Key points.

To gain insight on UK professionals' experiences and views of the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on psycho‐oncology activity, the British Psychosocial Oncology Society (BPOS) conducted an online survey of members and UK colleagues

Qualitative data from 94 respondents were analysed thematically. Key themes were summarised using the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) framework

Professionals reported severe disruptions in delivering clinical and supportive care to people affected by cancer and associated research activity. There were major concerns that the full impact of the pandemic is yet to be realised.

In both care and research settings, the pandemic has also been an impetus for positive changes in working practices, technology adoption, reducing process barriers and fostering collaborations which has to potential to be sustained.

To mitigate ongoing challenges, is it vital that cancer organisations work together to adapt and promote psycho‐oncology activity to maximise benefit for patients and professionals in the longer‐term.

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic has had a profound impact on every aspect of UK life in 2020. Health care systems have been radically reshaped at all levels to prepare for and manage coronavirus admissions whilst simultaneously trying to limit wider infection. As a consequence, cancer services have experienced major disruptions across every element of routine pathways; screening programmes have been suspended, treatments halted and face to face consultations severely restricted. 1 , 2 , 3 In addition, many cancer patients have also been advised to socially isolate at a time of increased psychological distress and need.

In response to the pandemic, The British Psychosocial Oncology Society (BPOS) reached out to the society membership and wider community to gain first hand perspectives on the impact of COVID‐19 on psycho‐oncology activity. Views were sought from professionals working across the field from clinical and third sector services and academic settings. We wanted to build a picture of how services, teams and individuals are adapting under the strains of the pandemic. Importantly, we sought to understand the challenges being faced as well as the positive responses and opportunities arising from the crisis.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

A cross‐sectional qualitative survey.

2.2. Materials

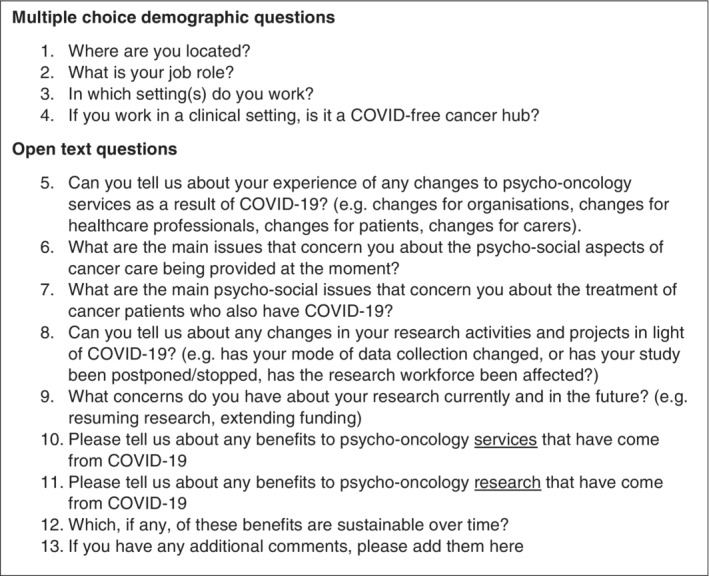

The survey was administered via QUALTRICS between May 19, 2020 and June 2, 2020 (during which time many lockdown measures were in place across the UK). The survey included brief demographic items and nine COVID‐19 focused questions with free text response boxes (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Survey questions

2.3. Participants

We aimed to recruit UK based professionals working in the field of psychosocial oncology including health professionals (from nursing, allied health, clinical/medical oncology, clinical psychology, psychiatry), third sector/charity organisations and academia.

2.4. Procedure

The survey invitation was disseminated via BPOS membership (N = 114) and wider networks (email and social media platforms). The information sheet included details on data anonymity and procedures for stopping participation or withdrawing data. Participants gave informed consent before continuing to survey items.

2.5. Ethics

Ethical approval was gained from Leeds Beckett University Psychology Department ethics committee on 19th May 2020 (REC reference 71 829).

2.6. Data analysis

Demographic information was analysed descriptively with frequencies and proportional data reported using SPSS Version 26. Data from the open questions were subject to thematic analysis. 4 Data were reviewed by all authors, and notes created about possible codes. Formal coding of data from each question was completed by two researchers; any discrepancies were discussed. Codes were extracted and drawn into sub‐themes and themes. These were organised around strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) framework 5 to facilitate interpretation. Strengths and weaknesses focus on exploring events that have already happened; opportunities and threats look to the future.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample and demographics

The survey was completed by 94 participants (see Table 1) based in a range of settings; clinical, n = 47 (50%), academic, n = 33 (35%), third sector n = 10 (11%), other n = 4 (4%).

TABLE 1.

Sample demographics

| Location | N = 94 (%) |

|---|---|

| North East | 0 |

| North West | 17 (18.1) |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 14 (14.9) |

| East Midlands | 2 (2.1) |

| West Midlands | 1(1.1) |

| East of England | 8 (8.5) |

| London | 18 (19.1) |

| South East | 16 (17.0) |

| South West | 7 (7.4) |

| Wales | 5 (5.3) |

| Northern Ireland | 2 (2.1) |

| Scotland | 4 (4.3) |

| Job role | |

|---|---|

| Clinical research nurse | 0 |

| Allied health professional | 6 (6.4) |

| Nurse | 9 (9.6) |

| Doctor | 7 (7.4) |

| Clinical Psychologist | 20 (21.3) |

| Health Psychologist | 2 (2.1) |

| Counselling Psychologist | 1 (1.1) |

| Psychotherapist | 2 (2.1) |

| Psychiatrist | 3 (3.2) |

| Counsellor | 2 (2.1) |

| Academic researcher | 29 (30.9) |

| Charity/Third sector/Non‐profit representative | 2 (2.1) |

| Other (please state) | 11 (11.7) |

| Setting | |

|---|---|

| Clinical | 47 (50.0) |

| Academic | 33 (35.1) |

| Charity/Third sector/Non‐profit | 10 (10.6) |

| Other | 4 (4.3) |

| COVID‐free cancer hub | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 18 (19.1) |

| No | 36 (38.3) |

| N/A | 38 (40.4) |

| Not reported | 2 (2.1) |

3.2. Survey findings

Key findings are described separately below for psycho‐oncology services and research activity. Table 2 provides a summary of results within the SWOT framework.

TABLE 2.

Summary of participant feedback on current psycho‐oncology practice and research within the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) framework

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice/service delivery |

|

|

|

|

| Research |

|

|

|

|

3.2.1. Feedback on psycho‐oncology services

Challenges: Weaknesses and threats

In response to the wider context of changes to cancer services (restrictions in treatment delivery and service reductions), the pandemic has forced a change in the delivery of psycho‐oncology services and clinical practices:

Patients have had treatment plans altered, e.g. chemo or radiotherapy instead of surgery, treatments have been delayed (particularly surgery), new diagnoses are reduced significantly in number

Respondents reported a reduction in patients referred to psycho‐oncology services. Where services have not been suspended or closed, patient contact is largely occurring remotely (telephone/video calls). This has brought technological challenges in service provision and concerns around how the quality of communication and support compares to standard face to face delivery:

All psychological care has moved to either telephone or video calls which has a particular impact for newly referred patients as this has led to longer waiting times and the usual care provided is not effective as normal. Using telephone/video calls to complete assessments is particularly difficult as there is no existing relationship so makes it harder to form a therapeutic alliance

Significant concerns were raised around the ability of staff to effectively deliver the same standard of care via remote methods and what impact this approach was having:

the effective removal of face‐face contact from every interaction will have unmapped and unknown effects ‐ affect moderation, trust, decision‐making, adherence ‐ may make things better or worse ‐ but I am worried it will be accepted as equivalent for expediency

Lack of face to face monitoring and social isolation has created anxiety and distress amongst some cancer communities potentially increasing the need for psychological support:

at time of heightened anxiety and risk of psycho‐social morbidity, there will be less people at all of the levels needed to provide support, advice and care

In relation to the care of cancer patients with COVID‐19, unique challenges were raised with the psychological burden of treatment options being withdrawn or restricted. Professionals are managing significant pressures around the “increased emotional content of work” created from working remotely, supporting colleagues and being “disconnected” in some cases from clinical teams.

There was clear concern that due to the current prioritisation of resources and services, psychosocial needs of people affected by cancer are currently not being adequately met and that an influx of patients in need was on the horizon:

I worry that when things return to normal we will have an avalanche of demand

Fears were expressed that important progress made in psycho‐oncology care had been halted whilst services catch‐up with the backlog and influx of patients:

the focus on safety, capacity and treatment is obviously primary, but sucks out all the air and everything on wellbeing, QOL and personalised care won't get another look for a long time

Positives: Strengths and opportunities

Despite these weaknesses and threats, the pandemic has been an impetus for change, spring‐boarding access to technology, facilitating the quick establishment of options for remote patient contact:

Speed of service change ‐ I do think we will think more creatively about service delivery and be faster at implementing this going forward

This rapid shift has created opportunities to develop, improve and refine remote services enabling increased accessibility for some patients who are unable to travel (distance, too unwell, anxious):

I think remote working for many patients is helpful. We can often get referrals for patients who live a considerable distance from the hospital, therefore being able to work remotely is a real advantage.

Ability to work remotely will be useful with some patients, particularly those in palliative care with whom we traditionally wouldn't have completed home visits once they were unable to come in to see us.

The change to remote working has resulted in many staff working from home, presenting an opportunity to be more flexible with working practices in the future.

Permission by NHS Trust to work from home is welcome, especially for cancer counsellors who work part‐time and otherwise spend a disproportionate time commuting, and cost

The skills and value of psycho‐oncology professionals have received increased recognition (including through the provision of support for health professionals) allowing for new collaborations within and between different organisations.

I think with engaging/leading on staff support we have shown the range of skills psycho‐oncology clinicians have within the hospital

Significant new networks of professional contacts evolving quickly in joint enterprises; hopefully will be beneficial in future

3.2.2. Feedback on psycho‐oncology research activity

Challenges: Weaknesses and threats

At an organisational level, the pandemic has had a major impact on psycho‐oncology research delivery as many studies/trials have been stopped or suspended and the clinical research workforce has been directed to prioritise COVID‐19 research. Where feasible, research studies have been adapted to take account of the barriers the pandemic has presented, whilst viewed negatively by some, it has also led to new research questions being explored.

With institutions closing buildings housing non‐essential services, large numbers of staff have quickly moved to working remotely, changing how they work and engage with colleagues and collaborators:

Team working remotely from home, access to some IT systems not possible, new challenges in maintaining morale and motivation and managing stress/expectations for colleagues juggling work‐life‐carer responsibilities

Respondents were concerned that once lockdown is eased, some ongoing studies may not restart, meaning they will not achieve the planned sample size. Others questioned the sustainability of delivering research as new cancer pathways have been implemented that limit direct access to potential participants and clinical staff. At the same time, funding calls have been pulled or suspended with the result that both individuals and research teams are increasingly anxious about what the future holds:

Many research grant calls have been pulled or postponed (particularly from Charities). So it feels that sustaining the workforce is challenging moving forward, staff are very anxious about this

Those employed by academic organisations were concerned about the potential financial impact of the pandemic on this sector and what this will mean for job security, particularly those on fixed term contracts:

Universities facing massive financial strain‐ not currently clear what the implications will be for jobs and research resources in coming months/years

Positives: Strengths and opportunities

Respondents described a number of positive ways in which research activity had been maintained and adapted in response to COVID‐19. At an organisational level, ethical and governance administration had been responsive with procedures being sped up and streamlined:

Ethics and other governance processes have been able to move incredibly swiftly

The push to remote working has led to a range of potential benefits for flexibility and productivity in some cases and demonstrated that many areas of research activity were able to continue:

I think there is great trust in the research community that people can be left to get on with their work and deliver it effectively and responsibly

And for some, there was potentially “no turning back” now these practices were becoming mainstream. Successful examples of studies being effectively adapted to take advantage of online/technologically supported methods were described:

The tech‐saviness of more people so research can be conducted with a wider spread of participants

In some instances, the pandemic has created an environment which increases the relevance of certain research areas (eg, remote patient monitoring) which could facilitate opportunities and future impact. Respondents also described the formation of new research questions and collaborations with clinical colleagues which may foster future research developments. The shift to virtual conferences and research meetings is creating the potential for wider participation and engagement across academic communities.

4. CONCLUSIONS AND KEY MESSAGES

Survey respondents shared important insights on the impact of COVID‐19 on psycho‐oncology activity.

We recognise our findings are limited by the sample size and under‐representation from some professional groups. However the feedback clearly highlights the key issues that have been faced in preceding months as well as future concerns and opportunities.

It is apparent that psycho‐oncology professionals across the field have dealt with significant challenges during the pandemic. With the full magnitude of the impact of COVID‐19 yet to be realised in cancer care, more hurdles are undoubtedly on the horizon. Importantly, the pandemic has in many instances created a platform on which the skills and knowledge base of many psycho‐oncology specialists have been showcased. Services, teams and individuals have also adapted creatively and flexibly. Technology has been embraced in many practice and research contexts and is supporting new ways of working. However, there is much to learn about how effective and sustainable these approaches will be in the longer term for both professionals and those living with a beyond a cancer diagnosis.

A period of reflection is now needed to allow professionals across all areas to take stock of progress and achievements and consider how best to face future challenges. There is scope to harness opportunities to shape psycho‐oncology care and for practitioners and researchers to work together productively. It is vital that BPOS and other cancer focussed professional organisations and societies within the UK and globally work collaboratively to maintain the profile of psycho‐oncology, mitigate challenges and make the most of opportunities for the benefit of patients and those who care for them. A number of professional organisations in the UK have responded by generating coronavirus focussed guidance and information. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 With the response to COVID‐19 constantly evolving, further studies are warranted to understand the practical value of these guidance materials and determine the longer‐term impact of the pandemic on psycho‐oncology in the coming months and years.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was designed and conducted by members of the British Psychosocial Oncology Society Executive Committee. We thank Leeds Beckett University Psychology Department ethics committee for reviewing the proposal. We would also like to acknowledge the support provided by wider colleagues, particularly the United Kingdom Oncology Nursing Society and the British Psychological Society Faculty for Oncology and Palliative Care who circulated the survey invite. We are extremely grateful for time survey respondents took to share their experiences and opinions.

Archer S, Holch P, Armes J, et al. “No turning back” Psycho‐oncology in the time of COVID‐19: Insights from a survey of UK professionals. Psycho‐Oncology. 2020;29:1430–1435. 10.1002/pon.5486

On behalf of the British Psychosocial Oncology Society Executive Committee

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. El‐Shakankery KH, Kefas J, Crusz SM. Caring for our cancer patients in the wake of COVID‐19. Br J Cancer. 2020;123:3‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones D, Neal RD, Duffy SRG, Scott SE, Whitaker KL, Brain K. Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the symptomatic diagnosis of cancer: the view from primary care. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):748‐750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spicer J, Chamberlain C, Papa S. Provision of cancer care during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(6):329‐331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77‐101. [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Wijngaarden JD, Scholten GR, van Wijk KP. Strategic analysis for health care organizations: the suitability of the SWOT‐analysis. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2012;27(1):34‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. British Psychological Society . Coronavirus resources for professionals. https://www.bps.org.uk/coronavirus-resources/professional. 2020. Accessed July 6, 2020.

- 7. British Medical Association . COVID‐19: video consultations and homeworking. https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/covid-19/adapting-to-covid/covid-19-video-consultations-and-homeworking. 2020. Accessed July 6, 2020.

- 8. British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy . Working online resources: Resources for members. https://www.bacp.co.uk/news/news-from-bacp/coronavirus/working-online-resources/. 2020. Accessed July 6, 2020.

- 9. United Kingdom Oncology Nursing Society . Resources for tackling COVID‐19 in Oncology. https://ukons.org/news-events/resources-for-tacking-covid-19-in-oncology/. 2020. Accessed July 6, 2020.

- 10. Macmillan Cancer Support . Coronavirus Health Professionals. https://www.macmillan.org.uk/coronavirus/healthcare-professionals 2020. Accessed July 6, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.