Abstract

Objective

To examine the associations between the intake of total and individual whole grain foods and the risk of type 2 diabetes.

Design

Prospective cohort studies.

Setting

Nurses’ Health Study (1984-2014), Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2017), and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (1986-2016), United States.

Participants

158 259 women and 36 525 men who did not have type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or cancer at baseline.

Main outcome measures

Self-reports of incident type 2 diabetes by participants identified through follow-up questionnaires and confirmed by a validated supplementary questionnaire.

Results

During 4 618 796 person years of follow-up, 18 629 participants with type 2 diabetes were identified. Total whole grain consumption was categorized into five equal groups of servings a day for the three cohorts. After adjusting for lifestyle and dietary risk factors for diabetes, participants in the highest category for total whole grain consumption had a 29% (95% confidence interval 26% to 33%) lower rate of type 2 diabetes compared with those in the lowest category. For individual whole grain foods, pooled hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for type 2 diabetes in participants consuming one or more servings a day compared with those consuming less than one serving a month were 0.81 (0.77 to 0.86) for whole grain cold breakfast cereal, 0.79 (0.75 to 0.83) for dark bread, and 1.08 (1.00 to 1.17) for popcorn. For other individual whole grains with lower average intake levels, comparing consumption of two or more servings a week with less than one serving a month, the pooled hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) were 0.79 (0.75 to 0.83) for oatmeal, 0.88 (0.82 to 0.94) for brown rice, 0.85 (0.80 to 0.90) for added bran, and 0.88 (0.78 to 0.98) for wheat germ. Spline regression showed a non-linear dose-response association between total whole grain intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes where the rate reduction slightly plateaued at more than two servings a day (P<0.001 for curvature). For whole grain cold breakfast cereal and dark bread, the rate reduction plateaued at about 0.5 servings a day. For consumption of popcorn, a J shaped association was found where the rate of type 2 diabetes was not significantly raised until consumption exceeded about one serving a day. The association between higher total whole grain intake and lower risk of type 2 diabetes was stronger in individuals who were lean than in those who were overweight or obese (P=0.003 for interaction), and the associations did not vary significantly across levels of physical activity, family history of diabetes, or smoking status.

Conclusion

Higher consumption of total whole grains and several commonly eaten whole grain foods, including whole grain breakfast cereal, oatmeal, dark bread, brown rice, added bran, and wheat germ, was significantly associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes. These findings provide further support for the current recommendations of increasing whole grain consumption as part of a healthy diet for the prevention of type 2 diabetes.

Introduction

Whole grains have been widely recognized as healthy foods because of their high content of fiber, antioxidants, and phytochemicals.1 Human trials have shown the potential of a diet enriched with whole grains in reducing fat mass, increasing resting metabolic rate, promoting negative energy balance, increasing insulin sensitivity, improving the lipid profile, and reducing systemic inflammation.2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Epidemiological studies have shown inverse associations between consumption of whole grains and the risk of developing several major chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and some types of cancer.10 11 12 Most of these observational studies so far have characterized intake of whole grains as the sum of whole grain ingredients from all grain containing foods, which might contain various amounts of whole grains and refined grains.13 Despite a similar proportion of bran and germ (about 13% and 2%, respectively),14 individual whole grain foods usually contain various amounts of dietary fiber, antioxidants, magnesium, and phytochemicals,15 16 17 which might result in differential effects of different types of whole grain foods on cardiometabolic health. Several prospective cohort studies have shown favorable associations between certain whole grain foods, such as whole grain breakfast cereal and brown rice, on the risk of type 2 diabetes,18 19 20 although associations for other whole grain foods have not been established.

To provide evidence to bridge this knowledge gap, in this study, we prospectively examined the associations between the consumption of several commonly eaten whole grain foods, such as whole grain cold breakfast cereal, oatmeal, dark bread, brown rice, popcorn, wheat germ, and added bran, and the risk of type 2 diabetes, in the Nurses’ Health Study, the Nurses’ Health Study II, and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, three large, well characterized cohort studies with diet and other characteristics repeatedly assessed over three decades of follow-up.

Methods

Study population

The Nurses’ Health Study cohort was established in 1976 when 121 700 registered nurses, all women, aged 30-55, completed a questionnaire on their medical history and lifestyle characteristics. The Nurses’ Health Study II was initiated in 1989 and included 116 340 eligible women aged 25-42. A questionnaire similar to that used in the Nurses’ Health Study was administered at baseline to assess medical history, lifestyle factors, and diet. The Health Professionals Follow-up Study began in 1986 when 51 529 American health professionals, all men, aged 40-75, answered a similar baseline questionnaire. In all three cohorts, similar follow-up questionnaires were sent to the participants to update the information and to identify newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes and other diseases every two years. The cumulative response rates in the three cohorts exceeded 90%.21 22

Here, the study baseline was set at 1984, 1991, and 1986 for the Nurses’ Health Study, Nurses’ Health Study II, and Health Professionals Follow-up Study, respectively. We excluded participants diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (including non-fatal myocardial infarction, fatal coronary heart disease, and fatal and non-fatal stroke), or cancer at baseline, those who did not return a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire or had an unusual total energy intake at baseline (<500 or >3500 kcal/day for the Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II, and <800 or >4200 kcal/day for the Health Professionals Follow-up Study; 1 kcal=4.18 kJ=0.00418 MJ), those with unconfirmed type 2 diabetes, and those who completed only the baseline questionnaire. After these exclusions, 69 139 participants from the Nurses’ Health Study, 89 120 participants from the Nurses’ Health Study II, and 36 525 participants from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study were included in the final analysis. The study protocol was approved by the human research committee of Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. Completion and return of study questionnaires implied informed consent of the participants.

Assessment of individual whole grain food consumption

In 1984, a 116 item semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire was given to participants in the Nurses’ Health Study to collect information on their usual diet in the previous year. The dietary information was updated in 1986 and every four years thereafter with similar but expanded questionnaires. In the Nurses’ Health Study II and Health Professionals Follow-up Study, the same semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire was used to collect and update dietary information every four years, from 1991 and 1986, respectively. In the semiquantitative food frequency questionnaires, participants were asked how often, on average, during the previous year they consumed each food item listed in the questionnaire, with a prespecified standard portion size. Nine responses were possible, ranging from never or less than once a month to six or more times a day. The questionnaires asked about intake of several commonly consumed whole grain foods, such as cold breakfast cereals, dark bread, popcorn, oatmeal, bran added to food, wheat germ, and brown rice. Participants were asked to provide information of the types and brand names of their cold breakfast cereal, which was used to match with data provided by cereal manufacturers on the content of whole grains. Cold breakfast cereals with 25% or more whole grain or bran content by weight were considered to be whole grains. Beginning in 2002 for the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, and 2003 for the Nurses’ Health Study II, we also asked about intake of regular popcorn and light or fat free popcorn in the semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Intakes of total whole grains were estimated from all grain containing foods (rice, bread, pasta, and cold breakfast cereals) according to the dry weight of the whole grain ingredients in each food.13 23 24 By definition, foods and ingredients considered whole grains were: whole wheat and whole wheat flour, whole oats and whole oat flour, whole cornmeal and whole corn flour, whole rye and whole rye flour, whole barley, bulgur, buckwheat, brown rice and brown rice flour, popcorn, amaranth, and psyllium.

Validation studies conducted within the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study showed reasonable validity and reproducibility of the semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire assessments of whole grain foods in these cohorts.25 Consumption of whole grain foods assessed with two semiquantitative food frequency questionnaires administered 12 months apart were significantly correlated with each other. For example, the Pearson correlation coefficients were 0.57 and 0.71 for dark bread and cold breakfast cereal, respectively. The semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire assessments were also significantly correlated with those assessed with seven day diet records; the correlation coefficients were 0.58 for dark bread and 0.73 for cold breakfast cereal.

Assessment of covariates

In the Nurses’ Health Study, Nurses’ Health Study II, and Health Professionals Follow-up Study, we sent follow-up questionnaires every two yearsto collect and update the occurrence of diseases and many lifestyle and personal risk factors, including smoking status, use of vitamin supplements, alcohol consumption, menopausal status, years of use of postmenopausal hormones (Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II only), body weight, physician diagnosed hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, and other variables. Physical activity were repeatedly assessed in the three cohorts. A validated questionnaire on time spent on up to 10 recreational activities was used to derive metabolic equivalent tasks in hours per week.26 Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters to measure overall obesity. A series of validation studies showed the validity of these self-reported variables.27 28 29 30 31 We modified the alternative healthy eating index, a diet score reflecting overall diet quality and predictive of major chronic diseases,32 by removing the whole grain component.

Assessment of outcomes

Those participants with self-reported type 2 diabetes were identified through a follow-up questionnaire. Participants who reported having diabetes were sent a supplementary questionnaire to confirm the diagnosis. Before 1998, diabetes was confirmed if participants met at least one of the criteria of the National Diabetes Data Group33: raised glucose concentration (fasting plasma glucose 7.8 mmol/L, random plasma glucose 11.1 mmol/L, or plasma glucose 11.1 mmol/L ≥2 hours after an oral glucose load) and at least one symptom related to diabetes (excessive thirst, polyuria, weight loss, or hunger); no symptoms, but raised concentrations of glucose on at least two occasions; or treatment with insulin or other hypoglycemic drugs. For participants with type 2 diabetes identified after 1998, the cut-off point for fasting plasma concentrations of glucose was lowered to 7.0 mmol/L, according to the criteria of the American Diabetes Association.34 We also considered a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) concentration of 6.5% or more in the diagnostic criteria for confirming participants with type 2 diabetes identified after January 2010.35 A validation study showed that 97% of participants with self-reported type 2 diabetes confirmed by questionnaire were reconfirmed by review of the medical records.36 37 We identified deaths by reports from next of kin or postal authorities, or by searching the national death index.38 More than 97% of deaths were identified in these cohorts.38

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables, and percentages for categorical variables, based on five equal categories total whole grain consumption in each cohort. Person time for each participant was measured from the return date of the baseline food frequency questionnaire to the date of the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, date of death, date of last return of a valid follow-up questionnaire, or the end of follow-up (2014 for Nurses’ Health Study, 2016 for Health Professionals Follow-up Study, and 2017 for Nurses’ Health Study II), whichever occurred first. To better represent long term intake and to minimize within person variation, we calculated and used cumulative averages of total whole grains and each whole grain food since baseline.39 To minimize potential bias resulting from a change in usual diet because of a diagnosis of a chronic disease or condition, we stopped updating dietary information when participants first reported having myocardial infarction, stroke, cancer, hypertension, or hypercholesterolemia.40 For these participants, we carried forward the cumulative averages of dietary intake before the occurrence of the disease or symptoms to represent diet for subsequent follow-up. Because the proportion of missing values of covariates was low, ranging from 2.4% for body mass index to 5.6% for physical activity, we replaced missing values with the valid values in the most recent follow-up cycle, and otherwise missing indicators were used.

For the primary analysis, a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the associations between individual whole grain foods and total whole grain intake, and the risk of type 2 diabetes. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated by including an interaction term between whole grain intake and the duration of follow-up. No evidence of violations of the assumption was detected in each cohort (P>0.05 for all tests). Total whole grain intake was categorized into five equal groups and we used prespecified cut-off levels for ranking consumption of whole grain foods: never or less than one serving a month; one serving a month to one serving a week; and two or more servings a week. For whole grain cold breakfast cereal, dark bread, and popcorn, we used four categories because these foods have relatively higher overall intake: never or less than one serving a month; one serving a month to one serving a week; one serving a week to 4-6 servings a week; and one or more servings a day. The statistical models were adjusted for age (month), ethnicity (white, African American, Asian, other), smoking status (never smoked, past smoker, or currently smoke 1-14 cigarettes/day, 15-24 cigarettes/day, or ≥25 cigarettes/day), alcohol intake (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-9.9, 10.0-14.9, 15.0-29.9, and ≥30.0 g/day), multivitamin use (yes, no), physical activity (divided into five equal groups), modified alternative healthy eating index (divided into five equal groups), total energy (divided into five equal groups), family history of diabetes (yes, no), postmenopausal hormone use (women only; never, former, or current hormone use, or missing), and oral contraceptive use (yes, no; women only). Because the time varying body mass index (<21.0, 21.0-22.9, 23.0-24.9, 25.0-26.9, 27.0-29.9, 30.0-32.9, 33.0-34.9, or ≥35.0) could be both confounder and mediator, we also adjusted for it in a separate model. The continuous variable for each exposure was used to calculate the P value for trend and the hazard ratio of type 2 diabetes for each serving per day of intake. To evaluate the heterogeneous associations in individual whole grain foods with the risk of type 2 diabetes, we conducted a likelihood ratio test by comparing two models after adjusting for other covariates: one with total whole grains only and the other with total whole grains and seven individual whole grain foods in categorical terms. We also calculated the difference in adjusted incidence rate between the highest and lowest groups for total whole grain intake. We first used linear regression to calculate residuals of total whole grain intake after adjusting for the same covariates considered in the Cox regression models. The residuals of whole grain intake were then categorized into five equal groups. We repeated these analyses by each four year interval of follow-up to take into account time varying intake assessments. Lastly, we calculated incidence rate based on the number of patients with diabetes and person years in each of the five groups of residuals and estimated differences (and 95% confidence intervals) in incidence rates.41 The difference in incidence rate was calculated for each cohort and pooled by the fixed effects model, with weight as the inverse variance of incidence rate difference in each cohort. We also calculated the difference in incidence rate between the extremes of the five categories for total whole grain consumption in participants who were normal weight, overweight, and obese.

Stratified analysis was performed for body mass index, physical activity, smoking status, and family history of diabetes to explore effect modification. Data from the three cohorts were combined. P values for interaction were calculated from likelihood ratio tests comparing the multivariable adjusted model with and without product term between dummy variables of total whole grain intake in the five categories and dummy variables of each stratifying variable. In a secondary analysis, we examined consumption of regular and fat free or light popcorn separately (assessed from 2002 in the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study and from 2003 in the Nurses’ Health Study II) in relation to the risk of type 2 diabetes.

To assess the dose-response association between total whole grain intake and individual whole grain foods and the risk of type 2 diabetes, we combined the data from the three cohorts and fitted a cubic spline regression with the same covariates (except for the women only variables) adjusted in the primary analysis. Total whole grain intake was converted to servings by dividing by a factor of 16 (based on the dry weight estimation of serving size).

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the primary findings. First, we mutually adjusted for the individual whole grain foods to evaluate whether the associations seen for each whole grain food were independent of each other. Second, we used simply updated whole grain food intake or baseline intake instead of the cumulative averaged value to repeat the analysis. Third, we conducted a latency analysis by modeling individual whole grain food intake with the incidence of type 2 diabetes that occurred four years after the reported intake to examine the possibility of reverse causation bias. Fourth, we adjusted for baseline body mass index only to evaluate the effect of potential over adjustment of body mass index during follow-up, which could operate in the causal pathway. Fifth, we used a Markov Chain Monte Carlo based method to impute missing data on total energy (3.1% missing), physical activity (5.6% missing), body mass index (2.7% missing), and smoking status (3.0% missing) before categorizing these variables. Each cohort was imputed separately and we imputed four times to achieve relative efficiencies of more than 99% for each β coefficient. All covariates in the primary analysis were included in the multiple imputation procedures. The β coefficients estimated from imputed datasets in each cohort were combined using Rubin’s rule42 and then meta-analyzed with a fixed effects model to derive pooled hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Lastly, because participants with higher whole grain intake tended to have higher degree of health awareness, which led to more frequent examination of blood glucose, we restricted the analyses to participants with symptomatic type 2 diabetes to look at potential detection bias. In this analysis, patients with diabetes who reported having no symptoms at diagnosis were censored during follow-up. Data from each cohort were analyzed separately and were pooled with a fixed effects model. All statistical tests were two sided with a significant level of 0.05, and were performed with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in the design and implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. We did not have the infrastructure, resources, funding, or time to involve the public in study design, result interpretation, or publication.

Results

A total of 18 629 participants with type 2 diabetes were identified and confirmed during 4 618 796 person years of follow-up. The average follow-up time was 24 years. In all three cohorts at baseline, participants with higher total whole grain consumption, on average, were more likely to be white participants, were slightly older, were less likely to be current smokers, were more likely to be leaner and multivitamin users, and were more physically active, compared with participants with a lower intake. They also tended to have a lower prevalence of hypertension and family history of diabetes, higher diet quality, and more frequent screening for fasting glucose (table 1). The Pearson correlation coefficients for individual whole grain food intake were small to modest, ranging from 0.03 between whole grain breakfast cereal and popcorn, to 0.14 between added oatmeal and brown rice, except that the correlation was relatively higher (r=0.28) between added bran and wheat germ (supplementary table 1).

Table 1.

Age standardized characteristics of study participants in Nurses’ Health Study (1984-2014), Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2017), and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (1986-2016). Data are mean (standard deviation) or percentages, and are standardized to the age distribution of the study population

| Total whole grain consumption (divided into five equal groups) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | |

| Nurses’ Health Study | |||||

| No of servings/day (median) | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| No of participants | 13 650 | 13 992 | 13 878 | 13 754 | 13 865 |

| Age | 49.6 (6.9) | 49.7 (7.0) | 50.1 (7.1) | 51.0 (7.2) | 52.3 (7.2) |

| Body mass index at baseline | 25.1 (4.9) | 25.1 (4.8) | 25.0 (4.6) | 24.7 (4.4) | 24.2 (4.1) |

| Race (%) | |||||

| White | 96.9 (n=13 227) | 97.9 (n=13 698) | 98.1 (n=13 614) | 98.1 (n=13 493) | 98.3 (n=13 629) |

| African American | 0.2 (n=27) | 0.2 (n=28) | 0.2 (n=28) | 0.2 (n=28) | 0.2 (n=28) |

| Asian | 1.2 (n=164) | 0.7 (n=98) | 0.6 (n=83) | 0.5 (n=69) | 0.4 (n=55) |

| Others | 1.7 (n=232) | 1.2 (n=168) | 1.1 (n=153) | 1.2 (n=165) | 1.1 (n=153) |

| Physical activity (MET hours/week; median (IQR)) | 5.1 (2.0-15.4) | 6.9 (2.4-16.6) | 7.7 (2.9-18.9) | 8.4 (3.1-20.2) | 10.0 (3.4-21.5) |

| Hypertension (%) | 9.0 (n=1229) | 8.2 (n=1147) | 7.4 (n=1027) | 7.0 (n=963) | 6.6 (n=915) |

| High cholesterol (%) | 2.8 (n=382) | 2.8 (n=392) | 3.0 (n=416) | 3.4 (n=468) | 3.9 (n=541) |

| Current smokers (%) | 36.4 (n=4969) | 27.7 (n=3876) | 23.4 (n=3247) | 19.0 (n=2613) | 14.5 (n=2010) |

| Family history of diabetes (%) | 29.1 (n=3972) | 28.1 (n=3932) | 28.5 (n=3955) | 27.8 (n=3824) | 27.6 (n=3827) |

| Multivitamin use (%) | 30.2 (n=4122) | 33.9 (n=4743) | 36.8 (n=5107) | 39.8 (n=5474) | 44.1 (n=6114) |

| Oral contraceptive use (%) | 47.2 (n=6443) | 49.3 (n=6898) | 50.1 (n=6953) | 50.1 (n=6891) | 50.6 (n=7016) |

| Hormone use (%) | |||||

| Premenopausal | 53.2 (n=7262) | 53.5 (n=7486) | 54.1 (n=7508) | 53.6 (n=7372) | 53.3 (n=7390) |

| Postmenopausal (never) | 26.9 (n=3672) | 25.3 (n=3540) | 24.1 (n=3345) | 22.9 (n=3150) | 22.1 (n=3064) |

| Postmenopausal (current) | 9.1 (n=1242) | 10.7 (n=1497) | 11.1 (n=1540) | 12.2 (n=1678) | 13.7 (n=1900) |

| Postmenopausal (previous) | 10.7 (n=1461) | 10.6 (n=1483) | 10.7 (n=1485) | 11.2 (n=1540) | 10.9 (n=1511) |

| Alcohol consumption (g/day; median (IQR)) | 3.0 (0.5-12.5) | 2.7 (0.5-10.0) | 2.5 (0.5-9.3) | 2.2 (0.4-8.2) | 1.7 (0.0-6.5) |

| Modified alternative healthy eating index | 42.8 (9.9) | 44.2 (9.6) | 45.6 (9.8) | 46.9 (10.0) | 49.5 (10.6) |

| Total energy intake (kcal/day)* | 1708 (552) | 1792 (542) | 1782 (540) | 1778 (522) | 1653 (477) |

| Nurses’ Health Study II | |||||

| No of servings/day (median) | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| No of participants | 17 877 | 17 754 | 17 844 | 17 764 | 17 881 |

| Age | 36.5 (4.7) | 36.5 (4.7) | 36.4 (4.7) | 36.4 (4.6) | 36.9 (4.6) |

| Body mass index at baseline | 25.1 (5.9) | 24.9 (5.5) | 24.7 (5.3) | 24.3 (4.9) | 23.8 (4.6) |

| Race (%) | |||||

| White | 94.3 (n=16 858) | 96.2 (n=17 079) | 97.2 (n=17 344) | 97.6 (n=17 338) | 97.3 (n=17 398) |

| African American | 0.5 (n=89) | 0.6 (n=107) | 0.4 (n=71) | 0.4 (n=71) | 0.6 (n=107) |

| Asian | 3.1 (n=554) | 1.5 (n=266) | 1.1 (n=196) | 0.9 (n=160) | 1.0 (n=179) |

| Others | 2.1 (n=375) | 1.7 (n=302) | 1.3 (n=232) | 1.1 (n=195) | 1.1 (n=197) |

| Physical activity (MET hours/week; median (IQR)) | 9.4 (3.4-21.8) | 11.2 (4.5-24.6) | 12.5 (5.2-25.9) | 13.8 (5.9-28.2) | 16.5 (7.2-32.8) |

| Hypertension (%) | 4.1 (n=733) | 3.6 (n=639) | 3.2 (n=571) | 2.8 (n=497) | 2.4 (n=429) |

| High cholesterol (%) | 9.9 (n=1770) | 9.6 (n=1704) | 9.3 (n=1659) | 8.9 (n=1581) | 8.8 (n=1574) |

| Current smokers (%) | 19.4 (n=3468) | 14.4 (n=2557) | 11.2 (n=1999) | 8.5 (n=1510) | 7.1 (n=1270) |

| Family history of diabetes (%) | 43.1 (n=7705) | 42.2 (n=7492) | 41.5 (n=7405) | 41.6 (n=7390) | 39.4 (n=7045) |

| Multivitamin use (%) | 36.1 (n=6454) | 40.7 (n=7226) | 44.1 (n=7869) | 47.7 (n=8473) | 50.7 (n=9066) |

| Oral contraceptive use (%) | 82.5 (n=14749) | 84.5 (n=15002) | 84.6 (n=15096) | 84.3 (n=14975) | 83.4 (n=14913) |

| Hormone use (%) | |||||

| Premenopausal | 97.1 (n=17 359) | 96.8 (n=17 186) | 97.2 (n=17 344) | 97.0 (n=17 231) | 96.8 (n=17 309) |

| Postmenopausal (never) | 0.2 (n=36) | 0.2 (n=36) | 0.2 (n=36) | 0.2 (n=36) | 0.2 (n=36) |

| Postmenopausal (current) | 2.4 (n=429) | 2.7 (n=479) | 2.4 (n=428) | 2.6 (n=462) | 2.7 (n=483) |

| Postmenopausal (previous) | 0.3 (n=54) | 0.2 (n=36) | 0.2 (n=36) | 0.2 (n=36) | 0.3 (n=54) |

| Alcohol consumption (g/day; median (IQR)) | 0.9 (0.0-3.0) | 0.9 (0.0-3.8) | 0.9 (0.0-3.7) | 0.9 (0.0-3.5) | 0.9 (0.0-3.0) |

| Modified alternative healthy eating index | 41.6 (9.7) | 44.0 (9.5) | 45.7 (9.7) | 47.1 (9.7) | 50.7 (10.0) |

| Total energy intake (kcal/day)* | 1770 (578) | 1821 (561) | 1824 (551) | 1820 (526) | 1711 (510) |

| Health Professionals Follow-up Study | |||||

| No of servings/day (median) | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.8 |

| No of participants | 7312 | 7320 | 7249 | 7327 | 7317 |

| Age | 52.4 (9.2) | 51.9 (9.3) | 52.3 (9.3) | 52.7 (9.4) | 53.5 (9.5) |

| Body mass index at baseline | 25.7 (3.3) | 25.8 (3.3) | 25.5 (3.3) | 25.3 (3.2) | 24.7 (2.9) |

| Race (%) | |||||

| White | 93.2 (n=6814) | 95.2 (n=6969) | 95.9 (n=6952) | 96.9 (n=7100) | 95.6 (n=6995) |

| African American | 2.3 (n=168) | 2.2 (n=161) | 2.2 (n=159) | 1.8 (n=132) | 2.3 (n=168) |

| Asian | 3.5 (n=256) | 1.3 (n=95) | 1.0 (n=72) | 0.8 (n=59) | 1.2 (n=88) |

| Others | 1.0 (n=73) | 1.2 (n=88) | 0.9 (n=65) | 0.5 (n=37) | 0.8 (n=59) |

| Physical activity (MET hours/week; median (IQR)) | 7.7 (2.0-21.7) | 9.5 (3.0-24.6) | 10.9 (3.5-25.5) | 12.0 (4.3-27.1) | 15.0 (5.3-30.9) |

| Hypertension (%) | 21.2 (n=1550) | 19.8 (n=1449) | 17.3 (n=1254) | 17.1 (n=1253) | 17.4 (n=1273) |

| High cholesterol (%) | 9.0 (n=658) | 9.2 (n=673) | 9.6 (n=696) | 10.0 (n=733) | 12.2 (n=893) |

| Current smokers (%) | 17.2 (n=1258) | 11.8 (n=864) | 8.3 (n=602) | 5.8 (n=425) | 4.2 (n=307) |

| Family history of diabetes (%) | 21.2 (n=1550) | 22.2 (n=1625) | 21.3 (n=1544) | 21.4 (n=1568) | 21.0 (n=1537) |

| Multivitamin use (%) | 34.8 (n=2545) | 37.6 (n=2752) | 41.2 (n=2987) | 45.1 (n=3304) | 50.5 (n=3695) |

| Alcohol consumption (g/day; median (IQR)) | 7.0 (1.0-19.5) | 6.7 (1.1-16.7) | 6.5 (1.0-16.1) | 5.8 (0.9-13.8) | 3.9 (0.0-12.2) |

| Modified alternative healthy eating index | 45.9 (10.6) | 48.5 (10.3) | 49.9 (10.4) | 51.5 (10.5) | 54.7 (10.3) |

| Total energy intake (kcal/day)* | 1992 (649) | 2039 (644) | 2060 (636) | 2022 (594) | 1883 (555) |

IQR=interquartile range; MET=metabolic equivalent task.

1 kcal=4.18 kJ=0.00418 MJ.

After adjusting for body mass index and other lifestyle and dietary risk factors for diabetes, higher total whole grain consumption was consistently associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes in all three cohorts (table 2). In pooled results, comparing the extremes of the five equal categories for total whole grain intake, a 29% (hazard ratio 0.71, 95% confidence interval 0.67 to 0.74, P<0.001 for trend) lower rate of type 2 diabetes was found. Table 3 shows the associations between consumption of specific whole grain foods and risk of type 2 diabetes. The pooled hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) comparing participants consuming one or more servings a day with those consuming less than one serving a month were 0.81 (0.77 to 0.86) for whole grain cold breakfast cereal, 0.79 (0.75 to 0.83) for dark bread, and 1.08 (1.00 to 1.17) for popcorn. For other whole grain foods with lower average intake levels, comparing consumption of two or more servings a week with less than one serving a month, the pooled hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) were 0.79 (0.75 to 0.83) for oatmeal, 0.88 (0.82 to 0.94) for brown rice, 0.85 (0.80 to 0.90) for added bran, and 0.88 (0.78 to 0.98) for wheat germ. Comparing the extremes of the five categories for total whole grain consumption, the incidence rate differences per 100 000 person years were −95 (−112 to −77). Supplementary table 2 shows the results in the individual cohorts. The goodness of fit of the fully adjusted model was significantly improved by also adjusting for individual whole grain foods (Nurses’ Health Study, P<0.001; Nurses’ Health Study II, P<0.001; Health Professionals Follow-up Study, P<0.001) suggesting potentially heterogeneous associations in different individual whole grain foods with diabetes risk. To test if the significant heterogeneity was driven by the positive association for popcorn, we repeated the likelihood ratio test by removing popcorn in the model and found similar results.

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios of type 2 diabetes for total whole grain consumption in the Nurses’ Health Study (1984-2014), Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2017), and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (1986-2016). Model data are hazard ratio (95% confidence interval)

| Total whole grain consumption (divided into five equal groups) | P for trend§ | Per serving daily | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | |||

| Nurses’ Health Study | |||||||

| No of patients with diabetes/person years | 2229/343 880 | 1855/344 836 | 1624/344 983 | 1342/344 421 | 1120/345 412 | — | — |

| Age adjusted model | 1.00 | 0.83 (0.78 to 0.88) | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.77) | 0.60 (0.56 to 0.64) | 0.49 (0.46 to 0.53) | <0.001 | 0.71 (0.68 to 0.73) |

| Multivariable adjusted model* | 1.00 | 0.85 (0.80 to 0.90) | 0.76 (0.72 to 0.82) | 0.65 (0.60 to 0.69) | 0.55 (0.51 to 0.59) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.73 to 0.78) |

| Additionally adjusting for body mass index† | 1.00 | 0.86 (0.81 to 0.91) | 0.80 (0.75 to 0.85) | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.77) | 0.68 (0.63 to 0.73) | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.81 to 0.87) |

| Nurses’ Health Study II | |||||||

| No of patients with diabetes/person years | 2156/414 862 | 1609/415 300 | 1324/416 443 | 1079/416 435 | 904/416 499 | — | — |

| Age adjusted model | 1.00 | 0.77 (0.72 to 0.82) | 0.64 (0.59 to 0.68) | 0.52 (0.48 to 0.56) | 0.42 (0.39 to 0.45) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.67 to 0.71) |

| Multivariable adjusted model* | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.81 to 0.93) | 0.77 (0.72 to 0.82) | 0.66 (0.61 to 0.71) | 0.57 (0.53 to 0.62) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.77 to 0.82) |

| Additionally adjusting for body mass index† | 1.00 | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.96) | 0.84 (0.78 to 0.90) | 0.76 (0.70 to 0.82) | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.80) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.85 to 0.91) |

| Health Professionals Follow-up Study | |||||||

| No of patients with diabetes/person years | 934/162 664 | 755/163 344 | 660/162 969 | 552/163 363 | 486/163 385 | — | — |

| Age adjusted model | 1.00 | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.90) | 0.71 (0.64 to 0.79) | 0.59 (0.53 to 0.66) | 0.51 (0.46 to 0.57) | <0.001 | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.84) |

| Multivariable adjusted model* | 1.00 | 0.85 (0.77 to 0.93) | 0.76 (0.69 to 0.84) | 0.65 (0.58 to 0.73) | 0.59 (0.53 to 0.66) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.82 to 0.88) |

| Additionally adjusting for body mass index† | 1.00 | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.92) | 0.81 (0.73 to 0.89) | 0.72 (0.65 to 0.80) | 0.72 (0.64 to 0.81) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.95) |

| Pooled results‡ | |||||||

| No of patients with diabetes/person years | 5319/921 406 | 4219/923 480 | 3608/924 395 | 2973/924 219 | 2510/925 296 | — | — |

| Age adjusted model | 1.00 | 0.80 (0.77 to 0.84) | 0.69 (0.66 to 0.72) | 0.56 (0.54 to 0.59) | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.49) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.72 to 0.74) |

| Multivariable adjusted model* | 1.00 | 0.86 (0.82 to 0.89) | 0.76 (0.73 to 0.80) | 0.65 (0.62 to 0.68) | 0.57 (0.54 to 0.60) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.78 to 0.81) |

| Additionally adjusting for body mass index† | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.84 to 0.91) | 0.82 (0.78 to 0.85) | 0.73 (0.70 to 0.77) | 0.71 (0.67 to 0.74) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.86 to 0.89) |

Adjusted for age (years), ethnicity (white, African American, Asian, others), smoking status (never smoked, past smoker, currently smoke 1-14 cigarettes/day, 15-24 cigarettes/day, or ≥25 cigarettes/day), alcohol intake (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-9.9, 10.0-14.9, 15.0-29.9, and ≥30.0 g/day), multivitamin use (yes, no), physical activity (divided into five equal groups), modified alternative healthy eating index (divided into five equal groups), and family history of diabetes. For women, postmenopausal hormone use (never, former, or current hormone use, or missing), and oral contraceptive use were further adjusted.

Additionally adjusted for time varying body mass index (<21.0, 21.0-22.9, 23.0-24.9, 25.0-26.9, 27.0-29.9, 30.0-32.9, 33.0-34.9, or ≥35.0).

Study estimates from three cohorts were pooled with a fixed effects model.

Calculated with continuous exposure variables.

Table 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios of type 2 diabetes for individual whole grain food consumption in the Nurses’ Health Study (1984-2014), Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2017), and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (1986-2016). Model data are hazard ratio (95% confidence interval)

| Consumption level | P for trend‡ | Per serving daily | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never or <1 serving/month | 1 serving/month to 1 serving/week |

1 serving/week to 4-6 servings/week |

≥1 serving/day | |||

| Whole grain cold breakfast cereal | ||||||

| No of patients with diabetes/person time | 6948/1 385 562 | 4113/919 380 | 5571/1 664 324 | 1997/649 531 | — | — |

| Multivariable adjusted model* | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.96) | 0.67 (0.65 to 0.70) | 0.66 (0.63 to 0.70) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.59 to 0.65) |

| Additionally adjusting for body mass index† | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.97) | 0.75 (0.73 to 0.78) | 0.81 (0.77 to 0.86) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.82) |

| Dark bread | ||||||

| No of patients with diabetes/person time | 2559/490 667 | 4117/916 951 | 6376/1 728 628 | 5577/1 482 551 | — | — |

| Multivariable adjusted model* | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.99) | 0.77 (0.73 to 0.80) | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.82) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.89 to 0.93) |

| Additionally adjusting for body mass index† | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.96) | 0.78 (0.75 to 0.82) | 0.79 (0.75 to 0.83) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95) |

| Popcorn | ||||||

| No of patients with diabetes/person time | 4487/1 093 043 | 8979/2 323 828 | 4221/1 025 642 | 942/176 283 | — | — |

| Multivariable adjusted model* | 1.00 | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.11) | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.14) | 1.46 (1.35 to 1.57) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.20 to 1.30) |

| Additionally adjusting for body mass index† | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.00) | 0.92 (0.87 to 0.96) | 1.08 (1.00 to 1.17) | 0.002 | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.12) |

| Oatmeal | ||||||

| No of patients with diabetes/person time | 9723/2 248 899 | 6821/1 685 499 | 2085/684 398 | — | — | — |

| Multivariable adjusted model* | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.97) | 0.69 (0.66 to 0.72) | — | <0.001 | 0.56 (0.49 to 0.63) |

| Additionally adjusting for body mass index† | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.98) | 0.79 (0.75 to 0.83) | — | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.66 to 0.84) |

| Brown rice | ||||||

| No of patients with diabetes/person time | 11 861/2 610 337 | 5855/1 684 788 | 913/323 671 | — | — | — |

| Multivariable adjusted model* | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.96) | 0.79 (0.74 to 0.85) | — | <0.001 | 0.72 (0.61 to 0.86) |

| Additionally adjusting for body mass index† | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.94) | — | 0.11 | 0.87 (0.74 to 1.03) |

| Added bran | ||||||

| No of patients with diabetes/person time | 15 419/3 634 960 | 1989/566 549 | 1221/417 288 | — | — | — |

| Multivariable adjusted model* | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.84 to 0.92) | 0.72 (0.68 to 0.77) | — | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.72 to 0.84) |

| Additionally adjusting for body mass index† | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.98) | 0.85 (0.80 to 0.90) | — | 0.002 | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.96) |

| Wheat germ | ||||||

| No of patients with diabetes/person time | 17 399/4 189 252 | 914/303 909 | 316/125 634 | — | — | — |

| Multivariable adjusted model* | 1.00 | 0.83 (0.77 to 0.88) | 0.68 (0.61 to 0.76) | — | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.50 to 0.73) |

| Additionally adjusting for body mass index† | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.99) | 0.88 (0.78 to 0.98) | — | 0.14 | 0.88 (0.74 to 1.04) |

Adjusted for age (years), ethnicity (white, African American, Asian, others), smoking status (never smoked, past smoker, currently smoke 1-14 cigarettes/day, 15-24 cigarettes/day, or ≥25 cigarettes/day), alcohol intake (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-9.9, 10.0-14.9, 15.0-29.9, and ≥30.0 g/day), multivitamin use (yes, no), physical activity (divided into five equal groups), modified alternative healthy eating index (divided into five equal groups), and family history of diabetes. For women, postmenopausal hormone use (never, former, or current hormone use, or missing), and oral contraceptive use were further adjusted. Study estimates from three cohorts were pooled with a fixed effects model.

Additionally adjusted for time varying body mass index (<21.0, 21.0-22.9, 23.0-24.9, 25.0-26.9, 27.0-29.9, 30.0-32.9, 33.0-34.9, or ≥35.0).

Calculated with continuous exposure variables.

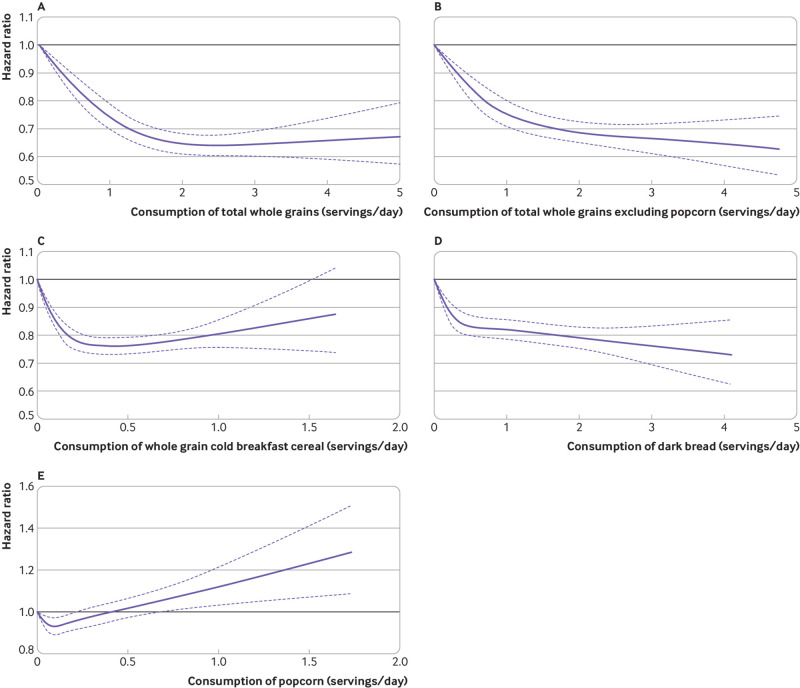

In the cubic spline model adjusted for the same covariates in table 2, we saw a non-linear inverse association between consumption of total whole grains and the risk of type 2 diabetes (fig 1; P<0.001 for non-linearity). The rate reduction slightly plateaued at consumption of more than two servings a day of total whole grains. For total whole grains excluding the contribution from popcorn, we found a similar significant P value for non-linearity (P<0.001), although the non-linear pattern was less apparent (fig 1; P<0.001 for non-linearity). For individual whole grain foods, non-linear associations were seen for consumption of whole grain breakfast cereal and dark bread, and the risk of diabetes, where the rate reduction plateaued at about 0.5 servings a day (fig 1; P<0.001 for non-linearity). A non-linear association was also found between popcorn intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: the rate of diabetes was significantly lower at consumption of one serving a week of popcorn, beyond which the rate of diabetes monotonically increased and reached statistical significance at about one serving a day (fig 1; P<0.001 for non-linearity). This result was consistent with our observation that participants who consumed one to six servings a week of popcorn had an 8% (95% confidence interval 4% to 13%) lower rate of type 2 diabetes than non-consumers (<1 serving/month; table 3). The associations for other whole grain foods seemed to be more linear.

Fig 1.

Multivariable adjusted, pooled, dose-response associations between total whole grain intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in the Nurses’ Health Study (1984-2014), Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2017), and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (1986-2016). Data from three cohorts were combined and truncated at the 0.5th and 99.5th centiles. (A) Consumption of total whole grains, 0.03-5.0 servings/day, (B) consumption of total whole grains excluding popcorn, 0-4.8 servings/day, (C) consumption of whole grain cold breakfast cereal, 0-1.65 servings/day, (D) consumption of dark bread, 0-4.3 servings/day, and (E) consumption of popcorn, 0-1.8 servings/day. Hazard ratios were adjusted for age (years), ethnicity (white, African American, Asian, others), body mass index (<21.0, 21.0-22.9, 23.0-24.9, 25.0-26.9, 27.0-29.9, 30.0-32.9, 33.0-34.9, or ≥35.0), smoking status (never smoked, past smoker, current smoker of 1-14 cigarettes/day, 15-24 cigarettes/day, or ≥25 cigarettes/day), alcohol intake (0, 0.1-4.9, 5.0-9.9, 10.0-14.9, 15.0-29.9, and ≥30.0 g/day), multivitamin use (yes, no), physical activity (divided into five equal groups), modified alternative healthy eating index (divided into five equal groups), and family history of diabetes. P<0.001 for non-linearity for all parts

In the stratified analysis that adjusted for the same covariates in table 2, the inverse associations between total whole grain intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes seemed to be stronger in participants who were lean or overweight compared with participants who were obese (P=0.003 for interaction) whereas we found no significant effect modification for smoking status, physical activity, or family history of diabetes (table 4).

Table 4.

Adjusted hazard ratios of type 2 diabetes for total whole grain consumption, stratified by body mass index, family history of diabetes, physical activity, and smoking status*†. Data are hazard ratio (95% confidence interval)

| Total whole grain consumption (divided into five equal groups) | P for interaction‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | ||

| Body mass index | ||||||

| <25 | 1.00 | 0.75 (0.64 to 0.88) | 0.69 (0.59 to 0.81) | 0.70 (0.59 to 0.82) | 0.55 (0.46 to 0.66) | 0.003 |

| 25-30 | 1.00 | 0.85 (0.77 to 0.94) | 0.80 (0.72 to 0.88) | 0.65 (0.59 to 0.73) | 0.66 (0.59 to 0.74) | |

| ≥30 | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.98) | 0.85 (0.80 to 0.91) | 0.79 (0.74 to 0.85) | 0.77 (0.71 to 0.83) | |

| Physical activity (divided into three equal groups) | ||||||

| Group 1 | 1.00 | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.96) | 0.84 (0.78 to 0.90) | 0.74 (0.68 to 0.80) | 0.73 (0.67 to 0.80) | 0.27 |

| Group 2 | 1.00 | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.99) | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.89) | 0.78 (0.71 to 0.86) | 0.73 (0.65 to 0.81) | |

| Group 3 | 1.00 | 0.82 (0.73 to 0.92) | 0.75 (0.67 to 0.84) | 0.68 (0.60 to 0.77) | 0.65 (0.57 to 0.74) | |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smokers | 1.00 | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.95) | 0.83 (0.77 to 0.89) | 0.76 (0.71 to 0.82) | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.77) | 0.20 |

| Past smokers | 1.00 | 0.85 (0.78 to 0.92) | 0.79 (0.73 to 0.86) | 0.71 (0.65 to 0.77) | 0.65 (0.59 to 0.71) | |

| Current smokers | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.80 to 1.09) | 0.88 (0.74 to 1.05) | 0.72 (0.59 to 0.88) | 0.87 (0.69 to 1.10) | |

| Family history of diabetes | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.99) | 0.82 (0.76 to 0.89) | 0.77 (0.70 to 0.83) | 0.72 (0.66 to 0.79) | 0.76 |

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.86 (0.81 to 0.92) | 0.81 (0.75 to 0.86) | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.78) | 0.70 (0.65 to 0.76) | |

Adjusted for same covariates as in main analysis except for the stratification variable. Continuous body mass index and physical activity were adjusted to minimize residual confounding.

Data from three cohorts were combined for stratified analysis.

Calculated from the likelihood ratio test comparing multivariable adjusted model with and without the product terms, between dummy variables of total whole grain intake in groups and dummy variables of each stratifying variable.

In a secondary analysis that examined regular and light or fat free popcorn separately, comparing participants with two or more servings a week with those consuming less than one serving a month, we found no significant associations for either type of popcorn, except for a borderline statistically significant P value for trend (P=0.06) for consumption of the light or fat free popcorn (supplementary table 3).

After mutual adjustment for individual whole grain foods, the estimates were reduced but remained statistically significant except for the association for wheat germ which was no longer statistically significant (supplementary table 4). With baseline dietary information or simply updated intake, adding a four year lag between dietary assessments and incidence of diabetes, or adjusting for baseline body mass index, produced similar results (supplementary table 5), except that the association for wheat germ was not statistically significant with the simply updated value. Restricting to participants with symptomatic type 2 diabetes resulted in similar estimates for most whole grain foods (supplementary table 6). With imputed values of missing covariates, we also found similar results (supplementary table 7).

Discussion

Principal findings

Findings from three prospective cohorts showed that higher total whole grain intake was significantly associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes. Although these inverse associations were seen for most individual whole grain foods, we also found an elevated increased rate of type 2 diabetes associated with consumption of one of more servings of popcorn a day. The association for individual whole grain foods seemed to be independent of other whole grain foods, except for wheat germ. Dose-response analyses showed that the rate reduction plateaued at high intake levels for total whole grains, and whole grain cold breakfast cereal and dark bread, whereas a J shaped association was found for popcorn intake where the rate of diabetes did not increase until intake exceeded about one serving of popcorn a day.

Comparison with other studies

The inverse association between higher whole grain consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes has been found in previous studies. A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies showed that total whole grain consumption was associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes.43 Moreover, this meta-analysis showed that a higher intake of several whole grain foods, including whole grain bread, whole grain breakfast cereals, wheat bran, and brown rice, were associated with a similar risk reduction in type 2 diabetes. Data for other types of whole grain foods in this meta-analysis were sparse, however, and no previous studies were specifically designed to examine the associations with individual whole grain foods. Because individual whole grain foods contain various amounts of dietary fiber, magnesium, antioxidants, and phytochemicals, they might have distinct associations with the risk of type 2 diabetes.44 For example, on average, raw oat bran has 14.5 g of total dietary fiber per cup (95 g dry weight), but one cup (185 g) of brown rice only contains 6.66 g of fiber.45 Similarly, magnesium is richest in raw oat bran (>300 mg/100 g) and wheat germ (235 mg/100 g), and poorest in rye bread (40 mg/100 g) and brown rice (39 mg/100 g), with breakfast cereal, oatmeal, and popcorn in the middle (100-150 mg/100 g).45 Also, heterogeneous glycemic properties in individual whole grains might also exert differential health effects on glucose metabolism as a higher glycemic index was associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes.46 For example, the average glycemic index is 42 for whole grain cold breakfast cereal, 55 for oatmeal and brown rice, and 27-70 for whole grain bread, depending on the ingredients (eg, barley, buckwheat, oats, rye), whereas popcorn has the highest glycemic index value of 72.47 In our analysis, we showed that consumption of the most commonly eaten whole grain foods was associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes, but excess popcorn consumption was associated with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes. The statistically significant P values from the goodness of fit tests across the three cohorts, even after removing popcorn, suggested potential heterogeneous effects in individual whole grain foods with the risk of type 2 diabetes. Nevertheless, this finding should be interpreted with caution because of similar effect estimates for most individual whole grain foods. The highly statistically significant P values could be because of the abundant statistical power in the three cohorts.

In our analysis, we saw a non-linear dose-response association between total whole grain intake and diabetes. This observation is consistent with previous studies collectively suggesting that the rate reduction of diabetes might plateau at two to three servings a day.43 Similar non-linear associations were also seen for two whole grains foods, whole grain cold breakfast cereal and dark bread, where intake levels were relatively higher than other whole grains. A J shaped association was found for popcorn intake in relation to the risk of type 2 diabetes; the rate reduction for diabetes reached nadir at about one serving of popcorn a week, above which the rate monotonically increased and reached statistical significance at around one serving a day. This J shaped association of popcorn intake with the risk of diabetes might partially account for the non-linear association for total whole grains, which became more linear when we removed popcorn from the calculation of total whole grain intake. Nonetheless, these non-linear associations for individual whole grain foods deserve further investigation.

Potential reasons for the J shaped association between popcorn intake and the risk of diabetes warrants further discussion. Popcorn is a popular food in the United States; Americans consume, on average, 15 billion quarts of popcorn annually, 70% of which is home popped and prepopped.48 Popcorns, as a whole grain food, are known to contain relatively higher amounts of fiber and have a higher satiety index than other commonly consumed snacks, such as potato chips.49 50 Unhealthful ingredients, such as salt, butter, and sugar, are often added during commercial processing of popcorns, however, and thus many brands of popcorns sold in United States are classified as ultraprocessed foods.51 52 53 A pilot study conducted in 675 participants in our cohorts showed that 58%, 32%, and 10% of the popcorns consumed were microwaved, home popped, and ready-to-eat types, respectively. Also, most popcorn consumed by the participants was prepared with butter, cheese, salt, or sugar (supplementary table 8). Other unhealthy ingredients could include trans fatty acids,54 which are associated with a significantly increased risk of type 2 diabetes.55 Moreover, studies have shown that microwave popcorn packaging contains perfluoroalkyl substances, a group of anthropogenic chemicals with endocrine disrupting properties, which can contaminate popcorn.56 57 Several studies showed that these compounds were associated with poor glucose metabolism,58 59 weight gain,60 and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes.61 Previous research showed that higher popcorn intake was often correlated with a snacking pattern that is associated with weight gain62 and a risk of diabetes.63 Collectively, these findings suggest that at high intake levels of popcorn, such as those exceeding one serving a day, the beneficial effects of whole grain ingredients in popcorn might be outweighed by unhealthy constituents introduced during the processing of popcorns.

An interesting finding in the subgroup analysis was a relatively weaker inverse association between total whole grain intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes in participants who were obese compared with participants who were lean or overweight. Participants who were obese might have had a high risk profile characterized by chronic inflammation, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance, which could partially offset the beneficial effects of whole grain intake on glucose metabolism. Given the much higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes in individuals who are obese, the relatively weaker relative risk might still be translated into a substantial reduction in the absolute rate in this high risk group of participants. Our data showed that the adjusted incidence rate difference per 100 000 person years (95% confidence interval) between the highest and lowest categories for total whole grain consumption was −29 (−40 to −18) in participants with normal weight, −126 (−157 to −95) in participants who were overweight, and −170 (−254 to −86) in participants who were obese. Moreover, our data showed that participants who were obese, on average, consumed more popcorn than their non-obese counterparts (0.15 servings/day, 0.17 servings/day, and 0.20 servings/day for participants who were lean, overweight, and obese, respectively) whereas their consumption levels for other whole grain foods were either similar or lower (data not shown). This disproportional higher consumption of popcorns in participants who were obese might also contribute to the weaker association of whole grain intake with the risk of type 2 diabetes. Lastly, given a borderline significant P value and potential multiple testing issues in the stratified analysis, we cannot rule out the possibility of a chance finding for this effect modification by body mass index.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The strengths of our study include the use of data from three large cohort studies with long term follow-ups, comprehensive, repeated assessments of diet and potential confounders, and high follow-up rates. Also, along with total whole grains, our study included seven commonly consumed individual whole grain foods and assessed their associations with the risk of type 2 diabetes. Moreover, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to show the robustness of the findings.

Potential limitations warrant consideration. First, although we adjusted for many lifestyle practices and diet quality, residual or unmeasured confounding cannot be excluded in observational studies. Second, multiple comparisons could result in false positive results because we examined the associations for seven whole grain foods simultaneously. Our main results remained statistically significant for most whole grain foods, however, even after adjusting for the multiplicity with the conservative Bonferroni correction, and the consistent associations across three cohorts made the chance findings less likely. Lastly, our observations might largely relate to white health professionals and lack generalizability to other populations with different characteristics.

Conclusion and policy implications

In conclusion, higher consumption of total whole grains and the most commonly consumed whole grain foods was significantly associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes. These findings provide further support for the current recommendations that promote increased consumption of whole grain as part of a healthy diet for the prevention of type 2 diabetes.

What is already known on this topic

Consumption of total whole grains has been consistently associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes

Associations between consumption of individual whole grain foods and the risk of type 2 diabetes, however, are less explored

What this study adds

Compared with the lowest intake group, the highest consumption levels of several commonly eaten whole grain foods, including whole grain breakfast cereal, oatmeal, dark bread, brown rice, added bran, and wheat germ, were significantly associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes

Dose-response analyses showed that the risk reduction for type 2 diabetes plateaued at about 0.5 servings a day for whole grain cold breakfast cereal and dark bread

A J shaped association was found for popcorn intake where the risk of type 2 diabetes was not significantly raised until consumption exceeded about one serving a day

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study for their valuable contributions.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplementary material

Contributors: YH and QS designed the study. WCW, JEM, FBH, and QS were involved in data collection. YH, MD, LS, BR, MW, and QS provided statistical expertise. YH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by research grants CA186107, CA176726, CA167552, HL034594, HL035464, DK112940, and DK120870 from the National Institutes of Health. The sponsors had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. QS had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support from the National Institutes of Health for the submitted work. QS reports receiving consulting fees from Emavant Solutions GmbH, outside the submitted work. FBH reports grants from California Walnut Commission, personal fees from Metagenics, personal fees from Standard Process, and personal fees from Diet Quality Photo Navigation, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors report no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The Nurses’ Health Study, Nurses’ Health Study II, and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study were approved by the institutional review boards at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. The return of the completed self-administered questionnaires was considered to imply informed consent.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

The lead author (YH) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community. The participants are updated on the study outcomes and developments through the study websites (www.nurseshealthstudy.org and www.hsph.harvard.edu/hpfs) and newsletters.

References

- 1. Slavin J. Whole grains and human health. Nutr Res Rev 2004;17:99-110. 10.1079/NRR200374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Karl JP, Meydani M, Barnett JB, et al. Substituting whole grains for refined grains in a 6-wk randomized trial favorably affects energy-balance metrics in healthy men and postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;105:589-99. 10.3945/ajcn.116.139683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vanegas SM, Meydani M, Barnett JB, et al. Substituting whole grains for refined grains in a 6-wk randomized trial has a modest effect on gut microbiota and immune and inflammatory markers of healthy adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;105:635-50. 10.3945/ajcn.116.146928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kirwan JP, Malin SK, Scelsi AR, et al. A whole-grain diet reduces cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Nutr 2016;146:2244-51. 10.3945/jn.116.230508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kristensen M, Toubro S, Jensen MG, et al. Whole grain compared with refined wheat decreases the percentage of body fat following a 12-week, energy-restricted dietary intervention in postmenopausal women. J Nutr 2012;142:710-6. 10.3945/jn.111.142315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maki KC, Beiseigel JM, Jonnalagadda SS, et al. Whole-grain ready-to-eat oat cereal, as part of a dietary program for weight loss, reduces low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in adults with overweight and obesity more than a dietary program including low-fiber control foods. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:205-14. 10.1016/j.jada.2009.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tighe P, Duthie G, Vaughan N, et al. Effect of increased consumption of whole-grain foods on blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk markers in healthy middle-aged persons: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:733-40. 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pereira MA, Jacobs DR, Jr, Pins JJ, et al. Effect of whole grains on insulin sensitivity in overweight hyperinsulinemic adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;75:848-55. 10.1093/ajcn/75.5.848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Katcher HI, Legro RS, Kunselman AR, et al. The effects of a whole grain-enriched hypocaloric diet on cardiovascular disease risk factors in men and women with metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:79-90. 10.1093/ajcn/87.1.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mellen PB, Walsh TF, Herrington DM. Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2008;18:283-90. 10.1016/j.numecd.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Munter JSL, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, Franz M, van Dam RM. Whole grain, bran, and germ intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study and systematic review. PLoS Med 2007;4:e261. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aune D, Chan DSM, Lau R, et al. Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2011;343:d6617. 10.1136/bmj.d6617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Franz M, Sampson L. Challenges in developing a whole grain database: Definitions, methods and quantification. J Food Compos Anal 2006;19 10.1016/j.jfca.2005.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jacobs DR, Jr, Gallaher DD. Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: a review. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2004;6:415-23. 10.1007/s11883-004-0081-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kamal-Eldin A, Lærke HN, Knudsen K-EB, et al. Physical, microscopic and chemical characterisation of industrial rye and wheat brans from the Nordic countries. Food Nutr Res 2009;53:1912. 10.3402/fnr.v53i0.1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Slavin JL. Mechanisms for the impact of whole grain foods on cancer risk. J Am Coll Nutr 2000;19(Suppl):300S-7S. 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Slavin J. Why whole grains are protective: biological mechanisms. Proc Nutr Soc 2003;62:129-34. 10.1079/PNS2002221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cho SS, Qi L, Fahey GC, Jr, Klurfeld DM. Consumption of cereal fiber, mixtures of whole grains and bran, and whole grains and risk reduction in type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:594-619. 10.3945/ajcn.113.067629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kochar J, Djoussé L, Gaziano JM. Breakfast cereals and risk of type 2 diabetes in the Physicians’ Health Study I. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:3039-44. 10.1038/oby.2007.362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun Q, Spiegelman D, van Dam RM, et al. White rice, brown rice, and risk of type 2 diabetes in US men and women. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:961-9. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA 2004;292:927-34. 10.1001/jama.292.8.927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fung TT, Malik V, Rexrode KM, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sweetened beverage consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1037-42. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jensen MK, Koh-Banerjee P, Hu FB, et al. Intakes of whole grains, bran, and germ and the risk of coronary heart disease in men. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:1492-9. 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koh-Banerjee P, Franz M, Sampson L, et al. Changes in whole-grain, bran, and cereal fiber consumption in relation to 8-y weight gain among men. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:1237-45. 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, et al. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: the effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18:858-67. 10.1093/ije/18.4.858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sun Q, Townsend MK, Okereke OI, Franco OH, Hu FB, Grodstein F. Physical activity at midlife in relation to successful survival in women at age 70 years or older. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:194-201. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol 1994;23:991-9. 10.1093/ije/23.5.991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Willett W, Stampfer MJ, Bain C, et al. Cigarette smoking, relative weight, and menopause. Am J Epidemiol 1983;117:651-8. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology 1990;1:466-73. 10.1097/00001648-199011000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Giovannucci E, Colditz G, Stampfer MJ, et al. The assessment of alcohol consumption by a simple self-administered questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133:810-7. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Colditz GA, Martin P, Stampfer MJ, et al. Validation of questionnaire information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. Am J Epidemiol 1986;123:894-900. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, et al. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr 2012;142:1009-18. 10.3945/jn.111.157222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Diabetes Data Group Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes 1979;28:1039-57. 10.2337/diab.28.12.1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. American Diabetes Association Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 1997;20(suppl 1):1183-97. 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2010 [correction in: Diabetes Care 2010;33:692]. Diabetes Care 2010;33(Suppl 1):S11-61. 10.2337/dc10-S011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Manson JE, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, et al. Physical activity and incidence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. Lancet 1991;338:774-8. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90664-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hu FB, Leitzmann MF, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Physical activity and television watching in relation to risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in men. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1542-8. 10.1001/archinte.161.12.1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rich-Edwards JW, Corsano KA, Stampfer MJ. Test of the National Death Index and Equifax Nationwide Death Search. Am J Epidemiol 1994;140:1016-9. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm E, et al. Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: a comparison of approaches for adjusting for total energy intake and modeling repeated dietary measurements. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149:531-40. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bernstein AM, Rosner BA, Willett WC. Cereal fiber and coronary heart disease: a comparison of modeling approaches for repeated dietary measurements, intermediate outcomes, and long follow-up. Eur J Epidemiol 2011;26:877-86. 10.1007/s10654-011-9626-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu GF, Wang J, Liu K, Snavely DB. Confidence intervals for an exposure adjusted incidence rate difference with applications to clinical trials. Stat Med 2006;25:1275-86. 10.1002/sim.2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley, 1987. 10.1002/9780470316696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aune D, Norat T, Romundstad P, Vatten LJ. Whole grain and refined grain consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2013;28:845-58. 10.1007/s10654-013-9852-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schulze MB, Schulz M, Heidemann C, Schienkiewitz A, Hoffmann K, Boeing H. Fiber and magnesium intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:956-65. 10.1001/archinte.167.9.956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.FoodData Central. USDA Food Agricultural Research Service. 2019. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/

- 46. Bhupathiraju SN, Tobias DK, Malik VS, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from 3 large US cohorts and an updated meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:218-32. 10.3945/ajcn.113.079533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Foster-Powell K, Holt SHA, Brand-Miller JC. International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2002. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:5-56. 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Popcorn Board. Industry Facts. https://www.popcorn.org/Facts-Fun/Industry-Facts.

- 49. Holt SHA, Miller JC, Petocz P, Farmakalidis E. A satiety index of common foods. Eur J Clin Nutr 1995;49:675-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nguyen V, Cooper L, Lowndes J, et al. Popcorn is more satiating than potato chips in normal-weight adults. Nutr J 2012;11:71. 10.1186/1475-2891-11-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.NOVA. Butter Lovers - ACT II - 12 bags * 78 g. https://world.openfoodfacts.org/product/0076150232301/butter-lovers-act-ii.

- 52.NOVA. Jolly Time Microwave Pop Corn - 300 g. https://world.openfoodfacts.org/product/0028190007944/jolly-time-microwave-pop-corn.

- 53.NOVA. Butter flavored Popcorn - Jiffy pop - 4.5 oz. https://world.openfoodfacts.org/product/0064144150502/butter-flavored-popcorn-jiffy-pop.

- 54. Otite FO, Jacobson MF, Dahmubed A, Mozaffarian D. Trends in trans fatty acids reformulations of US supermarket and brand-name foods from 2007 through 2011. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E85. 10.5888/pcd10.120198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang Q, Imamura F, Ma W, et al. Circulating and dietary trans fatty acids and incident type 2 diabetes in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Diabetes Care 2015;38:1099-107. 10.2337/dc14-2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Moreta C, Tena MT. Determination of perfluorinated alkyl acids in corn, popcorn and popcorn bags before and after cooking by focused ultrasound solid-liquid extraction, liquid chromatography and quadrupole-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2014;1355:211-8. 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Martínez-Moral MP, Tena MT. Determination of perfluorocompounds in popcorn packaging by pressurised liquid extraction and ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta 2012;101:104-9. 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lind PM, Salihovic S, van Bavel B, Lind L. Circulating levels of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and carotid artery atherosclerosis. Environ Res 2017;152:157-64. 10.1016/j.envres.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lind L, Zethelius B, Salihovic S, van Bavel B, Lind PM. Circulating levels of perfluoroalkyl substances and prevalent diabetes in the elderly. Diabetologia 2014;57:473-9. 10.1007/s00125-013-3126-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Liu G, Dhana K, Furtado JD, et al. Perfluoroalkyl substances and changes in body weight and resting metabolic rate in response to weight-loss diets: A prospective study. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002502. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sun Q, Zong G, Valvi D, Nielsen F, Coull B, Grandjean P. Plasma concentrations of perfluoroalkyl substances and risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective investigation among U.S. women. Environ Health Perspect 2018;126:037001. 10.1289/EHP2619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bes-Rastrollo M, Sanchez-Villegas A, Basterra-Gortari FJ, Nunez-Cordoba JM, Toledo E, Serrano-Martinez M. Prospective study of self-reported usual snacking and weight gain in a Mediterranean cohort: the SUN project. Clin Nutr 2010;29:323-30. 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mekary RA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, van Dam RM, Hu FB. Eating patterns and type 2 diabetes risk in men: breakfast omission, eating frequency, and snacking. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:1182-9. 10.3945/ajcn.111.028209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary material