Abstract

Although maternal antibodies protect newborn babies from infection1,2, little is known about how protective antibodies are induced without prior pathogen exposure. Here we show that neonatal mice that lack the capacity to produce IgG are protected from infection with the enteric pathogen enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli by maternal natural IgG antibodies against enterotoxigenic E. coli when antibodies are delivered either across the placenta or through breast milk. By challenging pups that were fostered by either maternal antibody-sufficient or antibody-deficient dams, we found that breast-milk-derived IgG was critical for protection against mucosal disease induced by enterotoxigenic E. coli. IgG also provides protection against systemic infection by E. coli. Pups used the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) to transfer IgG from milk into serum. The maternal commensal microbiota can induce antibodies that recognize antigens expressed by enterotoxigenic E. coli and other Enterobacteriaceae species. Induction of maternal antibodies against a commensal Pantoea species confers protection against enterotoxigenic E. coli in pups. This role of the microbiota in eliciting protective antibodies to a specific neonatal pathogen represents an important host defence mechanism against infection in neonates.

Neonates are highly susceptible to microbial infections, not only because their immature immune system is less capable of generating adaptive immune effectors such as antibodies1,2, but also because they lack a diverse commensal microbiota that can antagonize pathogens independently of host responses3. Neonates acquire maternal antibodies through the placenta and through breast milk; however, in humans, antibodies derived from breast milk are dominated by secretory IgA antibodies, which are thought to exert their protective function on neonatal mucosal surfaces through mechanisms such as toxin or adhesin neutralization and bacterial agglutination4,5. Passive immunity to various pathogenic bacterial and viral infections (such as group B Streptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae and influenza viruses) can be transferred to neonates by maternal antigen-specific IgG antibodies induced by maternal colonization or vaccination6–8.

Although the benefits of maternal antibodies are widely accepted9, few studies have addressed whether maternal natural antibodies (mNabs)—that is, antibodies acquired without known exposure to the pathogen or through immunization—can help neonates to defend against pathogens. Although the commensal microbiota can shape the antibody repertoire10,11, how the diversity in mNabs is induced or how they mediate protection against infectious agents postnatally are unknown. Here we show that mNabs protect neonatal mice against both enteric and systemic infections with enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC). Notably, we found that the induction of mNabs depends on the commensal microbiota in pregnant dams. We show that a single commensal species can induce cross-reactive mNabs that protects against ETEC in pups. In addition to acquisition through the placenta, pups can assimilate IgG mNabs directly from ingested milk into serum by a neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn)-dependent process. Our results provide insights into how the commensal microbiota of pregnant female mice drives antibody-dependent immunity in neonates through breast-feeding and demonstrate that protective IgG antibodies in breast milk act both locally and systemically.

Mouse mNabs protect neonates against ETEC

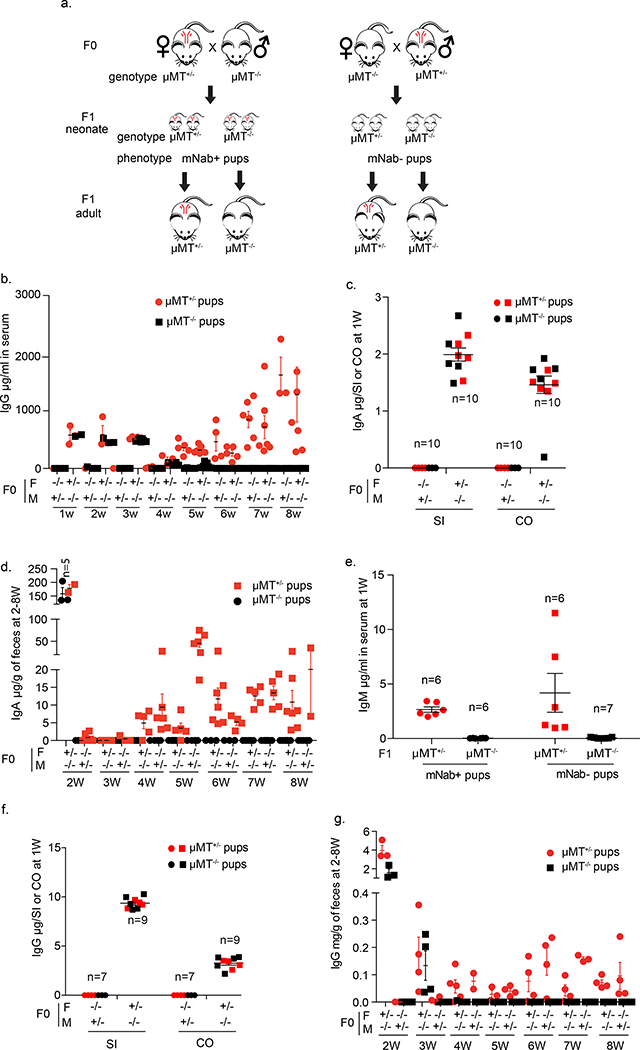

To analyse the developmental dynamics of neonatal antibodies, we used a reciprocal breeding strategy that enabled the tracking of maternal antibody persistence and antibody development dynamics in neonates. Maternal source, persistence and development of neonatal age-related IgG, IgA and IgM are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. For the first 3 weeks, serum and mucosal IgG and IgA levels in pups depend completely on the maternal μMT (also known as Ighm) genotype (μMT−/− mice lack mature B cells). Although IgM is made only in μMT+/− pups, it is not vertically transmitted from dams to pups. Through this breeding strategy, we can produce pups that are either deficient (mNab−) or sufficient (mNab+) in maternal natural IgG and IgA.

Transfer of vaccine-induced, antigen-specific antibodies confers passive protection in models of neonatal infection6,8,12. To test whether mNabs in unimmunized mice protect against an enteric pathogen, we challenged reciprocally bred 6- to 7-day-old pups with ETEC strain 6 (hereafter ETEC 6), a human clinical isolate. ETEC 6 colonizes the small intestine of neonatal mice and typically causes acute and lethal diarrhoeal disease within 20 h of oral gastric challenge. At a sub-lethal dose of ETEC 6 (107 colony-forming units (CFU)), mNab+ pups were more resistant to infection than mNab− pups and displayed a 33-fold reduction in intestinal colonization of ETEC 6 (Fig. 1a). Stratification by genotype showed no survival difference between μMT+/− and μMT−/− pups. At a higher dose (109 CFU), all mNab+ pups were resistant to ETEC 6 challenge, whereas 83% of mNab− pups became moribund or had died within 20 h after challenge (Fig. 1b). The postnatal time of our ETEC challenge is too early for antigen-driven endogenous production of IgA and IgG; thus, the protective effects depend on maternally derived antibodies. We verified that IgG was detected in serum (Fig. 1c) and in gut luminal extracts (Fig. 1d) of only the mNab+ pups. We also challenged reciprocally bred pups intraperitoneally and found that mNab+ pups were more resistant to systemic infection with ETEC than mNab− pups (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Previous studies showed that natural IgM antibodies have broad specificity and provide protection against bacterial and viral infections13–17. However, natural IgM cannot be vertically transmitted from dams to pups (Extended Data Fig. 1e) and therefore is unlikely to play an important part in the protection against ETEC observed in our study.

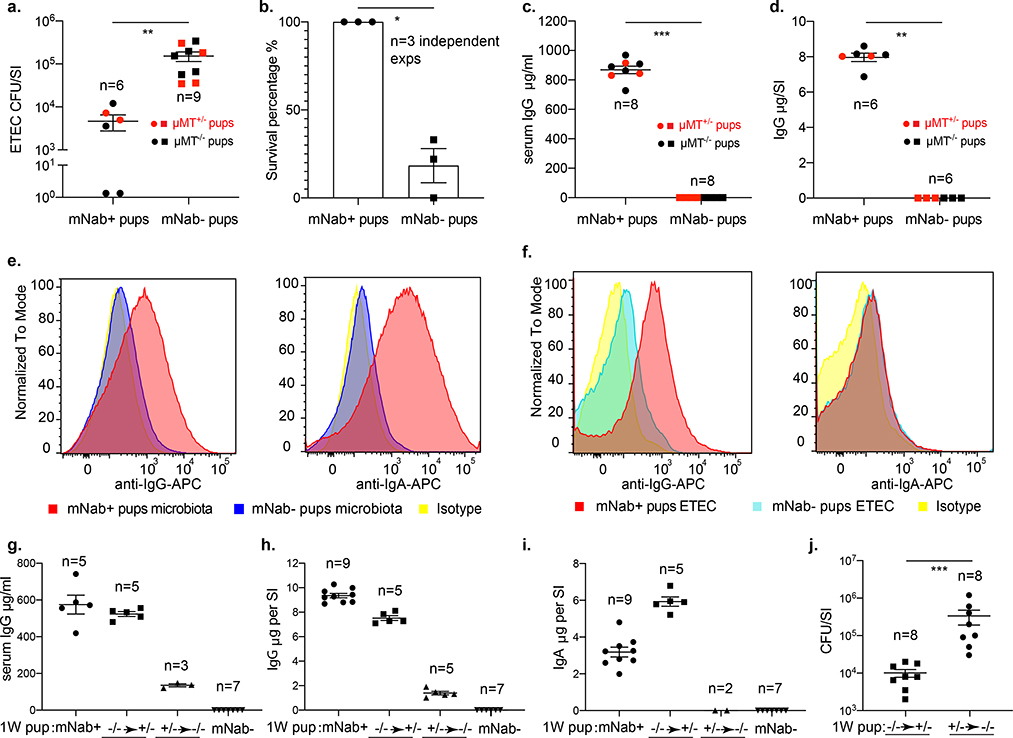

Fig. 1. mNabs protect neonates from an enteric bacterial pathogen.

a, Bacterial burdens of reciprocally bred mNab+ and mNab− pups (6–7 days old) orally challenged with 107 CFU of ETEC 6. Ig. Immunoglobulin; SI, small intestine. **P = 0.0004, two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test. Data are representative of four independent experiments. b, Survival among reciprocally bred pups 20 h after oral–gastric challenge with 109 CFU of ETEC 6. Data are from three independent experiments (first experiment, n = 8 mNab+ mice, n = 5 mNab− mice; second experiment, n = 9 mNab+ mice, n = 9 mNab− mice; third experiment, n = 7 mNab+ mice, n = 6 mNab− mice). *P = 0.0011, two-tailed unpaired t-test. c, Serum IgG levels in ETEC-challenged reciprocally bred pups. ***P = 0.0002, two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test. Data are representative of two independent experiments. d, Small-intestinal mucosal IgG levels in ETEC-challenged reciprocally bred pups. **P = 0.0022, two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test. Data are representative of two independent experiments. SI, small intestine. e, Flow cytometry analysis of natural maternal IgG and IgA coating of commensal bacteria of 1-week-old mNab+ and mNab− pups. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 4–5 mice per group in each experiment). f, Flow cytometry analysis of natural maternal IgG and IgA coating of ETEC–GFP bacteria in mNab+ and mNab− pups 18 h after infection. IgG and IgA signals are gated on GFP+ population. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 4–7 mice per group in each experiment). g, Serum IgG levels after 1 week of cross-fostering. h, Small-intestinal IgG levels after 1 week of cross-fostering. i, Small-intestinal IgA levels after 1 week of cross-fostering. j, ETEC 6 bacterial burdens in the small intestine of pups cross-fostered for 1 week. ***P = 0.0002, two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test. Data are representative of two independent experiments. a–d, g–j, Data are mean ± s.e.m. Specific n numbers are indicated in the figure.

Using flow cytometry analysis, we investigated which antibody class was likely to mediate protection. Commensal bacteria from the microbiota of uninfected mNab+ pups were coated with both IgG and IgA, whereas bacterial cells from mNab− pups were negative for IgG and IgA (Fig. 1e), indicating that both maternal IgG and IgA that react with the commensal microbiota are transmitted vertically to neonates. Flow cytometry detected only IgG—but not IgA—on green-fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing ETEC (ETEC–GFP) cells (Fig. 1f). It has previously been shown that immunization-induced antigen-specific milk IgG coats Citrobacter in the mucosa18. Our results re-affirm that maternal natural IgG in milk coats pathogenic bacterial cells (in our study ETEC 6), and further demonstrate that protection is conferred to breast-feeding pups, even without prior exposure of the mother to the pathogen.

The composition of the neonatal gut microbiota in mNab+ and mNab− animals was similar and therefore probably not responsible for the differential protection against ETEC (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Exposure to maternal antibodies also suppressed the transcription of type-1 interferon-related genes in the small intestine of ETEC-infected pups (Extended Data Fig. 2c).

Milk mNabs are critical to ETEC protection

To determine whether milk-acquired antibodies are protective, we orally challenged two groups of cross-fostered pups with 109 CFU of ETEC 6 (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Thus, mNab− pups were fostered by μMT+/− dams and received their antibodies (that is, μMT−/−-to-μMT+/− pups) for 1 week only from milk, whereas mNab+ pups were fostered by μMT−/− dams (that is, μMT+/−-to-μMT−/− pups). IgG titres of μMT−/−-to-μMT+/− pups in the serum and small intestine were significantly higher than those of μMT+/−-to-μMT−/− pups (Fig. 1g, h); the same trend was observed for IgA in the small intestine (Fig. 1i), and IgG and IgA in the colon (Extended Data Fig. 3b, c). The μMT−/−-to-μMT+/− pups had a bacterial burden in the small intestine that was approximately 30-fold lower than μMT+/−-to-μMT−/− pups (Fig. 1j). In another cross-fostering experiment, pups born to μMT−/− dams were divided into two groups and cross-fostered by μMT+/− dams or their own μMT−/− dams (Extended Data Fig. 3d). The mNab− pups fostered by μMT+/− dams (μMT−/−-to-μMT+/− pups) were resistant to ETEC 6 infection: 90% survived challenge at 20 h. By contrast, only 20% of mNab− pups raised by their own μMT−/− dams survived (Extended Data Fig. 3e). This result confirms the importance of milk-derived mNabs in blocking ETEC 6 colonization and provides the mechanism by which milk-derived antibodies protect against ETEC 6 challenge.

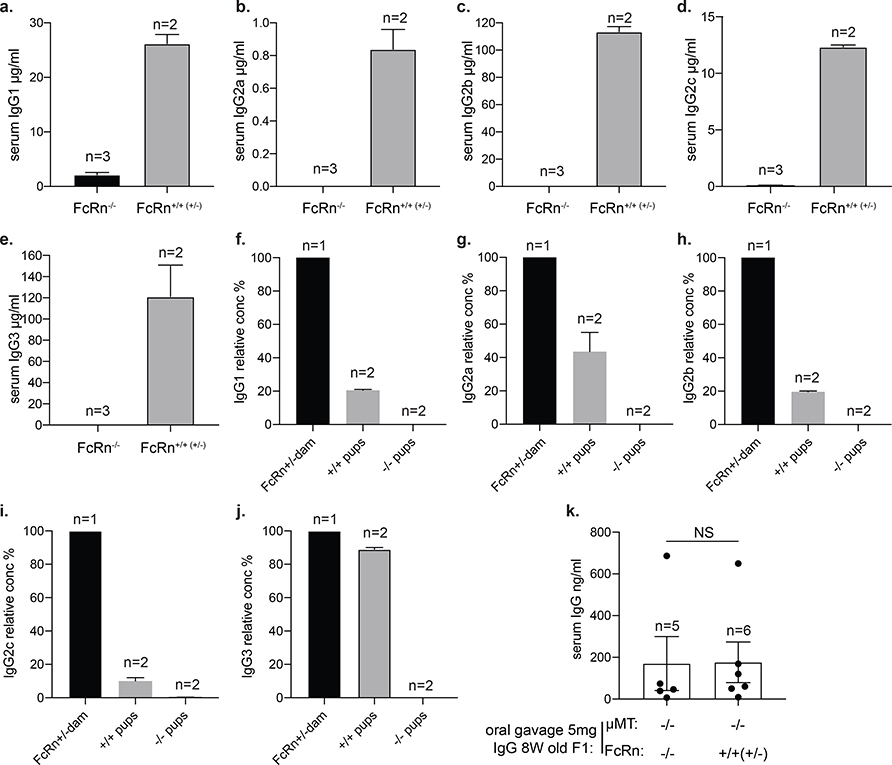

FcRn uptake of milk mNabs into the serum

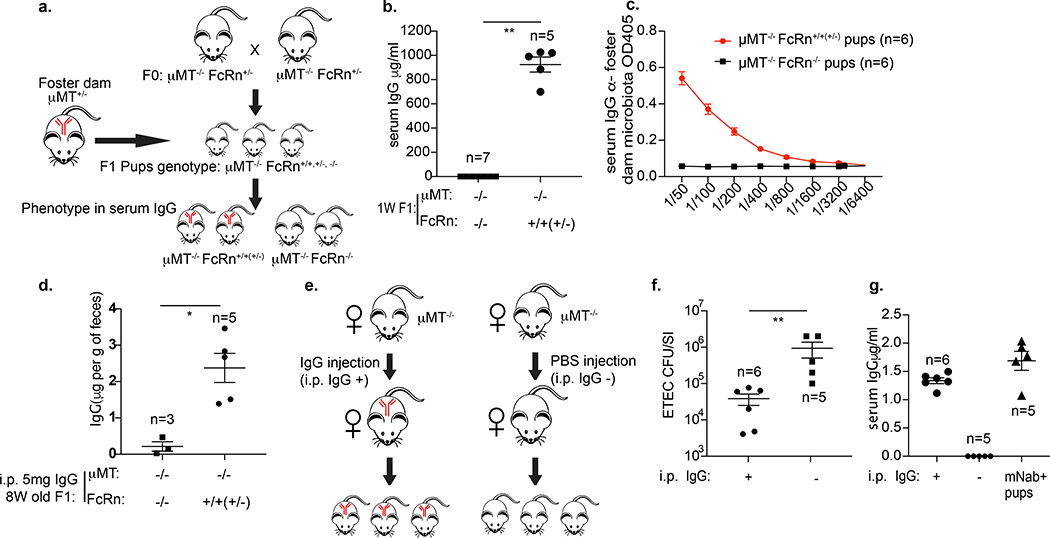

In prenatal mice, FcRn transports IgG across the placenta to the fetus, primarily in the third trimester19. In adult mice, FcRn transports IgG from the gut lamina propria to the intestinal lumen; mice deficient in FcRn display impaired resistance to the enteric pathogen Citrobacter rodentium20. Because FcRn can have a high affinity for IgG and is expressed neonatally on intestinal epithelial cells21,22, we investigated whether FcRn transports IgG in the opposite direction, binding IgG in milk in the intestinal lumen and delivering it to the serum of suckling pups. We used a breeding and fostering strategy to separate the postnatal from prenatal antibody-transfer processes (Fig. 2a). μMT−/− FcRn+/− mice were used to generate littermate pups deficient in maternal antibodies. Newborn pups were immediately fostered by μMT+/− dam for 1 week. μMT−/− pups sufficient in FcRn had almost 1 mg of IgG per ml of serum, whereas μMT−/− FcRn−/− (also known as Fcgrt−/−) pups had no detectable serum IgG (Fig. 2b). In FcRn-sufficient pups, some IgG was directed towards the maternal microbiota (Fig. 2c). Thus, in suckling mice, FcRn transports IgG from ingested milk into the serum. Although FcRn can transport all subclasses of milk IgG to the neonatal circulation (Extended Data Fig. 4a–e), the relative serum concentrations of IgG3 and IgG2c (pup:dam ratios) are the highest and lowest, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 4f–j), suggesting that IgG3 is transferred preferentially and IgG2c the least efficiently. We then compared the role of FcRn in transferring IgG in adults versus neonates. We injected IgG (5 mg) intraperitoneally into 8-week-old littermates from crosses between μMT−/− (no antibody production) and either FcRn−/− or FcRn+/− (or FcRn+/+) mice. We sampled the faeces 1 day later. μMT−/−FcRn+/− (or μMT−/−FcRn+/+) mice had significantly higher faecal IgG levels than μMT−/−FcRn−/− mice (Fig. 2d). Thus, IgG transfer from the systemic circulation to the intestinal lumen primarily depends on FcRn. However, when we orally gavaged IgG (5 mg) into these adult mice and sampled the serum 1 day later, we found that both μMT−/−FcRn−/− and μMT−/−FcRn+/− (or μMT−/−FcRn+/+) mice had detectable but similarly low IgG levels. This experiment suggests that IgG transfer from lumen to serum in adult mice is poor and—in contrast to that in neonates—is not dependent on FcRn (Extended Data Fig. 4k); however, it is also possible that IgG given to adult mice by gavage was simply destroyed by proteolysis that does not occur in neonates.

Fig. 2 |. FcRn mediates postnatal IgG retro-transport.

a, Breeding and fostering strategy to specifically study the postnatal milk IgG transfer process. All pups discussed in this figure are μMT−/−. b, Serum IgG levels in 1-week-old FcRn-deficient or FcRn-sufficient μMT−/− pups after 1 week of fostering by a μMT+/− dam. **P = 0.0013, two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test. Data are representative of two independent experiments. c, Titres in pups of IgG specific to the microbiota of the foster dam. Data are representative of two independent experiments. d, Adult (8-week-old) mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with 5 mg of IgG, and faeces samples were collected 1 day later. Faecal IgG levels are shown as μg per gram of faeces. *P = 0.0357, two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test. Data are representative of two independent experiments. e, IgG treatment scheme of dams treated with IgG, data for the pups were tested are shown in f and g. f, Comparison of ETEC 6 bacterial burden in the small intestine of pups from untreated μMT−/− dams and from μMT−/− dams treated with IgG. **P = 0.0043, two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test. Data are representative of two independent experiments. g, Serum IgG levels of pups from untreated μMT−/− dams compared with μMT−/− dams treated with IgG. Data are representative of two independent experiments. b–d, f, g, Data are mean ± s.e.m. Specific n numbers are indicated in the figure.

IgG binding to the microbial surface can drive immune-effector functions such as complement-dependent bacteriolysis and opsonization, and because flow cytometry–analysed ETEC 6 cells were coated with IgG but not IgA in vivo, we hypothesized that maternal natural IgG was the immunoglobulin class that provided protection against ETEC. We synchronized the pregnancy of two μMT−/− female mice mated with different μMT−/− male mice. On gestational day 18 and postpartum day 2, one female received intraperitoneal injections of IgG (12 mg) purified from specific-pathogen-free (SPF) wild-type mice; the other received injections of only PBS (Fig. 2e). At 1 week of age, pups from these dams were challenged by the oral–gastric route with 107 CFU of ETEC 6. Pups born to the IgG-treated μMT−/− dam were highly protected and carried an approximately 25-fold lower small-intestinal bacterial load than pups born to the untreated dam (3.8 × 104 CFU per small intestine compared with 9.4 × 105 CFU per small intestine; Fig. 2f). Thus IgG, in the absence of IgA, provides measurable protection against ETEC 6 challenge in nursing pups. We measured serum IgG titres in μMT−/− pups fed on a μMT−/− dam given the same passive IgG treatment and found titres that were comparable to those found in pups born to a μMT+/− dam (Fig. 2g). Thus, supplementing IgG antibodies to a pregnant or postpartum dam is sufficient to protect the pups that she nurses from ETEC 6 infection.

Commensal Pantoea elicits mNabs protective against ETEC

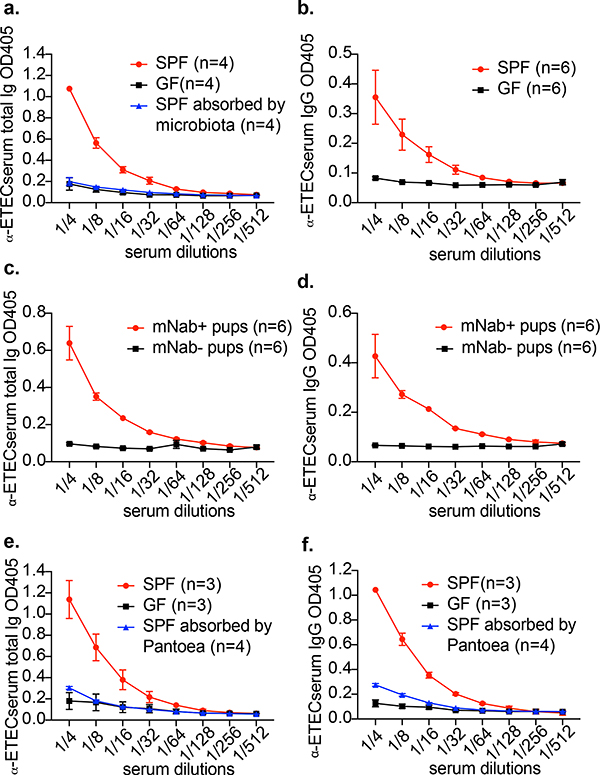

The protection against ETEC of pups born to or nursed by mNab+ dams suggests that conventionally colonized (SPF) mice carry cross-reacting natural antibodies against ETEC 6. Indeed, total ETEC-6-directed serum immunoglobulin and IgG titres are significantly higher in SPF mice than in germ-free mice (Fig. 3a, b), suggesting that the SPF commensal microbiota induces antibodies that cross-react with ETEC 6 in dams. Absorption of SPF mouse sera with faecal bacteria completely removed ETEC cross-reactive antibodies. (Fig. 3a). At 1 week of age, mNab+ (μMT+/− dam) pups had substantial serum titres of ETEC-6-specific total immunoglobulin and IgG antibodies—presumably cross-reacting antibodies generated to commensal antigens—whereas sera from mNab− (μMT−/− dam) pups contained no detectable immunoglobulin that bound to this strain (Fig. 3c, d). Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae were isolated through the culture of faeces from μMT+/− dams. Mice from both our in-house breeding facility and The Jackson Laboratory lacked viable lactose-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli in their faeces. We could isolate only two lactose-non-fermenting Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae species—a Pantoea and an Enterobacter species, each identified by 16S rDNA gene sequencing—from μMT+/− dams. We used the Pantoea 1 strain to absorb antibodies from mouse serum. Pantoea-1-absorbed SPF serum showed reduced titres of ETEC-reactive total immunoglobulin and IgG (Fig. 3e, f). These data support the hypothesis that some commensal microbiota species elicit cross-reactive antibodies against ETEC.

Fig. 3 |. The commensal microbiota elicits antibodies that cross-react with ETEC 6.

a, Total immunoglobulin titres against ETEC 6 in serum from germ-free (GF) and SPF adult female mice as well as in serum from SPF mice absorbed by mouse microbiota. Data are representative of four independent experiments. OD405, optical density at 405 nm. b, IgG titres against ETEC 6 in serum from germ-free and SPF mice. c, Total immunoglobulin titres against ETEC 6 in serum from 1-week-old neonatal mNab+ and mNab− mice obtained by reciprocal breeding. d, IgG titres against ETEC 6 in serum from 1-week-old neonatal mNab+ and mNab− mice obtained by reciprocal breeding. e, Total immunoglobulin titres against ETEC 6 in serum from germ-free mice, serum from SPF mice and Pantoea-1-absorbed serum from SPF mice. f, IgG titres against ETEC 6 in serum from germ-free mice, serum from SPF mice and Pantoea-1-absorbed serum from SPF mice. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Specific n numbers are indicated in the figure.

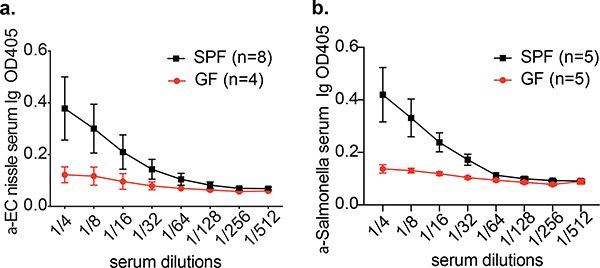

We wondered whether mNabs in mice showed cross-reactivity with other common enteric bacteria, including other pathogens and probiotic microorganisms. We measured antibody titres in sera of germ-free and SPF mice of antibodies against E. coli Nissle, a human commensal bacterial isolate that has been used as a probiotic and is not present in the mouse gut, and to Salmonella typhimurium, a pathogen in both humans and mice. Sera from SPF mice have higher total immunoglobulin titres to E. coli Nissle and S. typhimurium than sera of germ-free mice (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b). This result suggests that some commensal strains of Proteobacteria induce antibodies that recognize other proteobacterial species and strains.

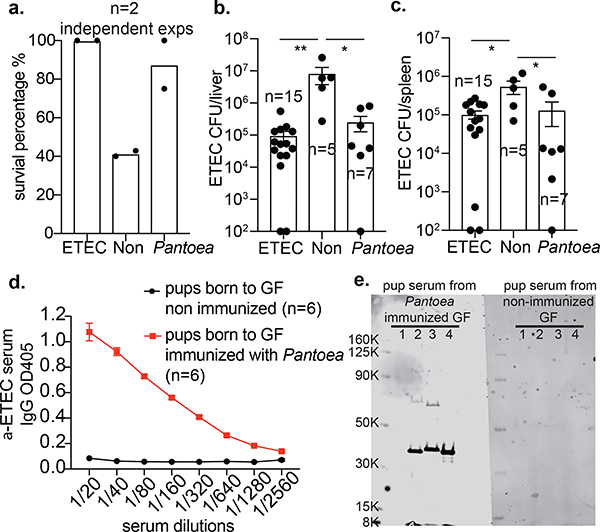

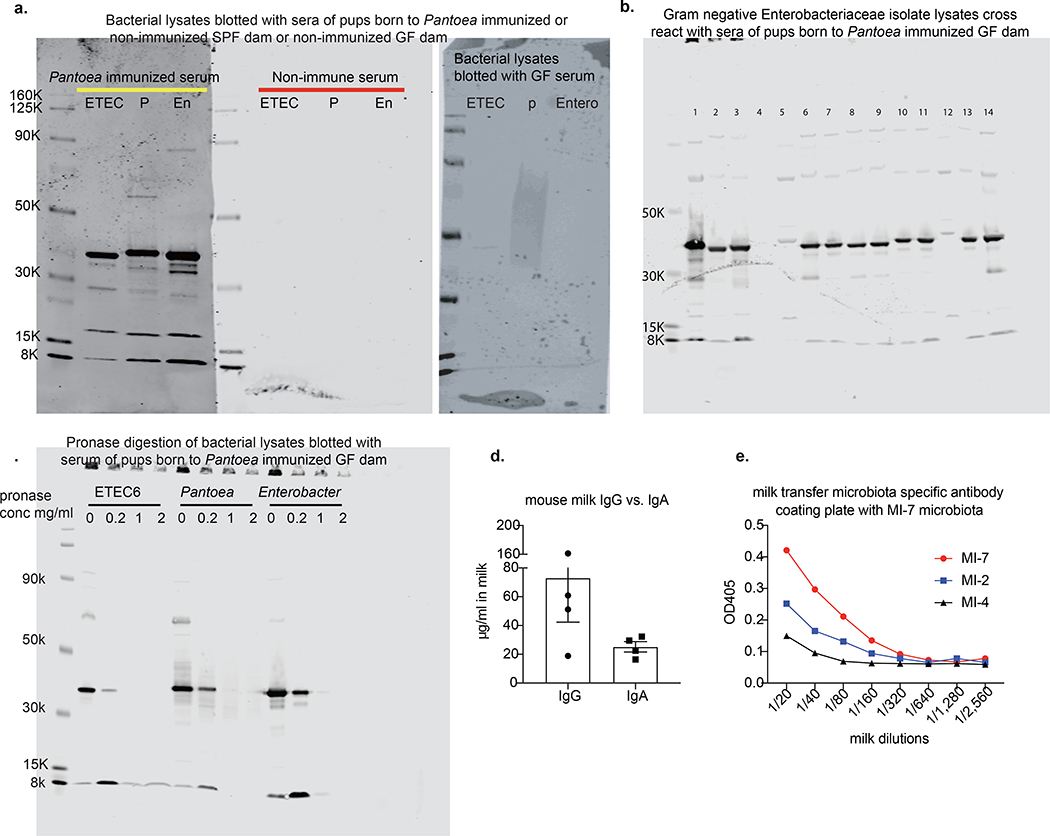

To determine whether a single commensal species is sufficient to confer protection against ETEC 6 infection, we immunized germ-free dams either with a formalin-killed commensal Pantoea 1 strain or with a formalin-killed ETEC 6 strain and used unimmunized mice as a control group; then all three groups of pups were infected with ETEC6. We found that pups born to germ-free dams immunized with Pantoea 1 were significantly more protected against ETEC 6 than pups born to unimmunized germ-free dams (Fig. 4a–c). IgG collected from pups born to Pantoea-1-immunized germ-free dams showed cross-reactivity to ETEC 6 (Fig. 4d) and the enteric pathogen C. rodentium. Furthermore, all the commensal Enterobacteriaceae isolates from mice found in three different vivariums were cross-reactive with the Pantoea anti-serum, but did not react with mouse or human commensal strains of Staphylococcus or Bacteroides. Pups of germ-free unimmunized dams had no detectable antibodies against ETEC 6 or these other bacterial species (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). Western blot analysis of pronase-treated bacterial lysates showed elimination of a band cross-reactive with anti-Pantoea IgG, suggesting this immunoreactive material is a protein (Extended Data Fig. 6c). We also measured IgG and IgA antibody content in milk samples from conventional SPF mice and found an IgG concentration that was approximately threefold higher than the concentration of IgA (Extended Data Fig. 6d); IgG titres in the milk of a given mouse dam were higher against the stool microbiota of the homologous dam than against that of a heterologous dam (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Collectively, these data suggest that the commensal microbiota can induce cross-reactive, protective antibodies against pathogens.

Fig. 4 |. Immunization of dams with commensal microorganisms conveys neonatal protection against pathogens.

a, Survival of pups born to ETEC-6- or Pantoea-1-immunized dams or unimmunized dams. Data are from two individual experiments (first experiment, ETEC n = 12 mice, unimmunized (non) n = 7 mice, Pantoea n = 4 mice; second experiment, ETEC n = 5 mice, unimmunized n = 5 mice, Pantoae n = 4 mice). b, Liver total bacterial burdens 3 days after intraperitoneal ETEC 6 challenge. **P = 0.0025, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-test. Data are from two independent experiments. c, Spleen bacterial burdens 3 days after intraperitoneal ETEC 6 challenge. **P = 0.0041, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. Data are from two independent experiments. d, Cross-reactivity against ETEC 6 of serum IgG from pups born to germ-free dams with or without Pantoea 1 immunization. e, Western blot showing that serum IgG of pups born to a Pantoea-1-immunized dam recognizes antigens in cellular lysates of members of the Enterobacteriaceae family (ETEC 6, Pantoea 1 and Enterobacter). Lane 1, Staphylococcus; lane 2, ETEC 6; lane 3, Pantoea 1; lane 4, Enterobacter. Blot is detected with goat anti-mouse IgG antibody. Data are representative of three independent experiments. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1. b–d, Data are mean ± s.e.m.

Discussion

Of the many causes of death due to bacterial pathogens among children under 5 years old, acute infectious diarrhoea is surpassed only by pneumonia23. Neonates in developing countries have frequent diarrhoeal episodes that result in high mortality rates; the major infectious agents, which account for around 1.5 million deaths annually, are ETEC, rotavirus, Vibrio cholerae and Shigella24,25. ETEC is a frequent cause of diarrhoea in infants under 2 years old26. Epidemiological data indicate that breast-feeding reduces overall rates of diarrhoea and mortality26,27; however, the underlying mechanisms by which breast milk provides protection are not clear. Our results suggest that breast-feeding by mothers who lack specific immunity to ETEC may protect infants from ETEC by delivering natural antibodies—which are elicited by the commensal microbiota—that cross-react with this pathogen. The data presented here on cross-species protection by antibodies generated to a commensal organism are all based on mouse studies; further studies to address their relevance in humans are important.

IgG present in the breast milk of a selected dam reacted more strongly with the microbiota of that dam compared to the microbiota of other dams. We hypothesize that commensal species probably vary in their capacity to induce cross-reacting antibodies that recognize any given pathogen, such as ETEC. Beyond antigens shared by specific bacterial groups (for example, lipopolysaccharides of Gram-negative bacteria), some antigens can be expressed by diverse and phylogenetically distant bacterial species, including commensal microorganisms28. Moreover, poly-reactive IgM can recognize both pathogenic and commensal bacteria and affords some protection against pathogen challenge in mice29. Thus, our study indicates that modulation of the maternal microbiota to optimize the induction of cross-reactive antibodies that are protective against important neonatal pathogens should be explored.

The role of secretory IgA in humoral responses to enteric pathogens has been widely studied30. The function of other antibody classes (for example, IgG) at mucosal sites or in breast milk has attracted less attention, primarily because IgG is thought to be present at lower concentrations and to be less stable in mucosal secretions31–33. The consensus has been that secretory IgA in breast milk probably mediates protection34. Human and rodent milk contains substantial amounts of both secretory IgA and IgG35,36. In mice, microbiota-induced maternal IgG in milk is present in the neonatal gut mucosa and is taken up into the serum of breast-feeding neonates. Thus, breast-feeding theoretically could provide IgG-mediated protection against invasive pathogenic bacterial species at sites where the effector mechanisms function, such as mucosal or submucosal surfaces, bloodstream or deeper tissues.

One important, previously unresolved question was whether orally delivered IgG (acquired by neonates through the milk of the mother) enters the bloodstream through a specific IgG transporter. Previous studies detected such transport for certain immunoglobulin classes10 but did not clearly define the pathway for uptake. In vitro studies yielded evidence that FcRn recognizes IgG and transports it bidirectionally across an epithelial monolayer37. Our work in mice suggests that, dependent on FcRn, IgG in milk can enter the bloodstream of neonatal mice and confer potent protection—presumably through IgG-dependent effector functions such as complement classical pathway-dependent bacteriolysis or opsonization38. We also uncovered an FcRn-dependent pathway for retro-transport of IgG (Extended Data Fig. 7) relative to secretory processes mediated by the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor, which transports IgA and IgM from the basolateral to the apical surface and lumen of the intestine39. In the MDCK cell line, luminal-to-basolateral IgG transport reportedly requires antibody–antigen complexes and FcRn40; we did not observe transport of IgG from lumen to serum in adult mice. Although FcRn is thought to function bidirectionally, we observed that, in the mouse, the bidirectionality may be subject to an age-dependent temporal sequence (that is, in neonates, from lumen to submucosa; in adults, from submucosa to lumen). Characterizing this transport pathway in humans is a future priority because vaccination of women may generate high-affinity IgG, protecting breast-fed neonates long after antibodies received through the placenta have waned from the bloodstream. We have not addressed whether this milk-mediated gastrointestinal pathway for introducing therapeutic or preventive IgG into the bloodstream is applicable to human neonatal infants. If efficient and practical, this non-invasive approach offers advantages over conventional passive-immunization strategies by avoiding needle use in newborns, a practice that carries additional risk of disease transmission.

METHODS

Mouse breeding strategy

Reciprocal breeding was used to generate pups which were sufficient or deficient in maternal antibodies. μMT−/− pups in the mNab+ group were used to evaluate the persistence of mNab and μMT+/− pups in the mNab- group were used to evaluate the emergence of endogenous antibodies.

μMT−/− mice (stock no. 002288) and wild-type C57BL/6J mice (stock no. 000664) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and bred to generate F1 μMT+/− mice. F1 μMT+/− female mice were bred with μMT+/− males to generate F2 progeny. F2 or F3 μMT+/− female × μMT−/− male breeding and μMT−/− female × μMT+/− male breeding were synchronized to generate F3 mNab+ pups as well as mNab− pups. These pups were used for studies of ETEC 6 infection, in which serum and mucosal antibody levels were measured. FcRn−/− mice (Jackson Laboratory, stock no. 003982) and μMT−/− mice were used to generate the F1 μMT+/−FcRn+/− progeny. F1 μMT+/−FcRn+/− mice were then used to generate F2 μMT−/−FcRn+/− progeny. F2 mice were used to generate μMT−/−FcRn−/− or μMT−/−FcRn+/− (or μMT−/−FcRn+/+) mice. Germ-free C57BL/6J mice were bred and maintained in mouse facilities at Harvard Medical School. Germ-free mice were housed in standard isolators and were free of all bacteria, fungi, viruses and parasites; sterility was verified by regular-interval aerobic and anaerobic cultures as well as PCR. All animal studies were approved by the IACUC of Harvard Medical School under animal protocol IS:00000178–3. Mouse genotyping followed the Jackson Laboratory genotyping protocol for stock no. 002288 and for stock no. 003982 (The Jackson Laboratory).

Microbiota composition analysis

Faecal contents were scraped off the intestines of 1-week-old pups and DNA was extracted with a QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, 51604). The V4 region of 16S rRNA gene was amplified with paired-end 16S rRNA gene primers 515F and 806R41, and approximately 390-bp amplicons were purified and then subjected to multiplex sequencing (Illumina MiSeq, 251 nucleotides × 2 paired-end reads with 12-nucleotide index reads). Raw sequencing data were analysed with QIIME2 pipelines42. The feature table of gut microbiota was then used for alpha and beta diversity analysis, as well as taxonomic analysis and differential abundance testing.

Enteric pathogen infection of neonatal mice

In the intestinal infection model, to estimate bacterial burden, E. coli strain ETEC 6 (107 CFU in 50 μl PBS buffer) was administered orally by gavage to 6-day-old pups using an insulin needle connected to polyethylene tubing (Intramedic, 4274010). The ETEC 6 strain was a gift from F. Qadri; genome sequence NCBI BioSample Accession number SAMN12263012.) Animals were monitored closely and euthanized 20 h later, and bacterial burdens (CFU per organ) were determined. MacConkey agar plates with specific antibiotics were used for the cultivation of ETEC 6. To estimate survival, ETEC 6 (109 CFU) was administered orally by gavage to pups, and the condition of the mice was closely monitored. A moribund condition was recorded as the experimental end point, and survival (defined as the percentage of animals that were alive compared to those that were moribund or dead 20 h after challenge) was recorded. In the systemic infection model, ETEC 6 (107 CFU) was administered intraperitoneally to 10–12-day-old pups, and the condition of the mice was closely monitored. A moribund condition was recorded as the experimental end point, and the survival at 3 days after infection was recorded. Moribund 6–7-day-old animals were defined as those that were grey rather than pink in colour and were not responsive to manual stimulation; older mice (older than 10 days of age) were defined as moribund if they displayed abnormal posture, rough hair coat, exudate around eyes and/or nose, skin lesions, abnormal breathing, difficulty with ambulation, low food and water intake or self-mutilation.

Isolation of mouse-gut commensal Enterobacteriaceae bacteria

Small-intestinal homogenates were plated on MacConkey agar plates without antibiotics and incubated aerobically at 37 °C overnight. Colonies were purified and DNA was extracted. The 16S rDNA gene was amplified by PCR and sequenced with 27F and 1492R primers43.

RNA sequencing

Illumina sequencing libraries were built using the Ovation RNA-Seq System V2 (NuGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and were submitted to the Harvard Biopolymers Facility for sequencing on the Illumina NextSeq 500, resulting in 287 million high-quality 50-nucleotide paired-end reads. Differential expression analysis was performed with the Bioconductor package DEseq244.

Total IgG and IgA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

Sera and mucosal antibodies of the neonates were measured with a mouse IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Abcam, ab157719) and a mouse IgA ELISA kit (Abcam, ab157717). Serum samples were diluted in the 1:20,000–1:40,000 range for IgG detection. Mucosal samples—from either the small intestine or the colon—were homogenized in 1 ml of PBS and centrifuged. Only supernatants were used for ELISA. For measurement of faecal antibodies, faecal pellets were weighed and resuspended as 100 mg ml−1 stock solutions in PBS buffer before further dilution for ELISA. Results were read with a BioTek Synergy HT Multi Mode Microplate Reader at OD450. For absorption assays, formalin fixed commensal bacterial or Pantoea cells (108 CFU) were incubated with sera, and after 1 h bacterial cells were removed by centrifugation. Absorbed serum samples were diluted and used for ELISA as described below.

ETEC cross-reactivity ELISA

The cross-reactivity of mouse serum antibodies with ETEC 6 cells was assessed by whole-cell ELISA. In brief, ETEC 6 bacterial cells were treated with 0.5% formalin at room temperature for 2 h and then washed twice with sodium-carbonate-coating buffer. About 108 CFU per 100 μl of fixed ETEC 6 cells in coating buffer were added to each well of a NUNC Maxisorp ELISA plate (Thermo Fisher, 44–2404-21) and then incubated overnight at 4 °C. Wells were washed with PBST (PBS and 0.05% Tween-20) and blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBST buffer for 2 h at room temperature. Next, 2% nonfat milk in PBST was used for serum dilutions; the addition of 50 μl of diluted serum to each well (as replicates) was followed by incubation at room temperature for 1 h. The following secondary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:2,000: anti-mouse immunoglobulin–HRP (SouthernBiotech, 1010–05) or anti-mouse IgG–HRP (SouthernBiotech Cat. No. 1030–05). Super Aqua Blue substrate (Thermo Fisher, 00–4203-58) was used for colour detection. Titres of antibody to ETEC 6 were read with a BioTek Synergy HT Multi Mode Microplate Reader at OD405.

Construction of the ETEC–GFP strain

The plasmid pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-Tp-gfpmut3 was electronically transformed into ETEC 6 competent cells. The successful transformant was selected, confirmed to be positive for GFP by PCR as well as by flow cytometry, and designated ETEC–GFP.

Detection of antibody deposition on in vivo-recovered ETEC cells

To analyse the IgG and IgA coating of ETEC 6 bacteria ex vivo, mice infected with ETEC–GFP were euthanized 18–20 h after infection. Small-intestine contents were scraped off, washed and filtered (filter pore size, 5 μm; Pall Acrodisc, 4650) for recovery of bacteria. Faecal bacteria were resuspended in PBS with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche, 11873580001) and incubated with shaking at 37 °C for 5–10 min to facilitate GFP maturation and detection by flow cytometry. Faecal bacteria were blocked with 2% BSA in PBS buffer and stained with diluted (1:100) anti-mouse IgG–647 (Biolegend, 405322) or anti-mouse IgA–APC (SouthernBiotech, 1165–11). Isotype controls were Alexa Fluor 647 goat IgG (Biolegend, 403006) and rat IgG1–APC (SouthernBiotech, 0116–11). Stained bacteria were washed with PBS and analysed by MACsquant (Miltenyi Biotec). Data were analysed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Exogenous antibody supplementation in μMT−/− pups

The breeding of two μMT−/− female mice was synchronized to generate two litters of pups born within a 12-h time frame. Purified SPF mouse IgG (12 mg; mu-003-C.05, ImmunoReagents) was injected intraperitoneally into one pregnant μMT−/− female at gestation day 18 and again at postpartum day 2. The resulting two litters of μMT−/− pups were used for ETEC 6 infection at 1 week of age.

Cross-fostering experiment

The breeding of a μMT−/− female with a μMT+/− male and the breeding of a μMT+/− female with a μMT−/− male were synchronized to generate pups born on the same day, for subsequent cross-fostering. After 1 week of cross-fostering, pups were used for ETEC 6 infection experiments. Serum and mucosal samples of infected pups were collected for measurement of IgG and IgA titres.

Commensal immunization

Commensal species of Enterobacteriaceae were isolated from SPF mice. One was identified as a Pantoea species (referred to as Pantoea 1). This strain was grown in LB broth to an OD600 of 1.0; cells were then collected by centrifugation and treated with 1% formalin for 1 h before three washes with PBS buffer. Formalin-fixed Pantoea 1 (107 CFU in 100 μl of PBS) was injected intraperitoneally into mice for priming. After 3 weeks, 107 CFU of formalin-fixed Pantoea 1 was again injected intraperitoneally as an immunological boost. Sera were collected from 2-week-old pups for antibody titre determination and used for immunoblotting analysis.

Immunoblotting of bacterial lysates with immunized serum

After growth of ETEC 6, Salmonella and Pantoea 1 isolates in LB broth, bacteria (108 CFU) were collected by centrifugation, lysed with lysis buffer, and run on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris protein gels (Invitrogen, NP0335BOX) at 180 V. Separated products were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes iBlot2 NC mini stacks (Invitrogen, IB23002) with an iBlot transfer device (Invitrogen, IB21001). The nitrocellulose membranes were reacted with immunized mouse serum at a dilution of 1:500 and then blotted with 1:10,000 diluted IRDye680RD goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (LI-COR, 926–68070). Images were taken with an Odyssey Imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences).

Pronase treatment of bacterial lysates

ETEC 6, Enterobacter and Pantoea 1 were grown in LB broth to an OD600 of 1.0, collected, washed three times with PBS buffer and resuspended in half volume of original bacterial culture. Bacterial suspensions were lysed three times (15-s duration) with a Branson Ultrasonics Probe Sonicator. Pronase was added to bacterial lysates to final concentrations of 0, 0.2, 1 and 2 mg ml−1, with subsequent incubation at 42 °C for 1 h. The digested bacterial lysates were used for immunoblotting analysis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

16S rDNA profiling data and the ETEC 6 genome are available in the NCBI database under BioProject PRJNA577743 and BioSample SAMN12263012, respectively.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Persistence and development of maternal antibodies.

The genotypes of mating pairs are indicated under the large mouse cartoons; the small mouse cartoons represent neonates born to the indicated dams and their genotypes. Red symbols denote the presence in neonates of antibodies that either were acquired transplacentally from μMT+/− mothers or, in the case of μMT+/− pups, were generated endogenously after 4 weeks of age. a, Reciprocal breeding scheme to study maternal antibody persistence and development. b, Serum IgG concentration in 1–8-week-old pups. Data are shown as μg ml−1. n = 5–15 mice in each breeding group for every week of 1–8 weeks. Further details are provided in the Source Data. c, IgA concentrations in small-intestine and colon (CO) homogenates from 1-week-old pups. Data are shown as μg per small intestine or colon. d, Faecal IgA concentration in 2–8-week-old pups. Data are shown as μg per g of faeces. n = 6–13 mice in each breeding group for every week of 2–8 weeks. Further details are provided in the Source Data. e, Serum IgM concentration in 1-week-old pups. Data are shown as μg ml−1. f, IgG concentration in small-intestine and colon homogenates from 1-week-old pups. Data are shown as μg per small intestine or colon. g, Faecal IgG concentration in 2–8-week-old pups. Data are shown as μg per g of faeces. n = 5–9 mice in each breeding group for every week of 2–8 weeks. Further details are provided in the Source Data. b–g, Data are mean ± s.e.m. Specific n numbers are shown in the figure.

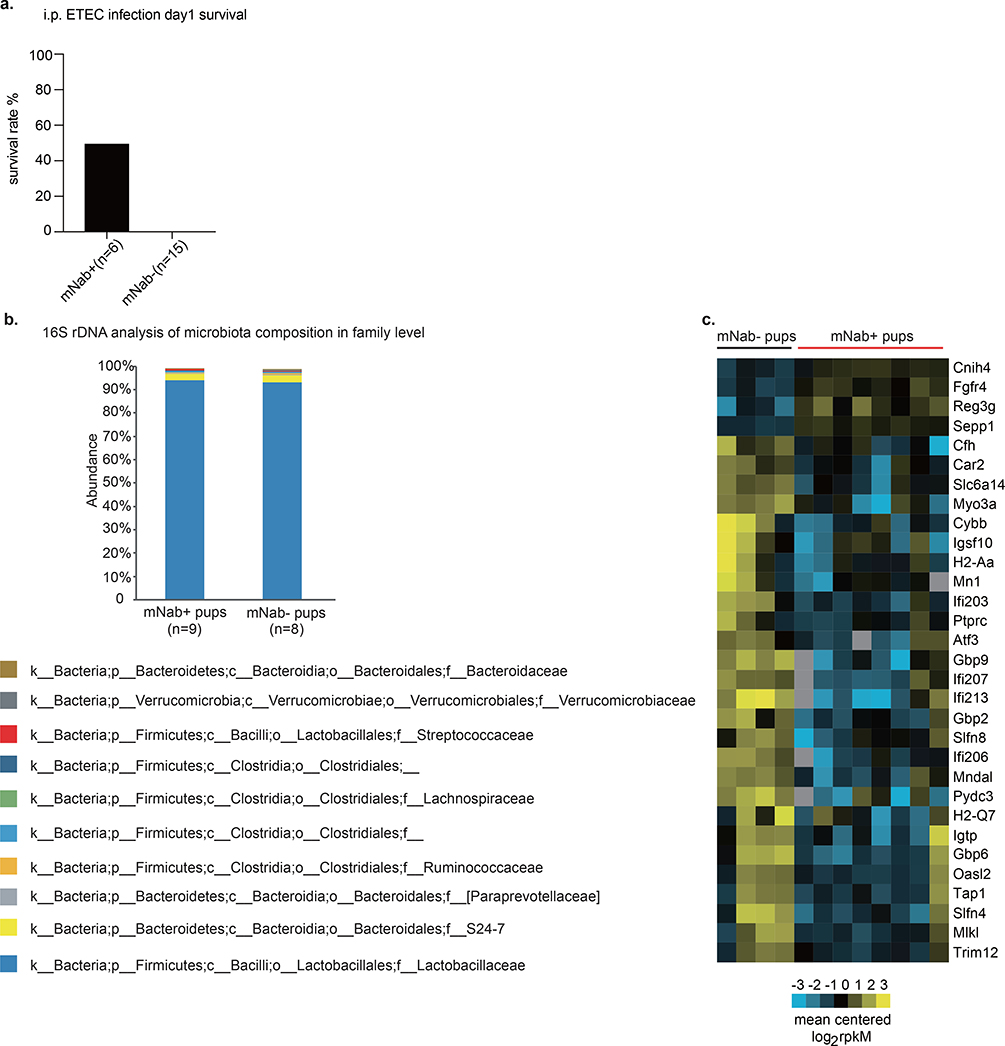

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Comparison of mNAb+ and mNab− pups.

a, Survival of 2-week-old mNAb+ and mNab− pups on day 1 after intraperitoneal challenge with 107 CFU of ETEC 6. mNab+ group, n = 6; mNab− group, n = 15. b, 16S rRNA gene analysis of the composition of the microbiota in 1-week-old reciprocally bred pups. Data are the average of 8 or 9 individual pups from each group; mNab+ group, n = 9; mNab− group, n = 8. c. Transcriptome analysis of small intestines of ETEC-6-infected mNab+ and mNab− pups using RNA sequencing. n = 8 mNab+ pups; n = 4 mNab− pups. Specific n numbers are shown in the figure.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Comparison of pups from the cross-fostering experiment.

For all panels, cross-fostering histories of neonates are denoted by horizontal arrows that provide the genotype of the pup followed by the genotype of the fostering dam. a. Cross-fostering experimental scheme. The genotypes of dams are indicated under the large mouse cartoons; the small mouse cartoons represent neonates that are born to those dams and have the same genotype as their mothers. Thicker arrows define the mother that fostered the indicated neonates. Red symbols denote the presence in neonates of antibodies that were acquired transplacentally from their μMT+/− mothers or, in the case of μMT−/− pups, from a μMT+/− fostering dam. b, Colon IgG concentration of 1-week-old cross-fostered pups. Data are shown as μg per colon. c, Colon IgA concentration of 1-week-old cross-fostered pups. Data are shown as μg per colon. d, Fostering scheme of μMT−/− pups cross-fostered by a μMT+/− dam. e, Survival of fostered μMT−/− pups at 20-h after ETEC infection. In the first experiment, n = 5 μMT−/− pups were fostered by μMT+/− dams; n = 5 μMT−/− pups were fostered by μMT−/− dams. In the second experiment, n = 6 μMT−/− pups were cross-fostered by μMT+/− dams; n = 8 μMT−/− pups were fostered by μMT−/− dams. b, c, Data are mean ± s.e.m. Specific n numbers are shown in the figure.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Relative concentrations of all subclasses of IgG between dams and pups.

a–e, Serum IgG subclass concentrations in μMT−/−FcRn+/+ (or FcRn+/−) and μMT−/−FcRn−/− pups fostered by μMT+/− dams for 1 week. f–j, Relative concentrations of all subclasses of IgG between dam and pups. k, Adult (8-week-old) mice were orally gavaged with 5 mg of IgG, and serum IgG concentrations were quantified as ng ml−1. NS, no significant difference; calculated using a Mann–Whitney U-test. Specific n numbers are shown in the figure.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Serum from conventionally colonized (SPF) mice broadly recognizes human commensal bacteria and other enteric pathogens.

a, Total immunoglobulin titres against E. coli strain Nissle 1917 in germ-free and SPF mouse serum. b, Total immunoglobulin titres against Salmonella typhimurium in germ-free and SPF mouse serum. Specific n numbers are shown in the figure.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Characteristics of commensal-immunized and unimmunized serum.

a, Western blot analysis of serum IgG from pups born to Pantoea-1-immunized SPF mice shows epitopes of ETEC 6, Pantoea 1 and Enterobacter, similar in size to those in serum from pups born to Pantoea-1-immunized germ-free mice. b, Serum IgG of pups born to Pantoea-immunized germ-free dams cross-reacts with different Enterobacteriaceae isolates from different facilities. 1, Harvard SGM Pantoea; 2, ETEC 6; 3, Harvard SGM Enterobacter; 4, Bacteroides fragilis NCTC9343; 5, Charles River B6 Proteus mirabilis; 6, Charles River B6 E. coli isolate 1; 7, Charles River B6 E. coli isolate 2; 8, Charles River CD1 E. coli isolate 1; 9, Charles River CD1 E. coli isolate 2; 10, Taconic B6 E. coli isolate 1; 11, Taconic B6 E. coli isolate 2; 12, Taconic B6 Proteus isolate; 13, Taconic B6 Enterobacter isolate; 14, C. rodentium. c, Pronase-treated bacterial lysates blotted with serum IgG of pups born to Pantoea-immunized germ-free dams. The concentrations of pronase are specified in the figure. a–c, Proteins were detected using a goat anti-mouse IgG antibody. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1. d, Mouse milk IgG and IgA concentrations. Data are shown in μg ml−1. e. Mouse milk IgG titre against microbiota. Each line represents an independent mouse. d, Data are mean ± s.e.m.

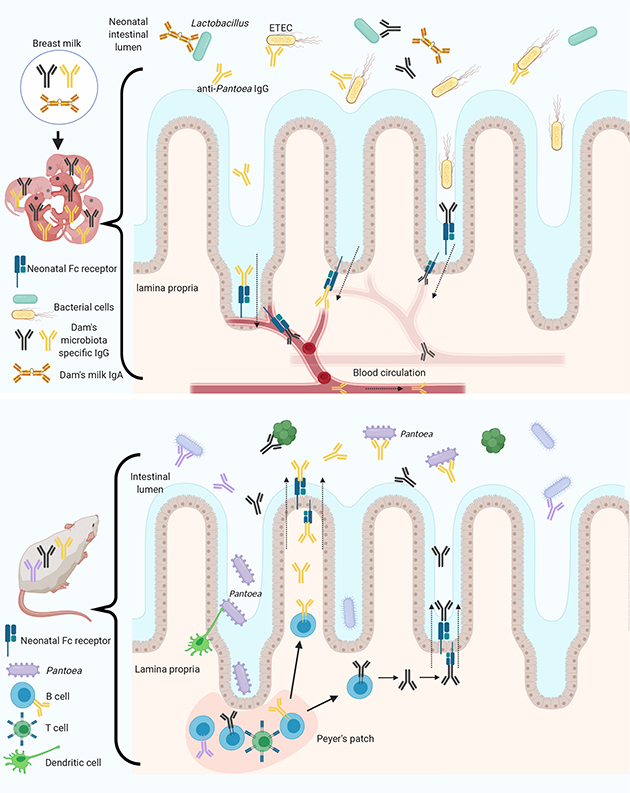

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Schematic summary of the findings in this study.

Top, mNabs induced by commensal microbiota in dams were transferred to neonates through the breast milk. Cross-reacting mNabs (especially IgG antibodies) were detected that bound to the pathogenic, non-indigenous bacterial species ETEC and correlated with protection against disease in pups challenged with ETEC. IgG antibodies were also shown to be transported from the milk to the bloodstream of pups by a process that we call IgG retro-transport. Bottom, mNabs react with many commensal species and among them an Enterobacteriaceae isolate (Pantoea) was found to induce antibodies that cross-react with ETEC. The immunogenicity of this commensal species is hypothesized to be a result of local antigen-sampling processes that involve dendritic cells and uptake by Peyer’s patch germinal centres. This ultimately leads to the induction of high-affinity IgGs directed against a Pantoea antigen that cross-reacts with ETEC. IgG was also shown to be transported from the blood stream to the intestinal lumen by FcRn in adult mice. Illustrations were created with BioRender (https://biorender.com/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the staff in our animal facility for their support in animal husbandry; all Kasper and Mekalanos laboratory members for comments; Y. Chen for technical help; and F. Qadri for providing the ETEC 6 strain. The study was supported by NIH NIAID Center of Excellence for Translational Research Grant 1U19 AI109764 awarded to D.L.K. G.S. and AI-018045 awarded to J.J.M. and was supported in part by funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Marie Skłodowska Curie Grant Agreement 661138.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information Nature thanks Duane Wesemann and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

References

- 1.Basha S, Surendran N & Pichichero M Immune Responses in Neonates. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 10, 1171–1184 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mcmichael A, Simon AK & Hollander GA Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age. Proc Biol Sci 282, 1821 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamada N, Chen GY, Inohara N & Núñez G Control of pathogens and pathobionts by the gut microbiota. Nat. Immunol 14, 685–690 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carbonare CB, Carbonare SB & Carneiro-Sampaio MMS Secretory immunoglobulin A obtained from pooled human colostrum and milk for oral passive immunization. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol 16, 574–581 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanson LAR & Korotkova M The role of breastfeeding in prevention of neonatal infection. Semin Neonatol 7, 275–281 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madoff LC, Michel JL, Gong EW, Rodewald AK & Kasper DL Protection of Neonatal Mice from Group B Streptococcal Infection by Maternal Immunization with Beta C Protein. Infect. Immun 60, 4989–4994 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaman K et al. Effectiveness of Maternal Influenza Immunization in Mothers and Infants. N. Engl. J. Med 359, 1555–64 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Englund JA, Glezen WP, Turner C, Harvey J, Thompson C, S. G. Transplacental Antibody Transfer Following Maternal Immunization With Polysaccharide And Conjugate Haemophilus influenzae Type B Vaccines. J. Infect. Dis 171, 99–105 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kearney JF, Patel P, Stefanov EK & Glenn King R Natural Antibody Repertoires: Development and Functional Role in Inhibiting Allergic Airway Disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol 33, 475–504 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macpherson AJ, Gomez de Agüero M & Ganal-Vonarburg SC How nutrition and the maternal microbiota shape the neonatal immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol 17, 508–517 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y et al. Microbial symbionts regulate the primary Ig repertoire. J. Exp. Med 215, 1397–1415 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Englund JA, Mbawuike IN, Hammill H, Holleman MC & Baxter Barbara D. and Glezen W. Paul. Maternal Immunization with Influenza or Tetanus Toxoid Vaccine for Passive Antibody Protection in Young Infants. J. Infect. Dis 168, 647–656 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boes M, Prodeus AP, Schmidt T, Carroll MC & Chen J A Critical Role of Natural Immunoglobulin M in Immediate Defense Against Systemic Bacterial Infection. J. Exp. Med 188, (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochsenbein AF et al. Control of Early Viral and Bacterial Distribution and Disease by Natural Antibodies. Science 286, 2156–2159 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumgarth N et al. B-1 and B-2 Cell-derived Immunoglobulin M Antibodies Are Nonredundant Components of the Protective Response to Influenza Virus Infection. J. Exp. Med 192, (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayasekera JP, Moseman EA & Carroll MC Natural Antibody and Complement Mediate Neutralization of Influenza Virus in the Absence of Prior Immunity. J. Virol 81, 3487–3494 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou ZH et al. The Broad Antibacterial Activity of the Natural Antibody Repertoire Is Due to Polyreactive Antibodies. Cell Host Microbe 1, 51–61 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caballero-Flores G et al. Maternal Immunization Confers Protection to the Offspring against an Attaching and Effacing Pathogen through Delivery of IgG in Breast Milk. Cell Host Microbe 25, 313–323 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmeira P, Quinello C, Silveira-Lessa AL, Zago CA & Carneiro-Sampaio M IgG placental transfer in healthy and pathological pregnancies. Clin. Dev. Immunol 2012, 1–13 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masuda A et al. Fc Receptor Regulation of Citrobacter rodentium Infection. Infect. Immun 76, 1728–1737 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pyzik M, Rath T, Lencer WI, Baker K & Blumberg RS FcRn: The Architect Behind the Immune and Nonimmune Functions of IgG and Albumin. J Immunol 194, 4595–4603 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Israel EJ et al. Expression of the neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn, on human intestinal epithelial cells. Immunology 92, (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotloff KL et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 382, 209–222 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotloff KL et al. Global burden of diarrheal diseases among children in developing countries: Incidence, etiology, and insights from new molecular diagnostic techniques. Vaccine 35, 6783–6789 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotloff KL et al. The incidence, aetiology, and adverse clinical consequences of less severe diarrhoeal episodes among infants and children residing in low-income and middle-income countries: a 12-month case-control study as a follow-on to the Global Enteric Multicenter St. Artic. Lancet Glob Heal. 7, 568–84 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qadri F, Svennerholm A-M, Faruque ASG & Sack RB Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in Developing Countries: Epidemiology, Microbiology, Clinical Features, Treatment, and Prevention. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 18, 465–483 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thapar N & Sanderson IR Diarrhoea in children: an interface between developing and developed countries. Lancet 363, 641–53 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skurnik D, Cywes-Bentley C & Pier GB The exceptionally broad-based potential of active and passive vaccination targeting the conserved microbial surface polysaccharide PNAG. Expert Rev. Vaccines 15, 1041–1053 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Gallou S et al. A splenic IgM memory subset with antibacterial specificities is sustained from persistent mucosal responses. J. Exp. Med 215, 2035–2053 (2035). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilmore JR et al. Commensal Microbes Induce Serum IgA Responses that Protect against Polymicrobial Sepsis. Cell Host Microbe 23, 302–311 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apter FM et al. Analysis of the roles of antilipopolysaccharide and anti-cholera toxin immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies in protection against Vibrio cholerae and cholera toxin by use of monoclonal IgA antibodies in vivo. Infect. Immun. 61, 5279–85 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michetrti P, Mahan MJ, Slauch JM, Mekalanos JJ & Neutra1 MR Monoclonal Secretory Immunoglobulin A Protects Mice against Oral Challenge with the Invasive Pathogen Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun 60, 1786–1792 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moor K et al. High-avidity IgA protects the intestine by enchaining growing bacteria. Nat. Publ. Gr 544, 498–502 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stuebe A The Risks of Not Breastfeeding for Mothers and Infants. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol 2, 222–231 (2009). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldsmith SJ, Dickson JS, Barnhart HM, Toledo RT & Eiten-Miller RR IgA, IgG, IgM and Lactoferrin Contents of Human Milk During Early Lactation and the Effect of Processing and Storage. J. Food Prot 46, 4–7 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fouda GG et al. HIV-Specific Functional Antibody Responses in Breast Milk Mirror Those in Plasma and Are Primarily Mediated by IgG Antibodies. J. Virol 85, 9555–9567 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dickinson BL et al. Bidirectional FcRn-dependent IgG transport in a polarized human intestinal epithelial cell line. J. Clin. Invest 104, 903–911 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bournazos S & Ravetch JV Diversification of IgG effector functions. Int. Immunol 29, 303–310 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mostov KE Transepithelial transport of immunogblobulins. Annu. Rev. Immunol 12, 63–84 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshida M et al. Human Neonatal Fc Receptor Mediates Transport of IgG into Luminal Secretions for Delivery of Antigens to Mucosal Dendritic Cells. Immunity 20, 769–783 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 41.Caporaso JG et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 108, 4516–4522 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bolyen E et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol 37, 848–857 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki MT & Giovannoni SJ Bias Caused by Template Annealing in the Amplification of Mixtures of 16S rRNA Genes by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 62, 625–630 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Love MI, Huber W & Anders S Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

16S rDNA profiling data and the ETEC 6 genome are available in the NCBI database under BioProject PRJNA577743 and BioSample SAMN12263012, respectively.