Abstract

Coordination-driven self-assembly has been extensively employed to construct a variety of discrete structures as a bottom-up strategy. However, mechanistic understanding regarding whether self-assembly is under kinetic or thermodynamic control is less explored. To date, such mechanistic investigation has been limited to distinct, assembled structures. It still remains a formidable challenge to study the kinetic and thermodynamic behavior of self-assembly systems with multiple assembled isomers due to the lack of characterization methods. Herein, we use a stepwise strategy which combined self-recognition and self-assembly processes to construct giant metallo-supramolecules with 8 positional isomers in solution. With the help of ultrahigh-vacuum, low-temperature scanning tunneling microscopy and scanning tunneling spectroscopy, we were able to unambiguously differentiate 14 isomers on the substrate which correspond to 8 isomers in solution. Through measurement of 162 structures, the experimental probability of each isomer was obtained and compared with the theoretical probability. Such a comparison along with density functional theory (DFT) calculation suggested that although both kinetic and thermodynamic control existed in this self-assembly, the increased experimental probabilities of isomers compared to theoretical probabilities should be attributed to thermodynamic control.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Because of its intrinsic dynamic nature, self-assembly is able to organize suitable molecular components into more sophisticated supramolecular entities by virtue of noncovalent interactions.1 Typically, self-assembly involves multiple reversible processes of dissociation, association, and reorganization in which the structures or properties can be tuned by physical conditions or external stimulus.2 Studies have revealed that factors such as ligand geometry, metalions/anions, reaction time, temperature, concentration, and solvent can affect the final products of self-assembly.3 Beyond these factors, the assembled structures could also be determined by kinetic control or thermodynamic control.2b In the majority of systems, the reversible and weak noncovalent interactions favor thermodynamically controlled structures with optimum conditions.4 In contrast, kinetically controlled self-assembly can form inert structures using less labile interactions5 or metastable products that are kinetically trapped at local minima6,7 and may be further transformed to more stable products upon prolonged reaction time.7 In one of the pioneering works, Lehn and co-workers revealed that the triple helicate assembled by a tris-bipyridine ligand could progressively convert into the circulate helicate, corresponding to the switch from kinetic control to thermodynamic control.7a In Fujita’s self-assembled MnL2n polyhedra,-thermodynamic control played a predominant role when n = 6, 12, or 24. While for n > 24, the kinetic trapping is no longer negligible.6c As such, M30L60 and M48L49 assembled by the same ligand with Pd(II) were categorized as kinetically and thermodynamically controlled products, respectively.7d It is worth noting that these assemblies generally gave distinct assembled structures regarding kinetic or thermodynamic control, facilitating detailed characterization.

Supramolecular isomerism has been well studied in coordination polymers and metal–organic frameworks which highly rely on crystal engineering to confirm the structure explicitly.8 In coordination-driven self-assembly of discrete metallo-supramolecules, more attention was focused on precise control over the shape and size of assemblies.9 Through careful design, a single metallo-supramolecule rather than a mixture of isomers was obtained in individual self-assembly.10 However, isomerism sometimes still occurred, for instance, positional isomers from the unbiased arrangement of dissymmetrical building blocks,11 configurational isomers from the asymmetric chelating ligand arrangements around the metal centers,12 social and constellation isomers through different arrangement/orientation of guests encapsulated in a confined host,13 and unidentical packing modes during the crystallization process.14 Such supramolecular isomerization at the molecular level is expected to increase the complexity and diversity of supramolecular chemistry and thus has resulted in applications in molecular devices and optics.15 However, supramolecular isomerism in discrete metallo-supramolecules remains less explored compared to MOFs and polymers, perhaps due to the lack of platforms with rational, precise design and insufficient characterization by NMR,13,15 crystal engineering,12,14 ion mobility-mass spectrometry (IM-MS),10a and molecular modeling.11a,16

In the present work, we demonstrated the construction of three giant trimetallic supramolecules through the self-recognition and self-assembly of a metal–organic ligand L. As a consequence of intramolecular and intermolecular complexation, three types of metal ions were successfully incorporated into the discrete metallo-supramolecules using terpyridine (tpy)-based17 coordination chemistry to form ⟨tpy–M–tpy⟩ connectivities in a stepwise manner (Figure 1A). Because of the dissymmetrical nature of the intermediate L·M after self-recognition, eight positional isomers were formed in the self-assembly of the final supramolecules in solution (Figure 1B). In terms of large molecular weight and high complexity, it remains a formidable challenge to address whether the self-assembly of those positional isomers is under kinetic and/or thermodynamic control with conventional characterization methods. Herein, we report the combined use of ultrahigh-vacuum, low-temperature scanning tunneling microscopy (UHV-LT-STM)18 and scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS)19 to characterize the isomers at the atomic level in this complex supramolecular system. Using these methods, we investigated the contribution of thermodynamic and kinetic control in the outcome of isomer distribution.

Figure 1.

(A) Construction of three trimetallic supramolecules SA-SC through self-recognition and self-assembly. (B) Eight isomers generated solution after self-assembly.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis of Trimetallic Supramolecules.

The metal–organic tpy ligand L was synthesized with ⟨tpy–Ru(II)−tpy⟩ connectivity using a Ru(II) end-capping approach by performing a Sonogashira coupling reaction on the Ru–tpy complex (Scheme S1).20 L possesses six free tpy for self-recognition and self-assembly. In the introduction of the second type of metal ion, one equivalent of either Fe(II), Co(II), or Cr(II) was mixed with L at 80 °C to form an exclusive intermediate (L·M) through specific coordination or self-recognition. Conventional electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) first suggested formation of the proposed intermediates. The measured m/z agreed well with the molecular compositions of the intermediates, i.e., 849.81 for L·Fe, 850.56 for L·Co, and 853.06 for L·Cr at charge state 4+ (Figures S35 and S36). Here, Cr(II) was oxidized to Cr(III) by air bubbling, and an −OH group was attached to balance the increased valence.21 1H NMR was also applied to confirm the specific coordination site within the structure of the intermediate L·Fe. Two sets of signals with metal and three sets of free tpy signals were observed in L, while four sets of coordinated tpy signals and three sets of free tpy signals were assigned in L·Fe because of the loss of molecular symmetry after complexation with an additional equivalent of Fe(II). The downfield shift of the tpy–E3′5′ signal and tpy–F3′5′ signal proved that Fe(II) was selectively coordinated through self-recognition (Figure 2). Detailed assignments here were based on 2D COSY and 2D NOESY spectra (Figures S19−S22). However, the 1H NMR spectra of L·Co and L·Cr are broad (Figures S24 and S25), and unsatisfactory results were obtained for 2D NMR experiments because of the paramagnetic nature of Co(II) and Cr(III). Nevertheless, two sets of characteristic tpy signals spread out in a wide range (20–100 ppm) corresponding to the ⟨tpy–Co(II)−tpy⟩ connectivity22 were identified in the proton NMR, supporting formation of the proposed intermediate L·Co (Figure S24). We speculated that exclusive formation of the intermediate was energetically more favorable through intramolecular complexation rather than intermolecular complexation.23 In addition, those intermediates are reminiscent of folding in protein structures, resulting from conformational regulation.24 Without further purification or separation, two equivalents of Zn(II) as the third type of metal ion were added to the reaction mixture for self-assembly for 8 h at 50 °C. Among these metal ions, Zn(II) has the weakest coordination with tpy to facilitate self-assembly without disturbing the previous metal ion coordination.25c After counterion exchange and washing, three targeted metallo-supramolecules with a fractal pattern25,20b were obtained in high yield.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectra (500 MHz, 300 K) of L in CDCl3 and L·Fe in CD3CN.

Characterization of Supramolecules.

ESI-MS and traveling wave ion mobility-mass spectrometry (TWIM-MS)26 were applied to provide structural information on the final heterometallic supramolecules. Only one set of continuous charged signals was observed from ESI-MS (Figure 3A and 3C; Figure S39a) corresponding to molecular weights of 28 136, 28 155, and 28 215 Da for SA, SB, and SC, respectively. A narrow distribution of drift time for each charge state in the TWIM-MS spectra (Figure 3B and 3D; Figure S39b) suggested clean formation of discrete metallo-supramolecules with high shape persistence.

Figure 3.

ESI-MS spectra of (A) SA and (C) SB; TWIM-MS plot (m/z vs drift time) of (B) SA and (D) SB.

Furthermore, the corresponding isotope pattern measured for each charge state of the supramolecules agreed well with the theoretical one (i.e., 1335.9 for SA, 1336.8 for SB, and 1340.0 for SC at charge state 19+), which strongly supports formation of the proposed structure (Figures S40−S42). The mass spectrometry data also excluded the possibility of disassembly and reassembly of ⟨tpy–Fe(II)−tpy⟩, ⟨tpy–Co(II)−tpy⟩, or ⟨tpy–Cr(III)−tpy⟩ within the targeted metallo-supramolecules. If disassembly and reassembly occurred, it was expected to observe multiple sets of signals in mass spectrometry corresponding to different numbers (0–18) of Fe(II), Co(II), or Cr(III) in the final assembled structures. Gradient tandem mass spectrometry (gMS2)27 showed that the three supramolecules were all fully dissociated at +25 V, corresponding to a center-of-mass collision energy of 0.04 eV. This implies similar stability of these three metallo-supramolecules in the gas phase despite three different metal ions being incorporated (Figures S43−S45). Thus, the stability of the whole supramolecule is determined by the weakest ⟨tpy–Zn(II)−tpy⟩ among the three ⟨tpy–M–tpy⟩ connectivities.28

Due to each L·M having two different orientations in the self-assembly with Zn(II), the final metallo-supramolecules would generate eight isomers (Figures S47 and S48) leading to very broad NMR spectra. Nevertheless, the characteristic signals in the 1H NMR, 2D COSY, and 2D NOESY spectra of complex SA were still assigned and consistent with the proposed structure (Figures S28−S32). Diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) NMR showed the diffusion coefficient (D, m2/s) of SA to be 1.43 × 10−10, which corresponded to an experimental hydro-dynamic radius (rH) of 5.7 nm.17e,20 This also agreed with the molecular diameter obtained from modeling (r = 5.5 nm) (Figure S34).

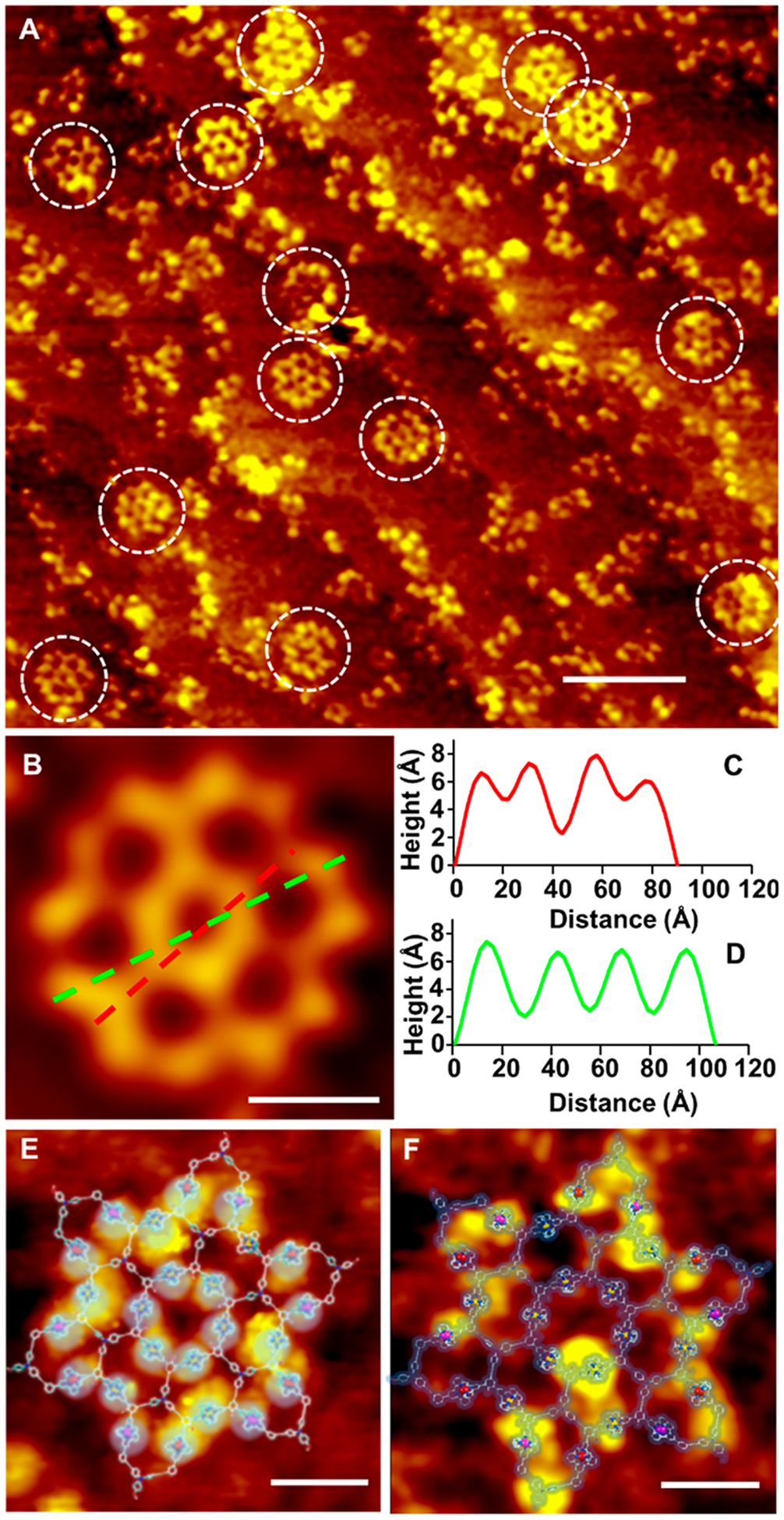

In addition to the structural characterizations described above, UHV-LT-STM was utilized to directly visualize the structures of the giant metallo-supramolecules. Working by the mechanism of quantum tunneling effects under a small bias voltage of ±1–2 V, STM effectively prevents molecular structural damage such as knock-on damage, heating effects, and radiolysis that can be introduced by other microscopy characterization methods.29 Moreover, STM investigations can provide detailed information on the topography and electronic properties at the atomic scale, making it more powerful for characterization of self-assembled structures.30 Since all three types of supramolecules are nearly identical in shape, SA was selected as a representative for STM characterization. For the STM experiments, a freshly prepared sample solution of SA (1 × 10−5 M) in acetonitrile was dropped on a Ag (111) surface, and then the sample was cooled down to ~4 K to reduce the thermal motion of the molecules, thereby a high resolution was achieved. Remarkably, intact supramolecules were observed directly in the scanned areas with some fragments absorbed on the surface (Figures 4A and S46). Note that the supramolecules can undergo disassembly via the weakest ⟨tpy–Zn(II)−tpy⟩ in a very dilute solution. With an applied positive voltage of +2 V, each ⟨tpy–M–tpy⟩ connection unit was visualized as a bright lobe in the STM image, while the overall organic backbone of the supramolecule was displayed at the negative bias voltage of −2 V (Figure 4E and 4F). The measured height (ca. 6 Å) and as well as the diameter (ca. 10.5 nm) perfectly matched the size and dimension predicted by theoretical modeling (Figure 4B–D).

Figure 4.

(A) Large-area STM image with supramolecule SA randomly anchored (scale bar 10 nm, scanning parameters Vt = 2 V, It = 130 pA). (B) Zoomed-in STM image for line-profile measurements(scale bar 2 nm, scanning parameters Vt = 2 V, It = 130 pA). (C and D) STM line profile measurements along green and red dashed lines inside the hexagon grid shown in B. Topography of SA at (E) bias voltage = +2 V (scale bar 2 nm, scanning parameters Vt = 2 V, It = 50 pA) and (F) bias voltage = −2 V (scale bar 2 nm, scanning parameters Vt = −2 V, It = 50 pA) with molecular modeling overlay.

Identification of Isomers.

With a well-visualized molecular structure by STM imaging, another important question regarding the existence of isomers still remained. As mentioned earlier, the intermediate L·M is dissymmetrical in chemical composition, and it could flip over during the self-assembly with Zn(II), leading to formation of 8 positional isomers with different orientations of Ru vs Fe in solution (Figures S47 and S48). Identification of those positional isomers is extremely challenging using conventional characterization methods, e.g., mass spectrometry, NMR, and X-ray diffraction. Therefore, scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS) was employed here to probe the local density of states (LDOS) for each metal junction to differentiate these isomers at the atomic scale.19 Notably, 14 positional isomers are expected on the substrate (Figure 5A) because the two sides of each single molecule are no longer identical when depositing the sample solution on the surface of Ag (111) for STS measurement. To avoid confusion, those pairs of isomers with relatively the same positions of Ru vs Fe while two sides of molecules are considered the same type of isomers when doing the statistic calculation discussed below. In addition, the probability of the pair of isomers regarding the different sides of the same type of supramolecule was found to be equal on the substrate (Figure S61), further supporting our classification for isomer types as reasonable.

Figure 5.

(A) Fourteen isomers generated on substrate, and corresponding 8 isomers in solution, which were labeled a–h. (B, E, H, K) STM images of four isomers of SA determined by STS (scanning parameters Vt = 2.5 V, It = 48 pA). (C, F, I, L) dI/dV − V tunneling spectroscopy data of Fe(II) (blue) corresponding to the supramolecules shown in B, E, H, K. (D, G, J, M) dI/dV − V tunneling spectroscopy data of Ru(II) (red) corresponding to the supramolecules shown in B, E, H, K. (N) Histogram of experimental and theoretical probability (PE and PT) for eight isomers in solution after measuring 162 supramolecules. (O) Histogram of relative deviation δ of eight isomers in solution calculated from experimental and theoretical probabilities (δ = [(PE − PT)/PT]).

We first measured the LDOS of the metal junctions of a reference molecule G5,20b which contains only one type of metal ion Ru(II) in its outermost ring. The obtained STS data in a single molecule showed a distinct average band gap of 2.8 eV (Figure S49), which later served as the reference to identify ⟨tpy–Ru(II)−tpy⟩. As a following step, the STS data was collected for all 12 metal junctions in the outermost ring of a single SA supramolecule. After a careful analysis of the data and classifying the values into two groups, an average 2.8 eV band gap was observed for six metal junctions which could be assigned to ⟨tpy–Ru(II)−tpy⟩ according to the reference (Figure S49); meanwhile, an average band gap of 2.4 eV was found for the other six lobes, corresponding to ⟨tpy–Fe(II)−tpy⟩ (Figure 5B–M). As such, we are able to differentiate each Fe(II) from Ru(II) based on the band gap in a single molecule and successively determine the type of isomers out of the 14 possible on the substrate (Figure 5B, 5E, 5H, and 5K).

Such STS measurements were extended to a total of 162 supramolecules (Figures S50−S57), which allowed us to characterize all 14 isomers on the Ag (111) surface (Figures 5B–M and S58) for distribution analysis. A subsequent statistical study was performed to investigate the experimental and theoretical probability distributions. Overall, the experimental probabilities (PE) basically followed the trend of the theoretical probabilities (PT) (examined by chi-square test for independence, Tables S1−S3) but displayed variations from isomers (Figure 5N). It should be noted that PT is calculated mathematically (Figure S59) and is primarily viewed as the result of self-assembly under kinetic control. To better present the variations between PE and PT, we calculated the relative deviation δ using the formula δ = [(PE − PT)/PT] (Figure S60), and the results were plotted in a histogram as shown in Figure 5O. Isomers a and h have the same PT of 0.0313, but experimental results showed an opposite trend, which leads to a negative δ value of −0.41 for isomer a and the highest δ value of +1.77 for isomer h. Meanwhile, isomers b, c, and f all showed negative δ values, and isomers d, e, and g showed positive δ values. These results implied that the second intramolecular complexation might not be dominated by kinetic control only; thermodynamic control also played an important role, which leads to an energy-biased isomer distribution.

Considering that the difference only came from the relative position of Ru vs Fe in the outermost ring in the chemical structure of isomers a–h, we proposed that the system could be energy favored when the same kinds of metals on the outer layer were neighboring on adjacent ligands. In other words, the total energy of the eight isomers should follow such a trend a > b, c, f > d, e, g > h based on the increasing number of the same neighboring metal ions on adjacent ligands (Figure S48). Our hypothesis was further supported by theoretical calculations, in which density functional theory (DFT) was applied to calculate the total energy of each isomer using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) code with the Hubbard U (DFT +U) corrections.31 Note that only metal ions in the isomers were extracted to simplify the calculation (Figure S1). As shown in Table 1, isomer a has the highest total energy of −12.36 eV compared to the lowest one of −18.28 eV for isomer h, which is suggested as the thermodynamically controlled product among 8 isomers. Also, the energy levels of other isomers are also in agreement with our proposed trend. At this point, we can conclude that the generation of these positional isomers was determined by kinetic and thermodynamic controls simultaneously, while thermodynamic control might play a more predominant role for the isomers with increased probabilities compared to theoretical probabilities. We speculated that the ligands could initially self-assemble with Zn(II) to form the kinetically stable isomers based on mathematical statistics; then thermodynamic control enabled the self-assembly to rearrange the distribution and enhanced formation of the more energy-favored structures.32

Table 1.

Total Energy (eV) of Eight Isomers Calculated from DFT

| isomer | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| energy | −12.36 | −13.17 | −13.03 | −16.87 | −16.06 | −12.71 | −18.13 | −18.28 |

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we successfully constructed a series of trimetallic supramolecules in one pot using the strategy of self-recognition and self-assembly. Through self-recognition, Fe(II), Co(II), or Cr(III) selectively coordinated with the preorganized metal–organic ligand to form exclusive intermediates. The subsequent self-assembly with the weakly coordinating metal ion Zn(II) afforded the final supramolecules SA−SC with more diversity through formation of 8 positional isomers. The intermediates and the supramolecules were well characterized by mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy. SA was directly visualized using UHV-LT-STM, and all 8 isomers in solution (corresponding to 14 isomers on substrate) were successfully identified using STS to probe the local chemical environment with the LDOS at the atomic level. More importantly, the occurrence of supramolecular isomerism in our system was found to be determined by thermodynamic and kinetic control collaboratively using a statistical study and DFT calculation. Also, their contributions were quantitatively understood through the deviation between the theoretical probability and the experimental probability measured from the STS method we developed. Therefore, this study demonstrates that we are able to study the kinetic and thermodynamic features of supramolecular isomerism at the single molecular level in a complicated system. In addition, those trimetallic metallo-supramolecules may introduce metal-dependent properties and offer potential opportunities for future applications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (R01GM128037). Use of the Center for Nanoscale Materials, an Office of Science user facility, was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The authors thank Dr. Ethan A. Hill (University of Chicago) for the comments and suggestions and Molecular Scale Lab for mass spectrometry characterization.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications Web site. The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.0c03459.

Synthetic details; ligands and complexes characterization including 1H NMR, 13C NMR, 2D COSY, 2D NOESY, ESI-MS, TWIM-MS, STM, and STS spectra (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/jacs.0c03459

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Lei Wang, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620, United States.

Bo Song, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620, United States;.

Yiming Li, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620, United States.

Lele Gong, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of North Texas, Denton, Texas 76203, United States.

Xin Jiang, State Key Laboratory of Supramolecular Structure and Materials, College of Chemistry, Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin 130012, China.

Ming Wang, State Key Laboratory of Supramolecular Structure and Materials, College of Chemistry, Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin 130012, China;.

Shuai Lu, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620, United States; College of Chemistry, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, China.

Xin-Qi Hao, College of Chemistry, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, China;.

Zhenhai Xia, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of North Texas, Denton, Texas 76203, United States;.

Yuan Zhang, Nanoscience and Technology Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Lemont, Illinois 60439, United States; Department of Physics, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Virginia 23529, United States;.

Saw Wai Hla, Nanoscience and Technology Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Lemont, Illinois 60439, United States;.

Xiaopeng Li, Department of Chemistry, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620, United States;.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Philp D; Stoddart JF Self-Assembly in Organic Synthesis. Synlett 1991, 1991, 445–458. [Google Scholar]; (b) Davis AV; Yeh RM; Raymond KN Supramolecular Assembly Dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2002, 99, 4793–4796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lehn J-M From Supramolecular Chemistry Towards Constitutional Dynamic Chemistry and Adaptive Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev 2007, 36, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) McConnell AJ; Wood CS; Neelakandan PP; Nitschke JR Stimuli-Responsive Metal–Ligand Assemblies. Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 7729–7793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu L; Lyu G; Liu C; Jiang F; Yuan D; Sun Q; Zhou K; Chen Q; Hong M Controllable Reassembly of a Dynamic Metallocage: From Thermodynamic Control to Kinetic Control. Chem. - Eur. J 2017, 23, 456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Hasenknopf B; Lehn J-M; Boumediene N; Dupont-Gervais A; Van Dorsselaer A; Kneisel B; Fenske D Self-Assembly of Tetra- and Hexanuclear Circular Helicates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 10956–10962. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stephenson A; Argent SP; Riis-Johannessen T; Tidmarsh IS; Ward MD Structures and Dynamic Behavior of Large Polyhedral Coordination Cages: An Unusual Cage-to-Cage Interconversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 858–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bolliger JL; Ronson TK; Ogawa M; Nitschke JR Solvent Effects Upon Guest Binding and Dynamics of a FeII4L4 Cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 14545–14553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xie T-Z; Endres KJ; Guo Z; Ludlow JM; Moorefield CN; Saunders MJ; Wesdemiotis C; Newkome GR Controlled Interconversion of Superposed-Bistriangle, Octahedron, and Cuboctahedron Cages Constructed Using a Single, Terpyridinyl-Based Polyligand and Zn2+. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 12344–12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang T; Zhou L-P; Guo X-Q; Cai L-X; Sun Q-F Adaptive Self-Assembly and Induced-Fit Transformations of Anion-Binding Metal-Organic Macrocycles. Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 15898–15906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wang L; Zhang Z; Jiang X; Irvin JA; Liu C; Wang M; Li X Self-Assembly of Tetrameric and Hexameric Terpyridine-Based Macrocycles Using Cd(II), Zn(II), and Fe(II). Inorg. Chem 2018, 57, 3548–3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Hasenknopf B; Lehn J-M; Kneisel BO; Baum G; Fenske D Self-Assembly of a Circular Double Helicate. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 1996, 35, 1838–1840. [Google Scholar]; (b) Leininger S; Fan J; Schmitz M; Stang PJ Archimedean Solids: Transition Metal Mediated Rational Self-Assembly of Supramolecular-Truncated Tetrahedra. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2000, 97, 1380–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sun Q-F; Iwasa J; Ogawa D; Ishido Y; Sato S; Ozeki T; Sei Y; Yamaguchi K; Fujita M Self-Assembled M24L48 Polyhedra and Their Sharp Structural Switch Upon Subtle Ligand Variation. Science 2010, 328, 1144–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Ibukuro F; Kusukawa T; Fujita M A Thermally Switchable Molecular Lock. Guest-Templated Synthesis of a Kinetically Stable Nanosized Cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 8561–8562. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chepelin O; Ujma J; Barran PE; Lusby PJ Sequential, Kinetically Controlled Synthesis of Multicomponent Stereoisomeric Assemblies. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 4194–4197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xie T-Z; Liao S-Y; Guo K; Lu X; Dong X; Huang M; Moorefield CN; Cheng SZD; Liu X; Wesdemiotis C; Newkome GR Construction of a Highly Symmetric Nanosphere Via a One-Pot Reaction of a Tristerpyridine Ligand with Ru(II). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 8165–8168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Paraschiv V; Crego-Calama M; Ishi-i T; Padberg CJ; Timmerman P; Reinhoudt DN Molecular “Chaperones” Guide the Spontaneous Formation of a 15-Component Hydrogen-Bonded Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 7638–7639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tashiro S; Tominaga M; Kusukawa T; Kawano M; Sakamoto S; Yamaguchi K; Fujita M PdII-Directed Dynamic Assembly of a Dodecapyridine Ligand into End-Capped and Open Tubes: The Importance of Kinetic Control in Self-Assembly. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2003, 42, 3267–3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fujita D; Ueda Y; Sato S; Yokoyama H; Mizuno N; Kumasaka T; Fujita M Self-Assembly of M30L60 Icosidodecahedron. Chem. 2016, 1, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Hasenknopf B; Lehn J-M; Boumediene N; Leize E; Van Dorsselaer A Kinetic and Thermodynamic Control in Self-Assembly: Sequential Formation of Linear and Circular Helicates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1998, 37, 3265–3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hori A; Yamashita K-I; Fujita M Kinetic Self-Assembly: Selective Cross-Catenation of Two Sterically Differentiated PdII-Coordination Rings. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2004, 43, 5016–5019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yamanaka M; Yamada Y; Sei Y; Yamaguchi K; Kobayashi K Selective Formation of a Self-Assembling Homo or Hetero Cavitand Cage Via Metal Coordination Based on Thermodynamic or Kinetic Control. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 1531–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fujita D; Ueda Y; Sato S; Mizuno N; Kumasaka T; Fujita M Self-Assembly of Tetravalent Goldberg Polyhedra from 144 Small Components. Nature 2016, 540, 563–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Moulton B; Zaworotko MJ From Molecules to Crystal Engineering: Supramolecular Isomerism and Polymorphism in Network Solids. Chem. Rev 2001, 101, 1629–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang J-P; Huang X-C; Chen X-M Supramolecular Isomerism in Coordination Polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev 2009, 38, 2385–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Karmakar A; Paul A; Pombeiro AJL Recent Advances on Supramolecular Isomerism in Metal Organic Frameworks. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 4666–4695. [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Chakrabarty R; Mukherjee PS; Stang PJ Supramolecular Coordination: Self-Assembly of Finite Two- and Three-Dimensional Ensembles. Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 6810–6918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu Y; Hu C; Comotti A; Ward MD Supramolecular Archimedean Cages Assembled with 72 Hydrogen Bonds. Science 2011, 333, 436–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ayme J-F; Beves JE; Campbell CJ; Leigh DA Template Synthesis of Molecular Knots. Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 1700–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Schultz A; Li X; Barkakaty B; Moorefield CN; Wesdemiotis C; Newkome GR Stoichiometric Self-Assembly of Isomeric, Shape-Persistent, Supramacromolecular Bowtie and Butterfly Structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 7672–7675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu H-J; Liu Z-M; Yin S-Y; Wu K; Wei Z-W; Pan M Cage-Opening Supramolecular Isomerism in Cu(II) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. Commun 2017, 86, 223–226. [Google Scholar]; (c) Samantray S; Bandi S; Chand DK Design of a Double-Decker Coordination Cage Revisited to Make New Cages and Exemplify Ligand Isomerism. Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2019, 15, 1129–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) Zhao L; Northrop BH; Zheng Y-R; Yang H-B; Lee HJ; Lee YM; Park JY; Chi K-W; Stang PJ Self-Selection in the Self-Assembly of Isomeric Supramolecular Squares from Unsymmetrical Bis(4-Pyridyl)Acetylene Ligands. J. Org. Chem 2008, 73, 6580–6586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Song B; Kandapal S; Gu J; Zhang K; Reese A; Ying Y; Wang L; Wang H; Li Y; Wang M; Lu S; Hao X-Q; Li X; Xu B; Li X Self-Assembly of Polycyclic Supramolecules Using Linear Metal-Organic Ligands. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 4575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lewis JEM; Tarzia A; White AJP; Jelfs KE Conformational Control of Pd2L4 Assemblies with Unsymmetrical Ligands. Chem. Sci 2020, 11, 677–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Wu H-B; Wang Q-M Construction of Heterometallic Cages with Tripodal Metalloligands. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2009, 48, 7343–7345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Meng W; Breiner B; Rissanen K; Thoburn JD; Clegg JK; Nitschke JR A Self-Assembled M8L6 Cubic Cage That Selectively Encapsulates Large Aromatic Guests. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 3479–3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhou X-P; Liu J; Zhan S-Z; Yang J-R; Li D; Ng K-M; Sun RW-Y; Che C-M A High-Symmetry Coordination Cage from 38- or 62-Component Self-Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 8042–8045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) Shivanyuk A; Rebek J Social Isomers in Encapsulation Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 12074–12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kobayashi K; Ishii K; Sakamoto S; Shirasaka T; Yamaguchi K Guest-Induced Assembly of Tetracarboxyl-Cavitand and Tetra(3-Pyridyl)-Cavitand into a Heterodimeric Capsule Via Hydrogen Bonds and CH–Halogen and/or CH–π Interaction: Control of the Orientation of the Encapsulated Guest. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 10615–10624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shivanyuk A; Rebek J Jr. Isomeric Constellations of Encapsulation Complexes Store Information on the Nanometer Scale. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2003, 42, 684–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yamanaka M; Shivanyuk A; Rebek J Stereochemistry in Self-Assembled Encapsulation Complexes: Constellational Isomerism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2004, 101, 2669–2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ajami D; Theodorakopoulos G; Petsalakis ID; Rebek J Jr. Social Isomers of Picolines in a Small Space. Chem. - Eur. J 2013, 19, 17092–17096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Abourahma H; Moulton B; Kravtsov V; Zaworotko MJ Supramolecular Isomerism in Coordination Compounds: Nanoscale Molecular Hexagons and Chains. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 9990–9991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) du Plessis M; Barbour LJ Supramolecular Isomerism and Solvatomorphism in a Novel Coordination Compound. Dalton. Trans 2012, 41, 3895–3898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Timmerman P; Verboom W; van Veggel FCJM; van Duynhoven JPM; Reinhoudt DN A Novel Type of Stereo-isomerism in Calix[4]Arene-Based Carceplexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 1994, 33, 2345–2348. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tucci FC; Rudkevich DM; Rebek J Stereochemical Relationships between Encapsulated Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 4928–4929. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kobayashi K; Ishii K; Yamanaka M Orientational Isomerism and Binding Ability of Nonsymmetrical Guests Encapsulated in a Self-Assembling Heterodimeric Capsule. Chem. - Eur. J 2005, 11, 4725–4734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Tsuzuki S; Uchimaru T; Mikami M; Kitagawa H; Kobayashi K Mechanism of Orientational Isomerism of Unsymmetrical Guests in a Heterodimeric Capsule: Analysis by Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 5335–5341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Wild A; Winter A; Schlütter F; Schubert US Advances in the Field of Π-Conjugated 2,2′:6′,2″-Terpyridines. Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 1459–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chakraborty S; Newkome GR Terpyridine-Based Metallosupramolecular Constructs: Tailored Monomers to Precise 2d-Motifs and 3d-Metallocages. Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 3991–4016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fu J-H; Lee Y-H; He Y-J; Chan Y-T Facile Self-Assembly of Metallo-Supramolecular Ring-in-Ring and Spiderweb Structures Using Multivalent Terpyridine Ligands. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2015, 54, 6231–6235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang S-Y; Fu J-H; Liang Y-P; He Y-J; Chen Y-S; Chan Y-T Metallo-Supramolecular Self-Assembly of a Multicomponent Ditrigon Based on Complementary Terpyridine Ligand Pairing. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 3651–3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang Z; Wang H; Wang X; Li Y; Song B; Bolarinwa O; Reese RA; Zhang T; Wang X-Q; Cai J; Xu B; Wang M; Liu C; Yang H-B; Li X Supersnowflakes: Stepwise Self-Assembly and Dynamic Exchange of Rhombus Star-Shaped Supramolecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 8174–8185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).(a) Wang H; Li Y; Yu H; Song B; Lu S; Hao X-Q; Zhang Y; Wang M; Hla S-W; Li X Combining Synthesis and Self-Assembly in One Pot to Construct Complex 2d Metallo-Supra-molecules Using Terpyridine and Pyrylium Salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 13187–13195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang Y; Calupitan JP; Rojas T; Tumbleson R; Erbland G; Kammerer C; Ajayi TM; Wang S; Curtiss LA; Ngo AT; Ulloa SE; Rapenne G; Hla SW A Chiral Molecular Propeller Designed for Unidirectional Rotations on a Surface. Nat. Commun 2019, 10, 3742–3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Feenstra RM Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy. Surf. Sci 1994, 299–300, 965–979. [Google Scholar]; (b) Xue Y; Datta S; Hong S; Reifenberger R; Henderson JI; Kubiak CP Negative Differential Resistance in the Scanning-Tunneling Spectroscopy of Organic Molecules. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 1999, 59, R7852–R7855. [Google Scholar]; (c) Venema LC; Janssen JW; Buitelaar MR; Wildöer JWG; Lemay SG; Kouwenhoven LP; Dekker C Spatially Resolved Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy on Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 2000, 62, 5238–5244. [Google Scholar]; (d) Li Z; Li Y; Zhao Y; Wang H; Zhang Y; Song B; Li X; Lu S; Hao X-Q; Hla S-W; Tu Y; Li X Synthesis of Metallopolymers and Direct Visualization of the Single Polymer Chain. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 6196–6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Song B; Kandapal S; Gu J; Zhang K; Reese A; Ying Y; Wang L; Wang H; Li Y; Wang M; Lu S; Hao X-Q; Li X; Xu B; Li X Self-Assembly of Polycyclic Supramolecules Using Linear Metal-Organic Ligands. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 4575–4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang L; Liu R; Gu J; Song B; Wang H; Jiang X; Zhang K; Han X; Hao X-Q; Bai S; Wang M; Li X; Xu B; Li X Self-Assembly of Supramolecular Fractals from Generation 1 to 5. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 14087–14096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Vaidyanathan VG; Nair BU Nucleobase Oxidation of DNA by (Terpyridyl)Chromium(III) Derivatives. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2004, 2004, 1840–1846. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zare D; Doistau B; Nozary H; Besnard C; Guénée L; Suffren Y; Pelé A-L; Hauser A; Piguet C CrIII as an Alternative to RuII in Metallo-Supramolecular Chemistry. Dalton. Trans 2017, 46, 8992–9009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).(a) Chow HS; Constable EC; Housecroft CE; Kulicke KJ; Tao Y When Electron Exchange Is Chemical Exchange–Assignment of 1H NMR Spectra of Paramagnetic Cobalt(II)-2,2′:6′,2″-Terpyridine Complexes. Dalton. Trans 2005, 2, 236–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Constable EC; Harris K; Housecroft CE; Neuburger M; Zampese JA Turning {M(Tpy)2}N+ Embraces and CH⋯Π Interactions on and Off in Homoleptic Cobalt(II) and Cobalt(III) Bis(2,2′:6′,2″-Terpyridine) Complexes. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 2949–2961. [Google Scholar]

- (23).(a) Field MJ; May BL; Clements P; Tsanaktsidis J; Easton CJ; Lincoln SF Intramolecular Complexation in Modified B-Cyclodextrins: A Preparative, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Ph Titration Study. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans.1 2000, 0, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]; (b) Piguet C Five Thermodynamic Describers for Addressing Serendipity in the Self-Assembly of Polynuclear Complexes in Solution. Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 6209–6231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ihara T; Ohura H; Shirahama C; Furuzono T; Shimada H; Matsuura H; Kitamura Y Metal Ion-Directed Dynamic Splicing of DNA through Global Conformational Change by Intramolecular Complexation. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 6640–6648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).(a) Jennings P; Wright P Formation of a Molten Globule Intermediate Early in the Kinetic Folding Pathway of Apomyoglobin. Science 1993, 262, 892–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dobson CM;Šali A; Karplus M Protein Folding: A Perspective from Theory and Experiment. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1998, 37, 868–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhang M; Abrams C; Wang L; Gizzi A; He L; Lin R; Chen Y; Loll PJ; Pascal JM; Zhang J -f. Structural Basis for Calmodulin as a Dynamic Calcium Sensor. Structure 2012, 20, 911–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).(a) Newkome GR; Wang P; Moorefield CN; Cho TJ; Mohapatra PP; Li S; Hwang S-H; Lukoyanova O; Echegoyen L; Palagallo JA; Iancu V; Hla S-W Nanoassembly of a Fractal Polymer: A Molecular ″Sierpinski Hexagonal Gasket″. Science 2006, 312, 1782–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiang Z; Li Y; Wang M; Liu D; Yuan J; Chen M; Wang J; Newkome GR; Sun W; Li X; Wang P Constructing High-Generation Sierpiński Triangles by Molecular Puzzling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 11450–11455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang L; Song B; Khalife S; Li Y; Ming L-J; Bai S; Xu Y; Yu H; Wang M; Wang H; Li X Introducing Seven Transition Metal Ions into Terpyridine-Based Supramolecules: Self-Assembly and Dynamic Ligand Exchange Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 1811–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).(a) Hoaglund-Hyzer CS; Counterman AE; Clemmer DE Anhydrous Protein Ions. Chem. Rev 1999, 99, 3037–3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kruve A; Caprice K; Lavendomme R; Wollschläger JM; Schoder S; Schröder HV; Nitschke JR; Cougnon FBL; Schalley CA Ion-Mobility Mass Spectrometry for the Rapid Determination of the Topology of Interlocked and Knotted Molecules. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 11324–11328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).(a) Li X; Chan Y-T; Newkome GR; Wesdemiotis C Gradient Tandem Mass Spectrometry Interfaced with Ion Mobility Separation for the Characterization of Supramolecular Architectures. Anal. Chem 2011, 83, 1284–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Song B; Zhang Z; Wang K; Hsu C-H; Bolarinwa O; Wang J; Li Y; Yin G-Q; Rivera E; Yang H-B; Liu C; Xu B; Li X Direct Self-Assembly of a 2D and 3D Star of David. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 5258–5262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).(a) Ludlow JM III; Guo Z; Schultz A; Sarkar R; Moorefield CN; Wesdemiotis C; Newkome GR Group 8 Metallomacrocycles − Synthesis, Characterization, and Stability. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2015, 2015, 5662–5668. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chakraborty S; Hong W; Endres KJ; Xie T-Z; Wojtas L; Moorefield CN; Wesdemiotis C; Newkome GR Terpyridine-Based, Flexible Tripods: From a Highly Symmetric Nanosphere to Temperature-Dependent, Irreversible, 3D Isomeric Macromolecular Nanocages. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 3012–3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).(a) Ugurlu O; Haus J; Gunawan AA; Thomas MG; Maheshwari S; Tsapatsis M; Mkhoyan KA Radiolysis to Knock-on Damage Transition in Zeolites under Electron Beam Irradiation. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 2011, 83, 113408. [Google Scholar]; (b) Susi T; Kotakoski J; Arenal R; Kurasch S; Jiang H; Skakalova V; Stephan O; Krasheninnikov AV; Kauppinen EI; Kaiser U; Meyer JC Atomistic Description of Electron Beam Damage in Nitrogen-Doped Graphene and Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 8837–8846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Egerton RF Mechanisms of Radiation Damage in Beam-Sensitive Specimens, for Tem Accelerating Voltages between 10 and 300 Kv. Microsc. Res. Tech 2012, 75, 1550–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).(a) De Feyter S; De Schryver FC Two-Dimensional Supramolecular Self-Assembly Probed by Scanning Tunneling Microscopy. Chem. Soc. Rev 2003, 32, 139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) De Feyter S; De Schryver FC Self-Assembly at the Liquid/Solid Interface: Stm Reveals. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 4290–4302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stepanenko V; Würthner F Hierarchical Self-Assembly of Cyclic Dye Arrays into Two-Dimensional Honeycomb Nanonetworks. Small 2008, 4, 2158–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).(a) Hirunsit P Electroreduction of Carbon Dioxide to Methane on Copper, Copper–Silver, and Copper–Gold Catalysts: A DFT Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 8262–8268. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lin C-Y; Zhang L; Zhao Z; Xia Z Design Principles for Covalent Organic Frameworks as Efficient Electrocatalysts in Clean Energy Conversion and Green Oxidizer Production. Adv. Mater 2017, 29, 1606635–1606642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).King RB; Silaghi-Dumitrescu I; Şovago I Kinetic Versus Thermodynamic Isomers of the Deltahedral Cobaltadicarbaboranes. Inorg. Chem 2009, 48, 5088–5095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.