Abstract

Repeated exposure to drug-associated cues without reward (extinction) leads to refraining from drug seeking in rodents. We determined if refraining is associated with transient synaptic plasticity (t-SP) in nucleus accumbens shell (NAshell), akin to the t-SP measured in the NAcore during cue-induced reinstatement of drug seeking. Using whole cell patch electrophysiology, we found that medium spiny neurons (MSNs) in NAshell expressed increased ratio of AMPA to NMDA glutamate receptor currents during refraining, which normalized to baseline levels by the end of the two hour extinction session. Unlike t-SP observed in NAcore during reinstated drug seeking, neither dendrite spine head enlargement nor activation of matrix metalloproteases (MMP2/9) accompanied the increased AMPA:NMDA in NAshell during refraining. Refraining was also not associated with changes in paired pulse ratio, NMDA receptor current decay time, or AMPA receptor rectification index in NAshell MSNs. Our preliminary data in transgenic mice suggest that t-SP may increase D2-MSN inputs relative to D1-MSN inputs.

INTRODUCTION

Exposure therapies for treating substance use disorders (SUDs) are based on presenting stimuli associated with the drug experiences and the SUDs patients learning to refrain from drug seeking in the presence of those stimuli (1, 2). Although this form of therapy is modeled by extinction training in rodents that are repeatedly exposed to a drug-associated context without drug, a translational gap remains. Rodents undergoing extinction training refrain from future drug seeking far more consistently than humans with SUDs undergoing analogous training. Understanding the neurological underpinnings of refraining may provide insight towards bridging this gap.

Chronic exposure to cocaine produces a persistent potentiation of inputs to nucleus accumbens core (NAcore); enlarging dendritic spines and increasing AMPA:NMDA ratio in medium spiny neurons (MSNs) during withdrawal from short access cocaine regimens (3–5). These inputs are further potentiated in a rapid and transient manner during cue-induced drug seeking (6–8), an event that is termed transient synaptic potentiation (t-SP). Moreover, both cocaine cue-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking and t-SP in MSNs requires transiently activating matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) in the extracellular matrix (7). In contrast to cocaine-induced synaptic plasticity in NAcore that is consistently associated with promoting drug-seeking, cocaine-induced synaptic adaptations occurring in nucleus accumbens shell (NAshell) have been associated with promoting both refraining from drug use and drug seeking (9–14). Here we first asked whether MMP-2,9 activation and t-SP occurs in NAshell MSNs during refraining.

There are additional features of glutamatergic signaling that may also be altered during refraining. Extinction decreases pre-synaptic glutamate release in nucleus accumbens (15). The expression of calcium permeable (CP)-AMPARs in spines of NAshell MSNs contacted by infralimbic PFC after prolonged withdrawal oppose drug seeking (9). Finally, NMDA glutamate receptor (NMDAR) signaling in nucleus accumbens enhances extinction learning (16). We also examined how these features of glutamatergic signaling change during refraining from drug seeking in an extinguished context.

Two main classes of MSNs in the accumbens can be differentiated on the basis of expressing either D1 or D2 dopamine receptors (D1- and D2-MSNs) (17). While these cell types coordinate activity in contributing to adaptive behaviors, chemo- or optogenetic activation of D1-MSNs promotes drug seeking, while D2-MSNs are inhibitory (10, 18, 19). Accordingly, the t-SP associated with cue-induced cocaine seeking occurs in NAcore D1-, but not D2-MSNs (20). In a third experiment we undertook initial analysis to determine whether AMPA:NMDA during refraining was preferentially affected in D1- or D2-MSNs.

METHODS

Animals and behavior.

All experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Detailed methods are described elsewhere (8, 21). Rats (Sprague-Dawley, Charles River) and mice (BAC transgenic male and female, Vanderbilt University, DrD1a-tdTomato and Drd2-eGFP) were implanted with indwelling jugular venous catheters. After recovering from surgery, animals began cocaine self-administration in operant chambers equipped with two levers, a house light, cue light, and tone generator. The designated active lever delivered an infusion of cocaine (rats: 0.6 mg/kg/infusion, mice: 1 mg/kg/infusion) along with a compound cue (light + tone). Following each infusion, a 20 second time out was signaled by the loss of illumination of the house light, and active lever presses during the timeout were recorded but resulted in no programmed consequence. The designated inactive lever never triggered any programmed consequence. Mice undergoing extinction used nosepokes in place of levers throughout self-administration, extinction, and subsequent testing, as they were unable to maintain stable extinction responding when trained with lever presses. Following self-administration, animals either underwent 2-3 weeks of extinction training or remained abstinent in their home cages. During extinction, active and inactive lever presses were counted but did not result in any programmed consequence. During home cage abstinence, animals were handled and weighed daily in the testing room in order to control for non-specific components of extinction training. Following 2-3 weeks of daily extinction or abstinence, animals destined for baseline measurements of synaptic glutamate transmission were sacrificed without return to the operant chamber. Rodents destined for measurements of t-SP were returned to the operant chamber for a test of cocaine seeking prior to sacrifice. During this test, lever presses were counted but never triggered any programmed consequence. Rodents were sacrificed at the end of the reinstatement test for preparation of brain slices for electrophysiology.

Electrophysiology.

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine and decapitated. The brain was removed and transferred to ice cold aCSF containing (in mM) NaCl (126), KCl (2.5), MgCl2 (1.2), NaH2PO4 (1.4), CaCl2 (2.4), glucose (11), NaHCO3 (25), ascorbate (0.4), pyruvate (2). Coronal slices (220 μm) containing NA core were prepared on a Leica VT1200S vibratome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Ice cold cutting solution contained aCSF and kynurenic acid (5 mM) and D-AP5 (50 uM), bubbled continuously with carbogen gas (95% O2, 5% CO2). Recording “bath” solution contained aCSF and picrotoxin (0.1 mM) at physiological temperature (37 C). Slices were visualized using an Olympus Fixed Stage Upright Microscope, BX51WI (Tokyo, Japan). tdTomato (expressed in D1-MSNs) and eGFP (expressed in D2-MSNs) were visualized using 530nm and 460nm LEDs (Prizmatix, Southfield, MI, USA). Recording pipettes (1.9-2.4 MOhms) were filled with ice cold internal solution containing (in mM) CsMs (128), EGTA (1), HEPE-K (10), MgCl2 (1), NaCl (10), Mg-ATP (2), Na-GTP (0.3), QX-314-Cl (3); AMPAR rectification studies additionally contained spermine (0.1 mm). All recordings were amplified using an Axon/Molecular Devices Multiclamp Amplifier 700B (Sunnyvale, CA), digitized at 20 KHz and filtered at 2 KHz using Axograph Software. A bipolar stimulating electrode (FHC, Bowdoin, ME, USA) was used to evoke EPSCs between 200 and 450 pA. Following ten minutes of cell stabilization at −80 mV holding potential, a stable baseline was confirmed before proceeding and unstable cells discarded. EPSCs were evoked in a paired pulse protocol (50 msec inter-stimulus interval), and the PPR was calculated by dividing the average amplitude of the second EPSC by the first. Spontaneous EPSCs, detected no less than 10 seconds after the electrical stimulation, were analyzed with regard to their amplitude and frequency. Next, the holding potential was depolarized to +40mV and re-stabilized for an additional five minutes. Dual EPSCs were recorded prior to application of D-AP5, which enabled isolation of AMPAR EPSCs. NMDAR EPSCs were calculated by subtracting the average AMPAR EPSC from the average dual EPSC, and the AMPA:NMDA ratio was calculated by dividing the peak amplitudes of the AMPAR and NMDAR EPSCs. NMDAR decay time was calculated by dividing the AUC by peak amplitude. Coefficient of variation (CV) analyses were conducted by using peak AMPA amplitude (at −80 mV) and dual current amplitude (+40 mV, prior to d-AP5) at 50 msec. AMPAR rectification studies recorded only AMPAR currents (using d-AP5) at holding potentials of −80, −40, 0, 10, 20 40 mV. The reversal potential was calculated by fitting linear trends separately to the IV relationships of outward and inward currents, and the ratio of these slopes used to calculate rectification index. Changes in access resistance of >20% during the experiments resulted in removal of the cell from further analyses.

Dendritic spine morphology.

Rats were injected with ketamine/xylazine and transcardially perfused with PB and PfA. Coronal slices containing nucleus accumbens (200 um) were made on a HM 650V vibrating blade microtome (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Slices were diolistically labeled using a Helios System gene gun (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA) to deliver tungsten particles coated with the lipophilic carbocyanine dye DiI (ThermoFisher cat #D282). This protocol has also been extensively described by our lab (22). DiI labeled slices were imaged on a confocal microscope (Leica, Wetzler, Germany) using an oil immersion 63x objective with a numerical aperture of 1.4 using a HeNe 543 laser with a voxel size of 47x47x100 nm. Dendritic segments imaged were 75 μm long and chosen for maximal separation from other labeled neuropil; their proximal boundary was 75-150 μm from the soma, and thus included a mixture of secondary and tertiary dendrites. Spines were quantified using Imaris software (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland) and the resulting metrics were averaged within animal.

Zymography.

Dye-quenched gelatin (ThermoFisher cat # D12054) was microinjected into NA shell at a volume of 1.5 μl, 15 minutes prior to sacrifice (with or without re-exposure to the extinguished context). Coronal slices containing nucleus accumbens (50 um) were made on a HM 650V vibrating blade microtome. Slices were imaged on a confocal microscope using an 10x objective and an argon 488 laser. Only slices containing the injection tract were imaged. Integrated density of FITC fluorescence was quantified using ImageJ (Research Services Branch, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical comparisons were Student’s t-test, with the following exceptions: Repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze self-administration/extinction behavior and one way ANOVA was used to analyze AMPA:NMDA in NAshell during refraining. Bonferroni correction was used to adjust alpha for multiple comparisons. All data were analyzed using Prism, version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) and outliers were removed using the ROUT (=1) module of Prism (23).

RESULTS

Refraining from cocaine seeking is associated with increased AMPA:NMDA in NAshell.

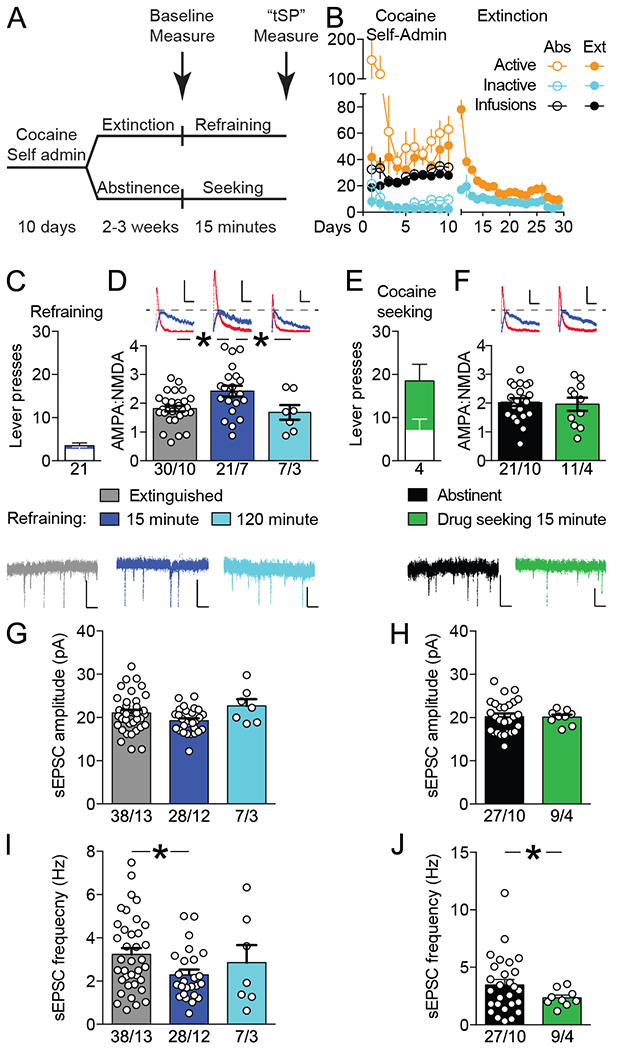

The NAshell is necessary for refraining from cocaine seeking after extinction (12, 24), but also mediates drug seeking in abstinent rats (withdrawn without extinction training) (10, 25). The first experiment sought to determine if t-SP was produced in NAshell during refraining behavior. Rats self-administered cocaine for 10 days, and were then divided into two groups that underwent 2-3 weeks of extinction training or homecage abstinence (Figure 1A,B). Subsequently, rats were either sacrificed for baseline measurements of glutamatergic transmission or returned to the operant chamber for an additional 15 minute behavioral test (Figure 1A). During this test, lever presses were recorded but did not result in any programmed consequence. Rats that had undergone extinction training and were re-exposed to the extinguished context refrained from cocaine seeking (Figure 1C), while abstinent rats re-exposed to the self-administration context engaged in cocaine seeking (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Refraining from cocaine seeking was associated with transient synaptic potentiation (t-SP) in nucleus accumbens shell (NAshell). A, Rats self-administered cocaine for 10 days and then underwent 2 to 3 weeks of extinction training or homecage abstinence. Subsequently, rats were either sacrificed (arrows) for baseline measurements of glutamatergic transmission or reexposed to the operant chamber. B, Cocaine self-administration and extinction behavior for abstinent (Abs) and extinguished (Ext) rats used in Figures 1–3, N = 104. C, Reexposure to the extinguished context elicited refraining behavior, ie, low active (blue bar) and inactive (white bar) lever pressing during 15 minutes. D, Relative to animals sacrificed at baseline, AMPA:NMDA ratio increased during 15 minutes of refraining and reverted to baseline after 2 hours. E, Reexposure to the cocaine-associated context abstinence resulted in cocaine seeking, ie, active (green bar) and inactive (white bar) lever presses. F, Context-induced cocaine seeking was not associated with increased AMPA:NMDA. G-H, Refraining and cocaine seeking were not associated with transient changes in spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current (sEPSC) amplitude. I-J, Reexposure to both extinguished and cocaine paired contexts was associated with decreased sEPSC frequency in NAshell. For all panels: Sample size is animals for panels C and E and cells/animals for panels D, F, and G-J. Scale bars are 20 pA × 50 milliseconds for panels D and F and 20 pA × 250 milliseconds for panels G-J. All data shown as mean ± SEM. *P < .05..

Refraining behavior was associated with increased AMPA:NMDA in NAshell. Ratios were elevated after 15 min of refraining relative to animals sacrificed at baseline, but reverted to baseline after an additional 1 hour and 45 minutes in the extinguished environment (F(2, 55)= 5.82, p= 0.005). Post-hoc tests showed increases from baseline at 15 minutes (p< 0.001), and decreases from 15 minutes to 120 minutes (p= 0.043), with no difference between baseline and 120 minutes (p= 0.892) (Figure 1D). NAshell also mediates contextual motivation to seek drugs (26). However, cocaine seeking by abstinent animals re-exposed to the self-administration context did not increase AMPA:NMDA in NAshell (t(30)= 0.29; p= 0.771, Figure 1F).

Spontaneous excitatory post-synaptic current (sEPSC) amplitude was unaffected by either refraining (Figure 1G: F(2, 70)= 3.063; p= 0.053; Bonferroni post-hoc p = .111 for refraining vs. baseline) or abstinent seeking (Figure 1H: t-test with Welch’s correction t(31)= 0.12; p= 0.908). However, sEPSC frequency was decreased both during refraining (Figure 1I: F(2, 66)= 2.594, p= 0.082; Bonferroni post-hoc p = 0.048 for refraining vs. baseline) and during abstinent cocaine seeking (Figure 1J: t-test with Welch’s correction t(34)= 2.08; p= 0.045). Overall, these results suggest that depression of spontaneous glutamate release onto NAshell MSNs occur during re-exposure to context regardless of whether that context is associated with extinction or self-administration alone. Similar results have been described for D1-MSNs in NAcore (27) and in nucleus accumbens when mice underwent extinction of conditioned place preference (15).

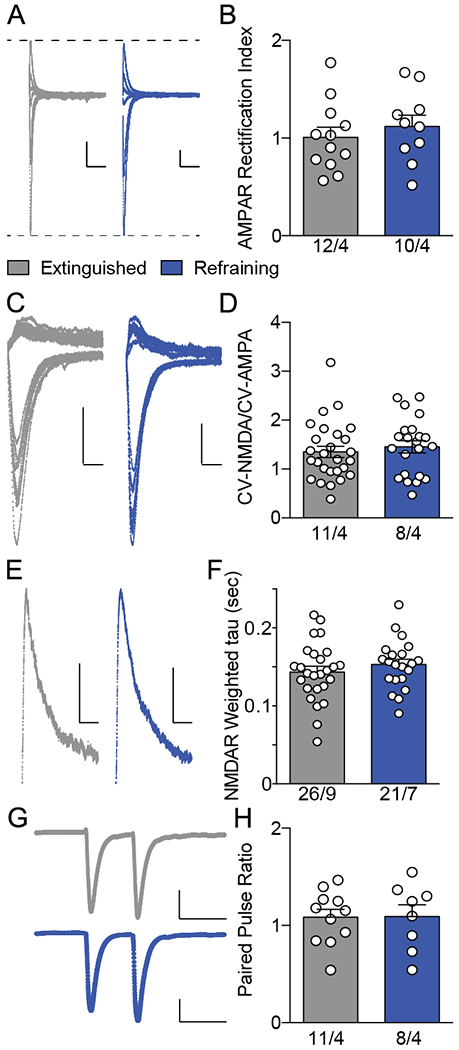

Refraining was not associated with other t-SP alterations of glutamatergic transmission.

AMPARs in NAshell differentially affect drug seeking behavior depending on subunit composition. Thus, GluA2-lacking calcium permeable (CP)-AMPARs in NAshell spines contacted by infralimbic PFC suppress cocaine seeking (9, 10), while GluA2 containing calcium impermeable (CI) AMPARs contacted by ventral hippocampal terminals in NAshell promote cocaine seeking (10). We hypothesized that CP-AMPAR insertion might account for the increased AMPA:NMDA ratio we observed when recording without spermine in our internal solution (Figure 1D). We recorded AMPAR currents at several holding potentials (Figure 2A) and calculated the IV slopes of inward and outward currents. An increase in the ratio of the IV slopes indicates inward rectification of AMPARs and CP-AMPAR insertion (28). However, we did not detect an increase in the AMPAR rectification index (Figure 2B), suggesting that CI-AMPAR insertion most likely drives the refraining-associated increase in AMPA:NMDA.

Figure 2.

Refraining was not associated with other alterations of glutamatergic transmission. A, Example traces for AMPAR rectification indices, taken at holding potentials of −80, −40, 0, 10, 20, and 40 mV. Scale bars represent 50 pA × 50 milliseconds. B, AMPAR rectification index did not increase during refraining. C, Example traces demonstrating excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) recorded at +40 and −80 mV used for measurements of coefficient of variation (CV). D, CV of NMDA normalized to CV AMPA did not change during refraining. E, Example traces for NMDAR currents. Scale bars represent 20 pA × 50 milliseconds. F, NMDAR decay (weighted tau) did not change during refraining behavior. G, Paired pulse ratio example traces with stimulus artifact removed. Scale bars represent 100 pA × 50 milliseconds. H, Paired pulse ratio did not increase during refraining behavior. Sample sizes below bars indicate number of cells/animals. Data shown as mean ± SEM.

It is also possible that decreased NMDA current could have caused increased AMPA:NMDA ratio during refraining. Silent synapses house NMDARs but not AMPARs. Thus, pruning of silent synapses would be expected to increase AMPA:NMDA ratio. We tested for the possibility of loss of silent synapses by measuring the ratio of NMDA to AMPA coefficient of variation; which would increase if silent synapses were being pruned, during refraining (29). The CV-N/CV-A ratio did not change during refraining (t(47)= 0.61, p= 0.545), suggesting that silent synapses were not pruned. NMDAR current amplitudes are affected by subunit content, with a change to GluN3a-containing NMDARs decreasing NMDA current; thereby increasing AMPA:NMDA in the absence of AMPAR insertion (30). This subunit switch is also associated with increased NDMAR decay time (31). We calculated a weighted decay constant by dividing the area under the NMDAR curve by the peak NMDAR amplitude (Figure 2E). NMDAR decay kinetics were not affected by refraining t(45)= 0.93; p= 0.356; Figure 2F), suggesting a lack of NMDAR subunit alteration and strengthening the hypothesis that CI-AMPAR insertion is responsible for the increased NAshell AMPA:NMDA during refraining.

Due to our observation of decreased sEPSC frequency during refraining (Figure 1I), we hypothesized that there may be presynaptic adaptations that might affect paired pulse recordings in evoked EPSCs at −80 mV holding potential (Figure 2G). Paired pulse ratios (Peak 2 amplitude/Peak 1 amplitude) did not increase (t(17)= 0.05; p= 0.957), indicating a lack of presynaptic depression at the synapses responsible expressing t-SP during refraining (32). In summary of Figures 1 and 2, refraining appears to be associated with post-synaptic potentiation (mediated by CI-AMPAR insertion) selectively affecting the electrically stimulated synapses.

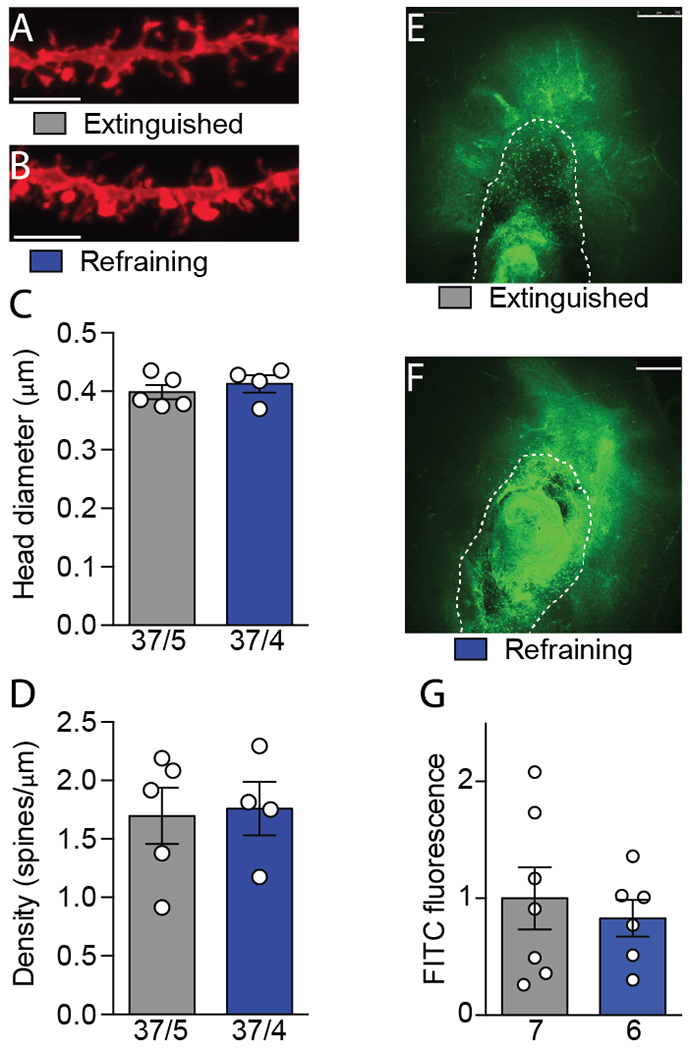

Refraining increases in AMPA:NMDA were not paralleled with increases in spine head diameter or MMP-2,9 activity in NAshell.

The transient increase in NAcore MSN AMPA:NMDA during cued cocaine seeking is associated with increased spine head diameter and/or density (3, 33). We hypothesized that one or both of these markers would be elevated in NAshell during refraining. MSNs were diolistically filled in brain slices from animals sacrificed at baseline or following 15 minutes of refraining behavior (Figure 3A–B) (22). Surprisingly, neither spine diameter nor density increased during refraining behavior (Diameter Figure 3C: t(7)= 0.74; p= 0.480; Density Figure 3D: t(7)= 0.18; p= 0.859).

Figure 3.

Refraining transient synaptic plasticity (t-SP) is structurally and morphologically distinct from drug-seeking t-SP. A, B, Representative spine micrographs from extinguished and refraining animals. Scale bar represents 5 μm). C, D, Neither spine head diameter nor density increased in nucleus accumbens shell (NAshell) during refraining. Sample sizes below bars indicate number of cells/animals. E, F, Representative zymography micrographs indicating matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity in terms of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) fluorescence. The dotted line outlines the injector tract and was not included in the analysis. Scale bars represent 250 μm. G, MMP activity did not increase in NAshell during refraining. Sample sizes below bars indicate number of animals. Data shown as mean ± SEM.

Drug seeking is also associated with increased matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-9) activity in NAcore, which we assayed via local microinjection of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-quenched gelatin (Figure 3E–F) (34). However, akin to spine morphology, the increase in NAshell AMPA:NMDA during refraining was not associated with increases in MMP-2,9 activity (t(11)= 0.53; p= 0.607; Figure 3G). Overall, these results reveal a dissociation between the t-SP associated with drug seeking in the NAcore and refraining in the NAshell.

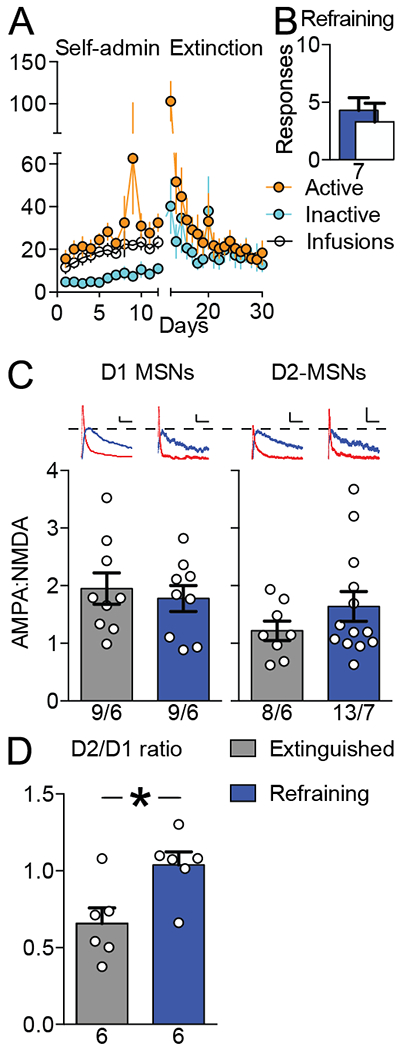

Refraining is associated with an increase in D2/D1 ratio of AMPA:NMDA.

The distinct constituents of cocaine seeking and refraining t-SP might arise from the involvement of different cell populations in the NAshell. Previous studies find that cocaine seeking t-SP occurs primarily in D1 MSNs, not D2 MSNs in the NAcore (20, 27). We hypothesized that the opposite would be true for refraining, and employed transgenic mice expressing tdTomato in D1-MSNs and/or eGFP in D2-MSNs to test this hypothesis. Mice underwent cocaine self-administration and extinction prior to a 15 minute test of refraining (Figure 4A–B). Refraining was not associated with increased AMPA:NMDA ratio in either cell type (D1-MSNs: t(16)= 0.48; p= 0.635; D2-MSNs: t(19)= 1.18; p= 0.252; Figure 4C). However, in all animals but one we recorded at least one D1 and one D2 MSN. By averaging the values over each cell type within each animal, a D2:D1 ratio of AMPA:NMDA was calculated for each mouse. After 15 min of refraining there was an increase in D2:D1 ratio compared to the D2:D1 in mice sacrificed 24 hr after the last extinction session (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Refraining is associated with an increase in D2/D1 ratio of AMPA:NMDA. A, Self-administration and extinction data for transgenic mice (Drd1a-tdTomato x Drd2-eGFP, N = 13). B, Refraining data for the 15-minute test. C, Neither D1-MSNs nor D2-MSNs in nucleus accumbens shell showed a significant increase in AMPA:NMDA ratio during 15 minutes of refraining behavior. Scale bars represent 20 pA × 50 milliseconds. Sample sizes below bars indicate number of cells/animals. D, Refraining was associated with increased D2/D1 ratio. At least one D1 and one D2 neuron was recorded in each mouse, and after averaging the values for each cell type within each mouse a D2/D1 ratio calculated by dividing average AMPA:NMDA for D2-MSNs by D1-MSNs. Sample sizes below bars indicate number of animals. Data shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

We also examined sEPSC amplitude and frequency, NMDAR decay kinetics, and paired pulse ratio as a function of D1-MSNs, D2-MSNs, and D2/D1 ratio; none of these metrics were altered during refraining behavior (Table 1), underscoring the selectivity of refraining potentiation for post-synaptic AMPARs.

Table 1.

No other electrophysiological characteristics of D1-MSNs, D2-MSNs, or the D2/D1 ratio are altered during refraining behavior.

| Dependent Measurement | Treatment Group | D1-MSN | D2-MSN | D2/D1 ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sEPSC amplitude (pA) | Extinction Refraining |

21.7 ± 3.04 (9) 21.1 ± 5.62 (9) |

20.9 ± 4.80 (8) 23.6 ± 3.90 (13) |

1.00 ± 0.06 (6) 1.18 ± 0.48 (6) |

| sEPSC frequency (Hz) | Extinction Refraining |

3.35 ± 2.15 (9) 3.27 ± 2.00 (9) |

4.16 ± 3.31 (8) 4.10 ± 3.08 (13) |

1.74 ± 1.11 (6) 1.62 ± 1.69 (6) |

| Paired-pulse ratio | Extinction Refraining |

1.22 ± 0.37 (9) 1.42 ± 0.21 (9) |

1.49 ± 0.49 (8) 1.26 ± 0.32 (13) |

1.38 ± 0.53 (6) 0.87 ± 0.12 (6) |

| NMDAR weighted tau (sec) | Extinction Refraining |

0.14 ± 0.03 (9) 0.14 ± 0.02 (9) |

0.14 ± 0.04 (8) 0.14 ± 0.02 (13) |

1.06 ± 0.35 (6) 0.99 ± 0.12 (6) |

Data shown as mean ± SD values, N is shown in parentheses and is cell number for D1- and D2-MSN columns and N is animal number for D2/D1 ratio.

DISCUSSION

In these experiments, animals experienced cocaine self-administration followed by extinction training in the same context. Animals re-exposed to the extinguished context refrain from cocaine seeking behavior, and in these experiments, we demonstrate that refraining is associated with increased AMPA:NMDA in NAshell. AMPA:NDMA increased transiently during the initial 15 minutes of refraining and reverted to baseline by the end of the two hour behavioral test. t-SP of NAshell MSNs was induced selectively by the extinguished context, and did not occur during cocaine seeking in the (non-extinguished) self-administration context. In contrast to t-SP produced in NAcore during cued cocaine seeking, the increase in AMPA:NMDA during refraining t-SP was not associated with parallel increases in spine head diameter or density, nor with increases in MMP activity. Also in contrast with cocaine seeking t-SP which occurs selectively in D1 MSNs, the increase in AMPA:NMDA during refraining was associated with a relative increase in input to D2 over D1 MSNs.

Our data suggest that t-SP was driven by post-synaptic insertion of AMPARs. However, an alternative hypothesis, that increased AMPA:NMDA ratio might have resulted from decreased NMDA currents, deserves discussion. We examined two possible sources of NMDA current decrease: pruning of silent synapses and NMDA subunit switching. Silent synapses contain NMDA, not AMPA receptors, and can be pruned (35). Thus, pruning of silent synapses selectively removes NMDA receptors while sparing AMPA receptors; thereby increasing AMPA:NMDA ratios in the absence of post-synaptic AMPAR insertion. However, we did not observe a change in the coefficient of NMDA normalized to AMPA currents, arguing against pruning of silent synapses during refraining.

NMDA subunit switching is another mechanism of decreasing NMDA currents because some subunit arrangements pass less current at +40 mV than others. If more conductive NMDARs were swapped with less conductive NMDARs during refraining, this could increase AMPA:NMDA ratios in the absence of post-synaptic AMPAR insertion(30). NMDAR subunit composition alters decay kinetics of NMDA currents as well as conduction properties. We did not observe changes in NMDA current decay kinetics, arguing against altered subunit composition. Thus, we did not find evidence that NMDA currents decrease during refraining. However, future experiments employing two photon glutamate uncaging would provide direct quantitative measurement of NMDA currents.

If post-synaptic AMPA insertion drives refraining-induced t-SP, the next question is why does refraining not increase the size of dendritic spines. We considered the possibility that calcium permeable (CP) AMPARs might replace calcium impermeable (CI) AMPARs, an event which does not change the size of dendritic spines (36), but would be expected to increase the AMPAR current amplitude (37, 38). However, the lack of change in the AMPAR rectification index argued against this possibility. An alternative explanation for the discordance between spine size and AMPA:NMDA ratio is that refraining t-SP only affects a subpopulation of synapses identified by preferential electrical stimulation of one or more afferents. While the spines belonging to the potentiated synapses may have expanded, if other populations of synapses were unchanged or de-potentiated our random spine analysis in NAshell may have missed the potentiated synapses. Stimulating only a subpopulation of afferent synapses to quantify AMPA/NMDA ratios could also account for why the sEPSC amplitude was unchanged, as sEPSCs could involve different synapses than those quantified from stimulated EPSC. Resolution to the possibility of different synaptic afferents contributing differentially to refraining-induced adaptations in MSNs awaits future studies employing optogenetic evaluation of specific inputs. However, our results are consistent with refraining t-SP being a relatively restricted phenomenon in terms of the portion of synapses potentiated.

We previously reported that in NAcore, refraining induced increases in AMPA:NMDA occurred selectively in D2-MSNs (27). Surprisingly, we could not as clearly demonstrate this in the NAshell in the same strain of BAC transgenic report mice. Our relatively low throughput (i.e. 1-2 cells of each phenotype from each mouse) may have precluded sufficient statistical power to definitively accomplish this goal. Nonetheless, we made three observations supporting preferential refraining-induced t-SP in D2-MSNs. 1) D1-MSNs show no indication of expressing t-SP. 2) Only a small sub-population of D2-MSNs appear to undergo marked refraining-induced potentiation. 3) Since we recorded from at least one D1- and D2-MSN in the majority of mice, we calculated a ratio of D2- to D1-MSN AMPA:NMDA ratios to estimate relative potentiation of D1- vs D2-MSNs within each animal. This analysis clearly showed significant shift in the D2/D1 ratio of AMPA:NMDA during refraining.

Our finding that t-SP occurs in NAshell during refraining suggests future experiments to reconcile two apparently conflicting observations in the literature. Extinction training after cocaine self-administration upregulates AMPARs in NAshell, and AMPAR upregulation mediates subsequent refraining (13). Moreover, AMPAR overexpression by viral delivery into NAshell neurons is sufficient to induce refraining in the absence of previous extinction training (13, 39). However, upregulated AMPARs are not localized to the PSD-95 subfraction, suggesting a lack of contribution to synaptic transmission under basal conditions (14). Indeed, under basal conditions AMPA:NMDA was not altered by extinction training per se (Fig. 1D vs. 1F), but was increased rapidly during refraining. Thus, AMPARs upregulated by extinction or viral overexpression may be contained in reserve pools (40), and associate with PSD-95 transiently during refraining. In summary, refraining is associated with t-SP in NAshell that appears to involve an increase in AMPA:NMDA in D2- over D1-MSNs. This form of t-SP is distinct from t-SP in NAcore that is strongly associated with cue-induced drug seeking, occurs in D1-MSNs and is associated with increased MMP-2,9 activity or spine head diameter.

Acknowledgments

Funding and Disclosure

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service Grants DA038893, DA012512, DA003906, DA015369, GM008716 and TR000061. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Conklin CA, Tiffany ST. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction. 2002;97(2):155–67. doi:14 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNally GP. Extinction of drug seeking: Neural circuits and approaches to augmentation. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76 Pt B:528–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scofield MD, Heinsbroek JA, Gipson CD, Kupchik YM, Spencer S, Smith AC, et al. The Nucleus Accumbens: Mechanisms of Addiction across Drug Classes Reflect the Importance of Glutamate Homeostasis. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68(3):816–71. doi: 10.1124/pr.116.012484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobi A, Seabold GK, Christensen CH, Bock R, Alvarez VA. Cocaine-induced plasticity in the nucleus accumbens is cell specific and develops without prolonged withdrawal. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31(5):1895–904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5375-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russo SJ, Dietz DM, Dumitriu D, Morrison JH, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. The addicted synapse: mechanisms of synaptic and structural plasticity in nucleus accumbens. Trends in neurosciences. 2010;33(6):267–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spencer S, Garcia-Keller C, Roberts-Wolfe D, Heinsbroek JA, Mulvaney M, Sorrell A, et al. Cocaine Use Reverses Striatal Plasticity Produced During Cocaine Seeking. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81(7):616–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.08.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith AC, Kupchik YM, Scofield MD, Gipson CD, Wiggins A, Thomas CA, et al. Synaptic plasticity mediating cocaine relapse requires matrix metalloproteinases. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(12):1655–7. doi: 10.1038/nn.3846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gipson CD, Kupchik YM, Shen H, Reissner KJ, Thomas CA, Kalivas PW. Relapse induced by cues predicting cocaine depends on rapid, transient synaptic potentiation. Neuron. 2013;77(5):867–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma YY, Lee BR, Wang X, Guo C, Liu L, Cui R, et al. Bidirectional modulation of incubation of cocaine craving by silent synapse-based remodeling of prefrontal cortex to accumbens projections. Neuron. 2014;83(6):1453–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pascoli V, Terrier J, Espallergues J, Valjent E, O’Connor EC, Luscher C. Contrasting forms of cocaine-evoked plasticity control components of relapse. Nature. 2014;509(7501):459–64. doi: 10.1038/nature13257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LaLumiere RT, Smith KC, Kalivas PW. Neural circuit competition in cocaine-seeking: roles of the infralimbic cortex and nucleus accumbens shell. The European journal of neuroscience. 2012;35(4):614–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.07991.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters J, LaLumiere RT, Kalivas PW. Infralimbic prefrontal cortex is responsible for inhibiting cocaine seeking in extinguished rats. J Neurosci. 2008;28(23):6046–53. doi:28/23/6046 [pii] 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1045-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton MA, Schmidt EF, Choi KH, Schad CA, Whisler K, Simmons D, et al. Extinction-induced upregulation in AMPA receptors reduces cocaine-seeking behaviour. Nature. 2003;421(6918):70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knackstedt LA, Moussawi K, Lalumiere R, Schwendt M, Klugmann M, Kalivas PW. Extinction training after cocaine self-administration induces glutamatergic plasticity to inhibit cocaine seeking. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30(23):7984–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1244-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J, Finkelstein J, Choi JY, Witten IB. Linking Cholinergic Interneurons, Synaptic Plasticity, and Behavior during the Extinction of a Cocaine-Context Association. Neuron. 2016;90(5):1071–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torregrossa MM, Sanchez H, Taylor JR. D-cycloserine reduces the context specificity of pavlovian extinction of cocaine cues through actions in the nucleus accumbens. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30(31):10526–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2523-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith RJ, Lobo MK, Spencer S, Kalivas PW. Cocaine-induced adaptations in D1 and D2 accumbens projection neurons (a dichotomy not necessarily synonymous with direct and indirect pathways). Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23(4):546–52. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bock R, Shin JH, Kaplan AR, Dobi A, Markey E, Kramer PF, et al. Strengthening the accumbal indirect pathway promotes resilience to compulsive cocaine use. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16(5):632–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.3369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinsbroek JA, Neuhofer DN, Griffin WC 3rd, Siegel GS, Bobadilla AC, Kupchik YM, et al. Loss of plasticity in the D2-accumbens pallidal pathway promotes cocaine seeking. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2659-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bobadilla AC, Heinsbroek JA, Gipson CD, Griffin WC, Fowler CD, Kenny PJ, et al. Corticostriatal plasticity, neuronal ensembles, and regulation of drug-seeking behavior. Prog Brain Res. 2017;235:93–112. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2017.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith ACW, Scofield MD, Heinsbroek JA, Gipson CD, Neuhofer D, Roberts-Wolfe DJ, et al. Accumbens nNOS Interneurons Regulate Cocaine Relapse. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2017;37(4):742–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2673-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen H, Sesack SR, Toda S, Kalivas PW. Automated quantification of dendritic spine density and spine head diameter in medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens. Brain structure & function. 2008;213(1-2):149–57. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0184-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motulsky HJ, Brown RE. Detecting outliers when fitting data with nonlinear regression - a new method based on robust nonlinear regression and the false discovery rate. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Ciano P, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Differential effects of nucleus accumbens core, shell, or dorsal striatal inactivations on the persistence, reacquisition, or reinstatement of responding for a drug-paired conditioned reinforcer. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(6):1413–25. doi:1301522 [pii] 10.1038/sj.npp.1301522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee BR, Ma YY, Huang YH, Wang X, Otaka M, Ishikawa M, et al. Maturation of silent synapses in amygdala-accumbens projection contributes to incubation of cocaine craving. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16(11):1644–51. doi: 10.1038/nn.3533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruz FC, Babin KR, Leao RM, Goldart EM, Bossert JM, Shaham Y, et al. Role of nucleus accumbens shell neuronal ensembles in context-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. J Neurosci. 2014;34(22):7437–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0238-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts-Wolfe D, Clara Bobadilla A , Heinsbroek J, Neuhofer D, Kalivas PW. Drug refraining and seeking potentiate synapses on distinct populations of accumbens medium spiny neurons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0791-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamboj SK, Swanson GT, Cull-Candy SG. Intracellular spermine confers rectification on rat calcium-permeable AMPA and kainate receptors. J Physiol. 1995;486 ( Pt 2):297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kullmann DM. Amplitude fluctuations of dual-component EPSCs in hippocampal pyramidal cells: implications for long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1994;12(5):1111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan T, Mameli M, O’Connor EC, Dey PN, Verpelli C, Sala C, et al. Expression of cocaine- evoked synaptic plasticity by GluN3A-containing NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2013;80(4):1025–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cull-Candy SG, Leszkiewicz DN. Role of distinct NMDA receptor subtypes at central synapses. Sci STKE. 2004;2004(255):re16. doi:stke.2552004re16 [pii] 10.1126/stke.2552004re16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Debanne D, Guerineau NC, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Paired-pulse facilitation and depression at unitary synapses in rat hippocampus: quantal fluctuation affects subsequent release. J Physiol. 1996;491 ( Pt 1):163–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen H, Moussawi K, Zhou W, Toda S, Kalivas PW. Heroin relapse requires long-term potentiation-like plasticity mediated by NMDA2b-containing receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(48):19407–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112052108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mook OR, Van Overbeek C, Ackema EG, Van Maldegem F, Frederiks WM. In situ localization of gelatinolytic activity in the extracellular matrix of metastases of colon cancer in rat liver using quenched fluorogenic DQ-gelatin. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51(6):821–9. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graziane NM, Sun S, Wright WJ, Jang D, Liu Z, Huang YH, et al. Opposing mechanisms mediate morphine- and cocaine-induced generation of silent synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(7):915–25. doi: 10.1038/nn.4313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellone C, Luscher C. Cocaine triggered AMPA receptor redistribution is reversed in vivo by mGluR-dependent long-term depression. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(5):636–41. doi:nn1682 [pii] 10.1038/nn1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu SJ, Cull-Candy SG. Activity-dependent change in AMPA receptor properties in cerebellar stellate cells. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2002;22(10):3881–9. doi:20026392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu SQ, Cull-Candy SG. Synaptic activity at calcium-permeable AMPA receptors induces a switch in receptor subtype. Nature. 2000;405(6785):454–8. doi: 10.1038/35013064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bachtell RK, Choi KH, Simmons DL, Falcon E, Monteggia LM, Neve RL, et al. Role of GluR1 expression in nucleus accumbens neurons in cocaine sensitization and cocaine-seeking behavior. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27(9):2229–40. doi:EJN6199 [pii] 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kneussel M, Hausrat TJ. Postsynaptic Neurotransmitter Receptor Reserve Pools for Synaptic Potentiation. Trends in neurosciences. 2016;39(3):170–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]