Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is an autoimmune disease associated with increasing age. Typically, chondrocyte senescence is believed to serve an important role in the development and progression of OA. However, the specific mechanisms underlying chondrocyte senescence have not been fully addressed. The present study hypothesized that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling may represent a major regulator of chondrocyte senescence. In addition, the acetylated levels of p53 and sirtuin-1 (SIRT-1) were examined as putative markers for chondrocyte senescence, since activation of p53 is considered an important step in the regulation of senescence. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was activated using LiCl and inhibited using the Wnt signaling pathway inhibitor, dickkopf-1 (DKK1) in order to evaluate the role of this pathway in the development of OA. Senescent cells were detected using the senescence-associated indicator acidic senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal). The effects of p53 and p16 on chondrocyte senescence were assessed via activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling using Wnt-1. In addition, β-catenin was transfected into chondrocytes to induce activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Finally, a rabbit model of OA was used to assess whether the observed effects on the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and the induction of chondrocyte senescence were perpetuated. Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling increased the expression levels of SA-β-gal, p53, p16 and acetylated p53. Transfection of β-catenin in chondrocytes increased the expression levels of acetylated p53 and decreased the expression levels of SIRT-1, which in turn deacetylated p53 and modulated its activity. Finally, the role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was confirmed in the development of OA using a rabbit model with this condition. The present study suggested that activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway promoted chondrocyte senescence, through downregulation of SIRT-1 and increased the expression of acetylated p53.

Keywords: senescence, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, osteoarthritis, p53, sirtuin-1

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis and the main cause of disability in people ≤65 years old (1). While OA is affected by multiple factors, age is considered the single greatest risk factor for its development in susceptible joints (2). Chondrocytes are regarded as key players in OA pathology, since they are the only cell type present in articular cartilage. The degeneration of autophagy caused by aging results in the accumulation of senescent chondrocytes in articular cartilage (3). Senescent chondrocytes were observed near the osteoarthritic lesions, but not in intact cartilage from patients with OA or in normal donors (4). Senescent chondrocytes exhibit a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), characterized by the secretion of several inflammatory cytokines, growth factors and other soluble and insoluble factors (5). These senescent cells are generally detected using the senescence-associated indicator acidic senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal), which is a distinct marker of senescence for OA (6). Chondrocyte SASP is known to include the production of matrix-degrading proteases, including the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-3 and -13 enzymes (5). MMP-13 is believed to be central to the irreversible degradation of the cartilage type II collagen, which is the protein that constitutes the majority of the extracellular matrix (5). Recent studies have suggested that transplanted senescent cells induce an OA-like state in mice, whereas local removal of senescent cells can reduce the development of post-traumatic OA and create an environment that promotes regeneration (7,8). These results suggest an important role for chondrocyte senescence in the development and progression of OA. However, to the best of the authors' knowledge, the specific mechanisms underlying chondrocyte senescence have not been described to date.

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway serves an important role in joint embryogenesis and adult skeletal homeostasis (9,10). Previous studies demonstrated increased levels of β-catenin in degenerative or osteoarthritic cartilage (11,12). In chondrocytes, overexpression of β-catenin induced expression of matrix degradation enzymes (12). Moreover, activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway induced rapid gene expression of MMPs and other proteases, which resulted in the degradation of proteoglycan matrix (13). In β-catenin(ex3)Col2CreER mice, β-catenin degradation is selectively inhibited, which results in the increased expression levels of this protein in articular chondrocytes. This ablation resulted in an OA-like phenotype, including progressive loss of articular cartilage and osteophyte formation (14). Altogether, these studies demonstrated that Wnt/β-catenin signaling serves a significant role in the pathogenesis of OA. However, the effect of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in chondrocyte senescence has not been previously investigated, to the best of the author's knowledge.

β-catenin is a key protein in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. In the absence of Wnt proteins, β-catenin is phosphorylated by a degradation complex, including glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), adenomatous polyposis coli protein and Axin. The tagged β-catenin is ubiquitinated and subsequently degraded by the 26S proteasome. The Wnt protein binds to the co-receptor complex on the cell surface, leading to the activation of Dishevelled, a downstream protein of the receptor complex. This process inhibits the activity of GSK-3β resulting in the accumulation of β-catenin. The accumulated β-catenin is subsequently transferred to the nucleus, where it binds to transcription factors and alters the expression of several target genes (9,11). Most of these target genes, such as cyclin D1, are important in cell cycle regulation (15), which means that they may play an important role in regulating cell senescence, because the prominent feature of cell senescence is cell cycle arrest. Therefore, it may be hypothesized that Wnt/β-catenin signaling could regulate chondrocyte senescence.

In the present study, the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was experimentally modulated in order to assess its effect on chondrocyte senescence in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, the possible mechanisms underlying chondrocyte senescence were investigated.

Materials and methods

Animals

Rabbits and rats were obtained from Animal Center of Zhejiang University. A total of 12 male, 1-year old, New Zealand rabbits, weighing 2.0-2.5 kg, were used for the in vivo study. Rabbits were raised in a single cage with food and bottled water, at room temperature (24-26˚C), with 40-60% humidity and a 12 h light/dark cycle. Cultured chondrocytes from 4 male, four-week-old rabbits and 2 male, two-week-old rats under the same housing condition as aforementioned were used for the in vitro study. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Zhejiang University approved the present study.

Reagents

Wnt-1, LiCl, recombinant human interleukin (IL)-1β and collagenase II were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. Recombinant human Dickkopf (DKK1) was purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. Anti-β-catenin was purchased from EMD Millipore. Anti-MMP-13, anti-p16, anti-p53, anti-GAPDH, anti-acetylated p53 and anti-SIRT-1 were obtained from Abcam. Fetal bovine serum (FBS), Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), penicillin, streptomycin and 0.25% trypsin were purchased from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

Culture of rabbit/rat articular chondrocytes

Articular cartilage was isolated from the knee joint of both adult rabbits and rats under sterile conditions. Subsequently, 0.1% collagenase II was used to digest the cartilage at 37.8˚C for 4 h in order to cause detachment of the chondrocytes. Chondrocytes were transferred to 75 cm2 culture flasks at a density of 1x105 cells/cm2 in DMEM medium with 10% FBS and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin). The temperature of the incubator used for chondrocyte culture was set at 37.8˚C and the carbon dioxide content was 5%. The chondrocytes were passaged at a ratio of 1:3. Cell culture passages of the third or fourth generation were used for all in vitro experiments.

Treatment of rabbit chondrocytes with DKK1 and LiCl

The rabbit chondrocytes were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 2x105 cells/well and serum-starved overnight, then treated with 10 ng/ml IL-1β for 23 h in serum-free medium at 37.8˚C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Before adding IL-1β, chondrocytes were pre-treated with DKK1 (100 ng/ml) (16) or LiCl (20 mM) (17) for 1 h at 37.8˚C. Chondrocytes treated with PBS were used as controls. The cells were then harvested for reverse-transcription-quantitative (RT-qPCR) analysis and western blotting.

Treatment of rat chondrocytes with Wnt-1 and IL-1β

Rat chondrocytes were seeded at a density of 2x105 cells/well in six-well plates and serum-starved overnight. Subsequently, they were treated with 10 ng/ml Wnt-1(18) in serum-free medium for 72 h at 37.8˚C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Chondrocytes treated with PBS were used as controls. A part of the chondrocyte culture was used for SA-β-gal staining, whereas the remaining cells were harvested for western blotting. A second group of chondrocytes were treated with 10 ng/ml Wnt-1 for 72 h in the absence of serum and subsequently treated with 10 ng/ml IL-1β for 24 h at 37.8˚C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Chondrocytes treated with Wnt-1 for 72 h were then treated with PBS for 24 h at 37.8˚C in a 5% CO2 incubator were used as controls. The cells were finally used for RT-qPCR analysis.

SA-β-gal staining

Cells were stained with senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining kit (cat. no. 9860; CST Biological Reagents Co., Ltd.), according to manufacturer's protocol. The percentage of senescent cells was the total number of senescent cells divided by the total number of cells counted per microscope view, using a light microscope, magnification, x200.

β-catenin plasmid cell transfection

β-catenin plasmid construction was performed based on a previous study (19). The β-catenin gene was ligated into the pTagRFP eukaryotic expression vector (Evrogen JSC). 10 µg of DNA was used to transfect 70-80% confluent cells. Lipofectamine® 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to transfect the plasmid into the chondrocytes. The expression levels of β-catenin were assessed via fluorescence microscopy and western blot analysis. An empty vector was used as the control. 48 h after transfection, cells were collected or used for subsequent experimentation.

RT-qPCR

The cells harvested for RT-qPCR analysis were mentioned before. The rabbit cartilage was collected from the left femur (n=4) and frozen in-196˚C liquid nitrogen prior to use. The cartilage samples were then transferred to a 2 ml pre-filled bead mill tube (cat. no. 15-340-153; Thermo Fisher scientific, Inc.) containing 1 ml TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and then grinded using a Bead Mill 24 homogenizer (cat. no. 15-340-163; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Total RNA extraction was performed using the TRIzol® reagent. The SuperScript III reverse transcriptase cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis. The RT reaction contained 1 µl Oligo (dT)18 primer, 2 µg total RNA, 25 units of RNase inhibitor, 4 µl SuperScript III, 5X reaction buffer and 2 µl dNTPs (10 mmol/l). Sterile distilled water was added to create a total reaction volume of 20 µl. The RT reaction was incubated at 50˚C for 60 min. The iCycler apparatus system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and the SYBR-Green I (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) technology were used for RT-qPCR. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: i) Denaturation: 95˚C, 5 min on initial cycle; 30 sec on rest; ii) annealing: 55˚C, 30 sec; iii) extension: 72˚C, 60 sec; 5 min on the last cycle. A total of 40 PCR cycles were perfumed. The rabbit and rat primer sequences are shown in Table I and 18s rRNA was used as an internal control. The qPCR data were obtained using the DCq method. The formulas were as follows: N=100x2-(ΔCq targeted gene-ΔCq 18s rRNA) (20).

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Targeted genes | Sequence, 5' → 3' | Amplicon length, bp | Genbank accession |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rabbit MMP-13 | F: CAGATGGGCATATCCCTCTAAGAA | 88 | NM_001082037 |

| R: CCATGACCAAATCTACAGTCCTCAC | |||

| Rabbit p53 | F: GCCCATCCTCACCATCATCACACT | 82 | NM_001082404.1 |

| R: GCACACACTCGCACCTCAAAGC | |||

| Rabbit 18s rRNA | F: GACGGACCAGAGCGAAAGC | 119 | EU236696 |

| R: CGCCAGTCGGCATCGTTTATG | |||

| Rat MMP-3 | F: CTGGGCTATCCGAGGTCATG | 77 | NM_133523 |

| R: TGGACGGTTTCAGGGAGGC | |||

| Rat MMP-13 | F: CAACCCTGTTTACCTACCCACTTAT | 85 | NM_133530 |

| R: CTATGTCTGCCTTAGCTCCTGTC | |||

| Rat GAPDH | F: GAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG | 127 | NM_017008.4 |

| R: CATGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

F, forward; R, reverse; bp, base pair; MMR, matrix metalloproteinase; rRNA, ribosomal RNA.

Western blotting

Chondrocytes were initially washed with cold PBS and subsequently lysed in the RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing proteinase inhibitor for 30 min at 4˚C. The Bradford assay was used for detection of the protein concentration. 30 µg protein samples were loaded on 8-12% SDS-PAGE for protein separation. The proteins were transferred from the gels to PVDF membranes that were blocked for non-specific binding using 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were initially incubated overnight at 4˚C with the following antibodies: β-catenin (cat. no. 06-734; EMD Millipore; 1:1,000), MMP-13 (cat. no. ab39012; Abcam; 1:1,000), p16 (cat. no. ab51243; Abcam; 1:1,000), p53 (cat. no. ab131442; Abcam; 1:1,000), acetylated p53 (cat. no. 183544; Abcam; 1:1,000), SIRT-1 (cat. no. 189494; Abcam; 1:1,000), GAPDH (cat. no. 245355; Abcam; 1:1,000) and β-actin (cat. no. A5441; Sigma Aldrich; Merck KGaA; 1:1,000). On the following day, the membranes were incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (cat. no. G-21234; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; 1:2,000) at room temperature. The SuperSignal® West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (cat. no. 34075; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for visualization. The intensity of the protein bands was quantified using Image Lab 3.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

OA induction and rabbit treatment

Rabbits were divided into three groups (n=4 in each group). Anterior cruciate ligament transaction of bilateral knee joints was performed in each rabbit according to a previous study (19). The rabbits were housed under standard conditions for four weeks following the operation, and 0.3 ml DKK1, LiCl and vehicle (PBS) were injected respectively into the knee joint once every week. After 6 weeks of weekly intra-articular injections, the rabbits were anesthetized by intravenous injection of 3% sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg), then sacrificed by air embolism experimental specimen collection.

Histological evaluation

The femoral condyle of the right knee joint (n=4) was selected for tissue sectioning and was subsequently used for histological evaluation. The specimens were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 h at room temperature. Following removal of the excess tissue, the inner and outer femoral condyles were separated. Subsequently, the specimens were decalcified in 10% EDTA, which was replaced weekly for 2 months. The specimens were dehydrated using an ethanol gradient treatment, namely: 70% ethanol, 15 min; 90% ethanol, 15 min; 100% ethanol, 15 min; 100% ethanol, 15 min; 100% ethanol, 30 min; 100% ethanol, 45 min and infiltrated with xylene for, 20 min, twice and then 45 min, before being embedded in paraffin, all at room temperature. Paraffin specimens were cut into 5-µm thick sections for subsequent use. The sections were then stained with Safranin O and fast green for 5 min each at room temperature. The specimens were photographed using a light microscope at a magnification of x200. The Mankin score system was used to assess the severity of arthritis (21).

Immunohistochemistry

β-catenin protein expression in cartilage specimens was assessed by immunohistochemistry. The incubator temperature was set at 50-55˚C and 5-µm thick paraffin sections were fixed on slides coated with Aminopropyltriethoxysilane. The slides were removed from paraffin using xylol. Specimen rehydration was completed using descending graded alcohols and distilled water. The endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating the sections for 15 min in a methanol solution containing 1% H2O2. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was obtained by pressure cooking in a 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6) at 95˚C for 2 min and cooled. The slides were subsequently washed 3 times, for 5 min each, with PBST. Non-specific antibody-binding was blocked by incubating the samples for 10 min with 10% normal goat serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at room temperature. The slides were incubated overnight at 4˚C with primary anti-β-catenin antibody (cat. no. 06-734; EMD Millipore; 1:200) and washed with PBST again 3 times for 5 min each. The slides were incubated with EnVision secondary antibody (cat. no. LSAB2; Agilent Technologies, Inc.; 1:200) for 30 min at room temperature and subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase-linked complex (cat. no. LSAB2; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) for 30 min at room temperature. Chromogen (DAB) and 1% copper sulphate were used to enhance the color. Finally, the slides were counterstained in hematoxylin of Mayer for 10 min at room temperature and ascending graded alcohol was used for dehydration. Xylol was used for cleaning and the samples were placed on coverslips with Entellan. The slides were photographed using a light microscope at a x200 magnification.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated three times. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 16 (SPSS, Inc.). The significance between two groups was evaluated using unpaired Student's t-test. ANOVAs with the post hoc Tukey-Kramer honest significance tests were used for multi-group statistical analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

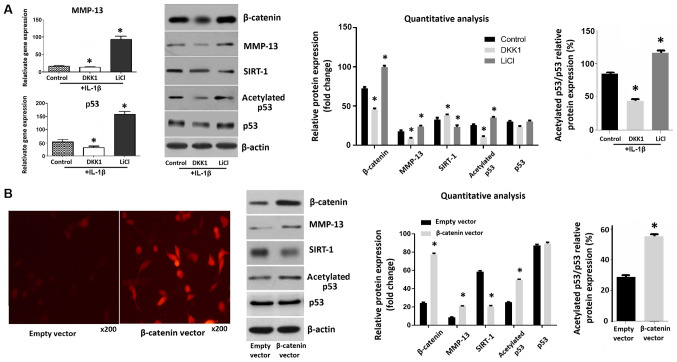

Effects of Wnt/β-catenin signaling on the expression levels of MMP-13, p53, acetylated p53 and SIRT-1 in chondrocytes

The expression levels of β-catenin in chondrocytes increased following treatment with LiCl, an activator of the Wnt pathway. Conversely, β-catenin expression decreased after treatment with DKK1, an inhibitor of the Wnt pathway. Moreover, the levels of MMP-13 and acetylated p53 were increased in LiCl-treated chondrocytes and decreased in DKK1-treated chondrocytes. There was no significant change in p53 protein level. The relative protein expression ratio of acetylated p53/total p53 in chondrocytes treated with LiCl was much higher. The activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling also decreased SIRT-1 expression (Fig. 1A). Fluorescence microscopy and western blotting confirmed that the expression of β-catenin in chondrocytes was increased 28 h following transfection of the cells with a β-catenin overexpression plasmids, compared with an empty vector control. In transfected cells, the expression levels of MMP-13 and acetylated p53 were significantly increased, whereas SIRT-1 levels were decreased by transfection of β-catenin into chondrocytes (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Effects of DKK1 and LiCl treatment on IL-1β-induced rabbit chondrocytes and chondrocytes transfected with β-catenin. (A) Cells were pre-treated with DKK1 and LiCl for 1 h and stimulated with IL-1β for 23 h, then harvested for RT-qPCR analysis and western blotting. (B) β-catenin expression was detected via immunofluorescence staining and western blotting. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 vs. control group. DKK1, dickkopf 1; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; IL, interleukin.

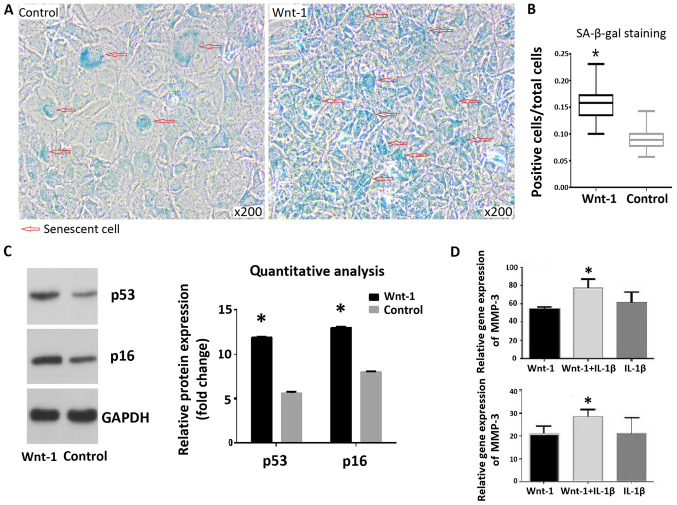

Wnt/β-catenin signaling induces chondrocyte senescence in OA

SA-β-gal staining indicated that treatment of chondrocytes with Wnt-1 resulted in a significantly higher senescence rate, compared with the control group (15.9 and 9.1%, respectively; Fig. 2A and B). The protein levels of p53 and p16 were increased following 72-h treatment with Wnt-1 (Fig. 2C). The addition of IL-1β following treatment with Wnt-1 for 72 h resulted in higher mRNA levels of MMP-3 and MMP-13, compared with the control group (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Wnt-1 induces senescence in chondrocytes. (A) SA-β-gal staining of the chrondocytes treated with Wnt-1 for 72 h and controls. (B) Quantitative analysis of the SA-β-gal staining indicated that chondrocytes treated with Wnt-1 for 72 h displayed a higher rate of senescence (15.9%), vs. the control group (9.1%). (C) The protein levels of p53 and p16 were increased following treatment with Wnt-1 for 72 h. (D) Cells were further treated with IL-1β following pre-treatment with Wnt-1 for 72 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 vs. control group. SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; IL, interleukin.

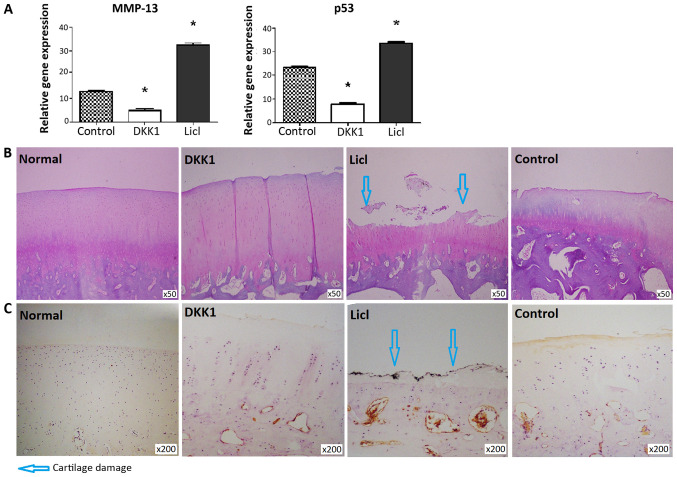

Gene expression, histological evaluation and immunohistochemical analysis of cartilage tissues

MMP-13 and p53 expression levels were decreased in cartilage from DKK1-treated knees and increased in the LiCl-treated group (Fig. 3A). DKK1-treated cartilage did not exhibit structural changes, while apparent cartilage damage was noted in cartilage injected with LiCl (Fig. 3B). Consistent with these findings, the DKK1-treated group exhibited a lower modified Mankin score than the LiCl-treated group (P<0.05; Table II). β-catenin expression was not detected in normal cartilage. β-catenin expression was much higher in cartilage from rabbits injected with LiCl, compared with cartilage tissues injected with DKK1 (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Gene expression, Safranin-O staining and immunohistochemical analysis of articular cartilage. (A) Cartilage from DKK1-treated knees indicated higher expression levels of MMP-13 and p53. (B) Safranin-O staining and (C) immunohistochemical results showed that LiCl-treated joints had severe cartilage damage and much higher expression levels of β-catenin, while DKK1-treated joints had intact cartilage and low expression levels of β-catenin. Normal cartilage tissues indicated no structural changes or alterations in the expression levels of β-catenin. Control animals received vehicle treatment (PBS). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. n=4. *P<0.05 vs. control group. DKK1, dickkopf 1; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase.

Table II.

Histological score of articular cartilage.

| Parameter | DKK1 | LiCl | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural changes | 0.43±0.53a | 2.67±0.50a | 1.0±0.50 |

| Cellular changes | 0.56±0.53a | 1.67±0.50a | 1.11±0.33 |

| Safranin staining | 0.71±0.49a | 1.56±0.73a | 1.11±0.60 |

| Total score | 1.86±1.07a | 5.89±1.17a | 3.22±1.30 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

aP<0.05 vs. control group. DKK1, dickkopf 1.

Discussion

IL-1β is a pivotal catabolic factor involved in the joint destruction observed during OA. IL-1β induces the expression of inflammatory mediators and MMPs in arthritis, leading to disruption of the balance between biosynthesis and degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) (22). Therefore, IL-1β has been widely used to mimic the OA microenvironment in vitro (23). The degradation of cartilage in OA is primarily mediated by MMPs, and the collagenase MMP-13 specifically targets collagen type II, which is the main component of the ECM (24). Therefore, in the present study, expression levels of MMP-13 were evaluated in order to assess the extent of OA.

The present findings confirmed the role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in the development of OA. Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling increased the expression levels of MMP-13 in LiCl-treated chondrocytes and chondrocytes transfected with β-catenin. Rabbit cartilage tissues that were treated with LiCl indicated higher MMP-13 expression levels and a higher modified Mankin score.

Previous studies indicated that Wnt/β-catenin signaling may be an antagonist of senescence. Firstly, Wnt signaling promoted proliferation by inhibiting senescence of epithelial cells and fibroblasts (25), while senescence cell impacted proliferation of the same cell populations (26). Secondly, elevated Wnt signaling is associated with the development of several types of cancer (27), whereas senescence acts as an important mechanism of tumor suppression (25). However, the present study supported the opposite conclusion. Indeed, activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling resulted in an increase in the expression of the senescence markers SA-β-gal, p53 and p16. Furthermore, in vivo experiments demonstrated that the expression levels of p53 were decreased in cartilage from DKK1-treated knees, and increased in LiCl-treated cartilage tissues, suggesting that the Wnt pathway promoted chondrocyte senescence both in vitro and in vivo. This result accords with a study by Liu et al (28), which suggested that continuous Wnt exposure triggered accelerated cellular senescence in vitro and in vivo. A previous study on nucleus pulposus cells suggested that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling promoted cellular senescence (17).

The present results suggested that the Wnt pathway promoted chondrocyte senescence. During senescence, p53 is activated and in certain cell types, induced expression of the p53 protein results in senescence (29-31). In addition, the histone deacetylase SIRT-1 is particularly important in this respect and its expression in senescent cells is downregulated (32). SIRT-1 which regulates p53 activity via deacetylation and inhibits the induction of senescence (33,34). The results of the present study indicated that the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway increased the expression and acetylation of p53 in chondrocytes. In LiCl-induced senescent chondrocytes, the expression levels of acetylated p53 were increased, whereas the opposite pattern of expression was noted in DKK1-treated chondrocytes. Transfection of β-catenin in chondrocytes increased the expression levels of acetylated p53. Furthermore, activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling following LiCl treatment or with β-catenin transfection decreased the expression levels of SIRT-1.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling promoted chondrocyte senescence in vivo. These effects were confirmed using an animal model of OA. The underlying mechanisms may involve downregulation of SIRT-1 and increased p53 acetylation levels. The findings suggest an important role for Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the regulation of chondrocyte senescence in OA and may provide new insight into the potential treatment of OA using targeted therapies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81301584).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

LW made substantial contributions to conception and design. WL was mainly responsible for cell and animal experiments. YX was a major contributor for the data analysis. WC contributed to the animal experiments as well as helping with the drafting and revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Zhejiang University approved the present study (approval no. 2018-015).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Garstang SV, Stitik TP. Osteoarthritis: Epidemiology, risk factors, and pathophysiology. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85 (11 Suppl):S2–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000245568.69434.1a. quiz S12-S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arden N, Nevitt MC. Osteoarthritis: Epidemiology. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20:3–25. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vinatier C, Domínguez E, Guicheux J, Caramés B. Role of the inflammation-autophagy-senescence integrative network in osteoarthritis. Front Physiol. 2018;25(706) doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erusalimsky JD, Kurz DJ. Cellular senescence in vivo: Its relevance in ageing and cardiovascular disease. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCulloch K, Litherland GJ, Rai TS. Cellular senescence in osteoarthritis pathology. Aging Cell. 2017;16:210–218. doi: 10.1111/acel.12562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price JS, Waters JG, Darrah C, Pennington C, Edwards DR, Donell ST, Clark IM. The role of chondrocyte senescence in osteoarthritis. Aging Cell. 2002;1:57–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2002.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu M, Bradley EW, Weivoda MM, Hwang SM, Pirtskhalava T, Decklever T, Curran GL, Ogrodnik M, Jurk D, Johnson KO, et al. Transplanted senescent cells induce an osteoarthritis-like condition in mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:780–785. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeon OH, Kim C, Laberge RM, Demaria M, Rathod S, Vasserot AP, Chung JW, Kim DH, Poon Y, David N, et al. Local clearance of senescent cells attenuates the development of post-traumatic osteoarthritis and creates a pro-regenerative environment. Nat Med. 2017;23:775–781. doi: 10.1038/nm.4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson ML, Kamel MA. The wnt signaling pathway and bone metabolism. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:376–382. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32816e06f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schett G, Zwerina J, David JP. The role of wnt proteins in arthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:473–480. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corr M. Wnt-beta-catenin signaling in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:550–556. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuasa T, Otani T, Koike T, Iwamoto M, Enomoto-Iwamoto M. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling stimulates matrix catabolic genes and activity in articular chondrocytes: Its possible role in joint degeneration. Lab Invest. 2008;88:264–274. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamamura Y, Otani T, Kanatani N, Koyama E, Kitagaki J, Komori T, Yamada Y, Costantini F, Wakisaka S, Pacifici M, et al. Developmental regulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signals is required for growth plate assembly, cartilage integrity, and endochondral ossification. J Biol Chem. 2005;13:19185–19195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu M, Tang D, Wu Q, Hao S, Chen M, Xie C, Rosier RN, O'Keefe RJ, Zuscik M, Chen D. Activation of beta-catenin signaling in articular chondrocytes leads to osteoarthritis-like phenotype in adult beta-catenin conditional activation mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:12–21. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;3:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregory CA, Singh H, Perry AS, Prockop DJ. The Wnt signaling inhibitor dickkopf-1 is required for reentry into the cell cycle of human adult stem cells from bone marrow. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28067–28078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiyama A, Sakai D, Risbud MV, Tanaka M, Arai F, Abe K, Mochida J. Enhancement of intervertebral disc cell senescence by WNT/β-catenin signaling-induced matrix metalloproteinase expression. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3036–3047. doi: 10.1002/art.27599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song P, Zheng JX, Liu JZ, Xu J, Wu LY, Liu C, Zhu Q, Wang Y. Effect of the Wnt1/β-catenin signalling pathway on human embryonic pulmonary fibroblasts. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:1030–1036. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li WJ, Tang LP, Xiong Y, Chen WP, Zhou XD, Ding QH, Wu LD. A possible mechanism in DHEA-mediated protection against osteoarthritis. Steroids. 2014;89:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mankin HJ, Dorfman H, Lippiello L, Zarins A. Biochemical and metabolic abnormalities in articular cartilage from osteo-arthritic human hips. II. Correlation of morphology with biochemical and metabolic data. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:523–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wojdasiewicz P, Poniatowski ŁA, Szukiewicz D. The role of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014(561459) doi: 10.1155/2014/561459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinecke LF, Grzanna MW, Au AY, Mochal CA, Rashmir-Raven A, Frondoza CG. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 production in chondrocytes by avocado soybean unsaponifiables and epigallocatechin gallate. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell PG, Magna HA, Reeves LM, Lopresti-Morrow LL, Yocum SA, Rosner PJ, Geoghegan KF, Hambor JE. Cloning, expression, and type II collagenolytic activity of matrix metalloproteinase-13 from human osteoarthritic cartilage. J Clin Invest. 1996;1:761–768. doi: 10.1172/JCI118475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye X, Zerlanko B, Kennedy A, Banumathy G, Zhang R, Adams PD. Downregulation of wnt signaling is a trigger for formation of facultative heterochromatin and onset of cell senescence in primary human cells. Mol Cell. 2007;27:183–196. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: Good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reya T, Clevers H. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 2005;14:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nature03319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu H, Fergusson MM, Castilho RM, Liu J, Cao L, Chen J, Malide D, Rovira II, Schimel D, Kuo CJ, et al. Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science. 2007;10:803–806. doi: 10.1126/science.1143578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferbeyre G, de Stanchina E, Lin AW, Querido E, McCurrach ME, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras and p53 cooperate to induce cellular senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3497–3508. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.10.3497-3508.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SW, Fang L, Igarashi M, Ouchi T, Lu KP, Aaronson SA. Sustained activation of Ras/Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade by the tumor suppressor p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;18:8302–8305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150024397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narita M, Nũnez S, Heard E, Narita M, Lin AW, Hearn SA, Spector DL, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell. 2003;13:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasaki T, Maier B, Bartke A, Scrable H. Progressive loss of SIRT1 with cell cycle withdrawal. Aging Cell. 2006;5:413–4122. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langley E, Pearson M, Faretta M, Bauer UM, Frye RA, Minucci S, Pelicci PG, Kouzarides T. Human SIR2 deacetylates p53 and antagonizes PML/p53-induced cellular senescence. EMBO J. 2002;15:2383–2396. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.10.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vigneron A, Vousden KH. p53, ROS and senescence in the control of aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:471–474. doi: 10.18632/aging.100189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.