Abstract

The autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex disorder encompassing a broad phenotypic and genotypic variability. The short (S)/long (L) 5-HTTLPR polymorphism has a functional role in the regulation of extracellular serotonin levels and both alleles have been associated to ASD. Most studies including European, American, and Asian populations have suggested an ethnical heterogeneity of this polymorphism; however, the short/long frequencies from Latin American population have been under-studied in recent meta-analysis. Here, we evaluated the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in Colombian individuals with idiopathic ASD and reported a non-preferential S or L transmission and a non-association with ASD risk or symptom severity. Moreover, to recognize the allelic frequencies of an under-represented population we also recovered genetic studies from Latin American individuals and compared these frequencies with frequencies from other ethnicities. Results from meta-analysis suggest that short/long frequencies in Latin American are similar to those reported in Caucasian population but different to African and Asian regions.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by three core symptoms: repetitive/restricted behaviors, impairment in social interaction and variable communication skills [1]. The twin concordance rate and a milder autism phenotype in relatives reflects a strong genetic component in the pathophysiology of ASD; nevertheless, the broad phenotypic variability of this disorder and the 60% of individuals who remain with unknown etiology suggest an interplay of several genetic factors [2–4]

Most of the genetic factors involved in ASD have a role in brain development and the excitatory/inhibitory synaptic balance [5–8]. The serotoninergic system participates in neurogenesis, axon guidance and cell migration, and also modulates GABA and glutamate neurotransmitter release in presynaptic terminals. Within the serotoninergic system, the serotonin re-uptake transporter (SERT) located in presynaptic terminals and encoded by the SLC6A4 gene (Solute carrier family 6 member 4, Gene ID: 6532) has been widely studied. The transcriptional efficiency of SLC6A4 is regulated by the well-known short (S)/long (L) 5HTTLPR (5-HTT gene-linked polymorphic region) polymorphism, a repetitive sequence present in the upstream regulatory region of this gene [9–14]. The short allele which reduces the transcriptional activity has been reported with greater frequency in African and Egyptian individuals with ASD [15,16], and has been also associated with other psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder [17–20], bipolar disorder [21] and depression risk in Parkinson disease [22] among others; however, conflicting results have been also reported [23–25].

Despite three meta-analysis suggesting that the short/long alleles are not risk factors for ASD [26–28], the ethnical heterogeneity among included studies has been proposed as a factor that may affect the overall result. A comprehensive transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) meta-analysis including eighteen studies from diverse populations, demonstrated a non-preferential S/L transmission at the global scale, but preferential transmission of the S and L alleles in the American and Asian populations, respectively [29]. Thus, based on the frequency differences of 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in the worl-wide population, here we present an attempt to understand the role of short/long allele in Colombian population with idiopathic ASD in terms of risk, preferential transmission and symptoms severity. Additionally, we performed a meta-analysis aiming to evaluate the heterogeneity of the S and L alleles in the under-represented and highly admixed Latin America population.

Materials and methods

The research protocol was approved by ethics committee of participating institutions (Universidad de Los Andes and Instituto Colombiano del Sistema Nervioso—Clínica Montserrat). Written informed consent was obtained by all participants under 16. Parent or legal guardian written consent was obtained for all participants 15 and under or unable to consent.

Subjects

Idiopathic ASD diagnosis confirmed in 105 individuals was performed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V (DSM-V) criteria [1]. Clinical evaluation also included the completion of the ADOS [30,31] and ADI-R [32] instruments. For our case-control analysis we used genotypic information of 171 unrelated and unaffected Colombian individuals belonging to the same region as the ASD trios. Peripheral blood was obtained from all participants and parents. DNA was extracted using Flexigene® DNA kit (Quiagen, Inc).

Genotyping

5-HTTLPR polymorphism was screened through PCR and gel electrophoresis according to Petri S et al., 1996 protocol [33]. PCR product was visualized with 3% MetaPhor agarose gel electrophoresis [Lonza Group Ltd., Basel, Switzerland].

Literature search

The Meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) criteria [34]. We screened without date restriction reports that evaluate the association of 5-HTTLPR and psychiatric disorders in PubMed, ScienceDirect and Scielo databases up to April 2020. To minimize the chance of missing relevant studies the search terms in PubMed and ScienceDirect databases were “HTTLPR” “SLC6A4” AND the name of each country encompassed in South and Central America (each separated by the Boolean operator OR). For the Scielo database, we searched published literature in the indexed journals from Latin American countries (S1 Fig). The inclusion criteria were (1) full text article in English or Spanish languages (2) case-control studies evaluating the polymorphism in psychiatric disorders (3) genotypic or allelic frequency provided and (4) control individuals not deviated from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE). We excluded reviews, studies evaluating trios, cases and no controls, population without a clinical diagnosis and studies that did not evaluate the Latin American population or the association of 5-HTTLPR with psychiatric disorders. For articles that did not have all the information available the authors were contacted. The data extraction was carried out by two investigators independently. The collected data from each study was categorized as reference, country of origin, evaluated trait, number of individuals and allelic/genotypic frequencies.

Statistical analysis

The test of association between ASD and 5-HTTLPR polymorphism was evaluated under the allelic (L vs S), genotypic (SS vs SL vs LL), dominant (LL/LS vs SS) and recessive (SS/SL vs LL) models using the genotypic information of 105 individuals with ASD and 171 unaffected/unrelated controls; corrections were conducted by the Bonferroni method. Linear regression and quantitative trait association modeled the severity of common ASD traits as a function of the 5-HTTLPR genotype. The family-based association for the 5-HTTLPR genotype and ASD was evaluated with the transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) using genotypic information of 105 trios. For the meta-analysis, the allelic and genotypic frequencies were included as a common measure to evaluate the association between 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and psychiatric disorders in Latin American population. The heterogeneity across studies was estimated by the Cochran’s Q test and the pooled Odds Ratio (OR) was evaluated under allelic (L vs S) and genotypic (SS vs LL+LS)—(LL vs SS+SL) models with fixed-effect or random-effect models according to I2 value (Fixed-effect for I2 <50% and Random-effect for I2 > 50%). The publication bias was assessed with funnel plots and quantitatively evaluated with Egger’s regression and Begg’s rank correlation. The trim and fill method was used to estimate potential missing studies and the sensitivity analysis removing each study for every meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the stability of the results. All statistical analysis were performed with PLINK [35] and R studio program [36].

Results

The genotyping results of 105 trios and 171 unrelated controls are described in S1 and S2 Tables. The genotypic and allelic frequencies are summarized in Table 1 and full sample analysis including families and unrelated controls were consistent with frequencies predicted by Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p = 0.12).

Table 1. 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in Colombian individuals.

| Group | Genotype frequency | Allele frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | SL | SS | Total | L | S | |

| Father | 19 [18%] | 49 [47%] | 37 [35%] | 105 | 0.41 | 0.59 |

| Mother | 23 [22%] | 42 [40%] | 40 [38%] | 105 | 0.42 | 0.58 |

| Child with ASD | 22 [21%] | 42 [40%] | 41 [39%] | 105 | 0.41 | 0.59 |

| Unrelated controls | 38 [22%] | 89 [52%] | 44 [26%] | 171 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

Genotypic and allelic frequencies in ASD trios and unaffected individuals

Although a significant association between 5-HTTLPR and ASD was observed only under dominant model (SS vs SL+LL, (p = 0.022)) (S3 Table), after Bonferroni’s correction non-significant result was observed. Additionally, the transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) indicates a non-preferential transmission of either the short or long allele (χ2 = 0.0989, p = 0.75) (S4 Table).

Phenotypic features and comorbidities in individuals with ASD were analyzed according to genotype (S5 Table). Aggressive behaviors were the most common comorbidity reported followed by intellectual disability and epilepsy. The sex ratio was 6:1 (male-to-female) with mean age of 10,8 ± 7,8 years old. For reasons of statistical power, the analysis between 5-HTTLPR and autism severity was restricted to the three core ASD symptoms (S1 and S2 Tables). The mean score for each trait was similar among the three genotypes and statistical test confirmed a non-association (Table 2).

Table 2. Phenotypic traits.

| ADOS score in investigated dimension [Mean ± SD] | SS | SL | LL | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADOS Social communication | 5,6 ± 1,9 | 5,9 ± 1,8 | 5 ± 1,8 | 0.4936 |

| ADOS Restricted/Repetitive behaviors | 2,9 ± 1,6 | 2,8 ± 1,3 | 2,9 ± 1,6 | 0.964 |

| ADOS Social interaction | 8,4 ± 3 | 9 ± 2,7 | 8,2 ± 2,4 | 0.8907 |

Mean score and standard deviation to each trait is presented according to genotype.

A total of 52 publications with the keywords provided in PubMed database were initially filtered, but only 13 case-control studies met the inclusion criteria: two from Colombia, three from Mexico, one from Argentina and seven from Brazil. In ScienceDirect database we found an additional study from Brazil and in Scielo database we found four additional studies: two from Colombia, one from Mexico and one from Brazil. No response was obtained from the authors that were contacted. Thus, from a total of 112 filtered reports, only 18 fulfilled the inclusion criteria (S1 Fig), and the allelic frequencies of each study were separately registered for cases and controls (Table 3).

Table 3. Allelic frequencies reported in Latin American population.

| Country | Trait | Cases | Controls | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | S | L | Sample size | S | L | |||

| Colombia | ASD | 105 | 0.59 | 0.41 | 171 | 0.52 | 0.48 | Present study |

| Colombia | Bipolar disorder | 103 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 112 | 0.53 | 0.47 | [Ospina-Duque et al., 2000] [37] |

| Colombia | MDD | 68 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 68 | 0.45 | 0.55 | [Pérez-Olmos, et al., 2016] [38] |

| Colombia | Bipolar disorder | 133 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 120 | 0.59 | 0.41 | [Ramos, et al., 2012] [39] |

| Colombia | MDD | 59 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 59 | 0.44 | 0.56 | [Escobar, et al., 2011] [40] |

| Mexico | Obsessive‐compulsive disorder | 115 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 136 | 0.52 | 0.48 | [Camarena et al., 2001] [41] |

| Mexico | MDD | 104 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 335 | 0.60 | 0.40 | [Peralta-Leal et al., 2012] [42] |

| Mexico | ADHD | 78 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 56 | 0.55 | 0.45 | [Durán-González et al., 2018] [43] |

| Mexico | MDD and suicide attempt | 200 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 233 | 0.51 | 0.49 | [Sarmiento-Hernandez et al., 2019] [44] |

| Argentina | MDD | 95 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 107 | 0.47 | 0.53 | [Cajal et al., 2012] [45] |

| Brazil | Bipolar Disorder | 167 | 0.37 | 0.63 | 184 | 0.36 | 0.64 | [Neves et al., 2008] [46] |

| Brazil | Schizophrenia* | 39 | 0.42 | 0.58 | 98 | 0.38 | 0.62 | [Mendes De Oliveira et al., 1998] [47] |

| Brazil | Bipolar Disorder* | 47 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 98 | 0.38 | 0.62 | [Mendes De Oliveira et al., 1998] [47] |

| Brazil | Dysthimia~ | 62 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 197 | 0.38 | 0.62 | [Oliveira et al., 2000] [48] |

| Brazil | Bipolar disorder~ | 64 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 197 | 0.38 | 0.62 | [Oliveira et al., 2000] [48] |

| Brazil | MDD~ | 66 | 0.42 | 0.58 | 197 | 0.38 | 0.62 | [Oliveira et al., 2000] [48] |

| Brazil | Anxiety | 129 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 96 | 0.43 | 0.57 | [Bortoluzzi et al., 2014] [49] |

| Brazil | Suicide in depressed patients | 84 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 152 | 0.44 | 0.56 | [Segal, et al, 2006] [50] |

| Brazil | Epilepsy | 175 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 155 | 0.45 | 0.55 | [Schenkel et al., 2011] [51] |

| Brazil | ASD | 151 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 179 | 0.45 | 0.55 | [Longo, et al, 2009] [52] |

| Brazil | Schizophrenia—Bipolar disorder | 99 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 60 | 0.47 | 0.53 | [Krelling et al., 2008] [53] |

| Brazil | Obsessive‐compulsive disorder | 78 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 202 | 0.52 | 0.48 | [Meira-Lima et al., 2004] [54] |

ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder, MDD: Major Depressive Disorder, ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

*Two traits evaluated independently but using the same control group,

~Three traits evaluated independently but using the same control group

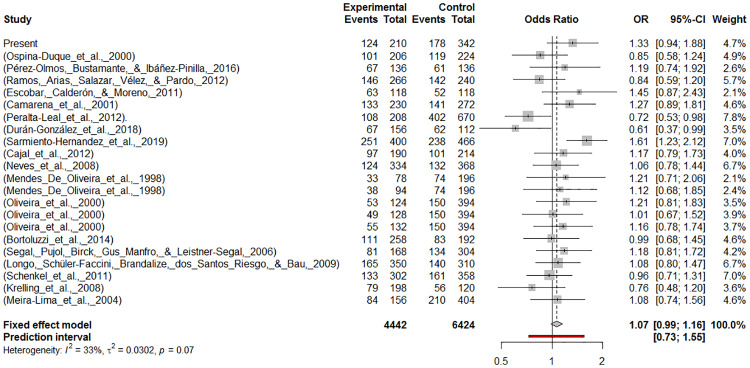

The Latin American meta-analysis performed under three models (S vs L), (SS vs SL+LL) and (LL vs SL+SS) reflected a heterogeneity of 33.1%, 19.5% and 13.7%, respectively (Table 4, Fig 1 and S2 Fig). Fixed-effect model was selected to estimate the pooled OR based on heterogeneity results. The overall OR in either of the three models failed to find significant association (Table 4) suggesting that the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism does not increase the risk for psychiatric disorders in Latin American population (Fig 1 and S2 Fig). For publication bias, the funnel plots suggested absence of a bias (S3 Fig) and both Egger´s and Begg’s test confirmed non significance (Table 4). The trim and fill method did not identified missing studies for each model (S4 Fig) and the recalculated OR did not yield different conclusions (Table 4) just like the sensitivity analysis (S6 Table).

Table 4. Results of meta-analysis.

| Genetic model | Meta-analysis | Heterogeneity | Bias | Recalculated OR with trim and fill method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled OR (95% CI) | p Value | I2 | p Value | Egger p value | Begg p value | Pooled OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| S vs L | 1.0698 [0.9880; 1.1584] | 0.0962 | 33.1% | 0.0673 | 0.5125 | 0.9775 | 1.0625 [0.9593; 1.1769] | 0.2306 |

| SS vs SL+LL | 1.1008 [0.9644; 1.2565] | 0.1548 | 19,5% | 0.2034 | 0.5359 | 0.7997 | 1.0913 [0.9355; 1.2730] | 0.2513 |

| LL vs SL+SS | 0.9146 [0.8066; 1.0371] | 0.1641 | 13,7% | 0.2766 | 0.636 | 0.8435 | 0.9218 [0.7975; 1.0654] | 0.2550 |

Fig 1. Meta-analysis evaluating 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in Latin American population.

Forest plot for the allelic model. The trait and country for each study are found in Table 3. The forest plots for other two models are found in S2 Fig.

Discussion

The serotonin re-uptake transporter (SERT) located in presynaptic neuron removes this neurotransmitter from the synaptic cleft, regulates the serotonin concentration in the synapse and controls the magnitude or duration of post-synaptic transmission. Single nucleotide, Indel and VNTR polymorphisms in the SLC6A4 gene have been implicated in the re-uptake efficiency; for example, the LL genotype of 5HTTLPR polymorphism is related with increased SERT concentration becoming the S carrier variants as a risk factor for psychiatric disorders [16–21,55].

The role of 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in the ASD pathophysiology evaluated through case-control studies and family-based association have reflected conflicting results. For instance, two studies suggested S allele as risk variant for ASD [15,16], while three meta-analysis did not find association [26–28]. We assessed this polymorphism through a case-control approach failing to find association between 5-HTTLPR and idiopathic ASD, and also through a family-based assessment that did not find a preferential transmission of either S or L allele. A previous evaluation of this polymorphism in Colombian individuals with ASD also failed to find a significant association [56].

Phenotypic heterogeneity in ASD has been also studied in relation with the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, two reports suggested an association of the S allele with higher severity in social communication impairment [57,58], while another group associated the severity of this trait with the LL genotype for 5-HTTLPR and the AA genotype for rs25531 [59]. Brune et al., 2006 also reported the LL genotype associated with severity of repetitive behaviors [58]. In our study, we did not find an association between 5-HTTLPR genotype and severity in the three core ASD symptoms (repetitive/restricted behaviors, impairment in social interaction and variable communication skills) just like other three reports [52,60,61]. An association between aggressive behaviors and the serotoninergic system has been also suggested [13,60,62,63]; in our study we observed that self-injury behaviors were mainly reported in individuals with the SS genotype (15/29), and although we did not find a significant association (p>0.05) our sample size does not have the statistical power to reveal this association. A summary of these conflicting results is presented in S7 Table.

Replication of results across ethnicities has been postulated as a good strategy to discover true risk variants or to understand if the lack of replication reflects the complexity in the genetic architecture of some complex disorders as ASD [64,65]. Although two meta-analyses recovering case-control studies mainly from European, American, and Asian population did not find association of this polymorphism with ASD, they also confirmed high heterogeneity in the included studies probably explained by population ethnicity [27,28]. These results suggest that the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism varies across ethnicities and the genetic background of each population may have a role in the risk conferred by this polymorphism [64,65].

Recognizing the under-representation of Latin American population in studies aimed to understand the role of 5-HTTLPR on worldwide [26,27,29], here we present a meta-analysis including articles which evaluate this polymorphism in Latin American individuals with psychiatric disorders as ASD, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, attention deficit hyperactive disorder, schizophrenia, dysthymia, anxiety disorder and suicide [37–54]. Although the S allele has been associated with increased risk for psychiatric disorders [16–21,55], our meta-analysis revealed no significant heterogeneity among studies, no publication bias and failed to find an association between 5-HTTLPR and a risk for psychiatric disorders. Comparing our frequencies with frequencies reported in other continents, the Latin American frequencies are more similar to those reported in Caucasian population [62,66–68], while S allele has been greater in Asian population [69,70] and L allele greater in African population [70,71]. Nevertheless, none of Latin American studies had a strict genetic control for population substructure between cases and controls and according to previous reports the Brazilian population should have an over-representation of African component in some regions [72–74]. Even though Latin America presents a diverse population substructure, most of the regions presented in the meta-analysis are likely to have an elevated Caucasian component compared to native American and African backgrounds [70,75,76]; however, slight differences may not be discarded in some small or separate regions according to demographic history of these admixed countries [72–76].

In summary, our study supports the absence of association between ASD and 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in a homogeneous cohort of Colombian individuals with idiopathic ASD. Additionally, a meta-analysis evaluating this polymorphism in Latin American regions suggests that frequencies of short/long alleles in this under-represented population are relatively homogeneous to frequencies reported in Caucasian populations.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

TDT was performed with families having heterozygotes parents (49 fathers and 42 mothers).

(DOCX)

Two sub-categories were well-thought-out, patients who loss the acquired skills at 2 years old were classified as “ASD with regressive development” and patients with ASD and higher cognitive skills were classified as “High functioning ASD”. Intellectual disability was evaluated during clinical consultation without standardized test. Aggressive behaviors were analyzed according to ADIR reports.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

This table summarizes some results of studies evaluating severity of ASD symptoms and the serotoninergic system.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

The trait and country for each study and are in Table 3. a. Forest plot for SS vs SL+LL model, b. Forest plot for LL vs SL+SS model.

(TIF)

a. Funnel plot for S vs L model b. Funnel plot for SS vs SL+LL model, c. Funnel plot for LL vs SL+SS model.

(TIF)

Funnel plots without missing studies a. for S vs L model, b. for SS vs SL+LL model and c. for LL vs SL+SS model.

(TIF)

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

The authors are pleased to acknowledge the participant families and Instituto Colombiano del Sistema Nervioso Clínica Monserrat. Special thanks to Silvia Gonzalez Nieves, Daniela Castellanos and Camila Velasco from Universidad de Los Andes.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

MCL: Grant # 120474455837 (744-2016) from Minciencias, previously known as Colciencias MCL: Grant Heterogeneidad Genetica del Autismo. Vicerrectoria de investigaciones -Universidad de Los Andes DLN: scholarship from Ceiba.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association. DSM. 2013.

- 2.D’Abate L, Walker S, Yuen RKC, Tammimies K, Buchanan JA, Davies RW, et al. Predictive impact of rare genomic copy number variations in siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2019;10(1):5519 Available from: 10.1038/s41467-019-13380-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubenstein E, Wiggins LD, Schieve LA, Bradley C, DiGuiseppi C, Moody E, et al. Associations between parental broader autism phenotype and child autism spectrum disorder phenotype in the Study to Explore Early Development. Autism. 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grove J, Ripke S, Als TD, Mattheisen M, Walters RK, Won H, et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Genet. 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satterstrom FK, Kosmicki JA, Wang J, Breen MS, De Rubeis S, An JY, et al. Large-Scale Exome Sequencing Study Implicates Both Developmental and Functional Changes in the Neurobiology of Autism. Cell. 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pilorge M, Fassier C, Le Corronc H, Potey A, Bai J, De Gois S, et al. Genetic and functional analyses demonstrate a role for abnormal glycinergic signaling in autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2016; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satterstrom FK, Kosmicki JA, Wang J, Breen MS, De Rubeis S, An J-Y, et al. Novel genes for autism implicate both excitatory and inhibitory cell lineages in risk. bioRxiv. 2018; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doan RN, Lim ET, De Rubeis S, Betancur C, Cutler DJ, Chiocchetti AG, et al. Recessive gene disruptions in autism spectrum disorder. Nature Genetics. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heils Armin Teufel Andreas Petri Susanne Stöber Gerald Riederer Peter Dietmar B, Heils A, Teufel A, Petri S, Stober G, Riederer P, et al. Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression. J Neurochem. 1996; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belmer A, Klenowski PM, Patkar OL, Bartlett SE. Mapping the connectivity of serotonin transporter immunoreactive axons to excitatory and inhibitory neurochemical synapses in the mouse limbic brain. Brain Struct Funct. 2017; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai X, Kallarackal AJ, Kvarta MD, Goluskin S, Gaylor K, Bailey AM, et al. Local potentiation of excitatory synapses by serotonin and its alteration in rodent models of depression. Nat Neurosci. 2013; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciranna L. Serotonin as a Modulator of Glutamate- and GABA-Mediated Neurotransmission: Implications in Physiological Functions and in Pathology. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garbarino VR, Gilman TL, Daws LC, Gould GG. Extreme enhancement or depletion of serotonin transporter function and serotonin availability in autism spectrum disorder. Pharmacological Research. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller CL, Anacker AMJ, Veenstra-VanderWeele J. The serotonin system in autism spectrum disorder: From biomarker to animal models. Neuroscience. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gebril O, Khalil R, Meguid N. A study of blood serotonin and serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism in Egyptian autistic children. Adv Biomed Res. 2015; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arieff Z, Kaur M, Gameeldien H, Van Der Merwe L, Bajic VB. 5-HTTLPR polymorphism: Analysis in South African autistic individuals. Hum Biol. 2010; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Culverhouse RC, Saccone NL, Horton AC, Ma Y, Anstey KJ, Banaschewski T, et al. Collaborative meta-Analysis finds no evidence of a strong interaction between stress and 5-HTTLPR genotype contributing to the development of depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2018; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S. The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited: Evidence of genetic moderation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ancelin ML, Scali J, Norton J, Ritchie K, Dupuy AM, Chaudieu I, et al. Heterogeneity in HPA axis dysregulation and serotonergic vulnerability to depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharpley CF, Palanisamy SKA, Glyde NS, Dillingham PW, Agnew LL. An update on the interaction between the serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress and depression, plus an exploration of non-confirming findings. Behavioural Brain Research. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang H yan, Qiao F, Xu X feng, Yang Y, Bai Y, Jiang L ling. Meta-analysis confirms a functional polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) in the serotonin transporter gene conferring risk of bipolar disorder in European populations. Neurosci Lett. 2013; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng P, Zhang J, Wu Y, Liu W, Zhu J, Chen Z, et al. 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and depression risk in Parkinson’s disease: an updated meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Belg [Internet]. 2020; 10.1007/s13760-020-01342-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serretti A, Cusin C, Lattuada E, Di Bella D, Catalano M, Smeraldi E. Serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) is not associated with depressive symptomatology in mood disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 1999; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunugi H, Hattori M, Kato T, Tatsumi M, Sakai T, Sasaki T, et al. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms: Ethnic difference and possible association with bipolar affective disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 1997; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Miller AL, Kennedy MA. Life stress, 5-HTTLPR and mental disorder: Findings from a 30-year longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang PY, Menga YJ, Li T, Huang Y. Associations of endocrine stress-related gene polymorphisms with risk of autism spectrum disorders: Evidence from an integrated meta-analysis. Autism Research. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H, Yin F, Gao J, Fan X. Association Between 5-HTTLPR Polymorphism and the Risk of Autism: A Meta-Analysis Based on Case-Control Studies. Front psychiatry [Internet]. 2019. February 13;10:51 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30814960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang CH, Santangelo SL. Autism and serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sleeswijk AW, Heijungs R, Durston S. Tackling missing heritability by use of an optimum curve: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lord C, Rutter M, Goode S, Heemsbergen J, Jordan H, Mawhood L, et al. Austism diagnostic observation schedule: A standardized observation of communicative and social behavior. J Autism Dev Disord. 1989; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, Dilavore PC, et al. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petri S, Riederer P, Heils A, Lesch KP, Bengel D, Stober G, et al. Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression. J Neurochem. 1996; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J AD. PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram. The PRISMA statement. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ospina-Duque J, Duque C, Carvajal-Carmona L, Ortiz-Barrientos D, Soto I, Pineda N, et al. An association study of bipolar mood disorder (type I) with the 5-HTTLPR serotonin transporter polymorphism in a human population isolate from Colombia. Neurosci Lett. 2000; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pérez-Olmos I, Bustamante D, Ibáñez-Pinilla M. Serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT) polymorphism and major depressive disorder in patients in bogotá, Colombia. Biomedica. 2016; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramos LR, Arias DG, Salazar LS, Vélez JP, Pardo SL. Polimorfismos en el gen del transportador de serotonina (SLC6A4) y el trastorno afectivo bipolar en dos centros regionales de salud mental del Eje Cafetero*. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2012; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Escobar CH, Calderón JH, Moreno GA. Allelic polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene in major depression patients TT—Polimorfismos alélicos del gen del transportador de serotonina en pacientes con depresión mayor. Colomb Med. 2011; [Google Scholar]

- 41.Camarena B, Rinetti G, Cruz C, Hernández S, Ramón De La Fuente J, Nicolini H. Association study of the serotonin transporter gene polymorphism in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peralta-Leal V, Leal-Ugarte E, Meza-Espinoza JP, Gutiérrez-Angulo M, Hernández-Benítez CT, García-Rodríguez A, et al. Association of serotonin transporter gene polymorphism 5-HTTLPR and depressive disorder in a Mexican population. Psychiatric Genetics. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Durán-González J, Leal-Ugarte E, Cruz-Alcalá LE, Gutiérrez-Angulo M, Gallegos-Arreola MP, Meza-Espinoza JP, et al. Association of the SLC6A4 gene 5HTTLPR polymorphism and ADHD with epilepsy, gestational diabetes, and parental substance abuse in Mexican mestizo children. Salud Ment. 2018; [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarmiento-Hernandez EI, Ulloa-Flores RE, Camarena-Medellin B, Sanabrais-Jimenez MA, Aguilar-Garcia A, Hernandez-Munoz S. Association between 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, suicide attempt and comorbidity in Mexican adolescents with major depressive disorder. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2019. January;47(1):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cajal AR, Redal MA, Costa LD, Lesik LA, Faccioli JL, Finkelsztein CA, et al. Influence of 5-HTTLPR and 5-HTTVNTR polymorphisms of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) on major depressive disorder in a sample of Argentinean population. Psychiatr Genet. 2012; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neves FS, Silveira G, Romano-Silva MA, Malloy-Diniz L, Ferreira AA, De Marco L, et al. Is the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism associated with bipolar disorder or with suicidal behavior of bipolar disorder patients? Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mendes De Oliveira JR, Otto PA, Vallada H, Lauriano V, Elkis H, Lafer B, et al. Analysis of a novel functional polymorphism within the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT) in Brazilian patients affected by bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet—Neuropsychiatr Genet. 1998; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oliveira JRM, Carvalho DR, Pontual D, Gallindo RM, Sougey EB, Gentil V, et al. Analysis of the serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) in Brazilian patients affected by dysthymia, major depression and bipolar disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bortoluzzi A, Blaya C, Salum GA, Cappi C, Leistner-Segal S, Manfro GG. Anxiety disorders and anxiety-related traits and serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) in adolescents: Case-control and trio studies. Psychiatr Genet. 2014; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Segal J, Pujol C, Birck A, Gus Manfro G, Leistner-Segal S. Association between suicide attempts in south Brazilian depressed patients with the serotonin transporter polymorphism. Psychiatry Res. 2006; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schenkel LC, Bragatti JA, Torres CM, Martin KC, Manfro GG, Leistner-Segal S, et al. Serotonin transporter gene (5HTT) polymorphisms and temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2011; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Longo D, Schüler-Faccini L, Brandalize APC, dos Santos Riesgo R, Bau CHD. Influence of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and environmental risk factors in a Brazilian sample of patients with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res. 2009; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krelling R, Cordeiro Q, Miracca E, Gutt EK, Petresco S, Moreno RA, et al. Molecular genetic case-control women investigation from the first Brazilian high-risk study on functional psychosis. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meira-Lima I, Shavitt RG, Miguita K, Ikenaga E, Miguel EC, Vallada H. Association analysis of the catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT), serotonin transporter (5-HTT) and serotonin 2A receptor (5HT2A) gene polymorphisms with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Genes, Brain Behav. 2004; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kenna GA, Roder-Hanna N, Leggio L, Zywiak WH, Clifford J, Edwards S, et al. Association of the 5-HTT gene-linked promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with psychiatric disorders: Review of psychopathology and pharmacotherapy. Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Medicine. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valencia AV, Páez AL, Sampedro ME, Ávila C, Cardona JC, Mesa C, et al. Evidencia de asociación entre el gen SLC6A4 y efectos epistáticos con variantes en HTR2A en la etiología del autismo en la población antioqueña. Biomedica. 2012; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tordjman S, Gutknecht L, Carlier M, Spitz E, Antoine C, Slama F, et al. Role of the serotonin transporter gene in the behavioral expression of autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2001; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brune CW, Kim SJ, Salt J, Leventhal BL, Lord C, Cook EH. 5-HTTLPR genotype-specific phenotype in children and adolescents with autism. Am J Psychiatry. 2006; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ, Siegal VI, Olvet DM, Kibria S, Kirsch SF, et al. Allele-specific associations of 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 with ADHD and autism spectrum disorder. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2013; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kolevzon A, Newcorn JH, Kryzak L, Chaplin W, Watner D, Hollander E, et al. Relationship between whole blood serotonin and repetitive behaviors in autism. Psychiatry Res. 2010; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jaiswal P, Guhathakurta S, Singh AS, Verma D, Pandey M, Varghese M, et al. SLC6A4 markers modulate platelet 5-HT level and specific behaviors of autism: A study from an Indian population. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tassone F, Pan R, Amiri K, Taylor AK, Hagerman PJ. A rapid polymerase chain reaction-based screening method for identification of all expanded alleles of the fragile X (FMR1) gene in newborn and high-risk populations. J Mol Diagnostics. 2008; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Daly E, D. Tricklebank M, Wichers R. Chapter Two—Neurodevelopmental roles and the serotonin hypothesis of autism spectrum disorder. In: Tricklebank MD, Daly EBT-TSS, editors. Academic Press; 2019. p. 23–44. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128133231000025

- 64.Greene CS, Penrod NM, Williams SM, Moore JH. Failure to replicate a genetic association may provide important clues about genetic architecture. PLoS One. 2009; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sirugo G, Williams SM, Tishkoff SA. The Missing Diversity in Human Genetic Studies. Cell. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Odgerel Z, Talati A, Hamilton SP, Levinson DF, Weissman MM. Genotyping serotonin transporter polymorphisms 5-HTTLPR and rs25531 in European- and African-American subjects from the National Institute of Mental Health’s Collaborative Center for Genomic Studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2013; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nyffeler J, Walitza S, Bobrowski E, Gundelfinger R, Grünblatt E. Association study in siblings and case-controls of serotonin- and oxytocin-related genes with high functioning autism. J Mol Psychiatry. 2014; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bondy B, Erfurth A, De Jonge S, Krüger M, Meyer H. Possible association of the short allele of the serotonin transporter promoter gene polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) with violent suicide. Mol Psychiatry. 2000; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Long H, Liu B, Hou B, Wang C, Kendrick KM, Yu C, et al. A potential ethnic difference in the association between 5-HTTLPR polymorphisms and the brain default mode network. Chinese Sci Bull. 2014; [Google Scholar]

- 70.Murdoch JD, Speed WC, Pakstis AJ, Heffelfinger CE, Kidd KK. Worldwide population variation and haplotype analysis at the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4 and implications for association studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2013; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Esau L, Kaur M, Adonis L, Arieff Z. The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in South African healthy populations: A global comparison. J Neural Transm. 2008; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Souza AM, Resende SS, de Sousa TN, de Brito CFA. A systematic scoping review of the genetic ancestry of the brazilian population. Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gontijo CC, Mendes FM, Santos CA, Klautau-Guimarães M de N, Lareu MV, Carracedo Á, et al. Ancestry analysis in rural Brazilian populations of African descent. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2018; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chor D, Pereira A, Pacheco AG, Santos RV, Fonseca MJM, Schmidt MI, et al. Context-dependence of race self-classification: Results from a highly mixed and unequal middle-income country. PLoS One. 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ossa H, Aquino J, Pereira R, Ibarra A, Ossa RH, Pérez LA, et al. Outlining the ancestry landscape of Colombian admixed populations. PLoS One. 2016; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adhikari K, Chacón-Duque JC, Mendoza-Revilla J, Fuentes-Guajardo M, Ruiz-Linares A. The Genetic Diversity of the Americas. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]