Abstract

Background

Globally, the prevalence of overweight and obesity is escalating, particularly among women and wealthier people. In many developed countries, overweight and obesity are more prevalent in persons with lower socioeconomic status. In contrast, studies in developing countries have reported a higher prevalence rate of overweight and obesity among women with higher educational status. Hence, this study aimed to assess the association between education and the prevalence of overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was done based on the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey (EDHS) data. From the total 15,683 women participants of the 2016 EDHS, 2848 reproductive age group women aged 15–49 years old who had a complete response to all variables of interest were selected and retained for analysis. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 software program. Both descriptive and logistic regression models were used for analysis.

Results

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among the study participants was 11.5 and 3.4% respectively. The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was 14.9%. From the total participants who are overweight and, or obese, majority, 83.3% were urban dwellers and the remaining 16.7% were rural dwellers. Education was positively associated with overweight and obesity among women. Besides, increased age, region, living in urban areas, being in rich quintile, increased frequency of watching television, and frequency of using internet were significantly associated with the odds of being overweight and obese among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia.

Conclusions

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia is increasing compared to previous studies. Education was found to be a risk factor for overweight and obesity among women. Hence, context based interventions on the prevention and control methods of overweight and obesity are required.

Keywords: Education, Ethiopia, Obesity, Overweight, Reproductive age group women

Background

Over nutrition is becoming the major global public health problem. It includes, overweight, obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [1]. Overweight and obesity refers an excessive fat accumulation in body tissues [2]. Obesity is an illness and necessitates immediate reversal to prevent early and untimely death among patients [2, 3].

Globally, the prevalence of overweight and obesity is escalating, particularly among women and wealthier people [4]. Overweight and obesity in women increases the risk of diabetes, hypertension, caesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, and high birth weight baby, infant overweight and obesity [1, 5].

The disease burden related to high BMI has increased starting from 1990. Since 1980, the prevalence of obesity has doubled in more than 70 countries and has continuously increased in most other countries. In 2015 alone, more than 603 million adults were obese worldwide [6].

In 2013, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among women was 37% worldwide which is slightly higher than the men (36%) [7]. According to a study on trends in obesity among adults in the United States, the prevalence of obesity alone in 2013–2014 was 40.4% among women which is significantly higher than the men’s prevalence rate (35%) [8].

Even though largely preventable, overweight and obesity are liked to more deaths than underweight [9]. In 2015, high BMI had caused an estimated 4 million deaths globally, and nearly 40% of these deaths occurred in persons who were not obese but high BMI. More than two thirds of deaths related to high BMI were due to cardiovascular diseases [6, 10].

Latest WHO reports also show that overweight and obesity are becoming the leading causes of death worldwide [1, 9]. Overweight and obesity affects all age groups of people both in developed and developing countries regardless of their socioeconomic status [1, 11].

According to a study on the global trends of overweight and obesity, 26.9% of adults in Africa are overweight and obese. It has also revealed that obesity was twice more common among women than men [12].

Over nutrition costs the world billions of dollars a year in lost opportunities for economic growth and lost investments in human capital associated with increased preventable morbidity and mortality rates in both children and adults [1, 13].

Ethiopia is not different. According to the 2016 EDHS report 22% of reproductive age group women were underweight, an 8% drop from 30% in the 2000 EDHS. However, the proportion of overweight and obesity among women has increased from 3% in 2000 to 8% in 2016 [14].

Overweight and obesity are associated with many factors including excessive consumption of alcohol, cigarette smoking and sedentary life style habits [15, 16]. Overweight and obesity are also linked with lower socioeconomic status [17, 18].

In many developed countries, women with a low level of educational status are two to three times more likely to be overweight and obese than those with a higher level of education [19]. This might be due to the failure of women to recognize the risks and the consequences of being overweight and obese as fatness is considered a symbol of beauty and prosperity in many societies [20, 21].

Therefore, education is the major tool to promote healthy behaviors and solve these problems [22, 23]. However, there are contrasting studies in developing countries which have reported a higher prevalence rate of overweight and obesity among women with higher educational status than their counter parts [24, 25]. Hence, this study aimed to assess the association between educational status and the prevalence of overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and population

This cross-sectional study was done based on the 2016 EDHS data. The survey included a nationally representative sample of women (aged 15–49 years) and men (aged 15–59 years) from the nine regions and two administrative cities of the country [14]. However, the current study involved non-pregnant reproductive age group women only because, unlike men, overweight and obesity in women are more prevalent and are associated with multiple problems including increased risk of diabetes, hypertension, caesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, high birth weight babies, and infant overweight and obesity [1]. Pregnant women were excluded, because, pregnancy nullifies the values of BMI and data about BMI was not collected among pregnant, and those women who have had a birth in the 2 months before the survey in the 2016 EDHS [14].

Sampling technique

In the 2016 EDHS, a two stage stratified sampling technique was employed to select representative samples for the country as whole. The regions in the country were stratified into urban and rural areas. Then, samples of enumeration areas (EAs) were selected in each stratum in two stages. In the first stage, 645 EAs were selected with probability proportional to the EA size. The EA size is the number of residential households in the EA as determined in the 2007 Ethiopian Population and Housing Census. A household listing operation was implemented in the selected EAs, and the resulting lists of households served as the sampling frame for the selection of households in the second stage. In the second stage, a fixed number of 28 households per cluster were selected with an equal probability systematic selection from the newly created household listing. All women aged 15–49 years who were usual members of the selected households or who spent the night before the survey in the selected households were eligible for the female survey [14]. For the purpose of this study, from the total, 15,683 women participants of the 2016 EDHS, a sub-sample of 2848 reproductive age group women aged 15–49 years who had a complete response to all variables of interest were selected and retained for analysis after excluding women who were pregnant.

Data collection

In the 2016 EDHS, a standardized and validated questionnaire were adapted from the DHS Program’s standard Demographic and Health Survey questionnaires in a way to reflect the population and health issues relevant to Ethiopia. The survey data were collected from January 18 to June 27, 2016 by trained field workers [14]. For the purpose of the current study, the women’s data from the 2016 EDHS was utilized.

Variables and operational definitions

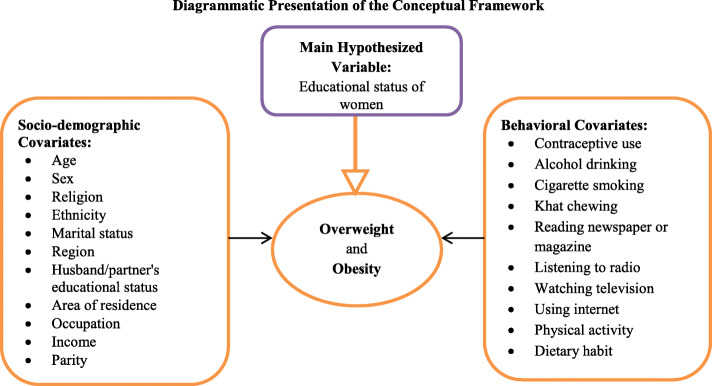

In addition to education, several important covariates like, respondent’s age, and wealth index were analyzed depending on their availability in the 2016 EDHS data (Fig 1). Educational level of participants was categorized as; no education, primary, secondary, and higher education. Additional details of independent variables are available somewhere else [28]. The dependent variables of interest were overweight and obesity among non-pregnant women aged 15–49 years. These outcome variables of interest were categorized as follows based on the WHO Classification of body mass index; overweight if the BMI is 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 and obese if it is≥30 kg/m2 [2]. The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was determined by merging the two outcomes together.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework for the prevalence of overweight and obesity and its associated factors among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia, adapted from different sources by the principal investigator after reviewing different literatures [8, 14, 26, 27]

Statistical analysis

Data analysis started with a summary of the socio-demographic characteristics, and other important factors were included in assessment of overweight and obesity among women using frequency distribution analysis. Weighting was applied during preparation of analytical sample and in all percentage calculations so that to make the results representative for reproductive age group women in Ethiopia. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 software program. Bivariate analysis using Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to assess the frequency distribution of the main outcomes and is presented in relation to different socio-demographic characteristics. Binary logistic regression analysis was carried out to see the association between overweight and obesity and each predictor variable separately to present a crude or unadjusted analysis. Then, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was done to examine the association between educational status of women, other covariates and overweight and, or obesity. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used to declare a statistically significant association between the independent and the outcome variables.

Result

Baseline characteristics of respondents

In this study 2848 participants of the 2016 EDHS were included. More than half, 53.2% of the participants were Orthodox Christianity followers, 23.7% Muslims, 21.9% Protestants, 0.7% Catholics and the remaining 0.5% were traditional and other religion followers. Regarding to educational status of the study participants, 43.2% had no education and the remaining 56.8% had completed up to higher levels of education. Majority, 63% of the participants were rural dwellers. Furthermore, 59.6% of the participants were in the first (rich) wealth index quintile, 15.9% were in the second (middle) quintile and 24.5% were in the third (poor) quintile (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of reproductive age group women in Ethiopia, EDHS 2016, (N = 2848)

| Characteristics | Response | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational status of respondents | No education | 1231 | 43.2 |

| Primary | 990 | 34.8 | |

| Secondary | 365 | 12.8 | |

| Higher | 262 | 9.2 | |

| Respondents age | 15–24 years old | 728 | 25.6 |

| 25-34 years old | 1306 | 45.9 | |

| > = 35 years old | 814 | 28.6 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 1516 | 53.2 |

| Catholic | 21 | 0.7 | |

| Protestant | 623 | 21.9 | |

| Muslim | 674 | 23.7 | |

| Others | 14 | 0.5 | |

| Region of respondents | Tigray | 330 | 11.6 |

| Afar | 70 | 2.5 | |

| Amhara | 532 | 18.7 | |

| Oromia | 363 | 12.7 | |

| Somali | 16 | 0.6 | |

| Benishangul | 207 | 7.3 | |

| SNNPR | 480 | 16.9 | |

| Gambella | 192 | 6.7 | |

| Harari | 146 | 5.1 | |

| Addis Ababa | 354 | 12.4 | |

| Dire Dawa | 158 | 5.5 | |

| Area of residence | Urban | 1054 | 37.0 |

| Rural | 1794 | 63.0 | |

| Employment status | Not employed | 1243 | 43.6 |

| Employed | 1605 | 56.4 | |

| Husband/partners educational status | No education | 899 | 31.6 |

| Primary | 1089 | 38.2 | |

| Secondary | 465 | 16.3 | |

| Higher | 395 | 13.9 | |

| Respondents wealth index | Poor | 698 | 24.5 |

| Medium | 453 | 15.9 | |

| Rich | 1697 | 59.6 |

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women was 11.5 and 3.4% respectively and, the combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was 14.9% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia (N = 2848)

| Variable | Outcome | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overweight | Yes | 327 | 11.5 |

| No | 2521 | 88.5 | |

| Obese | Yes | 98 | 3.4 |

| No | 2750 | 96.6 | |

| Overweight and obese | Yes | 425 | 14.9 |

| No | 2423 | 85.1 |

The prevalence of overweight and obesity was higher, 37, 26.7 and 16.2% respectively among women with a higher, secondary and primary level of education compared to 5.8% among women with no education. Besides, the prevalence of overweight and obesity was 19.8 and 16.2% among women with age group of > = 35 years and 25–34 years respectively compared to 6.6% in women with age group of 15–24 years. Similarly, the prevalence of overweight and obesity was also higher, 23.7% in women with rich wealth quintile compared to 1.4% in women with poor wealth quintile (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cross-tabulation of baseline characteristics, and overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia (N = 2848)

| Respondents baseline Characteristics | Overweight and Obese | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | ||

| Educational status of respondents | |||

| No education | 72(5.8) | 1159(94.2) | < 0.001 |

| Primary | 160(16.2) | 830(83.8) | |

| Secondary | 96(26.7) | 269(73.3) | |

| Higher | 97(37.0) | 165(63.0) | |

| Respondents age | |||

| 15–24 years old | 48(6.6) | 680(93.4) | < 0.001 |

| 25-34 years old | 216(16.5) | 1090(83.5) | |

| > =35 years old | 161(19.8) | 653(80.2) | |

| Religion | |||

| Orthodox | 254(16.8) | 1262(83.2) | < 0.001 |

| Catholic | 2(9.5) | 19(90.5) | |

| Protestant | 55(8.8) | 568(91.2) | |

| Muslim | 113(16.8) | 561(83.2) | |

| Others | 1(7.1) | 13(92.9) | |

| Number of children | |||

| None | 24(10) | 215(90) | < 0.001 |

| 1–3 | 299(18.3) | 1335(81.7) | |

| > =4 | 102(10.5) | 873(89.5) | |

| Type of current contraceptive use | |||

| Traditional | 23(31.5) | 50(68.5) | < 0.001 |

| Modern | 402(14.5) | 2373(85.5) | |

| Duration of current contraceptive use | |||

| < =6 month | 258(15.5) | 1408(84.5) | 0.316 |

| > 6 month | 167(14.1) | 1015(85.9) | |

| Region of respondents | |||

| Tigray | 22(6.7) | 308(93.3) | < 0.001 |

| Afar | 16(22.9) | 54(77.1) | |

| Amhara | 23(4.3) | 509(95.7) | |

| Oromia | 33(9.1) | 330(90.9) | |

| Somali | 5(31.2) | 11(68.8) | |

| Benishangul | 26(12.6) | 181(87.4) | |

| SNNPR | 30(6.2) | 450(93.8) | |

| Gambella | 22(11.5) | 170(88.5) | |

| Harari | 51(34.9) | 95(65.1) | |

| Addis Ababa | 147(41.5) | 207(58.5) | |

| Dire Dawa | 50(31.6) | 108(68.4) | |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 354(33.6) | 700(66.4) | < 0.001 |

| Rural | 71(4.0) | 1723(96.0) | |

| Employment status | 0.223 | ||

| Not employed | 174(14.0) | 1069(86.0) | |

| Employed | 251(15.6%) | 1354(84.4) | |

| Husband/partners educational status | |||

| No education | 57(6.3) | 842(93.7) | < 0.001 |

| Primary | 117(10.7) | 972(89.3) | |

| Secondary | 124(26.7) | 341(73.3) | |

| Higher | 127(32.2) | 268(67.8) | |

| Respondents wealth index | < 0.001 | ||

| Poor | 10(1.4) | 688(98.6) | |

| Medium | 13(2.9) | 440(97.1) | |

| Rich | 402(23.7) | 1295(76.3) | |

| Respondent drinks alcohol | |||

| No | 228(14.3) | 1364(85.7) | 0.311 |

| Yes | 197(15.7) | 1059(84.3) | |

| Respondent smokes cigarette | |||

| No | 423(14.9) | 2408(85.1) | 0.714 |

| Yes | 2(11.8) | 15(88.2) | |

| Respondent chews chat | |||

| No | 347(13.6) | 2199(86.4) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 78(25.8) | 224(74.2) | |

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine | |||

| Not at all | 267(11.3) | 2095(88.7) | < 0.001 |

| Less than once a week | 111(30.9) | 248(69.1) | |

| At least once a week | 47(37.0) | 80(63.0) | |

| Frequency of listening to radio | |||

| Not at all | 185(10.9) | 1514(89.1) | < 0.001 |

| Less than once a week | 95(17.1) | 459(82.9) | |

| At least once a week | 145(24.4) | 450(75.6) | |

| Frequency of watching television | |||

| Not at all | 85(5.1) | 1572(94.9) | < 0.001 |

| Less than once a week | 53(14.0) | 325(86.0) | |

| At least once a week | 287(35.3) | 526(64.7) | |

| Frequency of using internet | |||

| Not at all | 351(13.1) | 2326(86.9) | < 0.001 |

| Less than once a week | 16(42.1) | 22(57.9) | |

| At least once a week | 32(44.4) | 40(55.6) | |

| Almost every day | 26(42.6) | 35(54.7) | |

Regression analysis of associated factors with overweight and obesity

In this study bivariate logistic regression analysis was performed and, variables which have a p-value of less than 0.25 were fitted into the multivariable logistic regression analysis model. In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, educational status was significantly associated the odds of being overweight and obese among women. The odds of being overweight and obese was around 2 times higher among those who had higher (AOR = 2.11, 95% CI, 1.18, 3.76), secondary (AOR = 1.90, 95% CI, 1.16, 3.12) and primary education (AOR = 1.91, 95% CI, 1.30, 2.79) than those who had no education.

Besides, respondent’s age, region, residence, wealth index, frequency of watching television, and frequency of using internet were positively associated with the odds of overweight and obesity among women. The odds of overweight and obesity among respondents aged 25–34 years and > =35 years was more than 3 (AOR = 3.03, 95% CI, 2.06, 4.48) and 6.5 (AOR = 6.51, 95% CI, 4.08, 10.37) times higher respectively than those aged 15–24 years old. The odds of being overweight and obese among respondents living in Oromia, Somali, Benishangul, Harari, Addis Ababa, and Dire Dawa was higher than those who live in Tigray region.

Similarly, the odds of those who live in urban areas was more than 3 folds higher (AOR = 3.11, 95% CI, 2.02, 4.80) than those who live in rural areas. Wealth index was also significantly associated with overweight and obesity. The odds of being overweight and obese among respondents of rich wealth quintile class was around 5 times higher (AOR = 4.82, 95% CI, 2.40, 9.71) than those who are from poor wealth quintile class. Frequency of media use was also significantly associated with overweight and obesity. The odds of being overweight and obese was higher among those watch television at least once a week (AOR = 1.91, 95% CI, 1.26, 2.90) and use internet at least once a week (AOR = 1.89, 95% CI, 1.06, 3.36) compared to those who did not use it at all (Table 4).

Table 4.

Regression analysis of overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women with their educational status and other covariates in Ethiopia, (N = 2848)

| Respondent Characteristics | Overweight and Obese | Bivariate logistic regression | Multivariable logistic regression | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | ||

| Educational status | |||||

| No education | 72(5.8) | 1159(94.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| Primary | 160(16.2) | 830(83.8) | 3.10(2.32,4.16) | 1.91(1.30,2.79) | 0.001 |

| Secondary | 96(26.7) | 269(73.3) | 5.75(4.12,8.02) | 1.90(1.16,3.12) | 0.011 |

| Higher | 97(37.0) | 165(63.0) | 9.46(6.70,13.37) | 2.11(1.18,3.76) | 0.012 |

| Respondents age | |||||

| 15–24 years old | 48(6.6) | 680(93.4) | 1 | 1 | |

| 25-34 years old | 216(16.5) | 1090(83.5) | 2.81(2.02,3.89) | 3.03(2.06,4.48) | < 0.001 |

| > =35 years old | 161(19.8) | 653(80.2) | 3.49(2.49,4.91) | 6.51(4.08,10.37) | < 0.001 |

| Religion | |||||

| Orthodox | 254(16.8) | 1262(83.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| Catholic | 2(9.5) | 19(90.5) | 0.52(0.12,2.26) | 0.46(0.09,2.37) | 0.353 |

| Protestant | 55(8.8) | 568(91.2) | 0.48(0.35,0.66) | 0.72(0.48,1.07) | 0.105 |

| Muslim | 113(16.8) | 561(83.2) | 1.00(0.79,1.28) | 1.01(0.73, 1.39) | 0.977 |

| Others | 1(7.1) | 13(92.9) | 0.38(0.05,2.94) | 0.87(0.10,7.69) | 0.901 |

| Number of children | |||||

| None | 24(10) | 215(90) | 1 | 1 | |

| 1–3 | 299(18.3) | 1335(81.7) | 2.01(1.29,3.12) | 1.46(0.86,2.49) | 0.167 |

| > =4 | 102(10.5) | 873(89.5) | 1.05(0.66,1.67) | 1.496(0.78,2.89) | 0.229 |

| Type of current contraceptive use | |||||

| Traditional | 23(31.5) | 50(68.5) | 2.72(1.64,4.50) | 0.74(0.40,1.36) | 0.335 |

| Modern | 402(14.5) | 2373(85.5) | 1 | 1 | |

| Respondents region | |||||

| Tigray | 22(6.7) | 308(93.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Afar | 16(22.9) | 54(77.1) | 4.15(2.05,8.40) | 2.06(0.90,4.71) | 0.087 |

| Amhara | 23(4.3) | 509(95.7) | 0.63(0.35,1.15) | 0.96(0.49,1.86) | 0.896 |

| Oromia | 33(9.1) | 330(90.9) | 1.40(0.80,2.45) | 2.29(1.21,4.35) | 0.011 |

| Somali | 5(31.2) | 11(68.8) | 6.36(2.03,19.94) | 4.88(1.30,18.31) | 0.019 |

| Benishangul | 26(12.6) | 181(87.4) | 2.01(1.11,3.65) | 4.05(2.04,8.07) | < 0.001 |

| SNNPR | 30(6.2) | 450(93.8) | 0.93(0.53,1.65) | 1.89(0.96,3.74) | 0.067 |

| Gambella | 22(11.5) | 170(88.5) | 1.81(0.98,3.37) | 1.54(0.77,3.09) | 0.227 |

| Harari | 51(34.9) | 95(65.1) | 7.52(4.34,13.03) | 3.10(1.62,5.92) | 0.001 |

| Addis Ababa | 147(41.5) | 207(58.5) | 9.94(6.14,16.09) | 2.54(1.46,4.39) | 0.001 |

| Dire Dawa | 50(31.6) | 108(68.4) | 6.48(3.75,11.20) | 2.28(1.21,4.29) | 0.011 |

| Residence | |||||

| Urban | 354(33.6) | 700(66.4) | 12.27(9.37,16.07) | 3.11(2.02,4.80) | < 0.001 |

| Rural | 71(4.0) | 1723(96.0) | 1 | 1 | |

| Employment status | |||||

| Not employed | 174(14.0) | 1069(86.0) | 0.88(0.71,1.08) | 0.89(0.68,1.15) | 0.361 |

| Employed | 251(15.6%) | 1354(84.4) | 1 | 1 | |

| Husband/partners educational status | |||||

| No education | 57(6.3) | 842(93.7) | 1 | 1 | |

| Primary | 117(10.7) | 972(89.3) | 1.78(1.28,2.47) | 0.83(0.56,1.24) | 0.365 |

| Secondary | 124(26.7) | 341(73.3) | 5.37(3.83,7.53) | 1.00(0.63,1.59) | 0.999 |

| Higher | 127(32.2) | 268(67.8) | 7.00(4.98,9.85) | 1.11(0.67,1.84) | 0.697 |

| Wealth index | |||||

| Poor | 10(1.4) | 688(98.6) | 1 | 1 | |

| Medium | 13(2.9) | 440(97.1) | 2.03(0.88,4.68) | 1.99(0.85,4.63) | 0.111 |

| Rich | 402(23.7) | 1295(76.3) | 21.36(11.33,40.27) | 4.82(2.40,9.71) | < 0.001 |

| Respondent chews Chat | |||||

| No | 423(14.9) | 2408(85.1) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 2(11.8) | 15(88.2) | 2.21(1.67,2.92) | 1.42(0.98,2.07) | 0.063 |

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine | |||||

| Not at all | 267(11.3) | 2095(88.7) | 1 | 1 | |

| Less than once a week | 111(30.9) | 248(69.1) | 3.51(2.72,4.54) | 1.03(0.73,1.46) | 0.853 |

| At least once a week | 47(37.0) | 80(63.0) | 4.61(3.15,6.76) | 1.08(.67,1.75) | 0.760 |

| Frequency of listening to radio | |||||

| Not at all | 185(10.9) | 1514(89.1) | 1 | 1 | |

| Less than once a week | 95(17.1) | 459(82.9) | 1.69(1.30,2.22) | 0.63(0.45,0.89) | 0.008 |

| At least once a week | 145(24.4) | 450(75.6) | 2.64(2.07,3.36) | 0.85(0.61,1.17) | 0.320 |

| Frequency of watching television | |||||

| Not at all | 85(5.1) | 1572(94.9) | 1 | 1 | |

| Less than once a week | 53(14.0) | 325(86.0) | 3.02(2.10,4.34) | 1.32(0.83,2.12) | 0.246 |

| At least once a week | 287(35.3) | 526(64.7) | 10.09(7.77,13.11) | 1.91(1.26,2.90) | 0.002 |

| Frequency of using internet | |||||

| Not at all | 351(13.1) | 2326(86.9) | 1 | 1 | |

| Less than once a week | 16(42.1) | 22(57.9) | 4.82(2.51,9.27) | 1.33(0.62,2.86) | 0.461 |

| At least once a week | 32(44.4) | 40(55.6) | 5.30(3.29,8.55) | 1.89(1.06,3.36) | 0.031 |

| Almost every day | 26(42.6) | 35(54.7) | 4.92(2.93,8.28) | 1.28(0.68,2.43) | 0.449 |

Discussion

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among the study participants was 11.5 and 3.4% respectively. The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was 14.9%. This finding is higher than previous studies conducted in Ethiopia [29, 30]. However, it is lower than a study in Malawi that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among adult women was 16.8 and 6.3%, respectively [26]. This variation in the prevalence rates might be due to the differences in the age group of study participants.

Unlike the current study, the Malawi study was conducted among adults aged from 18 years to 49 years old. The current study was conducted among reproductive age group women aged from 15 to 49 years old which can potentially lower the prevalence of overweight and obesity among women. Because, age of participants was one determinant which was significantly associated with the prevalence of overweight and obesity among the study participants. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among the age group of participants containing adolescents was lower than the other groups in this study. Adolescence is a stage of rapid growth and development and there is an increase in nutrition demand at this time [31]. Thus, the inclusion of adolescents may potentially hider the overall prevalence of overweight and obesity among the study participants in this study.

It is also lower than a study in India which had shown that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women was 22.6 and 10.7% respectively [27]. This variation may emanate from differences in developmental level of the two countries, because, majority of the associated factors with overweight and obesity are the result of demogtaphic and socioeconomic transitions across countries [32]. The high prevalence of overweight and, or obesity in women might be also due to their physiology as they tend to deposit more fat than lean mass [33–35].

Besides, from the total participants who are overweight and obese, majority, 83.3% were urban dwellers and the remaining 16.7% were rural dwellers. This finding is in line with the Malawi and Indian studies that the prevalence of overweight and obesity was higher among women living in urban areas as compared to their counter parts [26, 27]. Consistent finding has been also reported in other low and middle-income countries [36–38]. This could be attributed to the life style of urban dwellers. Unlike rural residents who are usually more actively involved in a less sedentary lifestyle and more laborious activities, the occupation of urban dwellers may result in sedentary type life styles among women [39–41].

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis model, educational status of women was positively associated with the odds of being overweight and obese. The odds of being overweight and obese was around 2 times higher among those who had higher, secondary and primary educational status than those who had no education. This is not expected because people who are educated are expected to get more information on the effect and methods of overweight and obesity from different sources than those who are not educated. Nevertheless, consistent findings have been reported in other low and middle-income countries [24, 25]. The possible explanation could be people with a higher level of educational status usually live in urban areas where the prevalence of overweight and obesity is higher than those who are not educated [42].

Besides, women with higher educational level are more likely to have a higher wealth status one of the significant factor for overweight and obesity than less-educated women [43]. The other reason could be as people with better educational status usually live in urban areas, the nature of their occupation might lead to increased body weight than the rural residents [42, 44]. This can be justified by the results of the current study that from the total participants who are overweight and obese, majority, 83.3% were urban dwellers and only 16.7% were rural dwellers.

In addition, respondent’s age, region, residence, wealth index, frequency of listening to radio, frequency of watching television, and frequency of using internet were significantly associated with overweight and obesity among women. The odds of being overweight and obese among respondents aged 25–34 years old and > =35 years old were more than 3 and 6.5 times higher respectively than those aged 15–24 years old. This is in agreement with studies conducted in both developed and developing countries which have indicated that overweight and obesity in women tend to increase with age [45–47].

It might be also due to family transitions as some studies shown that starting at the age of 30 years women tend to shift various household roles to their children making themselves less active in routine household activities. As women grew old, some tend to express less willingness to reduce their body weight irrespective of their health status [47]. The link between age and body weight might be due to the fact that increasing age is a known risk factor of overweight, obesity and other non-communicable diseases [48]. Furthermore, advancing age is linked with number of parity which is an important risk factor for overweight and obesity [49]. Body weight usually increases during pregnancy which can be continued for a lifetime if weight loss did not occur in the post-partum period [50, 51].

The odds of being overweight and obese among respondents living in Oromia, Somali, Benishangul, Harari, Addis Ababa, and Dire Dawa was higher than those who live in Tigray region. This difference might be due to differences in sociodemographic and socioeconomic status of the people in these regions. For example, unlike Tigray region which contains both urban and rural residents, Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa are urban and people living in urban areas are at increased risk of being overweight and obese as evidenced in this and other previous studies [26, 27, 52, 53].

In this study the odds of being overweight and obese was more than 3 folds higher among women living in urban areas than those who live in rural areas. This finding is in line with the Malawi and Indian studies [26, 27]. This could be due to the fact that urban dwellers are usually from middle and high income groups of people and, households with a high income tend to purchase food in bulk, spending more on both healthy and less healthy foods [47]. The other reason could be due to differences in the life style of urban dwellers. Unlike the rural residents who are usually more actively involved in a less sedentary lifestyle and more laborious activities, the occupation of urban dwellers may result in sedentary type life styles [39].

Similarly, in this study, wealth index was significantly associated with increased odds of overweight and obesity. The odds of being overweight and obese among respondents of rich wealth quintile class was around 5 times higher than those who are from poor wealth quintile class. This finding is consistent with a study in Kenya where the women with more sedentary life style were in the highest income groups [54]. It is also consistent with a study in Bangladesh [43]. This might be also due to their capacity of purchasing more energy-dense foods as witnessed from studies in both developed and developing countries that high-income households purchased foods in bulk and were more likely to over consume these foods [13, 55].

Besides, frequency of media use was also significantly associated with overweight and obesity. The odds of being overweight and obese was a round 2 times higher among those who watch television at least once a week and use internet at least once a week respectively compared to those who did not use it at all. The possible explanation is that people who use media are more likely from medium and rich groups a very significant factor which is associated with overweight and obesity in this and other studies [26, 27]. In addition, education was also associated with the odds of overweight and obesity. The other reason is that people who use media are usually urban dwellers, another highly significant determinant of overweight and obesity [26, 27, 44].

However, in this study smoking, alcohol consumption, chewing chat and contraceptive use were not associated with the odds of being overweight and obese. This finding is inconsistent compared with a study in India which found that use of hormonal contraceptives was one of the significant factors that determine the prevalence of overweight and obesity among women [27]. This is unexpected, because, hormonal contraceptives are a known risk factor for overweight and obesity and requires further studies to affirm the association between contraceptive use and overweight and obesity among women in Ethiopia [56–58].

Strength and limitations of the study

One of the main strength of this study is its large sample size and the random sampling method used to recruit participants in the survey which makes the study participants a true representative of reproductive age group non-pregnant women in Ethiopia. The quality of the data is also assured as the EDHS uses well-trained field personnel’s, a standardized protocol, and validated tools in the data collection process. However, as a limitation, some of the very important determinants of overweight and obesity such as physical activity and dietary habits were not included in this study because, the relevant information’s regarding these variables are not available in the 2016 EDHS dataset. The other important limitation is the information in the survey was self-reported, so some degree of under-reporting of socially unacceptable behaviors and over-reporting of socially desirable behaviors are likely [14].

Conclusion

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women is increasing in Ethiopia particularly among urban dwellers. Education was positively associated with the odds of overweight and obese among women. Besides, increased age, region, residing in urban areas, being rich, increased frequency of watching television, and frequency of using internet were significantly associated with overweight and obesity. This is an indication of how overweight and obesity are major problems for women especially to those living in urban areas regardless of their educational status. This is worrying because overweight and obesity might increase women’s vulnerability to different type of non-communicable diseases including hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases. Thus, context based interventions need to be designed on the prevention and control methods of overweight and obesity giving especial emphasis to those residing in urban areas.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank DHS program managers for allowing us to download and use the DHS dataset.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CI

Confidence interval

- DHS

Demographic and Health Surveys

- EDHS

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

- ICF

Inner City Fund

- OR

Odds Ratio

- SD

Standard deviation

- SNNPR

Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

AM, participated in all steps of the study from its commencement to writing of the final draft of the manuscript. BB and MW have participated in reviewing the paper, data analysis and interpretation of the findings. All the authors have reviewed and approved the submission of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its supporting files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Prior to conducting this research, an approval to download and use the EDHS 2016 datasets was obtained from the DHS program. The DHS program maintains appropriate ethical standards in all the surveys it conducts. In line with this, the 2016 EDHS was reviewed and approved by the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Science and Technology and the Institutional Review Board of ICF International. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant, and for adolescents less than 18 years consent was obtained from their parents/guardian and assent from them. Participation in the survey was completely based on willingness and with full autonomy to participate fully, partially and or to reject participation at any point of the interview. All participants’ information was processed anonymously and is labeled with only Identification codes in the EDHS dataset [14].

Consent for publication

Note applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ayelign Mengesha Kassie, Email: ayelignm@wldu.gov.et, Email: ayelignmengesha59@gmail.com.

Biruk Beletew Abate, Email: birukkelemb@gmail.com.

Mesfin Wudu Kassaw, Email: mesfine12a@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Fanzo J, Hawkes C, Udomkesmalee E, Afshin A, Allemandi L, Assery O, et al. Global Nutrition Report: Shining a light to spur action on nutrition. 2018. p. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) Global Database on Body Mass Index. BMI Classification. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobbs R, Sawers C, Thompson F, Manyika J, Woetzel J, Child P, et al. Overcoming obesity: An initial economic analysis. 2014. McKinsey & Company: www.mckinseycom/mgi. 2014. p. 1–106.

- 4.Chooi YC, Ding C, Magkos F. The epidemiology of obesity. Metabolism. 2019;92:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, Flint AJ, Hannan L, RJ MI, et al. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(23):2211–2219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabarés SR. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngu M, Fleming T, Robinson M. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. Jama. 2016;315(21):2284–2291. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World health organization. Obesity and overweight. Fact sheet N 311. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. 2012.

- 10.Bovet P, Chiolero A, Gedeon J. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1495–1496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1710026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgen CS, Sørensen TI. Obesity: global trends in the prevalence of overweight and obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(9):513. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yatsuya H, Li Y, Hilawe EH, Ota A, Wang C, Chiang C, et al. Global trend in overweight and obesity and its association with cardiovascular disease incidence. Circ J. 2014:CJ-14-0850. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Bhurosy T, Jeewon R. Overweight and obesity epidemic in developing countries: a problem with diet, physical activity, or socioeconomic status? Sci World J. 2014;2014:964236. doi: 10.1155/2014/964236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF International . Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarma H, Saquib N, Hasan MM, Saquib J, Rahman AS, Khan JR, et al. Determinants of overweight or obesity among ever-married adult women in Bangladesh. BMC obesity. 2016;3(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s40608-016-0093-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pouliou T, Elliott SJ. Individual and socio-environmental determinants of overweight and obesity in urban Canada. Health Place. 2010;16(2):389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pampel FC, Denney JT, Krueger PM. Obesity, SES, and economic development: a test of the reversal hypothesis. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(7):1073–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.APdS F, Szwarcwald CL, Damacena GN. Prevalence of obesity and associated factors in the Brazilian population: a study of data from the 2013 National Health Survey. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia. 2019;22:e190024. doi: 10.1590/1980-549720190024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamann A. Obesity update 2017. Diabetologe. 2017;13(5):331–341. [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Rhazi K, Nejjari C, Zidouh A, Bakkali R, Berraho M, Gateau PB. Prevalence of obesity and associated sociodemographic and lifestyle factors in Morocco. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(1):160–167. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010001825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monteiro CA, Moura EC, Conde WL, Popkin BM. Socioeconomic status and obesity in adult populations of developing countries: a review. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:940–946. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wardle J, Griffith J. Socioeconomic status and weight control practices in British adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(3):185–190. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.3.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.French S, Jeffery R, Forster J, McGovern P, Kelder S, Baxter J. Predictors of weight change over two years among a population of working adults: the healthy worker project. Int J Obes Relat Metab. 1994;18(3):145–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benkeser R, Biritwum R, Hill A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity and perception of healthy and desirable body size in urban, Ghanaian women. Ghana Med J. 2012;46(2):66–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diendéré J, Kaboré J, Somé JW, Tougri G, Zeba AN, Tinto H. Prevalence and factors associated with overweight and obesity among rural and urban women in Burkina Faso. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;34:199. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2019.34.199.20250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mndala L, Kudale A. Distribution and social determinants of overweight and obesity: a cross-sectional study of non-pregnant adult women from the Malawi demographic and health survey (2015-2016) Epidemiol Health. 2019;41:e2019039. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2019039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al Kibria GM, Swasey K, Hasan MZ, Sharmeen A, Day B. Prevalence and factors associated with underweight, overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in India. Global Health Res Policy. 2019;4(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s41256-019-0117-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abate BB, Kassie AM, Kassaw MW, Zemariam AB, Alamaw AW. Prevalence and determinants of stunting among adolescent girls in Ethiopia. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Central MO. Statistical Agency: Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2005. Calverton: ORC Macro; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.CSA . Central statistical agency [Ethiopia] and ICF international. Maryland, USA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Calverton: Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2010; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das Gupta M, Engelman R, Levy J, Gretchen L, Merrick T, Rosen JE. The Power of the 1.8 Billion, Adolescents, Youth and the Transformation of the Future, State of World Population. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(1):3–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amegah A, Lumor S, Vidogo F. Prevalence and determinants of overweight and obesity in adult residents of cape coast, ghana: A hospital-based study. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2011;11(3).

- 34.Mogre V, Mwinlenaa P, Oladele J, Amalba A. Impact of physical activity levels and diet on central obesity among civil servants in Tamale metropolis. J Med Biomed Sci. 2012;1(2).

- 35.Pobee RA, Owusu W, Plahar W. The prevalence of obesity among female teachers of Child-bearing age in Ghana. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2013;13(3).

- 36.Subramanian SV, Perkins JM, Özaltin E, Davey SG. Weight of nations: a socioeconomic analysis of women in low- to middle-income countries. Am J ClinNutr. 2011;93:413–421. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atek M, Traissac P, El Ati J, Laid Y, Aounallah-Skhiri H, Eymard Duvernay S, et al. Obesity and association with area of residence, gender and socio-economic factors in Algerian and Tunisian adults. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Letamo G. The prevalence of, and factors associated with, overweight and obesity in Botswana. J BiosocSci. 2011;43:75–84. doi: 10.1017/S0021932010000519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sola AO, Steven AO, Kayode JA, Olayinka AO. Underweight, overweight and obesity in adults Nigerians living in rural and urban communities of Benue state. Ann Afr Med. 2011;10:139–143. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.82081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ojiambo RM, Easton C, Casajús JA, Konstabel K, Reilly JJ, Pitsiladis Y. Effect of urbanization on objectively measured physical activity levels, sedentary time, and indices of adiposity in Kenyan adolescents. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(1):115–123. doi: 10.1123/jpah.9.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Assah FK, Ekelund U, Brage S, Mbanya JC, Wareham NJ. Urbanization, physical activity, and metabolic health in sub-Saharan Africa. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):491–496. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sengupta A, Angeli F, Syamala TS, Dagnelie PC, Van Schayck C. Overweight and obesity prevalence among Indian women by place of residence and socio-economic status: contrasting patterns from ‘underweight states’ and ‘overweight states’ of India. Soc Sci Med. 2015;138:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bishwajit G. Household wealth status and overweight and obesity among adult women in B angladesh and N epal. Obes Sci Pract. 2017;3(2):185–192. doi: 10.1002/osp4.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goryakin Y, Suhrcke M. Economic development, urbanization, technological change and overweight: what do we learn from 244 demographic and health surveys? Econ Hum Biol. 2014;14:109–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.El-Hazmi M, Warsy A. Relationship between age and the prevalence of obesity and overweight in Saudi population. Bahrain Med Bull. 2002;24:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dake FA, Tawiah EO, Badasu DM. Sociodemographic correlates of obesity among Ghanaian women. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(7):1285–1291. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duda RB, Darko R, Seffah J, Adanu RM, Anarfi JK, Hill AG. Prevalence of obesity in women of Accra, Ghana. Afr J Health Sci. 2007;14:154–159. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reas DL, Nygård JF, Svensson E, Sørensen T, Sandanger I. Changes in body mass index by age, gender, and socio-economic status among a cohort of Norwegian men and women (1990–2001). BMC Public Health. 2007;7. 10.1186/1471-2458-7-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Li W, Wang Y, Shen L, Song L, Li H, Liu B, et al. Association between parity and obesity patterns in a middle-aged and older Chinese population: a cross-sectional analysis in the Tongji-Dongfeng cohort study. NutrMetab. 2016;13. 10.1186/s12986-016-0133-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Bhavadharini B, Anjana RM, Deepa M, Jayashree G, Nrutya S, Shobana M, et al. Gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes in relation to body mass index in Asian Indian women. Indian J EndocrinolMetab. 2017;21:588–593. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_557_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kominiarek MA, Peaceman AM. Gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Hales CM, Carroll MD, Aoki Y, Freedman DS. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographics and urbanization in US children and adolescents, 2013-2016. Jama. 2018;319(23):2410–2418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.5158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, Aoki Y, Ogden CL. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographic characteristics and urbanization level among adults in the United States, 2013-2016. Jama. 2018;319(23):2419–2429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bochi RW, Kuria E, Kimiywe J, Ochola S, Steyn NP. Predictors of overweight and obesity in adult women in Nairobi Province, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:823. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.French SA, Wall M, Mitchell NR. Household income difference in food sources and food items purchased. Int J BehavNutrPhys Act. 2010;7:77. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lopez LM, Edelman A, Chen M, Otterness C, Trussell J, Helmerhorst FM. Progestin-only contraceptives: effects on weight. In: the Cochrane collaboration, editor. Cochrane databaseof systematic reviews. Chichester: Wiley; 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ntoja M, Medeiros T, Baccarin MC, Morais SS, Bahamondes L, dos Santos Fernandes AM. Variations in body mass index of users of depot- medroxyprogesterone acetate as a contraceptive. Contraception. 2010;81:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kibria A, et al. Global health research and policy (2019) 4:24 page 11 of 12medroxyprogesterone acetate as a contraceptive. Contraception. 2010;81:107–111. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its supporting files.