Abstract

Background

Agitation is a common neuropsychiatric symptom of Alzheimer disease (AD). Data are scarce regarding agitation prevalence among community‐dwelling patients with AD.

Objective

To estimate agitation prevalence in a sample of US patients with AD/dementia overall and by AD/dementia disease severity, using data from electronic health records (EHR).

Methods

This retrospective database study examined community‐dwelling patients with ≥1 EHR record indicating AD/dementia from January 2008 to June 2015 and no evidence of non‐Alzheimer dementia during the 12‐month preindex and postindex periods. Agitation was identified using diagnosis codes for dementia with behavioral disturbance and EHR abstracted notes records indicating agitation symptoms compiled from the International Psychogeriatric Association provisional consensus definition.

Results

Of 320 886 eligible patients (mean age, 76.4 y, 64.7% female), 143 160 (44.6%) had evidence of agitation during the observation period. Less than 5% of patients with agitation had a diagnosis code for behavioral disturbance. The most prevalent symptom categories among patients with agitation, preindex and postindex, were agitation (31.4% and 41.3%), falling (22.6% and 21.7%), and restlessness (18.3% and 23.3%). Among the 78 827 patients (24.6%) with known AD/dementia severity, agitation prevalence was 61.3%. Agitation during the observation period was most prevalent for moderate‐to‐severe and severe AD/dementia (74.6% and 68.3%, respectively) and lowest for mild AD/dementia (56.4%).

Conclusions

Agitation prevalence was 44.6% overall and 61.3% among patients with staged AD/dementia. Behavioral disturbance appeared to be underdiagnosed. While agitation has previously been shown to be highly prevalent in the long‐term care setting, this study indicates that it is also common among community‐dwelling patients.

Keywords: agitation, Alzheimer disease, behavioral disturbance, dementia, disease progression, electronic health records, prevalence, retrospective studies

Key points.

In this large sample of patients with Alzheimer disease (AD)/dementia, 44.6% of all patients and 61.3% of those whose AD/dementia severity could be determined had electronic health records (EHR) documentation of agitation symptoms over 2 years.

Less than 5% of patients identified with agitation had a diagnosis code for behavioral disturbance in the EHR diagnosis table. While the EHR diagnosis table does not reflect claims submitted for payment, this finding may suggest that behavioral disturbance is underrepresented in claims data.

The prevalence of agitation was highest among patients with moderate‐to‐severe and severe AD/dementia.

While a majority of published studies have shown a high prevalence of agitation in the long‐term care setting, this study indicates that agitation is also common among community‐dwelling patients.

1. INTRODUCTION

The global burden of Alzheimer disease (AD) is growing rapidly with the aging of the world's population: There were an estimated 35.6 million people living with dementia worldwide in 2010, with numbers predicted to nearly double every 20 years.1 In the United States, the number of adults age 65 and older with AD is expected to reach 7.1 million by 2025—a nearly 35% increase from the 5.3 million affected individuals in 2017.2

Patients with AD are affected not only by the memory loss and cognitive decline that are hallmarks of the disease but also by a wide range of neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) that include agitation, mood disorders, psychosis, and sleep disturbances.3 NPS are experienced by nearly all patients with dementia at some point during the course of their disease4, 5, 6 and exacerbate the already substantial social and economic burden exacted by AD, contributing to increased morbidity, mortality, and institutionalization among patients with AD7, 8 and to psychological distress and other health problems among their caregivers.2, 8, 9, 10 In fact, the effect of NPS on patient and caregiver quality of life is consistently found to be even more detrimental than that of functional or cognitive impairment,7, 9, 11, 12, 13 leading to widespread acknowledgement of NPS as a public health priority in neurodegenerative disease.3

Agitation, characterized by excessive psychomotor activity, physical or verbal aggression, disruptive irritability, and disinhibition,3 is one of the most common NPS among patients with dementia, with prevalence estimates ranging from 40% to 60%.4, 14, 15, 16, 17 In addition to being one of the most distressing NPS for caregivers,10, 14 agitation has been associated with faster progression to severe dementia, functional decline, increased risk of institutionalization, and earlier death.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Management of agitation is thus a critical factor in the care of patients with AD, but no drugs at present have been approved in the United States for treating agitation in the population with dementia. Clinicians therefore turn to off‐label prescription of antipsychotics, sedatives, and other psychoactive drugs when nonpharmacological approaches are insufficient and/or patients' symptoms are severe. Unfortunately, these treatments are limited by concerns regarding efficacy, safety, and tolerability.3, 26

Although recent progress in elucidating the mechanisms that may underlie NPS has spurred optimism regarding potential pharmacological treatments for AD, clinical research in the field has historically been hampered by heterogeneity in entry criteria and outcome measures among studies.3 To help advance research into agitation among patients with dementia, the International Psychogeriatric Association (IPA) in 2015 released a provisional consensus definition that broadly defined agitation as excessive motor activity or verbal/physical aggression that (1) occurs in a patient with cognitive impairment or dementia syndrome, (2) is accompanied by evidence of emotional distress, (3) results in disability beyond that caused by cognitive impairment, and (4) is not solely attributable to another condition.27 Development and utilization of this definition are expected to facilitate high‐quality clinical and epidemiological investigations addressing agitation among patients with AD and other cognitive disorders by helping to define study populations and standardize baseline assessment.27

Given the profound impact of NPS on quality of life and the evidence that the presence of these symptoms may affect the course of AD, the relationship between agitation and AD disease stage is an important research target that could help inform both study design and treatment decisions.28 However, little has been published on the overall prevalence of agitation among community‐based patients, and existing data originate from clinical studies that used specialized rating scales and/or psychiatric evaluations that may not be widely performed in real‐world practice.29, 30, 31 We therefore conducted an analysis to estimate the prevalence of agitation symptoms in a sample of US patients with AD/dementia and the prevalence of agitation by AD/dementia disease severity. This study was performed using terms consistent with the IPA provisional definition of agitation in conjunction with data from electronic health records (EHR), which leverages information from patients' medical records to provide a wide range of clinical data on a population level.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Data source

This was a retrospective observational analysis using data from the Optum Clinical Electronic Health Record Database, which contains deidentified and aggregated clinical and medical administrative data from more than 54 US health care delivery organizations, including more than 140 000 providers at more than 700 hospitals and 7000 clinics. These data come from all EHR capture systems submitted by participating organizations. Data are obtained from physician offices, emergency rooms, laboratories, and hospitals and include demographic information, vital signs, and other observable measurements, medications prescribed and administered, laboratory test results, administrative data for clinical and inpatient stays, and coded diagnoses and procedures. At the time of data extraction, the database contained records for approximately 47 million primarily community‐dwelling patients across the United States and Puerto Rico, with an average of 45 months of observed data per patient. Because no identifiable protected health information was extracted or accessed during the course of the study, institutional review board approval or waiver of authorization was not required.

In addition to the data described above, the key EHR data for this study comprised abstracted provider notes records, which were extracted from electronic notes via a natural language processing (NLP) system developed and maintained by Optum Analytics (OA; Boston, Massachusetts). The NLP system captures words and phrases from unstructured text in clinical notes—including conditions, signs and symptoms, family history, disease‐related scores and diagnostic procedures, medication changes, and physician rationale for prescribing decisions—and converts them into abstracted notes records that contain deidentified, consistently formatted content for analysis. The abstracted notes records output via NLP consist of the main terms, such as conditions (eg, Alzheimer disease) or symptoms (eg, agitation), accompanied by additional data fields that provide context; these supporting fields contain terms relating to severity/frequency/duration, body part or measurement value, medical chart section, and qualifiers such as negation or progress in the diagnostic process or input from family members. Main terms of interest for the NLP system were identified using vocabulary from the Unified Medical Language System, which includes medical dictionaries such as the Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes, the Systemized Nomenclature of Medicine‐Clinical Terms, and RxNorm (a listing of generic and branded drugs), among others. New NLP concepts are created, and the performance of the NLP system is verified, by a team of medical terminologists and clinicians from OA that assesses the accuracy of the NLP output compared with a manual review of sample EHR notes.

For this study, abstracted notes records to identify AD/dementia and agitation were reviewed manually by Optum's medical director to determine whether the overall combinations of terms in the notes record fields were indicative of probable AD/dementia and agitation (eg, pertained to patient behavior or disposition and were not negation).

2.2. Study sample selection

The initial sample (Figure 1) comprised patients aged 65 years and older who had at least one EHR record with one or more of the following during the period of January 2008 through June 2015 (patient identification period): (1) at least one International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) diagnosis code for AD/dementia (Table A1); (2) abstracted notes records from direct physician encounters that indicated “probable” AD/dementia ; or (3) notes records with interpretable Mini‐Mental Status Examination (MMSE) scores or assessments. In all, 550 394 different term combinations representing a total of 13 139 781 abstracted notes records were reviewed to identify patients with probable AD/dementia. Index dates were defined hierarchically, as follows. For patients who had an explicit AD/dementia severity level (ie, at least one notes record for probable AD/dementia with an explicit severity level and/or at least one notes record with a valid MMSE score indicating mild, moderate, or severe AD/dementia), the index date was the date of the first record with an explicit severity level. For patients with at least one notes record indicating probable AD/dementia but no records indicating explicit severity, the index date was the date of the first record indicating probable AD/dementia. Finally, for patients who had no notes records indicating probable AD/dementia, the index date was the date of the first AD/dementia diagnosis record. To be included in the final study sample, patients were required to have at least two EHR records each during the 12 months before and after the index date (preindex and postindex periods, respectively), at least one EHR record each before the beginning of the preindex period and after the end of the postindex period, and no EHR diagnosis records for non‐Alzheimer dementia during the preindex or postindex periods (Table A2).

Figure 1.

Sample selection and attrition flow diagram. AD, Alzheimer disease; EHR, electronic health records; MMSE, Mini‐Mental Status Examination

2.3. Study measures

Preindex patient characteristics included age, sex, and Charlson comorbidity score,32 which was calculated using EHR diagnosis records during the preindex period. Patients with agitation during the preindex and postindex periods were identified on the basis of diagnosis table records with diagnosis codes for dementia with behavioral disturbance (ICD‐9‐CM 294.11, 294.21; ICD‐10‐CM F01.51, F02.81, F03.91) and information extracted from EHR notes. To identify agitation from EHR notes, agitation‐related symptoms were compiled from the 2015 IPA consensus definition27 (Table 1) and abstracted notes records with agitation‐related main terms were reviewed to identify those indicating probable agitation symptoms. The final list included 126 main terms from notes records, categorized into 19 symptoms (Table A3). In all, 1 396 455 different term combinations representing a total of 44 539 115 abstracted notes records were manually reviewed to identify probable agitation. Patients with agitation symptoms were identified with a binary indicator.

Table 1.

Agitation identification: agitation terms consistent with the 2015 International Psychogeriatric Association Working Group agitation definition27

| Category | Example Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Excessive motor activity |

Gesturing Finger pointing Irritability Jumpiness Pacing Repetitious mannerisms Repetitive questions/sentences Restlessness Rocking Shakiness Wandering |

| Verbal aggression |

Complaining Constant requests for attention/neediness Excessively loud voice volume Negativism Outbursts Repetitions questions, statements Screaming Shouting Strange noises (unusual laughter, crying) Stubbornness Profanity/cursing/swearing Verbal sexual advances Yelling |

| Physical aggression |

Biting Destruction of property Grabbing Hitting self or others Hoarding Hurting self or others Kicking Physical sexual advances Pushing Resistiveness Scratching Shoving Slamming doors Spitting Tearing objects Throwing objects |

2.4. AD/dementia severity categorization

AD/dementia severity category assignments were based on MMSE scores and physician notes (Table 2). Patients who had notes records containing valid quantitative MMSE scores or explicit terms for only one level of AD/dementia severity during the postindex period were categorized accordingly as “mild,” “mild‐to‐moderate,” “moderate,” “moderate‐to‐severe,” or “severe.” For patients whose notes records contained multiple severity levels, a severity category was determined by examining the chronological distribution of severity levels, as described in Table 2. Patients whose notes records contained no explicit AD/dementia severity information, contained only qualitative AD/dementia severity or MMSE scores, or suggested a clinically unlikely progression (eg, severe to mild) were categorized as “unknown.”

Table 2.

Alzheimer disease/dementia staging: criteria for assigning severity levels

| Criteria | AD/Dementia Severity Level Assignment |

|---|---|

| Records containing a valid quantitative MMSE score | |

| MMSE score from 19 to 22 | Mild |

| MMSE score from 12 to 18 | Moderate |

| MMSE score ≤11 | Severe |

| Records containing explicit terms of AD/dementia severity | |

| Terms such as “early” or “mild” | Mild |

| “Mild‐to‐moderate” (verbatim) | Mild‐to‐moderate |

| Terms such as “moderate” | Moderate |

| “Moderate‐to‐severe” (verbatim) | Moderate‐to‐severe |

| Terms such as “severe,” “advanced,” or “late‐stage” | Severe |

| Patients whose notes records contained multiple severity levels | |

| Records containing both explicit severity level(s) and unknown severity level(s) (eg, mild and unknown or moderate and unknown) | Categorized as the explicit severity level |

| Records containing mild and moderate, mild‐to‐moderate and mild, or mild‐to‐moderate and moderate, in a sequence that suggested progression from mild to moderate | Mild‐to‐moderate |

| Records containing moderate and severe, moderate‐to‐severe and moderate, or moderate‐to‐severe and severe, in a sequence that suggested progression from moderate to severe | Moderate‐to‐severe |

| Other situations | |

| Records containing no explicit AD/dementia severity information | Unknown |

| Records containing only descriptive MMSE results or descriptions of AD/dementia severity (eg, “much better,” “much worse,” “stable,” “within normal limits,” “worsening,” or “grossly abnormal”) | Unknown |

| Records showing clinically questionable progression (eg, severe to mild) | Unknown |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; MMSE, Mini‐Mental Status Examination.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics were compared between patients with and without agitation using two‐sample t tests for continuous variables (with Satterthwaite approximation for unequal variances) and Pearson chi‐squared tests for categorical variables. Outcomes were analyzed descriptively. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used for all statistical analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study sample and prevalence of agitation

The full study sample (Table 3) included 320 886 eligible patients (64.7% female); of these, 143 160 (44.6%) had EHR evidence of probable agitation during the 2‐year observation period. In the preindex period, 63 092 (19.7%) of all study patients had at least one probable agitation notes record, and 4600 (1.4%) had a diagnosis code for AD/dementia with behavioral disturbance. Postindex, these numbers were 115 084 (35.9%) and 15 710 (4.9%). Only 2563 (0.8%) and 10 049 (3.1%) of all patients in the preindex and postindex periods, respectively, had both a probable agitation notes record and a diagnosis code for behavioral disturbance. Among the 143 160 patients with probable agitation, mean (standard deviation [SD]) counts of probable agitation notes records in the preindex and postindex periods were 2.3 (2.9) and 2.8 (4.0), respectively; and mean (SD) counts of diagnoses of AD/dementia with behavioral disturbances in the preindex and postindex periods were 2.3 (3.1) and 3.3 (5.6), respectively.

Table 3.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Total (n = 320 886) | Patients Without Agitation (n = 177 726) | Patients With Agitation (n = 143 160) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 76.4 (5.2) | 76.4 (5.2) | 76.5 (5.2) | <0.001 |

| Age category, years, n (%)a | 0.001 | |||

| 65–74 | 104 743 (32.6) | 58 433 (32.9) | 46 310 (32.4) | |

| ≥75 | 216 143 (67.4) | 119 293 (67.1) | 96 850 (67.7) | |

| Sex, n (%)a | 0.067 | |||

| Male | 113 179 (35.3) | 62 968 (35.4) | 50 211 (35.1) | |

| Female | 207 635 (64.7) | 114 714 (64.5) | 92 921 (64.9) | |

| Missing/unknown | 72 (0.0) | 44 (0.0) | 28 (0.0) | |

| Preindex Charlson comorbidity score, mean (SD)b | 1.3 (1.7) | 1.1 (1.6) | 1.5 (1.9) | <0.001 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Percentages may not sum to 100.0 because of rounding.

Preindex diagnosis records from which the Charlson comorbidity score could be computed were available for 287 327 patients (89.5%).

Mean (SD) age was 76.4 (5.2) years and was similar between patients without vs with agitation (76.4 [5.2] y vs 76.5 [5.2] y, respectively, P < 0.001; difference in mean age was not clinically meaningful but was statistically significant because of large sample size). Mean (SD) preindex Charlson comorbidity scores were 1.3 (1.7) in the full study sample, 1.1 (1.6) among patients without agitation, and 1.5 (1.9) among patients with agitation (P < 0.001 for patients without vs with agitation).

3.2. Agitation symptoms

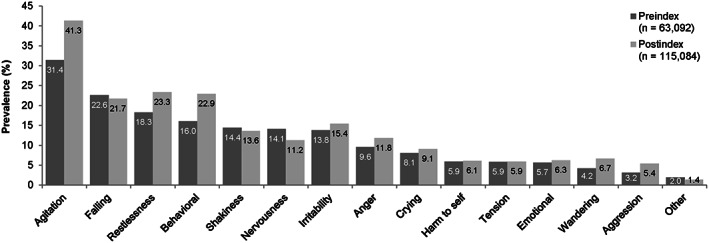

Among the 143 160 patients with agitation, the most prevalent agitation symptoms were agitation (31.4% preindex, 41.3% postindex), falling (22.6% preindex, 21.7% postindex), restlessness (18.3% preindex, 23.3% postindex), behavioral manifestations (16.0% preindex, 22.9% postindex), and shakiness (14.4% preindex, 13.6% postindex) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Preindex and postindex prevalence of agitation symptoms among patients with at least one probable agitation notes record

Of the 320 886 eligible patients, 78 827 (24.6%) could be assigned to explicit AD/dementia severity categories. The prevalence of agitation in the staged subgroup was 61.3% (Table 4). The distribution of staged patients by AD/dementia severity level was as follows: mild, n = 43 749 (55.5%); severe, n = 16 527 (21.0%); moderate, n = 7856 (10.0%); mild‐to‐moderate, n = 6712 (8.5%); and moderate‐to‐severe, n = 3983 (5.1%). The percentages of patients with at least one record indicating agitation in the 2‐year observation period were highest for patients with moderate‐to‐severe and severe AD/dementia (74.6% and 68.3%, respectively), followed by patients with mild‐to‐moderate and moderate AD/dementia (65.4% and 63.1%, respectively), and lowest for patients with mild AD/dementia (56.4%).

Table 4.

Prevalence of agitation by Alzheimer disease/dementia severity level

| Time Period | Total (n = 320 886) | All Staged Patients (n = 78 827) | Alzheimer Disease/Dementia Severity Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild (n = 43 749) | Mild‐to‐moderate (n = 6712) | Moderate (n = 7856) | Moderate‐to‐severe (n = 3983) | Severe (n = 16 527) | Unknown (n = 242 059) | |||

| 2‐year observation period, n (%) | 143 160 (44.6) | 48 288 (61.3) | 24 688 (56.4) | 4392 (65.4) | 4955 (63.1) | 2973 (74.6) | 11 280 (68.3) | 94 872 (39.2) |

| 12‐month preindex | 65 129 (20.3) | 25 640 (32.5) | 12 787 (29.2) | 2125 (31.7) | 2658 (33.8) | 1552 (39.0) | 6518 (39.4) | 39 489 (16.3) |

| 12‐month postindex | 120 725 (37.6) | 40 533 (51.4) | 20 284 (46.4) | 3851 (57.4) | 4230 (53.8) | 2652 (66.6) | 9516 (57.6) | 80 212 (33.1) |

4. DISCUSSION

Studies evaluating symptoms of agitation among patients with dementia are frequently conducted in a long‐term care setting. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to use electronic health record data to estimate agitation prevalence among patients with dementia living in the community. In this large‐scale analysis, the prevalence of agitation during the 2‐year observation period was substantial: 44.6% in the full study sample and 61.3% in a subset of patients with staged AD/dementia severity. This constitutes not only a considerable strain on patient and caregiver health but also a considerable economic burden, as agitation has been shown to engender high additional costs compared with cognitive impairment alone.22, 33 In a recent UK study, the presence of agitation was associated with significantly increased health care costs among home‐dwelling patients with AD, accounting for mean excess costs of £2 billion per year.33

Our agitation prevalence estimates fall within the 18% to 87% range described by a recent systematic review of previous studies on NPS in dementia.28 Point prevalence rates for agitation/wandering and mechanical/motor abnormalities have previously been reported in the range of 18% to 57%5, 30 and 10% to 61%,5, 34 respectively.5, 6, 10, 35 The variation in reported rates may be attributable to methodological differences due to earlier studies defining NPS using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), an assessment tool commonly used in clinical studies to screen for behavioral symptoms among patients with dementia.36 First, while we identified agitation on the basis of EHR notes from direct physician encounters and available diagnosis codes, the NPI is conducted via an interview with the patient's primary caregiver, whose assessment of agitation may differ from that of a physician. Second, the degree to which items assessed in the NPI overlap with the IPA provisional definition of agitation is not clear. For example, the approximately 43% prevalence of agitation/aggression found among patients with AD by Steinberg et al4 over 5 years appears similar to the overall agitation prevalence in our patient population; however, anxiety (approximately 61%), irritability (approximately 57%), and aberrant motor behavior (approximately 52%) were assessed as separate items in the Steinberg et al study, making direct comparison difficult.

Notably, relatively few patients had a diagnosis code for behavioral disturbance in the EHR diagnosis table (1.4% preindex, 4.9% postindex) despite nearly 45% of the study population having notes records that referred to agitation during the observation period. Because the EHR diagnosis table is not used for billing, information in the table may not reflect claims submitted for payment. The lack of behavioral disturbance diagnosis codes observed in EHR may suggest that this symptom is underestimated in administrative claims data, which bolsters the argument for assessing symptoms using data from EHR in addition to claims. Not all conditions discussed between a physician and patient during an office visit will be coded on a claim,37 and many conditions—including various agitation‐related symptoms—do not have a specific ICD code, reducing the likelihood that they will be captured. Claims data therefore may not provide a complete reflection of patient status.38, 39, 40 EHR data may capture signs and symptoms that are important to the clinical narrative but were not recorded as a diagnosis code, allowing the identification of patients that would have been missed by examination of claims data alone.37

In the present study, agitation was most common among patients with moderate‐to‐severe and severe AD/dementia, with prevalence rates of 74.6% and 68.2%, respectively. Although evidence suggests that agitation is associated with poorer cognitive function20, 28, 35 and tends to increase over time,5, 16, 25, 35 few previous studies have examined agitation prevalence by AD/dementia severity category. Our results are comparable with those of clinical studies by Lopez et al29 and Khoo et al,31 who found that the prevalence of agitation rose with increasing cognitive impairment and was highest (67% and 71%, respectively) in those with severe dementia among community‐dwelling patients. In contrast, other clinical studies have reported nonlinear relationships between cognitive status and agitation.30, 41 Holtzer et al30 found that mean MMSE scores among patients with probable AD decreased steadily over a 5‐year follow‐up, but the prevalence of agitation peaked at 57% in year 3 from a baseline level of 39% and then declined to 46% in year 5. A similar pattern was observed by Lovheim et al,41 who found that agitation symptoms such as wandering, aggression, restlessness, and verbally disruptive behavior were most prevalent among institutionalized patients in the middle stages of cognitive impairment. One possible explanation for these observations is that the diminished verbal ability and motor function associated with late‐stage dementia may mask the manifestation of certain NPS among patients with advanced disease.41

Our assessment of agitation prevalence by AD/dementia severity was limited by the preponderance of unknown staging: Only 24.6% (78 827 of 320 886) of patients in the study sample could be assigned to explicit AD/dementia severity categories. This limitation is a source of potential confounding, as the observation that agitation was present among only 45% of the total study sample vs 61% of staged patients suggests that patients with notes records indicating AD/dementia severity may have been more likely to have documented agitation symptoms and that agitation may have been underreported in the total population. The insufficiency of notes records from our EHR database to evaluate AD/dementia severity for most patients is likely attributable to multiple reasons, including a lack of AD/dementia severity information in EHR notes, the inability of NLP to effectively capture the extent of variation in charting practices among physicians, and disparities in the volume and content of electronic notes available from provider organizations represented in the EHR database. In addition, only notes records from direct encounters between physicians and patients were examined in this study. As NLP often generates more than one notes record from a single full‐text note and patients have notes records over time, there are multiple opportunities to identify a patient with a probable condition; nevertheless, some patients' severity status may have been missed because notes records from sources such as phone calls, emails, encounters with nonphysician health care providers, and interactions with caretakers were not interpreted.

Although the utilization of an EHR database to access diverse clinical information at large sample sizes was a strength of this study, the EHR data also have certain limitations that should be considered. Not every pertinent detail of a patient's health status will be reflected in EHR, and data for patients who receive some of their care from provider delivery organizations whose data are not included in the EHR database are incomplete. Furthermore, the EHR database contains data primarily from community‐dwelling patients; therefore, mild or moderate AD/dementia is likely overrepresented and severe dementia underrepresented in the study sample, and the study findings cannot be generalized to residents of long‐term care facilities. Given the potential incompleteness of EHR data, the lack of long‐term care residents in the study population, and the fact that only EHR from direct physician encounters were evaluated, our analysis may underestimate the true prevalence of agitation in the total population of patients with AD/dementia. Finally, it is possible that patients with mild dementia may have been less likely to have a dementia severity categorization due to less frequent use of health care services, which may present fewer opportunities for severity evidence to show up in the EHR database. This scenario could have resulted in those with mild dementia being overrepresented among unstaged patients and underrepresented among staged patients, contributing to the lower prevalence of agitation observed for unstaged vs staged patients in the present study. However, it should be noted that the prevalence of agitation among staged patients in this analysis was comparable with that found in clinical studies in which dementia severity was determined via cognitive evaluation rather than from administrative claims or EHR data,29, 31 suggesting that our results were not substantially affected by this potential bias.

5. CONCLUSION

In this large sample of patients with AD/dementia, approximately 45% of all patients and nearly two‐thirds of those whose AD/dementia severity could be determined had EHR documentation of agitation symptoms during the 2‐year observation period. Among patients identified with agitation, only a small percentage had a diagnosis code for behavioral disturbance. The prevalence of agitation was highest among patients with moderate‐to‐severe and severe AD/dementia. While a majority of published studies have shown a high prevalence of agitation in the long‐term care setting, this study indicates that agitation is also common among community‐dwelling patients. Our findings underscore the importance of managing agitation in caring for patients with AD, particularly in light of the faster disease progression, poor quality of life, and high economic costs associated with this NPS. Furthermore, the possible undercoding of behavioral disturbance diagnoses in claims data suggests that the richer clinical data available in EHR should be utilized to study behavioral symptoms such as agitation in this population.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

This study was funded by Otsuka America Pharmaceuticals (Princeton, New Jersey) and Lundbeck LLC (Deerfield, Illinois). M.S.A. and A.O. are employees of Otsuka; A.H. is an employee of Lundbeck LLC. R.H., J.S., and J.T. are employees of Optum, which was contracted by Otsuka to conduct the study and provide medical writing assistance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Medical writing assistance was provided by Yvette Edmonds, PhD (Optum, Eden Prairie, Minnesota). The authors thank Priyanka Koka, MS (Optum) and Rui Song, PhD (Optum) for programming the EHR data, and Caitlin Elliott, MS (Optum) for assistance with performing and verifying the data analysis.

APPENDIX A.

Table A1.

Diagnosis codes for Alzheimer disease/dementia

| Code | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 290.0 | ICD‐9‐CM | Senile dementia, uncomplicated |

| 290.10 | ICD‐9‐CM | Presenile dementia, uncomplicated |

| 290.11 | ICD‐9‐CM | Presenile dementia with delirium |

| 290.12 | ICD‐9‐CM | Presenile dementia with delusional features |

| 290.13 | ICD‐9‐CM | Presenile dementia with depressive features |

| 290.20 | ICD‐9‐CM | Senile dementia with delusional features |

| 290.21 | ICD‐9‐CM | Senile dementia with depressive features |

| 290.3 | ICD‐9‐CM | Senile dementia with delirium |

| 290.40 | ICD‐9‐CM | Vascular dementia, uncomplicated |

| 290.41 | ICD‐9‐CM | Vascular dementia, with delirium |

| 290.42 | ICD‐9‐CM | Vascular dementia, with delusions |

| 290.43 | ICD‐9‐CM | Vascular dementia, with depressed mood |

| 290.8 | ICD‐9‐CM | Other specified senile psychotic conditions |

| 290.9 | ICD‐9‐CM | Unspecified senile psychotic condition |

| 294.10 | ICD‐9‐CM | Dementia in conditions classified elsewhere without behavioral disturbance |

| 294.11 | ICD‐9‐CM | Dementia in conditions classified elsewhere with behavioral disturbance |

| 294.20 | ICD‐9‐CM | Dementia, unspecified, without behavioral disturbance |

| 294.21 | ICD‐9‐CM | Dementia, unspecified, with behavioral disturbance |

| 331.0 | ICD‐9‐CM | Alzheimer disease |

| F0150 | ICD‐10‐CM | Vascular dementia without behavioral disturbance |

| F0151 | ICD‐10‐CM | Vascular dementia with behavioral disturbance |

| F0280 | ICD‐10‐CM | Dementia in other diseases classified elsewhere without behavioral disturbance |

| F0281 | ICD‐10‐CM | Dementia in other diseases classified elsewhere with behavioral disturbance |

| F0390 | ICD‐10‐CM | Unspecified dementia without behavioral disturbance |

| F0391 | ICD‐10‐CM | Unspecified dementia with behavioral disturbance |

| F05 | ICD‐10‐CM | Delirium due to known psychological condition |

| G300 | ICD‐10‐CM | Alzheimer disease with early onset |

| G301 | ICD‐10‐CM | Alzheimer disease with late onset |

| G308 | ICD‐10‐CM | Other Alzheimer disease |

| G309 | ICD‐10‐CM | Alzheimer disease, unspecified |

Abbreviations: ICD‐9‐CM, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification; ICD‐10‐CM, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification.

Table A2.

Diagnosis codes for non‐Alzheimer dementia

| Code | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 331.7 | ICD‐9‐CM | Cerebral degeneration in diseases classified elsewhere |

| 331.9 | ICD‐9‐CM | Unspecified cerebral degeneration |

| G31.9 | ICD‐10‐CM | Degenerative disease of nervous system, unspecified |

| 331.3 | ICD‐9‐CM | Communicating hydrocephalus |

| G91.0 | ICD‐10‐CM | Communicating hydrocephalus |

| 331.6 | ICD‐9‐CM | Corticobasal degeneration |

| G31.85 | ICD‐10‐CM | Corticobasal degeneration |

| G31.2 | ICD‐10‐CM | Degeneration of nervous system due to alcohol |

| 331.82 | ICD‐9‐CM | Dementia with Lewy bodies |

| G31.83 | ICD‐10‐CM | Dementia with Lewy bodies |

| 331.11 | ICD‐9‐CM | Pick disease |

| 331.19 | ICD‐9‐CM | Other frontotemporal dementia |

| G3101 | ICD‐10‐CM | Pick disease |

| G3109 | ICD‐10‐CM | Other frontotemporal dementia |

| 333.4 | ICD‐9‐CM | Huntington chorea |

| G10 | ICD‐10‐CM | Huntington disease |

| G91.4 | ICD‐10‐CM | Hydrocephalus in diseases classified elsewhere |

| G91.9 | ICD‐10‐CM | Hydrocephalus, unspecified |

| 331.5 | ICD‐9‐CM | Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus [INPH] |

| G91.2 | ICD‐10‐CM | (Idiopathic) normal pressure hydrocephalus |

| G21.11 | ICD‐10‐CM | Neuroleptic induced parkinsonism |

| 331.4 | ICD‐9‐CM | Obstructive hydrocephalus |

| G91.1 | ICD‐10‐CM | Obstructive hydrocephalus |

| 331.89 | ICD‐9‐CM | Other cerebral degeneration |

| G21.19 | ICD‐10‐CM | Other drug induced secondary parkinsonism |

| G91.8 | ICD‐10‐CM | Other hydrocephalus |

| G21.8 | ICD‐10‐CM | Other secondary parkinsonism |

| G31.89 | ICD‐10‐CM | Other specified degenerative diseases of nervous system |

| 332.0 | ICD‐9‐CM | Paralysis agitans |

| 332.1 | ICD‐9‐CM | Secondary parkinsonism |

| G20 | ICD‐10‐CM | Parkinson disease |

| G91.3 | ICD‐10‐CM | Posttraumatic hydrocephalus, unspecified |

| 331.81 | ICD‐9‐CM | Reye syndrome |

| G93.7 | ICD‐10‐CM | Reye syndrome |

| G21.2 | ICD‐10‐CM | Secondary parkinsonism due to other external agents |

| G21.9 | ICD‐10‐CM | Secondary parkinsonism, unspecified |

| 331.2 | ICD‐9‐CM | Senile degeneration of brain |

| G31.1 | ICD‐10‐CM | Senile degeneration of brain, not elsewhere classified |

| G13.8 | ICD‐10‐CM | Systemic atrophy primarily affecting central nervous system in other diseases classified elsewhere |

| G13.2 | ICD‐10‐CM | Systemic atrophy primarily affecting the central nervous system in myxedema |

| G21.4 | ICD‐10‐CM | Vascular parkinsonism |

Abbreviations: ICD‐9‐CM, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification; ICD‐10‐CM, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification.

Table A3.

Electronic health record terms for agitation symptoms

| Agitation Symptom | Electronic Health Record Term |

|---|---|

| Aggression | AGGRESSION |

| AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR | |

| AGGRESSIVE PERSONALITY | |

| Agitation | AGITATED |

| AGITATED BEHAVIOR | |

| AGITATED DEPRESSION | |

| AGITATION | |

| PSYCHOMOTOR AGITATION | |

| RESTLESSNESS AND AGITATION | |

| Anger | INTERMITTENT EXPLOSIVE OUTBURST |

| ANGER | |

| ANGRY | |

| Behavioral | ATTENTION SEEKING BEHAVIOR |

| INAPPROPRIATE BEHAVIOR | |

| MANNERISM | |

| ABERRANT BEHAVIOR | |

| ABNORMAL BEHAVIOR | |

| ANTISOCIAL BEHAVIOR | |

| BEHAVIOR | |

| BEHAVIOR ABNORMALITY | |

| BEHAVIOR CHANGES | |

| BEHAVIOR DISORDER | |

| BEHAVIOR IMPAIRED | |

| BEHAVIOR ISSUES | |

| BEHAVIORAL | |

| BEHAVIORAL ABNORMALITY | |

| BEHAVIORAL CHANGES | |

| BEHAVIORAL IMPAIRED | |

| BEHAVIORAL ISSUES | |

| CHANGE IN BEHAVIOR | |

| DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR | |

| DISRUPTIVE BEHAVIOR DISORDER | |

| DISTURBANCE IN PHYSICAL BEHAVIOR | |

| HYPOMANIC BEHAVIOR | |

| IMPULSIVE BEHAVIOR | |

| MANIC BEHAVIOR | |

| NON‐SELF‐REGULATORY BEHAVIOR | |

| ODD BEHAVIOR | |

| STRANGE BEHAVIOR | |

| UNABLE TO CONTROL BEHAVIOR | |

| VERBALLY ABUSIVE BEHAVIOR | |

| WEIRD BEHAVIOR | |

| WEIRDNESS | |

| Cooperation | LACK OF COOPERATION |

| LACK OF PATIENT COOPERATION | |

| Crying | CRYING |

| CRYING SPELLS | |

| Emotional | DISTRESS |

| EMOTIONAL CRISIS | |

| EMOTIONAL INSTABILITY | |

| EMOTIONAL ISSUES | |

| EMOTIONAL LABILITY | |

| EMOTIONAL STRESS | |

| EMOTIONAL UPSET | |

| EMOTIONALLY LABILE | |

| Fall | ACCIDENTAL FALL |

| FALL | |

| FALL DOWN STAIRS | |

| FALL DOWN STEPS | |

| FALL FROM BED | |

| FALL FROM CHAIR | |

| FALL FROM HEIGHT | |

| FALL FROM SLIPPING | |

| FALL FROM STAIRS | |

| FALL FROM STANDING HEIGHT | |

| FALL FROM STOOL | |

| FALL FROM TOILET SEAT | |

| FALL FROM WHEELCHAIR | |

| FALL IN BATHTUB | |

| FALL IN HOME | |

| FALL IN NURSING HOME | |

| FALL IN SHOWER | |

| FALL ON CONCRETE | |

| FALL ON ICE | |

| FALL ON SNOW | |

| FALL ON STAIRS | |

| FALL ON STEPS | |

| FALL RISK | |

| FALLS | |

| MECHANICAL FALL | |

| Hostility | HOSTILE |

| HOSTILE BEHAVIOR | |

| HOSTILITY | |

| Irritability | IRRITABILITY |

| IRRITABILITY AND ANGER | |

| IRRITABLE | |

| IRRITATION | |

| Jumpy | EDGY |

| JITTERY | |

| JUMPY | |

| UNABLE TO KEEP STILL | |

| Nervous | NERVOUS |

| NERVOUSNESS | |

| Other | EXCESSIVE SPITTING |

| MULTIPLE COMPLAINTS | |

| MULTIPLE SOMATIC COMPLAINTS | |

| NAIL BITING | |

| NEGATIVISM | |

| RESISTANCE TO CHANGE | |

| SEXUAL ISSUES | |

| Harm to others | HITTING |

| VIOLENCE | |

| Restless | MOTOR RESTLESSNESS |

| RESTLESS | |

| RESTLESSNESS | |

| Harm to self | HARM SELF |

| SELF‐ABUSIVE | |

| SELF‐ABUSIVE BEHAVIOR | |

| SELF‐CUTTING | |

| SELF‐DESTRUCTIVE | |

| SELF‐DESTRUCTIVE BEHAVIOR | |

| SELF‐INJURIOUS BEHAVIOR | |

| SELF‐INJURY | |

| SELF‐MUTILATION | |

| Shakiness | SHAKES |

| SHAKINESS | |

| SHAKING | |

| SHAKING ALL OVER | |

| Tension | TENSE |

| TENSENESS | |

| TENSION | |

| Wandering | WANDER |

| WANDERERS | |

| WANDERING | |

| WANDERS | |

| WANDERS AT NIGHT |

Halpern R, Seare J, Tong J, Hartry A, Olaoye A, Aigbogun MS. Using electronic health records to estimate the prevalence of agitation in Alzheimer disease/dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:420–431. 10.1002/gps.5030

Footnotes

“Probable” for this analysis meant it was inferred that the patient had the condition or symptom of interest based on clinician review of the terms in the abstracted provider notes records. Notes records that indicated patients did not have dementia, did not indicate direct observation of the patient and his or her symptoms, contained uninterpretable or invalid MMSE scores, or were not from direct physician encounters were not categorized as “probable.” Main terms for AD/dementia were Alzheimer disease, Alzheimer dementia, dementia, senile dementia, presenile dementia, multiple infarction dementia, vascular dementia, subcortical vascular dementia, and arteriosclerotic dementia.

REFERENCES

- 1. Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):63‐75. e62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alzheimer's Association . 2017 Alzheimer's facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:325‐373. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Porsteinsson AP, Antonsdottir IM. An update on the advancements in the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer's disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18(6):611‐620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steinberg M, Shao H, Zandi P, et al. Point and 5‐year period prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(2):170‐177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gonfrier S, Andrieu S, Renaud D, Vellas B, Robert PH. Course of neuropsychiatric symptoms during a 4‐year follow up in the REAL‐FR cohort. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(2):134‐137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Siafarikas N, Selbaek G, Fladby T, Saltyte Benth J, Auning E, Aarsland D. Frequency and subgroups of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and different stages of dementia in Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;1‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tatsumi H, Nakaaki S, Torii K, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms predict change in quality of life of Alzheimer disease patients: a two‐year follow‐up study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63(3):374‐384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG, Detroit Expert Panel on the Assessment and Management of the Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia . Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in clinical settings: recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):762‐769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng ST. Dementia caregiver burden: a research update and critical analysis. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(9):64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lorenzo‐Lopez L, de Labra C, Maseda A, et al. Caregiver's distress related to the patient's neuropsychiatric symptoms as a function of the care‐setting. Geriatr Nurs. 2017;38(2):110‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hongisto K, Hallikainen I, Selander T, et al. Quality of life in relation to neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: 5‐year prospective ALSOVA cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leon‐Salas B, Olazaran J, Cruz‐Orduna I, et al. Quality of life (QoL) in community‐dwelling and institutionalized Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57(3):257‐262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Lyketsos CG, Schneider LS. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer disease: cross‐sectional and longitudinal patient correlates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(10):917‐927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fauth EB, Gibbons A. Which behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are the most problematic? Variability by prevalence, intensity, distress ratings, and associations with caregiver depressive symptoms. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(3):263‐271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wetzels RB, Zuidema SU, de Jonghe JF, Verhey FR, Koopmans RT. Course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in residents with dementia in nursing homes over 2‐year period. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(12):1054‐1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Borsje P, Wetzels RB, Lucassen PL, Pot AM, Koopmans RT. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in community‐dwelling patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(3):385‐405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gauthier S, Cummings J, Ballard C, et al. Management of behavioral problems in Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):346‐372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peters ME, Schwartz S, Han D, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as predictors of progression to severe Alzheimer's dementia and death: the Cache County Dementia Progression Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(5):460‐465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lopez OL, Schwam E, Cummings J, et al. Predicting cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease: an integrated analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(6):431‐439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zahodne LB, Ornstein K, Cosentino S, Devanand DP, Stern Y. Longitudinal relationships between Alzheimer disease progression and psychosis, depressed mood, and agitation/aggression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(2):130‐140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scarmeas N, Brandt J, Blacker D, et al. Disruptive behavior as a predictor in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(12):1755‐1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Knapp M, Chua KC, Broadbent M, et al. Predictors of care home and hospital admissions and their costs for older people with Alzheimer's disease: findings from a large London case register. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e013591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, Wyman JF. Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med Care. 2009;47(2):191‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350(mar02 7):h369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brodaty H, Connors MH, Xu J, Woodward M, Ames D, PRIME Study Group . The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: a 3‐year longitudinal study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(5):380‐387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liperoti R, Pedone C, Corsonello A. Antipsychotics for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). Curr Neuropharmacol. 2008;6(2):117‐124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cummings J, Mintzer J, Brodaty H, et al. Agitation in cognitive disorders: International Psychogeriatric Association provisional consensus clinical and research definition. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(1):7‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van der Linde RM, Dening T, Stephan BC, Prina AM, Evans E, Brayne C. Longitudinal course of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(5):366‐377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lopez OL, Becker JT, Sweet RA, et al. Psychiatric symptoms vary with the severity of dementia in probable Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15(3):346‐353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Holtzer R, Tang MX, Devanand DP, et al. Psychopathological features in Alzheimer's disease: course and relationship with cognitive status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(7):953‐960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khoo SA, Chen TY, Ang YH, Yap P. The impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver distress and quality of life in persons with dementia in an Asian tertiary hospital memory clinic. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(12):1991‐1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676‐682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morris S, Patel N, Baio G, et al. Monetary costs of agitation in older adults with Alzheimer's disease in the UK: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e007382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Swearer JM, Hoople NE, Kane KJ, Drachman DA. Predicting aberrant behavior in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1996;9:162‐170. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Selbaek G, Engedal K, Benth JS, Bergh S. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing‐home patients with dementia over a 53‐month follow‐up period. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(1):81‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg‐Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurol. 1994;44(12):2308‐2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wilson J, Bock A. The benefit of using both claims data and electronic medical record data in health care analysis. 2014; Available at: https://www.optum.com/resources/library/benefit‐using‐both‐claims‐data‐electronic‐medical‐record‐data‐health‐care‐analysis.html. Accessed 17 April 2018.

- 38. Kern EF, Maney M, Miller DR, et al. Failure of ICD‐9‐CM codes to identify patients with comorbid chronic kidney disease in diabetes. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(2):564‐580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hansen ML, Gunn PW, Kaelber DC. Underdiagnosis of hypertension in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2007;298(8):874‐879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Golinvaux NS, Bohl DD, Basques BA, Grauer JN. Administrative database concerns: accuracy of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision coding is poor for preoperative anemia in patients undergoing spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(24):2019‐2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lovheim H, Sandman PO, Karlsson S, Gustafson Y. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in relation to level of cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(4):777‐789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]