Abstract

Military veterans are a valuable part of the human capital resource pool. Nonetheless, veterans often struggle with their transition into civilian life and workplaces. This problem often limits the extent to which work organizations utilize their talents. Here, we briefly review relevant work from outside the management field and nascent work within the field to build a conceptual model for understanding the integration of veterans into the workplace. We do this by applying diversity and person-environment fit perspectives. A diversity standpoint helps us to understand veterans as a social group and their inclusion in the workplace, while the person-environment fit perspective helps us describe veterans’ compatibility with their work environments in terms of organizational demands and veterans’ needs. We intend for this conceptual model to guide future empirical research on veterans as human capital and their transition into civilian organizations as part of their societal reintegration, career development, and personal well-being.

Keywords: Military veterans, Diversity, Person-environment fit, Career development

Highlights

-

•

Management scholars have neglected the study of military veterans at work.

-

•

Veterans’ workplace experiences are part of their societal reintegration.

-

•

Diversity theory explains veterans’ discrimination, stigma, and identity strain.

-

•

Veterans’ attributes, perspectives, and KSAs fit organizational demands.

-

•

Meaningful work can spillover to fit veterans’ life needs.

1. Introduction

Organizations continuously seek out human talent, and management scholars advise them to tap into a diverse human capital pool to obtain new insights and perspectives. Military veterans are an important and diverse human capital resource for the organizations of the countries they have served. Veterans possess desirable values and valuable knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) (Hiatt, Carlos, & Sine, 2018; Simpson & Sariol, 2018). They are a sizable social group, given that there are 20.4 million veterans in the U.S. (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020a), and more are joining the workforce (Stern, 2017). Yet, many organizations overlook veterans as a human capital resource or fail to fully utilize the KSAs they have developed through their military service.

The reasons for this discrepancy include population differences in age and health, having less civilian work experience, and taking a long time to find a job, particularly after leaving service (Keeling, Kintzle, & Castro, 2018; Loughran, 2014). Also, some organizations are reluctant to hire veterans (Stone & Stone, 2015), and veterans often face bias during job screenings (Stone, Lengnick-Hall, & Muldoon, 2018). Veterans who do gain employment tend to face discrimination, negative stereotypes, stigma, underemployment, identity strain, exclusion, and a lack of adjustment (McAllister, Mackey, Hackney, & Perrewé, 2015; Shepherd, Kay, & Gray, 2019). For these and other reasons, many veterans struggle with integrating into a workplace as part of their transition into civilian life (Black & Papile, 2010; Gati, Ryzhik, & Vertsberger, 2013), which could include failing to find or maintain employment (Ford, 2017). These problems are evidenced in current employment and unemployment rates for veterans and civilians. While the unemployment rate for veterans (3.1%) 1 is favorable when compared to the civilians’ rate (3.7%) (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020a, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020b), the veteran employment2 rate is 46.8%, lower than the 63.2% rate for civilians (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020).

The integration of veterans into civilian life is a vital and important societal issue. As such, many institutional and governmental policy initiatives have been established to support the employment of veterans, including legal affirmative action protections against discrimination and the creation of governmental institutions such as the Department of Veterans Affairs. Further, scholars in sociology, labor economics, psychology, and health have explored the role of military service on economic attainment, employment, and well-being (Bound & Turner, 2002; MacLean & Elder, 2007; McAllister et al., 2015). Much of this research, however, has focused on fixing specific problems such as stress, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) consequences and symptoms (e.g., Gates et al., 2012). Unleashing the potential that veterans have for organizations and society has not received much scholarly attention. The management field is in the best position to fulfill this need, however, there is little research in management that seeks to understand veterans as a human capital pool. This is surprising given that corporate reports and anecdotal evidence suggest that veterans contribute different perspectives, viewpoints, and KSAs such as discipline, teamwork, and leadership (Harrell & Berglass, 2012; Society for Human Resource Management, 2010), and because scholars in management and related fields have used military samples for their studies (e.g., Bass, Avolio, Jung, & Berson, 2003; Dvir, Eden, Avolio, & Shamir, 2002; Eden, 1992).

One reason for this lack of veteran-related research in the management field is the absence of theoretical guidance for scholars (Batka & Hall, 2016). Management scholars have begun to pay attention to veterans (e.g., Shepherd et al., 2019; Simpson & Sariol, 2018; Stone et al., 2018; Stone & Stone, 2015), but studies on the topic are scant, and they have focused only on the selection and hiring of veterans and on their ethics. Currently, the management field has a limited understanding of how firms can best manage veterans, particularly on human resource management after recruitment and selection. A more comprehensive grasp on veterans’ fit in the workplace and their experiences as a social group is needed to understand how organizations can better capitalize on this human capital resource.

Our goal is to propose a conceptual framework for understanding veteran-specific demographics, inclusion, and fit in organizations by applying management theories, particularly the diversity and person-environment (P-E) fit perspectives, which we judge to be the most directly applicable to the challenges that veterans face. We contribute to the management literature by delineating how veterans’ unique personal and social attributes and experiences shape their workplace fit, their levels of inclusion, and the outcomes for both the veterans and their employing organization. We use this framework to inform how organizations employing veterans can best utilize veterans’ unique attributes and KSAs to enhance their compatibility with their civilian work organizations, jobs, and careers, and to be able to foster their inclusion by allowing them access to resources and the ability to fully participate, contribute, and influence decisions in their organizations. We summarize our arguments with testable propositions.

2. Research on veterans’ personal and work lives

A veteran is a person who served in the military and was discharged in other than dishonorable conditions (Cornell University Law School, 2016). This includes those who served in times of peace and war, those deployed to combat or not, and those who served any amount of time and left voluntarily or involuntarily, which could include having a contract end, a medical discharge, or retiring. Most service members experience a transition into the civilian workplace through employment. A small proportion of service members (about 17%) reach full retirement while in the military (Schrager, 2017). Military retirement can come at a relatively early age and some military service members can retire after just 15 years of service under the Temporary Early Retirement Authority (U.S. Department of Defense, 2020). However, even those who retire may seek out employment to better support their lifestyles or may have a desire to continue to have a productive working life.

The transition to civilian life is not easy, which is evidenced by the comparatively low employment rate we noted earlier, by the feelings of identity strain that veterans in the civilian workplace report (McAllister et al., 2015), and by veterans’ high rate of suicide (Steinhauer, 2019). These issues suggest that veterans struggle to successfully navigate their transition into the civilian workplace. Moreover, their ability to integrate successfully into civilian organizations is likely to depend on their distinct experiences in the military, particularly as some experiences (e.g., combat) are associated with adverse work and life outcomes in the future. While the management field has lagged in the study of veterans’ transition into civilian life, this issue has been explored in labor economics, sociology, psychology, and health. Research in these fields has addressed veterans’ societal reintegration, including the (typically adverse) impact of their experiences of trauma, stress, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on unemployment and underemployment. These experiences are of interest to management scholars, along with life-related outcomes such as socioeconomic attainment, health and well-being, family relationships, rates of alcoholism and drug abuse, and incidences of suicidal ideation. Given their relevance and important implications for human resource management, we present a brief review of research on veterans from non-management perspectives.

2.1. Veterans’ civilian societal integration

Sociological research on veterans has centered on the “life course” perspective (See MacLean & Elder Jr, 2007 for a review). This research considers military service as a life-altering experience that influences veterans’ entire lives, including their physical and mental health (Zatzick et al., 1997), educational attainment (Kleykamp, 2013), interactions with civilians (Demers, 2011), homelessness rate (Rosenheck & Koegel, 1993) and family relationships (Ruger, Wilson, & Waddoups, 2002). These studies consistently show there is a multitude of negative effects from military service while veterans reintegrate into civilian society. Research examining military experience, however, shows either negative or no effects from military experience on economic outcomes (Cooney Jr, Segal, Segal, & Falk, 2003; Mehay & Hirsch, 1996), but a lower likelihood of being called back after a job interview (Baert & Balcaen, 2013). Studies comparing “wartime” or service periods (e.g., World War II, Vietnam, post-9/11) depict differences in the amount of civilian support for the wars and the impact of such support on the ability of veterans to reintegrate into society (Beamish, Molotch, & Flacks, 1995). Additionally, differences across gender, race, and ethnicity affect veterans’ levels of employment and wages (Kleykamp, 2013).

Spanning the last several decades, labor economics and sociology perspectives have examined how the military experience affects future civilian work (Bryant, Samaranayake, & Wilhite, 1993; MacLean, 2017) and whether or not having had military service leads to greater levels of productivity, human capital, and higher wages (De Tray, 1982). These perspectives present mixed findings (Little & Fredland, 1979; Teachman, 2004). One important finding, however, is that certain military occupations transfer more easily into civilian jobs (Bryant et al., 1993; Mangum & Ball, 1987). This has led to more recent studies that question whether or not a match between civilian jobs and military training leads to higher rates of employment and socioeconomic attainment. Such “job matching” may mean that veterans who obtain transferable experiences in the military may transition better and have higher employment prospects than veterans in military fields that provide an unclear path to civilian jobs (Routon, 2014). Studies from labor economics have utilized a variety of data sources and methods, including archival panel data and data from various governmental sources (e.g., Angrist & Krueger, 1994; Little & Fredland, 1979), cross-sectional surveys (e.g., Routon, 2014), and experimental designs (e.g., Kleykamp, 2013). Nonetheless, this economic perspective on the transferability of military experience and employment uses a “macro” lens that, while highlighting the importance of job transferability, is unable to answer questions about how organizations can best capitalize on the skills and abilities that people develop in the military.

Sociologists and economists have studied the role of demographics (e.g., race and gender) on wages and employment while providing a diversity perspective on veterans. Findings show that military service improves the employment rate and wages of African American men (Angrist, 1998; Hirsch & Mehay, 2003; Hisnanick, 2003), and as a bridging experience, increases their earnings and college enrollment rates. The military experience also serves as a source of acculturation and improves veterans’ human and social capital, serving as a credential that is “especially advantageous for disadvantaged groups” (Kleykamp, 2013, p. 839). These differences, along with other attributes such as veteran’s education, imply that veterans are as diverse as their experiences and should not be treated as a monolithic group (Kleykamp, 2013).

2.2. Veterans’ health and well-being

Research on veterans’ health and well-being centers on psychological injuries and disorders such as PTSD, stress, anxiety, depression, and substance abuse, some of which have comorbidity. Despite centering on adverse outcomes, health studies also have shown that the military equips people with the ability to work under pressure (e.g., Tomar & Stoffel, 2014).

According to the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), the guide used by psychologists and other mental health professionals to diagnose mental disorders, PTSD is a psychiatric disorder that occurs in people who have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event, such as war. PTSD is associated with the intense reliving of traumatic or life-threatening events through disruptive memories, ruminating on past events, having nightmares, avoiding scenarios that serve as reminders of the previous event, and being hypervigilant (Hayes, VanElzakker, & Shin, 2012). Research on veterans’ PTSD is extensive, perhaps due to its relevance to medical and psychological care, but PTSD is only one of various mental disorders that can result from the experience of war. Despite being associated with veterans, PTSD is more common among civilians since a variety of traumatic events such as natural disasters, violent personal assaults, accidents, as well as war, can lead to the disorder. Further, the psychological impact of war is stronger for civilians than for veterans, even if this impact is overlooked by the media (De Rond & Lok, 2016).

The actual PTSD rate for veterans is unclear and subject to debate. A reanalysis of Vietnam veterans’ data suggests a lifetime prevalence of 18.7%, and 9.1% at 10 to 12 years after the war (Dohrenwend et al., 2006). Government estimates suggest that 20% to 30% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans show PTSD symptoms (U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, 2015). Meta-analytic data for Iraq veterans show that PTSD estimates range widely from 1.4% to 60%, with an average prevalence estimated at 23% (Fulton et al., 2015; Sundin, Fear, Iversen, Rona, & Wessely, 2010). Nonetheless, veterans who have been diagnosed with PTSD or show symptoms of the disorder face poorer levels of health, a lower quality of life, higher incidences of self-medicating, higher rates of substance abuse, and a high suicide rate, along with work-related outcomes such as unemployment, poor workplace functioning, and absenteeism (Greden et al., 2010; Hoge, Terhakopian, Castro, Messer, & Engel, 2007; Zatzick et al., 1997).

Research in health and well-being shows that having had combat experience presents veterans with physical and mental health problems throughout their lives, including during retirement (Hoge et al., 2004; Levy & Sidel, 2009; MacLean & Edwards, 2010; Walker, 2010). The unique, traumatic experience of combat can lead to a great amount of distress during and after service. Such experiences may be associated with depression, anxiety, anger problems, and functional impairment (Pflanz & Sonnek, 2002; Wright, Cabrera, Eckford, Adler, & Bliese, 2012). Combat veterans are also more likely to divorce (Ruger et al., 2002) and to experience PTSD than other veterans (MacLean & Edwards, 2010; McAllister et al., 2015). Combat experience is not common to all veterans, although approximately 58% of post-9/11 service members have been deployed at least once to a combat zone (Parker, Igielnik, & Arditi, 2019), and more than 2.7 million service members were deployed to combat zones between 2001 and 2015, accounting for more than five million combat deployments (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018). Further, the indirect exposure to combat experienced in many military jobs, such as damage control surgery medics in war zones (De Rond & Lok, 2016), can also lead to trauma and psychological injury. In sum, actual combat and indirect exposure to combat are important to consider because they can adversely impact the personal and work lives of veterans.

2.3. Psychology

Different psychological fields such as military, counseling, and occupational health psychology have rich traditions in the study of military settings as well as veterans’ issues. Research in these fields has centered on stress, PTSD, and the provision of counseling (Laurence, & Matthews, M. D. (Eds.)., 2012). Some of these studies, however, have addressed veterans’ organizational behaviors and work outcomes in ways that have important managerial implications. For instance, Currie, Day, and Kelloway’s (2011) occupational health psychology study explored how veterans’ work experience influences their life outcomes. They found that affective commitment reduces veterans’ PTSD symptoms and their intentions to quit, as well as that veterans struggle when their military, civilian, and organizational selves collide.

In contrast to the negative picture described by many studies, some research has underscored the positive aspects to be derived from military experience. Aside from psychological injury, traumatic experiences can also lead to post-traumatic growth (PTG), which refers to the positive personal changes that result from the struggle to deal with trauma (Solomon & Dekel, 2007; Tedeschi & McNally, 2011). While many of these studies employ cross-sectional designs, their findings are consistent with the major findings on trauma and PTG in the field of psychology (Jayawickreme & Blackie, 2014; Santiago et al., 2013).

In all, the findings from these fields provide important implications for the management of veterans’ human capital, which if understood and applied, should improve organizational performance and veterans’ integration into civilian organizations. A few management scholars and industrial/organizational psychologists have begun to examine veterans in the workplace. For example, Mackey, Perrewé, and McAllister (2016) found that, among veterans, various stressors were associated with job strain and lower job satisfaction and work intensity. Nonetheless, a synthesis of these research areas shows there are gaps in our knowledge about the experience of veterans in work organizations and about how civilian organizations can best capitalize on veterans’ experiences and KSAs, as well as meet individual needs beyond providing them with employment and income. These research questions may be best addressed from industrial/organizational psychology and management perspectives.

2.4. The management perspective

Recent research in organizational behavior and human resource management, as well as industrial/organizational psychology, has examined perceptions of veterans from colleagues and managers in recruitment and selection. Applying Stone and Colella’s (1996) perspective on hiring workers with disabilities, Stone and Stone (2015) reviewed the organizational factors that affect human resource decisions related to hiring veterans, including stigma, veteran attributes, fit, and the perceived level of their skill transferability. In their study of stereotypes of veterans and their chances for employment, Stone et al. (2018) found that people examining resumes of veterans believed that, relative to civilians, veterans had a stronger perceived job fit, better leadership skills, better teamwork skills, and greater emotional stability, but that they had fewer social skills. Similarly, Shepherd et al. (2019) discovered that laypeople, managers, and employees perceive veteran workers to be planners but to lack the ability to feel emotions and sensations. Further, a study by McAllister et al. (2015), which was published in a military psychology journal, showed that the lack of congruence between a veteran’s military and civilian workplace identity was related to higher job stress and identity strain, as well as lower vigor and work intensity. These perceptions drive beliefs that veterans are incompatible in jobs or careers that require emotional intelligence and so-called “soft” or “people” skills.

At the strategic level, recent research has examined veterans’ ethical behavior as executives and leaders in firms. Given their strategic approach, most of these studies used archival data sources and panel data analysis. Simpson and Sariol (2018) found that veterans are more likely to be hired as members of boards of directors after securities class action lawsuits, suggesting that veterans are valued because of their ethical integrity. Koch-Bayram and Wernicke (2018) found that CEOs with military experience, relative to civilian CEOs, were less likely to be involved in financial misconduct due to being more obedient and more likely to follow rules and regulations. Finally, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018 found that having organizational ties to the military was associated with a higher level of venture survival in countries with armed conflict. While the focus of this research was on ethical behavior, its results show that the behavior of veterans in executive roles has important organizational implications.

These recent efforts show that the study of veterans from a management perspective holds promise. Research in organizational behavior and human resource management has made the initial step by examining perceptions and stereotypes in the hiring of veterans (Shepherd et al., 2019; Stone & Stone, 2015). Yet, we still need a conceptual framework describing factors related to veterans’ success and organizational utilization after hiring decisions have been made, including their retention, motivation, and engagement.

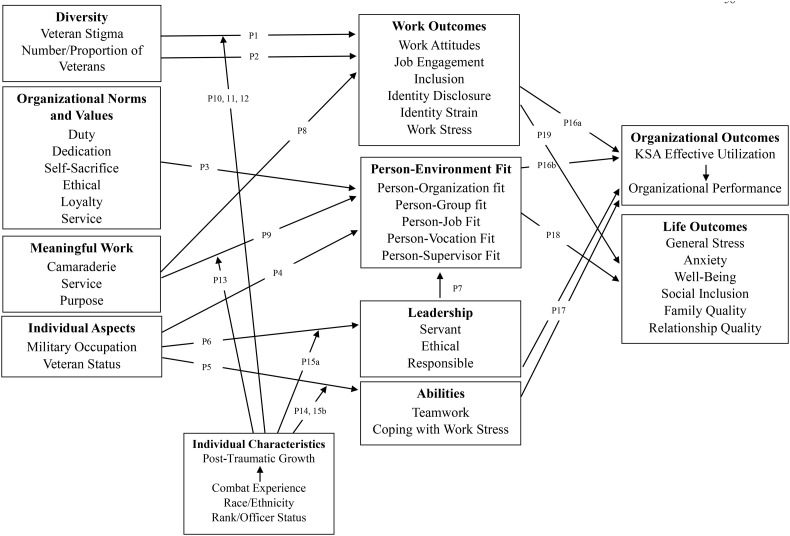

To this end, we delineate a conceptual framework intended to explain how organizations can promote the effective utilization of veterans’ talents while also having a positive impact on veterans’ lives through work. We posit that diversity and P-E fit perspectives are pertinent to understand the experience of veterans in civilian work organizations. First, by adopting a diversity standpoint (Shore et al., 2011; van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007), we describe veterans as a source of workplace diversity and a demographic group in need of greater inclusion. We explain key workplace experiences, attitudes, and behaviors of veterans in light of their being a minority social group, including discrimination against them, stereotyping, stigma, and identity strain. Second, we adopt a P-E fit perspective (Edwards, 2008; Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, 2005) to describe the compatibility between veterans’ military experiences, values, beliefs, norms, and KSAs and their civilian organizations. We address organizations’ utilization of veteran employees from a demands-abilities perspective, which refers to the extent to which employees’ abilities meet organizational demands, and their compatibility from a needs-supplies perspective, which refers to the extent to which an organization’s environment satisfies employee needs (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). Finally, we use a societal reintegration lens and reconsider veterans’ well-being to address how positive work experiences spill over into the non-work lives of veterans. We advance several propositions and describe our conceptual framework intended to outline the future research agenda on veterans in the workforce. We depict this conceptual framework as a research model in figure Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of veteran fit, diversity and inclusion in civilian organizations

3. Applying the diversity perspective

Workplace diversity consists of individual differences in work entities such as groups and organizations. These differences encompass a broad range of demographic attributes (e.g., gender, age, race, and ethnicity) by which people define themselves and others. Traditionally, these demographic attributes have been associated with access to status, power, and resources in work organizations (van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007). Although veteran status has been overlooked in diversity research within the management field, it is nevertheless a social category by which people define themselves and others. Veteran status shares many aspects with other social identities, including being unchangeable, which is similar to biological sex and race, and being relatively invisible, which is the case with sexual orientation. Moreover, veteran status is task-related since it is associated with specific KSAs. It is also associated with specific deep-level values, beliefs, and personality traits that comprise cognitive diversity. Similar to certain other demographic attributes, affirmative action legislation, including the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act (USERRA), exists to protect veterans from employment discrimination in the U.S. Further, disabled veterans are protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Workplace diversity research and management-led diversity programs seek to increase the presence and inclusion of traditionally underrepresented and disenfranchised social groups. Moreover, there is a “business case” for diversity that focuses on increasing firm performance through diversity (van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007). Diversity principles related to social group fairness in hiring, pay, and other workplace procedures apply to veterans (Angrist, 1998; MacLean, 2017). Like other demographic minorities, many veterans have experienced workplace discrimination, exclusion, and a lack of organizational support that, along with the perceptions that they have a poor level of compatibility, are reasons for a high amount of work stress and tension (Wenger, 2014). For these reasons, the social justice rationale behind the organizational inclusion of demographic minorities is applicable to military veterans as a social group. This application would have the goals for organizations to provide veterans with equal access to resources and information as other social groups and to treat them as insiders who fully participate, contribute, and influence decisions in the organization (Roberson, 2006; Shore et al., 2011). Assessing experiences that are unique or more common among veterans, such as the stigma of trauma, can help us to apply a diversity perspective to veterans and help us to understand how organizations can increase the numerical representation of veterans and foster their inclusion in organizations.

3.1. Veteran identity

A person’s identity is his or her concept of self. Identities differentiate a person from others but also form a basis for belongingness with others with whom they share such characteristics (Shore et al., 2011). This constitutes personal identity—our unique sense of self, and social identity—which is the part of the self-concept that stems from belonging to social groups (Tajfel & Turner, 1985). Diversity research that concerns social identities and relies on social identity theory (Hogg & Terry, 2000) holds that people belong to a multitude of social groups and possess multiple identities that are negotiated over time and space. Some identities may be more central to one’s self-concept or be more salient in a particular situation (Tajfel & Turner, 1985). Military experience is one of many social group identities that may be salient to veterans, along with social identities associated with the demographics typically examined in diversity research. Being a military veteran can be a central component of veterans’ identity or can become salient in a work environment if it provides them with a sense of distinctiveness from other people. This identity also shapes how coworkers see and treat them.

Personal and social identities are also tied to people’s career and vocational choices. Military service shapes the identities of service members, beginning with their self-selection into the military. This identity is strengthened in basic training or “boot camp,” which breaks down and strips recruits of their civilian identities and replaces those identities with a military one that is further developed over their time in the military. This acculturation and socialization process emphasizes strong kinship bonds, camaraderie, and unit norms, and to even consider equipment as a symbolic part of themselves (Godfrey, 2016; Woodward & Jenkings, 2011), causing military service to become a core component of their self (Daley, 2013). This socialization process is a complex and life-changing experience that carries over into veterans’ post-military-service lives (Arkin & Dobrofsky, 1978). As veterans leave the military, they often struggle to adapt to a civilian world and lifestyle and to find work in an environment with which their sense of self clashes (Black & Papile, 2010), which places a strain on their self-identity. Many veterans attempt to maintain their self-identity but express a sense of loss upon returning to civilian life (Brunger, Serrato, & Ogden, 2013). A poor transition into the workplace may translate into a loss of community, financial security, and a sense that one’s life is purposeful (Brunger et al., 2013). This loss can be exacerbated by a forced discharge from the military due to health issues or combat trauma. For example, infantrymen who are required to be physically fit may see their sense of self-worth decrease (Haynie & Shepherd, 2011) and experience identity strain if they become injured and unable to fulfill their military duties.

3.2. Stigmatization and veteran identity strain

The struggle by veterans to maintain their self-identity after military life is exacerbated by a stigma attached to their veteran status. While many veterans are proud of their military experience and identify highly with other veterans, being a veteran has a stigma—a perceived personal flaw within a social context (Goffman, 1963; Ragins, 2008). A common stigma is that veterans are “crazy” and “ticking time bombs,” views often perpetuated by media portrayals of veterans as traumatized or “damaged” (Kleykamp & Hipes, 2015). The stigma is stronger for veterans who engaged in combat or show signs of PTSD (Hipes, Lucas, & Kleykamp, 2014). Paradoxically, civilians have reported they assume combat veterans have behavioral problems, but also report being more socially closer to and more supportive of combat veterans than of non-combat veterans (MacLean & Kleykamp, 2014). Unfortunately, people who belong to stigmatized groups face stereotyping, harassment, prejudice, and discrimination in society and at work (Crocker & Major, 1989; Ragins, 2008).

Stigma consciousness, that is, being aware and sensitive to having a stereotyped status, can exacerbate the consequences of being stereotyped (Pinel & Paulin, 2005). Veterans who are sensitive to the stigmas associated with veterans may be less likely to identify with their veteran self-identity. The paradoxical situation of being proud of an identity that is stigmatized by out-group members leads to greater levels of discomfort and increases tensions related to identity strain. In turn, this can manifest in adverse individual outcomes such as poor work attitudes and reduced engagement in one’s job.

Veteran status is a concealable stigmatized identity that carries social devaluation and can be hidden from others (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009). Most veterans disclose their military identity to prospective employers during the job application process, but many conceal their identity to colleagues or supervisors to avoid being ostracized, criticized, or harassed. The reasons cited by veterans who do so include avoiding false assumptions made by coworkers about their mental health and political ideology. By one estimate, up to 40% of veterans hide their military background from their colleagues (McGregor, 2015), a proportion higher than the rate of non-disclosure of sexual orientation by LGBT community members (Croteau, 1996). An unintended adverse consequence of the non-disclosure of one’s veteran identity is failing to receive needed mental health care to avoid the shame associated with seeking such care (Ouimette et al., 2011; Vogt, 2011). Even though stigma is associated with adverse consequences, concealing a stigmatized identity that is valued and central to one’s self-concept also leads to psychological distress (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009).

Employees who belong to groups with concealable stigmas (e.g., veterans, LGBT community members, and people with mental and other invisible disabilities) face the decision to disclose their status to coworkers. Veterans often have good reasons for their apprehension in disclosing their veteran status. For instance, people with mental health disorders are less likely than their peers without such disorders to be rated as suitable for employment (Hazer and Bedell, 2000a, Hazer and Bedell, 2000b) and to be hired for jobs (Brohan et al., 2012). As a result, many are concerned with how disclosing their mental health issues would affect their employment, colleagues’ feelings about them, and how it might lead to potential rejection (Brohan et al., 2012). Veterans face similar barriers and struggles in the workforce, and theory on employees with disabilities has informed how we think about veterans’ experiences at work (Stone & Stone, 2015). There are, however, differences between these groups. For instance, employees may be likely to perceive a veteran with PTSD symptoms as a greater threat to others than a civilian coworker who has a similar mental health condition (e.g., a mood disorder).

Even if veteran employees choose to avoid disclosing their veteran identity to coworkers, some may give away clues through their mannerisms (e.g., using military 24-hour time), physical appearance (e.g., short haircuts), and the use of military jargon. Some have identifiers that make it impossible to conceal their identity, such as tattoos identifying their military units or physical signs of combat injury (e.g., scars or prosthetic limbs). Those who cannot conceal their identity may instead seek ways to embrace the stigma and enhance their self-esteem (Crocker & Major, 1989; Goffman, 1963), such as relying on social validation from similar others (Kreiner, Ashforth, & Sluss, 2006) to avoid identity strain and maintain solidarity with other veterans.

The experience and awareness of one’s stigmatization as a veteran may lead to adverse work attitudes and behavior and lower organizational inclusion. We focus on the individual perceptions of stigmatization since work outcomes are tied to the employee’s perception. But these perceptions often stem from actual stigmatization actions such as bias, prejudice, and a lack of intergroup contact and knowledge. We posit that stigma consciousness will be associated with veteran employees choosing to hide their veteran status from their coworkers. Stigmatization will be a negative experience regardless of whether or not a veteran employee discloses their veteran status to their coworkers because not disclosing a core part of their identity is also related to higher identity strain.

Proposition 1

Veterans’ perceived stigmatization will be negatively related to their (a) work attitudes, (b) job engagement, (c) inclusion, and (d) disclosure of their veteran status in the workplace, as well as positively related to their (e) identity strain and (f) work stress.

3.3. Veteran diversity and workplace outcomes

The social categorization and information/decision-making perspectives (van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007) can be applied to diversity involving veterans. Because of social identity and categorization processes (Tajfel & Turner, 1985), veterans and civilian co-workers may see each other as distinct social groups, which can result in bias, prejudice, lower interpersonal trust, a lower amount of communication, and less cooperation among them. By applying research on tokenism and relational demography (Kanter, 1977; Riordan, 2000), we predict that a lack of numerical representation of veterans in the workplace would result in greater work stress and turnover. On the other hand, the presence of other employees and managers in the organization who have military experience should signal to veterans that they are welcomed in the organization (Shore et al., 2011). A high proportion of veterans in the workplace can also stimulate a sense of belongingness to the workgroup and organization and lead to greater workgroup cohesion, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and work engagement. This numerical or proportional presence of veterans in the organization could also drive intergroup contact, which builds knowledge about one another through increased communication and reduce bias, prejudice (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006), and stigma. The information and decision-making perspective (van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007) would emphasize that veterans provide divergent viewpoints and a broader cognitive range of KSAs, expertise, and perspectives that drive elaboration processes and better decision-making.

Proposition 2

The number and proportion of veterans in the workplace and its managerial ranks will be positively related to their (a) work attitudes, (b) job engagement, and (c) inclusion, as well as negatively related to their (d) work stress.

The presence of hospitable climates for diversity and inclusion are catalysts that improve the positive effects of diversity on individual and organizational outcomes (Dwertmann, Nishii, & van Knippenberg, 2016). This implies that positive organizational outcomes are derived not only from employment practices that are fair and equitable for all social groups, but also from enabling social integration so that members of diverse social groups are treated as esteemed insiders and where their voice and insights shape decision-making (Shore et al., 2011). Recent research suggests that organizations should implement diversity management practices to build a climate for inclusion that focuses on the experiences of unique social groups (Dwertmann et al., 2016), such as LGBT employees, religious minorities, and military veterans. Aside from building a general climate for inclusion that is hospitable to all, organizations can also implement focused efforts in diversity management. A hospitable climate for veteran inclusion would imply integrating them socially; valuing their values, norms, and beliefs; and recognizing their KSAs.

4. Applying the P-E fit perspective

Through their military experience, service members develop values, norms, personal attributes, and KSAs that are valuable for non-military careers and occupations. One reason that organizations often fail to capitalize on these attributes of veterans may be that managers are not aware of or fully understand how to effectively utilize their veteran employees’ talents in a corporate or civilian work environment. Moreover, many veterans feel that they are incompatible with civilian corporate cultures (McAllister et al., 2015). For instance, some veterans perceive that civilian workplaces emphasize personal effort over group cohesion (McAllister et al., 2015; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018), which is a common military value. These circumstances may lead managers and organizational members to believe veterans are incompatible with their corporate environments, and this can potentially cause veterans to feel alienated, underutilized, and uninspired in their organizations (McGregor, 2015). These perceptions may be understood through person-environment (P-E) fit theory, which can be applied to study how to foster veterans’ compatibility with their new organizations and vocations, and how to help organizations meet veterans’ needs.

P-E fit refers to the compatibility employees experience in their work environment, including their fit with the organization, job, work group, supervisor, organization, and vocation (Edwards, 2008; Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). Person-organization (P-O) fit, the most studied form of fit, refers to worker’s compatibility with colleagues in the organization, while person-job fit refers to the extent that a person and a job match each other’s needs and demands. Scholars also distinguish supplementary fit, which is the similarity between individual and environmental or organizational attributes such as values and norms, from complementary fit, which is how a person and the environment/organization offset each other’s needs and demands (Muchinsky & Monahan, 1987). In turn, complementary fit involves either a person’s ability to meet demands or the extent to which an environmental aspect (e.g., the job) provides for an employee’s extrinsic and intrinsic needs.

This distinction between complementary and supplementary fit in the workplace can clarify some misunderstandings. For example, distinct norms, values, and personalities can harm group dynamics or veteran employees’ job attitudes, stress, and engagement, but their abilities may fill a gap in a job or organization’s demands. Veterans who are perceived to be (supplementary) misfits may provide the KSAs that meet the demands of their new environment (complementary fit). Applying P-E fit can reveal how adequate management can bring to light relevant individual attributes, experiences, and abilities. We need to understand how the distinct attributes and KSAs that people develop in their military service apply to the different types of fit (e.g., supplementary versus complementary) in the workplace. Here, we assess common attributes that are developed through military service, including values, norms, beliefs, and abilities such as leadership, teamwork, and coping with stress. Heeding Kleykamp’s (2013) suggestion not to treat veterans as a monolithic group, we address several unique individual factors and experiences relevant to our model, namely military occupation, rank, exposure to combat, and experiences of PTG.

4.1. Values, norms, and beliefs

Military service develops core values and norms, including a sense of duty (Coll, Weiss, & Yarvis, 2011), dedication, self-sacrifice, honor, loyalty, and service, as well as beliefs about the importance of teamwork, persistence, honesty, and bravery (Matthews, Eid, Kelly, Bailey, & Peterson, 2006). Veterans develop these values, norms, and beliefs as young military members through deep immersion in a military culture that emphasizes a strong combat identity as a masculine warrior (Dunivin, 1994), discipline, professional ethos, ceremony, and etiquette (Murray, 1999). This experience shapes veterans’ personalities and employment choices later in life (Jackson, Thoemmes, Jonkmann, Lüdtke, & Trautwein, 2012; MacLean & Elder Jr, 2007).

As stated earlier, management scholars have found that veteran executives demonstrate ethical values in their present careers (Koch-Bayram & Wernicke, 2018; Simpson & Sariol, 2018). These results echo the empirical findings from other fields such as criminology, accounting, and finance, which suggest that veterans demonstrate ethical norms, values, and behavior. These studies also have found that veterans exhibit less criminal behavior (Bouffard, 2003), have a lesser likelihood as managers to engage in tax avoidance (Law & Mills, 2017), and have a lesser likelihood as CEOs to be involved in corporate fraud and stock option backdating (Benmelech & Frydman, 2015). Integrating these research findings indicates veterans tend to “do the right thing” when faced with the prospect of profit that requires questionable behavior.

Other military values, norms, and beliefs have the potential to benefit workplaces, but also to hamper the compatibility veterans’ experience in their new organizations, particularly during their onboarding or socialization period after their transition into civilian life. Veterans who join work groups and organizations that clash with military values and ethics may not fit in (McAllister et al., 2015). For this reason, anecdotal stories of veteran misfit can likely be attributed to differences in traditional military and corporate cultures (Dunivin, 1994; Murray, 1999). In contrast, veterans in work groups and organizations with cultures and climates that incorporate values, norms, and beliefs familiar to them would support supplementary fit. In sum, veterans in corporate and organizational environments that uphold the values, norms, and beliefs mentioned above are likely to experience higher person-organization and person-group fit, relative to civilians and veterans in other environments.

Proposition 3

Veteran employees in work groups and organizations with strong values, norms, and beliefs related to (a) duty, (b) dedication, (c) self-sacrifice, (d) loyalty, (e) ethics, and (d) service will experience greater person-group and person-organization fit relative to their civilian counterparts.

4.2. Knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs)

Despite the dearth of academic research on the KSAs applicable to work organizations that service members develop in the military, corporate reports and surveys suggest that veterans bring with them a great number of benefits to organizations in terms of the personal qualities and KSAs they possess (e.g., Groysberg, Hill, & Johnson, 2010; Harrell & Berglass, 2012).

The compatibility between the military and civilian jobs that an employee performs is the most direct example of supplementary, demands-abilities person-job fit. Research has shown that veterans who have civilian jobs that match their prior military occupations are more likely to see economic gains (Goldberg & Warner, 1987). One important reason for this finding is that they are able to transfer the KSAs developed during their service to a civilian job.

The military job service members perform is known as the military occupational specialty code (MOS) for the U.S. Army and Marines, the Air Force specialty codes (AFSC) for the U.S. Air Force, and the Navy enlisted classification system for the U.S. Navy,3 each of which depicts the duties that the service member performs in the military. These MOS categories are perhaps the most observable way of viewing KSAs veterans attain during their service. Some MOS categories have clearly defined civilian counterparts and have a greater degree of skill transferability than other MOSs (Mangum & Ball, 1987), and there are websites with “translators” that show the civilian equivalents for various military occupations based on their similarities (e.g., military.com; onetonline.org). For example, the Army MOS1 of military police aligns with civilian police officer, and the MOS of medic is somewhat transferable to health care occupations such as emergency medical technician. By contrast, an MOS that is highly specialized in combat or military operations (e.g., Field Artillery Automated Tactical Data System Specialist) may not be easily transferable to a civilian role or workplace. The presence of occupational similarity does not mean that a transition will be direct, given that veterans may face barriers such as needing licenses and additional certification programs (Keita, Diaz, Miller, Olenick, & Simon, 2015; Voelpel, Escallier, Fullerton, & Rodriguez, 2018). Overall, however, civilian employment in a field related to their former military jobs is likely to foster greater vocation, career, and person-job fit.

Proposition 4

The similarity between veteran employees’ military occupations and their current jobs will be positively related to their person-job fit.

Assessing military occupation transferability provides a needed step in the assessment of the vocational prospects for veterans. However, only 20% of veterans’ civilian positions resemble their military occupations (Westat, 2010). Research on this topic has not addressed whether such differences are due to the absence of comparable jobs or because veterans elect to pursue new vocational directions. Nonetheless, this rate of vocational change suggests that focusing on military occupations, while useful, is not enough. Another possibility would be to assess the actual KSAs that veterans develop in all areas of their service.

Aside from the specific KSAs that are associated with a military occupation and that are transferable to specific civilian occupations, veterans develop general KSAs that are more widely applicable. These qualities include teamwork, discipline, leadership, and the ability to cope with stress. For example, surveys of veterans show they perceive that their service has enhanced their work ethic, discipline, teamwork, leadership, mental toughness, and ability to adapt (Zoli, Maury, & Fay, 2015). One study shows that hiring personnel, managers, and future colleagues perceive that veterans possess a greater amount of leadership skills than their civilian counterparts (Stone et al., 2018). However, the development of these KSAs is likely to differ based on service members’ experiences and military occupations (e.g., being in the infantry vs. being a medic). These KSAs are more difficult to objectively assess than military occupations, and the rhetoric surrounding these KSAs is inconsistent and anecdotal.

Some individual traits and abilities stem from a person’s self-selection into the military, but some are developed and refined during service. For example, veterans typically score high on cooperation, self-discipline, independence, and the ability to cope with adversity in their military service (Aldwin, Levenson, & Spiro, 1994). Therefore, military service may be an effective screen for employee selection if scholars and managers understand how such traits and abilities can be applied to specific work cultures and environments.

4.2.1. Teamwork

One of the central elements of military service is teamwork (Matthews et al., 2006; Zoli et al., 2015). The military develops a sense of camaraderie uncommon in the civilian workplace. Most veterans develop strong social bonds toward one another as a part of their identity (Woodward & Jenkings, 2011), an experience that translates into the expectation of experiencing the same levels of camaraderie and team spirit in their work organizations. For this reason, veterans tend to feel more comfortable in workplace environments where teamwork and camaraderie are valued, and they report feeling frustrated or confused by their absence in civilian organizations (Brunger et al., 2013), which can lead to job dissatisfaction (Koenig, Maguen, Monroy, Mayott, & Seal, 2014). Organizations can use this preference and capacity for teamwork to implement team dynamics that better integrate veterans into the workplace.

4.2.2. Coping with work stress

Military service members are trained to handle complex operational environments associated with stress and anxiety. They learn to cope with and operate in situations where they have no control over their daily schedule, they deal with harsh treatment from drill sergeants, adapt to rigorous standards, and have specialized training in such tasks as the use of firearms, among others. In doing so, they learn to persevere in the face of adversity and stress, which improves their coping skills (Aldwin et al., 1994).

The culture of discipline that veterans learn in the military is linked to their perseverance, which also has been conceptualized as grit, hardiness, resilience, toughness, and determination, all of which are important abilities for coping with stress at work. For instance, “grit” has been used to represent a passion for attaining long-term goals despite the challenges one may face (Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews, & Kelly, 2007). Grit is related to goal achievement, the completion of initial training in the military, and retention, as well as to be common in higher degrees among West Point cadets when compared to civilians (Kelly, Matthews, & Bartone, 2014; Matthews et al., 2006).

Military experience also builds hardiness, which is key to coping with stressful situations (Maddi, 2007). Hardiness has been described as a “psychological style” or personal trait that is associated with commitment at work and in life, active engagement and control over one’s circumstances, as well as taking on challenges (Bartone, Roland, Picano, & Williams, 2008). Hardiness has been studied in military environments, and research has found it is related to better health, being able to cope with stress (Bartone, 1999), and being able to complete special forces training (Bartone, Johnsen, Eid, Brun, & Laberg, 2002). Both military and combat experience build resilience, which is the ability to recover quickly from adversity (Aldwin et al., 1994; Maclean & Elder, 2007), and a sign of emotional maturity (Spiro III et al., 2015). These abilities to stick to a goal, to consider obstacles as a challenge to be overcome instead of a hindrance, to be resilient, and to be mature help with workplace demands. Finally, military experience is a signal to employers of perseverance and dependability (Mangum & Ball, 1987).

Military experience leads to abilities related to coping and being hardy such as discipline, perseverance, grit, toughness, and determination. Perseverance and the ability to cope are transferable to a variety of civilian workplace settings, and they provide veterans with a personal advantage when dealing with stressful situations. For example, having military experience has been found to give police officers an edge in handling stress and dealing with burnout (Ivie & Garland, 2011). As such, employees who are veterans are likely to display high demands-abilities, person-job, and person-vocation fit in civilian careers characterized by crises, risk, and turbulent environments.

In sum, under P-E fit theory, the KSAs developed through military training and experience should lead veteran employees to experience fit in environmental situations that require teamwork and coping with stressful demands.

Proposition 5

Relative to their civilian counterparts, veteran employees will have a greater ability to (a) work in teams and (b) cope with work stress.

4.2.3. Leadership

According to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM, 2010) and many corporate recruitment programs that target veterans (Groysberg et al, 2010), veterans bring valuable leadership skills to firms. The military and leadership have been described as “practically inseparable” by management scholars (Wong, Bliese, & McGurk, 2003), military training has been shown to develop leadership skills (Harms, Spain, & Hannah, 2011), and veterans have been described as possessing valuable leadership and managerial skills (Dexter, 2016). For this reason, many studies on leadership in management and related fields have utilized military samples (e.g., Bass et al., 2003). However, the literature has not delved into the specific leadership skills and styles that are learned in the military, the mechanisms involved in their development, or how these leadership styles are applicable in civilian organizations.

The military emphasizes leadership as the alignment of people toward a common goal that can be measured in terms of the number of lives lost or saved. Military members from both enlisted and officer ranks who have leadership positions receive leadership training. Even lower-level enlisted personnel are often expected to take on leadership roles. For example, Marines who have as little as two years of experience or less are often expected to lead teams in complex operational environments where decisions need to be made rapidly and without consulting more senior officers. This approach to decentralized combat operations that empowers lower-level enlisted personnel in combat has given birth to the idea of “strategic corporals” in the U.S. Marine Corps (Barcott, 2010). Military officer training has been shown to improve leadership abilities and to increase the likelihood of becoming a manager in the future (Grönqvist & Lindqvist, 2016). Some military leadership abilities, attributes, and styles are equivalent to the corporate leadership styles studied in management.

Research on ethical behavior from the criminology and business fields that we reviewed earlier provides a strong case for the expectation that leaders and managers who are veterans should display styles and behaviors associated with ethical leadership. Moreover, the military’s value of self-sacrifice is analogous to servant leadership’s focus on serving others before oneself. Servant leadership attributes such as stewardship, trustworthiness, community building, and a need to serve (Van Dierendonck, 2011) are consistent with military values. Military leaders are responsible for tending to all needs of the men and women under their command (Wong et al., 2003). Such leaders must take responsibility for orders across ranks and must attend to all needs of the soldiers who are deployed under their command, including their financial and family issues. The notion that military leaders would not “send someone where he or she would not go himself or herself” aligns with responsible leadership. This notion or style of leadership centers on building trustful relationships among stakeholders based on an inner obligation to do the right thing unto others (Maak & Pless, 2006).

Differences in leadership between military and civilian organizations do exist. For example, a meta-analysis shows that transformational leadership had a greater impact on perceptions of effectiveness in military than in non-military groups (Gaspar, 1992). Assuming that veteran employees pursuing leadership roles are able, with help from their organizations, to translate their leadership abilities to a civilian environment, veteran status will be associated with the attributes and styles characteristic of servant, ethical, and responsible leadership.

Proposition 6

Relative to their civilian counterparts, veteran employees in leadership roles will display a style more characteristic of servant, ethical, and responsible leaders.

Similarly, veteran employees are likely to fit in environments where leadership styles are compatible with their experience and expectations they developed in the military, including what the leadership style of their supervisor should be. The military culture’s emphasis on leadership, chain of command, and respect for authority is likely to shape veteran employees’ respect for and reliance on their managers and leaders. Research shows that the support veterans receive from their leaders and supervisors is important in reducing their stress (Hammer, Brady, & Perry, 2019), which demonstrates the importance of the behavior of veterans’ managers and leaders. As stated earlier, the numerical representation of veterans in managerial roles should have a positive effect on their work outcomes. Such an effect is likely to occur not only due to relational demography effects, but also because veteran managers and leaders are likely to understand and exhibit leadership styles and behaviors consistent with the military values, norms, and beliefs veteran employees in followership roles likely uphold. Regardless of their managerial or leadership experiences in the military, we suggest that veteran employees in followership roles are more likely to fit in organizations whose leaders and managers exhibit leadership styles and behaviors consistent with servant, ethical, and responsible leadership.

Proposition 7

Veteran employees will have stronger person-supervisor fit with supervisors and managers who have servant, ethical, and responsible leadership styles.

4.3. The role of meaningful work

Meaningful work and positive work experiences are important to everyone (Rosso, Dekas, & Wrzesniewski, 2010), but are particularly important to veterans. Most people derive self-esteem and meaning through their work, but having meaningful work is likely more important among those who have followed a calling to serve the greater good (Rosso et al., 2010), such as enlisting in military service. Similarly, meaningful work is likely more important for people who have been socialized into a culture that values duty, service, and self-sacrifice. One study of male veterans found that having meaningful work is associated with an increase in self-esteem (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018). Doenges (2011) found that student veterans who found meaningful work in their self-defined calling reported an increase in their meaning in life, positive affect, and positive relationships. Further, finding meaningful work has been ranked by veterans as extremely important, ranking it above finding competitive employment (Schutt et al., 2003).

We infer that, for veterans, finding work in organizations, jobs, careers, and vocations where they feel they have a purpose and make a difference would enhance their sense of self-worth and the meaningfulness they attach to their lives. We suggest that, relative to civilians, veterans are more likely to value, pursue, and select jobs that provide them with the opportunity for self-expression through meaningful work. We also suggest that veterans are relatively more likely to pursue, value, and select jobs and careers where they can find camaraderie, a sense of purpose, and the opportunity to serve others. A job and career with these characteristics would enhance veteran employees’ complementary, needs-supplies, person-job and person-vocation fit. Consistent with the P-E perspective, veteran employees who find these characteristics in their jobs and careers are likely to display beneficial work attitudes and behavior.

Proposition 8

Camaraderie, service, and purpose in a job and career will be positively related to a) work attitudes, (b) job engagement, and (c) perceived inclusion, as well as (d) negatively related to work stress in a greater manner for veteran employees than for their civilian counterparts.

Proposition 9

Camaraderie, service, and purpose in a job and career will be positively related to person-job and person-vocation fit in a greater manner for veteran employees than for their civilian counterparts.

5. Individual characteristics as moderators

Scholars argue that we should explore individual aspects and differences that shape veterans’ experiences (Kleykamp, 2013). Aside from the role of military occupation, other individual aspects of a job and an organization can influence veterans’ fit and inclusion in an organization as well as their ability to put their KSAs into practice. These may include their branch membership, tenure in the military, amount of civilian work experience, wartime or service period, demographics, military rank, breadth of their exposure to combat, and experiences of PTG, among others. We center on five individual aspects that are directly related to fit and inclusion: combat experience, PTG, rank, tenure, and race/ethnicity.

5.1. Combat

As reviewed earlier, the experience of combat can lead to mental problems and disorders. Direct and indirect combat experience can also enhance the centrality of a veteran’s military identity in their self-concept and increase the likelihood of this identity becoming salient in organizational circumstances. As a central identity, this experience is likely to enhance the veteran employees’ sense of personal distinctiveness from others in the workplace and enhance their awareness of bearing a stigma related to such experience. In effect, combat veterans are more likely to avoid disclosing their veteran status to others in the workplace and to experience the identity strain associated with this avoidance.

Proposition 10

For veteran employees, military combat experience will (a) enhance the negative relationship of veteran stigmatization with the disclosure of veteran status in the workplace, and (b) enhance the positive relationship of veteran stigmatization with identity strain.

5.2. Race/ethnicity

Research from the social sciences shows that African American veterans have work-related advantages over veterans from other racial groups (D'Anton, 1983; Kleykamp, 2013). However, related research also shows that African American combat veterans have significantly fewer callbacks for their job applications when compared to other groups Kleykamp, 2009, Kleykamp, 2010). Stigma may also influence veterans once they have joined an organization. Edwards (2016) argues that the effects of institutional racism and related work outcomes are magnified for African American military veterans. Considering the intersectionality of veteran status, race, and combat experience for stigmatization suggests that stigma consciousness and related outcomes, including identity strain and work stress, are higher for African American combat veterans than for their white counterparts. Although these studies concern the experiences of African Americans, their arguments, which are based on institutional racism and having lower access to power and resources in society, suggest that increases in strain and stress also apply to other race/ethnic demographic minority groups. We propose the following for the intersection of race/ethnicity and combat experience:

Proposition 11

The role of perceived stigmatization on veterans’ work attitudes, job engagement, inclusion, veteran status disclosure, identity strain, and work stress will be greater among combat veterans who are race/ethnic minorities.

5.3. Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG)

As reviewed earlier, psychologists have suggested that positive personal changes after overcoming adversity can lead to personal growth. This adversity can include the direct and indirect experiences of combat for veterans, including the roles of psychological trauma and mental disorders such as PTSD (Solomon & Dekel, 2007; Tedeschi & McNally, 2011). The experience of war and combat can be deeply disturbing, but this experience and its aftermath are complex and can also have positive outcomes. The cultural, professional, and organizational context through which service members filter, frame, and cope with their war experiences can shape psychological injuries, making war experiences traumatic for some but not for all (de Rond & Lok, 2016). Moreover, the grit, hardiness, and ability to work under pressure developed through combat challenges can be a catalyst that teaches veteran employees to overcome obstacles in their lives and careers. Research shows that veterans who engaged in combat are more likely to develop coping skills, value human life, and have a clearer sense of direction in their lives. They are also more assertive, self-disciplined, goal-oriented, resilient, and entrepreneurial relative to other veterans (Avrahami & Lerner, 2003; Elder Jr & Clipp, 1989).

PTG is an important reason why the direct and indirect experiences of war and combat can lead to positive effects. PTG does not negate the adverse experience of psychological trauma or disorder but is related to them. Almost everyone who experiences PTG also acknowledges experiencing distress. PTG does not mean returning to a starting point, as this would imply that the trauma did not occur, but rather means showing improvement and going beyond an ability to resist or avoid being damaged by a distressing event (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Conversely, studies show that up to 72% of veterans with PTSD symptoms also display PTG, with social support, coping skills, and personality traits such as extroversion and openness to experience helping to shape who shows PTG (Tsai, El-Gabalawy, Sledge, Southwick, & Pietrzak, 2015).

The experience of growth can strengthen people’s identification with a social group even when they are conscious of the stigma attached to being a member of it. This type of growth can become a social learning experience similar to the normalization of the stigma for veterans who have PTSD, depression, suicidal ideation, or other mental disorders but tend to underutilize mental health services (Michalopoulou, Welsh, Perkins, & Ormsby, 2017). When someone realizes he or she is not the only one who needs help, he or she can find culturally accepted ways to embrace and overcome the stigma and maintain a high level of self-esteem (Bryan & Morrow, 2011). Similarly, in organizational settings, veterans who have experienced and overcome combat trauma through PTG are more likely to embrace their veteran identity and avoid identity strain thanks to the fortitude, perseverance, bravery, and personal strength associated with this personal growth (Peterson, Park, Pole, D'Andrea, & Seligman, 2008). This implies that PTG is a mediating mechanism through which combat experience shapes the relationship between veteran employees’ perceived stigmatization from the disclosure of their veteran status to others at work and their experience of identity strain. Since not all combat veterans experience trauma, this would constitute a partial mediation of a moderating relationship. For instance, for veterans who have experienced combat trauma, PTG would weaken the relationship between their perceived stigmatization from their veteran status disclosure to others at work and identity strain. Thus:

Proposition 12

PTG will partially mediate the moderation combat experience has on the relationship of veteran employees’ perceived stigmatization with their (a) disclosure of their veteran status in the workplace and their (b) identity strain. The role of perceived veteran stigmatization on (lower) identity disclosure and (greater) identity strain will be strongest for combat veterans who have not experienced PTG, moderate for veterans who did not experience combat, and weakest for combat veterans who experience PTG.

Despite the adverse effects of any trauma, which cannot be overlooked, the resilience exhibited through fortitude, perseverance, and bravery, as well as the personal growth and development of character strengthened by overcoming adversity, have positive effects on people’s abilities, lives, and sense of well-being (Peterson et al., 2008). As described earlier, veterans develop an ability to cope with work stress through their military training and experience, and this ability to cope can be heightened by facing the challenges of war and combat. The experience of PTG is a reason direct and indirect involvement in war and combat helps veterans see their personal and work lives in a better light. PTG is associated with an increase in one’s appreciation of life in general, the development of closer and more intimate relationships, and an increase in one’s sense of personal strength (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). PTG also improves people’s appreciation for their work lives, an important aspect of a sense of well-being. Therefore, through PTG, the experience of combat can also inspire veteran employees to focus on what matters most to them, which likely includes the camaraderie and social relationships that can be found in work organizations, and to focus on their purpose in life and the opportunities for service that meaningful work provides.

Proposition 13

For veteran employees, military combat experience will enhance the positive relationship of meaningful work with (a) person-job and (b) person-vocation fit. PTG will mediate this moderation.

Proposition 14

For veteran employees, military combat experience will enhance the positive relationship of veteran status with their ability to cope with work stress. PTG will mediate this moderation.

5.4. Rank and officer experience

Research on military leadership or that has used military leaders as its sample points to the importance of experience in leadership effectiveness, aside from other aspects such as personality and external circumstances (Wong et al., 2003; Yammarino & Bass, 1990). Based on this, we offer team leader or officer experience during military service as a moderator.

Differences in rank (e.g., being a private or a sergeant) and officer status (e.g., being a colonel) may have differential effects on the relationships previously proposed for various reasons. Officers tend to receive more leadership training due to their positions. In the army, for example, new non-commissioned officers (e.g., sergeant or E-5) are required to complete the Basic Leader Course, while more senior enlisted non-commissioned officers (e.g., command sergeant majors, or E-9) must complete other required leadership courses to achieve that rank. Thus, given the amount of leadership training that higher-ranked military personnel receive and the greater amount of opportunities they have had to put them into practice, veterans who achieved a higher rank during their service are likely to possess a greater amount of applicable leadership skills and abilities.

Rank has also been linked to different veteran outcomes, including identity strain (McAllister et al., 2015) and health (MacLean & Edwards, 2010). Literature from policing shows that higher-ranked female police officers are better able to deal with harassment and a lack of inclusion thanks to having better coping strategies and the power that comes with rank (Haarr & Morash, 2013). Borrowing from this literature, a similar rationale can be applied to veterans and their experiences with harassment, a lack of inclusion, and similar issues in the civilian workplace, particularly those that can affect work stress.

Proposition 15

For veteran employees, rank and officer experience will enhance the positive relationship of veteran status with their (a) leadership abilities and their (b) ability to cope with work stress.

6. Diversity and fit: organizational and life outcomes

Our review and conceptualization of the diversity and P-E fit perspectives for veteran employees lead us to the idea that experiencing compatibility and inclusion will have positive consequences for the organization and these employees. Our review explains how veterans learn to value teamwork, camaraderie, and other social aspects of being members of an organization that is larger than themselves through their deep immersion in military culture. The prevalence of these values implies that veterans’ compatibility and their experience of inclusion in an organization is particularly important to them. Paradoxically, veteran employees are likely to experience a lack of inclusion and poor supplementary fit in their work organization due to common prejudice and actual or perceived cultural clashes due to differences in values. Nonetheless, the arguments we presented imply that those who are included and fit in their work organizations are likely to exhibit positive work attitudes and behaviors, such as organizational commitment and job engagement, which in effect can serve to ameliorate adverse stigmas and improve their social integration, which can allow veterans and civilians to communicate and learn more from one another.

These beneficial attitudes and behaviors are associated with an organizational climate for veteran inclusion and better workplace functioning and performance. In particular, veteran employees who experience inclusion and fit will allow organizations to effectively utilize the KSAs that veterans possess, including those that drove their self-selection into the military and also that the ones they developed during their service. This will better enable veterans to have a successful transition into the civilian workplace and to experience growth, including PTG. Further, organizations in industries and environments characterized by the demand for leadership, teamwork, and abilities to cope with work stress are likely to utilize and profit from these and other KSAs the most.

Proposition 16

Veteran (a) inclusion and (b) person-environment fit will be positively related to the effective utilization of veteran employees’ KSAs in the workplace.

Proposition 17

The effective organizational utilization of veteran employees’ KSAs will mediate a positive relationship between veteran employees’ KSAs (such as leadership, working in teams, and coping with work stress) and organizational performance.

6.1. Positive life spillovers

Assessing how an organizational environment supplies workers’ needs (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005) addresses a needs-supplies perspective on P-E fit and the work-life interface to consider how employees’ work lives positively influence their personal lives. Uncovering positive work-to-life spillovers would also tie management scholarship with research fields that address veterans’ health and well-being. Workers experience positive job attitudes when their jobs and work environment supply the attributes that fulfill their needs (Van Vianen, 2000). The values and other personal attributes veterans have developed through their military service are likely to drive their preferences, needs, and desires in their future vocations. If these are met, the experience of need fulfillment and compatibility with a work environment should be related to positive work attitudes and behaviors (Mackey et al., 2016; McAllister et al., 2015).

Research on veterans shows that having a purpose in life is associated with healthier behaviors, better mood, and physical ability (Mota et al., 2016). Finding satisfying work is the most important factor contributing to a successful transition from military service (Black & Papile, 2010). Similarly, a study on combat veterans shows that, aside from non-work factors, affective commitment to an employing organization was negatively related to PTSD symptoms (Currie et al., 2011). This implies that positive organizational experiences can spill over to the life domain and lead to positive effects, such as mitigating service-related trauma and associated stress and anxiety. For veteran employees, an engaging job that is satisfying to and inclusive of them can incite commitment to that job. In turn, this commitment can affect their personal lives, enhance their societal integration, and enrich their family and social relationships.