Abstract

We present an open-source framework for pulmonary fissure completeness assessment. Fissure incompleteness has been shown to associate with emphysema treatment outcomes, motivating the development of tools that facilitate completeness estimation. Generally, the task of fissure completeness assessment requires accurate detection of fissures and definition of the boundary surfaces separating the lung lobes. The framework we describe acknowledges a) the modular nature of fissure detection and lung lobe segmentation (lobe boundary detection), and b) that methods to address these challenges are varied and continually developing. It is designed to be readily deployable on existing lung lobe segmentation and fissure detection data sets. The framework consists of multiple components: a flexible quality control module that enables rapid assessment of lung lobe segmentations, an interactive lobe segmentation tool exposed through 3D Slicer for handling challenging cases, a flexible fissure representation using particles-based sampling that can handle fissure feature-strength or binary fissure detection images, and a module that performs fissure completeness estimation using voxel counting and a novel surface area estimation approach. We demonstrate the usage of the proposed framework by deploying on 100 cases exhibiting various levels of fissure completeness. We compare the two completeness level approaches and also compare to visual reads. The code is available to the community via github as part of the Chest Imaging Platform and a 3D Slicer extension module.

1. INTRODUCTION

Anatomically, the lungs consist of distinct lobes: the left lung is divided into upper and lower lobes, while the right lung is divided into upper, middle, and lower lobes. Each lobe has airway, vascular, and lymphatic supplies that are more or less independent of those supplies to other lobes. Pulmonary fissures – double layers of visceral pleura that separate the lung lobes – are more radio-opaque than the surrounding lung parenchyma and thus present as bright sheet-like surfaces on CT datasets. As such, they tend to be the most salient cues for identifying boundaries between the lobes.

Incomplete fissures are not uncommon (Aziz et al., 2004), and fissure incompleteness has been shown to associate with emphysema treatment outcomes (Sciurba et al., 2010). Emphysema is one of the pathologic hallmarks of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a disease that affects 28.9 million people (Ford et al., 2013) and is the third leading cause of death in the United States (Ma et al., 2015). Emphysema is characterized by an abnormal enlargement of airspaces and the destruction of alveolar walls. It leads to a loss of pulmonary elastic recoil and the narrowing and collapse of airways, resulting in airflow limitation and an increase in lung volume (Hogg, 2004). In some cases, it can be treated by lung volume reduction procedures. For example, Klooster et al. showed that lung volume reduction using endobronchial valves significantly improved health in patients with severe emphysema characterized by absence of interlobar collateral ventilation (Klooster et al., 2015). In their study, a complete fissure as assessed on high resolution CT was a surrogate for the absence of interlobar collateral ventilation. However, interobserver variation makes qualitative fissure completeness assessment problematic (Koenigkam-Santos et al., 2012), and manual definition of fissure and lobe boundary is prohibitively time consuming given the size of typical high resolution CT images, which typically have hundreds of slices. This motivates the need for accurate, automated fissure completeness assessment.

The task of fissure completeness assessment requires accurate detection of fissures and definition of the boundary surfaces separating the lung lobes, which are typically the byproduct of complete lung lobe segmentation algorithms. The challenges of lung lobe segmentation and pulmonary fissure detection in CT images have received significant attention over the years, and continue to be active areas of research (Doel et al., 2015; Gerard et al., 2018). Fissure detection is a critical task in most lobe segmentation algorithms and is a challenging problem in its own right. Although it typically comprises a step in an overall lung lobe segmentation algorithm, fissure incompleteness and the inherent difficulty in detecting pulmonary fissures robustly have motivated some groups to leverage auxiliary structures in the lung – typically the airway and vascular trees – to help define lobe boundaries during lobe segmentation. Indeed, even when fissures are detected with high enough accuracy to enable accurate lung lobe segmentation, the sensitivity of fissure detection stages may not be sufficient for accurate completeness assessment. Some have also relied on the regularity of lobar anatomy by leveraging anatomical atlases (Van Rikxoort et al., 2010) or shape-space representations (Ross et al., 2013). Additional anatomical cues and representations of known pulmonary anatomical structure can compensate for fissure incompleteness or inadequate fissure detection for the task of lobe segmentation. Additionally, interactive tools enable users to define lung lobe segmentations in the case of automatic algorithm failures. Hence, accurate lung lobe segmentations do not necessarily imply a concomitant sensitive and specific fissure detection.

Fissure completeness measurement approaches have received relatively less attention in the literature compared to lung lobe segmentation and fissure detection. Pu et al. introduced a set of operations to correct for fissure surface irregularity and the presence of holes sometimes seen resulting from their previously published fissure detection method (Pu et al., 2010). This was followed by fissure type determination, complete fissure estimation, and finally fissure integrity quantification. The improvements they proposed were specific to their previously published fissure detection and lung lobe segmentation approaches. Van Rikxoort et al. described a method for automatically quantifying fissure completeness, and they demonstrate their approach on a set of subjects with severe emphysema (van Rikxoort et al., 2012). To estimate fissure completeness, they deployed a previously published fissure detection algorithm followed by lobe segmentation via atlas-based fitting. For a given fissure, completeness was calculated as the percentage of voxels along the corresponding lobar border associated with a detected fissure. However, this tally does not account for differences in surface area intercepted by different voxels: depending on the surface slope at a given point, a voxel at that point may correspond to more or less surface area.

In this paper, we present an open-source framework for fissure completeness estimation that acknowledges a) the modular nature of fissure detection and lung lobe segmentation, and b) that methods to address these challenges are varied and continually developing. The approach we describe is designed to be flexible; it assumes both a lung lobe segmentation image and a fissure detection data set, although we sought to minimize the requirements on these data sets in order to support a variety of representations. It is designed to be readily deployable on existing lung lobe segmentation and fissure detection data sets. This can be an attractive option for research groups that have previously deployed lung lobe segmentation and/or pulmonary fissure detection algorithms. As deployment typically involves quality control stages to identify algorithm failures followed by failure mode recovery measures (which can involve manual corrections), a framework that can be readily deployed on existing, curated datasets can be particularly attractive for large scale data sets.

We have implemented the proposed framework in the Chest Imaging Platform, an open-source toolkit for the quantitative analysis of chest imaging data (San Jose et al., 2015). We provide in the supplement detailed usage of the various commands and operations referenced in the paper. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: in the Methods section, we describe the various components that comprise the fissure completeness assessment framework. In the Software Implementation and Testing section we describe a software test designed to assess the overall framework’s performance. In the Experiments section, we describe the lung lobe segmentation and fissure detection algorithms as well as the data set we use to demonstrate the framework, and in the Results section, we show how quantitative assessment of fissure completeness agrees with visual scores and how two different approaches to tallying fissure completeness – ratio of surface area estimates and ratio of voxel counts – compare to one another.

2. METHODS

In this section, we describe our proposed framework for fissure completeness estimation. We assume that a lung lobe segmentation has been generated, and we also assume a fissure detection representation. The latter can either be a probability map or a binary image where foreground values represent detected fissures.

2.1. Quality Control

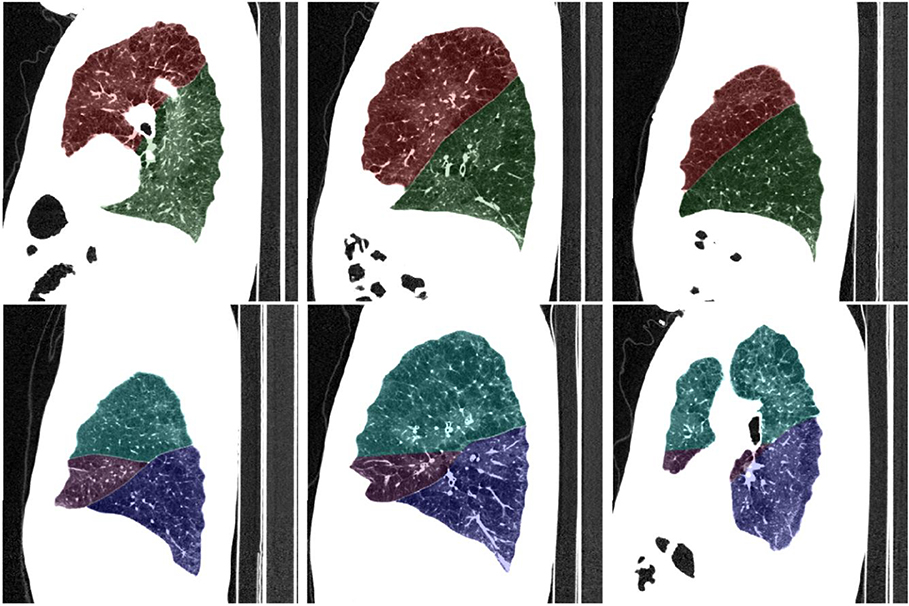

In order to compute an accurate estimate of fissure completeness, it is important to acquire an accurate lung lobe segmentation. In the case where a large number of lobe segmentations have been precomputed, it can be tedious to manually load them into an interactive viewer to inspect the segmentation quality. To address this, we have implemented a flexible quality control montage tool that works with the segmentation labeling conventions adopted in the Chest Imaging Platform. The tool is invoked from the command line and is thus suitable for large scale deployment. The user controls the number of evenly spaced images per sagittal view in both the left lung and the right lung, the overlay opacity, and the window-level settings for the underlying CT image. An example montage image is shown in Figure 1, where we have chosen to render three, evenly-spaced overlays in each lung. By batch-computing montage images offline, a large number of quality control images can subsequently be manually inspected with any standard image viewer in a short amount of time. Images revealing significant segmentation failures can be noted for further processing: either redeployment of the segmentation algorithm with a different parameter setting, or interactive segmentation with a tool of the user’s choosing.

Figure 1.

Overlay images produced by quality control module in the Chest Imaging Platform. Top row: left lung. Bottom row: right lung.

2.2. Interactive Lung Lobe Segmentation

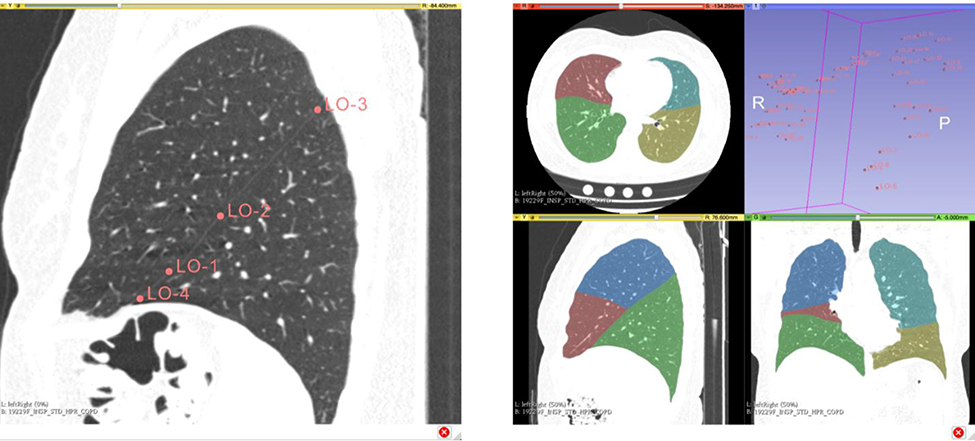

For challenging cases, it might be difficult to produce a sufficiently accurate lobe segmentation using fully automatic approaches. In these cases, interactive segmentation might be required. We have made available the interactive lung lobe segmentation algorithm described in (Ross et al., 2009) as a Chest Imaging Platform Slicer Extension module (Fedorov et al., 2012). The module requires a CT volume and a lung segmentation in which the left and right lungs have been uniquely identified. The user is prompted to interactively click on points along the three main lobe boundaries. The most salient visual cues are the fissures defining the boundaries, but the user can click on any points that he or she believes to be on the lobe boundaries. Typically, only about twenty points evenly spaced across the boundary in 3D are required for the algorithm to define the surface. Figure 2 illustrates the usage of the interactive tool.

Figure 2.

Interactive lung lobe segmentation using 3D Slicer. Left: sagittal slice in the left lung showing four manually selected fiducial points along the left oblique fissure. Right: final lung lobe segmentation based on the user-specified fiducial points (rendered in 3D in the upper-right quadrant).

2.3. Lobe Boundary Surface Area Estimation

Our framework requires a lung lobe segmentation image in order to define thin plate spline (TPS) surface representations of each of the three lobe boundaries of interest (the technical requirements on the segmentation image are described in the supplement). We have previously described the use of thin plate splines to interpolate lobe boundary surfaces given a sparse set of user defined points (Ross et al., 2009), and we later used this representation for boundary shape representation and subsequent fissure classification (Ross et al., 2013). Briefly, TPS interpolating surfaces are minimally curved surfaces that pass through a set of points. The TPS equation is given by

where f(x, y) is the z-value corresponding the axial coordinate (x, y), U(r) = r2log(r) is the radial basis function, and (xj, yj, zj) is the jth of N surface points through which to interpolate. The coefficient vector, (a0, a1, a2), and the weight vector, (w1, …, wN), are determined from the N selected surface points such that the height function’s bending energy is minimized (Bookstein, 1989). In order to identify points along each of the three boundaries of interest, we consider each coordinate in the axial plane and iterate over voxels in the caudal-cranial direction until we identify a transition from one lung lobe label to another. Depending on the particular transition, these voxels identify different lobe boundaries. Any such transition in the left lung identifies the one boundary separating the lower lobe from the upper lobe. In the right lung, a transition from the lower lobe to either the middle or upper lobe identifies the boundary associated with the right oblique fissure. A transition from the middle lobe to the upper lobe identifies the boundary associated with the right horizontal fissure. Given the point sets for each of the three borders, we create corresponding TPS surface representations. In practice, we use a regular subsample of the detected boundary points to define the TPS surfaces (every fourth point in both the x and y directions in our experiments). This accelerates subsequent interpolation operations.

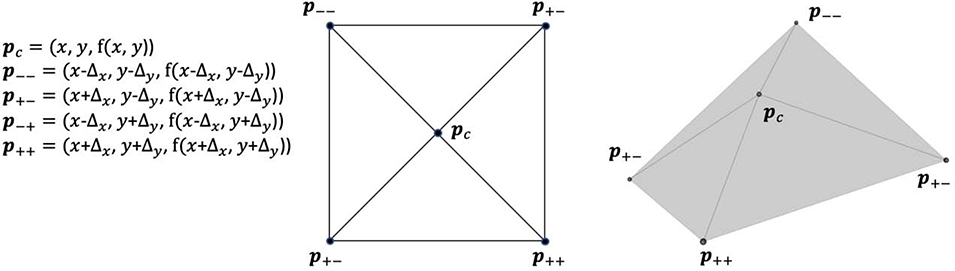

Given TPS surface representations for each of the three lobe boundary surfaces, we estimate their total surface areas as follows. For each of the detected boundary voxels, we use TPS interpolation to compute the z value given the voxel’s (x, y) coordinate and the z values for four neighboring coordinates as depicted in Figure 3. These coordinates define four triangles oriented in 3D space. We compute the area of each triangle using Heron’s formula, and we use the sum as our estimate of the boundary surface area intercepted by the voxel. We repeat this for each of the detected boundary voxels for each of the three boundaries of interest, maintaining a running tally as we iterate.

Figure 3.

Diagram illustrating the approach to estimate the lobe boundary surface area intercepted by a voxel with physical coordinates in the axial plane. Here, Δx and Δy are half of the pixel spacing in the x and y directions in the axial plane. Center: axial plane projection of the triangle vertices. Right: schematic depiction of triangles in 3D. The surface area is estimated as the sum of each triangle’s area.

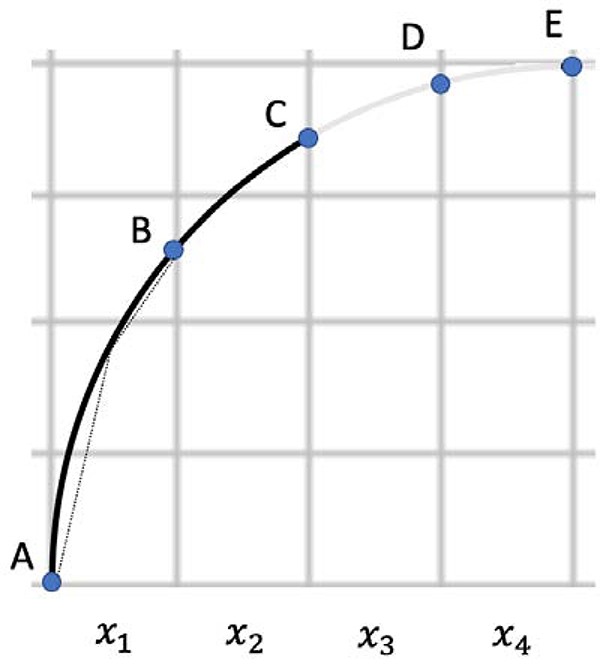

Figure 4 serves to illustrate the difference between voxel counting and surface area estimation approaches for assessing fissure completeness. In this 2D schematic simplification, the solid arc (from A to C) represents fissure, and the solid arc together with the shaded arc segment (A to E) represents the entirety of a border between adjacent lobes. Using the voxel (in this case, pixel) counting approach, the level of completeness is 50% (x1 and x2 corresponding to fissure; x1, x2, x3, and x4 corresponding to lobe boundary). However, this clearly underestimates the level of fissure completeness in this example, with the arc length from A to C clearly accounting for more than 50% of the arc length from A to E. The dashed line segments between A and B are analogous to the triangle mesh surface approximating scheme described above: piecewise linear line segments (surface patches) that approximate nonlinear arcs (surfaces). (To avoid clutter, we did not draw approximating line segments for the other arc segments).

Figure 4.

2D schematic example of a “fissure” (solid arc from A to C) and “lobe boundary” (arc from A to E). Dashed line segments between A and B are analogous to the surface area approximating scheme described in the text.

2.4. Fissure Representation

Having described the procedure for lobe boundary area estimation, we now describe our use of particles sampling (Kindlmann et al., 2009) as a convenient way to represent fissure detections. We have described the use of particles sampling for fissure detection in our previous work (Ross et al., 2013). Briefly, as fissure surfaces between lung lobes have higher radio-opacity than the lobes themselves, the fissure can be isolated as a ridge surface, defined as the loci of points where the gradient of the image is orthogonal to the minor eigenvector of the Hessian. The particles sampling algorithm repositions points according to an image feature strength term, in our case defined as the third eigenvalue of the Hessian, and a potential energy that is a function of the distance between neighboring particles. Upon convergence, the system achieves a dense and uniform feature sampling in physical space. Although we have previously deployed particles sampling directly on the CT image, particles can be deployed on other ridge-surface representations that capture fissure detections, such as probability and binary detection images. In the case of probability or binary detection images, smoothing (Gaussian blurring) is required as a pre-processing operation prior to particles sampling itself (see supplemental material for further details).

The particle system detects locally planar structures; these include fissures as well as supernumerary (accessory) fissures and non-fissure (noise) structures. Before the completeness of a particular fissure can be assessed, the fissure detections must be classified according to the most probable fissures they represent, and noise particles must be removed. Although accessory fissures are not uncommon (Aziz et al., 2004), they are typically not considered important in clinical practice. Hence, we restrict our analysis to the three main fissures: left oblique, right oblique, and right horizontal. We have previously described a lung lobe segmentation approach in which fissure particles are classified using Fischer’s linear discriminant (Ross et al., 2013). The classifier considers two parameters when assessing the ith particle: its shortest distance to the lobe boundary, di, and its orientation, θi, with respect the lobe boundary’s normal vector. Intuitively, a particle that is close to the fit surface and has a minor eigenvector roughly parallel to the local surface normal is more likely to be a fissure particle. The two-dimensional feature vector composed of the distance to the lobe surface and the particle’s angle with respect to the surface normal is then projected onto a one-dimensional subspace such that the means of the two classes (noise particles and fissure particles) are well separated while also minimizing the variance of each of the classes. The projection vector and optimal threshold in the one-dimensional subspace were empirically determined as described in (Ross et al., 2013). In the case of the right lung where we need to distinguish between the horizontal and oblique fissures, the distance and angle vectors are computed with respect to both lobe boundaries (the boundary separating the right middle lobe from the upper lobe, and the boundary separating the lower lobe from the other two lobes). If both of the one-dimensional projections are above the discriminant threshold, the one farthest above the threshold dictates the class assignment (oblique or horizontal). In our previous work, we described a shape model fitting stage that informed the Fisher linear discriminant classifier (Ross et al., 2013). Here we augment the classification tool to allow specification of a lung lobe label map. If specified, thin plate spline surfaces are derived from the set of voxels lying on the boundaries between lung lobes. Additionally, we provide an absolute distance parameter: a particle must be within the specified distance of the lobe boundary to be retained.

After the classification stage, we have particle points for each of the three main fissures. However, the particles exist as an unorganized point cloud, so we use Delaunay triangulation (Delaunay and others, 1934) to construct a mesh representation of the fissure surface that can be used for completeness assessment. Internally, we use the vtkDelaunay2D filter available in the Visualization Toolkit (Schroeder et al., 2006). Use of this filter identifies topological connectedness between the particle points in the axial (2D) plane. This filter exposes a parameter enabling the computation an alpha shape, a generalization of a convex hull which is a subset of the triangles in the Delaunay triangulation (Edelsbrunner and Mücke, 1994). By default, the alpha value is set to the inter-particle radius used to control the particle sampling density.

2.5. Fissure Completeness Estimation

During the lobe boundary surface area tally operation described in Section 2.3, we assess whether a lobe boundary voxel corresponds to a detected fissure by casting a ray from just below the voxel coordinate to just above it. If the ray intersects with the corresponding fissure mesh, we add the voxel’s surface area estimate to the fissure surface area tally. In general, we expect there to be slight discrepancies between the lobe boundary locations (defined using the segmentation input) and the fissure surface locations (defined using the fissure detection inputs). We therefore provide for a user-specified tolerance that allows detected fissure points to be slightly above or below the lobe boundary. The fraction of fissure completeness is then computed as the ratio of total fissure surface area divided by the corresponding total lobe boundary surface area. As an alternative to computing fissure completeness using estimated surface areas, we also provide the option to compute completeness using the ratio of total fissure voxels detected divided by the total number of boundary voxels detected as in (van Rikxoort et al., 2012).

3. SOFTWARE IMPLEMENTATION AND TESTING

As noted above, we have implemented the fissure completeness framework within the Chest Imaging Platform. A detailed description of each component is provided in the supplement. Additionally, we have implemented a nipype workflow (Gorgolewski et al., 2011) that orchestrates the various components, making it straightforward for a user to apply.

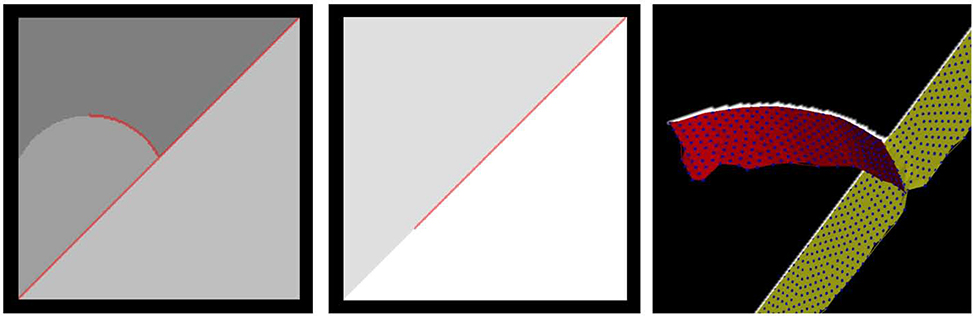

The Chest Imaging Platform uses ctest, a testing tool distributed as part of CMake, to manage the various tests that have been written to ensure Chest Imaging Platform code quality. We have added a test that runs the fissure completeness workflow on a synthetically generated image to ensure that the framework provides expected results. The synthetic image and resultant boundary-specific particles and derived mesh surfaces are shown in Figure 5. The test image is a 220 X 220 X 220 volume with left and right “lungs” represented as square regions in the sagittal plane. “Lobes” are further represented as sub-regions as shown in Figure 5. There is a corresponding “fissure” detection volume in which the right oblique fissure is represented as being complete, the right horizontal is half complete, and the left oblique is three-quarters complete. The test runs the nipype workflow on these synthetic data sets, generates completeness measures for all three boundaries, and compares to expected results. In practice, the test permits a small (1%) deviation from expected completeness scores given that the particles algorithm is stochastic in nature and will in general produce slightly different results on each execution.

Figure 5.

Synthetically generated image volume used in the workflow testing framework. Left and middle: sagittal slices of artificial (digitally generated) “lobes” and fissure detections (red overlay) with different levels of completeness. Right: 3D rendering of a fissure detection sagittal slice (white), particles (small blue discs), and fissure-specific mesh surfaces (right horizontal fissure surface in red and right oblique fissure surface in yellow).

4. EXPERIMENTS AND RESULTS

To demonstrate the proposed fissure completeness framework, we randomly selected 100 volumetric CT datasets from the COPDGene study (Regan et al., 2011), a multicenter investigation focused on examining the genetic and epidemiological basis of COPD and other smoking related lung diseases. The CT examinations were acquired at full inspiration on either GE scanners (LightSpeed 16 and LigthSpeed VCT) using the STANDARD reconstruction kernel or Siemens scanners (Sensation 64, Definition, DefinitionAS+, and Somaton) using the B31f reconstruction kernel. Slice thickness ranged from 0.625mm to 1.25 mm. Tube current was either 400mA or 440 mA, and tube voltage was 120 kV for all scans. In-plane pixel spacing ranged from 0.54mm to 0.85mm across all scans. All scans were acquired with subjects in the supine, head-first position.

An experienced chest radiologist visually inspected all cases and recorded the level of fissure completeness using a five-point scale: complete/near complete, mostly complete (approximately 75% complete), partially complete (approximately 50% complete), mostly incomplete (approximately 25% complete), absent/near absent. Fissure completeness for the cases used in this study is summarized in Table I.

Table 1.

Fissure completeness breakdown for the left oblique (LO), right oblique (RO), and the right horizontal (RH) fissures.

| Complete / Near Complete | Mostly complete | Partially complete | Mostly incomplete | Absent / near absent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LO | 65 | 27 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| RO | 47 | 45 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| RH | 23 | 23 | 25 | 19 | 10 |

We segmented lung lobes using the method described in (Ross et al., 2013) and available in the Chest Imaging Platform. Segmentation results were visually inspected on multiple sagittal slices using semi-transparent overlays as shown in Figure 1. Cases for which the automatic method failed were manually segmented using the interactive approach described in (Ross et al., 2009) and currently implemented in 3D Slicer (Fedorov et al., 2012).

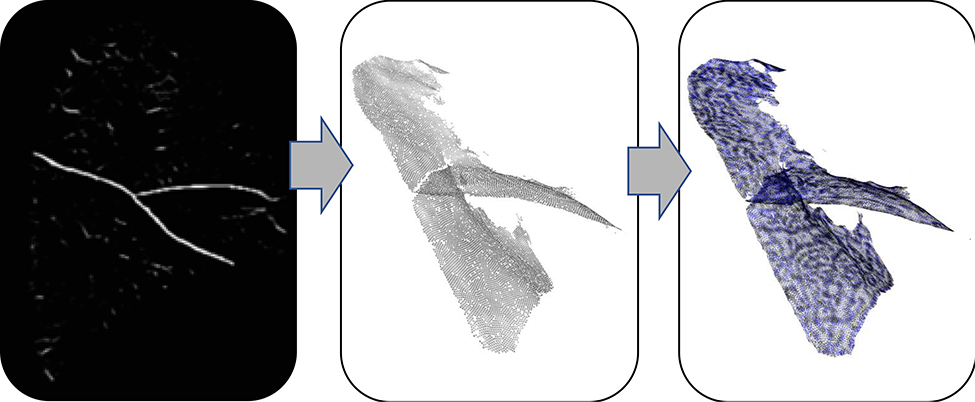

For fissure detection, we used a fissure probability image generated from a convolutional neural network (CNN), as described in (Nardelli et al., 2017). The CNN was trained on an 8-layer neural network with three convolutional layers which define high order local information of the image. Prior to particles deployment, the fissure probability image was preprocessed with a Gaussian blurring operation as noted in Section 2.4 and detailed in the supplemental material. Details of these operations are given in the supplement. Figure 6 shows the fissure detection representation workflow for these experiments.

Figure 6.

Fissure detection representation workflow. Left: input to particles ridge surface sampling (Gaussian-smoothed probability image derived from CNN feature enhancement). Middle: output of particles sampling operation. Right: wireframe mesh representation of surfaces derived from Delaunay triangulation of particles data.

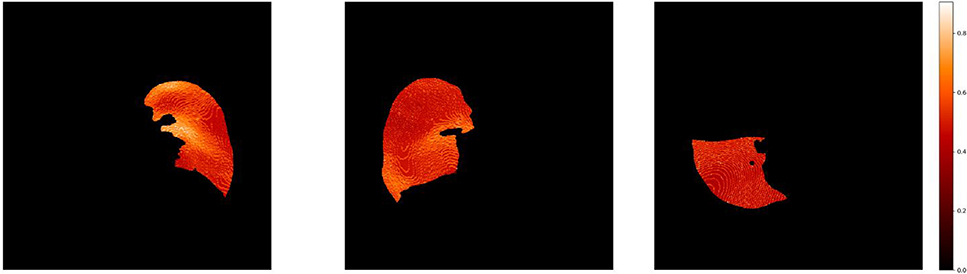

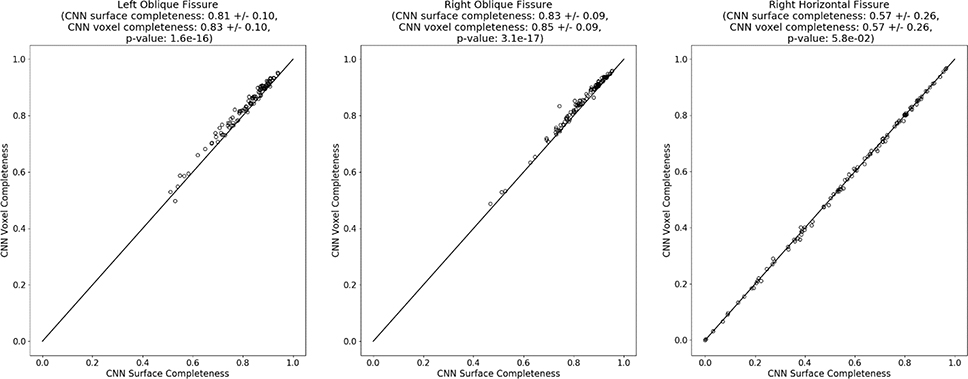

Figure 7 shows heatmaps representing estimated lobe boundary surface areas for a typical case. Variations in curvature across both the left oblique and right oblique surfaces can be seen, while comparatively less variation is seen across the right horizontal surface. We compared the proposed surface area estimation approach for computing fissure completeness to the voxel counting approach. Depending on the fissure detection locations relative to the lobe boundary undulations, the voxel counting approach could either underestimate or overestimate the degree of fissure completeness. To test the hypothesis that there would be a difference between these two approaches, we applied a two-sided Wilcoxson signed rank test. The results are summarized in Figure 8 and indicate a slight but statistically significant difference in completeness estimate in the oblique fissures, with the surface area estimation approach tending to be lower than the voxel counting ratio approach. No meaningful difference between the two approaches was observed for the right horizontal fissure.

Figure 7.

Heatmaps showing estimated surface areas for the left oblique (left), right oblique (center), and right horizontal (right) lobe boundaries for a typical case.

Figure 8.

Comparison of fissure completeness measures as assessed by particles sampling of a) estimation of surface areas (x-axis) and b) ratio of voxel counts (y-axis). In each panel, the line of identity is shown for reference.

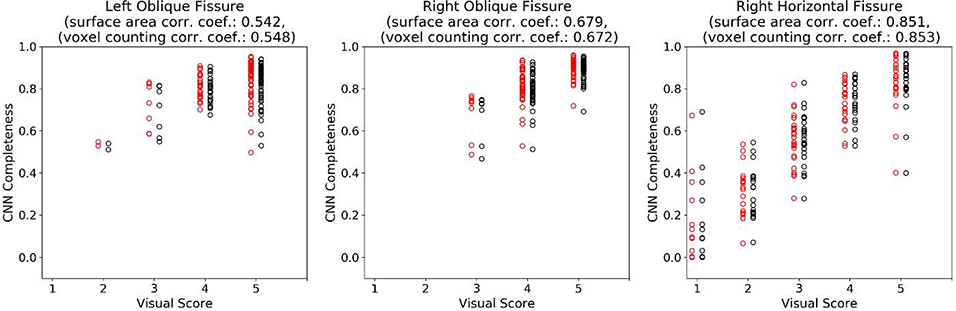

Finally, we treated the five-point visual score as interval data and assessed the relationship between the visual and quantitative scoring using correlation analysis. Additionally, differences in correlation coefficients between the surface area and voxel counting completeness approaches were compared (Diedenhofen and Musch, 2015). Figure 9 summarizes the results and shows there to be a moderate correlation between visual and quantitative scores for the left and right oblique fissures and high correlation for the right horizontal fissure. Differences in correlation coefficients between surface area and voxel counting approaches were negligible and not statistically significant.

Figure 9.

Quantitative fissure completeness estimates vs. visual scoring. Red: completeness measures using voxel counting. Black: completeness measures using surface area estimation. Visual scores are coded as: 1=absent/near absent, 2=mostly incomplete, 3=partially complete, 4=mostly complete, 5=complete/near complete.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

We have proposed an open source framework for pulmonary fissure completeness assessment. The code described is readily available on github as part of the Chest Imaging Platform (see supplement for details). The framework is designed to flexibly accommodate various lung lobe segmentation and fissure detection representations.

We have also proposed a surface area approximation intended to yield more precise estimates of fissure completeness. We demonstrated that by using this approach, completeness estimates tend to be lower for the oblique fissures compared to a ratio of voxel counts strategy. However, no meaningful difference in the two approaches was observed for the right horizontal fissure. Furthermore, we saw no significant difference between the two approaches when compared to visual reads on a five-point scale. Although we anticipated that completeness measures using the proposed surface area estimation scheme would produce a stronger correlation with visual scores, our results do not bear this out. Nevertheless, the subtle differences observed between the two approaches (summarized in Figure 8) may prove to be meaningful in an expanded study – perhaps using other fissure detections or enhancements as inputs. Furthermore, these experiments corroborate the voxel counting approach as a sensible strategy compared to (arguably) a more elaborate technique, and both approaches are provided to an end user to choose between.

Our framework requires as input a lung lobe segmentation image that identifies lobe boundaries with sufficient accuracy. The Chest Imaging Platform provides an automatic lung lobe segmentation routine (Ross, 2013); other lobe segmentations can be used as well. We have described tools that facilitate the quality control process and that can be used to interactively recover segmentation failures with minimal user input in a short amount of time (within a few minutes). In a previous study, we found that interactive user time was approximately 6–7 minutes on average in order to achieve satisfactory lobe segmentations (Ross et al., 2009). Furthermore, the framework requires fissure detections sensitive enough to capture the full extent of the fissure surface. We have previously described particles-based sampling directly on the CT image; here we deployed particles sampling on feature strength images derived from CNNs. Although CNNs have been shown to improve the accuracy of fissure detections over particles sampling directly deployed on CT (Nardelli et al., 2017), we acknowledge that further improvements are possible, e.g. using schemes that contextualize fissure features within the overall lung field (Gerard et al., 2018). Our framework is designed specifically to accommodate such ongoing innovations.

Significant attention has been given (and continues to be given) to both fissure detection and pulmonary lobe segmentation, but comparatively less attention has been given to fissure completeness estimation. We view this as an unmet need. By providing a flexible framework that incorporates lung lobe segmentations and fissure detections and enhancements in various formats, we enable investigators who may already have fissure detections, lobe segmentations, or the algorithms that produce them, but who may nonetheless not have a ready means to quantitatively evaluate fissure completeness, limiting their ability to conduct studies related to this biomarker. By providing this capability to the community, we hope to have a significant impact on the field of COPD and emphysema research and therapy development.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Fissure incompleteness has been shown to associate with emphysema treatment outcomes.

Methods for pulmonary fissure detection and lung lobe segmentation continue to be developed.

We present and open-source software framework for fissure completeness assessment.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors do not hold any conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Aziz A, Ashizawa K, Nagaoki K, Hayashi K, 2004. High resolution CT anatomy of the pulmonary fissures. J. Thorac. Imaging 19, 186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein FL, 1989. Principal warps: Thin-plate splines and the decomposition of deformations. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 11, 567–585. [Google Scholar]

- Delaunay B, others, 1934. Sur la sphere vide. Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR, Otd. Mat. i Estestv. Nauk 7, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Diedenhofen B, Musch J, 2015. cocor: A comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PLoS One 10, e0121945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doel T, Gavaghan DJ, Grau V, 2015. Review of automatic pulmonary lobe segmentation methods from CT. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 40, 13–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelsbrunner H, Mücke EP, 1994. Three-dimensional alpha shapes. ACM Trans. Graph. 13, 43–72. 10.1145/174462.156635 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalphaty-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robbin J-C, Pujol S, Bauer C, Jennings D, Fennessy F, Sonka M, Buatti J, Aylward S, Miller JV, Pieper S, Kikinis R, 2012. 3D Slicer as an Image Computing Platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn. Reson. Imaging 30, 1323–1341. 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001.3D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Mannino DM, Wheaton AG, Giles WH, Presley-Cantrell L, Croft JB, 2013. Trends in the prevalence of obstructive and restrictive lung function among adults in the United States: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination surveys from 1988–1994 to 2007–2010. Chest 143, 1395–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard SE, Patton TJ, Christensen GE, Bayouth JE, Reinhardt JM, 2018. FissureNet: A deep learning approach for pulmonary fissure detection in CT images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgolewski K, Burns CD, Madison C, Clark D, Halchenko YO, Waskom ML, Ghosh SS, 2011. Nipype: a flexible, lightweight and extensible neuroimaging data processing framework in python. Front. Neuroinform. 5, 13 10.3389/fninf.2011.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg JC, 2004. Pathophysiology of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 364, 709–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindlmann GL, Estépar RSJ, Smith SM, Westin C-F, 2009. Sampling and visualizing creases with scale-space particles. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klooster K, ten Hacken NHT, Hartman JE, Kerstjens HAM, van Rikxoort EM, Slebos D-J, 2015. Endobronchial valves for emphysema without interlobar collateral ventilation. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 2325–2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigkam-Santos M, Puderbach M, Gompelmann D, Eberhardt R, Herth F, Kauczor H-U, Heussel CP, 2012. Incomplete fissures in severe emphysematous patients evaluated with MDCT: incidence and interobserver agreement among radiologists and pneumologists. Eur. J. Radiol. 81, 4161–4166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Ward EM, Siegel RL, Jemal A, 2015. Temporal trends in mortality in the United States, 1969–2013. Jama 314, 1731–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardelli P, Ross JC, Estépar RSJ, 2017. CT image enhancement for feature detection and localization, Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). 10.1007/978-3-319-66185-8_26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu J, Fuhrman C, Durick J, Leader JK, Klym A, Sciurba FC, Gur D, 2010. Computerized assessment of pulmonary fissure integrity using high resolution CT. Med. Phys. 37, 4661–4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Make B, Lynch DA, Beaty TH, Curran-Everett D, Silverman EK, Crapo JD, 2011. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 7, 32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JC, Estépar RSJ, D\’\iaz A, Westin C-F., Kikinis R,,., Silverman EK, Washko GR, 2009. Lung extraction, lobe segmentation and hierarchical region assessment for quantitative analysis on high resolution computed tomography images, in: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention pp. 690–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JC, Kindlmann GL, Okajima Y, Hatabu H, Díaz AA, Silverman EK, Washko GR, Dy J, Estépar RSJ, 2013. Pulmonary lobe segmentation based on ridge surface sampling and shape model fitting. Med. Phys. 40 10.1118/1.4828782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Jose R, Ross JC, Harmouche R, Onieva J, Diaz AA, Washko GR. Chest imaging platform: an open-source library and workstation for quantitative chest imaging. In C66 Lung Imaging II: New Probes and Emerging Technologies 2015. May (pp. A4975–A4975). American Thoracic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder Will; Martin Ken; Lorensen Bill (2006), The Visualization Toolkit (4th ed.), Kitware, ISBN 978–1-930934–19-1 [Google Scholar]

- Sciurba FC, Ernst A, Herth FJ, Strange C, Criner GJ, Marquette CH, Kovitz KL, Chiacchierini RP, Goldin J, McLennan G. A randomized study of endobronchial valves for advanced emphysema. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010. September 23;363(13):1233–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rikxoort EM, Goldin JG, Galperin-Aizenberg M, Abtin F, Kim HJ, Lu P, van Ginneken B, Shaw G, Brown MS, 2012. A method for the automatic quantification of the completeness of pulmonary fissures: evaluation in a database of subjects with severe emphysema. Eur. Radiol. 22, 302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rikxoort EM, Prokop M, de Hoop B, Viergever MA, Pluim JPW, van Ginneken B, 2010. Automatic segmentation of pulmonary lobes robust against incomplete fissures. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 29, 1286–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.