Abstract

Entry rates into self-employment increase during recessions and decrease during economic upswings. I show that this is mostly explained by the higher unemployment rate during a recession, together with the fact that at all times, unemployed persons have a relatively high propensity to become self-employed out of necessity. I use econometric decomposition techniques to quantify these effects based on the monthly matched US Current Population Survey before, during, and after the Great Recession. I also document that the entry rate into self-employment with unincorporated businesses strongly increased during the recession, but not into self-employment with incorporated businesses. This highlights the association of unincorporated and incorporated self-employment with necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship, respectively. The results are useful for policymakers and practitioners to understand, forecast and act on the different types of self-employment that can be expected over the business cycle. There are also important implications for theories of the cyclicality of unemployment and entrepreneurship.

Plain English Summary Self-employment will increase during recessions when unemployment is high, but it may not boost innovation. During recessions, increased unemployment underlies the higher entry rate into self-employment. Our evidence is from representative survey data from the USA covering the Great Recession. The upside is that self-employment enables workers who lose their jobs to continue to work, which can speed up the subsequent economic recovery. Thus, public policy should enable people to start businesses. However, as during recessions the unemployed mostly start unincorporated businesses, one cannot expect them to boost innovation as much as start-ups during better economic times. These insights also speak to the 2020 recession triggered by COVID-19. If unemployment remains high after the relaxation of the lockdowns, a rise can be expected especially in non-innovative self-employment. Thus, the principal policy implication of this study is that policymakers should ensure that their expectations for new businesses started during deep recessions are realistic for the circumstances.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11187-020-00375-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Self-employment, Entrepreneurship, Great Recession, Unemployment, Opportunity, Necessity, Decomposition

Introduction

Entry rates into self-employment are higher in recessions than in boom periods. In particular, the entry rate increased during the Great Recession (Fairlie 2013). How much of this higher entry rate in a recession is explained by the higher unemployment rate and a generally higher individual propensity to start up out of unemployment? Alternatively, recession periods could be fundamentally different from boom periods in the sense that individual characteristics such as unemployment status have very different effects on entry into self-employment at different stages of the business cycle. Policymakers and practitioners need insights to understand, forecast and act on the dynamics of entry into self-employment over the cycle.

Theoretical models of unemployment, entrepreneurship and the business cycle (Faria et al. 2009; Faria 2015) posit that high unemployment during a recession increases entry into entrepreneurship, and a fraction of these new entrepreneurs will introduce innovation, which lifts the economy into the next boom period. The boom reduces unemployment and entry into entrepreneurship, which leads to reduced innovation and the next recession. Thus, these models offer an explanation for business cycles. In this empirical paper, the first working hypothesis to be tested, in line with these models, is this: The change in the individual probability of entry into self-employment when the economy moves in and out of the recession is mostly explained by the change in unemployment.

These theoretical models assume that the propensity to innovate is homogeneous among entrepreneurs. However, unemployment pushes individuals into self-employment because they experience difficulties in finding paid employment (unemployment-push hypothesis). Those who become self-employed out of unemployment due to a lack of alternatives can be referred to as necessity entrepreneurs (Fairlie and Fossen 2019). To capture different motivations and aspirations, such as necessity versus opportunity motives for self-employment, I follow Levine and Rubinstein (2017) and distinguish between self-employed individuals starting unincorporated and incorporated businesses, where the latter can be expected to be more innovative. The second working hypothesis in this paper is that the change in the entry rate into unincorporated self-employment is explained by changes in unemployment, but the change in the entry rate into incorporated self-employment is not. The empirical results from this analysis are consistent with both hypotheses. Consequently, the higher entry rate into self-employment during a recession cannot necessarily be expected to lead to accelerated innovation and the next boom period. This implies that theoretical models in this context should incorporate the heterogeneity among the self-employed.

This paper contributes to the empirical literature by quantifying how much of the higher entry rate into total and different types of self-employment during a recession can be explained by changes in the unemployment rate. The analysis is based on representative individual-level rotating panel data for the USA, the monthly matched Current Population Survey (CPS). I start from the observation that the monthly entry rate into self-employment was higher during the Great Recession than before or after. I estimate that individual unemployment status increases the monthly probability of becoming self-employed by about 0.9 percentage points and establish that this effect is almost constant over the business cycle. This is the first study that provides an econometric decomposition of the entry rate into self-employment during different phases of the business cycle into an explained and an unexplained component. The results show that individual unemployment alone explains almost the entire increase in the entry rate into self-employment during the recession. I further document that the changes in self-employment over the cycle are almost completely driven by changes in unincorporated self-employment, which is much more responsive to unemployment than incorporated self-employment.

These results have important implications for economic policy, as they suggest that high rates of entry into self-employment during recessions cannot necessarily be expected to lead to economic recovery and a new boom through entrepreneurial innovation. For theory development, the findings imply that models explaining the business cycle through unemployment and entrepreneurial dynamics must be refined to take into account the heterogeneity of self-employment and the composition changes within self-employment over the business cycle.

In contrast to most of the literature, I explicitly distinguish between unemployment, which captures that an individual is looking for work, and non-participation in the labor market.1 The results indicate that non-participation increases the probability of an individual to become self-employed during all phases of the business cycle, similarly to unemployment. However, in contrast to unemployment, non-participation did not change much over the Great Recession. Therefore, only unemployment, but not non-participation, explains the changing entry rate into self-employment over the recession. This insight will help to make theory development, empirical research, and forecasts of self-employment more precise.

I also explore potential moderators of the relationship between unemployment and entry into self-employment: formal education and residency of an individual in a metropolitan area. I document that unemployed individuals with some college education or a college degree are most likely to become self-employed with an incorporated business, whereas unemployed individual with less than high school education are more likely to become self-employed with an unincorporated business. The additional insight is that a higher entry rate into self-employment triggered by increasing unemployment among low-skilled workers can be characterized as necessity entrepreneurship with relatively low innovation potential.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a review of the relevant empirical literature. Section 3 explains the econometric methods I employ, in particular the nonlinear Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition of the entry rate into self-employment. Section 4 describes the rotating monthly panel data I use. Section 5 presents the empirical results and extensive robustness checks, and Section 6 provides a discussion and concludes the analysis.

Review of the empirical literature

The literature discussing how economic circumstances may influence the entry rate into self-employment distinguishes between the unemployment-push effect mentioned above and a prosperity-pull effect. The unemployment-push effect describes that unemployed individuals are more likely to become self-employed in order to escape unemployment (e.g., Audretsch and Vivarelli 1996), which is sometimes also called a ‘refugee effect’ (Thurik et al. 2008). A prosperity-pull effect occurs when an economic boom period increases self-employment because of a high demand for products and services as well as potentially lower bankruptcy risk and, therefore, higher availability of capital (Storey 1991; Brünjes and Diez 2013). Correspondingly, a recession may lead to a reverse prosperity-pull effect and decrease entry into self-employment.

Consistent with this expectation, Bartz and Winkler (2016) provide evidence showing that the growth of young firms slowed down more than the growth of older firms in Germany during the Great Recession, and Lee and Mukoyama (2015) report that entry rates of manufacturing plants are higher in booms than in recessions in the USA. Self-employment is also riskier during a recession because the option to fall back into paid employment if the business fails is more difficult. Empirical studies relating unemployment rates to self-employment rates using aggregate data cannot separate the unemployment-push effect from the reverse prosperity-pull effect and estimate a net effect, as noted by Parker (2018).2 By using individual-level data, I can identify the unemployment-push effect separately from the reverse prosperity-pull effect because the former effect works through an individual’s unemployment status, whereas the latter effect works at the aggregate level and affects both unemployed and employed persons considering to become self-employed.

Most of the existing empirical literature on the relationship between the dynamics of self-employment and unemployment is based on time-series or country-level panel data analysis (e.g., Parker and Robson 2004). Using industry- and region-level panel data, Konon et al. (2018) find that start-up rates move mostly with the unemployment rate in Germany, except in innovative industries with a small minimum efficient establishment size. Congregado et al. (2012) conclude from their time-series analysis that employer self-employment rates evolve pro-cyclically whereas own-account self-employment rates evolve counter-cyclically in Spain. They do not find significant associations in the USA but call for alternative measures of entrepreneurship, which I respond to by distinguishing between unincorporated and incorporated self-employment.

Time-series studies by Faria et al. (2010) and Parker et al. (2012) indicate that self-employment responds rapidly and substantially to cycles in unemployment. These results also suggest that entrepreneurship may in turn affect unemployment by creating (or destroying) jobs, although the effect of entrepreneurship on unemployment is estimated to be weaker and occur with a time lag (see also Fritsch and Noseleit 2013). In this paper, I focus on the contemporaneous effect of individual unemployment on the probability of becoming self-employed, not the potential delayed effect of self-employment on unemployment rates (see, e.g., Thurik et al.2008). Koellinger and Thurik (2012) estimate a Vector Auto Regression (VAR) model using a panel of annual country-level data from 22 OECD countries over the period 1972–2007. The results suggest that entrepreneurship forecasts unemployment downswings one year in advance. Parker et al. (2012) find similar results from a VAR estimation using quarterly aggregate data from the UK. These authors also report that accounting for structural breaks can change results. I explicitly allow for the possibility of structural breaks by estimating separate coefficients for different phases of the business cycle based on individual-level panel data.

Most studies using aggregate data can only consider the net entry rate, which is the difference between the entry and exit rates, whereas I can specifically estimate effects on the individual probability of entry into self-employment. For example, if unemployment increases the probability of entry, but start-ups out of unemployment also exhibit higher failure rates, an aggregate analysis might not measure any effect of the unemployment rate on the net entry rate, whereas my microdata approach would reveal the higher entry rate into self-employment at times of high unemployment.

Analyses based on individual-level data are not only in a better position to separately identify the unemployment-push effect, as mentioned above; they can also control for educational attainment and therefore distinguish effects of unemployment from effects of low levels of human capital. Papers using microdata predominantly find a positive relationship between individual unemployment and entrepreneurship, which is consistent with the unemployment-push hypothesis (Ritsilä and Tervo 2002; Berglann et al. 2011; Åstebro et al. 2011; Biehl et al. 2014; Fritsch et al. 2015). However, studies analyzing changing patterns of transitions into self-employment within business cycles based on individual-level panel data are very scarce. Using the CPS, Fairlie (2013) finds that higher unemployment rates push individuals into self-employment, especially out of non-employment, which is a sign of necessity entrepreneurship. He does not distinguish between unincorporated and incorporated self-employment. None of the existing empirical studies decompose the change in the entry rate into self-employment over the cycle into explained and unexplained components and quantify how much individual unemployment contributes to explaining the higher entry rate during a recession. This paper closes this gap in the literature by showing that individual unemployment mostly explains the higher entry rate into self-employment during the Great Recession, and that the additional entry flows mostly into self-employment with unincorporated businesses. Regarding an individual’s decision to become self-employed, recessions are not fundamentally different from boom periods and do not change the probability of individuals to become self-employed conditional on their individual characteristics.

Methodological approach: nonlinear decomposition

The goal of the empirical analysis is to decompose the change in the entry rate into self-employment over the business cycle into an explained and an unexplained component, and in particular to estimate how much individual unemployment contributes to explaining the change in the entry rate. To achieve this, I first estimate logit models of the probability of becoming self-employed separately for different periods before, during, and after the Great Recession (GR). The binary outcome variable entry(i,t+ 1) equals 1 if individual i enters into self-employment between months t and t + 1, and 0 otherwise. The latent index function of the logit model is written as

| 1 |

where entry∗ is the propensity to enter into self-employment, X is a vector of explanatory variables including dummy variables indicating individual unemployment status and non-participation, β is a coefficient vector including a constant, and 𝜖 is the error term. Second, I decompose the change in the mean entry probability between periods into a part explained by changes in observed individual variables, including unemployment status and non-participation, and an unexplained part reflected in changes in the coefficients and the intercept. The detailed decomposition method allows assessing the contribution of each variable of interest separately.

All the explanatory variables are observed in the month before a potential entry into self-employment occurs. Among the variables in X, the main interest is in the individual unemployment status. To identify the effect ceteris paribus, I control for individual determinants of self-employment known from the literature (e.g., Parker2018). It is particularly important to control for educational attainment because of its negative correlation with unemployment. I include an individual’s highest educational degree obtained, age (linear and squared), gender, race, marital status, number of children, region of residence, and a dummy variable indicating whether the respondent lives in a metropolitan area. While I am able to control for the standard individual variables used in the literature on self-employment choice, I might still miss relevant variables, which would increase the unexplained part in the decomposition analysis.

I implement an adaption of the decomposition approach originally suggested by Oaxaca (1973) and Blinder (1973); Fortin et al. (2011) provide an overview. Since the outcome variable is binary and I estimate logit models, I apply the weighting method for nonlinear models as described by Yun (2004), which allows for a detailed decomposition by single variables as well as coefficients.3 In my context, the index problem discussed in the econometric decomposition literature pertains to whether the coefficients estimated for the GR period or for the comparison period should be used to assess the contribution of the variables to the change in the entry rate into self-employment. I follow Neumark (1988) and Oaxaca and Ransom (1994) and use the coefficients from an estimation of the logit model of entry based on the pooled sample including both periods. I also include a dummy variable indicating the GR period in the pooled model, as generally recommended by Jann (2008) in order to avoid a potential spillover from the unexplained part of the differential into the explained component. Furthermore, I normalize categorical variables, i.e., the educational degree, race, and regional dummy variables. As a result, effects are expressed as deviations from the overall mean, and the detailed decomposition results do not depend on the choice of an otherwise arbitrarily omitted base category (Yun 2005). I describe this variant of a nonlinear decomposition formally in Online Appendix A (see also Caliendo et al.2014).

In an extension of the analysis, I explore which socio-economic and regional conditions strengthen or weaken the effects of unemployment on the probability of entry into self-employment. I do so by including interaction terms of the unemployment dummy with potential moderators in Eq. (1). Due to the well-known correlations of both unemployment and self-employment with formal education and the potential relevance of agglomeration effects (Parker 2018), I consider effect heterogeneity with respect to an individual’s educational attainment and residence in a metropolitan versus rural area. I estimate these additional models using OLS instead of logit to facilitate the interpretation of the coefficients of the interaction terms.

Data

Representative panel data

For the empirical analysis, I use the monthly waves of the Current Population Survey (CPS) from January 2004 to December 2014, i.e., before, during, and after the GR. The CPS is a representative survey of households in the USA provided by the Census Bureau. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics relies on the CPS to estimate the widely reported national unemployment rate. The CPS follows a rotating survey design. Households are interviewed in four consecutive months, then pause for eight months, and then are surveyed again in four more consecutive months. I use the IPUMS-CPS (Flood et al. 2017), which merges these consecutive observations at the individual level to construct rotating panel data. The first three months of each four-month survey spell can be linked to the subsequent month, so 75% of all observations can be connected to the following month. Thus, for each individual, I include a maximum of six monthly observations with information on subsequent labor market transitions in the estimation sample.

Self-employment is commonly used to operationalize entrepreneurship in empirical research. This paper highlights that it is important to take into account the heterogeneity of the self-employed and that equating dynamic patterns of total self-employment rates to innovative entrepreneurship can be misleading. As mentioned before, I follow Levine and Rubinstein (2017) and distinguish between self-employed individuals starting unincorporated and incorporated businesses. On average, the self-employed with incorporated businesses tend to be closer to the concept of an innovative, growth-oriented entrepreneur than the self-employed with unincorporated businesses (see also Shane 2014; Herranz et al.2017).

The panel data structure of the matched CPS allows me to observe entries into self-employment from one month to the next based on questions about the current employment status in two consecutive months. Respondents are asked: “Last week, were you employed by government, by a private company, a nonprofit organization, or were you self-employed?” Those who respond that they were self-employed are then asked if their business is incorporated or not. In the estimation sample, I include individuals between the ages of 21 and 64 and exclude unpaid family members, those unable to work, and retirees.

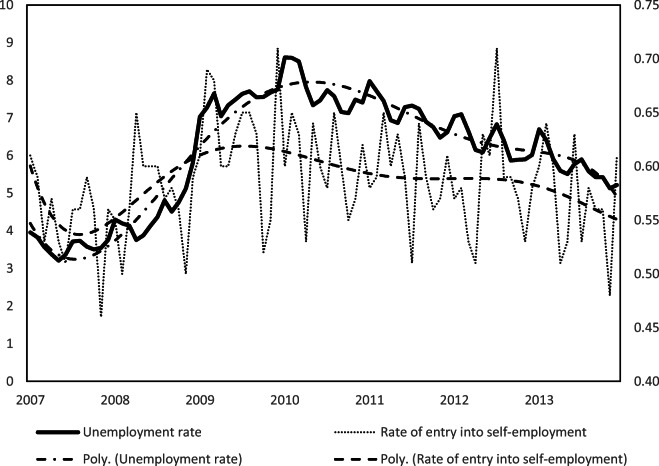

For the decomposition analysis, I split the sample into three periods: before, during, and after the peak of the GR. The peak of the GR is defined as September 2008, when Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, until one year later, August 2009. Figure 1 shows that this was the period of the sharp increase in unemployment in the USA. For comparison, I define the periods before and after the GR with a length of one year each as well. In the main analysis, the period before the GR is April 2007 to March 2008. This is as close as possible to the GR period, but before the increase in unemployment starts. Because the recovery after the GR was slow, I define May 2013 to April 2014 as the period after the GR. In Section 5.3, I assess the sensitivity of the results with respect to the definition of these periods and find that the main results are robust.

Fig. 1.

Unemployment and entry into self-employment. Note: Seasonally adjusted unemployment rate (left scale) and entry rate into self-employment (right scale) in the United States in %, along with sixth degree polynomial fits. Source: Own illustration based on the Current Population Survey 2007-2013

The entry rate before, during, and after the Great Recession

Table 1 shows the mean characteristics of the individuals in the samples before, during, and after the GR, as defined in the previous section for the main analysis.4 Before the GR, 3.7% of the individuals were unemployed. During the GR, the unemployment rate jumped up to 6.6%, before it slowly decreased to 5.5% after the GR in 2013/14. The term “unemployed” means that somebody is looking for paid work. In contrast, “non-participation” means that an individual is not in the labor force. The non-participation rate did not change from before to during the GR and increased somewhat afterwards.

Table 1.

Means of variables before, during, and after the Great Recession

| Variable | Before | During | After |

|---|---|---|---|

| Great Recession | Great Recession | Great Recession | |

| Entry into self-employment | 0.0054 | 0.0061 | 0.0057 |

| Entry into unincorp. self-empl. | 0.0043 | 0.0048 | 0.0044 |

| Entry into incorp. self-empl. | 0.0011 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 |

| Unemployed | 0.0370 | 0.0663 | 0.0545 |

| Non-participation | 0.1220 | 0.1220 | 0.1308 |

| Male | 0.4703 | 0.4723 | 0.4757 |

| Less then high school | 0.0924 | 0.0897 | 0.0800 |

| High school degree | 0.2926 | 0.2913 | 0.2720 |

| Some college | 0.2983 | 0.2985 | 0.3010 |

| College degree | 0.3166 | 0.3205 | 0.3470 |

| Age | 40.8 | 41.0 | 41.2 |

| White | 0.8270 | 0.8258 | 0.8116 |

| African American | 0.0957 | 0.0953 | 0.1004 |

| Other nonwhite | 0.0773 | 0.0789 | 0.0880 |

| Married | 0.6089 | 0.6045 | 0.5769 |

| Number of children | 0.9707 | 0.9660 | 0.9530 |

| Metropolitan area | 0.8003 | 0.8009 | 0.8148 |

| West | 0.2515 | 0.2486 | 0.2543 |

| Northeast | 0.2027 | 0.2052 | 0.1950 |

| Midwest | 0.2378 | 0.2405 | 0.2352 |

| South | 0.3080 | 0.3057 | 0.3155 |

| Observations | 538,469 | 541,517 | 518,355 |

The period before the Great Recession is 04/2007–03/2008, during the GR 09/2008–08/2009, and after the GR 05/2013–04/2014

Source: Own calculations based on the Current Population Survey

The share of individuals who entered into self-employment between two subsequent months before the GR was 0.54%. During the GR, the monthly entry rate increased to 0.61%, then it decreased to 0.57% again. The monthly entry rate into unincorporated self-employment exhibits a similar pattern, going up from 0.43% before to 0.48% during and then down again to 0.44% after the GR. In contrast, the entry rate into incorporated self-employment increased slightly over the entire period.

Figure 1 shows the month-to-month entry rate into self-employment in addition to the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018). Due to the low numbers of entries into self-employment, the monthly averages are noisy, which is my primary motivation for pooling the monthly data over a year in the regressions. The figure also depicts polynomial fits of the sixth degree for the unemployment rate and the monthly entry rate. The two rates clearly move together, although the smoothed entry rate into self-employment does not swing as much as the smoothed unemployment rate.

The aim of the following econometric analysis is to measure how much of the increase in the entry rate into self-employment during the GR is explained by the higher unemployment rate during this period, how much can be explained by other observable factors that also changed during the GR, and how much remains unexplained. I further distinguish between self-employment with unincorporated and incorporated businesses.

Empirical results

Probability model of entry into self-employment

I first report the results of the logit estimations of the probability of entry into self-employment before proceeding with the decomposition. Table 2 shows the average marginal effects of the variables on the month-to-month probability of becoming self-employed (in percentage points) for three separate logit estimations before, during, and after the GR.

Table 2.

Probability of entry into self-employment: marginal effects from logit estimations

| Before Great Recession | Great Recession | After Great Recession | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployed | 1.18∗∗∗ | 1.21∗∗∗ | 1.10∗∗∗ |

| (0.0361) | (0.0343) | (0.0349) | |

| Non-participating | 1.10∗∗∗ | 1.18∗∗∗ | 0.985∗∗∗ |

| (0.0326) | (0.0348) | (0.0322) | |

| Male | 0.404∗∗∗ | 0.391∗∗∗ | 0.311∗∗∗ |

| (0.0240) | (0.0249) | (0.0236) | |

| High school | 0.0270 | − 0.103∗∗∗ | − 0.0737∗∗ |

| (0.0346) | (0.0352) | (0.0369) | |

| Some college | 0.00841 | − 0.0859∗∗ | − 0.0507 |

| (0.0355) | (0.0357) | (0.0368) | |

| College degree | 0.130∗∗∗ | 0.0271 | 0.0395 |

| (0.0351) | (0.0356) | (0.0367) | |

| Black | − 0.102∗∗∗ | − 0.202∗∗∗ | − 0.178∗∗∗ |

| (0.0380) | (0.0416) | (0.0395) | |

| Other nonwhite | − 0.158∗∗∗ | − 0.139∗∗∗ | − 0.0902∗∗ |

| (0.0394) | (0.0416) | (0.0374) | |

| Married | 0.0219 | 0.0462∗ | − 0.00936 |

| (0.0243) | (0.0254) | (0.0248) | |

| No. of children | 0.00500 | − 0.00962 | 0.00852 |

| (0.00953) | (0.00995) | (0.00990) | |

| Metropolitan | − 0.0952∗∗∗ | − 0.0695∗∗∗ | − 0.0642∗∗ |

| (0.0243) | (0.0262) | (0.0268) | |

| Age and age sq. | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Average prob. in % | 0.541 | 0.612 | 0.568 |

| Observations | 538,469 | 541,517 | 518,355 |

Logit estimations of the monthly probability of entry into self-employment before, during, and after the Great Recession. The period before the GR is 04/2007–03/2008, during the GR 09/2008–08/2009, and after the GR 05/2013–04/2014. Average marginal effects in percentage points. Robust standard errors in parentheses. ∗, ∗∗, ∗∗∗Significant at the 10%/5%/1% levels

Source: Own calculations based on the Current Population Survey

In the context of this paper, the most important result from this table is that individual current unemployment status has a strong positive effect on the probability of becoming self-employed in the next month, and that this effect does not change much over the business cycle. Before, during, and after the GR, an unemployed person’s probability of becoming self-employed was about 1.1–1.2 percentage points higher than for other persons, keeping the education level and the other controls constant. The effect is statistically significant at the 1%-level and economically very strong, as the probability of becoming self-employed increases by about 200% for the unemployed relative to the average monthly entry probabilities indicated at the bottom of the table. The effect of individual unemployment on entry into self-employment is stronger than that of any other variable. These results support the “unemployment-push” hypothesis. Non-participation also has a positive effect on the probability of entry into self-employment that is almost as strong as the effect of unemployment, suggesting that some individuals currently not participating in the labor market are similarly pushed into self-employment.

Next, I estimate the monthly probabilities of becoming self-employed with an unincorporated or an incorporated business separately (based on the same sample of those who are not currently self-employed). The results appear in Table 3. Although unemployment status has a positive and significant effect on becoming self-employed with either type of business in all periods, the effect size is about five to six times larger for entry into unincorporated self-employment than for entry into incorporated self-employment. This confirms that running an unincorporated business is often an indicator of necessity entrepreneurship. In contrast, incorporated self-employment is related to opportunity entrepreneurship, i.e., individuals typically leave their paid employment in order to become self-employed directly. Another insight from this table is that the estimated effects of unemployment status on the probabilities of becoming self-employed with either type of business do not change much over the business cycle, similar to what we saw for entry into self-employment in general. For non-participation, we find a similar pattern as for unemployment. The positive and significant effect on entry into unincorporated self-employment is about four to five times larger than the effect on incorporated self-employment.

Table 3.

Probability of entry into (un)incorporated self-employment: marginal effects from logit estimations

| Unincorporated self-employment | Incorporated self-employment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before GR | GR | After GR | Before GR | GR | After GR | |

| Unemployed | 1.000∗∗∗ | 1.040∗∗∗ | 0.920∗∗∗ | 0.163∗∗∗ | 0.169∗∗∗ | 0.171∗∗∗ |

| (0.0323) | (0.0314) | (0.0311) | (0.0186) | (0.0160) | (0.0175) | |

| Non-participating | 0.893∗∗∗ | 0.988∗∗∗ | 0.784∗∗∗ | 0.207∗∗∗ | 0.202∗∗∗ | 0.207∗∗∗ |

| (0.0296) | (0.0319) | (0.0288) | (0.0145) | (0.0152) | (0.0151) | |

| Male | 0.300∗∗∗ | 0.289∗∗∗ | 0.190∗∗∗ | 0.102∗∗∗ | 0.0992∗∗∗ | 0.121∗∗∗ |

| (0.0212) | (0.0223) | (0.0205) | (0.0114) | (0.0114) | (0.0122) | |

| High school | − 0.0238 | − 0.139∗∗∗ | − 0.0836∗∗∗ | 0.107∗∗∗ | 0.105∗∗∗ | 0.0299 |

| (0.0289) | (0.0295) | (0.0308) | (0.0262) | (0.0266) | (0.0229) | |

| Some college | − 0.0674∗∗ | − 0.147∗∗∗ | − 0.0821∗∗∗ | 0.134∗∗∗ | 0.131∗∗∗ | 0.0536∗∗ |

| (0.0301) | (0.0303) | (0.0310) | (0.0262) | (0.0266) | (0.0224) | |

| College degree | 0.00160 | − 0.0946∗∗∗ | − 0.0582∗ | 0.178∗∗∗ | 0.181∗∗∗ | 0.110∗∗∗ |

| (0.0300) | (0.0308) | (0.0315) | (0.0264) | (0.0265) | (0.0221) | |

| Black | − 0.0916∗∗∗ | − 0.170∗∗∗ | − 0.153∗∗∗ | − 0.00981 | − 0.0312 | − 0.0252 |

| (0.0340) | (0.0369) | (0.0349) | (0.0171) | (0.0193) | (0.0187) | |

| Other nonwhite | − 0.146∗∗∗ | − 0.111∗∗∗ | − 0.0891∗∗∗ | − 0.0142 | − 0.0287 | − 0.00262 |

| (0.0357) | (0.0368) | (0.0334) | (0.0171) | (0.0194) | (0.0171) | |

| Married | − 0.00697 | 0.00266 | − 0.0487∗∗ | 0.0310∗∗∗ | 0.0469∗∗∗ | 0.0428∗∗∗ |

| (0.0215) | (0.0225) | (0.0218) | (0.0119) | (0.0126) | (0.0125) | |

| No. of children | − 0.000298 | − 0.00807 | 0.00226 | 0.00446 | − 0.00264 | 0.00453 |

| (0.00863) | (0.00891) | (0.00871) | (0.00415) | (0.00448) | (0.00479) | |

| Metropolitan | − 0.117∗∗∗ | − 0.0827∗∗∗ | − 0.0945∗∗∗ | 0.0314∗∗ | 0.0168 | 0.0396∗∗∗ |

| (0.0211) | (0.0230) | (0.0229) | (0.0131) | (0.0131) | (0.0151) | |

| Age and age sq. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional dum. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Average prob. in % | 0.430 | 0.485 | 0.439 | 0.112 | 0.127 | 0.129 |

| Observations | 538,469 | 541,517 | 518,355 | 538,469 | 541,517 | 518,355 |

Logit estimations of the monthly probability of entry into unincorporated and incorporated self-employment before, during, and after the Great Recession. The period before the GR is 04/2007–03/2008, during the GR 09/2008–08/2009, and after the GR 05/2013–04/2014. Average marginal effects in percentage points. Robust standard errors in parentheses. ∗, ∗∗, ∗∗∗Significant at the 10%/5%/1% levels

Source: Own calculations based on the Current Population Survey

Do key socio-economic and regional conditions moderate the effect of unemployment on entry into self-employment? To investigate potential effect heterogeneity, I interact the unemployment dummy with three dummy variables indicating an individual’s highest educational attainment (high school, some college, and college degree) and with a dummy variable indicating whether an individual lives in a metropolitan area. I estimate linear probability models here as motivated in Section 3. Table 4 provides the results. The coefficient of the unemployment dummy captures the effect of unemployment status for individuals with formal education below a high school degree (the omitted base category).5 For this group with low education, the positive and significant effect of unemployment on the monthly probability of entry into self-employment is larger (plus 2.3 to 2.7% points) than for the total sample as estimated above.

Table 4.

Probability of entry into self-employment: linear probability model with interaction terms

| Total self-employment | Unincorporated self-employment | Incorporated self-employment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before GR | GR | After GR | Before GR | GR | After GR | Before GR | GR | After GR | |

| Unemployed | 2.66∗∗∗ | 2.33∗∗∗ | 2.30∗∗∗ | 2.63∗∗∗ | 2.22∗∗∗ | 2.25∗∗∗ | 0.0341 | 0.109 | 0.0496 |

| (0.363) | (0.263) | (0.305) | (0.355) | (0.255) | (0.296) | (0.0792) | (0.0663) | (0.0742) | |

| High school | 0.0774∗∗ | − 0.0464 | − 0.0458 | 0.00163 | − 0.113∗∗∗ | − 0.0804∗ | 0.0758∗∗∗ | 0.0670∗∗∗ | 0.0346∗ |

| (0.0390) | (0.0447) | (0.0469) | (0.0369) | (0.0422) | (0.0429) | (0.0128) | (0.0146) | (0.0193) | |

| Unempl. × high school | − 0.528 | − 0.802∗∗∗ | − 0.578∗∗ | − 0.535∗ | − 0.883∗∗∗ | − 0.544∗∗ | 0.00621 | 0.0813 | − 0.0336 |

| (0.324) | (0.244) | (0.283) | (0.317) | (0.237) | (0.275) | (0.0698) | (0.0552) | (0.0700) | |

| Some college | 0.0650∗ | − 0.0551 | − 0.0300 | − 0.0331 | − 0.141∗∗∗ | − 0.0752∗ | 0.0980∗∗∗ | 0.0863∗∗∗ | 0.0452∗∗ |

| (0.0387) | (0.0441) | (0.0464) | (0.0363) | (0.0416) | (0.0424) | (0.0132) | (0.0150) | (0.0189) | |

| Unempl. × some college | − 0.492 | − 0.364 | − 0.420 | − 0.591∗ | − 0.535∗∗ | − 0.584∗∗ | 0.0996 | 0.172∗∗ | 0.164∗ |

| (0.339) | (0.258) | (0.290) | (0.328) | (0.250) | (0.278) | (0.0878) | (0.0669) | (0.0860) | |

| College degree | 0.164∗∗∗ | 0.0252 | 0.0265 | 0.0175 | − 0.113∗∗∗ | − 0.0767∗ | 0.146∗∗∗ | 0.138∗∗∗ | 0.103∗∗∗ |

| (0.0396) | (0.0448) | (0.0466) | (0.0368) | (0.0418) | (0.0421) | (0.0149) | (0.0163) | (0.0200) | |

| Unempl. × college degree | 0.110 | 0.148 | 0.346 | − 0.193 | − 0.154 | 0.0245 | 0.303∗∗ | 0.302∗∗∗ | 0.322∗∗∗ |

| (0.392) | (0.294) | (0.330) | (0.370) | (0.279) | (0.310) | (0.133) | (0.0953) | (0.115) | |

| Metropolitan | − 0.0888∗∗∗ | − 0.0687∗∗∗ | − 0.0467∗ | − 0.113∗∗∗ | − 0.0878∗∗∗ | − 0.0787∗∗∗ | 0.0240∗∗ | 0.0191∗ | 0.0320∗∗∗ |

| (0.0248) | (0.0260) | (0.0264) | (0.0226) | (0.0234) | (0.0237) | (0.0102) | (0.0113) | (0.0117) | |

| Unempl. × metropolitan | − 0.200 | − 0.0115 | − 0.256 | − 0.307 | 0.0275 | − 0.325 | 0.108 | − 0.0390 | 0.0697 |

| (0.280) | (0.201) | (0.235) | (0.272) | (0.188) | (0.226) | (0.0701) | (0.0722) | (0.0688) | |

| Non-participating | 1.46∗∗∗ | 1.48∗∗∗ | 1.23∗∗∗ | 1.20∗∗∗ | 1.25∗∗∗ | 0.991∗∗∗ | 0.265∗∗∗ | 0.234∗∗∗ | 0.241∗∗∗ |

| (0.0532) | (0.0540) | (0.0496) | (0.0480) | (0.0493) | (0.0444) | (0.0233) | (0.0226) | (0.0225) | |

| Other controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 538,469 | 541,517 | 518,355 | 538,469 | 541,517 | 518,355 | 538,469 | 541,517 | 518,355 |

OLS estimations of a linear probability model of the monthly probability of entry into total, unincorporated and incorporated entrepreneurship before, during, and after the Great Recession. These specifications include interaction terms of the unemployment dummy with the education dummies and the metropolitan dummy. The other control variables are the same as those shown in Table 2. The coefficients and standard errors are multiplied by 100 to indicate effects in percentage points. Robust standard errors in parentheses. ∗, ∗∗, ∗∗∗Significant at the 10%/5%/1% levels

Source: Own calculations based on the Current Population Survey

The effect of unemployment is smaller, but still positive for individuals with a high school degree. For example, during the GR, individual unemployment increased the probability of entry into self-employment by 2.33 − 0.802 = 1.5% points. The effect is not significantly different for individuals with higher educational attainments. The pattern for total self-employment is driven by entry into unincorporated self-employment, where the effect heterogeneity of unemployment is more pronounced: The positive effect of unemployment on entry into this type of self-employment is significantly smaller for individuals with high school or some college education than for individuals with less than high school. Thus, the push effect of unemployment on entry into unincorporated self-employment is strongest for the group with the lowest and highest levels of formal education.

The picture looks very different for entry into incorporated self-employment. Here, the effect of unemployment on entry is insignificant for individuals with less than high school or high school education, but positive for individuals with some college and even larger for those with a college degree. Thus, the option of becoming self-employed with an incorporated business seems to be a viable route out of unemployment only for individuals with a high level of formal education. This is consistent with Levine and Rubinstein (2017), who report that self-employed individuals with an incorporated business tend to have higher education levels than those with an unincorporated business.

I do not detect significant differences in the effects of unemployment status on entry into self-employment between individuals living in metropolitan and rural areas. For the following decomposition analysis, I use the baseline logit estimations reported above without the interaction terms to focus on the average effects.

Decomposition results

In this section I discuss the results from this paper’s core analysis, the decomposition of the estimated logit models of the probability of entry into self-employment. The aim is to determine how much of the difference between the entry rates during the GR versus before or after the GR can be explained by changes in the independent variables, particularly individual unemployment, and how much remains unexplained. Table 5 presents the results. The first two columns represent decompositions of the entry rate into self-employment in general, including both unincorporated and incorporated self-employment. The first column compares the monthly entry rate during the GR (0.612%) to the lower monthly entry rate before the GR (0.541%), and the second column compares it with the lower monthly entry rate after the GR (0.568%). In both cases, the difference between the mean entry rates is significant at the 1%-level. Changes in the distributions of the independent variables (as reflected in Table 1) explain most of the difference between the entry rates during and before the GR (see row “explained” in Table 5), and the unexplained part is not significantly different from zero. This means that changes in the coefficients and the constant over time, as reflected in Table 2, do not significantly contribute to the increase in the entry rate into self-employment between these periods. When comparing the entry rate during the GR with that after the GR, the explained part of the difference drops to about 30% and the remainder is unexplained.

Table 5.

Nonlinear decomposition of entry rate into self-employment

| Total self-employment | Unincorp. self-employment | Incorp. self-employment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR versus before | GR vs. after | GR vs. before | GR vs. after | GR vs. before | GR vs. after | |

| Overall difference in entrepreneurial entry rates (in percentage points) | ||||||

| Great Rec. | 0.612∗∗∗ | 0.612∗∗∗ | 0.485∗∗∗ | 0.485∗∗∗ | 0.127∗∗∗ | 0.127∗∗∗ |

| (0.0106) | (0.0106) | (0.00941) | (0.00941) | (0.00485) | (0.00485) | |

| Comp. period | 0.541∗∗∗ | 0.568∗∗∗ | 0.430∗∗∗ | 0.439∗∗∗ | 0.112∗∗∗ | 0.129∗∗∗ |

| (0.00997) | (0.0104) | (0.00888) | (0.00916) | (0.00455) | (0.00499) | |

| Difference | 0.0708∗∗∗ | 0.0442∗∗∗ | 0.0552∗∗∗ | 0.0461∗∗∗ | 0.0156∗∗ | − 0.00184 |

| (0.0145) | (0.0148) | (0.0129) | (0.0131) | (0.00665) | (0.00696) | |

| Explained | 0.0678∗∗∗ | 0.0124∗∗∗ | 0.0599∗∗∗ | 0.0139∗∗∗ | 0.00754∗∗∗ | − 0.00137∗∗ |

| (0.00232) | (0.00167) | (0.00213) | (0.00149) | (0.000801) | (0.000590) | |

| Unexplained | 0.00300 | 0.0318∗∗ | − 0.00469 | 0.0322∗∗ | 0.00808 | − 0.000469 |

| (0.0139) | (0.0147) | (0.0123) | (0.0130) | (0.00649) | (0.00701) | |

| Difference explained by individual characteristics | ||||||

| Unemployed | 0.0647∗∗∗ | 0.0427∗∗∗ | 0.0580∗∗∗ | 0.0290∗∗∗ | 0.00644∗∗∗ | 0.00154∗∗∗ |

| (0.00227) | (0.00922) | (0.00212) | (0.00351) | (0.000723) | (0.000245) | |

| Non-particip. | − 0.000137 | − 0.0299∗∗∗ | − 0.000119 | − 0.0197∗∗∗ | − 0.0000177 | − 0.00140∗∗∗ |

| (0.00133) | (0.00790) | (0.00116) | (0.00331) | (0.000172) | (0.000317) | |

| Male | 0.00151∗∗ | − 0.00368∗∗ | 0.00118∗∗ | − 0.00202∗∗∗ | 0.000274∗∗ | − 0.000286∗∗∗ |

| (0.000707) | (0.00147) | (0.000554) | (0.000676) | (0.000131) | (0.000105) | |

| Education | 0.000637∗∗∗ | − 0.00753∗∗∗ | − 0.000188 | 0.000439 | 0.000770∗∗∗ | − 0.00213∗∗∗ |

| (0.000241) | (0.00278) | (0.000186) | (0.00113) | (0.000147) | (0.000460) | |

| Race | − 0.000335 | 0.00625∗∗∗ | − 0.000303 | 0.00435∗∗∗ | − 0.0000353 | 0.000216∗∗ |

| (0.000221) | (0.00157) | (0.000202) | (0.000821) | (0.0000350) | (0.000109) | |

| Married | − 0.000275∗ | 0.00164 | 0.0000230 | − 0.00156 | − 0.000229∗∗∗ | 0.000955∗∗∗ |

| (0.000156) | (0.00143) | (0.000134) | (0.00117) | (0.0000726) | (0.000246) | |

| No. children | 0.0000188 | − 0.0000189 | 0.0000370 | − 0.0000913 | − 0.00000583 | 0.00000963 |

| (0.0000607) | (0.000284) | (0.0000597) | (0.000202) | (0.0000193) | (0.0000334) | |

| Metropolitan | − 0.0000833 | 0.00291∗∗∗ | − 0.000107 | 0.00309∗∗∗ | 0.0000172 | − 0.000294∗∗ |

| (0.000120) | (0.000997) | (0.000152) | (0.000666) | (0.0000253) | (0.000123) | |

| Age | 0.00277∗∗∗ | 0.00514∗∗∗ | 0.00216∗∗∗ | 0.00322∗∗∗ | 0.000508∗∗∗ | 0.000375∗∗ |

| (0.000723) | (0.00179) | (0.000589) | (0.00117) | (0.000170) | (0.000182) | |

| Region | − 0.000987∗∗∗ | − 0.00509∗∗∗ | − 0.000771∗∗∗ | − 0.00290∗∗∗ | − 0.000181∗∗∗ | − 0.000358∗∗∗ |

| (0.000278) | (0.00160) | (0.000241) | (0.000791) | (0.0000657) | (0.000120) | |

| N | 1,079,986 | 1,059,872 | 1,079,986 | 1,059,872 | 1,079,986 | 1,059,872 |

| N: GR | 541,517 | 541,517 | 541,517 | 541,517 | 541,517 | 541,517 |

| N: Comp. per. | 538,469 | 518,355 | 538,469 | 518,355 | 538,469 | 518,355 |

Nonlinear Oaxaca decomposition of the monthly entry rate into self-employment based on logit estimations. The columns show separate decompositions of the difference in the entry rate during the Great Recession and a comparison period before or after the Great Recession. Separate decompositions for entry into all, unincorporated and incorporated self-employment are shown. The lower panel shows the difference between the entry rates in the two periods explained by each of the variables. The period before the GR is 04/2007–03/2008, during the GR 09/2008–08/2009, and after the GR 05/2013–04/2014. All figures are in percentage points. Robust standard errors in parentheses. ∗, ∗∗, ∗∗∗Significant at the 10%/5%/1% levels

Source: Own calculations based on the Current Population Survey 2007–2014

The lower panel of the table reveals which independent variables contribute how much to the change in the entry rate. Groups of variables are considered in the cases of the education and race dummies and the linear and squared age terms. The results are very clear. The change in the distribution of the dummy variable indicating current unemployment status is responsible for almost the entire change in the entry rate, both when comparing the GR period with the periods before and after.6 Combined with the observation that the unemployment rate was higher in the GR than before and after, the findings document that the increase in the entry rate into self-employment during the GR is mostly explained by the increase in unemployment. More precisely, the change in the unemployment rate explains 91% of the raw increase in the entry rate into self-employment from before to the peak of the GR and 97% of the decrease thereafter.

In contrast to unemployment, non-participation does not contribute to explaining the change in the entry rate into self-employment. To the contrary, the contribution of non-participation to the explained part of the change in the entry rate from during to after the GR is significantly negative. This decreases the overall explained portion of the difference in the entry rates and is responsible for the significant unexplained part in this comparison. In other words, given the increase in the non-participation rate observed after the GR (Table 1), one would have expected the entry rate into self-employment to increase rather than decrease. Only the decreasing unemployment rate contributes to explaining the actual decrease in the entry rate. The contributions of the other variables to the changes in the entry rate are close to zero.

The remaining columns of Table 5 show decompositions of the entry rates into unincorporated and incorporated self-employment. The results for unincorporated self-employment are similar to those for total self-employment: Most of the increase in the entry rate from before to during the GR can be explained by changes in the variables and a smaller part of the decrease thereafter. In both comparisons, the unemployment dummy is again the only variable with a substantial positive contribution to the explained part. Non-participation again contributes no or even a negative portion to the explained part of the change in the entry rate.

In contrast to unincorporated self-employment, the increase in the entry rate into incorporated self-employment from before the GR to the peak of it is small, and after the GR, the entry rate increases further slightly, although this further increase is not significantly different from zero. About half of the increase during the GR can be explained by the individual characteristics, again mostly by the unemployment status. Thus, unemployment plays a much smaller role for entry into incorporated self-employment than for entry into unincorporated self-employment, where this variable alone almost explains the full difference of the increase from before to the peak of the GR. In summary, the decomposition results document that the increase in the total entry rate into self-employment during the GR is mostly due to necessity entrepreneurship out of the larger pool of unemployed individuals during the GR in the form of unincorporated self-employment.

Robustness

The main estimations presented so far are based on the weighting method for the decomposition of nonlinear models proposed by Yun (2004), as described in Section 3. Alternatively, Fairlie (2005) suggests a matching method with repeated sample drawings for binary models. Table B.2 in Online Appendix B presents the results from using this method. The qualitative results are the same as those from the baseline estimations in Table 5. First, individual unemployment is the only variable contributing to explaining the change in the entry rate into self-employment over time in a statistically and economically significant way. Second, the role unemployment plays is larger for entry into unincorporated than for entry into incorporated self-employment. Quantitatively, the estimated overall sizes of the explained and unexplained parts are very similar to the baseline estimations in all columns. The positive contribution of individual unemployment is larger in all columns, which is offset by a stronger negative contribution of non- participation. The other control variables again explain much less of the change in the entry rate over time.

Next, I assess the sensitivity of the results (again using the weighting method as in the baseline estimations) with respect to the definition of the periods before and after the GR used for comparison with the period during the GR (09/2008, when Lehman Brothers collapsed, to 08/2009). In the main analysis above, I defined 04/2007–03/2008 as the period before the GR and 05/2013–04/2014 as the period after, as motivated in Section 4.1. Thus, the three periods all have the length of one year.

As the first check, I use two years instead of one year to define the comparison periods and use 04/2006–03/2008 for before and 05/2013–04/2015 for after the GR. The results in Table B.3 are similar to the baseline results in Table 5. A minor difference is that unemployment does not contribute significantly to explaining the change of the entry rate into incorporated self-employment after the GR in this specification, but this is consistent with the conclusion that unemployment plays a much larger role for unincorporated self-employment.

As the second check, I define the GR as the period from 01/2008 to 06/2009, which is the period from a month after the peak until the trough of the business cycle as dated by the National Bureau of Economic Research (2010), and I define the comparison periods as immediately before and after, specifically, 04/2007 to 12/2007 and 07/2009–04/2014.7 The results for the comparisons between the periods before and during the GR shown in Table B.4 are similar to the baseline results in Table 5, in particular concerning the positive contribution of individual unemployment on the changes. Like in the baseline results, individual unemployment explains much less of the change in the entry rate into incorporated self-employment in comparison with what it explains of the change in the entry rate into unincorporated self-employment. Individual non-participation does not contribute significantly to explaining the change in the entry rates when using these comparison periods. When comparing the GR to the period starting immediately after the GR, the difference in the entry rates into the different types of self-employment is almost zero and not statistically significant (see row “difference”). This is due to the slow recovery of the economy after the GR; both the unemployment rate and the entry rate into self-employment changed only gradually. Since there is no gap, it is not insightful to attempt a decomposition. This is the reason why I use a comparison period further away from the GR in the baseline estimations when there is a meaningful difference in the entry rates that can be decomposed.

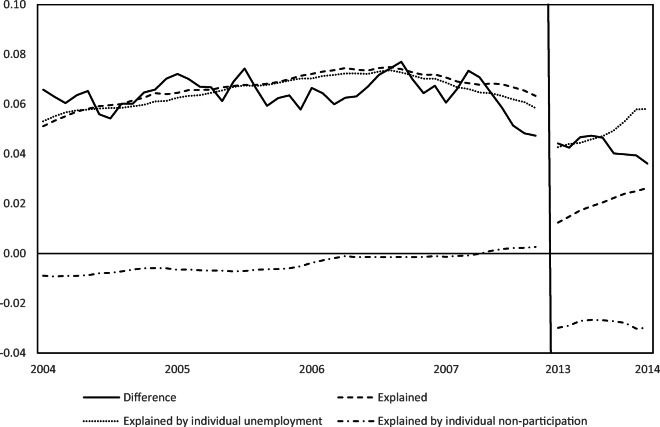

Finally, to assess the sensitivity of the results more systematically and comprehensively, I conduct various decompositions of the entry rate into self-employment like in the baseline estimations, the only difference being that I choose different comparison periods, all of length one year, over the ten years between 2004 and 2014 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Decomposition results with shifting comparison period. Note: The figure shows the results of the decomposition of the change in the entry rate into self-employment (in percentage points) when comparing a shifting time window to the Great Recession period (9/2008-8/2009). The comparison period is always a year wide. For each month in the graph, the results for the comparison period starting in that month are displayed. The solid line shows the difference between the entry rates into self-employment in the Great Recession and the comparison period, the dashed line the explained part of this difference, and the dotted line the part of the difference explained by individual unemployment. For example, for 04/2007 and 05/2013, the figure shows the same results as Table 5. No results are shown for 10/2007-04/2013 (solid vertical line) when the comparison period would be close to the recession. Source: Own illustration based on the Current Population Survey 2004-2014

I start with a decomposition analysis using 01/2004–12/2004 as the period before the GR, then increase the start and end months by one month, using 02/2004–01/2005, and so on. Thus, I always shift the comparison time window by one month and always compare this to the GR period as defined in the baseline estimations (9/2008–8/2009). The last comparison -period before the reform is 09/2007–08/2008, ending right before the GR period begins. Defining adjacent periods for before and during the GR can be justified given the sudden onset of the crisis with its sharp increase in unemployment (Fig. 1).

Next, I systematically compare the GR with comparison periods after the GR, starting with 05/2013–04/2014 like in the baseline model and then shifting the comparison period until it covers 01/2014–12/2014. I do not start the comparison immediately after the period defined as the peak of the GR because the recession dragged on for a long time and unemployment decreased slowly, as mentioned above (again, see Fig. 1).

For each decomposition, Fig. 2 shows the raw difference between the monthly entry rates into self-employment in the GR and in the comparison period, the part of this difference explained by the observed individual characteristics, and the parts of this difference explained by the distribution of current individual unemployment and non-participation. It becomes clear that the main results are robust to the choice of the comparison periods: With any time window chosen for comparison, almost the entire difference in the entry rate into self-employment is explained by the change in unemployment. When comparing the entry rate in the GR with time windows after the GR, individual unemployment still explains the entire change in the entry rate, but the overall explained part is smaller due to a negative contribution of non-participation to the explained part.

In summary, unemployment status very robustly explains almost the entire change in the entry rate into self-employment moving into and out of the GR. However, after the GR, there is also a substantial part of the decrease in the entry rate that remains unexplained. Therefore, an important avenue for further research is to investigate which other factors became relevant after the GR that might account for this unexplained part of the decrease in the entry rate.8

Discussion and conclusion

Entry rates into self-employment move with the unemployment rate over the business cycle. In this paper I use individual-level panel data from the matched monthly US Current Population Survey to decompose the change in the self-employment entry rate into explained and unexplained components. The results indicate that the higher entry rate into self-employment during the 2008/09 Great Recession is almost entirely explained by the higher unemployment rate during this period, together with a stable higher propensity of unemployed persons to become self-employed in comparison to other individuals. Moreover, the higher entry rate into self-employment during the recession is mostly driven by entry into unincorporated self-employment out of unemployment, showing that unincorporated self-employment is strongly related to necessity entrepreneurship (Fairlie and Fossen 2019). In contrast, entry into incorporated self-employment, which is related to opportunity entrepreneurship (Levine and Rubinstein 2017; Herranz et al. 2017), is only weakly linked to the business cycle.

Non-participation in the labor market, like unemployment, increases an individual’s probability of entry into self-employment at all times investigated, but unlike unemployment, non-participation did not increase during the Great Recession. Therefore, the changing entry rate is explained by unemployment, but not by non-participation. I also document that the option of becoming self-employed with an incorporated business is a viable route out of unemployment primarily for individuals with at least some college education. Unemployed individuals with low levels of education are more likely to become self-employed with an unincorporated business, which is associated with less innovation potential.

The results contribute to consolidating seemingly contradictory findings from the extant literature. For example, Fairlie (2013) reports increasing entrepreneurship rates during the Great Recession in the USA, whereas Siemer (2019) documents a fall in employer firms in the same country at the same time, and Brunello and Langella (2016) find decreasing entrepreneurship rates in Italy. The explanation is that Fairlie (2013) uses a broad measure of entrepreneurship including unincorporated businesses, whereas Siemer (2019) only considers employer businesses, and Brunello and Langella (2016) use a narrow definition of entrepreneurship only including self-employed individuals who work as managers, professionals or in other skilled jobs. The narrower definitions in the latter two papers are closer to the specific measure of self-employment with incorporated businesses (see Shane 2014; Levine and Rubinstein2017).

The finding that individual unemployment increases the probability of entry into self-employment is consistent with the “unemployment-push” hypothesis and in line with results from cross-sectional studies. By using individual-level panel data and econometric decomposition techniques, this study extends this research in an important direction by showing that unemployment largely explains the higher entry rate into self-employment during a recession, and by further documenting that this is driven by entry into unincorporated self-employment. Fairlie (2013) also uses panel data, but does not distinguish between unincorporated and incorporated self-employment. Koellinger and Thurik (2012) address heterogeneity among nascent entrepreneurs with respect to necessity and opportunity motives as well as innovativeness in an extension to their study using data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. These papers do not decompose the change in the entry probability into self-employment into explained and unexplained components.

The results of this paper have important implications for economic policy, because they shed light on how to interpret the observed entry rate into self-employment over the business cycle. The finding that unemployed individuals have a high probability of becoming self-employed suggests that self-employment enables workers who become unemployed during a recession to continue to use their human capital, which is likely to alleviate deterioration of human capital and unemployment scarring (Arulampalam et al. 2001). This way, self-employment may facilitate a subsequent economic recovery, and public policy should therefore not impose barriers to this form of business formation. On the other hand, since the additional entry into self-employment during a recession is mostly driven by unemployed individuals and since the additional firms formed are mostly unincorporated, one should expect lower levels of innovativeness and growth ambition of these self-employed individuals on average in comparison to start-ups during boom periods (cf. Ghatak et al. 2007). This result is complementary to that of Sedláček and Sterk (2017), who provide evidence that business cycle conditions at the time of firm formation matter for the performance of firm cohorts. These insights should be taken into account when forecasting the development of new businesses created during recessions and boom periods. In particular, policymakers should not rely on the hope that a higher entry rate into self-employment during a recession will automatically lead to an economic recovery and a new economic boom.

These findings also have important consequences for theory development. As mentioned in the introduction, theoretical models of entrepreneurship and unemployment (Faria et al. 2009; Faria 2015) offer an explanation for economic business cycles: During periods of high unemployment, some of the unemployed choose to become entrepreneurs and bring technological innovations to the market. This leads to growth and the creation of new jobs, which in turn decreases unemployment. When the economy is booming with low unemployment, the number of new entrepreneurs and the rate of technological innovations decreases. This eventually ends the boom and leads to increasing unemployment, and the cycle repeats itself. This empirical paper highlights that theoretical models should take into account the heterogeneity of the self-employed. Unemployment increases entry into self-employment with unincorporated businesses, but there is only a weak relationship between unemployment and entry into self-employment with incorporated businesses. This is relevant because entrepreneurs with incorporated businesses are more likely to be innovative (Levine and Rubinstein 2017), whereas entry into self-employment out of unemployment can be seen as necessity entrepreneurship (Fairlie and Fossen 2019), especially in the form of unincorporated businesses. I also provide evidence that heterogeneity of the unemployed with respect to education is relevant for entry into the different types of self-employment. Thus, future theoretical work should incorporate that the fraction of Schumpeterian entrepreneurs (Schumpeter 1934) who enter the market with innovations among all new entrepreneurs is not constant. This share may be lower among those who are pushed into self-employment due to unemployment in a recession, especially if they have a low education level. These insights may change how models of unemployment and entrepreneurship are able to explain business cycles.

Further empirical research should use data from other recessions and countries to assess the generality of the results found in this study. While the unemployment rate almost completely explains the difference between the entry rates before and during the Great Recession in the USA, a larger part of the decline of the entry rate into self-employment after the Great Recession remains unexplained. An important avenue for further research is to investigate which additional factors related to individuals or the entrepreneurial ecosystem have recently emerged as relevant for entry into self-employment that were irrelevant before. In this context, more research is needed on the roles played by new digital technologies that create novel opportunities in entrepreneurship or by new automation technologies potentially pushing workers out of paid employment (Fossen and Sorgner 2019).

It is also important to investigate in how far the results from this analysis for the USA can be related to developing countries. In particular, further research should analyze the relationships between unemployment, or more generally, a lack of opportunities for paid employment in the formal economy, and different types of self-employment, in particular, informal self-employment, which is widespread in developing countries. These links can be analyzed in relation to short-term business cycles or to longer term economic development. While early theories described informal self-employment in developing countries as an activity of last resort that would shrink when the economy develops and more formal salaried jobs become available (Harris and Todaro 1970), a more nuanced view has since been emerging. Wennekers et al. (2005) argue that necessity entrepreneurship declines as GDP rises from low levels in developing countries, whereas opportunity entrepreneurship increases as GDP rises at high levels in developed countries. Maloney (2004) and Falco and Haywood (2016) suggest that informal self-employment in developing countries may be more accurately interpreted as an analogue to the formal entrepreneurial sector in advanced economies than as a residual of disadvantaged workers. Thus, analyzing longitudinal individual-level data over the business cycle and distinguishing between different types of self-employment as suggested in this paper is a promising avenue to advance the literature not only in the context of developed but also developing countries.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

I thank Todd Sorensen, three anonymous reviewers, and participants at the 2019 Second Annual Workshop on “Entrepreneurship, Economic Development and Public Policy” at the Warsaw School of Economics for their valuable comments.

Footnotes

Caliendo et al. (2014) also make this distinction in an analysis of gender differences in the probability of entry into self-employment using data from Germany.

The two effects are inseparable as well when a region-level unemployment rate is used as an explanatory variable in an analysis otherwise based on individual-level data (e.g., Henley 2004).

In a robustness check described in Section 5.3, I use an alternative decomposition method for binary models suggested by Fairlie (2005).

Table B.1 in Online Appendix B provides additional statistics describing in more detail the distribution of the two non-binary variables used in the analysis.

For individuals living in a metropolitan area, the coefficient of the interaction term with the metropolitan dummy should in principle be added, but it is close to zero and insignificant, as discussed further below.

To see this, compare the row labeled “Unemployed” with the row labeled “Difference”.

I thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this robustness check.

Decker et al. (2016) report that start-up rates rose during the 1990s and declined after 2000 in the high-tech sector. They also observe a generally declining dynamism after 2000.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the IPUMS-CPS database at 10.18128/D030.V5.0.

References

- Arulampalam, W., Gregg, P., & Gregory, M. (2001). Unemployment scarring. Economic Journal, 111(475), 577–584. 10.1111/1468--0297.00663. [Google Scholar]

- Åstebro, T., Chen, J., & Thompson, P. (2011). Stars and misfits: self-employment and labor market frictions. Management Science, 57(11), 1999–2017. 10.1287/mnsc.1110.1400. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B., & Vivarelli, M. (1996). Determinants of new-firm startups in Italy. Empirica, 23(1), 91–105. 10.1007/BF00925009. [Google Scholar]

- Bartz, W., & Winkler, A. (2016). Flexible or fragile? The growth performance of small and young businesses during the global financial crisis – evidence from Germany. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2), 196–215. 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.10.002. [Google Scholar]

- Berglann, H., Moen, E.R., Røed, K., & Skogstrøm, J.F. (2011). Entrepreneurship: origins and returns. Labour Economics, 18(2), 180–193. 10.1016/j.labeco.2010.10.002. [Google Scholar]

- Biehl, A.M., Gurley-Calvez, T., & Hill, B. (2014). Self-employment of older Americans: do recessions matter? Small Business Economics, 42(2), 297–309. 10.1007/s11187--013--9479--7. [Google Scholar]

- Blinder, A. (1973). Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. Journal of Human Resources, 8, 436–55. 10.2307/144855. [Google Scholar]

- Brunello, G., & Langella, M. (2016). Local agglomeration, entrepreneurship and the 2008 recession: evidence from Italian industrial districts. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 58, 104–114. 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2016.03.004. [Google Scholar]

- Brünjes, J., & Diez, J.R. (2013). Recession push and prosperity pull entrepreneurship in a rural developing context. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(3-4), 251–271. 10.1080/08985626.2012.710267. [Google Scholar]

- Caliendo, M., Fossen, F.M., Kritikos, A., & Wetter, M. (2014). The gender gap in entrepreneurship: not just a matter of personality. CESifo Economic Studies, 61(1), 202–238. 10.1093/cesifo/ifu023. [Google Scholar]

- Congregado, E., Golpe, A.A., & Parker, S.C. (2012). The dynamics of entrepreneurship: hysteresis, business cycles and government policy. Empirical Economics, 43(3), 1239–1261. 10.1007/s00181--011--0516--6. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, R.A., Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R.S., & Miranda, J. (2016). Where has all the skewness gone? The decline in high-growth (young) firms in the US. European Economic Review, 86, 4–23. 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.12.013. [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie, R.W. (2005). An extension of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition technique to logit and probit models. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement, 30(4), 305–316. 10.3233/JEM--2005--0259. [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie, R.W. (2013). Entrepreneurship, economic conditions, and the Great Recession. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 22(2), 207–231. 10.1111/jems.12017. [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie, R.W., & Fossen, F.M. (2019). Defining opportunity versus necessity entrepreneurship: two components of business creation. NBER Working Paper 26377, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Falco, P., & Haywood, L. (2016). Entrepreneurship versus joblessness: explaining the rise in self-employment. Journal of Development Economics, 118, 245–265. 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.07.010. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, J.R. (2015). Entrepreneurship and business cycles: technological innovations and unemployment. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(2), 253–265. 10.1007/s11365--014--0327--2. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, J.R., Cuestas, J.C., & Gil-Alana, L.A. (2009). Unemployment and entrepreneurship: a cyclical relation? Economics Letters, 105(3), 318–320. 10.1016/j.econlet.2009.09.004. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, J.R., Cuestas, J.C., & Mourelle, E. (2010). Entrepreneurship and unemployment: a nonlinear bidirectional causality? Economic Modelling, 27(5), 1282–1291. 10.1016/j.econmod.2010.01.022. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, S., King, M., Ruggles, S., & Warren, J.R. (2017). Integrated public use microdata series, current population survey: version 5.0. Dataset, Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota, 10.18128/D030.V5.0.

- Fortin, N., Lemieux, T., & Firpo, S. (2011). Chapter 1 - decomposition methods in economics. Volume 4, Part A of Handbook of Labor Economics, pp.1 – 102. Elsevier, 10.1016/S0169-7218(11)00407-2.

- Fossen, F.M., & Sorgner, A. (2019). Digitalization of work and entry into entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research, forthcoming. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.019.

- Fritsch, M., Kritikos, A., & Pijnenburg, K. (2015). Business cycles, unemployment and entrepreneurial entry – evidence from Germany. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11 (2), 267–286. 10.1007/s11365--014--0326--3. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, M., & Noseleit, F. (2013). Investigating the anatomy of the employment effect of new business formation. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 37(2), 349–377. 10.1093/cje/bes030. [Google Scholar]

- Ghatak, M., Morelli, M., & Sjöström, T. (2007). Entrepreneurial talent, occupational choice, and trickle up policies. Journal of Economic Theory, 137(1), 27–48. 10.1016/j.jet.2006.02.007. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J.R., & Todaro, M.P. (1970). Migration, unemployment and development: a two-sector analysis. American Economic Review, 60(1), 126–142. [Google Scholar]

- Henley, A. (2004). Self-employment status: the role of state dependence and initial circumstances. Small Business Economics, 22(1), 67–82. 10.1023/B:SBEJ.0000011573.84746.04. [Google Scholar]

- Herranz, N., Krasa, S., & Villamil, A.P. (2017). Entrepreneurs, legal institutions and firm dynamics. Economic Theory, 63(1), 263–285. 10.1007/s00199--016--1026--8. [Google Scholar]

- Jann, B. (2008). The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. Stata Journal, 8(4), 453–479. 10.1177/1536867X0800800401. [Google Scholar]

- Koellinger, P.D., & Thurik, A.R. (2012). Entrepreneurship and the business cycle. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(4), 1143–1156. 10.1162/REST--a--00224. [Google Scholar]

- Konon, A., Fritsch, M., & Kritikos, A.S. (2018). Business cycles and start-ups across industries: an empirical analysis of German regions. Journal of Business Venturing, 33(6), 742–761. 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.04.006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y., & Mukoyama, T. (2015). Entry and exit of manufacturing plants over the business cycle. European Economic Review, 77, 20–27. 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.03.011. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R., & Rubinstein, Y. (2017). Smart and illicit: who becomes an entrepreneur and do they earn more? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132 (2), 963–1018. 10.1093/qje/qjw044. [Google Scholar]

- Maloney, W.F. (2004). Informality revisited. World D,evelopment, 32(7), 1159–1178. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.01.008. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Economic Research. (2010). Report of the Business Cycle Dating Committee. https://www.nber.org/cycles/sept2010.html.

- Neumark, D. (1988). Employers’ discriminatory behavior and the estimation of wage discrimination. Journal of Human Resources, 23(3), 279–295. 10.2307/145830. [Google Scholar]

- Oaxaca, R. (1973). Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review, 14, 693–709. 10.2307/2525981. [Google Scholar]

- Oaxaca, R.L., & Ransom, M.R. (1994). On discrimination and the decomposition of wage differentials. Journal of Econometrics, 61(1), 5–21. 10.1016/0304--4076(94)90074--4. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.C. (2018). The economics of entrepreneurship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/9781316756706. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.C., Congregado, E., & Golpe, A.A. (2012). Is entrepreneurship a leading or lagging indicator of the business cycle? Evidence from UK self-employment data. International Small Business Journal, 30(7), 736–753. 10.1177/0266242612437560. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.C., & Robson, M.T. (2004). Explaining international variations in self-employment: evidence from a panel of OECD countries. Southern Economic Journal, 71(2), 287–301. 10.2307/4135292. [Google Scholar]

- Ritsilä, J., & Tervo, H. (2002). Effects of unemployment on new firm formation: micro-level panel data evidence from Finland. Small Business Economics, 19(1), 31–40. 10.1023/A:1015734424259. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. (1934). The theory of economic development, translated by Redvers Opie. Harvard Economic Studies, 46.

- Sedláček, P., & Sterk, V. (2017). The growth potential of startups over the business cycle. American Economic Review, 107(10), 3182–3210. 10.1257/aer.20141280. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S. (2014). Incorporated versus unincorporated self employment. Small Business Trends, https://smallbiztrends.com/2013/11/incorporated-versus-unincorporated-self-employment.html.

- Siemer, M. (2019). Employment effects of financial constraints during the Great Recession. Review of Economics and Statistics, 101(1), 16–29. 10.1162/rest--a--00733. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, D.J. (1991). The birth of new firms–does unemployment matter? A review of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 3(3), 167–178. 10.1007/BF00400022. [Google Scholar]

- Thurik, A.R., Carree, M.A., Van Stel, A., & Audretsch, D.B. (2008). Does self-employment reduce unemployment? Journal of Business Venturing, 23(6), 673–686. 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.007. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). Labor force statistics from the Current Population Survey. https://www.bls.gov/cps/home.htm.