Introduction

Perinatal depression is a major public health burden with intergenerational effects. Incidence of perinatal depression is higher in low-income and minority populations and less likely to be diagnosed or treated (Banti et al.,2011; Rich-Edwards et al.,2006). Perinatal depression is associated with alterations in infant emotional response and subsequent behavioral and cognitive problems later in childhood and adolescence (Goodman et al., 2011; Netsi et al., 2018). These effects, evident in early infancy include increased negative affect (Dawson et al., 2003; Murray et al., 1996), less secure attachment relationships (van Ijzendoorn et al., 1992), and difficulties with emotion regulation (Dawson et al., 1997). Further, decreased maternal sensitivity to infant cues and increased intrusiveness may mediate the association between perinatal depression and adverse child outcomes (Lovejoy et al., 2000). Thus, a robust, integrated depression treatment that targets parenting skills and the parent-infant dyad in addition to maternal depressive symptoms is needed to fully address the intergenerational risk of perinatal depression (Landry et al., 2008; Milgrom et al., 2015; O’Hara, 2009). This is an ideal time in which to engage mental health services as women are more likely to be accessing healthcare.

While some studies suggest postpartum depression treatment benefits mother-infant interactions, others have failed to find such benefits (Clark et al., 2003; Forman et al., 2007; Murray et al., 2003; Tsivos et al., 2015). Several decades of research have shown mother-infant interventions to be effective in improving the quality of mother-infant relationships and child outcomes (Barlow et al., 2015; Deans, 2018). More recently, interventions have been developed to improve maternal depressive symptoms as well as the mother-infant relationship. For example, Clark and colleagues developed a multicomponent group intervention (Clark et al., 2008) and Beeberand colleagues added parenting enhancements to interpersonal psychotherapy delivered in-home by advanced practice nurses (Beeber et al., 2013, 2007). However, these treatments have not been initiated in the potentially critical interval of pregnancy/immediate postpartum period, and applicability to newborns or young infants is unknown. Few studies have examined the effectiveness of psychotherapy to treat antenatal depression and even fewer have measured infant outcomes (Letourneau et al., 2017).

To begin to address these gaps in the literature, we developed a novel psychotherapeutic intervention, Interpersonal Psychotherapy for the Mother-Infant Dyad (IPT-Dyad) which consists of an evidence-based intervention for depression during pregnancy, brief-IPT as develop by Grote and colleagues (2004), followed by enhanced IPT treatment that focuses on the maternal-infant relationship and maternal attunement postpartum. We chose to develop IPT-Dyad rather than use an existing evidence based parenting intervention (i.e. Child Parent Psychotherapy) for several reasons: 1) to seamlessly maintain the interpersonal focus of IPT started during pregnancy, 2) to incorporate the mother-infant relationship into the focus of treatment, 3) to retain the relatively brief structure of the intervention, and 4) to continue to be responsive to the needs of low-income mothers. Our goal was that making enhancements specific to the maternal-infant relationship and maternal attunement to the infant would enhance the efficacy of treatment for perinatal depression and prevent intergenerational transmission.

We have previously reported results from an open-label case series in which we describe the IPT-Dyad intervention development process (Lenze et al., 2015). Lenze and Potts (2017) describes the first phase of a pilot randomized controlled trial of IPT-DYAD versus enhanced treatment as usual (ETAU) in which we replicate the brief-IPT model. The current study is the second phase of that trial in which we implemented the dyadic postpartum intervention. We hypothesized that IPT-Dyad would be feasible to deliver and acceptable to participants, and that relative to ETAU, IPT-Dyad would show greater improvements in depressive symptoms, decreased parenting stress, and increased maternal sensitivity. This report describes feasibility (evidenced by recruitment and adherence/retention), acceptability (satisfaction and session attendance), and preliminary treatment outcomes for mom and baby. We highlight the challenges we encountered during this trial and suggest future directions to modify and enhance the intervention.

Methods

Study procedures were approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and are in compliance with Declaration of Helsinki. Participants provided written consent prior to participation in the study. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health. Data were collected between 2012 and 2016.

Participants

Pregnant women between 12-30 weeks gestation, aged 18 and older, English speaking, and scoring ≥10 on the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDS) were potentially eligible. Women were recruited using flyers posted in an urban OB-Gyn clinic, OB-Gyn clinic staff referral, and referrals from local community social service agencies. Study staff administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV; First et al., 1995) to determine psychiatric diagnoses. Participants were included if they met criteria for Major Depressive Disorder, Dysthymia, or Depression NOS. Exclusion criteria were psychotic disorders, suicidal ideation to preclude safety of outpatient treatment, acute mania, substance abuse in the past 3 months (with the exception of marijuana), and medically high-risk pregnancy.

Eligible participants were randomized by a statistician using a computer generated permuted block design to IPT-Dyad (n=21) or ETAU (n=21). The PI and study staff were blinded to the randomization grid and assignments were stored in opaque, sealed envelopes opened by participants after signing consent.

All mothers received a re-usable gift bag containing various baby care items. Participants were also remunerated for completing assessments at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months postpartum.

Interventions

IPT-Dyad

The intervention has been previously described (see Lenze et al., 2015). During pregnancy, we followed the brief-IPT model (Grote et al., 2004; Lenze and Potts, 2017; Swartz et al., 2014). This intervention consisted of an initial “engagement session” followed by eight sessions of IPT. Within two weeks after delivery, participants were contacted to schedule their first postpartum session (with the same therapist as during pregnancy). Sessions were structured to have a dual focus: on the mother’s IPT problem area and on the mother-infant dyad with the overall aim of creating a “virtuous cycle” between the two. During postpartum sessions, the therapist continued to assist with developing effective coping strategies for interpersonal problems and strengthening social networks (Frank et al., 1991). The new mother-infant relationship was nurtured using the same key IPT principles with the goal to foster a sense of mastery over the new role of mothering and reduce maternal insecurity and isolation.

Postpartum IPT sessions were grounded in attachment theory and included interactive activities designed to explore the developing mother-infant dyadic relationship in vivo. Developmental stages and parenting values were attended to throughout the course of therapy and interventions were modified appropriately. To bolster interpersonal communication skills between the mother-infant dyad, the therapist emphasized modeling and imitation and, when necessary, translated the infant’s emotional expressions so that they were understandable to the mother. Therapists also focused on the mental representations of the mother and child to understand the ongoing influence of past relationship experiences on the present parent-child relationship.

The first 4 postpartum sessions were scheduled weekly. The remaining sessions were delivered flexibly depending on the needs of the mother and the dyad. A developmental theme or skill was specified for each session (e.g. infant states, touch, gaze, language stimulation, play). The therapist used a combination of behavioral strategies to enhance maternal sensitivity and responsiveness, positive touch, and mutual regulation, with attachment based exploration of the maternal-infant relationship. Handouts were given to the mother demonstrating developmentally appropriate games or activities to practice between sessions.

Postpartum sessions took place at the location of the participant’s choice (in-home, in clinic, or other community location). We provided bus passes as needed. We also provided participants with 15 diapers at each session attended. The goal was to complete 10 sessions in the first year postpartum. Patients completed more or less; however, depending on individual therapeutic needs as informed by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001) and Parent Infant Relationship-Global Assessment Scale (ZERO TO THREE, 2005). Patients desiring additional treatment at the end of the study were provided with referrals.

The intervention was delivered by a clinical psychologist (SL) or one of two master’s level licensed professional counselors (JR and MAP). All sessions were video-taped and reviewed during weekly team meetings (including SL, JL, and JR or MAP) and individual supervision sessions with the PI. We utilized these weekly meetings to ensure fidelity to the overall IPT-Dyad model. The IPT Adherence and Quality scale (Stuart, 2011) was also used as a guide to fidelity to the IPT model when reviewing sessions.

ETAU

During the postpartum phase of the study, participants were contacted bi-weekly for the first 3 months postpartum and then monthly up to 9 months postpartum to complete brief mood and anxiety symptom questionnaires. Participants were given 15 diapers for each telephone questionnaire session completed. Mothers were encouraged to engage in mental health services as needed and were assisted with obtaining community providers.

Measures

Treatment feasibility, acceptability, and clinical outcomes were measured at baseline, 37-39 weeks gestation (reported previously), and at 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months postpartum in both IPT-Dyad and ETAU groups unless otherwise indicated below.

Acceptability of the intervention was measured using the 8-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ; Clifford and Greenfield, 1999). Items are rated on a one to four scale with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction. Session attendance of greater than or equal to 8 sessions and drop-out rates of less than 20 percent were defined a priori as indicators of acceptability. Feasibility was indicated by meeting recruitment goals, session attendance and adherence to study protocols.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EDS; Cox and Holden, 2003) was the primary clinical outcome measure. It is a 10-item self-reported rating scale that has demonstrated acceptable reliability, validity and sensitivity to symptom change over time. The Brief State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Berg et al., 1998) was used to assess changes in anxiety symptoms over time. This scale consisted of 6-items with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety.

The self-reported Social Support Questionnaire – Revised (Sarason et al., 1987) was used to measure perceived social support satisfaction at 6 and 12 months postpartum. The questionnaire consists of 12 items; higher scores indicated greater satisfaction. We used the Experiences in Close relationships -Revised (ECR-R; Fraley et al., 2000) to measure adult attachment relationships at baseline and at 12 months postpartum. Scores are reported on 2 subscales, Avoidance and Anxiety. We measured parenting stress using the Parenting Stress Index (Abidin, 1990) 120-item version at 6 and 12 months postpartum. This age-normed, self-report measure provides an indication of parenting stress due to parental factors, child factors, and life stress.

The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA; Carter and Briggs-Gowan, 1999) was used to measure infant social and emotional development at 9 and 12 months postpartum. Scores were obtained on 4 domains including externalizing, internalizing, dysregulation and competence. We assessed infant temperament using the Infant Behavior Questionnaire -Revised Very Short Form (Gartstein and Rothbart, 2003) 37-item version at 6 and 12 months postpartum.

The Coding Interactive Behaviors (Feldman 1998, unpublished manual) manual was used to objectively rate mother-infant interactions during a semi-structured task. Mothers were instructed to “interact with your baby as you normally would”. Developmentally appropriate toys were provided by the research team. Forty-three subscales (depending on age of the infant) were rated on a 5-point scale (1= minimal behavior observed, 5=maximal behavior observed). Subscale scores were combined to create construct domains: parent sensitivity, parent intrusiveness, child social involvement, child withdrawal, parent limit setting (9 & 12 months), child compliance (12 months), dyadic reciprocity, and dyadic negative states. Inter-rater reliability was acceptable: 86% at 3 months, 93% at 6 months, 91% at 9 months, 88% at 12 months.

Data Analysis

Because the study’s recruitment goal (n=40) was not designed to be statistically powered to detect between group differences, and the attrition rates were relatively high over time, statistical comparisons between groups were not conducted (Kraemeret al., 2006). To test for within group differences over time we utilized linear mixed models, which are less sensitive to missing data time-points than repeated measures ANOVA. We used SAS Proc Mixed (version 9.4) with unstructured, repeated, and Kenward-Rogers specifications for the outcome measures that were collected at four or more time-points. Following intent to treat principles, we included all randomized participants in the models.

Results

Participants were on average 26 years of age, African American (n=33; 78.5 %), single (n=31; 73.5%), with less than college education (n=36; 85%) (Lenze and Potts, 2017). Eighty percent of participants (n=33) reported incomes at or below federal poverty rates (defined by the U.S. Census Bureau 2014 poverty thresholds that include income and household composition); a majority of the sample reported incomes less than $1000 per month supporting, on average, 3 people in the household. Several participants were homeless living in shelters or had relatively transient/unstable housing. Most reported receiving some form of public assistance including federal food subsidies (n=32; 76%) and Medicaid (n=30; 71%). Half of the participants met DSM-IV criteria for Posttraumatic stress disorder. Other anxiety disorders and lifetime use of cannabis were also commonly reported. There were no significant differences between IPT-Dyad and ETAU on demographics variables at baseline (Lenze and Potts, 2017).

During the postpartum period, five (26%) women in the IPT-Dyad and seven (33%) in the ETAU reported taking antidepressant medications. Eleven (58%) women in ETAU reported receiving counseling (duration and type of counseling were not able to be assessed); including four (21%) women who received both medications and counseling. Approximately half of participants in each group reported receiving some type of social service (i.e. nurse home visits, food pantry, agency support).

Feasibility and Acceptability

Participant satisfaction: Scores on the CSQ are included in Table 1. Session attendance: The average number of IPT-Dyad sessions completed postpartum was eight (range 0 to 24). Nine (43%) women completed eight or more sessions. Six (29%) did not attend more than two sessions.

Table 1.

Maternal and infant outcomes from baseline to twelve months postpartum.

| IFT-Dyad | ETAU | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = | Baseline 21 | 3 m post-partum 14 | 6 m post-partum 15 | 9 m post-partum 14 | 12 m post-partum 15 | Baseline 21 | 3 m post-partum 16 | 6 m post-partum 14 | 9 m post-partum 12 | 12 m post-partum 13 | |

| Measure | Mean (SD) | ||||||||||

| Client satisfaction questionnaire (total) | 29.2 (2.3) | 30.5 (2.4) | 30.3 (2.6) | 29.3 (3.4) | 28.2 (3.8) | 27.2 (3.9) | 28.5 (2.5) | 26.8 (4.4) | |||

| Edinburgh depression scale (total) | 17.8 (3.7) | 11.0 (6.1) | 9.5 (2.9) | 10.6 (5.9) | 10.8 (4.0) | 17.9 (4.6) | 10.1 (6.8) | 9.4 (5.8) | 9.4 (4.7) | 8.8 (4.9) | |

| Brief state-trait anxiety inventory (total) | 15.6 (4.1) | 12.3 (4.6) | 11.8 (3.2) | 12.3 (3.7) | 13.8 (3.9) | 15.0 (4.2) | 12.4 (4.6) | 12.5 (4.8) | 11.4 (3.3) | 11.4 (4.8) | |

| Social support questionnaire (satisfaction) | 28.4 (6.5) | 31.4 (6.0) | 30.5 (6.1) | 28.2 (6.4) | 30.8 (5.6) | 31.3 (5.6) | |||||

| Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised | |||||||||||

| Avoidance | 4.5 (1.0) | 4.4 (1.1) | 4.7 (0.9) | 4.5 (0.9) | |||||||

| Anxiety | 4.1 (1.2) | 3.8 (1.0) | 4.4 (0.7) | 3.6 (1.3) | |||||||

| Parenting stress inventory | |||||||||||

| Parent | 130.7 (35) | 140 (29) | 142.1 (28) | 136.4 (23) | |||||||

| Child | 105.5 (25.0) | 106.9 (18) | 105.4 (24) | 110.8 (23) | |||||||

| Total | 236.2 (56) | 246.9 (37) | 247.4 (45) | 247.2 (39) | |||||||

| Infant-toddler social emotional assessment (T-scores) | |||||||||||

| Externalizing | 49.23 (11.42) | 54.13 (13.85) | 52.82 (11.41) | 57.36 (7.27) | |||||||

| Internalizing | 45.9 (9.9) | 55.1 (8.6) | 46.4 (6.2) | 54.2 (9.0) | |||||||

| Dysregulation | 47.4 (11.0) | 51.7 (12.0) | 49.9 (20.0) | 51.0 (14.0) | |||||||

| Competence | 33.3 (10.26) | 42.53 (7.32) | 36.45 (9.71) | 47.36 (9.41) | |||||||

| Infant behavior questionnaire revised (very short form) | |||||||||||

| Surgency | 5.6 (0.8) | 5.9 (0.5) | 5.9 (0.6) | 5.9 (0.6) | |||||||

| Affect | 4.5 (0.8) | 4.8 (0.8) | 4.6 (1.3) | 4.7 (1.0) | |||||||

| Control | 5.9 (0.6) | 5.6 (0.7) | 5.6 (0.6) | 5.1 (1.5) | |||||||

| Coding Interactive Behaviors | |||||||||||

| Parent Sensitivity | 3.44 (0.63) | 3.01 (0.67) | 2.90 (0.63) | 2.85 (0.71) | 3.49 (0.86) | 3.28 (0.55) | 3.02 (0.87) | 3.04 (0.96) | |||

| Parent Intrusiveness | 1.62 (0.66) | ** | 1.63 (0.30) | ** | 1.87 (0.93) | ** | 1.80 (0.39) | ** | |||

| Limit Setting | n/a | n/a | 3.58 (0.78) | 3.71 (0.77) | n/a | n/a | 3.79 (1.07) | 3.36 (1.13) | |||

| Child Involvement | 2.22 (0.58) | 2.72 (0.79) | 2.77 (0.70) | 2.91 (0.51) | 2.43 (0.73) | 2.82 (0.77) | 2.72 (0.69) | 2.95 (0.79) | |||

| Dyadic Reciprocity | 3.36 (0.93) | 3.18 (1.01) | 3.31 (1.10) | 3.19 (0.95) | 3.26(1.30) | 3.47 (0.95) | 3.55 (2.80) | 3.14 (1.24) | |||

| Dyadic Negative States | 2.08 (0.96) | 1.92 (0.98) | ** | 2.00 (0.55) | 2.28 (1.23) | 1.77 (0.60) | ** | 2.06 (0.85) | |||

Domain construct did not meet standards for internal consistency.

Study Recruitment: Recruitment targets were exceeded by two participants, though recruitment did take several months longer than anticipated.

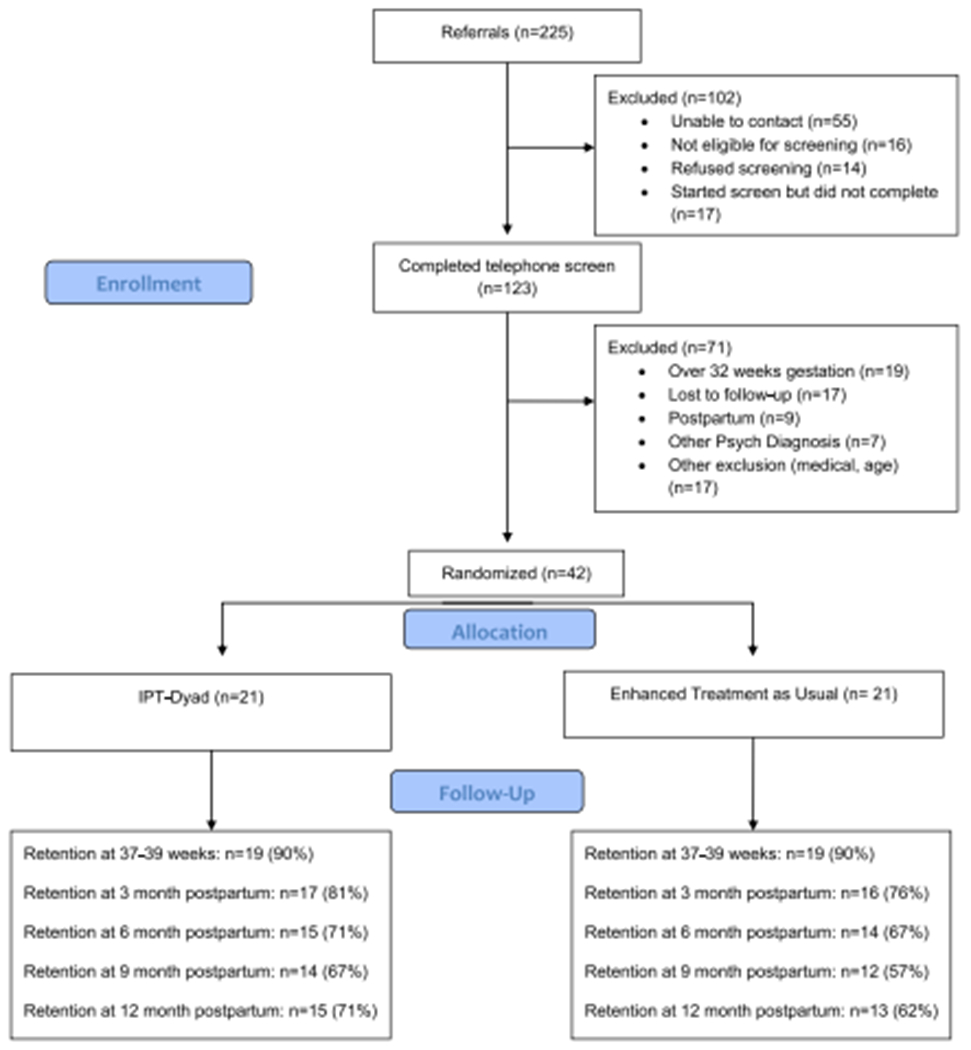

Study Retention: There were no differences between completers versus drop-outs on demographic characteristics, depression scores, or trauma history. Drop out was slightly higher in ETAU (see Figure 1). Although we met recruitment goals and achieved high satisfaction with the intervention, study retention was less than 80%, suggesting limitations to feasibility need to be addressed.

Figure 1:

Maternal Psychiatric Outcomes

Table 1 shows scores on outcome measures for each time point. As shown in the table, there were minimal differences between groups in terms of self-reported depression or anxiety. Scores are clinically and significantly decreased from baseline throughout the postpartum period in both groups (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Within group changes in maternal outcomes and parenting behaviors over time.

| Estimate | SE | DF | F | P-value | 95% CI (LL,UL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh depression scale | |||||||

| IPT-DYAD | −1.13 | 0.21 | 14.4 | 27.82 | 0.0001 | −1.59, −0.67 | |

| ETAU | −1.11 | 0.38 | 16.4 | 8.51 | 0.0099 | −1.92, −0.31 | |

| Brief State-trait Anxiety Inventory | |||||||

| IPT-DYAD | −0.51 | 0.20 | 15 | 6.16 | 0.03 | −0.94, −0.07 | |

| ETAU | −0.8 | 0.30 | 14.2 | 6.85 | 0.02 | −1.45, −0.14 | |

| Social support questionnaire (Satisfaction) | |||||||

| IPT-DYAD | 0.12 | 0.36 | 14.5 | 0.09 | 0.77 | −0.65, 0.87 | |

| ETAU | 0.38 | 0.20 | 12 | 3.55 | 0.08 | −0.06, 0.81 | |

| Coding interactive behaviors | |||||||

| Parent sensitivity | |||||||

| IPT-DYAD | −0.21 | 0.08 | 9.88 | 7.13 | 0.02 | −0.39, −0.04 | |

| ETAU | −0.17 | 0.09 | 18.1 | 4.06 | 0.06 | −0.36, 0.08 | |

| Child involvement | |||||||

| IPT-DYAD | 0.22 | 0.07 | 15.7 | 8.52 | 0.01 | .06, 0.38 | |

| ETAU | 0.21 | 0.08 | 13.9 | 7.12 | 0.02 | .04, 0.37 | |

| Dyadic reciprocity | |||||||

| IPT-DYAD | −0.02 | 0.11 | 14.6 | 0.04 | 0.84 | −0.27, 0.22 | |

| ETAU | −0.12 | 0.16 | 20 | 0.53 | 0.47 | −0.44, 0.21 | |

| Dyadic negative states | |||||||

| IPT-DYAD | data did not converge | ||||||

| ETAU | 0.03 | 0.15 | 6.02 | 0.04 | 0.85 | −0.33, 0.38 |

NB: Results from Edinburgh Depression Scale. Brief State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, and Social Support Questionnaire include Baseline. 37–39 weeks gestation, and at 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months postpartum data. Coding Interactive Behaviors includes data from 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months postpartum.

Maternal Interpersonal and Social Functioning

Also shown in Table 1, there were minimal differences between groups on measures of interpersonal or social functioning. Table 2 shows changes in social support satisfaction were not significantly different overtime in either the IPT-Dyad or ETAU group. At baseline, scores on the ECR-R indicate that a majority of participants would likely be classified as “insecurely attached” illustrating the high-risk nature of the sample. These scores were not expected to change overtime.

Parenting and Infant Outcomes

There were minimal differences between groups on parenting stress, infant temperament, or infant social/emotional development average scores as shown in Table 1.

Observational Mother-Infant Interactions

Cronbach alpha were calculated for construct domains to test internal consistency (data available upon request). Domain constructs with Cronbach alpha scores <.70 were not used. Similar to our findings on all the other measures, we observed little difference between groups on interactive ratings (see Table 1). The scores on the interactive domains in both groups indicate medium levels of dyadic interaction; similar to other studies of maternal depression (Feldman et al., 2009). Repeated measures analyses within groups (Table 2) indicate decreased maternal sensitivity over time in the IPT-Dyad group but not the ETAU group. Although this difference is statistically significant, it is unclear if this is clinically meaningful as the difference in scores is, on average, less than one point. It is possible that this could be associated with the small increases in depressive symptoms and parenting stress that were also observed; however, the sample size limits any firm conclusions. Child involvement increases over time in both groups as expected.

Discussion

In this pilot feasibility and acceptability study we developed and tested a novel psychotherapeutic intervention with the goal to treat maternal depressive symptoms while also enhancing the mother-infant relationship. We enrolled primarily low-income women experiencing high psychosocial adversity associated with living in poverty. There were numerous challenges and we learned valuable information that will inform subsequent refinement of the intervention moving forward.

Overall satisfaction with the intervention was high as indicated on a questionnaire. Substantial attrition occurred; however and there was varying levels of engagement with psychotherapy. Determining the optimal balance between working with the mother’s psychosocial and psychological needs and working with the needs of the mother-infant dyad was a primary challenge in this study. While therapists did their best to make referrals to community programs, managing the often overwhelming psychosocial needs (e.g. assistance finding emergency housing, securing food or diapers for the household) of the families often detracted from patient and therapist engagement in depression or dyadic treatment. Both the Grote et al (2015) and Beeber et al (2013) studies had more intensive case management and/or home visiting support available and also reported less attrition and more robust effects of treatment compared to our study. These experiences suggest that assistance managing the most extreme environmental and psychosocial stressors of poverty and/or managing the physiological dysregulation associated with poverty-related stress might better engage patients into therapy and thus improve intervention acceptability and feasibility (Wadsworth, 2012).

We experienced other challenges in structuring the postpartum sessions to facilitate mother-infant content. Future work would benefit from feedback from community members in order to better tailor this intervention to address their values and needs. Second, cell phones frequently distracted the mother’s attention from the baby (or therapist) and mothers often used their phones to distract their babies during play. Managing this type of distraction will continue to be a challenge given the ubiquity of smart phone usage. Third, the parenting content likely needed a higher degree of intensity in order to see positive change in this high-risk sample. Our experiences suggest we could use videos or other technology as a way to reinforce and promote practice outside of session. Handouts or app/text reminders of activities may be useful for future iterations. Finally, the number of sessions and time between sessions postpartum was unstructured. Results may have been different if we utilized a more structured schedule, as having that finite number of sessions maybe would have pressured both therapist and patient to stay on task (Swartz et al., 2014).

Limitations

Limitations include small sample size, especially after six-months postpartum. Our study retention was on par with or higher than other studies in similar populations (Beeber et al., 2013; Miranda J et al., 2003), but not as high as recent studies by Grote et al (2015, 2009). Even though this intervention was developed to overcome barriers, maintaining engagement in treatment was particularly difficult after three to six-months postpartum (Grote et al., 2004; Levy and O’Hara, 2010) when many women returned to work or had limited time to continue regular meetings or phone calls. Other women were lost to follow-up despite efforts to maintain contacts. Another limitation was our reliance on self-report ratings, particularly the EPDS. Blinded interviewer ratings may have produced a more accurate depression symptom assessment. The study therapists were all White and middle class, which may have contributed to attrition or rating bias. We attempted to facilitate a discussion about racial, social and other differences during the engagement interview, but this may not have eliminated potential bias or the sense of not having the life experience of the pregnant mother fully understood. We were also unable to measure parenting in non-depressed controls or assess attachment security. Therefore, it is unclear whether the parenting observed was “good enough” to promote infant attachment security (Woodhouse et al. 2019).

Conclusions

In sum, based on our experiences, we believe IPT-Dyad may be a promising intervention that could benefit from further modification to increase feasibility and effectiveness. Partnership with a home visiting or other social service or with a community health clinic could be a way to increase assistance with managing psychosocial needs while also improving longterm retention in the intervention. Further development of the intervention content and delivery with input from mothers with low-incomes would also greatly enhance the treatment. As more evidence points to the critical role sensitive parenting have on optimal brain development (Luby et al., 2013; Perry et al., 2019), early dyadic intervention to disrupt the devastating effects of perinatal depression on maternal and child outcomes continues to be a critical area for further research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abidin R, 1990. Parenting Stress Index - Manual, 3rd ed. Pediatric Psychology Press, Charlottesville, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Banti S, Mauri M, Oppo A, Borri C, Rambelli C, Ramacciotti D, Montagnani MS, Camilleri V, Cortopassi S, Rucci P, Cassano GB, 2011. From the third month of pregnancy to 1 year postpartum. Prevalence, incidence, recurrence, and new onset of depression. Results from the Perinatal Depression-Research & Screening Unit study. Comprehensive Psychiatry 52, 343–351. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Bennett C, Midgley N, Larkin SK, Wei Y, 2015. Parent-infant psychotherapy for improving parental and infant mental health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10.1002/14651858.CD010534.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeber LS, Cooper C, Van Noy BE, Schwartz TA, Blanchard HC, Canuso R, Robb K, Laudenbacher C, Emory SL, 2007. Flying Under the Radar: Engagement and Retention of Depressed Low-income Mothers in a Mental Health Intervention. Advances in Nursing Science 30, 221–234. 10.1097/01.ANS.0000286621.77139.f0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeber LS, Schwartz TA, Holditch-Davis D, Canuso R, Lewis V, Hall HW, 2013. Parenting Enhancement, Interpersonal Psychotherapy to Reduce Depression in Low-Income Mothers of Infants and Toddlers: A Randomized Trial. Nurs Res 62, 82–90. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31828324c2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C, Shapiro N, Chambless D, Ahrens A, 1998. Are emotions frightening? II: an analogue study of fear of emotion, interpersonal conflict, and panic onset. Behavior Research and Theory 36, 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, 1999. The infant-toddler social and emotional assessment (ITSEA). Yale University, Department of Psychology, New Haven, CT. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Tluczek A, Brown R, 2008. A mother-infant therapy group model for postpartum depression. Infant Mental Health Journal 29, 514–536. 10.1002/imhj.20189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Tluczek A, Wenzel A, 2003. Psychotherapy for Postpartum Depression: A Preliminary Report. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 73, 441–454. 10.1037/0002-9432.73.4.441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford C, Greenfield TK, 1999. The UCSF Client Satisfaction Scales: I. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8, in: The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment (2nd Ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, NJ, US, pp. 1333–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Holden J, 2003. Perinatal mental health: A guide to the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Royal College of Psychiatrists, London, England. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Ashman SB, Panagiotides H, Hessl D, Self J, Yamada E, Embry L, 2003. Preschool Outcomes of Children of Depressed Mothers: Role of Maternal Behavior, Contextual Risk, and Children’s Brain Activity. Child Development 74,1158–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Frey K, Panagiotides H, Osterling J, Hessl D, 1997. Infants of Depressed Mothers Exhibit Atypical Frontal Brain Activity A Replication and Extension of Previous Findings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 38, 179–186. https://doi.org/10.llll/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01852.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans CL, 2018. Maternal sensitivity, its relationship with child outcomes, and interventions that address it: a systematic literature review. Early Child Development and Care 0,1–24. 10.1080/03004430.2018.1465415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Granat A, Pariente C, Kanety H, Kuint J, Gilboa-Schechtman E, 2009. Maternal Depression and Anxiety Across the Postpartum Year and Infant Social Engagement, Fear Regulation, and Stress Reactivity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 48, 919–927. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b21651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J, 1995. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders. New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Forman DR, O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Larsen KE, Coy KC, 2007. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship. Development and Psychopathology 19, 585–602. 10.1017/S0954579407070289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA, 2000. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78, 350–365. 10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Wagner EF, McEachran AB, Comes C, 1991. Efficacy of Interpersonal Psychotherapy as a Maintenance Treatment of Recurrent Depression: Contributing Factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48, 1053–1059. 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360017002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK, 2003. Studying infant temperament via the Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behavior and Development 26, 64–86. 10.1016/S0163-6383(02)00169-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Long Q, Ji S, Brand SR, 2011. Deconstructing antenatal depression: What is it that matters for neonatal behavioral functioning? Infant Ment. Health J. 32, 339–361. 10.1002/imhj.20300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Bledsoe SE, Swartz HA, Frank E, 2004. Feasibility of Providing Culturally Relevant, Brief Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Antenatal Depression in an Obstetrics Clinic: A Pilot Study. Research on Social Work Practice 14, 397–407. 10.1177/1049731504265835 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Lohr MJ, Curran M, Galvin E, Carson K, 2015. Collaborative Care for Perinatal Depression in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Women: A Randomized Trial. Depress Anxiety 32, 821–834. 10.1002/da.22405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Mintz J, Noda A, Tinklenberg J, Yesavage JA, 2006. Caution Regarding the Use of Pilot Studies to Guide Power Calculations for Study Proposals. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63, 484–489. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, 2001. The PHQ-9. J GEN INTERN MED 16, 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR, Guttentag C, 2008. A responsive parenting intervention: The optimal timing across early childhood for impacting maternal behaviors and child outcomes. Developmental Psychology 44,1335–1353. 10.1037/a0013030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze SN, Potts MA, 2017. Brief Interpersonal Psychotherapy for depression during pregnancy in a low-income population: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders 210,151–157. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze SN, Rodgers J, Luby J, 2015. A pilot, exploratory report on dyadic interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Arch Womens Ment Health 18, 485–491. 10.1007/s00737-015-0503-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau NL, Dennis C-L, Cosic N, Linder J, 2017. The effect of perinatal depression treatment for mothers on parenting and child development: A systematic review. Depression and Anxiety 34, 928–966. 10.1002/da.22687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy LB, O’Hara MW, 2010. Psychotherapeutic interventions for depressed, low-income women: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review 30, 934–950. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G, 2000. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review 20, 561–592. 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby J, Belden A, Botteron K, Marrus N, Harms MP, Babb C, Nishino T, Barch D, 2013. The effects of poverty on childhood brain development: the mediating effect of caregiving and stressful life events. JAMA Pediatr 167,1135–1142. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom J, Holt C, Holt CJ, Ross J, Ericksen J, Gemmill AW, 2015. Feasibility study and pilot randomised trial of an antenatal depression treatment with infant follow-up. Arch Womens Ment Health 18, 717–730. 10.1007/s00737-015-0512-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, et al. , 2003. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290, 57–65. 10.1001/jama.290.l.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Cooper PJ, Wilson A, Romaniuk H, 2003. Controlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry 182, 420–427. 10.1192/bjp.182.5.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Fiori-Cowley A, Hooper R, Cooper P, 1996. The Impact of Postnatal Depression and Associated Adversity on Early Mother-Infant Interactions and Later Infant Outcome. Child Development 67, 2512–2526. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01871.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netsi E, Pearson RM, Murray L, Cooper P, Craske MG, Stein A, 2018. Association of Persistent and Severe Postnatal Depression With Child Outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry 75, 247–253. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, 2009. Postpartum depression: what we know. Journal of Clinical Psychology 65,1258–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry RE, Finegood ED, Braren SH, Dejoseph ML, Putrino DF, Wilson DA, Sullivan RM, Raver CC, Blair C, Investigators FLPK, 2019. Developing a neurobehavioral animal model of poverty: Drawing cross-species connections between environments of scarcity-adversity, parenting quality, and infant outcome. Development and Psychopathology 31, 399–418. 10.1017/S095457941800007X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman K, Abrams A, Harlow BL, McLaughlin TJ, Joffe H, Gillman MW, 2006. Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 60, 221–227. 10.1136/jech.2005.039370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR, 1987. A Brief Measure of Social Support: Practical and Theoretical Implications. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 4, 497–510. 10.1177/02654075870440Q7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart S, Stuart S, 2011. Interpersonal Psychotherapy Adherence and Quality Scale. https://iptinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/IPT-Qualitv-Adherence-Scale.pdf

- Swartz HA, Grote NK, Graham P, 2014. Brief Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT-B): Overview and Review of Evidence. American Journal of Psychotherapy 68, 443–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsivos Z-L, Calam R, Sanders MR, Wittkowski A, 2015. Interventions for postnatal depression assessing the mother-infant relationship and child developmental outcomes: a systematic review. International Journal of Women’s Health 7, 429–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ijzendoorn M, Goldberg S, Kroonenberg PM, Frenkel OJ, 1992. The relative effects of maternal and child problems on the quality of attachment: A meta-analysis of attachment in clinical samples. Child Development 63, 840–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, 2012. Working with Low-income Families: Lessons Learned from Basic and Applied Research on Coping with Poverty-related Stress. J Contemp Psychother 42, 17–25. 10.1007/sl0879-011-9192-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse SS, Scott JR, Hepworth AD, Cassidy J, 2019. Secure Base Provision: A New Approach to Examining Links Between Maternal Caregiving and Infant Attachment. Child Development 0. 10.1111/cdev.13224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZERO TO THREE, 2005. Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early childhood: Revised Edition (DC:0–3R). ZERO TO THREE Press, Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]