Abstract

Background

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with severe psychiatric presentations and has been linked to variability in brain structure. Dimensional models of borderline personality traits (BPT) have grown influential; however, associations between BPT and brain structure remain poorly understood.

Methods

We tested whether BPT are associated with regional cortical thickness, cortical surface area, and subcortical volumes (n=152 brain structure metrics) in the Duke Neurogenetics Study (DNS; n=1,299), and Human Connectome Project (HCP; n=1,099). Positive control analyses tested whether BPT are associated with related behaviors (e.g., suicidal thoughts and behaviors, psychiatric diagnoses) and experiences (e.g., adverse childhood experiences).

Results

While BPT were robustly associated with all positive control measures, they were not significantly associated with any brain structure metrics in the DNS or HCP, or in a meta-analysis of both samples. The strongest findings from the meta-analysis showed a positive association between BPT and volumes of the left ventral diencephalon and thalamus (ps<0.005 uncorrected, pFDRs>0.1). Contrasting high and low BPT decile groups (N=552) revealed no FDR-significant associations with brain structure.

Conclusions

We find replicable evidence that BPT are not associated with brain structure, despite being correlated with independent behavioral measures. Prior reports linking brain morphology to BPD may be driven by factors other than traits (e.g., severe presentations, comorbid conditions, severe childhood adversity, or medication) or reflect false positives. The etiology and/or consequences of BPT may not be attributable to MRI-measured brain structure. Future studies of BPT will require much larger sample sizes to detect these very small effects.

Keywords: borderline personality, brain structure, personality trait, suicidal thoughts, impulsivity, alcohol

INTRODUCTION

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a severe form of psychopathology characterized by affective instability, interpersonal dysfunction, identity disturbance, and impulsivity. It has a lifetime prevalence of 5.9% in the United States (1), is overrepresented in clinical outpatients (10–12%) and inpatients (20–22%) (2), and is associated with high rates of suicide (nearly 10% complete, 75% attempt) (3, 4), comorbid psychopathology, treatment utilization (5), and poor treatment response (6). However, despite the widespread individual and societal consequences of BPD (3), and its centrality to general personality dysfunction (7), remarkably little is known about its etiology and neurobiological correlates.

A nascent literature based predominantly on small patient samples (BPD patient Ns=7–76) has begun to examine brain structure correlates of BPD with meta-analyses (BPD patient Ns=104–395) and individual studies providing evidence that BPD is associated with reduced volume of corticolimbic structures (8–16), including the hippocampus, (10–14), amygdala (12, 14, 16), and medial prefrontal cortex (8, 15). These differences are located in regions critical for cognitive functions including affective processing and decision making, among others (17–21), leading to speculation that they may contribute to the expression of BPD (22). However, these findings arise from small samples that may be more prone to generate false positive and negative results, and have been largely constrained to region of interest analyses based on a priori hypotheses about the particular brain regions (i.e. corticolimbic structures, primarily the amygdala and hippocampus) that may play a role in the pathology.

A growing body of work suggests that dimensional trait models of personality disorders, including BPD, are clinically useful, valid, and reliable (23). Recent developments in the dimensional, trait-based assessment of BPD (24) enable investigation of BPD-associated personality traits in large unselected samples that are well-powered for analyses unconstrained by prior knowledge. A recently developed BPD-associated metric (the FFI-BPD) from the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (25) converges with explicit measures of BPD (rs = 0.35–0.72), correlates with a time-invariant component of borderline pathology (r=0.81), is heritable (40%) with evidence of substantial genetic correlation with explicit BPD measures (rG=.84), and demonstrates a highly similar profile of correlations with clinical criterion variables (e.g., childhood sexual abuse, depression) (24–27).

In the current study, we examined whether this borderline personality trait (BPT) metric is associated with variability in cortical thickness, surface area, and subcortical volume in the Duke Neurogenetics Study (DNS; N=1,299) and Human Connectome Project (HCP; N=1,099). We hypothesized that BPT would be associated with reduced cortical thickness and surface area, and reduced subcortical volume, particularly of corticolimbic regions. Such evidence would suggest that variability in brain structure may serve as a predisposition to the expression of borderline pathology. Further validating our BPT measure and its investigation in our samples, we expected to replicate links with BPD associated phenotypes (i.e., impulsivity, psychopathology, childhood maltreatment, perceived stress) as a positive control analysis. Finally, we expected that associations between BPT and brain structure would be primarily attributable to shared genetic variation in our family-based HCP dataset (28), and that such differences may account for links between BPT and behavioral correlates, or arise as a consequence of the expression of related traits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data were drawn from two independent samples: the discovery Duke Neurogenetics Study (DNS; n=1,299), and the Human Connectome Project (HCP; n=1,099), which served as a replication sample.

Participants

Duke Neurogenetics Study (DNS):

The DNS (N=1,334) assessed a wide range of behavioral, experiential, and biological phenotypes among young-adult (18–22 year-old) college students. Our final analytic sample consisted of n=1,299 participants (Table 1; age=19.67±1.25; 555 males; 264 with a DSM-IV Axis I disorder; Supplemental Table 1). Additional information regarding sample recruitment, consent, inclusion, and exclusion criteria are provided in the Supplement.

Table 1.

Comparison of discovery (DNS) and replication (HCP) samples

| DNS (N=1,299) | HCP (N=1,099) | t/χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFI-BPD (BPT) | 1.71 (0.40) | 1.42 (0.39) | 18.21 | <2.2×10−16 |

| Age | 19.70 (1.25) | 28.79 (3.69) | −77.97 | <2.2×10−16 |

| Female* | N=744 (57.27%) | N=596 (54.23%) | 2.12 | 0.145 |

| Caucasian* | N=579 (44.57%) | N=758 (68.97%) | 142.68 | <2.2×10−16 |

| African/African American* | N=146 (11.24%) | N=160 (14.56%) | 5.60 | 0.018 |

| Asian/Asian American* | N=352 (27.1%) | N=62 (5.64%) | 190.38 | <2.2×10−16 |

| Hispanic* | N=83 (6.39%) | N=94 (8.55%) | 3.77 | 0.052 |

| Multi-racial/Native American/Other* | N=139 (10.7%) | N=25 (2.27%) | 65.02 | 7.42×10−16 |

| Segmented Brain Volume (cm3) | 1194.76 (114.07) | 1180.60 (123.1) | 2.90 | 0.004 |

Analysis was run as a chi-squared test, all others were run as t-tests. Mean and standard deviation, or counts, are presented. DNS = Duke Neurogenetics Study; HCP = Human Connectome Project.

Human Connectome Project (HCP):

The HCP (N=1,206) examines individual differences in brain circuits and their relation to behavior and genetic background among adult (ages 22–35) participants recruited from the community in a family-based (3–4 siblings per family, most including a twin pair) design (29). We had a final analytic sample of n=1,099 (Table 1; age=28.79±3.69; 503 males). Additional information regarding sample recruitment, consent, inclusion, and exclusion criteria are provided in the Supplement.

Measures

Five Factor Inventory - Borderline Personality Disorder (FFI-BPD) Composite

The FFI-BPD is a composite representing BPD traits (BPT) generated using 24 NEO-FFI items (Supplemental Table 6) (24). These items reflect 14 personality facets, drawn from all 5 major personality factors, that expert consensus and meta-analysis agree are associated with BPD. This composite correlates highly with explicit BPD measures across seven large independent community and adult outpatient samples, including the Personality Assessment Inventory-Borderline Scale (PAI-BOR) (rs=0.6–0.72), the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) BPD subscale (rs=0.63–0.66), the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV) BPD subscale (rs=0.35–0.42), and the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire–Revised (PDQR) BPD subscale (r=0.51) (24, 26). The FFI-BPD was drawn from the 240-item NEO Personality Inventory-Revised in the DNS (α=0.78; M=1.72; SD=0.41; skewness=0.26; range: 0.58–3.29) and the 60-item NEO Five-Factor Inventory (25) in the HCP (α=0.79; M=1.40; SD=0.39; skewness=0.30; range: 0.33–3.33). Supplemental Figure 1 shows FFI-BPD distributions in both samples. The mean and distribution of data in the DNS college and HCP general adult community samples were highly comparable to FFI-BPD scores seen in other college (i.e., Samples 1: M=1.76; SD=0.44; and 2: M=1.83; SD=0.43) and general population adult samples (i.e., Samples 3: M=1.52; SD=0.43; and 4: M=1.35; SD=0.37; (24). To better align our results with prior work in clinical samples, we also computed groups of individuals endorsing relatively High (i.e., top decile, FFI-BPD ≥ 2.13; total n=276 [n=233 from DNS]) and Low (i.e., bottom decile, FFI-BPD ≤ 1.04; total n=276 [n=61 from DNS]) levels of FFI-BPD traits across both samples for secondary post hoc analyses (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Table 3). Decile groups were selected so that the High group would have FFI-BPD scores comparable to those observed in outpatient clinical samples (24) (means of 1.91 and 2.29) while still retaining a large enough sample size to sufficiently power neuroimaging analyses.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Acquisition and Processing of Structural Data

Acquisition parameters and processing of brain structural data for each study are detailed in the Supplement.

Behavioral Correlates of BPD

Alcohol Use Disorder and Other Forms of Psychopathology:

The presence of a DSM-IV alcohol use disorder (i.e., abuse or dependence: DNS n=142; HCP n=230) was assessed in the DNS (past 12 month: abuse n = 73, dependence n = 69) and HCP (lifetime: abuse n=168, dependence n=62) using the electronic Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (e-MINI) and Semi-Structured Assessment For the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA), respectively (39, 40). Other DSM-IV Axis I psychopathology and characteristics were also assessed using these same interviews (Supplemental Table 2)

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors:

The e-MINI suicidality module (40), was used to quantify the presence of suicidal ideation/behavior in the DNS (i.e., ≥1; n=46, see Supplement). Lifetime suicidal ideation (n=103) was assessed in the HCP using a single item within the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA) (39). Across studies, these variables were queried outside of the depression module.

Impulsivity:

DNS participants completed the 30-item self-report Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS (41). HCP participants completed the Achenbach Adult Self-Report (ASR) for Ages 18–59 (42). The attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) score from the ASR was used as a measure of impulsivity.

Perceived stress:

Participants in both samples completed the 10-item version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (43), which instructs participants to appraise how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and stressful their daily life was in the preceding week.

Childhood trauma:

Participants in the DNS completed the 28-item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)(44), which asks participants to retrospectively report on the occurrence and frequency of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse as well as emotional and physical neglect before the age of 17. The instrument’s five subscales, each representing one type of abuse or neglect, have convergent validity with a clinician-rated interviews of childhood abuse (45). The HCP did not include a measure of early-life stress.

Analyses

Positive Control Analyses: Behavioral and Self-report

Positive control analyses tested whether BPT are associated with BPD-related behavior, perception, and experience. Analyses were conducted in an identical fashion to those described for brain structure measures with the exception that BV and scanner were not included as covariates. Self-report questionnaire data were winsorized to maintain variability while limiting the influence of extreme outliers (DNS: FFI-BPD=2, BIS=6, PSS=4, CTQ=23; HCP: FFI-BPD=3, ASR-ADHD=8, PSS=3). Analyses tested associations with both continuous FFI-BPD scores, and the difference between Low and High FFI-BPD score participants.

Primary Analyses: Brain Structure

Primary analyses tested whether BPT are associated with regional estimates of cortical thickness and surface area, and subcortical volume. These analyses were conducted in R (3.1.2) (R Core Team, 2014), as linear regressions (DNS) and mixed-effect models (HCP) (46), which nested data by family as a random effect. All variables were standardized (Z-scored) prior to analyses. Covariates included sex, age, segmented brain volume (BV), and self-reported race/ethnicity (i.e., not-white/white, not-black/black, not Hispanic/Hispanic) as covariates. DNS analyses controlled for scanner. Further, HCP analyses included genomically verified twin status (dizygotic/not, monozygotic/not) and sibling status (half-sibling/not), and DNS analyses included Asian/not Asian as additional covariates in all analyses due to the composition of these samples.

Analyses first focused on corticolimbic regions that have been associated with BPD – the left and right medial prefrontal cortex (thickness and surface area of the medial orbitofrontal cortex, and rostral and caudal anterior cingulate cortex), and left and right hippocampus and amygdala (volume). Discovery analyses were conducted using the DNS (n=16 total tests), with replication analyses in the HCP (16 total tests), and were FDR-corrected for multiple comparisons within each study. Subsequently, analyses examined associations of BPT with structure across every regional summary measure in the DNS (n=152 total tests), with replication in the HCP (n=152 total tests) with FDR-correction within each study.

To better align our analyses with prior work in clinical samples, post-hoc analyses compared participants with scores in the top and bottom deciles (total n=552; see Participants). Finally, as all prior analyses were null (see Results) additional unplanned post-hoc analyses examined whether the presence of 1 or more borderline personality disorder symptoms (binary, n = 118 have at least one symptom) was associated with brain structure in the DNS (no measure of BPD symptoms was collected in the HCP). As we found no associations between BPT and brain structure (see Results), we did not test our hypotheses that shared genetic variation would account for observed associations and links between BPT and behavioral correlates.

Meta-analyses

As no region survived FDR-correction in either sample (see Results), association results from the two samples were meta-analyzed in an exploratory analysis. Standardized effect-sizes from regression analyses (β-slope and corresponding standard error) from both samples were entered into meta-analyses conducted with the ‘metafor’ package (47). As in prior analyses, results were FDR-corrected for multiple comparisons (n=152 total tests).

Sensitivity Analysis

As sample sizes were determined by data sources, sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine the minimum effect size meta-analyses of the DNS and HCP could be expected to detect. Power was set at 99% and 80%, and α = 5×10−4 (i.e. controlling for family-wise error), using the ‘pwr’ R package (48). Results indicated that analyses of BPT and brain structure were well-powered to detect small effect-sizes, as low as r=0.12 with 99%, and r=0.09 with 80% power. Considering each sample independently, analyses were powered at 80% to detect effects as small as r=0.12 Importantly, these effect-sizes are smaller or comparable to reported associations between personality traits and brain structure (49), and between BPD and brain structure (12, 14).

Results

Sample Comparisons and Associations between BPT and Demographic Factors

Comparisons between samples are reported in Table 1. The average age of participants differed between the DNS and HCP, as the DNS recruited exclusively young adults. Consistent with this age difference, BPT scores and BV were higher in the DNS (50, 51). Samples also differed in the distribution of self-reported ethnicity; more participants in the DNS reported being from minority backgrounds. Samples did not differ by self-reported sex. BPT was associated with age and ethnicity in both samples and differed according to gender in the HCP (Supplemental Table 1).

Positive Control Results: BPT and BPD-related Behavioral Phenotypes

Positive-control analyses in both samples revealed consistent evidence that BPT are associated with increased self-reported impulsivity (BIS/ASR-ADHD), perceived stress, childhood maltreatment, suicidal thoughts and behavior, and psychopathology including alcohol use disorder (DSM-IV abuse or dependence; Table 2). These results survived FDR-correction for multiple comparison, associations are in the same direction in both samples, and post-hoc analyses found that associations remained largely unchanged when participants with an Axis-I diagnosis were excluded (Supplemental Table 5). Notably, consistent with evidence that the FFI-BPD composite aligns with explicit measures of borderline personality pathology (24), BPT were predictive of ≥1 borderline personality symptom (OR=2.3, p=1.69×10−15) (Table 2) and a variety of psychiatric disorders in both samples (ORs: 1.1 – 1.25, ps: 2×10−3 - 3×10−16) (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2.

Borderline traits are robustly associated with positive control measures

| β (SE) | t/z | p-value | β (SE) | t/z | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Abuse or Dependence* | 0.43 (0.09) | 4.59 | 4.35×10−6 | 0.32 (0.08) | 4.12 | 3.85 ×10−5 |

| Suicidal ideation or behavior* | 0.73 (0.16) | 4.70 | 2.60 ×10−6 | 0.6 (0.1) | 6.16 | 7.48 ×10−10 |

| Impulsivity (BIS or ASR) | 0.54 (0.02) | 22.90 | 1.13 ×10−97 | 0.61 (0.02) | 25.29 | 2.10 ×10−111 |

| Perceived stress | 0.60 (0.02) | 27.55 | 7.82×10−132 | 0.59 (0.02) | 23.77 | 6.8×10−101 |

| Childhood trauma | 0.34 (0.03) | 12.43 | 1.39×10−38 | - | - | - |

| Any borderline personality disorder symptom* | 0.86 (0.11) | 7.96 | 1.69×10−15 | - | - | - |

Associations of BPT (FFI-BPD scores) (DV) with positive-control measures (IV). BIS = Barrat Impulsivity Scale, measured in the DNS. ASR = Achenbach Self Report impulsivity subscale, measured in the HCP.

Analysis was run as a logistic regression, presented effect sizes and standard errors have not been transformed. All effect sizes are standardized, all associations survive bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Analyses included same covariates as neuroimaging analyses. A measure of borderline personality disorder symptoms or diagnosis, nor a measure of childhood trauma, was not present in the HCP. DNS = Duke Neurogenetics Study; HCP = Human Connectome Project.

BPT and Brain Structure

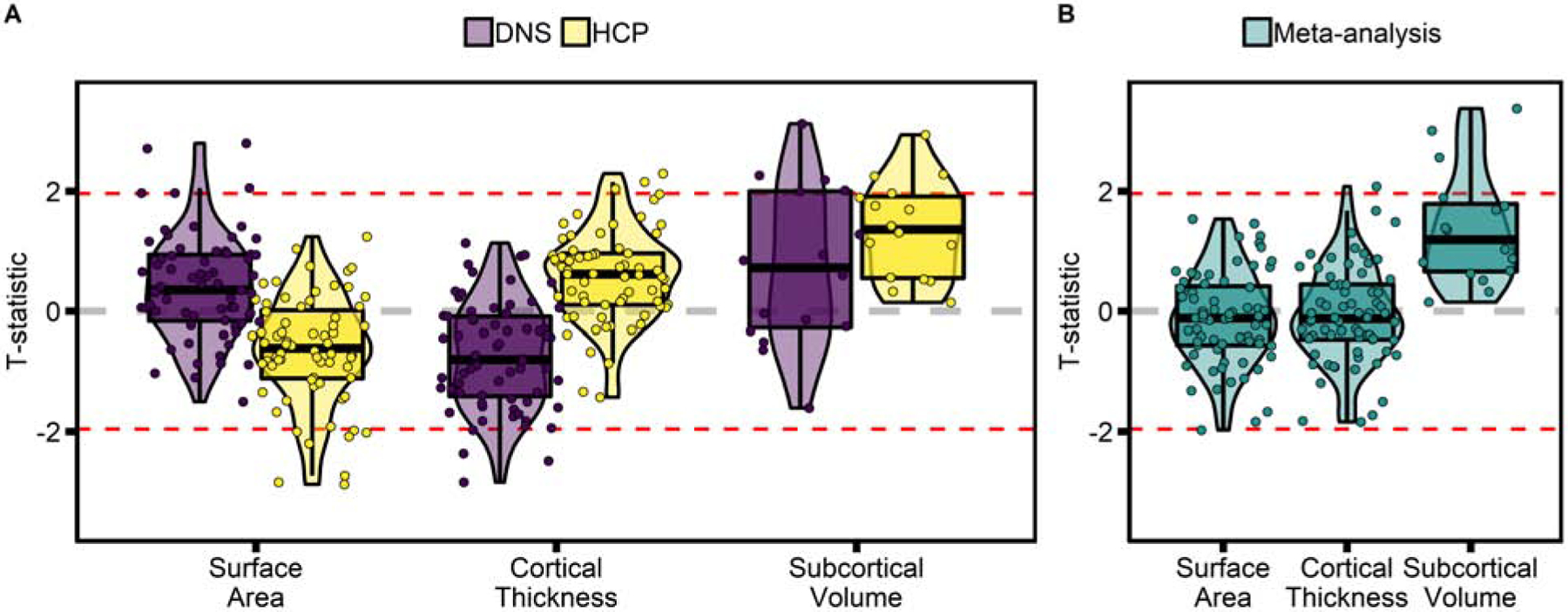

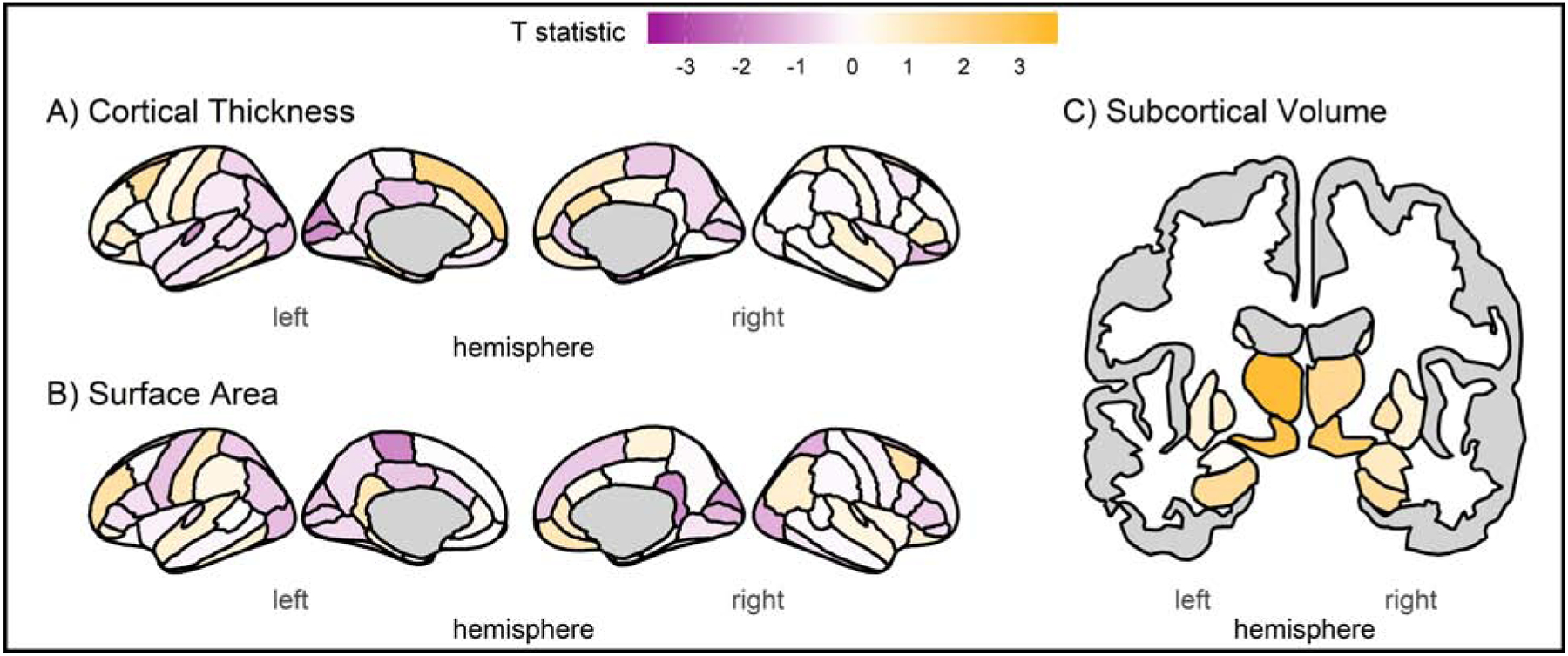

BPT were not significantly associated with individual differences in the 16 a priori brain metrics in either the DNS or HCP, with no nominally significant associations (p<0.05 uncorrected) in either sample (Supplemental Data). Across the 152 extracted summary measures, no association survived FDR-correction for multiple comparisons in either sample (Figure 1A, Supplemental Figures 2&3, Supplemental Data). There were nominally significant associations in both samples (14 in the DNS and 15 in the HCP; Supplemental Data); however only 3 (i.e., left parsorbitalis thickness, left superior frontal gyrus surface area, and left ventral diencephalon volume) were associated with BPT across both samples, and only one of these, volume of the left ventral diencephalon, was directionally consistent (DNS β=0.04, p=0.046; HCP β=0.05, p=0.023; Supplemental Table). Meta-analyses of results from the two samples (Figures 1B & 2, Supplemental Data) revealed no FDR-corrected significant associations and 5 nominally significant associations: 1) left thalamus (β=0.047, p=7×10−4), 2) left ventral diencephalon (β=0.043, p=0.003), 3) right ventral diencephalon (β=0.035, p=0.01), 4) left superior frontal thickness (β=0.042, p=0.037), 5) left paracentral surface area (β=−0.033, p=0.048). None of the 16 a priori imaging-derived phenotypes reached nominal significance in the meta-analysis – the top two (p<0.1 uncorrected) were positive associations of BPT with increased volume of the left and right hippocampus (Supplemental Data). Results comparing participants with High and Low BPT did not differ substantially, and no association surviving FDR-correction was identified in any analysis (Supplemental Data).

Figure 1: Associations of borderline personality traits with brain structure.

T-statistics of the association of BPT (FFI-BPD scores) with summary measures of brain structure in (A) the DNS and HCP samples and (B) in the meta-analysis of the two samples. Associations are displayed by measurement type (cortical surface area, cortical thickness, and subcortical volume), highlighting that findings were most consistent in the subcortex. Dotted red lines are at T=±1.96, corresponding to p=0.05 uncorrected. No association survives correction for multiple comparison. DNS = Duke Neurogenetics Study; HCP = Human Connectome Project.

Figure 2. Regional meta-analysis of borderline personality traits and brain structure.

Results from the meta-analysis of results from the DNS and HCP, including (A) cortical thickness, (B) cortical surface area, and (C) subcortical volume. Colors correspond to the t-statistic of the association of BPT (FFI-BPD scores) with regional summary measures – no region survives FDR-correction for multiple comparisons.

Unplanned post-hoc analyses found that the presence of at least one BPD symptom (n=118) was associated with decreased thickness of the right precentral (β=−0.098, SE=0.028, t=−3.535, p=4.2×10−4, pFDR=0.04) and paracentral gyri (β=−0.095, SE=0.028, t=−3.469, p=5.4×10−4, pFDR=0.04; Supplemental Data), in the DNS even after FDR correction for 152 tests. However, these associations were not robust when correcting for prior analyses of BPT and brain structure (total tests n= 304, both pFDR=0.082). Associations between BPT and these regions were similarly negative in the DNS, while associations were positive in the HCP. BPD symptoms were not associated with a priori corticolimbic structures (all p-uncorrected > 0.05); the strongest, non-significant correlation was with increased bilateral amygdala volume (p<0.1, Supplemental Data).

Discussion

Using two large independent and unselected neuroimaging samples that were well-powered to detect small effects (i.e., rs=0.09–0.12, 80%–99% power), we examined whether BPD-related personality traits (BPT) were associated with individual differences in brain structure and BPD-related behavioral constructs. Two notable findings emerged. First, contrary to our hypotheses, we found no evidence that BPT are associated with variability in brain structure in unselected samples. Second, we observed consistent associations between BPT and BPD-related phenotypes (i.e., impulsivity, problematic alcohol use, suicidal thoughts and behaviors, perceived stress, childhood maltreatment) that align with reports of increased rates of alcohol use disorder (1), suicidality (52), impulsivity (53, 54), trauma (55), and perceived stress (56) among BPD patients. These later results provide evidence for the validity of the FFI-BPD measure as an assessment of borderline pathology. As such, the null results for structure raise the possibility that prior positive reports in small clinical patient samples may be attributable to differences in sample composition associated with clinical BPD (e.g., severity, comorbidity, environmental experience, medication) rather than borderline personality traits, or may reflect false positive associations.

Brain structure

Structural imaging studies of BPD patient samples have linked the disorder to reduced gray matter volume in the hippocampus and amygdala, as well as several cortical regions, with several meta-analyses suggesting robust associations with brain structure (8, 10–14). Given the prominent role that corticolimbic structures play in emotion and stress regulation (57), the structural differences observed in clinical BPD samples have been conceptualized as reflecting a potential preexisting vulnerability to emotion and stress dysregulation (12, 22, 58). In contrast to these positive studies in small patient samples, we observed no evidence that BPD traits are associated with structural variation across two large unselected neuroimaging samples.

Post-hoc analyses found some evidence for associations between the presence of at least one BPD symptom and thickness of somatomotor regions, which has been observed in prior reports (15). However, these findings do not survive multiple-comparison correction accounting for prior analyses with BPT, and associations of BPT with these structures are directionally opposite in the two samples, suggesting that this association may be a false-positive or developmentally constrained. Indeed, BPD is highly comorbid with ADHD, an association which we replicate (59). Work in large clinical samples has found that structural associations with ADHD are largely constrained to childhood (60, 61). If this is also the case with BPD – even though prior reports have exclusively used adult samples – we would not expect to detect such effects in the current study.

Many potential explanations may be invoked to account for the discrepancy between our null results and positive reports in clinical patient samples. Unlike BPD patient samples, our studies were unselected for BPD. It is possible that BPD associations with brain structure may only be observed in clinical and/or extreme presentations of BPD, or might be associated with BPD-associated severe comorbidities (e.g., psychopathology and physical health conditions) or experiences (e.g., childhood adversity, medication). Consistent with this speculation, one study reported reduced hippocampal volume only among patients with severe presentations of BPD (i.e., ≥7 BPD criteria, n=18; (62)). We must also note that differences in subcortical volume, including the hippocampus, are not unique to BPD, but have also been reported in depression (63), schizophrenia (64), bipolar disorder (65), ADHD (60), and OCD (66). Thus, some of the previously reported associations with BPD may not reflect borderline pathology, but severe general psychopathological distress. If only the most severe cases underlie previously reported associations with BPD, our sample would not have sufficient extreme scores to detect this, and one would not expect to see linear negative correlations between brain structure and BPT – a central assumption of our statistical models. However, our BPT extreme groups approach, which yielded borderline trait scores comparable to those observed in outpatient clinical samples with a formal BPD diagnosis (24), revealed null associations.

Further, we observed expected correlations with phenotypes that were not collinear in item composition with our FFI-BPD composite (i.e., suicidal thoughts and behaviors, alcohol use disorder, childhood maltreatment), as well as with the presence of at least one borderline personality disorder symptom (OR: 2.36; Table 2), and replicated prior reports of large correlations between BPT and ADHD symptoms (59). While BPT were associated with Axis-I disorder diagnoses in both samples, consistent with well-established broad comorbidities of BPD (67), correlations between positive control measures and BPT remained even when participants with a diagnosis were excluded from analyses (Supplemental Table 5). While we cannot rule out that our positive control findings are driven by the presence general psychopathology, these correlations are consistent with patterns expected of a measure of borderline personality traits.

Thus, these results suggest that our phenotype was sufficiently severe and variable to identify these expected patterns of association, and that previously observed links between BPD and brain structure might not be attributable to BPD-related personality. It remains possible that our samples had other protective factors (e.g., those associated with attending college in the DNS, those associated with participating in a community-based research study in HCP) that in the context of high BPT prevented clinical levels of expression and related neural correlates.

The present null findings also stand in contrast to a large body of work documenting correlations between brain structure and broad personality traits (i.e. the big five) (68). However, few replicable associations have emerged from these efforts (69). Recently, data from the Human Connectome Project, which was used as a replication sample in this report, has been repeatedly examined for associations between brain structure and broad personality traits (49, 70–74). While there is evidence for associations within this sample that are robust to analytic method (49, 71), few findings have so far been independently replicated (69, 75–78).

We must also consider more mundane explanations which may also account for our discrepancy with prior literature, including the possibility of false positive results. Small samples and publication bias are more likely to generate false positive results, which may have led meta-analyses to overestimate the association between BPD and brain structure (79, 80). Indeed, it is possible that false positive associations may be widespread in clinical psychiatric neuroscience where studies of difficult to recruit patient samples are often hindered by their limited size and high heterogeneity (81). Consistent with this notion, a large mega-analysis of depression (>17,000 cases) (63), found that the effect size of the association between depression and reduced hippocampal volume is less than half of what was reported in one of the first meta-analyses, which included 351 patients (82). Similarly, while recent studies examining structural correlates of broad personality traits have been well-powered by current standards, the scarcity of convergent findings (69, 75–78) suggests that associations are smaller than anticipated.

Despite including a replication component, the present report may reflect a false negative finding. While our sensitivity analysis indicated that we were well-powered to detect small correlations (r>0.12, 99% power, α=5×10−4), it is plausible that correlations between borderline personality traits and brain structure exist, but that they are smaller than what we could reliably detect. Thus, at minimum, the present report places an upper-bound on the effect-size that future investigations should plan to detect. For example, if there are correlations at r=0.08 between BPT and brain structure, more than double the number participants (N=5,300) would be needed to attain comparable (99%) power. The precision of mapping correlations between BPT and brain structure can also be improved in future work, by using more recently developed algorithms for segmenting subcortical structures (83).

Conclusions

Results of the current study suggest that borderline personality traits are associated with related behavioral constructs, but not variability in regional brain structure. A major strength of our work was the consistency of results across two large, independent datasets. Notably, these findings should be interpreted in the context of study limitations, including our unselected samples and cross-sectional designs. It remains possible that unique features or correlates of a formal BPD diagnosis, including extreme severity (62) may be associated with structural variability as opposed to borderline personality traits. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that prior reports in small samples linking BPD to brain differences may have detected associations with correlates of its clinical presentation, overestimated effects, or represent false positive associations. Clearly, additional research in large samples enriched for BPD are needed. If extreme severity, not present in our sample, is driving these effects, it will be important to model non-linear effects in addition to continuous symptom counts. Finally, this work provides strong evidence that future research into the structural neural correlates of borderline personality traits should be powered to detect very small effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Data for this study were provided by the Human Connectome Project, WU-Minn Consortium (principal investigators: David Van Essen, PhD, and Kamil Ugurbil, PhD; grant 1U54MH091657) funded by the 16 National Institutes of Health institutes and centers that support the National Institutes of Health Blueprint for Neuroscience Research, as well as by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience at Washington University. The Duke Neurogenetics Study is supported by Duke University and NIDA (DA033369). DAAB was supported by NIH (T32-GM008151) and NSF (DGE-1143954). LF was supported by NIAAA (AA023693). AA was supported by NIDA (5K02DA32573). ARH receives additional support from NIDA (DA031579) and NIA (AG049789). RB was supported by the Klingenstein Third Generation Research and NIH (R01-AG045231, R01-HD083614, R01-AG052564). Portions of these data were presented in an oral talk at the 2016 Society of Biological Psychiatry meeting in Atlanta, Georgia. This manuscript draft was posted as a preprint prior to submission on the PsyArxiv server (doi: 10.31234/osf.io/ku8b5).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures

All authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, et al. (2008): Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 69: 533–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellison WD, Rosenstein LK, Morgan TA, Zimmerman M (2018): Community and Clinical Epidemiology of Borderline Personality Disorder. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 41: 561–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leichsenring F, Leibing E, Kruse J, New AS, Leweke F (2011): Borderline personality disorder. Lancet (London, England). 377: 74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, Hale N (2004): Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: Prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. Journal of Personality Disorders. 18: 226–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, Sanislow CA, Dyck IR, McGlashan TH, et al. (2001): Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 158: 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leichsenring F, Leibing E, Kruse J, New AS, Leweke F (2011): Borderline personality disorder. Lancet. 377: 74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp C, Wright AGC, Fowler JC, Frueh BC, Allen JG, Oldham J, Clark LA (2015): The structure of personality pathology: Both general (‘g’) and specific (‘s’) factors? Journal of abnormal psychology. 124: 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu H, Meng Y, Li X, Zhang C, Liang S, Li M, et al. (2019): Common and distinct patterns of grey matter alterations in borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder: voxel-based meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 215: 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmahl C, Bremner JD (2006): Neuroimaging in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 40: 419–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimmel CL, Alhassoon OM, Wollman SC, Stern MJ, Perez-Figueroa A, Hall MG, et al. (2016): Age-related parieto-occipital and other gray matter changes in borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis of cortical and subcortical structures. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 251: 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang X, Hu L, Zeng J, Tan Y, Cheng B (2016): Default mode network and frontolimbic gray matter abnormalities in patients with borderline personality disorder: A voxel-based meta-analysis. Scientific Reports. 6: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunes PM, Wenzel A, Borges KT, Porto CR, Caminha RM, de Oliveira IR (2009): Volumes of the hippocampus and amygdala in patients with borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Journal of Personality Disorders. 23: 333–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigues E, Wenzel A, Ribeiro MP, Quarantini LC, Miranda-Scippa A, de Sena EP, De Oliveira IR (2011): Hippocampal volume in borderline personality disorder with and without comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. European Psychiatry. 26: 452–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruocco AC, Amirthavasagam S, Zakzanis KK (2012): Amygdala and hippocampal volume reductions as candidate endophenotypes for borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Psychiatry Research - Neuroimaging. 201: 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aguilar-Ortiz S, Salgado-Pineda P, Marco-Pallarés J, Pascual JC, Vega D, Soler J, et al. (2018): Abnormalities in gray matter volume in patients with borderline personality disorder and their relation to lifetime depression: A VBM study. PLoS ONE. 13: 179–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Depping MS, Wolf ND, Vasic N, Sambataro F, Thomann PA, Christian Wolf R (2015): Specificity of abnormal brain volume in major depressive disorder: A comparison with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 174: 650–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Euston DR, Gruber AJ, McNaughton BL (2012): The Role of Medial Prefrontal Cortex in Memory and Decision Making. Neuron. 76: 1057–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phelps EA (2004): Human emotion and memory: Interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 14: 198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR, Lee GP (1999): Different Contributions of the Human Amygdala and Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex to Decision-Making. The Journal of Neuroscience. 19: 5473–5481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaBar KS, Cabeza R (2006): Cognitive neuroscience of emotional memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 7: 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Etkin A, Egner T, Kalisch R (2011): Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 15: 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunderson JG, Herpertz SC, Skodol AE, Torgersen S, Zanarini MC (2018): Borderline personality disorder. Nature Reviews. 4: 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lynam DR, Widiger TA (2001): Using the five-factor model to represent the dsm-iv personality disorders: An expert consensus approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Few LR, Miller JD, Grant JD, Maples J, Trull TJ, Elliot C, et al. (2015): Trait-Based Assessment of Borderline Personality Disorder Using the NEO Five-Factor Inventory: Phenotypic and Genetic Support. Psychological Assessment. 28: 39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa PT, McCrae RR (1992): Professional manual: revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI). Odessa FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; (Vol. 3). doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.4.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavner JA, Lamkin J, Miller JD (2015): Borderline personality disorder symptoms and newlyweds’ observed communication, partner characteristics, and longitudinal marital outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 124: 975–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conway CC, Hopwood CJ, Morey LC, Skodol AE (2018): Borderline personality disorder is equally trait-like and state-like over ten years in adult psychiatric patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 127: 590–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baranger D, Demers C, Elsayed N, Agrawal A, Barch D, Williamson D, et al. (2019): Convergent Evidence for Predispositonal Effects of Brain Volume on Alcohol Consumption. Biological Psychiatry. In press. doi: 10.1101/299149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith SM, Nichols TE, Vidaurre D, Winkler AM, J Behrens TE, Glasser MF, et al. (2015): A positive-negative mode of population covariation links brain connectivity, demographics and behavior. Nature Neuroscience. 18: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein A, Andersson J, Ardekani BA, Ashburner J, Avants B, Chiang MC, et al. (2009): Evaluation of 14 nonlinear deformation algorithms applied to human brain MRI registration. NeuroImage. 46: 786–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI (1999): Cortical surface-based analysis: I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. NeuroImage. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM (1999): Cortical surface-based analysis: II. Inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. NeuroImage. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein A, Tourville J (2012): 101 Labeled Brain Images and a Consistent Human Cortical Labeling Protocol. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 6: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischl B, Dale AM (2000): Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200033797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. (2006): An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. NeuroImage. 31: 968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, et al. (2002): Whole Brain Segmentation Automated Labeling of Neuroanatomical Structures Structures in the Human Brain. Neuron. 33: 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glasser MF, Sotiropoulos SN, Wilson JA, Coalson TS, Fischl B, Andersson JL, et al. (2013): The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage. 80: 105–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Essen DC, Ugurbil K, Auerbach E, Barch D, Behrens TEJ, Bucholz R, et al. (2012): The Human Connectome Project: A data acquisition perspective. NeuroImage. 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, et al. (1994): A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 55: 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. (1998): The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The Development and Validation of a Structured Diagnostic Psychiatric Interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 59: 22–33. quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES (1995): Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of clinical psychology. 51: 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Achenbach T (2009): Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA). University of Vermont Research Center of Children Youth & Families. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983): A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of health and social behavior. 24: 385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, et al. (2003): Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect. 27: 169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scher CD, Stein MB, Asmundson GJG, Mccreary DR, Forde DR (2001): The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in a community sample: Psychometric properties and normative data. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 14: 843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC, Maechler Martin, Walker SC (2015): Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software. 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Viechtbauer W (2010): Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. Journal of Statistical Software. 36: 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Champely S (2015): pwr: Basic Functions for Power Analysis.

- 49.Owens MM, Hyatt CS, Gray JC, Carter NT, MacKillop J, Miller JD, Sweet LH (2019): Cortical morphometry of the five-factor model of personality: findings from the Human Connectome Project full sample. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 381–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Biskin RS (2015): The lifetime course of borderline personality disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 60: 303–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mills KL, Goddings A-L, Herting MM, Meuwese R, Blakemore S-J, Crone EA, et al. (2016): Structural brain development between childhood and adulthood: Convergence across four longitudinal samples. NeuroImage. 141: 273–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oldham JM (2013): Borderline Personality Disorder and Suicidality. FOCUS: The Journal of Lifelong Learning in Psychiatry. 11: 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Svaldi J, Philipsen A, Matthies S (2012): Risky decision-making in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research. 197: 112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lawrence KA, Allen JS, Chanen AM (2010): Impulsivity in borderline personality disorder: Reward-based decision-making and its relationship to emotional distress. Journal of Personality Disorders. 24: 785–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Porter C, Palmier-Claus J, Branitsky A, Mansell W, Warwick H, Varese F (2019): Childhood adversity and borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. doi: 10.1111/acps.13118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wingenfeld K, Schaffrath C, Rullkoetter N, Mensebach C, Schlosser N, Beblo T, et al. (2011): Associations of childhood trauma, trauma in adulthood and previous-year stress with psychopathology in patients with major depression and borderline personality disorder. Child abuse & neglect. 35: 647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schulze L, Schmahl C, Niedtfeld I (2016): Neural Correlates of Disturbed Emotion Processing in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Multimodal Meta-Analysis. Biological Psychiatry. 79: 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheavens JS, Strunk DR, Chriki L (2012): A Comparison of Three Theoretically Important Constructs: What Accounts For Symptoms of Borderline Personality Disorder? Journal of Clinical Psychology. 68: 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Distel MA, Carlier A, Middeldorp CM, Derom CA, Lubke GH, Boomsma DI (2011): Borderline personality traits and adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms: A genetic analysis of comorbidity. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 156: 817–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoogman M, Bralten J, Hibar DP, Mennes M, Zwiers MP, Schweren LSJ, et al. (2017): Subcortical brain volume differences in participants with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: a cross-sectional mega-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 4: 310–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoogman M, Muetzel R, Guimaraes JP, Shumskaya E, Mennes M, Zwiers MP, et al. (2019): Brain imaging of the cortex in ADHD: A coordinated analysis of large-scale clinical and population-based samples. American Journal of Psychiatry. 176: 531–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Labudda K, Kreisel S, Beblo T, Mertens M, Kurlandchikov O, Bien CG, et al. (2013): Mesiotemporal volume loss associated with disorder severity: A VBM study in borderline personality disorder. PLoS ONE. 8: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmaal L, Veltman DJ, van Erp TGM, Sämann PG, Frodl T, Jahanshad N, et al. (2015): Subcortical brain alterations in major depressive disorder: findings from the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder working group. Molecular Psychiatry. 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Erp TGM, Hibar DP, Rasmussen JM, Glahn DC, Pearlson GD, Andreassen OA, et al. (2016): Subcortical brain volume abnormalities in 2028 individuals with schizophrenia and 2540 healthy controls via the ENIGMA consortium. Molecular Psychiatry. 21: 547–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hibar DP, Westlye LT, Van Erp TGM, Rasmussen J, Leonardo CD, Faskowitz J, et al. (2016): Subcortical volumetric abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 21: 1710–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boedhoe PSW, Schmaal L, Abe Y, Ameis SH, Arnold PD, Batistuzzo MC, et al. (2017): Distinct subcortical volume alterations in pediatric and adult OCD: A worldwide meta- and mega-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 174: 60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, Reynolds V (1998): Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 155: 1733–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petrosini L, Cutuli D, Picerni E, Laricchiuta D (2018): Personality Is Reflected in Brain Morphometry In: Spalletta G, Piras F, Gili T, editors. Brain Morphometry Neuromethods. (Vol. 136), New York, NY: Humana Press, pp 451–468. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fair B (2018): The Brain Correlates of Personality and Sex Differences. University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hyatt CS, Owens MM, Gray JC, Carter NT, MacKillop J, Sweet LH, Miller JD (2019): Personality traits share overlapping neuroanatomical correlates with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 128: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Valk S, Hoffstaedter F, Camilleri J, Kochunov P, Yeo B, Eickhoff S (2019): Neurogenetic basis of personality. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/645945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Szalkai B, Varga B, Grolmusz V (2018): Mapping Correlations of Psychological and Connectomical Properties of the Dataset of the Human Connectome Project with the Maximum Spanning Tree Method. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Riccelli R, Toschi N, Nigro S, Terracciano A, Passamonti L (2017): Surface-based morphometry reveals the neuroanatomical basis of the five-factor model of personality. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 12: 671–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gray JC, Owens MM, Hyatt CS, Miller JD (2018): No evidence for morphometric associations of the amygdala and hippocampus with the five-factor model personality traits in relatively healthy young adults. PLoS ONE. 13: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lewis GJ, Alexander D, Cox SR, Karama S, Evans AC, Starr JM, et al. (2018): Widespread associations between trait conscientiousness and thickness of brain cortical regions. NeuroImage. 176: 22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Opel N, Amare AT, Redlich R, Repple J, Kaehler C, Grotegerd D, et al. (2018): Cortical surface area alterations shaped by genetic load for neuroticism. Molecular Psychiatry. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Elliott LT, Sharp K, Alfaro-Almagro F, Shi S, Miller KL, Douaud G, et al. (2018): Genome-wide association studies of brain imaging phenotypes in UK Biobank. Nature. 562: 210–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Avinun R, Israel S, Knodt AR, Hariri AR (2019): No evidence for associations between the Big Five personality traits and variability in brain gray or white matter. bioRxiv. 658567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ioannidis JPA (2016): The Mass Production of Redundant, Misleading, and Conflicted Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Milbank Quarterly. 94: 485–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Van Aert RCM, Wicherts JM, Van Assen MALM (2019): Publication bias examined in meta-analyses from psychology and medicine: A meta-meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (Vol. 14). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tackett JL, Brandes CM, King KM, Markon KE (2019): Psychology’s Replication Crisis and Clinical Psychological Science. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 15: 579–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Videbech P, Ravnkilde B (2004): Hippocampal Volume and Depression: A Meta-Analysis of MRI Studies. Am J PsychiatryAm J Psychiatry. 16111: 1957–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Khlif MS, Egorova N, Werden E, Redolfi A, Boccardi M, DeCarli CS, et al. (2019): A comparison of automated segmentation and manual tracing in estimating hippocampal volume in ischemic stroke and healthy control participants. NeuroImage: Clinical. 21. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.