Abstract

Recently, tremendous progress in synthetic micro/nanomotors in diverse environment has been made for potential biomedical applications. However, existing micro/nanomotor platforms are inefficient for deep tissue imaging and motion control in vivo. Here, we present a photoacoustic computed tomography (PACT) guided investigation of micromotors in intestines in vivo. The micromotors enveloped in microcapsules are stable in the stomach and exhibit efficient propulsion in various biofluids once released. The migration of micromotor capsules toward the targeted regions in intestines has been visualized by PACT in real time in vivo. Near-infrared light irradiation induces disintegration of the capsules to release the cargo-loaded micromotors. The intensive propulsion of the micromotors effectively prolongs the retention in intestines. The integration of the newly developed microrobotic system and PACT enables deep imaging and precise control of the micromotors in vivo and promises practical biomedical applications, such as drug delivery.

Summary

An imaging-guided ingestible microrobotic system enables deep tissue navigation and enhances targeted retention in vivo.

Introduction

Micro and nanorobots that can be navigated into hard-to-reach tissues have drawn extensive attention for the promise to empower various biomedical applications, such as disease diagnosis, targeted drug delivery, and minimally invasive surgery (1–6). Chemically powered motors, in particular, show great potential toward in vivo application thanks to their autonomous propulsion and versatile functions in bodily fluids (7–11). However, imaging and control of micromotors in vivo remain major challenges for practical medical investigations, despite the significantly advanced development of micromotors (12–15). The ability to directly visualize the dynamics of micromotors with high spatiotemporal resolution in vivo at the whole-body scale is in urgent demand to provide real-time visualization and guidance of micromotors (14). In addition to high spatiotemporal resolution, the ideal non-invasive micromotor imaging technique should offer deep penetration and molecular contrasts.

To date, optical imaging is widely used for biomedical applications owing to its high spatiotemporal resolution and molecular contrasts. However, applying conventional optical imaging to deep tissues is hampered by strong optical scattering, which inhibits high-resolution imaging beyond the optical diffusion limit (~1–2 mm in depth) (16). Fortunately, photoacoustic (PA) tomography (PAT), detecting photon-induced ultrasound, achieves high-resolution imaging at depths that far exceed the optical diffusion limit (17). In PAT, the energy of photons absorbed by chromophores inside the tissue is converted to acoustic waves, which are subsequently detected to yield high-resolution tomographic images with optical contrasts. Leveraging the negligible acoustic scattering in soft tissue, PAT has achieved superb spatial resolution at depths, with a depth-to-resolution ratio of ~200 (18), at high imaging rates. As a major incarnation of PAT, photoacoustic computed tomography (PACT) has attained high spatiotemporal resolution (125-μm in-plane resolution and 50-μs frame−1 data acquisition), deep penetration (48-mm tissue penetration in vivo), and anatomical and molecular contrasts (Text S1)(19–21). With all these benefits, PACT shows great promise for real-time navigation of micromotors in vivo for broad applications, particularly, drug delivery.

Drug delivery through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract serves as a convenient and versatile therapeutic tool, owing to its cost-effectiveness, high patient compliance, lenient constraint for sterility, and ease of production (22, 23). Although oral administration of various micro/nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems has been demonstrated to both survive the acidic gastric environment and diffuse into the intestines, drug absorption is still inefficient due to the limited intestinal retention time (24). A large number of passive diffusion-based targeting strategies have been explored to improve the delivery efficiency, but they suffer from low precision, size restraint and specific surface chemistry (25). With precise control, microrobotic drug delivery systems can potentially achieve targeted delivery with long retention times and sustainable release profiles, which are in pressing need (26). Due to the lack of imaging-guided control, there is no report yet for precisely targeted delivery using micromotors in vivo (14). Additionally, biodegradability and biocompatibility are required, and an ideal microrobotic system is expected to be cleared safely by the body after completion of the tasks (5, 27, 28).

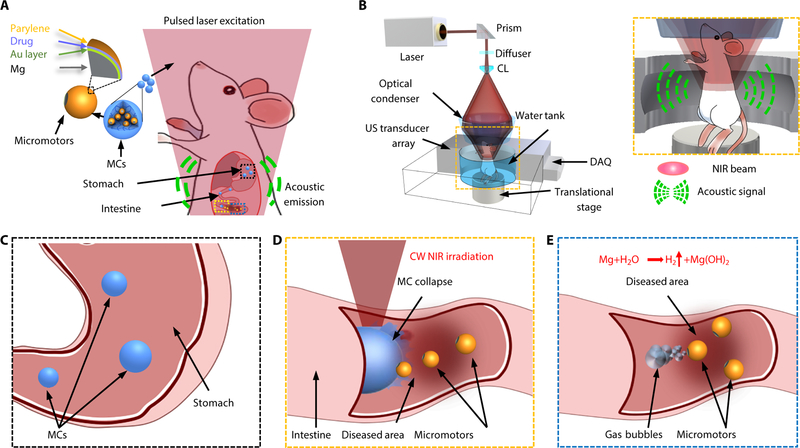

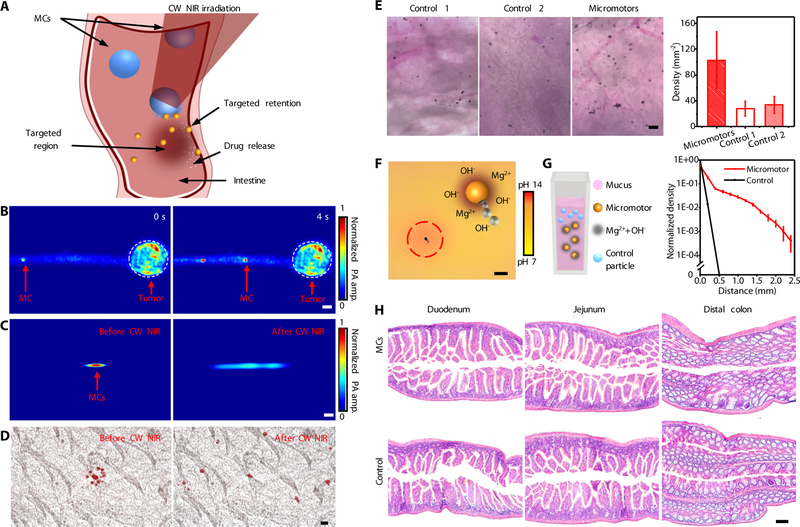

In this paper, we describe a PACT-guided microrobotic system (PAMR), which has accomplished controlled propulsion and prolonged cargo retention in vivo (Fig. 1A and Movie S1). Owing to the high spatiotemporal resolution, non-invasiveness, molecular contrast, and deep penetration, PACT provides an attractive tool to locate and navigate the micromotors in vivo (Fig. 1B) (18–20). Ingestible Mg-based micromotors are encapsulated in enteric protective capsules to prevent reactions in gastric acid and allow direct visualization by PACT (Fig. 1A–C). PACT monitors the migration of micromotor capsules (MCs) in intestines in real time; continuous-wave (CW) near-infrared (NIR) light irradiation induces phase transition of microcapsules and triggers propulsion of the micromotors (Fig. 1D); the autonomous and efficient propulsion of the micromotors enhances the retention in targeted areas of the GI tract (Fig. 1E). We believe that the proposed integrated microrobotic system will substantially advance gastrointestinal therapies.

Fig. 1. Schematic of PAMR in vivo.

(A) Schematic of the PAMR in the GI tract. The MCs are administered into the mouse. NIR illumination facilitates the real-time photoacoustic imaging of the MCs, and subsequently triggers the propulsion of the micromotors in targeted areas of the GI tract. (B) Schematic of PACT of the MCs in the GI tract in vivo. The mouse was kept in the water tank surrounded by an elevationally focused ultrasound transducer array. NIR side-illumination onto the mouse generates PA signals, which are subsequently received by the transducer array. Inset figure: Enlarged view of the cyan dashed box region, illustrating the confocal design of light delivery and PA detection. MC, micromotor capsule; US, ultrasound; CL, conical lens; DAQ, data acquisition system; NIR, near infrared. (C) Enteric coating prevents the decomposition of MCs in the stomach. (D) External continuous-wave (CW) NIR irradiation induces the phase transition and subsequent collapse of the MCs on demand in the targeted areas and activates the movement of the micromotors upon unwrapping from the capsule. (E) Active propulsion of the micromotors promotes the retention and cargo delivery efficiency in intestines.

Results

Fabrication of the micromotor capsules (MCs)

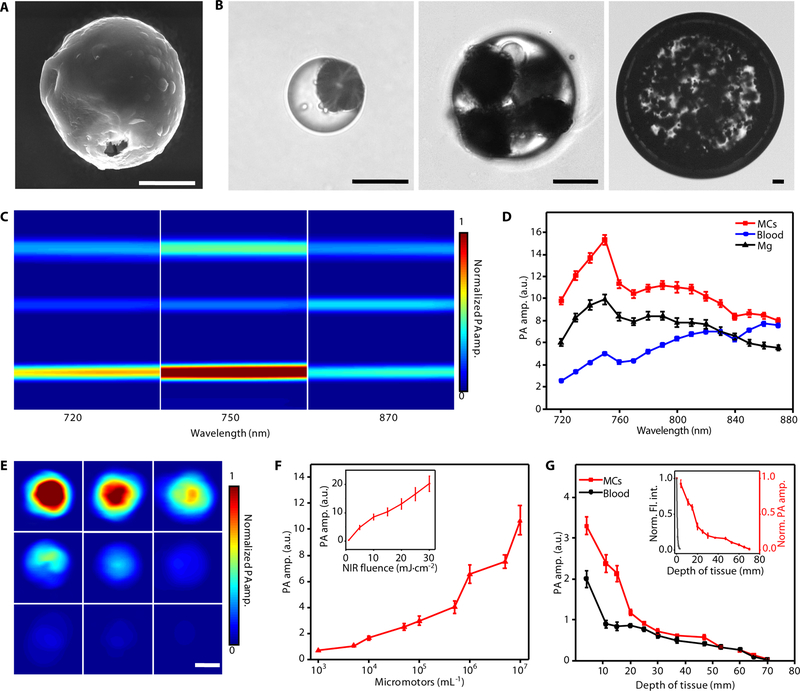

The fabrication of MCs mainly consists of two steps: the fabrication of Mg-based micromotors (fig. S1, Materials and Methods) and the formation of MCs (fig. S2, Materials and Methods). In the first step, Mg microparticles with a diameter of ~20 μm were dispersed onto glass slides, followed by the deposition of a gold layer, which facilitates the autonomous chemical propulsion in GI fluids and enhances PA contrast of the micromotors. An alginate hydrogel layer was coated onto the micromotors by dropping aqueous solution containing alginate and drugs (e.g., doxorubicin) on the slides. A parylene layer, acting as a shell scaffold that ensures the stability during propulsion, was then deposited onto the micromotors. Figure 2A illustrates a fabricated spherical micromotor (~20 μm in diameter). A small opening (~2 μm in diameter), attributed to the surface contact of the Mg microparticles with the glass slides during various layer coating steps, acts as a catalytic interface for gas propulsion in the intestinal environment. Next, the micromotors were encapsulated into the enteric gelatin capsules by the emulsion method (fig. S2). The green fluorescence from the fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled bovine serum albumin (FITC-albumin) and red fluorescence from doxorubicin (DOX) were observed from the micromotors (fig. S3, Materials and Methods) and the MCs (fig. S4, Materials and Methods), confirming a successful drug loading. The size of MCs can be varied by changing the speed of magnetic stirring (fig. S5). The microscopic images in Fig. 2B show three MCs with diameters of 68 μm, 136 μm, and 750 μm.

Fig. 2. Characterization of the MCs.

(A) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of an ingestible micromotor. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Microscopic images of the MCs with different sizes. Scale bars, 50 μm. (C) PACT images of Mg particles, blood, and MCs in silicone rubber tubes with laser wavelengths at 720, 750, and 870 nm, respectively. Scale bar, 500 μm. (D) PACT spectra of MCs (red line), blood (blue line), and Mg particles (black line), respectively. (E and F) PACT images (E) and the corresponding PA amplitude (F) of the MCs with different micromotor loading amounts, and the dependence of the PA amplitude on the fluence of NIR light illumination (inset in F). Scale bar in E, 500 μm. (G) Dependence of PA amplitude of the MCs (red line) and blood (black line) on the depth of tissue, and the normalized PA amplitude and fluorescence intensity of the MCs under tissues (inset). Norm., normalized; amp., amplitude; Fl., fluorescence; int., intensity. Error bars represent the standard deviations from 5 independent measurements.

For deep tissue imaging in vivo, it is crucial that the MCs should have higher optical absorption than the blood background. To evaluate the PA imaging performance of the MCs, the PA amplitudes of the MCs, whole blood, and bare Mg particles were measured (Materials and Methods). NIR light experiences the least attenuation in mammalian tissues, permitting the deepest optical penetration. As shown in Fig. 2C, the MCs exhibit strong PA contrast in the NIR wavelength region, ranging from 720 to 890 nm. In order to assess quantitatively the optical absorption of the MCs, we extracted amplitude values from the above PA images and subsequently calibrated them with optical absorption of hemoglobin (29, 30). At the wavelength of 750 nm, the MCs display the highest PA amplitude of 15.3 (Fig. 2D). The bare Mg particles display a similar PA spectrum, with a lower PA peak with an amplitude of 10.0 at 750 nm. The difference due to the Au layer is expected to significantly improve the imaging sensitivity in the NIR wavelength region (Fig. 2D) (31, 32). In addition, the approximate 3-fold increase in PA amplitudes of the MCs compared to that of the whole blood provides sufficient contrast for PACT to detect the MCs in vivo using 750-nm illumination. To evaluate the stability of the MCs under pulsed NIR PA excitation, we measured the PA signal fluctuation of the MCs during PA imaging (fig. S6). The negligible changes in the PA signal amplitude during the operation suggest a remarkably high photostability of the MCs. Fig. 2E and F show the PA images and the corresponding PA amplitudes of single MCs with different concentrations of micromotors. The dependence of the PA amplitude on the NIR light fluence (i.e., energy per area) was also investigated (Materials and Methods). As expected, the PA amplitude of the micromotors almost linearly increases with the NIR light fluence (Fig. 2F, inset). We also studied the maximum detectable depth of MCs using PACT (Fig. 2G, Materials and Methods). The micromotors showed dramatically decreased fluorescence intensity when covered by thin tissues (0.7–2.4 mm in thickness) and became undetectable quickly (Fig. 2G, inset and fig. S7). By contrast, PACT can image the micromotors inside tissue as deep as ~7 cm (Fig. 2G), which reveals that the key advantage of PACT lies in the high spatial resolution and high molecular contrast for deep imaging in tissues (19).

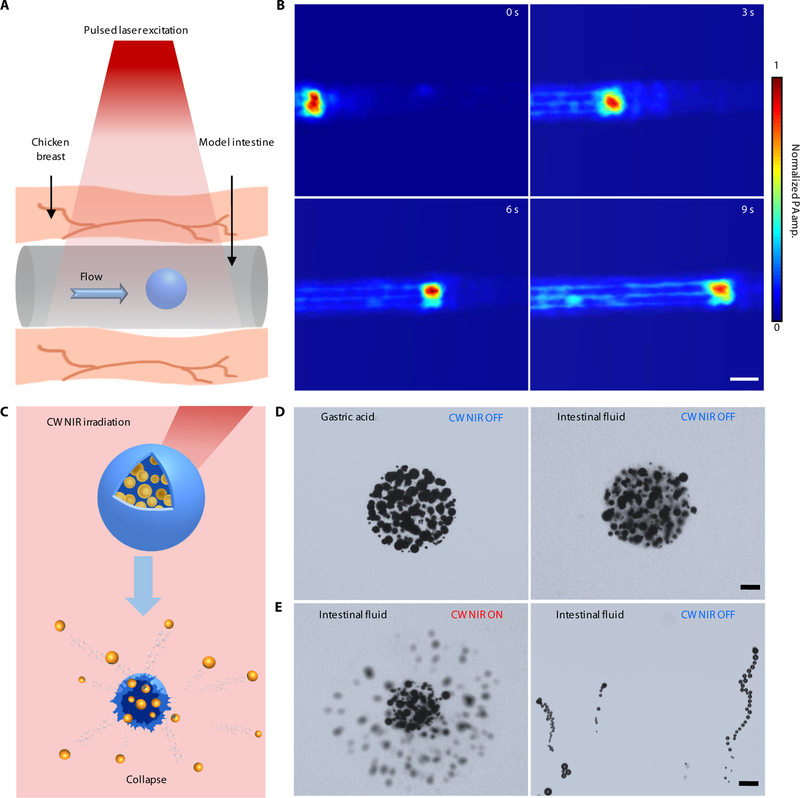

Characterization of the dynamics of the PAMR in vitro

The high optical absorption of the MCs empowers the PAMR as a promising in vivo imaging contrast agent. To evaluate the dynamics of the PAMR, we conducted the PA imaging experiments initially in vitro, where silicone rubber tubes modeled intestines (Materials and Methods). The tubular model intestine was sandwiched in chicken breast tissues (Fig. 3A). The PA time-lapse images in Fig. 3B and Movie S2 illustrate real-time tracking of the migration of an injected MC in the model intestine.

Fig. 3. Characterization of the dynamics of the PAMR.

(A and B) Schematic (A) and time-lapse PACT images in deep tissues (B) illustrating the migration of an MC in the model intestine. Scale bar, 500 μm. The thickness of the tissue above the MC is 10 mm. (C–E) Schematic (C) and time-lapse microscopic images (D and E) showing the stability of the MCs in gastric acid and intestinal fluid (D) without CW NIR irradiation, and the use of CW NIR irradiation to trigger the collapse of an MC and the activation of the micromotors (E). Scale bars in D and E, 50 μm.

In addition to tracking and locating the MCs, propulsion of the micromotors upon unwrapping from the microcapsules can be activated on demand upon high power CW NIR irradiation (Fig. 3C, Materials and Methods). Due to the enteric coating and gelatin encapsulation, the MCs show long-term stability in both gastric acid and intestinal fluid (Fig. 3D and fig. S8). The Au layer of the micromotors can effectively convert NIR light to heat, resulting in a gel-sol phase transition of the gelatin-based capsule followed by the release of the micromotors. Such CW NIR-triggered disintegration of the MCs usually occurs within 0.1 s. Therefore, CW NIR irradiation can activate autonomous propulsion of the micromotors (Fig. 3E and Movie S3). Such a photothermal effect also significantly accelerates the Mg-water chemical reactions and thus enhances the chemical propulsion of the micromotors. As shown in fig. S9 and Movie S4, the micromotors exhibit efficient bubble propulsion in various biofluids. Further quantitative analysis indicates that the velocities of the micromotors are 45 μm s−1 and 43 μm s−1 in PBS solution and the model intestinal fluid, respectively. Note that bare Mg particles have negligible propulsion in neutral media (i.e., intestinal fluid) and disordered propulsion in acidic condition (fig. S10, Materials and Methods). The highly efficient propulsion in the targeted areas in intestines provides a mechanical driving force to enhance retention and delivery. The required NIR power can be potentially adjusted by controlling the synthesis process and composition of the MCs. It is worth mentioning that other triggering mechanisms in biomedicine, such as magnetic or ultrasonic fields, can also be employed to activate propulsion of the micromotors (33).

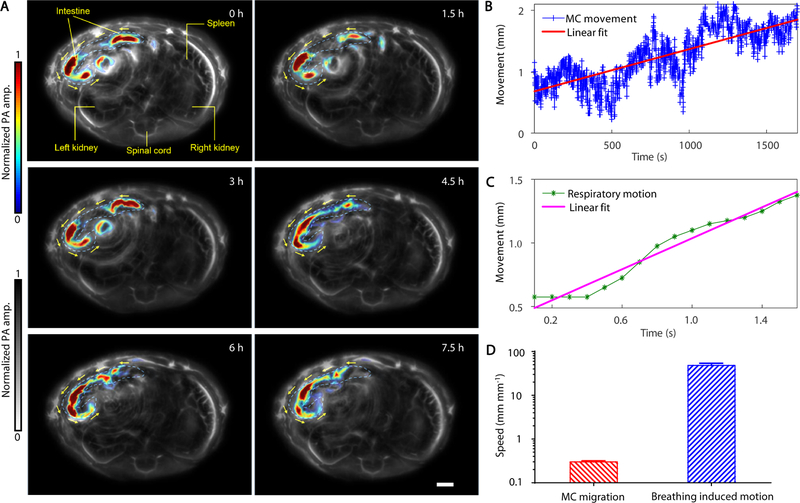

Dynamic imaging of the PAMR in vivo

The movement of a swarm of MCs was monitored in vivo by PACT (Materials and Methods). The MCs were dispersed in pure water and then orally administered into 5–6-week old nude mice. The mice were subsequently anesthetized, and the lower abdominal cavity was aligned with the imaging plane of the ultrasonic transducer array for longitudinal imaging (Fig. 1B). PACT images were captured at a frame rate of 2 Hz for ~8 hours. As shown in Fig. 4A and Movie S5, where the blood vessels and background tissues are shown in gray and MCs in intestines are highlighted in color. During the imaging period of the first 6 hours, the MCs migrated for ~1.2 cm, roughly 15% of the length of the entire small intestine. After 5 hours, the PA signals of some MCs faded away as they moved downstream in intestines that were outside of the imaging plane. The moving speed of the swarm MCs in the intestines and the movements induced by respiratory motion were quantified (Fig. 4B–D, fig. S11). As shown in Fig. 4B–D, the abrupt motion caused by respiration is much faster than actual migration of the MCs. Despite the respiration-induced movement, PACT can distinguish the signals from the slowly migrating MCs in the intestines (Materials and Methods). These results indicate that PACT can precisely monitor and track the locations of the MCs in deep tissues in vivo.

Fig. 4. PACT evaluation of the PAMR dynamics in vivo.

(A) The time-lapse PACT images of the MCs in intestines for 7.5 hours. The MCs migrating in the intestine are shown in color, the mouse tissues are shown in gray. Scale bar, 2 mm. (B and C) The movement displacement caused by the migration of the MCs in the intestine (B) and by the respiration motion of the mouse (C). (D) Comparison of the speeds of the MC migration and the respiration-induced movement.

The evaluation of the PAMR toward targeted retention and delivery

Of particular biomedical significance is the retention of cargo carriers in the targeted region in intestines. While most of the previous studies focused on improving the interactions between particles and the mucoadhesives by engineering surface coatings on the passive particles, the biofluid-driven propulsion of the active micromotors can dramatically prolong their retention in intestine walls. When the MCs approach the targeted areas in intestines, we can trigger the collapse of the capsules and activate the propulsion of micromotors on demand (Fig. 5A, Materials and Methods). To investigate the use of the PAMR for targeted delivery, we grew melanoma cells in mouse intestines and coated the intestines with tissues as a model ex vivo colon tumor. Thanks to the high optical absorption of melanoma cells in the NIR wavelength region, colon tumors can be clearly resolved by PACT. After injection into the intestines, the MCs migrated toward the targeted colon tumor, as illustrated by the time-lapse PACT images in Fig. 5B and Movie S6. Once the MCs approach the targeted location, they are irradiated with CW NIR light to trigger a responsive release of the micromotors. The PA signals from the MCs in the intestines were prolonged upon the CW NIR irradiation, suggesting the release of the micromotors (Fig. 5C). The overlaid microscopic images in Fig. 5D show the NIR-triggered release of the micromotors from an MC in the intestines. The DOX-loaded micromotors, clearly observed with red fluorescence, rapidly diffused into the surrounding area after the CW NIR irradiation (Fig. 5D, Methods).

Fig. 5. Evaluation of the PAMR for targeted retention and delivery.

(A) Schematic of the use of the PAMR for targeted delivery in intestines. (B) The time-lapse PACT images of the migration of an MC toward a model colon tumor. Scale bar, 500 μm. (C and D) PACT images (C) and overlaid time-lapse bright field and fluorescence microscopic images (D) showing the retention of the micromotors in intestines via the NIR-activated propulsion of the micromotors. Scale bars in C and D are 200 μm and 20 μm, respectively. (E) Microscopic images showing the in vivo retention of the control microparticles and the micromotors in intestines (left) and the quantitative analysis of the particle retention in intestines (right). Control 1 and Control 2 represent passive Mg and Au-Mg microparticles, respectively. Scale bar, 100 μm. Error bars represent the standard deviations from 5 independent measurements. (F) Microscopic image displaying the change of pH of the surrounding environment upon the micromotors in PBS. (G) The schematic (left) and the experimental (right) diffusion profiles of the control silica particles and the ingestible micromotors in mucus after 1 hour. Error bars represent the standard deviations from 5 independent measurements. (H) Histology analysis for the duodenum, jejunum, and distal colon of the mice treated with the MCs or DI water as the control for 12 hours. Scale bar, 100 μm.

To evaluate retention of the micromotors in vivo, the enteric polymer-coated micromotors and the paraffin-coated Mg particles (as passive control particles) were orally administrated into two mouse groups that underwent a fasting treatment for 8 hours. The mice were euthanized 12 hours after the administration, and their GI tracts were collected to evaluate the retention of the micromotors (Materials and Methods). The intestines from the mice treated with micromotors retained a much higher number of micromotors than that with passive particles (Fig. 5E, left and middle panels). The quantitative analysis displays a nearly 4-fold increase in the density of the micromotors in the treated intestine segments (Fig. 5E, right panel). Note that nearly all Mg has already degraded in the retained micromotors 12 hours after administration, as illustrated by the hollow structures of the micromotors in the intestine before and after acid treatment (fig. S12). These results confirm the capability of PAMR for prolonged retention in targeted areas in intestines. Besides the active propulsion, the enhanced retention in vivo may also be attributed to the elevated pH and Mg2+ concentration in the surrounding environment caused by Mg-water reactions (Fig. 5F, Methods) (33, 34). It has been recently reported that high pH (~8.2–12.0) could trigger a phase transition of the mucus and facilitate tissue penetration of the micro/nanoparticles (33–36). To investigate the influence of the micromotors on the pH of the surrounding environment, the micromotors were dispersed in water with phenolphthalein as a pH indicator. The microscopic image in Fig. 5F shows red/orange color in the vicinity of a micromotor, indicating an increased pH of the surrounding medium. In addition, an increased concentration of divalent cation Mg2+ can cause collapse of the mucus gel (37). The enhanced diffusion of the micromotors in the mucus was further validated using a previously reported method (38), as shown in Fig. 5G (Materials and Methods). Compared with the negligible diffusion of the control silica particles in the mucus, diffusion of the micromotors in the mucus shows a significantly enhanced profile within 40 minutes. To investigate the cargo release kinetics of the micromotors, a fluorescent anticancer drug, DOX, was encapsulated into the alginate layer of the micromotors (Materials and Methods). The release of DOX from the micromotors was characterized utilizing an ultra-violet/visible spectrophotometer. The cross-linking treatment of the hydrogel significantly improves the efficiency of DOX loading (fig. S13A). By increasing the DOX loading amount from 0.5 to 4 mg, the dose of DOX per micromotor can be controlled from ~1 to 20 ng while the encapsulation efficiency can be improved up to 75.9% (fig. S13B). A higher release rate was observed in the DOX-loaded micromotors in comparison to the DOX-loaded MCs (fig. S14), indicating the promise of using the micromotors for in vivo targeted therapy of GI diseases such as colon cancer.

The biocompatibility and biodegradability of the PAMR are important for biomedical applications. The materials of the MCs, such as Mg, Au, gelatin, alginate, and enteric polymer are known to be biocompatible. To evaluate the toxicity profile of the PAMR in vivo, healthy mice were orally administered with MCs or DI water once a day for two consecutive days. Throughout the treatment, no signs of distress, such as squinting of eyes, hunched posture, or lethargy, were observed in either group. Initially, the toxicity profile of the MCs in mice was evaluated through changes in body weight. During the experimental period, the body weights of the mice administered with MCs have no significant difference from those of the control group (fig. S15, Materials and Methods). The histology analysis was performed to evaluate further the toxicity of the PAMR in vivo. No lymphocytic infiltration into the mucosa or submucosa was observed, indicating no signs of inflammation (Fig. 5H, Materials and Methods).

Discussion

Two key challenges should be addressed for applying synthetic micromotors to practical biomedical applications: 1) advanced imaging techniques to locate micromotors in deep tissue at high spatiotemporal resolution with high contrast; 2) precise on-demand control of micromotors in vivo. With high molecular sensitivity at depths, PACT allows real-time monitoring of micromotors in intestines at high spatial resolution for subsequent control. Here, micromotors with partial coating of functional multilayers are designed as both the imaging contrast agents and the controllable drug carriers. An Au layer is employed to significantly increase the optical absorption for PA imaging and the reaction rate for efficient propulsion simultaneously. A gelatin hydrogel layer is used to enlarge the loading capacity of different functional components, such as therapeutic drugs and imaging agents. A parylene layer is applied to maintain the geometry of the micromotors during propulsion. Our current platform, integrating real-time imaging and control of micromotors in intestines in vivo, leads to the next generation of intelligent microrobotic systems, and provides opportunities for precise microsurgery and targeted drug delivery.

Although the current platform has been demonstrated in small animals, human clinical translations may require tens of centimeters of tissue penetration. PACT can provide up to 7-cm tissue penetration, which is limited by photon dissipation. By employing a more penetrating excitation source—microwave and acoustic detection, thermoacoustic tomography (TAT) promises tissue penetration for clinical translations (39, 40). Moreover, incorporation of a gold layer in the micromotor design provides an excellent microwave absorption contrast for TAT owing to the high electrical conductivity, and thus greatly enhances the deep tissue imaging capability of the microrobots for clinical applications. Focused ultrasound heating can increase the depths of thermally triggered microrobot release to the whole-body level of humans.

Currently, the passive diffusion-based delivery suffers from complex designs, particle size constraints, low precision, and poor specificity. Our platform allows micromotors to reach any targeted regions in intestines with high precision. It can be tailored to particles of any sizes and can be applied to any biological media without additional design efforts. Our platform can also be easily modified to carry various cargos, including therapeutic agents and diagnostic sensors, with real-time feedback during delivery.

Biocompatibility and biodegradability of the micromotors are essential for practical biomedical applications. The components of our micromotors, widely used as therapeutic agents and in implantable devices, are studied to be safe for in vivo applications (41–43). The micromotors have been eventually cleared by the digestive system via excrement, without any adverse effects.

In summary, we report an ingestible microrobotic platform with high optical absorption for imaging-assisted control in intestines. The encapsulated micromotors survive the erosion of the stomach fluid and permit propulsion in intestines. PACT non-invasively monitors the migration of the micromotors and visualizes their arrival at targeted areas in vivo. CW NIR irradiation toward targeted areas induces a phase transition of the capsules and triggers the propulsion of the micromotors. The mechanical propulsion provides a driving force for the micromotors to bind to the intestine walls, resulting in an extended retention. The proposed platform lays a foundation for targeted delivery in tissues and opens a new horizon for precision medicine.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Commercially available magnesium microparticles with a diameter of 20±5 μm were purchased from TangShan WeiHao Magnesium Powder. Agarose, FITC-albumin, alginate, gelatin, and doxorubicin hydrochloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Paraffin liquid, wax, hexane, glutaraldehyde, phenolphthalein, hydrochloric acid, glass coverslip, and gene frame were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Acrylic polymers (Eudragit L 100–55) were purchased from Evonik Industries. Silicone rubber tubes (inner diameter: 0.5 mm) were purchased from Dow Silicones.

Fabrication of the micromotors

The Mg-based Janus micromotors were constructed with an embedding method (fig. S1). The Au, alginate, and parylene were deposited in a layer-by-layer manner. Mg particles were first washed with acetone for three times and dried at room temperature prior to use. Mg particles were dispersed in acetone with a particle concentration of ~0.1 g mL−1 and then spread on the glass slides at room temperature. After the acetone evaporated, Mg particles were attached onto the surface of the glass slides through physical adsorption, exposing the majority of the surface areas of the particles to air. Subsequently, the glass slides coated with Mg particles were deposited with a Au layer (~100 nm in thickness) using an electron-beam evaporator (Mark 40, CHA Industries). After the deposition, a mixture containing alginate (2%, w/v) and doxorubicin was dropped on the glass slides and then dried with N2 gas. Aqueous CaCl2 (0.2 mL of 5%, w/v) was then dropped onto the glass slides to cross-link alginate. After 30 minutes, the glass slides were washed with pure water and dried with N2 gas. The glass slides were coated with a parylene C layer (750 nm in thickness) using a parylene coater (Labtop 3000, Curtiss-Wright). The resulted micromotors were collected by scratching from the glass slides.

Preparation of the MCs

MCs were fabricated based on a controlled emulsion technique according to the previous reports (fig. S2) (44, 45). A mixture containing gelatin (5%, w/v) and micromotors (5%, w/v) at 40–60 °C was extruded from a 30-gauge needle into 50 mL liquid paraffin at ~60 °C. Pure water was used as the solvent here, in which micromotors remained stable due to the formation of a compact hydroxide passivation layer on the Mg surfaces. Subsequently, an enteric polymer solution consisting of 100 mg of Eudragit L-100 in 2 mL organic solvent mixture (acetone:methanol = 1:1, v/v) as previously reported (46), was extruded into the liquid paraffin. The extruded solution was kept at 60 °C for 4 hours to evaporate the acetone and methanol, and then the temperature was lowered to 0 °C with an ice bath. In order to harvest the MCs from the liquid paraffin, cold water (~4 °C) was added into the liquid paraffin with magnetic stirring for more than 20 minutes, and most MCs were separated from the liquid paraffin into the water. The water containing MCs was extracted and then washed with hexane for three times. The size of the MCs can be controlled by varying the rotational speed of magnetic stirring between 100 and 1000 rpm (fig. S5). The collected MCs were rinsed with an aqueous hydrochloric acid solution (pH = 2) and then washed with pure water to remove the hydrochloric acid. Subsequently, the MCs were cross-linked through incubation with glutaraldehyde for 1 hour followed by water rinse.

Characterization of the structures of the micromotors and the MCs

SEM images of the Mg-based micromotors were acquired with a field emission scanning electron microscope (FEI Sirion) at an operating voltage of 10 keV (Fig. 2A). The samples were coated with a 5-nm carbon layer to improve the conductivity (Leica EM ACE600 Carbon Evaporator). The bright field and fluorescence microscopic images of the micromotors and the MCs were taken with a Zeiss AXIO optical microscope (Fig. 2B, figs. S3 and S4). To observe the structure of the DOX-loaded micromotors and MCs using fluorescence imaging, the micromotors and the MCs were stained with FITC-albumin. Labeling of FITC-albumin onto the micromotors was carried out by dip-coating the micromotors-loaded glass slides in a 0.2 mL of FITC-albumin solution (0.2 mg mL−1), followed by dip-coating in an alginate solution (2%, w/v). Labeling of the FITC-albumin onto the MCs was conducted by adding FITC-albumin into the gelation solution.

Characterization of the PA performances of the MCs

Characterization of the PA performances of the MCs was conducted using a PACT system (19). The MCs, bare Mg microparticles, and blood were separately injected into three silicone tubes. Both ends of the tubes were sealed with agarose gel (2%, w/v). the PACT system employed a 512-element full-ring ultrasonic transducer array (Imasonic SAS; 50 mm ring radius; 5.5 MHz central frequency; more than 90% one-way bandwidth) for 2D panoramic acoustic detection. Each element has a cylindrical focus (0.2 NA; 20 mm element elevation size; 0.61 mm pitch; 0.1 mm inter-element spacing). A lab-made 512-channel preamplifier (26 dB gain) was directly connected to the ultrasonic transducer array housing, minimizing cable noise. The pre-amplified PA signals were digitized using a 512-channel data acquisition system (four SonixDAQs, Ultrasonix Medical ULC; 128 channels each; 40 MHz sampling rate; 12-bit dynamic range) with programmable gain up to 51 dB. The digitized radio frequency data were first stored in the onboard buffer, then transferred to a computer and reconstructed using the dual-speed-of-sound half-time universal back-projection algorithm (Fig. 2C–G, figs. S6 and S7) (19).

PACT of the migration of the MCs

PACT of the migration of the MCs in model intestines was carried out by injecting the MCs into a silicone tube, which was covered by chicken breast tissues. Migration of the MCs in the tube was driven by microfluidic pumping and was captured by PACT (Fig. 3B, Movie S2).

For in vivo experiments, all experimental procedures were conducted under a laboratory animal protocol approved by the Office of Laboratory Animal Resources at California Institute of Technology. Three- to four-week-old nude mice (Hsd: Athymic Nude-FoxlNU, Harlan Co.; 20–25-g body weight) were used for in vivo imaging. Prior to the imaging experiments, the mice were fasted for ~8 hours followed by the oral administration with the MCs. The mouse was then fixed to a lab-made imaging platform by taping the fore and hind legs on the top and bottom parts of the holder in the PACT system. During imaging, the mice were under anesthesia with 1.5% vaporized isoflurane. The administrated mice were imaged continuously for ~8 hours to monitor the MC migration process (Fig. 4 and Movie S5).

To study the migration of the MCs toward the targeted diseased areas, melanoma cells as the model tumor were cultivated and the cells were injected into intestines. A silicone tube filled with the MCs was connected to the intestine and was sealed with agarose. A syringe pump (Fisher Scientific 78–01001) was also connected with the tube to drive the MCs into intestines. The migration process was captured by PACT (Fig. 5B and Movie S6).

Quantify speeds of MC migration

The acquired frames containing MC migration were first averaged to project the trajectories of the MCs. The migration paths of MCs were manually identified from the averaged image. Time traces at points along the migration paths were then extracted, forming images in which one dimension was the distance along the migration paths (x) and the other dimension was the elapsed time (t). Median filter (3×3 pixels) was then used to smooth the x-t images. Applying a threshold (1/3 of the maximum) segmented out the pixels containing MCs. The center positions of MCs along the path were estimated by calculating the geometric centers of the segmented pixels for given times. The center positions at the elapsed time points were fitted linearly to compute the migration speeds.

Highlight MCs using temporal frequency filtering

The frames of interest were firstly smoothed by a Gaussian filter (δ = 3 pixels). Then Fourier transformation with respect to time was applied to all frames. An empirical band-pass filter was used to eliminate signals from either the static background or the respiration motion affected pixels, and thus the slowly moving pixels containing MCs were highlighted.

CW NIR-activated propulsion of the micromotors

PBS solution of 30 μL mixed with MCs was dropped on a piece of gene frame. A glass coverslip was then carefully placed over the gene frame. A CW NIR laser (808 nm, 2 W) was used to irradiate the micromotors obliquely with the light beam aligned to the focus of the microscope. The focal diameter of the beam was ~0.8 cm. Once the position of the laser spot on the glass slide was marked, the NIR laser was turned off and the MCs were moved to the marked spot. The MCs were irradiated before they completely sank to the bottom of the glass slide. The disintegration of the MCs occurred within 0.1 s exposure of the CW NIR light. In addition, during each respiration cycle, the resting time (the duration free of respiration motion) is typically longer than 0.3 s (19). Thus, once the real-time PACT detects that MCs have reached the targeted area, the CW NIR light can trigger the release during the resting time, avoiding the influence of respiration motion. The process of the NIR-triggered disintegration of the MCs and the propulsion of the micromotors were captured using a high-speed camera (Axiocam 720 mono) at 100 and 25 frames s−1, respectively (Movie S3). ImageJ with the plugin Manual Tracking was used to track the micromotors (Fig. 3D and E).

Characterization of the propulsion of the micromotors

To simulate the gastric and intestinal environments, 0.01 M HCl (pH = 2) was prepared as the model gastric fluid, and 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH = 6.5) was prepared as the model intestinal fluid. To characterize the movement of the micromotors, ~10 μL of model fluid with 1% Triton X-100 were placed on a glass slide. Then, a ~2 μL aqueous micromotor suspension in water was added into the model solution on the glass slide. The movement of micromotors was captured using a high-speed camera (Axiocam 720 mono) at ~25 frames s−1 (figs. S10 and S11, Movie S4). ImageJ with the plugin Manual Tracking was employed to track the micromotors. At least 20 micromotors were tracked to calculate the average speeds and the standard deviations.

To investigate the pH change of the surrounding environment upon micromotor propulsion, 5 μL phenolphthalein (0.5% in alcohol, w/v) was added into 1 mL PBS solution (pH = 6.5) as an indicator. An optical microscope (Zeiss AXIO) was used to capture the movie in color mode (Fig. 5F).

Retention of the micromotors in vivo

Mice underwent a fasting treatment for ~8 hours before the retention investigation. 0.1 mL suspension containing the enteric polymer-coated micromotors (~106 mL−1 in water) was orally administered into the mice. During the experiment, water feeding was maintained. As the controls, wax-coated passive Mg particles and wax-coated passive Mg/Au particles were prepared by incubating 0.05 g Mg particles or Mg/Au particles with 1 g paraffin wax at 75 °C overnight and then sequentially washed with chloroform, acetone, and pure water (47). Then, the control sample was orally administered. After 12 hours, both groups of mice were sacrificed, and the intestines were collected. Retention of micromotors was observed utilizing a Zeiss AXIO optical microscope at 5× magnification. The retained micromotors and control particles were counted using ImageJ (Fig. 5E). Dissolution of Mg after administration was characterized by optical imaging before and after acid treatment (fig. S12).

Diffusion of the micromotors in mucus

Diffusion of micromotors in mucus were investigated following a reported method (38). A cuvette was filled with 3.5 mL porcine mucus, and then a 100 μL micromotors suspension (~106 mL−1 in water) was pipetted into the mucus. Silica microparticles of the same size were utilized as control. Optical images were captured every 2 minutes. During the observation, the cuvettes were treated with sonication for 5 seconds with an ultrasound bath cleaner to remove bubbles. ImageJ was employed to count particles in the mucus (Fig. 5F and G). The numbers were normalized by the number of particles injected at the start, and the ratios were calculated at distances away from the initial point.

Encapsulation and release of DOX from the micromotors

The encapsulation efficiency (EE) and release profile of DOX on the MCs and micromotors were elevated using previous methods (48, 49). To encapsulate DOX into the micromotors, 1.0 mL alginate solution (2%, w/v) with different concentrations of DOX were dropped onto the glass slides containing Au layer-coated Mg microparticles, and then a 1.0 mL CaCl2 solution was dropped onto the glass slide to cross-link alginate, followed by coating of a parylene layer and water rinse for 3 times. Micromotors without cross-linking were also prepared. The amount of DOX was measured through a UV-visible spectrophotometer at 485 nm (fig. S13). The EE of DOX on the micromotors were determined using the following equation:

| (1) |

For the drug release study, ~10 mg DOX-loaded micromotors were suspended in 5 mL PBS with magnetic stirring at 37 °C and 8000 rpm. At different time intervals, the supernatant was removed and replaced with fresh PBS. The concentration of DOX was determined by measuring its absorbance using a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 485 nm (fig. S14).

Toxicity estimation of the micromotors

To estimate the toxicity of the MCs in vivo, 5–6-week old nude mice (Hsd: Athymic Nude-FoxlNU, Harlan Co.; 20–30-g body weight) were administered with 0.1 mL micromotor suspension via oral gavage. Healthy mice treated with DI water were used as a negative control. The body weight of mice was measured daily during the experiment (fig. S15). Mice were sacrificed, and the intestines were collected for histological characterization 6 days after administration. In order to prepare the intestine sample for histology investigation, the intestines were treated with 10% (v/v) buffered formalin for 15 hours. The intestines were cut to smaller sections as duodenum, jejunum, and distal colon. The longitudinal tissue sections were washed in tissue cassettes and embedded in paraffin. The tissue sections were sliced into 8-μm thick sections using a freezing microtome (Leica, CM1950) and stained with H&E assay. The samples were imaged with an optical microscope (Zeiss, AXIO) (Fig. 5H).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Materials

Materials and Methods

Text S1. Small-animal whole-body imaging modalities and photoacoustic computed tomography.

Fig. S1. The fabrication flow of the ingestible micromotors.

Fig. S2. The preparation of the MCs.

Fig. S3. Bright field and fluorescence microscopic images of the micromotors confirming the successful drug loading in micromotors.

Fig. S4. Bright field and fluorescence microscopic images of the MCs confirming the successful drug loading in the MCs.

Fig. S5. Dependence of the size of the MCs on the rotation speed of magnetic stirring.

Fig. S6. Long-term stability of the PA signals of the MCs under the NIR illumination used in the PACT in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. S7. Fluorescence imaging of the MCs in a silicone tube under tissues with different depths.

Fig. S8. Long-term structure stability of the MCs in the gastric fluid and the intestinal fluid.

Fig. S9. Velocities of Mg-based micromotors in the different media.

Fig. S10. Velocities of bare Mg microparticles in the different media.

Fig. S11. Quantification of MC migration speeds.

Fig. S12. Characterization of Mg dissolution in micromotors 12 hours after administration.

Fig. S13. Effects of cross-linking and DOX loading amount on the encapsulation efficiency of the micromotors and dose per micromotor.

Fig. S14. Profile of DOX release from MCs and micromotors as a function of time.

Fig. S15. The weight changes of the mice after the oral administration of the MCs and the control (DI water).

Movie S1. Animated illustration of the PAMR in vivo.

Movie S2. Photoacoustic imaging the migration of an MC in model intestines. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Movie S3. NIR-triggered destruction of the MC and activated autonomous propulsion of the ingestible micromotors. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Movie S4. Propulsion of the micromotors in biofluids. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Movie S5. Photoacoustic imaging of the MCs in vivo for 7.5 hours. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Movie S6. Photoacoustic imaging of the migration of an MC toward a model colon tumor in intestines. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Acknowledgments:

Funding: This work was sponsored by the Startup funds from California Institute of Technology (to W.G.) and the NIH grants EB016986 (NIH Director’s Pioneer Award), CA186567 (NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award), NS090579, and NS099717 (all to L.V.W.). We gratefully acknowledge critical support and infrastructure provided for this work by the Kavli Nanoscience Institute at Caltech.

References and Notes

- 1.Li J, Esteban-Fernández de Ávila B, Gao W, Zhang L, Wang J, Micro/nanorobots for biomedicine: Delivery, surgery, sensing, and detoxification. Sci. Robot 2, eaam6431 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paxton WF, Kistler KC, Olmeda CC, Sen A, St. Angelo SK, Cao Y, Mallouk TE, Lammert PE, Crespi VH, Catalytic nanomotors: Autonomous movement of striped nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc 126, 13424–13431 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu W, Lum GZ, Mastrangeli M, Sitti M, Small-scale soft-bodied robot with multimodal locomotion. Nature 554, 81–85 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan D, Yin Z, Cheong R, Zhu FQ, Cammarata RC, Chien CL, Levchenko A, Subcellular-resolution delivery of a cytokine through precisely manipulated nanowires. Nat. Nanotechnol 5, 545–551 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan X, Zhou Q, Vincent M, Deng Y, Yu J, Xu J, Xu T, Tang T, Bian L, Wang Y-XJ, Kostarelos K, Zhang L, Multifunctional biohybrid magnetite microrobots for imaging-guided therapy. Sci. Robot 2, eaaq1155 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu C, Pané S, Nelson BJ, Soft micro- and nanorobotics. Annu. Rev. Control. Robot. Auton. Syst 1, 53–75 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sánchez S, Soler L, Katuri J, Chemically powered micro- and nanomotors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 54, 1414–1444 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu Y, Peng F, Sui X, Men Y, White PB, van Hest JCM, Wilson DA, Self-propelled supramolecular nanomotors with temperature-responsive speed regulation. Nat. Chem 9, 480 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esteban-Fernández de Ávila B, Angsantikul P, Li J, Lopez-Ramirez MA, Ramírez-Herrera DE, Thamphiwatana S, Chen C, Delezuk J, Samakapiruk R, Ramez V, Zhang L, Wang J, Micromotor-enabled active drug delivery for in vivo treatment of stomach infection. Nat. Commun 8, 272 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Gao W, Nano/microscale motors: biomedical opportunities and challenges. ACS Nano 6, 5745–5751 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao W, Dong R, Thamphiwatana S, Li J, Gao W, Zhang L, Wang J, Artificial micromotors in the mouse’s stomach: A step toward in vivo use of synthetic motors. ACS Nano 9, 117–123 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li T, Chang X, Wu Z, Li J, Shao G, Deng X, Qiu J, Guo B, Zhang G, He Q, Li L, Wang J, Autonomous collision-free navigation of microvehicles in complex and dynamically changing environments. ACS Nano 11, 9268–9275 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sitti M, Miniature soft robots-road to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Mater 3, 74–75 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medina-Sánchez MS, Schmidt OG, Medical microbots need better imaging and control. Nature 545, 406–408 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vilela D, Cossío U, Parmar J, Martínez‐Villacorta AM, Gómez‐Vallejo V, Llop J, Sánchez S, Medical imaging for the tracking of micromotors. ACS Nano 12, 1220–1227 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ntziachristos V, Going deeper than microscopy: the optical imaging frontier in biology. Nat. Methods 7, 603–614 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Razansky D, Distel M, Vinegoni C, Ma R, Perrimon N, Koster RW, Ntziachristos V, Multispectral opto-acoustic tomography of deep-seated fluorescent proteins in vivo. Nat. Photonics 3, 412–417 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang LV, Hu S, Photoacoustic tomography: in vivo imaging from organelles to organs. Science 335, 1458–1462 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Zhu L, Ma C, Lin L, Yao J, Wang L, Maslov K, Zhang R, Chen W, Shi J, Single-impulse panoramic photoacoustic computed tomography of small-animal whole-body dynamics at high spatiotemporal resolution. Nat. Biomed. Eng 1, 0071 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li L, Shemetov AA, Baloban M, Hu P, Zhu L, Shcherbakova DM, Zhang R, Shi J, Yao J, Wang LV, Verkhusha VV, Small near-infrared photochromic protein for photoacoustic multi-contrast imaging and detection of protein interactions in vivo. Nat. Commun 9, 2734 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao J, Kaberniuk AA, Li L, Shcherbakova DM, Zhang R, Wang L, Li G, Verkhusha VV, Wang LV, Multiscale photoacoustic tomography using reversibly switchable bacterial phytochrome as a near-infrared photochromic probe. Nat. Methods 13, 67 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellinger A, Jafari M, Grant TM, Zhang S, Slater HC, Wenger EA, Mo S, Lee YL, Mazdiyasni H, Kogan L, Barman R, Cleveland C, Booth L, Bensel T, Minahan D, Hurowitz HM, Tai T, Daily J, Nikolic B, Wood L, Eckhoff PA, Langer R, Traverso G, Oral, ultra–long-lasting drug delivery: application toward malaria elimination goals. Sci. Transl. Med 8, 365ra157 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koziolek M, Grimm M, Schneider F, Jedamzik P, Sager M, Kühn J-P, Siegmund W, Weitschies W, Navigating the human gastrointestinal tract for oral drug delivery: Uncharted waters and new frontiers. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 101, 75–88 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soppimath KS, Kulkarni AR, Rudzinski WE, Aminabhavi TM, Microspheres as floating drug-delivery systems to increase gastric retention of drugs. Drug Metab. Rev 33, 149–160 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenblum D, Joshi N, Tao W, Karp JM, Peer D, Progress and challenges towards targeted delivery of cancer therapeutics. Nat. Commun 9, 1410 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang G-Z, Bellingham J, Dupont PE, Fischer P, Floridi L, Full R, Jacobstein N, Kumar V, McNutt M, Merrifield R, Nelson BJ, Scassellati B, Taddeo M, Taylor R, Veloso M, Wang ZL, Wood R, The grand challenges of science robotics. Sci. Robot 3, eaar7650 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdelmohsen LKEA, Peng F, Tu Y, Wilson DA, Micro- and nano-motors for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2, 2395–2408 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H, Pumera M, Fabrication of micro/nanoscale motors. Chem. Rev 115, 8704–8735 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de la Zerda A, Zavaleta C, Keren S, Vaithilingam S, Bodapati S, Liu Z, Levi J, Smith BR, Ma TJ, Oralkan O, Cheng Z, Chen X, Dai H, Yakub BTK, Gambhir SS, Family of enhanced photoacoustic imaging agents for high-sensitivity and multiplexing studies in living mice. ACS Nano 6, 4694–4701 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eghtedari M, Oraevsky A, Copland JA, Kotov NA, Conjusteau A, Motamedi M, High sensitivity of in vivo detection of gold nanorods using a laser optoacoustic imaging system. Nano Lett. 7, 1914–1918 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo W, Guo C, Zheng N, Sun T, Liu S, CsxWO3 nanorods coated with polyelectrolyte multilayers as a multifunctional nanomaterial for bimodal imaging-guided photothermal/photodynamic cancer treatment. Adv. Mater 29, 1604157 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ji T, Lirtsman VG, Avny Y, Davidov D, Preparation, characterization, and application of Au-shell/polystyrene beads and Au-shell/magnetic beads. Adv. Mater 13, 1253–1256 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tay ZW, Chandrasekharan P, Chiu-Lam A, Hensley DW, Dhavalikar R, Zhou XY, Yu EY, Goodwill PW, Zheng B, Rinaldi C, Conolly SM, Magnetic particle imaging-guided heating in vivo using gradient fields for arbitrary localization of magnetic hyperthermia therapy. ACS Nano 12, 3699–3713 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bansil R, Turner BS, The biology of mucus: Composition, synthesis and organization. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 124, 3–15 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Celli JP, Turner BS, Afdhal NH, Keates S, Ghiran I, Kelly CP, Ewoldt RH, McKinley GH, So P, Erramilli S, Bansil R, Helicobacter pylori moves through mucus by reducing mucin viscoelasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 14321–14326 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai SK, Wang Y-Y, Hanes J, Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to mucosal tissues. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 61, 158–171 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leal J, Smyth HDC, Ghosh D, Physicochemical properties of mucus and their impact on transmucosal drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm 532, 555–572 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirch J, Schneider A, Abou B, Hopf A, Schaefer UF, Schneider M, Schall C, Wagner C, Lehr C-M, Optical tweezers reveal relationship between microstructure and nanoparticle penetration of pulmonary mucus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 18355–18360 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu Y, Wang LV, Rhesus monkey brain imaging through intact skull with thermoacoustic tomography. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 53, 542–548 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kruger RA, Kiser WL, Miller KD, Reynolds HE, Rienecke DR, Kruger GA, Hofacker PJ, Thermoacoustic CT: imaging principles. Proc. SPIE 3916, 150–160 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith BR, Eastman CM, Njardarson JT, Beyond C, H, O, and Ni analysis of the elemental composition of U.S. FDA approved drug architectures. J. Med. Chem 57, 9764–9773 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baheiraei N, Azami M, Hosseinkhani H, Investigation of magnesium incorporation within gelatin/calcium phosphate nanocomposite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol 12, 245–253 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sezer N, Evis Z, Kayhan SM, Tahmasebifar A, Koç M, Review of magnesium-based biomaterials and their applications. J. Magnesium Alloys 6, 23–43 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yin N, Stilwell MD, Santos TMA, Wang H, Weibel DB, Agarose particle-templated porous bacterial cellulose and its application in cartilage growth in vitro. Acta Biomater. 12, 129–138 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Thamphiwatana S, Liu W, Esteban-Fernández de Ávila B, Angsantikul P, Sandraz E, Wang J, Xu T, Soto F, Ramez V, Wang X, Gao W, Zhang L, Wang J, Enteric micromotor can selectively position and spontaneously propel in the gastrointestinal tract. ACS Nano 10, 9536–9542 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chourasia MK, Jain SK, Design and development of multiparticulate system for targeted drug delivery to colon. Drug Deliv. 11, 201–207 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hong L, Jiang S, Granick S, Simple method to produce Janus colloidal particles in large quantity. Langmuir 22, 9495–9499 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cui Y, Xu Q, Chow PK-H, Wang D, Wang C-H, Transferrin-conjugated magnetic silica PLGA nanoparticles loaded with doxorubicin and paclitaxel for brain glioma treatment. Biomaterials 34, 8511–8520 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gaihre B, Khil MS, Lee DR, Kim HY, Gelatin-coated magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as carrier system: Drug loading and in vitro drug release study. Int. J. Pharm 365, 180–189 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials

Materials and Methods

Text S1. Small-animal whole-body imaging modalities and photoacoustic computed tomography.

Fig. S1. The fabrication flow of the ingestible micromotors.

Fig. S2. The preparation of the MCs.

Fig. S3. Bright field and fluorescence microscopic images of the micromotors confirming the successful drug loading in micromotors.

Fig. S4. Bright field and fluorescence microscopic images of the MCs confirming the successful drug loading in the MCs.

Fig. S5. Dependence of the size of the MCs on the rotation speed of magnetic stirring.

Fig. S6. Long-term stability of the PA signals of the MCs under the NIR illumination used in the PACT in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. S7. Fluorescence imaging of the MCs in a silicone tube under tissues with different depths.

Fig. S8. Long-term structure stability of the MCs in the gastric fluid and the intestinal fluid.

Fig. S9. Velocities of Mg-based micromotors in the different media.

Fig. S10. Velocities of bare Mg microparticles in the different media.

Fig. S11. Quantification of MC migration speeds.

Fig. S12. Characterization of Mg dissolution in micromotors 12 hours after administration.

Fig. S13. Effects of cross-linking and DOX loading amount on the encapsulation efficiency of the micromotors and dose per micromotor.

Fig. S14. Profile of DOX release from MCs and micromotors as a function of time.

Fig. S15. The weight changes of the mice after the oral administration of the MCs and the control (DI water).

Movie S1. Animated illustration of the PAMR in vivo.

Movie S2. Photoacoustic imaging the migration of an MC in model intestines. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Movie S3. NIR-triggered destruction of the MC and activated autonomous propulsion of the ingestible micromotors. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Movie S4. Propulsion of the micromotors in biofluids. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Movie S5. Photoacoustic imaging of the MCs in vivo for 7.5 hours. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Movie S6. Photoacoustic imaging of the migration of an MC toward a model colon tumor in intestines. Scale bar, 200 μm.