Abstract

Background

Bipolar disorder is one of the most common serious mental illnesses, affecting approximately 60 million people worldwide. Characterised by extreme alterations in mood, cognition, and behaviour, bipolar disorder can have a significant negative impact on the functioning and quality of life of the affected individual. Compared with the general population, the prevalence of comorbid obesity is significantly higher in bipolar disorder. Approximately 68% of treatment seeking bipolar patients are overweight or obese. Clinicians are aware that obesity has the potential to contribute to other physical health conditions in people with bipolar disorder, including diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of premature death in bipolar disorder, happening a decade or more earlier than in the general population. Contributing factors include illness‐related factors (mood‐related factors, i.e. mania or depression), treatment‐related factors (weight implications and other side effects of medications), and lifestyle factors (physical inactivity, poor diet, smoking, substance abuse). Approaches to the management of obesity in individuals with bipolar disorder are diverse and include non‐pharmacological interventions (i.e. dietary, exercise, behavioural, or multi‐component), pharmacological interventions (i.e. weight loss drugs or medication switching), and bariatric surgery.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of interventions for the management of obesity in people with bipolar disorder.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR) and the Cochrane Central Register for Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) to February 2019. We ran additional searches via Ovid databases including MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycInfo to May 2020. We searched the World Health Organization (WHO) trials portal (International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)) and ClinicalTrials.gov. We also checked the reference lists of all papers brought to full‐text stage and all relevant systematic reviews.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), randomised at the level of the individual or cluster, and cross‐over designs of interventions for management of obesity, in which at least 80% of study participants had a clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder and comorbid obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m²), were eligible for inclusion. No exclusions were based on type of bipolar disorder, stage of illness, age, or gender. We included non‐pharmacological interventions comprising dietary, exercise, behavioural, and multi‐component interventions; pharmacological interventions consisting of weight loss medications and medication switching interventions; and surgical interventions such as gastric bypass, gastric bands, biliopancreatic diversion, and vertical banded gastroplasty. Comparators included the following approaches: dietary intervention versus inactive comparator; exercise intervention versus inactive comparator; behavioural intervention versus inactive comparator; multi‐component lifestyle intervention versus inactive comparator; medication switching intervention versus inactive comparator; weight loss medication intervention versus inactive comparator; and surgical intervention versus inactive comparator. Primary outcomes of interest were changes in body mass, patient‐reported adverse events, and quality of life.

Data collection and analysis

Four review authors were involved in the process of selecting studies. Two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies identified in the search. Studies brought to the full‐text stage were then screened by another two review authors working independently. However, none of the full‐text studies met the inclusion criteria. Had we included studies, we would have assessed their methodological quality by using the criteria recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. We intended to combine dichotomous data using risk ratios (RRs), and continuous data using mean differences (MDs). For each outcome, we intended to calculate overall effect size with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Main results

None of the studies that were screened met the inclusion criteria.

Authors' conclusions

None of the studies that were assessed met the inclusion criteria of this review. Therefore we were unable to determine the effectiveness of interventions for the management of obesity in individuals with bipolar disorder. Given the extent and impact of the problem and the absence of evidence, this review highlights the need for research in this area. We suggest the need for RCTs that will focus only on populations with bipolar disorder and comorbid obesity. We identified several ongoing studies that may be included in the update of this review.

Plain language summary

Interventions for the management of obesity in people with bipolar disorder

Why is this review important?

Bipolar disorder is one of the most common serious mental illnesses and impacts mood, thinking, behaviour, functioning, and quality of life. Approximately 60 million people worldwide are affected by bipolar disorder. Obesity is commonly associated with the illness, and when this happens, it can cause other physical health conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, leading to premature death. Many approaches are used to manage obesity in bipolar disorder, but as yet, we are not sure if any one or a combination of approaches is effective.

Who might be interested in this review?

Psychiatrists and any members of the multi‐disciplinary team caring for individuals with bipolar disorder and comorbid obesity. Findings from this review will also be of interest to researchers and people with bipolar disorder and their families.

What question does this review aim to answer?

This review sought to assess the effectiveness of interventions used to address the problem of obesity in bipolar disorder.

Which studies were included in the review?

We searched databases up to February 2019 for studies of interventions used to manage the problem of obesity in individuals with bipolar disorder. None of the studies reviewed met the inclusion criteria.

What does evidence from the review reveal?

There is an absence of evidence for the effectiveness of pharmacological, non‐pharmacological, or surgical interventions for management of obesity in individuals with bipolar disorder.

What should happen next?

There is an urgent need to undertake randomised controlled trials to assess the effectiveness of non‐pharmacological, pharmacological, and surgical approaches for the treatment of obesity in bipolar disorder populations. Trials should include only people with a clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder and comorbid obesity.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice

Findings from this review suggest that there is no evidence to support non‐pharmacological, pharmacological, or surgical approaches for the management of obesity in bipolar disorder.

Implications for research

There is a need to undertake well‐designed randomised controlled trials of non‐pharmacological, pharmacological, and/or surgical interventions to address obesity in bipolar disorder. Studies must focus on bipolar participants only, as distinct from mixed populations with serious mental illness, and all trial participants must have received a diagnosis of comorbid obesity. We identified several ongoing studies that may be included in the update of this review.

Background

Bipolar disorder is one of the most common serious mental illnesses (SMIs) characterised by mood instability, results in marked impairment in overall functioning and health‐related quality of life (De Hert 2011; Klienman 2003). Bipolar disorder is the sixth leading cause of disability worldwide in people aged 15 to 44 years (Klienman 2003), and it has a worldwide prevalence of 2.4% (Merikangas 2011). Globally, bipolar disorder affects approximately 60 million people (WHO 2015).

Weight gain and obesity have long been recognised in mental health practice as matters of significant concern (Baptista 1999; McIntyre 2001; McIntyre 2010). Individuals with bipolar disorder are more frequently overweight (body mass index (BMI) 25.0 to 29.9) or obese (BMI ≥ 30), or have a higher prevalence of central obesity (abdominal fat), or both, compared with the general population (McElroy 2004). Clinical research suggests that up to 68% of bipolar patients seeking treatment are overweight or obese (De Hert 2011). Analysis of data from the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication demonstrated that obesity is associated with a significant increase in a lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder (Simon 2006).

Clinical research suggests that approximately 68% of treatment‐seeking individuals with bipolar disorder are overweight or obese (McElroy 2004). Traditionally, the issue of weight gain in people with mental illness was perceived as less important than mental wellness (Fontaine 2001). However, clinicians today recognise that obesity has the potential to contribute to other physical health conditions in people with bipolar disorder, including diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome (MetS), cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease (De Hert 2011). Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of premature death in bipolar disorder, occurring a decade or more earlier, on average, than in the general population (Goldstein 2014).

Weight gain is a commonly reported side effect of medications used in the treatment of bipolar disorder and is associated with lower quality of life in this population. Factors contributing to obesity in the bipolar disorder population are diverse but generally stem from illness‐related factors (mood‐related factors, i.e. mania or depression), treatment‐related factors (weight implications and other side effects of medications), or lifestyle factors (physical inactivity, poor diet, smoking, and substance abuse) (De Hert 2011; Firth 2019; Newcomer 2007; Stahl 2009; Ussher 2011), or a combination of some or all of these factors. Obesity and related physical illnesses are associated with aggravation of depression, morbid course of illness, non‐adherence with treatment regimens, poor treatment outcomes, and an increased prevalence of suicide in people with bipolar disorder (Fagiolini 2003).

Bipolar disorder leads to a significant economic burden on both the individual and society as a whole. Indirect physical health costs account for most of this burden, which is due largely to lost work productivity of people with bipolar disorder and their carers. Hospitalisation and emergency department services, psychiatric visits, and costs of medication are the main contributors to direct costs (Guvstavsson 2011).

Description of the condition

Bipolar disorder is a recurrent and sometimes chronic mental illness. The term 'bipolar disorder' refers to a group of affective or mood disorders, typically characterised by episodes of depression and either mania (elated or irritable mood or both), manifested as increased energy and reduced need for sleep, or hypomania, symptoms of which are less severe or less protracted than those of mania. The Fifth Edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐V) identifies four subtypes of bipolar disorder (APA 2013).

Bipolar disorder type I is defined as episodes of depression and at least one episode of mania.

Bipolar disorder type II is defined as at least one episode of major depression and at least one hypomanic episode but no manic episodes.

Cyclothymic disorder refers to a number of episodes of hypomanic and depressive symptoms in which the depressive symptoms do not meet the criteria for depression.

Bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) refers to depressive and hypomanic episodes that may change rapidly, yet do not meet the full diagnostic criteria for any other illnesses

The World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10) defines bipolar disorder as characterised by two or more episodes in which the individual's mood and activity levels are very disturbed; bipolar disorder may involve an elevation of mood with increased energy and activity (hypomania or mania), and at other times lowering of mood and decreased energy and activity (depression) (WHO 1992). Repeated episodes of hypomania or mania only are classified as bipolar disorder.

Description of the intervention

A diversity of interventions are available for the treatment of obesity. The main interventions can be classified into non‐pharmacological, pharmacological, and surgical.

Non‐pharmacological interventions

Non‐pharmacological interventions include four approaches.

Dietary interventions

This approach focuses on lifestyle modification, generally encompassing diet changes, whereby there is an attempt to enhance dietary restraint by providing adaptive dietary strategies and by discouraging maladaptive dietary practices (Shaw 2005). This approach also includes self‐monitoring. The aim is to achieve weight loss by reducing daily intake of food (Harvey 2004; Shaw 2005).

Exercise interventions

This approach aims to increase daily expenditure of energy via increased physical activity (Harvey 2004;Shaw 2005). Physical activity approaches include all types of aerobic and anaerobic exercise approaches.

Behaviour change interventions

The aim of behaviour change strategies is to elicit behaviour change by enabling individuals to explore and resolve mixed feelings they may have about change. Interventions such as motivational interviewing, which is grounded in a client‐centred approach, help individuals move to greater readiness to change behaviour (Rollnick 1995). Another approach is cognitive‐behavioural therapy, which teaches individuals behavioural and cognitive strategies, for example, breaking negative behaviour cycles, with focus on achieving and maintaining lifestyle changes (Beck 1979). This can be achieved by stimulus control, goal‐setting, and self‐monitoring. All of these interventions can be delivered at an individual or group level.

Multi‐component interventions

Multi‐component interventions may contain one or more components of any of the three interventions described above.

Pharmacological interventions

Pharmacological interventions may involve the following approaches.

Weight loss medication interventions

This approach involves taking drugs that inhibit appetite or food absorption, or both, or that act centrally. Obesity guidelines currently recommend that drug therapy be considered for patients with a BMI of 30 kg/m² or more (Lau 2007; Padwal 2007). Five anti‐obesity drugs are commonly used, namely, orlistat, lorcaserin, phentermine/topiramate, naloxone/bupropion, and liraglutide (Patel 2015).

Medication switching interventions

Weight gain is a well‐recognised side effect of some of the medications used in treatment for bipolar disorder (Narasimhan 2007). For example, second‐generation atypical anti‐psychotic drugs such as olanzapine have the propensity to induce weight gain (Lieberman 2005; McIntyre 2001). The mood‐stabilising drug lithium is also associated with weight gain (Shrivastava 2010). Consequently, the second pharmacological approach for managing weight gain in bipolar disorder involves switching anti‐psychotic or mood‐stabilising medications to alternative anti‐psychotic or mood‐stabilising medications with less potential for weight gain (Weiden 2007; White 2013).

Adjunctive metformin

The British Association for Psychopharmacology recommends initiation of metformin, the glucose‐lowering drug for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, for people with a history of psychosis and comorbid obesity for prevention of diabetes and treatment of anti‐psychotic‐induced weight gain (Cooper 2016).

Surgical interventions

Bariatric surgery (weight loss surgery) is considered almost exclusively for patients with a BMI of 40 kg/m² or more. It may also be considered for patients with a BMI of 35 kg/m² in the presence of an associated serious physical illness such as diabetes (NICE 2006).

How the intervention might work

Non‐pharmacological interventions

Common to all non‐pharmacological interventions for weight management is the concept of lifestyle modification of diet, physical exercise, or behaviour, or a combination of these approaches (McElroy 2009; Patel 2015). A central aim of lifestyle change approaches is to achieve and maintain weight loss by reducing caloric intake and increasing physical activity. The behavioural component seeks to inspire behaviour change toward food intake and physical activity. Weight loss, however modest, can have positive effects on overall well‐being and is considered a successful outcome, especially if maintained over time. Weight loss of between 5% and 15% has been shown to improve lipid levels and reduce low‐density lipoprotein (LDL), total cholesterol, blood pressure, and risk of cardiovascular disease (Aucott 2005; Wing 2011). Weight loss of 10 kg has been shown to decrease systolic blood pressure by 5 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by 6 mmHg (Aucott 2005). Weight loss has also been reported to improve psychological well‐being and quality of life and to facilitate a more active lifestyle, which can help to maintain or increase weight loss.

Pharmacological interventions

The five most commonly used weight loss drugs are orlistat, lorcaserin, phentermine/topiramate, naloxone/bupropion, and liraglutide (Patel 2015). Orlistat acts peripherally by preventing intestinal fat absorption by inhibiting the pancreatic lipase enzyme (Heck 2000). Lorcaserin is a selective agonist of 5‐HT2C receptors (Hurren 2011). Phentermine/topiramate is a combination treatment that consists of phentermine, which increases central noradrenaline levels, and topiramate, which is a central modulator of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (Khorassani 2015). Another combination therapy comprises the mu‐opioid receptor antagonist naloxone and bupropion (Yanovski 2015). Finally, liraglutide is a glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonist that was originally developed to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus but has now been approved for long‐term weight management. Drug therapies that are no longer used focused on centrally acting agents that targeted the catecholaminergic or serotonergic system, or both (such as sibutramine, mazindol, diethylpropion, benzphetamine, and phendimetrazine), or the cannabinoid receptor antagonist rimonabant. Due to safety concerns of previous therapeutic approaches, great care is advised in treatment for weight reduction with current drugs (American College of Cardiology 2014).

Medication switching involves changing from prescribing drugs associated with weight gain to prescribing drugs associated with less weight gain. A Cochrane Review evaluating the effects of anti‐psychotic switching for people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic‐induced weight gain concluded that patients who were switched to aripiprazole or quetiapine from olanzapine lost weight, had a reduced BMI, and had improved profiles of fasting glucose and lipids (Mukundan 2010).

Metformin may contribute to weight loss by reducing insulin resistance and suppressing appetite. A systematic review and meta‐analysis demonstrated that metformin is effective in treating anti‐psychotic‐induced weight gain in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (De Silva 2016).

Surgical interventions

Bariatric surgery for obesity includes a variety of approaches. Weight loss is achieved by reducing the size of the stomach, so that food intake is restricted and weight loss is induced (Colquitt 2014). Surgical approaches include gastric bypass, gastric bands, biliopancreatic diversion, and vertical banded gastroplasty.

Why it is important to do this review

A previous systematic review evaluated interventions targeting physical health comorbidities in people with SMI (Cabassa 2010). However, the term 'serious mental illness' is an umbrella term incorporating schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder. Our proposed systematic review seeks to focus only on people with bipolar disorder given potential differences in patterning of health risks between individuals with bipolar disorder and those with other conditions (e.g. schizophrenia) within the broader category of serious mental illness (Hayes 2017). Given the prevalence and devastating effects of obesity in this population, as well as the enormous economic burden to society, any intervention that is effective in addressing the problem of obesity in bipolar disorder would have a major impact. Psychological and health‐related quality of life improvements have been shown in people with bipolar disorder following weight loss. Moreover, weight loss allows for improved psychological functioning, a more active lifestyle, and increased physical activity, which in turn may induce further weight loss, weight maintenance, or both.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of interventions for the management of obesity in people with bipolar disorder.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomised controlled trials (RCTs), randomised at the level of the individual or cluster. We also considered studies employing a cross‐over design, using data from the first active treatment only, that is, before the first cross‐over. Non‐randomised controlled studies in which assignment to treatment group was decided through non‐random methods were not eligible for inclusion. We intended to include studies regardless of their publication status.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

All participants with a clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder and comorbid obesity were the focus of this review. No exclusion was based on type of bipolar disorder, stage of illness, age, or gender.

Diagnosis

We considered in this review only participants with a clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder and comorbid obesity. We considered bipolar disorder diagnosed according to the criteria laid out by the American Psychiatric Association in DSM‐IV or DSM‐V (APA 1994; APA 2013), or criteria specified by the WHO in ICD‐10 (WHO 1992). A clinical diagnosis of obesity was defined in the context of this review as BMI of 30 kg/m² or more. A priori, we anticipated that there would be few studies in which all participants had a clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder and comorbid obesity. Therefore, we would have included all studies in which 80% or more of the participants had both bipolar disorder and comorbid obesity.

Comorbidities

Comorbid obesity, but participants would have been included regardless of any other diagnosed comorbidity.

Setting

We applied no restriction on the treatment setting.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

We planned to include the following interventions.

1. Non‐pharmacological interventions (i.e. lifestyle modifications).

Diet.

Exercise.

Behaviour.

Multi‐component lifestyle interventions, which may include one or more of the components detailed in 1, 2, and 3 above.

We placed no restriction on who delivered the intervention or where the intervention was delivered, nor on frequency, intensity, or duration of the intervention.

2. Pharmacological interventions.

Weight loss drugs.

Medication switching.

Adjunctive metformin.

Had we included studies, there would have been no restriction on type of drug, dose, frequency of delivery, route of delivery, or length of exposure.

3. Surgical interventions.

Gastric bypass.

Gastric banding.

Biliopancreatic diversion.

Vertical banded gastroplasty.

We placed no restriction on type of surgical procedure nor on length of follow‐up.

Comparator interventions

We planned to include the following comparators.

1. Inactive comparator.

No treatment.

Treatment as usual (TAU), also called standard care or usual care.

Placebo (inactive/dummy), defined as a control condition that is regarded by researchers as inactive but is regarded by participants as active.

2. Active comparator.

A dietary intervention versus a different dietary intervention.

An exercise intervention versus a different exercise intervention.

A behavioural intervention versus a different behavioural intervention.

A medication switching intervention versus a different medication switching intervention.

A weight loss medication intervention versus a different weight loss medication intervention.

A surgical intervention versus a different surgical intervention.

Main comparisons

Planned main comparisons to be reported in 'Summary of findings' tables were as follows.

Dietary intervention versus inactive comparator.

Exercise intervention versus inactive comparator.

Behavioural intervention versus inactive comparator.

Multi‐component lifestyle intervention versus inactive comparator.

Medication switching interventions versus inactive comparator.

Weight loss medication interventions versus inactive comparator.

Surgical interventions versus inactive comparator.

Types of outcome measures

Planned primary and secondary outcomes of interest included the following:

Primary outcomes

Changes in body mass, measured as change in BMI.

Patient‐reported adverse events (e.g. pain, distress).

Quality of life measured by the following validated quality of life measurement scales: the Quality of Life in Bipolar Disorder Scale (QOL‐BD) (Michalak 2010), as well as the suite of Short Form (SF) Health Surveys originating from the SF‐36 tool (Ware 1993).

Secondary outcomes

Mood measured by validated measurement scales, for example, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) may be used to indicate depression and severity of depression (Hamilton 1960). The Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) may be used to assess the severity of manic episodes (Young 1978).

Global functioning measured by validated measurement scales, for example, the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) and the Clinical Global Impression Bipolar Scale (CGI‐BP) (Jones 1995; Spearing 1997).

Clinician‐reported adverse events (e.g. infection, drug toxicity).

Blood pressure.

Total cholesterol.

LDLs.

Blood glucose levels.

Timing of outcome assessment

We anticipated that study authors would report response rates at various time points during and post intervention; we therefore planned to subdivide the timing of outcome assessments as follows.

Short‐term effects, measured up to 12 months after completion of the intervention, which was the primary time point to be reported in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Sustained effects, measured at least 12 months after completion of the intervention.

If included studies provided data at more than one time point, we would have included one set of data in the short‐term effects meta‐analysis, choosing the time point nearest 12 months, and one set of data in the sustained‐effects meta‐analysis, choosing the longest data collection period possible.

Hierarchy of outcome measures

We planned to measure data on the primary outcome ‐ change in body mass ‐ and include them in the meta‐analysis using BMI only.

If data on change in quality of life were available from studies that were sufficiently similar to allow a meta‐analysis, we planned to perform one meta‐analysis using data measured by QOL‐BD, and a separate meta‐analysis using data from the SF suite of scales; we planned to report both of these in our 'Summary of findings' table.

For our secondary outcomes, we planned to include data from HDRS and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) in our meta‐analysis for depressed mood, and data from the YMRS in the meta‐analysis of mania. We planned to conduct separate meta‐analysis for overall global assessment using data from GAF and CGI‐BP. We did not plan to report secondary outcomes in our 'Summary of findings' table.

If a study reported an outcome in more than one way, we planned to include relevant data in each meta‐analysis.

Search methods for identification of studies

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group Specialised Register (CCMDCTR)

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group (CCMD) maintains two archived clinical trials registers at its editorial base in York, UK: a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCMDCTR‐References Register contains over 40,000 reports of RCTs on depression, anxiety, and neurosis. Approximately 50% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCMDCTR‐Studies Register, and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on a bespoke manual used in the creation of a database of mental health/psychiatry trials (PsiTri), as part of an EU funded project (please contact the CCMD Information Specialist for further details). Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group Register were collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 to 2019), Embase (1974 to 2019), and PsycINFO (1967 to 2019); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials were sourced from international trials registers via the World Health Organization trials portal (the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)) and pharmaceutical companies, and by handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings, and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of the core search strategies of CCMD (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website, and an example of the core MEDLINE search is displayed in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches

An information specialist with the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group searched the biomedical databases listed below, using relevant keywords, subject headings (controlled vocabularies), and search syntax, appropriate to each resource (to 19 February 2019) (Appendix 2),

An update search was performed on 22 May 2020, which employed a more sensitive set of terms for anti‐psychotic‐induced weight gain (Appendix 3).

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR) (all years to 14 June 2016).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, in the Cochrane Library (2020; Issue 5 of 12).

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 22 May 2020).

Ovid Embase (1974 to 2020 Week 21).

Ovid PsycINFO (all years to May Week 3 2020).

We searched international trials registries via the World Health Organization trials portal (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify unpublished or ongoing studies.

We did not apply to the searches any restrictions on date, language, or publication status.

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We searched the following sources of grey literature: theses via PsycINFO (Appendix 2); the British Library E‐theses Online Service (EthOS); and the DART‐Europe E‐theses Portal. We also checked the reference lists of all papers brought to full‐text stage and all relevant systematic reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

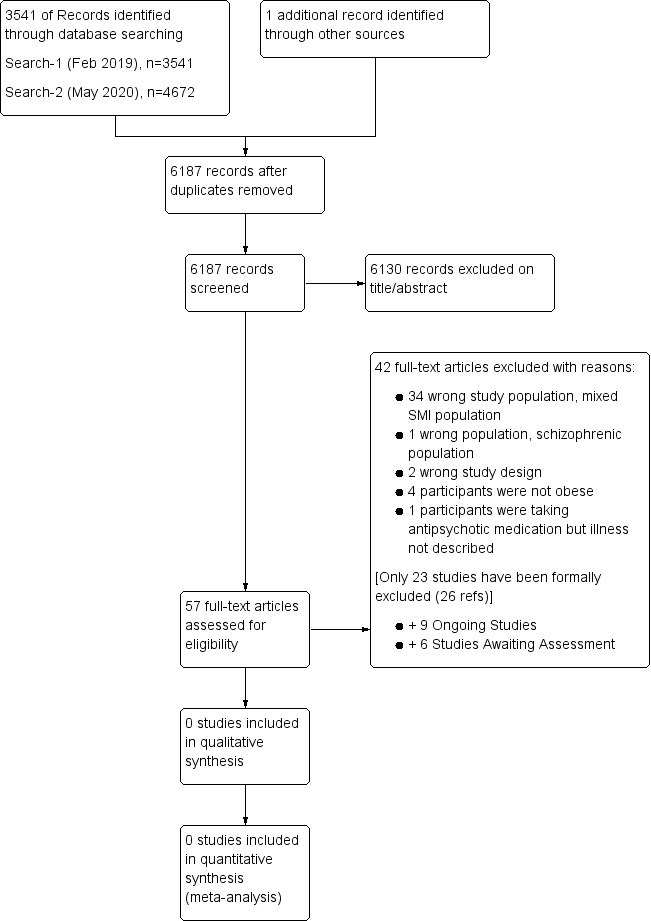

Two review authors (AT and FJ) independently screened all titles and abstracts identified through the literature searches to identify those that met the inclusion criteria. We retrieved the full text of studies identified as potentially relevant by at least one review author. Two other review authors (SS and YC) independently screened the full‐text articles for inclusion or exclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, or, when necessary, we consulted a third review author (FJ or AT). All studies excluded at the full‐text stage are listed as excluded studies, and reasons for their exclusion are presented in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The screening and selection processes are presented in the adapted PRISMA flowchart (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

We designed an electronic data extraction form, and we planned that two review authors (SS and FJ) would independently extract data from eligible studies. Any disagreements would have been resolved by discussion, or, if necessary, a third review author (DD) would have been consulted. We planned for one review author (FJ) to enter extracted data into Review Manager Software 5.3 (RevMan 2014), and for a second review author (AT) to check for accuracy and consistency against the data extraction sheets. We planned to extract the following data.

Methods: study design, date, total duration of and length of time each participant was part of the study, details of any 'run‐in' period, number of study centres and locations, study setting, date of the study.

Participants: inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria, method of recruitment, number of participants eligible and number randomised, reasons for not including eligible participants, baseline imbalances, and withdrawals and numbers lost to follow‐up in each arm. Participant characteristics: age, sex, duration and severity of condition, race, diagnostic criteria, occupational status.

Intervention(s): details of intervention (name; intervention components, including any materials used by study personnel or given to participants; dose, location, timing, and mode of administration; duration of intervention; providers; scope for and details of modifications during the study).

Comparison (including definition of usual care when appropriate): concomitant medications, excluded medications.

Outcomes: unit of analysis, primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, time points reported, scales used to measure outcomes, person/method of recording outcomes, baseline and end of intervention data for outcomes of interest. Data to assess risk of bias of each study, as required by the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool.

Notes: funding for the study and notable conflicts of interest of study authors; any other study‐specific information of importance not already captured above.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We planned to assess risk of bias of the included studies using Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias, as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, and contained in RevMan 5 (Higgins 2017; RevMan 2014).

Two review authors (AT and FJ) planned to assess risk of bias independently for each study. We planned to resolve any disagreements through consultation with a third review author (DD).

For randomised studies, we planned to base our assessment on the following domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias.

We planned to judge each potential source of bias as having high, low, or unclear risk, and to provide a supporting quotation from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table. We planned to summarise risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. If information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with a study author, we would have noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

For cluster‐randomised studies, we planned to assess these additional sources of bias, as detailed in Section 16.3.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Recruitment bias.

Baseline imbalance.

We planned to judge each additional source of bias as having high, low, or unclear risk, and to provide a supporting quotation from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table.

Dichotomous data

We planned to express results for dichotomous outcome measures using risk ratios (RRs) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to reflect uncertainty of the point estimate of effects.

Continuous data

For continuous outcome measures, we planned to calculate mean differences (MDs) and standard deviations (SDs) with corresponding 95% CIs. We planned to use standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CIs to combine outcomes from trials that measure the same outcome using different scales (Higgins 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

We envisaged that for most studies, we would have been able to extract data from baseline and endpoint details. However, if the study was a cluster‐randomised, cross‐over, or multiple‐arm study, we planned to address unit of analysis issues as detailed below.

Cluster‐randomised studies

We planned on including cluster‐randomised studies in the analyses, along with individually randomised studies. We would have made an adjustment to the sample size in these studies for each intervention based on the method described in Deeks 2017, using an estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the study (when available) or from a similar study, or from a study of a similar population. If we used ICCs from other studies, we planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of variation in ICC values. We planned to include studies with data from more than one time point, selecting data from one clinically important time point for inclusion in a meta‐analysis if appropriate.

Cross‐over studies

We planned to consider only results from the first randomisation period, that is, before the first cross‐over.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

If studies had three (or more) arms testing relevant active interventions versus an inactive control, for continuous outcomes, we planned to pool means, SDs, and number of participants for each active treatment group across treatment arms, or we planned to divide the number of participants in the control group between the treatment arms. For dichotomous outcomes, we planned to pool data from relevant active intervention arms into a single arm for comparison, or we would have divided data from the comparator arm equally between the treatment arms.

Dealing with missing data

For studies with missing data, we planned to contact the corresponding study authors to try to obtain additional information. We planned to record missing and unclear data for each included study. We also aimed to perform all analyses using an intention‐to‐treat approach, that is, we planned to analyse all participants and their outcomes within the groups to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the intervention.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to evaluate heterogeneity by visually inspecting point effect estimates and confidence intervals in forest plots, and by using Tau², the Chi² test, and the I² statistic (Higgins 2003), as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2017). We planned to interpret the I² statistic as follows: 0% to 40% might not be important; 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100% represents considerable heterogeneity. We acknowledge an understanding that the importance of I² depends on (i) magnitude and direction of effect and (ii) strength of evidence for heterogeneity, for example, P value from the Chi² test, or a confidence interval for I².

Assessment of reporting biases

If 10 or more studies were included in the review, we planned to produce a funnel plot to investigate publication bias through visual inspection of asymmetry (Higgins 2011). If asymmetry was evident, we planned to perform a statistical test for funnel plot asymmetry as proposed by Egger and Rücker (Sterne 2017).

Data synthesis

We planned to use RevMan 5 to conduct statistical analysis (RevMan 2014). When reasonable to assume that studies were homogeneous, that is, examining the same intervention in similar populations using the same methods, we planned to use a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis to combine data. If there was clinical heterogeneity (due to variations in participants, interventions, or outcomes), we planned to use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if it were reasonable to assume that an average treatment effect across the included studies was clinically meaningful. If we did not perform a meta‐analysis, instead we had planned to present a narrative synthesis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identified substantial heterogeneity, we planned to explore this using subgroup analyses. We planned to perform the following subgroup analyses on our primary outcomes.

Bipolar disorder type I versus bipolar disorder type II.

Duration of treatment (up to 12 months and longer than 12 months).

Setting (community versus hospital).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to repeat the analyses including high‐quality studies only. For the purpose of this review, we would have classified studies judged as ‘low risk of bias’ for sequence generation and allocation concealment as high‐quality studies.

'Summary of findings' table

For each of the main comparators (detailed under the 'Main comparators' heading), we would have prepared a ‘Summary of findings’ table using GRADEpro GDT 2015 software. We planned to include the three primary outcomes (i.e. changes in body mass as measured by change in BMI, patient‐reported adverse events, and quality of life). Short‐term effects, measured up to 12 months after completion of the intervention, would have been the primary time point reported in the 'Summary of findings' table. We would have graded the quality of evidence according to the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008). We would have assigned one of four levels of quality ‐ high, moderate, low, or very low ‐ based on overall risk of bias of the included studies, directness of the evidence, inconsistency of results, precision of the estimates, and risk of publication bias.

Ensuring relevance to decisions in health care

The principle of assessing healthcare interventions using outcomes that matter to people making choices in health care underpinned our approach to defining the outcomes for this review. We consulted with a consumer group of people living with bipolar disorder on what outcomes matter to this population, and the primary and secondary outcomes of this review reflect their input. We continued to consult with this consumer group throughout the process of carrying out this systematic review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Searches of the CCMDCTR and other databases to 19 February 2019 retrieved 3541 records to screen, and we identified a further 38 duplicates within this set. A total of 3503 records were screened (on title/abstract), 3478 were judged irrelevant, and 25 were carried forward to full‐text review (including three ongoing Clinical Trials.gov protocols). None of the studies reviewed in 2019 met the inclusion criteria.

An update search (22 May 2020) retrieved a further 2684 records (after de‐duplication), and after screening titles and abstracts, we excluded a further 2652 records. We brought 32 studies forward to full‐text review (a majority of these records were ClinicalTrials.gov protocols). Thirteen studies were carried forward, six are additional ongoing studies, and six are studies that have been completed but remain unpublished. A further study was excluded once the drug company report had been retrieved. A cumulative summary of the results from both searches is displayed in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

There are no included studies in this review.

Excluded studies

To date, we have not identified any completed and published studies that meet our eligibility criteria. We have formally excluded 23 studies (Alvarez‐JimÈnez 2006; Baptista 2007; Bartels 2015; Bobo 2011; Dauphinais 2011; Deberdt 2005; Deberdt 2008; Elmslie 2006; Erickson 2016; Evans 2005; Frank 2015; Gillhoff 2010; Goldberg 2013; Graham 2005; Kim 2014; Mc Elroy 2007; Milano 2007; Mostafavi 2017; NCT00044187; NCT00303602; NCT00472641; NCT00845507;Rado 2016). All excluded studies and reasons for exclusion are presented in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Ongoing studies

We identified a total of nine ongoing studies: three studies from the initial search in 2019 (NCT02515773;NCT02815813;NCT03158805), and six from the 2020 update (Daumit 2019;NCT03382782;NCT03541031;NCT03695289;NCT03980743;NCT04272541. Details are provided in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

Studies awaiting classification

The update search in May 2020 identified an earlier conference abstract (Wirshing 2009), together with five completed but unpublished trial protocols (ChiCTR‐IPR‐17013122; NCT00203450; NCT01828931; NCT02130596; NCT03743844). Details are provided in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table.

Risk of bias in included studies

It was not possible to assess the risk of bias due to the absence of eligible studies for inclusion.

Effects of interventions

Due to lack of published and unpublished studies eligible for inclusion, it was not possible to examine the effectiveness of interventions for the management of obesity in people with bipolar disorder.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The objective of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for the management of obesity in people with bipolar disorder, but we found no published or unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCTs) addressing the objective of this review. However, we did find several ongoing studies that could potentially meet the inclusion criteria for this review and may be included in the updated review. For now, we cannot draw any conclusions regarding management strategies for obesity in bipolar disorder. It is evident that there is a need to undertake high‐quality RCTs to examine different approaches. The focus must be on a bipolar population only, with a clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder and comorbid obesity. Interventions and outcomes should be clearly defined.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We were unable to assess completeness and applicability of studies, as we found no studies that meet the inclusion criteria of this review.

Quality of the evidence

It was not possible to assess methodological quality or quality of evidence in the absence of studies eligible for inclusion.

Potential biases in the review process

We found no studies relevant for inclusion in this review. By establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria from the outset and performing an extensive literature search, we reduced the risk of bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Establishing agreement or disagreement with other evidence sources is not possible or beneficial in this instance because, to our knowledge, and indeed from our experience of undertaking this review, other reviews or studies in this area of research or evidence synthesis have not focused only on evaluating the effectiveness of interventions for the management of obesity in people with bipolar disorder. Most of the studies in this review were excluded because of "wrong population". Much to our disappointment, none of the studies that we reviewed focused exclusively on a bipolar population with a clinical diagnosis of obesity. Populations were mixed in terms of types of serious mental illness (SMI), and there was no differentiation between overweight and obesity in many of the studies we reviewed. Given our recommendations for research stemming from the findings of this review, we are hopeful that future updates of this review will allow us to make meaningful comparisons across studies and indeed other reviews.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found no evidence to inform decisions on the best way to manage obesity in people with bipolar disorder. In the absence of a rigorous evidence base, it remains difficult for clinicians and patients to address this very serious problem that impacts negatively the health and well‐being of all affected individuals and their families. For now, management of obesity in people with bipolar disorder continues to pose a challenge.

Implications for research.

There is an urgent need to undertake high‐quality RCTs to assess the effectiveness of interventions used in the management of obesity in people with bipolar disorder. The focus needs to be on a bipolar population only. Both bipolar disorder and comorbid obesity should be clinically diagnosed. Interventions and outcome measures should be clearly defined to facilitate meaningful synthesis of data across studies.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2018 Review first published: Issue 7, 2020

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group for the guidance and support they provided during preparation of this review.

The review authors and the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Editorial Team are also grateful to the following peer reviewers for their time and comments: Joseph F Hayes, Joseph Firth, and Sue Rees. They would also like to thank our copy editor, Dolores Matthews.

CRG Funding Acknowledgement: the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group.

Disclaimer: the views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the UK National Health Service, the NIHR, or the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CCMDCTR core MEDLINE search

CCMD’s core search strategy used to inform the Group’s Specialised Register: Ovid MEDLINE

A search alert based on condition + RCT filter only 1. [MeSH Headings]: eating disorders/ or anorexia nervosa/ or binge‐eating disorder/ or bulimia nervosa/ or female athlete triad syndrome/ or pica/ or hyperphagia/ or bulimia/ or self‐injurious behavior/ or self mutilation/ or suicide/ or suicidal ideation/ or suicide, attempted/ or mood disorders/ or affective disorders, psychotic/ or bipolar disorder/ or cyclothymic disorder/ or depressive disorder/ or depression, postpartum/ or depressive disorder, major/ or depressive disorder, treatment‐resistant/ or dysthymic disorder/ or seasonal affective disorder/ or neurotic disorders/ or depression/ or adjustment disorders/ or exp antidepressive agents/ or anxiety disorders/ or agoraphobia/ or neurocirculatory asthenia/ or obsessive‐compulsive disorder/ or obsessive hoarding/ or panic disorder/ or phobic disorders/ or stress disorders, traumatic/ or combat disorders/ or stress disorders, post‐traumatic/ or stress disorders, traumatic, acute/ or anxiety/ or anxiety, castration/ or koro/ or anxiety, separation/ or panic/ or exp anti‐anxiety agents/ or somatoform disorders/ or body dysmorphic disorders/ or conversion disorder/ or hypochondriasis/ or neurasthenia/ or hysteria/ or munchausen syndrome by proxy/ or munchausen syndrome/ or fatigue syndrome, chronic/ or obsessive behavior/ or compulsive behavior/ or behavior, addictive/ or impulse control disorders/ or firesetting behavior/ or gambling/ or trichotillomania/ or stress, psychological/ or burnout, professional/ or sexual dysfunctions, psychological/ or vaginismus/ or Anhedonia/ or Affective Symptoms/ or *Mental Disorders/

2. [Title/ Author Keywords]: (eating disorder* or anorexia nervosa or bulimi* or binge eat* or (self adj (injur* or mutilat*)) or suicide* or suicidal or parasuicid* or mood disorder* or affective disorder* or bipolar i or bipolar ii or (bipolar and (affective or disorder*)) or mania or manic or cyclothymic* or depression or depressive or dysthymi* or neurotic or neurosis or adjustment disorder* or antidepress* or anxiety disorder* or agoraphobia or obsess* or compulsi* or panic or phobi* or ptsd or posttrauma* or post trauma* or combat or somatoform or somati#ation or medical* unexplained or body dysmorphi* or conversion disorder or hypochondria* or neurastheni* or hysteria or munchausen or chronic fatigue* or gambling or trichotillomania or vaginismus or anhedoni* or affective symptoms or mental disorder* or mental health).ti,kf.

3. [RCT filter]: (controlled clinical trial.pt. or randomized controlled trial.pt. or (randomi#ed or randomi#ation).ab,ti. or randomly.ab. or (random* adj3 (administ* or allocat* or assign* or class* or control* or determine* or divide* or distribut* or expose* or fashion or number* or place* or recruit* or subsitut* or treat*)).ab. or placebo*.ab,ti. or drug therapy.fs. or trial.ab,ti. or groups.ab. or (control* adj3 (trial* or study or studies)).ab,ti. or ((singl* or doubl* or tripl* or trebl*) adj3 (blind* or mask* or dummy*)).mp. or clinical trial, phase ii/ or clinical trial, phase iii/ or clinical trial, phase iv/ or randomized controlled trial/ or pragmatic clinical trial/ or (quasi adj (experimental or random*)).ti,ab. or ((waitlist* or wait* list* or treatment as usual or TAU) adj3 (control or group)).ab.)

4. (1 and 2 and 3)

Records are screened for reports of RCTs within the scope of the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group. Secondary reports of RCTs are tagged to the appropriate study record.

Similar search alerts are also conducted on Ovid EMBASE and PsycINFO, using relevant subject headings (controlled vocabularies) and search syntax, appropriate to each resource.

Appendix 2. Other database search strategies (February 2019)

Searches were conducted on the following databases to 19 February 2019.

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR)

CCMDCTR ‐ Studies Register ((bipolar) and (obes* or BMI):stc,sco.

CCMDCTR‐References Register #1 (bipolar or cyclothymi* or “rapid cycling” or psychos* or *psychotic* or *mani* or schizoaffective):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh #2 (*weight* or obes* or “body mass” or BMI or fatness or diet or metabol*): :ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh #3 (#1 and #2). (Key to search fields: ti: title; ab: abstract; kw: keywords; ky: additional keywords; emt: EMTREE headings; mh: MeSH headings; stc: target condition; sco: healthcare condition.)

[N.B. The CCMDCTR is up‐to‐date as of June 2016 only]

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), in the Cochrane Library (2019; Issue 2 of 12)

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Bipolar Disorder] explode all trees

#2 (Bipolar or cyclothymi*):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#3 ((Mani* or major) and (depres* or disorder*)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#4 #1 or #2 or #3

#5 MeSH descriptor: [Obesity] explode all trees

#6 Obes*:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#7 MeSH descriptor: [Body Mass Index] this term only

#8 (body mass or BMI):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#9 #5 or #6 or #7 or #8

#10 #4 and #9

Ovid MEDLINE databases (1946 to 19 February 2019)

1 Bipolar Disorder/ 2 (Bipolar or cyclothymi*).ti,ab,kw,ot. 3 ((Mani$ or major) and (depres$ or disorder$)).ti,ab,kw. 4 or/1‐3 5 exp Obesity/ 6 Obes$.ti,ab,kw,ot. 7 *Overweight 8 *body mass index/ 9 (body mass or BMI).ti,ab,kw,ot. 10 or/5‐9 11 randomized controlled trial.pt. 12 controlled clinical trial.pt. 13 (randomized or randomised).ab. 14 placebo.ab. 15 clinical trials as topic.sh. 16 randomly.ab. 17 trial.ti. 18 or/11‐17 19 (4 and 10 and 8) 20 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 21 (19 not 20)

Ovid Embase (1974 to 19 February 2019)

1 exp bipolar disorder/ 2 (Bipolar or cyclothymi*).ti,ab. 3 ((Mani$ or major) and (depres$ or disorder$)).ti,ab. 4 or/1‐3 5 exp Obesity/ 6 Obes$.ti,ab. 7 *body mass/ 8 (body mass or BMI).ti,ab. 9 or/5‐8 10 randomized controlled trial/ 11 (random$ or placebo$ or (double adj1 blind$)).ti,ab. 12 (10 or 11) 13 (4 and 9 and 12)

Ovid PsycINFO (1806 to 19 February 2019)

1 bipolar disorder/ 2 (Bipolar or cyclothymi*).ti,ab. 3 ((Mani$ or major) and (depres$ or disorder$)).ti,ab. 4 or/1‐3 5 exp Obesity/ 6 obes*.ti,ab. 7 exp Overweight/ 8 exp Body Mass Index 9 (body mass or BMI).ti,ab. 10 or/5‐9 11 (4 and 10) 12 random$.ti,ab. or Dissertation Abstract.pt 13 (11 and 12)

ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ Searched on: 12th February 2019 Search terms: Bipolar and obesity Bipolar and BMI British Library Electronic Theses Online Service (EThOS) Searched on: 12th February 2019 Search terms: Bipolar and obesity Bipolar and BMI

Appendix 3. Update search (May 2020)

Update 22 May 2020 Ovid MEDLINE (new search) (1946 to May 22, 2020), n=766 Ovid Embase (new search) (1974 to 2020 Week 21), n=1849 Ovid PsycINFO (new search) (1806 to May Week 3 2020), n=878 CLib:CENTRAL (new search) (Issue 5 of 12, 2020), n=1179 Total=4672

Duplicates removed (within this set, and against all other search results), n=1988 Additional records to screen, n=2684 Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and Daily <1946 to May 22, 2020> Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp Bipolar Disorder/ (40017) 2 (bipolar or mania* or manic* or hypomani* or rapid cycling or schizoaffective).tw,kf. (78584) 3 cyclothymi*.hw,tw,kf. (1312) 4 or/1‐3 (88769) 5 body mass index/ (125399) 6 exp Obesity/ (210472) 7 weight gain/ or weight loss/ (65224) 8 body weight maintenance/ or weight reduction programs/ or obesity management/ (2471) 9 (body mass or BMI or body weight or (weight adj2 (gain* or loss)) or overweight or (weight adj3 (control or manag* or maint*)) or obesity or obese).tw,kw. (735492) 10 or/5‐9 (799885) 11 4 and 10 (2696) 12 controlled clinical trial.pt. (93684) 13 randomized controlled trial.pt. (506126) 14 clinical trials as topic/ (191286) 15 (randomi#ed or randomi#ation or randomi#ing).ti,ab,kf. (633768) 16 (RCT or "at random" or (random* adj3 (administ* or allocat* or assign* or class* or cluster or crossover or cross‐over or control* or determine* or divide* or division or distribut* or expose* or fashion or number* or place* or pragmatic or quasi or recruit* or split or subsitut* or treat*))).ti,ab,kf. (557218) 17 placebo.ab,ti,kf. (213771) 18 trial.ti. (218599) 19 (control* adj3 group*).ab. (533257) 20 (control* and (trial or study or group*) and (waitlist* or wait* list* or ((treatment or care) adj2 usual))).ti,ab,kf,hw. (24921) 21 ((single or double or triple or treble) adj2 (blind* or mask* or dummy)).ti,ab,kf. (172888) 22 double‐blind method/ or random allocation/ or single‐blind method/ (277851) 23 or/12‐22 (1714903) 24 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (4700877) 25 23 not 24 (1485540) 26 11 and 25 (766) *************************** Database: Embase <1974 to 2020 Week 21> Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 bipolar disorder/ or bipolar depression/ or bipolar i disorder/ or bipolar ii disorder/ or bipolar mania/ or cyclothymia/ or "mixed mania and depression"/ or rapid cycling bipolar disorder/ (62371) 2 mania/ or hypomania/ or manic psychosis/ (20595) 3 (bipolar or mania* or manic* or hypomani* or rapid cycling or schizoaffective).tw,kw. (111033) 4 cyclothymi*.tw,kw. (1266) 5 or/1‐4 (131674) 6 exp OBESITY/ (510888) 7 weight gain/ or weight loss/ (107653) 8 body weight gain/ or body weight loss/ or body weight control/ (48913) 9 body weight management/ or body weight maintenance/ or obesity management/ or weight loss program/ (4465) 10 body weight disorder/si [Side Effect] (3648) 11 (body mass or BMI or body weight or (weight adj2 (gain* or loss)) or overweight or (weight adj3 (control or manag* or maint*)) or obesity or obese).tw,kw. (1106546) 12 or/6‐11 (1260568) 13 5 and 12 (7805) 14 randomized controlled trial/ (602638) 15 randomization.de. (86688) 16 placebo.de. (349813) 17 placebo.ti,ab. (305287) 18 trial.ti. (298726) 19 (randomi#ed or randomi#ation or randomi#ing).ti,ab,kw. (909705) 20 (RCT or "at random" or (random* adj3 (administ* or allocat* or assign* or class* or cluster or control* or crossover or cross‐over or determine* or divide* or division or distribut* or expose* or fashion or number* or place* or pragmatic or quasi or recruit* or split or subsitut* or treat*))).ti,ab,kw. (762537) 21 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or mask$ or dummy)).mp. (307247) 22 (control* and (study or group?) and (waitlist* or wait* list* or ((treatment or care) adj2 usual))).ti,ab,kw,hw. (39036) 23 or/14‐22 (1652212) 24 ((animal or nonhuman) not (human and (animal or nonhuman))).de. (5665207) 25 23 not 24 (1496717) 26 13 and 25 (2080) 27 (schizophreni* not bipolar).ti. (91109) 28 26 not 27 (1849)

*************************** Database: APA PsycInfo <1806 to May Week 3 2020> Search Strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp bipolar disorder/ (30294) 2 mania/ or hypomania/ (6187) 3 schizoaffective disorder/ (3088) 4 exp Neuroleptic Drugs/ (31052) 5 (bipolar or mania* or manic* or hypomani* or rapid cycling or cyclothymi* or schizoaffective or antipsychotic*).ti,ab,id. (81598) 6 or/1‐5 (92641) 7 exp obesity/ (24243) 8 exp body size/ (58368) 9 overweight/ or body weight/ or body fat/ (17836) 10 weight gain/ or weight loss/ or weight control/ (10296) 11 body mass index/ (5692) 12 (weight* or diet or metabol*).ti,id. (54531) 13 (body mass or BMI or body weight or (weight adj2 (gain* or loss)) or overweight or (weight adj3 (control or manag* or maint*)) or obesity or obese).tw,id,hw. (85027) 14 or/7‐13 (125304) 15 dissertation abstract.pt. (494703) 16 6 and 14 and 15 (53) 17 clinical trials/ (11667) 18 (randomi#ed or randomi#ation or randomi#ing).ti,ab,id. (85846) 19 (RCT or at random or (random* adj3 (administ* or allocat* or assign* or class* or control* or crossover or cross‐over or determine* or divide* or division or distribut* or expose* or fashion or number* or place* or recruit* or split or subsitut* or treat*))).ti,ab,id. (102074) 20 (control* and (trial or study or group) and (placebo or waitlist* or wait* list* or ((treatment or care) adj2 usual))).ti,ab,id,hw. (29049) 21 ((single or double or triple or treble) adj2 (blind* or mask* or dummy)).ti,ab,id. (26151) 22 trial.ti. (30288) 23 placebo.ti,ab,id,hw. (40115) 24 treatment effectiveness evaluation.sh. (24281) 25 or/17‐24 (185914) 26 (bipolar or mania* or manic* or hypomani* or rapid cycling or cyclothymi* or schizoaffective).ti,ab,id. (56649) 27 (psychosis or psychotic or ((severe or serious) adj mental) or antipsyc*).ti,id. (59836) 28 exp *Neuroleptic Drugs/ (27267) 29 1 or 2 or 3 or 26 or 27 or 28 (120603) 30 14 and 25 and 29 (1247) 31 16 or 30 (1296) 32 (schizophreni* not bipolar).ti. (66696) 33 31 not 32 (878) *************************** The Cochrane Library (2020; Issue 5 of 12) #1 MeSH descriptor: [Bipolar and Related Disorders] explode all trees2637 #2 (bipolar or mania* or manic* or hypomani* or "rapid cycling" or cyclothymi* or schizoaffective):ti,ab,kw10668 #3 (#1 or #2) 10668 #4 ("body mass" or BMI or "body weight" or (weight near/2 gain*) or "weight loss" or overweight or (weight NEAR (control or manag* or maint* or reduc*)) or obesity or obese):ti,ab,kw123287 #5 (#3 and #4) 1011 #6 (psychosis or psychotic or "severe mental" or "serious mental" or antipsyc* or anti‐psyc*):ti5741 #7 (#4 and #6) 672 #8 (#5 or #7) 1525 #9 (schizophren* not bipolar):ti11196 #10 (#8 not #9) 1200 Limit to CENTRAL, n=1179

***************************

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Alvarez‐JimÈnez 2006 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Baptista 2007 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Bartels 2015 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Bobo 2011 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Dauphinais 2011 | Wrong population ‐ population not obese |

| Deberdt 2005 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Deberdt 2008 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Elmslie 2006 | Wrong population ‐ not all patients obese at baseline |

| Erickson 2016 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Evans 2005 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Frank 2015 | Wrong population ‐ not obese |

| Gillhoff 2010 | Wrong population ‐ not all participants obese at baseline |

| Goldberg 2013 | Wrong population ‐ not all participants obese at baseline |

| Graham 2005 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Kim 2014 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Mc Elroy 2007 | Wrong population ‐ not all patients obese at baseline |

| Milano 2007 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Mostafavi 2017 | Wrong population ‐ not obese at baseline |

| NCT00044187 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| NCT00303602 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| NCT00472641 | Wrong study design |

| NCT00845507 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

| Rado 2016 | Wrong population ‐ mixed SMI population |

SMI: serious mental illness.

Characteristics of studies awaiting classification [ordered by study ID]

ChiCTR‐IPR‐17013122.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Obese; have a history of mental illness and on anti‐psychotic medication |

| Interventions | Topiramate or metformin |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: body weight; height; waist circumference; hip circumference Secondary outcomes: liver function; blood routine; electrocardiogram; fasting blood glucose |

| Notes | No results available |

NCT00203450.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Individuals who have a body mass index (BMI) > 25 and are on a psychotropic medication with a known side effect of weight gain |

| Interventions |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: comparison of the efficacy of zonisamide (Zonegran; 100 mg to 400 mg/d) vs placebo as an adjunctive agent for lowering weight |

| Notes | No results available |

NCT01828931.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Overweight adults with serious mental illness and comorbid type 2 diabetes |

| Interventions | A lifestyle intervention (LI) aimed at reducing caloric intake and increasing physical activity vs treatment as usual |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: weight (time frame: 52 weeks) |

| Notes | No results available |

NCT02130596.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Overwight adults with a history of serious mental illness |

| Interventions | An acceptance‐based behavioural intervention vs nutritional counselling for weight loss in psychotic illness |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: weight (kg) (time frame: 12 weeks) |

| Notes | No results available |

NCT03743844.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Overweight female adults with a history of major depressive or bipolar disorder |

| Interventions | A compassion‐focused psycho‐educational group vs group receiving weight management treatment as usual |

| Outcomes | Changes in weight bias |

| Notes | No results available |

Wirshing 2009.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Individuals with serious mental illness, obese, and on anti‐psychotic medication |

| Interventions | Psycho‐educational programme vs usual psychiatric treatment |

| Outcomes | Participants' metabolic profiles, cardiovascular risk factor status, mental health |

| Notes | No results available |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Daumit 2019.

| Study name | Trial of Integrated Smoking Cessation, Exercise, and Weight Management in Serious Mental Illness: TRIUMPH |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Smokers with a history of serious mental illness attending community mental health services and interested in quitting smoking |

| Interventions | An 18‐month comprehensive, practical tobacco smoking cessation programme integrating exercise and weight counselling vs treatment as usual |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: prolonged smoking abstinence, physical fitness, weight maintenance |

| Starting date | July 2016 |

| Contact information | Gail L Daumit, MD, MHS Johns Hopkins University |

| Notes |

NCT02515773.

| Study name | Metformin for Overweight and OBese ChILdren and Adolescents With BDS Treated With SGAs (MOBILITY) |

| Methods | A prospective, large, pragmatic, randomised trial. Open‐label. Parallel assignment |

| Participants | Children and adolescents from 8 to 17 years of age. Diagnosed or told by a clinician that they have any of the following bipolar spectrum disorders (BSDs): bipolar I, bipolar II, unspecified bipolar, and related disorders, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), cyclothymic disorder, other specified bipolar and related disorders, as well as mood disorder not otherwise specified (if diagnosed in the past as per DSM‐IV and body mass index > 85 percentile for age and sex by standard growth charts |

| Interventions | Two experimental arms: 1. MET and LIFE: participants randomised to this group will receive both metformin and lifestyle intervention. Participants randomised to treatment with MET will start at a dose of 500 mg orally at night and slowly titrated at 2‐week intervals to ensure that each patient achieves maximum insulin‐sensitising effects of the drug while minimising the chance of side effects; 2. Healthy lifestyle intervention (LIFE): participants randomised to this group will receive lifestyle intervention alone. This healthy lifestyle intervention (LIFE) consists of counselling participants and families regarding a healthy eating plan, physical activity, and sedentary activities |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: BMI z‐score Secondary outcome: composite metabolic health and nutrition measure |

| Starting date | December 2015 |

| Contact information | Melissa Delbello, Principal Investigator University of Cincinnati |

| Notes |

NCT02815813.

| Study name | Lifestyle Intervention for Young Adults With Serious Mental Illness |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Overweight and obese (BMI ≥ 25) young adults ages 18 to 35 with SMI, attending 1 of 2 community mental health centres who are interested in losing weight and improving fitness |

| Interventions | A 12‐month PeerFIT intervention vs basic education in fitness and nutrition supported by a wearable activity tracking device (BEAT) in achieving clinically significant improvements in weight loss and cardiorespiratory fitness |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcomes: 1. Change in weight (time frame: baseline, 6 months, and 12 months). Participants' weight will be measured in pounds (lbs) on a flat, even surface with the use of a high‐quality, calibrated professional medical scale, with the participant wearing indoor clothing and no shoes 2. Change in 6‐minute walk test (time frame: baseline, 6 months, and 12 months). After a baseline blood pressure has been obtained, participants are asked to walk a measured distance as far as they are able in 6 minutes Secondary outcomes: 1. Change in weight loss self‐efficacy assessed by the Weight Efficacy Lifestyle (WEL) questionnaire (time frame: baseline, 6 months, and 12 months). The Weight Efficacy Lifestyle (WEL) questionnaire will be used to measure self‐efficacy for weight loss. The WEL consists of 20 items designed to measure self‐confidence to control weight by resisting overeating in certain tempting situations. The total score will be used in analyses. Items are scored on a 10‐point Likert scale from 0 ("not confident") to 10 ("very confident") and total score calculated as the sum of individual item responses 2. Change in self‐efficacy for exercise behaviours assessed by the Self‐efficacy for Exercise Behaviors (SEB) scale (time frame: baseline, 6 months, and 12 months). The SEB scale will be used to measure participants' self‐efficacy related to the ability to exercise despite barriers. The 12‐item scale consists of common barriers that might affect participation in exercise (e.g. feeling depressed, socialising, stressful life changes, household chores). For each situation, participants use the scale from 1 ("I know I cannot") to 5 ("I know I can") to describe their confidence that they could exercise in the face of these barriers 3. Change in peer support for health behaviour change assessed by the 24‐item Social Provisions Scale (SPS) (time frame: baseline, 6 months, and 12 months). Participants' level of perceived peer support will be measured by the 24‐item SPS. The SPS assesses 6 types of support from social relationships (guidance, reliable alliance, reassurance of worth, attachment, social integration, and opportunity for nurturance), and the total score will be used in the analysis. Items are scored on a 4‐point Likert scale from 1 ("strongly disagree) to 4 ("strongly agree") as it pertains to relationships with group members. Higher scores indicate greater perceived support from group relationships 4. Change in serum lipids (time frame: baseline, 6 months, and 12 months). Lipids will be measured by the CardioChek PA Analyzer, a hand‐held dual testing system that produces values for total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides via a multi‐panel test strip and a single drop of blood acquired with a finger prick |

| Starting date | July 2017 |

| Contact information | Principal Investigator: Kelly A Aschbrenner, PhD Dartmouth‐Hitchcock and Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College |

| Notes |

NCT03158805.

| Study name | Saxenda® in Obese or Overweight Patients With Stable Bipolar Disorder |

| Methods | A Randomised, Placebo‐Controlled Study of Liraglutide 3 mg Daily (Saxenda®) |

| Participants | Obese or overweight patients with stable bipolar disorder. Participants will have a DSM‐5 bipolar disorder that is clinically stable and will be obese (defined as BMI ≥ 30 mg/kg²) or overweight (defined as BMI ≥ 27 kg/m²) with at least 1 weight‐related comorbidity, such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia |

| Interventions | Liraglutide 3 mg daily (Saxenda®) vs placebo |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: percent change in body weight over 2 years |

| Starting date | April 2017 |

| Contact information | Susan McElroy, Chief Research Officer Lindner Center of HOPE |

| Notes |

NCT03382782.

| Study name | Peer Navigators to Address Obesity‐Related Concerns for African Americans With Serious Mental Illness |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Obese with a history of mental illness |

| Interventions | "The behavioral weight loss intervention (BWLI) consists of an 8‐month intervention phase followed by a 4‐month maintenance phase. The initial intervention phase comprises four types of contact: (1) one‐hour to one and a half hour group weight management class led by facilitator (once per week); (2) 45‐minute physical activity class led by facilitator (1‐2 per week); (3) 20‐minute, individual visit with facilitator (once per month); (4) weigh‐in (once each week). Persons are randomly assigned to peer navigators to begin simultaneously with BWLI and run concurrently across the eight months of the intervention. PNs may work with participants to partner on BWLI homework, meet with participant and BWLI facilitator individually, attend healthcare appointments, and partner on tasks that arise out of those appointments" |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes:

|

| Starting date | December 2017 |

| Contact information | Patrick Corrigan, Distinguished Professor of Psychology Illinois Institute of Technology |

| Notes |

NCT03541031.

| Study name | Micronutrients as Adjunctive Treatment for Bipolar Disorder |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Stable adult outpatients with bipolar disorder, type I or II (DSM‐V criteria) |

| Interventions | Supplementation with a 36‐ingredient vitamin/mineral mix (Micronutrient) and an omega‐3 fatty acid supplement (fish oil) vs matched double placebo in a 3:2 ratio for a year |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: Composite z‐score for side effects, calculated from 3 separate z‐scores that measure medication dosage, illness intensity (Clinical Global Impression score), and adverse side effects (UKU Side Effect score) Secondary outcomes:

|

| Starting date | May 2018 |

| Contact information | Principal Investigator: Lewis Mehl‐Madrona, MD, PhD Eastern Maine Medical Center |

| Notes |

NCT03695289.

| Study name | Interactive Obesity Treatment Approach (iOTA) for Obesity Prevention in Serious Mental Illness (iOTA‐SMI) |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Obese adults with a history of serious mental illness |

| Interventions |

Behavioural: iOTA SMI: Participants randomised to the iOTA SMI arm will undergo an assessment of individual behaviour risks, will participate in collaborative goal‐setting with a health coach, and will use an interactive text system that will provide ongoing support and self‐monitoring of behaviour change goals Behavioural: health education control: Participants randomised to the Health Education Control arm will receive monthly counselling on energy balance, physical activity, and nutrition |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: change in BMI |

| Starting date | July 2018 |

| Contact information | Principal Investigator: Ginger E Nicol, MD Washington University of Medicine |

| Notes |

NCT03980743.

| Study name | Interactive Obesity Treatment Approach (iOTA) for Obesity Prevention in Adults With Early Serious Mental Illness: iOTA‐SMI (iOTA‐eSMI) |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Overweight or obese adults with a history of serious mental illness |

| Interventions |