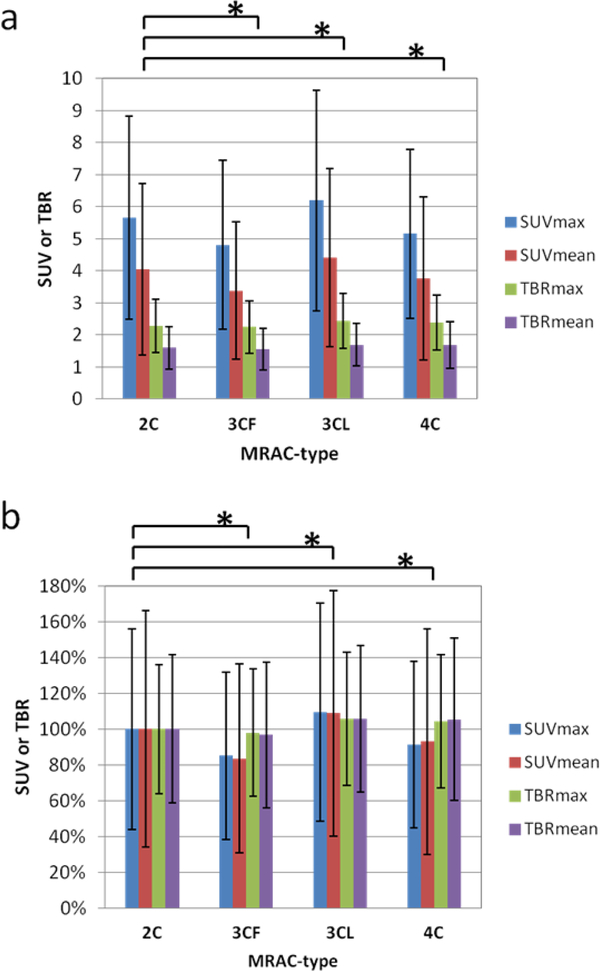

Measured SUV and TBR values differed significantly in PET images reconstructed with different MRAC attenuation maps (Table 2). The mean SUVmax and SUVmean across all segments and patients varied between 4.8–6.2 and 3.4–4.4, respectively, depending on MRAC-type. Mean TBRmax and TBRmean varied between 2.2–2.4 and 1.6–1.7, respectively. The lowest and highest values for both SUV and TBR were found for PET images using the MRAC-3CF and MRAC-3CL attenuation maps, respectively. The biggest differences in SUV compared to values obtained using the MRAC-2C attenuation map were found when using the attenuation map that includes the fat component (Fig 4). Here, the SUVmax and SUVmean were 15% and 16% lower, respectively, than those values when using the MRAC-2C attenuation map. Conversely, large increases in SUVmax and SUVmean of 10% and 9% were found when using the MRAC-3CL attenuation map that incorporates the lung. When adding both fat and lung into the attenuation map using MRAC-4C, the SUVmax and SUVmean values were lower by a more modest 9% and 7%, respectively. For MRAC-4C, whereas SUV values were reduced compared to MRAC-2C, TBR values were slightly increased. The statistical tests of paired values revealed significant differences for all parameters (SUVmax, SUVmean, TBRmax, TBRmean) compared between MRAC-2C and each other MRAC-type (MRAC-3CF, MRAC-3CL, MRAC-4C).

Table 2:

Quantitative SUV and TBR measurements in PET images reconstructed with different MRAC attenuation maps

| Absolute values | Difference from MRAC-2C | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| MRAC type | PET value | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Paired t-test p-value | ||

| MRAC-2C | SUVmax | 5.7 | (100%) | 3.2 | ||||

| SUVmean | 4.1 | (100%) | 2.7 | |||||

| TBRmax | 2.3 | (100%) | 0.8 | |||||

| TBRmean | 1.6 | (100%) | 0.7 | |||||

| MRAC-3CF | SUVmax | 4.8 | (85%) | 2.6 | −0.84 | (−14%) | 0.7 | << 0.01 |

| SUVmean | 3.4 | (84%) | 2.1 | −0.67 | (−16%) | 0.6 | << 0.01 | |

| TBRmax | 2.2 | (98%) | 0.8 | −0.05 | (−4%) | 0.2 | < 0.01 | |

| TBRmean | 1.6 | (97%) | 0.7 | −0.05 | (−2%) | 0.1 | << 0.01 | |

| MRAC-3CL | SUVmax | 6.2 | (110%) | 3.5 | 0.53 | (11%) | 0.5 | << 0.01 |

| SUVmean | 4.4 | (109%) | 2.8 | 0.36 | (12%) | 0.4 | << 0.01 | |

| TBRmax | 2.4 | (109%) | 0.9 | 0.13 | (7%) | 0.2 | << 0.01 | |

| TBRmean | 1.7 | (106%) | 0.7 | 0.09 | (8%) | 0.1 | << 0.01 | |

| MRAC-4C | SUVmax | 5.2 | (91%) | 2.6 | −0.49 | (−5%) | 0.9 | << 0.01 |

| SUVmean | 3.8 | (93%) | 2.6 | −0.29 | (−5%) | 0.6 | << 0.01 | |

| TBRmax | 2.4 | (104%) | 0.9 | 0.10 | (6%) | 0.3 | < 0.01 | |

| TBRmean | 1.7 | (105%) | 0.7 | 0.09 | (7%) | 0.3 | < 0.01 | |

Given are the mean and standard deviation of absolute PET values over all 17 American Heart Association segments and in all patients for each MRAC-type PET image. The mean values are given as a percentage of the corresponding value for MRAC-2C in parentheses. Also given are the mean and standard deviation of the paired differences of each segment’s value between successive MRAC-types and MRAC-2C. Significance p-values are given from the subsequent paired t-test between all 17 American Heart Association segments in all patients for all MRAC-types against MRAC-2C as the gold standard

Fig 4.

SUV and TBR values from Table 2 (a) averaged over all segments measured in all patients in PET images reconstructed with the different MRAC-types. The same values are expressed as a percentage of MRAC-2C values (b). Error bars indicate standard deviation. Asterisk indicates significant paired t-test with p < 0.01.

Quantitative Analysis 2

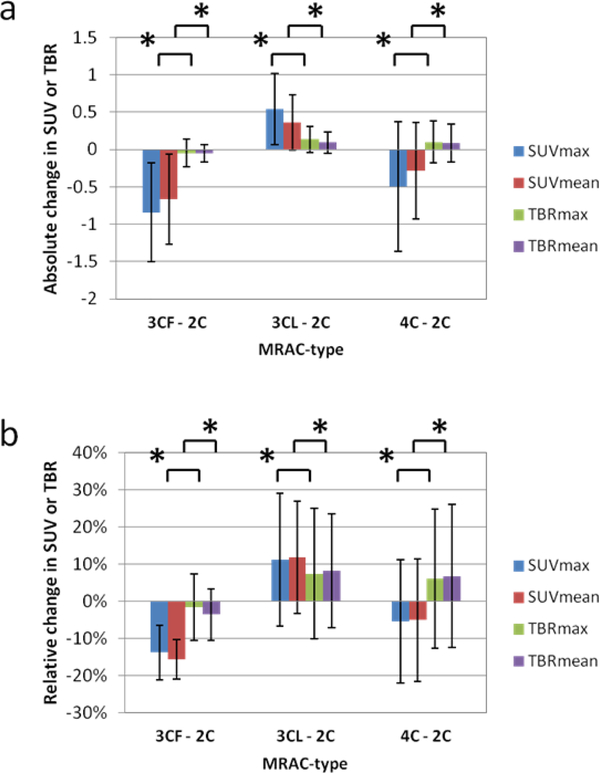

In analysis 2, the differences in PET values between PET images of different MRAC-types were compared between SUV and TBR. Absolute changes in SUV were of a significantly larger magnitude (p < 0.01) than absolute changes in TBR (Fig 5). Fractional changes in SUV were also of a significantly larger magnitude (p < 0.01) than TBR when comparing MRAC-3CF and MRAC-3CL with MRAC-2C, however, for MRAC-4C, SUVmax and SUVmean were reduced by 5% and 5%, respectively, but TBRmax and TBRmean were increased by 6% and 7%.

Fig 5.

Changes in SUV or TBR between PET images reconstructed with different MRAC-types. Absolute changes (a) are larger for SUV than TBR, while the relative changes (b) although larger for SUV than TBR for some MRAC-types (MRAC-3CF) are similar for others (MRAC-3CL and MRAC-4C). Unlike MRAC-3CF and MRAC-3CL, for MRAC-4C the SUV and TBR changes are in opposite directions, decreasing and increasing respectively compared to MRAC-2C. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Asterisk indicates significant paired t-test with p < 0.01 between SUV and TBR.

Discussion

The results of this study have examined how quantitative PET analysis in the myocardium depends significantly on the number of tissue classes segmented on MRAC imaging and used in the attenuation map. The unremarkable visual difference between PET images reconstructed with the different attenuation maps indicates that the segmentation of MRAC images may not have a major impact on qualitative clinical assessment. The semi-quantitative analysis showed moderate to substantial agreement by Cohen’s kappa statistic between the PET images reconstructed with different MRAC-types. However, the subtle re-designations may have significance in some settings. The quantitative analyses showed a significant difference in measured SUV and TBR PET uptake values. The effects of including the lung and fat components in the attenuation map on the measured SUV values were opposite in that inclusion of lung increased the measured SUV whereas inclusion of fat decreased the measured SUV compared to MRAC-2C. This can be attributed to the fact that lung attenuation is under-estimated if assigned as air, and fat attenuation is over-estimated if assigned as soft tissue. The impact of subcutaneous fat may be particularly important as this component is the most variable in quantity across patients. Moreover, the impact of pericardial fat, which is close to the tissue of interest and variable in volume between patients, may have an important impact on tracer quantification in the myocardium and coronary arteries. For pericardial fat the careful segmentation of interlocking tissue classes may be an important consideration. The impact of lung may be confounded by the varying density and attenuation coefficients between patients. These factors need to be investigated further. Lastly, the differences in TBR were generally smaller than those in SUV, owing to the inherent self-normalization by the adjacent blood-pool SUV measurement in a TBR measurement, although not exclusively so.

Whilst changes in SUV values were modest (in the order of 10%), in a research setting where quantitative evaluation is important, MRAC attenuation maps should employ segmentation into the four tissue classes: water-containing soft tissue, fat, lung, and background air[16]. Moreover, these may be of clinical importance, for example in the evaluation of cardiac sarcoidosis with PET/MR systems. Cardiac sarcoidosis is a multi-system condition characterized by granuloma formation, inflammation, and sometimes fibrosis. Recent studies have shown cardiac sarcoidosis to exhibit patchy, mild uptake of 18F-FDG in the myocardium with SUV in the range 2.7–4.6 and average TBR of 2.1 [17]. For diagnostic studies based on uptake thresh-holds and longitudinal studies of changes in inflammation, accurate quantification of the PET signal is of significant importance. Additionally, differences in the MRAC segmentation should be considered when comparing quantitative PET values from different studies.

Multiple authors have investigated the correlation of PET/MR measurements of 18F-FDG uptake in the myocardium using MRAC with gold-standard PET/CT measurements [16,18–21]. The strong correlation between measurements and correspondence of quantitative values has provided validation for cardiac PET/MR. However, these studies focused on comparing PET/MR as a system to PET/CT and did not address the relative impact of the separate tissue components in the standard MRAC attenuation maps, which included water-containing tissue, fat, and lung components; nor did they consider the additional complexity of respiratory motion for cardiac applications. The scope of the current work builds on these earlier comparisons with PET/CT by addressing to what extent, given the use of radial imaging for prevention of motion-related artifacts, we require the additional complexity of segmenting the fat and lung tissue components surrounding the heart in the MRAC map. The results of this study will be of significance for investigators for whom more optimal methods for MRAC for cardiac PET/MR are either not available or when MRAC artifacts may confound reliable imaging.

This study is limited by the lack of an absolute gold standard for quantitative PET values due to lack of additional PET/CT scans in these patients. However, we have demonstrated that segmentation of the tissue classes affects quantitative PET values in the heart. We did not use the standard breath-held DIXON-based MRAC map as a “silver standard” for quantitative analysis owing to the miss-match errors between the MRAC and PET data that we observed in some patients (Fig 2). The presence of such artifact-related errors could induce quantitative differences in the PET images that could mask the tissue-class MRAC-related quantitative differences that we aimed to identify. We infer that 4-class MRAC will prove most accurate in comparison to CT-attenuation correction, as has been demonstrated by the previous evaluations of cardiac PET/MR that used 4-class MRAC in comparison to PET/CT [16]. Moreover, we have not evaluated the impact of the differences in PET quantification on clinical diagnosis. However, the differences found during qualitative evaluation were subtle and qualitatively less remarkable than the pathological differences found in a recent study of cardiac sarcoidosis [17]. A number of additional features in the MRAC maps that were not addressed or optimized could also have a similar impact on quantitative PET values and could be investigated in future studies. The incomplete imaging of the arms, the residual segmentation errors of the fat/water boundaries in the torso, and the omission of bone in the AC map could all play a role. These did not impact the results of this study as these features affected all MRAC maps equally. Finally, this study was not intended to optimize the MRAC acquisition method. Other studies have developed the water-fat separation with radial imaging approach [15] and employed radial MR with faster acquisition time and prospective respiratory motion-gating [11]. Instead, we have addressed previously unreported practical issues of PET quantification in cardiac PET/MR applications.

New Knowledge Gained

This study has provided new knowledge on the relative impact on qualitative and quantitative considerations of using simple or more complex MRAC strategies, specifically for cardiac PET/MR applications. These insights allow the clinical investigator to make informed choices on the imaging protocols for future studies, by providing real-world examples and quantitative analysis.

Conclusions

In summary, this work has demonstrated that the segmentation of fat and lung tissues in the attenuation map significantly affects tracer quantification in the heart by approximately 10%, without substantially altering the qualitative appearance of the images. Whilst qualitative clinical studies may benefit from the wider availability and greater robustness of a simpler MRAC based on 2-class segmentation, in a quantitative clinical and research setting, 4-class MRAC should be employed. The MRAC attenuation map used should be considered when interpreting quantitative cardiac PET data and the impact on clinical diagnosis should be evaluated in a larger cohort of patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL071021.

Abbreviations

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

- MR

Magnetic Resonance

- CT

Computed Tomography

- MRAC

Magnetic Resonance Attenuation Correction

- LAC

Linear Attenuation Coefficient

- 18F-FDG

18F-fluorodexyglucose

- SUVmean/SUVmax

Standard Uptake Value, mean SUV within a region, maximum SUV within a region

- TBRmean/SUVmax

Target to Background Ratio, mean TBR within a region, maximum TBR within a region

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robson PM, Dey D, Newby DE, Berman D, Li D, Fayad ZA, et al. MR/PET Imaging of the Cardiovascular System. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:1165–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schindler TH. Cardiovascular PET/MR imaging: Quo Vadis? J Nucl Cardiol Off Publ Am Soc Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:1007–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Möller A, Souvatzoglou M, Delso G, Bundschuh RA, Chefd’hotel C, Ziegler SI, et al. Tissue classification as a potential approach for attenuation correction in whole-body PET/MRI: evaluation with PET/CT data. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2009;50:520–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon WT. Simple proton spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 1984;153:189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leynes AP, Yang J, Shanbhag DD, Kaushik SS, Seo Y, Hope TA, et al. Hybrid ZTE/Dixon MR-based attenuation correction for quantitative uptake estimation of pelvic lesions in PET/MRI. Med Phys. 2017;44:902–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aasheim LB, Karlberg A, Goa PE, Håberg A, Sørhaug S, Fagerli U-M, et al. PET/MR brain imaging: evaluation of clinical UTE-based attenuation correction. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:1439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofmann M, Bezrukov I, Mantlik F, Aschoff P, Steinke F, Beyer T, et al. MRI-based attenuation correction for whole-body PET/MRI: quantitative evaluation of segmentation- and atlas-based methods. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2011;52:1392–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karakatsanis N, Abgral R, Trivieri MG, Dweck MR, Robson PM, Calcagno C, et al. Hybrid PET- and MR-driven attenuation correction for enhanced 18F-NaF and 18F-FDG quantification in cardiovascular PET/MR imaging” J. Nucl. Cardiol (2019) 10.1007/s12350-019-01928-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robson PM, Dweck MR, Trivieri MG, Abgral R, Karakatsanis NA, Contreras J, et al. Coronary Artery PET/MR Imaging: Feasibility, Limitations, and Solutions. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lassen ML, Rasul S, Beitzke D, Stelzmüller M-E, Cal-Gonzalez J, Hacker M, et al. Assessment of attenuation correction for myocardial PET imaging using combined PET/MRI. J Nucl Cardiol Off Publ Am Soc Nucl Cardiol 2017; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolbitsch C, Neji R, Fenchel M, Mallia A, Marsden P, Schaeffter T. Respiratory-resolved MR-based attenuation correction for motion-compensated cardiac PET-MR. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63:135008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ai H, Pan T. Feasibility of using respiration-averaged MR images for attenuation correction of cardiac PET/MR imaging. J Appl Clin Med Phys Am Coll Med Phys. 2015;16:5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ladefoged CN, Hansen AE, Keller SH, Holm S, Law I, Beyer T, et al. Impact of incorrect tissue classification in Dixon-based MR-AC: fat-water tissue inversion. EJNMMI Phys. 2014;1:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karakatsanis N, Robson P, Dweck M, Abgral R, Trivieri M, Sanz J, et al. MR-based attenuation correction in cardiovascular PET/MR imaging: challenges and practical solutions for cardiorespiratory motion and tissue class segmentation. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:452–452. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benkert T, Feng L, Sodickson DK, Chandarana H, Block KT. Free-breathing volumetric fat/water separation by combining radial sampling, compressed sensing, and parallel imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78:565–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau JMC, Laforest R, Sotoudeh H, Nie X, Sharma S, McConathy J, et al. Evaluation of attenuation correction in cardiac PET using PET/MR. J Nucl Cardiol Off Publ Am Soc Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:839–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dweck MR, Abgral R, Trivieri MG, Robson PM, Karakatsanis N, Mani V, et al. Hybrid Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Positron Emission Tomography With Fluorodeoxyglucose to Diagnose Active Cardiac Sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kershah S, Partovi S, Traughber BJ, Muzic RF, Schluchter MD, O’Donnell JK, et al. Comparison of standardized uptake values in normal structures between PET/CT and PET/MRI in an oncology patient population. Mol Imaging Biol MIB Off Publ Acad Mol Imaging. 2013;15:776–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oldan JD, Shah SN, Brunken RC, DiFilippo FP, Obuchowski NA, Bolen MA. Do myocardial PET-MR and PET-CT FDG images provide comparable information? J Nucl Cardiol Off Publ Am Soc Nucl Cardiol. 2016;23:1102–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vontobel J, Liga R, Possner M, Clerc OF, Mikulicic F, Veit-Haibach P, et al. MR-based attenuation correction for cardiac FDG PET on a hybrid PET/MRI scanner: comparison with standard CT attenuation correction. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:1574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nensa F, Poeppel TD, Beiderwellen K, Schelhorn J, Mahabadi AA, Erbel R, et al. Hybrid PET/MR imaging of the heart: feasibility and initial results. Radiology. 2013;268:366–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.