SUMMARY

The ability to anticipate and flexibly plan for the future is critical for achieving goal-directed outcomes. Extant data suggest that neural and cognitive stress mechanisms may disrupt memory retrieval and restrict prospective planning, with deleterious impacts on behavior. Here, we examined whether and how acute psychological stress influences goal-directed navigational planning and efficient, flexible behavior. Our methods combined fMRI, neuroendocrinology, and machine-learning with a virtual navigation planning task. Human participants were trained to navigate familiar paths in virtual environments, and then (concurrent with fMRI) performed a planning and navigation task that could be most efficiently solved by taking novel shortcut paths. Strikingly, relative to non-stressed control participants, participants who performed the planning task under experimentally induced acute psychological stress demonstrated 1) disrupted neural activity critical for mnemonic retrieval and mental simulation, and 2) reduced traversal of shortcuts and greater reliance on familiar paths. These neural and behavioral changes under psychological stress were tied to evidence for disrupted neural replay of memory for future locations in the spatial environment, providing mechanistic insight into why and how stress can alter planning and foster inefficient behavior.

In Brief:

Brown et al. find neural replay of environment memories during route planning, which tracks subsequent navigation behavior. Critically, stress disrupts memory and cognitive control during route planning, restricting neural simulation of future routes and biasing people away from planning efficient shortcuts in favor of familiar routes.

INTRODUCTION

The ability to prospect, anticipate, and flexibly plan for the future is critical for achieving beneficial health, educational, social, and financial life outcomes. Successful prospective planning is thought to rely, in part, on episodic memory retrieval mechanisms. Unfortunately, in many real-world settings, the ability to retrieve may be negatively influenced by stress. As a result, the ability to engage in prospective planning may be restricted, with a deleterious impact on the efficiency of behavior that depends on memory and planning. Spatial navigation is a ubiquitous real-world activity in which prior experience within a context informs prospection and planning of future actions. The present study examined whether, and how, acute psychological stress influences the cognitive and neural mechanisms underlying navigational planning and flexible behavior.

To construct detailed prospective simulations and actively plan, one must access memories of prior experiences and knowledge [1,2]. Lesion data indicate that the medial temporal lobe (MTL), long known to be critical for memories about past events, is necessary for engaging in both episodic and semantic prospection about the future [3–5] – theory holds that prospection is a constructive process, making use of the declarative memory system to flexibly draw upon and re-combine semantic knowledge (such as a well-learned environmental map structure [6]) as well as relevant details from specific episodes. The hippocampus subserves episodic and prospective retrieval of goal-relevant spatial sequences in rodents and humans [7–13], and behavioral studies of route planning [14,15] and magnetoencephalography research on non-spatial memory replay [16] in humans provide strong support for temporally compressed and constructive memory processes. More broadly, functional MRI (fMRI) studies indicate that imagining future events activates a characteristic network of MTL, prefrontal, and parietal brain areas involved in remembering past knowledge [2].

Distinct representations of different routes during planning may be instantiated from memory via functional interactions between the hippocampus and rostrolateral prefrontal cortex [10,17] (i.e., frontopolar cortex; FPC). Recent theoretical models [18] propose this circuitry could enable processes such as path simulation of alternate routes and setting of sub-goals. FPC has been implicated in active maintenance of longer term goals [19], higher level control demands [20], controlled episodic retrieval attempts [21–24], and exploratory decision making [25]. Regions of the FPC associated with navigational planning [10,17] are a component of the frontoparietal cognitive control network (CCN). The CCN is known to play a critical role in successful recollection and memory-guided decision making. Control systems in frontoparietal cortex guide recollection, particularly when retrieval is more effortful, such as when the presented cues are insufficient to constrain or complete hippocampal memory traces and/or when competing memories or alternative choices interfere with retrieval [24,26–29], as may be frequently the case in complex navigational scenarios [30]. Consequently, our prior navigation work as well as the broader memory literature suggest the CCN may play a role in prospective, goal-directed decision making and planning [31,32], particularly when such planning is guided by information retrieved from memory [33]. Although our prior work implicates the hippocampus and FPC in prospective familiar route retrieval [17], no work to date has directly mapped the function of these regions in humans to (a) flexible, prospective cortical reinstatement of features of an environment – a core predicted mechanism for route simulation or (b) simulation of novel routes and associated selection of different navigational paths (indeed, to date even evidence from direct neural recordings in rodents linking replay to ultimate route decisions is mixed [34]). To preface our results, the present study is the first, to our knowledge, to establish a clear mechanistic link to memory replay, and to in turn examine whether stress disrupts this network and its mechanisms during planning, impacting prospection over navigational goals and decreasing the efficiency of subsequent navigation. Extant data also suggest that memory retrieval effects are strongest in the left hemisphere, particularly in posterior regions and the CCN [35,36], while conversely our navigation work has highlighted the right prefrontal CCN in planning and decision-making processes [17]. It was therefore also of interest to address whether there are laterality effects in stress-related disruption of control for navigational planning.

Prior data indicate that psychological stress in humans impairs episodic retrieval in a non-spatial task [37] via disruption of the hippocampus and frontoparietal CCN. Acute stress tends to impair the probability and accuracy of memory retrieval in humans and rodents [37–41], putatively as a result of (a) glucocorticoids disrupting MTL function [42] and (b) a rapid sympathetic nervous system response[43] that can shift information processing toward increased bottom-up stimulus processing while attenuating top-down control [44] and transiently impairing prefrontal function [45–49]. Additionally, distractors such as time pressure have been shown to decrease reliance on map-based navigational strategies and impair navigation [50], suggesting that a concurrent stressor may divert attention and control away from the navigation task. Other evidence suggests that when stressed, the substrates of behavior often shift from flexible, MTL-dependent “declarative” memories to less cognitively demanding, striatal-dependent “habitual” memories [38,51], or potentially from exploratory to exploitative cognitive strategies [52,53]. A clear prediction from the above human and animal data is that these neurocognitive shifts under acute stress impact the ability to flexibly leverage declarative memories for prospective simulation, and reduce efficient and novel shortcut taking, as cognition becomes restricted to execution of familiar and rote behaviors.

The present study brings the above theoretical framing together to test whether (a) decisions between novel and familiar routes are linked to differential prospective neural simulation of the alternatives, (b) prospective simulation and future route choice are tied to engagement of the hippocampus and goal-directed cognitive control machinery, and (c) stress disrupts the hippocampal and control machinery needed for planning, consequently altering simulation of novel experiences and ensuing behavior. We hypothesized that acute stress impairs hippocampal and frontoparietal function, leading to less complex and more spatially restricted prospection, and thus a greater dependence on previously learned (i.e., familiar) behavior. Using a city-environment-like spatial navigation task (Figure 1A), we asked whether anticipatory stress decreases recruitment of hippocampal mnemonic and frontoparietal control networks prior to active navigation when participants were held in place and given an opportunity to plan (if they chose/were able) a novel shortcut to the location of a well-learned goal object (Figure 1B; 8s Goal cue period). To the extent that stress restricts the scope of prospection, we could also ask whether prospection-related memory replay during this period (indexed by cortical reinstatement for item/object representations from memory of the environment [37]) become biased away from long-term goals (e.g., object B in Figure 1B). We then asked whether stress-related planning disruptions reduce the efficiency of subsequent navigation, by driving an increased reliance on inflexible, familiar behavior.

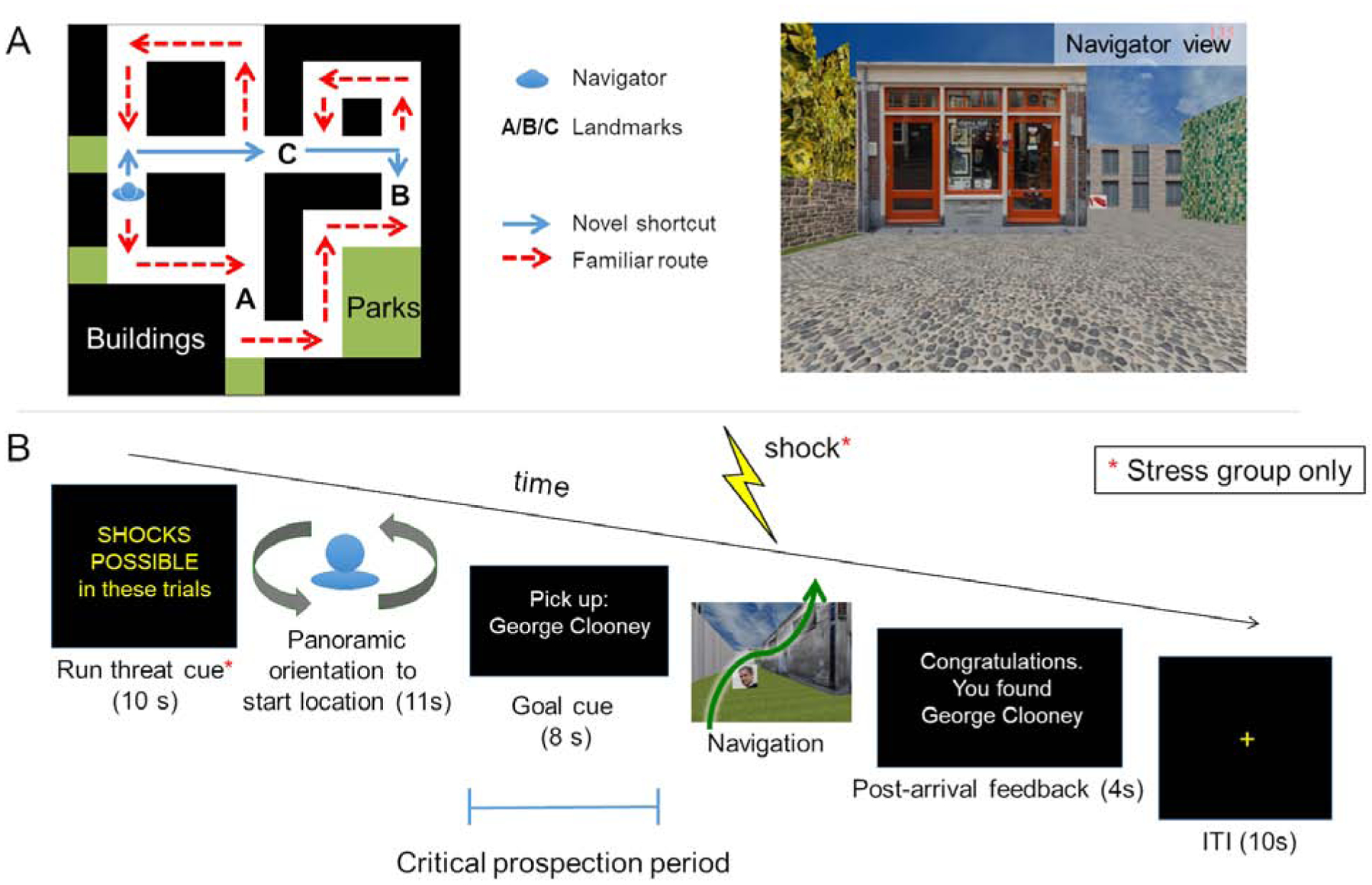

Figure 1. Task overview.

(A) Topographical view of one of 12 virtual city environments. On Days 1 and 2, participants over-learned a familiar route (red line) through each environment. Each environment contained buildings, parks, fences, trees, and three unique goal landmark objects (images of famous faces, fruits/vegetables, animals, or tools displayed on boxes along the familiar route). On Day 3, participants were first asked to repeat navigation of each familiar route once more during fMRI (Familiar route trials, beginning and ending at a pseudo-randomly placed finish line). Then, during Probe trials they were placed along the familiar route (blue character), and asked to navigate as quickly as possible to a goal [B] within that environment. Critically, while participants were not informed that shortcuts exist, each environment was designed such that a novel shortcut (blue line) provided the most efficient route to the goal from the Probe-trial start location. As such, participants could navigate to the goal by taking the familiar route (which would take longer) or by flexibly drawing on memory to plan and take a shortcut. Participants were not informed of these alternative strategies. (B) Day 3 fMRI Probe trial structure. At the outset of each scanning run, stress group participants were given a reminder that they would be under threat of shock throughout the run (Day 3 Familiar route trials were also performed under threat). On each Probe trial, they were oriented to their start location, then presented the name of a landmark object as a goal and held in place for 8s, with the environment hidden from view. During this period, participants could plan how to get to the goal, if they freely chose/had the cognitive bandwidth to do so. This prospective planning period was the target of our fMRI analyses. Participants were then allowed to freely navigate to the goal to end the trial. Stress participants performed the entirety of these trials under anticipatory stress (see STAR Methods).

Over training (Days 1–2), 38 participants developed knowledge of multiple environments outside the scanner, over-learning one pre-determined (familiar) route through each environment along with the locations of goal landmark objects within the environment. Critical to our aims, side streets leading from the familiar routes provided an opportunity for participants to leverage spatial memory to flexibly generate novel shortcuts between locations during an fMRI Probe task on Day 3 (Figure 1B). We examined how acute anticipatory stress affects the neural mechanisms underlying goal-directed prospection and subsequent navigation by assigning participants at the start of Day 3 to either a stress-manipulated group (threat of shock) or a non-stress control group.

We predicted that successful, efficient performance on novel goal trials would be guided by prospection: a combination of (a) flexible hippocampal-dependent retrieval of spatial relationships in the environment, in lieu of inflexible reliance on a learned route, and (b) cognitive control mechanisms, particularly in right FPC, which are thought to support simulation and selection over alternative paths [10,17,18]. To the extent that hippocampal and prefrontal mechanisms are disrupted under stress, we predicted that stress participants would show reduced activity in these brain regions during planning navigation to a novel goal. To the extent that memory retrieval is impaired, we further predicted reduced cortical evidence for goal memory reinstatement. Finally, we hypothesized that disrupted planning would have a direct impact on behavior, such that stress participants would be less likely to devise and take efficient shortcut routes to novel goals, instead resorting to more familiar, but inefficient, routes.

RESULTS

To examine the effects of stress on behavioral and neural manifestations of prospective navigation, we conducted four types of analyses: 1) manipulation checks validating stress induction; 2) behavioral analyses validating successful learning of the trained paths through environments and demonstrating the behavioral ramifications of acute psychological stress on navigation phase (Figure 1B) efficiency; 3) planning phase (Goal cue, Figure 1B) univariate fMRI analyses targeting a priori hippocampal, FPC, and broader CCN ROIs; and 4) multivariate fMRI pattern analyses probing whether stress alters memory reinstatement during novel route planning.

Manipulation checks

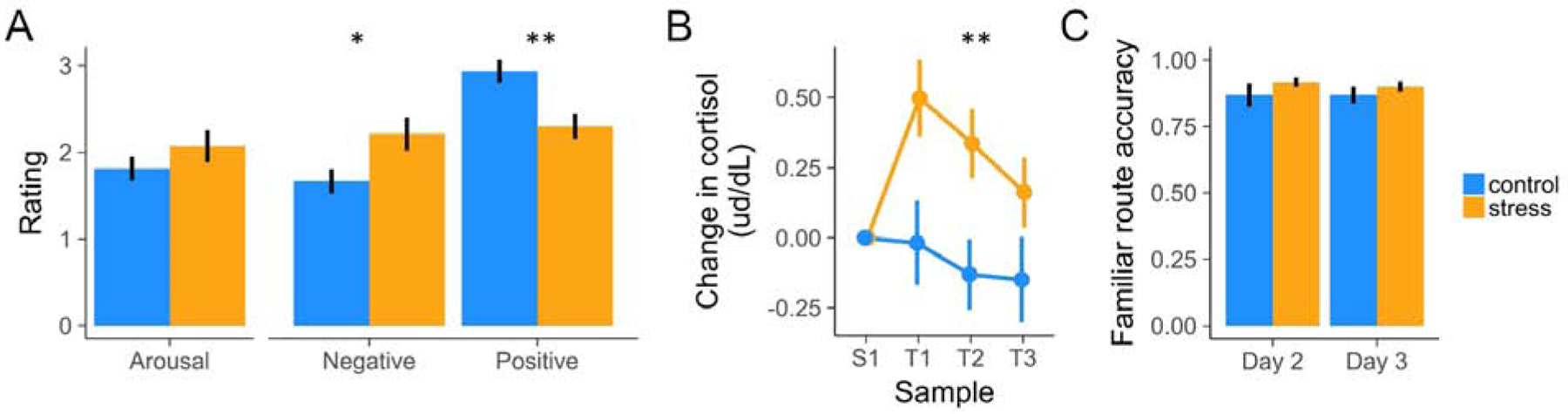

Stress participants reported feeling significantly more negative (anxious, stressed) and less positive (happy, safe) than controls during the fMRI-scanned navigation task (Figure 2A; t(76)=3.85, p<0.001), as well as in retrospective ratings post-scan (see Supplement for details). Salivary cortisol was assayed at baseline (S1 – collected on Day 2, when participants were naïve to their subsequent group assignment) and T1–T3 (at the start, midpoint, and end of the Day 3 fMRI Probe trials). As predicted, cortisol levels at S1 did not significantly differ across groups (t(36)=1.17, p>0.1). Importantly, baseline-corrected cortisol levels for our MRI sample were significantly higher in the stress group during the scanner task (Figure 2B; overall T1–T3: t(33)=2.87, p<0.01, becoming marginal by the end of the experiment [T3: t(33)=1.88, p=0.07 – Bayes factor (BF)=1.3, indicating weakly greater likelihood for H1 vs H0]).

Figure 2. Manipulation Checks.

(A) Stress increased subjective ratings of negative valence and decreased ratings of positive valence. (B) Stress increased cortisol levels throughout the Day 3 scan session. (C) Control and stress participants navigated the familiar routes with similar accuracy by the end of the last day of training (Day 2) and during fMRI task performance (Day 3). For subsequent Probe-trial behavioral analyses, we excluded environments on which participants did not accurately follow the familiar route by the end of training. Error bars indicate within-participant standard error of the mean. See also Table S1 and Table S2.

Behavioral results

Training and Familiar route task performance

We confirmed that participants successfully learned the goal landmark objects in each environment, along with the familiar paths. Performance on a goal landmark object recall task was assessed over the course of training (Days 1 and 2) and at the end of the fMRI session (Day 3). During object recall, participants were presented images of each environment and asked to recall the three objects situated in the environment (see Methods). Landmark object recall accuracy increased across training to 90% and remained at ceiling (91.5%) when assessed post-scanning. Object recall accuracy was not strongly modulated by any object category (z=−0.59, p=0.55; z=1.61, p=0.11; z=−0.66, p=0.51) or group (stress/control) (z=0.57, p=0.57), no category modulated group effects (z=1.07, p=0.28; z=1.01, p=0.31; z=−1.57, p=0.12), and there was no clear group × day interaction (z=−1.57, p=0.12).

Critically, assessment of end-of-training and fMRI scan-period knowledge of the familiar routes (Figure 1A Familiar trials; Methods) revealed that they were equally well-learned by the stress and control groups. Specifically, Familiar route navigation performance did not differ by group (z=−0.11, p=0.91), by day (end of Day 2 training vs. Day 3 when stress participants were under threat) (z=−0.81, p=0.42), and there was no group × day interaction (z=0.10, p=0.92)(Figure 2C). Overall, participants rarely (9.9% of Day 2–3 trials) erroneously bypassed the familiar route with one or more shortcut hallways in an environment on these tasks; for subsequent Probe trial behavioral analyses, we excluded environments in which they did not accurately follow the familiar route by the end of training (by shortcut or other strategy; see Supplement).

Stress effects on navigational strategy

During fMRI, participants were placed along the familiar route and cued to navigate to a specific goal object as quickly as possible using any strategy (Figure 1). If participants flexibly retrieve associations from an accurate relational representation of the environment, they could navigate most efficiently by taking the available (but previously never traversed) shortcut through the environment. As such, our critical behavioral measure was the probability of taking a shortcut. This Probe test was repeated twice (termed Probe 1 and Probe 2) in each environment to gain insight into whether stress effects on strategy selection are influenced by repetition. Since learning/retrieval could occur during performance of the first probe of an environment (i.e., goals and, if taken, shortcuts were only truly novel during the first Probe test), our primary focus was on effects of stress on Probe 1.

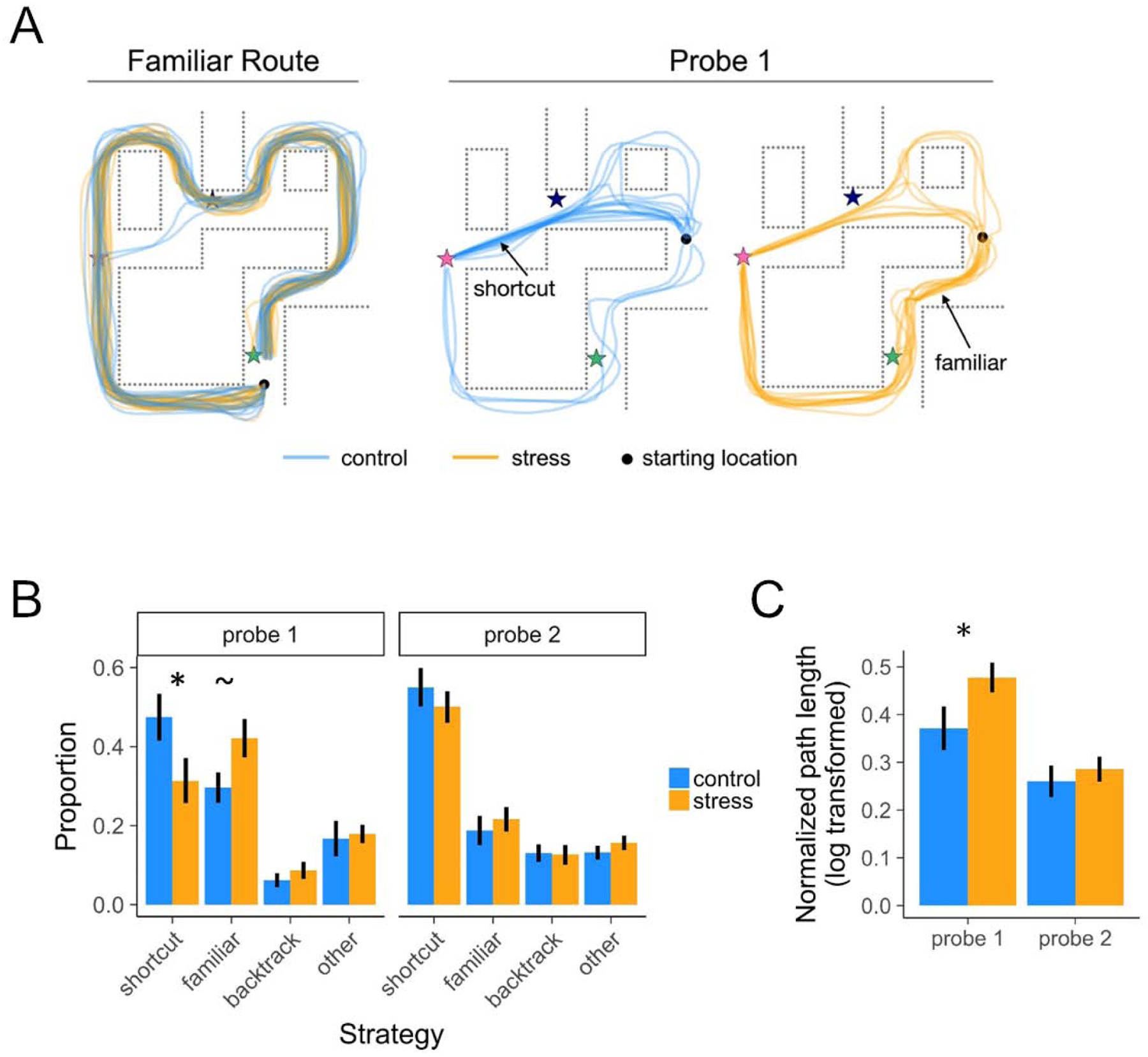

When faced with a novel goal on Probe 1, the probability of taking a shortcut was significantly reduced in the stress group (31%) relative to the control group (47%; z=2.07, p<0.05; Figure 3A–B). By contrast, on Probe 2, when the goal was no longer novel, the probability of taking a shortcut did not significantly differ across groups (stress=50%, control=55%; z=1.05, p>0.1). The probability of taking a shortcut increased from Probe 1 to Probe 2 (z=3.60, p<0.001), with the increase in shortcut-taking being moderated by group to a marginal degree (group × Probe round interaction: z=−1.71, p=0.09, BF=1.17; main effect of group across rounds: z=1.74, p=0.08, BF=0.57): this was reflected in the probability of taking a shortcut significantly increasing across rounds for the stress group (b=0.43, z=3.94, p<0.001), more so than the control group (b=0.17, z=1.43, p=0.15; Figure 3B). These results indicate that the probability of taking a shortcut in a well-learned environment was impaired under stress selectively during navigation to novel (but not repeated) goals.

Figure 3. Behavior.

(A) Illustration of all participants’ paths, by group, in a representative environment. Stars indicate categorically distinct landmark objects. (B) Proportion of well-learned environments navigated using various strategies. During the first Probe round (Probe 1), the probability of taking a precise shortcut was higher in the control vs. stress group, and vice versa for taking a familiar route. By the second Probe round (Probe 2), the stress group took an equivalent proportion of shortcuts. (C) Normalized path length as a function of group and Probe round. During Probe 1, the stress group had significantly longer path lengths than the control group, indicating that stress restricted flexible access to environmental knowledge during planning thereby impairing efficient navigation. Error bars indicate within-participant standard error of the mean. See also Table S3 and Figure S1.

Because the environments were relatively complex, participants could plan and flexibly navigate to the goal, but via marginally sub-optimal alternate shortcuts (i.e., going through unused pathways or passing through one of two shortcut segments; e.g., two control participants who partially deviated from the optimal shortcut in the top right of the Figure 3A Probe 1 map). Under such a broader “shortcut” definition, stress also reduced the probability of flexible navigation (stress M=35%) relative to the control group (control M=53%; z=2.39, p<0.05) on Probe 1, but not Probe 2 (z=0.51, p>0.1), and the interaction between group and Probe round was significant (z=−2.36, p<0.05).

Concurrent with a reduction in taking shortcuts, we further predicted that stress would increase reliance on well-learned (familiar) stimulus-response memories during navigation. While testing this possibility is not independent from the preceding shortcut analysis, we sought to rule out that reduced shortcut-taking was driven by stress participants getting lost and wandering, rather than taking the familiar route. Consistent with our predictions, the stress group was more likely to take the well-learned familiar route on Probe 1 (stress M=42%; control M=30%; z=−1.93, p=0.05). In contrast, the groups were similarly likely to take the familiar route on Probe 2 (stress M=21%, control M=19%; z=−0.69, p>0.1). There was no group × Probe round interaction (z=1.19, p>0.1), with a main effect of decreased adoption of a familiar route strategy from the first to the second Probe round (z=−4.76, p<0.001). These stress manipulation outcomes for shortcut and familiar route strategies, juxtaposed with the backtrack and other/wandering rates (Figure 3), suggest that stress effects targeted the balance between planning and decision-making vs. familiar action, rather than simply inducing a general disorientation.

Effects of stress on navigation path length

We next examined whether a continuous measure of navigational efficiency (spanning optimal, suboptimal, and familiar strategies) was affected by stress. First, path lengths for taken shortcuts were by design shorter (normalized to each environment’s optimal route) than those of the other route classifications (ps<0.001). Second, normalized path lengths during Probe 1 were significantly longer under stress (t(33.6)=−2.17, p<0.05; Figure 3C). Moreover, a significant interaction, as determined from a linear mixed effects model, between group and Probe round (t(118.8)=2.22, p<0.05) revealed that by Probe 2 the stress group had similar path lengths to controls (t(34.7)=−0.60, p>0.1). Across groups, path lengths were significantly shorter on the second round (t(118.8)=−6.68, p<0.001).

The present study focused on effects of stress on prospective planning mechanisms. While processing during subsequent navigation can complicate coupling between planning processes and ultimate behavior, additional exploratory analyses of performance during navigation revealed that participants in both groups were slower to navigate at the onset of Probe 1 trials, particularly when they subsequently took a shortcut and not the familiar route (see Supplement). Interestingly, and consistent with the neural findings reported below, initial planning on novel shortcut-strategy Probe trials appeared to be more effective for the control group because they tended to navigate more quickly and with fewer pauses en-route to the goal (see Supplement). These outcomes document other expressions of efficiency following flexible prospective planning that are diminished by stress.

Neural results

How is neural activity affected by stress during prospective route planning?

Our primary aim was to investigate how acute psychological stress influences the neural mechanisms underlying flexible use of memories to guide prospection, operationalized as route planning to a novel goal. Accordingly, fMRI analyses focused on activation during the Probe period, first targeting a priori regions-of-interest — the hippocampus and CCN — given our hypotheses, followed by whole-brain analysis.

Hippocampus.

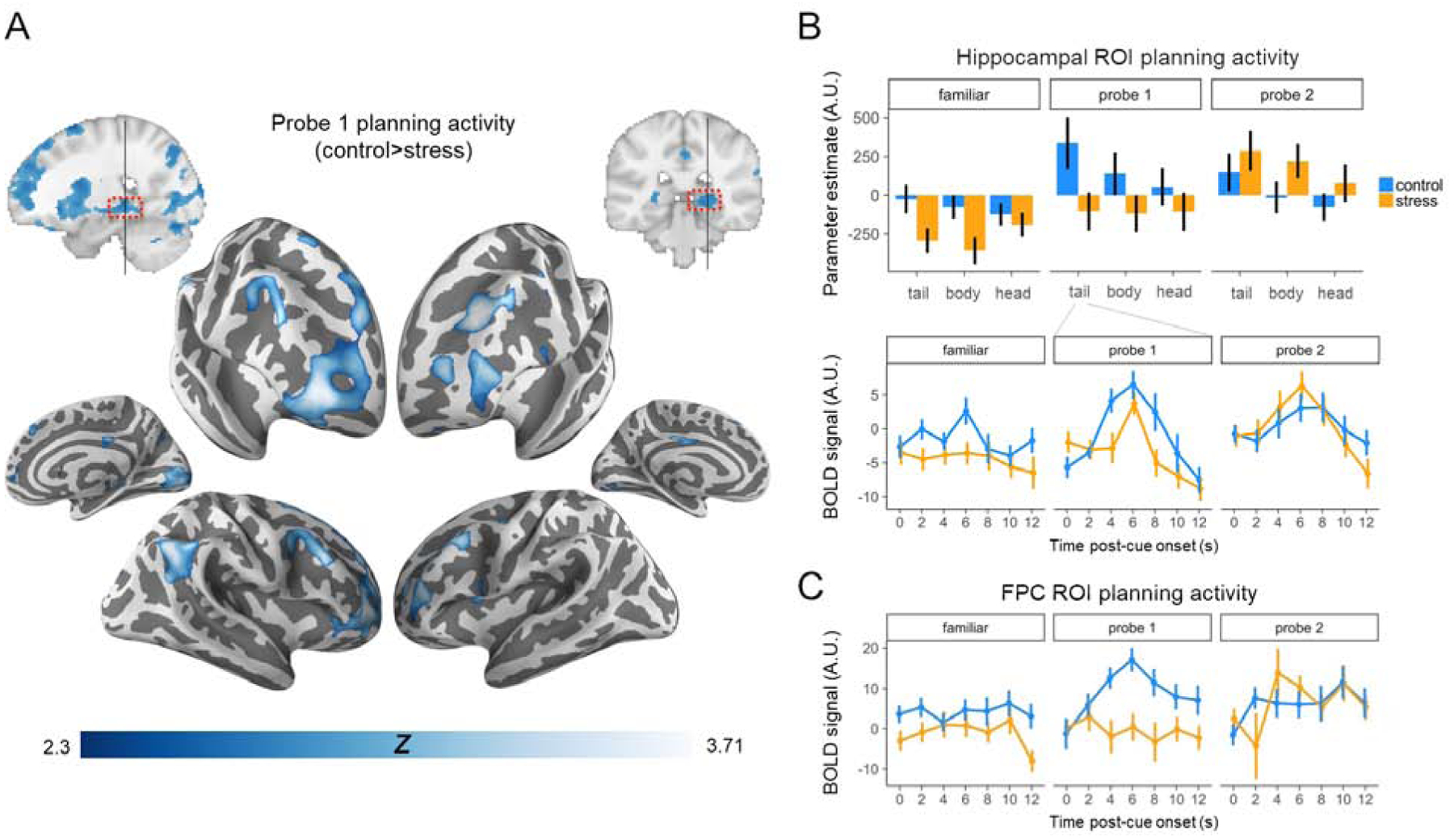

Previous theorizing suggests that the posterior hippocampus is critical for activating representations of a future path to a goal [18], and indeed there is evidence for anatomical and functional specialization across the long axis of the hippocampus favoring representation of more precise spatial information in the tail [54,55] (but see [56]). Consequently, we conducted targeted ROI analyses analyzing planning activation as a function of stress along the long-axis of the hippocampus. Across both familiar and novel goal planning, there was a significant interaction as determined from the linear mixed effects regression between group and sub-region (t(36)=2.73, p<0.01). Follow-up pairwise tests indicated the control group had significantly higher planning activity than the stress group in the hippocampal tail (t(36)=2.56, p<0.05) and body (t(36)=2.09, p<0.05), but not in the head (t(36)=−1.50, p>0.1). Interestingly, there was no group × task (Familiar/Probe 1) interaction (t(36)=0.52, p>0.1), although the follow-up pairwise increase in activity from familiar route to Probe 1 observed in controls (t(17)=2.31, p<0.05) did not reach significance in stressed participants (t(19)=1.54, p>0.1) (Figure 4B). These data provide evidence that planning activity in the hippocampus was degraded under stress for novel probe trials (control>stress, t(36)=2.16, p<0.05), but also during prospective retrieval of familiar routes (control>stress, t(36)=2.05, p<0.05)

Figure 4. Prospective planning activity across groups.

(A) The control group recruited hippocampus and lateral prefrontal and parietal CCN regions more than the stress group when planning navigation to novel goals (Probe 1). p<0.01, voxel-wise threshold; cluster-corrected to a false positive rate of p<0.05[17]. (B) Hippocampal ROI planning activity was reduced under stress, particularly in the tail (timecourse in middle panel). Hippocampal activity, along with shortcut behavior, recovered (increased) in the stress group during Probe 2 planning. (C) Bilateral FPC ROI activity as a function of task and group. FPC activity increased during Probe 1 planning in the control group, but decreased with goal familiarity (Probe 2). In contrast, activity increased in the stress group selectively during Probe 2 planning. Statistics were conducted on parameter estimates; time courses are for visualization purposes only. See also Table S4, Figure S3, and Figure S4.

Our prior data would not suggest a lateralization effect in the hippocampus for prospective signals [17]. By contrast, other evidence suggests that right hippocampus preferentially tracks access to allocentric spatial representations, whereas left hemisphere tracks use of sequential representations [57]. Accordingly, we explored whether adding an interaction of condition and hemisphere would improve model fit. There was no evidence for an interaction of condition and hemisphere (χ2(8)=6.33, p>0.1).

Cognitive control network.

We examined the effects of stress on control-related planning activity using two ROI approaches: (a) defining a combined CCN ROI that included frontoparietal components of Networks 12 and 13 from a 17-network resting-state cortical parcellation [58] (which included FPC, along with lateral prefrontal cortex spanning the inferior frontal sulcus and lateral intraparietal sulcus), and (b) defining the lateral FPC component of the CCN, given our a priori predictions about the role of this region in memory-guided prospection (see Methods). We examined CCN activity as a function of hemisphere, given evidence for left lateralization in parietal recollection effects [59] and right localization of FPC in our prior work on spatial prospection[17].

As predicted, stressed participants demonstrated significantly reduced activity in the CCN relative to controls during Probe 1 (t(36)=3.68, p<0.001). There was no significant effect of hemisphere (t(36)=0.11, p>0 .1) or group × hemisphere interaction determined from a linear mixed effects model (t(36)=1.67, p>0 .1). An effect of stress also was observed when specifically targeting the lateral FPC component of the CCN [17]: Probe 1 planning activity was markedly reduced under stress in right FPC (t(36)=4.02, p<0.001); this reduction was again evident when collapsing across hemispheres (t(36)=3.62, p<0.001) (Figure 4C).

Moreover, putatively reflecting the increased cognitive control demands with novel goal planning, (a) a linear mixed effect model revealed a group × task (Familiar route/Probe 1) interaction in FPC (t(36)=2.57, p<0.05), with pairwise follow-up tests indicating Probe 1 FPC activity was significantly greater than Familiar route activity in control participants (t(17)=3.88, p<0.01), but not in stressed participants (t(19)=0.04, p>0.1)(Figure 4C); and (b) while Probe 1 CCN activity was significantly greater than Familiar route activity in both groups (control: t(17)=5.37, p<0.001; stress: t(19)=2.78, p<0.05), again there was a group × task interaction (t(36)=2.03, p<0.05). Focusing on CCN activity during familiar route planning, we did not observe a significant effect of group (broader CCN: t(36)=1.36, p>0.1; FPC: t(36)=0.97, p>0.1), which formally differed with the pattern of data in the hippocampus (group × task × ROI [CCN/FPC vs. hippocampus] interaction: t(36.1)=−2.46, p<0.05) in which processing differed between groups in both tasks.

Whole-brain univariate activity.

Extending the ROI analyses, a contrast between groups (Figure 4A) revealed significantly reduced Probe 1 planning-period activity under stress in multiple regions, including right posterior hippocampus, bilateral lateral FPC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and right angular gyrus. We also observed stress-related reductions in early visual cortex, parts of putamen, and right dorsal caudate (tail/body). We complemented this voxel-level analysis with a broader “route-planning network” ROI analysis (see Supplement).

How does neural evidence for prospective retrieval track planning over route options?

One mechanism through which stress may alter shortcut planning and execution is by limiting engagement in prospective retrieval of learned environmental features beyond one’s immediate choices (i.e., restricting the spatiotemporal scope and detail of prospection). We asked how neural evidence for future landmark objects/locations manifests when planning a novel route in stress and control participants. A pattern classifier trained on participant-specific categorical item/object representations (see Methods) was tested on Probe 1 planning activity, with biases in neural evidence towards one landmark object over another (long-term goal, shortcut path landmark, or familiar route landmark), binned according to subsequent route type taken, indicative of memory reinstatement [37].

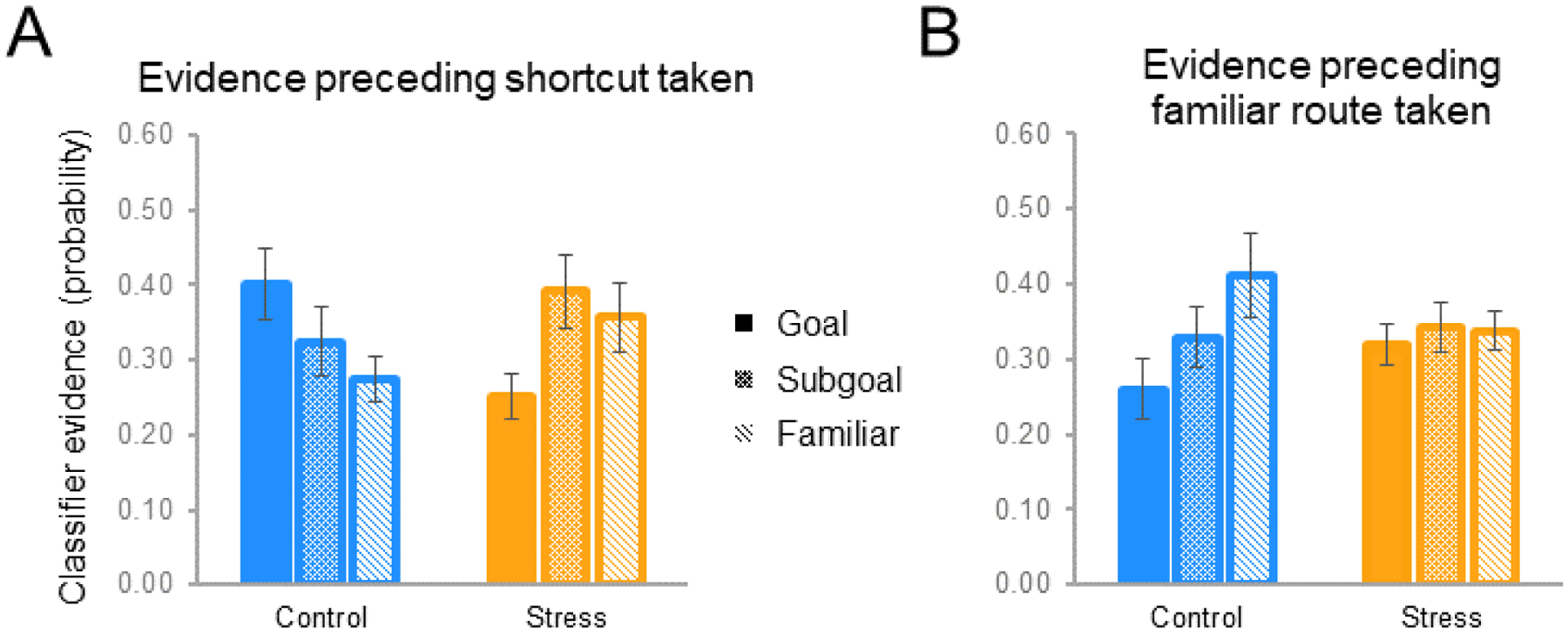

First, we tested an omnibus linear mixed effects model of group × landmark × route choice interactions to assess (a) whether there were overall group differences in evidence for prospective reinstatement and (b) whether evidence dynamically varied as a function of subsequent route choice on the probe trials (shortcut vs familiar). There was an overall group × landmark evidence interaction (F(2,216)=6.44, p<0.01), indicating that the stress manipulation drove an overall shift in landmark evidence profile; critically, as is clear in Figure 5A and 5B, there was a significant group × landmark × route choice interaction (F(2,216)=5.18, p<0.01), indicating that the different landmark evidence profiles for the groups significantly differed as a function of subsequent route choice.

Figure 5. Landmark evidence during the Probe 1 planning period as a function of ultimate route taken.

(A) When ultimately taking a shortcut, controls exhibited the strongest planning-period evidence for long-term goals (Goal), followed by shortcut subgoals and familiar route landmarks. By contrast, stress participants showed weaker long-term goal evidence (than control participants, and than subgoals). (B) This pattern in controls reversed during trials on which the familiar route was ultimately taken, whereas stress participants failed to exhibit differential reinstatement evidence. See also Table S5.

Examining the breakdown of this omnibus effect, for shortcut-taken probe trials there was a significant group × landmark evidence interaction (F(2,108)=4.69, p<0.01) such that control and stress participants exhibited fundamentally different classifier evidence profiles planning. Control participants’ classifier evidence profiles (Figure 5A) significantly differed from empirical baseline (F(2,68)=9.92, p<0.002). In the stress group (Figure 5A), the strength of evidence for one landmark being represented over another was not significant overall (F(2,95)=2.19, p>0.1). Pairwise comparisons examining the group × landmark evidence interaction demonstrated that in control participants long-term goal evidence was significantly greater than that for the familiar (alternative) route landmark (t(51)=2.13, p<0.04), with shortcut subgoal evidence falling in between. Shortcut subgoal evidence did not significantly differ from familiar route or to the long-term goal landmarks (control group shortcut goal>subgoal, t(51)=1.28, p>0.2; subgoal>familiar, t(51)=0.84, p>.4), although this may be unsurprising given the interdependence of classifier evidence scores and the fact that some deliberation over the familiar route likely occurs during the planning process. Although there was no overall main effect of landmark type in stress participants (see above), the stress group did exhibit (a) significantly weaker relative evidence for the long-term goal compared to controls (control>stress goal evidence, t(36)=2.78, p<0.01), and (b) lower goal evidence compared to proximal locations along the two possible routes (stress group shortcut subgoal>goal, t(57)=2.34, p=0.02; familiar>goal, t(57)=1.76, p=0.08 – BF=1.18). This pattern should be interpreted in context of the lack of overall main effect of landmark type in the stress group, but nevertheless could suggest a relative suppression of long-term goal representation under stress, or a restricted scope of planning in stress participants, such that neural evidence favors deliberation over proximal locations on the alternative routes – a (restricted) prospection-like profile not observed when they default to the familiar route (reported below) (see also evidence for continued route-uncertainty during subsequent navigation, consistent with reduced pre-planning of behavior – see Supplemental speed analysis).

Turning to the other component of the omnibus group × landmark × route choice interaction, when participants instead ultimately decided to take the familiar route during Probe 1 trials, there was again a significant group × landmark evidence interaction (F(2,108)=7.25, p<0.01), but control participants’ planning evidence profile reversed, with the familiar route landmark being represented more strongly than the long-term goal (t(51)=2.32, p<0.02) (but again not the shortcut subgoal - t(51)=1.26, p>0.1; overall gradient was marginal from null -F(2,51)=2.70, p<0.08 – BF=1.01, indicating ambiguous likelihood for H1 vs H0) (Figure 5B). By contrast, while stress participants preferentially took familiar routes, when they did so we did not observe evidence for route prospection, and indeed there was no evidence favoring the familiar route landmark during the planning period (t(57)=1.23, p=0.22) (Figure 5B). Together, these data document that while control participants prospected during planning, with their prospective planning content tracking future navigational behavior (see Supplement for additional exploratory correlation analyses with behavior, exploring whether there may be continuous relationships between planning activity and evidence and shortcut-taking), the relative evidence for cortical replay of long-term goals and familiar route subgoals was significantly altered by stress.

Is there a recovery of neural activity in the stress group upon repeated planning?

Stress pushed participants to take fewer shortcuts during Probe 1, but their navigation performance recovered to match controls during the second round (Probe 2). To the extent that activity in the hippocampus and CCN contributes to novel shortcut planning, it should also track the emergence of new shortcuts in the second repetition. Indeed, the stress group showed increased activity during planning on Probe 2 vs. Probe 1 in the hippocampus (t(19)=3.51, p<0.01) (Figure 4B) and CCN ROIs (broader CCN: t(19)=2.72, p=0.05; FPC: t(19)=2.66, p<0.05) (Figure 4C).

Within the hippocampus we observed a significant group × Probe round interaction (t(36)=2.61, p<0.05), such that the increase in hippocampal activity during Probe 2 (relative to Probe 1) planning was selective to the stress group (t(19)=3.51, p<0.01); there was no significant change in the control group (t(17)=0.99, p>0.1). Activity was generally greater in the posterior vs. anterior hippocampus across rounds and groups (main effect of sub-region: t(36)=4.09, p<0.001), with a marginal group × Probe round × sub-region interaction(t(36)=1.82, p=0.08, BF=1.2). Together, this provides evidence that the stress group was able to recruit the hippocampus during planning selectively during the second Probe round, whereas the control group showed evidence for consistent levels of hippocampal recruitment during planning across both rounds.

Group × Probe round interactions were also significant in the CCN (broader CCN: t(36)=3.41, p<0.01; FPC: t(36)=3.67, p<0.001). Mirroring the increased activity during planning from Probe 1 to Probe 2 under stress, we observed significant decreases in activity in these regions in the control group (broader CCN: t(17)=2.15, p<0.05; FPC: t(17)=2.61, p<0.05). This is consistent with previous findings that repeated retrieval of the same episodic memory leads to faster access to that memory [60], and reduced activity in in the CCN; such decreases in neural activity are thought to reflect reduced demands on cognitive control during subsequent retrieval attempts [29].

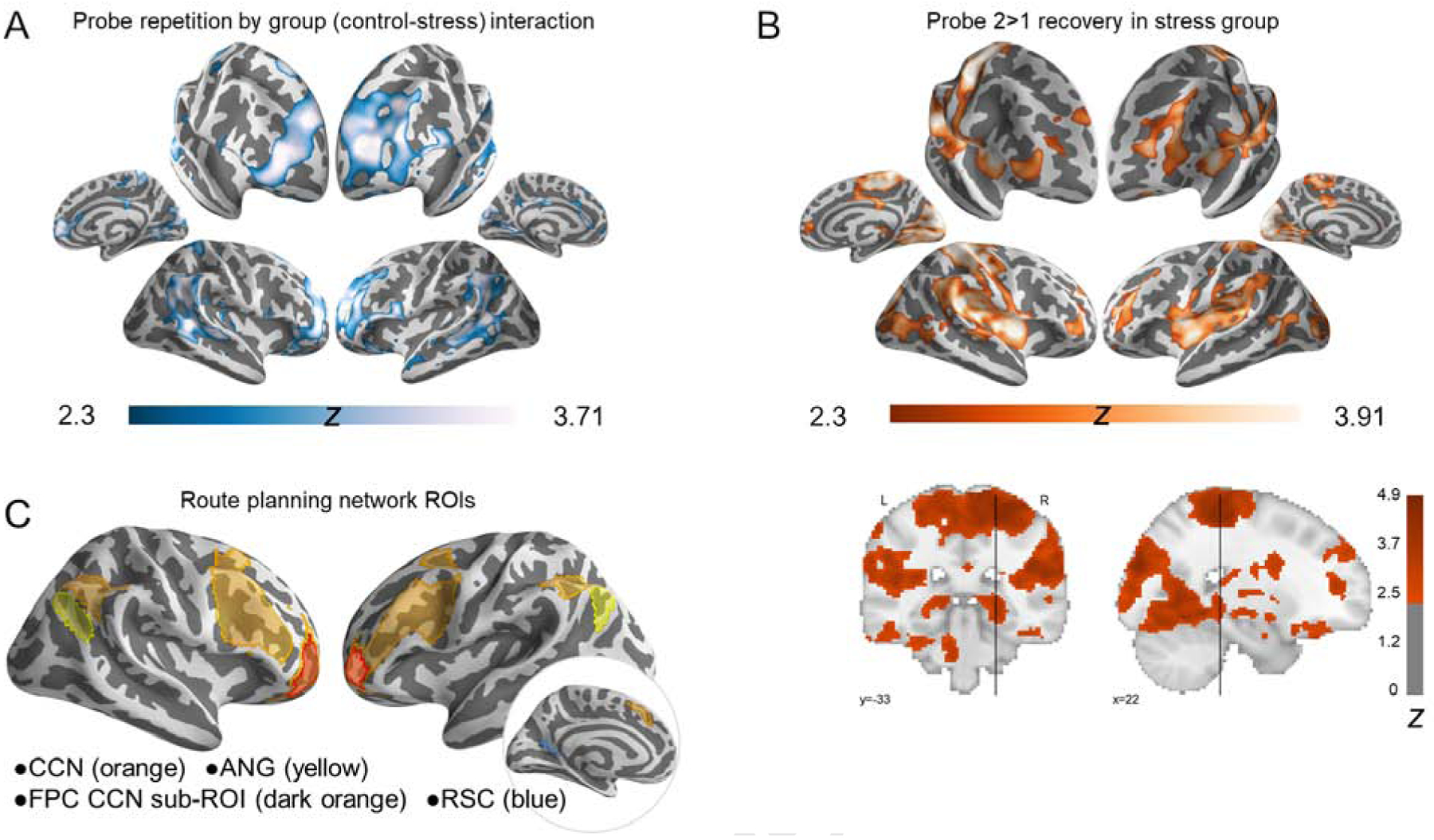

Extending these ROI findings, a voxelwise whole-brain analysis (Figure 6) revealed a group × Probe round interaction in multiple regions, including bilateral FPC, superior frontal sulcus, anterior IFS, anterior angular gyrus extending into supramarginal gyrus. The stress group did not show significantly greater activity relative to the control group in any brain regions during Probe 2 planning, but exhibited greater activity in this network during Probe 2 relative to Probe 1 trials, corroborating the ROI data (above and Supplement for angular gyrus, parahippocampal place area, and retrosplenial cortex).

Figure 6. Interaction of novel planning (Probe 1) relative to repeated planning (Probe 2) for controls vs. stress groups.

(A) Regions showing a group × Probe round interaction were more active during novel than repeated Probe planning in the control group, but greater activity during repeated than novel Probe planning in the stress group. (B) Recovery in the stress group (Probe 2>Probe 1) underlying interaction in A. Frontoparietal control regions (particularly anterior PFC and lateral IPS) and the hippocampal tail were notable a priori loci of this recovery based on our predictions. (C) Visualization of a priori cortical ROIs: cognitive control network – CCN; frontopolar cortex – FPC; angular gyrus – ANG; retrosplenial cortex – RSC. p<0.01, voxel-wise threshold; cluster-corrected p<0.05. See also Table S6, Figure S5, and Figure S6.

DISCUSSION

The present findings provide evidence that acute stress can have profound effects on the neural mechanisms underlying novel, goal-directed planning — restricting the ability to flexibly retrieve map-like knowledge and efficiently navigate to goals. Neurally, stress reduced activity in posterior hippocampus, FPC, the broader CCN, and recollection-related regions (such as angular gyrus) during novel route planning. Behaviorally, stress decreased the probability of taking novel shortcuts, and increased path lengths to reach goals. Critically, we show novel evidence that prospective coding in the cortex tracks these neurocognitive changes as well as participants’ decisions – in control participants neural evidence in planning activity for landmarks along future routes shifts with their route strategy, and in stress participants the evidence for prospection was disrupted. Collectively, our data provide a critical link between hippocampal-FPC mechanisms of goal-directed route retrieval [10,17] and novel route planning, simulation, and free strategy adoption, and demonstrate disruption of these mechanisms under stress.

Neural networks recruited for goal-directed route planning

When focusing on control participants, our data complement prior studies [18,61]: non-stressed participants recruit posterior hippocampus and the CCN (in particular, lateral FPC), in addition to a broader “route-planning network” including angular gyrus and scene-selective regions (parahippocampal place area and retrosplenial cortex), to a greater extent during goal-directed novel route planning than those same non-stress participants do for Familiar route planning. This increase did not significantly differ from the Stress group (no significant interaction). These regions are thought to support (a) flexible retrieval of relational information about the environment from the hippocampus, and (b) simulation and selection over alternative path sequences [18], and encompass areas known to show recollection success effects during episodic retrieval [59,62,63]. Importantly, when combined with the disruptive effects of stress on planning activity in these regions (discussed below), our data provide novel evidence in the literature linking this broader network to flexibly accessing memories that guide effective prospective planning, thereby influencing efficient subsequent behavior.

Disruptions in goal-directed route planning under stress

Relative to controls, stressed participants exhibited reduced recruitment of a recall network [63] including the hippocampus, CCN (including lateral FPC), and angular gyrus during novel route planning. First, stress specifically reduced planning activity in the posterior hippocampus, and the stress group also failed to show increased activity in the posterior hippocampus during novel vs. Familiar route planning (in contrast to controls). Second, a significant interaction between group and task (Familiar vs. novel route planning) revealed that the disruptive effects of stress were greater during novel relative to Familiar route planning in control and planning circuitry. Finally, we observed a similar pattern in FPC previously linked to hippocampal-mediated route planning and decision-making[10,17]. FPC (and CCN more broadly) novel Probe planning activity was markedly reduced under stress (Figure 4C). Additionally, the differential reduction in hippocampus activity for familiar route retrieval (relative to CCN) in the stress group could be suggestive of controls pre-playing (not necessarily “planning” per se) the well-learned route [13,17].

Importantly, these stress-related neural changes paralleled reduced shortcut-taking in the stress group on novel Probe trials. Moreover, the interesting behavioral recovery in the stress group on the second round of Probe trials accompanied recovered neural signal during planning. Why did stress participants improve on the second Probe round? In our prior study of word-scene associative retrieval [37], in which we used the identical threat of shock stress manipulation, we directly examined whether the stress effects on memory are explained by divided attention. We observed no evidence for such attentional consequences in that study, suggesting that the disruptive effects are cortisol driven. While this does not guarantee that attention is not a contributor to the present effects, it does suggest otherwise, and that alternative mechanisms should be considered for the Probe 1 to Probe 2 recovery. One possibility is that the stress effects dissipated over the course of the session. While a possibility, it seems unlikely that HPA-axis effects would have ceased by the second Probe round (approximately 100min post-arrival at the lab) [64]. Indeed, cortisol remained marginally elevated at the end of our scan session, and affective ratings remained negative throughout. When slower genomic effects emerge in response to a stressor, some research suggests that CCN network activity should recover [46] – although this causal relationship can only be speculatively applied to our current observations. This raises the possibility that CCN-dependent performance may have improved via these genomic effects on the second Probe round of the task. This finding motivates future work that examines the precise timing of stress effects on neural function and behavior, as well as whether these effects are moderated by stressor type.

Another possibility is that additional learning (or relearning) during navigation on the first Probe round allowed the stress group to draw on memory to engage in more efficient performance during the second Probe round. Although stressed participants were less likely to take shortcuts during Probe 1, they nonetheless could acquire further knowledge of (or relearn) the environments’ layouts. In so doing, participants may also have learned a strategy to solve the task more efficiently over the course of the first round, i.e., that shortcuts exist in the environments. This possibility raises the important distinction observed in the literature that although stress effects (e.g., cortisol) may disrupt retrieval, they have conversely been associated with enhanced encoding (for review, see [41,65]). Combined, such a learning outcome would be consistent with Goldfarb and colleagues’ [66] observation that pre-retrieval stress transiently impairs recall of context associations, but with performance recovering by the end of the session, putatively as a result of “relearning”. As an exploratory analysis of the present path length data (Figure 3C), we further examined Probe 1 trial navigation behavior by run, enabling examination of performance changes as the task structure repeated (independent of environment repetition). We observed that the stress group had longer Probe 1 path lengths than controls but critically no interaction by run. As such, the shortening in path lengths on Probe 2 trials (i.e., more shortcuts) is more suggestive of environment-specific learning driving the improvement in performance in the stress group, rather than gradual task strategy learning across trials. This is also consistent with the fact that the stress group preferentially recruited frontoparietal and hippocampal regions during planning on the second Probe round (Figure 4B–C), suggesting that stress participants differently engaged in prospection during Probe 2 relative to Probe 1 planning.

A third (not mutually exclusive) possibility is that anticipatory stress shifts the balance between exploration vs. exploitation, causing participants to be more risk-averse. While the literature is mixed [67], some studies document decreased risk-taking under stress [53]. In the present study, risk-aversion could manifest during navigation as an aversion to shortcut-taking, as novel path selection runs the risk of a wrong turn/dead end. In addition to triggering error-related processes, such navigational outcomes also would have modestly prolonged the time in the scanner, increasing the duration in which stress participants were under threat. In the debrief, one stress participant wrote that during the planning period they considered “whether I would follow the route (safe way) or if I could remember the town routes by memory (riskier).” As such, if access to memory were degraded under stress and/or participants were not positive that a shortcut would lead to the goal, aversion to making a mistake might have pushed stress participants to take more familiar routes during the first Probe round. Subsequently, additional knowledge (e.g., via (re)learning) acquired during the Probe 1 navigation might have sufficiently reduced their uncertainty about shortcut success, leading to recovered “exploratory” behavior (shortcut-taking) on Probe 2.

Our new findings highlight an important future direction, motivating follow-up studies aimed at specifying the precise mechanism(s) that enable(s) recovery of performance under stress. Such specification may have important implications for developing interventions that improve prospection in individuals suffering chronic stress and/or anxiety, among other conditions, and that allow individuals to more effectively leverage memory to achieve efficient goal-directed planning and behavior.

Hormonal effects in other groups

Another important future direction following this work is to examine gender effects. In the present study, we restricted inclusion to male participants given evidence for more pronounced effects of stress on cortisol and memory performance in males relative to females [68–72]. Such differences could be influenced in part by variations in sex hormone levels across the estrus cycle [73–75] and use of oral contraceptives [76]. One intriguing prediction from such literatures may be that the stress effects observed in this experiment would be attenuated in females. Conversely, however, there is a long-standing literature providing evidence that women may find spatial navigation itself more stressful [77], which could perhaps a) counteract a propensity for reduced stress effects on cortisol and memory in females and b) yield similar or even more robust stress-related navigational disruption than we observed in men. Given the complexity of the extant literature, it will be of great interest for future studies with larger sample sizes to assess whether the present effects generalize to females, and to younger and older populations where hormonal levels also differ.

Tracking mental simulation under stress

Spatial navigation events involve complex, continuously evolving cognitive and behavioral states, which create challenges for identifying signals specific to planning and prospective thought. In our design, we defined a perceptually and behaviorally controlled task period in which planning could occur (if the participants chose to). As discussed above, we demonstrate that impairments in, and recovery of (upon repetition of an environment), subsequent shortcut behavior is preceded by group differences in planning-period activity in hippocampus, FPC, and the CCN.

By leveraging neural pattern classification to assay replay of environmental features (i.e., objects embedded in the shortcut and familiar paths), we provide a novel, link between disruptions in planning-period activity to evidence for altered prospective simulation. These analyses suggest that the stress group exhibited relatively greater evidence for proximal locations than for the distal goal during planning (although note that the main effect of landmark type did not reach significance at traditional thresholds). This may be consistent with the prediction that, in biasing humans from “thinking” to “doing” [78], stress may restrict the scope of prospective thought. By contrast, in the control group there was stronger evidence for long-term goal representations than for familiar route landmarks during planning. Moreover, when controls ultimately took a shortcut, planning-period evidence exhibited the same qualitative gradient we observed in a prior study of prospective navigation over familiar paths [17] (goal>subgoal>alternative route) — here we extend this finding, critically, from familiar route replay ([17] and as seen in control participants when choosing a familiar route) to novel route simulation. Interestingly, control participants also exhibited evidence of planning on Probe trials in which they ultimately decided to take the familiar route; in such instances, the neural evidence during planning was stronger for the familiar route landmarks. By using an expanded set of environments (which likely will require substantially longer training and testing sessions), future studies may be positioned to relate trial-wise reinstatement during planning to hippocampal and FPC activity. Nevertheless, the collective outcomes of the present study establish a critical link between observations of hippocampus-FPC-mediated prospective route retrieval [10,13,17], cortical mnemonic replay, and free planning and decision-making (i.e., path selection during planning) — a strongly predicted, but to-date elusive mechanistic level of explanation across the literatures in both humans and animals.

Conclusions

A growing body of work suggests that acute psychological stress restricts access to hippocampal-dependent memories [78], thereby limiting the scope of future-oriented planning and flexible behavior. Here, we leveraged a naturalistic spatial navigation task to examine whether and how acute stress may influence prospection and subsequent behavior. Using fMRI, we observed that BOLD activity in regions critical for controlled mnemonic retrieval, including posterior hippocampus and the lateral FPC, was disrupted during novel, goal-directed planning under stress; we further observed that, following such stress-induced disruptions, navigation to novel goals was less efficient. Strikingly, neural activity and performance recovered when the stress participants were given a second opportunity to plan and subsequently re-navigate to goals. Collectively, these findings advance understanding of how emotional states influence the ability to use memory of past experiences to guide decisions and actions, illustrating how stress can diminish one’s ability to harness prospection to efficiently achieve one’s goals.

STAR★METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Thackery Brown (thackery.brown@psych.gatech.edu). This study did not generate new unique reagents.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Forty-two right-handed healthy adult male participants (age M=23.1 yrs, SD=4.4, range=18–35) were recruited from the Stanford University community and surrounding area. We restricted enrollment to male participants given evidence for pronounced differences in effects of stress on cortisol and memory performance in males vs. females [68,69,71,72]; future studies with larger sample sizes will be necessary to determine whether the present effects generalize to females, and to younger and older populations. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and were free of neurological, cardiac, or psychiatric disorders. Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with procedures approved by the institutional review board at Stanford. Participants received monetary compensation for their participation ($25/hr). Data from two participants were not fully acquired due to failure to complete the experiment (due to motion sickness or stress manipulation discomfort), and data from two additional participants were excluded due to failure to demonstrate sufficient landmark object memory or familiar route learning (18% landmark recall, and <50% familiar route accuracy, respectively; see Supplement for additional details). Accordingly, data from 38 participants were included in the fMRI and behavioral performance analyses reported above (18 non-stress control, 20 stress).

METHOD DETAILS

Task overview

To examine the mechanisms of prospective navigation and the interactions between stress and hippocampal-dependent memory, we designed 12 distinct virtual town environments in which participants performed goal-directed first-person navigation tasks. The experiment took place over three consecutive days. During Day 1 and Day 2 training sessions, participants developed knowledge of each environment outside the scanner by over-learning a pre-determined familiar route through each environment (Figure 1A). Critical to our aims, side streets leading from the familiar routes provided an opportunity for participants to leverage allocentric spatial memory to flexibly generate novel shortcuts between locations during a subsequent Probe task during the Day 3 fMRI session (Figure 1A). During the fMRI session on Day 3, we separately examined (a) participants’ memory for the familiar routes (Familiar route trials), and (b) participants’ tendency to flexibly use their spatial knowledge of the environment to take novel, efficient shortcuts vs. stick to the familiar route when navigating to a goal location (Probe trials). Critically, before scanning on Day 3, participants were assigned to either a non-stress-manipulated control group or a group performing the Familiar and Probe tasks under experimentally induced acute anticipatory stress. Below, we provide detailed descriptions of the environments and each experimental phase.

Virtual environments and navigation interface

Twelve unique 3D virtual environment models were created using Maya (Autodesk, Inc.). Each environment model was designed to resemble a town/city (total area M=3081.3 ± SD=269.2 arbitrary units), and contained several unique features, including: (a) one tall building (serving as a distal, global landmark), (b) five-six shorter buildings with unique wall textures, (c) generic walls (i.e., fence, brick, or stone; one unique texture for each environment), (d) bordering trees/hedges (one unique leaf texture for each environment), and (e) a unique ground texture (e.g., dark brown dirt). Textures were acquired via a Google search and http://www.lughertexture.com/. Other features (adapted with kind contribution from [79]) were shared across several environments, including (a) grassy parks with low stone walls and low white fences, (b) segments of concrete sidewalk, (c) blue sky, and (d) tree models (n.b. unique leaf textures were applied to each environment).

Environments were designed to have unique layouts, with one pre-determined path specified by the experimenter to serve as the “familiar route” traversing the environment. Critical to our aims, side streets leading from the pre-determined routes provided an opportunity for participants to leverage spatial memory to generate novel “shortcut” routes between locations during the Probe task (detailed below). In addition, each environment contained three semantically distinct visual objects placed on boxes along the determined familiar route. These environment-specific objects were clearly visible along each route (i.e., placed in the center of the roadway). The three objects were categorically distinct, and were drawn from four visual object categories: famous faces, tools, animals, or fruits/vegetables (all environments contained a face, and, across environments, the other categories were equally represented). The faces of the animals were occluded with white circles, as initial piloting indicated that neural patterns associated with faces and animals with faces were highly confusable. We designed the environments deliberately such that it was not possible to navigate the optimal shortcut (see below) or familiar route without passing a landmark, and these alternative landmarks were always categorically distinct for fMRI pattern decoding purposes (see below).

The virtual navigation task was programmed in the Panda Experiment Programming Library (PandaEPL [79]), an open-source programming library for Python, built on top of Panda3D, an open-source game engine. Participants navigated using arrow keys on the computer (Days 1–2) or MRI-compatible button box (Day 3). Navigation was continuous, at a fixed velocity, with participants able to freely turn left, right, and drive forward (participants could not back up) through the environments. Participants’ location in coordinate space was logged at 20Hz, and subsequently down-sampled to 2Hz.

Behavioral training procedures

Over the course of Days 1 and 2, participants underwent a fixed training regimen to (a) familiarize themselves with the environments (e.g., buildings, object locations), and (b) learn the pre-determined familiar routes. Participants received 10 training exposures to each familiar route over the course of training. On Day 1, participants were instructed that they would learn specific routes through the 12 town environments; they were further told that they would later be tested on their memory for the specific routes, and for the distinct landmark objects encountered along each route. It was emphasized that they should pay attention to the unique environmental features along each pre-determined route, and the specific turns it followed, in order to perform the various memory tasks. Participants were not explicitly informed that they would later be asked to navigate to the landmark objects, or that shortcuts existed.

Guided by behavioral piloting, Day 1 training proceeded in the following structure: 1) participants initially encountered each environment by watching a video of navigation along the pre-determined route for that environment. The video of each environment’s route was presented twice in a row before a video of the next environment’s route was presented. Environments were presented in a distinct order from that in the subsequent active navigation training phases; the order of environments was counterbalanced across participants. 2) Following the videos, participants engaged in arrow-guided active navigation along the routes; here, to ensure participants continued to learn the pre-determined routes, and did not deviate from the path, red arrows were sparsely distributed along the ground to guide participants along the intended trajectory. During arrow-guided navigation, all 12 environments were presented in an interleaved, pseudo-randomized order (counterbalanced across participants), with one trial per environment. On each trial participants were placed along the familiar route, rotated around to orient themselves (11s), and then asked to “Navigate the route” (displayed in white text on a black screen; 4s); upon completion of the route they were told “You completed the route” (4s). After navigating the route through all 12 environments, participants then performed a second repetition through the environments in a different order. Each route during this phase ended by driving into a gray “finish line” that stretched across the road at the initial starting position. Each arrow-guided navigation trial began at a unique starting point along the familiar route, separate from the starting point in the video (the order of unique starting points was counterbalanced across participants).

On Day 2, participants were presented with another viewing session of videos of the familiar routes through the environments (two consecutive repetitions of each environment), and then performed two more arrow-guided active navigation runs through the routes (starting from unique points); each run consisted of one complete cycle through all 12 environments. Participants ended the Day 2 training session with two unguided active navigation repetitions through the environments (starting points overlapped with two of those practiced during guided navigation; order of the environments was counterbalanced across participants). In these unguided active navigation runs, participants were again required to circumnavigate the environment along the pre-determined familiar route, but no arrows were present to guide navigation; similar to the arrow-guided navigation phase, each trial began at a different location along the familiar route, with an orientation to their position in the environment (11s), a planning period (“Navigate the route”; 4s), and ended with feedback upon arrival at the finish line (“You completed the route”; 4s). This phase served as an opportunity for participants to continue learning the landmark objects that fell along the familiar routes, and to practice navigating the routes based solely on memory. Performance on this final memory-guided active navigation phase was logged and coded, and supplemented our analyses of Day 3 navigation (detailed below).

Over the course of Days 1 and 2, participants were also given four landmark object associative recall tests: on Day 1, following the familiar route videos and following the arrow-guided navigation training; on Day 2, following the arrow-guided navigation training and following the unguided navigation phase. For each object recall test, participants were presented with three images of each environment (the order of environments was randomized), and asked to recall the objects found in that environment, in any order. Participants typed in a brief description of each object, typing a question mark if they could not remember an object. At the end of Day 2, participants also performed a practice round of a visual category localizer task (1 miniblock (8 trials) per category; task detailed below).

Behavioral testing procedures

On Day 3 participants were informed whether they were in the stress group or control group, re-consented, and entered the MR scanner. Next, participants completed the threat of shock calibration (if in the stress group), were fitted with a bite bar and situated in the scanner (~5–10 min), and anatomical scans were collected (~5 min). Then, participants performed three tasks concurrent with fMRI: (1) the Familiar route task, (2) the Probe task, and (3) the visual category localizer task.

First, participants completed four runs of Familiar route trials (three environments per run; the order of environments was counter-balanced across participants). The Familiar route task was the same as the unguided active navigation task from Day 2: on each trial, participants were placed in a position along the path they had learned, rotated around to orient themselves (11s), and then tasked with navigating the learned/familiar route (8s; planning phase instructions: “Navigate the route”). Participants then completed self-paced navigation along the familiar route to a “finish line” at their starting location. Upon completion of the route, they were given feedback: “You completed the route” (4s). All text (i.e., planning instructions, feedback) was presented in white font on a black background; during the inter-trial intervals (14s) a white fixation cross was presented on a black background. Participants were instructed to strictly follow, to the best of their ability, the learned route in this phase (note, we never made mention of shortcuts here or in the Probe task below). By design, therefore, their ability to retrace the route accurately (see results) was evidence of its familiarity and enabled us to interpret shortcuts in the subsequent task.

After completion of the Familiar route task, participants performed eight runs of the Probe task (three environments per run; the order of environments was counter-balanced across participants). Here, participants were placed at a random location in one the environments, and rotated around to orient them to their location (11s). Then, they were cued with the name of an object (always a famous face) that they would need to find in the environment (planning phase instructions: “Pick up: George Clooney”); they were provided 8s during which they could think about where this item/object is located in the environment, and how they will get to it as quickly as possible, using whatever strategy they want – although note we did not explicitly instruct participants what to think about during this delay period and shortcuts were never mentioned. It is possible, given the training regimen and strict encouragement in the Familiar route task to adhere to the learned route, that some participants would be reticent to spontaneously adopt a shortcut strategy in the Probe trials. Importantly this would only reduce, rather than inflate, any observed group differences in shortcut taking.

Participants then completed self-paced navigation until arrival at the goal location; the optimal (shortest) route for each environment was always through the shortcut. Upon completion of the route, they were given trial-specific feedback: “Congratulations! You found: George Clooney” (4s). The structure of these trials was identical to the Familiar route trials, with the exception of the specific instructions/feedback about the goal object. Similar to Familiar route trials, all text (i.e., planning instructions, feedback) was presented in white font on a black background; during the inter-trial intervals (14s), a white fixation cross was presented on a black background. To examine effects of possible learning during this phase of the experiment, participants completed two rounds of the Probe task (i.e., four runs per round; the order of environments in each round was counter-balanced across participants). As such, the goals were novel on the first round (Probe 1), but not on the second round (Probe 2).

At the beginning of each Familiar route and Probe run (starting 2s before scan acquisition onset), control participants were presented with a white fixation cross on a black background (10s); stress participants were presented with the reminder (white text on a black background): “SHOCKS POSSIBLE in these trials” (10s). Manual responses were made on an MRI-compatible button box (Current Designs, Philadelphia, PA), using the right hand. At the end of each Probe task run, participants used a 4-point scale to rate the intensity of their affective experience (anxious, stressed, happy, safe; 1=“not at all” to 4=“very much so”), and their level of emotional arousal (1=“not emotionally intense at all” to 4=“extremely emotionally intense”).

Localizer task

Following the Probe-trial scans, participants completed two runs of a visual category localizer task. Stress participants were informed that the shock portion of the task was over, and that they would not receive shocks during this task. During these fMRI runs, participants performed a 1-back task (i.e., indicating if the current image was the “same” or “different” from the preceding image) as they were presented with images from five visual categories: (1) virtual environments (taken from within six additional 3D virtual town models), (2) male/female non-famous faces, (3) animals (faces occluded with white circles), (4) tools/small manmade objects (e.g., a paintbrush), and (5) fruits/vegetables (200 trials/run). Note that the stimuli in the localizer scans were novel (i.e., did not overlap with the environments and items/objects used in the Familiar route and Probe tasks). Each localizer run consisted of 20 miniblocks (four miniblocks/category) of 10 trials (0.6s stimulus presentation, 1s ITI); miniblocks were separated by periods of fixation (10s). Participants were instructed to make a response to each image as quickly and accurately as possible (d’ was not modulated by group [control=3.27, stress=3.36; t(33)=−0.62, p>0.1], and group did not affect RT group [t(33)=−0.81, p>0.1]). The order of miniblocks within run was pseudo-randomized, such that no more than two miniblocks of the same category could appear in a row. Within each miniblock, three trials were 1-back targets (i.e., “same” as preceding trial).

Stress procedure

To equate environmental learning between control and stress groups and to ensure that any stress effects were restricted to Day 3, all participants engaged in the same training procedure during the Day 1 and Day 2 training sessions (detailed below). During training, stress was not manipulated and participants were naïve of their Day 3 group assignment; the investigators were not blind to group assignment. During Day 3, participants were assigned to either the stress or the control group, re-consented, and then acute anticipatory stress was induced in the stress group via a threat of shock procedure [37]. Shocks were delivered from a Grass Instruments SD9 stimulator via two electrodes to the left ankle. A participant-specific titration procedure was used prior to placement in the scanner, to calibrate the level of shock for each individual. During calibration, stimulation began at 0 V and was increased until a level that was “moderately painful” was reached.

Participants were instructed that their selected level of shock would be delivered for brief durations during navigation runs (indicated by a reminder cue at the beginning of each run, saying “SHOCKS POSSIBLE in these trials”), and the timing of shock delivery would be unrelated to performance on the task. Over the course of the 12 navigation task runs (four Familiar route and eight Probe runs), participants were told that they would receive at least five, but no more than seven, shocks; participants received 5–6 shocks in total across the scan session. Shocks never occurred during our target planning phase of Familiar or Probe trials.

Cortisol measurement

We collected saliva samples to index the physiological impact of the stress manipulation. Saliva was captured via a small synthetic swab (Salivette, Sarstedt) held orally for approximately 2 min. One baseline saliva sample (S1) was collected midway through the Day 2 training session, before stress/control group assignment (which occurred at the outset of Day 3). Three more saliva samples were collected during the Day 3 scan session (T1–3): (T1) after the Familiar route task, which was approximately 30 min after stress/control group assignment was communicated, (T2) after the first iteration through the Probe trials, and (T3) after the second iteration through the Probe trials. Saliva samples were stored in a freezer (approximately −60°C) until assayed. To control for diurnal fluctuations in cortisol levels, the scan sessions were scheduled to begin between the hours of 12pm and 5pm, and participants were instructed to refrain from smoking cigarettes, consuming caffeine, engaging in strenuous physical activity, or eating a large meal for 1 hr before coming in for each session of the experiment.

Raw cortisol measurements were positively skewed; prior to analysis, cortisol measurements were log transformed and we winsorized values 2 standard deviations above the mean to the 2-standard deviation value (5.1% of samples) [80]. Due to scheduling constraints, two participants were unable to come into the lab at the exact same time on Day 2 and Day 3; both participants completed the Day 2 session before 11am, when diurnal cortisol levels would be relatively high. Accordingly, we excluded the S1 measurements from these participants and restricted the subsequent cortisol analyses to those (n=38) with baseline-correctable data.

Given that cortisol exhibits large individual differences and typically declines throughout the afternoon [81], a longer temporal shift between the time-of-day for acquisition of the baseline (S1) and test (T1–T3) samples could result in a greater decrease in test cortisol. In part, given the time required for the shock work-up, the stress group tended to have a larger temporal shift (relative time of day) between S1 (Day 2) and T1 (Day 3) measurements (control M=34.8 mins later, stress M=95.9 mins later), though there was sizeable variability in the temporal delta from S1 clock times to T1 clock times within each group and we therefore did not observe a significant difference in this temporal delta between groups (t(36)=−1.29, p>0.1). Nonetheless, because this numerical difference might lead our assay to underestimate cortisol levels in the stress group, we controlled for the temporal shift between S1 and T1 in all analyses of baseline-corrected Day 3 cortisol measures. Indeed, the delta between S1 and T1 had a marginal negative effect on cortisol (t(35)=−1.99, p=0.055 – BF=1.4, indicating weakly greater likelihood for H1 vs H0), such that larger deltas led to lower cortisol measurements at T1, consistent with the hypothesized diurnal trend, emphasizing the importance of our examination of baseline-corrected data.

Route coding

A team of two research assistants each coded every navigation trial from both the Familiar route and Probe tasks, blind to participant condition. We assessed inter-rater reliability with Cohen’s Kappa, and any conflicts were resolved between the two raters. Familiar route trials were coded as (a) “familiar” if the participant took the exact learned route with no deviations, (b) “shortcut” if the shortcut component of the route was traversed (although typically in reverse direction of the intended subsequent Probe trial shortcut, given that design constraints required familiar route vs shortcut strategies during the probe to take opposing directions around the environment), and (c) “other” if some combination of routes was used, or if the participant wandered/explored. Inter-rater reliability across all trials was high (Cohen’s Kappa=0.87, z=40.9, p<0.001). Most coding conflicts arose between categorizations of “shortcut” and “other”, and therefore a third independent coder, also blind to participant condition, further coded “other” trials to resolve discrepancies. Trials categorized as “other” were further sub-categorized by one of the coders according to details of the heterogeneous behavior (e.g., “gains partial knowledge of shortcut, then wanders”). In final coding, and for subsequent analyses (assessment of Probe trial behavior and fMRI), minor deviation trials — on which there was a quick correction and return to the exact desired familiar route and/or on which they did not complete a shortcut — were considered “accurate” and “well-learned”.

Performance on the familiar route trials was assessed twice at the end of training on Day 2, and once more at the beginning of the scan session on Day 3. This allowed us to examine the degree of familiar route learning and retention across participants and groups. While stress participants completed the familiar route task under stress on Day 3, to the extent that the route knowledge was well learned and, perhaps, “habitual”, we did not expect to see an effect of stress on familiar route navigation.