Abstract

Objectives:

The health system of Kerala, India has won many accolades in having health indicators comparable to developed countries. But oral health has not received its due importance at the policy level. With the burden of oral diseases on the rise in the state, a critical introspection of the existing system is warranted. The objective of this review was to assess the oral health care system in Kerala to provide policy solutions.

Methods:

This study adopted a mixed methodological approach that gathered information from the primary and secondary sources, which included health facility surveys, key informant interviews, review of published literature, and websites of governmental and non-governmental bodies. The WHO framework of health system building blocks was adapted for the assessment.

Results:

A review of epidemiological studies conducted in Kerala suggests that the prevalence of oral diseases is high with the prevalence of dental caries at the age of 12 years ranging from 37-69%. The state has a dentist population ratio of 1:2200 which is well within the prescribed ratio by WHO (1:7500). Only 2% of dentists in Kerala work with government sector catering to 0.6 million of the approximately 33.4 million population. This point to the absence of oral care in first contact levels like primary health centers. Service delivery is chiefly through the private sector and payment for dental care is predominantly through out-of-pocket expenditure.

Conclusion:

Despite having the best health indicators, the oral health system of Kerala is deficient in many aspects. Reorientation of oral health services is required to combat the burden of diseases.

Keywords: Equity, health systems, oral health

Introduction

Common oral diseases like dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral cancer satisfy the criteria for being considered as a public health problem.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7] Evidence suggests that oral diseases share common risk factors with many other chronic diseases/conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity, transient ischemic attacks, etc.[8,9,10] The burden of oral diseases is high in both developed and developing nations.[11] There has been a steady increase in the burden of oral diseases in India since the last two decades[12] despite the country producing the highest number of dental graduates per annum. This contrasting observations point a need to evaluate the existing system for its preparedness and ability to combat the rising burden of diseases.

Indian healthcare is organized into a three-tier system catering to primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of care.[13] In the majority of countries across the world including India, the oral health care system has essentially been a sub-specialty of medicine rather than a unique or separate entity.[14]

Kerala is a relatively small state situated in the south-western part of peninsular India and constitutes 2.7% of the national population. This state is hailed for having one of the best indicators of health, which are often compared to the developed nations globally.[15] According to the National Census 2011 statistics, the state has the lowest infant and maternal mortality rates. Sex ratio and literacy levels are the highest making it the state with the best Human Development Index. The 'Kerala model of health' has been synonymous with low cost and universal accessibility and availability of health care to all sections of the society.[16] Despite the best vital health indicators, there has been an increase in the burden of non-communicable and lifestyle diseases.[17,18] The burden of oral diseases is also on the rise and with oral health being an issue of 'international neglect' by policymakers,[19] the capacity of the existing health system to overcome these challenges is uncertain.

The issue of political neglect is reflected in fewer number primary healthcare centers offering oral care coupled with the unregulated and highly skewed growth of the private sector into medical and dental care. It is an irony that while 80% of the dentists work in urban areas, around 70% of the Indian population lives in rural areas[20] making health care a commodity that follows an inverse square law.

To improve the system and bring about a policy change, a systematic analysis of the existing oral health system is necessary. A strong health system ensures that people and institutions, both public and private, effectively undertake core functions to improve health outcomes[21] and is built on several key attributes outlined by Tomar and Cohen.[22]

The objective of this review was to assess the oral healthcare system of Kerala with regard to the World Health Organization's core indicators to assess health systems and identify potential strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

Methodology

This study adopted a mixed methodological approach wherein data were obtained from various primary and secondary sources. To ensure comprehensiveness, the gray literature sources were solicited from newspaper reports, unpublished university-accepted dissertations, and websites of organizations related to oral care delivery.

The tool for oral health system assessment was based on the WHO's method on “Framework for action“ on health systems, which describes six 'Health System Building Blocks' (viz. service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, access to essential medicines, health financing, and leadership and governance) that together constitute a complete system [Figure 1].[23,24] The indicators used for assessing each building block were customized to adapt to the needs of oral health care assessment. Secondary sources included epidemiological studies conducted on oral diseases (dental caries, periodontal disease, malocclusion, dental fluorosis, and oral cancer) in Kerala retrieved from MedLine and Google Scholar database, data from National Oral Health Survey and Fluoride Mapping (2002-03), and official websites of Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, Directorate of Health Services and Medical Education, Government of Kerala, Dental Council of India and Indian Medical Association, Kerala State.

Figure 1.

Building blocks of health systems

Primary data involved collection of information referring to the objectives of the study by undertaking healthcare facility survey of a representative sample of public sector institutes offering oral care, survey of a sub-sample of pharmacies in the state, Key Informant Interviews (KII) with dentists employed in these centers and office bearers of professional associations related to oral care in Kerala for obtaining secondary data and by means of Right To Information Act (RTI) from the central and state governments.

Oral health system assessment tool

The customized WHO health system assessment tool utilized the indicators given in Table 1 for analyzing the six building blocks of oral health systems.[24] Access to essential medicines was assessed using an essential drug list incorporating the first-line drug constituted for common dental conditions like aphthous ulcer, dental pain/inflammation, dental infections, dental decay, and dentinal hypersensitivity. The indicators used were the availability and median price for one unit of the lowest-priced equivalent drug available in the pharmacy. The median price was calculated from the reference prices obtained from the international drug price indicator guide.[25]

Table 1.

Summary of key oral health system assessment indicators of Kerala

| Sl. No. | Indicators | Figures | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Service delivery indicators | |||

| 1 | Number of government sector hospitals offering dental care | 112 | |

| 2 | Number of government hospitals for 1 lakh population | 0.3 | |

| 3 | Number of private clinics per 1 lakh population | 4.9 | |

| 4 | Predominant service delivery method | Private | |

| Oral health workforce indicators | |||

| 5 | Number of dentists working in government sector (DHS and DME) | 286 | |

| 6 | Proportion of dentists working in government sector | 2% | |

| 7 | Number of dentists registered with Kerala Dental Council (Dec 2015) | 15183 | |

| 8 | Number of dentists registered with Indian Dental Association (Kerala) | 4209 | |

| 9 | Number of dentists per 1 lakh population | 4.54 | |

| 10 | Dentist population ratio | 1:2200 | |

| 11 | Number of dental colleges | Government | 5 |

| Private | 21 | ||

| 12 | Number of BDS seats per year | 1880 | |

| 13 | Number of MDS seats per year | 201 | |

| 14 | Annual number of dental graduates per 1 lakh population | 6.22 | |

| 15 | Number of dental hygienists | 509 | |

| 16 | Number of dental mechanics | 743 | |

| 17 | Hygienist to dentist ratio | 0.03 | |

| 18 | Technician to dentist ratio | 0.05 | |

| Access to essential medicines | |||

| 19 | Average availability of essential medicines for dentistry in pharmacies | 60% | |

| Median consumer price ratio | 3.26 | ||

| Health financing indicators | |||

| 20 | GDP spent on health care (India) | 1.04 (2011) | |

| 21 | Oral health expenditure as a percentage of total health expenditure | NA | |

| 22 | Predominant mode of payment for dental services | OOP | |

| 23 | Coverage for dental procedures in state government schemes | Nil | |

| Health information system indicator | |||

| 24 | Health Information System (Reporting of dental procedures through HMIS) | Present | |

Healthcare Facility survey was undertaken to get secondary data regarding the delivery of oral care across the state. With prior official sanction, a sample of nine centers offering dental care in public and private sector (one primary health center, community health center, taluk (sub-district) hospital, district hospital, general hospital, and four private dental clinics) were surveyed for assessing various aspects of oral care delivery (manpower, infrastructure, patient attendance, treatments done, cost of treatment, prevention-related activities). The assessment was done in the form of KIIs using semi-structured interview guides for collecting data from their records. The key informants were the dentists working in these health centers.

Oral health outcomes

The oral health status, expressed in terms of the prevalence of oral diseases (dental caries, periodontal diseases, malocclusion, oral cancer, and dental fluorosis) was obtained through population-based oral health studies conducted in the state for the past 25 years in Kerala (1990-2015). The combined prevalence was calculated according to WHO index age groups (5, 12, 15, 35-44, and 65-74) for oral diseases where sufficient data were available.

Dental education

An appraisal of the dental education system in the state was done using desk review. Information was obtained on the number and annual intake of colleges offering undergraduate, postgraduate, and allied courses in dentistry. Data for the same were obtained from the Dental Council of India website.

Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis

A SWOT analysis was carried out based on the obtained information after deliberations among the authors.

Results

Kerala is divided into 14 districts having a total population of 33,406,061[26] and a population density of 860/sq.km. The state contributes 3.78% of the national gross domestic product.[27] Agriculture and related industries form the major occupation of the people of this state.

Health system in Kerala

The state has a three-tier-system of health care—the Primary Health Centers (PHC), Community Health care Center (CHC), Taluk and District hospital and Medical Colleges evenly distributed in the rural and urban areas. Apart from this, there is an extensive network of medical care institutions practicing homeopathy and Ayurveda in government, voluntary, and private sectors.[16] One of the characteristics of the private medical sector in Kerala is that it is comprehensive in nature and there has also been substantial growth in institutions that cater to traditional medical systems like Ayurveda.[28] Each sub-center caters to around 6000 people, one PHC to 40,000 people, one CHC to 1,45,000 people, and 1 taluk hospital to 4,22,000 people. This almost adheres to the recommended structure proposed by the Govt. of India[29,30,31] and can be well established that the government has well been able to reach out to the population in terms of the availability of healthcare institutes. This achievement is significant compared to the scenario that exists in other states of the country.[32]

The delivery of oral care in Kerala is basically through institutions administratively headed by Directorate of Health Services (public sector hospitals), Directorate of Medical Education (government dental colleges), and private sector (self-funded dental colleges and private hospitals and clinics).

Oral health system assessment

The summary of indicators used to assess the six building blocks and its results are described in Table 1.

Dental education

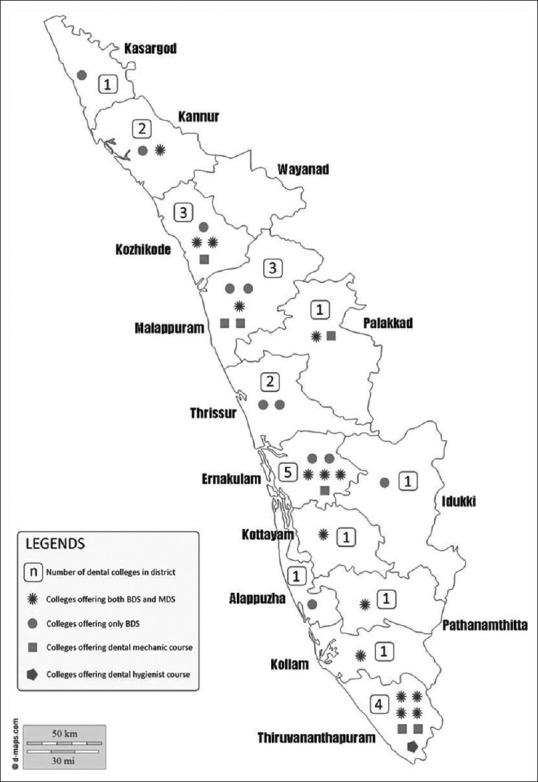

In Kerala, dental education in the government sector is managed by the Directorate of Medical Education, which works under the Department of Health and Family Welfare. The state has five government and 21 private dental schools with a combined output of 2100 graduates and postgraduates [Figure 2]. Dental hygienist certificate and dental mechanic certificate courses were the allied and supplementary dental courses offered in one and seven dental schools, respectively.

Figure 2.

Overview of dental education in Kerala

Oral health outcomes

The burden of common oral diseases estimated from various population-based studies is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of burden of oral diseases in Kerala

| Condition | Category | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| Dental caries | 12 years | 37-69% (combined prevalence-40%) |

| Periodontal disease | 35-44 years | 65.3-78.6% |

| Malocclusion | 15 years | 53.3-80.4% |

| Oral cancer (Incidence/1 lakh population) | Males | 16.4-21.6 |

| Females | 6.4-9.1 | |

| Dental fluorosis | Endemic areas | 35-39% |

| Other areas | < 5% |

Discussion

Globally, oral health has not been accorded a priority in the healthcare system.[19] In India, the majority of health programs are designed to focus on control of infectious diseases and improving reproductive and child health. It does not provide resilience to deal with other newer epidemics like non-communicable diseases, mental health, oral health etc., Oral health, probably due to its low mortality levels, has failed to gather enough attention among policymakers.[33] Except for a few isolated epidemiological studies, reliable data in oral disease burden is still deficient. Moreover, studies on the oral health system, considered as a social institution by itself, are lacking. Vital health indicators of the state are at par with many of the developed countries across the world facilitating worthy comparisons.[15]

The strengths of this study lie in its comprehensiveness of data achieved by the process of data triangulation wherein information was collected from multiple sources including the RTI Act. To observe the functioning of public sector institutes offering dental care, primary data were collected through a health facility survey, which added more credibility to the findings. A SWOT analysis summarized the oral health care system in Kerala [Table 3].

Table 3.

SWOT analysis

| STRENGTHS | WEAKNESS |

|---|---|

| Organized healthcare system | Absence of oral care in grass-root levels (sub-center, PHC) |

| Mention of oral health in state’s health policy | Limited government hospitals offering oral care (approximately 8%) |

| Affordable oral care in PSU’s | Meager financial allocation for oral health activities |

| Essential medicines provided free of cost in PSU’s | No government sponsored oral health programs |

| Approx. 15,000 registered dentists | Uneven distribution of dentists and private dental facilities and high costs |

| 25 dental teaching institution with an output of 2000 dentists/year | Low perceived need for oral care |

| Healthy DPR-1:2200 | |

| THREATS | OPPORTUNITIES |

| Low priority of oral health in health system | Appointing a dentist in every PHC-effective use of large manpower |

| Rising burden of oral diseases | Planning a comprehensive school oral health program |

| Lack of political will to employ dentists in primary levels of care | Training allied workforce |

| Poor knowledge and attitudes of oral health among public | Introduction of public dental health insurance |

| Absence of an Oral Health Policy at national level | Effective utilization of dental teaching institutions as centers for oral health promotion |

| Lack of vertical oral health programs | Enhancing community participation |

Service delivery

Though public sector institutes (government hospital and dental teaching institutions) are offering affordable oral care services in Kerala, the lack of dental care at primary levels of care (PHC) is denying the people an opportunity to avail dental care. This translates to a situation where people are forced to consult a general health practitioner or private oral healthcare facility to meet their dental needs causing an escalation in treatment costs. A situation is akin to other developing countries like Nigeria where the private sector predominates over the public sector and services are directed towards the provision of curative and rehabilitative care.[34] This is in contrast to countries like United Kingdom, which offers all types of oral care through the National Health System to all its citizens.[35] Oral care in public sector (56.4%) is also well established in Malaysia.[34] With Kerala having a well-organized network of public sector hospitals both in number and distribution, integrating oral health into these services is only a matter of political will.

The contribution of the private sector in health care in India has been phenomenal considering its growth from 8% during independence (1947) to 80% in 2012. Though health care in the private sector has also grown substantially in Kerala, its coverage (63%) has been below the national average.[36] However, in contrast, 98% of dental care is offered by the private sector and the services in the public sector are virtually non-existent (2%). The demand for superior quality of services has increased in private care whereas economic considerations seem to be the major reason for choosing government services.[37] But, these centers have focused their attention on providing secondary and tertiary oral care services limiting the beneficiaries to a minority who can afford the high treatment costs. Contrary to other disease conditions, the presence of civil societies in facilitating oral care has been minimal.

Thus, it can be summarized that the basic foundations of equitable health care; viz. accessibility and affordability are challenged in the oral healthcare system of the state.

Workforce

The precise estimation of the total number of professionally active oral healthcare workforce in any country is an onerous task. The data from the central registries like the Dental Council of India (licentiate to practice) is not an accurate predictor of the active oral health workforce due to the lack of real-time monitoring of the practitioners. Kerala's dentist population ratio (DPR) is 1:2200, which is higher than the national average (India) of 1:10,000[38] and recommended ratio by WHO (1:7500).[39] This figure could be an overestimation due to the effects of cross-cutting problems like migration, retirement, voluntary withdrawal from service, multiple job holdings, absenteeism, and ghost workers.[40] Contrary to China, which has an annual reporting system of health workers in both public and private sectors, India's database is largely deficient.[41] The largest professional non-governmental body for oral health (Indian Dental Association, Kerala state) reports an active workforce of 4209 as of 2015. Only 2% of the dentists work in the public sector, which is very low compared to countries like South Africa and Denmark (20%).[42,43] The figures are comparable with Belgium where less than 5% of dentists work in public sector but with compulsory social insurance for all its citizens, dental care is more affordable. A comparison of oral health indicators of Kerala with few developed and developing countries around the globe is given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of oral health systems of various countries across the world

| Name of country | DPR (per 10000 popln) | TOHCE as a % of THCE | Prevalence of caries at age 12 | Finance | Coverage | Predominant service delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States of America | 6 | 4 | 59.1 | PI | PI | Pri |

| United Kingdom | 5 | 4.1 | 33.4 | OOP | PUI | Pub |

| France | 6.7 | 4.6 | - | OOP | PUI | Pri |

| Canada | 5.9 | 7.4 | 38.7 | OOP | PI | Pri |

| Belgium | 8 | 0.3 | - | PUI | PUI | Pri |

| Denmark | 8 | 0.19 | - | PUI | PI | Pri |

| South Africa | 0.8 | - | - | OOP | PUI | Pri |

| Nigeria | 0.2 | 0.61 | 30 | OOP | PUI | Pri |

| Brazil | 11.4 | 1.8 | - | OOP | PUI | Pri |

| China | 1 | 0.3 | - | OOP | PUI | Pub |

| Malaysia | 1.9 | 0.2 | 90.3 | OOP | PUI | Pri |

| Kerala | 4.5 | - | 40 | OOP | NC | Pri |

PI-private insurance; PUI-public insurance; OOP-out-of-pocket; Pri-Private sector; Pub-Public sector; NC-No coverage. TOHCE: Total Oral Health Care Expenditure

Health information systems

The absence of a surveillance system for oral diseases is probably due to its perceived low mortality levels. While oral cancer surveillance is done through hospital and population-based cancer registries, other oral diseases have not been deemed notifiable making estimation of its burden difficult. However, district-wise website-based reporting of number of dental treatments carried out in government sector hospitals gives a fair indication of the health-seeking behavior of the people.

Access to essential medicines

The Millennium Development Goals mention access to essential medicines as one of its indicators [MDG 8, Target 17].[44] This study undertook a survey of a sub-sample of pharmacies using an essential medicine list for dentistry developed by the authors. The average availability of essential medicines was 60% in the pharmacies whereas the median consumer price ratio was 3.26. Such a list was being used for the first time in the assessment of health systems due to which comparisons were not possible. Provision of essential antibiotics and analgesics was free of cost in pharmacies attached to public sector hospitals making oral care affordable to its beneficiaries.

Health financing

India spends less than 2% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on healthcare. Data were unavailable for the share of oral health from the total healthcare expenditure. Developed countries like the United States of America, the United Kingdom, and France spend close to 4% of their total expenditure on oral health whereas developing countries like Brazil and Malaysia spend less than 1% of their health budget on oral health. The absence of any organized program for oral health in Kerala also limits the budget allocated to oral activities. Though the National Oral Health Care Program has been piloted in various states since 1999 across the country including Kerala, information on fund allocation for the same is not available. Without adequate funding, access to effective healthcare cannot be ensured.

In the context of payment for dental services, it was observed in the present study that the cost of dental care in a private health facility is almost 40 times the cost in the public health sector. The major mode of payment is the traditional out-of-pocket/fee-for-service. Only treatments requiring hospitalization are insured by private firms.

Leadership and governance

There is no oral health policy at the state or national level. Isolated attempts have been made in introducing the same but no substantial progress has been made. A mention of oral health has been made in the draft of the state's health policy 2013 but implementation is far from adequate.[45] Under the National Health Mission, there has been financial allocation for National Oral Health Program in several states.[46] The details of the Kerala state were not available on request. Ayushman Bharat, India's flagship and world's biggest health reform, aims to provide families in India with an annual insurance cover of INR 500,000 for covering secondary and tertiary care in empanelled public and private hospitals.[47] The silver lining, however, is that oral health does find a mention in the list of services/packages provided under this scheme. Yet, the lack of protection for outpatient services or expenditure for medicines would negatively impact oral health services, most frequently outpatient care.[48]

Social service and cause-oriented organizations have an important role to play in the healthcare delivery system of India. Few non-governmental organizations have been associated with oral care in India. These 'third sector' organizations usually share distinct characteristics; they possess an internal administrative structure, are structurally separate from the government, and are not profit-oriented.[49] But most of these voluntary organizations work for restoring oral health with limited importance for preventive care.

With a theoretically healthy dentist population ratio but still having accessibility and affordability issues coupled with the threat of unemployment looming large for fresh graduates, this paper calls for the creation of dental posts in the wide network of public healthcare establishments offering primary care (primary health centers and community health centers).

Mostafa et al. in their paper discuss that oral health policy issues need to be analyzed more comprehensively and recommend researchers undertaking oral health system analysis among others to answer policy-learning questions.[50] Likewise, authors of this study propose the need to develop validated indicators for the assessment of oral health system to facilitate effective comparison between other states and countries. The findings of this research could be useful in providing baseline data to appraise policymakers regarding ramifications of poor oral health of people and also provide directions for future research on oral health systems.

Conclusion

Kerala has matched international standards in most of the health indicators. However, as far as oral health is concerned, this state has a long way to go with regard to oral health literacy, provision, access, and utilization of oral care. As per the existing data available, it is evident that the presence of dentists in government-run healthcare establishments is largely inadequate. Hence, the first effective point of contact for oral health in the state becomes secondary and tertiary care hospitals rather than the primary health care facility. The lack of oral care in public sector hospitals has paved the way for the expansion of a highly skewed and unregulated private oral care compromising on equity issues like accessibility and affordability.

Author contribution

Chandrashekar Janakiram: Concept, design, definition of intellectual content, data analysis, manuscript editing, manuscript review

R. Venkitachalam: design of study, definition of intellectual content, literature search, data acquisition, data analysis, manuscript preparation, manuscript review

Joe Joseph: design of study, definition of intellectual content, data acquisition, manuscript editing, manuscript review

Krishnakumar K: design of study, definition of intellectual content, data acquisition, data analysis, manuscript review

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Rajeev BR and Dr. Ramesh R., (Deputy Director, Directorate of Health Services, Government of Kerala) for their support. This is a self-funded study.

References

- 1.Moimaz SA, Saliba O, Marques LB, Garbin CA, Saliba NA, Moimaz SA, et al. Dental fluorosis and its influence on children's life. Braz Oral Res. 2015;29:1–7. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2015.vol29.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colak H, Dülgergil CT, Dalli M, Hamidi MM. Early childhood caries update: A review of causes, diagnoses, and treatments. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2013;4:29–38. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.107257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford PJ, Farah CS. Early detection and diagnosis of oral cancer: Strategies for improvement. J Cancer Policy. 2013;1:e2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batchelor P. Is periodontal disease a public health problem? Br Dent J. 2014;217:405–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richard Watt. Strategies and approaches in oral disease prevention and health promotion. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:711–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scutchfield FD, Keck CW. Principles of Public Health Practice Cengage Learning. 2003:574. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aubrey Sheiham, Richard Watt. Prevention of Oral Diseases. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. Oral health prevention and policy; pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- 8.FDI World Dental Federation. FDI policy statement on non-communicable diseases. Adopted by the FDI General Assembly: 30 August 2013-Istanbul, Turkey. Int Dent J. 2013;63:285–6. doi: 10.1111/idj.12078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheiham A, Watt RG. The common risk factor approach: A rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:399–406. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028006399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varenne B. Integrating oral health with non-communicable diseases as an essential component of general health: WHO's strategic orientation for the African region. J Dent Educ. 2015 May 79;:S32–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. What is the burden of oral disease? [Internet] WHO; 2016. Available from: http://wwwwhoint/oral_health/disease_burden/global/en/ Cited 2016 Jul 29. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Burden of Diseases in India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sumit K, Kumar S, Saran A, Dias FS. Oral health care delivery systems in India: An overview. Int J Basic Appl Med Sci. 2013;3:171–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cynthia Pine CBE, Rebecca Harris. Community Oral Health. 2nd ed. United Kingdom: Quintessence Publishing Co; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park K. Park's Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. 21st ed. Jabalpur: Banarsidas Bhanot; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.IT Department, Government of Kerala. Health-Kerala-States and Union Territories-Know India: National Portal of India [Internet] 2015. Available from: http://www.archive.india.gov.in/knowindia/state_uts.php?id=60 . Cited 2015 Dec 29.

- 17.Arogyakeralam-State Health and Family Welfare Society. National Rural Health Mission [Internet] 2016. Available from: http://wwwarogyakeralamgovin/ Cited 2016 Feb 11.

- 18.Good Life. Kerala Health Statistics, Public Health Status of Kerala [Internet] Indus Health Plus. 2016. Available from: http://wwwindushealthpluscom/kerala-health-statisticshtml . Cited 2016 Jun 20.

- 19.Benzian H, Hobdell M, Holmgren C, Yee R, Monse B, Barnard JT, et al. Political priority of global oral health: An analysis of reasons for international neglect. Int Dent J. 2011;61:124–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahuja N, Parmar R. Demographics and current scenario with respect to dentists, dental institutions and dental practices in India. Indian J Dent Sci. 2011 Jun 2;:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Health Systems 20/20. The Health System Assessment Approach-A How-to manual Vol Version 2. 2012. Available from: wwwhealthsystemassessmentorg .

- 22.Tomar SL, Cohen LK. Attributes of an ideal oral health care system. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70:S6–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. Systems Thinking-For Health Systems Strengthening. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and Measurement Strategies. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frye JE. International Drug Price Indicator Guide Management Sciences for Health. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Census 2011. Census provisional population totals 2011 [Internet] 2011. Available from: http://censusindiagovin/2011census/censusinfodashboard/indexhtml . Cited 2015 May 12.

- 27.Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation. GDP of Indian States | Indian states GDP 2015-StatisticsTimescom [Internet] 2015. Available from: http://statisticstimescom/economy/gdp-of-indian-statesphp . Cited 2016 Jan 19.

- 28.Kerala State Industrial Development Corporation. Private Hospitals Lead the Way in Kerala's Health Sector [Internet] KSIDC. Available from: http://blogksidcorg/private-hospitals-lead- the-way-in-keralas-health-sector/ Cited 2015 Dec 6.

- 29.Guidelines for Primary Health Centres Directorate General of Health Services Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. 2012 Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS) Guidelines for Community Health Centres Directorate General of Health Services Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS) Guidelines for Sub-District/Sub-Divisional Hospitals (31 to 100 Bedded) Directorate General of Health Services Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bajpai V. The challenges confronting public hospitals in India, their origins, and possible solutions. Adv Public Health. 2014;2014:e898502. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tewari A. National oral health policy-Draft plan. J Indian Dent Assoc. 1986;58:378–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norliza Mohamed. Oral Health Care for School Children in Malaysia The 8th Asian Conference of Oral Health Promotion for School Children Taiwan. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neumann DG, Quinonez C. A comparative analysis of oral health care systems in the United States, United Kingdom, France, Canada, and Brazil. NCOHR Work Pap Ser. 2014;1:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lekshmi S, Mohanta GP, Revikumar KG, Manna PK. Developments and emerging issues in public and private health care systems of Kerala. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;6:92–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dilip TR. Role of Private Hospitals in Kerala: An Exploration Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies. 2008. Available from: http://opendocsidsacuk/opendocs/handle/123456789/3105 . Cited 2015 Dec 4.

- 38.Thomas S. Plenty and scarcity. Br Dent J. 2013;214:4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dagli N, Dagli R. Increasing unemployment among Indian Dental Graduates-High time to control dental manpower. J Int Oral Health JIOH. 2015;7:i–ii. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bossert T, Bärnighausen T, Bowser D, Mitchell A, Gedik G. Assessing Financing, Education, Management and Policy Context for Strategic Planning of Human Resources for Health. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anand S, Fan V. Health Workforce in India Human Resourecs for Health Observer Series No 16. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kandelman D, Arpin S, Baez RJ, Baehni PC, Petersen PE. Oral health care systems in developing and developed countries. Periodontol. 2000;2012(60):98–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Wyk PJ, van Wyk C. Oral health in South Africa. Int Dent J. 2004;54:373–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization. Health and the Millenium Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Health Policy Kerala-Draft Government of Kerala. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Oral Health Programme-Governnment of India [Internet] 2015. Available from: http://nrhmgovin/national-oral-health-programmehtml . Cited 2016 Jun 16.

- 47.The Lancet. India's mega health reforms: Treatment for half a billion. Lancet. 2018;392:614. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31936-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nandita V, Venkitachalam R. Universal oral health coverage: An Indian perspective. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2019;17:266–8. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mubeena O, Akram M. Role of third sector in promoting health outcomes in Kerala: A sociological study. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2016;3:30–6. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mozhdehifard M, Ravaghi H, Raeissi P. Application of policy analysis models in oral health issues: A Review. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2019;9:434–44. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_252_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]