Abstract

Introduction: Family planning (FP) is a key element in the conduct of research and is essential in managing family sizes. Although fishing communities (FCs) are targeted populations for HIV prevention research, their FP practices are poorly understood. We explored barriers and facilitators of FP use in FCs of Lake Victoria in Uganda. Methods: We employed a mixed-methods approach comprising a cross-sectional survey, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions in 2 FCs. Multivariable logistic regression was used to analyze quantitative data and a thematic approach to generate themes from the qualitative data. Results: Up to 1410 individuals participated in the survey and 47 in the qualitative study. Just over a third (35.6%) used FP. The most commonly used methods were condoms, pills, and injectables. In Kigungu community, participants whose religion was Anglican and Muslim were more likely to use FP than Catholics (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.45; 95% CI 1.05-1.99 and aOR 1.45; 95% CI 1.05-2.07, respectively). Participants were more likely to use FP if they had satisfactory FP knowledge compared to those with no satisfactory FP knowledge (aOR 1.79; 95% CI 1.23-2.61), or if they were married compared to their single counterparts (aOR 1.84; 95% CI 1.32-2.57). In both communities, participants were more likely to use FP if they had 2 or more sexual partners in the past 12 months than those with less than 2 sexual partners (aOR 1.41 95% CI 1.07-1.87 and aOR 2.60; 95% CI 1.36-4.97). Excessive bleeding and delayed fecundity; fertility desire; gender preferences of children; method stock outs and lack of FP trained personnel constituted barriers to FP use. There were also cultural influences in favor of large families. Conclusion: FP use in FCs is suboptimal. Barriers of FP use were mainly biomedical, religious, social, and cultural, which underscores a need for FP education and strengthening of FP service provision in FCs.

Keywords: family planning, facilitators, barriers, fishing community

Introduction

Family planning (FP) empowers people to make informed choices about the number and timing of births.1 It is the cornerstone for achieving the Third United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal aiming at universal health coverage, including financial risk protection and access to quality essential health care services.2 Unintended pregnancies pose a health risk and carry associated healthcare costs, including the cost of antenatal and delivery services, as well as postpartum care for the mother, and routine healthcare for the infant.3 The risk of illness and death of pregnant women and their children is related to parity, inversely related to pregnancy spacing and the timing of first pregnancies.4 Short pregnancy intervals also predispose to childhood malnutrition. By averting unintended births and timing births properly, countries reap health and economic benefits through reduced pressure on the environment, agriculture, and other social services.5 FP reduces the number of maternal and infant complications related to birth and it empowers women, allowing them to make choices around pursuing additional education and gainful employment opportunities.2 Condoms are good contraception choices in persons living with HIV infection as they are essential in reduction of transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Despite these benefits, the number of people using FP in the low- and middle-income countries is small with approximately 24% of all women in sub-Saharan Africa having an unmet need for FP.6-10 The Ministry of Health launched Uganda’s FP Costed Implementation Plan (CIP) in 2014, with the aim of increasing the use of modern methods of FP from 26% of married women in 2011 to 50% by 2020.11 According to the 2016 Demographic and Health Survey data, 67% of currently married women had a demand for FP; 27% wanted to limit births and 40% wanted to space births while only 39% reported using contraception.10 These indices tend to be higher and worse off in some subpopulations. Fishing communities (FCs) in Uganda make a great contribution to the country’s economy.12 However, they are some of the subpopulations with an overwhelming need for sexual and reproductive health services.13,14 Recent data from a study that was conducted in FCs of Uganda showed that only 35% of the participants were using FP.15 Furthermore, FCs are among the high-risk populations in Uganda for HIV/AIDS.12,13,16-19

Currently, concerted efforts to involve them in the search for a preventive biomedical option are ongoing. FP use is required in research due to safety concerns of the study products.20,21 Although FCs in Uganda are targeted study populations for HIV prevention research,22,23 their FP practices are poorly understood.15 Establishing barriers to FP use in this population will help identify gaps that researchers need to bridge as they prepare to involve them in HIV prevention research. Knowing facilitators of FP use can inform strategies to improve sexual and reproductive health service provision in this and other mobile populations. We hypothesize that engagement in multiple sexual partnerships facilitates one to use FP. Henceforth, we set out to determine barriers and facilitators of FP use among individuals living in FCs of Lake Victoria in Uganda.

Methods

Study Site and Population

The study was conducted in two fishing communities along the shores of Lake Victoria in Uganda.13 Kigungu, a mainland landing site and Nsazi, an island site were purposively selected for this study based on their location (close to Entebbe) and size. Community members consisted of residents and nonresidents who engage in fishing or fishing-related activities, which include fishermen, boat owners, fish processors, boat makers, local fishing gear makers or repairers, fishing equipment dealers and managers, as well as fish mongers and traders. Beyond fish-related occupations, we also observed farmers, students, and casual laborers in these communities. The 2 study sites are located about 25 km apart. Kigungu landing site has a population of approximately 30 000 people while Nsazi Island has about 8000 people. Most residents live in temporary housing structures made of wood and aluminum with poor sanitation and limited access to social services like health facilities, electricity, and clean water.12

Kigungu has 1 Health Centre III facility and a few private clinics where people access medical services. Health Centre III services include a maternity ward and outpatient services, including free HIV counseling and testing. Although a facility at this level should be offering all short acting reversible and long-acting reversible methods such as implants and intrauterine devices at no cost, the only FP methods offered include male condoms, pills, and injectable Depo-Provera or Injectaplan.

Access to health services in Nsazi is limited to a government Health Centre II and small private clinics, which makes it difficult for the residents to access all sexual and reproductive health services or other health care services. A Health Centre II normally provides short-acting reversible methods, including male condoms, pills, and injectable Depo-Provera or Injectaplan at no cost. In both sites, community-based non-governmental organizations provide sporadic HIV management outreaches and FP services covering a wide range of choices. They offer some medical services that include information dissemination, treatment of minor illnesses, condom distribution, implant and IUD insertions. Referrals are made to Entebbe and Kisubi hospitals (located approximately 10 km from Kigungu and 27 km over water from Nsazi) for more comprehensive services. Both sites are of a rural setting and the residents are reported to be highly mobile similar to what is observed in other FCs.24-26 They are also characterized by a high presence of alcohol establishments and commercial sex work.12,16,27

Study Design

A baseline cross-sectional survey was conducted from February 2017 to November 2017 in Kigungu and Nsazi communities. In addition, a descriptive exploratory design was employed where 4 focus group discussions (FGDs) and 10 in-depth interviews (IDIs) stratified by age and gender were conducted to document facilitators and barriers to FP use.

Selection of Study Participants

The sample size for the cross-sectional survey was obtained using a household list with 1786 households that was previously generated during mapping and census of the FCs. A total of 1452 eligible households were selected from this list. It is from the 1452 households that we got the 1410 participants who were interviewed. Either the man or woman in the eligible household was a potential participant. If both the woman and man were eligible, they would agree on who should be interviewed. Participants aged 15 to 49 years, willing to participate and who were resident in these communities for at least 6 months at the time the study were eligible to participate. Those who were not willing to consent for the study or those who were not available for the study duration were excluded.

In the qualitative component, participants were selected based on their professions and perceived roles by community members to express their views and opinions. The FGDs included 8 to 11 participants per session. The IDIs included local leaders, health, religious or youth representatives who were recommended by community gate keepers such as political, social, and cultural heads in these communities.

Data Collection

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to collection of study data. Survey data were collected by a well-trained and experienced team of 5 interviewers.

Survey Instrument

A semistructured questionnaire, including aspects on sociodemographic characteristics of study participants, pregnancy history, fertility desire, sexual behaviors, and practices was administered. FP knowledge was assessed and knowledge was considered satisfactory if a participant attained a score of ≥80% from 5 parameters, which included awareness about FP methods, knowledge about ideal number of children for a couple, knowledge about ideal birth spacing interval, knowledge about FP methods and their side effects, and interval between the last 2 children. The study participants were asked questions in relation to the use of FP methods; whether they were currently using any FP method, and if so, what type of method, for what duration and what the source of methods used was. They were also asked reasons for using those particular methods while those who were not using any methods were asked reasons why not. In this study, FP methods included both modern and traditional or natural FP methods. The modern FP methods (considered as effective methods) included tubal ligation, vasectomy, implants, intrauterine device, pills, injectables, foam/jelly, diaphragm, female or male condoms, and emergency contraception. Traditional or natural FP methods included periodic abstinence, calendar method, breastfeeding or lactation amenorrhea, rhythm or withdrawal method, and use of moon beads.

Qualitative Data Collection

FGDs and IDIs were conducted by experienced facilitators in either English or Luganda language using study guides. The study guides included open and close-ended questions aimed at eliciting information on participants’ knowledge of FP, sociocultural beliefs and practices, perceptions of and attitudes to FP use. The study guides and other study tools were piloted before they were used.

FGDs lasted between 65 and 103 minutes while the IDIs lasted between 37 and 75 minutes. The FGDs and IDIs were audio-recorded and conducted until saturation was reached. One FGD was not recorded due to technical difficulties; 2 research assistants who were fluent in both English and Luganda took detailed notes during discussions and interviews. Data were transcribed verbatim and transcripts did not bear participant names. The discussions and interviews were conducted in a private environment to enable participants to freely share their views. Final transcripts were stored securely on password-protected laptops and external drives.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were double entered in Microsoft Access, cleaned, and exported to STATA 15.0 (StataCorp) for analysis. Discrepancies were resolved by checking the source documents for clarification. Participants’ categorical, demographic, and clinical characteristics were summarized by counts and percentages. Continuous variables were summarized by means or standard deviations if appropriate or either medians or interquartile range. These characteristics were further compared by study site and sex to see if there were significant differences using the chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact where appropriate. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were done per study site to identify which factors were associated with FP use. Logistic regression was used to interpret factors associated with FP use. At unadjusted analysis, factors for which the association attained statistical significance on log likelihood ratio test (LRT) of P < .10 were selected for the multivariable logistic regression model. We considered age and sex of the participants as prior potential confounders based on literature.15,28-30 Factors were retained in the final multivariable logistic regression model if they were significantly (P < .05) associated with FP, or if they might have confounded other relationships (their removal changed the adjusted odds ratio [aOR] of another factor by 10%-15%). Results were presented as aORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

With regard to qualitative data, the primary author read all transcripts and listed key statements that emerged, ideas, opinions and attitudes expressed. This helped identify preliminary thematic categories that constituted the coding schedule. Data from each source were coded by the first author and discussed with the second and last author. Data were then coded according to generated themes and topics, merged and analyzed using a thematic approach with support of NVivo (version 12) qualitative software.31 Participant quotes from some FGDs and IDIs have been used to illuminate themes and findings.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval for the study was provided by Uganda Virus Research Institute–Research Ethics Committee and regulatory approval by Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to conducting any study procedures. FP services and HIV counseling and testing were offered to study participants who needed them free of charge.

Results

Sociodemographic Profile of Participants

Up to 1410 individuals participated in the study, majority of whom 1143 (81%) were from Kigungu (Table 1). The mean age was higher in Nsazi than in Kigungu and in both sites, males tended to be older than females. The majority of men in Kigungu (338; 58%) and in Nsazi (96; 82%) were engaged in fishing or a fishing-related activity. A small number (62; 4%) were students residing in Kigungu, the majority (39; 63%) of whom were males. Half (706; 50%) of the participants had attained only up to primary level of education with very few (106; 8%) in both villages reaching the tertiary education level, and more males attaining that level in both villages. Most (1043; 74%) of the participants had stayed over 12 months in the community.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Profile in a Family Planning Cross-Sectional Survey Stratified by Site and Gender in 2 Fishing Communities of Lake Victoria in Uganda.

| Characteristic | Village and sex distributions | Overall P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 1410), n (%) | Kigungu (n = 1143), n (%) | Nsazi (n = 267), n (%) | ||||

| Overall | Male (n = 579) | Female (n = 564) | Male (n = 118) | Female (n = 149) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 27.5 (7.2) | 28.4 (7.6) | 25.8 (6.3) | 30.5 (7.8) | 28.0 (6.8) | <.001 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 26 (22-32) | 27 (22-33) | 24 (21-30) | 29 (24-35) | 27.5 (22-32) | <.001 |

| Age group, years | .01 | |||||

| 15-29 | 911 (65) | 342 (59) | 417 (74) | 61 (52) | 91 (61) | |

| 30-39 | 397 (28) | 183 (32) | 125 (22) | 41 (34) | 48 (32) | |

| 40+ | 102 (7) | 54 (9) | 22 (4) | 16 (13) | 10 (7) | |

| Tribe | .1 | |||||

| Muganda | 631 (45) | 266 (46) | 246 (44) | 41 (34) | 78 (52) | |

| Munyankole | 129 (9) | 53 (9) | 61 (11) | 8 (7) | 7 (5) | |

| Musoga | 96 (7) | 26 (4) | 45 (8) | 16 (14) | 9 (6) | |

| Mukiga | 31 (2) | 9 (2) | 15 (3) | 4 (3) | 3 (2) | |

| Munyarwanda | 123 (9) | 61 (11) | 42 (7) | 10 (8) | 10 (7) | |

| Othera | 400 (28) | 164 (28) | 155 (27) | 39 (33) | 42 (28) | |

| Occupation | <.001 | |||||

| Farming | 36 (3) | 17 (3) | 14 (2) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | |

| Fishing/fishing related | 514 (36) | 338 (58) | 42 (7) | 96 (82) | 38 (25) | |

| Trade/business | 370 (26) | 38 (7) | 267 (47) | 10 (8) | 55 (37) | |

| Housewife | 124 (9) | 0 (0) | 92 (16) | 0 (0) | 32 (22) | |

| Student | 62 (4) | 39 (7) | 23 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Otherb | 304 (22) | 147 (25) | 126 (22) | 8 (7) | 23 (16) | |

| Religion | .001 | |||||

| Catholic | 590 (42) | 246 (42) | 232 (41) | 40 (34) | 72 (49) | |

| Protestant/Anglican | 339 (24) | 133 (23) | 132 (23) | 39 (33) | 35 (24) | |

| Muslim | 238 (17) | 108 (19) | 74 (13) | 24 (21) | 32 (21) | |

| Otherc | 243 (17) | 92 (16) | 126 (22) | 15 (13) | 10 (7) | |

| Highest education level | .001 | |||||

| No formal education | 82 (6) | 33 (6) | 37 (7) | 3 (3) | 9 (6) | |

| Primary level | 706 (50) | 277 (48) | 277 (49) | 64 (54) | 88 (59) | |

| Secondary level | 516 (37) | 200 (35) | 219 (39) | 46 (40) | 51 (34) | |

| Tertiary level | 106 (8) | 69 (12) | 31 (5) | 5 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| Marital status | <.001 | |||||

| Married | 810 (57) | 319 (55) | 333 (59) | 71 (60) | 87 (58) | |

| Single | 343 (24) | 188 (32) | 113 (20) | 27 (24) | 15 (10) | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 257 (18) | 72 (12) | 118 (20) | 20 (16) | 47 (32) | |

| Duration of stay | <.001 | |||||

| Months | 367 (26) | 114 (20) | 152 (27) | 46 (39) | 55 (37) | |

| Years | 1043 (74) | 465 (80) | 412 (73) | 72 (61) | 94 (63) | |

| Having multiple sexual partners in past 12 months | .026 | |||||

| No (<2 partners) | 876 (62) | 282 (49) | 444 (79) | 38 (32) | 112 (75) | |

| Yes (≥2 partners) | 534 (38) | 297 (51) | 120 (21) | 80 (68) | 37 (25) | |

| Ideal number of children for a couple | .007 | |||||

| ≤4 | 1134 (80) | 451 (78) | 484 (86) | 81 (69) | 118 (79) | |

| >4 | 276 (20) | 128 (22) | 80 (14) | 37 (31) | 31 (21) | |

| Are you currently in a sexual relationship? | .008 | |||||

| Yes | 1157 (82) | 459 (79) | 464 (82) | 101 (85) | 134 (90) | |

| No | 253 (18) | 120 (21) | 100 (18) | 18 (15) | 15 (10) | |

| Ideal birth spacing interval | .28 | |||||

| <2 years | 48 (3) | 27 (5) | 14 (2) | 5 (4) | 2 (1) | |

| ≥2 years | 1362 (97) | 552 (95) | 550 (98) | 113 (96) | 147 (99) | |

| Satisfactory FP knowledge | .001 | |||||

| No | 1128 (80) | 579 (100) | 355 (63) | 118 (100) | 76 (51) | |

| Yes | 282 (20) | 0 (0) | 209 (37) | 0 (0) | 73 (49) | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; FP, family planning.

Mugisu, Itesot, and non-Ugandan.

Sex worker, teacher, security personnel, and others.

Pentecostal/Born again, traditional African, no religion.

The majority (1157; 82%) of participants reported being in a sexual relationship while just over a half (810; 57%) of the participants were married. In both villages, more than half of the male participants, Kigungu (297; 51%) and Nsazi (80; 68%), reported having multiple sexual partners in the past 12 months. Majority of the participants indicated the ideal number of children for a couple as 4 or fewer children (1134; 80%) and the ideal spacing interval as 2 or more years (1362; 97%). Less than a quarter of the participants (282; 20%) had satisfactory FP knowledge and all who reported this were female.

Current Use of FP

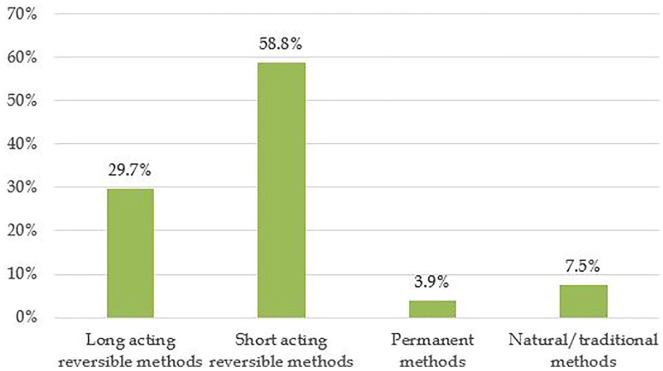

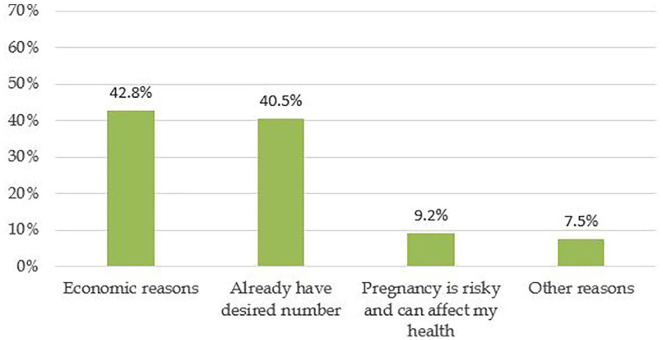

Overall, 35.6% (502/1410) were using FP. In Kigungu, 36% (411/1143) were using FP while 31% (91/267) in Nsazi were using FP (Table 2). The most commonly used FP methods were short-acting reversible methods (58.8%), which included pills, injectables, female or male condoms, and emergency contraceptive pills (Figure 1). Only a small number reported use of permanent methods also referred to as sterilization (vasectomy and tubal ligation) and natural or traditional methods (3.9% vs 7.5%). Most of the females who were using FP did not want to have more children. Majority cited economic constraints that arise from having a big family (42.8%) and having completed family sizes (40.5%) as reasons for not wanting more children (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Facilitators of Family Planning (FP) Use in 2 Fishing Communities of Lake Victoria in Uganda.

| Characteristic | Kigungu | Nsazi | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| uOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | uOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Overall FP use 35.6% (502/1410) | 36% (411/1143) | 31% (91/267) | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 15-29 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 30-39 | 1.16 (0.88-1.53) | 0.87 (0.64-1.18) | 1.05 (0.61-1.81) | 0.89 (0.49-1.62) |

| 40+ | 0.90 (0.55-1.49) | 0.72 (0.42-1.22) | 0.56 (0.21-1.48) | 0.64 (0.22-1.86) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 0.87 (0.69-1.11) | 0.77 (0.56-1.05) | 1.16 (0.70-1.94) | 1.33 (0.63-2.81) |

| Having satisfactory FP knowledge | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.48 (1.09-2.01) | 1.79 (1.23-2.61) | 1.65 (0.95-2.87) | 1.84 (0.90-3.76) |

| Religion | ||||

| Catholic | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Protestant/Anglican | 1.42 (1.04-1.94) | 1.45 (1.05-1.99) | 0.99 (0.53-1.85) | 1.20 (0.62-2.33) |

| Muslim | 1.41 (0.99-2.00) | 1.45 (1.01-2.07) | 1.08 (0.55-2.12) | 1.15 (0.57-2.30) |

| Othera | 0.89 (0.63-1.26) | 0.96 (0.67-1.37) | 0.92 (0.36-2.32) | 1.03 (0.39-2.70) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Married | 1.92 (1.42-2.58) | 1.84 (1.32-2.57) | 1.49 (0.71-3.13) | 1.63 (0.72-3.69) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 1.02 (0.68-1.52) | 0.92 (0.59-1.44) | 1.06 (0.45-2.49) | 0.86 (0.33-2.22) |

| Duration of stay | ||||

| Months | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Years | 1.41 (1.05-1.89) | 1.34 (0.98-1.82) | 1.11 (0.66-1.87) | 1.07 (0.61-1.90) |

| Having multiple sexual partners in past 12 months | ||||

| No (<2 partners) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes (≥2 partners) | 1.34 (1.05-1.72) | 1.41 (1.07-1.87) | 1.73 (1.04-2.89) | 2.60 (1.36-4.97) |

Abbreviations: uOR, unadjusted odds ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; Ref, reference.

Pentecostal/Born again, traditional African, no religion.

Figure 1.

Current use of family planning methods in 2 fishing communities of Lake Victoria in Uganda.

Short-acting reversible methods: Pills, condoms, injectables.

Long-acting reversible methods: Implants, intrauterine device.

Permanent methods: Vasectomy, bilateral tubal ligation.

Natural/traditional methods: calendar, moon beads, lactational ammenorhea, rhythm/withdraw.

Figure 2.

Reasons for not wanting to have (more) children (questions were asked to only women).

Reasons for FP Nonuse

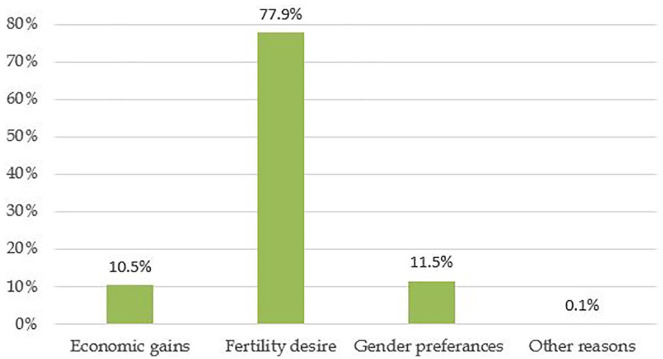

Reasons for FP nonuse were mainly fertility desire (25% in Kigungu and 20% in Nsazi), infrequent sex (23% in Kigungu and 29% in Nsazi), and fear of side effects (17% in Kigungu and 24% in Nsazi) (Table 3). The most common reasons for wanting more children among women were economic gains (10.5%), desire for big family sizes (77.8%), and gender preferences (11.5%) (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Reasons for Not Using Family Planning (FP) in 2 Fishing Communities of Lake Victoria in Uganda.a

| Reason for Not Using FP | Village | |

|---|---|---|

| Kigungu (n = 652), n (col %) | Nsazi (n = 144), n (col %) | |

| I want to have children/get pregnant | 197 (25) | 37 (20) |

| Infrequent sex | 180 (23) | 53 (29) |

| FP side effects | 136 (17) | 45 (24) |

| Religion does not permit use of FP | 39 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Lack of sexual satisfaction | 25 (3) | 1 (1) |

| My culture encourages having more children | 24 (3) | 1 (1) |

| My spouse/partner disapproved | 21 (3) | 2 (1) |

| FP is not effective | 13 (2) | 4 (2) |

| I do not know where to get FP methods | 13 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Economic reasons | 4 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Other reasons | 143 (18) | 40 (22) |

n = includes multiple responses.

Figure 3.

Reasons why participants wanted to have more children (Questions were asked to only women).

Factors Associated With FP Use

In Kigungu, at the unadjusted analysis, factors associated with FP use were having satisfactory FP knowledge, religion, marital status, duration of stay and having multiple sexual partners in the past 12 months (Table 2). After controlling for confounding, participants whose religion was Anglican, or Muslim were more likely to use FP than those whose religion was Catholic (aOR 1.45; 95% CI 1.05-1.99 and aOR 1.45; 95% CI 1.05-2.07, respectively). Participants were more likely to use FP if they had satisfactory FP knowledge (aOR 1.79; 95% CI 1.23-2.61) or if they were married (aOR 1.84; 95% CI 1.32-2.57) in comparison with those who did not have satisfactory knowledge and were single, respectively. Participants were also more likely to use FP if they were having 2 or more sexual partners in the past 12 months (aOR 1.41; 95% CI 1.07-1.87). In Nsazi, at the unadjusted analysis, FP use was associated with having multiple sexual partners in the past 12 months, which was maintained after adjusting (aOR 2.60; 95% CI 1.36-4.97).

Findings From the Qualitative Component of the Study

Overall, 4 FGDs and 10 IDIs were conducted, 2 FGDs with males (aged 18-25 years and 25-49 years) and 2 FGDs with females of the same age strata. A total of 47 volunteers participated in the FSD and IDIs. Five themes and 18 subthemes (refer to Table 4) were identified and used for thematic analysis of data.

Table 4.

Identified Themes, Subthemes, and Their Definitions in 2 Fishing Communities of Lake Victoria in Uganda.

| Theme | Subtheme | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding of family planning (FP) | Community members interpretation of the concept of FP and how they access FP | |

| Definition of FP | How participants defined FP or how they understand FP | |

| General community understanding and awareness of FP | What the community knows about FP and what their beliefs or perceptions are about FP | |

| Availability of FP | What are the FP sources and which methods are available | |

| FP methods known | All modern and traditional FP methods known | |

| Who is fit to use FP | People who participants thought were deserving to use FP | |

| Supporting others to use FP | Why participants chose to support or not to support friends and relatives to use FP | |

| Impact of FP | The effects of FP and how these effects influence is use | |

| Perceived benefits of FP | What participants expressed as advantages of FP | |

| Disadvantages of FP | What participants expressed as short comings of FP | |

| Side effects of FP | What participants expressed as negative health effects of FP | |

| Influence of side effects on use of FP | How side effects affect people’s decision to use FP | |

| Impact of FP on women’s health | How FP has affected the general health and reproductive health of women | |

| Awareness about FP | How and where FP messages are spread | |

| Sources of messages about FP | How and where people get information about FP | |

| Trusted people to deliver FP messages | People who participants said they trust when they tell them that FP is safe and effective | |

| Mechanisms of improving FP awareness | Suggested ways of improving FP awareness | |

| Challenges of FP delivery and solutions to the suggested challenges | Difficulties associated with FP use and remedies for the difficulties | |

| Challenges of FP delivery | Problems attributed to the use and provision of FP | |

| Solutions for challenges of FP delivery | Solutions suggested by participants for the prevailing challenges | |

| Barriers and facilitators of FP use | Factors influencing FP use | |

| Barriers of FP | Factors that hinder use of FP | |

| Facilitators of FP | Factors that promote use of FP |

Regarding understanding of FP, majority of the participants correctly interpreted the concept of FP although some had misconceptions as noted from one FGD participant who said, “family planning leads to birth of abnormal children; they may be disabled, or with abnormal features.” A female IDI participant said, “The understanding of family planning in this community is that it is used to completely stop one from getting children and yet it should really be for spacing births. Majority think when you use family planning you stop giving birth saying ‘amagi gasiriira’ [eggs get damaged].”

Many thought that family planning was for women and referred to it as a “woman thing.” A woman IDI participant said, “Family planning is really for the women, men do not know much about family planning issues and most of them do not encourage their women to use it.” A male IDI participant also said, “Some men are not willing to go to health centres to learn more about family planning, they think it’s only women who need it.” FP was also known by some to be for those who tend to be mobile like the youth and fishermen. One IDI male participant said, “Considering our community, I would say family planning is very necessary for the very mobile people like the fishermen.” When asked who was fit to use FP, a participant from a FGD of adult males said,

Many youth go fishing and they have many women because they have a lot of money. Fishermen also spend a lot of time at home during the day and they have high chances of impregnating their wives, hence the need for family planning.

Both modern and traditional methods were used with some citing unconventional methods like herbs and the remains of an umbilical cord. A female FGD participant said, “. . . our elders say that “akalira” [the umbilical cord] also works.”

Government and private health centers, nongovernmental organizations or research centers, drug shops or pharmacies, traditional birth attendants, and ordinary shops were reported as sources of FP in both communities. Challenges of method stock outs, unreliable working schedules, and unavailability of trained personnel who can offer surgical methods mainly in the island community were reported. One IDI participant said,

Only a few family planning methods are available at the health centres here in Nsazi. Some methods like tubal ligation and insertion of IUDs or implants can be done in Entebbe hospital or by UVRI-IAVI. The UVRI-IAVI clinic opens from Monday to Friday and Entebbe hospital is far. Some women have no money for transport to go to Entebbe hospital.

We also observed that when a preferred method of choice is unavailable in the community, members travel to Entebbe town, which has a district level (regional referral) hospital, as well as several private health centers that offer other reproductive health services and other health services.

When asked about the impact of FP on health and the general well-being of people, both positive and negative perceived impacts were cited. Many perceived implants, IUDs, vasectomy, and tubal ligation as relatively invasive compared with pills and injections. Other negative impacts included, promotion of promiscuity, misunderstandings leading to intimate partner violence and depopulation. Nonetheless, these did not deter some of them from using these methods or from recommending them to others to use. This was attributable to the positive impacts of FP, which included reduced economic burden on families, improved health for mothers and children, reduction in pregnancy related complications and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases.

Regarding side effects of FP, almost all participants said that hormonal methods such as pills and injections caused excessive bleeding which to them was an inconvenience and a safety risk. One IDI participant said, “When a woman gets excess bleeding, they fall sick and even become inconvenienced. Can you imagine a woman bleeding year in year out? Just put yourself in their shoes, they will just stop using family planning because of the discomfort.” Another said, “Excessive bleeding may lead to conflicts in the family because it interferes with the normal sexual relations in the home.”

Although not proven side effects of FP, delayed fecundity, abdominal masses, or cancers were perceived as negative impacts and barriers to FP use as evidenced by one FGD participant who said,

Others complain that after using family planning for some time and they decide to conceive, it’s usually difficult, and they get stressed. Some fear that the coil leads to cancer of the uterus. If it has been inserted for a long time, the chemicals it contains cause cancer.

There were cultural influences in favor of large families. One participant said,

Some people get concerned when one has few children, because culturally people are encouraged to have many children. The concern there stems from the fear that if the few die, then that will mark the end of a family lineage. It’s basically a cultural norm here to have many children. If you have one child, you may not get recognition in your culture.

Fertility desires, loss of libido, domestic violence, and gender preferences were cited as barriers to FP use. An FGD participant said,

Some men do not want their wives to use family planning because they believe in having many children. Here in Africa, a man who has many children is respected. So, a man will feel really bad if his wife gives birth to few children.

Another participant said, “Women say that they lose sexual desire. This has resulted into disputes in homes and violence in extreme cases.” While another said, “I cannot allow my wife to use family planning if we only have girls, she must continue giving birth until I get a male child who will be my heir.”

Some men in these communities do not practice birth control or spacing owing to religious concerns or beliefs. An FGD participant said, “Some religions discourage the use of family planning methods, especially the artificial ones. For example, the Catholic religion condemns the use of family planning and they refer to it as a sin.” Others think that bearing many children is advocated by Islam and is also beneficial for growth of the Muslim religion. For example, one FGD participant said, “Some of us are Muslims and Islam encourages having many wives and therefore many children.” Similar to that, another FGD participant said,

What I know is religion allows us to marry up to 4 wives if you can afford to look after them. If you have 4 wives, they can all choose to give birth and for that you have no control. For us, we believe in numbers, so the issue of family planning is really not taken seriously by the Muslims.

There were several concerns of lack of accessibility of some modern methods like female condoms, implants, IUD insertions and sterilization which are not available in the existing health centers as evidenced by a participant who said,

Sometimes there are challenges in the availability of family planning methods at the government health centres and in some private health settings. Some family planning services are not readily available in the nearby health centres, and people who want to use them are referred to the big hospitals where there are experts to offer them. I am referring to methods like vasectomy and tubal ligation or insertion of implants and coils. Not every health center or private clinic in Kigungu has the capacity to provide these services. And yet the hospital where women can get these services is far off.

Another participant said,

Only a few family planning methods are available at the health centres here in Kigungu. Some methods like tubal ligation and insertion of IUDs or implants can be done in Entebbe hospital or by IAVI. The IAVI clinic opens from Monday to Friday and Entebbe hospital is far. Some women have no money for transport to go to Entebbe hospital.

Nevertheless, many participants recommended FP use because of its biomedical, social, and economic benefits.

Discussion

This study explored the barriers and facilitators of FP use in 2 FCs of Lake Victoria in Uganda. Irrespective of the reason for using it, we found that just over a third used FP with short-acting reversible methods such as pills, Depo-Provera and condoms being more widely used compared with intrauterine devices and implants. Our findings are similar to findings from another study that was conducted in the same population, which observed that oral contraceptive pills and injectable Depo-Provera were predominantly used.15 On further interaction with participants, we observed that short-acting reversible methods were more easily accessible and available which might explain why they were used more. To promote the well-being of people living in FCs, considerable efforts to increase uptake while providing a broader range of options for women to choose from based on their individual contexts, and childbearing desires are needed. In my experience as an HIV researcher and amongst other vaccine networks, we have noted higher rates of pregnancy in women who rely on condoms, pills, or other methods such as abstinence. In order to ensure long contraception periods for research participants drawn from these communities, we underscore the need to scale up the use of long-acting reversible methods through sensitization of individuals and improvement of availability of these methods.

Although natural or traditional methods are conventionally not considered to be effective, some individuals reported using them.5,32 Other participants reported using herbs which they perceived to be effective. This is however not backed up by any evidence since there is paucity of studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of these herbal preparations. Examining potential obstacles to using modern and effective FP methods is important in understanding whether limited access to modern methods is a contributing factor or whether it is merely an issue of choice.

From the interviews, we found out that the cost of some products, their side effects and method stock outs were commonly cited as reasons for using natural or traditional methods and herbs. Transitioning from use of natural or traditional methods to use of modern effective methods requires that modern methods are available whenever they are needed. Whereas continuous and universal supply of FP methods is the governments’ or Ministry of Health’s mandate, non-governmental organizations and the private sector were reported to supplement by providing modern methods in the selected FCs. It was however noted that there are FCs where this supplemental provision is limited due to their remoteness or lack of health facilities.

We attributed the small proportion of participants using permanent methods to the study having been conducted in a rural setting where provision of such methods is limited which is congruent to findings from other rural settings in Uganda.33,34 In a study by Singh et al,35 which was carried out among married couples of urban slum migrants of Dehradun district in India aged 15 to 49 years, sterilization was the most popular method used. Unlike our study, this study was conducted in an urban setting where women were privy to modern reproductive health care services. Since permanent methods are hospital-based methods, our findings could still be attributed to the lack of health professionals who are trained to provide these services as was evidenced from the interviews. Stigma associated with use of permanent methods could be another possible factor given their high fertility desire and religious beliefs on contraception. The small proportion of participants using permanent methods to a small extent could be attributed to the young age of majority of the study participants. Due to their early sexual debut and high-fertility desire, a broad range of contraceptive choices is required to allow and empower people in FCs to make choices that suit their contexts and beliefs. The remoteness of some FCs and limited access to services may make longer term or permanent choices more attractive to some because no refills or re-insertions are required. To offer a broad range of options, deployment of trained health personnel and infrastructural upgrade of existing health centers may be worthwhile in this and other remote communities.

The limited FP knowledge was attributed to their low education levels and limited access to healthcare services in general. While some studies from other settings have shown that FP knowledge does not translate into use, our study suggested that having satisfactory FP knowledge was correlated with use.36-40 Pazol et al41 reported that educational interventions can help increase knowledge of available methods, enabling individuals to make informed choices and use FP more effectively. As the government embarks on expanding its social services to reach remote populations, it is necessary that sexual and reproductive health sensitization, including education on FP is prioritized in the FCs.

We presume that religious beliefs may have a negative influence on utilization as evidenced by higher use of FP by the Protestant or Anglican and Muslims compared with their Catholic counterparts. Previously, religion has been reported in other studies as a barrier to uptake of modern FP methods.4,42-44 In our qualitative analyses, we also noted that religious beliefs had a negative influence on the use (or nonuse) of FP. Widespread sensitization about benefits of FP is still required while targeting those whose religion does not necessarily encourage use of modern FP methods to control births.

In this study, we observed that those who were married were more likely to be using FP as compared to those who were single. This is consistent with findings from other studies and might be reasonably concluded that those who are single, divorced, or separated are less likely to be sexually active.45,46 Nevertheless, because the single, divorced, or separated at some point may engage in sexual activities, it is worthwhile to encourage them to use FP to prevent unintended pregnancies and associated adverse outcomes in addition to preventing sexually transmitted diseases, which are prevalent in these communities. We recommend that FP counseling programs should not exclusively focus on married couples.

Several studies from this population have found that people in FCs have multiple sexual partners.12-15,47 Multiple sexual partnerships appeared in our study to be positively associated with utilization of FP, which highlights the importance people with multiple sexual partners place on the benefits of FP. If FP uptake is to be optimized in this population, there is a need to also sensitize those in stable relationships and those with fewer sexual partners about the benefits of FP.

Regarding who should use FP, we observed from the interviews that FP use was perceived to be a woman’s issue. We also noted from the survey that only women had satisfactory knowledge of FP. Previous research has shown that male involvement in reproductive, maternal and child health is limited and challenging.48-50 In our study, we observed that majority, especially the men were engaged in multiple sexual partnerships and yet very few used FP. We presume that to some extent, the perception people have about who should use FP may be stigmatizing men who might be willing to use FP and the men who might be willing to support their sexual partners to use FP. No wonder in our study, there were women who did not use FP because they lacked consent from their spouses or sexual partners. It will be worthwhile for future FP education programs in FCs to involve men since men generally influence what goes on in families and can be empowered to use male specific methods. If men are empowered with knowledge on FP, it is possible that they will support their female partners to use FP and will be sensitized about male-specific methods.

Nonuse of FP was justified due to fear of side effects such as excessive bleeding and delayed fecundity. Women experience monthly bleeding which is part of their normal menstrual cycle. Any other vaginal bleeding regardless of the quantity causes discomfort and fear as many times it is associated with a pathological cause. Increasing awareness on other causes of vaginal bleeding and proper management of FP side effects could play a significant role in improving uptake.

It is worthwhile to note that in our study, there were myths and misconceptions about negative effects of FP use. For example, despite lack of evidence to support the assumptions, some participants believed that some FP methods led to abnormal abdominal masses, cancers, and birth of children with abnormal features. Similar to what has been observed elsewhere, many misconceptions about some FP methods still exist especially in communities of people with low education levels.36 This renders the need for FP providers in such communities to comprehensively sensitize FP users about possible side effects and thereby address FP myths and misconceptions that exist.

We observed that there were strong cultural beliefs in favor of large families and fertility desires for those who had no children, those who had few children or those who had gender preferences. Whereas these barriers are similar to what has been observed in other settings, some barriers such as unavailability of some methods, method stock outs, and lack of staff that are trained to offer surgical methods are structural barriers that can be alleviated.39,45,51,52 To improve access and availability of FP methods in this mobile and remote community, a combined effort from the government, nongovernmental organizations and the private sector is required to ensure a method mix at all times and presence of trained personnel to provide the methods. This might improve FP use in these communities and thus potentially avert unintended pregnancies and their consequent adverse outcomes while controlling their population sizes.

Study Limitations

Our study findings need to be treated cautiously to avoid overgeneralization due to some limitations mainly arising from the study design. The survey was cross-sectional, so our analyses illuminate correlation and may not imply causation. Study sites were selected for size and convenience of location relative to Entebbe and may not represent the opinion of residents in other FCs. However, the qualitative interviews provide a broader exploration and deeper understanding of the findings. The qualitative interviews were conducted with a limited number of people who may not represent the views of the whole population in the FCs. Nonetheless, participants were selected in consideration of their current professions, role in the community, and their perceived level of FP knowledge with the help of community gate keepers which makes our findings relevant.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Use of family planning by people in FCs of Lake Victoria in Uganda is suboptimal and the knowledge of FP types is limited. FP use was associated with religion, marital status, having multiple sexual partnerships, and having satisfactory FP knowledge. Barriers of FP use were mainly biomedical, religious, social, and cultural, which highlight the need for comprehensive FP education and strengthening of FP service provision mechanisms. It is necessary to promote continuous FP counselling to address sociocultural, biomedical, and religious barriers that hinder people from using FP. Health facilities need to be empowered to adequately address side effects of the different methods. Optimized access to multiple options should be ensured through infrastructural upgrade of existing health facilities or construction of FP delivery centers where they are non-existing. Last, delivery mechanisms that suit the complexity of such remote communities should be put in place to ensure effective access to all FP methods.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Study_Questionnaire for Barriers and Facilitators of Family Planning Use in Fishing Communities of Lake Victoria in Uganda by Annet Nanvubya, Rhoda Kitty Wanyenze, Onesmus Kamacooko, Teddy Nakaweesa, Juliet Mpendo, Barbarah Kawoozo, Francis Matovu, Sarah Nabukalu, Geoffrey Omoding, Jed Kaweesi, John Ndugga, Bernard Bagaya, Kundai Chinyenze, Matt Price and Jean Pierre Van Geertruyden in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly acknowledge IAVI and its donors for funding the study and all their support. We acknowledge the contribution made by VLIR-UOS Project. We further acknowledge the work done by the clinic, field, laboratory, data management, and administrative staff. And last, but not least, we acknowledge the study volunteers for their time and support to making this research a reality.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: AN: Lead and corresponding author was the principal investigator; contributed to application for funding, design of the study, made administrative arrangements for the study, data management, wrote the study protocol, carried out statistical analysis and contributed to interpretation of the data. BB: Participated in conceptualizing the idea, applying for funding and drafting the study protocol. BK: Contributed to study coordination, reviewed the manuscript drafts and interpretation of the data. FM and SN: Contributed to study coordination, data collection, reviewed the manuscript drafts. GO: Contributed to data collection, reviewed the manuscript drafts. TN and JSK: Contributed to data management, interpretation of the data and reviewed the manuscript drafts. JN: Reviewed the manuscript drafts. OK: Contributed to statistical analysis, reviewed the manuscript drafts and interpreted the data. RKW and JPG: Contributed to supervision of the study activities, interpretation of the data and review of the manuscript drafts. JM, KC, and MAP: Contributed to interpretation of the data and review of the manuscript drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by IAVI with the generous support of USAID and other donors; a full list of IAVI donors is available at www.iavi.org. The contents of this manuscript are the responsibility of the IAVI and co-authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government. IAVI contributed to study design, data interpretation, and review of the report. All other funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

ORCID iDs: Annet Nanvubya  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6092-6540

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6092-6540

Matt Price  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2918-1373

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2918-1373

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Jacqueline E, Darroch GS, Ball H. Contraceptive technologies: responding to women’s needs. Published April 2011. Accessed July 4, 2020 https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/contraceptive-technologies.pdf

- 2. Cleland J, Conde-Agudelo A, Peterson H, Ross J, Tsui A. Contraception and health. Lancet. 2012;380:149-156. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60609-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seiber E, Bertarand JT, Sullivan TM. Changes in contraceptive method mix in developing countries. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2007;33:177-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schenker JG, Rabenou V. Family planning: cultural and religious perspectives. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:969-976. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Contraceptive Use 2014 (POP/DB/CP/Rev2014). United Nations; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paul B, Ayo AS, Ayiga N. Rural-urban contraceptive use in Uganda: evidence from UDHS 2011. J Hum Ecol. 2015;52:168-182. doi: 10.1080/09709274.2015.11906941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children; Ministry of Health, Zanzibar; National Bureau of Statistics; Office of the Chief Government Statistician; ICF. Tanzania demographic and health survey and malaria indicator survey 2015-16. Published December 2016. Accessed July 4, 2020 https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR321/FR321.pdf

- 8. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; Ministry of Health; National AIDS Control Council; Medical Research Institute; National Council for Population and Development; DHS Program, ICF International. Kenya demographic and health survey, 2014. Published December 2015. Accessed July 4, 2020 https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr308/fr308.pdf

- 9. Odimegwu CO. Family planning attitudes and use in Nigeria: a factor analysis. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 1999;25:86-91. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Uganda Bureau of Statistics; DHS Program, ICF. Uganda demographic and health survey 2016. Published January 2018. Accessed July 4, 2020 https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR333/FR333.pdf

- 11. Ministry of Health, Uganda. Uganda family planning costed implementation plan, 2015-2020. Published November 2014. Accessed July 4, 2020 https://advancefamilyplanning.org/sites/default/files/resources/CIP_Uganda.pdf

- 12. Kiwanuka N, Mpendo J, Nalutaaya A, et al. An assessment of fishing communities around Lake Victoria, Uganda, as potential populations for future HIV vaccine efficacy studies: an observational cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:986. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Opio A, Muyonga M, Mulumba N. HIV infection in fishing communities of Lake Victoria basin of Uganda—a cross-sectional sero-behavioral survey. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seeley JA, Tumwekwase G, Grosskurth H. Fishing for a living but catching HIV: AIDS and changing patterns of the organization of work in fisheries in Uganda. Anthropol Work Rev. 2009;30:66-76. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nanvubya A, Ssempiira J, Mpendo J, et al. Use of modern family planning methods in fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Asiki G, Mpendo J, Abaasa A, et al. HIV and syphilis prevalence and associated risk factors among fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:511-515. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.046805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seeley JA, Allison EH. HIV/AIDS in fishing communities: challenges to delivering antiretroviral therapy to vulnerable groups. AIDS Care. 2005;17:688-697. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331336698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kiwanuka N, Ssetaala A, Mpendo J, et al. High HIV-1 prevalence, risk behaviours, and willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials in fishing communities on Lake Victoria, Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18621. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Edward H, Allison JS. HIV and AIDS among fisher folk: a threat to “responsible fisheries? ” Fish Fish. 2004;5:215-234. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2679.2004.00153.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ssali A, Namukwaya S, Bufumbo L, et al. Pregnancy in HIV clinical trials in Sub Saharan Africa: failure of consent or contraception? PLoS One. 2013;8:e73556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kibuuka H, Guwatudde D, Kimutai R, et al. Contraceptive use in women enrolled into preventive HIV vaccine trials: experience from a phase I/II trial in East Africa. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Asiki G, Abaasa A, Ruzagira E, et al. Willingness to participate in HIV vaccine efficacy trials among high risk men and women from fishing communities along Lake Victoria in Uganda. Vaccine. 2013;31:5055-5061. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kissling E, Allison EH, Seeley JA, et al. Fisher folk are among groups most at risk of HIV: cross country analysis of prevalence and numbers infected. AIDS. 2005;19:1939-1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kwena ZA, Camlin CS, Shisanya CA, Mwanzo I, Bukusi EA. Short-term mobility and the risk of HIV infection among married couples in the fishing communities along Victoria, Kenya. PLoS One. 2013;8:e5452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nunan F. Mobility and fisherfolk livelihoods on Lake Victoria: implications for vulnerability and risk. Geoforum. 2010;41:776-785. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nunan F, Luomba J, Lwenya C, Yongo E, Odongkara K, Ntambi B. Finding space for participation: fisherfolk mobility and co-management of Lake Victoria fisheries. Environ Manage. 2012;50:204-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seeley J, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Kamali A, et al. High HIV incidence and socio-behavioral risk patterns in fishing communities on the shores of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:433-439. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318251555d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gosavi A, Ma Y, Wong H, Singh K. Knowledge and factors determining choice of contraception among Singaporean women. Singapore Med J. 2016;57:610-615. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2015181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. White AL, Mann ES, Larkan F. Contraceptive knowledge, attitudes, and use among adolescent mothers in the Cook Islands. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018;16:92-97. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Giusti C, Daniele V. Determinants of contraceptive use in Egypt: a multilevel approach. Stat Methods Appl. 2006;15:89-106. doi: 10.1007/s10260-006-0010-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, Glasier A, Innis J. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet. 2006;368:1810-1827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69480-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dougherty A, Kayongo A, Deans S, et al. Knowledge and use of family planning among men in rural Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1294. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6173-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clark E, Goodhart C. Family planning in a rural setting in Uganda, the USHAPE initiative. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2016;8:105-108. doi: 10.1080/17571472.2016.1241302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Singh S, Priya N, Roy D, Srivastava A, Kishore S. Trends in contraceptive demands and unmet need for family planning in migrant population of Uttarakhand. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2018;5:590-595. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20180234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grabbe K, Stephenson R, Vwalika B, et al. Knowledge, use, and concerns about contraceptive methods among sero-discordant couples in Rwanda and Zambia. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18:1449-1456. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Semachew Kasa A, Tarekegn M, Embiale N. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards family planning among reproductive age women in a resource limited settings of Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:577. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3689-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nsubuga H, Sekandi JN, Sempeera H, Makumbi FE. Contraceptive use, knowledge, attitude, perceptions and sexual behavior among female University students in Uganda: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16:6. doi: 10.1186/s12905-016-0286-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Asiedu A, Asare BYA, Dwumfour-Asare B, et al. Determinants of modern contraceptive use: a cross-sectional study among market women in the Ashiaman Municipality of Ghana. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. 2020;12:100184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2019.100184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rizwan SA, Kankaria A, Ronald K, et al. Effect of literacy on family planning practices among married women in rural South India. Int J Med Public Health. 2012;2:27. doi: 10.5530/ijmedph.2.4.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pazol K, Zapata LB, Tregear SJ, Mautone-Smith N, Gavin LE. Impact of contraceptive education on contraceptive knowledge and decision making: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2 suppl 1):S46-S56. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hirsch JS. Catholics using contraceptives: religion, family planning, and interpretive agency in rural Mexico. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39:93-104. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00156.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Srikanthan A, Reid RL. Religious and cultural influences on contraception. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30:129-137. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32736-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pinter B, Hakim M, Seidman DS, Kubba A, Kishen M, Di Carlo C. Religion and family planning. Eur J Contracept Reprod Heal Care. 2016;21:486-495. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2016.1237631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wagner GJ, Wanyenze R. Fertility desires and intentions and the relationship to consistent condom use and provider communication regarding childbearing among HIV clients in Uganda. ISRN Infect Dis. 2013;2013:478192. doi: 10.5402/2013/478192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tilahun T, Coene G, Temmerman M, Degomme O. Couple based family planning education: changes in male involvement and contraceptive use among married couples in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tanzarn N, Bishop-Sambrook C. The Dynamics of HIV/AIDS in Small-Scale Fishing Communities in Uganda. HIV/AIDS Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wolff B, Blanc AK, Ssekamatte-Ssebuliba J. The role of couple negotiation in unmet need for contraception and the decision to stop childbearing in Uganda. Stud Fam Plann. 2000;31:124-137. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2000.00124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Davis J, Vyankandondera J, Luchters S, Simon D, Holmes W. Male involvement in reproductive, maternal and child health: a qualitative study of policymaker and practitioner perspectives in the Pacific. Reprod Health. 2016;13:81. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0184-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gebrekidan M. The role of men in fertility and FP program in Tigray region. Ethiop J Heal Dev. 2002;16:247-255. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thummalachetty N, Mathuir S, Mullinax M, et al. Contraceptive knowledge, perceptions, and concerns among men in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:792. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4815-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Matovu JKB, Makumbi F, Wanyenze RK, Serwadda D. Determinants of fertility desire among married or cohabiting individuals in Rakai, Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2017;14:2. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0272-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Study_Questionnaire for Barriers and Facilitators of Family Planning Use in Fishing Communities of Lake Victoria in Uganda by Annet Nanvubya, Rhoda Kitty Wanyenze, Onesmus Kamacooko, Teddy Nakaweesa, Juliet Mpendo, Barbarah Kawoozo, Francis Matovu, Sarah Nabukalu, Geoffrey Omoding, Jed Kaweesi, John Ndugga, Bernard Bagaya, Kundai Chinyenze, Matt Price and Jean Pierre Van Geertruyden in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health