Abstract

Exercise seems to enhance the beneficial effect of bariatric (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass [RYGB]) surgery on insulin resistance. We hypothesized that skeletal muscle extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling may underlie these benefits. Women were randomized to either a combined aerobic and resistance exercise training program following RYGB (RYGB + ET) or standard of care (RYGB). Insulin sensitivity was assessed by oral glucose tolerance test. Muscle biopsy specimens were obtained at baseline and 3 and 9 months after surgery and subjected to comprehensive phenotyping, transcriptome profiling, molecular pathway identification, and validation in vitro. Exercise training improved insulin sensitivity beyond surgery alone (e.g., Matsuda index: RYGB 123% vs. RYGB + ET 325%; P ≤ 0.0001). ECM remodeling was reduced by surgery alone, with an additive benefit of surgery and exercise training (e.g., collagen I: RYGB −41% vs. RYGB + ET −76%; P ≤ 0.0001). Exercise and RYGB had an additive effect on enhancing insulin sensitivity, but surgery alone did not resolve insulin resistance and ECM remodeling. We identified candidates modulated by exercise training that may become therapeutic targets for treating insulin resistance, in particular, the transforming growth factor-β1/SMAD 2/3 pathway and its antagonist follistatin. Exercise-induced increases in insulin sensitivity after bariatric surgery are at least partially mediated by muscle ECM remodeling.

Introduction

Bariatric surgery confers cardiometabolic protection to obese individuals, contributing to a reduced risk of all-cause mortality (1,2). However, the extent of metabolic benefit may be subject to lifestyle changes after the surgery (3). While exercise training appears to enhance the effects of surgery on insulin sensitivity (4,5), the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown.

Coen et al. (4) reported that an exercise program enhanced the effects of bariatric surgery on insulin sensitivity, and this was attributed to increased mitochondrial oxidative capacity and a reduction in specific lipid species that are known to impair insulin signaling. While controversy still exists as to whether mitochondrial dysfunction plays a significant role in the pathophysiology of muscle insulin resistance (6–8), other mechanisms underpinning the improvements in insulin sensitivity induced by exercise after bariatric surgery may be proposed.

Here, we tested the hypothesis that muscle extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling would be a mechanism mediating the beneficial effects of exercise on insulin sensitivity in postbariatric surgery patients. An abnormal ECM phenotype is linked to defective cell-to-cell and cell-to-ECM interactions, ultimately compromising insulin’s access to myocytes (9,10). Indeed, muscle ECM expansion is tightly associated with skeletal muscle insulin resistance and altered expression of several ECM proteins in healthy lean and obese adults and patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) (11–14). Importantly, exercise training appears to reduce muscle ECM thickness in patients with T2D and hypertension (15,16). Whether ECM remodeling underlies the exercise-induced increase in insulin sensitivity in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery remains unknown. Using a top-down approach that included comprehensive phenotyping, transcriptome profiling, molecular pathways identification, and validation of clinical findings in vitro, we investigated the role of muscle ECM remodeling on exercise-induced increases in insulin sensitivity in women with obesity who were undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery.

Research Design and Methods

Experimental Design

This was a randomized controlled trial. Data were collected between March 2015 and November 2018 in São Paulo, Brazil. The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and patients provided written informed consent before participation.

Patients with T2D and glucose intolerance, according to American Diabetes Association diagnosis criteria, were recruited from the metabolic and bariatric surgery unit of the university hospital. Inclusion criteria were women who were eligible for bariatric surgery (BMI >40 kg/m2 or ≥35 kg/m2 with associated comorbidities), 18–55 years of age, and not engaged in an exercise training program for at least 1 year before the study. Exclusion criteria were cancer in the past 5 years and any cardiovascular diseases, neurological disorders, or skeletal muscle impairment that would contraindicate exercise practice.

Before surgery (PRE), patients were randomly assigned (1:1) into either RYGB surgery or RYGB surgery followed by exercise training (RYGB + ET) using a computer-generated randomization code. Clinical and laboratory parameters were assessed at PRE and 3 and 9 months after the surgery (POST3 and POST9, respectively). The 6-month exercise intervention (for RYGB + ET) started at POST3 upon postsurgery medical clearance for exercise participation. A healthy control group comprising lean and age-matched women (lean group, age 38 ± 7 years) was also recruited and assessed at PRE to provide reference values for some variables.

Exercise Intervention

The RYGB + ET group participated in a 6-month, three-times-a-week, intrahospital, supervised, combined aerobic and resistance exercise training program, whereas the RYGB group received standard postsurgery care. The exercise protocol is thoroughly described elsewhere (17). Briefly, exercise training sessions included a 5-min light warm-up followed by strengthening exercises for major muscle groups (i.e., 45° leg press, leg extension, half-squat, bench press, lateral pulldown, seated rowing, calf raise) and aerobic exercise. The resistance exercise protocol comprised three sets of 8–12 repetitions maximum, with a 60-s rest interval between sets and exercises. Load progression (5%) was implemented when patients were able to perform two or more repetitions than previously determined. Aerobic exercise training consisted of 30–60 min (10-min progression every 4 weeks) of treadmill walking at a moderate intensity (i.e., corresponding to 50% of the delta difference between the anaerobic ventilatory threshold and respiratory compensation point). Heart rate was monitored throughout every session to ensure proper exercise intensity (S810i; Polar). As evidence of the exercise training’s efficacy, the RYGB + ET group showed greater lower-limb muscle strength (assessed by a 1-repetition max leg press [18]) and VO2peak (assessed by maximal cardiopulmonary exercise test [19]) than RYGB at POST9 (95% CI 58.9–82.8 kg [P < 0.0001] and 0.1–4.3 mL/kg/min [P = 0.0433], respectively).

Insulin Sensitivity and Secretion

Surrogates of insulin sensitivity and secretion were determined by an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). After a 12-h overnight fast, samples were collected at baseline and 30, 60, 90, and 120 min following the 75-g glucose challenge (Glutol), and plasma glucose and insulin were assessed. The total area under the curve (tAUC) for glucose, insulin, and HOMA of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) were calculated from the OGTT. Matsuda insulin sensitivity index (ISI) and muscle ISI (mISI) derived from the OGTT were determined as previously described (20). To estimate the early-phase insulin secretion from the OGTT, the disposition index (DI) was calculated using the web-based DI calculator as follows: (Δinsulin0–30 / Δglucose0–30) × Matsuda ISI (https://mmatsuda.diabetes-smc.jp/MIndex.html). The OGTT assessments were performed between 72 and 96 h after the last exercise bout for RYGB + ET.

Blood Chemistry

Fasting HDL, LDL, VLDL, triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and C-reactive protein (CRP), leptin, total adiponectin, and follistatin (FLST) were also assessed. Plasma glucose, TC, TG, and HDL (SBA-200; CELM, São Caetano do Sul, Brazil) and CRP (Dimension EXL 2000; Siemens) were analyzed with an automated analyzer using enzymatic methods. Insulin was evaluated by a human-specific radioimmunoassay method (Diagnostic Products Corporation), and C-peptide was assessed by a chemiluminescent immunometric assay (Roche Diagnostics). HbA1c was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography performance by ion exchange using the Variant II automated analyzer (Bio-Rad). Leptin (Millipore), total adiponectin (Cloud-Clone Corp.), and FLST (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were determined by ELISA, according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Body Composition

DXA scans (GE Healthcare) were performed to evaluate changes in fat mass and visceral adipose tissue (using CoreScan software).

Muscle Biopsies

Percutaneous vastus lateralis biopsy specimens were taken using a 5-mm modified Bergström needle. All biopsies were performed following an overnight fast, with the posttraining biopsy being performed between 72 and 96 h after the last exercise training session.

ECM Immunostaining

Frozen muscle tissues were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound and sectioned (7-μm thick) with a cryostat. Muscle sections were used for collagen I and III staining (both from Rockland) as an ECM marker. For negative staining controls, sections were incubated with PBS instead of the specific antibody. The images were captured with a microscope with a magnification of 200×, and the quantitative fluorescent staining image analysis was performed with Image J software (National Institutes of Health) and expressed as arbitrary units of fluorescence as previously described (21).

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Fresh muscles from 10 patients per group were immediately placed in a 6.25% glutaraldehyde solution buffered with 0.1 mol/L sodium cacodylate/HCl (pH 7.4) and stored at 4°C until analysis as previously described (22). The muscle samples were postfixed in 1% OsO4, stained en bloc, and embedded in Epon 812 (Sigma-Aldrich). One-micrometer transverse sections were cut with a diamond knife on an ultramicrotome (Ultratom III; LKB), and skeletal muscle capillary images were obtained using a JEOL 1010 transmission electron microscope with a high-resolution digital camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques) at a magnification of 15,000×. A damage score was determined, as previously described (22).

RNA-Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

For RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq), muscle RNA was isolated (six patients per group) using the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Total RNA concentration was assessed spectrophotometrically at 260 nm (GE Healthcare), and RNA integrity number (≥7) was checked using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent). Sample concentration was normalized, and cDNA pools were created for each sample and subsequently tagged with a barcoded oligo adapter to allow for sample-specific resolution using the QuantSeq 3′ mRNA-Seq Library Prep Kit (Lexogen). Sequencing was carried out using a HiSeq 2500 platform (Illumina) with 75-bp single-end reads. Reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38.77). Annotation and preparation of the sequencing data for downstream analysis were performed by a custom R script (23), with annotations downloaded from BioMart (R version 3.4.3, RStudio version 1.1.423, and BioMart version 2.24.1).

Raw count data were normalized through trimmed mean of M-values normalization in edgeR (24) and adjusted for mean variance effects through the voom function in limma (25). Genes were considered differentially expressed on the basis of a false discovery rate (FDR) ≤10% and the absolute log2 fold change >0.58. Principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out, through the princomp package in R to identify transcriptome-driven sample clusters as well as possible outlier samples. Pathway enrichment analysis was carried out through the preranked gene set enrichment analysis method (26) by querying a custom database consisting of gene sets from Wikipathways (https://www.wikipathways.org) plus nine ECM-specific gene sets from the Matrisome project (https://web.mit.edu/hyneslab/matrisome). Enrichments with an FDR ≤10% were considered significant. QuantSeq raw data have been deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession GSE 137631).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the SuperScript Platinum One-Step Kit (Invitrogen), with incorporated Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The fold changes from PRE were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, and all mRNA levels were normalized to β2-microglobulin.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described (27). Gel-to-gel variation and equal protein loading were controlled using a standardized sample on each gel and GAPDH and HSC70 expression for all immunoblot assays, respectively. Phosphorylated membranes were stripped and reprobed with a new primary antibody against their respective total protein (Supplementary Table 1) after removal of the first antibody by incubation in stripping buffer (Restore PLUS Western Blot; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Blots were quantified using Scion Image software.

Subcellular Fractionation

Cytosolic and enriched nuclear fraction were obtained from samples obtained at POST9, using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples containing the cytosolic and nuclear fractions were sectioned and incubated with primary antibodies against β-catenin (serine [Ser] 33/37 threonine [Thr] 41), β-catenin, SMAD 2/3 (Ser 465/467 Ser 423/425), SMAD 2/3, histone H3, and α-tubulin. The absence of α-tubulin and the abundance of histone H3 protein were used to confirm the quality of cytosolic and nuclear enrichment fractions, respectively.

Immunoprecipitation Assay

Muscle homogenates were extracted on lysis buffer containing 20 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.4), 137 mmol/L NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20% glycerol, 10 mmol/L sodium fluoride, 1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 2 μg/mL leupeptin, and aprotinin. The lysates were centrifuged at 12,000g for 15 min at 4°C. SMAD 2/3 antibody was immunoprecipitated by incubating the lysates with protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:500 dilution overnight at 4°C. Protein kinase B (AKT) Ser 473 was probed overnight followed by incubation in horseradish peroxidase–tagged secondary antibody. Input protein loading and IgG for nonspecific responses were also blotted.

Cell Culture

In vitro experiments were performed in differentiated C2C12 myoblasts (ATCC), as previously described (28). To test whether transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) impairs the insulin signaling without changes in myotube phenotype, differentiated myotubes were then serum starved in low-glucose DMEM (1 g/L) supplemented with 1% BSA before 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1.8 μg/mL FLST (R&D Systems) treatment for 3 h. Insulin (100 nmol/L) was added into the wells 30 min before the end of the experiment. Cells were washed three times in ice-cold PBS, lysed, and harvested in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The lysates were purified by centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min at 4°C, and protein content was measured using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology) and assessed by Western blotting as described above.

Sample Size Calculation and Statistical Analysis

Sample size was determined with the aid of G-Power version 3.1.2 software. The analysis was conducted by inputting α-error (0.05), power (1 – β-error = 0.90), and effect size (Hedges g = 1.68), as extracted from a previous study that had examined the effects of exercise training on insulin sensitivity in postbariatric surgery patients (5). The total sample size was determined to be 40 patients.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or SEM, estimated mean difference between groups at POST9, and 95% CI, except where otherwise stated. All data were analyzed using an intention-to-treat approach to preserve the integrity of randomization. Dependent variables were analyzed by a mixed-model analysis for repeated measures, using group (RYGB and RYGB + ET) and time (PRE, POST3, and POST9) as fixed factors, and subjects as a random factor using SAS 9.1 software. Post hoc tests with Tukey adjustment were performed for multiple comparisons. Associations were calculated by Pearson correlation coefficient. Comparisons between groups at PRE were performed by Student t test or Fisher exact test. Significance level was set at P ≤ 0.05. To facilitate the reader, main effects of time are described as effects of surgery, whereas group × time interactions at POST9 are described as effects of exercise training.

Data and Resource Availability

Data and resources are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

General Health-Related Markers at Baseline and 3 and 9 Months After Bariatric Surgery

Two hundred thirty RYGB-eligible patients were screened for participation; 62 met the inclusion criteria and were assigned to either RYGB (n = 31) or RYGB + ET (n = 31) (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Patients’ adherence to the exercise intervention was 81.5 ± 13.1%. No adverse events were reported.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics of RYGB, RYGB + ET, and lean participants

| RYGB (n = 31) | RYGB + ET (n = 31) | P value (RYGB vs. RYGB + ET) | Lean (n = 16) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42 ± 7 | 39 ± 7 | 0.28 | 38 ± 7 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.99 | 0 (0) |

| Current smoking | 2 (6.4) | 2 (6.4) | 0.63 | 0 (0) |

| T2D | 19 (61.2) | 21 (67.7) | 0.82 | 0 (0) |

| Hypertension | 20 (64.5) | 22 (70.9) | 0.82 | 0 (0) |

| Education | ||||

| Primary or middle school | 9 (29.0) | 10 (32.2) | 0.78 | 0 (0) |

| High school | 18 (58.0) | 17 (54.8) | 0.81 | 1 (6.3) |

| College | 4 (13.0) | 4 (13.0) | 0.99 | 15 (93.7) |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Low | 22 (71.0) | 23 (74.2) | 0.90 | 2 (12.6) |

| Medium | 9 (29.0) | 8 (25.8) | 0.82 | 7 (43.7) |

| High | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.99 | 7 (43.7) |

| Medication | ||||

| β-Blockers | 2 (6.4) | 2 (6.4) | 0.99 | 0 (0) |

| Metformin | 3 (9.6) | 3 (9.6) | 0.99 | 0 (0) |

| Insulin | 2 (6.4) | 1 (3.2) | 0.34 | 0 (0) |

| ACE inhibitor | 5 (16.1) | 5 (16.1) | 0.99 | 0 (0) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 0.99 | 0 (0) |

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonist | 5 (16.1) | 3 (9.6) | 0.29 | 0 (0) |

| Diuretics | 7 (22.5) | 9 (29.0) | 0.63 | 0 (0) |

| Body composition | ||||

| Body weight (kg) | 124.9 ± 8.8 | 130.0 ± 22.2 | 0.39 | 62.2 ± 6.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 47.3 ± 8.5 | 50.2 ± 7.2 | 0.36 | 23.2 ± 2.7 |

| Fat mass (%) | 51.3 ± 4.9 | 52.2 ± 4.4 | 0.38 | 28.6 ± 7.1 |

| VAT (kg) | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 0.71 | 0.2 ± 0.2 |

| Biochemical markers | ||||

| HDL (mg/dL) | 40.5 ± 9.4 | 46.2 ± 11.7 | 0.17 | 71.1 ± 16.6 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 106.7 ± 30.7 | 106.4 ± 34.2 | 0.66 | 85.6 ± 28.4 |

| VLDL (mg/dL) | 27.0 ± 11.6 | 25.7 ± 15.4 | 0.72 | 15.0 ± 6.1 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 129.6 ± 48.5 | 128.7 ± 77.5 | 0.96 | 75.1 ± 30.6 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 173.4 ± 35.2 | 178.2 ± 33.0 | 0.60 | 75.1 ± 30.6 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 128.5 ± 45.8 | 127.5 ± 54.3 | 0.94 | 80.6 ± 5.9 |

| Fasting insulin (μIU/mL) | 27.7 ± 23.8 | 22.5 ± 9.4 | 0.31 | 6.5 ± 4.1 |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | 4.5 ± 2.2 | 3.9 ± 1.3 | 0.18 | 1.7 ± 0.5 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.6 ± 2.1 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 0.15 | 5.2 ± 0.2 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 49.0 ± 15.6 | 49.0 ± 8.9 | 0.15 | 33.0 ± 1.5 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 11.5 ± 7.1 | 13.0 ± 7.9 | 0.45 | 1.3 ± 0.7 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 94.8 ± 25.2 | 98.1 ± 30.3 | 0.48 | 12.7 ± 4.1 |

| Adiponectin (ng/mL) | 5,982.0 ± 3,022.7 | 5,590.0 ± 1,403.6 | 0.53 | 9,410.6 ± 2,489.1 |

| FLST (ng/mL) | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 2.9 ± 2.3 | 0.85 | 4.9 ± 1.3 |

Data are mean ± SD or n (%). VAT, visceral adipose tissue.

Body weight, BMI, fat mass, visceral fat, VO2peak, HDL, LDL, VLDL, TG, TC, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, C-peptide, HbA1c, CRP, leptin, adiponectin, and FLST were all improved following surgery (Table 2). There were no group × time interactions for these parameters. However, a delta change analysis (POST9 – PRE) showed that improvements in VO2peak were more pronounced in the exercised versus nonexercised group, evidencing the efficacy of the exercise intervention (data not shown).

Table 2.

Effects of exercise training following RYGB surgery on body composition and biochemical markers

| RYGB (n = 31) | RYGB + ET (n = 31) | Difference (95% CI) after intervention | P value group × time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRE | POST3 | POST9 | PRE | POST3 | POST9 | |||

| Body weight (kg)abc | 124.9 ± 22.4 | 96.0 ± 12.8 | 82.3 ± 12.7 | 130.0 ± 22.4 | 104.9 ± 8.4 | 89.5 ± 14.8 | −0.30 (−15.42 to 14.82) | 0.26 |

| BMI (kg/m2)abc | 47.5 ± 8.4 | 37.1 ± 5.8 | 31.8 ± 5.4 | 50.2 ± 7.2 | 40.9 ± 6.8 | 34.2 ± 5.4 | 1.36 (−5.52 to 2.80) | 0.15 |

| Fat mass (%)abc | 51.5 ± 4.8 | 45.9 ± 7.1 | 37.7 ± 7.6 | 52.2 ± 4.4 | 47.8 ± 4.7 | 38.4 ± 6.2 | −0.10 (−3.58 to 3.37) | 0.46 |

| VAT (kg)abc | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.140 (−0.217 to 0.498) | 0.55 |

| HDL (mg/dL)bc | 40.5 ± 9.4 | 42.0 ± 9.2 | 49.6 ± 12.1 | 46.2 ± 11.7 | 44.4 ± 11.7 | 57.4 ± 13.3 | −7.63 (−13.87 to −1.39) | 0.05 |

| LDL (mg/dL)abc | 106.7 ± 30.7 | 96.3 ± 24.1 | 82.4 ± 30.5 | 110.3 ± 29.4 | 91.5 ± 33.7 | 75.2 ± 19.2 | 7.54 (−8.94 to 24.03) | 0.26 |

| VLDL (mg/dL)bc | 27.0 ± 11.6 | 21.9 ± 6.7 | 19.1 ± 6.7 | 25.7 ± 15.4 | 23.6 ± 14.8 | 14.7 ± 3.6 | 4.51 (−2.19 to 11.22) | 0.17 |

| TG (mg/dL)abc | 129.6 ± 48.5 | 110.4 ± 34.7 | 97.7 ± 41.7 | 128.7 ± 77.5 | 101.5 ± 47.2 | 75.3 ± 24.8 | 14.52 (−15.61 to 44.65) | 0.63 |

| TC (mg/dL)ab | 173.4 ± 35.2 | 159.6 ± 27.6 | 151.7 ± 36.9 | 178.2 ± 33.0 | 157.0 ± 35.2 | 147.8 ± 23.1 | 3.36 (−15.15 to 21.88) | 0.45 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL)ab | 128.5 ± 45.8 | 88.3 ± 10.6 | 84.7 ± 8.0 | 127.5 ± 54.3 | 89.2 ± 25.6 | 80.7 ± 20.2 | 10.19 (−14.12 to 34.51) | 0.95 |

| Fasting insulin (μIU/mL)ab | 27.7 ± 23.8 | 12.0 ± 5.2 | 11.2 ± 3.9 | 22.5 ± 9.4 | 12.3 ± 6.6 | 6.6 ± 1.6 | 5.91 (−5.02 to 16.85) | 0.88 |

| C-peptide (ng/mL)ab | 4.5 ± 2.2 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 1.3 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 0.71 (−0.06 to 1.49) | 0.27 |

| HbA1c (%)ab | 6.6 ± 2.1 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 0.4 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 0.18 (−0.45 to 0.83) | 0.91 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol)ab | 49.0 ± 15.6 | 40.0 ± 2.9 | 40.0 ± 2.2 | 49.0 ± 8.9 | 39.3 ± 2.9 | 38.6 ± 2.2 | 0.18 (−0.45 to 0.83) | 0.91 |

| CRP (mg/dL)abc | 11.5 ± 7.1 | 7.1 ± 5.1 | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 13.0 ± 7.9 | 8.1 ± 5.8 | 2.2 ± 2.4 | 2.17 (−1.45 to 5.80) | 0.28 |

| Leptin (ng/mL)ab | 94.8 ± 25.2 | 42.2 ± 33.0 | 29.9 ± 24.0 | 98.1 ± 30.3 | 66.5 ± 31.3 | 31.0 ± 30.0 | −7.94 (−29.20 to 13.32) | 0.21 |

| Adiponectin (ng/mL)abc | 5,982 ± 3,022 | 10,012 ± 6,403 | 9,243 ± 4,797 | 5,590 ± 1,403 | 6,241 ± 2,611 | 10,569 ± 6,200 | 1,929 (−5,342 to 2,383) | 0.46 |

| FLST (ng/mL)b | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 5.2 | 5.8 ± 3.6 | 2.9 ± 2.3 | 4.3 ± 2.3 | 13.3 ± 17.1 | −7.46 (−10.48 to 6.58) | 0.31 |

Data are mean ± SD, estimated mean of differences between RYGB and RYGB + ET (95% CI), and P level for group × time interaction (mixed model for repeated measures) at POST9. VAT, visceral adipose tissue.

P < 0.05 for main effect of time (PRE vs. POST3).

P < 0.05 for main effect of time (PRE vs. POST9).

P < 0.05 for main effect of time (POST3 vs. POST9).

Exercise Training Following RYGB Surgery Enhances Insulin Sensitivity and Muscle Insulin Signaling

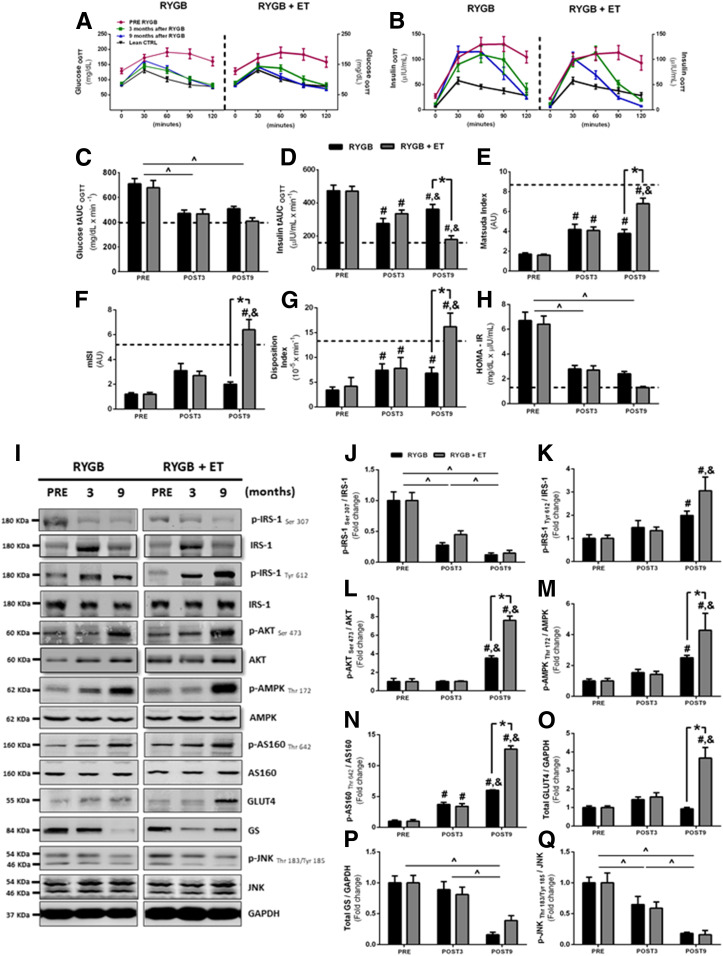

Insulin tAUC was significantly reduced after surgery; importantly, exercise substantially enhanced this response (Fig. 1D). Glucose tAUC was reduced after surgery (Fig. 1C) but without any additive effect of exercise. Surgery improved the Matsuda ISI, a surrogate of whole-body insulin sensitivity, and this effect was potentiated by exercise (Fig. 1E). mISI was improved only in the exercised group (Fig. 1F). DI was increased following surgery, with an additive effect of exercise (Fig. 1G). Surgery also improved HOMA-IR, with no effect of exercise (Fig. 1H). Of interest, several surrogates of insulin resistance (e.g., insulin tAUC, Matsuda ISI, mISI, DI) reached values typically seen in lean group subjects only in the exercised group (see dotted lines in Fig. 1), suggesting that surgery in the absence of exercise may only elicit a partial resolution of insulin sensitivity.

Figure 1.

OGTT, insulin resistance, and skeletal muscle insulin signaling pathway. A and B: Glucose and insulin concentrations during OGTT. C and D: tAUC glucose and insulin. E: Whole-body ISI. F: mISI derived from OGTT. G: β-Cell function index. H: HOMA-IR. I: Representative phosphorylated bands and total proteins with GAPDH as a loading control (n = 12–15 per group). J–Q: Phosphorylated proteins were normalized by respective total protein as well as other proteins normalized by GAPDH. Data are mean ± SEM. Dotted lines depict reference values for the age-matched healthy lean group. ^P < 0.05 for main effect of time; #P < 0.05 for within-group comparison (vs. PRE); &P < 0.05 for within-group comparison (vs. POST3); *P < 0.05 for between-group comparison at POST9. AU, arbitrary unit; CTRL, control.

We subsequently examined the effects of surgery and exercise on muscle insulin signaling. Surgery decreased insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1 Ser 307) activation (Fig. 1J) while increasing IRS-1 tyrosine (Tyr) 612 activation (Fig. 1K), both of which were unaffected by exercise. Total IRS-1 content (from IRS-1 Ser 307, but not from IRS-1 Tyr 612 membranes), significantly increased after exercise training (Supplementary Fig. 2A and B). AKT and AMPK phosphorylation were increased after surgery; this response was enhanced by exercise (Fig. 1L and M). Total AKT content increased after surgery in both groups, whereas total AMPK content was only increased with exercise training (Supplementary Fig. 2C and D). The Akt substrate of 160 kDa (AS160) phosphorylation also increased after surgery and was further improved by exercise (Fig. 1N). Total AS160 content only increased with exercise training (Supplementary Fig. 2E). Of note, exercise also substantially increased GLUT type 4 (GLUT4) content (Fig. 1O), an effect that was not observed after surgery alone. Glycogen synthase (GS) content and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylation, but not total content (Supplementary Fig. 2F), were decreased following surgery, with no effect of exercise (Fig. 1P and Q). These findings reveal that exercise promotes an extensive regulation of insulin signaling, with robust activation of phosphorylated (p)-AKT, p-AMPK, p-AS160, and GLUT4, all of which play a key role in muscle glucose uptake (29).

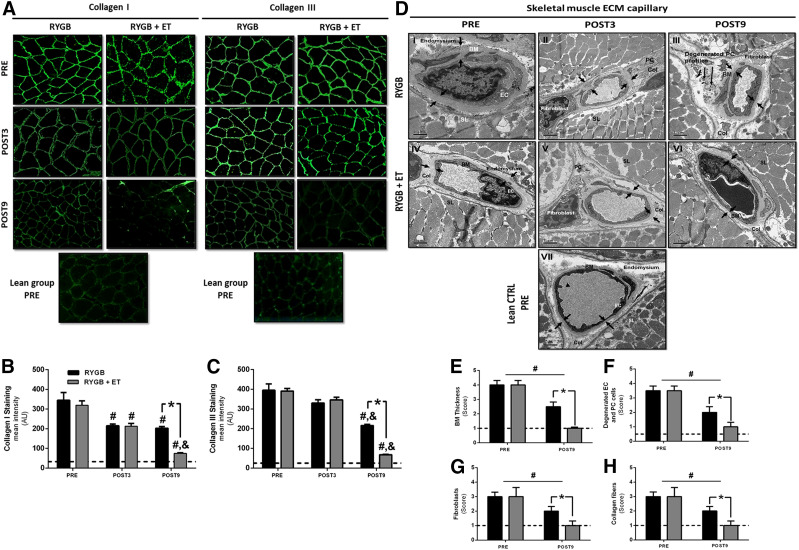

Exercise Training Following RYGB Surgery Shifts Muscle ECM Toward a Healthier Phenotype

Next, we investigated the role of muscle ECM remodeling on the improvements in insulin sensitivity after exercise and surgery (Fig. 2A). Immunohistochemistry staining revealed reduced collagen I and III after surgery, while exercise training significantly potentiated this effect (Fig. 2B and C). Transmission electron microscopy of skeletal muscle capillaries from the healthy control group showed the capillary lumen (Fig. 2D, VII) mantled with endothelial cells (ECs) and a continuous border along the basement membrane (BM), which merged abruptly with the loose endomysium. The pericapillary BM exhibited a homogenous layer of amorphous material. The pericytes (PCs) were embedded within the BM, and fibroblasts were located exclusively in the endomysium, hence devoid of BM coverage (Fig. 2D, VII). In contrast, the skeletal muscle capillary from the nonexercised group (Fig. 2D, I–III) showed prominent BM thickness, loss of endomysium space, reduction of the capillary lumen, sarcolemma atrophy, activated fibroblasts, and noticeable collagen fibers. Degenerated PC or EC profiles (“ghosts”) were identified within the BM layer, which was delineated by the plasmalemma and did not show evident intracellular differentiation (Fig. 2D, III). Since ECs and PCs presumably produce the BM, these findings suggest the loss of a coordinated, synergistic interaction of these two cell types. Interestingly, the BM thickness in the exercised group (Fig. 2D, VI) had reverted to the limits visualized in the lean group, and the endomysium space and capillary lumen were restored to the lean phenotype. The exercised group also showed differentiated PC and EC profiles after the intervention; the trophic sarcolemma showed an evident improvement, with a significant repair of endomysium space, a normal capillary lumen, and fibroblasts located in the endomysium with sparse collagen fibers (Fig. 2D, VI). Importantly, semiquantitative analysis of capillary profiles from skeletal muscle (Fig. 2D–H) coincided with the ultrastructural characterization for each group, suggesting that exercise training following RYGB surgery was able to revert the ECM capillary profiles to the limits visualized in the healthy control group.

Figure 2.

Skeletal muscle ECM immunohistochemistry and transmission electron microscopy. Representative images (A) and quantification of collagen I (B) and III (C) staining. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 15 per group). Representative transmission electron micrographs of capillaries in skeletal muscle (D) (n = 10 per group). The small arrows in I–III pointing to the inner and outer boundaries indicate increased BM thickness (E), an abrupt loss of endomysium space, a reduction in the capillary lumen, sarcolemma (SL) atrophy, and an increased number of fibroblasts and collagen fibers. The long arrows indicate a degenerated PC or EC profile (ghosts) (F) within the BM layer. The small arrows in IV–VI point to the inner and outer boundaries of reduction of BM thickness, normal SL, repair of endomysium space, normal capillary lumen, and decreased number of fibroblasts (G) and collagen fibers (H). Pathological findings (E–H) were graded on a five-point, semiquantitative, severity-based scoring system as follows: 0 = normal capillary, 1 = changes from 1% to 25%, 2 = changes from 26% to 50%, 3 = changes from 51% to 75%, and 4 = changes from 76% to 100% of the examined tissue. #P < 0.05 for within-group comparison (vs. PRE); &P < 0.05 for within-group comparison (vs. POST3); *P < 0.05 for between-group comparison at POST9. AU, arbitrary unit; Col, collagen fibers; CTRL, control.

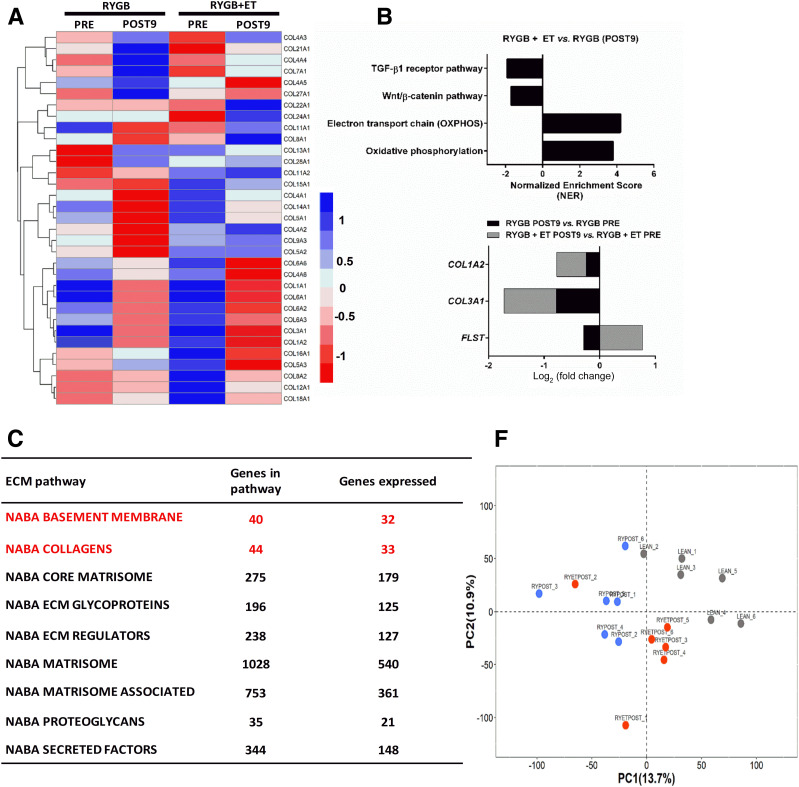

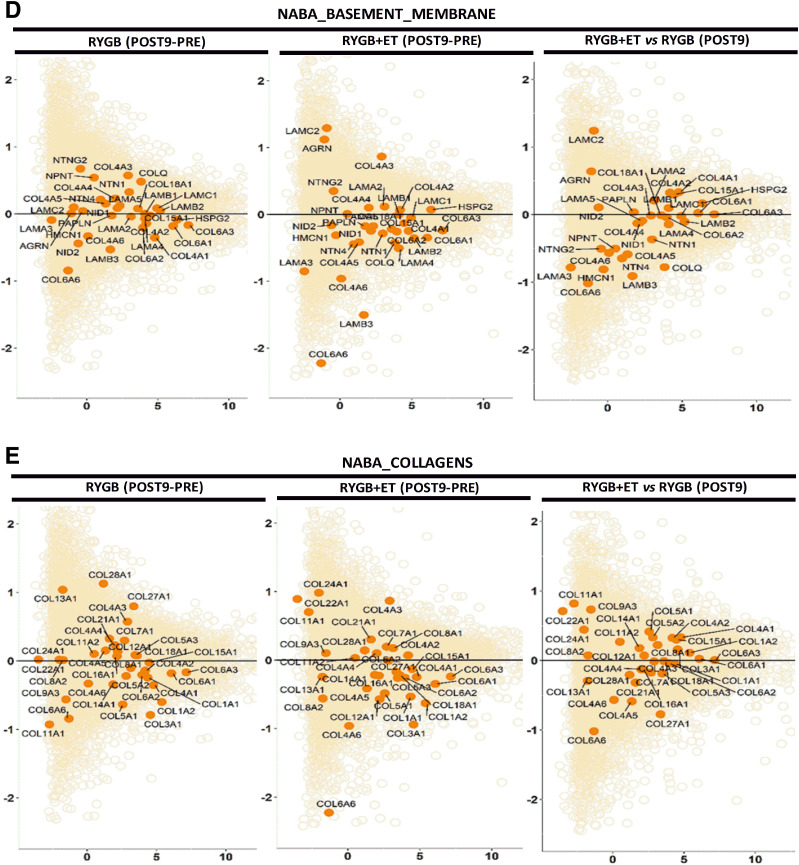

Exercise Training Following RYGB Surgery Elicits a Differential Gene Regulation in ECM Pathways in Skeletal Muscle

To investigate potential molecular mechanisms underlying these distinct phenotypes in exercised and nonexercised groups, we conducted untargeted global RNA-seq of skeletal muscle. In total, 1,566 genes belonging to nine canonical ECM-related pathways were differentially expressed after the intervention (Fig. 3A). Within ECM-related pathways, the NABA_COLLAGENS heat map output showed that exercise reduced transcription of collagen 1A1 (COL1A2) and collagen 3A1 (COL3A1), the most abundant types of collagen in skeletal muscle (30) (Fig. 3B and C). Gene set enrichment analysis further showed that exercise increased oxidative phosphorylation and electron transport chain pathways (normalized enrichment scores [NESs] of 3.51 and 4.16, respectively; FDR <0.1). Of relevance, exercise decreased Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β receptor pathways (NESs of 1.67 and 1.73, respectively; FDR <0.1) (Fig. 3B). Exercise elicited PRE to POST changes in ECM-related genes, including COL1A2, COL3A1, and FLST. Surgery alone also altered ECM-related genes, including COL1A2 and COL3A1, but not FLST (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

A: A heatmap of the top 33 collagen genes expressed shows −log2 fold change (median of FDR-adjusted P values) of the pathways with a median adjusted P < 0.1. Each column represents a single sample at PRE and POST9, and each row represents the expression of a single gene. Upregulated and downregulated genes are indicated in blue and red, respectively. B: Pathway enrichment analysis. Preranked gene set enrichment analysis (GSEApre) was applied to gene expression data from relevant comparisons to identify significantly enriched gene sets defined from the Wikipathways repository. For each comparison, the normalized pathway enrichment score is plotted on the x-axis and the names of the pathways are indicated on the y-axis. All pathways have an FDR ≤ 0.1. C: ECM-focused pathways. Nine ECM related gene sets generated in the Matrisome project (http://web.mit.edu/hyneslab/matrisome) were downloaded from the MSigDB database. The name of the ECM pathway, the number of genes within each pathway, and the number of genes expressed in our study are indicated in the Supplementary Material. D and E: Mean average plots. Each plot shows the average log2 counts per million (CPM) gene expression (x-axis) vs. log2 fold change (y-axis) of genes for each comparison listed at the top of each plot. Pathway genes are shown in dark orange and nonpathway genes are shown in light orange. The line of no change (log2 fold change = 0) is indicated in each plot. F: PCA was carried out for the lean, RYGB at POST9, and RYGB + ET at POST9 samples, using their gene expression (log2 CPM) values as input. Samples are color coded as indicated. PC1, principal component 1; PC2, principal component 2.

We also constructed mean average plots to visualize differential expression patterns of specific ECM pathway genes, contrasted to the expression of all genes from the RNA-seq analysis. Pathway genes (NABA_BASEMENT_MEMBRANES) are shown in dark orange (Fig. 3C), and the remaining genes are shown in light orange. A preponderance of pathway genes above or below the line of no differential expression (y-axis = 0) is indicative of an overall up- or downregulation of genes in the pathway. A significant decrease in pathway genes (NABA_BASEMENT_MEMBRANES) was observed only in the exercised group (PRE to POST). Likewise, a significant decrease in pathway genes (NABA_COLLAGENS) was reported only after exercise, which was supported by heat map analysis showing a decrease in COL1A2 and COL3A1 (Fig. 3C and D). Finally, we performed a PCA to compare samples on the basis of their global transcriptomic profiles. The PCA plot revealed distinct clusters of the lean, exercised, and nonexercised groups, with the exercised group more closely resembling the lean group (Fig. 3E). Collectively, RNA-seq revealed that differentially expressed ECM-related genes were more abundant and that their modulation was of a greater magnitude in the exercised group.

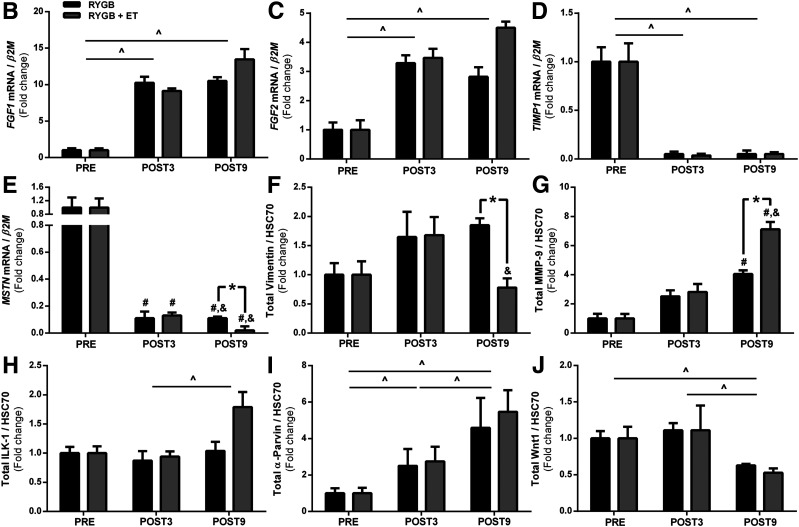

Exercise Training Following RYGB Surgery Restores TGF-β1/SMAD 2/3 Signaling

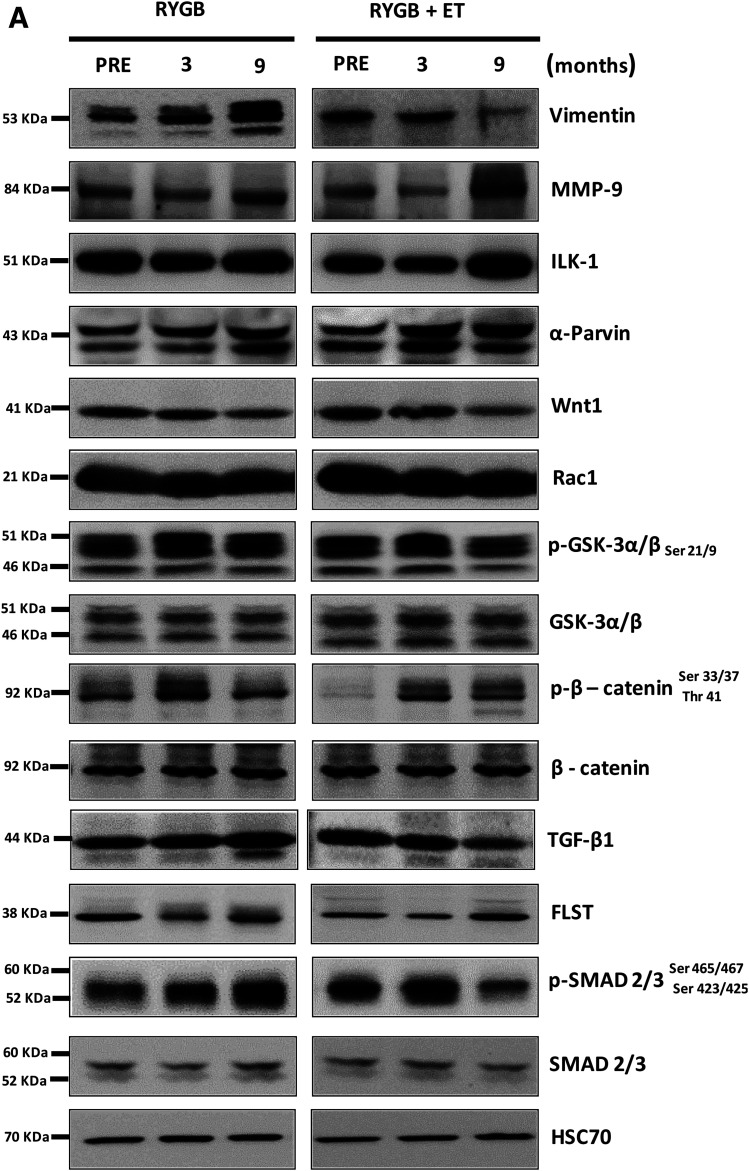

Next, we validated ECM-related targets identified by RNA-seq (Fig. 4B–P and Supplementary Fig. 2A–I). Fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) and FGF2, which are involved in the profibrogenic activity (31), were upregulated with surgery, with no influence of exercise. Vimentin, a protein also involved in fibroblast activity (32), was increased after surgery, whereas exercise reduced its expression. Tissue inhibitor matrix metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1), which inhibits ECM degradation by inhibiting matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9), a protein responsible for digesting ECM collagen in the muscle (33), was also decreased with surgery, but not exercise. Surgery also increased MMP-9 protein expression, and exercise potentiated this response. Integrin-linked kinase 1 (ILK-1) protein, a pseudokinase that binds to ECM and is implicated in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance in the muscle (9), tended to increase after exercise (P = 0.085), with no effect of surgery. α-Parvin, a protein that belongs to the ILK-1 superfamily, was augmented by surgery, but not exercise.

Figure 4.

Skeletal muscle ECM remodeling signaling. B–E: FGF1, FGF2, TIMP1, and MSTN gene expression (n = 12–15 per group). A: Representative bands of vimentin (F), MMP-9 (G), ILK-1 (H), α-parvin (I), Wnt1 (J), Rac1 (K), GSK-3α/β Ser 21/9 (L), β-catenin Ser 33/37 Thr 41 (M), TGF-β1 (N), FLST (O), and SMAD 2/3 Ser 465/467 Ser 423/425 (P) with HSC70 as a loading control (n = 12–15 per group). Phosphorylated proteins were normalized by respective total protein as well as other proteins normalized by HSC70. ^P < 0.05 for main effect of time; #P < 0.05 for within-group comparison (vs. PRE); &P < 0.05 for within-group comparison (vs. POST3); *P < 0.05 for between-group comparison at POST9.

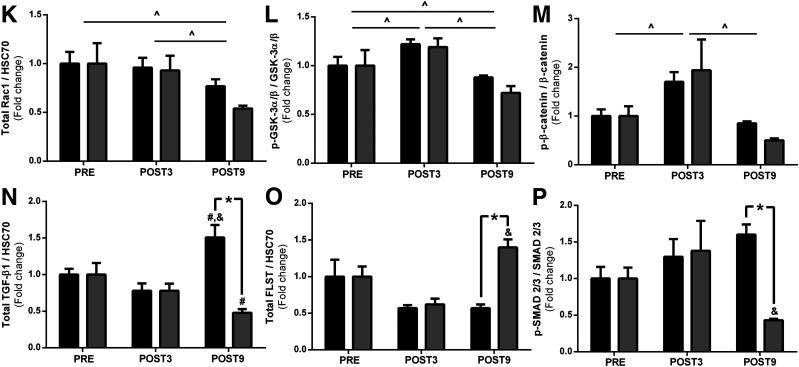

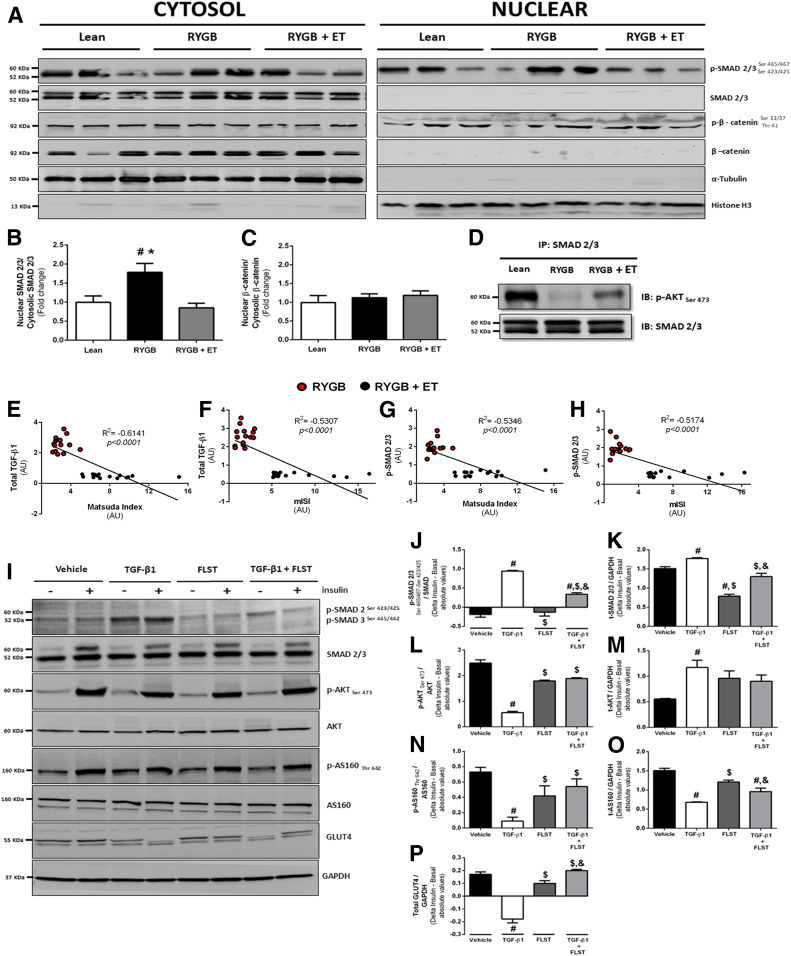

Canonical Wnt signaling regulates the expression of genes encoding ECM proteins (34,35). We found that the proto-oncogene protein Wnt-1 (Wnt1) and Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) were decreased by surgery, with no additional effect from exercise. GS kinase 3 (GSK-3) α/β and β-catenin phosphorylation (Ser 21/9 and Ser 33/37 Thr 41) were increased after surgery; no effect of exercise was observed. Total GSK-3 α/β and β-catenin contents did not change with surgery or exercise. β-catenin nuclear translocation was comparable between groups (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Protein translocation and protein-protein interaction. A–C: Representative bands of nuclear and cytosolic protein expression, SMAD phosphorylation (normalized by total SMAD 2/3), and β-catenin phosphorylation (normalized by total β-catenin) at POST9. Histone H3 and α-tubulin were blotted to confirm the subcellular fractionation efficacy (n = 10 per group). D: SMAD 2/3 and AKT Ser 473 interaction in muscle lysates from lean, RYGB, and RYGB + ET groups at POST9 (n = 10 per group). E–H: TGF-β1 and SMAD phosphorylation correlated with Matsuda ISI and mISI (Pearson correlation analysis). #P < 0.05 vs. lean; *P < 0.05 vs. RYGB + ET. I: Representative bands from C2C12 cells were treated with TGF-β1, its antagonist FLST, and a combination of both, in the presence (+) or absence (−) of insulin on SMAD 2/3 phosphorylation (J), total (t)-SMAD 2/3 (K), p-AKT (L), t-AKT (M), p-AS160 (N), t-AS160 (O), and GLUT4 content (P). For cell culture experiments, data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. #P < 0.05 vs. vehicle; $P < 0.05 vs. TGF-β1; &P < 0.05 vs. FLST. AU, arbitrary unit; IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation.

TGF-β1 signaling, an essential positive regulator of ECM expansion, was also examined. TGF-β1 expression was significantly increased with surgery and then reduced only with exercise. Interestingly, FLST, a TGF-β1 antagonist, inversely mirrored TGF-β1 responses; surgery decreased FLST expression, whereas exercise training increased it. Myostatin (MSTN) expression was downregulated by surgery, and this response was more pronounced in the exercised group. MSTN acts through SMAD 2/3 activation, which is a central signal transducer through the TGF-β1 receptor superfamily. Of relevance, SMAD 2/3 phosphorylation was exclusively decreased by exercise training, without any changes in total protein content. Because SMAD 2/3 is activated in the cytosol and then translocates into the nucleus to initiate the ECM-related transcription genes (36), we hypothesized that exercise training following RYGB surgery could also modulate SMAD 2/3 traffic to the nucleus. This was confirmed by a subcellular fractionation experiment in which SMAD 2/3 nuclear translocation was significantly lower in the exercised group (Fig. 5B).

Since elevated SMAD 2/3 activity can blunt insulin signaling by directly inhibiting AKT (Ser 473), we then evaluated protein-protein interaction by immunoprecipitation. We found that SMAD 2/3 associated with AKT (Ser 473) was inhibited after surgery (Fig. 5D), a response that was abrogated by exercise training. This finding suggests that exercise-induced SMAD 2/3 suppression results in improvements in insulin signaling through circumventing AKT inhibition. Of clinical relevance, we found significant correlations between TGF-β1 and SMAD 2/3 with mISI and Matsuda ISI after the intervention (Fig. 5E–H), supporting the hypothesis that TGF-β1/SMAD 2/3 signaling was implicated in the insulin-sensitizing effects of exercise training following RYGB surgery.

FLST Restores Impairments in Insulin Signaling Provoked by TGF-β1 In Vitro

Next, we performed in vitro experiments to confirm that FLST can restore impairments in insulin signaling provoked by TGF-β1. To better understand the cross-talk mechanisms between the TGF-β1–FLST axis and muscle insulin signaling, C2C12 myocytes were treated with TGF-β1, its antagonist FLST, and the combination of both in the presence or absence of insulin (Fig. 5J–P). Myotubes treated with TGF-β1 showed higher SMAD 2/3 phosphorylation and its protein content compared with vehicle and FLST alone. Also, FLST attenuated the effect of TGF-β1 on SMAD 2/3 phosphorylation and its total protein content. AKT (Ser 473) was blunted in the presence of TGF-β1, while treatment with FLST alone or with TGF-β1 restored this response. AS160 phosphorylation and total protein content were reduced after TGF-β1 treatment, whereas TGF-β1 combined with FLST restored AS160 phosphorylation but not its total content. Of interest, TGF-β1 treatment also led to lower GLUT4 content compared with control, which was reversed by FLST. These observations reveal that the TGF-β1/SMAD 2/3 pathway does contribute to insulin resistance through impairing the expression of key proteins involved in insulin signaling.

Discussion

This study provides evidence that skeletal muscle ECM plays a key role in promoting insulin sensitivity when exercise training is incorporated into the therapeutic regimen of women with obesity after RYGB surgery. Multiple layers of reinforcing evidence, from the muscle ultrastructure to the gene, confirm a robust change in skeletal muscle ECM remodeling toward a lean healthy phenotype in response to exercise training.

Coen et al. (4,5) were the first to show that exercise training can further enhance the effects of bariatric surgery on insulin sensitivity, a phenomenon that was associated with improvements in lipid species and mitochondrial function. Here, we show that exercise-induced increases in insulin sensitivity are mediated by a robust muscle ECM remodeling characterized by a substantial decrease in collagen I and III staining and a reduction in capillary BM thickness. Importantly, this response was only partial in the absence of exercise.

The putative mechanisms by which exercise training can modify muscle ECM are believed to be twofold: 1) an increase in MMP-9 expression, leading to ECM degradation (16), and 2) a suppression in ECM synthesis through a decrease in TGF-β1, vimentin, and p-SMAD 2/3 expression (37,38). In the current study, on the basis of untargeted and targeted approaches, we identified candidates involved in ECM expansion that were differentially modulated by exercise training. This is the case of the TGF-β1/SMAD 2/3 pathway, which is known to stimulate ECM expansion (39). In a previous investigation, TGF-β1 and its target genes were shown to be predictive of the failure to increase insulin sensitivity after exercise training in individuals at high risk of T2D (40), suggesting that this pathway is a relevant target for mitigating insulin resistance through muscle ECM modulation. Of relevance, surgery alone led to an increased TGF-β1 expression, which was suppressed by exercise. These findings were also evidenced by diminished SMAD 2/3 expression and translocation to the nucleus following exercise. Furthermore, exercise training restrained AKT inhibition by SMAD 2/3, and both TGF-β1 and SMAD 2/3 expression correlated with clinical surrogates of insulin sensitivity. These findings demonstrate the significance of the TGF-β1/SMAD 2/3 pathway in the beneficial effect of exercise training on insulin sensitivity in postbariatric surgery patients.

FLST is an important TGF-β1 antagonist that has received growing attention because of its potential therapeutic application for muscle wasting (41,42) and, more recently, muscle insulin sensitivity (43,44). Importantly, FLST, which was remarkably increased by exercise, appeared to antagonize the detrimental effect of TGF-β1/SMAD 2/3 signaling upon insulin sensitivity. These data corroborate a recent observation that FLST overexpression in the skeletal muscle increases insulin-stimulated AS160 and AKT phosphorylation (44). The current data support the idea that FLST may be an important protein secreted in response to exercise training—the so-called “exerkines” (45–47)—with the potential for treating insulin resistance in skeletal muscle.

This study is not without limitations. These findings must be confined to the main characteristics of the patients (i.e., middle-aged women with severe obesity and generally low education and economic status). Additionally, we were not able to assess muscle insulin sensitivity by the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp, although we used the Matsuda ISI, which has been shown to be an acceptable surrogate of the clamp technique (48). Although we suggest that FLST may have acted as an exerkine in this study, further arteriovenous difference experiments are necessary to validate this hypothesis. We adopted a combined aerobic and resistance exercise training program because this type of training has been consensually recommended for optimal health (49). However, it is impossible to distinguish the isolated effects of aerobic and resistance training modes on the adaptions reported herein. Furthermore, the role of exercise in modulating muscle ECM reported in this study is possibly associated with the substantial weight loss induced by bariatric surgery; whether exercise training can promote such profound changes in ECM in the absence of (or less pronounced) weight loss is unknown.

In conclusion, a combined aerobic and resistance exercise training program following bariatric surgery generates an additive effect on insulin sensitivity, and the mechanism appears to be mediated by remarkable molecular and phenotypic changes in ECM. RYGB surgery alone promoted only a partial resolution of insulin resistance and ECM remodeling, suggesting that the improvements in metabolic outcomes brought about by surgery are progressively reduced in the absence of exercise. From a mechanistic perspective, we have identified relevant candidates modulated by exercise training that may become therapeutic targets for treating skeletal muscle insulin resistance in a more generalizable context, in particular the TGF-β1/SMAD 2/3 pathway and its antagonist FLST.

Article Information

Funding. This study was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (2015/02835-8, 2016/10993-5, and 2017/01427-9). This study was also financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brasil (Finance Code 001) - Proex. The Genomics Core Facility is supported in part by Centers for Biomedical Research Excellence (NIH8 1P30-GM-118430-01) and Nutrition Obesity Research Center (NIH 2P30-DK-072476) center grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. W.S.D., H.R., I.H.M., S.Gi., F.B.B., A.L.d.S.-P., R.d.C., M.A.S., and B.G. conceived the project. W.S.D., I.H.M., S.Gi., G.D., C.L.A., S.Gh., S.S.N., H.Z., S.K.S., W.d.N., C.M.-F., W.R.T., V.L.C., R.M.P., J.P.K., and B.G. contributed to the investigation. W.S.D., H.R., I.H.M., S.Gi., G.D., C.L.A., S.Gh., S.S.N., H.Z., S.K.S., W.d.N., C.M.-F., W.R.T., V.L.C., R.M.P., F.B.B., A.L.d.S.-P., R.d.C., M.A.S., J.P.K., and B.G. contributed to the formal analysis. W.S.D., H.R., C.L.A., S.Gh., F.B.B., J.P.K., and B.G. contributed to the writing, review, and editing of the manuscript. B.G. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT02441361, clinicaltrials.gov

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.12272783.

References

- 1.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al.; STAMPEDE Investigators . Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 2017;376:641–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aminian A, Zajichek A, Arterburn DE, et al. Association of metabolic surgery with major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity. JAMA 2019;322:1271–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coen PM, Carnero EA, Goodpaster BH. Exercise and bariatric surgery: an effective therapeutic strategy. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2018;46:262–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coen PM, Menshikova EV, Distefano G, et al. Exercise and weight loss improve muscle mitochondrial respiration, lipid partitioning, and insulin sensitivity after gastric bypass surgery. Diabetes 2015;64:3737–3750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coen PM, Tanner CJ, Helbling NL, et al. Clinical trial demonstrates exercise following bariatric surgery improves insulin sensitivity. J Clin Invest 2015;125:248–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hancock CR, Han DH, Chen M, et al. High-fat diets cause insulin resistance despite an increase in muscle mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:7815–7820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holloszy JO. Skeletal muscle “mitochondrial deficiency” does not mediate insulin resistance. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:463S–466S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holloszy JO. “Deficiency” of mitochondria in muscle does not cause insulin resistance. Diabetes 2013;62:1036–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang L, Mokshagundam S, Reuter B, et al. Integrin-linked kinase in muscle is necessary for the development of insulin resistance in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes 2016;65:1590–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams AS, Kang L, Wasserman DH. The extracellular matrix and insulin resistance. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015;26:357–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson DK, Kashyap S, Bajaj M, et al. Lipid infusion decreases the expression of nuclear encoded mitochondrial genes and increases the expression of extracellular matrix genes in human skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 2005;280:10290–10297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tam CS, Covington JD, Bajpeyi S, et al. Weight gain reveals dramatic increases in skeletal muscle extracellular matrix remodeling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:1749–1757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tam CS, Chaudhuri R, Hutchison AT, Samocha-Bonet D, Heilbronn LK. Skeletal muscle extracellular matrix remodeling after short-term overfeeding in healthy humans. Metabolism 2017;67:26–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berria R, Wang L, Richardson DK, et al. Increased collagen content in insulin-resistant skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2006;290:E560–E565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mortensen SP, Winding KM, Iepsen UW, et al. The effect of two exercise modalities on skeletal muscle capillary ultrastructure in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2019;29:360–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gliemann L, Buess R, Nyberg M, et al. Capillary growth, ultrastructure remodelling and exercise training in skeletal muscle of essential hypertensive patients. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015;214:210–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murai IH, Roschel H, Dantas WS, et al. Exercise mitigates bone loss in women with severe obesity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104:4639–4650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodrigues R, Ferraz RB, Kurimori CO, et al. Low-load resistance training with blood flow restriction increases muscle function, mass and functionality in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020;72:787–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perandini LA, Sales-de-Oliveira D, Almeida DC, et al. Effects of acute aerobic exercise on leukocyte inflammatory gene expression in systemic lupus erythematosus. Exerc Immunol Rev 2016;22:64–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdul-Ghani MA, Matsuda M, Balas B, DeFronzo RA. Muscle and liver insulin resistance indexes derived from the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care 2007;30:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bechara LR, Moreira JB, Jannig PR, et al. NADPH oxidase hyperactivity induces plantaris atrophy in heart failure rats. Int J Cardiol 2014;175:499–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Araújo CC, Marques PS, Silva JD, et al. Regular and moderate aerobic training before allergic asthma induction reduces lung inflammation and remodeling. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2016;26:1360–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.R Core Team . A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. Vienna, Austria, R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available from https://www.R-project.org. Accessed 9 August 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010;26:139–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol 2014;15:R29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet 2003;34:267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Axelrod CL, Fealy CE, Mulya A, Kirwan JP. Exercise training remodels human skeletal muscle mitochondrial fission and fusion machinery towards a pro-elongation phenotype. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2019;225:e13216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davuluri G, Giusto M, Chandel R, et al. Impaired ribosomal biogenesis by noncanonical degradation of β-catenin during hyperammonemia. Mol Cell Biol 2019;39:e00451-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sylow L, Kleinert M, Richter EA, Jensen TE. Exercise-stimulated glucose uptake - regulation and implications for glycaemic control. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2017;13:133–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahdy MAA. Skeletal muscle fibrosis: an overview. Cell Tissue Res 2019;375:575–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polyakova V, Loeffler I, Hein S, et al. Fibrosis in endstage human heart failure: severe changes in collagen metabolism and MMP/TIMP profiles. Int J Cardiol 2011;151:18–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.dos Santos G, Rogel MR, Baker MA, et al. Vimentin regulates activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Commun 2015;6:6574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel SH, D’Lugos AC, Eldon ER, Curtis D, Dickinson JM, Carroll CC. Impact of acetaminophen consumption and resistance exercise on extracellular matrix gene expression in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2017;313:R44–R50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajasekaran MR, Kanoo S, Fu J, Nguyen ML, Bhargava V, Mittal RK. Age-related external anal sphincter muscle dysfunction and fibrosis: possible role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2017;313:G581–G588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horii N, Uchida M, Hasegawa N, et al. Resistance training prevents muscle fibrosis and atrophy via down-regulation of C1q-induced Wnt signaling in senescent mice. FASEB J 2018;32:3547–3559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li ZB, Kollias HD, Wagner KR. Myostatin directly regulates skeletal muscle fibrosis. J Biol Chem 2008;283:19371–19378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walton KL, Johnson KE, Harrison CA. Targeting TGF-β mediated SMAD signaling for the prevention of fibrosis. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agley CC, Rowlerson AM, Velloso CP, Lazarus NR, Harridge SD. Human skeletal muscle fibroblasts, but not myogenic cells, readily undergo adipogenic differentiation. J Cell Sci 2013;126:5610–5625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinz B. The extracellular matrix and transforming growth factor-β1: tale of a strained relationship. Matrix Biol 2015;47:54–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Böhm A, Hoffmann C, Irmler M, et al. TGF-β contributes to impaired exercise response by suppression of mitochondrial key regulators in skeletal muscle. Diabetes 2016;65:2849–2861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen JL, Walton KL, Hagg A, et al. Specific targeting of TGF-β family ligands demonstrates distinct roles in the regulation of muscle mass in health and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:E5266–E5275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sepulveda PV, Lamon S, Hagg A, et al. Evaluation of follistatin as a therapeutic in models of skeletal muscle atrophy associated with denervation and tenotomy. Sci Rep 2015;5:17535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brandt C, Hansen RH, Hansen JB, et al. Over-expression of follistatin-like 3 attenuates fat accumulation and improves insulin sensitivity in mice. Metabolism 2015;64:283–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han X, Møller LLV, De Groote E, et al. Mechanisms involved in follistatin-induced hypertrophy and increased insulin action in skeletal muscle. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019;10:1241–1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hansen J, Brandt C, Nielsen AR, et al. Exercise induces a marked increase in plasma follistatin: evidence that follistatin is a contraction-induced hepatokine. Endocrinology 2011;152:164–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansen JS, Rutti S, Arous C, et al. Circulating follistatin is liver-derived and regulated by the glucagon-to-insulin ratio. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:550–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hansen JS, Pedersen BK, Xu G, Lehmann R, Weigert C, Plomgaard P. Exercise-induced secretion of FGF21 and follistatin are blocked by pancreatic clamp and impaired in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:2816–2825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1462–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colberg SR, Albright AL, Blissmer BJ, et al.; American College of Sports Medicine; American Diabetes Association . Exercise and type 2 diabetes: American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Exercise and type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:2282–2303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]