Abstract

The segmental organization of the vertebral column is established early in embryogenesis when pairs of somites are rhythmically produced by the presomitic mesoderm (PSM). The tempo of somite formation is controlled by a molecular oscillator known as the segmentation clock1,2. While this oscillator has been well-characterized in model organisms1,2, whether a similar oscillator exists in humans remains unknown. Genetic analysis of patients with severe spine segmentation defects have implicated several human orthologs of cyclic genes associated with the mouse segmentation clock, suggesting that this oscillator might be conserved in humans3. Here we show that in vitro-derived human as well as mouse PSM cells4 recapitulate oscillations of the segmentation clock. Human PSM cells oscillate twice slower than mouse cells (5-hours vs. 2.5 hours), but are similarly regulated by FGF, Wnt, Notch and YAP5. Single cell RNA-sequencing reveals that mouse and human PSM cells in vitro follow a similar developmental trajectory to mouse PSM in vivo. Furthermore, we demonstrate that FGF signaling controls the phase and period of oscillations, expanding the role of this pathway beyond its classical interpretation in “Clock and Wavefront” models. Overall, our work identifying the human segmentation clock represents an important breakthrough for human developmental biology.

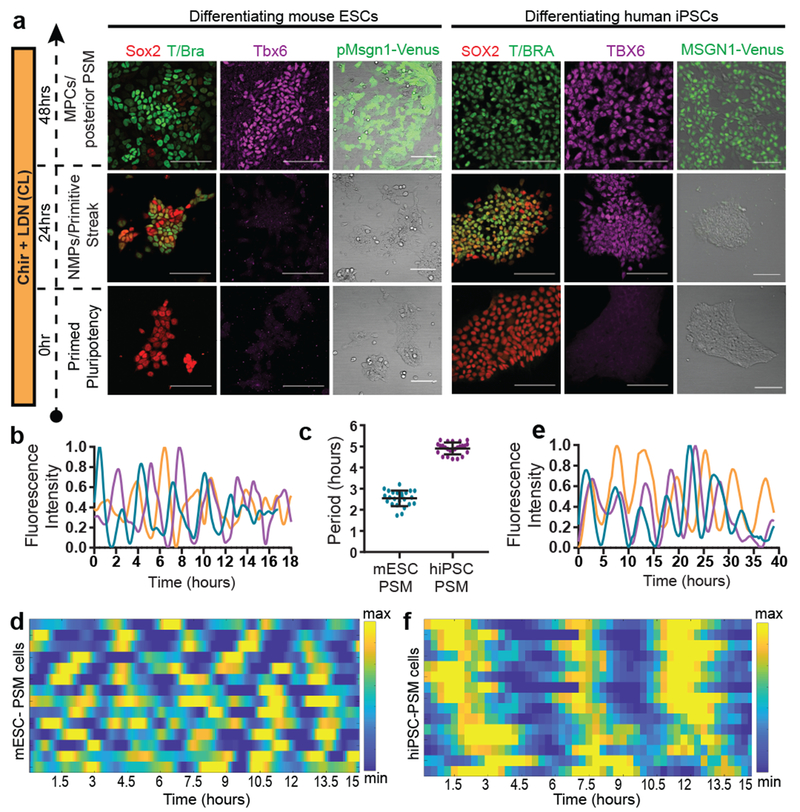

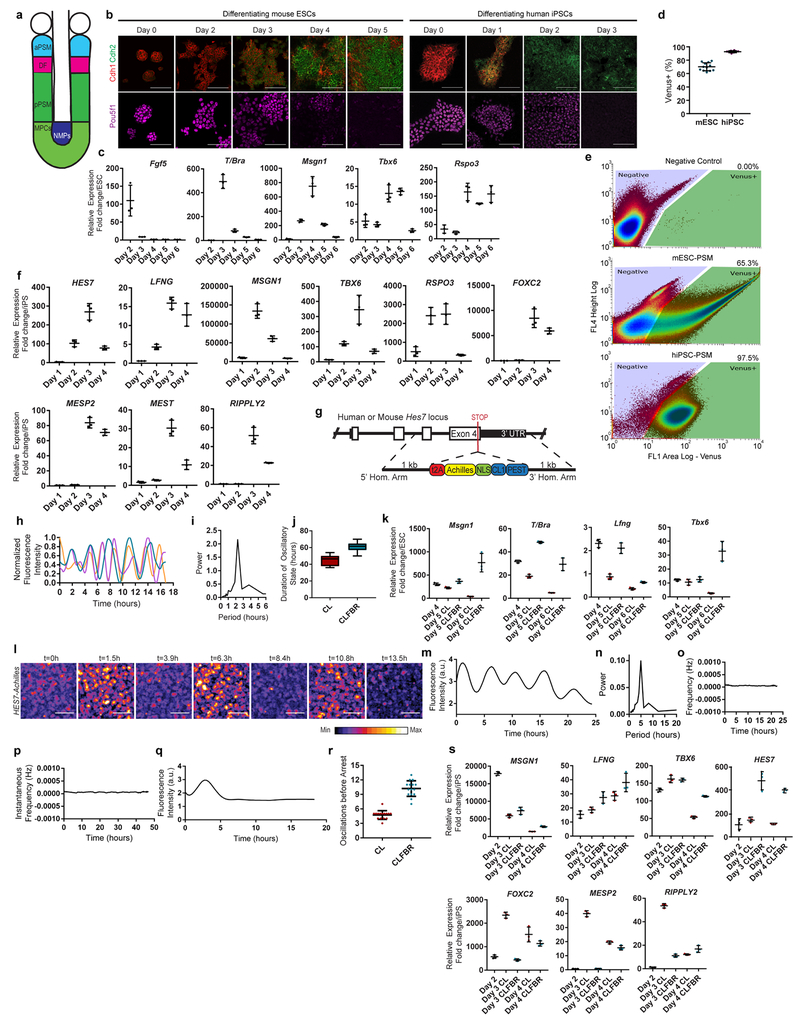

In mouse, early stages of paraxial mesoderm development can be recapitulated in vitro by first inducing an epiblast fate with Activin A/FGF, followed by culture with the Wnt agonist CHIRON99021(Chir) and the BMP inhibitor LDN193189 (LDN) (CL medium)4,6 (Fig. 1a, Extended data Fig. 1a–c). After 24 hours in CL medium, epiblast-like cells acquire a neuromesodermal progenitor (NMPs)7,8/anterior primitive streak (aPS) fate, expressing T/Brachyury, Sox2 and Pou5f1 (Oct4)(Fig 1a, Extended data Fig. 1b–c). By 48 hours, cells activate the PSM markers Tbx6 and Msgn1 (Fig. 1a, Extended data Fig. 1b–e). This transition to PSM is paralleled by an epithelium-to-mesenchyme transition (EMT) marked by a switch from Cdh1 to Cdh2 (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

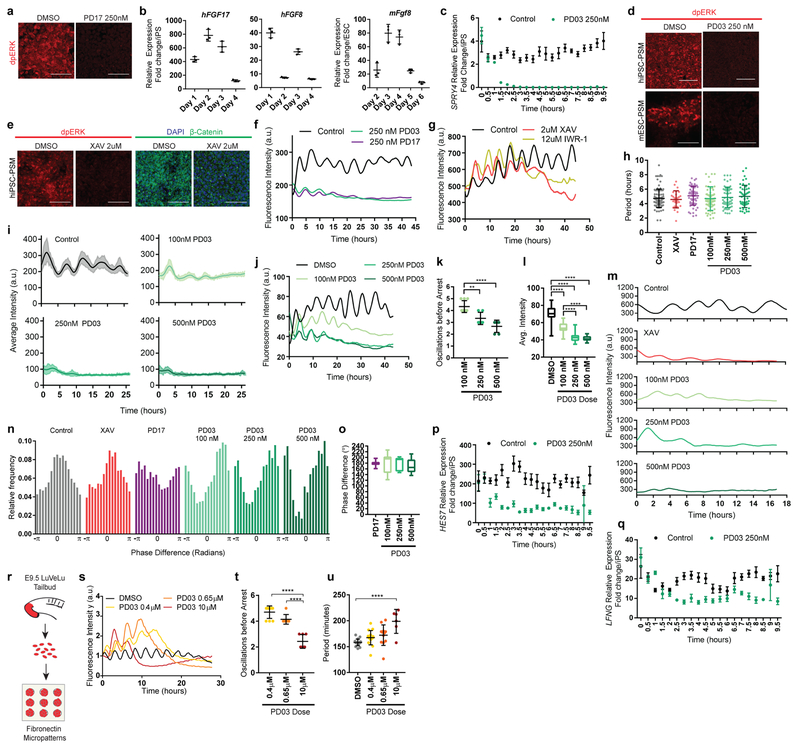

Figure 1. Recapitulation of the mouse and human segmentation clocks in vitro by differentiation of pluripotent stem cells towards PSM fate.

a, Immunofluorescence for stage-specific markers (left) and images of the mESC pMsgn1-Venus/hiPSC MSGN1-Venus reporters (right) in differentiating mouse ESCs and human iPSCs. Scale bar = 100μm. n=7 independent experiments. b, Normalized Hes7-Achilles intensity profiles for three mESC-derived PSM cells imaged in CLFBR medium. n=17 independent experiments c, Period of Hes7-Achilles/HES7-Achilles oscillations in mouse ESC-derived PSM and human iPSC-derived PSM cells cultured in CLFBR medium. Mean ±SD. n=25 d, Heatmap of Hes7-Achilles intensity over time in mESC-derived PSM cells in CLFBR medium. Each row represents one cell. n=15 e, Normalized HES7-Achilles intensity profiles for three human iPSC-derived PSM cells imaged in CLFBR medium. n= 23 independent experiments f, Heatmap of HES7-Achilles intensity over time in human iPSC-derived PSM cells in CLFBR medium. Each row represents one cell. n=15

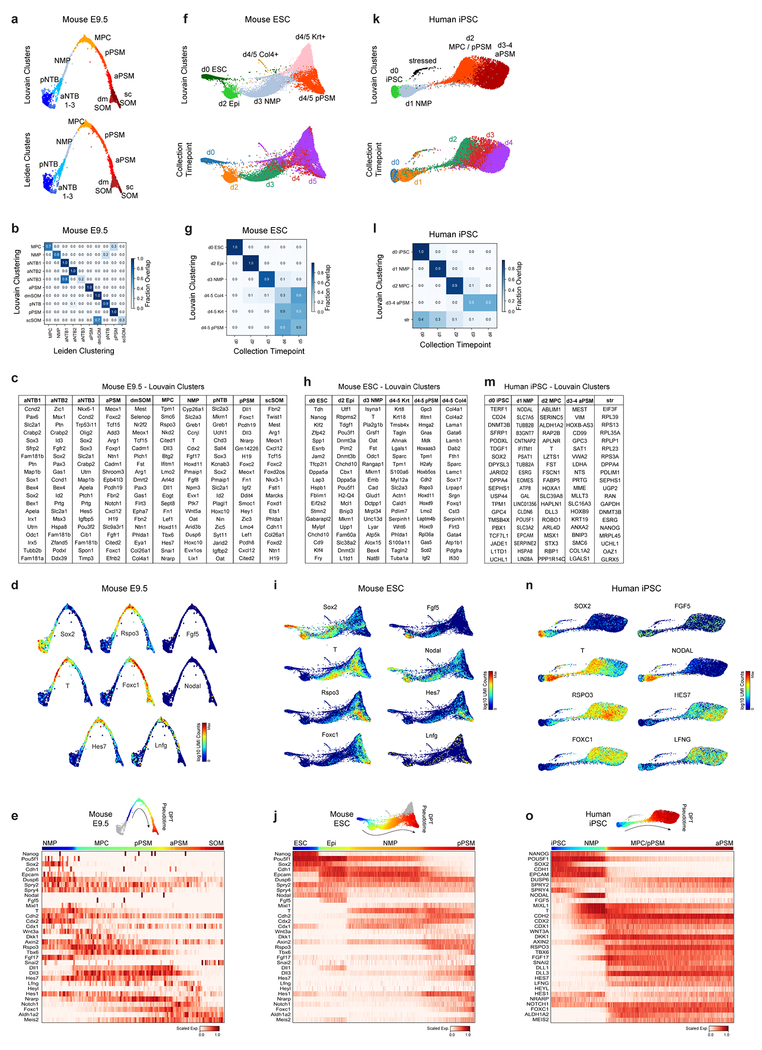

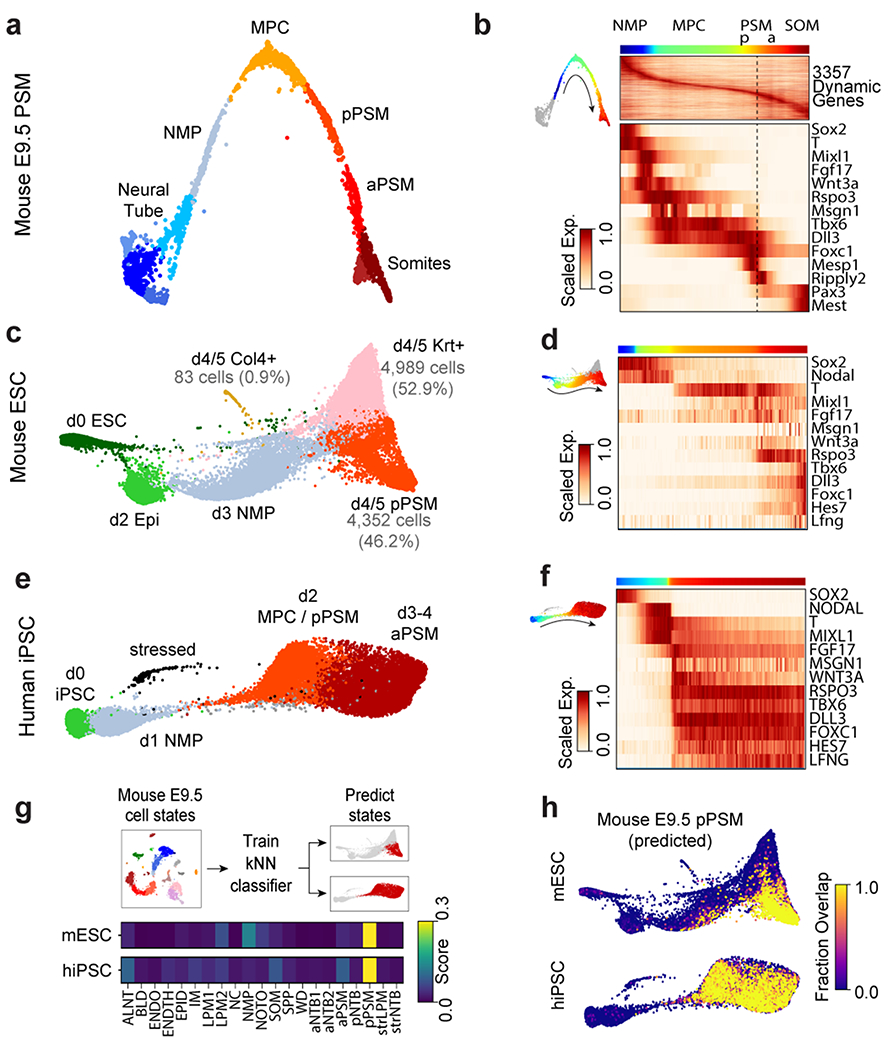

To further characterize the identity of these mouse PSM cells generated in vitro, we benchmarked their transcriptomes against the embryonic mouse PSM. Using single cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq)9, we analyzed 5,646 cells dissociated from the posterior region of two E9.5 mouse embryos. Clustering analysis revealed 21 distinct cell states corresponding to expected derivatives of all three germ layers (Extended Data Fig. 2a–d and Table S1). Transcriptomes of paraxial mesoderm and neural tube cells, which share a common developmental origin7,10, were represented as a k-nearest neighbor (kNN) graph (Fig. 2a). Genes differentially expressed between cell clusters (Extended Data Fig 3a–d) and along a pseudo-temporal trajectory (Fig. 2b and Table S2) stratified distinct phases of paraxial mesoderm differentiation as follows: One cluster, co-expressing Sox2 and T/Brachyury, represented neuromesodermal progenitors (NMPs) and was positioned between the posterior neural tube and paraxial mesoderm clusters, consistent with the known bipotentiality of these cells7. Two clusters expressing T, Rspo3, Tbx6, Dll3, and Foxc1, represented mesodermal precursor cells (MPCs)11and the more mature posterior PSM (pPSM), respectively. These two clusters express Notch pathway genes Hes7, Lfng, Dll1, and Dll3 (Extended Data Fig 3c–e) and likely correspond to the in vivo oscillatory domain. The next cluster corresponds to the anterior PSM (aPSM) marked by Mesp2 and Ripply2 (Fig 2b).

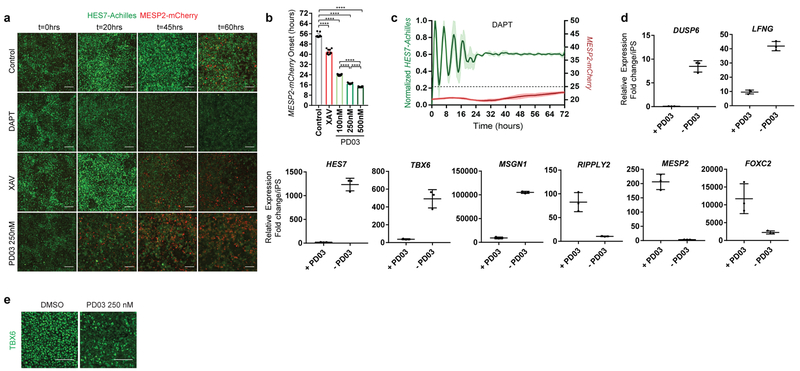

Figure 2. Single cell RNA-sequencing analysis of differentiating mouse and human PSM.

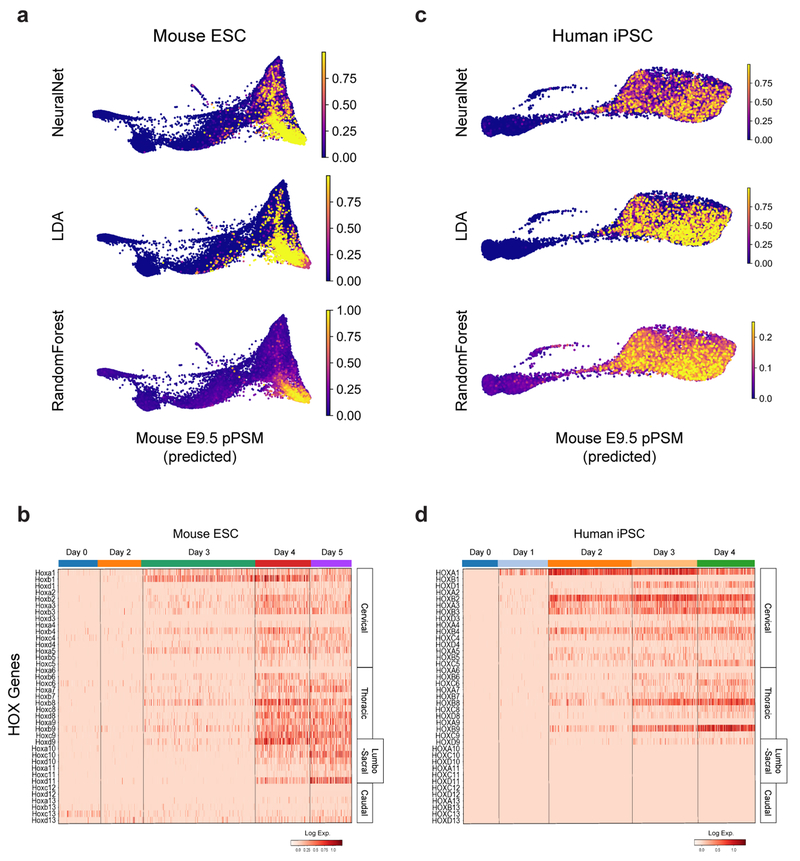

a, Nearest-neighbor (kNN) graph of mouse E9.5 neural tube, PSM, and somite clusters (2,340 cells, 20 PC dimensions), visualized with ForceAtlas2 and colored by Louvain cluster ID. b, Pseudo-temporal ordering of non-neural E9.5 cells. Heatmap illustrates genes with significant dynamic expression ordered by peak expression (see Methods) and selected markers of paraxial mesoderm differentiation. Color bars indicate pseudotemporal position and Louvain cluster assignments. Dotted line marks the determination front (boundary between anterior/posterior PSM). c, Batched-balanced kNN graph of mouse ESC single-cell transcriptomes (21,478 cells), colored by Louvain cluster ID and visualized with ForceAtlas2. Cell numbers for the three terminal day 4/5 states are indicated. d, Pseudo-temporal ordering of mESCs along a path towards the putative d4/5 PSM state. Heatmap shows selected markers of paraxial mesoderm differentiation. e, Batched-balanced kNN graph (ForceAtlas2 layout) of hiPSC single-cell transcriptomes (14,750 cells), colored by Louvain cluster ID. f, Pseudo-temporal ordering of hiPSCs along a path towards the terminal d3/4 PSM state. Heatmap shows selected markers of paraxial mesoderm differentiation. g, Machine-learning classification of human and mouse in vitro cultured cells. A kNN-classifier trained on E9.5 clusters was used to predict identities of terminal in vitro states (inset, red cells). Heatmaps depict fraction of E9.5 assignments for mESC day 4/5 PSM cells and hiPSC (day 2-4 cells). h, Overlay of kNN-classifier scores (fraction of nearest neighbors with the E9.5 ‘pPSM’ label) onto the mESC and hiPSC kNN graphs.

We compared the transcriptomes of these E9.5 in vivo mouse cell states to those of 21,478 mouse ESCs differentiated in vitro. Clustering analyses indicated rapid mESC differentiation over the first three days, with each timepoint largely dominated by a single cluster: naïve ESCs (Day 0), epiblast (Day 2), and NMPs (Day 3), followed by asynchronous transcriptional changes over the final two days (Fig 2c, Extended Data Fig 3f–g). A substantial proportion of the differentiating mESC adopted a similar fate trajectory as the cells in vivo, progressively expressing Sox2, T, Rspo3, Tbx6, Dll3, and Foxc1 (Fig 2d, Extended Data Fig 3h–j). Approximately 46% of differentiating mESCs ultimately adopted a pPSM-like state (Fig 2c, Extended Data Fig 3h). We trained a kNN-classifier on the transcriptional signatures of mouse E9.5 clusters and used it to assign identities to individual d4/5 mESC-derived cells. An E9.5 pPSM-like identity was the most abundantly classified state within cells of the d4/5 mESC ‘pPSM’ cluster (Fig 2g). E9.5-pPSM-classified states were enriched amongst the pPSM branch of d4/5 mESC kNN graph (Fig 2h), and similar enrichments were observed for three classification algorithms (Extended Data Fig 4a). Strikingly, we also detected a collinear trend in Hox genes expression during mESC differentiation (Extended Data Fig 4b). Together, these results suggest broad transcriptional similarity between mESC-derived paraxial mesoderm cells and their in vivo counterparts.

Oscillations of a Hes7-Luciferase reporter in PSM cells differentiated from mouse ESCs in 3D cultures have been recently reported 12. To visualize oscillations of the segmentation clock in 2D, we generated an mESC reporter line where a destabilized version of the YFP variant Achilles was knocked in the 3’ end of the mouse Hes7 gene13 (Extended data Fig. 1g). When differentiated towards PSM, a subset of cells showed oscillatory Hes7-Achilles expression with a period of 2.5 ± 0.4 hours (n=25), similar to the period of the segmentation clock in mouse embryos14,15 (Fig. 1b–d, Extended data Fig. 1h–i, Video S1). This oscillatory state could be extended by adding Fgf4, the RA inhibitor BMS493 and the Rho kinase inhibitor (ROCKi) Y-27362 to CL medium (CLFBR medium) (CL 45 ± 6.6 hours, n=8 vs. CLFBR 61.2 ± 5.7 hours, n=12; Extended data Fig. 1j–k). Therefore, PSM cells differentiated from ESCs in vitro can reliably model the segmentation clock.

We next implemented a similar in vitro strategy to identify the human oscillator. Human iPSCs differentiated in CL medium acquire an NMP/aPS fate characterized by T/BRACHYURY and SOX2 expression after 24 hours (Fig. 1a), and a PSM fate marked by MSGN1 and TBX6 expression after 48 hours (Fig. 1a, Extended data Fig. 1f). A CDH1 to CDH2 switch is observed as in mouse ESCs (Extended data Fig. 1b). The induction efficiency of human cells carrying a MSGN1-Venus knock-in reporter was remarkably high compared to mouse, reaching 92.6 ± 1.5% (n=8) (Extended data Fig. 1d–e, Video S2).

We compared 14,750 differentiating human iPSCs analyzed by scRNA-seq to in vivo and in vitro mouse cell states. Early collection timepoints clustered uniformly and sequentially along the kNN graph, whereas the final two timepoints displayed continuous and overlapping transcriptional features (Extended Data Fig. 3k–l). Differential gene expression and pseudo-temporal ordering analyses revealed shared molecular characteristics between the human clusters and both the in vivo and in vitro mouse PSM lineages (Fig 2e–f, Extended Data Fig. 3m–o). Cells collected after 1 day exhibited characteristics of NMPs/aPS with expression of NODAL, T, MIXL1 and SOX2. Day 2 human cells resembled the mouse MPC and posterior PSM clusters with expression of T, MSGN1, TBX6, DLL3, WNT3A and FGF17, as well as the Notch-associated cyclic genes LFNG and HES7. Day 3/4 cells show expression of markers of anterior PSM such as FOXC1 (Fig. 2f, Extended data Fig 3l). Machine learning classifiers trained on the mouse embryonic cell states consistently assigned an E9.5-pPSM-like identity to the day 2-4 human iPSC clusters (Figure 2g–h, Extended Data Fig. 4c). We detected collinear activation of HOX gene clusters, beginning with HOXA1 and HOXA3 on day 1 and culminating with HOXB9 and HOXC8 on day 4 (Extended Data Fig. 4d). Thus, differentiating human iPSCs to a PSM fate in vitro in CL medium recapitulates a developmental sequence similar to that of the mouse embryo leading to the production of trunk paraxial mesoderm cells.

To assess whether human iPSC-derived PSM cells exhibit segmentation clock oscillations, we generated a HES7-Achilles iPSC reporter cell line (Extended data Fig. 1g). After 48 hours in CL medium, most cells started to show reporter oscillations with a mean period of 4.9 ±0.3 hours (n=25) and constant frequency (Fig. 1c, e–f, Extended data Fig. 1l–p, Videos S3–4). No oscillations could be detected when LDN was omitted, consistent with the need for BMP4 inhibition to induce the paraxial mesoderm fate(Extended data Fig. 1q)16. The total number of oscillations observed could be approximately doubled by culturing in CLFBR medium (CL 4.7 ±0.8 vs. CLFBR 10.2 ±1.6 oscillations, n=15; Extended data Fig. 1r–s). These experiments support the existence of a human segmentation clock ticking with a ~5-hour period.

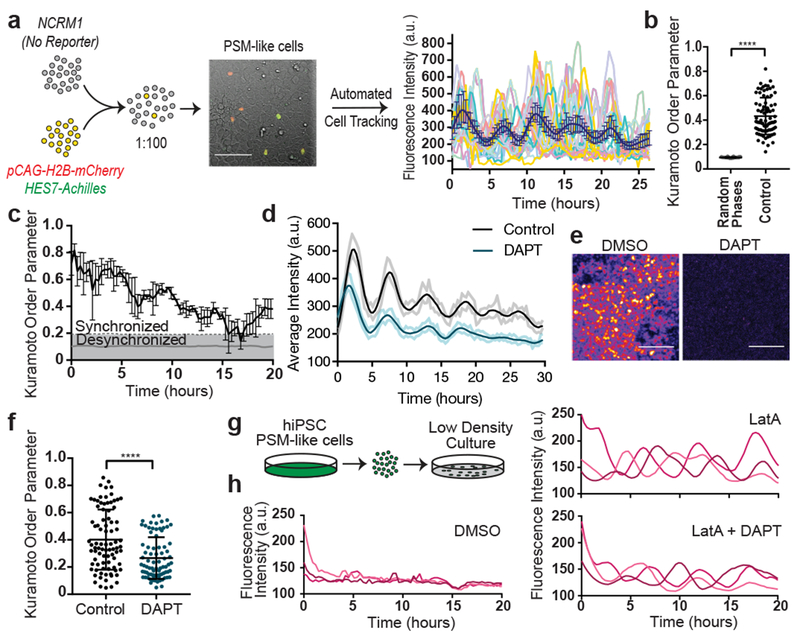

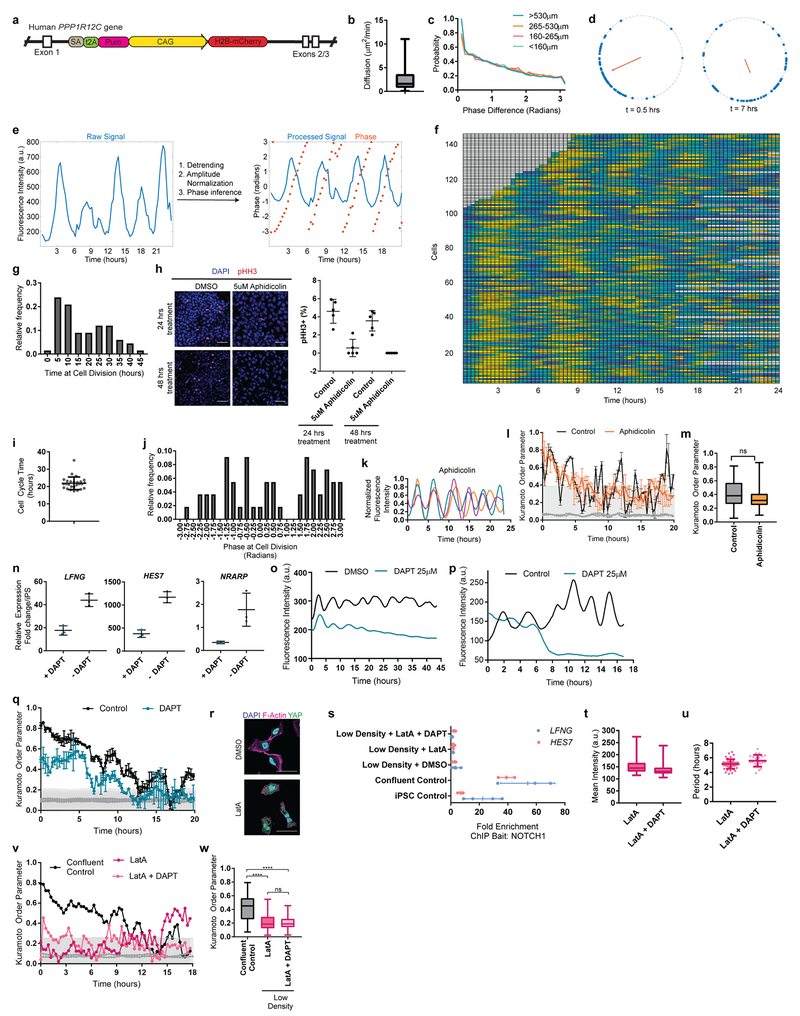

A characteristic property of the segmentation clock oscillations in vivo is their high local synchrony1–2. Synchronization of oscillations appears recapitulated in vitro in human but not mouse PSM cells (Fig. 1d,f). To track individual human iPSC-derived PSM cells, we diluted HES7-Achilles cells expressing a nuclear label (pCAG-H2B-mCherry) in an excess of unlabeled cells (Fig. 3a, Extended data Fig. 5a, Video S5). The average diffusion of cells in vitro (2.4±2.2 μm2/min; Extended data Fig. 5b) was comparable to that of chicken embryo PSM cells in vivo (0.5-8 μm2/min)19. Analysis of the phase of individual oscillators did not reveal any spatial structure, arguing against the existence of traveling waves in these cultures (Extended data Fig. 5c; Video S6). Tracking large numbers of cells allowed us to assess quantitatively the degree of global synchrony using the Kuramoto order parameter17. This analysis confirmed that cells oscillate in synchrony, as the order parameter was significantly higher relative to a model with randomized phases (0.43 ±0.15 vs. 0.094±0.09, p<0.000001, n=139 cells; Fig. 3b–c; Extended data Fig. 5d–f).

Figure 3. Synchronization of individual oscillators within human PSM cultures.

a, Experimental strategy for automated tracking of HES7-Achilles oscillations in individual cells. Scale bar = 100μm b, Kuramoto order parameter for HES7-Achilles cells vs. the same dataset with randomized phases. Mean ±SD. Paired two-sided t-test p=5e−107. n=139 cells. c, Kuramoto order parameter timecourse of HES7-Achilles human PSM cells. Synchronization threshold shown as mean±SD of the Kuramoto order parameter for same dataset, but with randomized phases. n=139 cells d, Average intensity profiles for individual HES7-Achilles human PSM cells treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or 25μM DAPT. Mean ± 95% CI. n=152 cells (Control), 106 cells (DAPT). e, HES7-Achilles fluorescence in human PSM cells following treatment with DMSO or DAPT (25μM). n=9 independent experiments. Scale bar = 100μm f, Kuramoto order parameter for HES7-Achilles cells treated with DMSO or 25μM DAPT. Mean ±SD. Paired two-sided t-test p=2.6e−18. n=131 cells (Control), 110 cells (DAPT). g, Experimental strategy for analysis of oscillations in isolated human PSM cells. h, Representative HES7-Achilles intensity profiles for three isolated human PSM cells in medium containing DMSO, 350nM LatA, or 350nM LatA in combination with 25μM DAPT. n=5 independent experiments.

The Kuramoto order parameter decreased over time, indicating a progressive decay of synchrony (Fig. 3c, Extended data Fig. 5d,f). This prompted us to explore cell division as a potential source of increasing noise over time. Cell division was not temporally coordinated between cells, with roughly 5% of cells in M phase at any given point (Extended data Fig. 5g–h). The cell cycle time was 22 ±3.6 hours (n=26), indicating that division takes place on a different time scale than HES7 oscillations (Extended data Fig. 5i). The ratio between cell division time and clock period is the same as observed in vivo for chicken PSM18,19. Distribution of phases at mitosis was evenly spread, suggesting a lack of correlation between the phase of HES7-Achilles oscillations and cell division (Extended data Fig. 5j). Inhibiting cell division with Aphidicolin (Extended data Fig. 5h), did not affect oscillations or order parameter dynamics (Control 0.404 ±0.2065, n=45 vs. Aphidicolin 0.3465 ±0.1526, n=48, p=0.348; Extended data Fig. 5k–m). Thus, cell division is not a significant source of noise for HES7-Achilles oscillations in human PSM cells in vitro.

Notch signaling has been implicated in maintenance and local synchronization of oscillations5,20–22. Treatment of human and mouse HES7-Achilles cells with the Notch inhibitor DAPT in CLFBR medium led to a dampening of oscillations (Fig. 3d–e; Extended data Fig. 5n–p). Thus, HES7 oscillations require active Notch signaling. The Kuramoto order parameter was lower and decreased more rapidly in DAPT-treated cultures relative to control (Control 0.407 ±0.22, n=131 vs. DAPT 0.266 ±0.153, n=110, p<0.000001; Fig. 3f, Extended data Fig. 5q). We conclude that synchronization of HES7 oscillations in human iPS-derived PSM cultures is Notch-dependent.

We further assessed whether YAP signaling regulates oscillations in human cells as in mouse embryos5. No oscillations were detected when human PSM cells were cultured as isolated cells, (Fig. 3g–h, Video S7). However, treatment with Latrunculin A (LatA), which inhibits YAP signaling23, restored oscillations (Fig. 3h; Extended data Fig. 5r; Video S7). Isolated cells treated with LatA continued to oscillate even with DAPT treatment (Fig. 3h, Video S7). We could not detect significant enrichment of NOTCH1 intracellular domain binding at the HES7 or LFNG promoters in isolated cells by ChIP-qPCR (Extended data Fig. 5s). Isolated cells treated with LatA alone or in combination with DAPT showed the characteristic ~5-hour period observed in confluent cultures, arguing that period is controlled autonomously, independently of Notch cleavage (Extended data Fig. 5u). The Kuramoto order parameter was significantly lower than in confluent controls (control 0.415 ±0.194, n=53 vs. LatA 0.221 ±0.137, n=18 vs. LatA+DAPT 0.1972 ±0.095, n=18), arguing that cell communication is required for maintenance of synchrony (Extended data Fig. 5v–w). Thus, the human segmentation clock, like its mouse counterpart4, can be viewed as an excitable system where Notch provides the stimulus and YAP controls the excitability threshold.

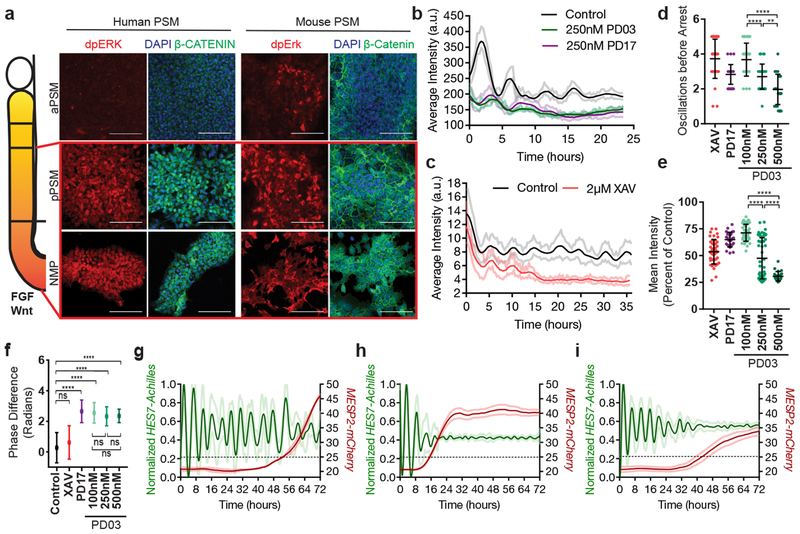

In vivo, PSM cells experience posterior-to-anterior gradients of FGF and Wnt signaling that control their maturation (Fig. 4a). In differentiating mouse and human cultures, staining for dpERK and β-catenin showed that the FGF and Wnt pathways are active at the NMP and pPSM stages but strongly downregulated at later stages in CL medium (Fig. 4a). Treatment with the FGF receptor inhibitor PD173074 (PD17) decreased the dpERK signal (Extended data Fig. 6a), indicating that ERK activation is FGF-dependent and most likely downstream of FGF8 and FGF17, which are expressed by the cells (Extended data Fig. 6b). Thus, differentiating mouse and human cells are exposed to transient Wnt/FGF signaling as in the posterior PSM in vivo (Fig. 4a). The regulation of FGF and Wnt signaling in vitro is largely autonomous.

Figure 4. FGF signaling regulates the dynamic properties of the segmentation clock.

a, Left: Scheme illustrating the posterior-to-anterior gradients of FGF and Wnt signaling along the PSM. Right: Immunofluorescence for doubly phosphorylated ERK, β-catenin and DAPI nuclear stain in differentiating human iPSCs and mouse ESCs. n=8 independent experiments. Scale bar = 100μm. b, Average intensity profiles for individual HES7-Achilles human PSM cells treated with vehicle control (DMSO), 250nM PD03 or 250nM PD17. Mean ± 95% CI. n=89 cells (Control), 30 cells (PD03), 34 cells (PD17) c, Average intensity profiles for individual HES7-Achilles human PSM cells treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or 2μM XAV. Mean ± 95% CI. n=67 cells (Control), 29 cells (XAV). d, Number of HES7-Achilles oscillations before arrest in individual human PSM cells treated with 2μM XAV, 250nM PD17 or 100nM/250nM/500nM PD03. Mean ±SD. One-way ANOVA:100nM vs. 250nM p=2.3e−5, 100nM vs. 500nM p=2.2e−10, 250nM vs. 500nM p=1.5e−3. n=34 e, Mean HES7-Achilles intensity for individual HES7-Achilles human PSM cells treated with 2μM XAV, 250nM PD17 or 100nM/250nM/500nM PD03. Mean ±SD. One-way ANOVA: 100nM vs. 250nM p=1.2e−13, 100nM vs. 500nM p=3e−13, 250nM vs. 500nM p=6.9e−6. n=46 (XAV), n=28 (PD17), n=47 (100nM PD03), n=64 (250nM PD03), n=26 (500nM PD03). f, Summary statistics comparing the instantaneous absolute phase difference relative to control for individual cells treated with vehicle control (DMSO), 2μM XAV, 250nM PD17 or 100nM/250nM/500nM PD03. Mean ±SD. One-way ANOVA: control vs. XAV p= 0.0578, control vs. PD17 p=9.2e-8, control vs. 100nM PD03 p=1.3e-14, control vs. 250nM PD03 p=1.1e−8, control vs. 500nM PD03 p=1.1e−5, 100nM vs. 250nM PD03 p=0.8338, 100nM vs. 500nM PD03 p=0.0601, 250nM vs. 500nM p=0.061. n fixed at 11,000 observations. See Extended data Fig. 6n for full histograms. g-i, HES7-Achilles and MESP2-mCherry intensity profiles in small regions of interest within human PSM cultures. Mean ±SD. Dotted line denotes threshold for MESP2 activation (25 a.u.). g, Vehicle control (DMSO) h, 250nM PD03 i, 2μM XAV. n=15.

We next assessed the effect of prematurely downregulating FGF and Wnt signaling on segmentation clock oscillations in vitro. FGF signaling was inhibited by treating human PSM cells with PD17 or the MEK1/2 inhibitor PD0325901 (PD03), whereas Wnt signaling was blocked using the tankyrase inhibitors XAV939 or IWR-1 (Extended data Fig. 6c–e). Both FGF and Wnt inhibition resulted in dampening and delayed arrest of oscillations without affecting their period (Fig. 4b–c, Extended data Fig. 6f–h). In the case of PD03, higher doses resulted in faster dampening and fewer oscillations before arrest (Fig. 4d–e, Extended data Fig. 6i–l). Mouse Hes7-Achilles cells responded similarly to FGF and Wnt inhibitors (Extended data Fig. 6m). Intriguingly, oscillations in human cells treated with FGF inhibitors but not Wnt inhibitors exhibited a phase-shift relative to control cells, regardless of inhibitor dosage (Fig. 4f, Extended data Fig. 6n–o). We could also detect this phase shift in Notch target gene oscillations upon FGF inhibition by time-lapse qRT-PCR for the HES7 and LFNG genes (Extended data Fig. 6p–q). These data suggest that FGF functions to modulate oscillator properties in addition to controlling PSM maturation.

To further examine the role of FGF signaling on oscillatory properties, we used an ex-vivo system consisting of micropatterned cultures of PSM explants taken from the mouse line LuVeLu (a Lunatic fringe transcriptional reporter)5 (Extended data Fig. 6r). Treating mouse cultures with increasing doses of FGF inhibitors led to a dose-dependent decrease in number of oscillations (Extended data Fig. 6s–t). We observed a progressive increase in period with increasing inhibitor doses, as observed for Lfng oscillations during PSM maturation in vivo14(Extended data Fig. 6u). Our data thus indicate that FGF activity regulates the dynamics (i.e. period, phase and amplitude) of cyclic gene oscillations and does not only control the oscillatory arrest at the wavefront as proposed in classical models1,24.

In vivo, cells at the determination front periodically activate Mesp2 and Ripply2 in a stripe defining the boundaries of the future segment25. By qPCR, we observed that arrest of HES7-Achilles oscillations in human cells coincided with MESP2 and RIPPLY2 expression, which could be delayed by culturing cells in CLFBR medium (Extended data Fig. 1f,s). To image the transition from the oscillatory to the segmental fate, we generated a dual human iPSC reporter line carrying a knock-in MESP2-H2B-mCherry reporter in addition to HES7-Achilles. When cultured in CLFBR medium, a series of approximately 12 oscillations were followed by activation of the MESP2-mCherry signal in an increasing subpopulation of scattered cells (Fig. 4g; Extended data Fig. 7a–b, Video S8). Treatment with the Notch inhibitor DAPT prevented MESP2-mCherry activation, as expected given that Mesp2 is a Notch target in mouse embryos (Extended data Fig. 7c; Video S8). Conversely, oscillatory arrest and MESP2-mCherry onset was prematurely triggered by either FGF or Wnt inhibition (Fig. 4h–I; Extended data Fig. 7a–b, d–e; Video S8). Increasing concentrations of PD03 resulted in faster activation of MESP2 (Extended data Fig. 7b). Therefore, human iPSC-derived PSM cells recapitulate segmental determination, which is dynamically controlled by FGF and Wnt levels.

Our work provides evidence for the existence of a human segmentation clock demonstrating the conservation of this oscillator from fish to human. We identify the human clock period as ~5 hours, indicating that it operates roughly 2 times slower than its mouse counterpart14. This is consistent with the known difference in developmental timing between mouse and human embryos 26. Our culture conditions wherein cells are treated with only two chemical compounds in defined medium allow the production of an unlimited supply of human PSM-like cells. This therefore represents an ideal system to dissect the dynamical properties of the oscillator and its dysregulation in pathological segmentation defects such as congenital scoliosis.

METHODS

Generation of reporter lines

The CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome editing27 was used to generate three reporter lines in human iPSCS (HES7-Achilles, HES7-Achilles; pCAG-H2B-mCherry, and HES7-Achilles; MESP2-mCherry) and one mouse ESC reporter line (Hes7-Achilles). To target the HES7 locus in human NCRM1 iPS cells, a single guide RNA (Extended data Table 1) targeting the 3’ end of HES7 was designed using the MIT Crispr Design Tool (www.crispr.mit.edu) and cloned into the pGuide-it-tdTomato vector (Takara cat. no. 632604). We also generated a repair vector consisting of 1kb 3’ and 5’ homology arms flanking a self-cleaving T2A peptide sequence, followed by the fast-folding YFP variant Achilles16, two destabilization domains (CL1 and PEST), and a nuclear localization signal (T2A-Achilles-NLS-CL1-PEST) in a pUC19 vector backbone by means of Gibson assembly (NEB). The assembled repair vector was then mutated by site directed mutagenesis to eliminate the PAM site (specific mutation noted in Extended data Table 1) in using the In-Fusion cloning kit (Takara). Both the pGuide-it-tdTomato and targeting vectors were delivered to iPS cells by nucleofection using a NEPA 21 electroporator. 24 hours after nucleofection, cells were sorted by TdTomato expression using an S3 cell sorter (Biorad) and seeded at low density in Matrigel-coated plates (Corning, cat. no. 35277) in mTeSR1 (Stemcell Technologies cat. no. 05851) + 10μM Y-27362 dihydrochloride (Tocris Bioscience, cat. no. 1254). Single cells were allowed to expand clonally and individual colonies were screened by PCR for targeted homozygous insertion of 2A-Achilles-CL1-PEST-NLS immediately before the stop codon of HES7. Positive clones were sequenced to ensure no undesired mutations in the HES7 locus had been introduced by the genome editing process. Three homozygous clones were further validated by qRT-PCR and immunofluorescence.

An identical approach was used to target the Hes7 locus in mouse E14 ESCs, except the pGuide-it-tdTomato and targeting vectors were delivered by lipofection using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen cat. no. L3000001). Following sorting, TdTomato+ cells were seeded at low density on gelatin-coated dishes (EMD Millipore cat. no. es-006-b) in 2i medium (see below). Individual colonies were then transferred to a 96 well plate for expansion. Once ready to passage, the master plate was split onto three different 96 well plates. One plate was used for genotyping and the other two were frozen. Positive clones were then thawed, expanded, and had their genotype confirmed by PCR and sequencing. Only one clone carrying the targeted homozygous insertion of 2A-Achilles-CL1-PEST-NLS in the Hes7 locus was found and further characterized.

To generate the double reporter line HES7-Achilles; MESP2-mCherry, we co-transfected the pGuide-it-tdTomato vector containing a single guide RNA targeting the 3’ end of the MESP2 coding sequence (Extended data Table 1), and a targeting vector composed of 1kb homology arms flanking a T2A-H2B-mCherry sequence in the pUC19 backbone, in NCRM1 HES7-Achilles cells by nucleofection (Amaxa). We sorted, expanded, genotyped and sequenced individual clones as described above. Three independent instances of successful homozygous insertion were found.

To insert the constitutively expressed pCAG-H2B-mCherry reporter in the safe harbor AAVS1 locus in NCRM1 HES7-Achilles cells, we used the approach previously described by Oceguera-Yanez and colleagues28. Briefly, we cloned the H2B-mCherry sequence into the pAAVS1-P-CAG-DEST vector (Addgene) by Gibson assembly and co-transfected it along with the pXAT2 vector (Addgene) into HES7-Achilles cells. Two days after nucleofection, we selected positive clones by supplementing mTeSR1 with puromycin (0.5 μg/mL, Sigma–Aldrich cat. no. P7255) for a total of 10 days. We obtained two positive clones and confirmed the homozygous insertion of H2B-mCherry by PCR.

Mouse ESC cell culture and 2D differentiation

E14 mouse ESCs were maintained under feeder-free conditions in gelatin-coated dishes with 2i medium composed of high glucose DMEM (Gibco cat. no. 11965-118) supplemented with 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco cat. no. 35050061), 1% Non-Essential Amino Acids (Gibco cat. no. 11140-050), 1% Sodium Pyruvate (Gibco cat. no. 11360-070), 0.01% Bovine Serum Albumin (Gibco cat. no. 15260-037), 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco cat. no. 21985-023), 15% Fetal Bovine Serum (EMD Millipore cat. no. ES009B), 1000 U/mL LIF (EMD Millipore cat. no. ESG1106), 3μM CHIR99021 (Sigma Aldrich cat. no. SML1046) and 1μM PD0325901 (Stemgent cat. no. 04-006). mESCs were passaged by TryplE (Gibco cat. no. 12605010) dissociation every two days at a density of 1× 104 cells per cm2. Paraxial mesoderm differentiation was carried out as previously described 19, with small modifications. mESCs were seeded at a density of 1× 104 cells per cm2 in fibronectin-coated dishes (BD Biosciences cat. no. 356008) in N2B27 medium (StemCell Technologies cat. no. 07156 and 05731) supplemented with 25 ng/ml Activin A (R&D systems cat. no. 338-AC-050) and 12 ng/ml bFGF (PeproTech cat. no. 450-33). After 48 hours in culture, the differentiation medium was changed to high glucose DMEM (Gibco cat. no. 11965-118) supplemented with 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco cat. no. 35050061), 1% Non-Essential Amino Acids (Gibco cat. no. 11140-050), 1% Sodium Pyruvate (Gibco cat. no. 11360-070), 0.01% Bovine Serum Albumin (Gibco cat. no. 15260-037), 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco cat. no. 21985-023), 15% Fetal Bovine Serum (EMD Millipore cat. no. ES009B), 3μM CHIR99021 (Sigma Aldrich cat. no. SML1046) and 0.5 μM LDN193189 (Stemgent cat. no. 04-0074). Cells were cultured for four additional days and medium was changed daily. For live imaging experiments, cells were seeded on 24 well glass-bottom plates (In Vitro Scientific cat. no. P24-1.5H-N) on day 0 and cultured in DMEM without phenol red (Gibco cat. no. 31053028) from day 4 onwards. To extend the time spent in the oscillatory state, we additionally supplemented the differentiation medium with 50 ng/ml mFgf4 (R&D Systems cat. no. 5846-F4-025), 1 μg/ml Heparin (Sigma Aldrich cat. no. H3393-100KU), 2.5 μM BMS493 (Sigma Aldrich cat. no. B6688-5MG) and 10 μM Y-27362 dihydrochloride (CLFBR medium4) from day 4 onwards.

Human iPS cell culture and 2D differentiation

Human stem cell work was approved by Partners Human Research Committee (Protocol Number 2017P000438/PHS). We complied with all relevant ethical regulations. Written informed consent from the donor of the NCRM1 iPS cells was obtained by Rutgers University at the time of sample collection. NCRM1 iPS cells (RUCDR, Rutgers University) and lines carrying the MSGN1-Venus19 or HES7-Achilles/HES7-Achilles; pCAG-H2B-mCherry/ HES7-Achilles; MESP2-mCherry reporters were maintained in Matrigel-coated plates (Corning, cat. no. 35277) in mTeSR1 medium (Stemcell Technologies cat. no. 05851) as previously described9. Paraxial mesoderm differentiation was carried out as described9. Briefly, mature iPS cell cultures were dissociated in Accutase (Corning cat. no. 25058CI) and seeded at a density of 3 × 104 cells per cm2 on Matrigel-coated plates in mTeSR1 and 10μM Y-27362 dihydrochloride (Rocki; Tocris Bioscience, cat. no. 1254). Cells were cultured for 24-48 hours until small, compact colonies were formed. Differentiation was initiated by switching to CL medium consisting of DMEM/F12 GlutaMAX (Gibco cat. no. 10565042) supplemented with 1% Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (Gibco cat. no. 41400045), 3 μM Chir 99021 (Tocris cat. no. 4423) and 0.5 μM LDN193189 (Stemgent cat. no. 04-0074). On day 3 of differentiation, cells were changed to CLF medium consisting of CL medium with 20ng/ml murine bFGF (PeproTech cat. no. 450-33). Media was changed daily.

For live imaging experiments, differentiation was performed as described above, except cells were seeded on 35 mm matrigel-coated glass-bottom dishes (MatTek cat. no. P35G-1.5-20-C) or 24 well glass-bottom plates (In Vitro Scientific cat. no. P24-1.5H-N). DMEM/F12 without phenol red was used to reduce background fluorescence (Gibco cat. no. 21041025 ).

To extend the oscillatory window of differentiated PSM cells, we cultured HES7-Achilles cells in CLFBR medium consisting of DMEM/F12 GlutaMAX, 1% ITS, 3 μM Chir 99021, 0.5 μM LDN193189, 50 ng/ml mFgf4 (R&D Systems cat. no. 5846-F4-025), 1 μg/ml Heparin (Sigma Aldrich cat. no. H3393-100KU), 2.5 μM BMS493 (Sigma Aldrich cat. no. B6688-5MG) and 10 μM Y-27362 dihydrochloride starting on day 2 of differentiation4. Media was refreshed daily.

To automatically track oscillations in individual cells within the culture, we mixed HES7-Achilles; pCAG-H2B-mCherry cells with NCRM1 cells in a ratio of 1:100 at the time of seeding for pre-differentiation. Cells were then differentiated normally under CLFBR conditions.

To examine oscillations in isolated cells, we differentiated HES7-Achilles cells normally (CL medium) for the first two days on 35mm plastic dishes and dissociated them with Accutase (Corning cat. no. 25058CI) on day 2 of the differentiation protocol. Cells were reseeded on fibronectin-coated (BD Biosciences cat. no. 356008) or bovine serum albumin (BSA)-coated (Gibco cat. no. 15260-037) 24 well glass-bottom plates at high (500,000 cells per well) or low density (25,000-50,000 cells per well) in CLFBR media. Using our regular DMEM/F12 base media resulted in poor survival of low density cultures. We found that using RHB Basal media (Takara/Clontech cat. no. Y40000), supplemented with 5% knockout serum replacement (KSR; Thermo Fisher cat. no. 10828-028) improved survival significantly.

Explant culture

Explant culture was performed as previously described4. LuVeLu CD1 E9.5 mice (both male and female) were sacrificed according to local regulations in agreement with national and international guidelines. We complied with all relevant ethical regulations. Study protocol was approved by Brigham and Women’s Hospital IACUC/CCM (Protocol number N000478). Sample size was not estimated, nor were randomization or blinding performed. Tailbud was dissected with a tungsten needle and ectoderm was removed using Accutase (Life Technologies). Explants were then cultured on fibronectin-coated plate (LabTek chamber). The medium consists of DMEM, 4.5g/L Glucose, 2mM L-Glutamine, non-essential amino acids 1x (Life Technologies), Penicillin 100U/mL, Streptomycin 100μg/mL, 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), Chir-99021 3μM, LDN193189 200nM, BMS-493 2.5 μM, mFgf4 50ng/mL, heparin 1μg/mL, HEPES 10mM and Y-27632 10μM. Explants were incubated at 37°C, 7.5% CO2. Live imaging was performed on a confocal microscope Zeiss LSM 780, using a 20X objective (note that the tiling could create lines between the different images). For micropattern culture, explants were cultured overnight in standard condition, then dissociated using Trypsin-EDTA, and plated on fibronectin-coated CYTOOchips Arena in a CYTOOchamber 4 wells.

Small Molecule Inhibitor Treatments

To inhibit Notch signaling, 25 μM DAPT (Sigma Aldrich cat. no. D5942-5MG) was added to CLFBR media on day 2 of differentiation. To inhibit FGF signaling, PD0325901 (Stemgent 04-006) or PD173074 (Cayman Chemical cat. no. 219580-11-7) were added to CL or CLFBR media at the indicated concentrations. Wnt signaling was inhibited with the tankyrase inhibitors XAV939 (Sigma Aldrich cat. no. X3004) and IWR-1 (Sigma Aldrich cat. no. I0161) at 2μM and 12μM, respectively, in CLFBR medium. Cell division was blocked by arresting cells at early S phase with 5μM Aphidicolin (Sigma Aldrich cat. no. A0781) in CLFBR medium. Cells were pre-treated for 24 hours with Aphidicolin prior to imaging (during day 2). The onset of imaging was thus delayed by one day and started only on day 3. Aphidicolin was maintained in the medium throughout imaging. Latrunculin A (Cayman Chemical ca. no. 10010630), which inhibits actin polymerization and YAP signaling, was used at 350 nM in RHB basal media supplemented with CLFBR and 5% KSR. Mouse explants and micropatterned cultures were treated with PD0325901 (Sigma- concentration as described in the text) and PD173074 (Sigma - 250nM).

Time-lapse Microscopy

Time lapse-imaging of PSM cells was performed on a Zeiss LSM 780 point-scanning confocal inverted microscope fitted with a large temperature incubation chamber and a CO2 module. An Argon laser at 514 nm and 7.5% power was used to excite the Achilles fluorophore through a 20X Plan Apo (N.A. 0.8) objective, whereas a DPSS 561 laser at 561nm and 2% laser power was used to excite mCherry samples. Images were acquired with an interval of 18 minutes in the case of human samples and 4.5 minutes for mouse samples, for a total of 24-48 hours. A 3x3 tile of 800x800 pixels per tile with a single z-slice of 18 μm thickness and 12-bit resolution was acquired per position. Multiple positions, with at least two positions per sample, were imaged simultaneously using a motorized stage. Explant imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM780 microscope using a 20X/0.8 objective. For mouse cells imaging, single section (~19.6μm wide) with tiling (3x3) of a 512x512 pixels field was acquired every 7.5 minutes (in most experiments) at 8-bit resolution.

Immunostaining

For immunostaining of 2D cultures, cells were grown on Matrigel-coated glass-bottom plates or 12mm glass coverslips placed inside plastic dishes or, alternatively, on 24 well glass-bottom plates (In Vitro Scientific cat. no. P24-1.5H-N). Cells were rinsed in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) and fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences cat. no. 15710) for 20 minutes at room temperature, then washed 3 times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Typically, samples were permeabilized by washing three times for three minutes each in Tris buffered saline (TBS) with 0.1% Tween (known as TBST) and blocked for one hour at room temperature in TBS-0.1% Triton-3% FBS. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4⁰C with gentle rocking. Primary antibodies and dilution factors are listed in Ext. Data Table 2. Following three TBST washes and a short 10-minute block, cells were incubated with Alexa-Fluor conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500) and Hoechst33342 (1:1000) overnight at 4⁰C with gentle rocking. Three final TBST washes and a PBS rinse were performed, and cells were mounted in Fluoromount G (Southern Biotech cat. no. 0100-01). Images were acquired using either a Zeiss LSM880 or LSM780 point scanning confocal microscope with a 20X objective.

For visualizing phospho-ERK1/2 in 2D monolayer differentiated cells, cells were transferred onto ice and quickly rinsed in ice-cold PBS containing 1 mM sodium vanadate (NaVO4). Next, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, rinsed three times in PBS and dehydrated in cold methanol at −20⁰C for 10 minutes. Following three PBS rinses, cells were blocked in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% goat serum and incubated in pERK1/2 antibody diluted in antibody buffer (0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% BSA in PBS) overnight at 4⁰C. Cells were washed in PBS, and incubated in blocking solution for 10 minutes and with secondary antibody and Hoechst33342 in antibody buffer overnight at 4⁰C. Cells were rinsed three times in PBS before mounting and imaging as described above.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and qPCR

Cells were harvested in Trizol (Life Technologies cat. no. 15596-018), followed by precipitation with Chloroform and Ethanol and transferred onto Purelink RNA Micro Kit columns (Thermo Fisher cat. no. 12183016) according to manufacturer’s protocol, including on-column DNase treatment. A volume of 22 μl RNase-free water was used for elution and RNA concentration and quality were assessed with a Nanodrop. Typically, between 0.2-1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript III First Strand Synthesis kit (Life Technologies cat. no. 18080-051) and oligo-dT primers to generate cDNA libraries.

For real time quantitative PCR, cDNA was diluted 1:30 in water and qPCR was performed using the iTaq Universal SYBR Green kit (Bio-Rad cat. no. 1725124). Each gene-specific primer and sample mix was run in triple replicates. Each 10 μl reaction contained 5 μl 2X SYBR Green Master Mix, 0.4 μl of 10 μM primer stock (1:1 mix of forward and reverse primers), and 4.6 μl of diluted cDNA. qPCR plates were run on a Bio-Rad CFX384 thermocycler with the following cycling parameters: initial denaturation step (95°C for 1 minute), 40 cycles of amplification and SYBR green signal detection (denaturation at 95°C for 5 seconds, annealing/extension and plate read at 60°C for 40 seconds), followed by final rounds of gradient annealing from 65°C to 95°C to generate dissociation curves. Primer sequences are listed in Extended Data Table 3. All unpublished primers were validated by checking for specificity (single peak in melting curve) and linearity of amplification (serially diluted cDNA samples). For relative gene expression analysis, the ΔΔCt method was implemented with the CFX Manager software. PP1A was used as the housekeeping gene in human iPSC samples, whereas Actb was used in mouse ESC samples. Target gene expression is expressed as fold change relative to undifferentiated iPS/ESC cells.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

To determine the fraction of PSM cells expressing pMsgn1-Venus/MSGN1-Venus, cultures were dissociated in Accutase and analyzed by flow cytometry using an S3 cell sorter (Biorad). Undifferentiated ESCs or iPS cells, which do not express the fluorescent protein, were used as a negative control for gating purposes. Samples were analyzed in biological triplicates. Results are presented as the percentage of Venus positive cells in the sorted fraction.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR

Binding of NOTCH1 to the promoters of ACTB, LNFG and HES7 was analyzed by ChIP. Cells were crosslinked for 30 minutes using ChIP Cross-link Gold reagent (Diagenode, C01019027), rinsed with PBS and then 1% formaldehyde for 15 minutes. After quenching with 125μM glycine and rinsing the crosslinked cells with ice-cold PBS, cells were harvested using a cell scraper. Cell lysis and pulldown of chromatin with A/G protein coated magnetic beads was performed on approximately 300 thousand cells per immunoprecipitation using MAGnify™ ChIP kit (ThermoFisher cat. no. 492024) following manufacturer’s instructions. Chromatin fragmentation was performed using a Covaris M220 sonicator for 5 minutes (75 watts PIP, 5% DF and 200 cycles/burst). NOTCH1 immunoprecipitation was performed using 3.3 μg of anti-NOTCH1 (D1E11, 3608S Cell Signaling) per immunoprecipitation. This antibody binds the transactivation domain of NOTCH1 and has been successfully used for ChIP-seq applications in the past29. 0.5 μg of anti-Acetyl-Histone H3 (Lys9) (C5B11, 9649S Cell Signal) was used. Fold enrichment (2−ΔCt) was calculated relative to isotype IgG controls, immunoprecipitated with 3.3 μg of normal rabbit IgG (2729S Cell Signal). Enriched loci after ChIP were interrogated by qPCR using primers designed to amplify ~100bp surrounding previously identified RBPJ binding sites in the HES7 and LFNG promoters30,31.

Image Analysis

Time lapse movies of HES7-Achilles were first stitched and separated into subsets by position in the Zen program (Zeiss). Then, background subtraction and Gaussian blur filtering were performed in Fiji32 to enhance image quality. When single cell tracking was not performed, a small region of interest (ROI) was drawn and the mean fluorescence intensity over time was calculated. Intensity is presented in arbitrary units. When appropriate, the moving average was subtracted with window size of 3 hours for human PSM (i.e. 10 timepoints) and mouse PSM (i.e. 40 timepoints), and then normalized between 0 and 1. For smoothening, we applied the Sgolay filtering function in MATLAB.

Following moving average subtraction, we performed Fourier transformation of HES7-Achilles intensity profiles to determine the predominant period of oscillations. The Hilbert transformation was used to calculate the instantaneous frequency and phase of HES7-Achilles oscillations from ROIs. To compare the phase between ROIs in DMSO and PD17 or PD03 treated cultures, we used the Hilbert transformation to calculate the instantaneous phase of each curve separately, then subtracted the phase of treated cells from untreated cells at each timepoint. Phase difference is expressed as the average of instantaneous phase differences before the arrest of oscillations in treated cells.

To manually track oscillations in mouse ESC-derived PSM cells as well as isolated or sparse human HES7-Achilles cells in a NCRM1 background, we tracked cells by drawing a circle around the nucleus of an individual cell at each time point and measuring fluorescence intensity inside the ROI. To remove saturated pixels corresponding to autofluorescent debris in mESC-PSM movies, we set pixels with intensity >700 a.u. (above dynamical range of mHes7-Achilles) to background level (=100 a.u.) in MATLAB. In the case of hMESP2-mCherry, we established a threshold for activation (25 a.u.) by taking the mean of several ROIs representing the background noise.

For mouse explants, kymographs were done in Fiji32 by drawing a rectangle from the starting center of the traveling waves to the edge of the explant perpendicular to the direction of the wave. The intensity along the long axis was measured and the image was smoothened (this filter replaces each pixel with the average of its 3 × 3 neighborhood).

Fluorescence intensity profiles were done by selecting a circular region of interest in Fiji32 and by measuring the total intensity over time for this region; LuVeLu intensity is given in arbitrary units (normalized by the initial value) and a smoothing function (average over three points) was applied. Fluorescence intensity shows the mean fluorescence smoothed by applying a moving average over five points (with equal weight). For the quantification of micropattern experiments, a region of interest encompassing the entire surface of one circle was drawn and the LuVeLu intensity was measured using the Time Series Analyzer V3 plugin on Fiji32. The period was measured by measuring the time between two peaks or two troughs. The average intensity was measured by averaging the intensity over 3 hours to avoid instantaneous variations dues to the oscillations.

Automatic image segmentation and cell tracking

Cells were automatically segmented and tracked on the microscopy movies using a custom algorithm. To this end, we first identified and listed the cell positions and cell shapes using a detection of the connected components of a thresholded image applied to the pCAG-H2B-mCherry channel (using the bwconncomp Matlab algorithm). For reliability, we used a minimal denoising based on morphological operations (imopen then imclose functions of Matlab, both with radius 1px). The shape of the cell was used to detect the level of expression of HES7-Achilles by considering the average HES7-Achilles level within the connected component detected in the pCAG-H2B-mCherry channel. This provides us with a list of cell positions together with the associated average HES7-Achilles intensity, for each frame of the microscopy movie.

Tracks were then reconstructed consecutively by finding, given a cell in frame k, the closest cell in frame k+1 within a distance of 20 μm, consistent with the typical movement of a cell between two frames, and not too large to avoid switching tracks. This provided us with cells tracks, that trajectories of the cells in the microscopy field. By matching these tracks with the recorded HES7-Achilles intensity, we thus obtained HES7-Achilles activity as a function of time for each single cell tracked by the algorithm.

Phase analysis

While collective oscillations appear very regular, HES7-Achilles expression in single cells shows heterogeneous profiles and fluctuating background fluorescence intensity (see Video S5), and phase detection requires specific attention33. To derive accurately a phase of oscillation for a single cell, we used a custom method based on Hilbert transform (Method 1), and two control methods providing very similar results (Methods 2 and 3). We relied on Method 1 for the main figures as it provided an accurate estimate even during the first periods of the oscillations.

Method 1: Hilbert transform;

The Hilbert transform is a functional transform of time series whose argument provides an efficient estimate of the phase of a signal (and its modulus, the envelope amplitude). Hilbert transforms are quite sensitive to drifts in the signals and changes in the shape of the oscillation. Classically, Hilbert transform follows a detrending pre-processing based on removing a linear drift. To improve the evaluation of the phase using the Hilbert transform in the present case where drifts are nonlinear and amplitudes vary in time, we used a local renormalization algorithm, similar to33, consisting in (i) centering locally the signal using a moving average computed over a time window of 6h around the current time point (Matlab function movmean, 6 hours providing a duration slightly larger than the period of the average signal), allowing correcting for local changes in the average signal, and (ii) normalizing the amplitude dividing the centered signal by a sliding standard deviation, computed on the same window of 6h (Matlab function movstd). We then evaluated the phase using the hilbert function of Matlab.

Method 2: Cross-correlations;

We also developed a methodology for evaluating phase shifts between two signals S1(t) and S2(t) based on a local cross-correlations estimate. In detail, at a given time t, the algorithm finds the delay dt between 0 and 4h maximizing the correlation between the chunk of signal S1(s) and S2(s+dt) over the time interval s [t,t+6h]. We developed this algorithm using a custom Matlab code and used this algorithm to compute phase differences between pairs of cells.

Method 3:

A third method used for control was developed based on detecting peaks of the signals. In detail, we detected the times at which the signal peaks using the findpeaks function of Matlab. When peaks are detected at times t0, t1, …, tn, the phase of the signal at a given time t ∈ [ti, ti+1] was defined as the relative fraction of time between between the two consecutive peaks, . findpeaks was also used to count the number of oscillations before arrest at the single cell level.

Synchronization

To quantify the level of synchrony between the HES7-Achilles expression in multiple cells, we first selected tracks that were followed for multiple periods of oscillations (minimal duration of 15hours and Fourier transform larger than a lower threshold - the selection using Fourier transform did not significantly modify the statistics). Next, we computed the Kuramoto order parameter, also known as vector strength20,34 of a given set of signals phases. Considering n signals with phases θ1, .., θn, the Kuramoto order parameter Z is defined by

where i is the complex variable. This provides a complex number whose angle corresponds to the average phase and whose modulus (norm) quantifies the level of synchrony. The modulus of Z is indeed equal to 1 when all oscillators have the same phase (in which case Z = eiθ where θ is the common phase of all oscillators), and it is equal to 0 when the phases are uniformly spread between 0 and 2π. For uniformly distributed phases with standard deviation equal to σ, the amplitude of the Kuramoto order parameter is equal to , a function smoothly decaying from 1 to 0 as σ goes from 0 to π.

Using the phases we derived for each track, we evaluated as a function of time the order parameter and its modulus. Of course, because of natural experimental fluctuations and the finite number of cells considered, asynchronous cells are characterized by a low, but non-zero, Kuramoto order parameter. To assess whether the observed Kuramoto order parameter was statistically consistent with synchrony, we evaluated what would be the level of Kuramoto order parameter norm for asynchronous sets of cells. To this end, we used our evaluated phases θ1(t), .., θn(t) and constructed multiple surrogate datasets by shuffling the phase relationships between those trajectories, but preserving their intrinsic frequency of oscillations. To this end, we drew time-shifts uniformly in [0,T] where T is the total time considered for the phases, for each cell. This yields n times τ1, .., τn, from which we derived the Kuramoto order parameter for a set of phases θ1(t + τ1), .., θn(t + τn), wrapped on the interval [0,T], i.e. times t+τi are taken modulo T, and computed the associated order parameter. We repeated this randomization 1000 times and obtained a stable distribution of the Kuramoto order parameter for phases with no specific phase relationship. This provided a level of Kuramoto order parameter consistent with asynchrony. We then tested whether the order parameter found for the original data was consistent with synchrony by comparing this value to the distribution of surrogate order parameters.

Spatio-temporal wave

To assess whether the data were organized into a spatio-temporal wave pattern, we used our extensive dataset containing both the instantaneous positions and instantaneous phases for the cells that were detected by our automatic segmentation and tracking algorithm. For each pair of cells, we computed their instantaneous (physical) distance as well as their phase-shift. This provided us with a very large dataset, that we organized according to ranges of distances, chosen so that each set contained approximately the same number of cell pairs (distance less than 160μm, between 160 and 265 μm, between 265μm and 530μm, and larger than 530μm - the number of cells at a distance larger than 530μm was not kept equal to the other numbers to keep sufficient resolution). We then plotted the distribution of phase shifts for each distance class, and used the 2-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (Matlab function kstest2) to compare two-by-two, these distributions (we took care of the classical sample-size bias of the test by selecting large subsets of equal size for each distance class35), and obtained a p-value for whether the two samples were drawn from the same distribution or not. We consistently found that the distribution of phase shifts was not dependent on the distance between cells.

Diffusion coefficient

To characterize cellular movement from automated cell tracks and test the hypothesis that the cells movement was consistent with freely diffusing particles (Brownian motion), we computed the mean square displacement of each cell in an automatically identified track a given time lag. In detail, the mean square displacement is defined by: where k is a tracked cell label, t is time, and the angular bracket indicate that an average on all possible t is taken (i.e., if track k lasts up to time Tk, the average is taken for ∈ {1, .., Tk − τ} ). Freely moving cells with diffusivity D should have a linear mean squared displacement . By fitting a linear curve to the mean square displacement for all cells, we obtained an estimate for D as well as a p-value for assessing the validity of the linear fit (ANOVA).

Period of oscillations

The period of oscillations in automatically tracked cells was computed using fast Fourier transform (Matlab function fft) of the centered HES7-Achilles expression for each cell tracked (the centering consisted only of removing the mean value of the signal in time). Peaks of the Fourier transforms were identified using the findpeaks Matlab function, and the most prominent peak was used to compute the period of the signal. To confirm this estimate of the period, we used an alternative method based on identifying the peaks in HES7-Achilles expression for each cell and computing the difference between the times of the peaks. We found a very good agreement between the two methods.

Phase Shifts

To assess the relative phase shift between two samples at the single cell level (e.g. control vs. PD03), we first obtained the phases as a function of time for each automatically tracked cell as described above. We then calculated the phase difference between all possible pairs of cells between the two samples at all timepoints and displayed these data in histograms. We additionally computed the mean phase shift across all timepoints for all pairs of cells and the corresponding standard deviation. To compare the phase shift between different pairs of samples, we used non-parametric one-way ANOVA with the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Cell Division Analysis

Our automated cell tracking algorithm (described above) did not detect cell division, but rather selected one daughter cell at random and continued tracking without interruption. Thus, we resorted to manual tracking for the detection of cell division. We used the Fiji32 plugin ManualTracks and recorded the timepoints at which cells underwent mitosis. Manual tracking was performed on the pCAG-H2B-mCherry channel, such that chromatin compaction during cell division was clearly identifiable and tracks were completely independent from HES7-Achilles intensity. Cell division time was defined as the time elapsed between the time a cell first divides and the time one of its daughter cells divides again. Once cell division events were manually identified, we used an automatic tracking to recover the tracks before and after cell division. In detail, given a cell division event at time t and at a given location of the field, we identified in our automatically identified cell the closest match. When the distance between the automatically and manually identified cells was small enough (here, below 21 μm distance), we recovered the HES7-Achilles expression from the associated already identified track. If there was no cell identified near the manually identified location (in some rare cases, manually identified dividing cells had not been detected by the algorithm), we used locally a version of the automatic tracking algorithm (in a sub-image of 5.3x5.3μm) to derive a cell location and an associated HES7-Achilles expression. This data was then processed exactly as the automatically identified tracks, and we obtained the phases of the oscillations of the dividing cells. We then built the histogram of the phases at cell division, and used the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to assess whether the distribution of phases was consistent with a uniform distribution, indicating no correlation between phase in the HES7-Achilles expression and cell division. To this end, we used the makedist Matlab function to create a uniform distribution and used the kstest Matlab function to compare our sample of phases at cell division with a uniform distribution. This provided a test of hypothesis together with the p-value indicated in the figure legend.

Statistical Analyses

In box and whiskers plots, middle hinge corresponds to median, lower and upper hinges correspond to 1st and 3rd quartiles, lower and upper whiskers correspond to minimum and maximum. Ordinary one-way ANOVA was performed in cases where data was Gaussian and Tukey or Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons. In cases where data was not Gaussian (e.g. phase shifts), we used non-parametric one-way ANOVA with the Kruskal–Wallis test. For time series, such as the Kuramoto order parameter over time, we used paired ANOVA with matched time points. Details of statistical analyses are indicated in figure legends. All differentiation experiments were performed a minimum of three independent times (rounds of differentiation), each containing at least three technical replicates (wells) per condition.

Preparation of single-cell suspensions for single cell RNA-sequencing

Single-cell dissociation protocols for the various tissues and cells analyzed were optimized to achieve >90% viability and minimize doublets prior to sample collection. For human iPS differentiation, 3x104 MSGN1-Venus cells were seeded on Matrigel-coated 24-well plates 48 hours prior to differentiation. Cells were differentiated as described above. All samples (days 1-4 and hiPS control samples) were dissociated, collected and captured on an inDrops setup on the same day, two biological replicates per sample. For dissociation, cells were briefly rinsed in PBS, and incubated in TrypLE Express (Gibco) for 5 min at 37°C. Dissociated cells were run through a 30 μm cell strainer, spun down at 200g for 4 min at 4°C and resuspended in 100 μl 0.5% BSA in PBS.

For mESC differentiation, 1x104 pMsgn1-Venus cells were seeded on fibronectin-coated 6-well plates and differentiated as described above. Samples for days 0 and days 2-5 were dissociated in TryplE Express (Gibco) for 3-10 minutes, washed several times in PBS, passed through a 40 μm cell strainer and resuspended in 0.1% BSA in PBS with Opti-Prep at a final density of 200,000 cells/ml. All samples were dissociated, collected and captured on the same day in biological duplicates.

For generating cell suspensions from mouse embryo tailbuds, E9.5 embryos (25-28 somite stage) from CD-1 IGS mice (Charles River) were collected and the posterior part of the embryo, including the last 3 pairs of somites, was carefully dissected from two littermate embryos and subsequently processed as separate samples. Tissues were collected in PBS and dissociated in TrypLE Express for 10 min at 37°C. Cells were rinsed in PBS/EDTA, transferred to 0.5% BSA in PBS, mechanically separated by trituration and run through a 30 μm cell strainer. Cells were spun down at 200 g for 4 min at 4°C and resuspended in 100 μl 0.5% BSA in PBS.

The following number of cells were sequenced per sample:

-

Human iPSC differentiation samples (two biological replicates processed independently)

For each replicate hiPS control, 1000 cells; Day 1, 1500 cells; Day 2, 1500 cells; Day 3, 1500 cells; Day 4, 1500 cells

-

Mouse ESC differentiation samples

ESC Day 0: 2341 cells. Day 2: 2417 cells. Day 3: Rep. 1 3106 cells, Rep. 2 3189 cells. Day 4: Rep. 1 2939 cells, Rep. 2 2532 cells. Day 5: Rep. 1 1894 cells, Rep. 2 3060 cells.

Mouse embryo samples: tailbud cells from two E9.5 embryos (2x 3000 cells processed independently)

Every sample was collected as biological replicate and sequencing data from both samples were combined for data analysis. Actual number of cells captured on inDrops was twice as many as sequenced for backup purposes.

Barcoding, sequencing, and mapping of single-cell transcriptomes

Single-cell transcriptomes were barcoded using inDrops12 as previously reported36, using “V3” sequencing adapters. Following within-droplet reverse transcription, emulsions consisting of ~1,000-3,500 cells were broken, frozen at −80C, and prepared as individual RNA-seq libraries. inDrops libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 using the NextSeq 75 High Output Kits using standard Illumina sequencing primers and 61 cycles for Read1, 14 cycles for Read2, 8 cycles each for IndexRead1 and IndexRead2. Raw sequencing data (i.e. FASTQ files) were processed using the inDrops.py bioinformatics pipeline available at github.com/indrops/indrops. Transcriptome libraries were mapped to human or mouse reference transcriptomes built from the GRCh37 / hg19 (GCF_000001405.13) or GRCm38 / mm10 (GCF_000001635.20) genome assemblies, respectively. Bowtie version 1.1.1 was used with parameter −e 200.

Processing of single-cell RNA-seq data

Single-cell counts matrices were processed and analyzed using ScanPy37 (1.4.4) and custom Python scripts (see Code Availability). Low complexity cell barcodes, which can arise from droplets that lack a cell but contain backround RNA, were filtered in two ways. First, inDrops data were initially filtered to only include transcript counts originating from abundantly sampled cell barcodes. This determination was performed by inspecting a weighted histogram of Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) – gene pair counts for each cell barcode, and manually thresholding to include the largest mode of the distribution (in all cases >80% of total sequencing reads). Second, low complexity transcriptomes were filtered out by excluding cell barcodes associated with <250 expressed genes. Transcript UMI counts for each biological sample were then reported as a transcripts x cells table, adjusted by a total-count normalization, log-normalized, and scaled to unit variance and zero mean. Unless otherwise noted, each dataset was subsetted to the 2000 most highly variable genes, as determined by a bin-normalized overdispersion metric. Mouse E9.5 data were filtered for doublet-like cells with Scrublet38, which simulates synthetic doublets from pairs of scRNA-seq profiles and assigns scores based on a k-nearest-neighbor classifier on the PCA-transformed data.

Low Dimensional Embedding and Clustering

Unless otherwise stated, processed single-cell data were projected into a 50-dimensional principal component analysis (PCA) subspace. The mouse E9.5 PSM (k=20) nearest-neighbor graph used Euclidean distance and 20 PCA dimensions. The mESC and hiPSC neighbor graphs were constructed using the batch-balanced ‘bbknn’ method39. Clustering was performed using Louvain40 and Leiden41 community detection algorithms.

Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes

Transcripts with significant cluster-specific enrichment were identified by a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test comparing cells of each cluster to cells from all other clusters in the same dataset. Genes were considered differentially expressed if they met the following criteria: log fold-change >0, adjusted p-value < 0.05. FDR-correction for multiple hypothesis testing was performed as described by Benjamini-Hochberg42. The top 100 differentially expressed genes, ranked by FDR-adjusted p-values, associated fold changes, and sample sizes (number of cells per cluster) are reported in Table S1. Gene names for the top 20 differentially expressed transcripts are reported in Extended Figs. 2D (Mouse E9.5), 3C (Mouse E9.5 PSM), 3H (Mouse ESC), and 3M (Human IPSC).

Pseudo-Spatiotemporal Ordering and Identification of Dynamically Varying Genes

Pseudo-spatiotemporal orderings were constructed by randomly selecting a root cell from the following clusters: ‘NMP’ (Mouse E9.5 PSM, Fig. 2c); ‘d0 ESC’ (mESC, Fig 2d); ‘d0 iPSC’ (hiPSC, Fig 2f) and calculating the diffusion pseudotime (DPT) distance of all remaining cells relative to the root. Trajectories were assembled for paths through specified clusters, with cells ordered by DPT values, as previously reported43. Dynamically variable genes along the Mouse E9.5 PSM trajectory were identified as follows. Briefly, sliding windows of 100 cells were first scanned to identify the two windows with maximum and minimum average expression levels for all genes individually. For each gene, a t-test was then performed between these two sets of 100 expression measurements (FDR < 0.01). Scaled expression values for significant genes were then smoothened over a sliding window of 100 cells, ranked by peak expression, and plotted as a heatmap Fig 2c. The full list of dynamically expressed genes appears in Table S2.

Machine Learning Classification of Cell States

Cell state prediction utilized the KNeighborsClassifier, RandomForestClassifier, LinearDiscriminantAnalysis (LDA), and MLPClassifier (NeuralNetwork) classifier methods from scikit-learn (0.20.3). Classifiers were trained on the full Louvain cluster-annotated PCA subspace-projected mouse E9.5 dataset (n=4,367 cells) with default settings and k=20 for KNeighborsClassifier. mESC and hiPSC cell states were predicted after subsetting matching gene symbols for the E9.5 variable gene list, and projecting into the E9.5-defined PCA subspace.

Data Availability

Raw sequencing data, raw and normalized counts data, and single-cell clustering assignments are available from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), Accession # GSE114186. Online interactive versions and downloadable versions of the analyzed scRNA-seq datasets, as well as scRNA-seq transcripts x cells counts tables can be accessed at https://tinyurl.com/DiazPourquie2019 and as follows.

Mouse E9.5 tSNE clustering analysis (Fig. 2a and Extended Fig. 2c):

https://tinyurl.com/DiazPourquie2019-mE95

Mouse E9.5 k-nearest neighbor graph of paraxial mesoderm and neural clusters (Fig 2b–c and Extended Fig 3a–e):

https://tinyurl.com/DiazPourquie2019-mE95-PSM

Mouse ESC cultures Day 0 – Day 5 (Fig 2d–e, Extended Figs. 3f–j): https://tinyurl.com/DiazPourquie2019-mESC

Human iPSC cultures Day 0 – Day 4 (Fig 2f–g and Extended Figs. 3k–o):

Software & Code Availability

Single-cell RNA sequencing data were processed and analyzed using publicly available software packages: https://github.com/indrops/indrops and https://github.com/AllonKleinLab/SPRING. Downstream analysis was performed in ScanPy37 (1.4.3), using Python 3.6.8. Python code and Jupyter notebooks for reproducing single-cell analyses appearing in Fig 2 and Extended Data Figures 2–4 are available at https://github.com/wagnerde/Diaz2019. This Github link also includes detailed instructions for installing necessary python software environment including the following packages and their dependencies: anndata(0.6.22.post1), bbknn(1.3.6), fa2(0.3.5), ipython(7.8.0), jupyterlab(1.1.4), leidenalg(0.7.0), louvain(0.6.1), matplotlib(3.0.3), multicoretsne(0.1), numba(0.45.1), numpy(1.17.2), pandas(0.25.1), pytables(3.5.2), python(3.6.7), python-igraph(0.7.1.post7), scanpy(1.4.4.post1), scikit-learn(0.21.3), scipy(1.3.1), scrublet(0.2.1), seaborn(0.9.0), statsmodels(0.10.1), umap-learn(0.3.10). Force-directed layouts of single-cell graphs were generated using the ForceAtlas2 algorithm in Gephi (0.9.1).

Availability of Materials

All materials used in this study, including stem cell lines carrying knock-in reporters, are available by request from the corresponding author.

Extended Data

Extended data Figure 1.

a, Scheme illustrating the maturation stages of paraxial mesoderm. aPSM, anterior PSM; DF, determination front; MPCs, mesodermal precursor cells; pPSM, posterior PSM; NMPs, neuromesodermal progenitors. b, Top: Immunofluorescence staining for the cadherins Cdh1 and Cdh2 (top), and the pluripotency factor Pou5f1 (bottom) in differentiating mESCs (left) and hiPSCs (right). n=4 independent experiments. Scale bar = 100 μm. c, qRT-PCR for the epiblast marker Fgf5, the NMP/mesodermal marker T/Bra, and the MPC/PSM markers Tbx6, Msgn1 and Rspo3 on days 2-6 of mESC differentiation. Relative expression shown as fold change relative to ESC (day 0). Mean ±SD. n=3 d, Percentage induction of the mESC pMsgn1-Venus reporter and the hiPSC MSGN1-Venus reporter as determined by FACS. Mean ±SD. n=12 (mESC), n=8 (hiPSC) e, Gating strategy and representative FACS plots for quantification of pMsgn1-Venus/MSGN1-Venus induction. f, qRT-PCR for cyclic genes (HES7, LFNG), posterior PSM markers (MSGN1, TBX6, RSPO3), determination front markers (MESP2, RIPPLY2), and anterior PSM markers (MEST, FOXC2) on days 1-4 of human iPSC differentiation. Relative expression shown as fold change relative to iPS (day 0). Mean ±SD. n=3 g, Diagram outlining the targeting strategy used to generate Hes7-Achilles/HES7-Achilles knock-in reporter lines in mouse ESCs and human iPSCs. h, Normalized Hes7-Achilles fluorescence intensity for three mESC-derived PSM cells imaged in CL medium on day 4 of differentiation. n=4 independent experiments i, Representative Fourier transform of Hes7-Achilles oscillations in mESC-derived PSM cells indicating the predominant period. n=19 cells j, Total time spent in the oscillatory state for Hes7-Achilles mESC-derived PSM cells cultured in CL or CLFBR medium from day 4 onwards. Middle hinge corresponds to median, lower and upper hinges correspond to 1st and 3rd quartiles, lower and upper whiskers correspond to minimum and maximum. n=8 (CL), n=12 (CLFBR) k, qRT-PCR comparing relative expression levels of Msgn1, Lfng, T/Bra and Tbx6 in mESC-derived PSM cells cultured in CL or CLFBR medium from day 4 onwards. Relative expression shown as fold change relative to ESC (day 0). Mean ± SD. n=3 l, Snapshots of HES7-Achilles fluorescence in human iPSC-derived PSM cells showing peaks and troughs over the course of 13.5 hours in CL medium on day 2 of differentiation. n=25 independent experiments. Scale bar = 100μm m, Representative quantification of HES7-Achilles fluorescence intensity in a small region of interest from day 2 to day 3 of human iPSC differentiation. n=25 independent experiments n, Representative Fourier transform of HES7-Achilles oscillations indicating the predominant period in day 2 human iPSC-derived PSM cells in CL medium. n=25 independent experiments o, Representative instantaneous frequency in Hertz (calculated by Hilbert transformation) of HES7-Achilles oscillations in human iPSC-derived PSM cells from day 2 to day 3 of differentiation in CL medium. n=25 independent experiments p, Representative instantaneous frequency in Hertz (calculated by Hilbert transformation) of HES7-Achilles oscillations in human iPSC-derived PSM cells from day 2 to day 3 of differentiation in CLFBR medium. n=33 independent experiments q, Quantification of HES7-Achilles fluorescence in human iPSCs differentiated for 48 hours without the BMP inhibitor LDN93189 (CHIR99021 only medium). n=3 independent experiments r, Total number of HES7-Achilles oscillations for human iPSC-derived PSM cells cultured in CL or CLFBR medium from day 2 onwards. Mean ±SD. n=15 s, qRT-PCR comparing relative expression levels of HES7, LFNG, TBX6 and MSGN1 in human iPSC-derived PSM cells cultured in CL or CLFBR medium from day 2 onwards. Relative expression shown as fold change relative to iPS (day 0). Mean ± SD. n=3

Extended Data Figure 2.

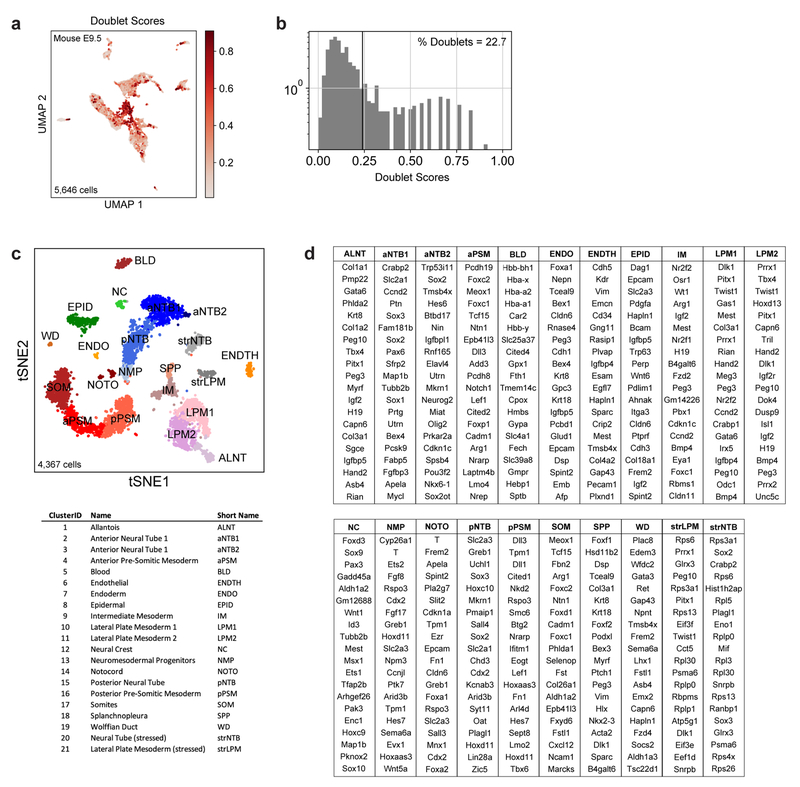

a, Pre-filtering of doublet-like cells. UMAP embedding shows all original E9.5 cells (n=5,646), colored by doublet score. Doublet scores indicate the extent to which a given single-cell transcriptome resembles a linear combination of two randomly selected cells (see Wolock et al 2019 and Methods). b, Histogram of doublet scores. Scores >0.24 were filtered from subsequent analyses. c, tSNE embedding of E9.5 cells (n=4,367) post-doublet filtering. Individual cells are colored according to annotated Louvain cluster IDs. d, Top 20 positively enriched transcripts for each Louvain cluster relative to all other clusters, as detected by a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Reported transcripts are ranked by FDR-corrected p-values (Benjamini-Hochberg). For exact sample sizes, see Extended Data Table 1.

Extended Data Figure 3.

a,f,k, ForceAtlas2 layouts of mouse E9.5 embryos, mESC, and hiPSC single-cell kNN graphs, colored by cluster ID and collection timepoints as indicated. b,g,l, Confusion matrix plots overlap of cluster and timepoint assignments, row normalized. c,h,m, Top 20 positively enriched transcripts for Louvain clusters relative to all other clusters in each dataset, as detected by a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Reported transcripts are ranked by FDR-corrected p-values (Benjamini-Hochberg). For exact sample sizes, see Extended Data Table 1. d,i,n, ForceAtlas2 layouts of single-cell kNN graphs, overlaid with log-normalized transcript counts for indicated genes. e,j,o, Top, colors indicate pseudo-temporal orderings. Bottom, heatmap of selected markers of paraxial mesoderm differentiation. Approximate locations of cluster centers are indicated.

Extended Data Figure 4.

a,c, ForceAtlas2 layouts of indicated single-cell kNN graphs, overlaid with classifier prediction scores. b,d, Heatmap of single-cell HOX gene expression levels for mESC and hiPSC datasets. Columns (individual cells) are grouped by collection timepoint. Rows are individual HOX genes ordered by position. Approximate anatomical positions of HOX paralogs are indicated at right.

Extended Data Figure 5.