Abstract

Cavitation events generated during histotripsy therapy generate large acoustic cavitation emission (ACE) signals which can be detected through the skull. This study investigates the feasibility of using these ACE signals, acquired using the elements of a 500kHz, 256-element hemispherical histotripsy transducer as receivers, to localize and map cavitation activity in real-time through the human skullcap during transcranial histotripsy therapy. The locations of the generated cavitation events predicted using the ACE feedback signals in this study were found to be accurate to within <1.5mm of the centers-of-masses detected by optical imaging, and were found to lie to within the measured volumes of the generated cavitation events in ≳ 80% of cases. Localization results were observed to be biased in the prefocal direction of the histotripsy array and towards its transverse origin but were only weakly affected by focal steering location. The choice of skullcap and treatment pulse repetition frequency (PRF) were both observed to affect the accuracy of the localization results in the low PRF regime (1Hz to 10Hz), but localization accuracy was seen to stabilize at higher PRFs (≥10Hz). Tests of the localization algorithm in vitro, for treatment delivered to a bovine brain sample mounted within the skullcap, revealed good agreement between the ACE feedback-generated treatment map and the morphological characteristics of the treated volume of the brain sample. Localization during experiments was achieved in real-time for pulses delivered at rates up to 70Hz, but benchmark tests indicate that the localization algorithm is scalable, indicating that higher rates are possible with more powerful hardware. The results of this study demonstrate the feasibility of using ACE feedback signals to localize and map transcranially-generated cavitation events during histotripsy. Such capability has the potential to greatly simplify transcranial histotripsy treatments, as it may provide a non-MRI based method for monitoring and localizing transcranial histotripsy treatments in real-time.

Keywords: Transcranial therapy, histotripsy, non-invasive therapeutic ultrasound, cavitation, aberration correction

I. Introduction

High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) therapies have been investigated extensively for use in brain applications [1]–[12], where noninvasive surgical techniques are highly favored owing to the reduced risk of complications associated with invasive surgeries. For transcranial HIFU treatments, real-time MR-guidance is used to perform aberration correction, steer the focal target of the therapy, and monitor for unsafe tissue heating beyond the focal volume [13]–[16]. MR-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) thermal therapies have received a great deal of interest for use in neurosurgical applications [13], [17]–[20] and have been approved by the FDA for treating essential tremor [8] and clinical trials are ongoing to use MRgFUS to treat Parkinson’s and glioblastomas. However, the scope and size of targets accessible to HIFU thermal therapies in the brain are generally limited to small (≲1cm diameter), deep targets due to the dissipation and absorption of ultrasound energy by the skull and its associated heating, particularly when targeting large or superficial regions [21]–[29].

Histotripsy is a nonthermal ultrasound therapy that relies of the targeted generation of controlled cavitation activity to achieve its therapeutic effect. This is accomplished using specialized, microsecond-duration, high-amplitude ultrasound pulses, delivered using an extracorporeal ultrasound transducer, to locally generate inertial cavitation [30]. The rapid expansion and collapse of the generated cavitation bubble clouds then act to mechanically fractionate and destroy the targeted tissues [31], [32]. Histotripsy has been demonstrated to generate precisely defined lesions with sharp boundaries between treated and untreated regions [31]–[33] in a wide variety of tissues [34]–[37].

Histotripsy has recently been investigated for transcranial applications where it was demonstrated to generate targeted lesions through the skullcap over a wide range of locations, with [38] or without aberration correction [39], and as close to the skull surface as 5mm [40]. It has also been shown not to generate significant heating in the skull bone (≤4°C) even when continuously targeting (up to 1h) regions as shallow as 5mm from the skullcap owing to the low duty cycle used in histotripsy (< 0.2%) [12]. Rapid transcranial ablation of large volume targets using histotripsy in an in vitro intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) model has also been demonstrated where it has been shown that clot volumes of up to 40mL can be treated in as little as 20min [12]. In a recent in vivo study in a porcine model, it was shown that histotripsy ablation could be safely generated in the brain without causing excess hemorrhage or damage to treatment-adjacent brain tissues, and without leading to other near-term (≤72h) complications such as inflammation or significant edema [41].

As histotripsy relies on cavitation instead of heating, the MR thermometry techniques used to monitor MRgFUS in real-time cannot be directly used to monitor histotripsy. MRI is also not generally fast enough to allow real-time monitoring of histotripsy treatments, particularly those targeting large volumes, where pulses are often delivered to generate cavitation events at PRFs on the order of 200Hz or more. Numerous approaches for detecting and monitoring cavitation activity transcranially using acoustic methods have been successfully investigated [42]–[48]. Of particular interest to this study are the approaches of passive cavitation detection (PCD) [42], [44] and passive acoustic mapping [45], [46], [48], which rely on measuring acoustic signals associated with the cavitation events using passive arrays of ultrasound receivers to detect and localize them.

Indeed, methods based on these approaches, which rely on back-propagating acquired cavitation emission signals into the field to generate volumetric maps of the signal amplitude near the source emitter, have successfully been used to transcranially monitor acoustically excited microbubbles with potential for applications in blood-brain barrier opening procedures [49], [50], as well as to map inertial cavitation events generated through the skull [51]. In order to generate accurate maps of cavitation events using these methods, however, predetermined temporal offsets generally need to be applied to the signals to account for sound speed differences between the skull and surrounding media, as well as to correct for skull-induced aberrations. Extensive signal processing may also be necessary in order to isolate the cavitation emission signals from the background which can significantly increase computation times, particularly when large numbers of signals need to be acquired, and can limit the ability to monitor cavitation events in real-time.

Recent advances in histotripsy transducer design have enabled the transmitting elements of the histotripsy array to be operated in a transmit-receive mode, thus allowing them to be used to acquire the acoustic signals generated by the cavitation events. Recent studies using a transmit-receive capable histotripsy array have indicated that the signals measured using its receive-capable elements can be used to detect the degree of tissue fractionation achieved during histotripsy treatment [52], as well as to perform aberration correction in soft-tissues to recover phase-aberration-induced losses in focal pressure amplitude [53].

The acoustic signals received by the transducer elements have been demonstrated to be acoustic cavitation emissions (ACE) in the form of shockwaves generated during the nucleation process, rather than backscatter from the nascent bubble cloud [53]. Whereas many PCD approaches rely on the modulating affects of bubbles on the ultrasound pulses propagating through them for detection, owing to the short duration nature of histotripsy pulses (1–2 acoustic cycles), by the time the bubbles have grown to be large enough to affect and scatter incoming sound, the histotripsy pulses have long- since exited the focal region. The nature of the ACE signals is particularly advantageous for the purposes of localization and mapping histotripsy treatment regions as the ACE signals originate at the localization target and so are only affected by the aberrator on their way back to the receivers.

In the present study we demonstrate the feasibility and accuracy of using the ACE signals from transcranially-generated histotripsy bubbles to localize and map them in 3D through the skull in real-time. An existing 500kHz, 256-element transcranial histotripsy transducer array was modified such that 160 of the array elements could be operated in a transmit-receive mode to acquire the ACE signals. Localization and mapping algorithms based on back-propagating the acquired ACE signals into the field were then developed. Simple, computationally inexpensive background subtraction methods were employed to process the acquired signals. Although it is generally possible to determine the temporal offsets necessary to correct for skull-induced aberrations based on a priori CT or hydrophone measurements [54], [55], or via acoustic detection schemes during treatment [47], [49], the extent to which such aberrations impact localization accuracy during transcranial histotripsy treatments using the ACE signals has not been established. We were thus motivated to establish baseline estimates of the accuracy of ACE-based transcranial localization methods in the absence of external input data, and acknowledge the limitations of such an approach. The accuracy of the algorithms was assessed via comparison of the ACE feedback localization results with multi-camera optical imaging of the generated bubble clouds’ positions. Tests of the developed algorithms were also carried out to assess their performance in vitro, where they were used to map a histotripsy treatment delivered to an excised bovine brain sample mounted within a human skullcap. The in vitro performance of the methods was assessed via comparison of the generated treatment map and the results of a morphological inspection of the ablation zone generated in the brain sample.

II. Materials and Methods

A. Phased Array Transducer

Histotripsy pulses were delivered using a custom built [56], 256-element, 500kHz hemispherical phased array transducer with an aperture diameter of 30cm and a focal distance of 15cm (Fig. 1). The elements of the array were driven using custom-built high-voltage pulsers capable of delivering short duration (≤2 acoustic cycles), high amplitude ultrasound pulses. Control over the transducer elements was accomplished using a field-programmable gate array (FPGA) which allowed each element of the array to be fired independently to deliver the histotripsy pulses. Each element of the array was capable of generating peak rarefactional pressures at the transducer focus in the free field of up to 0.8MPa (measured with a high-sensitivity needle hydrophone – model HNR-0500, Onda Corp., Sunnyvale, CA), corresponding to peak rarefactional pressures of the fully populated array, by linear summation of the contributions from individual elements, in excess of 200MPa [30]. Note that, as cavitation exists 100% of the time above the intrinsic threshold for nucleation (27−30MPa [30]), pressures above this value cannot likely be generated in practice. Additionally, owing to the generation of destructive cavitation events on physical hydrophones, direct measurements of rarefactional pressures in excess of ∼20MPa are not possible. As such, all stated values of the pressure above ∼20MPa herein do not correspond to direct measurements but are instead estimates based on the linear summation of measured pressure outputs of the individual elements [30] and are accordingly denoted as . These pressures are intended only to serve as indicators of the available pressure headroom at the transducer focus and, by proxy, the likelihood of generating cavitation.

Fig. 1.

An image showing the histotripsy transducer used during experiments with a skullcap mounted within. The black dots on the array mark the receive-capable elements (receive-capable elements blocked by the skull not shown).

160 elements of the array were outfitted with modified circuitry to allow them to operate simultaneously as transmitters and receivers and thus be used to acquire the ACE signals. The receive circuitry was comprised of two basic components, a non-linear voltage compressor wired in parallel across the transducer elements and an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) to digitize the compressed signals. The non-linear voltage compressor was designed to preserve signal information over a dynamic range from ∼50mV – approximately 0.5–1% of the maximum signal amplitude generated across the transducer elements by ACE signals from transcranially-generated cavitation events – up to 300V – the maximum amplitude measured across the elements from histotripsy pulses reflected off the skull. The response of the compression circuit was approximately linear over the range from 0V to 7V and non-linear from 7V to 300V. Signals above 300V, e.g. the outgoing histotripsy pulses (up to 3kV), were clipped by a diode protection circuit. Following compression, signals were digitized using 8-bit, 20MHz ADCs and transferred to the user’s computer for processing.

The positions of the receive-capable elements in the array were such that they were more highly concentrated near the equatorial plane of the transducer. This configuration was chosen based on measurements of transcranially generated ACE signals which, based on the typical alignment of the skull in the array, were weakest in this direction. The denser packing of receive elements in this region was chosen to ensure signals sufficient to accurately localize bubbles in the transverse direction of the array could be acquired.

B. ACE Signal Acquisition and Data Management

The digitized ACE signals were captured using System-ona-Chip (SoC) devices (DE0-Nano-SoC kit). Each SoC device was capable of capturing the input signals from 8 transducer elements concurrently, and 20 independently controlled SoC systems were used during experiments to capture data from all 160 receive-capable transducer elements simultaneously.

Communications between the SoC systems and the user’s computer were carried out over gigabit ethernet using custom software packages written in the C-programming language. To ensure the fidelity of the communications and data transfer over the network, all communications were carried out over ethernet sockets configured using TCP/IPv4 protocols. The maximum data transfer rate achievable over the implemented network was measured to be on the order of 800–850 megabits per second. Depending on the acquisition parameters, ACE signal acquisition was possible in real-time during experiments for pulses delivered at PRFs up to ∼400Hz.

C. Cavitation Localization and Mapping Algorithm

Cavitation localization and mapping were accomplished via brute force methods following two steps: 1) signal processing to separate the ACE signals from the skull reflection signals; and 2) generating a cavitation map by projecting the ACE signals acquired by each element of the array back into the field and summing their signal amplitudes. All computations were performed on a GPU (NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 Ti) via programs written in C using the NVIDIA CUDA C SDK.

1). Signal Processing

Prior to localization and mapping, the acquired voltage signals were decompressed and processed in three steps in order to separate the ACE signals from background components.

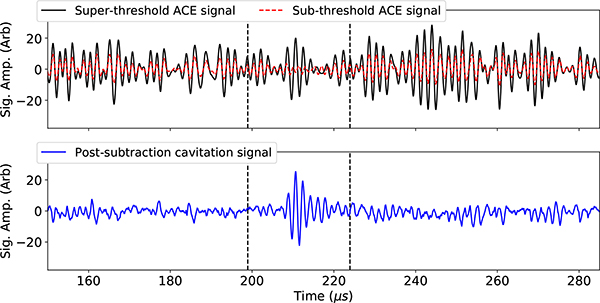

First, signals from low amplitude, sub-cavitation threshold histotripsy pulses were acquired. These signals were scaled up linearly and subtracted from the ACE-containing signals acquired after delivering high-amplitude histotripsy pulses in order to remove signals associated with reflections and reverberations from the skullcap from the acquired waveforms (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A plot of the super- and sub- cavitation threshold waveforms acquired using the receive-capable elements of the array, and the resultant ACE signal associated with the cavitation event after the subtraction process.

Second, the waveforms were smoothed using a moving window average using a rectangular window function. The width of the window was 0.25μs and was chosen to coincide with the time-of-flight across the voxels in the localization grid (Sec. II-C2).

Last, the absolute value of the resulting signals was taken.

2). Localization and Mapping

The first step of the localization computation was to define a grid of voxels, , in the field over which to generate the volumetric signal amplitude map for each pulse, where the center point of each voxel within the field was given as . The grid of voxels was defined as a 64 × 64 × 64-element cubic grid, measuring 21.33 mm per side. The voxel grid was centered about the steered-to focal location of the treatment, i.e. the expected location of the generated bubble, and a unique voxel grid was generated for each steering location.

The distances from each receiving element of the histotripsy array, with locations defined as , to the centers of the voxels were then calculated and used to determine the corresponding times-of-flight, tn,i,j,k, from the array elements to the voxel locations.

| (1) |

where cw is the sound speed of water, 1482m/s, and was taken to be constant everywhere in the first step of the calculation.

The processed signals acquired from each element of the array, Sn(t), were then summed together at each location within the voxel grid to generate a corresponding signal amplitude, ai,j,k(t), at each voxel (Eq. 2). The time, t, in Eq. 2 corresponds to the there-and-back time-of-flight from the respective array elements to the each voxel in the grid and is given by t = 2 · tn,i,j,k.

| (2) |

The effects of the skull in the beam path were accounted for based on the following two assumptions in order to allow Eq. 2 to be used to localize the cavitation events: 1) the sound speed of the skull would not be known a priori and could differ from water’s and 2) phase aberrations induced to the ACE signals propagating through the skull would not vary with position on, or trajectory through, the skull and thus could be ignored. In effect, these assumptions treat the skull as a uniform aberrator whose effects on the ACE signals, through a coupled metric of the skull’s mean thickness and sound speed, can be accounted for by iterating Eq. 2 in time.

The location of the bubble was determined by calculating the maximum signal amplitude at each location in the field, Ai,j,k, within a time-iteration window, t = t0±dt, then finding the center-of-mass of points in the field with amplitudes above a prescribed threshold. The following block of C pseudo-code shows the process by which this was accomplished:

| (3) |

where t0 corresponds to the expected arrival time of the ACE signals based on the steered-to focal location of the histotripsy pulses. The expected arrival time was taken to be equal to the expected arrival time in the free field case plus an empirically determined offset to account for the presence of the skull and center the iteration window about the ACE signals. The offset was determined by iterating in time over the window t = t0,f±10μs (where t0,f corresponds to the expected arrival time in the free field) and then finding the time at which ai,j,k(t) achieved its maximum amplitude for a bubble generated at the geometric origin of the array. This step only needed to be performed once per experiment. Time in the calculations of the signal amplitude field used for localization and mapping was iterated through over the range from t = (t0 − 5μs) → t = (t0 + 5μs) in steps of 0.25μs.

After the signal amplitude field was calculated, the location of the generated cavitation event, , was determined by calculating the amplitude-weighted, center-of-mass of the region of the auto-normalized signal amplitude field above −1dB according to the following equations:

| (4) |

where W is the weight function.

D. Transcranial Cavitation Localization Experiments

During experiments, cavitation events were generated through 3 excised human cadaver skullcap samples obtained through the University of Michigan Anatomical Donations Program. The specimens were cleaned and defleshed after extraction and were kept in a bath of degassed water for a minimum of one week prior to experiments. The physical dimensions of the skullcaps used are shown in Table I.

TABLE I.

Measurements of the skullcaps used during experiments

| Skull cap | Maj. Dimensions1 (mm) | Thickness1 (mm) | Sound Speed2 (mm/μs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long Axis | Short Axis | Depth | Min | Max | Mean | ||

| 1 | 161 | 139 | 58 | 2.1 | 8.5 | 5.1 | 2.06 ± 0.40 |

| 2 | 170 | 142 | 64 | 2.2 | 8.9 | 5.2 | 2.72 ± 0.43 |

| 3 | 183 | 143 | 64 | 2.6 | 11.1 | 6.5 | 2.34 ± 0.35 |

Measurements of the skullcaps’ dimensions were obtained from 3-D laser scans of their surfaces [skullcaps 1 & 3] (Ultra HD 2020 i, NextEngine, Santa Monica, CA, USA) or CT scans of their volumes [skullcap 2] (Discovery CT750 HD, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA)

Based on hydrophone (HGL200, Onda, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) measurements of the times-of-flight of acoustic pulses from the array to its geometric origin with and without the skullcap in the field

Two sets of localization experiments were carried out in order to acquire the data needed to develop the real-time transcranial cavitation localization and mapping algorithm, verify its accuracy and precision, and assess its performance in vitro. In the first set of experiments, skullcaps were submerged in water and histotripsy pulses were delivered through them to generate cavitation. Pulses were delivered to 4 separate target regions through each skullcap – 1) a central region, 2) near the apex of the parietal bone along the sagittal suture, 3) near the parietal bone approximately midway between the sagittal and squamosal sutures, and 4) near the frontal bone forward of the coronal suture. For the sake of brevity, when referring to the targeted regions they will hereafter be referred to as 1) central, 2) top, 3) side, and 4) front. In the top, side, and front target regions the geometric focus of the array was located approximately 1.5cm from the skull surface, in the central target region the geometric focus of the array was located approximately 4.5cm from the nearest skull surface.

Cavitation activity was monitored using multi-camera optical imaging to determine the 3D locations of the generated bubbles. The accuracy and precision of the ACE feedback localization results was assessed via comparison with the 3D positions of the cavitation events measured in images.

In the second experiment, a full histotripsy treatment was delivered in vitro to an excised bovine brain sample mounted within skullcap 3 to ablate a 2.6cm maximum diameter, volumetric target. Treatment was localized and monitored using the ACE feedback signals throughout. The efficacy of the ACE localization and mapping results in this experiment were assessed by comparison of the ACE-based map of the generated cavitation events with a morphological analysis of the ablation target in the brain sample following treatment.

In both sets of experiments phased array steering was used to generate cavitation events at a multitude of different locations within the skullcaps to assess the impacts of electronic focal steering location on the localization accuracy (not to be confused with the different target regions in the imaging experiments). All cavitation events during both sets of experiments were generated at least 6cm from the free surface of the water. Pulses were also delivered at varying PRFs in the imaging experiments to assess how treatment rate affected the accuracy and precision of the developed cavitation localization algorithm. In all instances in which ACE signals were acquired following a cavitation event, they were acquired using all 160 receive-capable elements of the array at once.

The relevant treatment parameters of the two experiments are summarized in Table II and additional information related to each experiment is provided below.

TABLE II.

Summary of the treatment parameters used in each experiment

| Experiment | Focal Pressure,1 [MPa] | Hydrophone Aberration Correction2 | Treatment PRFs [Hz] | Number of Focal Steering Locations | Maximum Steering Radius5 [mm] | Pulses Per Location | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Region | Skull 1 | Skull 2 | Skull 3 | ||||||

| Imaging | Central | 44.5 | 46.0 | 47.6 | yes3,4 | 1, 10, 50, 100 | 53 | 10.4 | 30 |

| Top | 30.1 | 35.3 | 36.6 | ||||||

| Side | 23.5 | 30.0 | 23.2 | ||||||

| Front | 21.5 | 28.8 | 25.3 | ||||||

| In Vitro Mapping | N/A | N/A | 37 | no4 | 200 | 1000 | 13 | 300 | |

Measured at the geometric origin. The electrical driving power of the transducer array was held constant across all experiments and at all steering locations. As such, the stated pressures only represent the pressure at the geometric origin and not that at each steering location.

Aberration correction consisted of measuring the time of arrival of the peak negative pressure from each array element individually through the skullcap using a needle hydrophone (Model HNR-0500, Onda Corp., Sunnyvale, CA) and applying a phase correction to the transducer firing times such that they would all align at the intended focus.

The aberration correction delay set was only measured at the geometric origin of the array and was uniformly applied as the aberration correction delay set at all other steering locations.

Aberration correction was only applied during the targeting phase for the express purpose of maximizing focal pressures to ensure that cavitation events, and thus the ACE signals needed to localize them, would be generated during the imaging experiments. It was otherwise unimportant to the described localization methods except insofar as the inability to perform targeting aberration correction during the in vitro experiment (Sec. II-D2) disallowed for a meaningful decoupling of the targeting error from the localization error during the analysis of the results (Sec. III-B).

The maximum steering radius was defined with respect to the geometric origin of the array.

1). Multi-Camera Imaging Localization Experiments

To detect the actual locations of the cavitation events, two orthogonally mounted cameras (Point Gray, Chameleon and Point Gray, Flea 3) were used to capture images of the bubble clouds generated after each histotripsy pulse (Fig. 3). The bubble clouds in these images were front-lit using an LED flash source mounted at the mid-point between the two cameras and projected into the transducer’s focal region. The bubble clouds captured in images were detected by brightness thresholding following the subtraction of reference images in which no cavitation events were present.

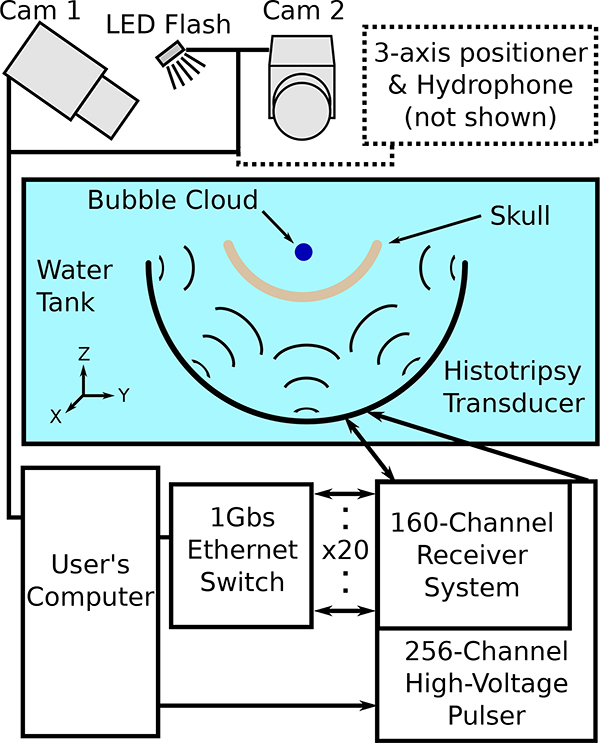

Fig. 3.

A schematic drawing of the transmit-receive capable array and the various systems connected to it as used in experiments.

Based on the locations of the detected bubble clouds in the images, and the known positions and orientations of the cameras, the 3D locations of the bubble clouds in the focal region were calculated by projecting lines along the imaging axes of the respective cameras, extending from each pixel of the bubble cloud captured in each of the two images, finding the points of intersection between the projected pixels, and then finding the center-of-mass of the calculated points.

The accuracy and precision of the localization algorithm was assessed based on the distance between the positions of the cavitation events predicted from the ACE-feedback signals and their centers-of-masses determined from images. Additional assessments of the localization algorithm’s performance were carried out based on information about the bubbles’ sizes available in the images. In particular, whether or not the localization results fell within the volumes encompassed by the generated bubbles, as opposed to just their proximity to the bubbles’ centers-of-mass, was assessed. This was accomplished by approximating the imaged cavitation events as single, ellipsoidally shaped bubbles whose radii Rx, Ry, and Rz were calculated based on the measured extents of the bubbles captured in images. The coordinates at the boundary of the ellipsoid, (xe, ye, ze), were defined as

| (5) |

where the values, (xc, yc, zc), correspond the mid-point of the bubble, and θ and ϕ are the polar and azimuthal angles, respectively, in the coordinate system centered about (xc, yc, zc) whose polar axis runs parallel to that of the histotripsy transducer’s (i.e. along the respective z-axes). The polar and azimuthal angles of the ACE feedback localization result, with respect to the mid-point of the bubble calculated from images, were then calculated and used to determine the radius of the ellipsoid boundary in the corresponding direction. Finally, whether or not the bubble was localized to within the volume encompassed by the generated bubble was determined based on whether the distance between the center point of the bubble and the localization result was larger or smaller than the calculated radius of the ellipsoid boundary in the corresponding direction.

2). In Vitro Localization Experiment

For the in vitro experiment, a whole bovine brain sample was obtained from a local abattoir. Prior to treatment, the brain sample was placed in a condom filled with a degassed, 1% (w./v.) agarose gel solution. The gel was then allowed to solidify around the brain sample in the condom for 1 hour at 4°C. Skullcap 3 was then submerged in its entirety in 2L of degassed, 1% agarose gel and the condom containing the brain sample was placed centrally within it. The solution was allowed to solidify for 4 hours at 4°C around the skullcap/brain sample, at which point the position of the brain sample within the skullcap was fixed.

The skullcap was then positioned in the transducer such that the geometric origin of the array was located centrally within the brain sample in the depth/axial and left/right directions. This corresponded to the geometric origin of the array being located approximately 3cm from the interior surface of the skullcap. Owing to the presence of the condom containing the brain sample, a hydrophone could not be inserted into the brain sample in order to perform aberration correction prior to delivering the histotripsy pulses. As such the front/back position of the skullcap in the transducer was set based on prior measurements of the pressure amplitude achievable through the skullcap based on its position in the array, and positioned at the location where the achievable focal pressure amplitude, without aberration correction, was maximal. This corresponded to a focal pressure amplitude, in the absence of the overlying brain and agarose gel samples, of . As a result of positioning the skullcap this way the center point of the generated lesion was located in a posterior region of the embedded brain sample.

Histotripsy pulses were then delivered to the embedded brain sample using the parameters shown in Table II. The steering pattern of the treatment was a 10×10×10 cubic grid of treatment points measuring 15mm per side, centered at the geometric origin of the array. Owing to hard limits imposed by the achievable data transfer and localization rates in the current system, as well as memory limitations of the computer controlling the array, ACE signals during treatment were only acquired for localization and mapping after every 10th pulse.

Following treatment, the skullcap-shaped block of agarose gel containing the embedded brain sample was removed whole from the skullcap. The entire sample was cut in half along a plane running through the center point of the generated lesion along the front/back direction of the sample such that the left and right hemispheres of the sample (with respect to the geometry of the skullcap) were separated. The ablated portion of the embedded brain sample was then removed via rinsing and suctioning out the emulsified brain tissue. Measurements of the voided region were then acquired for comparison with the map of cavitation activity generated from the ACE signals.

III. Results

A. Multi-Camera Imaging Localization Experiments

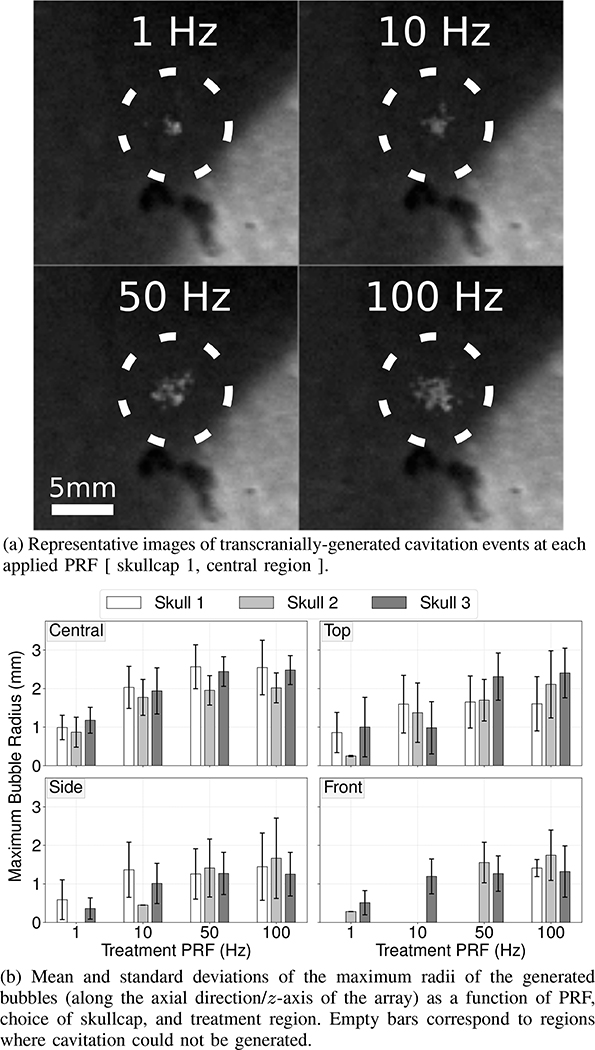

A representative series of images of bubble clouds generated through skullcap 1 by histotripsy pulses delivered at 1Hz, 10Hz, 50Hz and 100Hz are shown in Figure 4a. As may be appreciated from these images, the generated bubble clouds were observed to become increasingly larger and less compact as a function of increasing PRF. This trend was observed to be consistent for bubble clouds generated through all three skullcaps and in all treatment regions (Fig. 4b). As a function of target region, the average spatial dimensions of the generated bubbles were observed to follow expectations based on the estimated focal pressure amplitudes (Table II) and were seen to be largest in the central region where focal pressure amplitudes were largest and smaller in the top, side, and front target regions where focal pressures were lower.

Fig. 4.

Images of bubbles generated through the skullcap (Fig. 4a) and their sizes as a function of target region, choice of skullcap, and PRF (Fig. 4b)

Despite being able to generate cavitation events and identify ACE signals in the waveforms acquired for bubbles generated in all target regions, accurately localizing bubbles using the ACE signals was generally only possible for bubbles generated in the central region. As such, all results from the imaging experiments to follow come only from bubbles generated in the central target region. It should be noted, however, that the inability to accurately localize bubbles in the non-central regions is believed to be, at least in part, due to resolution limits associated with the non-linear voltage compressor and 8-bit ADCs used in the receive system, and not necessarily intrinsic to cavitation events generated in these regions in general. A discussion on this and a detailed description of the limitations experienced and how they affected the ability to localize bubbles in the non-central target regions is provided later.

In the central target region the ACE feedback localization results were observed to be in good general agreement with the positions of the bubble clouds captured in images and were accurate to within ≤1.67mm of their imaged centers-of-masses in all [skullcap, PRF] parameter groupings (Table III). The accuracy and precision of the localization results were observed to be highest at 1Hz, to decrease significantly between 1Hz and 10Hz, and then to generally stabilize or improve over the range from 10Hz to 100Hz. Within each PRF group, the ACE localization results were seen to be consistent across skullcaps to within ≤340μm of each other. Within each skullcap group, the ACE localization results were seen to be consistent to within ≤220μm of each other over the PRF range from 10Hz to 100Hz. The precision of the localization results was highest for pulses delivered at 1Hz, and lower at the higher PRFs but did not show any significant dependence on PRF over the range from 10Hz to 100Hz. Overall, the ACE-feedback localization results were seen to be accurate to within 1.43 ± 0.76mm of the imaged centers-of-masses of the generated bubbles. A summary of these results is shown in Table III.

TABLE III.

Summary of ACE-Feedback Localization Results [Central Target Region]

| Skullcap | Distance: ACE Localized Position to Imaged Center-of-Mass (mm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| @1 Hz | @10 Hz | @50 Hz | @100 Hz | All PRFs | |

| 1 | 0.96 ± 0.32 | 1.53 ± 0.71 | 1.50 ± 0.72 | 1.35 ± 0.62 | 1.38 ± 0.67 |

| 2 | 1.30 ± 0.79 | 1.59 ± 0.98 | 1.38 ± 0.76 | 1.48 ± 0.92 | 1.45 ± 0.87 |

| 3 | 0.98 ± 0.45 | 1.66 ± 0.65 | 1.67 ± 0.82 | 1.45 ± 0.69 | 1.44 ± 0.72 |

| All | 1.02 ± 0.50 | 1.60 ± 0.75 | 1.52 ± 0.78 | 1.43 ± 0.77 | 1.43 ± 0.76 |

The effect of focal steering location on the accuracy of the ACE-feedback localization results was seen to be influenced by both choice of skullcap and PRF. Generally speaking, however, the localization error was observed to be only weakly dependent on the focal steering location, increasing by ≲ 40μm per 1mm steering distance in all but two cases. Nearly uniform, steering-independent biases in the prefocal direction of the array were also observed which ranged, on average, from 0.4mm to 0.9mm depending on skullcap. Overall, the errors in the localization results produced biases towards the transverse origin of the array and in its prefocal direction. With respect to the L1-norm, the fractional contribution to the overall localization error by component was xerr ≈ 30%, yerr ≈ 20%, and zerr ≈ 50%, where xerr, yerr, and zerr correspond to errors in the anterior/posterior, lateral, and axial directions of the skullcaps, respectively.

The two cases where the localization error was observed to be more significantly dependent on the focal steering location were through skullcap 2 at 50Hz and 100Hz. In these two cases the axial component of the localization error was observed to increase significantly when steering towards the prefocal direction, resulting in a steering-dependent prefocal bias in the localization results of up to 280μm/mm. The axial component of the localization error was the only component affected in these cases; no such increase in error was observed when steering in the postfocal or transverse directions.

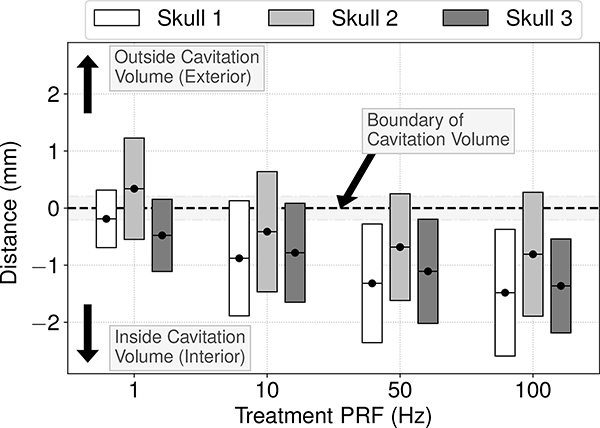

Accounting for the additional information about the bubbles’ sizes available in the images, on average the ACE feedback localization results were observed to be accurate to within the volumes encompassed by the generated bubbles, or to within ≤350μm of their imaged boundaries (Fig. 5). On a per pulse basis, bubbles were accurately localized to within their imaged volumes during 80% of pulses, and to within ≤1mm of their boundaries during 93% of pulses. The accuracy of the ACE-feedback localization results with respect to localizing to within the bubbles’ volumes was observed to improve with increasing PRF through all skullcaps.

Fig. 5.

Mean (black dots) and standard deviations (shaded bars) of the distance from the ACE localization results to the imaged boundaries of the generated cavitation events through each skullcap at each PRF. Negative values on the y-axis correspond to localization results lying within the volumes encompassed by the generated cavitation events. The horizontal gray bar centered about y =0 represents the spatial resolution error of the localization results.

B. In Vitro Localization Experiments

Images of the treated bovine brain sample and maps of the cavitation activity generated using the ACE signals are shown in Figures 6 & 7, respectively. Morphological inspection of the ablation zone in the brain sample showed it to be in reasonable agreement with the 15mm wide cubic treatment volume steered through, however, the ablation in the anterior, pre-focal regions of the targeted volume, particularly in the left hemisphere of the brain (not shown), appeared incomplete, which is to say that some partially attached brain tissue was observed to remain following rinsing and suctioning of the ablated tissue to void the cavity. Evidence to this effect may be seen in the anterior, pre-focal corner of the ablation zone in Fig. 6, which appears rounded off and more poorly defined than the others with respect to the cubic treatment pattern. The ablation zone’s dimensions were measured via calipers at approximately the midline of the evacuated volume along each of the respective axes. Acknowledging that the irregular shape of the ablated volume and presence of incompletely ablated brain tissues within the evacuated cavity, as well as the pooling of liquid/emulsified tissues (lateral direction only), likely impacted the measurements, to the best of our ability the ablation zone’s major dimensions in the anterior/posterior, prefocal/postfocal, and lateral directions were measured to be 15mm, 17mm, and 12mm, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Image of the ablated brain sample from the in vitro experiment.

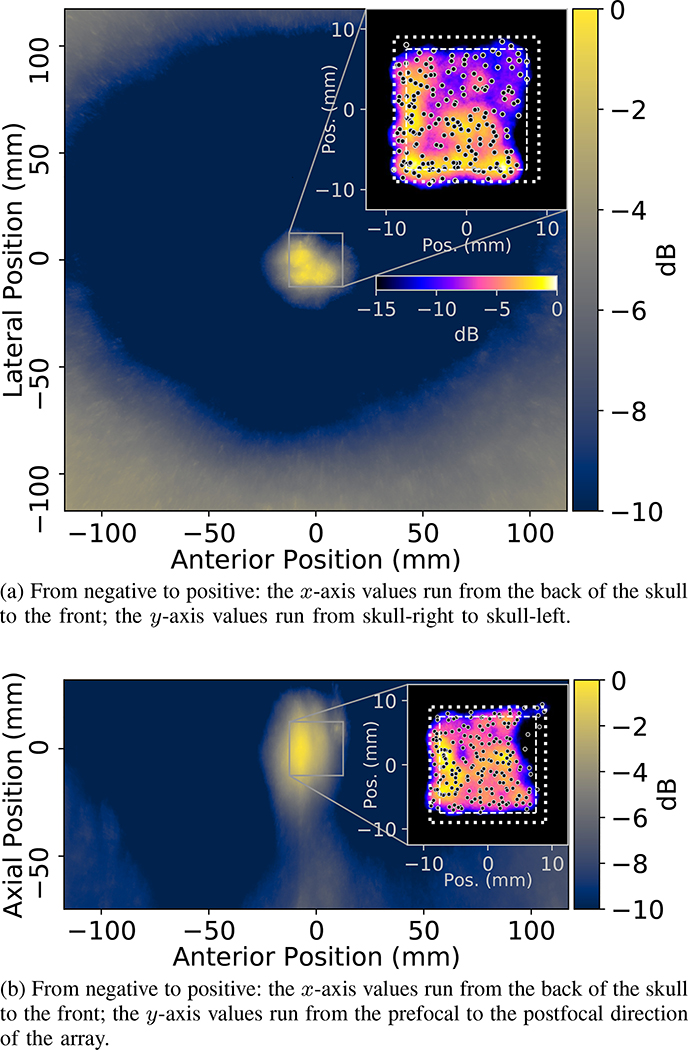

Fig. 7.

ACE feedback generated maps of the cavitation activity associated with the treatment delivered to generate lesion shown in Figure 6. The maps show the mean values of the signal amplitude fields (calculated using Eq. 3, and averaged over all pulses) within ±1.67mm of the planes of the shown maps, where the maps are centered about the geometric origin of the array. The skullcap is evident in the maps as the bright regions near the plot boundaries. The inset plots show heatmaps of the countable number of detected cavitation events (i.e. the applied dose) within the ±1.67mm bounds of the planes of the shown maps, under the assumption each event had a radius of 1.5mm; the heatmaps were normalized with respect to the maximum number of detected events within the mapped regions and brighter regions in the inset plots correspond to greater numbers of detected events at those locations. Note: the color-map/scaling of the inset plots is not equivalent to that of the underlying treatment maps, in the interest of space the colorbar corresponding to the inset plots is only shown in Fig. 7a. The black dots in the inset plots show the mean localization results of all cavitation events generated at each unique steering location within the mapped region. The square outlines in the inset plots show the boundary of the cubic region through which treatment was steered (interior, dashed lines) plus a 1.5mm margin (exterior, dotted lines) to account for the sizes of the bubbles. The map shown in Fig. 7b is approximately coaligned with the slice plane of the ablated volume in Fig. 6.

Although the ablation of the targeted volume was incomplete in regions, the maps of cavitation events generated using the ACE signals were in good overall agreement the morphological characteristics of the ablation zone created. That is to say, the signal amplitude within the treatment maps (Fig. 7) appeared to be lowest in the regions where the brain sample appeared to be only partially ablated, i.e. in the anterior and pre-focal regions and in the left hemisphere more generally. This was also well reflected in the maps of the applied dose (Fig. 7, inset plots), i.e. the countable number of detected cavitation events, where fewer cavitation events were detected in incompletely ablated regions.

On a point-by-point basis, the mean error in the predicted locations of the generated bubble clouds, with respect to the intended steering locations, was found to be approximately 2.25mm and reached a maximum of 3.9mm (in the anterior, postfocal direction). However, as no aberration correction could be applied in this experiment, and the actual positions of the generated bubble clouds could not be measured, these numbers correspond to the coupled metric of the steering and localization error and not the localization error alone. The typical steering error for histotripsy pulses applied through excised human skullcaps without aberration correction has previously been observed to be roughly 0.5mm to 1mm [39].

C. Localization Speed

The average time required to localize the generated bubble clouds was 10.3ms. Accounting for data-transfer times and other sources of latency in the system, cavitation events could be localized in real-time during experiments for pulses delivered at rates up to ∼70Hz. However, tests of the algorithm on a separate GPU (NVIDIA Quadro M520) indicate that it scales efficiently with the number of compute-cores and compute-core clock frequency of the GPU, and thus higher rates are likely possible with better hardware. For reference, in tests on the Quadro M520 (384 compute-cores @ 1019MHz vs. 3584 compute-cores @ 1999MHz for the GTX 1080 Ti), the average localization time was 190ms.

IV. Discussion

In this paper we have demonstrated the feasibility and accuracy of localizing transcranially-generated cavitation events in real-time during histotripsy using acoustic cavitation emission feedback signals. The ACE feedback localization results were demonstrated to be accurate to within ≤1.5mm of the actual positions of the generated cavitation events’ centers-of-mass but, when accounting for the sizes of the generated bubbles, were generally found to fall within their imaged volumes. In the in vitro experiment, the ACE-based map of cavitation activity during treatment was in good qualitative agreement with the morphological characteristics of the ablated volume. Localization in real-time at rates of up to 70Hz was achieved, but benchmark tests indicate that the localization algorithm scales efficiently and thus higher rates are likely possible with more powerful hardware.

The error in the localization results showed the largest bias towards the prefocal direction of the array. It has previously been demonstrated that bubble nucleation during histotripsy typically progresses from the prefocal- to the postfocal- edge of the generated bubble cloud [53]. Due to this progression, the ACE signals emitted by bubbles nucleated beyond the prefocal edge of the cloud must propagate through the bubbles nucleated before them, which can reduce their amplitudes, particularly in the direction of receiving elements aligned in the axial direction of the array. Such an effect would predispose the localization results to be aligned with the leading edge of the generated bubble clouds where the strongest signals originated rather than their centers-of-masses. As the ACE feedback localization results were generally found to be accurate to within the measured volumes of the generated bubbles, but were biased towards the bubbles’ leading/prefocal edges, such an effect could account for the axially-skewed directional biases observed in the localization results.

Separate hydrophone measurements investigating the potential influence of scattering effects from remnant bubbles in the field on the localization results also indicated some differences between the signals acquired for pulses delivered at PRFs ≥10Hz and those at 1Hz. Namely, the arrival times of the ACE signals were somewhat more variable for pulses delivered at PRFs ≥10Hz, and there were often more of them. These observations could be due to either scattering effects or the re-nucleation and subsequent emission of ACE signals by remnant bubbles in the focal volume from the previous nucleation event. The effects on the localization results in both cases would be similar. Owing to the short duration of the histotripsy pulses (≲4μs), the extent to which scattering effects, particularly from non- spatially coherent scatterers, would be expected to impact the localization results is limited. The generation of strong ACE signals from spatially coherent bubbles (or the scattering of incoming pulses off of them) at multiple locations in the field would tend to enlarge the volume of the signal amplitude field above the localization threshold and thus decrease the localization accuracy. The precision of the localization results would likely decrease as well as the position of the strongest emitter in volume would be effectively random and dependent on the distribution of remnant bubbles from the previous pulse. Both of these outcomes were observed in the localization results for pulses delivered at PRFs ≥10Hz.

The simplifying assumption about the uniform effect of the phase aberration across all receive elements would generally be expected to lead to a bias in the direction where the effects of the coupled metric of the skull’s sound speed and thickness generated the largest phase advances in the ACE signals relative to the mean. Estimates based on sound speed and thickness measurements of the skullcaps used in experiments suggest that localization errors due to this effect would have been on the order of up to 0.75mm to 1mm, which is in good agreement with the one-way error previously observed for histotripsy treatments delivered through the skullcap without aberration correction [39]. Although this effect would have also produced the largest biases in the prefocal direction, through all three skullcaps the components of the error it would have produced in the anterior/posterior direction were seen to be larger than those in the lateral direction, which may account for some of the component-wise inequalities observed in the L1-norm of the localization error.

Although the ACE localization results were generally close to, but not co-aligned with, the centers-of-masses of the generated bubble clouds, the images revealed that more often than not the localization results fell within the volumes encompassed by them. The ACE localization results thus do not tend to falsely represent where tissue damage is likely to have been generated during treatment. That is to say, the extent of damage generated during histotripsy has previously been shown to coincide with the size of the bubble clouds generated during treatment; because the ACE localization results fall within the volumes encompassed by generated bubbles, they would also fall within the damage region generated by them.

As aberration correction during the targeting phase could not be applied in the in vitro experiment, the localization error in the ACE feedback results could not be isolated from the targeting error for comparison with the results from the imaging experiments. Nevertheless, the good qualitative agreement between the ACE feedback treatment map and the generated lesion’s morphological features, particularly in the region where the ablation zone was poorly defined, suggest that the ACE feedback localization and mapping results were not significantly adversely affected by the presence of tissues. However, the larger overall error observed in this experiment does indicate that without some a priori knowledge of the targeting error, or other information about the skull’s acoustic properties, the ability to accurately localize the generated bubbles would be compromised.

The inability to accurately localize bubbles in the top, side, and front regions is strongly believed to be due to the limited 8-bit resolution of the ADCs and the design decision to maximize the dynamic range of receive system using the non-linear voltage compressor. These components created two separate but interrelated problems. First, the ACE signals from cavitation events generated in regions close to the surface of the skullcap were often contained within, or in close proximity to, the signals associated with reflections from the skullcaps, which themselves were typically well into the non-linear regime of the compressor. Owing to the much larger effective step size of the ADC in the compressor’s non-linear regime, which typically reached ≳350mV/level for the skull reflection signals, the resolving power of the ADC in relation to the overlying ACE signals – which had median amplitudes on the order of 1V (for bubbles generated in the central region) – was effectively reduced to only 2-bits.

This problem was exacerbated, and frequently superseded, by the weaker ACE signals generated by the smaller cavitation events in the top, side, and front regions of the skullcaps as well as the larger attenuations experienced by the ACE signals originating from those regions due to geometric factors associated with their close proximity to the skullcaps. This often resulted in the ACE signals from large swaths of elements falling below the minimum detection threshold of the receive system (∼50mV) even in instances where they were sufficiently separated from the skull reflection signals to be entirely within the linear regime of the compressor. Although it was possible in most cases to reliably extract ACE signals from subsets of the receiving elements for cavitation events generated in the non-central target regions, the number and spatial distribution of the elements were generally not sufficient to allow the cavitation events to be accurately localized. While the ability to resolve signals over the wide dynamic range the receive system was designed for is potentially useful, for instance in mapping the surface of the skull for the purposes of coregistration or for monitoring cavitation activity on the skull surface, in retrospect – incorporating a higher resolution ADC notwithstanding – a lower dynamic range with a less aggressive non-linear compressor and more low end sensitivity would have likely been a better investment. Even so, although resolving the described issues would likely expand the range over which localization in the non-central regions using ACE-based methods is possible compared to the current receive system, whether or not this is actually the case, and the extent to which the range of localizable targets in those regions would be expanded if it is, remains to be determined.

Some of the inaccuracies in the localization results, as well as the inability to localize bubbles outside the central target region, can likely also be attributed to design decisions in the localization algorithm. Although not employing more advanced aberration correction to account for the presence of the skullcap in the field during the localization process in this study was by design, it is understood that doing so would have improved localization accuracy. Indeed, in separate, post-hoc analyses of the acquired ACE signals, wherein the phase delays measured via hydrophone at the geometric origin of the array to correct for skull-induced aberrations during the targeting step of the experiments (Sec. II-D, Table II) were applied as corrections for aberrations during the localization step, the overall localization accuracy improved by approximately 16%, from 1.43 ± 0.76mm without aberration correction (Table III, [ Skullcap: All, @PRF: All ]) to 1.20 ± 0.68mm with aberration correction. Within individual [Skullcap, PRF] parameter groupings accuracy improved by as much as 32%, with the largest improvements observed through [ Skullcap: 2, @PRF: 100Hz ] where localization accuracy improved from 1.48 ± 0.92mm to 1.00 ± 0.62mm after applying aberration correction. The decision not to more thoroughly filter the acquired waveforms to separate out the ACE signals was heavily influenced by the exceedingly narrow bandwidth of the receiving elements of the array, which made separating components of the signals by frequency content largely ineffective; the negative effects of more aggressive signal filtering on computation time were also a consideration. In the calculation of the signal amplitude field used to localize the cavitation events (Eq. 3), the method of finding and storing only the maximum value of each voxel over the whole time iteration window and then finding the center-of-mass of the region above a prescribed threshold is prone to producing certain biases and errors in the results. For instance, if the time iteration window wasn’t adequately centered about the cavitation event, the calculated signal amplitude field would tend to be biased in the pre- or post-focal directions depending on the center point of the window in relation to the time point of nucleation. Likewise, if the ACE signals were comparable or weaker in amplitude to extraneous signal components in their vicinities, the center-of-mass of the signal amplitude field would be shifted towards those components. Although the algorithm was generally robust to errors of this type because signals originating from non-spatially coherent sources wouldn’t add together constructively in the field, reflected signals from the skullcaps would have been spatially coherent and any remnant components left behind following the background signal subtraction process would have been large, or at least comparable in amplitude to their surroundings.

While additional work is required to improve the accuracy of the ACE feedback localization results, and to expand the range of targets within the skull where it can be effectively used, the results of this study demonstrate the potential of ACE feedback localization schemes to greatly simplify the needs of transcranial histotripsy therapies as they can be used to monitor and accurately localize treatment in real-time. Although greater localization accuracy could be achieved by employing CT [54] or hydrophone-based [55] aberration correction during the localization step, and MR monitoring might still be required for treatments demanding even higher precision, the described ACE feedback localization methods could still be an effective tool for monitoring the treatment of larger volume targets where complete ablation of the target is not explicitly required. One such example might be for monitoring the treatment of large volume clots during the treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage, where the periphery of the clot could be left untargeted as a safety margin while still allowing a significant volume of the clot to be ablated for later aspiration. Many of the issues encountered in the present study have also been extremely informative in guiding the ongoing design and development of next-generation transmit-receive capable histotripsy devices, which will include modified driving circuitry to improve the receive bandwidth of the array elements and use 12-bit ADCs with variable gain amplifiers to increase the overall resolution and low end sensitivity.

V. Conclusions

The feasibility of using acoustic cavitation emission feedback to monitor and accurately localize transcranially-generated cavitation events in real-time during histotripsy treatment has been demonstrated. Localization results were shown to be accurate to within ≤1.5mm of the centers-of-masses of the generated bubble clouds. The accuracy of the localization results was observed to be only weakly dependent of steering location, decreasing by ≲ 40μm/mm in all but two cases, but showed general biases towards the transverse origin of the array in the prefocal direction. The choice of skullcap and treatment PRF were observed to impact the accuracy of the localization results in the 1Hz group and in the transition between the 1Hz and 10Hz groups, but generally did not impact localization accuracy across or between groupings at higher PRFs. The locations of the bubbles predicted using the ACE signals typically fell within the volumes encompassed by them and thus would not tend to misrepresent where damage is likely to be generated during treatment. The ACE-based map of cavitation activity generated in the in vitro experiment was in good qualitative agreement with the morphological observations of the generated ablation volume in the treated brain sample, suggesting that the method is not significantly adversely affected by the presence of tissues in the field. Real-time localization rates of up to 70Hz were achieved during experiments, but tests indicate that the algorithm scales efficiently which should allow for higher rates using more powerful hardware.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Focused Ultrasound Foundation, grant 24332, a grant from National Cancer Institute under Award Number R01-CA211217, and a grant from National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01-NS108042. The authors would like to thank D. A. Mueller and the Anatomical Donations Program at the University of Michigan for providing the skull samples used in this study.

Biography

Jonathan R. Sukovich received the B.S. and Ph.D. degrees in mechanical engineering from Boston University, Boston, MA, USA, in 2008 and 2013, respectively, where he studied laser interactions with water at high pressures and phenomena associated with high-energy bubble collapse events.

He joined the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, in the summer of 2013 to study histotripsy for brain applications. He is currently an Assistant Research Scientist with the Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Michigan. His research interests include high-energy bubble collapse phenomena, focused ultrasound therapies, and acoustic cavitation.

Jonathan J. Macoskey was born in Pittsburgh, PA, USA, in 1992. He received the B.S. degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA, in 2015, and the M.S. degrees in biomedical engineering from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, in 2016. He was awarded a joint Ph.D. degree in biomedical engineering and scientific computing from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, in 2019.

His research interests include real-time feedback mechanisms for histotripsy, ultrasound aberration correction, and deep learning for medical ultrasound.

Jonathan E. Lundt received the B.S. degree in physics from the University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, in 2008, and the M.S. degree in mechanical engineering from Boston University, Boston, MA, USA, in 2010. He was awarded a Ph.D. degree in biomedical engineering, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA in 2019.

From 2010 to 2014, he was a Mechanical Engineer of a venture-backed startup and a medical device engineering consultancy, both in Seattle, WA, USA. He was a Dean’s Fellow with Boston University. He is listed as Sole or Co-Inventor on seven issued and 12 pending patents. He is the founding President of the IEEE-UFFC student chapter at the University of Michigan. His research focuses on the development of histotripsy with electronic focal steering for the noninvasive ablation of large-volume tissue targets.

Tyler I. Gerhardson received the B.S. degree in biomedical engineering from Western New England University, Springfield, MA, USA, in 2015, and the M.S. degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Michigan, in 2017.

His current research interests include ultrasonic standing wave separators, ultrasound transducers, and focused ultrasound therapies.

Mr. Gerhardson received the Deans Award for Academic Excellence and the Biomedical Engineering Department Award for Outstanding Senior from Western New England University, a Scholarship and Fellowship from Tau Beta Pi, and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship.

Timothy L. Hall was born in Lansing, MI, USA, in 1975. He received the B.S.E. and M.S.E. degrees in electrical engineering and the Ph.D. degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, in 1998, 2001, and 2007, respectively.

He was a Circuit Design Engineer with Teradyne Inc., Boston, MA, USA, from 1998 to 1999 and a Visiting Research Investigator at the University of Michigan from 2001 to 2004. He is currently an Assistant Research Scientist with the Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Michigan. His research interests are in high-power pulsed RF-amplifier electronics, phased-array ultrasound transducers for therapeutics, and sonic cavitation for therapeutic applications.

Zhen Xu (S’05-M’06’) received the B.S.E. degree (highest Hons.) in biomedical engineering from Southeast University, Nanjing, China, in 2001, and the M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in biomedical engineering from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, in 2003 and 2005, respectively.

She is currently an Associate Professor with the Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Michigan. Her research is focused on ultrasound therapy, particularly the applications of histotripsy for noninvasive surgeries.

Dr. Xu received the IEEE Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control Society Outstanding Paper Award in 2006, the American Heart Association Outstanding research in Pediatric Cardiology in 2010, the National Institutes of Health New Investigator Award at the First National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering Edward C. Nagy New Investigator Symposium in 2011, and the Federic Lizzi Early Career Award from the International Society of Therapeutic Ultrasound in 2015. She is an associated editor for IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control (UFFC).

Appendix A

Point Spread Function of the Array

Although “images” of the signal amplitude field reconstructed from the acquired ACE signals, which show the cavitation events and skullcap around them, are presented in Fig. 7, direct imaging of the generated cavitation events, at least in a conventional sense, was not within the scope of the present study. Nevertheless, the described localization methods rely on techniques commonly employed in image forming and thus it is useful to provide details about the array’s point spread function (PSF) to inform on its potential resolving power in relation to the localization results presented. The PSF of the array was calculated based on ACE signals acquired through skullcap 1 from bubbles generated at a range of different focal steering locations, as well as from signals acquired from cavitation events generated in the free-field for comparison. As the localization results presented herein were generated in the absence of aberration correction, no aberration correction was performed on the ACE signals during the calculations of the PSFs. ACE signals through the skull were acquired from events steered through a 3 × 3 × 3 cubic grid of points measuring 24mm per side, centered about the array’s geometric origin; in the free field signals were only acquired from bubbles generated at the geometric origin. Table IV shows the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) dimensions of signal intensity maps generated using the acquired ACE signals as a function of the axial steering region; the values shown correspond to the means and standard deviations of the FWHM dimensions of the fields calculated for all 9 bubbles generated at each of the 3 axial steering levels.

TABLE IV.

FWHM Dimensions of Reconstructed Signal Intensity Maps vs Focal Steering Region

| Steering Region | FWHM dimensions (mm × mm × mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | std | ||

| [0, 0, 0] | Free field | 1.1 × 1.1 × 2.2 | N/A |

| Transcranial | 1.2 × 1.7 × 2.9 | N/A | |

| z = −12 mm | Pre-focal | 1.3 × 1.8 × 2.7 | 0.4 × 0.1 × 0.0 |

| z = 0 mm | Focal plane | 1.2 × 1.7 × 2.9 | 0.0 × 0.1 × 0.1 |

| z = 12 mm | Post-focal | 1.7 × 1.7 × 3.5 | 0.6 × 0.2 × 0.3 |

References

- [1].Lynn JG and Putnam TJ, “Histology of cerebral lesions produced by focused ultrasound,” The American journal of pathology, vol. 20, no. 3, p. 637, 1944. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fry WJ, Mosberg W Jr, Barnard J, and Fry F, “Production of focal destructive lesions in the central nervous system with ultrasound*,” Journal of neurosurgery, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 471–478, 1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hynynen K, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Raymond S, Weissleder R, Jolesz FA, and Sheikov N, “Focal disruption of the blood-brain barrier due to 260-khz ultrasound bursts: a method for molecular imaging and targeted drug delivery,” Journal of neurosurgery, vol. 105, no. 3, pp. 445–454, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Alexandrov AV, “Ultrasound enhancement of fibrinolysis,” Stroke, vol. 40, no. 3 suppl 1, pp. S107–S110, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tempany CM, McDannold NJ, Hynynen K, and Jolesz FA, “Focused ultrasound surgery in oncology: overview and principles,” Radiology, vol. 259, no. 1, pp. 39–56, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Choi JJ, Selert K, Gao Z, Samiotaki G, Baseri B, and Konofagou EE, “Noninvasive and localized bloodbrain barrier disruption using focused ultrasound can be achieved at short pulse lengths and low pulse repetition frequencies,” Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 725–737, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jeanmonod D, Werner B, Morel A, Michels L, Zadicario E, Schiff G, and Martin E, “Transcranial magnetic resonance imaging–guided focused ultrasound: noninvasive central lateral thalamotomy for chronic neuropathic pain,” Neurosurgical focus, vol. 32, no. 1, p. E1, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Elias WJ, Huss D, Voss T, Loomba J, Khaled M, Zadicario E, Frysinger RC, Sperling SA, Wylie S, Monteith SJ, et al. , “A pilot study of focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 369, no. 7, pp. 640–648, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Monteith SJ, Harnof S, Medel R, Popp B, Wintermark M, Lopes MBS, Kassell NF, Elias WJ, Snell J, Eames M, et al. , “Minimally invasive treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage with magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound: laboratory investigation,” Journal of neurosurgery, vol. 118, no. 5, pp. 1035–1045, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Monteith SJ, Kassell NF, Goren O, and Harnof S, “Transcranial mr-guided focused ultrasound sonothrombolysis in the treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage,” Neurosurgical focus, vol. 34, no. 5, p. E14, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Coluccia D, Fandino J, Schwyzer L, OGorman R, Remonda L, Anon J, Martin E, and Werner B, “First noninvasive thermal ablation of a brain tumor with mr-guided focusedultrasound,” Journal of therapeutic ultrasound, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 17, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gerhardson T, Sukovich JR, Pandey AS, Hall TL, Cain CA, and Xu Z, “Effect of frequency and focal spacing on transcranial histotripsy clot liquefaction, using electronic focal steering,” Ultrasound in medicine & biology, vol. 43, no. 10, pp. 2302–2317, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hynynen K and Jolesz FA, “Demonstration of potential noninvasive ultrasound brain therapy through an intact skull,” Ultrasound in medicine & biology, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 275–283, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pernot M, Aubry J-F, Tanter M, Thomas J-L, and Fink M, “High power transcranial beam steering for ultrasonic brain therapy,” Physics in medicine and biology, vol. 48, no. 16, p. 2577, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Marquet F, Pernot M, Aubry J, Montaldo G, Marsac L, Tanter M, and Fink M, “Non-invasive transcranial ultrasound therapy based on a 3d ct scan: protocol validation and in vitro results,” Physics in medicine and biology, vol. 54, no. 9, p. 2597, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].McDannold N, Clement G, Black P, Jolesz F, and Hynynen K, “Transcranial mri-guided focused ultrasound surgery of brain tumors: Initial findings in three patients,” Neurosurgery, vol. 66, no. 2, p. 323, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cline H, Schenck J, Watkins R, Hynynen K, and Jolesz F, “Magnetic resonance-guided thermal surgery,” Magnetic resonance in medicine, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 98–106, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ishihara Y, Calderon A, Watanabe H, Okamoto K, Suzuki Y, Kuroda K, and Suzuki Y, “A precise and fast temperature mapping using water proton chemical shift,” Magnetic resonance in medicine, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 814–823, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hynynen K, Vykhodtseva NI, Chung AH, Sorrentino V, Colucci V, and Jolesz FA, “Thermal effects of focused ultrasound on the brain: determination with mr imaging.,” Radiology, vol. 204, no. 1, pp. 247–253, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hynynen K, Clement GT, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, King R, White PJ, Vitek S, and Jolesz FA, “500-element ultrasound phased array system for noninvasive focal surgery of the brain: A preliminary rabbit study with ex vivo human skulls,” Magnetic resonance in medicine, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 100–107, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fry F and Barger J, “Acoustical properties of the human skull,” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 63, no. 5, pp. 1576–1590, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Connor CW and Hynynen K, “Patterns of thermal deposition in the skull during transcranial focused ultrasound surgery,” Biomedical Engineering, IEEE Transactions on, vol. 51, no. 10, pp. 1693–1706, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Clement G, White P, and Hynynen K, “Enhanced ultrasound transmission through the human skull using shear mode conversion,” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 115, no. 3, pp. 1356–1364, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].McDannold N, King RL, and Hynynen K, “MRI monitoring of heating produced by ultrasound absorption in the skull: in vivo study in pigs,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 1061–1065, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].White P, Clement G, and Hynynen K, “Longitudinal and shear mode ultrasound propagation in human skull bone,” Ultrasound in medicine & biology, vol. 32, no. 7, pp. 1085–1096, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pichardo S and Hynynen K, “Treatment of near-skull brain tissue with a focused device using shear-mode conversion: a numerical study,” Physics in medicine and biology, vol. 52, no. 24, p. 7313, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pichardo S, Sin VW, and Hynynen K, “Multi-frequency characterization of the speed of sound and attenuation coefficient for longitudinal transmission of freshly excised human skulls,” Physics in medicine and biology, vol. 56, no. 1, p. 219, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pinton G, Aubry J-F, Fink M, and Tanter M, “Effects of nonlinear ultrasound propagation on high intensity brain therapy,” Medical physics, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 1207–1216, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pinton G, Aubry J-F, Bossy E, Muller M, Pernot M, and Tanter M, “Attenuation, scattering, and absorption of ultrasound in the skull bone,” Medical physics, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 299–307, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Maxwell AD, Cain CA, Hall TL, Fowlkes JB, and Xu Z, “Probability of cavitation for single ultrasound pulses applied to tissues and tissue-mimicking materials,” Ultrasound in medicine & biology, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 449–465, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Xu Z, Ludomirsky A, Eun LY, Hall TL, Tran BC, Fowlkes JB, and Cain CA, “Controlled ultrasound tissue erosion,” IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control, vol. 51, no. 6, pp. 726–736, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Parsons JE, Cain CA, Abrams GD, and Fowlkes JB, “Pulsed cavitational ultrasound therapy for controlled tissue homogenization,” Ultrasound in medicine & biology, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 115–129, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xu Z, Fowlkes JB, Rothman ED, Levin AM, and Cain CA, “Controlled ultrasound tissue erosion: The role of dynamic interaction between insonation and microbubble activity,” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 117, no. 1, pp. 424–435, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wheat JC, Hall TL, Hempel CR, Cain CA, Xu Z, and Roberts WW, “Prostate histotripsy in an anticoagulated model,” Urology, vol. 75, no. 1, pp. 207–211, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vlaisavljevich E, Kim Y, Owens G, Roberts W, Cain C, and Xu Z, “Effects of tissue mechanical properties on susceptibility to histotripsy-induced tissue damage,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 59, no. 2, p. 253, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Vlaisavljevich E, Maxwell A, Warnez M, Johnsen E, Cain CA, and Xu Z, “Histotripsy-induced cavitation cloud initiation thresholds in tissues of different mechanical properties,” IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 341–352, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhang X, Owens GE, Gurm HS, Ding Y, Cain CA, and Xu Z, “Noninvasive thrombolysis using histotripsy beyond the intrinsic threshold (microtripsy),” Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, IEEE Transactions on, vol. 62, no. 7, pp. 1342–1355, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kim Y, Hall T, Xu Z, and Cain C, “Transcranial histotripsy therapy: a feasibility study,” Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control, IEEE Transactions on, vol. 61, no. 4, pp. 582–593, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sukovich JR, Xu Z, Kim Y, Cao H, Nguyen T-S, Pandey AS, Hall TL, and Cain CA, “Targeted lesion generation through the skull without aberration correction using histotripsy,” IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control, vol. 63, no. 5, pp. 671–682, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sukovich JR, Xu Z, Hall TL, Allen SP, and Cain CA, “Treatment envelope of transcranial histoptripsy applied without aberration correction,” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 140, no. 4, pp. 3031–3031, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sukovich JR, Cain CA, Pandey AS, Chaudhary N, Camelo-Piragua S, Allen SP, Hall TL, Snell J, Xu Z, Cannata JM, et al. , “In vivo histotripsy brain treatment,” Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 1, no. aop, pp. 1–8, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Roy RA, Madanshetty SI, and Apfel RE, “An acoustic backscattering technique for the detection of transient cavitation produced by microsecond pulses of ultrasound,” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 87, no. 6, pp. 2451–2458, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Pernot M, Aubry J-F, Tanter M, Boch A-L, Marquet F, Kujas M, Seilhean D, and Fink M, “In vivo transcranial brain surgery with an ultrasonic time reversal mirror,” Journal of neurosurgery, vol. 106, no. 6, pp. 1061–1066, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Farny CH, Holt RG, and Roy RA, “Temporal and spatial detection of hifu-induced inertial and hot-vapor cavitation with a diagnostic ultrasound system,” Ultrasound in medicine & biology, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 603–615, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Salgaonkar VA, Datta S, Holland CK, and Mast TD, “Passive cavitation imaging with ultrasound arrays,” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 126, no. 6, pp. 3071–3083, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]