Abstract

Background

This is an updated version of the Cochrane Review first published in 2014, and last updated in 2018.

For nearly 30% of people with epilepsy, seizures are not controlled by current treatments. Stiripentol is an antiepileptic drug (AED) that was developed in France and was approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2007 for the treatment of Dravet syndrome as an adjunctive therapy with valproate and clobazam.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of stiripentol as add‐on treatment for people with drug‐resistant focal epilepsy who are taking AEDs.

Search methods

For the latest update, we searched the following databases on 27 February 2020: Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS Web); and MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 26 February 2020). CRS Web includes randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials from the Specialized Registers of Cochrane Review Groups including Epilepsy, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed, Embase, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). We contacted Biocodex (the manufacturer of stiripentol) and epilepsy experts to identify published, unpublished and ongoing trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised, controlled, add‐on trials of stiripentol in people with drug‐resistant focal epilepsy.

Data collection and analysis

Review authors independently selected trials for inclusion and extracted data. We investigated outcomes including 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency, seizure freedom, adverse effects, treatment withdrawal and changes in quality of life.

Main results

On the basis of our selection criteria, we included no new studies in the present review update. We included only one study from the earlier review (32 children with focal epilepsy). This study adopted a responder‐enriched design and found no clear evidence of a reduction in seizure frequency (≥ 50% seizure reduction) (risk ratio (RR) 1.51, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 2.82; low‐certainty evidence) or evidence of seizure freedom (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.31 to 4.43; low‐certainty evidence) when add‐on stiripentol was compared with placebo.

Stiripentol led to a greater risk of adverse effects considered as a whole (RR 2.65, 95% CI 1.08 to 6.47; low‐certainty evidence). When we considered specific adverse events, confidence intervals were very wide and showed the possibility of substantial increases and small reductions in risks of neurological adverse effects (RR 2.65, 95% CI 0.88 to 8.01; low‐certainty evidence) and gastrointestinal adverse effects (RR 11.56, 95% CI 0.71 to 189.36; low‐certainty evidence). Researchers noted no clear reduction in the risk of study withdrawal (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.47; low‐certainty evidence), which was high in both groups (35.0% in add‐on placebo and 53.3% in stiripentol group; low‐certainty evidence).

The external validity of this study was limited because only responders to stiripentol (i.e. patients experiencing a ≥ 50% decrease in seizure frequency compared with baseline) were included in the randomised, add‐on, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind phase. Furthermore, carry‐over and withdrawal effects probably influenced outcomes related to seizure frequency. Very limited information derived from the only included study shows that adverse effects considered as a whole seemed to occur significantly more often with add‐on stiripentol than with add‐on placebo.

Authors' conclusions

We have found no new studies since the last version of this review was published. Hence, we have made no changes to the conclusions of this update as presented in the initial review. We can draw no conclusions to support the use of stiripentol as add‐on treatment for drug‐resistant focal epilepsy. Additional large, randomised, well‐conducted trials are needed.

Plain language summary

Stiripentol as an add‐on treatment for drug‐resistant focal epilepsy

Background

Epilepsy is one of the more common chronic neurological disorders; it affects 1% of the population worldwide. A large proportion of these people (up to 30%) continue to have seizures despite adequate therapy with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), used singularly (as monotherapy) or in combination (polytherapy). These individuals are regarded as having drug‐resistant epilepsy. Stiripentol is an AED that was developed in France and was approved in 2007 by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as add‐on therapy with valproate and clobazam for the treatment of Dravet syndrome (a rare, drug‐resistant epilepsy that begins in the first year of life in an otherwise healthy infant). This review appraises evidence for the use of stiripentol as add‐on treatment for drug‐resistant focal epilepsy in individuals taking AEDs.

Results

On the basis of our review criteria, we included only one study in the review (32 children with focal epilepsy). This study adopted a responder‐enriched design and found no clear evidence of seizure reduction (≥ 50%) nor of seizure freedom with add‐on stiripentol compared with placebo. Add‐on stiripentol led to greater risk of adverse effects considered as a whole (risk ratio (RR) 2.65, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.08 to 6.47) compared with placebo. Generalisation of study results to a more widespread population is limited by the fact that only responders to stiripentol (i.e. patients experiencing a decrease in seizure frequency of at least 50% compared with baseline) were included in the randomised, add‐on, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind portion of the study. Also, the very small sample size with the correspondingly high dropout rate prevents generalisation of study results. Finally, because of the adopted design, carry‐over and withdrawal effects probably influenced outcomes related to seizure frequency.

Certainty of the evidence

We judged the included study to be at low to unclear risk of bias. Using GRADE methodology, we rated the certainty of the evidence as low.

Currently, no available evidence supports the use of stiripentol as add‐on treatment for drug‐resistant focal epilepsy. Large, randomised, well‐conducted trials on this topic are needed.

The evidence is current to February 2020.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Stiripentol compared with placebo for drug‐resistant focal epilepsy.

| Stiripentol compared with placebo for drug‐resistant focal epilepsy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with drug‐resistant focal epilepsy Settings: community Intervention: stiripentol Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes* | Illustrative comparative risks** (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Stiripentol | |||||

| ≥ 50% seizure reduction | 467 per 1000 | 705 per 1000 (378 to 1000) | RR 1.51 (0.81 to 2.82) | 32 (1) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ lowa,b |

|

| Seizure freedom | 200 per 1000 | 236 per 1000 (62 to 886) | RR 1.18 (0.31 to 4.43) | 32 (1) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ lowa,b |

|

| ≥ 1 adverse effect | 267 per 1000 | 707 per 1000 (288 to 1000) | RR 2.65 (1.08 to 6.47) | 32 (1) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ lowa,b | |

| Neurological adverse effects | 200 per 1000 | 530 per 1000 (176 to 1000) | RR 2.65 (0.88 to 8.01) | 32 (1) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ lowa,b | |

| Gastrointestinal adverse effects | 0 events occurred in the placebo group | 0 events occurred in the stiripentol group (0 to 0) | RR 11.56 (0.71 to 189.36) | 32 (1) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ lowa,b | |

| Dropouts | 533 per 1000 | 352 per 1000 (160 to 784) | RR 0.66 (0.30 to 1.47) | 32 (1) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ lowa,b | |

| * Quality of life was not assessed in this study. **The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) and is calculated according to the following formula: corresponding intervention risk, per 1000 = 1000 × ACR × RR. ACR: assumed control risk; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainy: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded once for risk of bias and once for imprecision (small sample size which is made even smaller with dropouts). bInformation is from only 1 small paediatric study. The main issues with this study are imprecision (small sample size which is made even smaller with dropouts) and applicability (due to the high risk of carry‐over effect).

Background

This is an updated version of the Cochrane Review first published in 2014 (Brigo 2014), and last updated in 2018 (Brigo 2018)

Description of the condition

Epilepsy is one of the more common chronic neurological disorders; it affects 1% of the population worldwide.

A large proportion of these people (up to 30%) continue to have seizures despite adequate therapy with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), used singularly or in combination (Cockerell 1995; Granata 2009). These individuals are regarded as having drug‐resistant epilepsy. Although there is no universal definition of drug‐resistant epilepsy, most definitions refer to continued seizures despite AED treatment, and the definition most often used encompasses continued seizures despite frequent medication changes (French 2006).

Various criteria have been used to define drug‐resistant epilepsy. In 2010, an internationally accepted definition of drug‐resistant epilepsy was proposed by a Task Force of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) as "failure of adequate trials of two tolerated, appropriately chosen and used AED schedules (whether given as monotherapy or in combination) to achieve sustained seizure freedom" (Kwan 2010). Standard drugs (e.g. carbamazepine, phenytoin, valproate) do not control all patients’ seizures. Over the past 15 to 20 years, however, numerous newly available AEDs have offered promise for the treatment of drug‐resistant epilepsy.

Seizures may occur within (and may rapidly engage) bilaterally distributed networks (generalised seizures) or networks limited to one hemisphere and are discretely localised or more widely distributed (focal seizures) (Berg 2010).

In this review, we aimed to investigate the efficacy and tolerability of add‐on stiripentol in people with focal drug‐resistant epilepsy.

Description of the intervention

Stiripentol is an AED that was developed in France and approved in 2007 by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of Dravet syndrome as adjunctive therapy with valproate and clobazam (Chiron 2007).

The safety profile of stiripentol is good, with most adverse events related to a significant increase in plasma concentrations of valproate and clobazam after the addition of stiripentol (Perez 1999). Adverse events include drowsiness, ataxia, nausea, abdominal pain and loss of appetite with weight loss. Asymptomatic neutropenia is occasionally observed (Chiron 2007).

How the intervention might work

Stiripentol is structurally unrelated to any other marketed AED. An effect of stiripentol pertaining to gamma‐aminobutyric acid (GABA), which has been demonstrated in vitro (Quilichini 2006), is probably due to allosteric modulation of the GABA‐A receptor (Fisher 2009). The efficacy of stiripentol could therefore be related to potentiation of GABAergic inhibitory neurotransmission (Quilichini 2006), and enhancement of the action of benzodiazepines (Fisher 2009). In humans, stiripentol also inhibits cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP) in the liver, resulting in increased plasma concentrations of concomitant AEDs metabolised by CYP (Chiron 2005). In patients affected by severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy, now usually known as Dravet syndrome, such a pharmacokinetic interaction particularly applies to clobazam (Giraud 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

To date, no studies have systematically reviewed the literature on the role of stiripentol as treatment for focal drug‐resistant epilepsy; thus its use in conditions other than Dravet syndrome remains to be evaluated.

In this systematic review, we aimed to assess and summarise existing evidence regarding the efficacy and adverse effects of stiripentol as add‐on treatment for people with drug‐resistant focal epilepsy.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of stiripentol as add‐on treatment for people with drug‐resistant focal epilepsy who are taking AEDs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies that met the following criteria.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

Double‐blind, single‐blind or unblinded trials

We decided to include only the above types of studies, as they are considered to provide the most effective means of evaluating benefits and risks of treatment (Strauss 2005).

We excluded all other study designs, including cohort studies, cross‐over studies, case‐control studies, outcomes research, case studies, case series and expert opinions.

We analysed different treatment groups and controls separately.

We applied no language restrictions.

Types of participants

We considered people with focal epilepsy defined according to ILAE criteria (International League Against Epilepsy 1989). We considered participants regardless of age, sex and ethnicity, including children with disabilities. As no definition of drug‐resistant epilepsy has been universally accepted, for the purposes of this review we included all trials conducted to assess stiripentol in drug‐resistant epilepsy, however it was defined, but we noted which definition was used. If possible, on the basis of rough data we considered individuals to be affected by drug‐resistant epilepsy as defined by Kwan 2010. We excluded those affected by Dravet syndrome, as another systematic review of ours specifically assesses the role of stiripentol in this epileptic condition (Brigo 2013).

Types of interventions

Active treatment group received stiripentol, in addition to conventional AED treatment

Control group received no treatment, and matching add‐on placebo or another AED was used as a comparator

Types of outcome measures

For each outcome, we performed an intention‐to‐treat primary analysis to include all participants in the treatment group to which they were allocated, irrespective of the treatment they actually received.

Primary outcomes

Fifty per cent or greater reduction in seizure frequency: proportion of participants with at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency at the end of the study compared with the pre‐randomisation baseline period

Seizure freedom: proportion of participants achieving total cessation of seizures. We used the most current ILAE‐proposed definition of seizure freedom: no seizures of any type for 12 months, or three times the longest (pre‐intervention) seizure‐free interval, whichever is longest (Kwan 2010)

Secondary outcomes

-

Adverse effects

Proportion of participants who experienced at least one adverse effect

Proportion of participants who experienced individual adverse effects (to be listed separately)

Proportion of dropouts or withdrawals due to adverse effects, lack of efficacy or other reasons

Improvement in quality of life as assessed by validated and reliable rating scales (e.g. Quality of Life In Epilepsy (QOLIE‐31))

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Searches were run for the original review in May 2012. Subsequent searches were run in August 2013, August 2015 and August 2017. For the latest update, we searched the following databases on 27 February 2020.

Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS Web), using the search strategy set out in Appendix 3

MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 26 February 2020), using the search strategy set out in Appendix 1

CRS Web includes randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials from PubMed, Embase, ClinicalTrials.gov, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and the Specialized Registers of Cochrane Review Groups including Epilepsy.

We imposed no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We contacted the manufacturers of stiripentol (Biocodex) (contacted by email on 31 May 2012, on 13 August 2015 and on 22 August 2017) and experts in the field (contacted by email on 31 May 2012, on 13 August 2015 and on 22 August 2017) for information about unpublished or ongoing studies. We reviewed the reference lists of retrieved studies to search for additional reports of relevant studies. We also considered conference proceedings of the ILAE.

Data collection and analysis

We did not implement intended methods for assessing heterogeneity, reporting biases, synthesising data and performing subgroup and sensitivity analyses found in the protocol of this systematic review because of the low number of studies (Brigo 2012). In case future review updates identify more than one study, we may conduct data analyses referring to methods reported in the previously published protocol of the present systematic review (Brigo 2012).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (FB and SCI) independently screened titles and abstracts of all publications identified by the searches to assess their eligibility. At this stage, we excluded publications that did not meet inclusion criteria. After screening, we assessed the full‐text articles of potentially eligible citations for inclusion. We reached consensus on selection of trials and on the final list of studies. We resolved disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (FB and SCI) independently extracted the following characteristics of each included trial from the published reports, when possible. We used data extraction forms and resolved disagreements by mutual agreement. We recorded the rawest form of data, when possible. In the case of missing or incomplete data, we contacted the principal investigators of included trials to request the required additional information.

Participant factors

Age

Sex

Epileptic seizure type and epilepsy syndrome

Causes of epilepsy

Duration of epilepsy

Number of seizures or seizure frequency before randomisation

Presence of status epilepticus

Numbers and types of AEDs previously taken

Concomitant AEDs

Presence of neurological deficit/signs

Neuropsychological status

Electroencephalographic (EEG) findings

Neuroradiological findings (computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI))

Trial design

Criteria used to diagnose epilepsy

Definition of drug‐resistant or refractory epilepsy

Trial design (i.e. RCT, parallel group or cross‐over, single‐blinded or double‐blinded)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Method of randomisation

Method of allocation concealment

Method of blinding

Stratification factors

Number of participants allocated to each group

Duration of different phases of the trial (baseline, titration, maintenance and optional open‐label extension (if any))

Intervention and control

Intervention given to controls

Dosage of stiripentol

Duration of treatment period

Follow‐up data

Duration of follow‐up

Reasons for incomplete outcome data

Dropout or loss to follow‐up rates

Methods of analysis (e.g. intention‐to‐treat, per‐protocol, worst‐case or best‐case scenario)

Primary outcomes

Fifty per cent or greater reduction in seizure frequency: proportion of participants with at least 50% reduction in seizure frequency at the end of the study (numerator)/number of participants at pre‐randomisation baseline period (denominator)

Seizure freedom: proportion of participants achieving total cessation of seizures (numerator)/number of participants at pre‐randomisation baseline period (denominator)

Secondary outcomes

Incidence of adverse effects of any type: numbers of adverse effects (numerator)/total number of participants at pre‐randomisation baseline period (denominator)

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (FB and NLB) assessed risk of bias of each trial according to approaches described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assigned risk of bias as yes (low risk of bias), no (high risk of bias) or unclear (uncertain risk of bias).

We evaluated the following characteristics.

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

Incomplete outcome data

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

Other bias (including outcome reporting bias)

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we extracted the number of participants in each arm who experienced the outcome of interest. Data for our chosen outcomes were dichotomous, and our preferred outcome statistic was the risk ratio (RR), calculated with uncertainty in each trial, expressed with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Dealing with missing data

For each outcome, we performed an intention‐to‐treat primary analysis to include all participants in the treatment group to which they were allocated, irrespective of the treatment they actually received.

Assessment of heterogeneity

As only one study satisfied our inclusion criteria, we did not perform an assessment of heterogeneity.

If we had included more than one study, we would have assessed heterogeneity as follows.

For each outcome, we would have made an intention‐to‐treat primary analysis in order to include all patients in the treatment group to which they were allocated, irrespective of the treatment they actually received. We would have tested heterogeneity of the intervention effects among trials using the standard Chi² statistic (P value) and the I² statistic. We would have evaluated homogeneity among trial results using a standard Chi² test and we would have rejected the hypothesis of homogeneity if the P value was less than 0.10.

Our interpretation of I² for heterogeneity would have been as follows.

• 0% to 40%: may not be important • 30% to 60%: represents moderate heterogeneity • 50% to 90%: represents substantial heterogeneity • 75% to 100%: represents considerable heterogeneity

We would have combined trial outcomes to obtain a summary estimate of effect (and the corresponding CIs) using a fixed‐effect model unless there had been significant heterogeneity (that is I² > 75%). If there had been substantial heterogeneity we planned to explore the contributing factors for heterogeneity. If there was substantial heterogeneity that could not readily be explained we would have used a random‐effects model.

We would have assessed possible sources of heterogeneity (for example clinical heterogeneity, methodological heterogeneity or statistical heterogeneity) by using sensitivity analysis as described below.

Assessment of reporting biases

As only one study satisfied our inclusion criteria, we did not carry out an analysis of reporting biases.

If we had included more than one study, we would have assessed reporting bias as follows (Brigo 2012).

We would have used a funnel plot to detect reporting biases when sufficient numbers of studies (10 or more) were available. There are several possible sources of funnel plot asymmetry (publication bias, language bias, citation bias, poor methodological quality, true heterogeneity, etc.) and we would have analysed them according to the trials.

Data synthesis

As only one study satisfied our inclusion criteria, we did not perform a meta‐analysis.

If we had included more than one study, we would have synthesised data as follows.

Provided we thought it clinically appropriate, and we found no important clinical and methodological heterogeneity, we would have planned to synthesise the results in a meta‐analysis.

We would have synthesised data on all seizures and also according to seizure type. We would have analysed different treatments and controls separately, including no treatment and placebo together. We would have used Review Manager 5 to combine trial data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As eligible data were limited, we did not perform subgroup analysis.

As per protocol, we planned no subgroup analysis to further investigate heterogeneity (Brigo 2012).

Sensitivity analysis

As eligible data were limited, we did not perform a sensitivity analysis.

If we had included more than one study, we would have performed sensitivity analysis as follows.

In the case of residual unexplained heterogeneity, we would have evaluated the robustness of the results of the meta‐analysis by comparing fixed‐effect and random‐effects model estimates, removing trials with low methodological quality or excluding trials with large effect size. We would have also used the worst‐case and best‐case scenarios whenever possible. If the conclusions we observed remained unchanged, then we would have considered the evidence to be robust.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used GRADE quality assessment criteria in the Table 1, including all outcomes assessed in this review (Guyatt 2008).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

The only included trial—Chiron 2006—used a responder‐enriched design, whereby participants responding to stiripentol during a pre‐randomisation baseline phase were randomly assigned to continue stiripentol or to have it withdrawn. This trial therefore compared the effects of continuing versus withdrawing stiripentol. We only included data from the randomised, double‐blind, add‐on, placebo‐controlled portion of the trial in the present review.

Results of the search

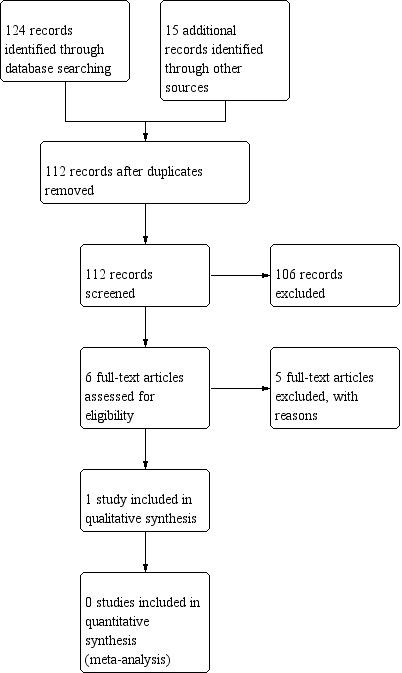

The update of searches for this review yielded two results (Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS Web) (0); MEDLINE 1946 to 26 February 2020 (2)). We found no duplicates. After removing one obviously irrelevant item, we identified one article for possible inclusion. On further evaluation of title and abstract, we also excluded this article as it did not meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Hence, review authors found no additional studies for inclusion in this updated version of this review. In the previous versions of this review (Brigo 2014; Brigo 2015; Brigo 2018), we identified one study that met our inclusion criteria (Chiron 2006).

1.

Study flow diagram. The results shown in this figure include the original searches conducted for the review and all subsequent updates.

Included studies

Chiron 2006

Investigators in Chiron 2006 aimed to study stiripentol as add‐on therapy to carbamazepine for childhood focal epilepsy by adopting a responder‐enriched design. Participants were 32 children with focal epilepsy. All included participants were defined as "refractory to the usual antiepileptic drugs (including valproate, carbamazepine, benzodiazepines and phenytoin), as well as to vigabatrin". Presence of drug‐resistant epilepsy was not, however, specified among the inclusion criteria. The study included 18 boys (seven in the stiripentol group and 11 in the add‐on placebo group) and 14 girls (10 in the stiripentol group and four in the add‐on placebo group). Mean age was 8 ± 3 years (mean ± standard deviation) among participants in the stiripentol group and 10.4 ± 3.4 years in the add‐on placebo group.

The first study period consisted of a one‐month baseline with a single‐blind, add‐on placebo. The second period was a four‐month open phase with open, add‐on stiripentol. These first two study periods adopted a non‐randomised before‐after design. At the end of this open phase, responders (defined as participants with at least a 50% decrease in seizure frequency during the open period versus baseline) were randomly assigned to stiripentol or to add‐on placebo for a two‐month, double‐blind period. Then all participants received long‐term open stiripentol.

The following criteria were required for patients to be included in the baseline period: (1) focal seizures; (2) receiving carbamazepine as co‐medication, with a benzodiazepine (clobazam or clonazepam) or vigabatrin, or both, administered in association; and (3) receiving at least 400 mg/day of carbamazepine. Participants had to be responders (i.e. experiencing ≥ 50% decrease in seizure frequency during the third month of the open period versus baseline) in the open phase to be eligible for randomisation. Researchers did not include participants receiving other drugs or those whose parents were unable to comply regularly with drug delivery and daily seizure diaries.

Investigators reported neither conflicts of interest nor study sponsors.

Excluded studies

None of the articles obtained by the updated search strategy appeared to meet the eligibility criteria (see Results of the search); we therefore considered them not relevant.

In the previous versions of this review—Brigo 2014, Brigo 2015 and Brigo 2018—we excluded three studies as they were non‐randomised trials (Loiseau 1988; Perez 1999; Rascol 1989). These studies adopted an uncontrolled before‐after design. Chiron 2000, published as a conference proceeding, provided preliminary results (interim analyses) of the study of Chiron 2006, which was published a few years later as an in extenso paper presenting definitive results; we included it in the present review. The other excluded study was a randomised, double‐blind, parallel‐group trial that evaluated the efficacy of stiripentol as add‐on therapy to carbamazepine versus carbamazepine monotherapy in individuals with epilepsy uncontrolled by carbamazepine monotherapy (Loiseau 1990). We excluded this study because it did not clearly specify whether patients with focal epilepsy were included. Moreover, this study was conducted in individuals with epilepsy "uncontrolled by carbamazepine monotherapy": most available definitions of drug‐resistant epilepsy require failure of at least two AEDs for such a diagnosis (Berg 2006). As a consequence, we did not consider participants in this study as affected by drug‐resistant epilepsy, even when we applied the internationally accepted definition of drug‐resistant epilepsy: failure of adequate trials of two tolerated, appropriately chosen and used AED schedules (whether given as monotherapy or in combination) to achieve sustained seizure freedom (Kwan 2010).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies.

Allocation

Researchers in Chiron 2006 used a computer‐generated list to randomly assign participants, and a pharmacist dosed the tablets, to ensure that investigators were blinded (low risk of selection bias).

Blinding

Study authors described the second part of the trial as double‐blinded (low risk of performance bias). Each participant received tablets of both stiripentol and "placebo of stiripentol" and tablets of both carbamazepine and "placebo of carbamazepine", and a pharmacist prepared the individual tablets (low risk of selection bias). Part of the carbamazepine schedule was administered as "open carbamazepine"; however, the dose could be decreased when necessary.

Incomplete outcome data

Investigators reported the number of dropouts and specified reasons for dropout. Although these reasons were similar among participants in the two groups, and despite the fact that strict escape criteria were specifically required for a responder‐enriched design, the number of dropouts in both arms (add‐on stiripentol and placebo) was high and far exceeded 20% (53.3 versus 35.3) (high risk of attrition bias).

Selective reporting

Published reports included all expected outcomes (low risk of reporting bias).

Other potential sources of bias

Through its responder‐enriched design, this study conducted a primary efficacy evaluation of an enriched population of participants, as the result of random assignment only of participants who responded to open‐label treatment (high risk of selection bias).

This trial used as a primary endpoint the number of participants who met the escape criteria during the double‐blind period, defined as (1) increased seizure frequency during the double‐blind period compared with the pre‐randomisation period; (2) significantly increased seizure severity during the double‐blind period compared with the open period; and (3) status epilepticus during the double‐blind period. However, this study provided individual participant data only for the randomised, double‐blind portion of the trial, thus allowing us to include this information in the present review.

Length of follow‐up for the randomised, double‐blind study (only two months) was not adequate for evaluation of a change in seizure frequency.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Add‐on stiripentol versus add‐on placebo

See Table 1

We found one study that compared add‐on stiripentol with add‐on placebo and recruited 32 participants (Chiron 2006). As outlined under Description of studies above, this trial used a responder‐enriched design, whereby participants responding to stiripentol during a pre‐randomisation baseline phase were randomly assigned to continue stiripentol or to have it withdrawn. This trial therefore compared the effects of continuing versus withdrawing stiripentol.

Primary outcomes

See Data and analyses.

Fifty per cent or greater reduction in seizure frequency, and seizure freedom

No clear evidence showed a reduction in seizure frequency (≥ 50% seizure reduction) (RR 1.51, 95% CI 0.81 to 2.82; Analysis 1.1) nor occurrence of seizure freedom (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.31 to 4.43; Analysis 1.2) when add‐on stiripentol was compared with placebo, although a non‐significant trend favouring add‐on stiripentol was reported for both outcomes. In the add‐on placebo group, 4 out of 15 participants experienced worsening of seizure frequency compared with the baseline period.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Add‐on stiripentol versus placebo, Outcome 1: ≥ 50% seizure reduction

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Add‐on stiripentol versus placebo, Outcome 2: Seizure freedom

Secondary outcomes

See Data and analyses.

Adverse effects

Add‐on stiripentol led to greater risk of adverse effects considered as a whole (RR 2.65, 95% CI 1.08 to 6.47) when compared with placebo (Analysis 1.3). When we considered specific adverse events, confidence intervals were very wide and included the possibility of substantial increases and small reductions in risk of neurological adverse effects (RR 2.65, 95% CI 0.88 to 8.01; Analysis 1.4); or gastrointestinal adverse effects (RR 11.56, 95% CI 0.71 to 189.36; Analysis 1.5).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Add‐on stiripentol versus placebo, Outcome 3: ≥ 1 adverse effect

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Add‐on stiripentol versus placebo, Outcome 4: Neurological adverse effects

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Add‐on stiripentol versus placebo, Outcome 5: Gastrointestinal adverse effects

Proportion of dropouts or withdrawals due to side effects, lack of efficacy or other reasons

We noted no clear reduction in the risk of study withdrawal (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.47), which was high in both groups (35.0% in add‐on placebo and 53.3% in stiripentol group) (Analysis 1.6). Eight participants in the add‐on placebo group (35.3%) dropped out because of loss of response (seven for an increase in seizure frequency and one for an increase in seizure severity), and four experienced worsening compared with baseline. Six participants in the stiripentol group (53.3%) dropped out (five because of an increase in seizure frequency and one for an increase in seizure severity).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Add‐on stiripentol versus placebo, Outcome 6: Dropouts

Improvement in quality of life as assessed by validated and reliable rating scales

The included study did not assess this outcome.

Discussion

This review aimed to assess the efficacy and tolerability of stiripentol as add‐on treatment for drug‐resistant epilepsy.

In this updated version of the systematic review, we identified no additional studies for inclusion. Hence we have made no changes to the conclusions of this update as presented in the initial review (Brigo 2014); and in the updated versions (Brigo 2015; Brigo 2018).

Summary of main results

We included only one study, which we identified in the first version of this review (Chiron 2006). This study adopted a responder‐enriched design. Although all included participants were "refractory to the usual antiepileptic drugs (including valproate, carbamazepine, benzodiazepines and phenytoin), as well as to vigabatrin as a new drug", the presence of drug‐resistant epilepsy was not considered among the inclusion criteria. Furthermore, investigators did not provide a definition of refractory epilepsy.

The only study we included in the present review found no clear evidence of seizure reduction (≥ 50%) or of seizure freedom with add‐on stiripentol compared with placebo. Add‐on stiripentol led to greater risk of adverse effects considered as a whole compared with placebo; however we are uncertain of this effect, because the results are imprecise. We found no clear difference in neurological adverse effects and in gastrointestinal adverse effects between add‐on stiripentol and placebo, although the included study showed a non‐significant trend toward more frequent adverse effects after add‐on stiripentol. The study showed no clear differences in the proportion of dropouts between add‐on stiripentol and add‐on placebo, although with a trend toward increased dropouts among add‐on placebo participants.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Despite an overall low risk of bias, the responder‐enriched design of the included trial raises several ethical and methodological concerns. This design shifts the focus to a participant subgroup when accumulating data suggest greatest benefit for that subgroup. Only the second portion of this study met the inclusion criteria of the systematic review (randomised, add‐on, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind trial), whereas the first portion of the study adopted a non‐randomised, before‐after design. Inclusion of responders to add‐on stiripentol alone (i.e. those experiencing a ≥ 50% decrease in seizure frequency during the third month of the open period versus baseline) in the second portion of the study may severely reduce the external validity of the results, limiting their generalisation to a more widespread population. This study design has therefore resulted in a primary efficacy evaluation of a highly selected 'enriched' population of participants as a result of random assignment only of those who responded to open‐label treatment (high risk of selection bias).

Furthermore, a responder‐enriched design carries the risk of a carry‐over effect in the add‐on placebo group. A carry‐over effect occurs when the effects of an intervention given during one period persist into a subsequent period, thus interfering with the effects of a different subsequent intervention. Risk of a carry‐over effect in the add‐on placebo group of the included study seems to be high, because in the add‐on placebo group, add‐on stiripentol was withdrawn over three weeks (a long period, especially given that the overall length of the randomised, double‐blind portion of the trial was only two months). Furthermore, investigators included no washout period during the randomised, double‐blind phase, to reduce the carry‐over effect. As a consequence, it is likely that a carry‐over effect may have influenced outcomes related to seizure frequency in the included study, with possible reduction in seizure frequency in the add‐on placebo group. Conversely, a responder‐enriched design carries the risk of a withdrawal effect secondary to withdrawal of add‐on stiripentol in the add‐on placebo group during the randomised add‐on placebo‐controlled phase of the trial. The withdrawal effect may be responsible for an increase in seizure frequency (which, unlike reduction in seizure frequency, becomes a relevant endpoint within such a study design). This should be carefully taken into account when strict escape criteria are defined, to prevent exposure of participants in the add‐on placebo group to seizures that may become more severe or more prolonged and may even evolve into status epilepticus. Regarding this last aspect, it is noteworthy to consider that in both the add‐on stiripentol and add‐on placebo arms the percentage of dropouts was extremely high as the result of an increase in seizure frequency or severity.

Length of follow‐up for the randomised, double‐blind study (only two months) was probably inadequate to permit evaluation of changes in seizure frequency.

Additional research is needed to assess the efficacy and tolerability of add‐on stiripentol for treatment of drug‐resistant focal epilepsy. Future studies should be randomised and double‐blinded, should aim to recruit a sufficiently large number of participants and should assess clinically meaningful outcome measures, while adopting an internationally accepted definition of drug‐resistant epilepsy (Kwan 2010).

Certainty of the evidence

We are prevented from generalisation of study results to a more widespread population by the fact that only responders to add‐on stiripentol (i.e. those experiencing a ≥ 50% decrease in seizure frequency versus baseline) were included in the randomised, add‐on, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind portion of the study. Also, the very small sample size with correspondingly high dropout rates prevents generalisation of study results. Finally, because of the adopted design, carry‐over and withdrawal effects probably influenced outcomes related to seizure frequency. Using the GRADE methodology, we rated the certainty of the evidence as low.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

No other studies or reviews on the same topic have been published so far.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We have found no new studies since the last version of this review and we have therefore made no changes in this update to conclusions as presented in the initial review. Currently, no available evidence supports use of add‐on stiripentol for treatment of drug‐resistant focal epilepsy. Although we derived very limited information from only one included study, investigators noted that adverse effects considered as a whole seemed to occur significantly more frequently with add‐on stiripentol than with add‐on placebo.

Implications for research.

Additional research is needed to assess the efficacy and tolerability of add‐on stiripentol for treatment of drug‐resistant focal epilepsy. Future research should consist of randomised, double‐blind studies and should aim to recruit sufficiently large numbers of participants and assess clinically meaningful outcome measures. Investigators should avoid a responder‐enriched design because of the risk of carry‐over and withdrawal effects in the add‐on placebo group, and because of the reduced external validity of this study design. Furthermore, they should adopt the internationally accepted definition of drug‐resistant epilepsy.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 February 2020 | New search has been performed | Searches updated 27 February 2020; no new studies were identified. |

| 27 February 2020 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions are unchanged. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 5, 2012 Review first published: Issue 1, 2014

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 August 2017 | New search has been performed | Searches updated 21 August 2017; no new studies were identified. |

| 21 August 2017 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions are unchanged. |

| 10 August 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No new relevant studies identified; no changes made to conclusions |

| 10 August 2015 | New search has been performed | Searches updated 10 August 2015 |

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Cochrane Epilepsy for continuous support as we prepared this review. We are indebted to the following epilepsy experts, whom we contacted for information about unpublished or ongoing studies: Blaise Bourgeois, Barry Gidal, William H Theodore, Stefano Sartori, Jacqueline French and Eugen Trinka. We also thank Professor Anthony Marson, of Cochrane Epilepsy, for his kind support. We thank Marie‐Emmanuelle le Guern (Biocodex) for providing us with recent publications and for searching unpublished or ongoing trials related to use of add‐on stiripentol in epilepsy.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

This strategy includes the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials (Lefebvre 2019).

1. (stiripentol or Diacomit).tw.

2. exp Epilepsies, Partial/

3. ((partial or focal) and (seizure$ or epilep$)).tw.

4. 2 or 3

5. (randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial or pragmatic clinical trial).pt. or (randomi?ed or placebo or randomly).ab.

6. clinical trials as topic.sh.

7. trial.ti.

8. 5 or 6 or 7

9. exp animals/ not humans.sh.

10. 8 not 9

11. 1 and 4 and 10

12. (monotherap$ not (adjunct$ or "add‐on" or "add on" or adjuvant$ or combination$ or polytherap$)).ti.

13. 11 not 12

14. limit 13 to ed=20170821‐20200227

15. 13 not (1$ or 2$).ed.

16. 15 and (2017$ or 2018$ or 2019$ or 2020$).dt.

17. 14 or 16

18. remove duplicates from 17

Appendix 2. Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS Web) search strategy

1. (stiripentol or diacomit):AB,KW,KY,MC,MH,TI AND CENTRAL:TARGET

2. MESH DESCRIPTOR Epilepsies, Partial EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET

3. ((partial or focal) and (seizure* or epilep*)):AB,KW,KY,MC,MH,TI AND CENTRAL:TARGET

4. #2 OR #3 AND CENTRAL:TARGET

5. #1 AND #4

6. (monotherap* NOT (adjunct* OR "add‐on" OR "add on" OR adjuvant* OR combination* OR polytherap*)):TI AND CENTRAL:TARGET

7. #5 NOT #6

8. #7 AND >21/08/2017:CRSCREATED

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Add‐on stiripentol versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 ≥ 50% seizure reduction | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [0.81, 2.82] |

| 1.2 Seizure freedom | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.31, 4.43] |

| 1.3 ≥ 1 adverse effect | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.65 [1.08, 6.47] |

| 1.4 Neurological adverse effects | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.65 [0.88, 8.01] |

| 1.5 Gastrointestinal adverse effects | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 11.56 [0.71, 189.36] |

| 1.6 Dropouts | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.30, 1.47] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Chiron 2006.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Controlled trial using a responder‐enriched design First 2 study periods adopted a non‐randomised before‐after design Second portion of the trial adopted a randomised, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, parallel design Only the second portion of this responder‐enriched trial was included |

|

| Participants | Individuals who were responders when taking add‐on stiripentol during a pre‐randomisation baseline period were randomly assigned to continue add‐on stiripentol or to add‐on placebo. All participants who entered the preceding study were children with focal epilepsy. 32 participants were randomly assigned: 17 to add‐on stiripentol and 15 to add‐on placebo Add‐on stiripentol group: 7 male, 10 female (total 17 participants); age: 8 ± 3 years (mean ± standard deviation) Add‐on placebo group: 11 male, 4 female (total 15 participants); age: 10.4 ± 3.4 years Inclusion criteria for baseline period

Inclusion criteria for randomised, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, trial

Exclusion criteria for baseline period

Exclusion criteria during double‐blind period

|

|

| Interventions |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were randomly assigned by a computer‐generated list |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central allocation (pharmacy‐controlled randomisation). "Each patient received tablets of both stiripentol and "placebo of stiripentol" and tablets of both carbamazepine and "placebo of carbamazepine". "Individual tablets were prepared by the pharmacist" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Second part of the trial was defined as “double blind”. "Each patient received tablets of both stiripentol and "placebo of stiripentol" and tablets of both carbamazepine and "placebo of carbamazepine". "Individual tablets were prepared by the pharmacist" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Each patient received tablets of both stiripentol and "placebo of stiripentol" and tablets of both carbamazepine and "placebo of carbamazepine". "Individual tablets were prepared by the pharmacist" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Numbers of dropouts from each group were reported, along with reasons for dropout. However, number of dropouts in both arms was high (add‐on stiripentol and add‐on placebo) (53.3% vs 35.3%) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Study protocol is not available, but published reports include all expected outcomes |

| Other bias | High risk | Through its responder‐enriched design, this study resulted in a primary efficacy evaluation of an enriched population of participants, as a result of random assignment only of those who responded to open‐label treatment (high risk of selection bias). High risk of carry‐over and withdrawal effects |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by year]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Loiseau 1988 | Not randomised. Uncontrolled before‐after design |

| Rascol 1989 | Not randomised. Uncontrolled before‐after design |

| Loiseau 1990 | Not specified whether study was conducted in individuals with focal epilepsy. Not conducted in those with refractory epilepsy |

| Perez 1999 | Not randomised. Uncontrolled before‐after design |

| Chiron 2000 | This study was published as a conference proceeding and provided preliminary results (interim analyses) of the study of Chiron 2006, which was published a few years later and is included in the review |

Differences between protocol and review

We added the GRADE quality assessment criteria in the 'Summary of findings' table (Guyatt 2008).

Contributions of authors

Francesco Brigo conceived the idea and developed the project. Francesco Brigo and Monica Storti designed the protocol. Francesco Brigo and Nicola L Bragazzi assessed studies for inclusions. Francesco Brigo wrote the text of the updated review, which was critically revised by Stanley C Igwe and Nicola L Bragazzi.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

National Institute for Health Research, UK

This review update was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) [Clinically effective treatments for central nervous system disorders in the NHS, with a focus on Epilepsy and Movement Disorders (SRPG project 16/114/26)]. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Declarations of interest

Francesco Brigo: received travel support and accommodation by Lusofarmaco to attend the annual Congress of the Italian Chapter of ILAE; he received speaking fees from Lusofarmaco. Stanley C Igwe: none known Nicola L Bragazzi: none known

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Chiron 2006 {published data only}

- Chiron C, Tonnelier S, Rey E, Brunet ML, Tran A, d'Athis P, et al. Stiripentol in childhood partial epilepsy: randomized placebo-controlled trial with enrichment and withdrawal design. Journal of Child Neurology 2006;21(6):496-502. [DOI: 10.1177/08830738060210062101] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Chiron 2000 {published data only}

- Chiron C, Tran A, Rey E, d'Athis P, Vincent J, Tonnelier S, et al. Stiripentol in childhood partial epilepsy: a placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia 2000;41(Suppl 7):191, Abstract no: 3.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Loiseau 1988 {published data only}

- Loiseau P, Strube E, Tor J, Levy RH, Dodrill C. Neurophysiological and therapeutic evaluation of stiripentol in epilepsy. Preliminary results. Revue Neurologique 1988;144(3):165-72. [PMID: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Loiseau 1990 {published data only}

- Loiseau P, Levy RJ, Houin G, Rascol O, Dordain G. Randomized double-blind, parallel, multicenter trial of stiripentol added to carbamazepine in the treatment of carbamazepine-resistant epilepsies. An interim analysis. Epilepsia 1990;31(5):618-9. [Google Scholar]

Perez 1999 {published data only}

- Perez J, Chiron C, Musial C, Rey E, Blehaut H, d'Athis P, et al. Stiripentol: efficacy and tolerability in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia 1999;40(11):1618-26. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb02048.x] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rascol 1989 {published data only}

- Rascol O, Squalli A, Montastruc JL, Garat A, Houin G, Lachau S, et al. A pilot study of stiripentol, a new anticonvulsant drug, in complex partial seizures uncontrolled by carbamazepine. Clinical Neuropharmacology 1989;12(2):119-23. [DOI: 10.1097/00002826-198904000-00006] [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Berg 2006

- Berg AT, Kelly MM. Defining intractability: comparisons among published definitions. Epilepsia 2006;47(2):431-6. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Berg 2010

- Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, Buchhalter J, Cross JH, Van Emde Boas W, et al. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia 2010;51(4):676-85. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brigo 2013

- Brigo F, Storti M. Antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010483.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chiron 2005

- Chiron C. Stiripentol. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 2005;14(7):905-11. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chiron 2007

- Chiron C. Stiripentol. Neurotherapeutics 2007;4(1):123. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cockerell 1995

- Cockerell OC, Johnson AL, Sander JW, Hart YM, Shorvon SD. Remission of epilepsy: results from the National General Practice Study of Epilepsy. Lancet 1995;346(8968):140-4. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fisher 2009

- Fisher JL. The anti-convulsant stiripentol acts directly on the GABA(A) receptor as a positive allosteric modulator. Neuropharmacology 2009;56(1):190-7. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

French 2006

- French JA. Refractory epilepsy: one size does not fit all. Epilepsy Currents 2006;6(6):177-80. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Giraud 2006

- Giraud C, Treluyer JM, Rey E, Chiron C, Vincent J, Pons G, et al. In vitro and in vivo inhibitory effect of stiripentol on clobazam metabolism. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2006;34(4):608-11. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Granata 2009

- Granata T, Marchi N, Carlton E, Ghosh C, Gonzalez-Martinez J, Alexopoulos AV, et al. Management of the patient with medically refractory epilepsy. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 2009;9(12):1791-802. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2008

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-YtterY, Alonso-Coello P, et al, GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336(7650):924-6. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

International League Against Epilepsy 1989

- Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia 1989;30(4):389-99. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kwan 2010

- Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, Brodie MJ, Hauser WA, Mathern G, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia 2010;51(6):1069-77. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lefebvre 2019

- Lefebvre C, Glanville J, Briscoe S, Littlewood A, Marshall C, Metzendorf M-I, et al. Technical Supplement to Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston MS, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6. Cochrane, 2019. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Quilichini 2006

- Quilichini PP, Chiron C, Ben-Ari Y, Gozlan H. Stiripentol, a putative antiepileptic drug, enhances the duration of opening of GABA-A receptor channels. Epilepsia 2006;47(4):704-16. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Strauss 2005

- Strauss S, Richardson W, Glasziou P, Haynes R. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 3rd edition. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone, 2005. [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Brigo 2012

- Brigo F, Storti M. Stiripentol for focal refractory epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 5. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009887] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brigo 2014

- Brigo F, Storti M. Stiripentol for focal refractory epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009887.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brigo 2015

- Brigo F, Igwe SC, Bragazzi NL. Stiripentol for focal refractory epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009887.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brigo 2018

- Brigo F, Igwe SC, Bragazzi NL. Stiripentol add-on therapy for focal refractory epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 5. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009887.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]