Figure 1.

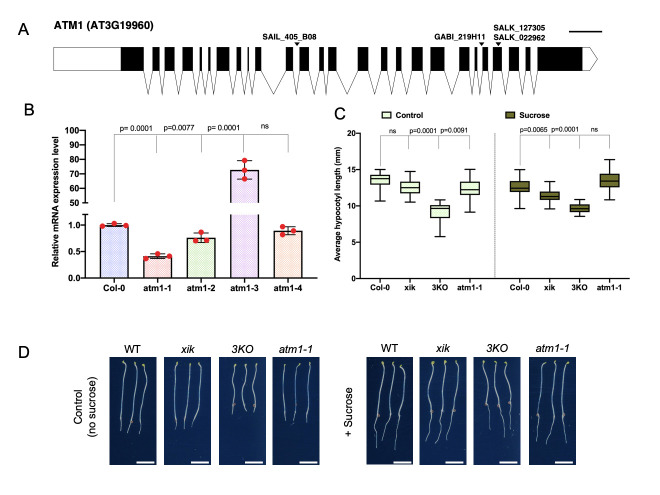

(A) Schematic gene structure of ATM1 (AT3G19960) indicating the T-DNA insertions assayed in this study: SAIL_405_B08 (atm1-1), SALK_127305 (atm1-2), GABI_209H11 (atm1-3), and SALK_022962 (atm1-4). Black boxes and lines depict exons and introns respectively. Scale bar is 100 bases. (B) ATM1 transcript levels in different alleles (atm1-1, atm1-2, atm1-3, and atm1-4) compared to Columbia Ecotype (Col-0) assayed by quantitative PCR (qPCR). (C) Average hypocotyl length of seedlings grown on 0.5X Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium with or without 15 mM sucrose in the dark for 5 days. A total of 30-40 seedlings were evaluated and the assay was replicated three times (panel shows the results from one experiment). Error bars show standard error. P values are calculated using one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparisons; ns: not significant. (D) Hypocotyl phenotypes after 5 days of incubation in continuous darkness. Scale bar: 5mm

Description

The ability of developing seedlings to respond and adapt to diverse environmental conditions including light is critical for their emergence and establishment (Benvenuti et al., 2001; Forcella et al., 2000; Salter et al., 2003; Yu and Huang, 2017). Cell expansion within the hypocotyl optimizes light and energy capture by the cotyledons, and enables the transition to autotrophic status (Botterweg-Paredes et al., 2020; Dowson‐Day and Millar, 1999; Oh et al., 2013). Hypocotyl elongation is regulated by multiple factors including temperature, phytohormones, circadian clock and light (Dowson‐Day and Millar, 1999; Ma et al., 2016; Procko et al., 2014; Reed et al., 2018; Yu and Huang, 2017). Endogenous and exogenous sugars are also important regulators of hypocotyl cell expansion (Lilley et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2011; Pfeiffer and Kutschera, 1995; Simon et al., 2018b; Singh et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2010, 2015). Under constant darkness, the interaction between plant hormones such as brassinosteroid and gibberellin and sugar signalling is proposed to stimulate increase in hypocotyl length (Simon et al., 2018b; Zhang et al., 2010, 2015). Hypocotyl phenotypes are important tools in plant biology as they have been used to screen for mutants with altered responses to light and sugar signalling and some of the identified genes have revolutionized plant research (Nakano, 2019). In multicellular organisms, actomyosin-dependent transport constitutes an essential component of the cellular structure and dynamics (Duan and Tominaga, 2018; Kurth et al., 2017; Peremyslov et al., 2010). The Arabidopsis genome encodes 17 myosins classified into two distantly-related groups comprising 4 class VIII myosins and 13 class XI plant myosins (Haraguchi et al., 2019; Reddy and Day, 2001; Ryan and Nebenführ, 2018). The plant-specific-myosin XI has been implicated in diverse developmental processes (Cai et al., 2014), but the contribution of members of class VIII myosins including myosin1/ATM1 to plant development stills remains elusive.

Here, we analyzed the role of plant myosins in sucrose-induced hypocotyl elongation under continuous darkness conditions. To start the molecular characterization of ATM1 (AT3G19960), we analyzed four T-DNA insertional alleles (Fig. 1A), and mutations were confirmed via PCR-based genotyping. We also performed RT-qPCR to quantify ATM1 transcripts in the four alleles, of which atm1-1 (SAIL_405_BO8 previously described by Haraguchi et al., 2014) showed reduced ATM1 expression among these alleles compared to the wild type (Fig. 1B). Notably, atm1-3 exhibits increased mRNA levels and may be a overexpression allele. Since atm1-1 had the lowest ATM1 transcript level, and was previously described as a null (Haraguchi et al., 2014) we decided to use this allele for further phenotypic analysis. To understand the contribution of plant myosins in sugar-regulated hypocotyl cell expansion we performed growth assays using Col-0 (WT: wild-type), atm1-1, a class XI myosin single gene mutant (xik) and the triple knockout line (3KO; xi1 xi2 xik). This triple mutant was previously generated using SALK insertion lines in XI-K (SALK_067972; At5g20490), XI-1 (SALK_019031; At1g17580) and XI-2 (SALK_055785; At5g43900) (Prokhnevsky et. al., 2008; Valera et. al., 2010). All genotypes were grown on 0.5X Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium without or with 15 mM sucrose under constant darkness for 5 days. Under the sucrose-free condition (control), all the three myosin mutants showed reduced hypocotyl length compared to the WT plants (Fig. 1C and D), suggesting the role of myosins in cell elongation. Specifically, the 3KO mutant was severely impaired in hypocotyl cell expansion in the absence of sucrose when compared to the single mutants, hinting that this gene family may redundantly regulate plant development. In the presence of sucrose under constant darkness, the short hypocotyl phenotype was not fully rescued when compared to the WT plants except for atm1-1.

Altogether our findings suggest that plant-specific myosins may be involved in sugar-regulated hypocotyl elongation under continuous darkness. These myosins have diverse subcellular localization patterns (Haraguchi et al., 2014; Peremyslov et al., 2012, 2008) and thus may represent a new downstream signaling output following sucrose signals within the developing shoot. Sucrose-induced hypocotyl elongation has been linked to brassinosteroid, gibberellins, phytochrome interacting factors (PIFs) and SnRK1 (Sucrose Nonfermenting Kinase 1) signaling (Laxmi et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2011; Simon et al., 2018a; Zhang et al., 2015, 2010; Zhang and He, 2015). Other proteins that are important for this process include TANG1 (Zheng et al., 2015), a WD40 protein AtGHS40 (Hsiao et al., 2016), a plant-specific protein SR45 (Carvalho et al., 2010), and HIGH SUGAR RESPONSE 8 (HSR8) (Li et al., 2007). Further studies will be needed to determine how these molecular factors work in concert or parallel to regulate skotomorphogenesis.

Methods

Plant materials

Arabidopsis thaliana plants used in this study were Columbia (Col-0) ecotype: SAIL_405_B08 (atm1-1), SALK_127305C (atm1-2), GABI_219H11(atm1-3) and SALK_022962C (atm1-4) and previously described (xik) and 3KO triple knockout line (xi1 xi2 xik) (Peremyslov et al., 2012, 2010, 2008). Seeds were surfaced sterilized using 50% bleach and 0.01% Triton X-100 for 10 min and then washed five times with sterile water. Seeds were then imbibed in sterile water for 2 days at 4 °C and then transferred to 0.5X Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium plates supplemented without/with 15mM sucrose. For hypocotyl elongation, plates were incubated in the light for 6 hours prior to incubation in the dark for 5 days at 22 °C. PCR based genotyping of the mutants was performed with primers listed in Table 1 and 2X DreamTaq polymerase master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Real time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Plant materials were harvested from 7-day old seedlings in three biological replicates. RNA samples were extracted with ZYMO RESARCH Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Plus Kit and quality was spectrophotometrically measured with the Nanodrop. cDNA synthesis was performed with SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase kit according to manufacturer’s instruction. The samples were run on BIO RAD CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System with the following components per reaction of 20µL volume: 10µL iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix, 0.6 µL Forward Primer F (300nM), 0.6 µL Reverse Primer F (300nM) and 3µL cDNA (5ng/ul). No cDNA samples (water) were included as negative control. Cycling conditions were 5 min at 95 °C, followed by cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 60 °C and 30 s at 72 °C. Data acquisition was done at the end of every cycle. The samples were prepared in three biological and two technical repeats. The Comparative CT Method (ΔΔ CT Method) was used for the analysis of Ct values whereby the amount of target, normalized to an endogenous reference and relative to a calibrator and is given by 2 –ΔΔCT.

Hypocotyl length and statistical analysis

Five-day old dark-grown seedlings were imaged using an Epson Perfection V600 Photo Scanner. Hypocotyl length was measured with ImageJ. For each experimental treatment, 30-40 seedlings were measured for each genotype. The assays were repeated three independent times with similar results. GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, version 8.4.2) was used for statistical analysis. To compare treatments effects on the mean value of wild type and mutants, either or one- or two-way ANOVA was performed using Tukey’s test for multiple comparison.

Gene diagram annotation

The diagram of ATM1 (AT3G19960) was created using the Exon-Intron Graphic Maker (http://wormweb.org/exonintron) using current gene model sequence from TAIR (www.arabidopsis.org). The position of all T-DNA alleles examined was obtained from the SALK SIGnAL T-DNA express Arabidopsis Gene Mapping tool (http://signal.salk.edu/cgi-bin/tdnaexpress).

Reagents

Table 1: Primers used in this study.

| Primers | 5′ > 3′ Sequence | Purpose |

| SAIL_405_B08 LP | TTCGTGTGAACGTTGATTCTG | Genotyping |

| SAIL_405_B08 RP | TCCAGCTTGAATAGATGACGG | |

| SALK_127305_LP | TCCTCAAGCATCACCGTTAAC | |

| SALK_127305_RP | GCAGAGAGCTCAAGTGTTTGG | |

| GABI_219H11_LP | TAAGAGCGAGACAGAGAACCG | |

| GABI_219H11_RP | TCGTGGTTGGTTGGTTAGAAG | |

| SALK_022962_LP | GGGGAAACAGAGAGAAATTGG | |

| SALK_022962_RP | TTTGCTTTGGCATTAACCAAC | |

| Sail-LB2 | GCTTCCTATTATATCTTCCCAAATTACCAATACA | |

| LBb1.3 | ATTTTGCCGATTTCGGAAC | |

| GABI-8474 | ATAATAACGCTGCGGACATCTACATTTT | |

| ATM1_qPCR_Fw | CAGACAGAGAACTGAGGAGGC | RT-qPCR |

| ATM1_qPCR_Rv | CATCGAACCACTGCTCTCTTCG | |

| AT1G13320_Fw | GCGGTTGTGGAGAACATGATACG | |

| AT1G13320_Rv | GAACCAAACACAATTCGTTGCTG |

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Valerian Dolja (Oregon State University) for sharing seed stocks of the previously described (xik) and 3KO triple knockout lines (xi1 xi2 xik) (Peremyslov et al., 2008). All other seed stocks were obtained from the ABRC (Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center at Ohio State University).

Funding

This work was supported by an American Association of University Women Research Publication Grant to D.R.K. and Iowa State University start-up funds to D.R.K.

References

- Benvenuti, S., Macchia, M., Miele, S., 2001. Light, temperature and burial depth effects on Rumex obtusifolius seed germination and emergence. Weed Res. 41, 177–186.

- Botterweg-Paredes E, Blaakmeer A, Hong SY, Sun B, Mineri L, Kruusvee V, Xie Y, Straub D, Ménard D, Pesquet E, Wenkel S. Light affects tissue patterning of the hypocotyl in the shade-avoidance response. PLoS Genet. 2020 Mar 23;16(3):e1008678–e1008678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C, Henty-Ridilla JL, Szymanski DB, Staiger CJ. Arabidopsis myosin XI: a motor rules the tracks. Plant Physiol. 2014 Sep 18;166(3):1359–1370. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.244335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho RF, Carvalho SD, Duque P. The plant-specific SR45 protein negatively regulates glucose and ABA signaling during early seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010 Aug 10;154(2):772–783. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.155523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowson-Day MJ, Millar AJ. Circadian dysfunction causes aberrant hypocotyl elongation patterns in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1999 Jan 01;17(1):63–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z, Tominaga M. Actin-myosin XI: an intracellular control network in plants. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018 Jan 01;506(2):403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.12.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcella, F., Benech Arnold, R.L., Sanchez, R., Ghersa, C.M., 2000. Modeling seedling emergence. F. Crop. Res. 67, 123–139.

- Haraguchi, T., Duan, Z., Tamanaha, M., Ito, K., Tominaga, M., 2019. Diversity of Plant Actin–Myosin Systems BT - The Cytoskeleton: Diverse Roles in a Plant’s Life. In: Sahi, V.P., Baluška, F. (Eds.), . Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 49–61.

- Haraguchi T, Tominaga M, Matsumoto R, Sato K, Nakano A, Yamamoto K, Ito K. Molecular characterization and subcellular localization of Arabidopsis class VIII myosin, ATM1. J Biol Chem. 2014 Mar 17;289(18):12343–12355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.521716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao YC, Hsu YF, Chen YC, Chang YL, Wang CS. A WD40 protein, AtGHS40, negatively modulates abscisic acid degrading and signaling genes during seedling growth under high glucose conditions. J Plant Res. 2016 Jul 21;129(6):1127–1140. doi: 10.1007/s10265-016-0849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth EG, Peremyslov VV, Turner HL, Makarova KS, Iranzo J, Mekhedov SL, Koonin EV, Dolja VV. Myosin-driven transport network in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Jan 17;114(8):E1385–E1394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620577114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxmi A, Paul LK, Peters JL, Khurana JP. Arabidopsis constitutive photomorphogenic mutant, bls1, displays altered brassinosteroid response and sugar sensitivity. Plant Mol Biol. 2004 Sep 01;56(2):185–201. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-2799-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Smith C, Corke F, Zheng L, Merali Z, Ryden P, Derbyshire P, Waldron K, Bevan MW. Signaling from an altered cell wall to the nucleus mediates sugar-responsive growth and development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2007 Aug 10;19(8):2500–2515. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.049965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley JL, Gee CW, Sairanen I, Ljung K, Nemhauser JL. An endogenous carbon-sensing pathway triggers increased auxin flux and hypocotyl elongation. Plant Physiol. 2012 Oct 16;160(4):2261–2270. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.205575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Zhang Y, Liu R, Hao H, Wang Z, Bi Y. Phytochrome interacting factors (PIFs) are essential regulators for sucrose-induced hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. J Plant Physiol. 2011 Oct 15;168(15):1771–1779. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Li X, Guo Y, Chu J, Fang S, Yan C, Noel JP, Liu H. Cryptochrome 1 interacts with PIF4 to regulate high temperature-mediated hypocotyl elongation in response to blue light. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Dec 22;113(1):224–229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511437113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T. Hypocotyl Elongation: A Molecular Mechanism for the First Event in Plant Growth That Influences Its Physiology. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019 May 01;60(5):933–934. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcz060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S, Warnasooriya SN, Montgomery BL. Downstream effectors of light- and phytochrome-dependent regulation of hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2013 Mar 01;81(6):627–640. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0029-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peremyslov VV, Klocko AL, Fowler JE, Dolja VV. Arabidopsis Myosin XI-K Localizes to the Motile Endomembrane Vesicles Associated with F-actin. Front Plant Sci. 2012 Sep 01;3:184–184. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peremyslov VV, Prokhnevsky AI, Avisar D, Dolja VV. Two class XI myosins function in organelle trafficking and root hair development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008 Jan 01;146(3):1109–1116. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peremyslov VV, Prokhnevsky AI, Dolja VV. Class XI myosins are required for development, cell expansion, and F-Actin organization in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010 Jun 25;22(6):1883–1897. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.076315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, I., Kutschera, U., 1995. Sucrose metabolism and cell elongation in developing sunflower hypocotyls. J. Exp. Bot. 46, 631–638.

- Pollard TD, Cooper JA. Actin, a central player in cell shape and movement. Science. 2009 Nov 27;326(5957):1208–1212. doi: 10.1126/science.1175862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procko C, Crenshaw CM, Ljung K, Noel JP, Chory J. Cotyledon-Generated Auxin Is Required for Shade-Induced Hypocotyl Growth in Brassica rapa. Plant Physiol. 2014 Jun 01;165(3):1285–1301. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.241844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhnevsky AI, Peremyslov VV, Dolja VV. Overlapping functions of the four class XI myosins in Arabidopsis growth, root hair elongation, and organelle motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Dec 01;105(50):19744–19749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810730105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy AS, Day IS. Analysis of the myosins encoded in the recently completed Arabidopsis thaliana genome sequence. Genome Biol. 2001 Jul 01;2(7):RESEARCH0024–RESEARCH0024. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-7-research0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JW, Wu MF, Reeves PH, Hodgens C, Yadav V, Hayes S, Pierik R. Three Auxin Response Factors Promote Hypocotyl Elongation. Plant Physiol. 2018 Aug 23;178(2):864–875. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JM, Nebenführ A. Update on Myosin Motors: Molecular Mechanisms and Physiological Functions. Plant Physiol. 2017 Nov 21;176(1):119–127. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter MG, Franklin KA, Whitelam GC. Gating of the rapid shade-avoidance response by the circadian clock in plants. Nature. 2003 Dec 11;426(6967):680–683. doi: 10.1038/nature02174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NML, Kusakina J, Fernández-López Á, Chembath A, Belbin FE, Dodd AN. The Energy-Signaling Hub SnRK1 Is Important for Sucrose-Induced Hypocotyl Elongation. Plant Physiol. 2017 Nov 01;176(2):1299–1310. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NML, Sawkins E, Dodd AN. Involvement of the SnRK1 subunit KIN10 in sucrose-induced hypocotyl elongation. Plant Signal Behav. 2018 May 30;13(6):e1457913–e1457913. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2018.1457913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Gupta A, Singh D, Khurana JP, Laxmi A. Arabidopsis RSS1 Mediates Cross-Talk Between Glucose and Light Signaling During Hypocotyl Elongation Growth. Sci Rep. 2017 Nov 23;7(1):16101–16101. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16239-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Huang R. Integration of Ethylene and Light Signaling Affects Hypocotyl Growth in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2017 Jan 24;8:57–57. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, He J. Sugar-induced plant growth is dependent on brassinosteroids. Plant Signal Behav. 2015;10(12):e1082700–e1082700. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2015.1082700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu Z, Wang J, Chen Y, Bi Y, He J. Brassinosteroid is required for sugar promotion of hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis in darkness. Planta. 2015 May 22;242(4):881–893. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2328-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu Z, Wang L, Zheng S, Xie J, Bi Y. Sucrose-induced hypocotyl elongation of Arabidopsis seedlings in darkness depends on the presence of gibberellins. J Plant Physiol. 2010 Apr 28;167(14):1130–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Shang L, Chen X, Zhang L, Xia Y, Smith C, Bevan MW, Li Y, Jing HC. TANG1, Encoding a Symplekin_C Domain-Contained Protein, Influences Sugar Responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015 May 22;168(3):1000–1012. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]