Abstract

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) constitute a unique population of bone marrow-derived cells that play a pivotal role in linking innate and adaptive immune responses. While peripheral tissues are typically devoid of pDCs during steady state, few tissues do host resident pDCs. In the current study, we aim to assess presence and distribution of pDCs in naïve murine limbus and bulbar conjunctiva. Immunofluorescence staining followed by confocal microscopy revealed that the naïve bulbar conjunctiva of wild-type mice hosts CD45+ CD11clow PDCA-1+ pDCs. Flow cytometry confirmed presence of resident pDCs in the bulbar conjunctiva and showed that they express maturation marker, co-inhibitory molecules PD-L1 and B7-H3, and minor to negligible levels of co-stimulatory molecules CD40, CD86, and ICAM-1. Epi-fluorescent microscopy of DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− transgenic mice with GFP-tagged pDCs indicated lower density of pDCs in the bulbar conjunctiva compared to the limbus. Further, intravital multiphoton microscopy revealed that resident pDCs accompany the limbal vessels and patrol the intravascular space. In vitro multiphoton microscopy showed that pDCs are attracted to human umbilical vein endothelial cells and interact with them during tube formation. In conclusion, our study shows that the limbus and bulbar conjunctiva are endowed with resident pDCs during steady state, which express maturation and classic T cell co-inhibitory molecules, engulf limbal vessels, and patrol intravascular spaces.

Keywords: Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell, Conjunctiva, Limbus, Vascular Endothelial Cell, Intravital Microscopy

INTRODUCTION

Since the initial description of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) by the pathologists Lennert and Remmele in 1958, several aspects of their vital properties in immune response have emerged.1 They were initially categorized as lymphoblasts, purely based on their localization in interfollicular areas of human reactive lymph nodes and their morphology.1 In 1980s, availability of lineage markers enabled detection of some T-cell markers including CD4 (OKT4) on these cells, which along with their well-developed rough endoplasmic reticulum, resembling plasma cells, led to re-naming them to plasmacytoid T cells2, 3, 4, 5, 6 or T-associated plasma cells.7 By further immunophenotyping, Facchetti et al. demonstrated expression of several myelomonocytic markers and lack of granulocytes, B or T cell associated antigens including CD20, CD22, or T cell receptor component CD3 on these cells, designating them as plasmacytoid monocytes.8 Later, extensive studies showed that plasmacytoid T cells/monocytes can differentiate into mature conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) in vitro, coining the term plasmacytoid pre-dendritic cells and later pDC for them.9 Eventually, in late 1990s, Siegal et al. noticed the phenotypic similarities between pDCs and natural interferon-producing cells (IPCs)10, 11, 12, 13 and found that pDCs can secret large amounts of interferon-α (IFN-α).14 This observation, confirmed by others,15, 16 provided the necessary evidence to conclude pDCs and IPCs represent the same cell entity.

Although pDCs share many features with cDCs, such as sensing pathogens and the capacity to capture and present antigens,17 they show distinct properties, which contrast cDCs. For instance, in marked contrast to cDCs, pDCs exhibit no dendrites in blood smears and contain abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum, numerous mitochondria, and a small Golgi apparatus in scanning electron microscopy.18 Further, contrary to cDCs, pDCs express recombination-activating gene products, exhibit D-J rearrangements of immunoglobulin heavy chains,19 and express high levels of endosomal receptors, toll-like receptor (TLR)-7 and −9, which enables them to recognize single stranded RNA and double stranded DNA of pathogens, respectively.20, 21

Multifaceted properties of pDCs enable a broad spectrum of immune responses, ranging from pathogen challenges to tumor immunology and atherosclerosis.22, 23, 24, 25, 26 During antiviral immunity, they serve as the first line of defense, through their early production of IFN-α,14, 16, 27 as well as indirectly by bridging innate and adaptive immune responses through activating, attracting, and differentiating natural killer cells (NK),28, 29 T cells,30 as well as B cells, and plasma cells.31, 32 pDCs also modulate adverse immune reactions by inducing tolerance through several strategies. They express 2,3-indoleamine dioxygenase,33 and promote CD4+ and CD8+ T regulatory cell (Treg) differentiation.34, 35, 36, 37 They also enhance secretion of interleukin (IL)-10 by inducible T-Cell co-stimulator (ICOS)-expressing Tregs,38 and additionally reduce the proliferative capacity of alloreactive T cells.39, 40 Recently, it has been shown that pDCs in gut-associated lymphoid tissues are key player in establishing oral tolerance by inhibiting antigen-specific T cells, followed by generation of regulatory T cells.41, 42 pDCs are constantly generated in the bone marrow and subsequently enter the blood stream, where they constitute 0.2–0.8% of mononuclear cells. 18,43, 44 pDCs then home to the thymus, spleen, liver, lymph nodes, mucosal-associated lymphoid tissues, and Peyer’s patches.9, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51 Although pDCs can be recruited to the sites of inflammation in peripheral tissues during disease, current evidence suggests that they are typically confined to lymphoid tissues during steady state.

The conjunctiva is the mucosal barrier protecting the ocular surface and is divided into the bulbar conjunctiva, which covers the majority of the ocular surface, and the tarsal conjunctiva, which lines the inner surface of the eyelids. In addition to contributing mucin to the tear film, as a common feature of mucosal barriers, the conjunctiva plays an active role in mediating immune responses following exposure to antigens from the external environment.52, 53 In addition, similar to the gut, the conjunctiva can induce tolerance to foreign antigens under physiological conditions. However, our knowledge is currently limited on mechanisms through which tolerance is maintained in the conjunctiva. Considering recent findings on the presence and critical role of pDCs in inducing tolerance in mucosal tissue of gut,41, 42 we aimed to assess if the conjunctiva, another mucosal tissue, and the limbus host resident pDCs during steady state.

In the current study, we report the presence of resident pDCs in the bulbar conjunctiva and limbus of wild-type mouse during steady state. We observe higher density of pDCs in the limbus, where they line limbal vessels and patrol the intravascular spaces. We also demonstrate that pDCs residing in the naïve bulbar conjunctiva are mature and express T cell co-inhibitory and lower to negligible co-stimulatory markers. We further show that pDCs are attacked to vascular endothelial cells and interact with them in vitro during endothelial cell tube formation.

Methods

Mice.

Wild-type 6–8-week-old C57BL/6N mice were obtained through Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA); DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− transgenic mice were kindly provided by Dr. Ulrich H. von Andrian (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) and were bred in house at the animal facilities of Schepens Eye Research Institute and Tufts Comparative Medicine Services, Tufts Medical Center. Experiments were performed in concordance with the Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Visual Research (Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology) and were approved by the respective Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Epi-fluorescence Microscopy.

DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− transgenic mice at 6–8 weeks of age underwent fluorescent microscopy by Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope (Nikon Inc. Melville, NY) with an Andor Clara E digital camera (Andor Technology Ltd., Belfast, UK). Images from the superior and inferior bulbar conjunctiva and limbus were taken. GFP+ cells were quantified in the limbus (considered as the area between two lines, delineating the limbal vessels, which were set 100 μm apart) and bulbar conjunctiva in each image by ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Numbers were then transformed (based on the area of the imaged used for quantification) to report cell density (cells/mm2).

Immunofluorescence (IF) Staining and Confocal Microcopy.

Upon euthanizing naïve C57BL/6N mice, the bulbar conjunctiva was excised, fixed in chilled acetone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 15 min at room temperature (RT). Following three washings with PBS, tissues were blocked in 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich) containing 1% anti-CD16/CD32 Fc receptor (FcR) mAb (Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH) for 30 min at RT. Afterwards, samples were incubated with fluorophore-conjugated CD45 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA), CD11c (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and PDCA-1 (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) antibodies for 90 min at RT. Following three washings with PBS, sampled were mounted with mounting media with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and underwent confocal microscopy with Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc, Mannheim, Germany). Three images were taken from each sample. Imaris (Bitplane USA, Concord, MA) was used to quantify the cells and the numbers were converted to represent cell density (cells/mm2).

Conjunctival Single Cell Suspension and Flow Cytometry.

Following euthanizing naïve C57BL/6N mice (n = 6–8), bulbar conjunctivas were excised, pooled and cut into small pieces, and incubated with 2mg/ml collagenase D and 0.05 mg/ml DNAse (both Roche, Indianapolis, IN) for 45 min at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Subsequent to applying ice cold FACS buffer, samples were filtered through a 40 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon, Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) to remove undigested debris. Filtered single cells were then centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min and blocked with 2% BSA containing 1% anti-CD16/CD32 FcR mAb in RT. Samples were stained with LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and combinations of fluorophore conjugated CD45, PDCA-1, Ly-6C, CD11b, F4/80, Ly-6G, CD3, CD19, program death ligand (PD-L)1, B7-H3, CD40, CD86, intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 (all BioLegend), CD11c, major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-II (I-A/I-E; both BD Biosciences), Ly49Q (MBL International, Woburn, MA) or their respective isotype controls (all BioLegend or BD Biosciences) for 30 min at RT to prepare antibody-stained samples, single isotype controls, and fluorescence minus one staining controls. Following washing the single cell solution with PBS, samples were re-suspended in 4% paraformaldehyd (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) and assessed by BD LSR II Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data was later analyzed by FlowJo v9.1 (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR). Experiments were repeated three times.

Flow Cytometric Sorting.

To enhance flow cytometric sorting yield of GFP+ pDCs for in vitro experiments, 6–8-week-old DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− transgenic mice were injected with 106 FLT3L-secreting melanoma cells. 10–14 days later, mice were euthanized, spleens were harvested, and mechanically dissociated using a sterile syringe plunger. Cells were then filtered through a 40 μm cell strainer. Red blood cells were lysed using Ammonium-Chloride-Potassium (ACK) lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Single splenic cells were then washed and GFP+ pDCs were sorted using a MoFlo Astrios EQ (Beckman Coulter Inc, Brea, CA). Gating strategy for sorting is illustrated in Fig. S1.

Intravital Multi-photon Microscopy (IV-MPM).

6–8-week-old DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− transgenic mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg), xylazine (10 mg/kg), and acepromazine (1 mg/kg). IV-MPM was performed as previously described with modifications.54 In brief, mice were placed on a custom-made stage for ocular intravital imaging (Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA) and prepared for imaging. Proparacaine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution (Akorn Inc., Lake Forest, IL) and GenTeal lubricant eye gel (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) were applied on the eye. In 4D analysis, QTRACKER™ Qdot™ 655 (Qdot; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was administered intravenously, per manufacturer’s instructions to visualize the vessels. To maintain the ocular surface temperature, polyethylene tubing (PE #20; BD Intramedic, Sparks, MD) carrying hot water was passed through a pipet tip (Fig. S2); the body of the tip was trimmed to fit a coverslip on top and to allow the narrow end to accommodate a digital thermometer (Fig. S2); vacuum grease (Dow Corning high-vacuum silicone grease; Sigma-Aldrich) was applied over the coverslip to form a sealed space for application of GenTeal gel, in which the objective lens was immersed (Fig. S2). The mouse eye was then placed inside the pipet tip filled with GenTeal gel. The ocular surface temperature was monitored via a digital thermometer (model HH12B; OMEGA Engineering Inc. Norwalk, CT) and maintained within 35–36˚C, as physiological ocular surface temperature via water tubing connected to a hot water bath and a water pump (Masterflex L/S peristaltic pump, Cole Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL). The limbus and bulbar conjunctiva were imaged via an upright multi-photon Ultima microscope (Prairie Technologies, Inc., Middleton, WI) with MaiTai Ti/Sapphire lasers (SpectraPhysics, Santa Clara, CA) set at 750 nm and 900 nm wavelengths, with 2–3 μm step sizes, photomultiplier tube (PMT) gain at 950 for all channels, and two-fold line averaging to yield 512×512 resolution images. Image analysis, including reconstruction of 3D and 4D movies, for measurement of cell densities and vascular diameters was performed using Imaris (Bitplane). Vessels were divided into three groups based on their mean diameter (average diameter of the vessel at its both ends): small (vessel diameter < 15 μm), medium (vessel diameter ≥ 15 μm and <25 μm), and large (vessel diameter ≥ 25 μm) vessels.

Cell Culture.

FLT3L-secreting B16 melanoma cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Ulrich H. von Andrian (Harvard Medical School). Cells were cultured with RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini Bioproducts, Woodland, CA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), 15mM HEPES (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1mM sodium pyruvate (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 1mM 2- Mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich).

In vitro MPM.

16h-serum starved HUVECs (passages 3–8; ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured with EBM2 (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 10% FBS on a 6-well plate after coating with phenol red-free Matrigel Growth Factor Reduced Basement Membrane Matrix (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) for 4h to establish endothelial tubes. Next, cells were stained with CellTracker™ Blue CMAC Dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Next, 3×105 freshly sorted splenic GFP+ pDCs of DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− cells were added to the culture and the plate was placed in a custom-made chamber (Tufts Medical Center) regulating temperature using hot water tubing (BD Intramedic). Co-cultures were imaged with the multi-photon Ultima microscope with lasers set at 810 nm and 880 nm wavelengths, with 1–2 μm step sizes, PMT gain at 950 for all channels, and two-fold line averaging. Acquired images were reconstructed with Imaris (Bitplane).

Statistical Analysis.

Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis. Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation. ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test and student T test were applied to compare the means between two groups, where appropriate. p less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Reside in the Naïve Bulbar Conjunctiva

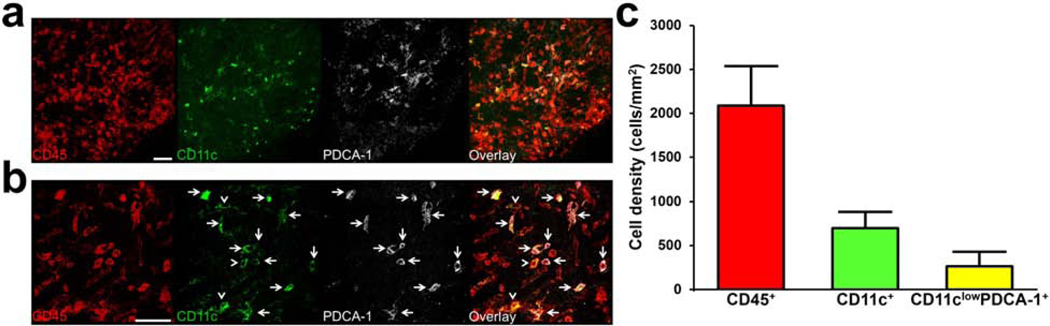

In order to assess if pDCs are present in the naïve bulbar conjunctiva, we initially performed IF staining with CD45 (pan-leukocyte marker), CD11c (cDC and pDC marker), and PDCA-1 (pDC marker) on the excised bulbar conjunctival whole-mounts of naïve wild-type C57BL/6N mice. As demonstrated in Fig. 1a, we observed a population of CD45+ CD11clow PDCA-1+ cells in the naïve bulbar conjunctiva. Fig. 1b demonstrates a magnified confocal micrograph of CD45+ CD11clow PDCA-1+ cells in this tissue. As shown in Fig. 1c, CD45+ CD11clow PDCA-1+ cells constitute 12.7% of bone-marrow derived (CD45+) cells in the bulbar conjunctiva, suggesting that the normal conjunctiva may host resident pDCs during steady state.

Figure 1. Identification of resident plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the naïve murine bulbar conjunctiva.

Representative confocal micrograph of whole mount bulbar conjunctiva of naïve C57BL/6N mouse stained with CD45 (pan-leukocyte marker; red), CD11c (conventional and plasmacytoid dendritic cell marker; green), and PDCA-1 (specific pDC marker; white), showing triple-stained CD45+ CD11clow PDCA-1+ pDCs with white arrows at lower (a) and higher (b) magnification. White arrow heads indicate double stained CD45+ CD11c+ PDCA-1neg conventional dendritic cells. Quantification of density of CD45+ bone marrow-derived cells, CD11c+ conventional and CD11clow PDCA-1+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the bulbar conjunctiva of naïve mice (n=3) (c). Error bars; standard deviation, scale bars; 50 μm

Flow Cytometric Phenotyping of Resident Conjunctival Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells

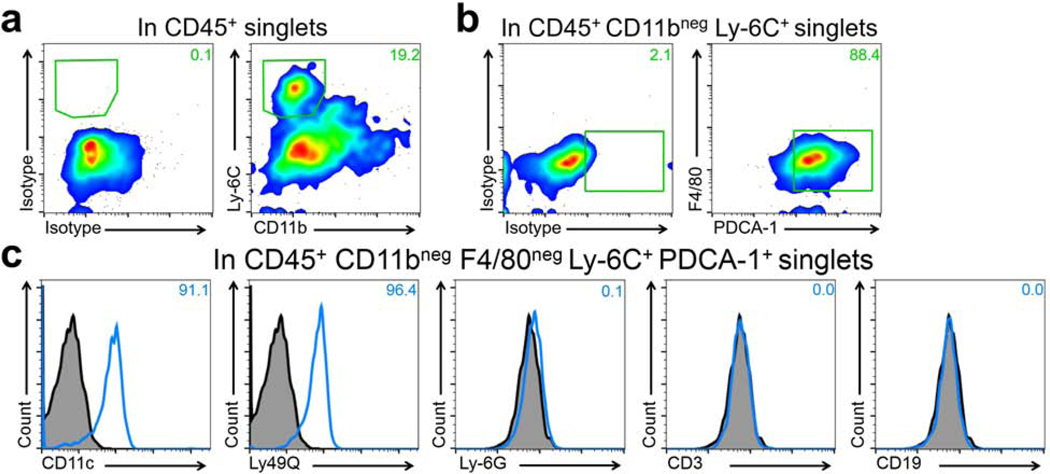

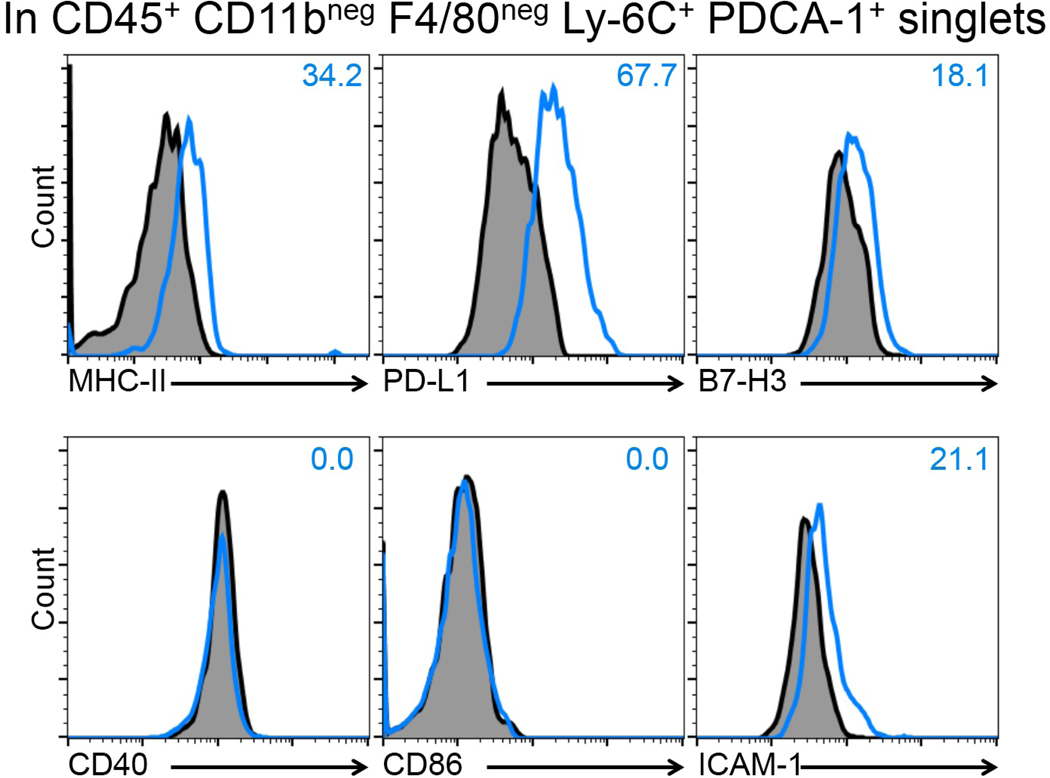

Having observed the presence of CD45+ CD11clow PDCA-1+ cells in the bulbar conjunctiva by confocal microscopy during steady state, we next aimed to verify the identity of pDCs in this tissue. Thus, we performed flow cytometry on conjunctival single cell suspensions of naïve mice using multiple markers to confirm the identify pDCs and to rule out potential auto-fluorescence. As demonstrated in Fig. S3, we sequentially removed debris and dead cells and gated on singlets and CD45+ cells. We observed that approximately 19.2% of CD45+ cells express Ly-6C but are negative for CD11b (Fig. 2a). Gating on this population revealed that the majority of CD45+ CD11bneg Ly-6C+ cells co-express PDCA-1 and lack F4/80, suggesting their identity as pDCs (Fig. 2b). To further confirm the identity of pDCs, we evaluated expression of CD11c, Ly-49Q, Ly-6G, CD3, and CD19 on this population. As presented in Fig. 2c, we observed that CD45+ CD11bneg F4/80neg Ly-6C+ PDCA-1+ cells co-express CD11c and Ly-49Q, but are negative for Ly-6G, CD3, and CD19, further validating their identity as pDCs. Next, in order to further phenotype resident pDCs, we assessed expression of the maturation marker MHC-II, as well as co-inhibitory and co-stimulatory molecules including PD-L1, B7-H3, CD40, CD86, and ICAM-1 by flow cytometry. As depicted in Fig. 3, our flow cytometric assessment showed that pDCs express moderate levels of MHC-II and co-inhibitory molecules PD-L1, lower levels of B7-H3, and ICAM-1, and are negative for CD40 and CD86 in the naïve bulbar conjunctiva. Thus, our findings confirm the presence of pDCs in the naïve bulbar conjunctiva, and suggests that they are relatively mature, expressing varying levels of classical co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory molecules during steady state.

Figure 2. Characterization of the resident plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the naïve bulbar conjunctiva by flow cytometry.

Excised bulbar conjunctiva of naïve C57BL/6N mice (pooled from 6–8 mice) were digested by collagenase D and DNAse to yield single cells. Afterwards, cells were stained with combinations of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD45 (pan-leukocyte marker), Ly-6C, PDCA-1, Ly-49Q, CD11c (expressed by pDCs), CD11b, F4/80, Ly-6G, CD3, CD19 or their respective isotype controls. After gating on live CD45+ singlets to present bone marrow-derived cells, CD11bneg Ly-6C+ cells were selected (a). Next, among CD45+ CD11bneg Ly-6C+ cells, F4/80neg PDCA-1+ cells were selected, representing a population of CD11bneg F4/80neg Ly-6C+ PDCA-1+ cells among CD45+ cells in the bulbar conjunctiva (b). Histogram of flow cytometry analysis reveals that CD45+ CD11bneg F4/80neg Ly-6C+ PDCA-1+ cells in naïve conjunctiva are in fact pDCs as they express CD11c and Ly-49Q, and are negative for Ly-6G, CD3, and CD19 (c). Fluorescence minus one isotype control staining is presented in gray and staining with designated antibodies are presented in blue open histograms. Plots are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 3. Immunophenotyping of the conjunctival plasmacytoid dendritic cells by flow cytometry.

Digested single cell suspension of bulbar conjunctiva of naïve C57BL/6N mice (pooled from 6–8 mice) were labeled with combinations of CD45, CD11b, F4/80, Ly-6C, PDCA-1, PD-L1, B7-H3, CD40, CD86, ICAM-1, MHC-II (I-A/I-E) antibodies, or their respective isotype controls. Blue open histograms represent expression of T cell co-inhibitory and co-stimulatory markers of PD-L1, B7-H3, CD40, CD86, ICAM-1 as well as maturity marker MHC-II on resident pDCs (identified as CD45+ CD11bneg F4/80neg Ly-6C+ PDCA-1+ singlets) in naïve mouse. Fluorescence minus one isotype control background staining is depicted in dark profile. Plots are representative of 3 independent experiments.

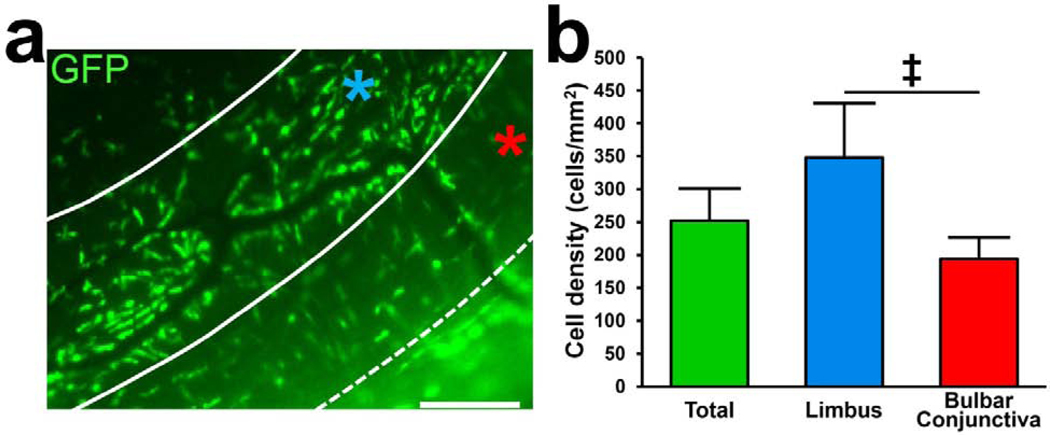

Distribution of Resident Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in the Naïve Limbus and Bulbar Conjunctiva

After verifying the presence of pDCs in the naïve bulbar conjunctiva, we aimed to evaluate the distribution of pDCs in bulbar conjunctiva and limbus. To avoid potential artifacts introduced by the staining process and to rule out non-specific staining with antibodies, we took advantage of transgenic naïve DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mice in which pDCs solely express GFP.55 Epi-fluorescent microscopy on unstained DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mice confirmed our IF staining and confocal microscopy findings, demonstrating the presence of GFP+ pDCs in the bulbar conjunctiva and limbus. Although we did not observe significant differences in the density of pDCs between the superior and inferior bulbar conjunctiva (201.0 ± 45.2 cells/mm2 vs. 186.8 ±18.7 cells/mm2, respectively; p=0.58) or superior and inferior limbus (354.0 ± 117.3 cells/mm2 vs. 342.0 ± 45.3 cells/mm2, respectively; p=0.86; Fig. S4), pDC density was significantly higher in the limbus (348.0 ± 82.6 cells/mm2) in comparison to the bulbar conjunctiva (193.2 ± 32.9 cells/mm2, p=0.001; Fig 4). We also noted that in the limbus, pDCs are organized parallel to structures resembling limbal vessels, suggesting that they may line the outer surface of vessels with their long stellates (Fig. 4a). Thus, our observations suggest that pDCs are distributed comparably among superior and inferior parts of the limbus and bulbar conjunctiva; however, they are more densely populated in the limbal area, where they may reside in close proximity to vasculature.

Figure 4. Distribution of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the limbus and bulbar conjunctiva.

Representative fluorescent microscope image of the limbus and bulbar conjunctiva of naïve DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mice in which pDCs solely express GFP (a). Limbus (indicated by blue star) is defined as the area between two arbitrary solid lines, 100 μm apart, parallel to limbal vessels, and bulbar conjunctiva is marked by the red star, considered as the area between dash and solid lines. Scale bar; 50 μm. Quantification of the density of the pDCs in the limbus and the bulbar conjunctiva (n=8), indicating higher density of pDCs in the limbus (b). Error bars; standard deviaaon, ‡; p=0.001

Multi-photon Microscopy of GFP-tagged Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Reveals Their Structural Properties in the Bulbar Conjunctiva and Limbus

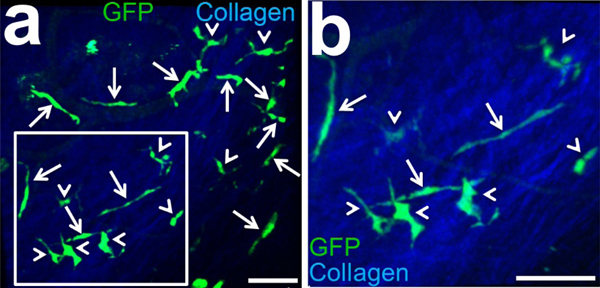

After depicting the preferred localization of pDCs in the limbus, we next assessed morphologic properties of pDCs in the bulbar conjunctiva and limbus of naïve DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mice. IV-MPM confirmed presence of GFP+ pDCs in the bulbar conjunctiva and limbus of live DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mice and allowed us to assess localization and morphology of these pDCs in these peripheral tissues with a high resolution. We noticed that in the bulbar conjunctiva, pDCs exhibited two distinct morphologies; while some were comprised of an ovoid thin cell body (small diameter less than 10 μm) with two elongated polar stellates extending about 22.1–79.4 μm, others showed larger cell bodies (with diameters of approximately 10 μm) with shorter, but higher number of stellates (Fig. 5 a, b). Further, we assessed the location of pDCs in different structural layers of the limbus and bulbar conjunctival. As evident in the Movies S1 and S2, pDCs were located in the substantia propria of the bulbar conjunctiva (Movie S1) and limbal tissue (Movie S2), judged by their unique distribution among collagenous content of bulbar conjunctiva and limbus visualized by second harmonic generation.

Figure 5. Multiphoton micrograph of the limbus and bulbar conjunctiva of GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− transgenic mouse in homeostatic state.

Intravital MPM of limbus and bulbar conjunctiva of DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mouse with specifically GFP-tagged pDCs, reveals presence of resident GFP+ pDCs in these tissues (a). Inset is magnified two folds in (b). Note two distinct morphologies of pDCs; pDCs with two thin polar elongated stellates (white arrows) and pDCs with shorter but usually more stellates and thicker cell bodies (white arrow heads). Scale bars; 50 μm

Resident Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Patrol Limbal Vessels During Steady State

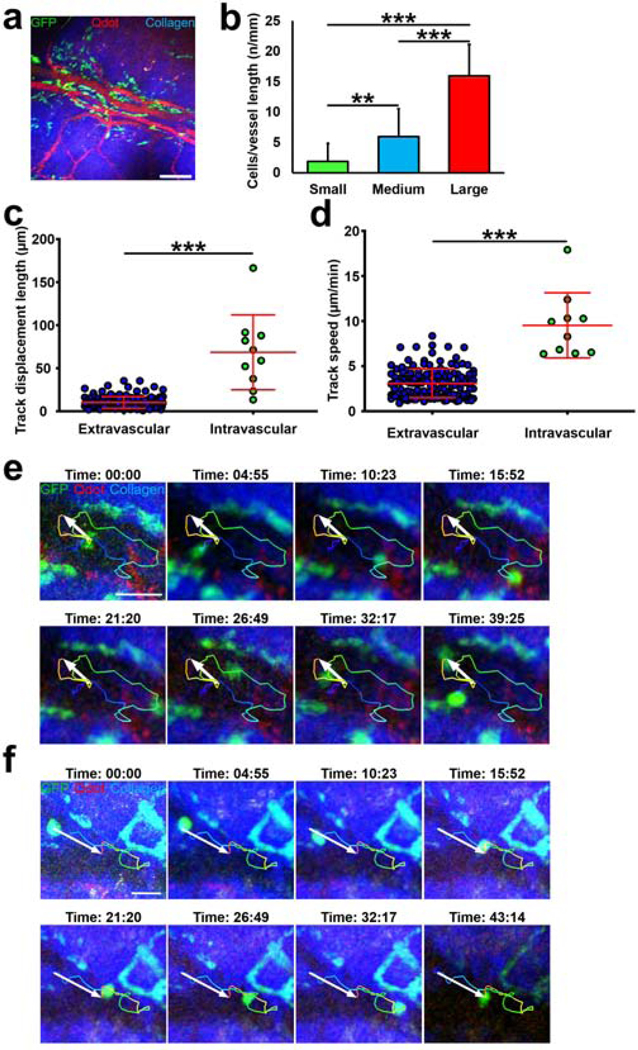

Observing close proximity of pDCs with structures resembling limbal vessels using epi-fluorescent microscopy and being able to visualize pDCs by MPM, we next sought to assess if pDCs in fact line the limbal vessels. Thus, we performed IV-MPM on the limbus of naïve DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mice following intravenous administration of Qdots to visualize the vessels. As presented in Fig. 6a, we observed that GFP+ pDCs were indeed in close proximity with limbal vessels. In comparison to the bulbar conjunctiva, higher frequency of pDCs were in close proximity to vessels in the limbus (29.8% ± 7.9 vs. 85.2% ± 9.3 respectively; p<0.001). To better understand the distribution of GFP+ pDCs in the limbus in relation to vessels, we categorized vessels to three groups of small, medium, and large vessels, according to their vessel diameter. As illustrated in Fig. 6b, larger vessels tend to have more pDCs accompanying them compared with medium and small vessels (p<0.001). We next sought to assess if pDCs interact with limbal vessels in vivo. As presented in Movie S3, IV-MPM showed that while the majority of pDCs reside outside of the limbal vessels with subtle movements during steady state, a few of them patrol intravascular space close to vascular endothelial lining. Notably, intravascular pDCs appeared to show longer displacement (Fig. 6c) with a higher mean speed (Fig. 6d). These intravascular pDCs were able to move towards and backwards vascular flow and exhibited various migratory patterns including loops (Fig. 6e; Movie S4), rolling, crawling, and mixed patterns (Fig. 6f; Movie S5). Thus, our observations confirm the close proximity of resident pDCs with the vasculature, in particular in the limbus, and further indicate that pDCs may reside in the vascular lumen, and exhibit intravascular patrolling behavior.

Figure 6. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells reside in close proximity to limbal vessels and patrol intravascular spaces.

Representative multi-photon micrograph of the limbus of naïve DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mice injected with Qdot (a). Quantification of density of pDCs in contact with limbal vessels based on vessel diameter (b). (c-d) Comparison of track displacement length (c) and mean speed (d) between extravascular and intravascular pDCs. (e, f) Representative still images of quantified track of an intravascular pDC, resembling moving in a loop (e) and mixed crawling and loop pattern (f). Error bars; standard deviation, ***; p<0.001, scale bar; 200 μm in (a) and 50 μm (e, f)

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells migrate towards endothelial cell tubes in vitro

Following our in vivo studies indicating that pDCs are in close contact with limbal vessels, we aimed to evaluate if pDCs migrate towards and directly interact with endothelial cells. Thus, we performed in vitro MPM of pDCs/HUVEC co-cultures. We added 3×105 freshly sorted splenic pDCs from DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mice (as illustrated in Fig. S1) with HUVECs undergoing tube formation. We observed that pDCs are attracted to formed tubes of endothelial cells, in particular at branching points (63.9 ± 9.6% of total pDCs) compared to pDCs in contact with tube walls (23.6 ± 3.1% of total pDCs). However, they were rarely found inside of formed lumens where endothelial cells were not present (12.5 ± 10.0% of total pDCs). Further, we demonstrated that pDCs actively interact with endothelial cells during tube formation (Movie S6).

DISCUSSION

In homeostatic conditions, distribution of pDCs is largely limited to primary and secondary lymphoid organs. Our study demonstrates that pDCs reside in the naïve bulbar conjunctiva as well as limbus. We show that pDCs are less frequently located in the bulbar conjunctiva in comparison with limbus where they accompany limbal vessels. To verify presence of pDCs in these peripheral tissues, we applied three different laboratory methodologies. Initially, we performed fluorescence immunostaining on whole-mount samples with two pDC markers, imaged by confocal microscopy. Next, we applied flow cytometry on conjunctival single cell suspensions using multiple markers and performed sequential gating to confirm the presence of resident pDCs and to phenotype maturation and activation state of pDCs in the bulbar conjunctiva using fluorescence minus one controls. Finally, we took advantage of a transgenic mouse model with GFP+ pDCs and performed multi-photon as well as fluorescent microscopy to avoid potential artifacts due to tissue handling, ex vivo manipulations, and non-specific staining to assess distribution and microscopic characteristics of resident pDCs in bulbar conjunctiva and limbus.

Although initial studies indicated that pDCs are derived from common lymphoid progenitors, later reports suggest that common myeloid progenitors also give rise to pDCs.19, 56, 57 In fact, generation of pDCs might be more flexible than other immune cells, which could be derived from either lymphoid or myeloid precursors.58 However, pDCs lack expression of typical lineage markers characteristic of lymphoid (T, B, or NK) and myeloid (monocyte, granulocyte) cells, such as CD3, CD19, CD20, CD14, CD16, or CD65.18, 59 Although pDCs are found in a variety of laboratory animals including mice,60, 61, 62 rats,63 pigs,64, 65 and sheep66 as well as non-human primates,67 studying their properties is underappreciated due to several factors. pDCs are found in few numbers in the body and they exhibit a complex immunophenotype. Further, currently there is no single specific marker available to identify pDCs. Noteworthy, PDCA-1 which was originally considered as a specific pDC marker, is now shown to be expressed by unique sparse populations of B cells68, 69, 70 and cDCs71 under homeostatic conditions. Moreover, expression of PDCA-1 does not remain restricted to pDCs in inflammatory settings, since many immune and non-immune cells begin expressing different levels of this molecule upon exposure to IFN.72 Similarly, Siglec-H, a lectin on the cell surface of murine pDCs, was initially regarded as the signature of pDCs; however, subsequent studies demonstrated that subsets of macrophages in the marginal zone of the spleen and in the medulla of the lymph nodes as well as microglia and pDC precursors also express Siglec-H.73, 74, 75 CD11c is another dendritic cell marker, which is highly expressed in murine cDCs, however, its expression is limited to low to intermediate levels in pDCs in mice, making solitary use of this marker for differentiating cDCs and pDCs challenging.49, 60, 61 Therefore, in this study we applied several markers expressed by pDCs including PDCA-1, Ly-6C, CD11c, and Ly49Q, as well as markers that pDCs do not express including CD11b, F4/80, Ly-6G, CD3, and CD19 to truly confirm the presence of pDCs in the conjunctiva.

Further, we observed that pDCs in the bulbar conjunctiva express MHC-II, moderate levels of co-inhibitory molecules PD-L1 and B7-H3 and minor to negligible levels of CD40, CD86, and ICAM-1, indicating that resident pDCs in peripheral tissues are in a relatively mature, active, and tolerogenic state. Freshly released pDCs from bone marrow express low levels of MHC-II and T cell co-stimulatory molecules, resting in an immature state;76 however, upon homing to secondary lymphoid organs, although still considered immature, they express higher levels of maturation and classic cell co-stimulatory markers.77, 78, 79, 80 In line with our findings, it is shown that pDCs continue undergoing maturation spontaneously, even in the absence of microorganisms or TLR-7 or −9 signaling.81 Nevertheless, upon stimulation by pathogens or recruitment to the site of inflammation, pDCs undergo maturation, reaching an advanced maturity state that is required for T cell engagement and priming.61, 82,83

Our observations suggest that pDCs are strategically located in close proximity to limbal vessels. Considering the particular extravascular arrangement of the pDCs close to the limbal vasculature, it would be interesting to study if pDCs located around the limbal vessels are derived after extravasation from the limbal vessels or migrated towards the vessels from the conjunctiva, or both. Also, although our study attests the presence of resident pDCs in the limbus and conjunctiva, unraveling their role in these tissues warrants further examination. Notably, we observed that pDCs are attracted to endothelial cells in vitro, interact with them during tube formation in vitro, engulf limbal vessels and patrol intravascular spaces in vivo. These findings suggest that pDCs may be implicated in various biological processes in the ocular surface. For instance, pDCs may participate in regulating vascular permeability and migration of other leukocytes to the conjunctiva and cornea in normal and inflamed states, as one of the first line of defense in the tissue. In line with this hypothesis, it has been shown that depletion of pDCs during influenza virus infection in mice may lead to increased infiltration of cDCs, monocytes, and macrophages;84 however, it is not clear if the observed increase in the density of immune cells is directly due to alterations in the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the tissue, or is linked to potential alterations in vascular permeability following pDC depletion. Furthermore, it would be intriguing to dissect the molecular mechanisms through which pDCs are attracted to vascular endothelial cells. In this regard, chemokines, as potent chemotactic cytokines may play a role. pDCs are shown to express CCR2, CCR5, CCR7, CXCR3, and CXCR4.85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93 On the other hand, depending on the their origin, blood or lymphatic endothelial cells may constitutively express CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL3 (MIP-1α), CCL4 (MIP-1β), CCL5 (RANTES), CCL21 (SLC), CXCL8 (IL-8), CXCL9 (MIG), CXCL10 (IP-10), CXCL12 (SDF-1).94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100 Thus, CCR2/CCL2, CCR5/CCL3, CCR5/CCL4, CCR5/CCL5, CCR7/CCL21, CXCR3/CXCL9, CXCR3/CXCL10, or CXCR4/CXCL12 axes may play a role in attraction of pDCs towards endothelial cells in vitro and their patrolling movements in the vascular lumen in vivo. While, activation of some of these chemokine receptors on pDCs, including CCR7 and CXCR3, only marginally induces migration of pDCs, exposure of pDCs to chemokines, such as CXCL12, remarkably enhances migration of pDCs in response to CCR7 or CXCR3 ligands.85, 87, 88, 89 Thus, in a similar fashion, a combination of chemokine and chemokine receptors may act in concert to mediate pDC attraction towards vascular endothelial cells.

Previously, it has been reported that a subpopulation of monocytes defined as non-classical monocytes also patrol vasculature.101 These monocytes are identified as Ly-6Cneg CD43+ in mice and express high levels of CX3CR1;102 nevertheless, in contrast to the observed pDCs which reside outside and in the main limbal vessels, they are typically found in capillaries;103 however, they can also be visualized in small blood arteries and veins.101 It has been shown that patrolling non-classical monocytes can uptake microparticles and cellular debris101, 103 and induce tolerance to apoptotic cell components while presenting them to T cells in the spleen.104 In a similar manner, it may be postulated that pDCs reside in close proximity to the vasculature to facilitate transfer of detected antigens to the systemic circulation or draining lymph nodes to either promote effector T cell priming and differentiation or tolerance. In this regard, it has been shown that while travelling to draining lymph nodes, cDCs initially crawl and frequently turn inside the vascular lumen, prior to migrating to the draining lymph nodes.99, 105 Thus, intravascular pDCs, which crawl inside the vascular lumen towards and against the flow direction, might in fact represent pDCs egressing from the cornea and may therefore participate in intravascular immune surveillance.

Further, pDCs may play a role in mediating vascular maintenance, repair, or development. Interestingly, it is shown that immune cells including monocyte and macrophages provide endothelial cells with a broad range of growth factors and cytokines106, 107, 108 and thus play a pivotal role in endothelial cell repair and function following wounding and regulation of angiogenesis.109, 110 To study involvement of pDCs to any of these processes, further studies are paramount.

In addition to the postulated roles stemmed from their close localization with vessels and patrolling behavior, resident pDCs may exert other functions. Noteworthy, sparse numbers of pDCs have recently been detected in vagina and lung, where they screen for viral encounter and govern anergy to allergens, respectively.27, 111 Since pDCs are known for their vital role in viral immunity, they may be involved in microbial clearance in viral and to a lesser extent bacterial conjunctivitis, similar to the vagina. Further, considering that pDCs are involved in pathogenesis of several autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus,112, 113, 114, 115 psoriasis,116, 117, 118 and multiple sclerosis,119, 120, 121 in addition to notation of IFN-α signature in Sjögren’s syndrome,122, 123 they may play a role in progression of ophthalmic presentations of Sjögren’s syndrome or dry eye disease.124 In line with this hypothesis, while pDCs are not detected in salivary glands under homeostatic state,125 they infiltrate these glands in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.123 On the other hand, pDCs may play a tolerogenic role that induces immune unresponsiveness to a wide range of antigens, including tumor cells, oral126 and inhalatory allergens.111, 127, 128 Further, expression of higher levels of co-inhibitory molecules compared to minor levels of co-stimulatory molecules on resident pDCs in bulbar conjunctiva also suggests a potential tolerogenic role for them in this tissue, and thus their malfunction may contribute to pathogenesis of conditions such as allergic conjunctivitis.

In summary, we identified that the limbus and bulbar conjunctiva are endowed with resident population of pDCs via three approaches of IF staining and confocal microscopy, flow cytometry, and MPM of GFP+ pDCs. Further, we observed that pDCs are located with a higher density in the limbus where they align with limbal vessels, more densely with larger vessels and can patrol intravascular space. Resident pDCs in the limbus and bulbar conjunctiva were relatively mature and in tolerogenic state as they expressed MHC-II, higher levels of co-inhibitory molecules PD-L1 and B7-H3, and lower levels of co-stimulatory molecules CD40, CD86, and ICAM-1. Further studies are paramount to reveal functions of pDCs in these ophthalmic tissues.

Supplementary Material

10–14 days following subcutaneous administration of FTL3L-secreting B16 melanoma cells, spleen of DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mice were harvested. After retrieving splenic single cells and lysis of RBCs, GFP+ pDCs were sorted. Representative flow cytometry dot plots representing gating out debris and dead cells (a), doublets (b), and sorting GFP+ pDCs. PE channel was used to avoid gating potential auto-fluorescent cells.

(a, b) Schematic illustration of the setup in top (a) and side (b) views. Mouse eye was placed between the coverslip and the pipet tip, exposing the limbus and bulbar conjunctiva. The room between the coverslip and the pipet tip was filled with GenTeal. Tubing containing circulating water was passed through the aforementioned room to maintain ocular surface temperature. Vacuum grease was applied on top of the coverslip to provide a top-opened room for immersion of objective lens. Actual pipet tip containing the water tube with a coverslip placed on top (c).

Quantification of GFP-tagged pDCs in the superior and inferior limbal area and bulbar conjunctiva of DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− transgenic mice indicates comparable density of pDCs in the superior and inferior limbus or bulbar conjunctiva (n=4).

Representative flow cytometric dot plot showing gating out debris (a), gating on live cells (b), and single cells (c). Next, CD45+ (d), Ly-6C+ (e), and CD11bneg cells were selected (f). Upper panel represents isotype staining unless otherwise specified and the lower panel illustrates corresponding staining with designated antibodies.

Movie S1. Reconstructed multi-photon micrograph of GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the naïve conjunctiva of a transgenic DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mouse, indicating pDCs are located in the substantia propria of bulbar conjunctiva during steady state.

Movie S2. Reconstructed multi-photon micrograph of GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the naïve limbus of a transgenic DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mouse, indicating pDCs are located in the substantia propria of limbal tissue during steady state.

Movie S3. Intra-vital multi-photon video of GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in naïve limbus of transgenic DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mouse injected with Qdot, shows pDCs residing in close proximity of vascular lumen as well as pDCs patrolling intravascular space.

Movie S4. Intra-vital multi-photon video of GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in naïve limbus of a transgenic DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mouse indicating characteristic kinetics of an intravascular pDC resembling a loop.

Movie S5. Intra-vital multi-photon video of GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in naïve limbus of a transgenic DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mouse representing mixed crawling and loop migratory kinetics of an intravascular pDC.

Movie S6. In vitro multi-photon microscopy of co-culture of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and splenic GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells, indicating attraction of pDCs to endothelial cells and their interaction with endothelial cells in formed endothelial cell tubes. Arrow indicates interaction of pDCs with human umbilical vein endothelial cells at a tube branching point.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to Mr. Allen Parmelee and Stephen Kwok for their technical assistance in sorting splenic cells. This study was supported by NIH R01-EY022695 (PH), NIH R01- EY026963 (PH), Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (PH), Massachusetts Lions Research Fund, Inc. (PH), Research to Prevent Blindness Challenge Grant, and Tufts Institutional Support.

Financial Support: NIH R01-EY022695 (PH), NIH R01-EY026963 (PH), Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (PH), Massachusetts Lions Research Fund, Inc. (PH), Research to Prevent Blindness Challenge Grant, and Tufts Institutional Support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lennert K & Remmele W [Karyometric research on lymph node cells in man. I. Germinoblasts, lymphoblasts & lymphocytes]. Acta haematologica 19, 99–113 (1958). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller-Hermelink HK, Stein H, Steinmann G & Lennert K Malignant lymphoma of plasmacytoid T-cells. Morphologic and immunologic studies characterizing a special type of T-cell. The American journal of surgical pathology 7, 849–862 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vollenweider R & Lennert K Plasmacytoid T-cell clusters in non-specific lymphadenitis. Virchows Archiv. B, Cell pathology including molecular pathology 44, 1–14 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feller AC, Lennert K, Stein H, Bruhn HD & Wuthe HH Immunohistology and aetiology of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis. Report of three instructive cases. Histopathology 7, 825–839 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasthofer EF, Prchal JT, Grizzle WE & Grossi CE Plasmacytoid T-cell lymphoma associated with chronic myeloproliferative disorder. The American journal of surgical pathology 9, 380–387 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris NL & Bhan AK “Plasmacytoid T cells” in Castleman’s disease. Immunohistologic phenotype. The American journal of surgical pathology 11, 109–113 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lennert K, Kaiserling E & Muller-Hermelink HK Letter: T-associated plasma-cells. Lancet (London, England) 1, 1031–1032 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Facchetti F et al. Plasmacytoid T cells. Immunohistochemical evidence for their monocyte/macrophage origin. The American journal of pathology 133, 15–21 (1988). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grouard G et al. The enigmatic plasmacytoid T cells develop into dendritic cells with interleukin (IL)-3 and CD40-ligand. The Journal of experimental medicine 185, 1101–1111 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abb J, Abb H & Deinhardt F Phenotype of human alpha-interferon producing leucocytes identified by monoclonal antibodies. Clinical and experimental immunology 52, 179–184 (1983). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perussia B, Fanning V & Trinchieri G A leukocyte subset bearing HLA-DR antigens is responsible for in vitro alpha interferon production in response to viruses. Natural immunity and cell growth regulation 4, 120–137 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svensson H, Johannisson A, Nikkila T, Alm GV & Cederblad B The cell surface phenotype of human natural interferon-alpha producing cells as determined by flow cytometry. Scandinavian journal of immunology 44, 164–172 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P Human natural interferon-alpha producing cells. Pharmacology & therapeutics 60, 39–62 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegal FP et al. The nature of the principal type 1 interferon-producing cells in human blood. Science (New York, N.Y.) 284, 1835–1837 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadowaki N, Antonenko S, Lau JY & Liu YJ Natural interferon alpha/beta-producing cells link innate and adaptive immunity. The Journal of experimental medicine 192, 219–226 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella M et al. Plasmacytoid monocytes migrate to inflamed lymph nodes and produce large amounts of type I interferon. Nature medicine 5, 919–923 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Glehn F, Santos LM & Balashov KE Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and immunotherapy in multiple sclerosis. Immunotherapy 4, 1053–1061 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang F, Du Q & Liu YJ Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in antiviral immunity and autoimmunity. Science China. Life sciences 53, 172–182 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shigematsu H et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells activate lymphoid-specific genetic programs irrespective of their cellular origin. Immunity 21, 43–53 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadowaki N et al. Subsets of human dendritic cell precursors express different toll-like receptors and respond to different microbial antigens. The Journal of experimental medicine 194, 863–869 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarrossay D, Napolitani G, Colonna M, Sallusto F & Lanzavecchia A Specialization and complementarity in microbial molecule recognition by human myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. European journal of immunology 31, 3388–3393 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaminsky LW et al. Redundant Function of Plasmacytoid and Conventional Dendritic Cells Is Required To Survive a Natural Virus Infection. Journal of virology 89, 9974–9985 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Negrotto S et al. Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Elicited Different Responses after Infection with Pathogenic and Nonpathogenic Junin Virus Strains. Journal of virology 89, 74097413 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang R et al. Upregulation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in glioma. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine 35, 9661–9666 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castelli C, Triebel F, Rivoltini L & Camisaschi C Lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3, CD223) in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs): a molecular target for the restoration of active antitumor immunity. Oncoimmunology 3, e967146 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sage AP et al. MHC Class II-restricted antigen presentation by plasmacytoid dendritic cells drives proatherogenic T cell immunity. Circulation 130, 1363–1373 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lund JM, Linehan MM, Iijima N & Iwasaki A Cutting Edge: Plasmacytoid dendritic cells 14 provide innate immune protection against mucosal viral infection in situ. J Immunol 177, 7510–7514 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persson CM & Chambers BJ Plasmacytoid dendritic cell-induced migration and activation of NK cells in vivo. European journal of immunology 40, 2155–2164 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel K, Thomann S, Vogel B, Schuster P & Schmidt B Both plasmacytoid dendritic cells and monocytes stimulate natural killer cells early during human herpes simplex virus type 1 22 infections. Immunology 143, 588–600 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fonteneau JF et al. Activation of influenza virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells: a new role for plasmacytoid dendritic cells in adaptive immunity. Blood 101, 3520–3526 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deal EM, Lahl K, Narvaez CF, Butcher EC & Greenberg HB Plasmacytoid dendritic cells promote rotavirus-induced human and murine B cell responses. J Clin Invest 123, 2464–2474 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw J, Wang YH, Ito T, Arima K & Liu YJ Plasmacytoid dendritic cells regulate B-cell growth and differentiation via CD70. Blood 115, 3051–3057 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munn DH, Sharma MD & Mellor AL Ligation of B7–1/B7–2 by human CD4+ T cells triggers indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity in dendritic cells. J Immunol 172, 4100–4110 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manlapat AK, Kahler DJ, Chandler PR, Munn DH & Mellor AL Cell-autonomous control of interferon type I expression by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in regulatory CD19+ dendritic cells. European journal of immunology 37, 1064–1071 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li XL et al. Mechanism and localization of CD8 regulatory T cells in a heart transplant model of tolerance. J Immunol 185, 823–833 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin-Gayo E, Sierra-Filardi E, Corbi AL & Toribio ML Plasmacytoid dendritic cells resident in human thymus drive natural Treg cell development. Blood 115, 5366–5375 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moseman EA et al. Human plasmacytoid dendritic cells activated by CpG oligodeoxynucleotides induce the generation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol 173, 4433–4442 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ito T et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells prime IL-10-producing T regulatory cells by inducible costimulator ligand. The Journal of experimental medicine 204, 105–115 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abe M, Wang Z, de Creus A & Thomson AW Plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors induce allogeneic T-cell hyporesponsiveness and prolong heart graft survival. Am J Transplant 5, 1808–1819 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ & Sharpe AH PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 26, 677–704 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dubois B et al. Sequential role of plasmacytoid dendritic cells and regulatory T cells in oral tolerance. Gastroenterology 137, 1019–1028 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uto T et al. Critical role of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in induction of oral tolerance. J Allergy Clin Immunol 141, 2156–2167.e2159 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Howell DM, Feldman SB, Kloser P & Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P Decreased frequency of functional natural interferon-producing cells in peripheral blood of patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 71, 223–230 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cederblad B & Alm GV Infrequent but efficient interferon-alpha-producing human mononuclear leukocytes induced by herpes simplex virus in vitro studied by immuno-plaque and limiting dilution assays. J Interferon Res 10, 65–73 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olweus J et al. Dendritic cell ontogeny: a human dendritic cell lineage of myeloid origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94, 12551–12556 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Segura E et al. Characterization of resident and migratory dendritic cells in human lymph nodes. The Journal of experimental medicine 209, 653–660 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kingham TP et al. Murine liver plasmacytoid dendritic cells become potent immunostimulatory cells after Flt-3 ligand expansion. Hepatology 45, 445–454 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi K et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense hepatitis C virus-infected cells, produce interferon, and inhibit infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 7431–7436 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gilliet M et al. The development of murine plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors is differentially regulated by FLT3-ligand and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. The Journal of experimental medicine 195, 953–958 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bilsborough J, George TC, Norment A & Viney JL Mucosal CD8alpha+ DC, with a plasmacytoid phenotype, induce differentiation and support function of T cells with regulatory 14 properties. Immunology 108, 481–492 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jameson B et al. Expression of DC-SIGN by dendritic cells of intestinal and genital mucosae in humans and rhesus macaques. Journal of virology 76, 1866–1875 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Egan RM et al. In vivo behavior of peptide-specific T cells during mucosal tolerance induction: antigen introduced through the mucosa of the conjunctiva elicits prolonged antigen-specific T cell priming followed by anergy. J Immunol 164, 4543–4550 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seo KY et al. Eye mucosa: an efficient vaccine delivery route for inducing protective immunity. J Immunol 185, 3610–3619 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seyed-Razavi Y et al. Kinetics of corneal leukocytes by intravital multiphoton microscopy. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 33, 2199–2211 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iparraguirre A et al. Two distinct activation states of plasmacytoid dendritic cells induced by influenza virus and CpG 1826 oligonucleotide. J Leukoc Biol 83, 610–620 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corcoran L et al. The lymphoid past of mouse plasmacytoid cells and thymic dendritic cells. J Immunol 170, 4926–4932 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.D’Amico A & Wu L The early progenitors of mouse dendritic cells and plasmacytoid predendritic cells are within the bone marrow hemopoietic precursors expressing Flt3. The Journal of experimental medicine 198, 293–303 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang YH & Liu YJ Mysterious origin of plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Immunity 21, 1–2 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P Natural interferon-alpha producing cells: the plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Biotechniques Suppl, 16–20, 22, 24–19 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nakano H, Yanagita M & Gunn MD CD11c(+)B220(+)Gr-1(+) cells in mouse lymph nodes and spleen display characteristics of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. The Journal of experimental medicine 194, 1171–1178 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Asselin-Paturel C et al. Mouse type I IFN-producing cells are immature APCs with plasmacytoid morphology. Nat Immunol 2, 1144–1150 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bjorck P Isolation and characterization of plasmacytoid dendritic cells from Flt3 ligand and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-treated mice. Blood 98, 3520–3526 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hubert FX, Voisine C, Louvet C, Heslan M & Josien R Rat plasmacytoid dendritic cells are an abundant subset of MHC class II+ CD4+CD11b-OX62- and type I IFN-producing cells that 19 exhibit selective expression of Toll-like receptors 7 and 9 and strong responsiveness to CpG. J 20 Immunol 172, 7485–7494 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Domeika K et al. Characteristics of oligodeoxyribonucleotides that induce interferon (IFN)-alpha in the pig and the phenotype of the IFN-alpha producing cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 24 101, 87–102 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guzylack-Piriou L, Balmelli C, McCullough KC & Summerfield A Type-A CpG oligonucleotides activate exclusively porcine natural interferon-producing cells to secrete interferon-alpha, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-12. Immunology 112, 28–37 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pascale F et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells migrate in afferent skin lymph. J Immunol 180, 5963–5972 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coates PT et al. Dendritic cell subsets in blood and lymphoid tissue of rhesus monkeys and 35 their mobilization with Flt3 ligand. Blood 102, 2513–2521 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vinay DS, Lee SJ, Kim CH, Oh HS & Kwon BS Exposure of a distinct PDCA-1+ (CD317) B cell population to agonistic anti-4–1BB (CD137) inhibits T and B cell responses both in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 7, e50272 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vinay DS, Kim CH, Chang KH & Kwon BS PDCA expression by B lymphocytes reveals important functional attributes. J Immunol 184, 807–815 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bao Y, Han Y, Chen Z, Xu S & Cao X IFN-alpha-producing PDCA-1+ Siglec-H- B cells mediate innate immune defense by activating NK cells. European journal of immunology 41, 657–668 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bierly AL, Shufesky WJ, Sukhumavasi W, Morelli AE & Denkers EY Dendritic cells 9 expressing plasmacytoid marker PDCA-1 are Trojan horses during Toxoplasma gondii infection. J 10 Immunol 181, 8485–8491 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blasius AL et al. Bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2 is a specific marker of type I IFN-producing cells in the naive mouse, but a promiscuous cell surface antigen following IFN stimulation. J Immunol 177, 3260–3265 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang J et al. Characterization of Siglec-H as a novel endocytic receptor expressed on murine plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Blood 107, 3600–3608 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kopatz J et al. Siglec-h on activated microglia for recognition and engulfment of glioma cells. Glia 61, 1122–1133 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gautier EL et al. Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nat Immunol 13, 1118–1128 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Villadangos JA & Schnorrer P Intrinsic and cooperative antigen-presenting functions of dendritic-cell subsets in vivo. Nat Rev Immunol 7, 543–555 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Omatsu Y et al. Development of murine plasmacytoid dendritic cells defined by increased expression of an inhibitory NK receptor, Ly49Q. J Immunol 174, 6657–6662 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brawand P et al. Murine plasmacytoid pre-dendritic cells generated from Flt3 ligand-supplemented bone marrow cultures are immature APCs. J Immunol 169, 6711–6719 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Toyama-Sorimachi N et al. Inhibitory NK receptor Ly49Q is expressed on subsets of dendritic cells in a cellular maturation- and cytokine stimulation-dependent manner. J Immunol 174, 4621–4629 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zuniga EI, McGavern DB, Pruneda-Paz JL, Teng C & Oldstone MB Bone marrow plasmacytoid dendritic cells can differentiate into myeloid dendritic cells upon virus infection. Nat Immunol 5, 1227–1234 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wilson NS et al. Normal proportion and expression of maturation markers in migratory dendritic cells in the absence of germs or Toll-like receptor signaling. Immunol Cell Biol 86, 200–205 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O’Keeffe M et al. Mouse plasmacytoid cells: long-lived cells, heterogeneous in surface phenotype and function, that differentiate into CD8(+) dendritic cells only after microbial stimulus. The Journal of experimental medicine 196, 1307–1319 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Villadangos JA & Young L Antigen-presentation properties of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunity 29, 352–361 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Soloff AC, Weirback HK, Ross TM & Barratt-Boyes SM Plasmacytoid dendritic cell depletion leads to an enhanced mononuclear phagocyte response in lungs of mice with lethal influenza virus infection. Comparative immunology, microbiology and infectious diseases 35, 309–317 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Penna G, Sozzani S & Adorini L Cutting edge: selective usage of chemokine receptors by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol 167, 1862–1866 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Penna G, Vulcano M, Sozzani S & Adorini L Differential migration behavior and chemokine production by myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Human immunology 63, 1164–1171 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Krug A et al. IFN-producing cells respond to CXCR3 ligands in the presence of CXCL12 and secrete inflammatory chemokines upon activation. J Immunol 169, 6079–6083 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vanbervliet B et al. The inducible CXCR3 ligands control plasmacytoid dendritic cell responsiveness to the constitutive chemokine stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1)/CXCL12. The Journal of experimental medicine 198, 823–830 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Umemoto E et al. Constitutive plasmacytoid dendritic cell migration to the splenic white pulp is cooperatively regulated by CCR7- and CXCR4-mediated signaling. J Immunol 189, 191–199 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Segura E, Wong J & Villadangos JA Cutting edge: B220+CCR9- dendritic cells are not plasmacytoid dendritic cells but are precursors of conventional dendritic cells. J Immunol 183, 1514–1517 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cisse B et al. Transcription factor E2–2 is an essential and specific regulator of plasmacytoid dendritic cell development. Cell 135, 37–48 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kohara H et al. Development of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in bone marrow stromal cell niches requires CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling. Blood 110, 4153–4160 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seth S et al. CCR7 essentially contributes to the homing of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to 12 lymph nodes under steady-state as well as inflammatory conditions. J Immunol 186, 3364–3372 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hillyer P, Mordelet E, Flynn G & Male D Chemokines, chemokine receptors and adhesion molecules on different human endothelia: discriminating the tissue-specific functions that affect leucocyte migration. Clinical and experimental immunology 134, 431–441 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Salvucci O, Basik M, Yao L, Bianchi R & Tosato G Evidence for the involvement of SDF-1 and CXCR4 in the disruption of endothelial cell-branching morphogenesis and angiogenesis by TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma. J Leukoc Biol 76, 217–226 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pablos JL et al. Stromal-cell derived factor is expressed by dendritic cells and endothelium in human skin. The American journal of pathology 155, 1577–1586 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cheng SS, Lukacs NW & Kunkel SL Eotaxin/CCL11 suppresses IL-8/CXCL8 secretion from human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol 168, 2887–2894 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shields PL et al. Chemokine and chemokine receptor interactions provide a mechanism for selective T cell recruitment to specific liver compartments within hepatitis C-infected liver. J 31 Immunol 163, 6236–6243 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tal O et al. DC mobilization from the skin requires docking to immobilized CCL21 on lymphatic endothelium and intralymphatic crawling. The Journal of experimental medicine 208, 2141–2153 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Russo E et al. Intralymphatic CCL21 Promotes Tissue Egress of Dendritic Cells through Afferent Lymphatic Vessels. Cell reports 14, 1723–1734 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Auffray C et al. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science (New York, N.Y.) 317, 666–670 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Geissmann F, Jung S & Littman DR Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity 19, 71–82 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Carlin LM et al. Nr4a1-dependent Ly6C(low) monocytes monitor endothelial cells and orchestrate their disposal. Cell 153, 362–375 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Peng Y, Latchman Y & Elkon KB Ly6C(low) monocytes differentiate into dendritic cells and cross-tolerize T cells through PDL-1. J Immunol 182, 2777–2785 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nitschke M et al. Differential requirement for ROCK in dendritic cell migration within lymphatic capillaries in steady-state and inflammation. Blood 120, 2249–2258 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Itaya H et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human monocyte/macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. Thrombosis and haemostasis 85, 171–176 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Funayama H et al. Human monocyte-endothelial cell interaction induces platelet-derived growth factor expression. Cardiovascular research 37, 216–224 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Koch AE et al. Interleukin-8 as a macrophage-derived mediator of angiogenesis. Science (New 24 York, N.Y.) 258, 1798–1801 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schubert SY, Benarroch A, Ostvang J & Edelman ER Regulation of endothelial cell proliferation by primary monocytes. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 28, 97–104 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Corliss BA, Azimi MS, Munson JM, Peirce SM & Murfee WL Macrophages: An Inflammatory Link Between Angiogenesis and Lymphangiogenesis. Microcirculation (New York, N.Y. : 1994) 23, 95–121 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hartmann E et al. Analysis of plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cells in nasal epithelium. Clin Vaccine Immunol 13, 1278–1286 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhan Y et al. Bcl-2 antagonists kill plasmacytoid dendritic cells from lupus-prone mice and dampen interferon-alpha production. Arthritis Rheumatol 67, 797–808 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sisirak V et al. Genetic evidence for the role of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of experimental medicine 211, 1969–1976 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lood C et al. Protein synthesis of the pro-inflammatory S100A8/A9 complex in plasmacytoid dendritic cells and cell surface S100A8/A9 on leukocyte subpopulations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 13, R60 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Clement M et al. CD4+CXCR3+ T cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells drive accelerated atherosclerosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Skrzeczynska-Moncznik J et al. Secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor-competent DNA deposits are potent stimulators of plasmacytoid dendritic cells: implication for psoriasis. J Immunol 189, 1611–1617 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gschwandtner M, Mommert S, Kother B, Werfel T & Gutzmer R The histamine H4 receptor is highly expressed on plasmacytoid dendritic cells in psoriasis and histamine regulates their cytokine production and migration. J Invest Dermatol 131, 1668–1676 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chen J et al. Expression of plasmacytoid dendritic cells, IRF-7, IFN-alpha mRNA in the lesions of psoriasis vulgaris. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 26, 747–749 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Aung LL, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Dhib-Jalbut S & Balashov K Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in multiple sclerosis: chemokine and chemokine receptor modulation by interferon-beta. J Neuroimmunol 226, 158–164 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Longhini AL et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are increased in cerebrospinal fluid of untreated patients during multiple sclerosis relapse. J Neuroinflammation 8, 2 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Schwab N, Zozulya AL, Kieseier BC, Toyka KV & Wiendl H An imbalance of two functionally and phenotypically different subsets of plasmacytoid dendritic cells characterizes the dysfunctional immune regulation in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 184, 5368–5374 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wildenberg ME, van Helden-Meeuwsen CG, van de Merwe JP, Drexhage HA & Versnel MA Systemic increase in type I interferon activity in Sjogren’s syndrome: a putative role for plasmacytoid dendritic cells. European journal of immunology 38, 2024–2033 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gottenberg JE et al. Activation of IFN pathways and plasmacytoid dendritic cell recruitment in target organs of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 2770–2775 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Stern ME, Schaumburg CS & Pflugfelder SC Dry eye as a mucosal autoimmune disease. Int Rev Immunol 32, 19–41 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Le A, Saverin M & Hand AR Distribution of dendritic cells in normal human salivary glands. cta Histochem Cytochem 44, 165–173 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Goubier A et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells mediate oral tolerance. Immunity 29, 464–475 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Palomares O et al. Induction and maintenance of allergen-specific FOXP3+ Treg cells in human tonsils as potential first-line organs of oral tolerance. J Allergy Clin Immunol 129, 510–520, 520 e511–519 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.de Heer HJ et al. Essential role of lung plasmacytoid dendritic cells in preventing asthmatic reactions to harmless inhaled antigen. The Journal of experimental medicine 200, 89–98 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

10–14 days following subcutaneous administration of FTL3L-secreting B16 melanoma cells, spleen of DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mice were harvested. After retrieving splenic single cells and lysis of RBCs, GFP+ pDCs were sorted. Representative flow cytometry dot plots representing gating out debris and dead cells (a), doublets (b), and sorting GFP+ pDCs. PE channel was used to avoid gating potential auto-fluorescent cells.

(a, b) Schematic illustration of the setup in top (a) and side (b) views. Mouse eye was placed between the coverslip and the pipet tip, exposing the limbus and bulbar conjunctiva. The room between the coverslip and the pipet tip was filled with GenTeal. Tubing containing circulating water was passed through the aforementioned room to maintain ocular surface temperature. Vacuum grease was applied on top of the coverslip to provide a top-opened room for immersion of objective lens. Actual pipet tip containing the water tube with a coverslip placed on top (c).

Quantification of GFP-tagged pDCs in the superior and inferior limbal area and bulbar conjunctiva of DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− transgenic mice indicates comparable density of pDCs in the superior and inferior limbus or bulbar conjunctiva (n=4).

Representative flow cytometric dot plot showing gating out debris (a), gating on live cells (b), and single cells (c). Next, CD45+ (d), Ly-6C+ (e), and CD11bneg cells were selected (f). Upper panel represents isotype staining unless otherwise specified and the lower panel illustrates corresponding staining with designated antibodies.

Movie S1. Reconstructed multi-photon micrograph of GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the naïve conjunctiva of a transgenic DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mouse, indicating pDCs are located in the substantia propria of bulbar conjunctiva during steady state.

Movie S2. Reconstructed multi-photon micrograph of GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the naïve limbus of a transgenic DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mouse, indicating pDCs are located in the substantia propria of limbal tissue during steady state.

Movie S3. Intra-vital multi-photon video of GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in naïve limbus of transgenic DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mouse injected with Qdot, shows pDCs residing in close proximity of vascular lumen as well as pDCs patrolling intravascular space.

Movie S4. Intra-vital multi-photon video of GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in naïve limbus of a transgenic DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mouse indicating characteristic kinetics of an intravascular pDC resembling a loop.

Movie S5. Intra-vital multi-photon video of GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in naïve limbus of a transgenic DPE-GFP×RAG1−/− mouse representing mixed crawling and loop migratory kinetics of an intravascular pDC.

Movie S6. In vitro multi-photon microscopy of co-culture of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and splenic GFP+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells, indicating attraction of pDCs to endothelial cells and their interaction with endothelial cells in formed endothelial cell tubes. Arrow indicates interaction of pDCs with human umbilical vein endothelial cells at a tube branching point.