Abstract

Many health care providers screen high-risk individuals exclusively with an HbA1c despite its insensitivity for detecting dysglycemia. The 2 cases presented describe the inherent caveats of interpreting HbA1c without performing an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). The first case reflects the risk of overdiagnosing type 2 diabetes (T2D) in an older African American male in whom HbA1c levels, although variable, were primarily in the mid-prediabetes range (5.7-6.4% [39-46 mmol/mol]) for many years although the initial OGTT demonstrated borderline impaired fasting glucose with a fasting plasma glucose of 102 mg/dL [5.7 mmol/L]) without evidence for impaired glucose tolerance (2-hour glucose ≥140-199 mg/dl ([7.8-11.1 mmol/L]). Because subsequent HbA1c levels were diagnostic of T2D (6.5%-6.6% [48-49 mmol/mol]), a second OGTT performed was normal. The second case illustrates the risk of underdiagnosing T2D in a male with HIV having normal HbA1c levels over many years who underwent an OGTT when mild prediabetes (HbA1c = 5.7% [39 mmol/mol]) developed that was diagnostic of T2D. To avoid inadvertent mistreatment, it is therefore essential to perform an OGTT, despite its limitations, in high-risk individuals, particularly when glucose or fructosamine and HbA1c values are discordant. Innate differences in the relationship between fructosamine or fasting glucose to HbA1c are demonstrated by the glycation gap or hemoglobin glycation index.

Keywords: prediabetes, OGTT, diabetes, HbA1c, HIV, fructosamine

Two cases are presented describing the discordance between HbA1c and glucose criteria for diagnosing dysglycemia. Because many physicians screen for prediabetes (intermediate hyperglycemia) and diabetes only with an HbA1c determination, these cases illustrate the importance of not relying exclusively on the latter and the vital importance of performing glucose measurements, particularly the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).

Case 1 involves an African American male with HbA1c values in the prediabetes (intermediate hyperglycemia) and diabetes ranges that were discordant with glucose parameters, including the OGTT. The HbA1c was found to overestimate dysglycemia based on normal glucose levels. It is postulated that this patient was predisposed to an elevated HbA1c potentially related to race and aging as both have been associated with increased HbA1c levels.

Case 2 describes a patient with HIV and lipodystrophy having relatively unremarkable HbA1c levels with periodic elevations in serum glucose determinations. Type 2 diabetes (T2D) resulting from HIV-related insulin resistance (IR) and treatment was diagnosed by the OGTT. The discordance between HbA1c and glucose parameters is likely linked to an underestimate of HbA1c that has been associated with the use of reverse nucleoside transcriptase inhibitors.

Case 1

A 66-year-old African American male was referred to the Diabetes Prevention Clinic at the Manhattan VA Medical Center in 2016 with a history of prediabetes (intermediate hyperglycemia) from 2013 to 2016 (HbA1c between 5.7% and 6.4% [39-46 mmol/mol] except for 1 value of 6.6% [49 mmol/mol] in 2013) (Table 1). His medical history was significant for hypertension and hyperlipidemia treated with lisinopril (5 mg) and atorvastatin (40 mg), respectively. There was neither a known family history of diabetes nor personal history of hemoglobinopathy, anemia, chronic kidney disease, or hemolysis. His body mass index (BMI) ranged between 25.5 and 28.0 kg/m2 in that timeframe. As laboratory serum glucose determinations (random and fasting) were discrepant with HbA1c values, a 75-g OGTT was performed in 2016 (Table 2). Except for a slight elevation in the fasting serum glucose level of 102 mg/dL (5.7mmol/L), consistent with mild impaired fasting glucose (IFG), the 1- and 2-hour serum glucose values were normal. Although there are no formal recommendations for the 1-hour postload glucose, published data suggest that values less than 155 mg/dL (8.6 mmol/L) reflect low risk for progression to T2D (1). Although recommendations were made for lifestyle modification, these were not adhered to as he continued to follow an unrestricted diet and engaged in minimal physical exercise (related to lower back degenerative disc disease).

Table 1.

HbA1c, Glucose, Fructosamine, C-peptide Levels, and BMI (Case 1)

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA 1c % (mmol/mol) | 6.6/6.0 (49/42) | 6.2 (44) | 5.9 (41) | 5.7 (39) | 6.5/6.4/6.6 (48/46/49) | 6.6/6.5 (49/48) | 6.4/6.6 (46/49) |

| Serum glucose a mmol/L (mg/dL) | 3.8/6.9 (69/124) | 4.5 (81) | 3.9 (70) | 5.8 (104) | 4.7/7.5/4.9 (86/136/89) | 4.2/5.3 (76/96) | 4.4/5.6 (80/101) |

| Fructosamine (0-285) µmol/L (mmol/L) | 222/217 (0.222/0.217) | 241/227 (0.241/0.227) | 229/214 (0.229/0.214) | ||||

| C-peptide (1.1-5.0 ng/ml) (nmol/L) | 1.5 (0.5) | 6.2 (2.1) | 2.1 (0.7) | 4.6 (1.5) | |||

| BMI (kg/m 2) | 27.5 | 28.0 | 27.3 | 25.4, 26.7 | 27.9, 27.2, 27.5 | 27.3, 26.5 | 27.3, 27.1, 27.7 |

aFasting or random.

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Table 2.

75-gram Oral Glucose Tolerance Test and Indices of β-Cell Function (Case 1)

| 2016 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose 0 min, mg/dL (mmol/L) | 102 (5.7) | 94 (5.2) |

| Glucose 60 min, mg/dL (mmol/L) | 137 (7.6) | 125 (6.9) |

| Glucose 120 min, mg/dL (mmol/L) | 97 (5.4) | 63 (3.5) |

| Insulin 0 min, µIU/mL (pmol/L) | 5 (33) | 6 (42) |

| Insulin 60 min, µIU/mL (pmol/L) | 39 (268) | 81 (563) |

| Insulin 120 min, µIU/mL (pmol/L) | 45 (315) | 7 (45) |

| HOMA-IR | 1.2 | 1.4 |

| Matsuda Index | 6.5 | 6.6 |

| ∆I (0-120) (µU/mL × hr) | 54.2 | 75.35 |

| ∆G (0-120) (mg/dL × hr) | 32.5 | 15.5 |

| ∆I/∆G (0-120) (µU/mL per mg/dL) | 1.67 | 4.86 |

| ∆I/∆G (0-120) ÷ HOMA-IR | 1.41 | 3.49 |

Abbreviations: ΔG (0-120), incremental area under the glucose curve; ΔI (0-120), incremental area under the insulin secretion curve; ∆I/∆G (0-120), Disposition Index (product of insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion, predicts conversion to diabetes); ∆I/∆G (0-120) ÷ HOMA-IR, Disposition Index by severity of IR; HOMA-IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; Matsuda Index: whole body insulin sensitivity.

From 2016 through the present, HbA1c levels increased to the diabetes range (>6.5% [47 mmol/mol]) in association with fluctuating but higher weight, although his BMI did not exceed 28 kg/m2. Laboratory serum glucose levels performed mostly fasting were essentially unremarkable (Table 1). A second OGTT performed in 2018 (Table 2) was normal with absence of IFG previously observed and an elevated insulin level noted at the 1-hour time point; the 2-hour serum glucose level of 63 mg/dL (3.5 mmol/L) was likely related to this. Fructosamine levels remained within the normal range (0-285 µmol/L [0-0.285 mmol/L]) and C-peptide concentrations were measurable (Table 1). Complete blood count and triglyceride levels were essentially unremarkable (not shown). Of note, Table 2 demonstrates that calculated insulin secretion and sensitivity indices (2) improved between 2016 and 2018, explaining the amelioration in glucose tolerance despite the elevation in HbA1c. Efficiency of glucose disposal appears to be related to the rapidity with which the postload glucose concentration declines to the fasting glucose level, which was more apparent in the OGTT performed in 2018 than in 2016. Individuals whose 2-hour glucose levels do not return to the FPG level were found to have a higher risk of developing T2D after 8 years (2). β-cell function was preserved indicated by intact insulin sensitivity (Matsuda Index) in 2016 and 2018 with a normal insulin resistance index (Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance). The increase in insulin release coupled with a decrease in glucose concentrations observed between the 2 OGTTs explain the improved oral disposition index reflecting the product of insulin secretion in relation to insulin sensitivity, as well as when the disposition index is expressed by the severity of IR (3–5). These positive changes in β-cell function may explain the conversion from IFG to normal glucose tolerance between the 2 OGTTs despite the absence of substantial change in body weight or activity level.

A daily ambulatory glucose profile for 2 weeks was obtained with a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) (Freestyle Libre; Abbott) demonstrating a mean ± SD glucose level of 97 ± 22 mg/dL (5.36 ± 1.22 mmol/L) from 21 January through 4 February 2020. Seventy-seven percent of interstitial glucose values were within the target range (80-140 mg/dL [4.4-7.8 mmol/L]), whereas 19% were below and 4% above. Interstitial fluid and reference standard glucose values with factory-calibrated glucose biosensors may differ by approximately 10 to 20 mg/dL (0.55-1.11 mmol/L), which is potentially important particularly when glucose concentrations are in the near-normal range as in prediabetes (6).

CGM-derived indices of glycemic variability (GV), with normal range for African Americans in parentheses, demonstrated a mean amplitude of glycemic excursions (MAGE) = 3.5 (1.3 ± 1.1), mean of daily differences = 1.3 (0.9 ± 1.7]), mean glucose = 97 mg/dL (94 ± 0.02; 5.4 mmol/L [5.2 ± 0.3]), SD = 1.2 (1.9 ± 1.1), low blood glucose index = 3.3 (3.7 ± 2.9), and high blood glucose index = 1.0 (0.5 ± 2.0) (7). The percentage coefficient of variation for glucose proposed as the most appropriate method for calculating mean within day daily measure of GV ([SD of glucose]/(mean glucose) × 100) was 22.2%, well within the normal threshold of <36% (8). These observations confirm that despite occasional glycemic fluctuations suggested by the somewhat elevated MAGE, there was no evidence for either prediabetes or diabetes during a 2-week “real-life” period based on the mean glucose and other parameters. These CGM data are comparable to those in a study of 153 participants without diabetes (HbA1c < 5.7% [39 mmol/mol]) ages 7 to 80 years wearing a Dexcom 6 CGM for up to 10 days (9). Shah et al found that the mean average glucose in this population was 98 to 99 mg/dL (5.4-5.5 mmol/L) for all age groups. In individuals older than age 60 years, the mean average glucose was 104 mg/dL (5.8 mmol/L). The median time with glucose levels between 70 to 140 mg/dL (3.9-7.8 mmol/L) was 96% (interquartile range, 93 to 98), glucose levels >140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) was 2.1%, and with glucose levels <70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) was 1.1%. The majority of participants in this trial were white (93%) and had a mean BMI of 24.4 ± 3.2 (9).

From the information presented, this patient does not have T2D based on glucose criteria, despite the HbA1c measurements, and has a good long-term prognosis in terms of progression to diabetes assuming that β-cell function remains intact with preserved disposition index, and lifestyle changes are sustained in the absence of other clinical changes (5). The risk associated with increased GV as evidenced by the MAGE is difficult to ascertain, particularly in view of the other normal parameters but has been reported as a risk factor for longer hospitalization and increased in mortality even without diabetes (8). Although unproven, it would still be nonetheless important to further reduce glycemic fluctuations to the degree possible, which, in his situation, would require modifying his diet to reduce excessive carbohydrates and increase activity level. There is clearly no risk in so doing and even slight improvement in these lifestyle measures could have a substantial benefit albeit difficult to quantify.

Case 2

A 62-year-old Caucasian male patient was referred to the Diabetes Prevention Clinic at the Manhattan VA Medical Center in 2020 because of discordant plasma glucose and HbA1c levels. His medical history was remarkable for HIV infection treated with antiretrovirals and dyslipidemia (high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high triglycerides, and low high-density lipoprotein) for which he is currently receiving rosuvastatin (20 mg). He has been taking Genvoya (elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide) since 2017 and was previously treated with different antiretrovirals drugs (including zidovudine, indinavir, and ritonavir) since 1989. He is an airplane pilot, physically active (regular exercise at a gym), and his diet rich in carbohydrates. His father had T2D. On physical examination, there was evidence of lipodystrophy with facial (treated dermatologically) and lower extremity lipoatrophy. In the past 9 years, his BMI varied between 23 and 26 kg/m2 (Table 3). During this period, HbA1c levels were within the normal range (4.5-5.6% [26-38 mmol/mol]) and serum glucose levels oscillated mostly between the prediabetes and diabetes ranges (Table 3). More recently, he had a HbA1c of 5.7% (39 mmol/mol), a high normal fructosamine (274 µmol/L), a fasting serum glucose of 125 mg/dL (6.9 mmol/L), and C-peptide in the high end of the normal range (3.7 ng/mL) (Table 3). The OGTT demonstrated a 1-hour serum glucose of 241 mg/dL (13.4 mmol/L) and a 2-hour value of 204 mg/dL (11.3 mmol/L), with elevations in plasma insulin concentrations at 1 and 2 hours, supporting the diagnosis of T2D (Table 4). β-cell function was markedly altered in this patient with increased IR (Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance) also illustrated by the elevated insulin and glucose response, decreased insulin sensitivity (Matsuda Index), and very low disposition indices. After discussing these results, the patient preferred intensifying his lifestyle with greater adherence to diet, further seeing a dietitian, and preferred not being started on metformin pending further evaluation.

Table 3.

HbA1c, Glucose, Fructosamine, C-peptide Levels, and BMI (Case 2)

| 2011 | 2012 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA 1c (%) (mmol/mol) | 5.6 (38) | 4.7 (28) | 4.5 (26) | 5.1 (32) | 5.1 (32) | 5.7 (39) | 5.7 (39) |

| Serum Glucose a mmol/L (mg/dL) | 6.8 (123) | 6.3 (114) | 5.3 (95) | 7.8 (140) | 6.8 (122) | 6.3 (113) | 6.9 (125) |

| Fructosamine (0-285 µmol/L) (mmol/L) | 274 (0.274) | ||||||

| C-peptide (1.1-5.0 ng/mL) (nmol/L) | 3.7 (1.2) | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m 2) | 25.5/26.2 | 24.7 | 24.2/24.9 | 23.8/23.4 | 23.4/23.8 | 23.9 |

aFasting or random.

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Table 4.

75-gram Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (Case 2)

| Glucose 0 min, mg/dL (mmol/L) | 125 (6.9) |

| Glucose 60 min, mg/dL (mmol/L) | 241 (13.4) |

| Glucose 120 min, mg/dL (mmol/L) | 204 (11.3) |

| Insulin 0 min, µIU/mL (pmol/L) | 14 (97) |

| Insulin 60 min, µIU/mL (pmol/L) | 67 (465) |

| Insulin 120 min, µIU/mL (pmol/L) | 79 (549) |

| HOMA-IR | 4.32 |

| Matsuda Index | 1.88 |

| ∆I (0-120) (µU/mL × hr) | 158.5 |

| ∆G (0-120) (mg/dL × hr) | 155.5 |

| ∆I/∆G (0-120) (µU/mL per mg/dL) | 1.02 |

| ∆I/∆G (0-120) ÷ HOMA-IR | 0.24 |

Abbreviations: ΔG (0-120), incremental area under the glucose curve; ΔI (0-120), incremental area under the insulin secretion curve; ∆I/∆G (0-120), Disposition Index (product of insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion, predicts conversion to diabetes); ∆I/∆G (0-120) ÷ HOMA-IR, Disposition Index by severity of IR; HOMA-IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; Matsuda Index: whole body insulin sensitivity.

Discussion

These cases differ with regard to the relationship between HbA1c and glucose levels. Case 1 is illustrative of an inherent or genetic predisposition to higher HbA1c levels that has been recognized for many years. HbA1c has been noted to being 0.4 percentage points lower in the white population than blacks with smaller differences observed in Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians (10). The higher level may also have been related to statin therapy, although the effect is generally small, as well as the observed age-related increase approximating 0.01-unit increase per year (11). In contrast, Case 2 demonstrates the influence of external or iatrogenic factors resulting in an underestimation of HbA1c concentrations likely related to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) treatment for HIV.

These 2 cases are therefore illustrative of the caveats that need to be considered in the use of HbA1c as a screening tool for diagnosing dysglycemia. In addition, they make a compelling argument for the judicious deployment of published recommendations for detecting glucose disorders and the need to individualize interpretation of clinical test results. HbA1c has been endorsed for detecting prediabetes (intermediate hyperglycemia) by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) (12) and by both the ADA and World Health Organization for diagnosing diabetes (12, 13). HbA1c has several advantages, including convenience, decreased day-to-day variability, greater preanalytic stability, and global standardization (14). Because HbA1c is frequently used as an initial screening test (15), the risk of either over- or underestimating the severity of dysglycemia may be substantial with the potential to profoundly impact patient counseling and well-being. Hence, glucose measurements should be performed concomitantly to confirm the reliability of HbA1c results, recognizing the potential for discordance (16, 17). The limitations inherent with HbA1c should therefore be appreciated by health care providers with consideration given to the performance of an OGTT.

The discrepancy between the diagnostic parameters is not uncommon, with little overlap reported between HbA1c and plasma glucose concentrations—different groups of individuals identified by each method (17, 18). HbA1c is neither sensitive nor specific for detecting prediabetes (intermediate hyperglycemia) and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) is specific but not sensitive (18). In addition, the OGTT is required to detect impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and early T2D that may be missed by uniquely measuring the FPG (19). Although accuracy of the FPG may be improved with simultaneous measurement of HbA1c (20), not performing an OGTT can result in significant underdiagnosis of dysglycemia and therefore should be considered the gold standard for screening glucose disorders (21).

Case 1 highlights the discrepancy between HbA1c and glucose data with the potential for overestimating the occurrence of a glycemic disorder resulting in misclassification. An elevated HbA1c, in the absence of hemoglobinopathies, chronic renal disease, or iron deficiency anemia may be due to genetically higher HbA1c levels observed in the African American population (22–24) and/or as a consequence of aging (11, 25, 26) mentioned earlier. It is worthwhile emphasizing the previous point concerning the prescription of a statin. When taken at a high dose over an extended period by individuals with preexisting risk factors for T2D, statins have been associated with elevations in HbA1c but a relatively low risk for T2D. Nonetheless, the benefit for reducing cardiovascular risk far outweighs that of developing T2D (27, 28).

The relationship between HbA1c and glucose criteria is therefore complex. HbA1c was proposed for diagnosing dysglycemia given limitations inherent with the 2-hour OGTT (e.g., requirement for an overnight fast, inconvenience, laboratory-related expenses, intra-individual variability, differences in glucose absorption rates, and poor reproducibility) (29). Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have demonstrated that glucose criteria outperformed HbA1c capturing twice as many individuals progressing to T2D. The prevalence of prediabetes (intermediate hyperglycemia) by measuring HbA1c (5.7%-6.4% [39-46 mmol/mol]) was significantly less than with an OGTT in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2010 (30) and 2011-2014 (31). Similarly, glucose criteria, particularly the 2-hour plasma glucose during the OGTT, have demonstrated greater sensitivity than HbA1c for diagnosing diabetes in several cohorts (17, 30–38), each parameter diagnosing distinctive populations. In a cross-sectional study of 5395 individuals without diabetes in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2005-2010), glucose criteria diagnosed more than twice as many with diabetes than HbA1c (5.7% vs 2.23%) (30). The sensitivity of HbA1c >6.5% (48 mmol/mol) for diagnosing diabetes was only 41% with 99% specificity. Other studies have confirmed these observations (17, 34–36, 38, 39), with differences in HbA1c sensitivities varying by ethnicity (40–43) being higher in Chinese (42), Asian Indian (43), and African populations (44) than in Caucasians.

Another important consideration in assessing discrepancies between HbA1c and glucose or fructosamine relates to the glycation gap and the hemoglobin glycation index that measure the magnitude and direction of the discrepancy of the correlation between HbA1c and fructosamine or glucose. These parameters define differences between glycated hemoglobin and blood glucose data or fructosamine in the case of the glycation gap and between HbA1c and predicted HbA1c from mean blood glucose with the hemoglobin glycation index (45). HbA1c could systematically deviate from glycemia resulting from factors that influence glycation within the red blood cells. The HbA1c could be lower (negative glycation gap or low hemoglobin glycation index) or higher (positive glycation gap or higher hemoglobin glycation index) compared with a calculated HbA1c from a regression equation of HbA1c versus fructosamine or glucose.

To further understand the pitfalls of relying exclusively on HbA1c, it should be recognized that β-cell dysfunction is responsible for the deterioration of glucose tolerance with decreased insulin secretion rather than insulin resistance as a greater factor than HbA1c in the normal or prediabetes range (46). Because HbA1c is insensitive for identifying individuals with early impairment in β-cell function, its isolated use when the HbA1c < 5.7% (39 mmol/mol) may classify high-risk individuals as normal. This is exemplified in a high-risk population of Mexican Americans with normal glucose tolerance and HbA1c < 5.7% (39 mmol/mol) whose β-cell function was comparable to those with normal glucose tolerance and prediabetes (intermediate hyperglycemia) with HbA1c between 5.7% and 6.4% [39-46 mmol/mol]) (4). Notably, individuals with IFG or IGT had a marked decline in β-cell function independent of the HbA1c level. Therefore, an OGTT is preferable for identifying individuals with early β-cell dysfunction who are at increased future risk for T2D.

It is also worthwhile commenting on the OGTT findings between 2016 and 2018 in Case 1. Given the variability between the 2 OGTT determinations, noting particularly the lower 2-hour glucose value in 2018, it would have been reasonable to further repeat the OGTT to validate the accuracy of these findings. The intra-individual variation in glucose values when the OGTT is repeated within 2 to 6 weeks has been found to approximate 6% for the fasting and 17% for the 2-hour measurements (47, 48). Of interest, the coefficient of variability for HbA1c approximates 4% (48). Therefore, the OGTT should be repeated when the results are marginal and a clear diagnosis cannot be established which may have significant implications for the individual. Repeating the OGTT should also be considered if there is uncertainty regarding adequate preparation (e.g., consumption of 150 g of carbohydrate 3 days preceding the test) or performance of the OGTT such as correct administration of the glucose solution, inadequate handling of glucose specimens as delayed processing or use of incorrect collection tubes without fluoride can result in artificially lower glucose levels.

Case 2 highlights the discordance between glucose criteria and HbA1c possibly related to an underestimate of the latter with the use of NRTIs for the treatment of HIV (49–53). Given the inaccuracy of HbA1c, it has been recommended that it therefore not be used for assessing glycemia (49) in HIV-infected patients, particularly those on NRTI-based therapy, with fructosamine as an appropriate alternative (52). In context of a low HbA1c level of 5.7% (38.8 mmol/mol) in the case presented, the high normal fructosamine associated with mild T2D diagnosed by the OGTT is consistent with this recommendation. This approach is further supported by findings that the OGTT was found to be more sensitive and preferable to HbA1c in the HIV population for diagnosing earlier disturbances in glucose homeostasis and thereby preventing complications from diabetes (54).

T2D in this patient is likely related to the underlying condition and its treatment. Individuals with HIV are more likely to have T2D with the prevalence estimated between 2% and 14% (50, 51). It is not certain whether HIV per se causes T2D, although infection is associated with metabolic dysfunction and impaired glucose metabolism. Increased risk for T2D in this population may be related to coinfection with HCV (leading to hepatic steatosis and fibrosis), medications (atypical antipsychotics, steroids, opiates), and low testosterone levels aside from traditional risk factors such as obesity and age (50, 55). Antiretroviral therapy (ART) may also increase the risk of T2D, although Genvoya (elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, tenofovir alafenamide), which the patient has been taking since approximately 2017, has a more favorable metabolic impact, making it less likely an etiological factor for T2D. He had previous chronic exposure since 1989 to ART medications including formulations associated with T2D (zidovudine, indinavir, ritonavir) (50, 54). Furthermore, the patient has a history of dyslipidemia for many years with low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, lipodystrophy with facial and lower extremity lipoatrophy, insulin resistance, and therefore likely increased systemic inflammation associated with ART therapy (50). Risk factors for lipoatrophy include low CD4 lymphocyte cell count, advanced HIV disease, male sex, and older age when ART is initiated (50). The most important factor is cumulative exposure to previously prescribed thymidine analog NRTIs (zidovudine), leading to adipocyte apoptosis (50, 56).

To summarize, Case 1 illustrates that HbA1c levels exceeding thresholds for prediabetes (intermediate hyperglycemia) (≥5.7% [39 mmol/mol]) or diabetes (≥6.5% [48 mmol/mol]) may not unequivocally establish the diagnosis requiring confirmation with glucose parameters, specifically the OGTT. Furthermore, as seen in Case 2, the diagnosis of glycemic disorders cannot be a priori precluded if HbA1c fall below these threshold values in the absence of glucose data. It is important to consider that although there are plausible specific explanations for the discrepant HbA1c and OGTT results in these 2 cases, as noted earlier, discordance can commonly be observed without an identifiable etiology in other patients attributable to the minimal overlap between these parameters which identify different groups (18). The poor agreement between HbA1c and OGTT and low sensitivity and specificity of HbA1c for classifying prediabetes and T2D has also been described in a multiethnic cohort of obese children and adolescents regardless of age or sex (57). Hence, the authors conclude that the use of HbA1c in isolation is a poor diagnostic tool and can result in overlooking or delaying recognition of prediabetes or T2D (57). The 2-hour OGTT also provides valuable information with regard to β-cell function in obese youth (58). With the isolated use of HbA1c many individuals may therefore risk being undiagnosed (i.e., high false-negative rate) and untreated despite having increased risk of microvascular complications based on glucose criteria.

In conclusion, screening can be inaccurate without the careful scrutiny of both glucose and HbA1c data. Given the insensitivity of the HbA1c for detecting glucose disorders and discordance with glucose parameters, an OGTT would therefore be appropriate for screening high-risk individuals. Populations at particular risk in whom an OGTT should be considered include those whereby nonglycemic factors may affect the accuracy of HbA1c measurements as well as individuals with discordant fructosamine or mean blood glucose levels compared with HbA1c, suggesting a variation in glycation gap or hemoglobin glycation index, respectively.

Furthermore, as observed earlier, because many individuals may have IGT (or T2D) in the absence of IFG, an OGTT would be worthwhile considering given the increased risk for progression to T2D and CVD. The frequency with which these conditions exist augurs the need for a substantial number of individuals to undergo an OGTT.

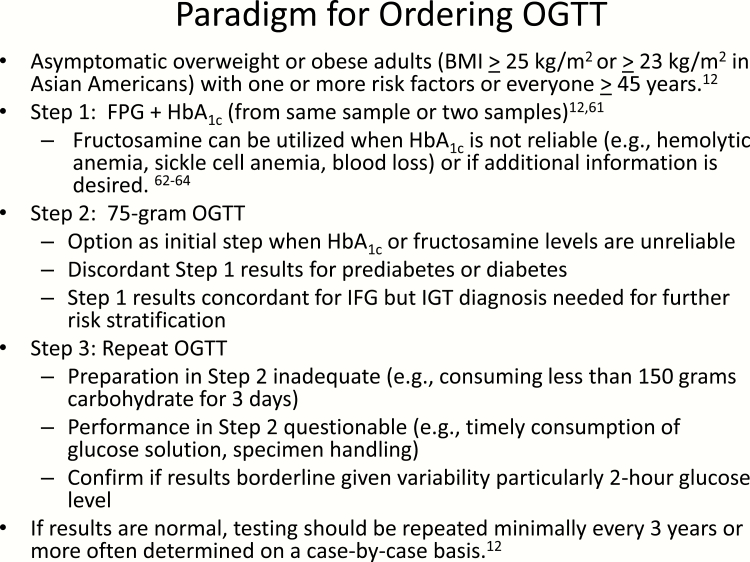

A proposed paradigm regarding ordering an OGTT is depicted in Fig. 1. Because ADA Standards of Care (12) recommends 2 abnormal tests results from the same sample or 2 separate samples, an approach validated by Selvin et al in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (59), abnormalities in both simultaneously measured FPG and HbA1c levels would confirm the diagnosis of dysglycemia. If the HbA1c is not reliable, fructosamine could be used as a complementary or adjunctive measurement (60–62) because it has been shown to be strongly associated with incident diabetes, microvascular complications with prognostic value comparable to HbA1c (61). Because fructosamine is a measure of glycated serum protein (principally albumin), it can be affected by alterations in the rates of production or disappearance of albumin and other serum proteins (e.g., nephrotic syndrome and advanced liver disease) (62). Furthermore, as discussed earlier, discordance between HbA1c and fructosamine is evidence for a glycation gap, the measurement of which is not currently accessible in clinical practice (62).

Figure 1.

Paradigm for ordering an oral glucose tolerance test.

Despite limitations of indirect measures of glycemia, the commentary by Cohen and Herman remains timely, encouraging clinicians not to be deterred from using “multiple sources of information to assess glycemia and maintain a high index of suspicion when an indirect measure does not seem correct” (62). The OGTT would be indicated in the eventuality of discordant results between HbA1c and FPG or fructosamine, when HbA1c or fructosamine measurements are not reliable, or for diagnosing IGT, which would be beneficial for further risk stratification. It is recommended that the OGTT be repeated if the initial test results are discrepant or if there is uncertainty regarding its preparation or performance. Testing should be repeated at a minimum every 3 years but more often determined on a case-by-case basis (12).

Because the 2-hour OGTT has distinct disadvantages, the widely studied 1-hour OGTT has been shown to have greater sensitivity and specificity than the FPG, 2-hour plasma glucose or HbA1c and therefore may be more practical should this approach be recommended in clinical practice (1, 29, 63–65). In the absence of performing an OGTT, many individuals will receive an incorrect diagnosis and be referred for unnecessary interventions while others will be falsely reassured and not offered an intervention (18). The consequences of this needs to be carefully weighed by the practicing endocrinology community as well as primary care physicians who are more apt to see undiagnosed high-risk individuals.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: M.A.-G. is a recipient of NIH R01 2R01DK097554-06. R.D. is a recipient of NIH RO1 DK24092 and NIH—R01 DK107680-01A1.

Author Contributions: M.B. was the originator, wrote, and is the guarantor of the manuscript. M.A.-G. and B.D. provided analyses and critical review of the manuscript. J.S.N. and M. Buysschaert contributed to the writing and provided critical review of the manuscript. M.P.M and J.L.M. provided critical review of the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- BMI

body mass index

- CGM

continuous glucose monitor

- FPG

fasting plasma glucose

- GV

glycemic variability

- IFG

impaired fasting glucose

- IGT

impaired glucose tolerance

- IR

insulin resistance

- MAGE

mean amplitude of glycemic excursion

- NRTI

nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Bergman M, Manco M, Sesti G, et al. Petition to replace current OGTT criteria for diagnosing prediabetes with the 1-hour post-load plasma glucose ≥155 mg/dl (8.6 mmol/L). Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;146:18-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abdul-Ghani MA, Williams K, DeFronzo R, Stern M. Risk of progression to type 2 diabetes based on relationship between postload plasma glucose and fasting plasma glucose. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1613-1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Defronzo RA. Banting Lecture. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: a new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2009;58(4):773-795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kanat M, Winnier D, Norton L, et al. The relationship between {beta}-cell function and glycated hemoglobin: results from the veterans administration genetic epidemiology study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(4):1006-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Utzschneider KM, Prigeon RL, Faulenbach MV, et al. Oral disposition index predicts the development of future diabetes above and beyond fasting and 2-h glucose levels. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(2):335-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Monnier L, Colette C, Owens D. Calibration free continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices: weighing up the benefits and limitations. Diabetes Metab. 2020;46(2):79-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hill NR, Oliver NS, Choudhary P, Levy JC, Hindmarsh P, Matthews DR. Normal reference range for mean tissue glucose and glycemic variability derived from continuous glucose monitoring for subjects without diabetes in different ethnic groups. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(9):921-928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ceriello A, Monnier L, Owens D. Glycaemic variability in diabetes: clinical and therapeutic implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(3):221-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shah VN, DuBose SN, Li Z, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring profiles in healthy nondiabetic participants: a multicenter prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(10):4356-4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen RM. A1C: does one size fit all? Diabetes Care. 2007;30(10):2756-2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pani LN, Korenda L, Meigs JB, et al. Effect of aging on A1C levels in individuals without diabetes: evidence from the Framingham Offspring Study and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2004. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(10):1991-1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S14-S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Use of Glycated Haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus. http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/report-hba1c_2011 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen RM, Haggerty S, Herman WH. HbA1c for the diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes: is it time for a mid-course correction? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(12):5203-5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evron JM, Herman WH, McEwen LN. Changes in screening practices for prediabetes and diabetes since the recommendation for hemoglobin A1c testing. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(4):576-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li J, Ma H, Na L, et al. Increased hemoglobin A1c threshold for prediabetes remarkably improving the agreement between A1c and oral glucose tolerance test criteria in obese population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(5):1997-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lipska KJ, De Rekeneire N, Van Ness PH, et al. Identifying dysglycemic states in older adults: implications of the emerging use of hemoglobin A1c. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(12):5289-5295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barry E, Roberts S, Oke J, Vijayaraghavan S, Normansell R, Greenhalgh T. Efficacy and effectiveness of screen and treat policies in prevention of type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of screening tests and interventions. BMJ. 2017;356:i6538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Færch K, Witte DR, Tabák AG, et al. Trajectories of cardiometabolic risk factors before diagnosis of three subtypes of type 2 diabetes: a post-hoc analysis of the longitudinal Whitehall II cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1(1):43-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hu Y, Liu W, Chen Y, et al. Combined use of fasting plasma glucose and glycated hemoglobin A1c in the screening of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance. Acta Diabetol. 2010;47(3):231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Meijnikman AS, De Block CEM, Dirinck E, et al. Not performing an OGTT results in significant underdiagnosis of (pre)diabetes in a high risk adult Caucasian population. Int J Obes (Lond). 2017;41(11):1615-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Herman WH, Ma Y, Uwaifo G, et al. ; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Differences in A1C by race and ethnicity among patients with impaired glucose tolerance in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(10):2453-2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cavagnolli G, Pimentel AL, Freitas PA, Gross JL, Camargo JL. Effect of ethnicity on HbA1c levels in individuals without diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One. 2017;12(2):e0171315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meigs JB, Grant RW, Piccolo R, et al. Association of African genetic ancestry with fasting glucose and HbA1c levels in non-diabetic individuals: the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Prediabetes Study. Diabetologia. 2014;57(9):1850-1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suvarna H I S, Moodithaya S, Sharma R. Metabolic and cardiovascular ageing indices in relation to glycated haemoglobin in healthy and diabetic subjects. Curr Aging Sci. 2017;10(3):201-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dubowitz N, Xue W, Long Q, et al. Aging is associated with increased HbA1c levels, independently of glucose levels and insulin resistance, and also with decreased HbA1c diagnostic specificity. Diabet Med. 2014;31(8):927-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yandrapalli S, Malik A, Guber K, et al. Statins and the potential for higher diabetes mellitus risk. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2019;12(9):825-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sattar NA, Ginsberg H, Ray K, et al. The use of statins in people at risk of developing diabetes mellitus: evidence and guidance for clinical practice. Atheroscler Suppl. 2014;15(1):1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bartoli E, Fra GP, Carnevale Schianca GP. The oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) revisited. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(1):8-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guo F, Moellering DR, Garvey WT. Use of HbA1c for diagnoses of diabetes and prediabetes: comparison with diagnoses based on fasting and 2-hr glucose values and effects of gender, race, and age. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2014;12(5):258-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Menke A, Casagrande S, Cowie CC. Contributions of A1c, fasting plasma glucose, and 2-hour plasma glucose to prediabetes prevalence: NHANES 2011–2014. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28:681-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Olson DE, Rhee MK, Herrick K, Ziemer DC, Twombly JG, Phillips LS. Screening for diabetes and pre-diabetes with proposed A1C-based diagnostic criteria. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(10):2184-2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang H, Shara NM, Lee ET, et al. Hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, and cardiovascular risk in a population with high prevalence of diabetes: the strong heart study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):1952-1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bennett CM, Guo M, Dharmage SC. HbA(1c) as a screening tool for detection of Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2007;24(4):333-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bhowmik B, Diep LM, Munir SB, et al. HbA(1c) as a diagnostic tool for diabetes and pre-diabetes: the Bangladesh experience. Diabet Med. 2013;30:e70-e77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nair M, Prabhakaran D, Narayan KM, et al. HbA(1c) values for defining diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in Asian Indians. Prim Care Diabetes. 2011;5(2):95-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1577-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Effects of diabetes definition on global surveillance of diabetes prevalence and diagnosis: a pooled analysis of 96 population-based studies with 331 288 participants. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(8):624-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhou X, Pang Z, Gao W, et al. Performance of an A1C and fasting capillary blood glucose test for screening newly diagnosed diabetes and pre-diabetes defined by an oral glucose tolerance test in Qingdao, China. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:545-550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Booth RA, Jiang Y, Morrison H, Orpana H, Rogers Van Katwyk S, Lemieux C. Ethnic dependent differences in diagnostic accuracy of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in Canadian adults. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;136:143-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Christensen DL, Witte DR, Kaduka L, et al. Moving to an A1C-based diagnosis of diabetes has a different impact on prevalence in different ethnic groups. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):580-582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xu Y, Zhao W, Wang W, et al. ; 2010 China Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance Group Plasma glucose and hemoglobin A1c for the detection of diabetes in Chinese adults. J Diabetes. 2016;8(3):378-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gujral UP, Prabhakaran D, Pradeepa R, et al. Isolated HbA1c identifies a different subgroup of individuals with type 2 diabetes compared to fasting or post-challenge glucose in Asian Indians: the CARRS and MASALA studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pr. 2019;153:93-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sumner AE, Thoreson CK, O’Connor MY, et al. Detection of abnormal glucose tolerance in Africans is improved by combining A1C with fasting glucose: the Africans in America Study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(2):213-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nayak AU, Singh BM, Dunmore SJ. Potential clinical error arising from use of HbA1c in diabetes: effects of the Glycation gap. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(4):988-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bruhn L, Vistisen D, Vainø CTR, Perreault L, Færch K. Physiological factors contributing to HbA1c in the normal and pre-diabetic range: a cross-sectional analysis. Endocrine. 2020;68(2):306-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mooy JM, Grootenhuis PA, de Vries H, et al. Intra-individual variation of glucose, specific insulin and proinsulin concentrations measured by two oral glucose tolerance tests in a general Caucasian population: the Hoorn Study. Diabetologia. 1996;39(3):298-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Selvin E, Crainiceanu CM, Brancati FL, Coresh J. Short-term variability in measures of glycemia and implications for the classification of diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1545-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Avari P, Devendra S. Human immunodeficiency virus and type 2 diabetes. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2017;9(3):38-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mirza FS, Luthra P, Chirch L. Endocrinological aspects of HIV infection. J Endocrinol Invest. 2018;41(8):881-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Duncan AD, Goff LM, Peters BS. Type 2 diabetes prevalence and its risk factors in HIV: a cross-sectional study. Plos One. 2018;13(3):e0194199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Slama L, Palella FJ Jr, Abraham AG, et al. Inaccuracy of haemoglobin A1c among HIV-infected men: effects of CD4 cell count, antiretroviral therapies and haematological parameters. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(12):3360-3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim PS, Woods C, Georgoff P, et al. A1C underestimates glycemia in HIV infection. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(9):1591-1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Coelho AR, Moreira FA, Santos AC, et al. Diabetes mellitus in HIV-infected patients: fasting glucose, A1c, or oral glucose tolerance test–which method to choose for the diagnosis? BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Monroe AK, Glesby MJ, Brown TT. Diagnosing and managing diabetes in HIV-infected patients: current concepts. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(3):453-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lagathu C, Béréziat V, Gorwood J, et al. Metabolic complications affecting adipose tissue, lipid and glucose metabolism associated with HIV antiretroviral treatment. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2019;18(9):829-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nowicka P, Santoro N, Liu H, et al. Utility of hemoglobin A(1c) for diagnosing prediabetes and diabetes in obese children and adolescents. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(6):1306-1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chen ME, Aguirre RS, Hannon TS. Methods for measuring risk for type 2 diabetes in youth: the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(8):1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Selvin E, Wang D, Matsushita K, Grams ME, Coresh J. Prognostic implications of single-sample confirmatory testing for undiagnosed diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):156-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ribeiro RT, Macedo MP, Raposo JF. HbA1c, fructosamine, and glycated albumin in the detection of dysglycaemic conditions. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2016;12(1):14-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Selvin E, Rawlings AM, Grams M, et al. Fructosamine and glycated albumin for risk stratification and prediction of incident diabetes and microvascular complications: a prospective cohort analysis of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(4):279-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cohen RM, Herman WH. Are glycated serum proteins ready for prime time? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(4):264-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Abdul-Ghani MA, Williams K, DeFronzo RA, Stern M. What is the best predictor of future type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1544-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Alyass A, Almgren P, Akerlund M, et al. Modelling of OGTT curve identifies 1 h plasma glucose level as a strong predictor of incident type 2 diabetes: results from two prospective cohorts. Diabetologia. 2015;58(1):87-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jagannathan R, Sevick MA, Fink D, et al. The 1-hour post-load glucose level is more effective than HbA1c for screening dysglycemia. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53(4):543-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]