Abstract

Context

Preparation for an impending death through end-of-life (EOL) discussions and human presence when a person is dying is important for both patients and families.

Objectives

The aim was to study whether EOL discussions were offered and to what degree patients were alone at time of death when dying from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), comparing deaths in nursing homes and hospitals.

Methods

The national Swedish Register of Palliative Care was used. All expected deaths from COVID-19 in nursing homes and hospitals were compared with, and contrasted to, deaths in a reference population (deaths in 2019).

Results

A total of 1346 expected COVID-19 deaths in nursing homes (n = 908) and hospitals (n = 438) were analyzed. Those who died were of a more advanced age in nursing homes (mean 86.4 years) and of a lower age in hospitals (mean 80.7 years) (P < 0.0001). Fewer EOL discussions with patients were held compared with deaths in 2019 (74% vs. 79%, P < 0.001), and dying with someone present was much more uncommon (59% vs. 83%, P < 0.0001). In comparisons between nursing homes and hospital deaths, more patients dying in nursing homes were women (56% vs. 37%, P < 0.0001), and significantly fewer had a retained ability to express their will during the last week of life (54% vs. 89%, P < 0.0001). Relatives were present at time of death in only 13% and 24% of the cases in nursing homes and hospitals, respectively (P < 0.001). The corresponding figures for staff were 52% and 38% (P < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Dying from COVID-19 negatively affects the possibility of holding an EOL discussion and the chances of dying with someone present. This has considerable social and existential consequences for both patients and families.

Key Words: COVID-19, dying alone, EOL discussions, nursing homes, hospital care

Key Message

Many patients are dying alone as coronavirus disease 2019 places restrictions on visits. Family members are seldom allowed to say goodbye. In addition, routines such as end-of-life discussions are negatively affected.

Background

The aspect of dying alone has received attention in patients dying from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), as the pandemic places restrictions on visits from family and friends. In the Stockholm region, for example, nursing homes and hospitals are advised to permit no more than one or two (noninfected) relatives to visit dying individuals. Elsewhere, in intensive care units, the restrictions might be even harder, with no visits allowed at all.1

Dying is often pictured as a lonely experience on several levels, of which interpersonal (social) and existential loneliness are the most prominent.2 Although bonds with family and friends may be strengthened during the trajectory of a life-threatening disease, actual social contacts may decrease because of increasing fatigue, leaving the dying person existentially alone. It remains though, that contacts are important. A research interview with a dying person captured the core essence of death and loneliness in the following way: Death and loneliness are in a way associated. Maybe one is scared of death, just because one is afraid that death will mean that you will become totally alone.2 Meanwhile, the dying individual has a need to love and to be loved, to forgive or be forgiven, and to sustain trusting and intimate relationships.3 It is, therefore, a universal wish not to die alone,4, 5, 6 although individual patients may prefer to do so.6 From the patient's point of view, the presence is especially important while still being conscious, whereas being present for the final hour might be symbolically important for family members.

For most people, dying is one of life's greatest challenges. A few of us might be mentally and existentially prepared, but most of us are not. For this reason, end-of-life (EOL) discussions and/or advance care planning (ACP) have become valuable tools in guiding the dying person and his or her family in the transition from a state of uncertainty to a state of understanding, sometimes together with acceptance. The possibility of closure and preparation for death are generally seen as quality of death measures.7 , 8 The desire to hold EOL discussions does not necessarily mean however that the patients make the actual decisions on their own. They want to be asked and involved but might want the physician to decide, in consultation with their family or friends.9 , 10

In Sweden, the term brytpunktssamtal is widely used and is, in essence, similar to EOL discussions and ACP.11 In a Swedish context however, EOL discussions generally occur late, sometimes just days before death,12 which is in contrast to international findings regarding EOL discussions and/or ACP.13 Still, they are considered valuable, and the National Board of Health and Welfare has listed EOL discussions as one of six quality indicators of palliative care.14

For these reasons, variables such as dying with someone present (including family, friends, staff, hospital chaplains etc.) and EOL discussions during the last week of life are registered in the Swedish Register of Palliative Care (SRPC), a nation-wide quality register of EOL care, which is completed online retrospectively in different care settings when a person has died. The SRPC, described previously, has been validated and currently includes coverage of about 60% of the approximately 90,000 annual deaths in Sweden.15 , 16

Aims

The aim was to study the occurrence of EOL discussions with patients and next of kin, whether patients died alone and whether family members were offered bereavement support, in relation to all reported COVID-19-related deaths in hospitals and nursing homes (data set retrieved on May 19, 2020), using the SRPC. Data from hospitals and nursing homes were compared, and the total data set was also compared with all deaths in similar facilities in 2019, assuming a null hypothesis (H0), that is, no differences between the groups.

Patients and Methods

The Methods and Results sections are reported based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology criteria.17

Study Design

We conducted a descriptive national registry data study using the SRPC to characterize all registered patients who died of COVID-19 either in nursing homes or hospitals, and we contrasted them to a similar year cohort before the pandemic (all expected deaths registered in the SRPC in 2019, occurring in nursing homes and hospitals).

Populations

Study Population

All registered patients who had died of COVID-19 during 2020 in nursing homes or hospitals (data retrieved on May 19, 2020), with expected deaths (n = 1346). Of these, 908 died in nursing homes and 438 in hospitals. The reason why expected deaths were chosen is that the SRPC holds detailed data on this group, for example, symptoms, symptom control, EOL discussions, and so on, during a patient's last week of life.

Reference Population

All expected deaths in nursing homes or hospitals were registered in the SRPC in 2019 (n = 33,451).

Variables and Data Source

For those patients in whom death was expected (n = 1346), an anonymized end-of-life questionnaire (ELQ) was completed, with 24 EOL questions, as well as information about the unit/service and the individual who completed the questionnaire. The ELQ was answered online retrospectively, as soon as possible after the patient's death, by the registered nurse and/or the physician responsible for EOL care. Swedish nursing homes are mainly staffed by assistant nurses; a smaller part are registered nurses. Physicians are mainly doing weekly visits or acute visits when needed. Swedish hospitals are staffed by not only registered nurses and physicians but also assistant nurses and paramedics.

The ELQ reflects the quality of care during the last week of life, and its completion was based on personal knowledge and data documented in the patient's records.

The questionnaire contains, for example, data about demographics and breakthrough symptoms, the degree of symptom relief during the last week of life, as well as information about EOL discussions. In this study, we focused on whether the patients had a retained ability to express their will during the last week on EOL discussions, whether they died with someone present, and whether relatives were offered follow-up talks (bereavement support).

Rating Scales

For most items, the answers were provided in a yes-no-do not know format, for example, for the occurrence of symptoms. In cases where symptoms occurred, symptom relief was graded in three alternatives: completely relieved—partly relieved—not relieved at all.

Selection Bias

Use of the SRPC is not mandatory, although it is strongly encouraged by governmental bodies. In total, about 60% of all deaths are reported from all services where deaths occur. In a year cohort, the coverage is highest for specialized palliative care (>90%), followed by nursing homes (75%) and hospitals (50%). Therefore, the proportion of deaths in nursing homes vs. hospitals does not reflect the absolute number of deaths (as somewhat fewer acute hospital departments report data).

Study Size

The study covers all reported COVID-19-related deaths (total cohort) that were expected and occurred in nursing homes or hospitals, until May 19, 2020.

Statistical Methods and Missing Data

A Chi-squared test and (two-tailed) t-test were used. For most questions, the option do not know was an alternative. Do not know answers were analyzed separately.

Results

COVID-19 Vs. Reference Population

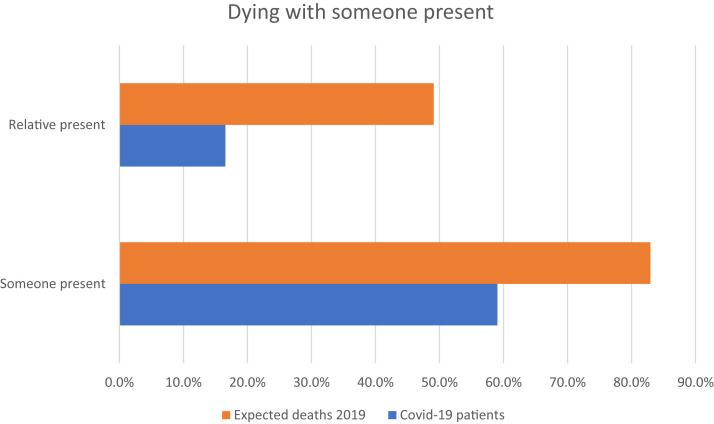

In Table 1 , demographics and symptom data are compared between 1346 expected deaths from COVID-19 and all registered nursing home and hospital deaths during 2019 (also expected deaths). Compared with the 2019 data, the proportion of females was lower (P < 0.0001), somewhat fewer of the COVID-19 patients had retained their ability to express their will during their last hours/days (P < 0.05), and fewer had been offered EOL discussions (P < 0.001). The greatest difference was seen for the variable dying with someone (family/relatives and/or staff) present, the figures for the COVID-19 2019 group were 59%, compared with 83% for the corresponding group in 2019 (P < 0.00001). The figures for family/relatives present were 17% and 50%, respectively (P < 0.00001) (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Table 1.

A Comparison Between Patients Deceased in COVID-19 and All Registered Deaths During 2019 for Patients Who Died in a Nursing Home or in a Hospitala (Only Expected Deaths in Both Columns)

| Characteristics | COVID-19 Patients, Nursing Homes, and Hospitals | All Registered Expected Deaths in 2019, Nursing Homes and Hospitals | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1346 | 33,450 | |

| Age; mean (range) | 84.5 (20–107) SD 8.73 | 84.5 (1–111) SD 9.86 | NS |

| Female sex (%) | 665/1346 (49) | 18,854/33,450 (56) | <0.00001 |

| Retained ability to express will day/days before death (%) | 835/1276 (65) | 21,390/31,429 (68) | <0.05 |

| EOL discussions with patients (%) | 889/1196 (74) | 24,195/30,637 (79) | <0.001 |

| EOL discussions with relativesc (%) | 1032/1233 (84) | 26,820/31,310 (86) | NS |

| Dying with someone present (%) | 753/1275 (59) | 27,176/32,752 (83) | <0.00001 |

| Dying with relative(s) present (%)d | 211/1275 (17) | 16,389/32,752 (50) | <0.00001 |

| Dying with staff presente | 600/1275 (47) | 16,088/32,752 (49) | NS |

| Offered follow-up talk with relatives (%) | 823/1039 (79) | 20,880/26,731 (78) | NS |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; NS = not significant; EOL = end of life.

I do not know was an option for most questions. Therefore, numbers may not sum to group totals.

P-values indicate differences between COVID-19 patients and all registered deaths in 2019. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Relatives could be family, relatives, and/or close friends.

Any relative present, with or without the presence of staff.

Staff present, with or without the presence of relatives.

Fig. 1.

Dying with someone present. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

COVID-19 in Nursing Homes Vs. Hospitals

Nursing homes and hospitals were contrasted in a separate analysis (Table 2 ). Nursing home patients were older (86.4 vs. 80.7 years, P < 0.0001) and were more often females (56% vs. 37%, P < 0.00001).

Table 2.

A Comparison Between Patients Deceased in COVID-19 in Nursing Homes or in Hospitals, for All Registered Expected Deaths (n = 1346)a

| Characteristics | Nursing Homes | Hospitals | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 908 | 438 | |

| Age; mean (range) | 86.4 (52–106) SD 7.37 | 80.7 (20–107) SD 9.98 | <0.0001 |

| Female sex (%) | 505/908 (56) | 160/438 (37) | <0.00001 |

| Retained ability to express will day/days before death (%) | 469/867 (54) | 366/409 (89) | <0.00001 |

| EOL discussion with patients (%) | 609/828 (74) | 280/368 (76) | NS |

| EOL discussion with relativesc (%) | 681/831 (82) | 351/402 (87) | <0.05 |

| Dying with someone present (%) | 516/845 (61) | 237/430 (55) | <0.05 |

| Dying with relative(s)c presentd (%) | 108/845 (13) | 103/430 (24) | <0.00001 |

| Dying with staff presente | 438/845 (52) | 162/430 (38) | <0.00001 |

| Offered follow-up talk with relativesc (%) | 599/731 (82) | 224/308 (73) | <0.001 |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; NS = not significant; EOL = end of life.

I do not know was an option for most questions. Therefore, numbers may not sum to group totals.

P-values indicate differences between patients deceased in nursing homes and hospitals. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Relatives could be family, relatives, and/or close friends.

Any relative present, with or without the presence of staff.

Staff present, with or without the presence of relatives.

Medical Care Decisions

We compared the ability for a patient to express their will and to take part in medical care decisions. Whereas 89% in hospital care retained their ability until the EOL, or at least until the hours or days before death, the corresponding figure for nursing homes was 54% (P < 0.00001).

EOL Discussions

There were no statistical differences in the proportion of EOL discussions for patients, whereas EOL discussions for relatives were more common in hospitals (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Dying Alone

In 61% of the cases, someone was present at time of death in a nursing home. For hospitals, the figure was 55%, meaning that 39% and 45% died alone, respectively. Family or relatives were present (with or without staff) in 13% of cases in nursing homes and in 24% in hospitals (P < 0.00001). In contrast, staff were present at time of death in 55% of cases in nursing homes and 38% in hospitals (P < 0.001).

Bereavement Support

An offer of follow-up talks to take place one to two months afterward was offered in conjunction with 82% of deaths in nursing homes and 73% in hospitals (P < 0.05).

I Do Not Know Answers

I do not know answers were analyzed separately (Table 3 ). The documentation concerning EOL discussions was considerably more inadequate in hospitals compared with nursing homes (P < 0.001). The most common I do not know option in both settings was regarding offers of follow-up talks. Whether this routine was carried out was not known in 19.7% of deaths in nursing homes and 30% in hospitals (P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Number of Cases per Item That Was Answered With Do Not Know for Deaths From COVID-19 in Nursing Homes Compared With Hospitals

| Items | Nursing Homes, n (%) | Hospitals, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ability to express will before EOL | 19/441 (4.3) | 12/192 (6.3) | NS |

| EOL discussion with patients | 30/441 (6.8) | 35/192 (18.2) | <0.001 |

| EOL discussion with relatives | 31/441 (7.0) | 19/192 (9.9) | NS |

| Dying—someone present | 31/441 (7.0) | 2/192 (1.0) | <0.01 |

| Offered follow-up talk with relatives | 87/441 (19.7) | 58/192 (30.0) | <0.01 |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; NS = not significant; EOL = end of life.

Discussion

Dying Alone

The present study revealed some important differences both when comparing patients deceased from COVID-19 with deaths in similar patient groups during 2019 and when comparing COVID-19 deaths at nursing homes with deaths at hospitals. In the former comparison, the greatest difference was for the variable dying with someone present. In 2019, the figure was 83%, whereas the figure for all COVID-19 patients was only 59%. When comparing nursing homes and hospitals, the figures were 61% and 55%, respectively.

Someone being present means that either family/relatives and/or staff (including hospital chaplains) or both were present at the time of death. When merely studying family or relatives being present, the figures were even more startling: only 13% in nursing homes and 24% in hospitals were present at the time of death. This was mainly because of the restraining orders, meaning that in many cases relatives were not actually allowed to be physically present. This was further hampered by the general travel restrictions in place, an important aspect when considering that approximately 20% of all Sweden's inhabitants (2 of 10 million Swedes) were born abroad. Relatives from abroad could not visit the dying person. Moreover, the sometimes rapid and unforeseeable deterioration made it more difficult to contact the patient's family or friends at the right moment, neither too early and neither too late.

As human presence is considered to be important in all cultures, the presence of staff would to some degree have compensated for this. Unfortunately, however this was not always the case; nursing home staff were present in 52% of deaths and hospital staff in only 38%, despite much better staffing levels.

The reasons for this remain unclear. Perhaps the low attendance was in some cases because of practical reasons, especially in acute hospitals where every attendance meant having to change protective equipment. In other cases, especially in nursing homes, a plausible reason could have been a fear of being infected with COVID-19. It should be born in mind that, at least initially, access to protective equipment because of a shortage of supply was much lower in Swedish nursing homes than in hospitals. Despite this, staff being unable to care for patients and families as they might wish, could also be a contributory factor in feelings of grief among the staff themselves.18

Moreover, a 100% presence of family and relatives may not be an ideal situation. Williams et al.19 argued, for example, that some individuals may not ascribe personal meaning to being with their loved one at the moment of death, particularly if the patient is perceived as socially dead already and, thus, no longer manifesting personal attributes or assuming social roles that constitute personhood, which may be the case in severe forms of dementia.

Regardless of the validity of the explanations, and with relatives and staff doing their best, this still leaves a considerable proportion of the patients dying alone.

For deeply unconscious patients, the presence of other people at the very moment of death is probably not important. However, a smaller proportion of the dying patients were conscious even during their last hours. Some of them might have preferred to die alone, as it is known that some dying individuals need solitude or want to protect their family from the actual moment of death.6 Meanwhile, though, most dying people would probably prefer someone to be present with them,6 a wish that does not seem to be fulfilled because of COVID-19.

Dying alone, however, is not only a social issue but also to a high degree an existential question both for the patient and for his or her family because the social and existential aspects are intimately intertwined. Existential loneliness (isolation) is an existential given, according to Yalom,20 an isolation that persists despite most gratifying engagements with other individuals. Yet aloneness can be shared in such a way that love compensates for the pain of isolation.20 Therefore, family being present is an important aspect of the EOL experience.

For family members, being forbidden to be present at the EOL for medical reasons makes the situation traumatic.21 Being present is in a symbolic way a time for lasts, it is a time for goodbyes.6 However, the family's presence implies much more than this: being present during the last hours means that the family can act as the patient's guardians and advocates, health historians, and informal caregivers.19 If the relatives are present it also means that, in general, the dying person receives more attention from the staff.19 But most importantly, being present is for most relatives experienced as something highly symbolic and is also a source of comfort during the bereavement process.19

EOL Discussions

There were somewhat fewer EOL discussions with patients in the COVID-19 group compared with the 2019 population, 74% and 79%, respectively. Meanwhile, EOL discussions might be even more important when helping people who are unlikely to survive COVID-19.21 With regard to EOL discussions with relatives, these were more commonly documented in the hospitals than in the nursing homes, 87% and 82%, respectively. The lower figure for EOL discussions with patients than with relatives is explained by the fact that a considerable proportion of residents in Swedish nursing homes suffer from cognitive failure, many of them having severe dementia.

Still, the possibility of EOL discussions is important, regardless of whether the conversations are initiated well before the very EOL, or whether they are performed during the last week of life. According to Ray et al.,22 awareness of prognosis is associated with better quality of death outcomes for patients as well as better bereavement outcomes for families. This is corroborated in a systematic review by Zwakman et al.23 who concluded that although discussions about ACP can be accompanied by unpleasant feelings, many patients report benefits as well. Moreover, ACP is also associated with fewer emergency department visits and fewer hospital deaths.13

To initiate EOL discussions is emotionally demanding. However, communication training might improve the outcome substantially, both with regard to the number of goals-of-care discussions and an increase in patient-rated quality of communication.24

A Good Death—Alone?

According to the British Geriatrics Society,25 a good death comprises the following aspects (Appendix in Ref. 25): To know when death is coming; to be able to retain control; to be afforded dignity and privacy; to have control over pain relief and other symptoms; to have choice and control over where it occurs; to have access to spiritual and emotional support; to have access to hospice, not only hospital care; to have control over who is present and who shares the end; to be able to issue advance directives, to have time to say goodbye; and to be able to leave when it is time to go and not have life pointlessly prolonged. Several of these issues were also corroborated in a review on defining a good death.5 For these reasons, EOL discussions fulfill an important function; they increase the person's awareness of their impending death; and if the message is conveyed in an empathetic way, it is a basis for future planning. Moreover, it allows the person to take a position on questions concerning treatments that might be futile. In the studied group, fewer COVID-19 patients received EOL discussions, compared with 2019.

Dying alone also has a substantial impact on the issues listed among the indicators of a good death. For example, to be in quarantine with extremely limited possibilities to receive visits from psychosocial/existential counselors or from hospital chaplains, results in limited or no existential/spiritual support. Not having the family present means no time to say goodbyes.

Strengths and Limitations

There are several strengths to this study: we used a national and validated quality register (SRPC) with approximately 60% coverage of all deaths in Sweden.15 , 16 As the register has been running since 2005, new data can be compared with data from previous years.

An obvious limitation is that the SRPC asks about being present at the time of death, instead of asking about being present during their final day. This means that in a situation where the attending nurse was present 20 minutes earlier, but not at the very moment of death, she or he would tick the box not present. This would also be the case, even if the patient was unconscious with regular breathing and everything was very peaceful when the nurse left the room for the last time.

Participation in the SPRC is voluntary. This means that we cannot comment on those 40% of deaths that were not registered. Moreover, a higher percentage of the registrations were from nursing homes than hospitals, which is an imbalance. In both settings, the ELQ is answered by registered nurses in most cases, but as the medical level of the staffing is higher in hospitals, this might affect the responses. As the SRPC has its main focus on expected deaths (even in cases where expected means that death was expected only for a few days), we do not have detailed data on those who died unexpectedly, which might be the case in some of the COVID-19 cases as sudden deaths are reported.

Conclusions

Dying from COVID-19 negatively affects the possibility of holding EOL discussions because of social distancing and restrictions on visits. It also affects the chance to die with someone present. This has considerable social and existential consequences, both for the dying patient and for his or her relatives in their bereavement process.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

The authors thank the SRPC for generously providing them with the data for the study. The Stockholm Sjukhem Foundation is acknowledged for providing excellent facilities in their Research & Development unit. David Boniface is acknowledged for linguistic revision.

Dr. Strang reports grants from the Stockholm Sjukhem Foundation's Jubilee Fund, Sweden, during the conduct of the study, and Dr. Bergström reports grants from the SRPC, Sweden during the conduct of the study. Dr. Martinsson and Dr. Lundström have nothing to disclose. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the National Ethics Authority (Etikprövningsmyndigheten, Dnr 2020-02,186).

Appendix. English Version of the Questionnaire Used for Registering Deaths in the SRPC Since January 1, 2018

| No. | Question | Reply Options |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unit identification code | |

| 2 | Personal identity number of the deceased person | |

| 3 | First and last name of the deceased person | |

| 4 | Date of death (year/month/day) Time of death (hour/minute) (optional data) |

|

| 5A | Date (year/month/day) when the person was admitted to the unit where the death occurred (for home care, please state the date when home care was initiated) | |

| 5B | Admitted from: |

|

| 6 | The place of death is best described as: |

|

| 7 | Disease/basic state that caused the death (more than one answer is possible): |

|

| 8 | Based on the disease trajectory, was the death expected? |

|

| 9 | How long before death did the person lose the ability to express his and/or her will and take part in decisions concerning the content of medical care? |

|

| 10A | Do the medical records include a documented decision by the physician responsible to shift treatment/care to EOL care? |

|

| 10B | Did the person receive information about the transition to EOL care, i.e., an individually tailored and informed conversation with a physician that is documented in the medical records about being in the final stage of life and about care being focused on quality of life and symptom relief? |

|

| 11 | Was the person's last expressed wish about place of death known? |

|

| 12A | Did the person have pressure ulcers on arrival at your unit (specify highest category occurring)? |

|

| 12B | Were the pressure ulcers documented? |

|

| 13A | Did the person die with pressure ulcers (specify highest category occurring)? |

|

| 13B | Were the pressure ulcers documented? |

|

| 14A | Was the person's oral health assessed and documented at any time during the last week of life? |

|

| 14B | Was any disorder noted during assessment? |

|

| 15 | Was anyone present at the time of death? |

|

| 16 | Did the person's close friend(s)/relative(s) receive information about transition to EOL care, i.e., an individually tailored and informed conversation with a physician that is documented in the medical records about being in the final stage of life and about care being focused on quality of life and symptom relief? |

|

| 17 | Was/were the person's close friend(s)/relative(s) offered a follow-up talk within one to two months of the death? |

|

| 18 | Did the person receive parenteral fluids/nutrition or enteral tube feeding during the last 24 hours of life? |

|

| 19 | Did the person display breakthrough of any of the following symptoms (19A–F) at any time during the last week of life? | |

| 19A | Pain |

|

| Pain was relieved: |

|

|

| 19B | Death rattle |

|

| Death rattle was relieved: |

|

|

| 19C | Nausea |

|

| Nausea was relieved: |

|

|

| 19D | Anxiety |

|

| Anxiety was relieved: |

|

|

| 19E | Dyspnea |

|

| Dyspnea was relieved: |

|

|

| 19F | Confusion |

|

| Confusion was relieved: |

|

|

| 20 | Was the person's pain assessed at any documented time during the last week of life using VAS, NRS, or another pain assessment tool? |

|

| 21 | Did the person experience severe pain at any time during the last week of life (e.g., VAS/NRS >6 or severe pain according to another pain assessment tool)? |

|

| 22 | Were the person's other symptoms assessed at any time during the last week of life using VAS, NRS, or another symptom assessment tool? |

|

| 23 | Was there an individual prescription of injectable PRN drugs on the drug list before death? | |

| Opioids against pain |

|

|

| Drugs against death rattle |

|

|

| Drugs against nausea |

|

|

| Drugs against anxiety |

|

|

| 24 | How long before death was the person last examined by a physician? |

|

| 25 | Were specialists outside the team/ward consulted concerning the person's symptom relief during the last week of life (more than one answer option is possible)? |

|

| 26 | How satisfied is the team with the care delivered to the person during the last week of life? | A five-point scale ranging from not at all (1) to completely (5) |

| 27 | Date (year/month/day) of answering the questions | |

| 28 | The questionnaire was answered by: |

|

| 29 | Name and e-mail address of registrant and occupation |

|

SRPC = Swedish Register of Palliative Care; EOL = end of life; VAS = visual analog scale; NRS = Numerical Rating Scale; PRN = pro re nata (as needed).

References

- 1.Wakam G.K., Montgomery J.R., Biesterveld B.E., Brown C.S. Not dying alone—modern compassionate care in the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2007781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sand L., Strang P. Existential loneliness in a palliative home care setting. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1376–1387. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rokach A., Matalon R., Safarov A., Bercovitch M. The loneliness experience of the dying and of those who care for them. Palliat Support Care. 2007;5:153–159. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507070228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granda-Cameron C., Houldin A. Concept analysis of good death in terminally ill patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2012;29:632–639. doi: 10.1177/1049909111434976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meier E.A., Gallegos J.V., Thomas L.P. Defining a good death (successful dying): literature review and a call for research and public dialogue. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.01.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson G., Shindruk C., Wickson-Griffiths A. “Who would want to die like that?” Perspectives on dying alone in a long-term care setting. Death Stud. 2019;43:509–520. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2018.1491484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downey L., Curtis J.R., Lafferty W.E., Herting J.R., Engelberg R.A. The Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire (QODD): empirical domains and theoretical perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wentlandt K., Burman D., Swami N. Preparation for the end of life in patients with advanced cancer and association with communication with professional caregivers. Psychooncology. 2012;21:868–876. doi: 10.1002/pon.1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waller A., Sanson-Fisher R., Nair B.R., Evans T. Preferences for end-of-life care and decision making among older and seriously ill inpatients: a cross-sectional study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergqvist J., Strang P. Breast cancer patients' preferences for truth versus hope are dynamic and change during late lines of palliative chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57:746–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.12.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundquist G., Rasmussen B.H., Axelsson B. Information of imminent death or not: does it make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3927–3931. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.6247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Udo C., Lovgren M., Lundquist G., Axelsson B. Palliative care physicians' experiences of end-of-life communication: a focus group study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2018;27:e12728. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirvonen O.M., Leskela R.L., Gronholm L. The impact of the duration of the palliative care period on cancer patients with regard to the use of hospital services and the place of death: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19:37. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00547-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Socialstyrelsen National guidelines—targets for quality indicators in palliative care by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (in Swedish) 2017. www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/nationella-riktlinjer/2017-10-22.pdf Available from.

- 15.Martinsson L., Heedman P.A., Lundstrom S., Axelsson B. Improved data validity in the Swedish Register of Palliative Care. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundstrom S., Axelsson B., Heedman P.A., Fransson G., Furst C.J. Developing a national quality register in end-of-life care: the Swedish experience. Palliat Med. 2012;26:313–321. doi: 10.1177/0269216311414758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandenbroucke J.P., von Elm E., Altman D.G. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology. 2007;18:805–835. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pattison N. End-of-life decisions and care in the midst of a global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;58:102862. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams B.R., Bailey F.A., Woodby L.L., Wittich A.R., Burgio K.L. “A room full of chairs around his bed”: being present at the death of a loved one in Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. Omega (Westport) 2012;66:231–263. doi: 10.2190/om.66.3.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yalom I. Basic Books, Inc.; New York: 1980. Existential psychotherapy. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yardley S., Rolph M. Death and dying during the pandemic. BMJ. 2020;369:m1472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray A., Block S.D., Friedlander R.J. Peaceful awareness in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1359–1368. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwakman M., Jabbarian L.J., van Delden J. Advance care planning: a systematic review about experiences of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness. Palliat Med. 2018;32:1305–1321. doi: 10.1177/0269216318784474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis J.R., Downey L., Back A.L. Effect of a patient and clinician communication-priming intervention on patient-reported goals-of-care discussions between patients with serious illness and clinicians: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:930–940. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.BGS Palliative and end of life care for older people. Br Geriatr Soc. 2020. https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/palliative-care Available from.