Abstract

Background

Hyperkalaemia is a common electrolyte abnormality caused by reduced renal potassium excretion in patients with chronic kidney diseases (CKD). Potassium binders, such as sodium polystyrene sulfonate and calcium polystyrene sulfonate, are widely used but may lead to constipation and other adverse gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, reducing their tolerability. Patiromer and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate are newer ion exchange resins for treatment of hyperkalaemia which may cause fewer GI side‐effects. Although more recent studies are focusing on clinically‐relevant endpoints such as cardiac complications or death, the evidence on safety is still limited. Given the recent expansion in the available treatment options, it is appropriate to review the evidence of effectiveness and tolerability of all potassium exchange resins among people with CKD, with the aim to provide guidance to consumers, practitioners, and policy‐makers.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of potassium binders for treating chronic hyperkalaemia among adults and children with CKD.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 10 March 2020 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised controlled studies (quasi‐RCTs) evaluating potassium binders for chronic hyperkalaemia administered in adults and children with CKD.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed risks of bias and extracted data. Treatment estimates were summarised by random effects meta‐analysis and expressed as relative risk (RR) or mean difference (MD), with 95% confidence interval (CI). Evidence certainty was assessed using GRADE processes.

Main results

Fifteen studies, randomising 1849 adult participants were eligible for inclusion. Twelve studies involved participants with CKD (stages 1 to 5) not requiring dialysis and three studies were among participants treated with haemodialysis. Potassium binders included calcium polystyrene sulfonate, sodium polystyrene sulfonate, patiromer, and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate. A range of routes, doses, and timing of drug administration were used. Study duration varied from 12 hours to 52 weeks (median 4 weeks). Three were cross‐over studies. The mean study age ranged from 53.1 years to 73 years. No studies evaluated treatment in children.

Some studies had methodological domains that were at high or unclear risks of bias, leading to low certainty in the results. Studies were not designed to measure treatment effects on cardiac arrhythmias or major GI symptoms.

Ten studies (1367 randomised participants) compared a potassium binder to placebo. The certainty of the evidence was low for all outcomes. We categorised treatments in newer agents (patiromer or sodium zirconium cyclosilicate) and older agents (calcium polystyrene sulfonate and sodium polystyrene sulfonate). Patiromer or sodium zirconium cyclosilicate may make little or no difference to death (any cause) (4 studies, 688 participants: RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.11, 4.32; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence) in CKD. The treatment effect of older potassium binders on death (any cause) was unknown. One cardiovascular death was reported with potassium binder in one study, showing that there was no difference between patiromer or sodium zirconium cyclosilicate and placebo for cardiovascular death in CKD and HD. There was no evidence of a difference between patiromer or sodium zirconium cyclosilicate and placebo for health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) at the end of treatment (one study) in CKD or HD. Potassium binders had uncertain effects on nausea (3 studies, 229 participants: RR 2.10, 95% CI 0.65, 6.78; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence), diarrhoea (5 studies, 720 participants: RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.47, 1.48; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence), and vomiting (2 studies, 122 participants: RR 1.72, 95% CI 0.35 to 8.51; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence) in CKD. Potassium binders may lower serum potassium levels (at the end of treatment) (3 studies, 277 participants: MD ‐0.62 mEq/L, 95% CI ‐0.97, ‐0.27; I2 = 92%; low certainty evidence) in CKD and HD. Potassium binders had uncertain effects on constipation (4 studies, 425 participants: RR 1.58, 95% CI 0.71, 3.52; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence) in CKD. Potassium binders may decrease systolic blood pressure (BP) (2 studies, 369 participants: MD ‐3.73 mmHg, 95%CI ‐6.64 to ‐0.83; I2 = 79%; low certainty evidence) and diastolic BP (one study) at the end of the treatment. No study reported outcome data for cardiac arrhythmias or major GI events.

Calcium polystyrene sulfonate may make little or no difference to serum potassium levels at end of treatment, compared to sodium polystyrene sulfonate (2 studies, 117 participants: MD 0.38 mEq/L, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.79; I2 = 42%, low certainty evidence). There was no evidence of a difference in systolic BP (one study), diastolic BP (one study), or constipation (one study) between calcium polystyrene sulfonate and sodium polystyrene sulfonate.

There was no difference between high‐dose and low‐dose patiromer for death (sudden death) (one study), stroke (one study), myocardial infarction (one study), or constipation (one study).

The comparative effects whether potassium binders were administered with or without food, laxatives, or sorbitol, were very uncertain with insufficient data to perform meta‐analysis.

Authors' conclusions

Evidence supporting clinical decision‐making for different potassium binders to treat chronic hyperkalaemia in adults with CKD is of low certainty; no studies were identified in children. Available studies have not been designed to measure treatment effects on clinical outcomes such as cardiac arrhythmias or major GI symptoms. This review suggests the need for a large, adequately powered study of potassium binders versus placebo that assesses clinical outcomes of relevance to patients, clinicians and policy‐makers. This data could be used to assess cost‐effectiveness, given the lack of definitive studies and the clinical importance of potassium binders for chronic hyperkalaemia in people with CKD.

Plain language summary

Are potassium treatments effective for reduce the excess of potassium among people with chronic kidney disease?

What is the issue?

High levels of potassium (a body salt) can build up with chronic kidney disease. This can lead to changes in muscle function including the heart muscle, and cause problems with heart rhythms that can be dangerous. Dialysis can remove potassium from the blood, but for some patients levels can still be high. Patients with severe kidney failure who have not yet started dialysis may have high potassium levels. Treatments have been available for many years but can cause constipation and abdominal discomfort, which make them intolerable for many patients. Newer treatments have been developed including patiromer and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate. These may be more tolerable but it is uncertain whether they help to prevent heart complications.

What did we do?

We searched for all the research trials that have assessed the potassium‐lowering treatments for children and adults with chronic kidney diseases. We evaluated how certain we could be about the overall findings using a system called "GRADE".

What did we find?

There are 15 studies involving 1849 randomised adults. Patients in the studies were given a potassium binder or a dummy pill (placebo) or standard care. The treatment they got was decided by random chance. The studies were generally short‐term over days to weeks and focused on potassium levels. Heart related complications could not be measured in this short time frame. Based on the existing research, we can't be sure whether potassium binders improve well‐being or prevent complications in people with chronic kidney disease. There were no studies in children.

Conclusions

We can't be certain about the best treatments to reduce body potassium levels for people with chronic kidney disease. We need more information from clinical studies that involve a larger number of patients who have the treatment over several months or years.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Hyperkalaemia, defined as a serum potassium > 5.5 mmol/L is one of the most common laboratory electrolyte abnormalities (Betts 2018). Hyperkalaemia may result from various acute and chronic conditions that affect renal potassium excretion including a decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and impaired adaptive responses to hyperkalaemia, such as decreased aldosterone release or extrarenal excretion across the gut. In addition, to impaired potassium excretion in chronic kidney diseases (CKD), hyperkalaemia can be incurred by renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors as first‐line therapy to lower blood pressure (James 2014). Hyperkalaemia frequently results in down‐titration or discontinuation of such guideline‐directed therapy (Collins 2017) and may be associated with poorer clinical outcomes as a result, especially in patients with structural cardiac disease (Montford 2017). Because of the key role of the kidney in maintaining potassium homeostasis, CKD (GFR category 3 to 5) and acute kidney injury are the most important risk factors associated with hyperkalaemia, and as the estimated (e) GFR decreases, the rates of major cardiovascular events and death increase (Tamargo 2018), especially in low‐income countries (Chowdhury 2018).

Hyperkalaemia occurs at a rate of approximately 8/100 person‐months for people with CKD (GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and commonly occurs among people who have other comorbidities such as heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension (Alvarez 2017; Einhorn 2009). The prevalence of hyperkalaemia in the general population has been estimated at 2% to 3% (Kumar 2017). When the eGFR decreases from between 60 to 90 to below 20 mL/min/1.73 m2, the prevalence of hyperkalaemia (> 5 mEq/L) increases from 2% to 42% and to 56.7% in patients with CKD GFR category 5 (Tamargo 2018). Hyperkalaemia has been reported to develop in 44% to 73% of transplant recipients who receive immunosuppressive therapy with cyclosporin or tacrolimus (Palmer 2004).

For many individuals, hyperkalaemia can be asymptomatic or present with nonspecific signs and symptoms (e.g. weakness, fatigue, or gastrointestinal (GI) hypermotility) (Ng 2017) and it has been suggested that the incidence and prevalence of hyperkalaemia in the general population is underestimated (Davidson 2017; Rafique 2017). In the setting of CKD or heart failure, the overall medical costs can be higher for people with hyperkalaemia compared with patients without hyperkalaemia (Alvarez 2017).

Description of the intervention

Until recently, treatment strategies for chronic hyperkalaemia have been limited to dietary potassium restriction, reducing or eliminating exacerbating factors including RAAS inhibitor treatment, mineralocorticoid administration or introducing loop diuretics with or without sodium bicarbonate (Dunn 2015; Fried 2017; Rafique 2017). These treatment options can be unsustainable due to poor tolerability or may be relatively ineffective (dietary restriction).

Potassium binders are artificial resins that exchange cations (e.g. sodium or calcium) bound to a resin for potassium ions in the gut. This exchange increase potassium excretion in the stool.

The potassium exchange resins may be administered orally or per rectum. The first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)‐approved potassium binder for the treatment of hyperkalaemia was sodium polystyrene sulfonate, approved for use in 1958. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate exchanges sodium for potassium, increasing faecal potassium excretion. Despite the absence of high‐quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) confirming benefits on patient‐level outcomes, sodium polystyrene sulfonate became widely used. Documented adverse effects of treatment included nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Co‐administration of sorbitol to increase potassium excretion may infrequently have caused fatal intestinal necrosis (Cowan 2017; Davidson 2017).

A second potassium‐binding agent, calcium polystyrene sulfonate, exchanges calcium for potassium in the distal colon, thus potentially limiting the sodium retention associated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate and providing calcium supplementation. Calcium polystyrene sulfonate may also cause GI adverse events, including colonic necrosis and perforation, which has led to warnings in the prescribing information (Das 2018; Yu 2017).

Newer ion exchange resins have been developed for treatment of hyperkalaemia. These include patiromer and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (also known as ZS‐9) (Cowan 2017). Patiromer is a potassium binder consisting of a non absorbed cation exchange polymer together with a calcium‐sorbitol counter‐ion complex that increases stability. Patiromer exchanges potassium ions for calcium ions, which may limit exposure to sodium for patients who are sensitive to sodium delivery including those with severe kidney, heart, or liver failure. ZS‐9 is an insoluble, non‐absorbed compound that has a lattice structure with octahedral‐ and tetrahedral‐coordinated zirconium and silicon atoms bridged by oxygen that exchange sodium and hydrogen for potassium and ammonium as it moves through the GI tract (Kumar 2017). The zirconium octahedral units confer a negative charge to favour cation exchange and entrapment of potassium ions.

Patiromer and ZS‐9 are available as a powder for oral suspension, and do not expand within the GI tract, which may lead to lower GI adverse effects, such as diarrhoea, constipation, nausea, and vomiting.

Other adverse events are rarely reported. ZS‐9 also binds and excretes ammonium ions which may lead to increased plasma bicarbonate levels at higher doses. These changes might have potential benefit for patients with CKD, who often present with metabolic acidosis (Tamargo 2018).

How the intervention might work

Patiromer lowers and maintains serum potassium levels among people with CKD who are prescribed RAAS inhibitors (AMETHYST‐DN 2015; Weir 2015). ZS‐9 normalises potassium levels in patients receiving RAAS inhibitors for the treatment of cardiovascular or kidney disease (HARMONIZE 2014; Packham 2015). Newer potassium binders may have greater selectivity for potassium than other cations such as calcium and magnesium and may therefore result in lower risk of clinical electrolyte abnormalities.

Through reductions in serum potassium, potassium exchange resins are hypothesised to improve clinically‐relevant endpoints associated with hyperkalaemia such as death and cardiovascular events. However, while potassium exchange resins have been shown to lower serum potassium levels and reduce recurrence of hyperkalaemia compared to placebo (AMETHYST‐DN 2015; HARMONIZE 2014; Packham 2015; PEARL‐HF 2011; Weir 2015) in proof‐of‐concept, short‐term studies, there is limited evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of these interventions on clinically‐relevant endpoints such as hospitalisation and cardiovascular complications (AMETHYST‐DN 2015; Tamargo 2018).

The effectiveness and safety of treatments may differ in people with CKD compared with other populations, due to the increased prevalence of metabolic derangements (e.g. hypocalcaemia, acidosis, and elevated uraemic solutes), bowel dysfunction, structural heart disease, and the altered metabolism of commonly‐used medications that may lead to drug‐drug interactions.

Why it is important to do this review

Newer potassium exchange resins have recently been approved by the FDA (patiromer; FDA 2015 and ZS‐9; FDA 2018) and older agents have been widely adopted into clinical practice. In light of the emergence of new pharmacological agents for hyperkalaemia and recent RCTs, it is necessary to review the evidence of effectiveness and tolerability of all potassium exchange resins among people with CKD.

As current studies of potassium exchange resins principally use hyperkalaemia and serum potassium levels as the primary efficacy outcomes, it is important to accumulate data from all existing studies to evaluate the evidence for patient‐centred endpoints including adverse events and death. A comprehensive systematic review is required to provide guidance to practitioners and policy‐makers interested in using potassium exchange resins for hyperkalaemia and to enable greater use of therapies that may also incur hyperkalaemia, such as RAAS inhibitors. We did not examine studies evaluating treatment of acute hyperkalaemia or emergency interventions for hyperkalaemia as these have been summarised in previous Cochrane reviews (Batterink 2015; Mahoney 2005).

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of potassium binders for treating chronic hyperkalaemia among adults and children with CKD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all RCTs of any design (e.g. parallel, cross‐over, factorial) and controlled clinical studies using a quasi‐randomised method of allocation (such as alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth, or other predictable methods). Reports of studies were eligible regardless of the language used or date of publication. We included studies published as full articles or available as a full study report, studies in which results were published on a trial registry, or studies published as conference proceedings.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

We included studies that enrolled adults and children with CKD and with chronic hyperkalaemia or at risk of chronic hyperkalaemia (including people with progressive kidney decline, comorbidities, the use of medications that affect the RAAS, and a diet high potassium) (Bozkurt 2003; Einhorn 2009; Moranne 2009; RALES 1996; Shah 2005; Weiner 2010). We also included studies involving participants with tubular renal disorders associated with hyperkalaemia, including renal tubular acidosis disorders and pseudo‐hypoaldosteronism types 1 and 2. Chronic hyperkalaemia was defined as serum potassium levels > 5.5 mmol/L (> 5.5 mEq/L). CKD was defined by Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines for evaluation and management of CKD (KDIGO 2013) and included all stages of CKD. We included people treated with dialysis (CKD stage 5D), those who had end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) treated with conservative care, recipients of a kidney transplant (CKD 5T), and those with earlier stages (1 to 4) of CKD. We included studies of potassium binders for hyperkalaemia in people with several medical conditions (such as heart failure) if the study included people with CKD. We obtained all study characteristics and outcome data pertaining to people with CKD, if these data were not available within study reports.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies that evaluated acute management of hyperkalaemia using interventions such as salbutamol, calcium gluconate, insulin‐dextrose, or sodium bicarbonate. We excluded studies of interventions for hyperkalaemia within the hospital setting.

Types of interventions

We included studies that evaluated potassium binders defined as potassium exchange resins that act to bind potassium within the GI tract including calcium polystyrene sulfonate, sodium polystyrene sulfonate with or without sorbitol, patiromer sorbitex calcium, and ZS‐9. Control of serum potassium levels could be achieved regardless of the route of administration, duration, frequency, or dose of the potassium binders. We included interventions administered orally or rectally.

Comparator treatments could be any of the following.

Placebo

Usual care (best supportive care)

Second potassium binder

Dietary restriction

Withdrawal of RAAS inhibition

Different doses of a potassium binder

Different routes of administration

Different frequency of administration.

Types of outcome measures

The outcomes selected included the relevant SONG core outcome sets as specified by the Standardised Outcomes in Nephrology initiative (SONG 2017).

Primary outcomes

Death (any cause and cardiovascular death)

Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) (using any validated HRQoL measure)

GI symptoms (major or minor) (see Table 4 for definitions)

1. List of the most important gastrointestinal side effects.

| Gastrointestinal side effects | |

| Major | Minor |

| Haematemesis | Nausea |

| GI bleeding | Vomiting |

| GI haemorrhage | Gastroenteritis |

| Gastric ulceration | Abdominal pain |

| Gastric cancer | Indigestion |

| Pyloric stenosis | Diarrhoea |

| Melena | Constipation |

| Peptic ulcer | Flatulence |

| Bowel perforation | Heart‐burn |

| Bowel ischemias/necrosis | Dyspepsia |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | ‐ |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | ‐ |

| Crohn's disease | ‐ |

| Ulcerative colitis | ‐ |

| Haemorrhoids | ‐ |

| Diverticulitis | ‐ |

| Appendicitis | ‐ |

| Colitis | ‐ |

| Blood in stool (visible/occult) | ‐ |

| Vomiting blood | ‐ |

| GI event leading to abdominal surgery, including for bowel resection | ‐ |

| Gallstones | ‐ |

| Pancreatitis | ‐ |

GI ‐ gastrointestinal

Secondary outcomes

Serum potassium level

Cardiovascular disease (including cardiac arrhythmia)

Hospitalisation (any cause)

Life participation (any validated measure)

Vascular access

Graft health

Transplant graft loss, acute rejection, function

Fatigue

Cancer

Infection

Blood pressure (BP)

Withdrawal of blood pressure lowering therapy

Adverse events

We included studies that measure outcomes using standardised questionnaires with established reliability and validity (e.g. PIPER Fatigue Scale, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Short‐Form 36 (SF‐36)). We extracted endpoints as post‐intervention mean or change scores, together with standard deviations (SD), or the number of participants experiencing one or more events. We considered the study period and follow‐up as described in the included studies.

We categorised treatments in newer agents (patiromer or ZS‐9) and older agents (calcium polystyrene sulfonate and sodium polystyrene sulfonate). We reported outcomes as newer or older agents. Outcomes were assessed at the end of the follow‐up or as a change during follow‐up. When assessing outcomes in relation to time points, we grouped the data as: immediate post‐intervention, short‐term (post‐intervention to one month), medium‐term (between one and three months follow‐up), and long‐term (more than three months follow‐up) effects. We reported all primary outcomes in a table of Summary of findings for the main comparisons. To maximize clinical utility, we separated studies according to clinical setting (CKD/dialysis/transplant and for adults and children). Where necessary, we showed the overview of our results structure using a diagram to explain to the reader how the information was presented.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 10 March 2020 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Searches of kidney and transplant journals, and the proceedings and abstracts from major kidney and transplant conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available on the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant website.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies, and clinical practice guidelines.

Contacting relevant individuals/organisations seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies.

Grey literature sources (e.g. abstracts, dissertations, and theses), in addition to those already included in the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies, were searched.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may be relevant to the review. The titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable. Studies and reviews that might include relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts and, if necessary, the full text, of these studies to determine which studies satisfy the predetermined inclusion criteria. The review authors resolved discrepancies through discussion or adjudication by a third author.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors using a standard data extraction form developed for this review. The review authors resolved discrepancies through discussion or adjudication by a third author. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data were used. Any discrepancy between published versions was highlighted.

For each included study, we recorded the following:

Study characteristics including type (e.g. parallel, cross‐over, factorial), country, source of funding, and trial registration status (with registration number recorded if available)

Participant characteristics including age, sex, stage of CKD, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria

Intervention characteristics for each treatment group, and use of co‐interventions

Outcomes reports including the measurement instrument used and timing of outcome assessment

To prevent/minimise selective inclusion of data based on the results, we used the following a priori defined decision rules to select data from studies.

Where trial lists report both final values and change from baseline for the same outcome, we extracted final values

Where trial lists report both unadjusted and adjusted values for the same outcome, we extracted unadjusted values

Where trial lists report both data analysed on the intention‐to‐treat principle and another sample (e.g. per protocol, as treated), we extracted intention‐to‐treat data

For cross‐over studies, we extracted data from the first period only.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (death (any cause), myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiac arrhythmia, hospitalisation, dialysis vascular access complications, kidney transplant graft outcomes, cancer, infection, withdrawal of blood pressure lowering therapy, adverse events), results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (HRQoL, serum potassium, life participation scales, depression, kidney transplant function) the mean difference (MD) was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales have been used.

Meta‐analysis of change scores

We considered both change‐from‐baseline and final value scores for continuous outcomes. We combined change‐from‐baseline outcomes with final measurement outcomes using the MD method.

Time‐to‐event outcomes

We did not perform meta‐analysis of time‐to‐event outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised studies

We anticipated that studies using clustered randomisation were controlled for clustering effects. In case of doubt, we contacted the authors to ask for individual participant data to calculate an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC). If this was not possible, we obtained external estimates of the ICC from a similar study or from a study of a similar population as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If ICCs from other sources were used, we reported this and conducted sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC.

Cross‐over studies

Cross‐over studies were analysed using data from the first study period before cross‐over.

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence (e.g. emailing corresponding author/s) and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated and per‐protocol population were carefully performed. Attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (for example, last‐observation‐carried‐forward) were critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

If the number of patients analysed was not presented for each time point, we considered the number of randomised patients in each group at baseline. For continuous outcomes with no SD reported, we calculated SDs from standard errors (SEs), 95% CIs or P‐values using the calculator tool in RevMan. If no measures of variation were reported and SDs could not be calculated, we imputed SDs from other studies in the same meta‐analysis, using the median of the other SDs available. For continuous outcomes presented only graphically, we extracted the mean and 95% CIs from the graphs using plotdigitizer (http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net/). For dichotomous outcomes, we used percentages to estimate the number of events or the number of people assessed for an outcome. Where data were imputed or calculated (e.g. SDs calculated from SEs, 95% CIs or P‐values, or imputed from graphs or from SDs in other studies), we reported this in the Characteristics of included studies.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by determining whether the characteristics of participants, interventions, outcome measures, and timing of outcome measurement are similar across studies. We assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. We quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2003).

We interpreted the I2 statistic using the following as an approximate guide:

0% to 40%: may not be important heterogeneity

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2) (Higgins 2011).

In the case of considerable heterogeneity, we explored the data further by comparing the characteristics of individual studies and any subgroup analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess publication bias, we planned to generate funnel plots if at least 10 studies examining the same treatment comparison were included in the review, and comment on whether any asymmetry in the funnel plot was due to publication bias, or methodological or clinical heterogeneity of the studies. To assess for potential small‐study effects in meta‐analysis (i.e. the intervention effect is more beneficial in smaller studies), we planned to compare effect estimates derived from a random‐effects model and a fixed‐effect model of meta‐analysis. In the presence of small‐study effects, the random‐effects model could give a more beneficial estimate of the intervention than the fixed‐effect estimate.

To assess outcome reporting bias, we compared the outcomes specified in study protocols with the outcomes reported in the corresponding study publications.

Data synthesis

Data were pooled using the random‐effects model but the fixed‐effect model was also used to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform subgroup analysis to explore possible sources of heterogeneity (where sufficient data are available).

Stage of CKD

Co‐prescribing of RAAS inhibitors

However, subgroup analysis could not be done for heterogeneity owing to insufficient data.

Adverse effects were tabulated and assessed with descriptive techniques, as they were likely to be different for the various agents used. Where possible, the risk difference (RD) with 95% CI was calculated for each adverse effect, either compared to no treatment or to another agent.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size.

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis taking account of risk of bias, as specified

Repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), and country

However, sensitivity analysis could not be done for heterogeneity owing to insufficient data.

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schunemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b).

We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Death (any cause)

Cardiovascular death

Cardiac arrhythmia

HRQoL

Serum potassium

Major GI adverse events or minor GI adverse events (constipation)

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

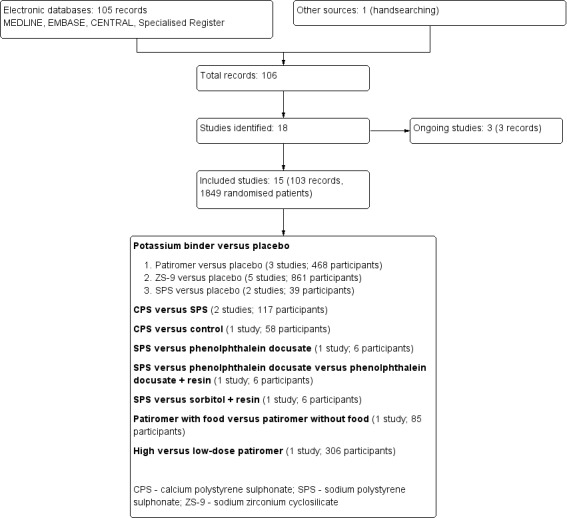

The electronic search strategy of the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register (10 March 2020) identified 105 records and handsearching identified one record (Figure 1). After initial title and abstract screening and examination of the full text, none of the retrieved records were excluded. Three studies are ongoing (DIALIZE China 2020; DIAMOND 2019; NCT03781089) and will be assessed in a future update of this review. This review therefore includes 15 studies (103 reports) randomising 1849 adults.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

The characteristics of the participants and the interventions in included studies are detailed in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Study design, setting and characteristics

Study duration varied from 12 hours to 52 weeks, with a median of 4 weeks. Three studies (Gruy‐Kapral 1998; Nakayama 2018; Wang 2018a) had a cross‐over study design in which participants were administered each of the study interventions sequentially, with or without a washout period. Studies were conducted from 1998 to 2019 in Canada (Lepage 2015), China (Wang 2018a), Japan (Kashihara 2018; Nakayama 2018), Pakistan (Nasir 2014), Europe (AMETHYST‐DN 2015), Europe and the USA (OPAL‐HK 2015), Europe, the USA, Ukraine, Russia, and Georgia (PEARL‐HF 2011), Europe, the USA, South Africa, Ukraine and Georgia (AMBER 2018), the USA (Ash 2015; Gruy‐Kapral 1998; TOURMALINE 2017), the USA, Japan, Russia and the UK (DIALIZE 2019), and the USA, Australia and South Africa (HARMONIZE 2014; Packham 2015). Fourteen studies received at least some funding from companies that manufacture potassium binders. Nasir 2014 provided no specific details about funding sources.

Study participants

Twelve studies involved participants with CKD (stages 1 to 5) not requiring dialysis. Three studies (DIALIZE 2019; Gruy‐Kapral 1998; Wang 2018a) involved participants treated with haemodialysis (HD). The sample size varied from six participants (Gruy‐Kapral 1998) to 320 participants (Packham 2015) (median of 39 participants). No studies evaluated treatment in children with CKD. The mean study age ranged from 53.1 years (Nasir 2014) to 73 years (Kashihara 2018) (median 66.8 years). Four studies (HARMONIZE 2014; Packham 2015; PEARL‐HF 2011; TOURMALINE 2017) evaluated treatment in people with CKD and heart failure, diabetes mellitus (type 1 or 2), and/or hypertension.

Interventions

Eight studies compared the more recently developed potassium binders (patiromer and ZS‐9) to placebo (AMBER 2018; Ash 2015; DIALIZE 2019; HARMONIZE 2014; Kashihara 2018; OPAL‐HK 2015; Packham 2015; PEARL‐HF 2011). Two studies compared an older potassium binder (sodium polystyrene sulphonate) to placebo (Gruy‐Kapral 1998; Lepage 2015). No studies compared calcium polystyrene sulphonate to placebo and in one study (Wang 2018a), calcium polystyrene sulphonate was compared to control. Two studies (Nakayama 2018; Nasir 2014) compared calcium polystyrene sulphonate to sodium polystyrene sulphonate. Gruy‐Kapral 1998 compared sodium polystyrene sulphonate either to laxatives or placebo. TOURMALINE 2017 evaluated administration of patiromer with compared to without food, and AMETHYST‐DN 2015 compared high‐dose to low‐dose patiromer.

There were no studies comparing newer (patiromer and ZS‐9) to older (calcium polystyrene sulphonate and sodium polystyrene sulphonate) potassium binders.

Excluded studies

No studies were excluded in this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias for studies overall are summarised in Figure 2 and the risk of bias in each individual study is reported in Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Methods for generating the random sequence were deemed to be at low risk of bias in four studies (AMETHYST‐DN 2015; Ash 2015; Lepage 2015; Wang 2018a). In the remaining 11 studies, the method for generating the random sequence was unclear.

Allocation concealment was judged to be at low risk of bias in three studies (AMBER 2018; AMETHYST‐DN 2015; DIALIZE 2019). The risk of bias for allocation concealment was unclear in the remaining 12 studies.

Blinding

Eight studies (AMBER 2018; Ash 2015; DIALIZE 2019; HARMONIZE 2014; Kashihara 2018; Lepage 2015; Packham 2015; PEARL‐HF 2011) were blinded and considered to be at low risk of bias for performance bias. The remaining seven studies were not blinded and were considered at high risk of performance bias.

As most studies were based on laboratory assessment or patient‐centred outcomes including death, 13 studies were considered at low risk of bias and two studies (Lepage 2015; Nasir 2014) were considered as high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data

Nine studies (AMBER 2018; AMETHYST‐DN 2015; Ash 2015; DIALIZE 2019; Lepage 2015; Nakayama 2018; Nasir 2014; PEARL‐HF 2011; Wang 2018a) met criteria for low risk of attrition bias. Two studies (Kashihara 2018; OPAL‐HK 2015) were considered at high risk of attrition bias as there was differential loss to follow‐up between treatment groups and high attrition rates was substantially higher in both treatment groups. In the remaining four studies, attrition bias was considered unclear. Loss to follow‐up was commonly due to withdrawal from the study, lack of available central laboratory results or adverse events.

Selective reporting

Twelve studies (AMBER 2018; AMETHYST‐DN 2015; Ash 2015; DIALIZE 2019; HARMONIZE 2014; Lepage 2015; Nakayama 2018; Nasir 2014; OPAL‐HK 2015; Packham 2015; PEARL‐HF 2011; TOURMALINE 2017) reported expected and clinically‐relevant outcomes and were deemed to be at low risk of bias. The remaining three studies did not report patient‐centred outcomes of death or adverse events.

Other potential sources of bias

One study (Lepage 2015) appeared to be free from other sources of bias. Ten studies (AMBER 2018; AMETHYST‐DN 2015; Ash 2015; DIALIZE 2019; HARMONIZE 2014; Kashihara 2018; OPAL‐HK 2015; Packham 2015; PEARL‐HF 2011; TOURMALINE 2017) were considered at high risk of bias due to the potential role of funding and for the remaining four studies the assessment of other source of bias was unclear.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings 1. Potassium binder versus placebo for chronic hyperkalaemia in people with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

| Potassium binder versus placebo for chronic hyperkalaemia in people with CKD | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD (including haemodialysis) Settings: majority of studies involved people with CKD not requiring dialysis. Only one study involved people undergoing haemodialysis Intervention: newer agents (patiromer, ZS‐9, RLY5016) or older agents (SPS, CPS) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Potassium binder | |||||

|

Death (any cause) Follow‐up: 0.29 to 14 weeks (median 9 weeks) |

6 per 1000 | 2 fewer per 1000 (5 fewer to 20 more) | RR 0.69 (0.11 to 4.32) | 688 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

low 1, 2 (CKD, 3 studies) ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2,3 (HD, 1 study) |

Potassium binder may make little or no difference to death (any cause) compared to placebo in CKD The effect of potassium binder on death (any cause) in HD is very uncertain |

|

Cardiovascular death (newer agents) Follow‐up: 10 weeks |

No events | 1/97** | RR 3.06 (0.13 to 74.24) | 196 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 4 | Studies were not designed to measure effects of potassium binder on cardiovascular death in HD |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | Not reported | Not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No studies reported this outcome |

|

HRQoL Follow‐up: 14 weeks |

The mean change in HRQoL in the potassium binder group was 2 points higher (0.22 to 3.78 points higher) than the placebo group | ‐‐ | 289 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 5 | Studies were not designed to measure effects of potassium binder on HRQoL in CKD | |

|

Serum potassium Follow‐up: 1 to 10 weeks (median 5 weeks) |

The mean serum potassium level in the placebo group ranged from 4.85 to 5.70 mg/dL The mean serum potassium level in the phosphate binder group was 0.62 mg/dL lower (0.97 to 0.27 mg/dL lower) |

‐‐ | 277 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1, 6 (CKD and HD, 2 studies and 1 study, respectively) | Potassium binders may lower serum potassium levels compared to placebo or no treatment in CKD and HD Additional comments 1) Serum potassium ‐ newer agents (patiromer, ZS‐9, RLY5016) Follow‐up: 8 to 10 weeks (median 9 weeks) The mean serum potassium level ranged across control groups from 4.85 to 5.70 mg/dL The mean serum potassium level with newer agents was 0.45 mg/dL lower (0.71 to 0.19 mg/dL lower) 2) Serum potassium ‐ older agents (SPS, CPS) Follow‐up: 1 week The mean serum potassium level in the control arm was 5.03mg/dL The mean serum potassium level with the older agents was 1.04 mg/dL lower (1.37 to 0.71 mg/dL lower) |

|

|

Constipation Follow‐up: 0.29 to 10 weeks (median 4.5 weeks) |

36 per 1000 | 21 more per 1000 (10 fewer to 90 more) |

RR 1.58 (0.71 to 3.52) |

425 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

low 1,2 (CKD, 3 studies) ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2,3 (HD, 1 study) |

Potassium binder may make little or no difference to constipation compared to placebo in CKD It is very uncertain the effect of potassium binder on constipation in HD |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CPS: calcium polystyrene sulphonate; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life; RR: risk ratio; SPS: sodium polystyrene sulphonate | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence ** Event rate derived from the raw data. A 'per thousand' rate is non‐informative in view of the scarcity of evidence and zero events in the control group. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. Most studies had unclear risks for sequence generation and allocation concealment and some studies were not blinded (participants and/or investigators)

2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to imprecision

3 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to indirectness population

4 Cardiovascular death was reported by as a single study

5 HRQoL was reported by as a single study

6 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to substantial between‐study heterogeneity

Summary of findings 2. Calcium polystyrene sulphonate (CPS) versus sodium polystyrene sulphonate (SPS) for chronic hyperkalaemia in people with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

| CPS versus SPS for chronic hyperkalaemia in people with CKD | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD Settings: all studies involved people with CKD not requiring dialysis Intervention: CPS Comparison: SPS | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Sodium polystyrene sulphonate (SPS) | Calcium polystyrene sulphonate (CPS) | |||||

| Death (any cause) | Not reported | Not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No studies reported this outcome |

| Cardiovascular death | Not reported | Not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No studies reported this outcome |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | Not reported | Not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No studies reported this outcome |

| HRQoL | Not reported | Not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No studies reported this outcome |

|

Serum potassium Follow‐up: 0.43 to 4 weeks (median 2.2 weeks) |

The mean serum potassium level in the SPS group ranged from 4.12 to 4.30 mg/dL The mean serum potassium level in the CPS group was 0.38 mg/dL higher (0.03 lower to 0.79 mg/dL higher) |

‐‐ | 117 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1, 2 | CPS may make little or no difference to serum potassium level compared to SPS | |

|

Constipation Follow‐up: 0.43 weeks |

170 per 1000 | 51 fewer per 1000 (126 fewer to 150 more) |

RR 0.70 (0.26 to 1.88) | 97 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 3 | Studies were not designed to measure effects of CPS or SPS on constipation |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CPS: calcium polystyrene sulphonate; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life; RR: risk ratio; SPS: sodium polystyrene sulphonate | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. All studies had unclear risks for random sequence generation and allocation concealment and were not blinded (participants and/or investigators)

2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to moderate between‐study heterogeneity

3 Constipation was reported by as a single study

Summary of findings 3. High versus with low‐dose potassium binder for chronic hyperkalaemia in people with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

| High versus with low‐dose potassium binder for chronic hyperkalaemia in people with CKD | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD Settings: all studies involved people with CKD not requiring dialysis Intervention: high‐dose potassium binder Comparison: low‐dose potassium binder | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Low‐dose potassium binder | High‐dose potassium binder | |||||

| Death (any cause; sudden death) | 10 per 1000 | 9 more per 1000 (8 fewer to 201 more) | RR 1.94 (0.18 to 21.08) | 203 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1 | Studies were not designed to measure effects of high‐dose potassium binder on death (any cause) |

| Cardiovascular death | Not reported | Not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No studies reported this outcome |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | Not reported | Not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No studies reported this outcome |

| HRQoL | Not reported | Not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No studies reported this outcome |

| Serum potassium | Not reported | Not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No studies reported this outcome |

|

Constipation Follow‐up: 53 weeks |

60 per 1000 | 28 more per 1000 (28 fewer to 176 more) | RR 1.46 (0.54 to 3.94) | 203 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 2 | Studies were not designed to measure effects of high dose potassium binder on constipation |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Death (any cause; sudden death) was reported by as a single study

2 Constipation was reported by a single study

Potassium binder versus placebo

Ten studies (AMBER 2018; Ash 2015; DIALIZE 2019; Gruy‐Kapral 1998; HARMONIZE 2014; Kashihara 2018; Lepage 2015; OPAL‐HK 2015; Packham 2015; PEARL‐HF 2011) involving 1367 randomised participants compared a potassium binder to placebo. The median follow‐up was 3.4 weeks. The certainty of the evidence was low for all outcomes (Table 1) in CKD and low or very low in HD.

Newer potassium binders (patiromer or ZS‐9) may make little or no difference to all‐cause death (any cause) in CKD (Analysis 1.1 (4 studies, 688 participants): RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.11 to 4.32; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence), and DIALIZE 2019 (196 participants) reported no difference between potassium binders and placebo for cardiovascular death in people requiring HD (Analysis 1.2.1 (1 study, 196 participants): RR 3.06, 95% CI 0.13, 74.24). The treatment effect of older potassium binders (calcium polystyrene sulfonate or sodium polystyrene sulfonate) on death (any cause) and cardiovascular death was uncertain, as these outcomes were not reported.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 1: Death (any cause)

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 2: Cardiovascular death

Potassium binders had uncertain effects on nausea (Analysis 1.3 (3 studies, 229 participants): RR 2.10, 95% CI 0.65 to 6.78; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence), diarrhoea (Analysis 1.4 (5 studies, 720 participants): RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.48; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence), vomiting (Analysis 1.5 (2 studies, 122 participants): RR 1.72, 95% CI 0.35 to 8.51; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence) and constipation (Analysis 1.6 (4 studies, 425 participants): RR 1.58, 95% CI 0.71 to 3.52; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence) in CKD. Ash 2015 reported no difference between potassium binders and placebo for abdominal pain (Analysis 1.7 (1 study, 90 participants): RR 1.52, 95% CI 0.06 to 36.34) in CKD.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 3: Nausea

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 4: Diarrhoea

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 5: Vomiting

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 6: Constipation

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 7: Abdominal pain

Potassium binders may lower serum potassium levels at the end of treatment (Analysis 1.8 (3 studies, 277 participants): MD ‐0.62 mEq/L, 95% CI ‐0.97 to ‐0.27; I2 = 92%; low certainty evidence) in CKD and HD, and may favourably change serum potassium levels during treatment (Analysis 1.9 (2 studies, 105 participants): MD ‐0.75 mEq/L, 95% CI ‐1.27 to ‐0.23; I2 = 90%; low certainty evidence) in CKD. There was substantial statistical heterogeneity in the treatment effects between studies.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 8: Serum potassium

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 9: Change in serum potassium

Potassium binders may make little or no difference to hypokalaemia (Analysis 1.10 (2 studies, 228 participants): RR 1.71, 95% CI 0.31 to 9.47; I2 = 34%; low certainty evidence), and hospitalisation (Analysis 1.11 (3 studies, 522 participants): RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.32; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence) in CKD and HD. DIALIZE 2019 reported no difference between potassium binders and placebo for angina pectoris (Analysis 1.12 (1 study, 196 participants): RR 5.10, 95% CI 0.25 to 104.92) and infection (Analysis 1.13 (1 study, 196 participants): RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.60 to 3.08) in HD.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 10: Hypokalaemia

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 11: Hospitalisation

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 12: Angina pectoris

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 13: Infection

Potassium binders may decrease systolic BP (Analysis 1.14 (2 studies, 369 participants): MD ‐3.73 mmHg, 95% CI ‐6.64 to ‐0.83; I2 = 79%; low certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.15 (1 study, 74 participants): MD ‐5.49 mmHg, 95% CI ‐6.32 to ‐4.66), with substantial statistical heterogeneity in the treatment effects between studies, and diastolic BP (Analysis 1.16 (1 study. 74 participants): MD ‐2.65 mmHg, 95% CI ‐3.44 to ‐1.86) (Analysis 1.17 (1 study, 74 participants): MD ‐3.87 mmHg, 95% CI ‐4.42 to ‐3.32) in CKD.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 14: Systolic blood pressure

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 15: Change in systolic blood pressure

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 16: Diastolic blood pressure

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 17: Change in diastolic blood pressure

AMBER 2018 reported no difference between potassium binders and placebo for HRQoL at end of treatment (Analysis 1.18 (1 study, 189 participants): EuroQoL score MD 2.60, 95% CI 0.04, 5.16) and change HRQoL (Analysis 1.19 (1 study, 189 participants): EuroQoL score MD 2.00, 95% CI 0.22 to 3.78) in CKD.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 18: HRQoL

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 19: Change in Health‐related QoL

DIALIZE 2019 reported no difference between potassium binders and placebo for shunt stenosis (Analysis 1.20 (1 study, 196 participants): RR 0.34 (95% CI 0.04 to 3.21) and kidney transplantation (Analysis 1.21 (1 study, 196 participants): RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.25) in HD.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 20: Shunt stenosis

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Potassium binder versus placebo, Outcome 21: Kidney transplantation

There were no available data for the outcomes of cardiac arrhythmia or major GI events.

Calcium polystyrene sulfonate versus sodium polystyrene sulfonate

Two studies (Nakayama 2018; Nasir 2014) involving 117 participants compared calcium polystyrene sulfonate with sodium polystyrene sulfonate in CKD. Studies were not designed to evaluate the outcomes specified in this systematic review. The certainty of the evidence was low for all reported outcomes (Table 2).

Nasir 2014 reported calcium polystyrene sulfonate may increase nausea (Analysis 2.1 (1 study, 97 participants): RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.83) compared to sodium polystyrene sulfonate, while reported no difference between calcium polystyrene sulfonate and sodium polystyrene sulfonate for diarrhoea (Analysis 2.2 (1 study, 97 participants): RR 2.82, 95% CI 0.12 to 67.64), vomiting (Analysis 2.3 (1 study, 97 participants): RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.01 to 3.82), constipation (Analysis 2.4 (1 study, 97 participants): RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.88), and abdominal pain (Analysis 2.5 (1 study, 97 participants): RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.91).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Calcium polystyrene sulfonate (CPS) versus sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), Outcome 1: Nausea

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Calcium polystyrene sulfonate (CPS) versus sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), Outcome 2: Diarrhoea

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Calcium polystyrene sulfonate (CPS) versus sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), Outcome 3: Vomiting

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Calcium polystyrene sulfonate (CPS) versus sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), Outcome 4: Constipation

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Calcium polystyrene sulfonate (CPS) versus sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), Outcome 5: Abdominal pain

Calcium polystyrene sulfonate may make little or no difference to serum potassium levels at the end of treatment compared to sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Analysis 2.6 (2 studies, 117 participants): MD 0.38 mEq/L, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.79; I2 = 42%; low certainty evidence). There was moderate statistical heterogeneity in the treatment effects between studies.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Calcium polystyrene sulfonate (CPS) versus sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), Outcome 6: Serum potassium

Nasir 2014 reported no difference in systolic BP (Analysis 2.7 (1 study, 97 participants): MD 2.65 mmHg, 95% CI ‐4.79 to 10.09) and diastolic BP (Analysis 2.8 (1 study, 97 participants): MD ‐4.30 mmHg, 95% CI ‐9.32 to 0.72) at the end of treatment, between calcium polystyrene sulfonate and sodium polystyrene sulfonate.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Calcium polystyrene sulfonate (CPS) versus sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), Outcome 7: Systolic blood pressure

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Calcium polystyrene sulfonate (CPS) versus sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), Outcome 8: Diastolic blood pressure

Data were not available for death (any cause or cardiovascular), cardiac arrhythmias, and HRQoL.

Calcium polystyrene sulfonate versus control

Wang 2018a (58 participants) evaluated calcium polystyrene sulfonate versus control for three weeks. No data were available for any of our review outcomes.

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate versus phenolphthalein docusate

Gruy‐Kapral 1998 (6 participants) evaluated sodium polystyrene sulfonate versus phenolphthalein docusate during a 12‐hour experiment. No data were available for any of our review outcomes.

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate versus phenolphthalein docusate versus phenolphthalein docusate + resin

Gruy‐Kapral 1998 (6 participants) evaluated sodium polystyrene sulfonate versus phenolphthalein docusate plus resin during a 12‐hour experiment. No data were available for any of our review outcomes.

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate versus sorbitol + resin

Gruy‐Kapral 1998 (6 participants) evaluated sodium polystyrene sulfonate versus sorbitol plus resin during a 12‐hour experiment. No data were available for any of our review outcomes.

Patiromer with food versus patiromer without food

TOURMALINE 2017 (85 participants) compared patiromer with food with patiromer without food for 4 weeks. No data were available for any of our review outcomes.

High‐dose versus low‐dose patiromer

AMETHYST‐DN 2015 compared high‐dose with low‐dose of patiromer for 52 weeks (Table 3) in CKD. They reported no difference between high‐ and low‐dose patiromer for death (any cause; sudden death) (Analysis 3.1 (1 study, 203 participants): RR 1.94, 95% CI 0.18 to 21.08) sudden death, while high‐dose patiromer may increase diarrhoea (Analysis 3.2 (1 study, 203 participants): RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.97) compared to low‐dose patiromer. AMETHYST‐DN 2015 reported no difference between high‐dose and low‐dose patiromer for constipation (Analysis 3.3 (1 study, 203 participants): RR 1.46, 95% CI 0.54 to 3.94), hypokalaemia (Analysis 3.4 (1 study, 203 participants): RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.20 to 4.70), stroke (Analysis 3.5 (1 study, 203 participants): RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.31) and myocardial infarction (Analysis 3.6 (1 study, 203 participants): RR 2.91, 95% CI 0.12 to 70.68).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: High dose potassium binder versus low dose potassium binder, Outcome 1: Death (any cause)

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: High dose potassium binder versus low dose potassium binder, Outcome 2: Diarrhoea

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: High dose potassium binder versus low dose potassium binder, Outcome 3: Constipation

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: High dose potassium binder versus low dose potassium binder, Outcome 4: Hypokalaemia

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3: High dose potassium binder versus low dose potassium binder, Outcome 5: Stroke

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3: High dose potassium binder versus low dose potassium binder, Outcome 6: Myocardial infarction

Data were not available for cardiovascular death, cardiac arrhythmias, HRQoL, and serum potassium level.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We identified 15 studies randomising 1849 adult participants with CKD evaluating potassium binders for chronic hyperkalaemia (defined either as > 5 or > 5.5 mmol/L). Most studies (10 studies randomising 1367 participants) compared a potassium binder with placebo for a median of 3.4 weeks. Data for clinical outcomes included in this review were available in five of these 10 studies. Potassium binders for chronic hyperkalaemia reduce serum potassium levels compared with placebo in patients with CKD. In low or very low certainty evidence, it is uncertain whether potassium binders have effects on death (any cause or cardiovascular) and GI events. Potassium binders were also compared to no treatment, laxatives, sorbitol, a second binder, and the administration with and without food. Meta‐analysis was not possible for any of our review outcomes for these compared treatments, since single studies available did not address outcomes of our interest. The comparative effects of different doses of potassium binder is very uncertain.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

For this review, we identified 15 studies comparing different potassium binders approaches for patients with CKD, and the information from these studies is of insufficient certainty to inform clinical care or policy. Very few studies were in dialysis setting or compared different treatment doses and often the appropriateness of the dosage were not clearly reported. High‐dose patiromer was associated with more adverse events, although it decreased the potassium concentration. Most studies compared potassium binders with placebo, and outcome data were rarely reported or missing. All studies had small sample sizes (6 to 320 participants), were often short‐term, had methodological limitations, were a cross‐over design, or were primarily designed to evaluate surrogate measures of effect. No study reported outcome data for cardiac arrhythmias and withdrawal from BP‐lowering therapy. The short duration of the majority of included studies precluded the assessment of cardiovascular outcomes, including those potentially deriving from discontinuation or under dosing of demonstrably beneficial RAAS inhibitors, especially in proteinuric patients with CKD or concomitant heart failure. No study was designed to assess key patient outcomes, and potential adverse events related to treatment are not well understood or systematically reported. Standardisation of outcome reporting in future potassium binders studies as prioritised by the Standardised Outcomes in Nephrology (SONG 2017) by patients, caregivers and health professionals may assist to improve the evidence base for potassium binder therapy studies. Consistent measures for study outcomes would improve our confidence in the results of available studies.

Quality of the evidence

We used standard risks of bias domains within the Cochrane tool together with GRADE methodology (GRADE 2008) to assess the quality of study evidence. Since confidence in the evidence for death (any cause and cardiovascular), cardiac arrhythmias, and HRQoL were uncertain or could not be estimated, further studies might provide different results. Some studies were at high or unclear risks of bias for most of risk domains assessment, limiting the certainty of the evidence. We noted that four studies were at low risk of random sequence generation and three studies were at low risk of allocation concealment. Blinding of participants and investigators and outcome assessment were at low risk of bias in eight and 13 studies, respectively. Nine studies were at low risk methods for attrition, 12 studies were at low risk of selective reporting, and one study was at low risk of other potential sources of bias. The overall certainty of the evidence was assessed as low or very low certainty for all outcomes for which there were extractable data.

In this review, clinical outcomes were rarely available for many of the treatments. The variabilities of reporting methods in the individual studies hamper the data summary. Moderate or substantial heterogeneity in definitions and methods of reporting serum potassium levels and systolic BP were particularly relevant. The limited number of studies prevented exploration of other potential sources of heterogeneity in the analyses. Subgroup and sensitivity analysis could not be done for heterogeneity owing to insufficient data. Due to the limited number of studies and participants, it was not clear if there was a difference between the evidence from older to newer potassium binders. Since data were sparse, the assessment of adverse events in both treatments categories was not possible. All studies reported SD or SE as estimate of variance and some of them provided data in descriptive or figure format only.

Potential biases in the review process

This review was carried out using standard Cochrane methods. Each step was completed independently by at least two authors including selection of studies, data management, and risk of bias assessment, thus reducing the risks of errors in identification of eligible studies and adjudication of evidence certainty. A highly sensitive search of the Cochrane Kidney Transplant specialised register was last undertaken without language restriction in March 2020. The registry contains hand‐searched literature and conference proceedings, maximising the inclusion of grey literature in this review. We additionally requested data from authors. Many studies did not report key outcomes in a format available for meta‐analysis.

In this review the data availability in the individual studies were a potential source of bias. First, there was heterogeneity between treatment interventions and robust statistical estimates could not be estimated, due to the small number of included studies. Second, most studies were at high risks of bias, but poorer quality studies could not be excluded due to the small number of data observations. The limited number of studies was a constraint on our ability to assess for potential reporting bias and selective outcome reporting. Third, the definition of kidney disease varied across the eligible studies, although most participants had CKD (stage 1 to 5) not requiring dialysis. Fourth, the effects of potassium binder interventions on longer‐term outcomes is uncertain and the treatment endpoints were principally surrogate markers of health (BP, serum potassium). Finally, adverse event reporting was rarely provided.

Formal assessment for publication bias through visualisation of asymmetry in funnel plots was precluded for all treatments and outcomes because of few studies.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Few studies have examined the efficacy of potassium binders for people with CKD and the number of meta‐analysis published in this field is limited. The current Cochrane review is consistent with the findings of systematic review and meta‐analysis of published RCTs evaluating the efficacy and safety of patiromer for treating hyperkalaemia in patients with CKD or heart failure (Das 2018). In that review that included three studies, the authors found that there was a reduction of serum potassium with patiromer compared to placebo. Patiromer compared with placebo did not show a significant reduction in death risk (any cause) and serious cardiovascular events. In a second meta‐analysis of both RCTs and observational studies, dietary education significantly reduced the prevalence of hyperkalaemia and serum potassium, compared with control (Palaka 2018). In that analysis, the population of interest was not restricted to chronic hyperkalaemia in CKD, the interventions were both pharmacological and non‐pharmacological, observational studies were included, and GRADE was not used to evaluate evidence certainty.

A single large RCT, evaluating the effect of ZS‐9 in 320 patients with hyperkalaemia, reported a significant reduction in potassium levels compared with placebo (Packham 2015). In a previous Cochrane review of pharmacological interventions for the acute management of hyperkalaemia in adults (7 studies, 241 participants), salbutamol and other medications were safe and well‐tolerated, and may decrease serum potassium levels. There was very low certainty about whether medications made any difference to reduce death and cardiac arrhythmias compared to placebo (Batterink 2015). Potassium binders decreased serum potassium but did not improve death, cardiovascular events, or HRQoL.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Potassium binders reduce serum potassium level compared to placebo among people with CKD, although there is low certainty evidence on all‐cause and cardiovascular death, cardiac arrhythmias and HRQoL. No data for treatment effects in children were identified. There is scant evidence to inform decision‐making about newer potassium binders or the comparative effectiveness and safety between older and newer treatments. Evidence is largely lacking in the setting of peritoneal dialysis, HD, home‐based HD, or transplantation. The potential adverse effects of treatment are largely unknown ‐ in particular, major GI events.

Implications for research.

Future adequately powered, rigorous RCTs are needed to assess the benefits and potential harms of potassium binders, including determining if their use will lead to maximizing the concomitant administration of RAAS inhibitors to improve clinical outcomes in people with CKD treated for chronic hyperkalaemia. More recent studies seem to be more promising and could show sufficient statistical power to detect treatment effects on important patient outcomes (including death, cardiovascular, and major GI adverse events). Further research is likely to change the estimated effects of treatments for chronic hyperkalaemia. Future potassium binder studies compared with placebo will increase our certainty of the evidence based on limitations in existing studies and a paucity of evidence in the CKD setting.

Evaluation of cost‐effectiveness for potassium binders approaches in CKD setting would assist decision‐making by policy‐makers and health care providers.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 11, 2018 Review first published: Issue 6, 2020

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editorial team of Cochrane Kidney Transplant for guidance and support throughout this protocol process. We would like to thank the editor and reviewers of this protocol and review.

The authors are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their time and comments: Kwek Jia Liang (Consultant, Department of Renal Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore), George L Bakris MD (Professor of Medicine, Director, Am. Heart Assoc. Comprehensive Hypertension Center, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA), Stephen Walsh (Associate Professor in Experimental Medicine and Honorary Consultant Nephrologist, UCL Department of Renal Medicine, University College London, London, UK), Michael Emmett MD (Department of Internal Medicine, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, USA).

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL |

|

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimisation (minimisation may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random). |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes). |