Summary

Background

Dupilumab, a human monoclonal antibody, blocks the shared receptor unit for interleukin‐4 and interleukin‐13. International phase II and III studies have evaluated the efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis (AD), but the effects of dupilumab in Japanese patients have not been reported.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of dupilumab in Japanese patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD.

Methods

We analysed the efficacy and safety of dupilumab in the Japanese cohorts of a 16‐week, phase IIb dose‐finding trial (AD‐1021; NCT01859988); a 16‐week, phase III, placebo‐controlled monotherapy trial (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1; NCT02277743) and a 52‐week, phase III, placebo‐controlled study of dupilumab with topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS; NCT02260986).

Results

Twenty‐seven, 106 and 117 Japanese patients were enrolled in AD‐1021, SOLO 1 and CHRONOS, respectively. Baseline disease severity was numerically higher in the Japanese cohort than in the overall study population. Generally, dupilumab significantly improved signs and symptoms of AD, including pruritus and patient quality of life, compared with placebo in the Japanese cohort, consistent with the overall study population. The combined safety profile of dupilumab in the Japanese cohort was similar to that in the total study populations; dupilumab was associated with an increased incidence of injection‐site reactions and conjunctivitis compared with placebo. Dupilumab was associated with rapid reduction in thymus and activation‐regulated chemokine and gradual IgE reductions.

Conclusions

Dupilumab alone or with topical corticosteroids improved signs and symptoms of AD, had an acceptable safety profile, and suppressed biomarkers of type 2 inflammation compared with placebo in Japanese adult patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD.

What's already known about this topic?

Differences in atopic dermatitis (AD) pathology have been reported between Asian and Western populations, in which distinct helper T‐cell activation profiles have been observed.

International clinical studies in adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD have evaluated the efficacy and safety of dupilumab, which blocks interleukin‐4 and interleukin‐13, key molecules in type 2 inflammation.

The effects of dupilumab in Japanese patients specifically have not yet been reported.

What does this study add?

Dupilumab alone or with topical corticosteroids improved signs and symptoms of AD and had an acceptable safety profile compared with placebo in Japanese patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD.

The effects were comparable with those observed in the overall study population.

Reported immunological differences in AD pathology in Asian patients may be secondary to type 2 immune activation.

Short abstract

Plain language summary available online

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease, characterized by rash and pruritus, that negatively affects sleep, mood, productivity and quality of life.1, 2 The pathophysiology of AD is complex and involves both the disruption of skin barrier function and inflammation related to upregulation of the type 2/T helper (Th) 2 pathway.3

In Japan, the estimated prevalence of AD in adults ranges from 2% to 10%.2, 4, 5, 6 Some important differences between Asian and Western populations with AD have been reported. For example, activation of Th17 is more common in Asian than in Western patients,7 and FLG mutations, which are associated with increased disease severity, are less common in Japanese patients than in Western patients.8, 9 Pharmacological options for patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD include topical corticosteroids (TCS) and the topical calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus.1, 2

For patients with very severe AD, the current standard of care in Japan is a short course of oral ciclosporin A or oral corticosteroids, although longer courses are not recommended due to the substantial side‐effects of these agents. Therefore, an unmet need exists for safe and effective therapies that provide long‐term control for patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD. Biomarkers may be useful in monitoring disease severity and treatment effects in patients with AD, such as thymus and activation‐regulated chemokine (TARC; CCL17) and IgE, markers of the interleukin (IL)‐4 and IL‐13 signalling pathways.10, 11, 12 In Japan, serum TARC measurement has been commercially available since 2008 and is widely used as a biomarker for monitoring AD severity and treatment effectiveness.10, 13

Dupilumab, a fully human VelocImmune®‐derived14, 15 monoclonal antibody, blocks the shared receptor unit for IL‐4 and IL‐13, thus inhibiting signalling of both cytokines. Dupilumab is approved for subcutaneous administration every 2 weeks (q2w) for the treatment of the following groups: (i) patients aged ≥ 12 years in the U.S.A. with moderate‐to‐severe AD inadequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable;16 (ii) adult patients with AD not adequately controlled with existing therapies in Japan; and (iii) adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD who are candidates for systemic therapy in the European Union.17 Dupilumab is also approved in Japan for patients aged ≥ 12 years with severe or refractory bronchial asthma whose symptoms are inadequately controlled with existing therapies, and in the U.S.A. as add‐on maintenance treatment in patients with moderate‐to‐severe asthma aged ≥ 12 years with an eosinophilic phenotype or with oral corticosteroid‐dependent asthma, regardless of eosinophilic phenotype. The efficacy and safety of dupilumab have also been shown in clinical trials in other type 2 immune diseases, including chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, and eosinophilic oesophagitis, thereby demonstrating the importance of IL‐4 and IL‐13 as drivers of multiple type 2 atopic and allergic diseases.18, 19

In an international, randomized, phase II trial (AD‐1021), dupilumab treatment for 16 weeks was shown to improve clinical responses in adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD in a dose‐dependent manner, with no major safety concerns.20 Subsequently, a pivotal, international, phase III monotherapy trial (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1) demonstrated the efficacy and safety of dupilumab when it was administered for 16 weeks to patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD. In that trial, dupilumab improved the signs and symptoms of AD, including pruritus, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and patient quality of life.21 Lastly, an international, 52‐week study of dupilumab given in combination with TCS (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS) established the long‐term safety and efficacy of dupilumab in patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD.22 However, given the distinct characteristics of Asian patients with AD, the question remains as to whether IL‐4 receptor subunit blockade is similarly efficacious in Japanese patients with AD. Therefore, we analysed the efficacy and safety of dupilumab in a Japanese population with moderate‐to‐severe AD who participated in the three previously mentioned trials (AD‐1021, SOLO 1 and CHRONOS).

Patients and methods

Study design and patients

Previous reports have described the trial designs and overall results from AD‐1021 (NCT01859988),20 SOLO 1 (NCT02277743)21 and CHRONOS (NCT02260986).22 The designs of each trial are summarized in Figures S1–S3 (see Supporting Information).

Briefly, AD‐1021 was a randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, dose‐ranging, phase IIb trial in which 452 adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD were randomized to receive varying doses and schedules of dupilumab or placebo for 16 weeks.20 The primary efficacy end point was change in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) from baseline to week 16. Only two dose groups [300 mg weekly (qw) and 300 mg q2w] of dupilumab monotherapy were included in the current analysis to maintain consistency with the dose groups in the other studies and because the patient numbers per treatment group in the Japanese cohort were small.

SOLO 1 was a randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, phase III trial in which 671 adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD were randomized to receive dupilumab monotherapy (300 mg qw or q2w) or placebo for 16 weeks.21 The primary end point was the proportion of patients who achieved a score of 0 or 1 on the Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) and had a ≥ 2‐point reduction in IGA score from baseline. In Europe and Japan, the proportion of patients achieving ≥ 75% improvement in EASI score (EASI 75) from baseline to week 16 was considered a coprimary end point.

CHRONOS was a randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, phase III trial in which 740 adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD were randomized to receive dupilumab (300 mg qw or q2w) and concomitant TCS or placebo + TCS for 52 weeks.22 The coprimary end points were the proportion of patients with IGA 0 or 1 (and a ≥ 2‐point reduction from baseline) and the proportion of patients achieving EASI 75 at week 16.

AD‐1021 and SOLO 1 assessed the effects of dupilumab monotherapy compared with placebo, although patients were allowed to receive TCS (or topical calcineurin inhibitors if TCS were inadvisable) as rescue therapy. CHRONOS patients receiving concomitant TCS were allowed to taper TCS if appropriate.

In all three studies, patients were stratified by disease severity (moderate or severe, as assessed by IGA) and region. Predefined analyses included patient baseline characteristics (Table 1) and the individual analyses of adverse events (AEs) reported in the Japanese cohorts of each study (Tables S1–3; see Supporting Information). All other analyses were conducted post hoc.

Table 1.

Patients’ baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | AD‐1021 | SOLO 1 | CHRONOS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo qw (n = 8) | Dupilumab 300 mg q2w (n = 10) | Dupilumab 300 mg qw (n = 9) | Placebo qw (n = 35) | Dupilumab 300 mg q2w (n = 36) | Dupilumab 300 mg qw (n = 35) | Placebo qw + TCS (n = 54) | Dupilumab 300 mg q2w + TCS (n = 16) | Dupilumab 300 mg qw + TCS (n = 47) | |

| Age (years) | 34 (26–59) | 38 (30–57) | 37 (21–43) | 42 (18–58) | 41 (20–59) | 37 (18–56) | 35 (19–67) | 38 (20–67) | 32 (19–56) |

| Male, n (%) | 6 (75) | 8 (80) | 7 (78) | 26 (74) | 27 (75) | 24 (69) | 36 (67) | 9 (56) | 32 (68) |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 21·4 (17·7–26·4) | 25·0 (20·7–30·5) | 22·4 (18·9–31·2) | 22·8 (17·0–44·0) | 22·8 (17·0–49·0) | 22·8 (17·0–36·0) | 22·4 (17·0–30·0) | 21·8 (19·0–33·0) | 23·2 (17·0–33·0) |

| AD duration (years) | 27 (18–40) | 32 (3–41) | 34 (18–39) | 33 (8–57) | 27 (15–58) | 31 (6–51) | 30 (4–47) | 30 (14–48) | 26 (8–53) |

| BSA affected (%) | 57 (35–88) | 76 (27–99) | 59 (21–88) | 74 (37–100) | 70 (34–100) | 71 (36–95) | 68 (33–100) | 62 (40–100) | 63 (28–97) |

| EASI score (0–72) | 33 (20–67) | 41 (19–56) | 33 (17–54) | 40 (17–72) | 37 (17–70) | 36 (17–64) | 36 (17–70) | 33 (19–61) | 37 (17–70) |

| Peak weekly averaged pruritus NRS (0–10) | 6 (4–9) | 6 (3–10) | 6 (4–9) | 8 (4–9) | 7 (0–10) | 7 (1–10) | 8 (3–10) | 7 (4–9) | 7 (2–10) |

| Total SCORAD (0–103) | 61 (36–97) | 74 (42–95) | 65 (48–77) | 72 (38–101) | 69 (43–99) | 68 (43–92) | 64 (46–101) | 73 (47–90) | 67 (41–95) |

| IGA 4 (severe), n (%) | 4 (50) | 4 (40) | 4 (44) | 24 (69) | 24 (67) | 23 (66) | 31 (57) | 8 (50) | 26 (55) |

| POEM score (0–28) | 21 (10–26) | 19 (6–28) | 17 (10–28) | 19 (4–28) | 20 (1–28) | 22 (2–28) | 20 (8–28) | 20 (4–25) | 19 (6–28) |

| DLQI score (0–30) | 12 (9–19) | 12 (1–26) | 6 (5–23) | 11 (2–27) | 11 (0–27) | 11 (1–26) | 11 (1–30) | 10 (3–24) | 10 (2–27) |

Values are the median (range) unless otherwise specified. AD, atopic dermatitis; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA, Investigator's Global Assessment; NRS, numerical rating scale; POEM, Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure; qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks; SCORAD, Scoring Atopic Dermatitis; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

The three studies presented in the present article were each conducted in adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki of 2013 and in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocols were approved by their respective institutional review boards, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Outcomes assessed

The baseline characteristics of the Japanese cohort of each trial were tabulated. The following efficacy outcomes were assessed in the Japanese cohort from each trial, according to treatment group (placebo, dupilumab 300 mg qw or dupilumab 300 mg q2w): the proportion of patients with IGA 0 or 1 and ≥ 2‐point reduction from baseline, the proportion of patients achieving EASI 75, the percentage change from baseline in EASI score, the percentage change in weekly averaged Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) score, the proportions of patients with ≥ 3‐point or ≥ 4‐point reduction (improvement) in weekly averaged Peak Pruritus NRS, the proportion of patients with ≥ 4‐point reduction (improvement) in Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) and the proportion of patients with ≥ 4‐point reduction (improvement) in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score. For POEM and DLQI, only those patients with baseline scores ≥ 4 were included in the analysis.

The incidence of treatment‐emergent AEs (TEAEs) was calculated for the Japanese cohort of each study, according to treatment group. Changes from baseline in serum concentrations of the biomarkers TARC and IgE were assessed only in SOLO 1 (weeks 0–16) and CHRONOS (weeks 0–52).

Analysis

For AD‐1021, safety data for weeks 0–16 and the follow‐up period were included based on the safety analysis set. For SOLO 1, efficacy data (weeks 0–16) were based on the final analysis set, and safety data (weeks 0–16 and follow‐up period) were based on the safety analysis set. A second identical phase III trial (SOLO 2) was conducted,21 but it did not include Japanese patients and was therefore not included in the analysis. For CHRONOS, efficacy data were based on the primary analysis dataset for week 16 and the full analysis dataset for weeks 0–52, whereas the safety data (weeks 0–52 and follow‐up period) were based on the safety analysis set. For the safety analysis, the Japanese cohorts from the three studies were combined (n = 250) and compared with the total study populations combined (n = 1597) in terms of incidence of TEAEs.

All statistical tests for the results reported in this manuscript were exploratory. Binary end points were analysed using a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by region and baseline disease severity (IGA = 3 vs. IGA = 4). Patients with missing values at week 16 or week 52 or who used rescue medication were considered nonresponders. Continuous outcomes were analysed using an ancova model, with the baseline measurement as covariate and the treatment, region and baseline IGA strata as fixed factors. Values after the first rescue treatment were set to missing (censored), and missing data, regardless of the reason, were imputed using the multiple imputation method. Descriptive statistics were used to assess the demographic and clinical characteristics.

Results

Patients

The Japanese cohort consisted of 27 patients in AD‐1021, 106 patients in SOLO 1 and 117 patients in CHRONOS. All patients were enrolled at study sites in Japan. The baseline demographics and clinical characteristics among the Japanese cohort are shown in Table 1 and Table S4 (see Supporting Information). These characteristics were generally similar across studies and treatment groups: median ages ranged from 32 to 42 years, the median proportion of body surface area (BSA) affected by AD was 57–76%, and approximately one‐half of patients had an IGA score of 4 (severe disease). The baseline demographics (age, male‐to‐female ratio and duration of AD) of the Japanese cohort were generally similar to those in the total study populations for each study.20, 21, 22 However, compared with the total study populations, the corresponding Japanese cohorts at baseline had a higher proportion with IGA = 4 in SOLO 121 and CHRONOS22 and a similar proportion in AD‐1021.20 The Japanese cohorts at baseline also had a higher median EASI score and a higher median proportion of BSA affected by AD compared with the total study populations.20, 21, 22 Other parameters, including Peak Pruritus NRS, were generally similar in the Japanese cohort and overall study populations.

Efficacy: SOLO 1

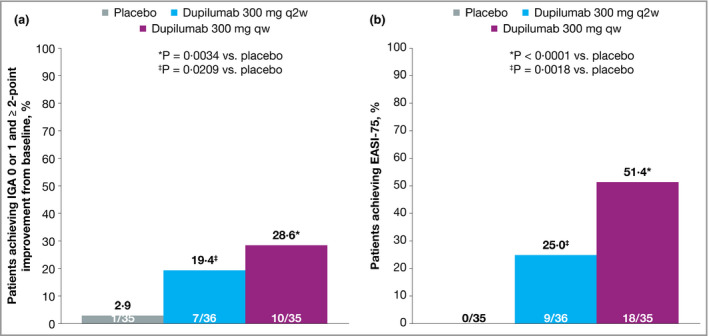

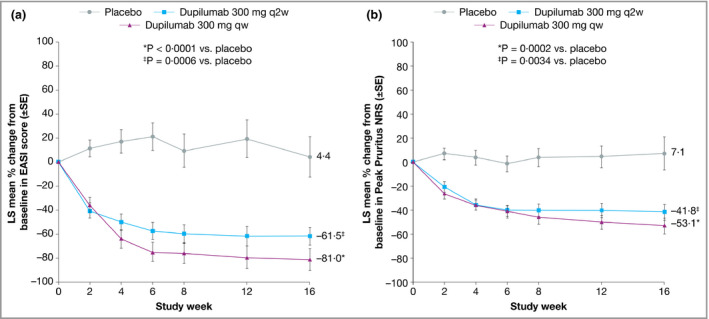

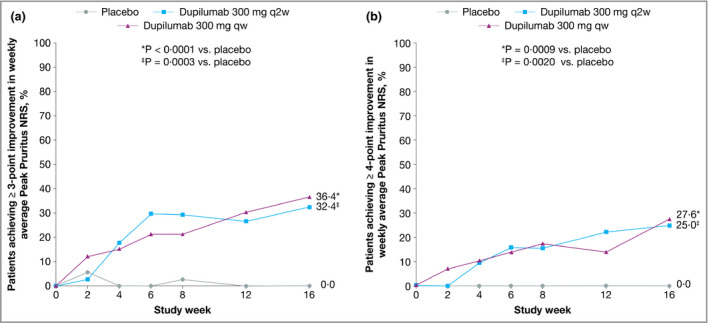

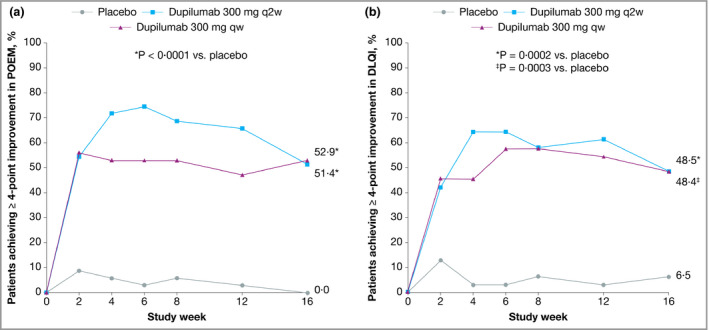

In the Japanese cohort of SOLO 1, treatment with dupilumab 300 mg qw (n = 35) or q2w (n = 36) was associated with significant improvements in all efficacy measures at week 16 compared with placebo (n = 35). This included the proportion of patients achieving IGA 0 or 1 and ≥ 2‐point improvement from baseline (Fig. 1a), the proportion achieving EASI 75 (Fig. 1b), the percentage change from baseline in EASI score (Fig. 2a) and the weekly average Peak Pruritus NRS (Fig. 2b). Dupilumab was also associated with a significantly higher proportion of patients achieving improvements of ≥ 3 points or ≥ 4 points in weekly average Peak Pruritus NRS (Fig. 3) and improvement of ≥ 4 points in either POEM (Fig. 4a) or DLQI (Fig. 4b). The magnitude of effect observed with dupilumab in Japanese patients was generally similar to that observed in the total SOLO 1 population.21

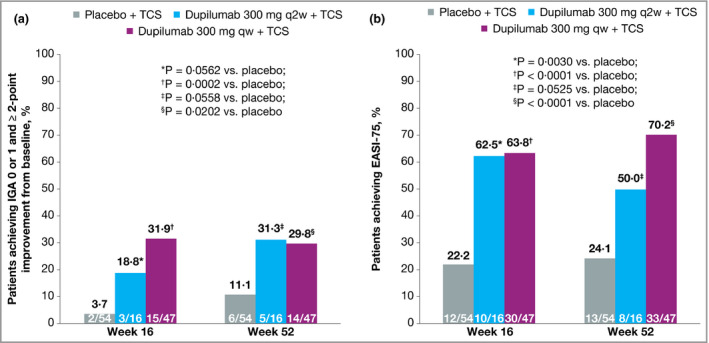

Figure 1.

Efficacy outcomes in the Japanese cohort from SOLO 1, including (a) the proportion of patients achieving Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) 0 or 1 at week 16 with ≥ 2‐point improvement from baseline, (b) the proportion of patients achieving ≥ 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 75) at week 16. Values in white font denote patient numbers (n/N). Patients with missing IGA or EASI score at each visit were considered nonresponders. Values after the first rescue treatment used were set to missing (censoring). qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks.

Figure 2.

Efficacy outcomes in the Japanese cohort from SOLO 1, including (a) the percentage change from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 75) over time and (b) the percentage change from baseline in the weekly average of Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) over time. Values after the first rescue treatment used were set to missing (censoring). LS, least squares; qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks.

Figure 3.

Efficacy outcomes in the Japanese cohort from SOLO 1, including the proportions of patients with (a) ≥ 3‐point or (b) ≥ 4‐point improvement in weekly average Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) over time. Values after the first rescue treatment used were set to missing (censoring). qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks.

Figure 4.

Efficacy outcomes in the Japanese cohort from SOLO 1, including the proportions of patients with ≥ 4‐point improvement in (a) Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) and (b) Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) over time. Values after the first rescue treatment used were set to missing (censoring). POEM and DLQI analyses were performed in the subgroup of patients with respective baseline scores ≥ 4. LS, least squares; qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks.

Efficacy: CHRONOS

In the Japanese cohort of CHRONOS, dupilumab 300 mg qw + TCS (n = 47) was associated with a significantly higher proportion of patients achieving IGA 0 or 1 and improvement of ≥ 2 points from baseline at weeks 16 and 52 compared with placebo + TCS (n = 54, Fig. 5a). In patients receiving dupilumab 300 mg q2w + TCS (n = 16), an arm that was by design one‐third the size of the placebo and q2w arms, the difference compared with placebo did not reach statistical significance at week 16 or week 52. The proportion of patients achieving EASI 75 at week 16 was significantly higher in both dupilumab dosing groups compared with placebo (Fig. 5b). At week 52, the difference between the q2w dosing group and the placebo group was not statistically significant. At week 52, the change from baseline in EASI score was significantly greater in both dupilumab groups compared with placebo (Fig. 6a).

Figure 5.

Efficacy outcomes in the Japanese cohort from CHRONOS, including (a) the proportion of patients achieving Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) 0 or 1 at weeks 16 and 52 and with ≥ 2‐point improvement from baseline and (b) the proportions of patients achieving ≥ 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 75) at weeks 16 and 52. Values in white font denote patient numbers (n/N). Values after the first rescue treatment used were set to missing (censoring). Patients with missing IGA or EASI scores at each visit were considered nonresponders. Statistical analyses at week 16 were based on the primary analysis dataset. qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

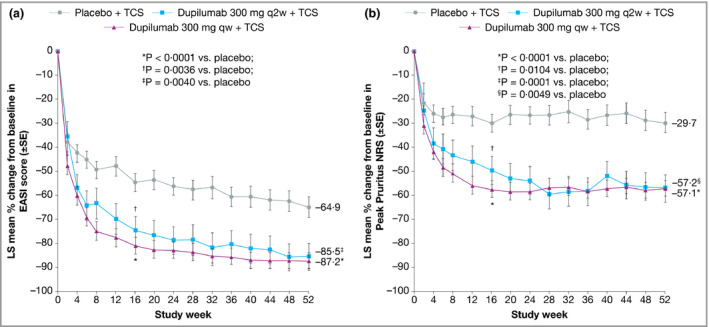

Figure 6.

Efficacy outcomes in the Japanese cohort from CHRONOS, including (a) the percentage change from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) over time and (b) the percentage change from baseline in the weekly average Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) over time. Values after the first rescue treatment used were set to missing (censoring). Statistical analyses at week 16 were based on the full analysis dataset. LS, least squares; qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

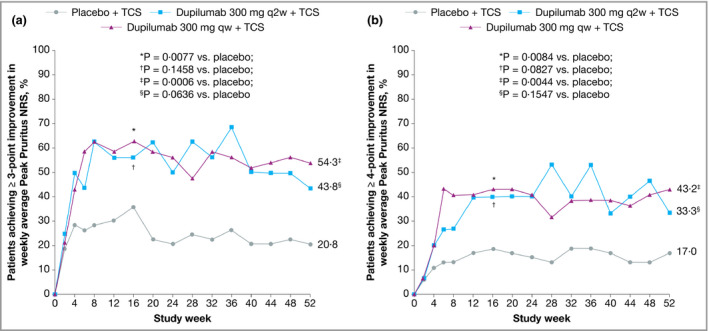

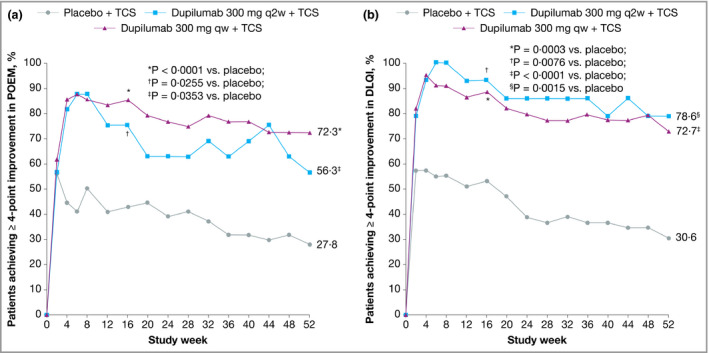

Improvement in Peak Pruritus NRS from baseline was numerically higher in both dupilumab groups compared with placebo at week 52 (Fig. 6b), as was the proportion of patients with improvement of ≥ 3 points (Fig. 7a) or ≥ 4 points (Fig. 7b) in weekly Peak Pruritus NRS score at weeks 16 and 52. The difference compared with placebo was significant in the weekly dosing group only. The proportions of patients with improvement of ≥ 4 points in POEM and DLQI were significantly higher in both dupilumab groups at weeks 16 and 52 compared with placebo (Fig. 8). Overall, the magnitude of effect in the Japanese cohort of CHRONOS was similar to that observed in the total study population.22 Lack of statistical significance in the q2w dosing group compared with placebo likely reflects the small number of Japanese patients in this cohort (n = 16).

Figure 7.

Efficacy outcomes in the Japanese cohort from CHRONOS, including the proportions of patients with (a) ≥ 3‐point or (b) ≥ 4‐point improvement in weekly average Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) over time. Values after the first rescue treatment used were set to missing (censoring). Statistical analyses at week 16 were based on the full analysis dataset. qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

Figure 8.

Efficacy outcomes in the Japanese cohort from CHRONOS, including the proportions of patients with ≥ 4‐point improvement in (a) Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) and (b) Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) over time. Values after the first rescue treatment used were set to missing (censoring). POEM and DLQI analyses were performed in the subgroup of patients with respective baseline scores ≥ 4. Statistical analyses at week 16 were based on the full analysis dataset. qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks.

Safety

To summarize the safety information from the relatively small numbers of Japanese patients in each subgroup, we combined data from the three studies irrespectively of TCS use. The incidences of TEAEs in the combined Japanese population are shown in Table 2 and Table S5 (see Supporting Information), and event rates per 100 patient‐years are provided in Table S6 (see Supporting Information). Overall, TEAEs occurred at similar rates in the Japanese cohort compared with the total study population. The incidences of most TEAEs were also similar across treatment groups, with the exception of AD exacerbation and skin infections (folliculitis and cellulitis), which occurred more frequently in the placebo groups, and conjunctivitis and injection‐site reactions, which were more frequent in the dupilumab‐treated groups in all studies. In most cases, these events were of mild‐to‐moderate severity and rarely led to treatment discontinuation. The severity of all conjunctivitis events occurring in any treatment group in the Japanese subgroup and in all patients is reported in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Most conjunctivitis events in the Japanese subgroup were reported as mild, and no severe conjunctivitis events were reported.

Table 2.

Safety assessment

| Event, n (%)a | Japanese subgroup | All patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo ± TCS (n = 97) | Dupilumab 300 mg q2w ± TCS (n = 62) | Dupilumab 300 mg qw ± TCS (n = 91) | Placebo ± TCS (n = 598) | Dupilumab 300 mg q2w ± TCS (n = 403) | Dupilumab 300 mg qw ± TCS (n = 596) | |

| Any TEAE | 81 (84) | 50 (81) | 74 (81) | 475 (79·4) | 322 (79·9) | 482 (80·9) |

| Any TE SAE | 4 (4) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 36 (6·0) | 13 (3·2) | 15 (2·5) |

| Any TEAE leading to treatment discontinuation | 4 (4) | 1 (2) | 3 (3) | 31 (5·2) | 11 (2·7) | 14 (2·3) |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) |

qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks; TCS, topical corticosteroids; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event; TE SAE, treatment‐emergent serious adverse event. aTEAEs were coded according to MedDRA version 18·0.

Table 3.

Number (percentage) of patients with ophthalmic adverse events consistent with or suggestive of conjunctivitis, by severity in the Japanese subgroup

| Preferred term | Placebo ± TCS (n = 97) | Dupilumab 300 mg q2w ± TCS (n = 62) | Dupilumab 300 mg qw ± TCS (n = 91) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Any severity | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Any severity | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Any severity | |

| Any class | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 0 | 7 (7) | 5 (8) | 3 (5) | 0 | 8 (13) | 11 (12) | 1 (1) | 0 | 12 (13) |

| Atopic keratoconjunctivitis | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blepharitis | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Conjunctival hyperaemia | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Conjunctivitis | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 | 4 (6) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Conjunctivitis allergic | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 4 (4) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 0 | 3 (5) | 7 (8) | 0 | 0 | 7 (8) |

| Conjunctivitis bacterial | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Conjunctivitis viral | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dry eye | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Eye discharge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Eye irritation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Eye pruritus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Foreign‐body sensation in eyes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lacrimation increased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ocular hyperaemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Photophobia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

Table 4.

Number (percentage) of patients with ophthalmic adverse events consistent with or suggestive of conjunctivitis, by severity in all patients

| Preferred term | Placebo ± TCS (n = 598) | Dupilumab | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 mg q2w ± TCS (n = 403) | 300 mg qw ± TCS (n = 596) | |||||||||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Any severity | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Any severity | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Any severity | |

| Any class | 31 (5·2) | 15 (2·5) | 2 (0·3) | 47 (7·9) | 40 (9·9) | 29 (7·2) | 2 (0·5) | 64 (15·9) | 88 (14·8) | 58 (9·7) | 6 (1·0) | 130 (21·8) |

| Atopic keratoconjunctivitis | 0 | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0·3) | 2 (0·3) | 0 | 4 (0·7) |

| Blepharitis | 2 (0·3) | 2 (0·3) | 0 | 4 (0·7) | 5 (1·2) | 2 (0·5) | 0 | 7 (1·7) | 10 (1·7) | 8 (1·3) | 1 (0·2) | 15 (2·5) |

| Conjunctival hyperaemia | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) |

| Conjunctivitis | 4 (0·7) | 4 (0·7) | 0 | 8 (1·3) | 8 (2·0) | 7 (1·7) | 1 (0·2) | 14 (3·5) | 13 (2·2) | 10 (1·7) | 0 | 22 (3·7) |

| Conjunctivitis allergic | 16 (2·7) | 5 (0·8) | 1 (0·2) | 22 (3·7) | 15 (3·7) | 13 (3·2) | 1 (0·2) | 26 (6·5) | 37 (6·2) | 25 (4·2) | 3 (0·5) | 59 (9·9) |

| Conjunctivitis bacterial | 2 (0·3) | 4 (0·7) | 0 | 6 (1·0) | 1 (0·2) | 4 (1·0) | 0 | 5 (1·2) | 5 (0·8) | 12 (2·0) | 1 (0·2) | 14 (2·3) |

| Conjunctivitis viral | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0·5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0·5) | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) |

| Dry eye | 4 (0·7) | 0 | 0 | 4 (0·7) | 2 (0·5) | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 3 (0·7) | 6 (1·0) | 4 (0·7) | 0 | 10 (1·7) |

| Eye discharge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 1 (0·2) |

| Eye irritation | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 1 (0·2) | 2 (0·3) | 4 (1·0) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1·0) | 5 (0·8) | 1 (0·2) | 1 (0·2) | 7 (1·2) |

| Eye pruritus | 5 (0·8) | 0 | 0 | 5 (0·8) | 3 (0·7) | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 4 (1·0) | 12 (2·0) | 3 (0·5) | 0 | 14 (2·3) |

| Foreign‐body sensation in eyes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lacrimation increased | 2 (0·3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0·3) | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) | 4 (0·7) | 2 (0·3) | 0 | 5 (0·8) |

| Ocular hyperaemia | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) | 2 (0·5) | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 3 (0·7) | 2 (0·3) | 2 (0·3) | 0 | 4 (0·7) |

| Photophobia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) | 1 (0·2) | 0 | 2 (0·5) | 2 (0·3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0·3) |

AD‐1021 and SOLO 1 data include those collected during the 16‐week treatment duration and follow‐up period; CHRONOS data include those collected during the 52‐week treatment duration and follow‐up period. If a patient developed multiple conjunctivitis events of one type of severity, the event count for that severity is one. If a patient developed multiple conjunctivitis events of different types of severity, the event count for each severity is one. qw, weekly; q2w, every 2 weeks; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

The incidences of TEAEs for the Japanese cohort of each individual study are provided in Tables S1–S3 (see Supporting Information). Of note, in AD‐1021, TEAEs of AD led to treatment discontinuation in one patient each in the placebo, 300 mg qw and 300 mg q2w groups; no serious TEAEs or deaths were reported. In SOLO 1, serious TEAEs were reported in two patients receiving placebo (urinary tract infection in one patient and AD exacerbation in one patient) and one patient in the dupilumab q2w group (AD exacerbation); no study discontinuations or deaths were reported. In CHRONOS, serious TEAEs were reported in two patients receiving placebo (pseudarthrosis in one patient, cataract and glaucoma in one patient) and one patient in the dupilumab qw group (osteoarthritis). TEAEs led to treatment discontinuation in three patients in the placebo group (molluscum, condyloma, anxiety) and two patients in the dupilumab qw group (injection‐site reaction); no deaths were reported. No patient discontinued treatment due to conjunctivitis.

Biomarker analysis (Japanese cohort)

In SOLO 1, the least squares mean percentage changes from baseline to week 16 in serum TARC concentration were +90·0% in the placebo group and −74·3% and −97·5% in the dupilumab q2w and qw groups, respectively (both P < 0·001 vs. placebo; Fig. S4a; see Supporting Information). The least squares mean percentage changes in IgE in the dupilumab q2w and qw groups (−38·4% and −60·7%, respectively) were not significantly different from the change in the placebo group (+120·1%; Fig. S4b; see Supporting Information).

In CHRONOS, a rapid reduction in serum TARC concentration was seen in both dupilumab groups; the difference compared with placebo was significant at week 52 for the qw dosing group. The q2w dosing group exhibited a similar trend, but it did not reach statistical significance, likely due to relatively small patient numbers (Fig. S5a; see Supporting Information). The reduction in IgE level was more gradual; it was significantly greater in both dupilumab groups compared with placebo at week 16, but it did not reach statistical significance at week 52 in either dosing group (Fig. S5b; see Supporting Information).

Discussion

In this cohort of Japanese adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD, dupilumab treatment alone or in combination with TCS improved signs and symptoms of AD, including pruritus and quality of life; it also had an acceptable safety profile. The efficacy and safety profiles of dupilumab in the Japanese cohort were comparable with those seen in the overall study populations, despite a higher baseline disease severity in the Japanese cohort. Dupilumab treatment in the Japanese cohort was associated with reductions in levels of key biomarkers of type 2 inflammation relative to placebo, particularly TARC, which was consistent with findings from the overall study population. Reductions in TARC preceded or coincided with indicators of the clinical efficacy of dupilumab, whereas its effect on IgE was delayed, suggesting that modulation of IL‐4 and IL‐13 has a direct effect on AD signs and symptoms independently of its suppression of IgE generation by B cells. Taken together, the evidence supports use of dupilumab in Japanese adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD, a population that has had few effective treatment options.

In Japan, the standard of care for patients with very severe AD includes oral corticosteroids and ciclosporin A. However, long‐term use of oral corticosteroids is not recommended, and use of ciclosporin A is generally limited to 12 weeks, sometimes making it difficult for clinicians to maintain long‐term disease control.2 Data from this analysis indicate that dupilumab induces rapid improvements in AD that can be maintained long term in a significant proportion of Japanese adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD, with prolonged benefits in terms of both pruritus and quality of life.

Recent literature has reported that the pathology of AD in Asian populations differs from that in Europeans and Americans in that Asians exhibit a blended phenotype of European Americans with AD and those with psoriasis, including enhanced Th17 immunity.7 This raised the question as to whether blocking the IL‐4/IL‐13 pathway could demonstrate efficacy in an Asian population. The data presented here indicate that IL‐4 and IL‐13 are key molecules, even in Japanese patients, one of the representative Asian populations in dupilumab trials and genetically distinct from most of the remaining included populations. This suggests that the observed Th17‐skewed pathology may be secondary to the Th2‐skewed one. The level of involvement of Th17 pathology in the Japanese patients studied here is unknown, and further investigation of biological samples would be needed to provide support for this concept. Of note, dupilumab was demonstrated to suppress Th17‐related gene expression in addition to Th2‐related gene expression in the skin of patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD.23, 24

The main limitations of this study were that most analyses were conducted post hoc and all analyses were of a subpopulation of three prospective trials. In addition, the number of patients in some treatment groups, particularly the q2w group in CHRONOS, was small, and differences between treatment groups should be interpreted with some caution. The q2w arm in the CHRONOS study was one‐third the size of the placebo and qw arms by design (patients were randomized 3 : 1 : 3), and lack of statistical significance may be due to the small sample size.

Overall, these findings suggest that dupilumab treatment (300 mg qw or q2w), given alone or in combination with TCS, can improve the signs and symptoms of AD, including AD skin lesions, pruritus and quality of life, in Japanese adults with moderate‐to‐severe AD, and it has an acceptable safety profile.

Supporting information

Fig S1. AD‐1021 study design.

Fig S2. SOLO 1 study design.

Fig S3. CHRONOS study design.

Fig S4. Biomarker data in the Japanese cohort from SOLO 1.

Fig S5. Biomarker data in the Japanese cohort from CHRONOS.

Table S1 Summary of adverse events reported in the Japanese cohort from AD‐1021.

Table S2 Summary of adverse events reported in the Japanese cohort from SOLO 1.

Table S3 Summary of adverse events reported in the Japanese cohort from CHRONOS.

Table S4 Baseline thymus and activation‐regulated chemokine and total IgE.

Table S5 Treatment‐emergent adverse effects by preferred term occurring in ≥ 3% of patients in any treatment group.

Table S6 Safety assessment by event rates per 100 patient‐years.

Powerpoint S1 Journal Club Slide Set.

Video S1 Author video.

Video S2 Author video (Japanese subtitles).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Thomas Hultsch for his contributions.

Conflicts of interest. N.K. has received honoraria for lectures from Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Sanofi and Taiho Pharma; and research grants from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma. Y.K. has received research grants and lecture honoraria from Sanofi. H.S. has received honoraria for lectures from Kyorin Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Sanofi and Taiho Pharmaceutical; and research grants from Eisai, Tokiwa Pharmaceutical and Torii Pharmaceutical. M.H. has received honoraria for lectures from Kaken Pharmaceutical, Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Maruho, MDS, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Sanofi K.K., Torii Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharma, Teikoku Seiyaku and Uriach. K.K. has received honoraria for lectures from Eli Lilly, Japan Tobacco Inc., LEO Pharma, Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma and P&G; and research grants from Kyoto Hakko Kirin, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma and Ono Pharma. T.E. has received honoraria for lectures from Kyowa Hakko Kirin and Maruho. A.I. has received research grants from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Sanofi, Torii Pharmaceutical and Japan Tobacco Inc.; consultancy fees from Japan Tobacco Inc. and Maruho; and honoraria for lectures from Maruho and Sanofi. S.I. has received honoraria for lectures from Maruho and Kyowa Hakko Kirin. M.K. has received lecture and/or consultancy fees from GlaxoSmithKline K.K., Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Nippon Zoki Pharmaceutical, Pola Pharma, Rohto Pharmaceutical and Sato Pharmaceutical Co. M.O. has received research grants from AbbVie, Eisai, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Sanofi, Taiho Pharmaceutical and Torii Pharmaceutical; and lecture and/or consultancy fees from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Taiho Pharmaceutical and Torii Pharmaceutical. H.F., K.A. and H.T. are employees and shareholders of Sanofi K.K.. Z.C., B.S. and M.A. are employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Funding sources This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Medical writing assistance and editorial support were provided by Carolyn Ellenberger, PhD of Excerpta Medica, funded by Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Conflicts of interest Statements can be found in the Appendix.

Plain language summary available online

References

- 1. Saeki H, Nakahara T, Tanaka A et al Clinical practice guidelines for the management of atopic dermatitis 2016. J Dermatol 2016; 43:1117–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Katayama I, Kohno Y, Akiyama K et al Japanese guideline for atopic dermatitis 2014. Allergol Int 2014; 63:377–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brunner PM, Guttman‐Yassky E, Leung DY. The immunology of atopic dermatitis and its reversibility with broad‐spectrum and targeted therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139 (4 Suppl.):S65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Muto T, Hsieh SD, Sakurai Y et al Prevalence of atopic dermatitis in Japanese adults. Br J Dermatol 2003; 148:117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saeki H, Oiso N, Honma M et al Prevalence of atopic dermatitis in Japanese adults and community validation of the U.K. diagnostic criteria. J Dermatol Sci 2009; 55:140–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A et al Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy 2018; 73:1284–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Noda S, Suárez‐Fariñas M, Ungar B et al The Asian atopic dermatitis phenotype combines features of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with increased TH17 polarization. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 136:1254–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nomura T, Akiyama M, Sandilands A et al Prevalent and rare mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin in Japanese patients with ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129:1302–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Osawa R, Konno S, Akiyama M et al Japanese‐specific filaggrin gene mutations in Japanese patients suffering from atopic eczema and asthma. J Invest Dermatol 2010; 130:2834–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kataoka Y. Thymus and activation‐regulated chemokine as a clinical biomarker in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol 2014; 41:221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liddiard K, Welch JS, Lozach J et al Interleukin‐4 induction of the CC chemokine TARC (CCL17) in murine macrophages is mediated by multiple STAT6 sites in the TARC gene promoter. BMC Mol Biol 2006; 7:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu LC, Zarrin AA. The production and regulation of IgE by the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14:247–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kakinuma T, Nakamura K, Wakugawa M et al Thymus and activation‐regulated chemokine in atopic dermatitis: serum thymus and activation‐regulated chemokine level is closely related with disease activity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 107:535–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Macdonald LE, Karow M, Stevens S et al Precise and in situ genetic humanization of 6 Mb of mouse immunoglobulin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:5147–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murphy AJ, Macdonald LE, Stevens S et al Mice with megabase humanization of their immunoglobulin genes generate antibodies as efficiently as normal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:5153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dupilumab [package insert]. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761055s012lbl.pdf (last accessed 22 October 2019).

- 17. European Medicines Agency . Annex I. Summary of product characteristics [dupilumab]. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/dupixent-epar-product-information_en.pdf (last accessed 22 October 2019).

- 18. Bachert C, Mannent L, Naclerio RM et al Effect of subcutaneous dupilumab on nasal polyp burden in patients with chronic sinusitis and nasal polyposis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 315:469–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirano I, Dellon ES, Hamilton JD et al Dupilumab efficacy and safety in adult patients with active eosinophilic oesophagitis: a randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled phase II trial. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2017; 1138–50. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thaçi D, Simpson EL, Beck LA et al Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: a randomised, placebo‐controlled, dose‐ranging phase IIb trial. Lancet 2016; 387:40–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman‐Yassky E et al Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2335–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blauvelt A, de Bruin‐Weller M, Gooderham M et al Long‐term management of moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1‐year, randomised, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 389:2287–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hamilton JD, Suárez‐Fariñas M, Dhingra N et al Dupilumab improves the molecular signature in skin of patients with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134:1293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guttman‐Yassky E, Bissonnette R, Ungar B et al Dupilumab progressively improves systemic and cutaneous abnormalities in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 143:155–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1. AD‐1021 study design.

Fig S2. SOLO 1 study design.

Fig S3. CHRONOS study design.

Fig S4. Biomarker data in the Japanese cohort from SOLO 1.

Fig S5. Biomarker data in the Japanese cohort from CHRONOS.

Table S1 Summary of adverse events reported in the Japanese cohort from AD‐1021.

Table S2 Summary of adverse events reported in the Japanese cohort from SOLO 1.

Table S3 Summary of adverse events reported in the Japanese cohort from CHRONOS.

Table S4 Baseline thymus and activation‐regulated chemokine and total IgE.

Table S5 Treatment‐emergent adverse effects by preferred term occurring in ≥ 3% of patients in any treatment group.

Table S6 Safety assessment by event rates per 100 patient‐years.

Powerpoint S1 Journal Club Slide Set.

Video S1 Author video.

Video S2 Author video (Japanese subtitles).