Abstract

Background

Many states have pharmacist contraceptive prescribing laws with several others in the process of enacting similar legislation. Little continuity or standardization exists across these programs, including development of counseling materials. Although the risk of unplanned pregnancy is greatest among adolescents and young adults, developed materials are not always sensitive to youth.

Objective

Use a modified Delphi Method to develop standardized youth-friendly counseling tools that are sensitive to pharmacy workflow during pharmacist contraceptive prescribing.

Methods

A multidisciplinary expert panel of women’s health pharmacists, community pharmacists, adolescent medicine pediatricians, obstetrician-gynecologists, and public health advocates was assembled and reviewed materials over three iterations. Comments were anonymized, summarized, and addressed with each iteration. A graphic designer assisted with visual representation of panel suggestions. Reviewer feedback was qualitatively analyzed for emergent themes.

Results

The Delphi Method produced five main themes of feedback integrated into the final materials including: attention to work flow, visual appeal, digestible medical information, universal use of materials, and incorporating new evidence-based best practices. Final materials were scored at a Flesch-Kincaid Grade of 5.1 for readability.

Conclusions

Use of the Delphi Method allowed for the efficient production of materials that are medically accurate, patient-centered, and reflect multiple disciplinary perspectives. Final materials were more robust and sensitive to the unique needs of youth.

Keywords: Qualitative research, contraception, pharmacists, counseling

Introduction

Unintended pregnancy is a serious health concern for women in the United States with 45% of pregnancies identified as unintended for women of all ages. Adolescents and young adults bear the brunt of the burden, with 91% of pregnancies described as unintended by adolescents and 59% for young adults.1 Because youth are disproportionately affected, approaches to decreasing unintended pregnancy needs to actively engage the youth population younger than 24 years old. Studies of unintended pregnancy among young people frequently cite access to contraception as a barrier, with interventions that reduce this barrier showing significant decreases in unplanned pregnancy rates among adolescents and young adults by 20–40%.2–8

To increase access to contraception, several states have passed legislation allowing pharmacists to prescribe hormonal contraceptives via statewide protocols.9–13 The basic process for obtaining contraception via this mechanism is:

A patient presents to the community pharmacy and completes a self-administered questionnaire to screen for medical contraindications.

The pharmacist recommends appropriate contraceptive(s) based on patient preferences, their responses to the medical questionnaire, and local statutes.

Once a method has been selected, the pharmacist prescribes the product and provides method specific counseling that includes instructions for starting the contraceptive, management of side effects, adherence, and expectations for follow-up visits.

While many states have pharmacy contraceptive prescribing laws in place and several others are in the process of enacting similar legislation, there is little continuity or standardization in the implementation and delivery of these programs. Some states allow pharmacists to prescribe for patients younger than 18 years old, while others do not.9–13 Materials that are recommended to be used during the pharmacist contraceptive prescribing process lack youth friendly content and may not be sensitive to pharmacy workflow. Without implementation guidelines and tools for pharmacist prescribing, there has been low utilization of services to date despite the high need for expanded access, particularly among young people that find pharmacy provision of sexual and reproductive health services appealing.14,15

The Delphi Method is an open-access, expert panel iterative review process that can be used in healthcare counseling tool development. The process is unique due to the controlled interaction between respondents of the Delphi Method, which avoids direct confrontation that otherwise may introduce bias or alter feedback.16 Additionally, the anonymity of the feedback provides an alternative to direct debate in which individual participants may dominate the conversation or yield to professional hierarchy.17 The goal for using the Delphi Method in any setting is to determine consensus opinion on a specific issue from “real-world” experts through an iterative process.

Since its inception, the Delphi Method has been modified for use in a broad spectrum of applications including business and technology forecasting, public policy creation, and as a consensus-building tool for healthcare research, clinical guidelines, and education, including pharmacy research.17–21 These studies suggest that the Delphi Method is particularly useful in the development of patient education materials as it allows for expert consensus in both content and patient readability.

The objective of this study was to use a modified Delphi Method to develop standardized youth-friendly counseling tools that are sensitive to pharmacy workflow during pharmacist contraceptive prescribing. “Youth-friendly” was defined by researchers as using common, non-medical language, and having a Flesch-Kincaid 6th grade, or lower, readability level.22,23 This research has been approved by the institutional review board at Indiana University.

Methods

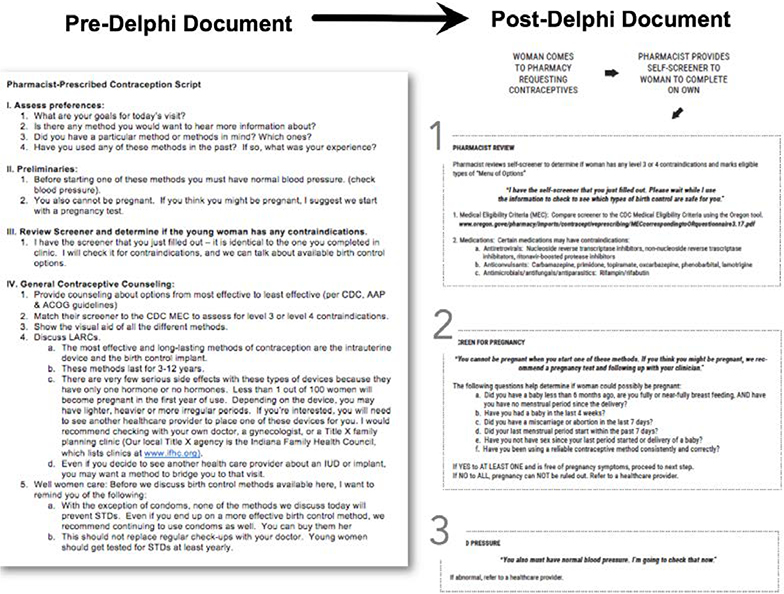

For creation of pharmacist contraceptive counseling materials, researchers created a draft toolkit of materials based on published protocols from states with implemented programs. Created materials included a pharmacist protocol, a “menu” of contraceptive options to highlight available methods in the pharmacy and other settings, and a self-screening questionnaire with items linked to corresponding items from the Centers for Disease Control’s United States Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (USMEC) that may be potential contraindications for hormonal contraceptive use.24 Additionally, fact sheets were developed to facilitate method specific counseling to review mechanism of action, starting the contraceptive, common side effects, any potential benefits or concerns, as well as managing common mistakes encountered using each method. Figure 1 includes a sample of initial materials sent to reviewers. Final versions of all materials within the pharmacist contraceptive prescribing toolkit can be found in Appendices A-C and at www.pharmacyaccessforms.org.

Figure 1:

Example of Initial and Revised Document

Once the draft materials were created, a panel of nine experts across seven disciplines was assembled, which included pediatric and adolescent gynecologists, adolescent medicine physicians, community and women’s health pharmacists, and public health professionals. These experts were identified for participation via professional networks, individual conversation with an investigator, and peer recommendation to assure geographic, training, and skill set diversity. Recruitment of the expert panel occurred via personal communication by one or more of the researchers. The expert panel reviewed the draft materials and provided anonymous feedback electronically via the Qualtrics® platform. Experts were asked to reflect and comment on the overall toolkit and on each subsection of the materials. This enabled them to focus on language, flow, and accuracy of each portion.

All feedback was summarized, anonymized and discussed by researchers. Discussion focused on generalizability, commonly accepted clinical practice, and readability. Following this discussion and after reaching researcher consensus, changes were incorporated into the pharmacist toolkit. Researchers were blinded to what feedback came from which reviewer. Materials were updated and redistributed to the expert panel with a summary of changes accepted and explanation for feedback that was not incorporated. This process was repeated for three cycles until expert panel consensus was reached regarding content and layout of materials. The Flesch-Kincaid readability level of the final materials was analyzed through word processing software (Microsoft® Word for Mac, Version 15.17, 2015).

Reviewer feedback was qualitatively analyzed to identify themes in participant responses. Two investigators independently coded all feedback via word processing software. Each response was discussed until consensus was achieved. A codebook of inductive themes and corresponding definitions was created throughout analysis for consistency between researchers. Additional researchers were available to settle any discrepancies.

Results

Reviewer feedback focused on four main themes: attention to work flow, visual appeal, digestible medically accurate information, and universal use of materials. Researchers identified a fifth theme that emerged due in nature to the breadth of disciplines included in the expert panel: incorporating new evidence-based practices.

Attention to Work Flow

The first theme focused on organizing the pharmacist protocol into a visual algorithm with attention to flow. Reviewers’ feedback lead to the creation of a flowchart to consider for implementation within current pharmacy workflow. On the initial draft, it was noted that the flow was not clear from step to step.

“Maybe include a picture representation for the screener of contraceptive methods. They can cross out any methods that are not appropriate. This would be easy for adolescents to understand.”

“It’s unclear how easy it will be to compare the screener to the MEC tool. But perhaps that’s something pharmacists are used to doing and it will be an easy task for them?”

Additional materials were added to the toolkit that provided a direct linkage between the self-screening questionnaire and the USMEC to eliminate an additional step for the pharmacist. The final version of the workflow process was simplified with just two options—one for women with estrogen contraindications and one for women without estrogen contraindications. Boxes were placed around each step of the process and arrows added to show the flow between steps.

“I think the flowchart is very helpful. Will make the process much faster for staff (especially in women without any medical problems).”

Visual Appeal

The second theme was assuring visual appeal of materials. This feedback was vital for allowing the final version of materials to minimize confusion to pharmacy staff. One reviewer initially stated:

“I found the extensive use of bold, italics and underline made this document extremely difficult to read. I would suggest removing a lot of this formatting, particularly the italics.”

“For this entire pharmacy guide, I would recommend not centering the script copy. That’s harder to read than paragraphs that are left aligned.”

Given the importance of visual appeal to assure these materials are user friendly, a graphic designer was consulted after the first iteration to provide expertise on conveying the information in a design-centered approach. By the end, reviewers’ comments were overwhelmingly positive and perhaps best summed up by a simple quote:

“I really like the layout of these.”

Digestible Medically-Accurate Information

The third identified theme was providing concise, consistent, medically accurate, and understandable language that was sensitive to young people. The way questions and statements were phrased was closely reviewed at every step. For example, one reviewer noted how the word “bleeding” could be interpreted differently:

“I worry a little about adolescent’s’ interpretation of some of these…they may interpret any bleeding as a period, regardless of timing or normalcy.”

Clarifying language was added to the materials based on reviewer feedback, as deemed appropriate following researcher discussion. For this specific recommendation, language was changed from simply stating “spotting” in the initial version to “bleeding between periods” in the most current version.

Consistency of the language used was also important, as was noted in a reviewer comment:

“Would recommend being consistent about using ‘birth control’ versus ‘contraceptives.’”

“Be consistent throughout survey (e.g., sometimes you say ‘injection’ and sometimes you say ‘shot/injection’. I prefer the latter.”

In the above examples, and others highlighted by reviewers, researchers revised the materials to consistently use easier to understand language (i.e.; birth control). By doing so, a lower level of health literacy is required to understand the materials, while also addressing aspects of the fourth identified theme (universal use) to ensure materials were appropriate for women of all ages.

In addition to using consistent language, reviewers identified the need to present the same information in a similar layout across all materials.

“This is the first time you mention spermicide. Do you want to mention on other info sheets, for consistency?”

“I would make sure the risks sections are similar for progestin only methods (same for estrogen containing). This listing has no risks but having Depo have two risks does not make sense to me.”

Assuring the consistency of language and information throughout the documents was a continuous process as edits were made in every step of the Delphi process and have continued afterwards as final versions were read from start-to-finish, end-to-start, side-by-side, and compared to other published literature. During the final revisions, one reviewer commented:

“I appreciate that they are all concise, provide a picture and have the information in a similar format.”

Following all revisions, the created counseling documents were scored at a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 5.1 for readability.

Universal Use

The fourth main theme that emerged from reviewers’ comments was creating a single set of materials to be used for all patients that is sensitive to the unique needs of youth. Multiple comments were noted that spoke to the need to phrase and present information in a way that all women could interpret and understand.

“‘Bad reaction’ may need additional definition (e.g., side effect). I would NOT remove ‘bad reaction’. That’s great lay-mans language.”

“‘Have you abstained from sexual…’ may be too high literacy. Ask, ‘Have you had sex since your last period started?’”

With each round of reviews, researchers continued to focus on incorporating language and information in a way that would be inclusive for all women by selecting simpler terms and a streamlined format for displaying similar types of information.

The multiple iterations of review allowed for an evolution of feedback received and materials created. Initial comments focused on the flow and overall organization, while subsequent reviews lead to comments more focused on clinical content and specific details. For example, reviewers provided comments from the first review such as:

“Didn’t the pharmacist already discuss methods in the prior section?”

“If the patient doesn’t state an immediate preference at this point, is this a time where the pharmacist might go back to the preferences the patient stated and make a suggestion?”

“Is there a reason hormonal IUD and contraceptive implants are not included?”

In the final iteration, reviewers focused more on factually correct details such as:

“Please update the list of LNG EC [levonorgestrel emergency contraception] options – those listed are no longer sold.”

“Progestin-only (correct) versus progesterone-only mini pill (incorrect).”

Additional examples highlighting each of these themes can be found in Table 1.

Table 1:

Specific Examples of Feedback by Theme

| Theme | Examples of Feedback Received |

|---|---|

| Organization | “I appreciate that they are all concise, provide a picture and have the information in a similar format.” “I think the flow chart is very helpful. Will make the process much faster for staff.” |

| Visual Appeal | “I know we aren’t supposed to focus on design, but will still like to put in a vote for changing the questions from title case to sentence case for readability.” “…Not sure if this is the final design for this document, but the font choice is a bit hard to read when there is a lot of copy… Choosing a thinner font and increasing the space between the subpoints might make that a little easier to read.” |

| Language | “I would make sure the risks sections are similar for progestin only methods… This listing no risks but having depo have two risks does not make sense to me.” “I do not like the wording around bones. It has been shown to make bones weaker…” |

| Single Set of Materials | “… include a picture representation… of the contraceptive methods. They [pharmacists] can cross out any methods that are not appropriate. This would be easy for adolescents to understand” “I think you may need to use a different way to indicate effectiveness. Most people probably don’t know how to interpret the numbers. It would be better to add a description indicating (for example) 9 out of 100 women may get pregnant in a year when using this method.” |

Incorporating New Evidence-Based Best Practices

The final theme identified during data analysis was that of incorporating new evidence-based practices, and the differing approach to incorporating new evidence based on the type of healthcare professional. Multiple reviewers made comments such as:

“Re[garding] ECP [emergency contraceptive pill] would emphasize it can be used for up to FIVE days after unprotected sexual intercourse.”

“Late Depo shots – more common guidance has been concern if more than 2 weeks late (14–15 weeks) – are there good data that you don’t need EC [emergency contraception] unless at 16 weeks – that seems long.”

Researchers addressed these concerns through a thorough review of updated resources to verify and resolve conflicting information, discussion of the reach and influence of the recommending body, and considering how the majority of practicing community pharmacists would handle a discrepancy in new evidence and product labeling. Pharmacists may feel limited to providing information that is included within product labeling, and may not feel comfortable relying on updated best practice recommendations that have not yet made it to the product labeling, such as an acceptable duration of 15 weeks between DepoProvera injections, an extended intrauterine device (IUD) duration of use that spans 7 – 12 years based on the individual product, efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception for up to 5 days following unprotected sexual intercourse, and the ability to leave the levonorgestrel implant in place for up to 5 years.

Discussion

Use of the Delphi process allowed researchers to efficiently collect and incorporate input from experts across the country. By capturing feedback from a wide range of disciplines, materials were created that incorporate “best practices” and perspectives from multiple healthcare fields and allowed researchers to make relevant changes. It has been estimated that it takes approximately 22 hours to develop one-hour of simple learning content, with an increasing amount of time for more extensive support materials. The three rounds of the Delphi process were completed over approximately 6 months and utilized less than an estimated 5 hours of an individual expert’s time, which lead to rapid improvements and revisions to the pharmacist contraceptive prescribing toolkit materials that would not have been possible using a less structured approach.

The multiple reviews inherent to the Delphi Method allowed reviewers the opportunity to critique overarching issues in the materials such as organization and flow, as well as to improve specific language and content. When determining the content to include, researchers considered many factors such as the strength of the evidence, the recommending body (e.g.; CDC and WHO given more weight), and whether the pharmacist was counseling and referring (e.g.; implant, IUD) or prescribing the product. For example, specific feedback was suggested to update the length of time a copper IUD is able to be left in place (e.g.; > 10 years) as may be seen clinically. Product labeling still states the copper IUD may be left in place for “up to 10 years”, therefore researchers opted to leave the wording as was previously written. These discussions to determine the specific content to include with the materials reflect the issues that exist in practice today. When new evidence emerges that may change practice, some healthcare professionals are quick to adapt their practice while other professionals are slower to embrace updated recommendations. New evidence that has not been incorporated into product labeling may pose a unique challenge for pharmacists involved in a prescribing role. As has been previously identified, pharmacists need to be aware of updated recommendations to provide the most accurate information to patients and must find a way to stay updated to incorporate new evidence and practice into their prescribing and counseling.

The use of the Delphi Method is not without limitations. There is the potential for bias in the selection of reviewers and a limited time for experts to participate in multiple reviews. For the development of pharmacist materials described here, researchers strategically sought reviewers from different disciplines and institutions, with a request to extend invitations to additional experts based on participant recommendation. To respect the reviewers’ time, researchers were direct and succinct in specific feedback requested, as well as provided set deadlines for receipt of feedback. Additionally, researchers recognized the need to acknowledge all reviewers’ contributions through the incorporation of ideas and explanation when particular ideas were not utilized.

Implications

As modes of healthcare delivery expand beyond traditional settings and include practitioners with more diverse levels of training, the importance of standardized materials that have been reviewed by clinical experts is vital to assure dissemination of accurate information. The Delphi Method is a feasible and efficient approach to gathering the input from multiple disciplines in the creation of accurate and standardized materials. The materials created through this effort may allow for more appropriate pharmacist-patient interactions, resulting in an improved quality of contraceptive care for young people.

Conclusions

Pharmacist contraceptive prescribing materials were significantly revised and more robust following completion of the Delphi Method. Use of the Delphi Method allowed for the efficient production of materials that are medically accurate, patient-centered, and reflect multiple disciplinary perspectives. The materials created for this pharmacist contraceptive prescribing toolkit are available for public use (www.pharmacyaccessforms.org).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008 – 2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:843–852. 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cahill N, Sonneveldt E, Stover J, Weinberger M, Williamson J, Wei C, Brown W, Alkema L. Modern contraceptive use, unmet need, and demand satisfied among women of reproductive age who are married or in a union in the focus countries of the Family Planning 2020 initiative: a systematic analysis using the Family Planning Estimation Tool. Lancet. 2018;391:870–882. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33104-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Population Reference Bureau. Youth Contraceptive Use: Effective Interventions, a Reference Guide. February 2017.Available at: https://assets.prb.org/pdf17/PRB%20Youth%20Policies%20Reference%20Guide.pdf.Accessed30 July 2019.

- 4.Gottschalk LB, Ortayli N. Interventions to improve adolescents’ contraceptive behaviors in low- and middle-income countries: a review of the evidence base. Contraception. 2014;90:211–225. 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Secura GM, Madden T, McNicholas C, Mullersman J, Buckel CM, Zhao Q, Peipert JF. Provision of no-cost, long-acting contraception and teenage pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1316–1323. 10.1056/NEJMoa1400506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Taking the unintended out of pregnancy: Colorado’s success with long-acting reversible contraception, January 2017.Available at: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/PSD_TitleX3_CFPI-Report.pdf.Accessed30 July 2019.

- 7.Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Madden T, Peipert JF. Preventing unintended pregnancy: the contraceptive CHOICE project in review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:349–353. 10.1089/jwh.2015.5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricketts S, Klingler G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline in births among young, low-income women. Persp Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46:125–132. 10.1363/46e1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Protocol for Pharmacists to Furnish Self-Administered Hormonal Contraception [California]. Title 16, California Code of Regulations section 1746.1. Available at: http://www.pharmacy.ca.gov/licensees/hormonal_contraception.shtml.Accessed30 July 2019.

- 10.Statewide Protocols [Colorado]. Hormonal Contraception Available at: https://www.copharm.org/statewide-protocols.Accessed30 July 2019.

- 11.Board of Pharmacy. Oregon Pharmacists Prescribing of Contraceptive Therapy. Available at: http://www.oregon.gov/pharmacy/Pages/ContraceptivePrescribing.aspx.Accessed30 July 2019.

- 12.Protocol for Pharmacist Prescription of Hormonal Contraception [New Mexico]. June 2016.Available at: http://www.rld.state.nm.us/uploads/files/OCConfirmedFinalJune2016.pdf.Accessed30 July 2019.

- 13.Hawaii Senate Bill 513 [SB 513]. July 2017.Available at: http://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/session2017/bills/SB513_.PDF.Accessed30 July 2019.

- 14.Gomez AM. Availability of Pharmacist-Prescribed Contraception in California, 2017. JAMA. 2017;318:2253–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonsalves L, Hindin MJ. Pharmacy Provision of Sexual and Reproductive Health Commodities to Young People: A Systematic Literature Review and Synthesis of the Evidence. Contraception. 2017;95:339–363. 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalkey N, Helmer OF. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manage Sci. 1963;9:458–467. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker AM, Selfe J. The Delphi method: a useful tool for the allied health researcher. British Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 1996;3:677–681. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm-Net. 2016;38:655–662. 10.1007/s11096-016-0257-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cantrill JA, Sibbald B, Buetow S. Indicators of the appropriateness of long term prescribing in general practice in the United Kingdom: consensus development, face and content validity, feasibility, and reliability. Qual Health Care. 1998;7:130–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott AR, Sanderson CJ, Rush AJ 3rd, Alore EA, Naik AD, Berger DH, Suliburk JW. Constructing post-surgical discharge instructions through a Delphi consensus methodology. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:917–925. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forbes R, Mandrusiak A, Smith M, Russell T. Identification of competencies for patient education in physiotherapy using a Delphi approach. Physiotherapy. 2018;104:232–238. 10.1016/j.physio.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flesch R A new readability yardstick. J Apply Psychol. 1948;32(3):221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Derivation of new readability formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count, and Flesch Reading Ease Formular) for Navy enlisted personnel. Research Branch Report 8–75. 1975; Millington, TN: Naval Air Station Memphis. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, Berry-Bibee E, Horton LG, Zapata LB, Simmons KB, Pagano HP, Jamieson DJ, Whiteman MK. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–104. 10.15585/mmwr.rr6503a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.