Abstract

Bisdemethoxycurcumin (BDMC) was a natural curcuminoid with many bioactivities present in turmeric (Curcuma longa L.). However, the disposition mechanisms of BDMC via uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) metabolism still remain unclear. Therefore, we aimed to determine the potential efflux transporters for the excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide. Herein, chemical inhibition assays (Ko143, MK571, dipyridamole, and leukotriene C4) and biological inhibition experiments including stable knocked-down of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRPs) transporters were both performed in a HeLa cell line stably overexpressing UGT1A1 established previously. The results indicated that Ko143 (5 and 20 μM) caused a marked reduction in excretion rate (18.4–55.6%) and elevation of intracellular BDMC-O-glucuronide (28.8–48.1%), whereas MK-571 (5 and 20 μM) resulted in a significant decrease in excretion rate (6.2–61.6%) and increase of intracellular BDMC-O-glucuronide (maximal 27.1–32.6%). Furthermore, shRNA-mediated silencing of BCRP transporter led to a marked reduction in the excretion rate (21.1–36.9%) and an obvious elevation of intracellular glucuronide (24.9%). Similar results were observed when MRP1 was partially silenced. In addition, MRP3 and MRP4 silencing both displayed no obvious changes on the excretion rate and intracellular levels of glucuronide. In conclusion, chemical inhibition and gene silencing results both indicated that generated BDMC-O-glucoside were excreted primarily by the BCRP and MRP1 transporters.

Keywords: BDMC, UGT1A1, glucuronidation, efflux transporters, HeLa cell

1. Introduction

Curcuminoids are a group of bioactive compounds present in turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) [1]. In addition, bisdemethoxycurcumin (BDMC) is one of the most abundant curcuminoids, which accounts for 0.011–0.087‰ weight of the dried rhizome [2]. And also, it has attracted increasing interest for various biological activities including antitumor, reduction of bone loss, hypoglycemic, and antioxidant activities [3-7]. For example, BDMC was considered as an effective inhibitor against aldoketo reductase 1B10 (a tumor marker) (Ki = 22 nM) with the efficient selectivity versus aldose reductase [3]. In addition, it was also potent as a matrix metalloproteinase-3 inhibitor which is a key enzyme with important implications in the invasion and metastasis of breast cancer cells (IC50 = 6 μM) [4]. Besides, BDMC could be a good drug candidate to reduce or control post-prandial hyperglycemia by binding and inactivation of human pancreatic α-amylase [5]. Furthermore, BDMC has been successfully encapsulated in liposomes and exhibited the roles in reducing osteoclast activity and maintaining osteoblast functions [6]. Recently, BDMC was efficiently resistant under microwave radiation [7].

Due to potential pharmaceutical applications, the in vivo and in vitro metabolism of BDMC has been studied extensively. Similar to curcumin and demethoxycurcumin, orally administered BDMC was poorly absorbed from the alimentary tract and present in the general blood circulation after largely being metabolized to the form of glucuronide (nearly 50 nM) and glucuronide/sulfate conjugates (about 10 nM) [8]. In addition, it is estimated that over 75% of ingested BMDC were excreted in feces without absorption while only traces appeared in urine based on the in vivo metabolism of curcumin and demethoxycurcumin [9-11]. Furthermore, to enhance the oral bioavailability of BDMC, different formulations, including microemulsion and phosphatidylcholine extracts were prepared to improve the curcuminoid absorption [12,13]. Approximately 50-fold greater absorption of BDMC has been observed in both rat and human studies following oral administration of a curcumin phosphatidylcholine complex compared to standard curcumin extract [14]. But despite all that, the biological properties of BDMC would be severely limited by low bioavailability resulting from the presence of massive curcuminoid glucuronide and sulfate conjugates in plasma [8], which indicated that glucuronidation is considered as the main clearance pathway for BDMC metabolism.

It is well-accepted that glucuronidation is important metabolic clearance pathway because the glucuronide is usually pharmacologically inactive and rapidly eliminated from the body due to its highly polar nature [15]. Previous studies have proved that numerous UGT1As and 2Bs enzymes participated in the glucuronidation of curcumin analogs [16]. Traditionally, the glucuronides were formed by UGT enzymes in cell, and the glucuronides were further transferred from intracellular to extracellular by efflux transporters [17]. Except the UGT enzymes, efflux transporters (e.g. BCRP and MRPs) also play a critical role in determining the oral bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of drugs undergoing glucuronidation [18,19]. Compared with glucuronidation by UGTs enzymes, drug disposition via efflux transporters pathway is poorly characterized. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the disposition mechanisms for BDMC via UGT metabolism.

In this study, we aimed to determine the efflux transporters for the excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide. Toward this goal, we adopted an previously established UGT1A1-overexpressing HeLa cells, which proved rather active in generation of the glucuronides [20-22], to evaluate the roles of BCRP and MRPs in the excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide. In addition, chemical inhibitors and short hairpin RNA-mediated silencing of BCRP and MRPs transporters assays were both employed to identify the active glucuronide transporters. Taken together, the results indicated that chemical inhibition and reduced biological expression of transporters led to suppressed glucuronidation of BDMC, revealing a strong dependence of cellular glucuronidation on the efflux transporters.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

The pLVX-mCMV-ZsGreen-PGK-Puro vector [9371 base pairs (bp)], and a pLVX-shRNA2-Neo vector (9070 bp) were obtained from BioWit Technologies (Shenzhen, China). Expressed human UGT1A1 was purchased from Corning Biosciences (New York). Alamethicin, β-estradiol, β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronide, dipyridamole (DIPY), D-saccharic-1,4-lactone, magnesium chloride (MgCl2), MK-571, Ko143, leukotriene C4 (LTC4), and uridine diphosphate glucuronic acid (UDPGA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). UGT1A1, GADPH, BCRP, MRP1, MRP3, and MRP4 antibodies were all purchased from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD). Bisdemethoxycurcumin was provided from Guangzhou Fans Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China). All other chemicals and reagents were of guaranteed reagent or the highest grade commercially available.

2.2. Construction of HeLa cells overexpressing UGT1A1 (HeLa1A1 cells)

Human UGT1A1 cDNA was synthesized and subcloned into the BamHI and MluI sites of the pLVXmCMV-ZsGreen-PGK-Puro vector. The recombinant vector was stably transfected into HeLa cells as previously described [20-22]. The expressions of UGT1A1 at mRNA and protein levels in HeLa1A1 cells were determined using the methods (qPCR and Western blotting) described in our previous studies [20-22]. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) value was determined by pilot experiments, and the optimal value was obtained when the cells were best transfected as described previously. In this study, the MOI value was 10 in stable transfection of HeLa1A1 cells.

2.3. shRNA-mediated silencing of BCRP and MRPs

The efflux transporters including BCRP, MRP1, MRP3, and MRP4 were expressed in HeLa cells [23]. We also have characterized the mRNA and protein expression of BCRP and three MRP transporters (MRP1, MRP3, and MRP4) in HeLa1A1 cells [20]. Therefore, previously established shRNA_BCRP, shRNA_MRP1, shRNA_MRP3, and shRNA_MRP4 plasmids were transiently transfected into HeLa1A1 cells following the procedures as described [20,21]. Western blotting was used to validate their effectiveness in reducing the expression of BCRP, MRP1, MRP3, or MRP4 protein as described previously [20,21]. After transfection for 48 h, HeLa1A1 cells were used for BDMC-O-glucuronide excretion experiments. The control scramble was used as a negative control.

2.4. BDMC-O-glucuronide excretion experiments

Glucuronide excretion assays were performed as described previously [20-22]. Briefly, HeLa1A1 cells were incubated with 2 mL Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS) containing 5 μM BDMC. Meanwhile, BDMC has no significant toxicities on the Hela cells within experimental concentration (maximal 8 μM) in this study, and the glucuronidation could be well evaluated. In addition, to determine the role of efflux transporters, Ko143 (5 and 20 μM), DIPY (5 and 20 μM), MK-571 (5 and 20 μM), and LTC4 (0.05 and 0.2 μM) were dissolved in HBSS solution to selectively inhibit the activity of BCRP or MRPs. At each time point (30, 60, 90, and 120 min), an aliquot of incubation solution (200 μL) was withdrew and immediately replenished with the same volume of a dosing solution. An equal volume of ice-cold acetonitrile was added and centrifuged at 13 800g for 10 min. The samples were subjected to ultra high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) analyses to calculate the excretion rate of BDMC-O-glucuronide and fraction metabolized (fmet) value of glucuronidation in HeLa1A1 cells. In addition, the cells were collected at 2 h and processed as described [20-22]. After centrifugation (13 800 g for 10 min), the supernatant was analyzed by UHPLC to measure the amounts of intracellular glucuronide of BDMC as previously described [20-22].

The excretion rate of intracellular BDMC-O-glucuronide was calculated according to the Equation 1. The apparent efflux clearance for BDMC-O-glucuronide was derived by ER/Ci, where Ci is the intracellular concentration of BDMC-O-glucuronide. The fmet value reflected the extent of BDMC-O-glucuronidation in the cells and was calculated as Equation 2. Where V is the volume of the incubation medium; C is the cumulative concentration of BDMC-O-glucuronide; and t is the incubation time. Here, dC/dt describes the changes of the BDMC-O-glucuronide levels with time.

| (1) |

| (2) |

2.5. HeLa1A1 cell lysate preparation

HeLa1A1 cells grown in 10-cm dishes were collected in Tris buffer (50 mM) and lysed by homogenization using a tight-fitting Dounce homogenizer. Cell homogenates were centrifuged at 13 800 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant fraction containing the expressed UGT1A1 enzyme was collected and stored at −80 °C until use. Total protein concentration in HeLa1A1 cell lysate was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China).

2.6. Glucuronidation assays by expressed UGT1A1 and HeLa1A1 cell lysate

Glucuronidation activities of BDMC by expressed UGT1A1 and the HeLa1A1 cell lysate were measured following our published procedures [24]. In brief, the incubation system (200 μL) contained recombinant UGT1A1 (1.0 mg/mL) or HeLa1A1 cell lysate (9.2 mg/mL), MgCl2 (4 mM), alamethicin (20 μg/mL), and BDMC in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH = 7.4). After preincubation at 37 °C for 5 min, the reaction was initiated by the addition of 100 mM UDPGA. And the incubation was continued for another 60 min. The specific transporter inhibitor (Ko143, DIPY, MK-571, or LTC4), whenever applied, was included in the incubation mixture to examine their influences on the glucuronidation activities of BDMC [20,22]. After incubation for 1 h, the reaction was terminated using ice-cold acetonitrile (200 μL). After vortex, the incubation mixture was centrifuged at 13800 g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and subjected to UHPLC analysis.

To fully characterize the enzyme kinetics of glucuronidation reactions, various concentrations of BDMC (0.25–40 μM) were incubated with recombinant UGT1A1 or HeLa1A1 cell lysate in the presence of an equal amount of UDPGA as described above. Kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax, and CLint) for BDMC-O-glucuronidation were generated by using the Michaelis–Menten model as Equation 3. Appropriate model was also selected by visual inspection of the Eadie–Hofstee plot [25]. Model fitting and parameter estimation were performed by Graphpad Prism V5 software (SanDiego, CA).

| (3) |

2.7. Analytical conditions

Quantification of BDMC-O-glucuronide was performed using an Acquity™ UHPLC I-Class system (Waters Corporation, Manchester, UK) equipped with a BEH C18 column (2.1 mm × 50 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters, Ireland, Part NO. 186002350) at 35 °C. BDMC and BDMC-O-glucuronide were separated using water and acetonitrile (both including 0.1% formic acid, V/V) as mobile phase at 0.4 mL/min. The gradient elution program was 5% B from 0 to 0.5 min, 5–60% B from 0.5 to 1.7 min, 60% B from 1.7 to 2.0 min, 60–90% B from 2.0 to 2.8 min, maintaining 90% B from 2.8 to 3.0 min, 90–5% B from 3.0 to 3.5 min, keeping 5% B from 3.5 to 4.0 min. The detection wavelength was at 338 nm.

UHPLC system was coupled to a hybrid quadrupole orthogonal time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometer (SYNAPT™ G2 HDMS, Waters, Manchester, UK) with electrospray ionization (ESI). The operating parameters were as follows: capillary voltage, 3 kV (ESI+); sample cone voltage, 35 V; extraction cone voltage, 4 V; source temperature, 100 °C; desolvation temperature, 300 °C; cone gas flow, 50 L/h and desolvation gas flow, 800 L/h. The full scan mass range was 50–1500 Da. The method employed lock spray with leucine enkephalin (m/z 556.2771 in positive ion mode) to ensure mass accuracy.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. The assay data are presented as the mean ± SD (standard deviation). Mean differences between treatment and control groups were analyzed by Student’s t test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05 (*) or P < 0.01 (**), or P < 0.001 (***).

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of UGT1A1-overexpressing HeLa cells (HeLa1A1 cells)

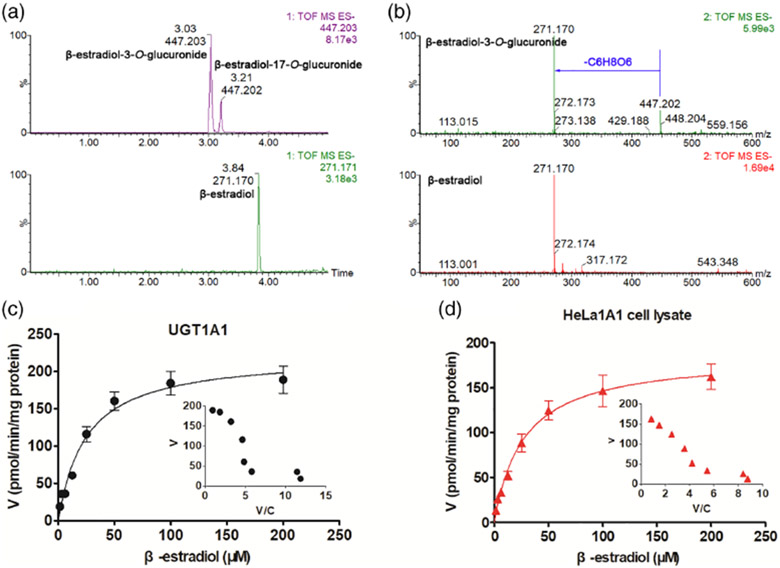

UGT1A1 cDNA was subcloned into the BamHI and MluI sites of the pLVXmCMV-ZsGreen-PGK-Puro vector. Digestion of the lentiviral vector by restriction enzymes above produced a fragment of 1602 bp that corresponded well to the cDNA of UGT1A1 as shown previously [20]. The HeLa cells were obtained by puromycin selection after transducing the lentiviral particles (containing the recombinant vector) into the wild-type HeLa cells. The qPCR analysis of HeLa1A1 cells showed a obvious band of UGT1A1, indicating that the gene was integrated into the cell genome as published previously [20]. Meanwhile, western blotting results showed that the UGT1A1 protein was found significantly in HeLa1A1 cells [20]. In addition, the HeLa1A1 cells were rather active in generation of the glucuronides after incubation with wushanicaritin, chrysin, genistein, apigenin, and so on [20-22]. Furthermore, β-estradiol, the specific substrate of UGT1A1 enzyme, was used to confirm the overexpressing of UGT1A1 enzymes in HeLa cells. As shown in Figs. 1A and 1B, β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronide and β-estradiol-17-O-glucuronide were obviously generated after incubation of β-estradiol with HeLa1A1 cell lysate. Moreover, the kinetic profiles of β-estradiol by UGT1A1 (Fig. 1C) and HeLa1A1 cell lysate (Fig. 1D) both followed classical Michaelis–Menten equation. The Km values were simimlar with previous study [24], while the Vmax and CLint values showed significant differences (P < 0.05) by UGT1A1 and HeLa1A1 cell lysate (Table 1). Taken together, these results indicated that the engineered HeLa1A1 cells significantly expressed active UGT1A1 protein and could functionally catalyze the glucuronidation reaction.

FIG 1.

UGT1A1 catalyzed the formation of β-estradiol-O-glucuronides. (A) Extracted ion chromatograms of β-estradiol and β-estradiol-O-glucuronides in negative ion mode; (B) MS/MS spectra of β-estradiol and β-estradiol-O-glucuronides in negative ion mode; (C) Kinectic profiles for β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronidation by UGT1A1; (D) Kinectic profiles for β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronidation by HeLa1A1 cell lysate; In each panel, the insert figure showed the corresponding Eadie–Hofstee plot.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters derived from β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronide and BDMC-O-glucuronidation by UGT1A1 enzyme and HeLa1A1 cell lysate supplemented with UDPGA

| Substrate | Enzyme | Vmax (pmol/min/mg) | Km (μM) | CLint (μL/min/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-estradiol | UGT1A1 | 222.80 ± 10.56 | 24.62 ± 3.01 | 9.05 ± 1.18 |

| β-estradiol | HeLa1A1 cell lysate | 186.20 ± 5.63** | 27.12 ± 2.51 | 6.87 ± 0.67* |

| BDMC | UGT1A1 | 1406.00 ± 67.15 | 5.99 ± 0.83 | 234.80 ± 34.52 |

| BDMC | HeLa1A1 cell lysate | 1203.00 ± 49.94# | 7.33 ± 0.83 | 164.16 ± 19.84# |

Data are represented by Mean ± SD. CLint, the intrinsic clearance; Km, the Michaelis constant; Vmax, the maximal velocity.

Compared with the parameters by UGT1A1 enzyme.

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001).

3.2. Expression of efflux transporters in HeLa and HeLa1A1 cells

As described previously, both mRNA and the proteins of BCRP, MRP1, MRP3, and MRP4 were detected in both HeLa and HeLa1A1 cells, whereas those of MRP2 were not found [20,23]. These results indicated that the wild-type and engineered cells showed an identical pattern in transporter expression.

In addition, four constructed shRNA fragments (i.e. BCRP-shRNA, MRP1-shRNA, MRP3-shRNA and MRP4-shRNA) were applied to develop stable transporter knocked-down HeLa1A1 cell lines using the lentiviral transfection method as published previously [20]. Meanwhile, the knockdown efficiency (mRNA and protein levels) of transporter protein in HeLa1A1 cells was verified to be about 30%, which was similar to our previous results [20,22].

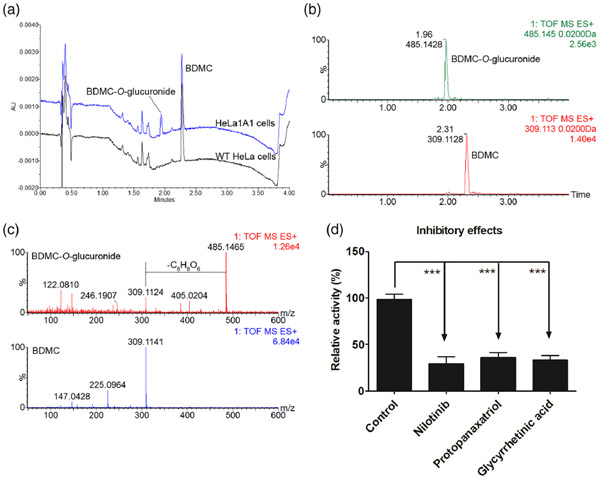

3.3. Glucuronidation of BDMC by UGT1A1 and HeLa1A1 cell lysate

After incubation of BDMC (tR = 2.31 min) with HeLa1A1 cell lysate and HeLa cell lysate, an additional peak (tR = 1.96 min) was obviously produced in engineered HeLa1A1 cells (Fig. 2A). It was noted that the metabolite (m/z 485.1428) was with a mass larger of 176.031 Da than that of BDMC (m/z 309.1128) (Figs. 2B and 2C). Hence, the metabolite was characterized as BDMC-O-glucuronide. In addition, the rates of BDMC-O-glucuronidation were altered by several UGT1A1 inhibitors [26,27], nilotinib (10 μM), protopanaxatriol (500 μM) and glycyrrhetinic acid (20 μM) (Fig. 2D). Therefore, UGT1A1 was determined as a main contributor for BDMC-O-glucuronidation.

FIG 2.

UGT1A1 catalyzed the formation of BDMC-O-glucuronide. (A) UHPLC chromatograms of BDMC and BDMC-O-glucuronide; (B) Extracted ion chromatograms of BDMC and BDMC-O-glucuronide in positive ion mode; (C) MS/MS spectra of BDMC and BDMC-O-glucuronide in positive ion mode. (D) Inhibitory effects of nilotinib (10 μM), protopanaxatriol (500 μM), and glycyrrhetinic acid (20 μM) on BDMC-O-glucuronidation by UGT1A1. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001 compared with that of control.

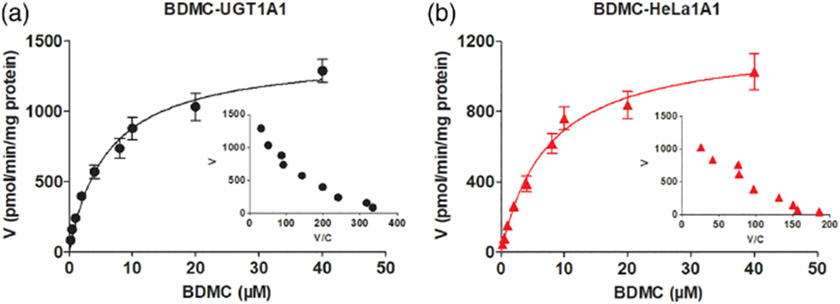

Furthermore, it was noted that BDMC-O-glucuronidation of by UGT1A1 (Fig. 3A) and HeLa1A1 cell lysate (Fig. 3B) both followed the Michaelis–Menten kinetics. Meanwhile, the glucuronidation in HeLa1A1 cell lysate was close (with close Vmax, Km, and CLint values) that in UGT1A1 enzyme (Table 1). The reason may be that the protein concentration (9.2 mg/mL) in HeLa1A1 cell lysate was obviously higher than that in UGT1A1 enzyme (1.0 mg/mL).

FIG 3.

UGT1A1 catalyzed BDMC-O-glucuronidation by UGT1A1 enzyme and HeLa1A1 cell lysate. (A) Kinectic profiles for BDMC-O-glucuronidation by UGT1A1; (B) Kinectic profiles for BDMC-O-glucuronidation by HeLa1A1 cell lysate; In each panel, the insert figure showed the corresponding Eadie-Hofstee plot.

3.4. Concentration-dependent excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide in HeLa1A1 cells

As shown in Fig. 3B, BDMC-O-glucuronide was efficiently generated and excreted after incubation of BDMC with the HeLa1A1 cells. With the increase in the concentration of BDMC, the excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide markedly increased (Fig. 4A). The excretion rates at a concentration of 2 and 8 μM for BDMC-O-glucuronide were 4.33 and 7.74 pmol/min, respectively (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Concentration-dependent excretions of BDMC-O-glucuronide in HeLa1A1 cells. (A) Accumulated BDMC-O-glucuronide in extracellular medium at different concentration (2 and 8 μM) of BDMC; (B) Comparisons of excretion rates of BDMC-O-glucuronide at two substrate concentrations. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001 compared with that of BDMC at 2 μM.

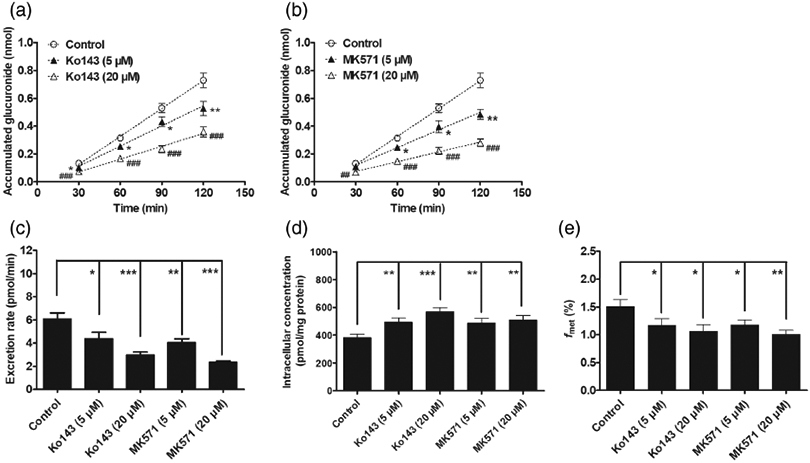

3.5. Effects of chemical inhibitors on excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide in HeLa1A1 cells

It is widely accepted that Ko143 and MK571 were specific inhibitors for BCRP and MRPs transports, respectively [20,22], whereas DIPY and LTC4 were also used to inhibit the activities of BCRP and MRPs transports, respectively [28,29]. In this study, BDMC-O-glucuronide excretion was significantly decreased by Ko143 (5 and 20 μM) (18.4–55.6%) as well as MK-571 (5 and 20 μM) (6.2~61.6%) (Figs. 5A-5C). By contrast, the intracellular levels of BDMC-O-glucuronide were significantly increased by Ko143 (28.8–48.1%) and MK571 (27.1–32.6%) (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, chemical inhibition of BCRP or MRPs led to a decrease in the extent of BDMC-O-glucuronidation (maximal 33.2%) (Fig. 5E). The results indicated that the efflux transporters BCRP and MRPs were involved in the excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide. Also, these efflux transporters were capable of modifying cellular BDMC-O-glucuronidation.

FIG 5.

Efflux transporter inhibitors Ko143 (5 and 20 μM) and MK571 (5 and 20 μM) inhibit the generation and excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide in HeLa1A1 cells. (A) Ko143 (5 and 20 μM) inhibited the accumulation of BDMC-O-glucuronide in extracellular medium; (B) MK571 (5 and 20 μM) inhibited the accumulated BDMC-O-glucuronide in extracellular medium; (C) Ko143 and MK571 decreased the efflux rates of BDMC-O-glucuronide; (D) Ko143 and MK571 evaluated the intracellular levels of BDMC-O-glucuronide; (E) Ko143 and MK571 reduced the formation of BDMC-O-glucuronide in HeLa1A1 cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *,#P < 0.05, **,##P < 0.01 and ***,###P < 0.001 compared with that of control.

Accordingly, the inhibition of BCRP by DIPY (5 and 20 μM) also led to a significant increase in intracellular glucuronide levels (20.5–25.4%) (Fig. 6D) as well as a reduction in the excretion (8.4–36.5%) of BDMC-O-glucuronide (Figs. 6A and 6C). By contrast, the inhibition of MRP by LTC4 (0.05 and 0.2 μM) did not show any effects on the formation (Fig. 6D) and excretion (Figs. 6B and 6C) of BDMC-O-glucuronide. Taken together, the results indicated that BCRP and MRPs both played dominant roles in excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide.

FIG 6.

Effects of dipyridamole (5 and 20 μM) and LTC4 (0.05 and 0.2 μM) on the generation and excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide in HeLa1A1 cells. (A) DIPY (5 and 20 μM) inhibited the accumulation of BDMC-O-glucuronide in extracellular medium; (B) LTC4 (0.05 and 0.2 μM) did not altered the accumulated BDMC-O-glucuronide in extracellular medium; (C) DIPY reduced the efflux rates of BDMC-O-glucuronide at 20 μM, while LTC4 did not changed the the efflux rates of BDMC-O-glucuronide; (D) DIPY evaluated the intracellular levels of BDMC-O-glucuronide, whereas no changes were observed after treatment with LTC4; (E) DIPY decreased the formation of BDMC-O-glucuronide, while there were no significant differences between control and LTC4 group in HeLa1A1 cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *,#P < 0.05, **,##P < 0.01 and ***,###P < 0.001 compared with that of control.

3.6. Effects of chemical inhibitors on BDMC-O-glucuronidation activities

Our previous studies have suggested that chemical inhibitors of efflux transporters could inhibit or induce the enzymatic activities of phase II enzymes [20,22]. To better understand the interpretation of inhibition data of metabolite excretion, we investigate whether Ko143, MK-571, DIPY, and LTC4 would modulate the BDMC-O-glucuronidation activities of UGT1A1. The results suggested that Ko143 (5 and 20 μM), MK-571 (5 and 20 μM), and DIPY (5 and 20 μM) all could inhibit the glucuronidation of BDMC by UGT1A1 enzyme (Fig. 7A) and HeLa1A1 cell lysate (Fig. 7B), whereas LTC4 had no influences on the glucuronidation reactions by UGT1A1 and HeLa1A1 cell lysate (Figs. 7A and 7B).

FIG 7.

Chemical inhibitors Ko143 (5 and 20 μM), MK571 (5 and 20 μM) and dipyridamole (5 and 20 μM) showed inhibitory effects on BDMC-O-glucuronidation activity, while LTC4 (0.05 and 0.2 μM) did not altered the glucuronidation activity by UGT1A1 (A) and HeLa1A1 cell lysate (B). Data were presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001 compared with that of control.

3.7. Effects of transporter knock-down on the excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide in HeLa1A1 cells

The results indicated that knock-down of BCRP resulted in an obvious reduction in intracellular BDMC-O-glucuronide (24.9%) (Fig. 8C) as well as the excretion rate (21.1–36.9%) (Figs. 8A and 8B). In addition, similar observations were also detected in the excretion rate (14.1–29.5%) (Figs. 8A and 8B) and intracellular BDMC-O-glucuronide (32.7%) (Fig. 8C) after shRNA-mediated silencing of MRP1 transporter. Besides this, marked decreases in the fmet values were observed when BCRP and MRP1 transporters were inhibited (Fig. 8D), which also suggested that BCRP and MRP1 played critical roles in the excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide. Furthermore, MRP3 and MRP4 transporters silencing did not cause any changes in the excretion rate (Figs. 8A and 8B), intracellular levels (Fig. 8C) and the fmet values (Fig. 8D). Taken together, the results clearly indicated that BCRP and MRP1 were the important contributors to the excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide.

FIG 8.

Effects of shRNA-mediated silencing of BCRP, MRP1, MRP3 and MRP4 on the excretion rates and intracellular levels of BDMC-O-glucuronide in HeLa1A1 cells. (A) Effects of BCRP or MRP1 siliencing on the accumulated BDMC-O-glucuronide in extracellular medium; (B) Effects of MRP3 or MRP4 siliencing on the accumulation of BDMC-O-glucuronide in extracellular medium; (C) Excretion rates of BDMC-O-glucuronide after knock-down of BCRP, MRP1, MRP3, or MRP4 transporters; (D) The intracellular concentrations of BDMC-O-glucuronide when BCRP, MRP1, MRP3, or MRP4 transporters were inhibited; (E) The generation of BDMC-O-glucuronide in HeLa1A1 cells after siliencing BCRP, MRP1, MRP3, or MRP4 transporters; Data were presented as mean ± SD. *,#P < 0.05, **,##P < 0.01, and ***,###P < 0.001 compared with that of control.

4. Discussion

BDMC was reported with many biological properties including antitumor, reduction of bone loss, hypoglycemic, and antioxidant activities [3-7]. However, poor oral bioavailability resulting from the presence of massive curcuminoid glucuronide and sulfate conjugates in plasma [8] limited the significant activities of BDMC. In this study, the disposition of BDMC was characterized using the engineered HeLa1A1 cells [20-22]. The results demonstrated that UGT1A1 was subjected to β-estradiol-3-O-glucuronide (Fig. 1 and Table 1) and BDMC-O-glucuronidation in HeLa1A1 cells (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Furthermore, we provided strong evidences that both BCRP and MRP1 were actively involved in the excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide (Figs. 5 and 8), which. Therefore, these results also contributed significantly to a deep understanding of the mechanisms for cellular disposition of BDMC via UGT metabolism.

Ko143 (a specific inhibitor of BCRP) has gained widespread use in inhibiting the transport activity of BCRP in the literature [20,22]. In this study, Ko143 showed significant inhibitory effects on the glucuronidation activity (Fig. 7), which was consistent with previous studies [20,22]. Thus, the decreased glucuronide excretion cannot be simply ascribed to a reduced BCRP activity. This was because suppressed metabolism would also lead to a reduction in glucuronide excretion. In addition, DIPY, also as a BCRP inhibitor, was relatively limited for evaluating the role of BCRP [28]. The results exhibited that DIPY could decrease the efflux clearance of BDMC-O-glucuronide (Fig. 6). Compared with Ko143 (IC50 = 23 nM), DIPY was a much weaker inhibitor with IC50 value of 6.4 μM in inhibiting the efflux transport of mitoxantrone as a BCRP inhibitor [28,30].

Similarly, use of MK-571 (a pan-MRP inhibitor) resulted in a reduction in both the efflux excretion and efflux clearance (Fig. 5). The results collectively indicated that MRPs transporters played an important role in transporting BDMC-O-glucuronide out of cells. However, MK-571 also exhibited the inhibitory effects on the transport activity of BCRP [31]. Meanwhile, the inhibitory effect of MK-571 for MRPs were more significant than that for MRP2 [31]. Besides, LTC4 was also a high-affinity substrate for MRP1 and MRP2 (Km = 0.1–1 μM) [29]. But the results displayed that LTC4 did not cause alterations in either glucuronidation activity or BDMC-O-glucuronide excretion (Figs. 6 and 7). Similar observations have been also noted in a previous studies [20,22]. Therefore, it remains to be clarified whether LTC4 could be considered as an effective inhibitor of MRPs.

Identification of efflux transporters responsible for glucuronide excretion by chemical inhibitors should be treated with caution due to their potential in modification of the glucuronidation activity. Therefore, another independent assay involving in biological knock-down of efflux transporters were performed to investigate the excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide. The mRNA and protein levels of BCRP and MRPs were obviously reduced after qPCR and western blotting results [20,22]. Furthermore, the excretion of glucuronide significantly decreased (Fig. 8), followed shRNA-mediated gene silencing of BCRP and MRP1 transporters, which suggested that both BCRP and MRP1 were the main contributors. This approach was more advantageous compared to chemical inhibition assays, because the inhibition of efflux transporters were more practical and effective. Not surprisingly, there is an important limitation for the capability of MRP2 in this study due to the absence of MRP2 in HeLa cells [23]. Previous study provided an effective tool to pump out all the conjugates formed within the cells by the relevant phase II enzymes such that the amount of metabolites generated are the same regardless if the cells were intact or not (after adjusting for amount of enzymes in the reactions) in MDCKII-MRP2/UGT1A1 cells [32]. The roles of MRP2 in the disposition of BDMC-O-glucuronide was still unknown and remained to be further determined.

In contrast, although BDMC-O-glucuronide was excreted by BCRP and MRP1, BDMC may exhibited the inhibitory effects on these efflux transporters. For example, curcumin, a BDMC analogue, was a potent BCRP inhibitor in vitro with Ki value of (0.70 ± 0.41) μM, and also could increase the area under the curve (AUC)0–8 of plasma sulphasalazine eight-fold in wild-type and bcrp(−/−) mice [33,34], and in cynomolgus monkeys [35]. These findings were opposite with previous observation that curcumin showed a strong effect on BCRP induction in MCF-7 wild-type cells but no response in AhR deficient MCF-7AHR200 cells [36]. In addition, curcumin also could inhibit the expression of MRP1 in a concentration dependent manner in Y79 cells [37]. Besides, it was reported that curcumin inhibited drug efflux and increased the efficacy of many anticancer agents in multidrug-resistant cancers [38]. Moreover, curcumin and demethoxycurcumin could inhibit P-gp but BDMC may modulate the function of other efflux transporters such as MRPs [39,40]. This complex interplay between transporters inhibition and metabolism of transporters inhibitors, the latter affecting the ultimate potential of a compound for cellular transporter inhibition, may exist not only for a compound like curcumin or BDMC but also for many other transporter inhibitors.

In addition, the efflux transporter-glucuronide interaction complicated the efforts to predict the glucuronidation, and gave the rise to the “glucuronidation-transporter interplay” phenomenon [41]. This interplay facilitated the production and excretion of glucuronides in the intestine and liver, limiting the oral bioavailability of drugs. As described previously, de-glucuronidation (also called futile recycling) in cells by β-glucuronidase was necessary for the interplay between glucuronidation and glucuronide efflux to occur [20,22,41]. The inhibition of glucuronide efflux certainly resulted in accumulation of intracellular glucuronide, whereas a rise in intracellular glucuronide was closely associated with an increase in the rate of futile recycling [20,41]. The evaluated intracellular glucuronide levels were most likely the result of the increased impact of β-glucuronidase activity in the cells with the partial transporter siliencing as opposed to the control cells. These results also indicated that de-glucuronidation was a critical determinant to the intracellular accumulation of drugs or their glucuronides.

Moreover, it was noteworthy that obtain of transport kinetics was important for determining the contribution of efflux transporters to drug or its glucuronide disposition in vivo, and/or in evaluating the rate-limiting step (metabolism vs excretion) of cellular glucuronide production. Usually, the corresponding kinetic parameters of efflux transporters including Km, Vmax, and Clint values were obtained based on the transport experiments using plasma membrane (inside-out) vesicles which contained massive efflux transporters [42]. But due to lack of commercial availability of the glucuronides, this assay was limited in the requirement to use purified efflux transporter substrates for experimentation. In this study, a previously established engineered HeLa1A1 cells was applied to kinetically determine the involvment of BCRP and MRPs-mediated transport of BDMC-O-glucuronide [20-22,41]. This approach was more advantageous because it avoided the use of purified glucuronide. Meanwhile, this method was validated theoretically based on the pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation, and HeLa1A1 cells were successfully applied for the evaluation of BCRP and MRPs in the excretion of wushanicaritin, chrysin, genistein, apigenin [20-22,41]. Another important advantage was that HeLa1A1 cells expressing an array of transporters (BCRP, MRP1, MRP3, and MRP4) were a closer mimic of the in vivo situations [23].

In conclusion, the previously engineered HeLa1A1 cells were fully active in catalyzing BDMC-O-glucuronidation reaction (Fig. 1). Besides, the glucuronidation by UGT1A1 and HeLa1A1 cell lysate both followed the classical Michaelis–Menten kinetics (Fig. 2). In addition, the excretion rates of BDMC-O-glucuronide were in a dose-dependant manner (Fig. 3). Futhermore, chemical inhibitors Ko143, MK571, and DIPY caused a significant reduction in the excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide (Figs. 4 and 5), whereas LTC4 did not changed the excretion rates of glucuronide (Fig. 5). Similar observations were obtained in the effects of chemical inhibitors on the BDMC-O-glucuronidation (Fig. 6). Moreover, by employing biological inhibition methods, BCRP and MRP1 led to significant alterations of excretion and intracellular levels of BDMC-O-glucuronide (Fig. 7), which revealed that both BCRP and MRP1 were actively involved in excretion of BDMC-O-glucuronide. Taken together, this study provided alternative HeLa1A1 cell lines to determine the exact contributions of efflux transporters to glucuronide excretion and to study the glucuronidation–transport interplay.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by National Major Scientific and Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (No. B13038), State Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (81630097) and Hospital Youth Foundation of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (YNQN2017200).

Abbreviations:

- BCRP

breast cancer resistance protein

- BDMC

bisdemethoxycurcumin

- DIPY

dipyridamole

- HBSS

Hank’s buffered salt solution

- LTC4

leukotriene C4

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- MRP

multidrug resistance-associated protein

- UDPGA

uridine diphosphate glucuronic acid

- UGT

uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase

- UHPLC

ultra high-performance liquid chromatography

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

All the authors report no declarations of interest.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- [1].Li R, Xiang C, Ye M, Li HF, Zhang X, et al. (2011) Qualitative and quantitative analysis of curcuminoids in herbal medicines derived from curcuma species. Food Chem. 126, 1890–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shen Y, Han C, Chen X, Hou X, and Long Z (2013) Simultaneous determination of three curcuminoids in curcuma wenyujin y.H.Chen et c.Ling. By liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry combined with pressurized liquid extraction. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal 81-82, 146–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Matsunaga T, Endo S, Soda M, Zhao HT, El-Kabbani O, et al. (2009) Potent and selective inhibition of the tumor marker akr1b10 by bisdemethoxycurcumin: probing the active site of the enzyme with molecular modeling and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 389, 128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Boonrao M, Yodkeeree S, Ampasavate C, Anuchapreeda S, and Limtrakul P (2010) The inhibitory effect of turmeric curcuminoids on matrix metalloproteinase-3 secretion in human invasive breast carcinoma cells. Arch. Pharm. Res 33, 989–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ponnusamy S, Zinjarde S, Bhargava S, Rajamohanan PR, and RaviKumar A (2012) Discovering bisdemethoxycurcumin from curcuma longa rhizome as a potent small molecule inhibitor of human pancreatic α-amylase, a target for type-2 diabetes. Food Chem. 135, 2638–2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yeh CC, Su YH, Lin YJ, Chen PJ, Shi CS, et al. (2015) Evaluation of the protective effects of curcuminoid (curcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin)-loaded liposomes against bone turnover in a cell-based model of osteoarthritis. Drug Des. Devel. Ther 9, 2285–2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jung YN, Kang S, Lee BH, Kim JH, and Hong J (2016) Changes in the chemical properties and anti-oxidant activities of curcumin by microwave radiation. Food Sci. Biotechnol 25, 1449–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Asai A, and Miyazawa T (2000) Occurrence of orally administered curcuminoid as glucuronide and glucuronide/sulfate conjugates in rat plasma. Life Sci. 67, 2785–2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zeng Y, Qiu F, Liu Y, Qu G, and Yao X (2007) Isolation and identification of phase 1 metabolites of demethoxycurcumin in rats. Drug Metab. Dispos 35, 1564–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hoehle SI, Pfeiffer E, Lyom AMS, and Metzler M (2006) Metabolism of curcuminoids in tissue slices and subcellular fractions from rat liver. J. Agric. Food Chem 54, 756–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang K, and Qiu F (2013) Curcuminoid metabolism and its contribution to the pharmacological effects. Curr. Drug Metab 14, 791–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Xiao Y, Chen X, Yang L, Zhu X, Zou L, et al. (2013) Preparation and oral bioavailability study of curcuminoid-loaded microemulsion. J. Agric. Food Chem 61, 3654–3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Asher GN, Xie Y, Moaddel R, Sanghvi M, Dossou KS, et al. (2017) Randomized pharmacokinetic crossover study comparing 2 curcumin preparations in plasma and rectal tissue of healthy human volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol 57, 185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cuomo J, Appendino G, Dern AS, Schneider E, McKinnon TP, et al. (2011) Comparative absorption of a standardized curcuminoid mixture and its lecithin formulation. J. Nat. Prod 74, 664–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wu B, Basu S, Meng S, Wang X, and Hu M (2011) Regioselective sulfation and glucuronidation of phenolics: insights into the structural basis. Curr. Drug Metab 12, 900–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lu D, Liu H, Ye W, Wang Y, and Wu B (2017) Structure- and isoform-specific glucuronidation of six curcumin analogs. Xenobiotica 47, 304–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang S, Li F, Quan E, Dong D, and Wu B (2016) Efflux transport characterization of resveratrol glucuronides in udp-glucuronosyltransferase 1a1 transfected hela cells: application of a cellular pharmacokinetic model to decipher the contribution of multidrug resistance-associated protein 4. Drug Metab. Dispos 44, 485–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Xu H, Kulkarni KH, Singh R, Yang Z, Wang SWJ, et al. (2009) Disposition of naringenin via glucuronidation pathway is affected by compensating efflux transporters of hydrophilic glucuronides. Mol. Pharm 6, 1703–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yang Z, Zhu W, Gao S, Yin T, Jiang W, et al. (2012) Response to letter to the editor on “breast cancer resistance protein (abcg2) determines distribution of genistein phase ii metabolites: reevaluation of the roles of abcg2 in the disposition of genistein”. Drug Metab. Dispos 40, 2219–2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Quan E, Wang H, Dong D, Zhang X, and Wu B (2015) Characterization of chrysin glucuronidation in ugt1a1-overexpressing hela cells: elucidating the transporters responsible for efflux of glucuronide. Drug Metab. Dispos 43, 433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhang X, Dong D, Wang H, Ma Z, Wang Y, et al. (2015) Stable knockdown of efflux transporters leads to reduced glucuronidation in ugt1a1-overexpressing hela cells: the evidence for glucuronidation-transport interplay. Mol. Pharm 12, 1268–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Qin Z, Li S, Yao Z, Hong X, Wu B, et al. (2018) Chemical inhibition and stable knock-down of efflux transporters leads to reduced glucuronidation of wushanicaritin in ugt1a1-overexpressing hela cells: the role of breast cancer resistance protein (bcrp) and multidrug resistance-associated proteins (mrps) in the excretion of glucuronides. Food Funct. 9, 1410–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ahlin G, Hilgendorf C, Karlsson J, Szigyarto CA, Uhlen M, et al. (2009) Endogenous gene and protein expression of drug-transporting proteins in cell lines routinely used in drug discovery programs. Drug Metab. Dispos 37, 2275–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hong X, Zheng Y, Qin Z, Wu B, Dai Y, et al. (2017) In vitro glucuronidation of wushanicaritin by liver microsomes, intestine microsomes and expressed human udp-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes. Int. J. Mol. Sci 18, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hutzler JM, and Tracy TS (2002) Atypical kinetic profiles in drug metabolism reactions. Drug Metab. Dispos 30, 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Xin H, Xia Y-L, Hou J, Wang P, He, et al. (2015) Identification and characterization of human udp-glucuronosyltransferases responsible for the invitro glucuronidation of arctigenin. J. Pharm. Pharmacol 67, 1673–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lv X, Hou J, Xia Y-L, Ning J, He G-Y, et al. (2015) Glucuronidation of bavachinin by human tissues and expressed ugt enzymes: identification of ugt1a1 and ugt1a8 as the major contributing enzymes. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet 30, 358–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhang Y, Gupta A, Wang H, Zhou L, Vethanayagam RR, et al. (2005) Bcrp transports dipyridamole and is inhibited by calcium channel blockers. Pharm. Res 22, 2023–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Loe DW, Almquist KC, Deeley RG, and Cole SP (1996) Multidrug resistance protein (mrp)-mediated transport of leukotriene c4 and chemotherapeutic agents in membrane vesicles. Demonstration of glutathione-dependent vincristine transport. J. Biol. Chem 271, 9675–9682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Allen JD, van Loevezijn A, Lakhai JM, van der Valk M, van Tellingen O, et al. (2002) Potent and specific inhibition of the breast cancer resistance protein multidrug transporter in vitro and in mouse intestine by a novel analogue of fumitremorgin C. Mol. Cancer Ther 1, 417–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Matsson P, Pedersen JM, Norinder U, Bergstrom CA, and Artursson P (2009) Identification of novel specific and general inhibitors of the three major human atp-binding cassette transporters p-gp, bcrp and mrp2 among registered drugs. Pharm. Res 26, 1816–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wang M, Yang G, He Y, Xu B, Zeng M, et al. (2016) Establishment and use of new mdck ii cells overexpressing both ugt1a1 and mrp2 to characterize flavonoid metabolism via the glucuronidation pathway. Mol. Nutr. Food Res 60, 1967–1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kusuhara H, Furuie H, Inano A, Sunagawa A, Yamada S, et al. (2012) Pharmacokinetic interaction study of sulphasalazine in healthy subjects and the impact of curcumin as an in vivo inhibitor of bcrp. Br. J. Pharmacol 166, 1793–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ge S, Yin T, Xu B, Gao S, and Hu M (2015) Curcumin affects phase ii disposition of resveratrol through inhibiting efflux transporters mrp2 and bcrp. Pharm. Res 33, 590–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Karibe T, Imaoka T, Abe K, and Ando O (2018) Curcumin as an in vivo selective intestinal breast cancer resistance protein inhibitor in cynomolgus monkeys. Drug Metab. Dispos 46, 667–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ebert B, Seidel A, and Lampen A (2007) Phytochemicals induce breast cancer resistance protein in caco-2 cells and enhance the transport of benzo [a]pyrene-3-sulfate. Toxicol. Sci 96, 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Fatouros D, Das M, and Sahoo SK (2012) Folate decorated dual drug loaded nanoparticle: role of curcumin in enhancing therapeutic potential of nutlin-3a by reversing multidrug resistance. PLoS One 7, e32920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Rao DK, Liu H, Ambudkar SV, and Mayer M (2014) A combination of curcumin with either gramicidin or ouabain selectively kills cells that express the multidrug resistance-linked abcg2 transporter. J. Biol. Chem 289, 31397–31410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ampasavate C, Sotanaphun U, Phattanawasin P, and Piyapolrungroj N (2010) Effects of curcuma spp. on p-glycoprotein function. Phytomedicine 17, 506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wortelboer HM, Usta M, van Zanden JJ, van Bladeren PJ, Rietjens IM, et al. (2005) Inhibition of multidrug resistance proteins mrp1 and mrp2 by a series of alpha,beta-unsaturated carbonyl compounds. Biochem. Pharmacol 69, 1879–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sun H, Zhou X, Zhang X, and Wu B (2015) Decreased expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (mrp4/abcc4) leads to reduced glucuronidation of flavonoids in ugt1a1-overexpressing hela cells: the role of futile recycling. J. Agric. Food Chem 63, 6001–6008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nakatomi K, Yoshikawa M, Oka M, Ikegami Y, Hayasaka S, et al. (2001) Transport of 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (sn-38) by breast cancer resistance protein abcg2 in human lung cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 288, 827–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]