Abstract

Background

Childhood cancer is a highly curable disease when timely diagnosis and appropriate therapy are provided. A negative impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic on access to care for children with cancer is likely but has not been evaluated.

METHODS

A 34‐item survey focusing on barriers to pediatric oncology management during the COVID‐19 pandemic was distributed to heads of pediatric oncology units within the Pediatric Oncology East and Mediterranean (POEM) collaborative group, from the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia. Responses were collected on April 11 through 22, 2020. Corresponding rates of proven COVID‐19 cases and deaths were retrieved from the World Health Organization database.

Results

In total, 34 centers from 19 countries participated. Almost all centers applied guidelines to optimize resource utilization and safety, including delaying off‐treatment visits, rotating and reducing staff, and implementing social distancing, hand hygiene measures, and personal protective equipment use. Essential treatments, including chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy, were delayed in 29% to 44% of centers, and 24% of centers restricted acceptance of new patients. Clinical care delivery was reported as negatively affected in 28% of centers. Greater than 70% of centers reported shortages in blood products, and 47% to 62% reported interruptions in surgery and radiation as well as medication shortages. However, bed availability was affected in <30% of centers, reflecting the low rates of COVID‐19 hospitalizations in the corresponding countries at the time of the survey.

Conclusions

Mechanisms to approach childhood cancer treatment delivery during crises need to be re‐evaluated, because treatment interruptions and delays are expected to affect patient outcomes in this otherwise largely curable disease.

Keywords: care delivery, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), middle‐income countries, pandemic, pediatric oncology

Short abstract

The response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has led to significant alterations in access to care for children with cancer. Interventions are needed to mitigate the effects on life‐threatening diseases requiring immediate and uninterrupted therapy, such as childhood cancer.

Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) has affected the world at a level never witnessed in recent history. 1 The outbreak was declared a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization (WHO) on January 30, 2020, and a global pandemic on March 11, 2020. 2 To control the spread that has overwhelmed health care systems, billions of people have since self‐isolated at home across the globe. Borders have been shut down, travel across and within countries has been restricted, and schools and nonessential businesses have been closed. The economic impact is unfolding. The whole world is struggling with shortages of basic items: intensive care unit beds, ventilators, personal protective equipment, disinfectants, even essential household and dietary commodities.

Hospitals have been the most affected, striving to maintain safety for their patients and staff, care for the sick, and comfort the families of the dead. Learning from situations in countries where the health care system quickly became overwhelmed with critically ill patients because of the pandemic, most hospitals in countries not yet affected massively by critical COVID‐19 infections have preemptively halted nonessential clinic visits, surgical procedures, and elective cases, in anticipation of rising numbers of COVID‐19 cases in their respective cities and countries. To optimize hospital capacity and resources while delivering safe and effective care to the sickest patients, hospitals have been reallocating staff, cancelling nonurgent procedures and therapies, and increasingly replacing face‐to‐face patient encounters and professional meetings with telemedicine. Although the response to the pandemic has been quickly adopted at a global level, the impact of the pandemic and its response on health care delivery in middle‐income and low‐income countries have not yet been fully reported.

Childhood cancer is a highly curable disease when timely, accurate diagnosis and appropriate therapy are provided. Children with cancer are particularly at risk of suffering the consequences of resource reallocations by having lifesaving treatments delayed, interrupted, or significantly modified. Scattered reports describe the clinical manifestations and outcomes of COVID‐19 in children, including in few patients with cancer who were receiving treatment. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 In view of the global response to the pandemic, there is concern regarding possible interruptions in the care of children with cancer during this process. Delays in diagnosis result in more advanced disease stage at presentation, reducing treatment response rates and worsening prognosis. Interruptions in treatment delivery or modifications of the intensive childhood cancer therapies to avoid hospital admissions are expected to result in treatment failure and increased rates of tumor relapse. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on childhood cancer care delivery, especially in middle‐income and low‐income countries where such data are lacking. 7 In this cross‐sectional study, we investigated the impact of the pandemic and its associated response on the care of children with cancer in the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia region.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

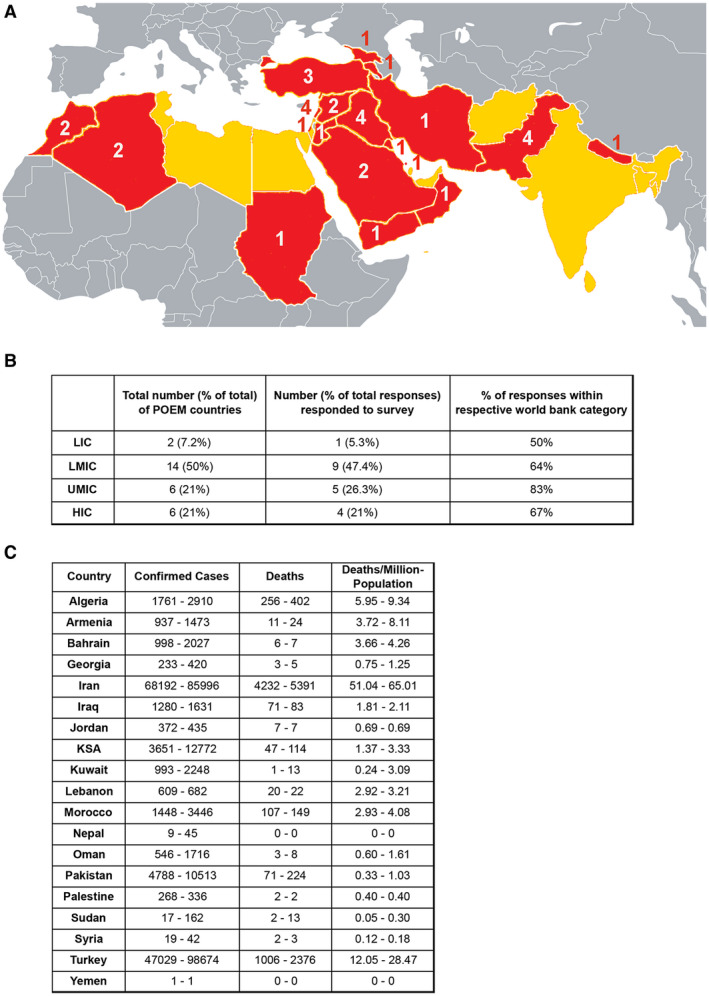

The Pediatric Oncology East and Mediterranean (POEM) group is a collaborative platform that was established in 2013 for health care professionals from over 80 pediatric oncology centers in 28 countries in the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia region (www.poemgroup.org). The goal of the group is to share experience, initiate cooperative trials, and establish common strategies to achieve the optimization of care for pediatric oncology patients. The countries in the POEM group are mostly within the World Bank lower middle‐income country (LMIC) category (14 countries; 50%) but also include upper middle‐income countries (UMICs) (6 countries; 21.4%), high‐income countries (HICs) (6 countries; 21.4%), and low‐income countries (LICs) (2 countries; 7.2%). Irrespective of economic classification, however, most countries share common barriers to cancer care delivery, and did so even before the COVID‐19 pandemic, including deficiencies in health care system infrastructure, workforce deficiencies, economic barriers, medication shortages, and patient abandonment, to various degrees within each country. 8

Survey Development

A 34‐item survey (see Supporting Materials), focusing on challenges in pediatric oncology management and barriers to care during the COVID‐19 pandemic, was designed with input from members of the executive committee of the POEM group to evaluate the impact of the pandemic response. Questions were distributed over 5 domains: 1) presence and duration of government‐imposed lockdown, 2) hospital administration policies affecting pediatric oncology care delivery, 3) patient‐related factors affecting care delivery, 4) availability of medical and ancillary staff, and 5) availability of therapeutic modalities and medical resources. The first draft of the questionnaire was piloted by 2 members of the group, and modifications made based on feedback. A second pilot was performed by the same 2 members, then the survey was finalized. Questions were formulated to be answered mostly as yes or no. Five free‐text questions were also included to elicit physicians' perspectives and descriptive responses regarding patient populations they believed were particularly affected, specific processes or solutions implemented by the hospital to deliver oncology care safely, and other comments in the different domains that the oncologists believed would be useful to share.

The questionnaire was then set up using online Microsoft forms (Microsoft Corporation) and was distributed by email (April 11‐16, 2020) to heads of the 82 pediatric oncology units that have members within the POEM group. 9 , 10 Participants were asked to complete the survey form by April 22, 2020. After the initial survey was sent out, survey nonresponders were emailed reminders every 2 days until the closing date of the study. Collected data were extracted into and analyzed within Excel (Microsoft Office; Microsoft Corporation).

COVID‐19 Epidemiologic Data

The numbers of reported COVID‐19 cases and deaths per country were extracted from the WHO database 11 to encompass the dates of the survey (April 11‐23, 2020). The numbers of reported deaths per capita were calculated using population data obtained from the United Nations' World Population Prospects (2019). 12

Analysis and Figures

Figures were constructed using PowerPoint and Excel software (Microsoft Corporation) and Adobe Photoshop CS6 software (Adobe Inc). Percentages were calculated using Excel. The Fisher exact test was used to compare answers across World Bank income groups. Free‐text responses were summarized within categories and tabulated.

Results

Study Population

Of the 82 centers in 28 countries that were invited to join the study, 34 centers (41%) from 19 countries (68%) participated and were included in the current analysis (Fig. 1A). All 4 World Bank economy stratification categories for POEM countries were adequately represented (Fig. 1B). In 8 countries, more than 1 center responded, whereas 1 center each responded in the remaining 11 countries. Although it is expected that responses from these centers are representative of the situation within the respective country, the generalizability of the responses to other centers within the country cannot be ascertained.

Figure 1.

(A) Membership in the Pediatric Oncology East and Mediterranean (POEM) collaborative group includes practitioners in the countries shown on the map in yellow and red, with red color depicting countries in which centers have completed the survey, and the corresponding number of participating centers. These countries are also listed alphabetically below, with those participating in the survey denoted by asterisks: Afghanistan, *Algeria, *Armenia, *Bahrain, Bangladesh, Egypt, *Georgia, India, *Iran, *Iraq, *Jordan, *Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, *Kuwait, *Lebanon, Libya, *Morocco, *Nepal, *Oman, *Pakistan, *Palestine, Qatar, Sri Lanka, *Sudan, *Syria, Tunis, *Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and *Yemen. (B) The number of POEM countries, stratified by World Bank Income category with corresponding stratification of respondents, and the percentage of respondents with respect to each category are shown. (C) The numbers of confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) cases, deaths, and deaths per million population, as reported by the World Health Organization, are shown for each country during the period of the survey. The first number in each cell corresponds to the date of April 11, 2020, and the second to the date of April 23, 2020. HIC indicates high‐income country; LIC, low‐income country; LMIC, lower middle‐income country; UMIC, upper middle‐income country.

Number of COVID‐19 Cases

At the start and end dates of the survey, the total number of confirmed COVID‐19 cases globally had reached 1,610,909 and 2,544,792, respectively, with the number of deaths at 99,690 and 175,694, respectively. 13 , 14 For the countries that participated, the numbers of confirmed COVID‐19 cases, COVID‐19–related deaths, and deaths per population are illustrated in Figure 1C for the period of the survey. By report, lockdown (partial or complete) was in effect in 18 of the 19 countries (95%). Lockdown had been in effect for at least 1 month in 16 countries and for 3 weeks in 2 countries. Notably, in some countries, lockdown was total in some areas and partial in others, varying by region or county (Algeria, Jordan, Turkey).

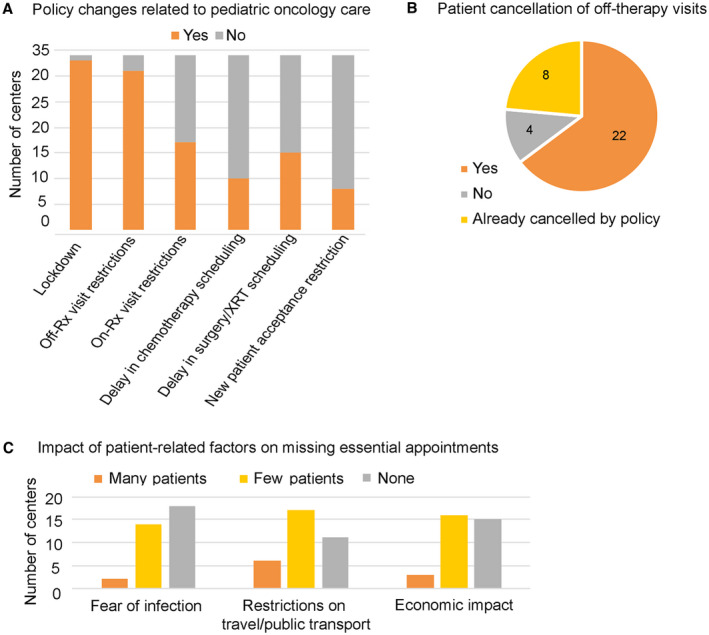

Implemented Changes by Hospital Administration

Figure 2A provides the data on travel restrictions, as reported by the centers, and hospital policy changes affecting pediatric oncology units. Restriction of off‐treatment visits was implemented in 31 centers (91%), on‐treatment visits were restricted to the absolutely essential in 17 centers (50%), delays in chemotherapy visits occurred in 10 centers (29%), delays in tumor surgery or radiation therapy visits occurred in 15 centers (44%), and restrictions on acceptance of new pediatric oncology patients were implemented in 8 centers (24%). When evaluating responses by World Bank income category (excluding LICs because only 1 center was included), delays in chemotherapy visits were reported by 31% of centers from LMICs (n = 4), 21% of centers in UMICs (n = 3), and 20% of centers in HICs (n = 1). Acceptance of new patients was restricted in 31% of LMIC centers (n = 4), 20% of HIC centers (n = 1), and 14% of UMIC centers (n = 2). Delays in surgery and radiation were reported by 60% of HIC centers (n = 3), 46% of LMIC centers (n = 6), and 28% of UMIC centers (n = 4). Statistical analysis across income groups did not yield evidence of a significant difference.

Figure 2.

(A) The number of centers reporting specific changes in national and hospital policies affecting pediatric oncology care, as detailed; B) the number of patient cancellations of surveillance (off‐treatment ) follow‐up visits; and C) the effect of fear, restrictions in transportation, and economic duress in patient‐driven cancellations of essential treatment visits are illustrated. On‐Rx indicates on medication; XRT, radiation therapy.

Patient‐Driven Behavior Affecting Care Delivery

Reports of patient‐driven factors affecting pediatric oncology treatment and related to the COVID‐19 pandemic and its associated response are summarized in Figure 2. These included patient cancellations of off‐therapy visits in 22 centers (65%), with an additional 8 centers reaffirming that visits were already cancelled by the hospital (24%) (Fig. 2B). Patients who refused to show up for essential visits, including chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy, for fear of contracting COVID‐19 were reported as many by 2 centers (6%) and few by 14 centers (41%). Patients who were unable to keep essential appointments because of restrictions on travel or public transport were reported as many by 6 centers (18%) and few by 17 centers (50%). Patients who were unable to keep appointed visits because of the economic impact of the pandemic and its associated response were many in 3 centers (9%) and few in 16 centers (47%) (Fig. 2C).

When asked whether specific patient subpopulations and/or diagnoses were affected, responses varied, and the comments are shown in Table 1. Answers included patient populations that needed to cross borders, lived in peripheral regions, or lived in areas of the country most heavily affected by the pandemic. Also affected were patients who required weekly chemotherapy, patients with newly diagnosed hematologic malignancies because of the need for urgent referral, which was delayed, and patients with solid tumors, including brain tumors, because of delays in surgery and radiation therapy. Some reported that all patients with newly diagnosed cancer were affected because of delays in diagnosis, whereas others highlighted the effects on patients who required stem cell transplantation. Two respondents commented that low‐risk patients were likely most affected, and another highlighted a lack of chemotherapy medications because of the lockdown. Multidisciplinary care interruptions were reported by 1 respondent, and another reported delays in the management of patients with febrile neutropenia and those requiring urgent supportive care measures, including issues with blood product supply.

Table 1.

Comments and Physician Opinions by Country Regarding Patient Subpopulations Whose Treatment Is Most Likely Affected by the Lockdown

| Country | Comment |

|---|---|

| Algeria | Patients with sarcomas and low‐grade gliomas who have weekly treatment regimen |

| Iran | Patients from northern provinces |

| Iraq | New cases of leukemia or lymphoma or unresponsive anemia |

| Iraq | Those who are living in the peripheral areas outside the city center |

| Jordan | Some patients who are off therapy and are worried about coming to the hospital |

| KSA | Solid tumor, lymphomas, leukemias, stem cell transplantation recipients |

| KSA | Patients requiring BMT were particularly affected |

| Kuwait | Patients who have brain tumors because of comorbidities after treatment are affected most |

| Lebanon | International patients who receive part of their therapy at our center, such as patients with retinoblastoma from Syria and Iraq |

| Lebanon | Low‐risk patients; some high‐risk patients who need chemotherapy that became unavailable because of the lockdown |

| Morocco | Patients with solid tumors (delays in surgery and/or radiation therapy) |

| Nepal | Mostly patients with hematologic malignancies are suffering more because they must wait to receive diagnosis and treatment |

| Pakistan | Newly diagnosed patients; further delay in initial diagnosis as public transport is stopped and diagnostic procedures are delayed; visits are very limited, and multidisciplinary tumor boards are also affected |

| Pakistan | Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma who live outside the city, whereas others live in the city during treatment |

| Pakistan | Pretransplantation visits are delayed because of family concern of infection |

| Sudan | Patients with febrile neutropenia and patients requiring supportive care (antibiotics, blood products, growth factors, etc) |

| Syria | Patients who need part of their treatment outside the country |

| Syria | Chemotherapy visits are delayed for 1 week for nonhigh–risk patients in complete remission |

| Turkey | Stem cell transplantation is suspended at our center because of blood product supplies, unless there is an urgent indication (leukemia, immunodeficiency) |

| Yemen | Because of the lockdown between cities in the north and south, some patients cannot travel to the referral center for treatment |

Abbreviations: BMT, bone marrow transplantation; KSA, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

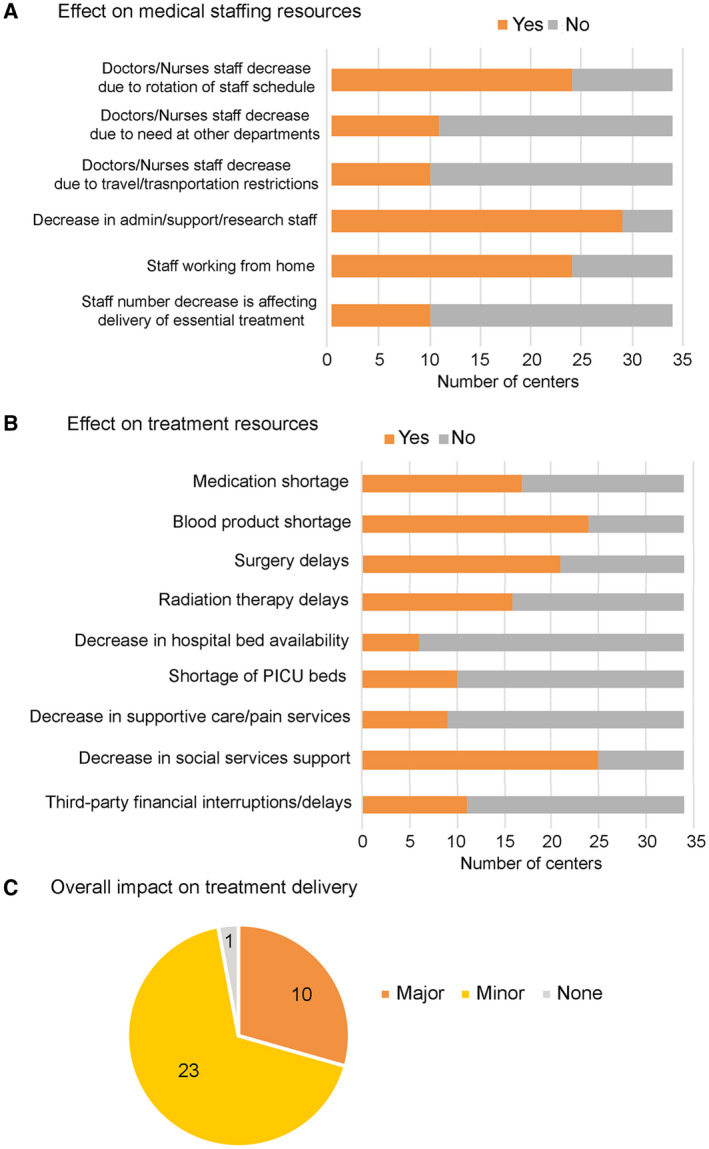

Medical and Ancillary Staff

Results of the impact of the pandemic on the health care workforce and medical resource availability are summarized in Figure 3A. The number of physicians and nurses in pediatric oncology units was decreased because of rotation of staff at 24 centers (70%), because of needs in other areas of the hospital at 11 centers (32%), and because of travel/transportation restrictions at 10 centers (29%). Most centers (n = 29; 85%) reported decreasing administrative and research staff to the absolute essential level, and staff was asked to work from home when possible in 24 centers (70%). The decrease in staff was believed to have affected the proper delivery of essential medical treatment at 10 centers (29%).

Figure 3.

The impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic is illustrated on (A) medical staffing resources, as detailed; (B) treatment resources, as detailed; and C) overall treatment delivery according to the number of centers. PICU indicates pediatric intensive care unit.

Treatment and Medical Resources

For treatment availability (Fig. 3B), medication shortage was reported in 17 centers (50%), and shortage of blood products was reported in 24 centers (70%). There were surgery delays in 21 centers (62%) and radiation therapy delays in 16 centers (47%). A decrease in bed availability because of hospital bed reallocation for the treatment of COVID‐19–affected patients was reported in 6 centers (18%), a decrease in intensive care unit bed availability was reported in 10 centers (29%), a decrease in the availability of pain control and supportive care services was reported in 9 centers (26%), and limitations in social services support were reported in 25 centers (74%). In addition, third‐party financial coverage interruptions and delayed financial approvals were noted by 11 centers (32%). Shortage of medication was reported by 80% of HIC centers (n = 4), 50% of UMIC centers (n = 7), and 23% of LMIC centers (n = 3). Bed shortages were reported by 40% of HIC centers (n = 2), 14% of UMIC centers (n = 2), and 8% of LMIC centers (n = 1). Shortages in supportive care and pain control services were reported in 40% of HIC centers (n = 2), 31% of LMIC centers (n = 4), and 7% of UMIC centers (n = 1). Statistical comparisons across income groups also did not yield evidence of a significant difference.

The overall impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic and its response on the delivery of curative medical and surgical care for pediatric oncology patients was subjectively described as major in 10 centers (29%) and minor in 23 centers (68%) (Fig. 3C). An impact of major magnitude was subjectively described in 1 center (20%) in an HIC, in 3 centers (21%) in UMICs, and in 4 centers (30%) in LIMCs. Of note, the 1 center from an LIC reported a subjectively high impact of the pandemic on all of the surveyed parameters, with the exception of third‐party financial coverage.

Other Effects and Comments

We also asked the physicians to comment on specific processes and solutions implemented at their centers to help deliver safe pediatric oncology care. Those responses are compiled in Table 2 and primarily included measures to implement social distancing, minimize potential exposure in clinical areas, promote phone and online visits, and measures for investigation of febrile illness. In addition, some implemented avoidance or delay of intensive chemotherapy. Others described changes in the shift schedule for health care workers, with measures to facilitate patient and staff transportation to the hospital and to mitigate shortages in blood product and medication supplies. Several centers highlighted cooperation among clinics and hospitals to transfer care based on need and home health visits as well as courier methods to deliver oral chemotherapy for home administration. Holding online multidisciplinary care meetings and teaching activities also was highlighted, as well as the use of social media for patient follow‐up and for the dissemination of clinic policy information.

Table 2.

Physician Descriptions of Specific Processes or Solutions That their Hospital Is Implementing to Help Deliver Oncology Care Safely

| Category | Processes Reported as Implemented |

|---|---|

| Social distancing in clinical areas |

|

| Screening measures |

|

| Use of PPE |

|

| Special precautions |

|

| Other hygienic interventions |

|

| Staffing |

|

| Administrative processes |

|

| Treatment modifications |

|

| Medications |

|

| Blood products |

|

| Communication |

|

| Transportation and housing |

|

| Collaboration among hospitals and clinics |

|

| Multidisciplinary care |

|

| Teaching and research |

|

Abbreviations: 6‐MP, mercaptopurine; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; BMT, bone marrow transplantation; CBC, complete blood count; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; MTX, methotrexate; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Additional miscellaneous comments included descriptions of stressors, additional limiting factors, and concerns for future patient care and outcome, as well as the identification of unanticipated positive byproducts of the pandemic response. These are summarized in Table 3 by country and type of comment. Examples of positive aspects reported included the use of online platforms and social media in reducing costs of care, providing school online learning to patients, and enhanced compliance with infection‐control and hand‐hygiene practices. Multidisciplinary tumor boards were continued through telemedicine in some centers. One hospital mentioned that psychology support was being made available for staff for the first time. In some areas, hospitals collaborated to share care for patients because of geographic constraints to travel, to avoid interruptions in essential patient care.

Table 3.

Free‐Text Comments by Physician Regarding Other Aspects Affected by the Pandemic

| Category | Physician Comments | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Drawbacks and difficulties | Limitations on travel have affected many patients who need treatment available only in other countries, such as stem cell transplantation and specialized therapy | Bahrain, Georgia |

| Several patients were stranded overseas or in another region of the country, leading to high stress levels by the primary and local teams | Iraq | |

| The decrease in health care professionals and psychosocial services led to less time available with a patient and increased stress on families and health care workers, especially with social distancing measures precluding common expressions of empathy | Kuwait | |

| Lack of affordable PPE | Algeria, Georgia, Lebanon, Nepal | |

| Lack of financial coverage for PCR tests for COVID‐19 | Algeria, Lebanon | |

| Expectation of major economic impact on families, as many have lost their wages, which may lead to treatment abandonment | Algeria, Lebanon, Pakistan | |

| New registration of cancer cases has dropped significantly, up to 60% in 1 center, reflecting lower rates of diagnosis | Pakistan | |

| Fears regarding the impact of prolonged closures on blood product supply and medication shortage | Turkey, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Nepal, Armenia, Pakistan, Yemen | |

| Fears regarding impact on fundraising activities, which are essential to provide care to patients in many centers | Lebanon, Armenia | |

| Expectations of increased relapse rates, and increased number of patients with delayed diagnosis and advanced disease | Kuwait | |

| Positive by‐products | Utility of social media in minimizing hospital visits and liaison with peripheral hospital to save time and costs on care delivery locally | Jordan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia |

| Compliance with infection control and hand hygiene practices, which are now implemented religiously across the hospital | Pakistan | |

| Psychological support sessions are being made available to physicians, which had not occurred previously | Pakistan | |

| Pediatric oncology patients benefitted from the school shift to online learning and are now able to attend classes virtually with their peers | Armenia | |

| Availability of radiology appointments at short notice because of the decreased demand from other hospital departments | Bahrain | |

| Future studies | Understand the impact on morbidity, mortality, and relapse rates | Morocco |

| Specific guidance by international consensus for managing pediatric oncology patients during similar crises | Nepal |

Abbreviations: COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Discussion

The COVID‐19 pandemic has necessitated a swift reallocation of health care resources and their utilization to optimize preparations for containment and management of this highly contagious and potentially fatal disease. Expanding the use of telemedicine and the strict prioritization of interventions in patients with noncommunicable diseases, especially cancer, have helped in certain contexts. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 However, the extent to which such measures could be applied in lower resource countries and those with health care system struggles is not clear. Also, the effect on LMICs that rely heavily on fundraising for childhood cancer care by nongovernmental organizations, which are now struggling with the effects of COVID‐19 on the global economy, needs special consideration. The current study sheds some light on the measures that have been taken by hospital administrations in countries across the specified region, with largely lower income economies, and highlights physicians' input regarding specific approaches, concerns, and challenges that can be used for future planning.

The survey response rate of 41% of centers, located in 68% of the countries, with representation of all economy country groups (see Fig. 1) provides a meaningful snapshot of the region. The results indicate that most centers applied policies and guidelines aligned with those recommended by international societies to optimize resource utilization and safety, consistent with other regional single‐center reports. 19

In almost all centers surveyed, off‐therapy surveillance visits were delayed, as has been recommended internationally as a measure for reducing the load on clinics and practicing safe decongestion and social distancing in clinic areas. 20 , 21 It is concerning to note that the scheduling of chemotherapy administration visits also was adversely affected in 29% of the centers, and tumor local‐control measures by surgery or radiation planning experienced delays in 44% of centers—an alarming rate that inevitably will lead to increased tumor relapses and treatment failures. Acceptance of new pediatric oncology patients was restricted in 24% of the centers—potentially leading to an increased load at other centers and raising the concern about patients who were not able to access potentially curative therapies. The reported blood product and medication shortages point to the potential disruption of lifesaving supportive care. The survey also confirmed an effect of families' fear of exposure to COVID‐19, barriers to travel (including halted public transport), and economic duress (because of the crisis and loss of daily wages) as well as interruptions in social services support, which adds to the impact caused by a compromised health care service.

Although most centers described changes in staffing to reduce exposure risk, in the surveyed physicians' opinions, this led to a negative impact on clinical care delivery in 28% of centers. The finding that the remaining 72% of respondents did not describe a negative impact on care delivery offers an opportunity to further study differences in planning between the 2 groups to better identify factors that enabled some centers, but not others, to effectively handle staff shortages without a major impact on pediatric cancer care delivery.

Unexpected positive aspects identified through the survey include resilience (maintaining multidisciplinary tumor boards, adopting telemedicine), innovation (psychology support for staff), and collaboration spirit (working together as a regional group as well as local collaborations among hospitals), which are helping hospitals and physicians navigate the changing landscape of health care delivery during this global crisis. Building on these findings, efforts should focus next on initiatives to apply lessons learned and be better prepared to meet future similar challenges.

Our study has several limitations. First, there are only a few surveyed centers within each country, thus generalizability of the results cannot be completely ascertained. The number of centers within each world income category was small, precluding meaningful statistical inferences regarding a possible differential effect of economic status on care delivery disruption. Also, the survey was filled by 1 recipient per hospital—the director of the pediatric cancer unit—therefore, data could not be further cross‐checked for independent validation. Despite these limitations, we believe that the results are meaningful in identifying both objective and subjective measures of the impact of the pandemic and its response on patients, physicians, and the health care system as they relate to pediatric cancer care delivery in countries of different income levels in the region.

At a global level, this pandemic has also brought pediatric oncology professionals together to develop better understanding and guidance on navigating the changing global conditions in health care delivery. Recently, the leadership of the principal childhood cancer organizations—the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP), SIOP Europe, the Children's Oncology Group, SIOP‐Pediatric Oncology in Developing Countries (PODC), the International Society of Pediatric Surgical Oncology (IPSO), the Pediatric Radiation Oncology Society (PROS), the International Children's Palliative Care Network (ICPCN), St Jude Global, and the WHO—jointly published general guidance for adapting childhood cancer services and cancer treatment during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 21 St Jude Global and SIOP have also created a Global COVID‐19 childhood cancer registry to learn more about the impact of the virus on patients with childhood cancer worldwide. 22

Continued collaborative efforts are needed to better understand the direct and indirect impact of COVID‐19. Health care system and resource‐appropriate modifications are needed to ensure sustained curative outcomes for children with cancer while maintaining their safety and that of their families and health care workers. Assessment of the pandemic regarding access to timely, accurate diagnosis, appropriate curative therapy, and lifesaving supportive care is essential to inform appropriate interventions at the health care system, social support, and advocacy levels during this crisis and to provide readiness for a potential similar future crisis.

Funding Support

Pediatric Oncology East and Mediterranean (POEM) group central office and activities are partially funded by American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC)/St Jude Global. Tezer Kutluk receives funding from the UK Research and Innovation Global Challenges Research Fund grant Research for Health in Conflict (R4HC‐MENA; ES/P010962/1).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

The authors made no disclosures.

Author Contributions

Raya Saab and Sima Jeha conceptualized the study and wrote the original draft of the article. Raya Saab and Anas Obeid performed the formal analysis. Raya Saab, Anas Obeid, Sima Jeha, Abdul‐Hakim Al‐Rawas, and Asim Belgaumi contributed to methodology planning. All authors contributed to data collection and article review and editing.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Saab R, Obeid A, Gachi F, Boudiaf H, Sargsyan L, Al-Saad K, Javakhadze T, Mehrvar A, Abbas SS, Abed Al‐Agele YS, Al‐Haddad S, Al Ani MH, Al-Sweedan S, Al Kofide A, Jastaniah W, Khalifa N, Bechara E, Baassiri M, Noun P, El-Houdzi J, Khattab M, Sagar Sharma K, Wali Y, Mushtaq N, Batool A, Faizan M, Raza MR, Najajreh M, Mohammed Abdallah MA, Sousan G, Ghanem KM, Kocak U, Kutluk T, Demir HA, Hodeish H, Muwakkit S, Belgaumi A, Al-Rawas A-H, Jeha S. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic on pediatric oncology care in the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia region: A report from the Pediatric Oncology East and Mediterranean (POEM) group. Cancer. 2020:126:4235‐4245. 10.1002/cncr.33075

Contributor Information

Raya Saab, Email: rs88@aub.edu.lb, Email: sima.jeha@stjude.org.

Sima Jeha, Email: sima.jeha@stjude.org.

References

- 1. Del Rio C, Malani PN. COVID‐19—new insights on a rapidly changing epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1339‐1340. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO announces COVID‐19 outbreak a pandemic. WHO; 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health‐topics/health‐emergencies/coronavirus‐covid‐19/news/news/2020/3/who‐announces‐covid‐19‐outbreak‐a‐pandemic [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hrusak O, Kalina T, Wolf J, et al. Flash survey on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 infections in paediatric patients on anticancer treatment. Eur J Cancer. 2020;132:11‐16. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2020.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rasmussen SA, Thompson LA. Coronavirus disease 2019 and children: what pediatric health care clinicians need to know. JAMA Pediatr. Published online April 3, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu W, Zhang Q, Chen J, et al. Detection of Covid‐19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1370‐1371. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2003717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lu X, Zhang L, Du H, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in children. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1663‐1665. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2005073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hopman J, Allegranzi B, Mehtar S. Managing COVID‐19 in low‐ and middle‐income countries. JAMA. 2020;323:1549‐1550. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Basbous M, Al‐Jadiry M, Belgaumi A, et al. Cancer care in the Middle East, North Africa, and West/Central Asia: a snapshot across five countries from the POEM network. Cancer Epidemiol. Published online June 2, 2020. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2020.10727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pediatric Oncology East and Mediterranean Group . The Pediatric Oncology East and Mediterranean (POEM) Group. Accessed April 27, 2020. www.poemgroup.org

- 10. Saab R, Belgaumi A, Muwakkit S, Obeid A, Galindo C, Jeha S, Al‐Rawas A. The Pediatric Oncology East and Mediterranean (POEM) group—a regional collaborative platform for childhood cancer healthcare professionals. Pediatr Hematol Oncol J. 2020;5:3‐6. doi:10.1016/j.phoj.2020.03.002 [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID‐2019) situation reports. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel‐coronavirus‐2019/situation‐reports

- 12. United Nations . World Population Prospects (2019). Data Booklet. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations; 2019. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_DataBooklet.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization (WHO) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) . Situation Report‐82. WHO; 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/situation‐reports/20200411‐sitrep‐82‐covid‐19.pdf?sfvrsn=74a5d15_2 [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization (WHO) . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Situation Report‐94. WHO; 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/situation‐reports/20200423‐sitrep‐94‐covid‐19.pdf?sfvrsn=b8304bf0_4 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Indini A, Aschele C, Cavanna L, et al. Reorganisation of medical oncology departments during the novel coronavirus disease‐19 pandemic: a nationwide Italian survey. Eur J Cancer. 2020;132:17‐23. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2020.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peng L, Zagorac S, Stebbing J. Managing patients with cancer in the COVID‐19 era. Eur J Cancer. 2020;132:5‐7. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2020.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nelson B. Covid‐19 is shattering US cancer care. BMJ. 2020;369:m1544. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Al‐Quteimat OM, Amer AM. The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on cancer patients. Am J Clin Oncol. 2020;43:452‐455. doi:10.1097/COC.0000000000000712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kattan C, Badreddine H, Rassy E, Kourie HR, Kattan J. The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the management of cancer patients in Lebanon: a single institutional experience. Future Oncol. 2020;16:1157‐1160. doi:10.2217/fon‐2020‐0313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bouffet E, Challinor J, Sullivan M, Biondi A, Rodriguez‐Galindo C, Pritchard‐Jones K. Early advice on managing children with cancer during the COVID‐19 pandemic and a call for sharing experiences. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28327. doi:10.1002/pbc.28327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sullivan M, Bouffet E, Rodriguez‐Galindo C, et al. The COVID‐19 pandemic: a rapid global response for children with cancer from SIOP, COG, SIOP‐E, SIOP‐PODC, IPSO, PROS, CCI, and St Jude Global. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28409. doi:10.1002/pbc.28409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. St Jude Global . The Global COVID‐19 Observatory and Resource Center for Childhood Cancer. St Jude Children's Research Hospital; 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://global.stjude.org/en‐us/global‐covid‐19‐observatory‐and‐resource‐center‐for‐childhood‐cancer.html [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material