Abstract

A new class of dominant dark skin (Dsk) mutations discovered in a screen of ~30,000 mice is caused by increased dermal melanin. We identified three of four such mutations as hypermorphic alleles of Gnaq and Gna11, which encode widely expressed Gαq subunits, act in an additive and quantitative manner, and require Ednrb. Interactions between Gq and Kit receptor tyrosine kinase signaling can mediate coordinate or independent control of skin and hair color. Our results provide a mechanism that can explain several aspects of human pigmentary variation and show how polymorphism of essential proteins and signaling pathways can affect a single physiologic system.

Understanding the genetic basis of quantitative phenotypes has challenged biologists for more than 80 years, with theories outpacing specific examples of the underlying molecular architecture. We are investigating variation in mouse skin color as a model for other quantitative traits and as an entry point for studying basic aspects of cell and developmental biology. Genetic studies of skin color examine developmental mechanisms at the time when melanoblasts, pigment cell precursors migrating from the neural crest, are sorted into three alternative locations: the dermis, the epidermis and the hair follicles1.

Until recently, there were few opportunities to study skin color with a phenotype-driven approach. Large-scale chemical mutagenesis screens have now identified a large and previously unnoticed class of pigmentation mutants with dark skin2–4. In our initial characterization, ten dominant dark skin (Dsk) mutants were placed into two distinct groups depending on whether pigment accumulated in the dermis or the epidermis5. This indicated that epidermal and dermal melanocyte populations could be regulated independently by distinct sets of genetic pathways.

Among the dermal class of dark skin mutations, Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 are phenotypically indistinguishable. Here we report that these three mutations represent gain-of-function alterations in two genes encoding G-protein α—subunits: Gnaq (Dsk1 and Dsk10) and Gna11 (Dsk7). These findings provide new insight into G-protein signaling during mammalian development and help to explain how hair and skin color can be controlled both coordinately and independently.

RESULTS

Unique features of Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10

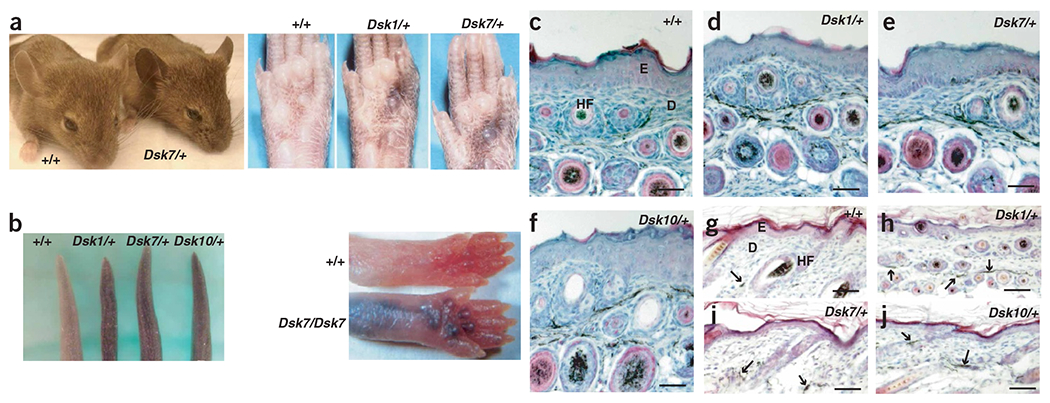

Dsk1, Dsk7, and Dsk10 were discovered during a large-scale mutagenesis screen of inbred C3HeB/FeJ mice5. Increased pigmentation is semidominant and obvious in the ears, footpads and tails of adult mice (Fig. 1a). Histological analysis indicated that excess dermal melanin is present not only in the tail (Fig. 1c–f) and ears (data not shown), but also in the hair-bearing skin (Fig. 1g–j). The mutant phenotype is maintained throughout adulthood but is first apparent and most obvious in neonates (Fig. 1b), because progressive accumulation of epidermal melanin that begins after birth tends to obscure the dermal pigmentary differences. The extent and pattern of darkening of nonhairy skin, the increased pigmentation of the hair-bearing skin and the time of onset are unique features that distinguish Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 mutants from the other Dsk mutants.

Figure 1.

Morphologic and histologic characteristics of mice heterozygous with respect to Dsk1, Dsk7 or Dsk10. (a) Adult mice can be recognized by dark skin on the ears, tails or footpads, and the pattern of footpad pigmentation is identical for the three mutations (Dsk10 not shown). The footpad images were published previously5. (b) Tail and foot pigmentation 5 d after birth. (c–j) Tail (c–f) and dorsal trunk (g–j) skin from 5-d-old mice of the indicated genotypes. Melanin in the sections appears black. Arrows indicate extrafollicular dermal melanin. Scale bars: c–j, 50 μm. E, epidermis; D, dermis; HF, hair follicle.

Positional cloning of Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10

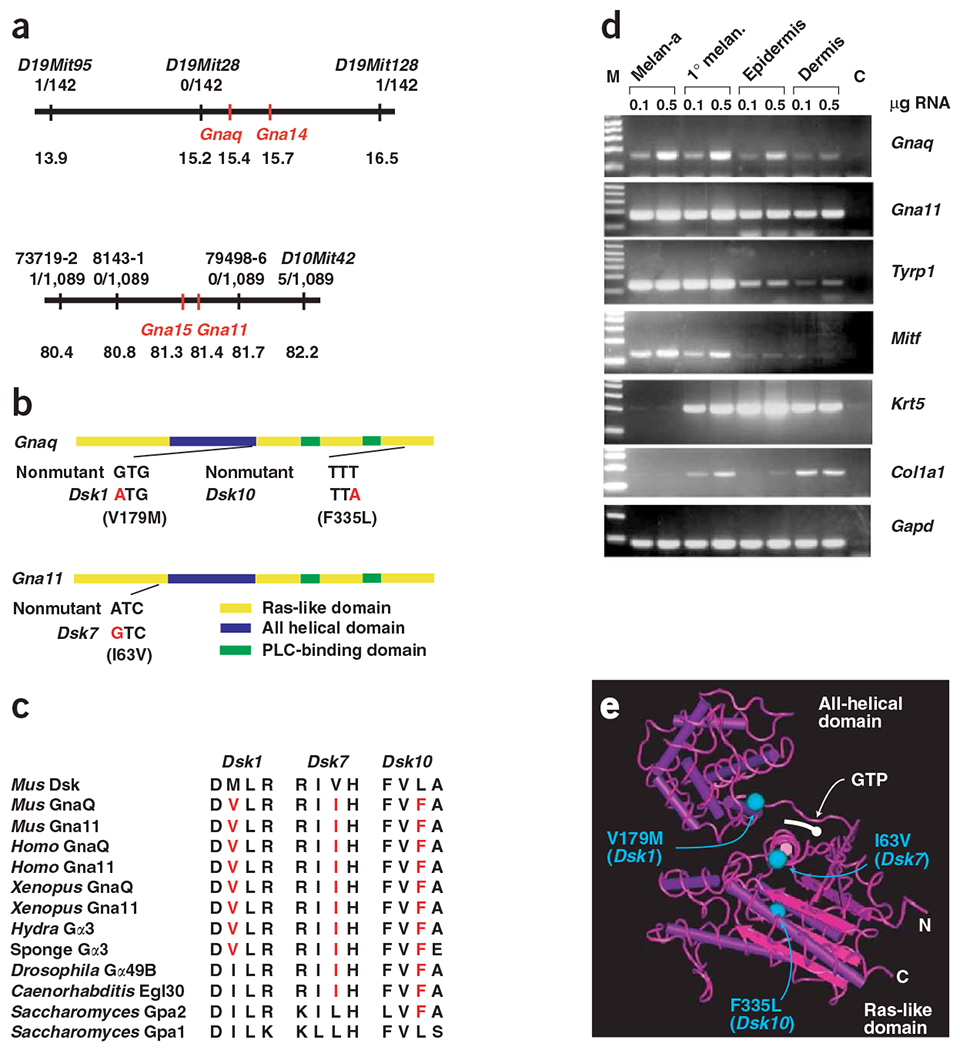

Dsk1, Dsk7, and Dsk10 were localized initially to intervals of 6.9 cM (chromosome 19), 8.6 cM (chromosome 10) and 10 cM (chromosome 19), respectively, with overlap between the Dsk1 and Dsk10 intervals suggestive of possible allelism5. To identify the causative mutations, we narrowed the intervals for Dsk1 and Dsk7 to 2.6 Mb and 1.8 Mb, respectively (according to Ensembl v5.3.1; ref. 6), identifying 21 candidate genes for Dsk1 and 65 candidate genes for Dsk7 (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Positional cloning of Dsk mutations. (a) Genetic and physical maps of the Dsk1 (chromosome 19; top) and Dsk7 (chromosome 10; bottom) intervals. For each SSLP marker, the number of recombinants and number of mapping progeny are recorded. Below this, the position on the current Ensembl mouse genomic assembly is shown (in Mb). (b) The positions and sequences of the point mutations Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 are shown on a graphic representation of the Gnaq and Gna11 transcripts. The locations of the main protein domains are marked. (c) The amino acid substitutions for the mutations Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 are shown, along with the nonmutant sequences of mouse Gnaq and Gna11 and the sequences from homologs in other species, including Homo sapiens, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Caenorhabditis elegans. (d) Expression of Gnaq and Gna11 mRNA relative to that of genes specific for different components of the skin was determined by RT-PCR of mRNA purified from melan-a cells, primary melanocytes cultured from neonatal skin and neonatal dermis and epidermis separated by treatment with trypsin. M, molecular weight markers (1-kb ladder); C, control (no cDNA). (e) The positions of the mutations are projected onto the structure of Gαs described in ref. 12. Dsk7 (I63V) lies in α1 of the ras domain, Dsk1 (V179M) lies in αF of the all-helical domain, and Dsk10 (P335L) lies towards the end of the protein in α5.

Because the appearance of Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 mutants is identical, we compared the candidate gene lists and noticed that two members of the Q class of G-protein α subunits were present in each of the intervals. Gαq subunits mediate the ‘classical’ pathway for coupling receptors to phospholipase Cβ7 and, in vertebrates, form two subgroups, the widely expressed q/11 group and the more restricted 14/15 group8–10.

We sequenced these four Gna genes and identified a single-nucleotide substitution in each of the mutants that was not present in the strain of origin. These substitutions predict protein-coding changes: V179M (Gnaq, Dsk1), I63V (Gna11, Dsk7) or F335L (Gnaq, Dsk10; Fig. 2b).

Each of these substitutions affects residues that are evolutionarily conserved within and between Gnaq and Gna11 orthologs in vertebrates, as well as in Gαq homologs of primitive multicellular organisms (Fig. 2c). At the dosage of ethylnitrosourea used (predicted to produce ~0.5 changes per Mb; ref. 11), we estimate there should be only approximately one to three nucleotide substitutions in the intervals to which Dsk1 and Dsk7 were mapped. We measured expression of Gnaq and Gna11 by RT-PCR and detected mRNA for both genes in cultured primary and immortalized melanocytes and in dermal and epidermal preparations of neonatal skin (Fig. 2d). Taken together with the observation that three independent mutations with identical phenotypes have nucleotide alterations in the same gene or gene family, and the genetic interaction data described below, we conclude that Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 are point mutations in Gαq class subunits.

We used the crystal structure for Gαs to predict the location of the Dsk mutations12. Dsk1 in Gnaq (V179M) lies in the all-helical domain (αF) adjacent to switch region I and, therefore, might affect GTPase activity or GTP binding (Fig. 2e). The locations of the other Dsk mutations are spatially distinct and do not suggest obvious mechanisms of action.

Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 are hypermorphic

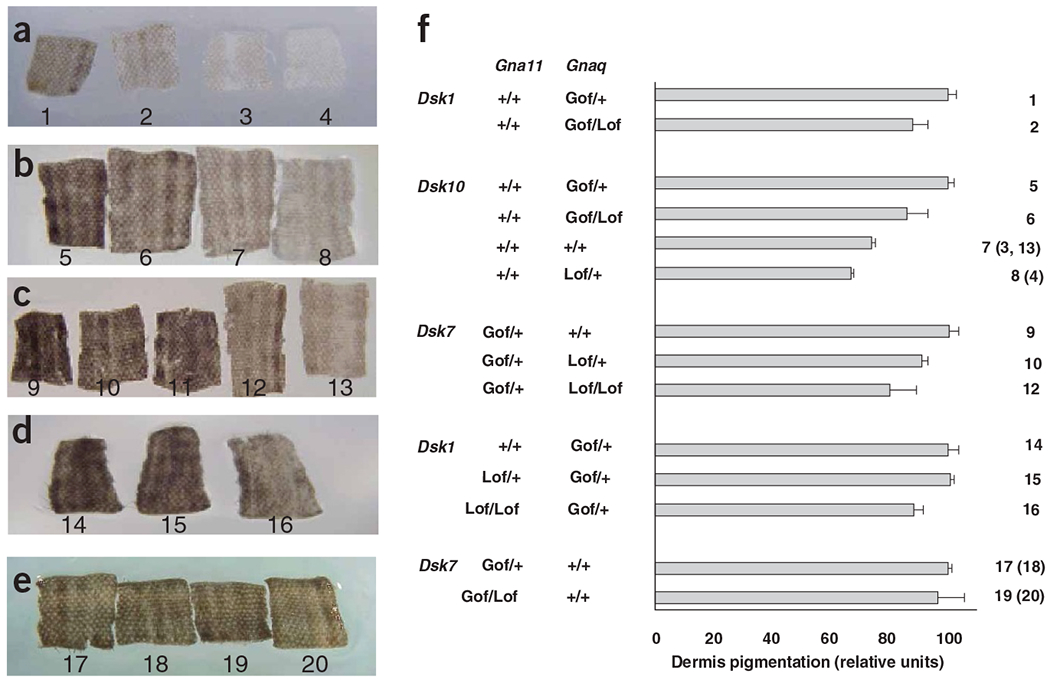

To investigate whether the Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 mutations increased activity, decreased activity or generated new activity in the resultant protein, we crossed mice carrying these mutations with mice carrying previously constructed knockout (GnaqKO or Gna11KO) alleles13,14. Using a quantitative assay for the extent of dermal pigmentation, we determined that a single GnaqKO allele reduced dermal pigmentation caused by a single Dsk1, Dsk7 or Dsk10 allele (P = 0.00064; Fig. 3a–c,f). A single Gna11KO allele had no effect on skin darkening (Fig. 3d–f), but two Gna11KO alleles reduced dermal pigmentation caused by Dsk1 (P = 0.033; Fig. 3d,f).

Figure 3.

Interaction of Gnaq and Gna11 knockout mutations with Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10. (a–e) Representative samples of tail dermis from 3-week-old mice. (f) The average pixel intensity of each genotype was normalized to the average of the Dsk heterozygotes in each cross, which was set at 100. Genotypes, shown below tails in a–e and to the right of the histogram in f, are as follows: 1, GnaqDsk1/+; 2, GnaqDsk1/KO; 3, +/+; 4, GnaqKO/+; 5, GnaqDsk10/+; 6, GnaqDsk10/KO; 7, +/+; 8, GnaqKO/+; 9, Gna11Dsk7/+; 10, Gna11Dsk7/+ GnaqKO/+; 11, Gna11Dsk7/KO GnaqKO/+; 12, Gna11Dsk7/+ GnaqKO/KO; 13, +/+; 14, GnaqDsk1/+; 15, GnaqDsk1/+ Gna11KO/+; 16, GnaqDsk1/+ Gna11KO/KO; 17,18, Gna11Dsk7/+; 19,20, Gna11Dsk7/KO. Lof, loss-of-function (knockout alleles); Gof, gain-of-function (Dsk alleles).

We also noticed that heterozygous GnaqKO mice had a lighter dermis than their normal littermates, a phenotype that was obscured in the whole mouse by a normally pigmented epidermis (P = 0.0025; Fig. 3a,b,f). In contrast, heterozygous Gna11KO mice did not have an obvious change in dermis pigmentation (data not shown). These results indicate that the three Dsk mutations are hypermorphic, with effects exactly opposite to that caused by reduced gene dosage. Normal skin color is more sensitive to reduced dosage of Gnaq than to reduced dosage of Gna11, but the two genes must function cooperatively, as knock-out of one can ameliorate a hypermorphic mutation in the other gene.

These results also speak to the relative strength of the mutations in terms of gene dosage. Mice hemizygous with respect to any of the three Dsk alleles were intermediate in phenotype between wild-type mice and single heterozygotes (GnaqDsk10/+ > GnaqDsk10/KO > Gnaq+/+), which suggests that the activity of a single Dsk allele is greater than that of two copies of the normal allele.

Dsk1 and Dsk7 act additively and quantitatively

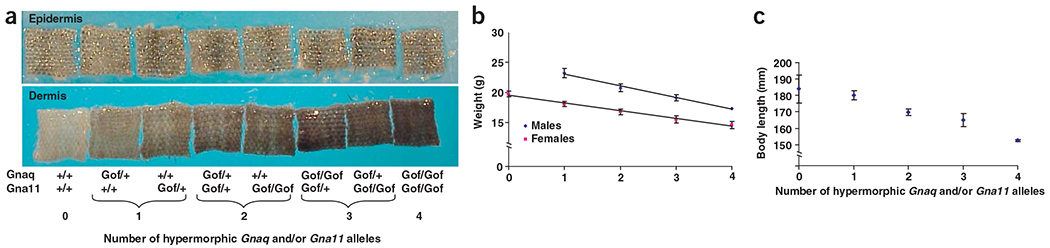

To determine the effect of progressively increasing total Gαq signaling, we generated mice carrying both Dsk1 and Dsk7 mutations (Fig. 4). Dermal pigmentation increased progressively and in a step-wise manner in mice carrying zero, one, two, three and four Dsk alleles in any combination (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

Additive effects of Gαq activity on pigmentation and body size. (a) Tail epidermis (top) and dermis (bottom) from 3-week-old Dsk1 and Dsk7 mice on an isogenic background. The number of gain-of-function (Gof) Dsk1 and Dsk7 alleles is indicated for each sample, which is representative of at least three mice. (b) The linear relationship between average body weight and the number of Dsk1 and Dsk7 alleles on a mixed genetic background is shown for 6-week-old males and females. (c) The relationship between body length and the number of Dsk1 and Dsk7 alleles is shown for 36-week-old females.

In examining mutant mice for additional phenotypes, we found that double homozygotes appeared grossly normal but small. Increasing the number of mutated alleles caused a progressive and linear decrease in body mass at 6 weeks of age (Fig. 4b; linear regression analysis, P < 0.0001). In a cohort of mice aged to 36 weeks, the linear relationship between body weight and number of Dsk alleles persisted (data not shown); these mice also had a progressive decrease in body length (Fig. 4c). Increasing numbers of Dsk1 or Dsk7 mutations had no effect on the relative amount of lean body mass (zero mutations, 61.4 ± 5.5%; one mutation, 62.1 ± 3.1%; two mutations, 63.6 ± 2.6%; three mutations, 62.8 ± 5.2%; four mutations, 60.7 ± 3.0%), suggestive of a general effect on cell number or size rather than a perturbation of intermediary metabolism or energy homeostasis. These observations indicate that Gnaq and Gna11 act additively and quantitatively, with the extent of Gαq activity read with unexpected precision by downstream signaling components.

Developmental mechanism of Dsk1 and Dsk7 action

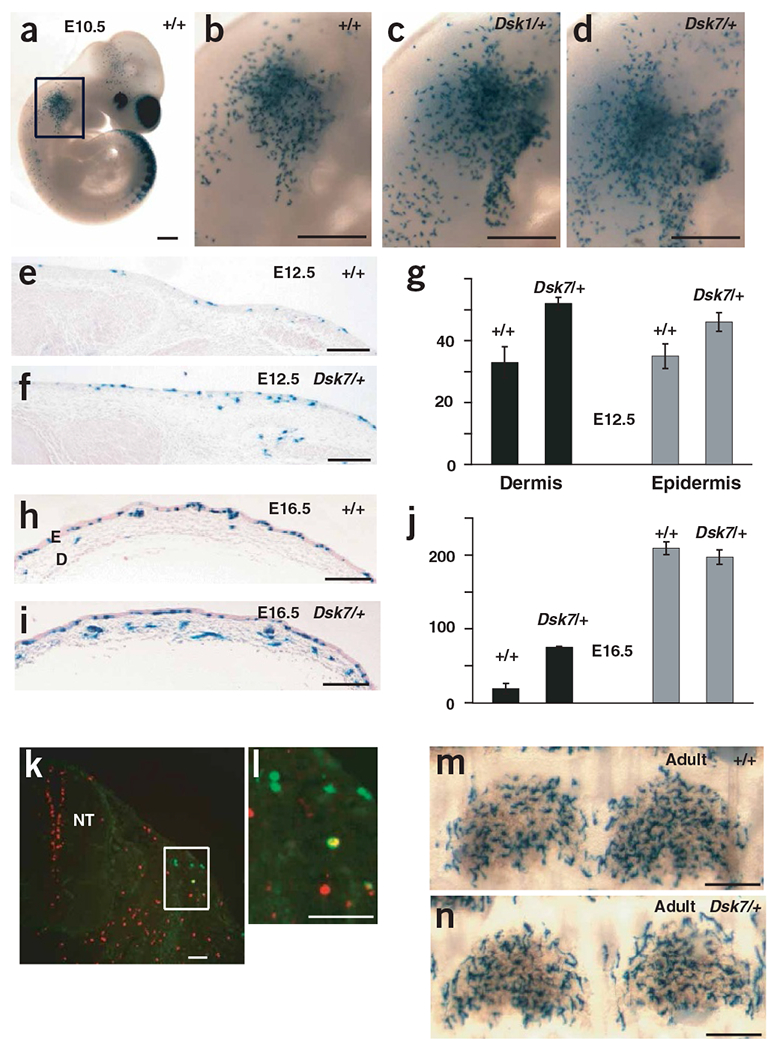

To determine whether increased pigmentation in Dsk1 and Dsk7 mutants represents a difference in pigment cell number or pigment production, we made use of a lacZ reporter gene controlled by regulatory sequences from the gene Dct (also called Tyrp2). Between embryonic day (E) 10 and E16.5, melanoblasts migrate from the neural crest to the dermis, and then to the epidermis15–17. The Dct-lacZ transgene is expressed in melanoblasts as soon as they leave the neural crest and persists through most developmental stages and in epidermal melanocytes17,18.

We observed more lacZ-positive cells in GnaqDsk1/+ and Gna11Dsk7/+ embryos beginning at the earliest stage at which melanoblasts can be detected (E10.5; Fig. 5a–j). At E12.5, lacZ-positive cells were more numerous in both the dermis and the epidermis of mutant embryos, but by E16.5, the nonmutant cell number caught up to the number of the mutants in the epidermis (Fig. 5e–j). This time period corresponds to a main period of epidermal development, the appearance of a stratified epithelium19,20; thus, events inherent to this process may actively regulate the density of melanocytes ‘permitted’ in the epidermis.

Figure 5.

Developmental mechanism by which dark skin is caused by increased Gαq activity. (a–f,h–i) X-gal-stained Dct-lacZ transgenic embryos and skin samples from mice of the indicated ages and genotypes. Each image is representative of at least three mice or embryos. E, epidermis; D, dermis. (g) The number of lacZ-positive cells per cm of section in the dermis and epidermis of E12.5 wild-type (+/+) and Gna11Dsk7/+ embryos, as measured in the anterior-most flank skin. The lacZ-positive cells directly adjacent to the exterior were considered to be located in the single cell-layered epidermis. (j) The number of lacZ-positive cells per cm of section in the dermis and epidermis of E16.5 wild-type (+/+) and Gna11Dsk7/+ embryos, as measured in the mid-back dorsal skin. At this stage, the epidermis has differentiated into a thickened layer, as indicated. (k,l) An E11.5 Dct-lacZ transgenic embryo sectioned and incubated with fluorescently labeled antibodies: antibody to phosphorylated histone H3 (red) and antibody to β-galactosidase (green). A doubly labeled cell (yellow) is visible in l. NT, neural tube. (m,n) Tail epidermal sheets from 3-week-old mice. There was no significant difference in the number of epidermal lacZ-positive cells per scale (79 ± 3 and 72 ± 4 for wild-type and Gna11Dsk7/+ mice, respectively). Scale bars: a–d, 500 μm; e,f,h,i,m,n, 200 μm; k,l, 50 μm.

To look for the underlying cause of the increased number of lacZ-positive cells, we measured the mitotic index and extent of apoptosis in lacZ-positive cells of GnaqDsk1/+, Gna11Dsk7/+ and wild-type embryos carrying the Dct-lacZ transgene (Fig. 5k–l). At E11.5, we found no difference in mitotic index (Table 1) or TUNEL staining (data not shown). We also observed no effect of Dsk1 or Dsk7 on dorsoventral migration, as judged by the position of the migrating ventral edge of lacZ-positive cells (data not shown). These observations suggest that increased Gq signaling may act by increasing the number of neural crest cells that differentiate into melanoblasts.

Table 1.

Pigment cell number and proliferation at E11.5

| Characteristic | Genotype | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | GnaqDsk1/+ | Gna11Dsk7/+ | |

| Number of pigment cells per section | 7.9 ± 1.3 | 18.0 ± 7.2 | 14.8 ± 6.7 |

| Percentage of pigment cells in mitosis | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.5 |

| Number of embryos examined | 7 | 4 | 5 |

Embryos carrying the Dct-lacZ transgene were doubly labeled with fluorescent antibodies: an antibody to β-galactosidase, which labels melanocytes, and an antibody to phosphorylated histone H3, which labels cells in mitosis. Results are given as mean ± s.e.m.

Adult GnaqDsk1/+ (data not shown) and Gna11Dsk7/+ mutants had the same number of lacZ-positive cells in the tail epidermis as did wild-type mice (Fig. 5m,n), even though increased dermal pigmentation persisted (Figs. 3 and 4). Taken together, these observations indicate that the fundamental defect of Dsk1 or Dsk7 that causes dark skin is a doubling of the melanoblast population (Table 1) before E10.5. The expanded melanoblast population is otherwise normal, and the dermal specificity of the dark skin phenotype is a secondary effect of mechanisms intrinsic to the developing epidermis.

Requirement for Ednrb but not Kit

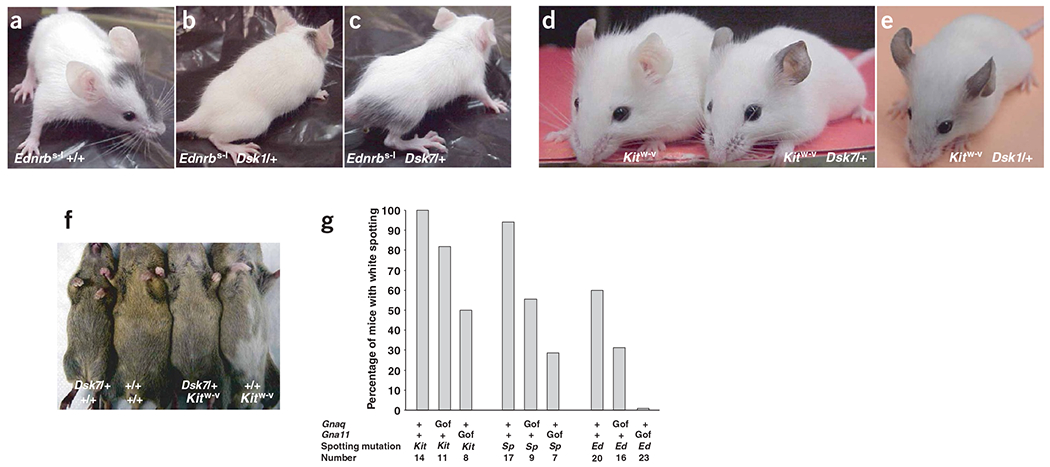

In principle, hypermorphic mutations of Gnaq and Gna11 could result in constitutive activation independent of a seven-transmembrane receptor or hyperactivation when signaling is initiated normally. To test this possibility in vivo, the receptor(s) that normally couple to Gq during pigmentary development must be identified. One of the best candidates is the endothelin receptor B (Ednrb), which is required for normal pigmentation between E10 and E12.5 (ref. 21). We generated Ednrbs-l/s-l GnaqDsk1/+ and Ednrbs-l/s-l Gna11Dsk7/+ double mutants and found that they were indistinguishable from Ednrbs-l/s-l single mutant littermates (Fig. 6a–c).

Figure 6.

Rescue of white-spotting mutations by Dsk1 or Dsk7. (a–c) Ednrbs–l/s–l, Ednrbs–l/s–l GnaqDsk1/+ and Ednrbs–l/s–l Gna11Dsk7/+ mice. (d,e) Kitw–v/w–v, Kitw–v/w–v Gna11Dsk7/+and Kitw–v/w–v GnaqDsk1/+ mice. Mice shown are representative of more than five of each genotype. (f) Representative 5-week-old progeny from a cross between Gna11Dsk7/+ and Kitw–v/+ mice. (g) The percentage of mice with white belly hair is indicated for each genotype. Gof, gain-of-function (Dsk1 and Dsk7 alleles); Kit, Kitw–v; Sp, Pax3Splotch; Ed, Ednrbss–l.

The requirement of Dsk1 or Dsk7 for Ednrb is not caused by a block in melanocyte development, because additional crosses to mice carrying a loss-of-function mutation in the Kit receptor tyrosine kinase gene showed that Dsk1 or Dsk7 could partially rescue the more severe deficit of melanocytes observed in Kitw-v/w-v mice22. Double-mutant Kitw-v/w-v GnaqDsk1/+ or Kitw-v/w-v Gna11Dsk7/+ mice lack all hair pigmentation but have conspicuous dark ear skin (Fig. 6d,e), which was never observed in Kitw-v/w-v littermates. Thus, the mechanism by which Dsk1 and Dsk7 act depends on a functional receptor. This indicates that endothelin signaling is the main mediator of the Dsk1 and Dsk7 mutant phenotype.

Signaling pathway interactions

Because Dsk1 and Dsk7 increase Gq activity, they provide a unique opportunity to investigate how different signaling pathways interact to modulate hair and skin pigmentation. Many white-spotting mutations are thought to act by compromising the proliferation or survival of melanoblasts, such that progenitor pools are exhausted before migration is complete23–26. If this is the case, the increased number of early melanoblasts caused by Dsk1 and Dsk7 mutations might rescue white spotting, regardless of the underlying cause.

We found that Dsk1 or Dsk7 decreased the proportion of white-spotted mice among mice heterozygous with respect to Kitw-v, Ednrbs-l or Pax3Splotch (Fig. 6f,g). Pax3Splotch/+ and Ednrbs-l/+ mice were rescued more effectively than Kitw-v/+ mice, and in each case, Dsk7 was more effective at rescuing white spotting than Dsk1 (Fig. 6g). These results confirm that Dsk1 and Dsk7 promote expansion of the early melanoblast population, and indicate that in conditions where melanoblast number is limiting, increased Gq signaling can promote hair and skin pigmentation.

DISCUSSION

Gnaq and Gna11 encode two of the four members of the Gαq subunit class, the ‘classical’ pathway for coupling seven transmembrane receptors to phospholipase Cβ7. Gain-of-function mutations of GNAS have been described as genetic mosaics in the human condition McCune-Albright syndrome and in neuroendocrine tumors27,28. In C. elegans, three hypermorphic alleles of the Gαq homolog, egl-30, have been isolated in suppressor screens29,30. Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 are the first examples of hypermorphic Gq mutations in vertebrates and the first hypermorphic mutations of any Gα subunit recognized in the vertebrate germ line.

Theoretically, increased Gαq activity could be caused by specific alterations that increase affinity for GTP, the receptor, the effector or accessory proteins, or by nonspecific alterations that disrupt Gαq structure and impair intrinsic GTPase activity. Because the six hypermorphic mutations (three from mouse and three from worm) lie in different regions, a nonspecific mechanism (reduced GTPase activity) seems more likely.

Gnaq and Gna11 are widely expressed, but expression of Ednrb during pigment cell development occurs mainly in melanoblasts rather than their surrounding cells31,32. Because Dsk1 and Dsk7 depend on a functional Ednrb gene, and because Ednrb couples to Gαq proteins, we believe that Dsk-induced dermal melanocytosis occurs through a cell-autonomous mechanism in which amplification of normal endothelin signaling through mutant Gq subunits causes an excess number of early melanoblasts. Recent organ culture studies, however, suggest that a non–cell autonomous mechanism is possible, as Ednrb-deficient pigment cells can be partially rescued by coculture with nonmutant neural tubes or exogenous Kit ligand33.

Increased Gq signaling in pigment cells may also underlie dermal hyperpigmentation and melanocytic tumors that develop in transgenic mice in which a metabotropic glutamate receptor, Grm1, is driven by the Dct promoter34. Finally, dermal melanocytosis has been described35 in transgenic mice in which hepatocyte growth factor (Hgf) is controlled by the keratin 14 promoter. The Hgf receptor is a tyrosine kinase that does not couple directly to Gq subunits, but its activation could intersect with that of Ednrb or Grm1 signaling in pigment cells.

We expected to find additional phenotypes in Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 mutants, as our quantitative analysis suggested that each Dsk mutation more than doubles the effective gene dosage9,14. By contrast, even moderate gain- and loss-of-function alleles of egl-30 have more substantial effects30,36. This apparent difference—in which a mammal is better able than an invertebrate to buffer changes in Gαq activity—might be explained by more complex regulation of G-protein signaling. As a corollary, the sensitivity of skin color to Gαq gene dosage may indicate that pigment cells rely more on the intrinsic GTPase activity of Gα subunits than do other cells. If so, we expect Dsk mutants to have pleiotropic phenotypes if one or more GAP genes are deleted, as Gq signaling is increased past the buffering capabilities of the pathway. For example, an increase of Gnaq expression in the mouse heart by a factor of more than 4 causes cardiac hypertrophy37.

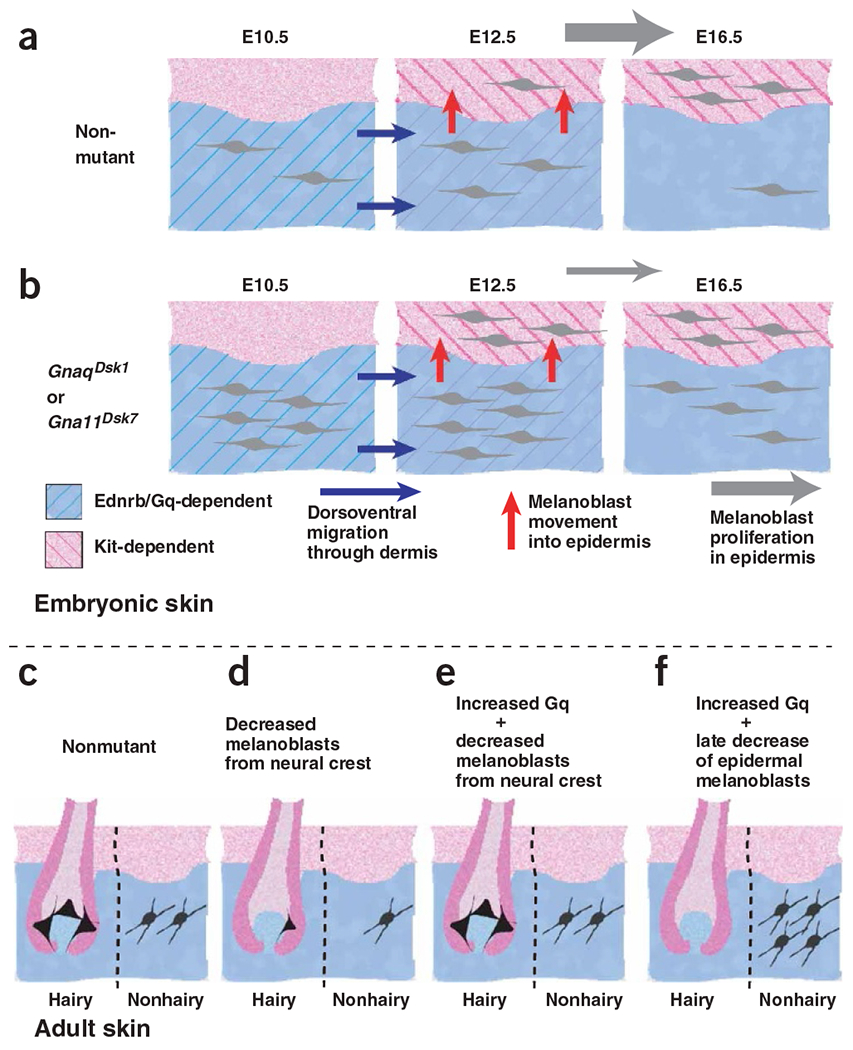

In species with a broad range of pigmentary variation, such as humans and domestic mice, there is a strong correlation between dark skin and dark hair. Together with earlier work on Kit and Ednrb signaling21,38,39, our studies of Gnaq and Gna11 mutations show how these traits can be controlled both coordinately and independently (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Coordinate and independent control of hair and skin color. (a) Neural crest–derived melanoblasts migrate ventrally through the embryonic dermis between E10 and E12.5; this process is dependent on Ednrb21 and on Gq activity. Starting at E12.5, melanoblasts move from the embryonic dermis to the epidermis and then proliferate extensively in the epidermis. (b) Hypermorphic mutations of Gnaq or Gna11 result in more early melanoblasts by E10.5 in the dermis and more epidermal melanoblasts at E12.5. By E16.5, the number of epidermal melanoblasts in nonmutant mice has caught up to the number in Dsk1 or Dsk7 mutants. (c,d) Fewer early melanoblasts, as would result from loss-of-function mutations in Ednrb or Gnaq, gives rise to white spotting or decreased dermal pigmentation, respectively. (e) Hypermorphic mutations of Gnaq or Gna11 can rescue white spotting caused by a reduced number of neural crest–derived melanoblasts, but have no effect (f) if white spotting is caused by a late decrease in the number of epidermal melanoblasts.

The earliest steps in melanoblast differentiation occur before E10 and depend on Kit, but not Ednrb, signaling21,38–41. The situation is reversed between E10 and E12.5, when Ednrb, but not Kit, is required as melanoblasts migrate within the embryonic dermis. In a penultimate step, melanoblasts enter the epidermis between E12.5 and E16.5 and undergo additional rounds of proliferation, during which time Kit is again required, but Ednrb is not.

Our results show that increased Gq signaling acts before E10.5 to produce more early melanoblasts (Fig. 7). The effects appear in both the embryonic dermis and epidermis, but the dermis permits a permanent increase in melanoblast number whereas the epidermis does not (Fig. 7a,b). An independent effect on hair and skin color is most readily apparent under conditions where survival of epidermal melanoblasts is compromised, leading to dark skin in the absence of hair pigmentation (Fig. 7f; see also Fig. 6d,e).

An important goal of large-scale mutagenesis studies currently underway is to increase the repertoire of genes implicated in specific physiologic processes, with the underlying assumption that genotype-phenotype correlations for most morphogenetic pathways are far from saturation. Given that Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 are three of the four dermal dark skin mutations recovered from a screen of ~30,000 mice, it is notable that all three act by increasing the activity of Gαq subunits. This fact suggests that dermal melanocytosis is a phenotypic signature for increased signaling through receptors that activate phospholipase Cβ.

Gnaq and Gna11 arose early in vertebrate evolution and are coexpressed in most tissues9,10. In crosses with knockout alleles, reduction of gene dosage from four to two copies has little effect in tissues where both genes are expressed, but further reduction is lethal14. This threshold effect has been interpreted as genetic overlap, in which more copies of Gnaq and Gna11 exist than are necessary. But the observation that Dsk mutations act additively on pigmentation and body size indicates that, at least for these two characteristics, the exact amount of Gq signaling is critical and acts directly and quantitatively. The ability of downstream effectors to interpret the amount of Gαq activity and precisely transmit this information probably provided selective pressure against variation in gene dosage, and could represent a general theme in evolution of signal transduction proteins that couple transmembrane receptors to intracellular machinery.

METHODS

Mouse strains.

We generated Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 mutants on an isogenic C3HeB/FeJ background as previously described3,5. We crossed Gnaq and Gna11 knockout mice (provided by T. Wilkie, UT Southwestern, Dallas, Texas, USA)13,14 for two generations to C3HeB/FeJ mice. We obtained C57BL/6J mice, CAST/Ei mice and mice carrying Ednrbs-l, Kitw-v or Pax3Splotch from The Jackson Laboratory. We maintained Kitw-v and Pax3Splotch mice on a C57 background and Ednrbs-l mice on a SSL/Le background. We crossed mice carrying the Dct-lacZ reporter transgene (provided by M. Shin (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) with the permission of I. Jackson (MRC Human Genetics Unit, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, Scotland))24 for at least three generations to C3HeB/FeJ mice. All experiments were carried out under a protocol approved by the Stanford Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care.

Genotyping.

We genotyped Dsk1, Dsk7, Dsk10 or Pax3Splotch mice by digesting PCR-amplified fragments from tail or extraembryonic membrane DNA with a restriction enzyme (NspI, FokI DdeI or BsrI, respectively) that distinguished between the mutant and nonmutant fragments; primer sequences are available on request. We genotyped Gnaq and Gna11 knockout mice42 and Kitw-v mice24 as previously described. To detect the Ednrbs-l allele, which is a complete deletion of the Ednrb locus, we used a simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) marker located 1 cM from the Ednrb locus, D14Mit42, that distinguishes between the SSL/Le and C3HeB/FeJ alleles43.

Positional cloning of Dsk1 and Dsk7.

Linkage of Dsk1, Dsk7 and Dsk10 to chromosome 10 or chromosome 19 was described previously5. For Dsk1 and Dsk7, we used recombinants to narrow the genetic interval with additional SSLP markers with an outcross-backcross mapping strategy to either C57/BL6 mice (Dsk1) or CAST/Ei mice (Dsk7). In areas with no polymorphic Mit markers, we generated new SSLP markers that distinguished between C3HeB/FeJ and CAST/Ei sequences in the Gna11 interval with the following genome sequence coordinates (mm4, October 2003, National Center for Biotechnology Information build 32): marker 73719-2, chr 10: 82937910–82938055; marker 8143-1, chr 10: 83325512–83325696; 79498-6, chr 10: 84426706–84426815. We directly sequenced DNA from mutant and nonmutant tail tissue biopsies after PCR amplification. All mutations were confirmed using sequencing, PCR and restriction digestion of genomic DNA from three or more mutant mice and nonmutant littermates.

RT-PCR.

We isolated total RNA from melan-a cells, primary melanocytes, neonatal epidermis and neonatal dermis using Trizol (Invitrogen) and purified it using RNeasy (Qiagen). We then treated 100–500 ng of RNA with DNAseI before reverse transcription using Superscript II (Invitrogen). We diluted the cDNA products 40-fold before carrying out PCR. All primer sequences were designed to span introns and are available on request.

Histology and immunofluorescence.

We fixed dorsal trunk and tail skin from 5-d-old mice overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded tissues in paraffin, cut 8-μm sections and stained them with eosin and hematoxylin. For lacZ staining of embryos, we crossed C3HeB/FeJ GnaqDsk1/+ or Gna11Dsk7/+ mice with transgenic heterozygous Dct-lacZ mice in timed matings (with the day of the copulation plug designated E0.5). We fixed embryos between E10.5 and E16.5 for 1 h in 4% paraformaldehyde and then incubated them in X-gal staining solution overnight at room temperature with rocking. We embedded tissues in paraffin, cut 12-μm sections and counterstained them with eosin. For lacZ staining of adult tail epidermis, we removed a 1-cm length of tail, removed the skin and allowed it to adhere, epidermis side down, to a grease-coated glass slide and then incubated it overnight in X-gal staining solution. We then incubated the samples at 37 °C for 75 min in 2 M NaBr and peeled away the dermis using forceps.

For measurement of mitotic index, we recovered E11.5 embryos as described above, fixed them overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed them in 30% sucrose and then embedded them in OCT. We cut 50 transverse serial sections (12 μm) from each embryo, beginning with the first section containing forelimb, and stained them overnight at 4 °C with a monoclonal antibody against β-galactosidase (Promega, 1:500) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against phosphorylated histone H3 (Upstate, 1:200). We then incubated them with secondary antibodies, antibody to mouse conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate and antibody to rabbit conjugated to rhodamine (Jackson Immunoresearch, 1:63), for 1 h at room temperature. Using fluorescence microscopy, we counted at least 196 lacZ-positive cells for each embryo. For all experiments, we examined at least three embryos or mice and 50 sections of each genotype at each stage.

Weight and body composition assays.

We intercrossed GnaqDsk1/+ Gna11Dsk7/+ mice on a mixed (C3HeB/FeJ and C57BL/6J) background and weighed F1 or F2 progeny from 23 litters at 6 weeks of age. We allowed a cohort of females from ten litters to age to 36 weeks, at which time we determined weight, body length and lean body mass (measured using Piximus dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, GE Medical Systems).

Genetic interactions.

The following five crosses were made to study the effect of null alleles of Gnaq and Gna11 on the Dsk phenotype: 1, GnaqDsk1/+ × GnaqKO/+; 2, GnaqDsk10/+ × GnaqKO/+; 3, Gna11Dsk7/+ GnaqKO/+ × Gna11KO/+ GnaqKO/+; 4, GnaqDsk1/+ Gna11KO/+ × Gna11KO/+; and 5, Gna11Dsk7/+ × Gna11KO/+. To study signaling pathway interactions, we crossed inbred GnaqDsk1/+ and Gna11Dsk7/+ mice to inbred Kitw–v/+, Pax3Splotch/+ and Ednrbs-l/+ mice, genotyped progeny as described above and counted the number of mice with any white belly hair.

Accession numbers.

GenBank: Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gpa2, J03609; Hydra magnipapillata Gα3, AB006541; Ephydatia fluviatilis sponge Gα3, AB006545; Drosophila melanogaster Gα49B, NM_165920; Xenopus laevis GnaQ and Gna11, L05540 and U10502, respectively; Mus musculus Gna11, BC011169; Homo sapiens GnaQ and Gna11, NM_002072 and NM_002067, respectively. GenBank Protein: Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gpa1, AAB68432; C. elegans Egl-30, AAG32092; Mus musculus GnaQ, P21279.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank T. Wilkie for Gnaq and Gna11 knockout mice, I. Jackson and M. Shin for Dct-lacZ transgenic mice and C. April for RNA samples. This investigation was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. C.V.R was supported by a training grant from the National Cancer Institute and by a Johnson & Johnson Skin Research Grant. G.S.B. is an Associate Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Quevedo WC & Holstein TJ General Biology of Mammalian Pigmentation in The Pigmentary System (eds. Nordlunkd JJ, Boissy RE, Hearing VJ, King RA & Ortonne J-P) 43–58 (Oxford University Press, New York, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nolan PM et al. A systematic, genome-wide, phenotype-driven mutagenesis programme for gene function studies in the mouse. Nat. Genet 25, 440–443 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hrabe de Angelis MH et al. Genome-wide, large-scale production of mutant mice by ENU mutagenesis. Nat. Genet 25, 444–447 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiroishi T A large-scale mouse mutagenesis with a chemical mutagen ENU. Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso 46, 2613–2618(2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitch KR et al. Genetics of dark skin in mice. Genes Dev. 17, 214–228 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hubbard T et al. The Ensembl genome database project. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 38–41 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neves SR, Ram PT & Iyengar R G protein pathways. Science 296, 1636–1639 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilkie TM & Yokoyama S Evolution of the G protein alpha subunit multigene family. Soc. Gen. Physiol. Ser 49, 249–270 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkie TM, Scherle PA, Strathmann MP, Slepak VZ & Simon MI Characterization of G-protein alpha subunits in the Gq class: expression in murine tissues and in stromal and hematopoietic cell lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 10049–10053 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida R, Kusakabe T, Kamatani M, Daitoh M & Tsuda M Central nervous system-specific expression of G protein alpha subunits in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Zoo!og. Sci 19, 1079–1088 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coghill EL et al. A gene-driven approach to the identification of ENU mutants in the mouse. Nat. Genet 30, 255–256 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sunahara RK, Tesmer JJ, Gilman AG & Sprang SR Crystal structure of the adenylyl cyclase activator Gsalpha. Science 278, 1943–1947 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Offermanns S, Toombs CF, Hu YH & Simon MI Defective platelet activation in G alpha(q)-deficient mice. Nature 389, 183–186 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Offermanns S et al. Embryonic cardiomyocyte hypoplasia and craniofacial defects in G alpha q/G alpha 11-mutant mice. EMBO J. 17, 4304–4312 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer TC The migratory pathway of neural crest cells into the skin of mouse embryos. Dev. Biol 34, 39–46 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirobe T Histochemical survey of the distribution of the epidermal melanoblasts and melanocytes in the mouse during fetal and postnatal periods. Anat. Rec 208, 589–594 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkie AL, Jordan SA & Jackson IJ Neural crest progenitors of the melanocyte lineage: coat colour patterns revisited. Development 129, 3349–3357 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan SA & Jackson IJ MGF (KIT ligand) is a chemokinetic factor for melanoblast migration into hair follicles. Dev. Biol 225, 424–436 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne C, Tainsky M & Fuchs E Programming gene expression in developing epidermis. Development 120, 2369–2383 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGowan KM & Coulombe PA Onset of keratin 17 expression coincides with the definition of major epithelial lineages during skin development. J. Cell Biol 143, 469–486 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin MK, Levorse JM, Ingram RS & Tilghman SM The temporal requirement for endothelin receptor-B signalling during neural crest development. Nature 402, 496–501 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geissler EN, Ryan MA & Housman DE The dominant-white spotting (W) locus of the mouse encodes the c-kit proto-oncogene. Cell 55, 185–192 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett DC & Lamoreux ML The color Loci of mice - a genetic century. Pigment Cell Res. 16, 333–344 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackenzie MA, Jordan SA, Budd PS & Jackson IJ Activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase Kit is required for the proliferation of melanoblasts in the mouse embryo. Dev. Biol 192, 99–107 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pavan WJ. & Tilghman SM Piebald lethal (sl) acts early to disrupt the development of neural crest-derived melanocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 7159–7163 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hornyak TJ, Hayes DJ, Chiu LY & Ziff EB Transcription factors in melanocyte development: distinct roles for Pax-3 and Mitf. Mech. Dev 101, 47–59 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiegel AM & Weinstein LS Inherited diseases involving g proteins and g protein-coupled receptors. Annu. Rev. Med 55, 27–39 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong Q et al. Screening of candidate oncogenes in human thyrotroph tumors: absence of activating mutations of the G alpha q, G alpha 11, G alpha s, or thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor genes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 81, 1134–1140 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doi M & Iwasaki K Regulation of retrograde signaling at neuromuscular junctions by the novel C2 domain protein AEX-1. Neuron 33, 249–259 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bastiani CA, Gharib S, Simon MI & Sternberg PW Caenorhabditis elegans Galphaq regulates egg-laying behavior via a PLCbeta-independent and serotonin-dependent signaling pathway and likely functions both in the nervous system and in muscle. Genetics 165, 1805–1822 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee HO, Levorse JM & Shin MK The endothelin receptor-B is required for the migration of neural crest-derived melanocyte and enteric neuron precursors. Dev. Biol 259, 162–175 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Opdecamp K, Kos L, Arnheiter H & Pavan WJ Endothelin signalling in the development of neural crest-derived melanocytes. Biochem. Cell Biol 76, 1093–1099 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hou L, Pavan WJ., Shin MK & Arnheiter H Cell-autonomous and cell non-autonomous signaling through endothelin receptor B during melanocyte development. Development 131, 3239–3247 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollock PM et al. Melanoma mouse model implicates metabotropic glutamate signaling in melanocytic neoplasia. Nat. Genet 34, 108–112 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunisada T et al. Keratinocyte expression of transgenic hepatocyte growth factor affects melanocyte development, leading to dermal melanocytosis. Mech. Dev 94, 67–78 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brundage L et al. Mutations in a C. elegans Gqalpha gene disrupt movement, egg laying, and viability. Neuron 16, 999–1009 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Angelo DD et al. Transgenic Galphaq overexpression induces cardiac contractile failure in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 8121–8126 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida H, Kunisada T, Kusakabe M, Nishikawa S & Nishikawa SI Distinct stages of melanocyte differentiation revealed by anlaysis of nonuniform pigmentation patterns. Development 122, 1207–1214 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hou L, Panthier JJ & Arnheiter H Signaling and transcriptional regulation in the neural crest-derived melanocyte lineage: interactions between KIT and MITF. Development 127, 5379–5389 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Opdecamp K et al. Melanocyte development in vivo and in neural crest cell cultures: crucial dependence on the Mitf basic-helix-loop-helix-zipper transcription factor. Development 124, 2377–2386 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida H et al. Review: melanocyte migration and survival controlled by SCF/c-kit expression. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc 6, 1–5 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ivey K et al. Galphaq and Galpha11 proteins mediate endothelin-1 signaling in neural crest-derived pharyngeal arch mesenchyme. Dev. Biol 255, 230–237 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hosoda K et al. Targeted and natural (piebald-lethal) mutations of endothelin-B receptor gene produce megacolon associated with spotted coat color in mice. Cell 79, 1267–1276 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]