Abstract

Considered a commensal, the Gram-negative anaerobe Fusobacterium nucleatum is a key member of the oral microbiome, due to its wide range of interactions with many oral microbes. While the periodontal pathogenic properties of this organism have widely been examined, its connotation with extra-oral infections including preterm birth and colorectal cancer now becomes apparent. Nonetheless, little is known about the mechanisms of pathogenicity and the associated virulence factors of F. nucleatum, most likely due to limited genetic tools and facile methodology. Here, we describe molecular techniques for the genetic manipulation of F. nucleatum, including marker-less, non-polar gene deletion, complementation, and Tn5 transposon mutagenesis. Further, we provide methodology to assess virulence potential of F. nucleatum, using a mouse model of preterm birth.

Basic Protocol 1: Generation of a galK mutant strain

Basic Protocol 2: Complementation of a mutant strain

Basic Protocol 3: Tn5 transposon mutagenesis of F. nucleatum

Basic Protocol 4: A mouse model of preterm birth

INTRODUCTION

Genetic tools for Fusobacterium nucleatum have been limited, albeit with a small number of plasmids that can be delivered to fusobacterial cells via electroporation (Kinder Haake, Yoder, & Gerardo, 2006; McKay, Ko, Bilalis, & DiRienzo, 1995). Early efforts by many laboratories led to generation of F. nucleatum mutants via a single homologous recombination event (Han, Ikegami, Chung, Zhang, & Deng, 2007; C. W. Kaplan et al., 2010; Kinder Haake et al., 2006), which potentially have polar effects. Here, we report a recently developed gene deletion method that generates markerless, non-polar, in-frame deletion mutants in F. nucleatum and Tn5 transposon mutagenesis that permits genome-wide screening (C. Wu et al., 2018).

Basic Protocols 1 and 2 describe methods for plasmid design, construction, and introduction into F. nucleatum for use in making deletion and complementation strains, respectively. Basic protocol 3 describes a procedure for construction of a Tn5 transposon library. Basic protocol 4 reports a mouse model of infection for which the effect of F. nucleatum on preterm birth can be studied.

CAUTION: Fusobacterium nucleatum is a Biosafety Level 2 (BSL-2) pathogen. Follow all appropriate guidelines and regulations for the use and handling of pathogenic microorganisms.

STRATEGIC PLANNING

Preparation and Growth on Agar or Liquid Medium

F. nucleatum strains are grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) supplemented with 1% Bacto peptone (TSP) plus 0.25% autoclaved cysteine (TSPC) or on TSPC agar plates or on BBL Columbia agar plates with 5% sheep blood (see Reagents and Solutions). TSPC plates should be freshly made under sterile conditions before use; plates can be air-dried inside a biosafety cabinet with filtered continuous airflow. Columbia agar plates can be stored at 4°C and should be used within ~2 weeks. When necessary, 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin, 15 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol, or 5 μg ml−1 thiamphenicol should be added to the medium.

Anaerobic Conditions

TSP can be combined with cysteine in aerobic conditions prior to inoculation. Inoculation of bacterial strains from glycerol stocks into media or spread onto a plate can be done in aerobic conditions. Cultured plates should be placed into an anaerobic chamber (5% CO2, 2% H2, and 93% N2) as quickly as possible. Once in anaerobic conditions, wrap plates with parafilm to prevent drying out. Optimal growth on either TSPC agar or BBL Columbia agar plates is obtained after 2–3 days or longer dependent on mutant strains.

BASIC PROTOCOL 1: GENERATION OF A galK MUTANT STRAIN

Galactokinase (GalK) has been used as a marker for counterselection in many bacterial systems. In order to use this strategy, a galK deletion strain needs to be created in F. nucleatum. The following method utilizes a nonreplicative vector, astute primer design, and allelic exchange to generate an isogenic galK derivative of the clinical isolate ATCC 23726. This vector, pCWU5-ΔgalK (C. Wu et al., 2018), contains a thiamphenicol resistance gene, allowing the selection of strains harboring the plasmid. After culturing candidate clones to allow for a double-crossover homologous recombination event, a counter selection on 2-deoxy-D-galactose (2-DG) selects for the candidate clones lacking galK and complete loss of the plasmid. The resulting strain permits the subsequent generation of a markerless, nonpolar, in-frame deletion mutant of galK.

Note: Prepare E. coli DH5α chemically competent cells and F. nucleatum competent cells (see protocol 3) prior to beginning the protocol. All experiments using E. coli are performed under aerobic conditions.

Materials

Viable F. nucleatum strain ATCC23726 on a TSPC agar plate (see Reagents and Solutions)

Purified genomic DNA from ATCC 23726

Ice

Petri dishes

L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate

Sodium Sulfide nonahydrate (Na2S·9H2O)

Tryptic Soy Broth

Bacto™ peptone

LB agar plates with 15 μg/ml chloramphenicol

TSPC agar plates with 5 μg/ml thiamphenicol

TSPC agar plates with 0.25% 2-deoxy-D-galactose (2-DG)

Dry ice

50% glycerol

100% ethanol

10% glycerol supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2

1.7 mL Eppendorf tubes

0.2 mL individual PCR tubes

16 mm glass culture tubes

16 mm culture tube caps

Standard laboratory pipette tips

Standard laboratory pipette set

E. coli DH5α chemically competent cells

F. nucleatum competent cells (see Basic Protocol 3, steps 1–4)

pCWU5 (C. Wu et al., 2018) (available upon request)

1.5 mL cryogenic tubes

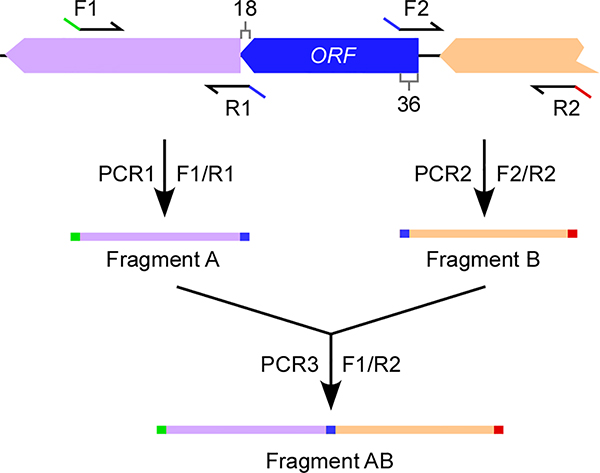

Custom primers (restriction enzyme sites underlined) for galK deletion (Fig. 1)

Figure 1: Generation of a gene deletion cassette.

This procedure is applicable to any gene of interest including galK. An example is an open reading frame (ORF) with upstream- and downstream-genes. Two sets of primers (F1/R1 and F2/R2) are used in two PCR reactions generating Fragments A and B. Forward Primer F1 and Reverse Primer R2 contain a restriction enzyme site (green and red, respectively) present in the multiple cloning site of pCWU5 or pCM-GalK. Reverse Primer R1 and Forward Primer F2 contain a complementary sequence for annealing in PCR Reaction 3, creating a template for PCR-amplification of Fragment AB. Alternatively, Reverse Primer R1 and Forward Primer F2 harbor a unique restriction enzyme site for subsequent ligation to join Fragments A and B; in this case PCR3 is omitted (see Generation of a galK deletion mutant).

Forward 1 (F1): GGCGGAATTCACAATATTAATGATTTAAAATAG

Forward 2 (F2): GGCGGGTACCGCTAGTTTCTATATAGCAAATATTGGAG

Reverse 1 (R1): GGCGGGTACCCCAATTAAATTCACTCTACCTGGTGA

Reverse 2 (R2): GGCGTCTAGAAACAGCATCAATATGTCCTGTGATTAAG

Custom primers for gene deletion (Fig. 1)

Forward 1 (F1)

Forward 2 (F2)

Reverse 1 (R1)

Reverse 2 (R2)

pCWU8 (C. Wu et al., 2018) (available upon request)

pCM-galK

PCR reagents:

5X Phusion HF Buffer (NEB)

10 mM dNTPs (NEB)

Phusion DNA Polymerase (NEB)

Nuclease free water

DNA Digest regents:

Restriction enzymes of choice (2 unique from MCS) (NEB)

10X Cutsmart Buffer (NEB)

Ligation reagents:

T4 DNA Ligase Buffer (10X) (NEB)

T4 DNA Ligase (NEB)

APEX 2X Taq RED Master Mix (Genesee Scientific)

Electroporation cuvettes

Gel-extraction kit

Razorblade

Agarose

TAE Buffer

Plasmid DNA minipreps purification kit (Qiagen)

Gene Pulser Mxcell electroporation system

Tabletop centrifuge

Thermal cycler

Anaerobic incubator maintained at 37°C

Nanodrop

1.5 ml cryogenic tubes

Part 1: Construction of a galK deletion mutant

-

1

Design two sets of primers (F1/R1 and F2/R2; see Materials) for PCR-amplification of ~ 1kb-regions upstream and downstream of galK, using chromosomal DNA of strain ATCC 23726 as template (see Fig. 1)

-

2

Perform two PCR reactions: Reaction 1, using primers F1/R1, generates Fragment A and Reaction 2 with primers F2/R2 generates Fragment B. Purify the resulting PCR products using a Qiagen DNA purification kit.

-

3Digest the purified PCR products with appropriate restriction enzymes (EcoRI/KpnI for Fragment A and KpnI/XbaI for Fragment B) and gel purify the digested products, followed by ligation of the treated fragments into pCWU5 (100 ng), precut with EcoRI and XbaI.

- Digestion reaction (final volume of 50 μl) at 37°C for at least 4 h:

DNA up to 1 μg 10x CutSmart Buffer 5 μl Restriction Enzyme 1 1 μl Restriction Enzyme 2 1 μl Nuclease-free water up to 50 μl - Ligation Reaction (final volume of 20 μl) at room temperature for 2 h.

Vector DNA (4 kb) 100 ng Insert DNA 150 ng 10X T4 DNA Ligase Buffer 2 μl T4 DNA Ligase 1 μl Nuclease-free water up to 20 μl

-

4Transform the above ligation reaction product into chemically competent cells of E. coli DH5α

- Heat shock protocol for transformation

- Thaw E. coli chemically competent DH5α strain on ice (~10 min)

- Add 1–5 μL ligated DNA (no more than 100 ng) to 50 μL E. coli chemically competent DH5α strain

- Put cells back onto ice for 15–40 mins

- Heat shock cells for 50 sec at 42°C

- Put cells back onto ice for 2 min

- Add 600 μL LB to cells and transfer to 16mm glass culture tube

- Incubate with shaking for 1 h at 37°C

- Plate 100 μL and 200μL, if needed, onto LB plates with 15 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol

- Incubate both plates overnight at 37°C

-

5

Screen for candidate clones via colony PCR

Using a pipette tip to pick up a small amount of a single colony from plates and respend it in the PCR reaction mix in b.

- Colony PCR reaction (final volume of 20 μl)

APEX 2X Taq RED Master Mix 10 μl Primer F1 1 μl Primer R2 1 μl Nuclease-free water up to 20 μl Verify the amplicons by gel electrophoresis using 5 μl PCR products.

-

6

Use Plasmid DNA minipreps purification kit to purify plasmid DNA from positive clones in step 5 and sequence.

-

7

Determine plasmid DNA concentrations using Nanodrop

-

8

Transform plasmid into Fusobacterium nucleatum strain ATCC23726

- Transformation by electroporation

- Pre-chill 0.1 mm gene pulser cuvette

- Thaw F. nucleatum competent cells on ice (~10 min)

- Add 10 μL (~1 μg) plasmid DNA from step 12 to 100 μL of competent cells

- Immediately transfer 100 μL of competent cells with plasmid into cold cuvette

- Shock cells under the following conditions: 2.5 kV, 25 μF, 200 Ω

- Quickly transfer shocked competent cells into 1 mL TSPC

- Incubate cells in an anaerobic chamber at 37°C for 3 h

- Plate onto TSPC agar plates containing 5 μg/mL Thiamphenicol (Thia)

- Incubate plates under anaerobic conditions for 3 days at 37°C

-

9

Select two Thia-resistant colonies and inoculate individual cultures of 8 mL TSPC broth under anaerobic conditions overnight at 37°C

-

10

Dilute overnight growth 1000-fold into fresh TSPC media and subsequently spread 50 μL on TSPC agar plates containing 0.25% 2-deoxy-D-galactose (2-DG). Incubate the plates under anaerobic conditions for 3 days at 37°C

-

11

Use sterile toothpicks to pick 10 single colonies from step 10 for colony-PCR using primers F1 and R2 to confirm the absence of galK.

-

12

Selective candidate clones are prepared for storage by inoculating individual colonies into 8 mL TSPC overnight under anaerobic conditions at 37°C

-

13

Prepare glycerol stock of candidate strains for −80°C storage

Put 600 μL of cultures into labeled 1.5 mL cryogenic tubes and spin at 6000 RPM for 5 min

Remove and discard the supernatants

Resuspend cell pellets in an additional 600 μL of culture and spin at 6000 RPM for 5 min

Remove and discard the supernatants

Resuspend the cell pellets in a final 600 μL of TSPC

Add 400 μL of 50% glycerol and gently mix

Store the cryogenic tubes in −80°C freezer

Part 2: Generation of a deletion mutant using the ΔgalK background strain

This protocol is used to generate deletion mutants of non-essential genes from the background strain ΔgalK as described in Part 1. The suicide vector pCM-GalK or pCWU8 were used (C. Wu et al., 2018), which expresses GalK as a counterselection marker. To create a deletion construct, approximately 1-kb regions upstream and downstream of a targeted gene are PCR-amplified, fused together, and then cloned into pCM-GalK or pCWU8. The resulting plasmid is electroporated into the F. nucleatum ΔgalK strain and integration of this plasmid into the bacterial chromosome via a single crossover event is selected by Thia. To initiate a second homologous recombination event, resulting in plasmid excision, Thia-resistant cells are grown in the absence of Thia and selected by growing bacteria on 2-deoxy-D-galactose (2-DG) containing plates. 2-DG-resistant cells are verified for the absence of the targeted gene/protein by colony PCR and Western blotting, if antibodies are available.

-

14

Design and order primer pairs for overlapping PCR. For the cloning procedure described below, four primers are needed (see Materials). Primer Forward 1 (F1) should have a restriction enzyme site matching one found within the multi-cloning site of pCM-GalK (C. Wu et al., 2018). Primer Reverse 2 (R2) should contain a reverse complement sequence followed by a second unique restriction enzyme site. Primer Forward 2 (F2) and Primer Reverse 1 (R1) have overlapping complementary regions that permit them to anneal together in PCR reaction 3 (see step 2). Primer F2 should be complementary to the start of primer R1 (blue line) at the 5’ terminus (Fig. 1). Of note, this primer design is applicable to any other targeted genes.

-

15

Amplify the upstream region of the target gene using F1 and R1 generating ‘Fragment A.’ In a separate reaction, amplify the downstream region of the target gene using F2 and R2 generating ‘Fragment B.’ Use correct melting temperature from primer design and elongation time of 15–30 seconds/kb.

-

16

In a third PCR reaction Fragments A and B are annealed, creating a template for amplification of Fragment AB using primers F1 and R2 (Fig. 1).

-

17

Digest Fragment AB and pCM-GalK using the restriction enzymes that match the cut sites at the end of F1 and R2 (see Step 3, Part1).

-

18

For ligation, transformation, colony-PCR, please see Steps 3–7, Part 1.

-

19

Transform the generated plasmid into F. nucleatum strain ΔgalK (see Step 8, Part 1).

-

20

Select three Thia-resistant colonies and inoculate individual cultures of 8 mL TSPC broth under anaerobic conditions overnight at 37°C

-

21

Dilute overnight growth 1000-fold into fresh TSPC media and subsequently spread 50 μL on TSPC agar plates containing 0.25% 2-deoxy-D-galactose (2-DG). Incubate the plates under anaerobic conditions for 3 days at 37°C.

-

22

Use sterile toothpicks to pick single colonies from step 8 and streak onto TSPC plates containing 0.25% 2-DG, followed by streaking onto TSPC plate containing 5 μg/mL Thia and 0.25% 2-DG. Incubate under anaerobic conditions overnight at 37°C.

-

23

Select 10–20 Thia-sensitive colonies for colony PCR to screen for mutants lacking galK using primers F1 and R2.

-

24

Selective candidate clones are prepared for storage by inoculating individual colonies into 8 mL TSPC overnight under anaerobic conditions at 37°C.

-

25

Prepare glycerol stock of candidate strains for −80°C storage (see Step 13, Part 1).

BASIC PROTOCOL 2: COMPLEMENTATION OF A MUTANT STRAIN

To rescue a mutant strain, complementation is performed by cloning a gene of interest into an E. coli/F. nucleatum shuttle vector, and the resulting vector is introduced into this mutant by electroporation.

Note: Prepare chemically competent cells of E. coli DH5α and F. nucleatum strains prior to beginning the protocol.

Note: The previously reported shuttle vector pCWU6 (C. Wu et al., 2018) contains multiple cloning sites and mCherry under the Corynebacterium diphtheriae promoter rpsJ.

Materials

E. coli DH5α chemically competent cells

F. nucleatum competent cells (see Basic Protocol 3, steps 1–4)

Viable F. nucleatum strains on a TSPC agar plate (see Reagents and Solutions)

Purified genomic DNA from ATCC23726

pCWU6 (C. Wu et al., 2018) (available upon request)

Ice

Petri dishes

L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate

Tryptic Soy Broth

Bacto™ peptone

LB agar plates with 15 μg/ml chloramphenicol

TSPC agar plates with 5 μg/ml thiamphenicol

1.7 mL Eppendorf tubes

0.2 mL individual PCR tubes

16 mm glass culture tubes

16 mm culture tube caps

Standard laboratory pipette tips

Standard laboratory pipette set

One set of primers per gene complementation

PCR reagents:

5X Phusion HF Buffer (NEB)

APEX 2X Taq RED Master Mix (Genesee Scientific)

10 mM dNTPs (NEB)

Phusion DNA Polymerase (NEB)

Nuclease free water

Digest reagents:

Restriction enzymes of choice (2 unique)

10X Cutsmart Buffer (NEB)

Ligation reagents:

T4 DNA Ligase Buffer (10X) (NEB)

T4 DNA Ligase (NEB)

Electroporation cuvettes

Gel-extraction kit

Razorblade

Agarose

TAE Buffer

Plasmid DNA minipreps purification kit (Qiagen)

Nanodrop

Gene Pulser Mxcell electroporation system

Tabletop centrifuge

Thermal cycler

Anaerobic incubator maintained at 37°C

1.5 ml cryogenic tubes

Construction of a plasmid complement strain

Detailed protocols of PCR, digest, ligation, and gel purification reactions are found in Basic Protocol 1.

Design primers to PCR-amplify a gene of interest and its promoter region from F. nucleatum chromosomal DNA, with restriction enzyme sites on each end of primers appropriately

- Run PCR to amplify gene

- Confirm amplicons on gel: Load a total of 50 μl PCR products on multiple 1% agarose gel lanes for separation and isolation by electrophoresis

- Gel-purify DNA fragments: Cut DNA fragments from gel for purification (take a little gene as possible).

Digest 300 ng vector pCWU6 and 500 ng gel-purified products with restrictions enzymes according to step 1 at 37°C for 2 h. (For detailed explanation, see Basic Protocol 1, Part 1, Step 3).

Ligate the two digested DNA fragments together.

- Transform into E. coli DH5α

- Plate on LB + 15 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol (Cm) for plasmid selection

Screen candidate clones by performing colony-PCR and sequencing plasmid DNA.

-

Culture positive E. coli clones into 4 mL LB Agar + Cm

Incubate overnight at 37°C shaking at 250 RPM

Use Plasmid DNA minipreps purification kit to collect plasmid DNA.

Determine plasmid DNA concentrations using Nanodrop.

Transform the resulting plasmid into a respective F. nucleatum mutant strain (please see Step 8 in Part 1 of Basic Protocol 1 for details).

Select 5–10 Thia-resistant colonies to screen for the presence of the gene of interest by colony PCR amplification using forward and reverse primers.

Verified colonies are used to inoculate cultures of 8 mL TSPC overnight under anaerobic conditions at 37°C.

Prepare glycerol stock of strain for - 80°C storage (see Step 13 in Part 1 of Basic Protocol 1 for details).

BASIC PROTOCOL 3: TN5 TRANSPOSON MUTAGENESIS OF F. NUCLEATUM

Transposon mutagenesis is highly valuable for identification of virulence factors in many bacterial systems. A Tn5 transposon system has been developed for F. nucleatum, revealing an adhesin involved in bacterial coaggregation, adhesion, and preterm birth from screening a small library of mutants (Coppenhagen-Glazer et al., 2015). We previously reported a highly efficient Tn5 system producing more than 24,000 clones, representing 10-fold genome coverage, in a single transposition reaction (C. Wu et al., 2018). A detailed protocol of this improved Tn5 transposon method is described here that permits future genome-wide screenings of virulence factors.

Materials

F. nucleatum ATCC 23726

TSPC medium (see recipe)

LB agar plates with 15 μg/ml chloramphenicol

TSPC agar plates with 5 μg/ml thiamphenicol

37°C, 5 % CO 2 incubator

Sterile water

Sterile 10% glycerol and 100% glycerol

Disposable culture glass tubes

50 mL centrifuge tubes with printed graduations

Sterile 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes

Spectrophotometer and plastic cuvettes for OD600 measurement

Dry ice

Plasmid pMOD-catP (C. Wu et al., 2018)

EZ-Tn5 transposase (Epicentre)

PvuII enzyme (NEB)

TSPC agar plates with and without 5 μg/mL thiamphenicol

0.1 cm electroporation cuvettes (Fisher)

Electroporator

Sterile spreader

96-well plates

Toothpicks

Anaerobic chamber with air (10% CO2, 10% H2 and N2 80%)

2xTaq RED Master Mix Kit (Apex BioResearch Product)

Preparation of F. nucleatum competent cells

-

1

Streak F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 from a frozen stock on a TSPC agar plate and incubate 3 days in an anaerobic chamber at 37 °C to obtain single colonies.

-

2

Inoculate a colony of F. nucleatum into an 8 mL of TSPC and incubate statically overnight at 37 °C 5% CO2 incubator. The next day, transfer all 8 mL of the overnight culture into 42 mL of fresh TSPC in a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Grow cells at 37 °C until the OD600 reaches 1.2.

-

3

Chill the culture on ice for at least 10 min. Harvest the cell pellet by centrifugation at 4°C and discard the supernatant. Wash the cell pellet twice with 25 mL of prechilled sterile water. Resuspend the bacteria in 1 mL of 10% cold glycerol, and then aliquot into 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes (~200 μL each).

-

4

Snap-freeze the samples with a dry-ice-ethanol bath, and store at −80°C.

Prepare the Tn5 transposome

-

5

Prepare for about 5 μg plasmid pMOD-catP (C. Wu et al., 2018) by pooling 10 plasmid preps.

-

6

Digest pMOD-catP with enzyme PvuII at 2 h 37°C and separate Tn5 transposon DNA from vector backbone from the digestion products by gel extraction.

-

7

Take 2 μl of Tn5 transposon DNA (about 1 μg) cut out from pMOD-catP, mix with 4 μL EZ-Tn5 transposase (Epicentre) and 2 μL 100% glycerol. Incubate the reaction for 4 h at room temperature and then store at −20°C until use.

Electroporation

-

8

Pre-chill 0.1mm cuvette at −20°C.

-

9

Prepare 8 mL TSPC medium and aliquot 1 mL in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube.

-

10

Thaw a tube of competent cells (200 μL), previously kept at −80°C, on ice. Add 1.5 μL of transposome to the F. nucleatum competent cells.

-

11

Incubate on ice for at least 10 min. Transfer 100 μL of competent cells mixture to a pre-cold cuvette.

-

12

Electroporation condition: 2.5 kV, 25 μF, 200 Ω.

-

13

Quickly transfer for shocked competent cells into 1 mL TSPC medium; repeat for the remaining 100 μl competent cells for electroporation.

-

14

Put the tube into a 5% CO2 incubator for 3 hours at 37°C.

-

15

Spread 20 μl aliquots of transposon-treated cultures onto TSPC agar plates (a total of ~60) with 5 μg/mL thiamphenicol.

-

16

Inoculate plates into anaerobic chamber at 37°C for 3 days.

-

17

Tn5 mutants are individually picked by toothpicks and stored in 96-well plates at – 80°C for future studies

Characterization of Tn5 insertion by single primer one-step PCR (SOS-PCR)

-

18

Use 2 μl portion of overnight cultures of individual transposon mutant as DNA template and directly add to a 50 μL PCR mixture consisted of 1.0 X Taq RED Master Mix Kit (Apex BioResearch Product) and 0.4 μM FnTn5-F1 primer (5’- GCAAAAACATCGTAGAAATACGGTG-3’).

-

19

Run a PCR program: started with 5 min at 95°C, followed by 20 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 50°C, and 3 min at 72°C; this was immediately followed by 30 cycles, with each cycle consisting of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 30°C, and 2 min at 72°C and then 30 cycles, with each cycle consisting of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 50°C, and 2 min at 72°C. The PCR program ended with 10 min at 72°C.

-

20

Gel purified the generated PCR products and use 50 ng of purified DNA for DNA sequencing with 25 ng of FnTn5-F2 primer (5’-GGCTTAAAACAAGGATTTT-3’).

-

21

Analyze the generated sequences against the genomic sequence of F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 (https://biocyc.org/) to identify Tn 5 insertion sites.

BASIC PROTOCOL 4: A MOUSE MODEL OF PRETERM BIRTH

The following protocol, adapted from Han’s group (Han et al., 2004), describes a procedure to examine the virulence potential of F. nucleatum. Groups of five pregnant female mice per strain are challenged at day 16 or 17 with an IV injection of fusobacteria, and the resulting number of live and dead pups born over the following 7–9 days is used as the readout of pathogenicity. The number of bacterial colony forming units (CFU) reported here is relative to the ΔgalK strain, and additional measures of strain specific LD50 may be required to generate meaningful data.

Materials

10 week old CF-1 mice, ratio of 2 females per male (Charles River: CF-1)

DPBS 10x – (Gibco: 14080–055) Diluted with MilliQ water water and adjusted to pH=7.2 with KOH

0.22 μm Centricon filters (Sigma-Aldrich)

30-gauge needles

1cc tuberculin syringes

Tail vein restraint with dorsal access (Braintree Scientific; Model TV150STD)

Cages, housing, feed, enrichment as prescribed by your IACUC committee or local equivalent

Infection of animals

Mice are housed with a ratio of one male to two females. Housing, bedding, feed and enrichment should be in accordance with your institution’s IACUC or local equivalent. All animals described here are fed autoclaved food and water, and they are handled in a laminar flow hood in a BSL2 room, and housed in sterilized filtered-topped cages.

After co-housing animals, female mice should be examined daily for the presence of sperm plug, indicating breeding; this would mark the first day of gestation.

Remove males after 48 hours and maintain paired females in existing cages.

Inoculate 10 ml of bacterial cultures in TSPC in an anaerobic chamber at 37°C as described to be ready 17 days after noting the sperm plug or day 17 of gestation.

When fusobacterial cells reach mid-log phase, measure OD600, and harvest bacteria by centrifugation (5000g, 10 minutes).

Aspirate media and wash pellets in ice cold DPBS, re-pellet.

Aspirate the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellets in ice cold DPBS to a concentration of 5×108.

Immediately inject pregnant female mice with 100 μL fusobacteria for a final dose of 5×107 CFU per mouse.

Monitor animals for immediate adverse effects including septic shock: Animal should be monitored at least 30 minutes post-injection or until normal eating and drinking behaviors resume. Request veterinary assistance if body conditions degrade beyond limits (ribs and vertebrae easily palpable, poor grooming, loss of body weight, etc.)

Monitor animals twice daily for the following 10 days or until all litters are recorded

Reagents and Solutions

LB media (1 L)

Luria Broth power (Fisher): 20 g

Water: up to 1 L

Thoroughly mix and autoclave.

LB Agar (0.5 L)

LB power: 10 g

Agar: 7.5 g

Water: up to 0.5 L

Thoroughly mix all components with water up to 0.5 L and autoclave.

TSP media (1 L)

Tryptic soy broth media: 30 g

BactoTM peptone: 10 g

Water: up to 1L

Thoroughly mix all components with water up to 1 L and autoclave.

L-Cysteine stock (100 g/ml)

10 g L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate (Sigma-Aldrich; C7880): 10 g

Water: 100 ml

Hungate tubes

Completely dissolve 10 g L-cysteine in 100 ml water before transferring 8–10 ml to Hungate tubes prior to autoclaving. Stoppers should not be removed, and aliquots of L-cysteine solution should be removed with a needle and syringe.

TSPC Agar plates

Tryptic soy broth powder: 15 g

BactoTM peptone: 5 g

Agar: 7.5 g

L-Cysteine stock (see above)

Water: up to 0.5 L

Thoroughly mix all components except cysteine, autoclave, cool in 56°C water bath for ~20 minutes, add 5 mL L-cysteine stock, and pour ~25 mL into 100 mm petri dishes under sterile conditions.

Columbia agar

Columbia broth powder (Fisher, BD294420): 15 g

Agar: 7.5 g

Water: up to 0.5 L

Thoroughly mix all components and autoclave.

DPBS (pH 7.4)

50 ml 10x DPBS (Gibco; 14080–055)

450 ml MilliQ water

KOH for adjusting pH

Add 50 ml of 10x DPBS in 450 ml water, adjust pH to 7.4, and filter-sterilize.

Commentary

Background Information

Described as early as 1920s (Jackins & Barker, 1951), F. nucleatum is a Gram-negative obligate anaerobe abundantly found in the human oral cavity and notably interacts with many bacterial species including Actinobacillus, Actinomyces, Bacteroides, oral streptococci, Porphyromonas, and Veillonella (Kolenbrander, Andersen, & Moore, 1989; Rosen, Nisimov, Helcer, & Sela, 2003), as well as the fungal pathogen Candida albicans (Grimaudo & Nesbitt, 1997; T. Wu et al., 2015). A few adhesins have been identified from F. nucleatum to be associated with this polymicrobial interaction, or coaggregation, including RadD (C. W. Kaplan, Lux, Haake, & Shi, 2009), Aid1 (A. Kaplan et al., 2014), and Fap2 (C. W. Kaplan et al., 2010). A recent study revealed that the cell division factors FtsX and EnvC influence the co-aggregative process and biofilm formation (C. Wu et al., 2018). While F. nucleatum is known to be associated with periodontitis (Han, 2015), in recent years, it has been implicated in a multitude of human diseases, including preterm birth and colorectal cancer (CRC) (Abed et al., 2016; Bullman et al., 2017; Han, 2015; Han et al., 2004; Rubinstein et al., 2013). An adhesion called FadA was shown to promote cellular invasion and placental colonization (Ikegami A, 2009). FadA binds vascular endothelial cadherin, altering endothelial integrity (Fardini Y, 2011). More recently, FadA is linked to promotion of colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling (Rubinstein et al., 2013). Intriguingly, the coaggregation factor Fap2 has been shown to bind D-galactose-b(1–3)-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (Gal-GalNAc) that is highly expressed in CRC cells (Abed et al., 2016). Given the presence of more 2,000 open reading frames in the genome of a given clinical isolate (Umaña A, 2019), it is obvious that our understanding of virulence mechanisms of F. nucleatum is limited. Considering that many of the necessary studies to answer the questions associated with F. nucleatum-mediated maladies require the genetic manipulation of the F. nucleatum genome, it is important to have facile genetic tools.

The clinical isolate, F. nucleatum ATCC23726, is used in the lab for its well-characterized role in adhering early and late colonizers of bacterial biofilms and thus being crucial to uphold the structure and integrity of the oral microbiome (Allen-Vercoe et al., 2011; Han, 2015). Our objectives in developing tools to genetically modify F. nucleatum ATCC23726 are three-fold. First, we aimed to create an isogenic galK derivative of the clinical isolate ATCC 23726 to permit targeted gene deletions. In addition, we expanded an E. coli/ F. nucleatum shuttle vector that warrants gene complementation via electroporation. Second, we aimed to generate a large library of Tn5 transposon mutants. Since F. nucleatum has been implicated in preterm birth and term stillbirths in part, through its isolation from the amniotic fluid, placenta, and chorioamnionic membranes of mothers delivering prematurely (Han YW et al. 2004), we aimed to evaluate the virulence potential of F. nucleatum mutant strains in a mouse model of preterm birth. Use of these mouse models has the potential to characterize the patterns of infection and would lead to novel discoveries of F. nucleatum-induced phenotypes. The tools described here serve to advance our understanding of F. nucleatum ATCC23726 virulence and accelerate research in the oral biology field.

Critical Parameters and Troubleshooting

Bacterial transformation via electroporation

It is critical to maintain a sufficient population of viable cells for successful transformation. It is inevitable to have some loss in viability of competent cells following electroporation. Low yield of transformants may occur if competent cells are handled aggressively. In preparation of competent cells, they should be handled as gently as possible; mixing cells via vortex should be avoided. A common way to assess viable cell count is to plate some transformants on an agar plate lacking antibiotics. This count will indicate whether the failure or insufficiency of transformation is due to lack of viable cells or uptake of the plasmid DNA.

Primer Design

To achieve a double crossover homologous recombination event, it is imperative that the primers correctly amplify the gene of interest with modifications to have an in-frame deletion event occur. To avoid potential polar effects on downstream genes, it is recommended that primers R1 and F2 start at nucleotides 18 and 36 from the start and stop codons, respectively, depending on the potential promoter length of the downstream genes (Fig. 1). Some other primer recommendations include using a primer length of 18–24 base pairs, primers containing 40–60% GC content, and starting and ending primer sequence with 1–2 GC pairs. In addition, it is recommended that the melting temperature (Tm) of primers should be between 50°C −60°C, primer pairs are within 5°C of each other (the closer the better), primer pairs do not have complementary regions (unless otherwise specified), and palindromic or repetitive sequences are avoided.

Anticipated Results

For Basic Protocols 1 and 2, the transformation efficiency with an E. coli/F. nucleatum shuttle vector is expected to be approximately 106 CFU per microgram of plasmid DNA. In addition, the efficiency of a double-crossover homologous recombination event, leading to deletion of non-polar, in-frame deletion mutants, is expected to be less than 0.1%.

For Basic Protocol 3, one Tn5 transposome reaction normally generates more than 20,000 independent clones with single insertions. Double or multiple insertions by Tn5 transposon are rare. This can be verified by restriction enzyme digestion of chromosomal DNA isolated from Tn5 mutants, as compared to the parental strain. Furthermore, mapping of Tn5 insertion sites can also be performed by whole-genome sequencing, and generated sequences are compared with the genomic sequence of F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 (https://biocyc.org/).

For Basic Protocol 4, mother mice rarely exhibit symptoms at doses that are lethal to 100% pups. The majority of preterm births will occur within 2–4 days post challenge and live pups will be born over days 4–7. Care should be taken to count pups quickly and often, in order as dead pups are removed by the mothers.

Time Considerations

General cloning

During the cloning process, DNA can be stored at −20°C until needed. Constructions of complementation and deletion constructs typically take 7 to 10 working days. Positive clones should be frozen at −80°C for future use.

Generation of deletion mutants

This procedure normally takes 15 working days, including all cloning procedures. For preparation of competent cells, F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 grows to single colonies 2–3 days after streaking from frozen stocks; once growth on plates the competent cells can be prepared the following day. Electroporated cells typically appear after 48–72 hours of incubation on plates.

Tn5 transposon mutagenesis

This procedure usually takes less than 10 days to finish, including preparation of competent cells and Tn5 transposome (2 days). After electroporation, colonies appear on plates by day 3. Depending on the number of laboratory personnel, transferring individual colonies into 96-well plates with toothpicks needs 2 to 4 days.

Mouse preterm birth model

The entire procedure takes a total of 30 days. Female and male mice are housed together for 72 hours for efficient breeding; male mice are then removed, and female mice remain in their cages. Sixteen to seventeen days after mating, the female mice are infected with F. nucleatum. Litters are born within 10 days of infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers DE026574 (to C.W.) and DE026758 (to H.T.-T).

Literature Cited

- Abed J, Emgard JE, Zamir G, Faroja M, Almogy G, Grenov A, … Bachrach G (2016). Fap2 Mediates Fusobacterium nucleatum Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Enrichment by Binding to Tumor-Expressed Gal-GalNAc. Cell Host Microbe, 20(2), 215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullman S, Pedamallu CS, Sicinska E, Clancy TE, Zhang X, Cai D, … Meyerson M (2017). Analysis of Fusobacterium persistence and antibiotic response in colorectal cancer. Science, 358(6369), 1443–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.aal5240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppenhagen-Glazer S, Sol A, Abed J, Naor R, Zhang X, Han YW, & Bachrach G (2015). Fap2 of Fusobacterium nucleatum is a galactose-inhibitable adhesin involved in coaggregation, cell adhesion, and preterm birth. Infect Immun, 83(3), 1104–1113. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02838-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaudo NJ, & Nesbitt WE (1997). Coaggregation of Candida albicans with oral Fusobacterium species. Oral Microbiol Immunol, 12(3), 168–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1997.tb00374.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YW (2015). Fusobacterium nucleatum: a commensal-turned pathogen. Curr Opin Microbiol, 23, 141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YW, Ikegami A, Chung P, Zhang L, & Deng CX (2007). Sonoporation is an efficient tool for intracellular fluorescent dextran delivery and one-step double-crossover mutant construction in Fusobacterium nucleatum. Appl Environ Microbiol, 73(11), 3677–3683. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00428-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YW, Redline RW, Li M, Yin L, Hill GB, & McCormick TS (2004). Fusobacterium nucleatum induces premature and term stillbirths in pregnant mice: implication of oral bacteria in preterm birth. Infect Immun, 72(4), 2272–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackins HC, & Barker HA (1951). Fermentative processes of the fusiform bacteria. J Bacteriol, 61(2), 101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A, Kaplan CW, He X, McHardy I, Shi W, & Lux R (2014). Characterization of aid1, a novel gene involved in Fusobacterium nucleatum interspecies interactions. Microb Ecol, 68(2), 379–387. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0400-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan CW, Lux R, Haake SK, & Shi W (2009). The Fusobacterium nucleatum outer membrane protein RadD is an arginine-inhibitable adhesin required for inter-species adherence and the structured architecture of multispecies biofilm. Mol Microbiol, 71(1), 35–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06503.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan CW, Ma X, Paranjpe A, Jewett A, Lux R, Kinder-Haake S, & Shi W (2010). Fusobacterium nucleatum outer membrane proteins Fap2 and RadD induce cell death in human lymphocytes. Infect Immun, 78(11), 4773–4778. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00567-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinder Haake S, Yoder S, & Gerardo SH (2006). Efficient gene transfer and targeted mutagenesis in Fusobacterium nucleatum. Plasmid, 55(1), 27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolenbrander PE, Andersen RN, & Moore LV (1989). Coaggregation of Fusobacterium nucleatum, Selenomonas flueggei, Selenomonas infelix, Selenomonas noxia, and Selenomonas sputigena with strains from 11 genera of oral bacteria. Infect Immun, 57(10), 3194–3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay TL, Ko J, Bilalis Y, & DiRienzo JM (1995). Mobile genetic elements of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Plasmid, 33(1), 15–25. doi: 10.1006/plas.1995.1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen G, Nisimov I, Helcer M, & Sela MN (2003). Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans serotype b lipopolysaccharide mediates coaggregation with Fusobacterium nucleatum. Infect Immun, 71(6), 3652–3656. doi: 10.1128/iai.71.6.3652-3656.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein MR, Wang X, Liu W, Hao Y, Cai G, & Han YW (2013). Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/beta-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe, 14(2), 195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Al Mamun AAM, Luong TT, Hu B, Gu J, Lee JH, … Ton-That H (2018). Forward Genetic Dissection of Biofilm Development by Fusobacterium nucleatum: Novel Functions of Cell Division Proteins FtsX and EnvC. MBio, 9(2). doi: 10.1128/mBio.00360-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Cen L, Kaplan C, Zhou X, Lux R, Shi W, & He X (2015). Cellular Components Mediating Coadherence of Candida albicans and Fusobacterium nucleatum. J Dent Res, 94(10), 1432–1438. doi: 10.1177/0022034515593706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]