To the Editor:

The accumulating evidence suggests that viral-bacterial interactions can affect short- and long-term outcomes of acute respiratory infections (ARIs) due to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in infancy. In particular, prior studies have found that in young children with RSV ARIs, a higher relative abundance of Haemophilus in the nasopharynx is associated with an increased viral load,1 delayed viral clearance,2 a different gene expression profile,3 , 4 and more severe disease.3 , 4 However, the mechanisms underlying these associations are largely unknown. To address this gap in knowledge, we examined the association of the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus with viral load and 52 local immune mediators in 105 infants with an RSV-only ARI (ie, no coinfections) who were enrolled in the Infant Susceptibility to Pulmonary Infections and Asthma following RSV Infection in Infancy (INSPIRE) study.

The INSPIRE cohort is a population-based, birth cohort of healthy, term infants born in middle Tennessee with biweekly surveillance of acute respiratory symptoms during their first winter viral season to capture their initial RSV ARI. Infants who met prespecified criteria for an ARI underwent an in-person visit, which included collection of a nasal wash that was used for RSV detection and viral load assessment by real-time RT-PCR. This nasal wash has also been used for characterization of the nasopharyngeal microbiome and local immune response through 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing and measurement of multiple local immune mediators (ie, cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors) by using Luminex xMAP technology (see Table E1 in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org), respectively, as previously described.5 , 6 In brief, following bacterial DNA extraction, we amplified the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene by using universal primers. The libraries were then sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform with 2 × 300-bp reads. We subsequently processed the 16S rRNA paired sequences by using the dada2 pipeline, after which we grouped sequences into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) and assigned taxonomy using the SILVA reference database. We used the relative abundance of Haemophilus and Haemophilus ASVs (expressed as simple proportions) for statistical analyses. In addition, we used the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool to search the ASV sequences against a reference database and available whole metagenomic sequencing (WMS) from a selected number of nasal washes (n = 6) to identify Haemophilus species. The Luminex xMAP data were processed by using a method involving use of median fluorescence intensities of individual beads instead of the usual standard curve-based data processing method to increase the sensitivity and accuracy of high-throughput immunoassays.6 To examine the unadjusted and adjusted associations of the relative abundance of Haemophilus and Haemophilus ASVs with RSV viral load and the local immune mediator median fluorescence intensities, we used Spearman correlation and multivariable linear regression, respectively. Our primary models included the infant’s age at the time of the RSV ARI, sex, and race and ethnicity as covariates. We also created secondary models replacing race and ethnicity with maternal asthma. The statistical analyses were conducted with R software. We used the Benjamini and Hochberg method to control for multiple comparisons when appropriate. One parent of each infant provided informed consent for the infant's participation. The institutional review board of Vanderbilt University Medical Center approved this study. Further details are also available in the Online Repository (available at www.jacionline.org).

Of the 309 infants with RSV-only ARIs who were enrolled in the INSPIRE study, 105 (∼34%) had at least 1 nasal wash with 16S rRNA sequencing and immune mediator data available (obtained as part of separate projects5 , 6) and were thus included in our study. The median age at the RSV ARI in these 105 infants was 4.90 months (interquartile range [IQR] = 3.06-6.15 months). The majority of these infants were male, white non-Hispanic, and born via vaginal delivery (see Table E2 in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Compared with the infants included in the study, those not included were more likely to be born via vaginal delivery and to have federal or state insurance (see Table E2).

The median viral load, as measured by the number of cycle threshold values, was 23.81 (IQR = 20.78-26.91) in all infants. There was no association between the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus and the viral load in unadjusted (Spearman ρ = –0.04; P = .7) or adjusted (β coefficient = –1.82; 95% CI = –5.76-2.13; P = .4) analyses.

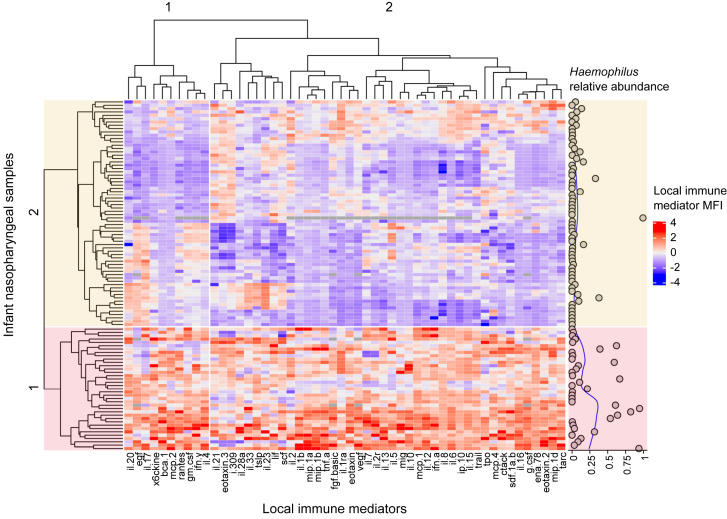

Using unsupervised methods, we identified 2 clusters of infants based on their nasopharyngeal immune response patterns (Fig 1 ). Cluster 1 mostly comprised infants with higher local immune mediator levels when compared with cluster 2. Cluster 1 also mainly included infants with a higher relative abundance of Haemophilus in their nasopharynx (Fig 1), with the median relative abundance of cluster 1 (0.03 [IQR = 0.003-0.39]) being approximately 15 times higher than that of cluster 2 (0.002 [IQR = 0-0.03]) (P = .001 with use of the Mann-Whitney U test).

Fig 1.

Heatmap of local immune mediators (columns) measured in nasopharyngeal samples (rows) collected during an ARI due to RSV in infancy. The nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus in each sample with a corresponding fitted loess curve (blue line) is also shown (right panel). The columns and rows were hierarchically clustered by using the complete linkage method based on Spearman correlation coefficients or euclidean distances, respectively. The color of each cell represents the generalized log–transformed median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the respective local immune mediator in an individual sample after subtracting the column mean and dividing it by its standard deviation as shown in the color scale (blue indicates lower, red indicates higher, and gray indicates missing). The heatmap shows 2 distinct clusters of samples (colored in red and yellow). Cluster 1 is characterized by higher MFIs of most local immune mediators, as well as by an increased nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus.

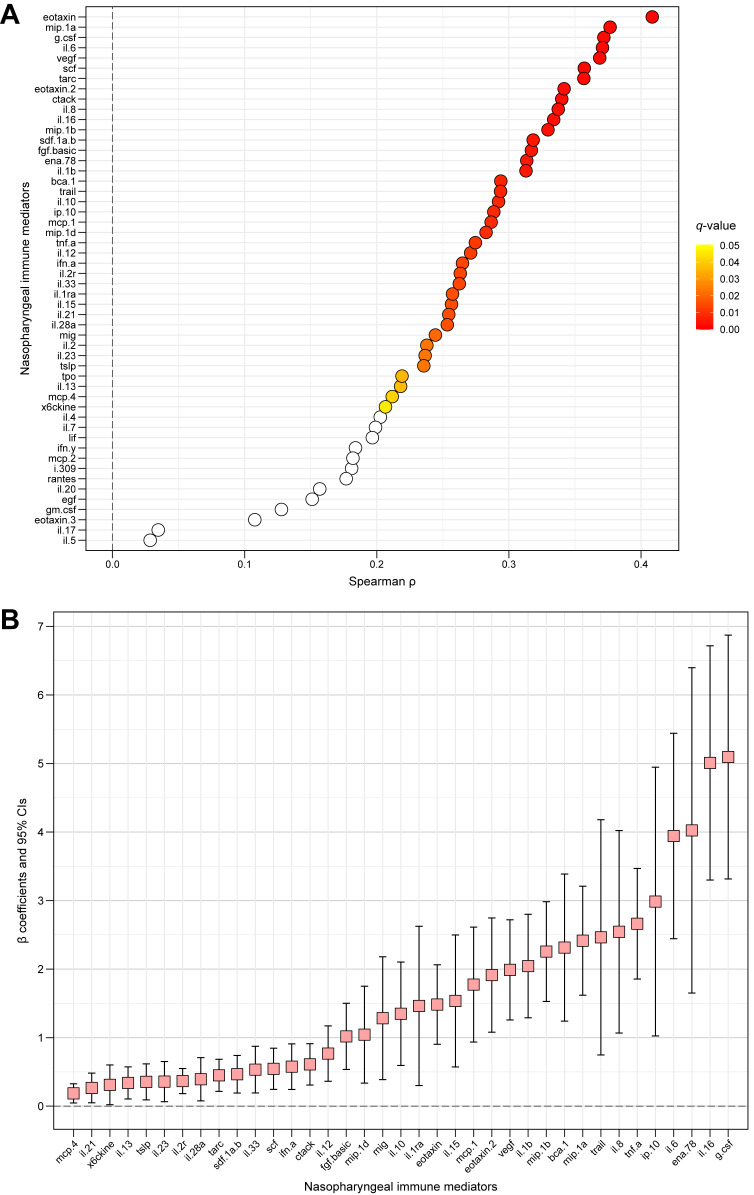

In unadjusted analyses, the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus was positively correlated with the levels of 39 of the 52 local immune mediators (∼75%) after control for multiple comparisons (Fig 2 , A and see Table E3 in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). These associations remained significant for 37 of the 52 local immune mediators (∼71%) after adjustment for potential confounders in our primary and secondary models (Fig 2, B and see Table E3). In general, the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus was associated with higher levels of those local immune mediators with antiviral and/or proinflammatory functions and those that are important in the chemotaxis, differentiation, proliferation, and survival of numerous immune cells (eg, TNF-α, IFN-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-21, and IL-28A). In contrast, nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus was not associated with the levels of the main type 1 (eg, IFN-γ) or type 3 (eg, IL-17A) local immune mediators. In regard to type 2 immune responses, there was a positive association with IL-13, but not with IL-4 or IL-5, which may be related to the temporal expression of these cytokines. The nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus was also associated with IL-33 (Fig 2). Interestingly, IL-33 can induce a type 2 immune response either through activating ILC2 or CD4+ TH2 cells and animal studies have shown that IL-33 is important for RSV pathophysiology.7

Fig 2.

The unadjusted and adjusted association of the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus with each measured local immune mediator’s median fluorescence intensity during an RSV ARI in infancy. A, Unadjusted analyses performed by using Spearman correlation. The Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) are indicated by circles and colored by their respective P values after controlling for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini and Hochberg method (ie, q values). The nonsignificant q values of 0.05 or more are shown in white, whereas those less than 0.05 are shown according to the color scale (yellow indicates higher, red indicates lower). B, Adjusted analyses performed by using multivariate linear regression. The β coefficients are indicated by squares, and their corresponding 95% CIs are indicated by the adjacent black lines. Each multivariable model included the infant’s age at the time of RSV ARI, race and ethnicity, and sex as covariates. The β coefficient can be interpreted as the increase in that local immune mediator’s generalized-log-transformed median fluorescence intensity per 1% increase in the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus during an RSV ARI after control for these covariates. Only those immune mediators with q values that were less than 0.05 in unadjusted analyses and remained significant in adjusted analyses are shown.

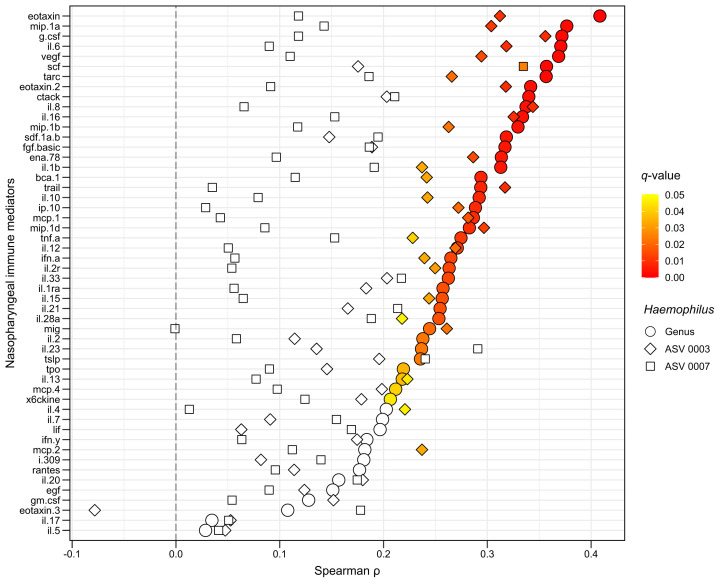

To explore whether this effect was attributable to a single Haemophilus species, we repeated the aforementioned statistical analyses for the most abundant Haemophilus ASVs. In all infants, a total of 81 Haemophilus ASVs were identified, with 4 of them accounting for approximately 95% of all Haemophilus sequences. The nasopharyngeal relative abundance of 2 of these 4 Haemophilus ASVs had a direction of associations similar to those noted in the genus-level analyses (with 1 of these being correlated with the levels of 28 of the 52 local immune mediators [∼54%] after control for multiple comparisons [see Fig E1 in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org]). When we used the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool and the available WMS data, both of these Haemophilus ASVs most likely corresponded to Haemophilus influenzae strains (see the Results section in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

Fig E1.

The unadjusted associations of the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of the top 2 most frequent Haemophilus ASVs with each measured local immune mediator’s median fluorescence intensity (MFI) during an ARI due to RSV in infancy. The unadjusted analyses were conducted by using Spearman correlation. The Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) for each Haemophilus ASV are indicated by shapes (diamond indicates ASV 0003, squares indicate ASV 0007) and colored by their respective P values after control for multiple comparisons by using the Benjamini and Hochberg method (ie, q values). The nonsignificant q values or 0.05 or higher are shown in white, whereas those that are less than 0.05 are shown according to the color scale (yellow indicates higher, red indicates lower). The estimates for the unadjusted associations at the genus level are also shown as a reference (circles). The local immune mediator MFIs were generalized log–transformed before all statistical analyses.

Several members of the genus Haemophilus are commonly found in the nasopharynx of healthy infants, although usually at low relative abundances. The aggregated evidence suggests that early-life RSV ARIs can lead to a rapid increase in the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus throughout infancy (a critical period of lung and immune development) and that this could in turn affect the pathophysiology of RSV disease.1, 2, 3, 4 In our study, we have shown that the relative abundance of Haemophilus (most likely H influenzae) in the nasopharynx during an RSV ARI in infancy is positively associated with multiple local immune mediators, particularly those with antiviral and proinflammatory functions, which could be a mechanism through which these viral-bacterial interactions influence short- and long-term RSV-related outcomes. One prior study found that a nasopharyngeal microbial profile dominated by Haemophilus was associated with delayed viral clearance during RSV ARI in infancy2; although exactly how the combination of antiviral and proinflammatory immune responses affect viral clearance during RSV ARI in infancy is unknown. To our knowledge, only 1 other study has examined the effect of nasopharyngeal Haemophilus on the local immune response during an RSV ARI in infancy. That study was smaller, used ELISA-based immunoassays, and included only 4 of the 52 local immune mediators examined by us, finding similar results for IL-8.1 Likewise, 2 in vitro studies found similar results for IL-6 and IL-8, which also supports our findings.8 , 9

Our study has multiple strengths, including the population-based design of the parent study, the close surveillance during the infants’ first winter viral season to capture their initial RSV ARI, the use of next-generation sequencing and high-throughput immune assays, and the use of statistical analysis adjusting for potential confounders. We also acknowledge several limitations. First, we decided to focus on Haemophilus because of the multiple prior studies assessing the whole nasopharyngeal microbiome that have identified this taxon as a key determinant of RSV-related outcomes1, 2, 3, 4 even though it is certainly possible that Haemophilus could be just a marker for other bacterial pathogens or that other taxa could also have important or stronger immunomodulatory effects. Second, our sample size was small, and it may not have been powered to detect certain associations. The number of nasal washes with WMS data was also limited; therefore, the WMS analyses should be regarded as exploratory, as it is possible that we did not capture all relevant Haemophilus species. Third, it is possible that some of the associations found were driven by a small number of observations, as the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus was overall low in most infants. However, several of the statistical tests that we used are robust to the effect of outliers. Furthermore, the effect of a particular species on a microbial ecosystem is not directly related to its abundance. Thus, Haemophilus could be a crucial taxon affecting the RSV-related local immune response in infancy, even at low nasopharyngeal relative abundances. Lastly, our study included only a subset of RSV-infected infants from the INSPIRE cohort, and it had a cross-sectional design. Thus, there is a possibility of selection bias and/or reverse causation (ie, a possibility that the levels of certain local immune mediators are what affect the relative abundance of Haemophilus in the nasopharynx). In spite of these limitations, our study adds to the small but increasing literature on the effect of RSV and Haemophilus interactions on common childhood respiratory diseases.

Footnotes

Supported by funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (under awards U19AI095227, K24AI77930, HHSN272200900007C, R21AI142321, and U19AI110819); the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (under awards K23HL148638 and R01HL146401); the Parker B. Francis Fellowship Program; the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (grant support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under award UL1TR000445); and the Vanderbilt Technologies for Advanced Genomics Core (grant support from the National Institutes of Health under awards UL1RR024975, P30CA68485, P30EY08126, and G20RR030956).

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Results

In the 105 RSV-infected infants included in the study, a total of 81 Haemophilus ASVs were identified, and 4 of these accounted for approximately 95% of all Haemophilus sequences. The 2 Haemophilus ASVs with the highest nasopharyngeal relative abundance, ASV 0003 and ASV 0007, accounted for approximately 87% of all Haemophilus sequences. These 2 Haemophilus ASVs also had a direction of associations similar to those noted in the genus-level analyses. After control for multiple comparisons, the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of 1 of these ASVs (Haemophilus ASV 0003) was correlated with the levels of 28 of the 52 local immune mediators (∼54%), whereas the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of the other ASV (Haemophilus ASV 0007) was correlated only with the level of 1 of the 52 local immune mediators (∼2%) (Fig E1).

To identify Haemophilus species, we first used BLAST to search against the nucleotide sequence database.E17 The ASV 0003 sequence was a 100% match with 2 classified Haemophilus species (H influenzae [79 of 112 hits (∼71%)] and Haemophilus haemolyticus [31 of 112 hits (∼28%)]; e value = 4e–132 for both species). Likewise, the ASV 0007 sequence was a 100% match with 2 classified Haemophilus species (H influenzae [114 of 120 hits (∼95%)]) and Haemophilus aegyptius [2 of 120 hits (∼2%)]; e value = 4e–132 for both species). To further differentiate between these Haemophilus species, we then used the WMS data that were available for 6 of the infants included in the study. Two of these infants had Haemophilus detected by 16S rRNA sequencing, and in both of them, the only Haemophilus species detected by WMS was H influenzae, suggesting that the Haemophilus ASVs 0003 and 0007 corresponded to H influenzae strains.

Table E1.

The nasopharyngeal immune mediators measured during an ARI due to RSV in infants that were included in the study

|

|

|

The nasopharyngeal immune mediators are presented in alphabetical order.

The levels of HGF were undetectable in approximately 50% of the nasopharyngeal samples, and because of this, this immune mediator was excluded from statistical analyses.

Table E2.

Baseline characteristics of the infants enrolled in the INSPIRE study with an RSV-only ARI included (n = 105) and not included (n = 204) in our study

| Included (n = 105) | Not included (n = 204) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at the time of the RSV ARI (mo) | 4.90 (3.06-6.15) | 4.62 (2.45-5.98) |

| Female sex | 45 (42.86%) | 96 (47.06%) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Black non-Hispanic | 12 (11.43%) | 37 (18.14%) |

| White non-Hispanic | 74 (70.48%) | 134 (65.69%) |

| Hispanic | 11 (10.48%) | 16 (7.84%) |

| Other | 8 (7.62%) | 17 (8.33%) |

| Gestational age (wk) | 39 (39-40) | 39 (38-40) |

| Birth weight (g) | 3507 (3149-3774) | 3405 (3105-3714) |

| Birth by cesarean section | 42 (40.00%) | 59 (28.92%) |

| Ever any breast-feeding in infancy | 85 (82.52%) | 149 (76.80%) |

| Exposure to secondhand smoking in utero or before enrollment | 21 (20.00%) | 56 (27.45%) |

| Maternal asthma | 17 (16.19%) | 44 (21.57%) |

| Federal or state insurance at enrollment | 39 (37.14%) | 122 (59.80%) |

Data are presented as medians (25th-75th percentiles) for continuous variables or number (%) for categoric variables and are calculated for children with complete data. P < .05 for the comparison between groups that was performed by using a Mann-Whitney U test or Pearson chi-square test, as appropriate.

Table E3.

The unadjusted and adjusted associations of the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus with each measured local immune mediator’s MFI during an RSV ARI in infancy

| Nasopharyngeal immune mediator | Sample size available for statistical analyses | Unadjusted analyses∗ |

Adjusted analyses† |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||||||

| Spearman ρ | P value | q value | β coefficient | 95% lower CI | 95% upper CI | β coefficient | 95% lower CI | 95% upper CI | ||

| BCA.1 | 105/105 | 0.29 | .00235 | 0.00682 | 2.31 | 1.24 | 3.39 | 2.22 | 1.1 | 3.33 |

| CTACK | 105/105 | 0.34 | .00039 | 0.00224 | 0.61 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.59 | 0.29 | 0.89 |

| EGF | 101/105 | 0.15 | .13148 | 0.14244 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| ENA.78 | 105/105 | 0.31 | .00113 | 0.00402 | 4.02 | 1.65 | 6.40 | 3.69 | 1.26 | 6.13 |

| Eotaxin | 104/105 | 0.41 | .00002 | 0.00087 | 1.48 | 0.90 | 2.06 | 1.41 | 0.81 | 2.01 |

| Eotaxin.2 | 105/105 | 0.34 | .00036 | 0.00224 | 1.91 | 1.08 | 2.75 | 1.79 | 0.93 | 2.64 |

| Eotaxin.3 | 105/105 | 0.11 | .27419 | 0.28516 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| FGF.basic | 101/105 | 0.32 | .00124 | 0.00402 | 1.02 | 0.54 | 1.50 | 0.92 | 0.43 | 1.41 |

| G-CSF | 101/105 | 0.37 | .00013 | 0.00139 | 5.09 | 3.32 | 6.87 | 4.71 | 2.87 | 6.54 |

| GM-CSF | 104/105 | 0.13 | .19593 | 0.20793 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| I-309 | 105/105 | 0.18 | .06467 | 0.07473 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| INF-α | 104/105 | 0.26 | .00658 | 0.01338 | 0.58 | 0.24 | 0.91 | 0.51 | 0.16 | 0.86 |

| INF-γ | 104/105 | 0.18 | .06165 | 0.07455 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| IL-10 | 104/105 | 0.29 | .00262 | 0.00716 | 1.35 | 0.59 | 2.10 | 1.30 | 0.53 | 2.06 |

| IL-12 | 104/105 | 0.27 | .00539 | 0.01167 | 0.77 | 0.36 | 1.17 | 0.67 | 0.25 | 1.09 |

| IL-13 | 104/105 | 0.22 | .02618 | 0.03680 | 0.34 | 0.10 | 0.57 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.55 |

| IL-15 | 104/105 | 0.26 | .00856 | 0.01525 | 1.53 | 0.57 | 2.50 | 1.40 | 0.41 | 2.39 |

| IL-16 | 105/105 | 0.33 | .00050 | 0.00236 | 5.01 | 3.30 | 6.72 | 4.76 | 3.04 | 6.48 |

| IL-17 | 104/105 | 0.03 | .72713 | 0.74139 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| IL-1β | 104/105 | 0.31 | .00122 | 0.00402 | 2.04 | 1.29 | 2.80 | 1.82 | 1.02 | 2.61 |

| IL-1RA | 104/105 | 0.26 | .00836 | 0.01525 | 1.46 | 0.30 | 2.62 | 1.47 | 0.32 | 2.61 |

| IL-2 | 104/105 | 0.24 | .01502 | 0.02309 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| IL-20 | 105/105 | 0.16 | .11007 | 0.12177 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| IL-21 | 105/105 | 0.25 | .00880 | 0.01525 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.47 |

| IL-23 | 105/105 | 0.24 | .01510 | 0.02309 | 0.36 | 0.06 | 0.65 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.64 |

| IL-28A | 105/105 | 0.25 | .00911 | 0.01528 | 0.39 | 0.08 | 0.71 | 0.41 | 0.10 | 0.72 |

| IL-2R | 104/105 | 0.26 | .00695 | 0.01338 | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.52 |

| IL-33 | 105/105 | 0.26 | .00683 | 0.01338 | 0.53 | 0.19 | 0.87 | 0.50 | 0.16 | 0.85 |

| IL-4 | 104/105 | 0.20 | .03910 | 0.05083 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| IL-.5 | 104/105 | 0.03 | .77379 | 0.77379 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| IL-.6 | 104/105 | 0.37 | .00011 | 0.00139 | 3.94 | 2.44 | 5.44 | 3.64 | 2.09 | 5.19 |

| IL-7 | 104/105 | 0.20 | .04281 | 0.05429 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| IL-8 | 104/105 | 0.34 | .00046 | 0.00236 | 2.54 | 1.07 | 4.02 | 2.36 | 0.85 | 3.87 |

| IL-10 | 104/105 | 0.29 | .00297 | 0.00772 | 2.98 | 1.02 | 4.95 | 2.78 | 0.79 | 4.77 |

| LIF | 105/105 | 0.20 | .04437 | 0.05493 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| MCP-1 | 104/105 | 0.29 | .00319 | 0.00789 | 1.77 | 0.94 | 2.61 | 1.64 | 0.78 | 2.49 |

| MCP-2 | 105/105 | 0.18 | .06318 | 0.07467 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| MCP-4 | 105/105 | 0.21 | .03017 | 0.04129 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.31 |

| MIG | 104/105 | 0.24 | .01242 | 0.02018 | 1.28 | 0.39 | 2.18 | 1.11 | 0.18 | 2.05 |

| MIP-1α | 104/105 | 0.38 | .00008 | 0.00139 | 2.41 | 1.62 | 3.21 | 2.19 | 1.35 | 3.02 |

| MIP-1β | 104/105 | 0.33 | .00063 | 0.00275 | 2.26 | 1.53 | 2.98 | 2.12 | 1.37 | 2.88 |

| MIP.1d | 105/105 | 0.28 | .00348 | 0.00822 | 1.04 | 0.34 | 1.75 | 0.99 | 0.29 | 1.69 |

| RANTES | 104/105 | 0.18 | .07252 | 0.08197 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| SCF | 105/105 | 0.36 | .00018 | 0.00139 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.84 | 0.55 | 0.25 | 0.84 |

| SDF-1a.b | 105/105 | 0.32 | .00093 | 0.00374 | 0.47 | 0.19 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.18 | 0.72 |

| TARC | 105/105 | 0.36 | .00019 | 0.00139 | 0.45 | 0.22 | 0.68 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 0.66 |

| TNF-α | 104/105 | 0.27 | .00478 | 0.01081 | 2.66 | 1.85 | 3.47 | 2.49 | 1.66 | 3.31 |

| TPO | 105/105 | 0.22 | .02473 | 0.03572 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| TRAIL | 105/105 | 0.29 | .00236 | 0.00682 | 2.46 | 0.75 | 4.18 | 2.29 | 0.58 | 4.01 |

| TSLP | 105/105 | 0.24 | .01555 | 0.02310 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.6 |

| VEGF | 101/105 | 0.37 | .00015 | 0.00139 | 1.99 | 1.26 | 2.72 | 1.88 | 1.12 | 2.63 |

| 6Ckine | 105/105 | 0.21 | .03448 | 0.04598 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.60 | 0.29 | 0.002 | 0.59 |

MFI, Median fluorescence intensity.

The local immune mediator MFIs were generalized log–transformed before all statistical analyses.

The unadjusted analyses were conducted by using Spearman correlation. The Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) and their corresponding P values are shown. The P values after control for multiple comparisons with use of the Benjamini and Hochberg method (ie, q values) are also shown. The boldface cells indicate nonsignificant P and q values (ie, ≥0.05).

The adjusted analyses were conducted by using multivariable linear regression. The β coefficients and their corresponding 95% lower and upper CIs are shown. Model 1 included the infant’s age at the time of the RSV ARI, sex, and race and ethnicity as covariates. Model 2 included the infant’s age at the time of the RSV ARI, sex, and maternal asthma as covariates. The β coefficient can be interpreted as the increase in that local immune mediator’s generalized log–transformed MFI per 1% increase in the nasopharyngeal relative abundance of Haemophilus during an RSV ARI after control for the model covariates. Only the estimates for local immune mediators with q values that were less than 0.05 in the unadjusted analyses and remained significant in the adjusted analyses are shown.

Methods

Overview of infant susceptibility to pulmonary infections and asthma following RSV exposure study

The INSPIRE cohort is a large (N = 1949) population-based birth cohort of previously healthy, term infants born between June and December that was designed so that the first ARI due to RSV in infancy could be captured.E1 Eligible infants were enrolled mainly during a well-child visit at a participating general pediatric practice throughout the middle Tennessee region. The catchment zone encompassed urban, suburban, and rural areas.

To capture all RSV ARIs of infants enrolled in the INSPIRE study (including the first RSV ARI, which is usually the most severeE2), we conducted intensive passive and active surveillance during each infant’s first RSV season (November to March in our regionE3, E4) by (1) performing biweekly telephone, e-mail, and/or in-person follow-up; (2) frequently educating parents and reminding them to call us at the onset of any acute respiratory symptom; and (3) approaching all infants who were seen at 1 of the participating pediatric practices for an unscheduled visit. An ARI was defined as parental report of (1) at least 1 of the major symptoms or diagnoses (wheezing, difficulty in breathing, and presence of a positive RSV test) or (2) any 2 of the minor symptoms or diagnoses (fever, runny nose/congestion/snotty nose, cough, ear infection, and hoarse cry). If an infant met these prespecified criteria, we then conducted an in-person respiratory illness visit that included the collection of a nasal wash. The nasal wash was collected by gently flushing 5 mL of sterile saline solution into 1 of the infant’s nares. After sampling, the nasal washes were aliquoted and snap-frozen at –80°C until further processing. Data were collected and managed by using the Research Electronic Data Capture tool hosted at Vanderbilt University.E5 One parent of each infant provided informed consent for participation. The institutional review board of Vanderbilt University approved this study. The detailed methods for the INSPIRE study have been reported previously.E1

Overview of the study population

For our study, on the basis of our hypothesis of interest, we included only infants enrolled in the INSPIRE study who had at least 1 RSV ARI during their first RSV season. Because we have previously shown that specific respiratory viruses can be associated with distinct nasopharyngeal bacterial signatures,E6 we further limited eligibility to infants with RSV-only ARIs (ie, no coinfections). Of the 309 infants with RSV-only ARIs who were enrolled in the INSPIRE study, 105 (∼34%) had at least 1 nasal wash with available 16S rRNA sequencing and immune mediator data (obtained as part of separate studiesE6, E7, E8, E9) and were thus included in our study. For infants with data from at least 1 RSV ARI, only data available from the earliest RSV ARI were included in the statistical analyses.

Detection of RSV and viral load assessment

The detection of RSV in nasal washes was performed by real-time RT-PCR. For this, TaqMan low-density array cards using virus-specific primers and probes were run on the Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR platform using the AgPath-ID One-Step RT-PCR Kit (Applied Biosystems) as previously described.E10, E11 The cycle threshold values were used for the assessment of viral load (where a lower cycle threshold value indicates a higher viral load).

Characterization of the nasopharyngeal abundance of Haemophilus

We extracted bacterial DNA from 100 to 200 μL of nasal wash solution by using the Qiagen PowerSoil Kit. Construction of libraries was performed as previously described.E6, E7, E8, E12 Amplicons targeting the V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA were generated by combining 7 μL of template, 12.5 μL of MyTaq HS Mix (Bioline), 0.75 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma), 1 μL of PCR-Certified Water (Teknova), and 2 μL of each 10 μM primer before each round of PCR. During the first round of PCR, the target region was amplified with the primers 515F (5'-GTGCCAGCHGCYGCGGT-3') and 806R (5'-GGACTACNNGGGTWTCTAAT-3'), with an initial denaturing step at 95°C for 3 minutes. This was followed by 10 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 50°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 second and a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. During the second round of PCR, 20 cycles with the same cycling conditions as before were performed to add Illumina adaptors, standard Illumina sequence primer region, a 12-bp barcode, and random nucleotides to increase sequence diversity.

Each amplified sample was run on a 1.2% agarose gel to confirm reaction success. Amplicons were cleaned and normalized with the SequalPrep Normalization Kit (ThermoFisher). Normalized amplicons were pooled and cleaned with 1X AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter). The pool was run on a 1.5% agarose gel, and the target size band was extracted and cleaned with the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Cleanup Kit (Macherey-Nagel). The pool was then sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform with 2 × 300-bp reads.

A PCR and an extraction negative control and 2 samples with known taxonomic composition (provided by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Biological and Emerging Infections [BEI] programE13) were amplified and sequenced concurrently with the samples. The 2 BEI control reagents obtained through BEI Resources included (1) Genomic DNA from Microbial Mock Community B (Staggered, Low Concentration), v5.2L, for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing, HM- 783D, and (2) Genomic DNA from Microbial Mock Community B (Even, Low Concentration), v5.1L, for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing, HM-782D. After sequencing, only a small fraction of 16S rRNA sequences were found in the negative controls compared with in the infant samples, and the bacterial sequences recovered had little overlap with the infant samples. Both BEI controls returned a taxonomic profile similar to their expected taxon distributions.

We subsequently processed the 16S rRNA sequences by using the dada2 pipeline by following its standard operating procedure (available at: https://benjjneb.github.io/dada2/tutorial.html, last accessed November 21, 2019).E14 To this end, sequences were grouped into ASVs and taxonomy was assigned by using the SILVA reference database.E15 Sequences were subsequently processed through the R software package decontam to remove any suspected contaminants that were found in the negative control samples.E16 Haemophilus genus and ASV abundances were calculated as relative abundances by using simple proportions.

Identification of nasopharyngeal Haemophilus species

To identify the nasopharyngeal Haemophilus species, we used both (1) the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) and (2) available WMS data from a selected number of nasal washes (n = 6).E17

To compare Haemophilus ASVs against a reference database with BLAST, we used the nucleotide sequence database (available at: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome [last accessed November 21, 2019]) and specified the organism as Haemophilus (taxid:724).

For the WMS, we first depleted eukaryotic DNA from the genomic DNA extracted as already described for 16S rRNA gene sequencing using the NEBNext Microbiome Enrichment Kit (New England Biolabs). Next, we constructed dual-indexed sequencing libraries with the Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina). Equimolar amounts of each library were then pooled, and sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq platform with 2 × 150-bp reads. For the initial processing of the WMS data set, we used FastQC to assess the sequence quality.E18 The adapter trimming and removal of low-quality data were performed with Trimmomatic.E19 Following this, we removed human DNA by aligning sequences to the Genome Research Consortium Human Build 38 reference assembly with the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner.E20, E21 Lastly, we assigned taxonomy by using GOTTCHA with the software’s default parameters.E22 For the detection of Haemophilus species, no minimum cutoff for the relative abundance was instituted.

Measurement of nasopharyngeal immune mediator levels

The nasopharyngeal immune mediators were measured by using 2 multiplex magnetic bead–based assays (Milliplex MAP Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel II Premixed 23 Plex Kit [MilliporeSigma] and Cytokine 30-Plex Human Panel [Thermo Fisher Scientific]) as previously described.E9 These panels measure a total of 53 immune mediators (ie, cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors) that have been associated with clinical outcomes in allergy, immunology, and pulmonary research (see Table E1). The assays were all conducted in a Luminex MAGPIX platform using the xMAP technology as per the manufacturer's instructions. Two replicates of each sample assay were performed on 96-well plates. One blank well was used as a negative control and to estimate the background. One immune mediator (ie, hepatocyte growth factor) had a large number of values below the lower detectable limit (∼50%) and was thus excluded from further statistical analyses. The Luminex xMAP data were processed by using the method described by Won et al, which uses median fluorescence intensities of individual beads instead of the usual standard curve-based data-processing method to increase the sensitivity and accuracy of high-throughput immunoassays.E9, E23 The immune mediator median fluorescence intensities were generalized log–transformed before statistical analyses to stabilize the data variance.E9

References

- 1.Ederveen T.H.A., Ferwerda G., Ahout I.M., Vissers M., de Groot R., Boekhorst J., et al. Haemophilus is overrepresented in the nasopharynx of infants hospitalized with RSV infection and associated with increased viral load and enhanced mucosal CXCL8 responses. Microbiome. 2018;6:10. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0395-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mansbach J.M., Hasegawa K., Piedra P.A., Avadhanula V., Petrosino J.F., Sullivan A.F., et al. Haemophilus-dominant nasopharyngeal microbiota is associated with delayed clearance of respiratory syncytial virus in infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis. 2019;219:1804–1808. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Steenhuijsen Piters W.A., Heinonen S., Hasrat R., Bunsow E., Smith B., Suarez-Arrabal M.C., et al. Nasopharyngeal microbiota, host transcriptome, and disease severity in children with respiratory syncytial virus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:1104–1115. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0220OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonawane A.R., Tian L., Chu C.Y., Qiu X., Wang L., Holden-Wiltse J., et al. Microbiome-transcriptome interactions related to severity of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Sci Rep. 2019;9:13824. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50217-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosas-Salazar C., Shilts M.H., Tovchigrechko A., Schobel S., Chappell J.D., Larkin E.K., et al. Nasopharyngeal Lactobacillus is associated with childhood wheezing illnesses following respiratory syncytial virus infection in infancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:1447–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turi K.N., Shankar J., Anderson L.J., Rajan D., Gaston K., Gebretsadik T., et al. Infant viral respiratory infection nasal immune-response patterns and their association with subsequent childhood recurrent wheeze. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1064–1073. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2348OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saravia J., You D., Shrestha B., Jaligama S., Siefker D., Lee G.I., et al. Respiratory syncytial virus disease is mediated by age-variable IL-33. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellinghausen C., Gulraiz F., Heinzmann A.C., Dentener M.A., Savelkoul P.H., Wouters E.F., et al. Exposure to common respiratory bacteria alters the airway epithelial response to subsequent viral infection. Respir Res. 2016;17:68. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0382-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulraiz F., Bellinghausen C., Bruggeman C.A., Stassen F.R. Haemophilus influenzae increases the susceptibility and inflammatory response of airway epithelial cells to viral infections. FASEB J. 2015;29:849–858. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-254359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- Larkin E.K., Gebretsadik T., Moore M.L., Anderson L.J., Dupont W.D., Chappell J.D., et al. Objectives, design and enrollment results from the Infant Susceptibility to Pulmonary Infections and Asthma following RSV Exposure Study (INSPIRE) BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:45. doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0040-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics . In: Red book: 2018 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Kimberlin D.W., Brady M.T., Jackson M.A., Long S.S., editors. American Academy of Pediatrics; Elk Grove, IL: 2018. Respiratory syncytial virus. [Google Scholar]

- Wu P., Dupont W.D., Griffin M.R., Carroll K.N., Mitchel E.F., Gebretsadik T., et al. Evidence of a causal role of winter virus infection during infancy in early childhood asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1123–1129. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-579OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.B., Weinberg G.A., Iwane M.K., Blumkin A.K., Edwards K.M., Staat M.A., et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:588–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Salazar C., Shilts M.H., Tovchigrechko A., Schobel S., Chappell J.D., Larkin E.K., et al. Differences in the nasopharyngeal microbiome during acute respiratory tract infection with human rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus in infancy. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1924–1928. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Salazar C., Shilts M.H., Tovchigrechko A., Chappell J.D., Larkin E.K., Nelson K.E., et al. Nasopharyngeal microbiome in respiratory syncytial virus resembles profile associated with increased childhood asthma risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:1180–1183. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2350LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Salazar C., Shilts M.H., Tovchigrechko A., Schobel S., Chappell J.D., Larkin E.K., et al. Nasopharyngeal Lactobacillus is associated with childhood wheezing illnesses following respiratory syncytial virus infection in infancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:1447–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turi K.N., Shankar J., Anderson L.J., Rajan D., Gaston K., Gebretsadik T., et al. Infant viral respiratory infection nasal immune-response patterns and their association with subsequent childhood recurrent wheeze. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1064–1073. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2348OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodani M., Yang G., Conklin L.M., Travis T.C., Whitney C.G., Anderson L.J., et al. Application of TaqMan low-density arrays for simultaneous detection of multiple respiratory pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2175–2182. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02270-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery S.L., Erdman D.D., Bowen M.D., Newton B.R., Winchell J.M., Meyer R.F., et al. Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay for SARS-associated coronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:311–316. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilts M.H., Rosas-Salazar C., Tovchigrechko A., Larkin E.K., Torralba M., Akopov A., et al. Minimally invasive sampling method identifies differences in taxonomic richness of nasal microbiomes in young infants associated with mode of delivery. Microb Ecol. 2016;71:233–242. doi: 10.1007/s00248-015-0663-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R., Peacock S. BEI Resources: supporting antiviral research. Antiviral Res. 2008;80:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan B.J., McMurdie P.J., Rosen M.J., Han A.W., Johnson A.J., Holmes S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruesse E., Quast C., Knittel K., Fuchs B.M., Ludwig W., Peplies J., et al. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7188–7196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis N.M., Proctor D.M., Holmes S.P., Relman D.A., Callahan B.J. Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data. Microbiome. 2018;6:226. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0605-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis S., Madden T.L. BLAST: at the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W20–W25. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingett S.W. Andrews S. FastQ Screen: a tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Res. 2018;7:1338. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.15931.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E.S., Linton L.M., Birren B., Nusbaum C., Zody M.C., Baldwin J., et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas T.A., Li P.E., Scholz M.B., Chain P.S. Accurate read-based metagenome characterization using a hierarchical suite of unique signatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e69. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won J.H., Goldberger O., Shen-Orr S.S., Davis M.M., Olshen R.A. Significance analysis of xMap cytokine bead arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2848–2853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112599109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]