Abstract

One of the characteristic features of obesity is increased body weight and accumulation of adipose tissue. It is associated with low grade inflammation and gut dysbiosis. Probiotics and its products could be an ideal strategy to prevent or treat diabetes. In the present study, animals were induced obesity by providing them with high fat diet. Three purified bacteriocins i.e., DT24, PJ4 and TSU4, previously isolated and purified from various probiotic strains, were given as treatment strategies, following the induction of obesity. Upon the completion of the study, animals were sacrificed and were checked for their tissue expression of inflammatory mediators and adipokines. Serum hormone and cytokines analysis were performed to check their inflammatory state. Treatment with purified bacteriocin DT24 did not show any therapeutic effect in any of the parameter studied. Bacteriocin TSU4 on the other hand showed better reversal compared to DT24. Bacteriocin PJ4 showed the most promising results by reversing all the altered parameters significantly. It significantly reversed all the biochemical, immunological in terms of serum cytokines as well as altered morphological characteristics. PJ4 can be further explored to determine its mode of action. The anti-microbial proteins or to be more specific, bacteriocins, which shows broad spectrum efficacy, could be a better alternative in modulating gut microflora for the treatment of obesity and diabetes characteristics. The efficacy of bacteriocin PJ4 may also be due to the source of the host of Lactobacillus.

Keywords: Lactobacillus, Bacteriocin, Adipose, Obesity, High fat diet

Introduction

Obesity is characterized by excess body fat (BF) and is growing into an epidemic in both developed and developing countries [WHO (World Health Organization) 2017; Engin 2017]. It has become a major issue which has affected one-third of the world population (Alexandraki et al. 2013; Ng et al. 2014). One of the most common causes of obesity incidences includes high caloric food intake and sedentary lifestyle, leading to increased body fat (Stein and Colditz 2004). Obesity has been positively associated with other co-morbidities such as diabetes, cardiovascular, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and even colorectal cancer (Vucenik and Stains 2012). There are various reports about direct correlation of obesity and weight gain with increased incidence of diabetes (Ford et al. (1997); Resnick et al. 2000).

Adipose tissue is one of the major organs involved in the physiological function of the body as it is involved in the production of adipokines such as TNF-α, cytokines, adipsin, angiotensinogen, adiponectin, resistin and leptin, which plays a crucial role in meta-inflammatory state of the body (Frühbeck et al. 2001). Obesity is regarded as a low-grade inflammation, leading to enlargement in the adipose tissue and involved in increased adipokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 (Gregor and Hotamisligil 2011). There are increasing evidences of the correlation between the IL-1b production mediated by the NLRP3 and caspase-1 interaction in the development of insulin resistance and obesity (Wen et al. 2011; Stienstra et al. 2012).

Gut microbiota has been a key modulator of in host physiology and has been reported to play an important role in degradation of a variety of xenobiotic compounds (Cani et al. 2013). Dysbiosis in the gut microflora has been reported to be one of the leading causes of obesity, diabetes, NAFLD and even anxiety and depression (Leung et al. 2016; Perez-Chanona and Trinchieri 2016). The role and extensive use of probiotic strains has been reported with the intention to ameliorate obesity by manipulating its potential to improve the gut dysbiosis, strengthening the gut barrier, reduce inflammation and body fat (Ejtahed et al. 2019; Plovier et al. 2017; Torres et al. 2019). Probiotic strains possess diverse biological activities. One of the biomolecules responsible is bacteriocins, which are ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides produced by numerous Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (Nes et al. 2007). In our previous studies, we have purified bacteriocin TSU4 (Sahoo et al. 2015), bacteriocin DT24 (Trivedi et al. 2013), bacteriocin PJ4 (Jena et al. 2013) from probiotic lactobacillus strains isolation from biological samples. Most of the research pertaining to the use of bacteriocins have been concentrated towards their anti-microbial activities. However, there are no reports about its role on the gut microbiota and their ability to treat the obese characteristics. In the present investigation, we explored the meta-inflammatory characteristics and gut microfloral modulation following high fat feeding in animals and their response to oral administration of purified bacteriocins individually.

Materials and methods

Test animals and sample collection

Male C57BL/6 J mice of 10–12 weeks of age, were obtained from Zydus Research Centre (ZRC), Ahmedabad and grouped in four animals per cage. Control animals were given chow pellet and water. HFD group of animals were supplemented with high fat diet (HFD) having 35% hydrogenated vegetable oil to induce obesity. Water and food was provided ab libitum to all the groups of animals. All animal related protocols were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Nirma University, Ahmedabad under the CPCSEA guidelines of Ministry of Environment and Forest, New Delhi (Protocol No: IS/PHD/18/024).

Bacteriocins purification and dosing

Bacteriocins used in the present study was purified per the protocol as mentioned in Sahoo et al. (Sahoo et al. 2015). Briefly, The bacteriocins produced, i.e., PJ4, DT24 and TSU4, by the three strains, respectively, L. helveticus PJ4, L. brevis DT24 and L. animalis TSU4 was collected after centrifugation at 10,000 g at 4 °C for 15 min. The precipitate thus obtained was further dissolved in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.0). The sample was passed through the dialysis chamber against the same buffer. The suspension was re-centrifuged and passed through cation exchange resin. The fractions obtained were pooled and subjected to reverse-phase chromatography. The final bacteriocin products were pooled and were pooled and stored at − 20 °C before being used for treatment strategies. The molecular weight of bacteriocin DT24 was found to around 7 kDa, while that of bacteriocin PJ4 was estimated to be around 6.5 kDa. The molecular weight of bacteriocin TSU4 was found to be around 4 kDa.

Bacteriocin PJ4, isolated and purified from L. helveticus PJ4 (NCBI Accession No. JQ068823) isolated from feces of male Wistar rats (Jena et al. 2013), bacteriocin DT 24, isolated from L. brevis DT24 (NCBI Accession No. JX163909), isolated from vagina of healthy women (Trivedi et al. 2013) and bacteriocin TSU4, purified from L. animalis TSU4 (NCBI accession no. KJ412485) isolated from fish gut (Sahoo et al. 2015) were used in the concentration of 50 μl/mL/animal/day for 30 days. Bacteriocins were suspended in PBS (phosphate buffer saline) buffer (10 mM, pH 7.2) for animal experimentation and PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.2) was used as the vehicle control in the control group.

Experimental design

The animals were randomized into five different groups with four animals each, control group (C), high fat-fed group (H), high fat-fed group followed by DT24 (H + D), high fat-fed group followed by PJ4 (H + P) and high fat-fed group followed by TSU4 (H + T). Control groups were fed with diets containing normal rodent diets (chow pellet from Amrut agro foods, Mumbai) and considered as control, high fat diet (HFD) group of animals were fed with additional 65% sugar in chow pellet. After 200 days, animals were found to be obese, the treatment was administered for 30 days with 50 μl/mL/animal/day bacteriocins for 30 days individually.

Parameters

Body weight was measured once a week till the end of the study and adipose tissue weight was taken at the end of study at the time of autopsy.

Fecal sample collection

Fecal samples excreted during the last 24 h of the experiment were collected from the cages of the mice, each sample thus representing the four animals, which were caged together. DNA were extracted using Quagen Bacterial DNA isolation kit. The Specific 16 s rDNA of major bacterial phyla and species like Bacteroidates (Forward Primer: CATGTGGTTTAATTCGATGAT; Reverse Primer: AGCTGACGACAACCATGCAG), Proteobacteria (Forward Primer: CATGACGTTACCCGCAGAAGAAG; Reverse Primer: CTCTACGAGACTCAAGCTTGC), Clostridia (Forward Primer: GCACAAGCAGTGGAGT; Reverse Primer: CTTCCTCCGTTTTGTCAA) and Bifidobacteria (Forward Primer: GCGTGCTTAACACATGCAAGTC; Reverse Primer: CACCCGTTTCCAGGAGCTATT) were used to quantify fecal microbiota using qPCR (Applied biosystem 7500 Fast real-time machine and Syber® Premix Ex Taq TMII from Takara).

Estimation of SCFAs (metabolites)

SCFAs was estimated from the fresh fecal samples of animals by HPLC analysis (ZORBAX, eclipse plus Phenyl-Hexyl, Agilent, USA) (Cleusix et al. 2008). 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 2.5) was used as a mobile phase.

Blood collection and serum biochemical assays

Retro-orbital plexus blood was collected in tubes from the mouse under a mild anesthetic condition. Tubes were centrifuged for serum collection. The serum were collected post treatment and analyzed for fasting blood glucose, triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), HDL and CRP concentrations in the plasma using a Accucare Diagnostic Kit (Mumbai, India).

Histopathological analysis

Adipose tissues were dissected out at the time of autopsy at the end of the study from all the animals and were subjected to histopathological analysis and gene expression studies. For histopathological analysis, part of adipose tissue was fixed in formalin and was subsequently dehydrated, following by embedding in paraffin was. The paraffin embedded tissues were section in microtome with a thickness of 5 μm sections (Yorco Sales Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi) and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The histopathological tissue sections were viewed and photographed using a Cat-Cam 3.0MP Trinocular microscope with an attached digital 3XM picture camera (Catalyst Biotech, Mumbai, India).

Serum LPS and hormonal estimation

The LPS using Pierce LAL Chromogenic Endotoxin Quantitation Kit, USA and hormones, i.e., insulin, glucagon and free fatty acids (FFA) was carried out by pre-coated ELISA kit (Merck, Germany).

Serum cytokine analysis

Blood was collected from retro-orbital plexus 2 days before autopsy from all the animals. Fresh serum were for the estimation of IL1β, IL6, IL10, IL14, IL17, TNFα, IFNγ and MCP-1 using ELISA kit standard protocol instruction (Sandwich ELISA Kit by Peprotech, Israel).

Tissue gene expression

Total RNA was isolated from fresh adipose tissue using TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocols. RNA was quantified by determining optical density at 260 nm, while purity was determined by calculating the ratio of 260 nm and 280 nm using nanodrop. The mRNA expression of various inflammatory genes, such as TLR2, TLR4, NLR1, NF-κB, NRLP3, GLUT4, GLP-1 and Caspase-1 was performed. The mRNA expression of Adiponectin, Leptin, Resistin, PPAR-α, PPAR-γ and ZO-1were also analyzed. The reverse transcription (RT) was performed using a first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) according to the mentioned protocol. The β-actin was served as an internal control (Kurland et al. 2006). The RT-PCR reaction was performed on Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System to check the relative expression using SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ II (Tli RNaseH Plus) (Takara Bio Inc, Japan). The relative quantification of gene expression was performed using the comparative threshold cycle method (∆∆CT).

Statistical analysis

Graphpad prism V.6 was used to perform statistical analysis. One-way anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine significance level at 95% significant interval between experimental groups. All values are expressed as mean ± SD, * or # in all figure indicates significance level, * when compared with control and # when compared with HFD group, *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001; # p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 and ####p < 0.0001.

Results

Effect on weight and blood biochemical parameters

The body weight gain was found to be significantly increased in HFD compared to the control group. Body weight gain was also significantly high in HFD group fed with DT24 (H + D group). The PJ4 and TSU4 groups did not show any increase compared to control group. While these groups showed significant decline as compared HFD and HFD + DT24 group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect on body and tissue weight and serum biochemical parameters

| Parameters | Experimental groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | HFD | HFD + DT24 | HFD + PJ4 | HFD + TSU4 | |

| Body weight gain (%) | 18.7 ± 1.44 | 54.8 ± 5.67**** | 29.8 ± 4.56**** | 10.2 ± 2.17#### | 21.4 ± 7.12#### |

| Adipose Tissue (gms) | 4.5 ± 1.24 | 10.2 ± 3.97 | 11.6 ± 3.15 | 5.2 ± 1.87 | 7.7 ± 2.87 |

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) | 84.3 ± 1.4 | 153.7 ± 5.6**** | 140.9 ± 7.78**** | 97.8 ± 2.98#### | 123.6 ± 3.5****, ### |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 50.6 ± 6.75 | 173.8 ± 10.67**** | 160.8 ± 11.62**** | 101.7 ± 10.2**** #### | 148.5 ± 11.7**** ## |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 107.06 ± 6.27 | 193.61 ± 14.62**** | 203.3 ± 32.7 **** | 120.8 ± 22.4#### | 152.4 ± 24.9****, #### |

| HDL | 58.21 ± 13.47 | 36.62 ± 7.55 | 40.9 ± 3.19 | 48.22 ± 10.46 | 41.9 ± 3.90 |

| CRP | 3.93 ± 0.35 | 10.67 ± 0.78 | 9.4 ± 1.28 | 5.72 ± 0.40 | 6.73 ± 0.25 |

Body and tissue weight analysis and serum biochemical parameters in different animal groups. Values are expressed as Mean ± SD of four independent values. Graphpad prism V.6 was used to perform statistical analysis

*when compared with control or #when compared with HFD group

****p < 0.0001; ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 and ####p < 0.0001

Adipose tissue weight although showed difference in all these groups but they were not significant. Fasting blood sugar was significantly increased in HFD, HFD + DT24 and HFD + TSU4 group. HFD + PJ4 did not result in elevation in fasting blood glucose. Both HFD + PJ4 (p < 0.0001) and HFD + TSU4 (p < 0.001) showed significant drop in the blood glucose when compared with HFD group. Similar trend was found in triglycerides and total cholesterol. On the contrary, HDL and CRP showed visible fluctuation in their values in all the four treated groups but the changes were non-significant (Table 1).

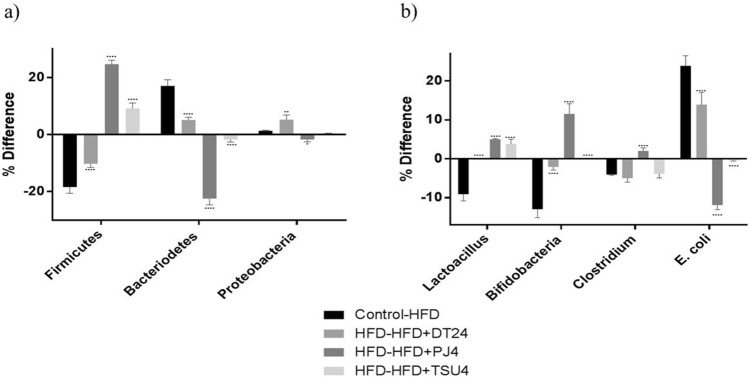

Effect on gut dominant bacterial phyla and genera

The gut microflora was expressed as difference among two groups. High fat diet induction showed significant reduction in the Firmicutes, while increased Bacteroidetes and did not show much difference in Proteobacteria. When HFD and HFD + DT24 groups were compared, it also showed similar trend, i.e., decreased Firmicutes, increased Bacteroidetes and marginal increase in Proteobacteria. When HFD was compared with HFD + PJ4 and HFD + TSU4, both showed significant reversal of the characteristics, i.e., elevated Firmicutes, decreased Bacteroidetes and proteobacteria (Fig. 1a). The gut microbiota was also modulated following dietary administration of HFD diet. The modulation was studied on most abundant population, i.e., Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, Clostridia and E. coli (Fig. 1b). Difference between the control and HFD group significantly decreased the Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria and Clostridia numbers while an increase in the E. coli was observed. HFD and HFD + DT24 did not show much difference when compared with Control-HFD group. Comparison between HFD and HFD + PJ4 and with HFD + TSU4 showed significant increase in the Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria and Clostridia and significant decrease in E. coli (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Gut microflora Analysis of Major Phyla and Species expressed as % difference between five study groups. a % Difference in three major phyla; (b) % difference in four major species. Values are expressed as Mean ± SD of four independent values. Graphpad prism V.6 was used to perform statistical analysis. Significant was compared with % difference obtained in Control-HFD group. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001

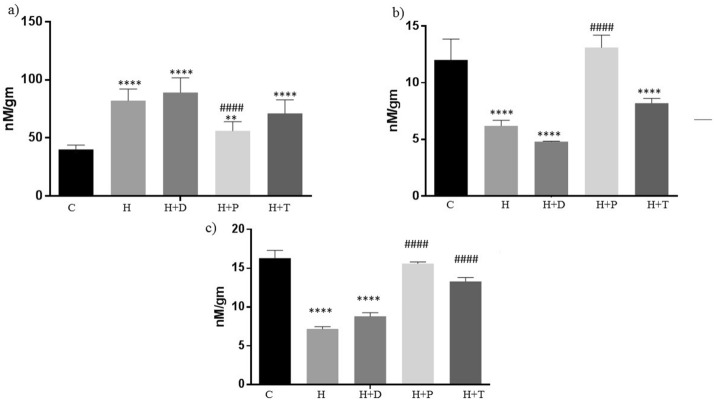

Effect on short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

The effect HFD diet and its treatment with three bacteriocins on the excreted SCFA, i.e., acetate, propionate and butyrate was studied. (Fig. 2). HFD fed animals had shown significant increase in the acetate, while decrease in propionate and butyrate levels when compared with the control. Treatment with DT24 did not show much change as compared to HFD group, instead had more significant decline compared to HFD group in acetate and propionate levels. Treatment with PJ4 marginally decreased acetate, significantly increased propionate and butyrate as compared to HFD group. While TSU 4 treatment did not show significant change in the acetate and propionate levels but had a significant increase in the butyrate levels (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Estimation of Microbial metabolites, i.e., short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in different animal groups. (a) Acetate, (b) Propionate, (c) Butyrate. Values are expressed as Mean ± SD of four independent values. Graphpad prism V.6 was used to perform statistical analysis. *when compared with control or #when compared with HFD group, in all figure indicates significance level, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001 **** p < 0.0001; #### p < 0.0001

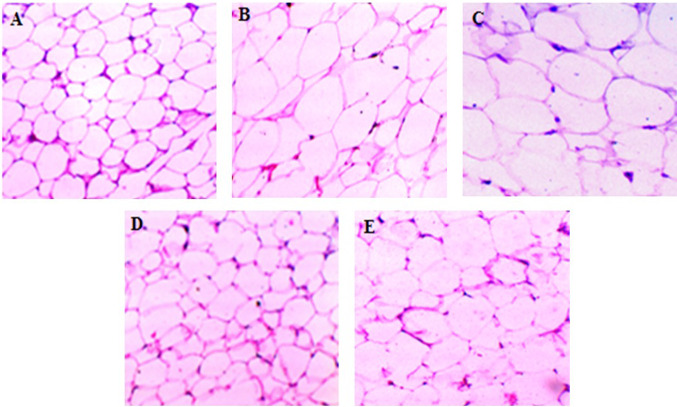

Histopathological analysis

The hematoxylin and eosin staining of adipose tissue showed that, the mean area of adipocytes was found to be enlarged in HFD administrated and HFD + DT24 group of animals compared with the control group. Both HFD + PJ4 and HFD + TSU4 groups had shown comparatively decreased adipocytes size compared to HFD group (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Histopathological analysis of Adipose tissue in different animal groups. (a) control, (b) high fat diet group, (c) high fat diet group treated with DT24, (d) high fat diet group treated with PJ4, (e) high fat diet group treated with TSU4

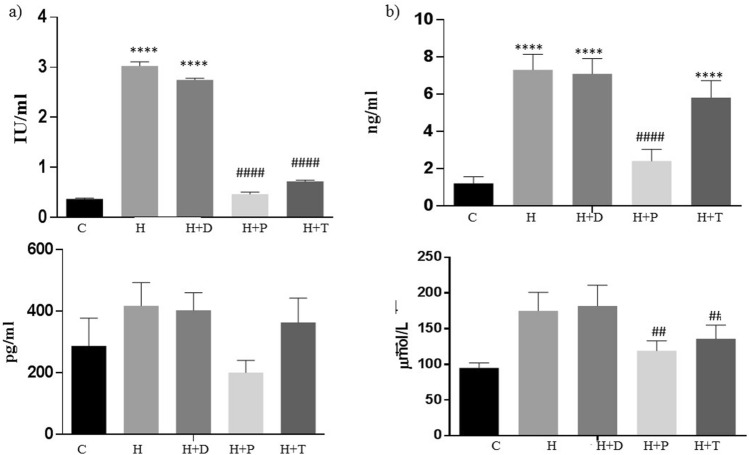

Effect on Serum LPS and hormonal estimation

The LPS levels were found to be significantly increased in HFD group, which is in concurrence to the microflora analysis which showed increased E. coli levels which are Gram negative strains with LPS on their cell wall. Treatment with DT24 did not bring down the elevated LPS levels following HFD feeding. LPS levels were significantly decreased in PJ4- and TSU4-treated groups almost comparable to that of the control levels (Fig. 4a). The insulin levels were significantly high in HFD groups which did not reduce in the DT24- and TSU4-treated groups. PJ4 treated group significantly reduced insulin as compared to HFD group (Fig. 4b). Similar trend was found in both glucagon and free fatty acids levels where PJ4 showed significant decline as compared to HFD group (Fig. 4 c-d).

Fig. 4.

Estimation of (a) LPS, (b) insulin, (c) glucagon and (d) free fatty acids in different animal groups. Values are expressed as Mean ± SD of four independent values. Graphpad prism V.6 was used to perform statistical analysis. *when compared with control or #when compared with HFD group, in all figure indicates significance level, **** p < 0.0001**** p < 0.0001; ## p < 0.01, #### p < 0.0001

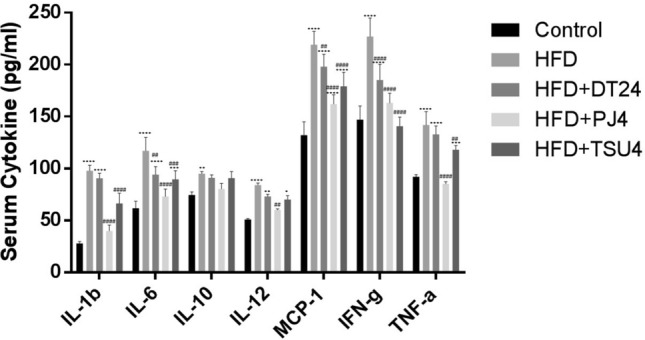

Effect on cytokine levels

Serum cytokines, i.e., IL1β, IL6, IL10, IL14, IL17, TNFα, IFNγ and MCP-1 was estimated in all the study groups at the end of the study. HFD group of animals showed significant increase in all the cytokines studies. Treatment with DT24 did not show any change in the increased levels. PJ4 and TSU4 both showed significant reduction in the levels. PJ4 was more effective than TSU4 in inducing the effect on the cytokines (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Serum Cytokines Analysis in different animal groups. Values are expressed as Mean ± SD of four independent values. Graphpad prism V.6 was used to perform statistical analysis. *when compared with control or #when compared with HFD group, in all figure indicates significance level, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001 * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001; ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 and #### p < 0.0001

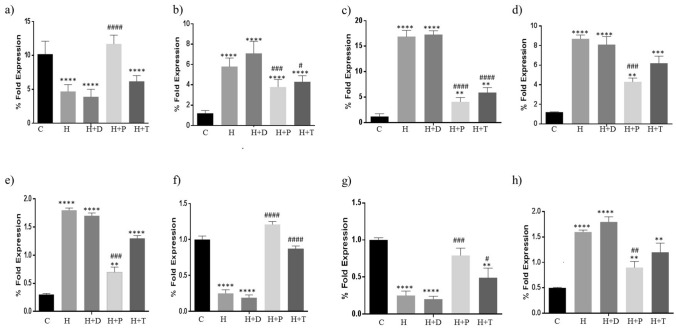

Tissue gene expression

The effect on TLR2,4, NLR1, NFkB, NLRP3, GLUT-4, GLP1 and Caspase 1 expression is shown in Fig. 6. In HFD group, there was a significant reduction in TLR-2 expression (Fig. 6a) due to significant decline in the Gram positive strains as shown in the gut microflora study (Fig. 1b). On the contrary, TLR 4, NF-kB and NLR-2 were significantly increased (Fig. 6 b-d). This is due to elevated Gram negative population and increased serum LPS levels. NLRP3 and Caspase 3 have a direct correlation. NLRP3 is activated through stress and elevated LPS in the extracellular matrix due to alteration in the gut microflora towards Gram negative population. In the present study, NLRP3 and Caspase 1 were significantly elevated in the HFD group (Fig. 6 e, h). GLUT-4 and GLP1 are known to play a key role in glucose utilization by the body. Increased glucose is indication of decreased GLUT-4 and GLP-1 expression. The tissue expression of GLUT-4 and GLP-1 was significantly reduced in HFD group indicated hampered glucose homeostasis (Fig. 6 f, g). Treatment with DT24 did not result in any changes in the HFD-induced parameters. Both PJ4 and TSU4 were effective in significant reversal of the altered parameters (Fig. 6 a–h).

Fig. 6.

Estimation of (a) TLR-2, (b) TLR-4, (c) NLR-1, (d) NF-kB, (e) NLRP3, (f) GLUT-4, (g) GLP-1 and (h) Caspase-1 in different animal groups. Values are expressed as Mean ± SD of four independent values. Graphpad prism V.6 was used to perform statistical analysis. *when compared with control or #—when compared with HFD group, in all figure indicates significance level, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001 ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 and #### p < 0.0001

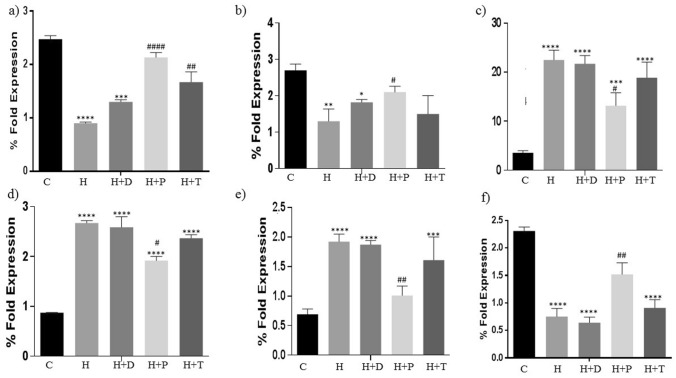

Adipokines as well as tight junction complex expression were also determined in all the study groups. Resistin and adiponectin are important for the downregulating the adipose tissue proliferation. Both these adipokines were significantly decreased in HFD group (Fig. 7 a, b). Treatment with DT24 did not improve the same but PJ4 and TSU4 significantly reversed the effect. Leptin increases during adipose tissue inflammation. It was increased in HFD and DT24 treatment and was down regulated in PJ4- and TSU4-treated groups (Fig. 7c). PPAR and were significantly increased in the HFD and DT24 group and was decreased in PJ4 and TSU4 treated group (Fig. 7d-e). The tight junctional complex marker ZO-1 is a crucial indicator of intactness of the tissue. ZO-1 was significantly decreased in HFD- and DT24-treated group and was increased in the PJ4 and TSU 4 groups indicating regaining of the functional integrity of the tissue in PJ4- and TSU4-treated groups (Fig. 7f).

Fig. 7.

Estimation of (a) Resistin, (b) Adiponectin, (c) Leptin, (d) PPAR-, (e) PPAR- and (f) Zonal Occludin (ZO-1) in different animal groups. Values are expressed as Mean ± SD of four independent values. Graphpad prism V.6 was used to perform statistical analysis. *when compared with control or #when compared with HFD group, in all figure indicates significance level, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, #### p < 0.0001

Discussion

It has now been widely reported about the direct association between the gut microfloral dysbiosis with obesity and other metabolic dysregulations. Alterations in the gut microbiota are one of the leading causes of weight gain and abnormal glucose and fat metabolism leading to obesity and metabolic disorder.

Manipulating the gut microbiota from the point of view of interfering with inter microbial communication is one of the newer approached to treat gut-associated diseases (Seshadri 2017). Alternatively, there has been an extensive use of probiotics and its products as a strategy to prevent or/and treat obesity. Various studies have been carried out using single probiotic strain and a mixture probiotic strains to modulate the weight gain (Cani and Jordan 2018; Zhang et al. 2018; Carding et al. 2015). Probiotics has been reported to improve the altered metabolic functions as well as caused significant reduction in the body weight through their potential in altering the gut microflora (Ejtahed et al. 2019; Schneeberger et al. 2015). However, the results obtained are not consistent. In the present study, we tried to evaluate the efficacy of the bacteriocins produced by probiotic strains on the obesity induced by high fat diet.

The bacteriocin TSU4 was demonstrated as is non-immunogenic, safe, nontoxic, and possessed strong antimicrobial activity against Gram negative strains (Sahoo et al. 2015) was used in the present study. Other bacteriocins, i.e., PJ4 and DT24 were most effective in inhibiting the growth of pathogenic strains such as E. coli, E. faecalis, S. aureus, E. faecium, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa (Trivedi et al. 2013; Jena et al. 2013).

Consumption of high fat diet in rodents has been widely reported as an ideal model to mimic the human metabolic disorder condition (Panchal and Brown 2011). In the present study, HFD diet resulted in significant weight gain along with increased adipose tissue weight. Similar results were also reported by other researchers (Rocha et al. 2019; Balolong et al. 2017). Diet is one of the major determining factors which influenced gut microbiota composition of the host and affects its physiological functioning (Ribeiro et al. 2005).

Various studies have indicated the consumption of HFD induced an increased adipocyte morphology, along with elevated macrophage infiltration and increased secretion of inflammatory mediators associated with obesity pathogenesis (Blüher 2016). In our present study, there has been an increase in the adipose tissue weight and the morphological changes also suggested increase in the size which was reduced in PJ4- and TSU4-treated groups. All the inflammatory mediators also showed significant increase in the HFD group.

There has been an increased expression of PPARa reported which is induced due to fatty acid oxidation (Gross et al. 2017). In the present investigation, both PPARa and PPARg showed significant increase. Similar results were also reported by Ashrafian et al., (Ashrafian et al. 2019).

There are increasing number of reports about the cross talk between PPARs, inflammatory cytokines and TLRs (Wahli and Michalik 2012; Stienstra et al. 2007). TLR-4 has been reported to be significantly elevated in adipose tissues through gut microbiota-derived LPS and via adipocyte lipolysis-released free fatty acids, which resulted in increased secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-a in obese animals (Gross et al. 2017; Cani et al. 2007). In the present investigation, there was a significant increase in the IL-6, TNF-a and other inflammatory cytokines following HFD diet. These cytokines returned to their control levels following treatment with PJ4 and TSU4. In the present study, there was a significant decrease in the TLR-2 and elevation in TLR-4 and NF-kB. Animal experiments using probiotic strains also reported decrease in the proinflammatory cytokines (Núñez et al. 2015; Qiao et al. 2015).

Adiponectin has been reported to possess anti-inflammatory effects which plays a protective role in obesity. Adiponectin suppressed TNFa production in obese mice (Xu et al. 2003; Maeda et al. 2002). In the present study, Resistin and adiponectin showed significant reduction in HFD group and were elevated in the treatment groups. Leptin on the other hand had a pro-inflammatory effect, was significantly increased in the obesity induced group and was decreased in the bacteriocin-treated groups.

The microfloral quantification showed significant alteration in the proportion of the three gut dominant phyla, i.e., Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria and four dominant species i.e., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacteria, Clostridia and Escherichia population. Devaraj et al. reported that in obese conditions there is an increase in the Firmicutes genus and a decrease of the Bacteroidetes and this imbalance is crucial for the onset and progression of obesity (Devaraj et al. 2013). Similar findings were also reported by Lone et al., (Lone et al. 2018). In one of the clinical studies, Ley et al. reported changes in the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio were diet dependent, which changed with shifting to high fat diets (Ley et al. 2006). In the present investigation, the results obtained were in concurrence with the already reported data.

Conclusion

High fat diet can now be clearly correlated with weight gain, altered morphology of the adipose tissue, leading to gut dysbiosis. The alteration in the gut microflora in turn leads to significant alteration in the inflammatory mediators, cytokines and adipokines. Bacteriocins are novel antimicrobial peptides produced by probiotic strains to enhance its efficacy. In the present study, three bacteriocins isolated and purified from probiotic Lactobacillus strains, isolated from different sources were tested for their anti-obesity potentials. PJ4, purified from Lactobacillus, which was isolated from the rat gut showed promising results. The efficacy of bacteriocins could be dependent upon the samples from which the lactobacillus was originally isolated from. PJ4 were isolated from rat feces, which DT24 were of human origin and TSU4 were from fish gut. Bacteriocins or anti-microbial proteins/peptide could be an ideal candidate for modulating the gut microflora as they confer broad-spectrum efficacy, provide instant killing and may provide a long-term efficacy for a majority of gastrointestinal infections and gut associated disorder (Jena et al. 2011; Chi and Holo 2018; Silva et al. 2018). Majority of anti-obesity study pertaining to the modulation of gut microflora has been focused on use of probiotic strains, antibiotics. Hence, this would probably first of its kind report on the use of bacteriocins for their anti-obesity strategy. The exact mode of action needs to be determined to promote the use of PJ4 as a potent anti-obesity compound.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan, China and Nirma University for financial assistance.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

There is no conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- Alexandraki V, Tsakalidou E, Papadimitriou K, Holzapfel W. Status and trends of the conservation and sustainable use of microorganisms in food processes. FAO. 2013;65:160. [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafian F, Shahriary A, Behrouzi A, Moradi HR, Raftar SKA, Lari A, Hadifar S, Yaghoubfar R, Badi SA, Khatami S, Vaziri F, Siada SD. Akkermansia muciniphila-derived extracellular vesicles as a mucosal delivery vector for amelioration of obesity in mice. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2155–2172. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balolong MP, Bautista RLS, Ecarma NCA, Balolong EC, Hallare AV, Elegado FB. Evaluating the anti-obesity potential of Lactobacillus fermentum 4B1, a probiotic strain isolated from balao-balao, a traditional Philippine fermented food. Int Food Res J. 2017;24(2):819–824. [Google Scholar]

- Blüher M. Adipose tissue inflammation: a cause or consequence of obesity related insulin resistance? Clin Sci. 2016;130:1603–1614. doi: 10.1042/CS20160005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani PD, Jordan BF. Gut microbiota-mediated inflammation in obesity: a link with gastrointestinal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:671–682. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani PD, Everard A, Duparc T. Gut microbiota, enteroendocrine functions and metabolism. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:935–940. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carding S, Verbeke K, Vipond DT, Corfe BM, Owen LJ. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:26191. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v26.26191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H, Holo H. Synergistic antimicrobial activity between the broad spectrum bacteriocin garvicin KS and nisin, farnesol and polymyxin b against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Curr Microbiol. 2018;75(3):272–277. doi: 10.1007/s00284-017-1375-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleusix V, Lacroix C, Vollenweider S, Le Blay G. Glycerol induces reuterin production and decreases escherichia coli population in an in vitro model of colonic fermentation with immobilized human feces. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2008;63(1):56–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaraj S, Hemarajata P, Versalovic J, Dra Lau L. La microbiota intestinal humana y el metabolismo corporal: Implicaciones con la obesidad y la diabete. Acta Bioquím Clín Latinoam. 2013;47(2):421–434. [Google Scholar]

- Ejtahed HS, Angoorani P, Soroush AR, Atlasi R, Hasani-Ranjbar S, Mortazavian AM, et al. Probiotics supplementation for the obesity management; a systematic review of animal studies and clinical trials. J Funct Foods. 2019;52:228–242. [Google Scholar]

- Engin A. The definition and prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;960:1–17. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Williamson DF, Liu S. Weight change and diabetes incidence: findings from a national cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:214–222. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frühbeck G, Gomez-Ambrosi J, Bal MJF, Burrell MA. The adipocyte: a model for integration of endocrine and metabolic signaling in energy metabolism regulation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280:E827–E847. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.6.E827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Ann Rev Immunol. 2011;29:415–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross B, Pawlak M, Lefebvre P, Staels B. PPARs in obesity-induced T2DM, dyslipidaemia and NAFLD. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:36–49. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jena PK, Trivedi D, Purandhar K, Chaudhary H, Seshadri S. Antimicrobial Peptides and its Role in Gastro-Intestinal Diseases: a Review. J Animal Sci Adv. 2011;1(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jena PK, Trivedi D, Chaudhary H, Sahoo TK, Seshadri S. Bacteriocin PJ4 active against enteric pathogen produced by Lactobacillus helveticus PJ4 isolated from Gut microflora of wistar rat (Rattus norvegicus): Partial purification and characterization of bacteriocin. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2013;169(7):2088–2100. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-0044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurland AR, Schreiner H, Diamond G. In Vivo Beta-Defensin gene expression in rat gingival epithelium in response to actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans infection. J Periodontal Res. 2006;41(6):567–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00909.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung C, Rivera L, Furness JB, Angus PW. The role of the gut microbiota in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:412–425. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nat. 2006;444:1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lone JB, Koh WY, Parray HA, Paek WK, Lim J, Rather IA, et al. Gut microbiome: Microflora association with obesity and obesity-related comorbidities. Microb Pathog. 2018;124:266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda N, Shimomura I, Kishida K, Nishizawa H, Matsuda M, Nagaretani H, Furuyama N, Kondo H, Takahashi M, Arita Y, et al. Diet-induced insulin resistance inmice lacking adiponectin/ACRP30. Nat Med. 2002;8:731–737. doi: 10.1038/nm724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nes IF, Yoon S-S, Diep DB. Ribosomally synthesiszed antimicrobial peptides (Bacteriocins) in lactic acid bacteria: A Review. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2007;16:675–690. [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graet N, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núñez IN, Galdeano CM, de LeBlanc ADM, Perdigón G. Lactobacillus casei CRL 431 administration decreases inflammatory cytokines in a diet-induced obese mouse model. Nutr. 2015;31:1000–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchal SK, Brown L. Rodent models for metabolic syndrome research. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:351982. doi: 10.1155/2011/351982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Chanona E, Trinchieri G. The role of microbiota in cancer therapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;39:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, Depommier C, Van Hul M, Geurts L, et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23:107–113. doi: 10.1038/nm.4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y, Sun J, Xia S, Li L, Li Y, Wang P, et al. Effects of different Lactobacillus reuteri on inflammatory and fat storage in high-fat diet-induced obesity mice model. J Funct Foods. 2015;14:424–434. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HE, Valsania P, Halter JB, Lin X. Relation of weight gain and weight loss on subsequent diabetes risk in overweight adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:596–602. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.8.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro CCC, Tabchoury CPM, Cury AADB, Tenuta LMA, Rosalen PL, Cury JA. Effect of starch on the cariogenic potential of sucrose. Br J Nutr. 2005;94(1):44–50. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha VDS, Claudio ERG, Silva VL, Cordeiro JP, Domingos LF, Cunha MRH. High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity Model Does Not Promote Endothelial Dysfunction via Increasing Leptin/Akt/eNOS Signaling. Front Physiol. 2019;10:268–278. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo TP, Jena PK, Patel AK, Seshadri S. Purification and molecular characterization of the novel highly potent bacteriocin TSU4 produced by lactobacillus animalis TSU4. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2015;177:90–104. doi: 10.1007/s12010-015-1730-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeberger M, Everard A, Gómez-Valadés AG, Matamoros S, Ramírez S, Delzenne NM, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila inversely correlates with the onset of inflammation, altered adipose tissue metabolism and metabolic disorders during obesity in mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16643. doi: 10.1038/srep16643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri S. Microbial communication via quorum sensing: influence and alteration of gut ecosystem. JSM Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;4(1):1020–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Silva CCG, Silva SPM, Ribeiro SC. Application of bacteriocins and protective cultures in dairy food preservation. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:594. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein CJ, Colditz GA. The epidemic of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2522–2525. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stienstra R, Duval C, Müller M, Kersten S. PPARs, obesity, and inflammation. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:95974. doi: 10.1155/2007/95974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stienstra R, Tack CJ, Kanneganti TD, Joosten LAB, Netea MG. The inflammasome puts obesity in the danger zone. Cell Metabol. 2012;15:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres S, Fabersani E, Marquez A, Gauffin-Cano P. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic syndrome. The proactive role of probiotics. Eur J Nutr. 2019;58:27–43. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1790-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi D, Jena PK, Patel JK, Seshadri S. Partial purification and characterization of a Bacteriocin DT24 produced by Probiotic vaginal Lactobacillus brevis DT24 and determination of its anti-Uropathogenic Escherichia coli potential. Probiotic Antimicrob Proteins. 2013;5(2):142–151. doi: 10.1007/s12602-013-9132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vucenik I, Stains JP. Obesity and cancer risk: evidence, mechanisms, and recommendations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1271:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahli W, Michalik L. PPARs at the crossroads of lipid signaling and inflammation. Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 2012;23:351–363. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, Jha S, Zhang L, Huang MT, Brickey WJ, Ting JP. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO [World Health Organization] (2017) Obesity and overweight, fact sheet 311.

- Xu A, Wang Y, Keshaw H, Xu LY, Lam KS, Cooper GJ. The fat derived hormone adiponectin alleviates alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases in mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:91–100. doi: 10.1172/JCI17797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang Y, Ren X, Han J. The impact of the intestinal microbiome on bone health. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2018;7:148–155. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2018.01055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]