Abstract

Objective

To explore the prevalence of depressive symptoms among women in late pregnancy, and assess mediating effect of self-efficacy in the association between family functions and the antenatal depressive symptoms.

Design

Community-based, cross-sectional study was conducted among women during the third trimester of pregnancy.

Setting

This study was conducted among pregnant women registered at community health service centres of urban Hengyang City, China from July to October 2019.

Participants

813 people were selected from 14 communities by multi-staged cluster random sampling method.

Main outcome measures

The Family Adaptation Partnership Growth Affection and Resolve Index, the General Self-efficacy Scale and Patient Health Questionnaire were used to access family functions, self-efficacy and antenatal depression symptoms, respectively.

Results

In this study, 9.2% pregnant women reported the symptoms of antenatal depression (95 CI% 7.2% to 11.2%). After adjustment, the results showed that severe family dysfunction (adjusted OR, AOR 3.67; 95% CI 1.88 to 7.14) and low level of self-efficacy (AOR 3.16; 95% CI 1.37 to 7.27) were associated with antenatal depressive symptoms (p<0.05). Furthermore, self-efficacy level partially mediated the association between family functions and antenatal depressive symptoms(β=−0.05, 95% CI −0.07 to −0.03, p<0.05) and the mediating effect accounted for 17.09% of the total effect.

Conclusions

This study reported 9.2% positive rates of antenatal depression symptoms among women in the third trimester of pregnancy in Hengyang city, China. The mediating effect of self-efficacy on the association between family functions and antenatal depression symptoms among women in the third trimester of pregnancy was found in this study, which provide a theoretical basis to maternal and child health personnel to identify high-risk pregnant women and take targeted intervention for them.

Keywords: obstetrics, depression & mood disorders, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study aimed to assess the prevalence of antenatal depressive symptoms among women in the third trimester of pregnancy, and completely evaluate the moderating effect of self-efficacy in the association between family functions and the antenatal depressive symptoms. This study provides evidence and support for identifying high-risk pregnant women with emotional problems in order to take early intervention measures.

In this study, the selection of sample is representative, pregnant women were enrolled from community health service centres, with low no-response rate and recall bias.

The cross-sectional study limited the ability to make causal inferences. Future studies should investigate the causal associations among family functions, self-efficacy and antenatal depression symptoms with longitudinal designs.

Instruction

Depression was the most common mood disorders in the general population, the prevalence ranged from 5% to 10%, which of women was about twice as high as that of men, and childbearing age was the peak of the disease.1 Furthermore, depression was one of the most common complications during the pregnancy.2 The meta-analyses of perinatal depression reported the prevalence was 6%–13%.3 The prevalence of antenatal depression was significantly higher than any other time,4 especially in the third trimester of pregnancy.5 Also note that, the prevalence of depression in less developed countries is higher than that in low-income and middle-income countries, vary from 19% to 25% during the pregnancy.6–8 Depression not only directly affected the physical and mental health of the pregnant women,9 but also indirectly did harm to the health of the next generation.10 During the pregnancy, depression symptoms have been associated with self-harm, suicidal-ideation, placental abruption, preterm delivery, they also might lead to low birth weight, low Adaptation Partnership Growth Affection and Resolve Index (APGAR) score, maladaptive emotional and behavioural development of offsprings.11 12 From what has been discussed above, antenatal depression has become a global public health issue,13 particular attention needs to be paid to antenatal depression among women in late pregnancy in low-income and middle-income countries. However, many studies on maternal depression mainly focused on postnatal depression and there is less data available on antenatal depression in China.

Family is an important emotional support sources, family functions play an important role in human life and social development. For pregnant women, family functions refer to the effectiveness of family members’ emotional connection, family rules, family communication and coping with external events in the family system during the pregnancy,14 including family adaptation, family partnership, family growth, family affection, family resolve. Generally speaking, in well-functioning families, pregnant women can get support and guidance from other members when they encounter difficulties and crises, and obtain material and emotional satisfaction. On the contrary, family can also be a source of conflict and stress, a study proposed family members’ expectations on the newborn were usually manifested through excessive attention and care to pregnant women, which might increase negative effects and stress to the pregnant women.15 It is not clear whether there is a factor that influences the association between family functions and antenatal depression symptoms, leading two these two different effects. Self-efficacy is one of the possible factors of this contradictory result. A study suggested self-efficacy was negatively correlated with depression, anxiety and other adverse emotional problems.16 For pregnant women, self-efficacy can be expressed as the conviction that women can successfully execute behaviours required to produce a desired outcome during pregnancy.17 Self-efficacy may affect or determine pregnant women’s thinking mode, emotional response mode and the choice of behaviour, which might be self-aiding or self-hindering.18 The mediating effect of self-efficacy in the association between family functions and depressive symptoms has not been proven during pregnancy. Based on the above theory, this study aims to explore the prevalence of antenatal depressive symptoms among pregnant women during their third trimester, and completely assess the association between family functions, self-efficacy and antenatal depressive symptoms, in hopes of providing medical personnel with some useful information that can aid early mental interventions on high-risk pregnant women.

Methods

Participants and procedure

This cross-sectional study was conducted in urban communities of Hengyang city, Hunan Province, China from July to October 2019. A total of 813 eligible individuals from 14 communities were involved by multi-staged cluster random sampling method. The specific sampling steps are as follows: there were five districts in urban Hengyang, each street was numbered, randomly selected a street from each district. Then, proportional sampling was carried out at a proportion of 1/3, 14 communities were included. The sample size calculation formula for cross-sectional studies was used to calculate the minimum theoretical sample size for this study. According to the prevalence of antenatal depression symptoms, which have been reported in a previous study,19 d=0.1, α=0.05. Finally, 812 people were required in order for the participants to represent the population. All pregnant women who were registered in community health service centres and meeting the inclusion criteria were potential subjects in this study (n=819). The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: (1) women in the third trimester of pregnancy; (2) pregnant women over 16 years old; (3) pregnant women who had local household registration or migrant people who lived in urban of Hengyang city for more than 6 months. The exclusion criterion: (1) pregnant women with cognitive disorders, severe mental illnesses or other serious diseases cannot fill out the questionnaire by themselves and (2) pregnant women who refused to participate in the study. Through the information provided by the community maternal management system, we contacted each potential recruiter and made an appointment for the interview time. Accompanied by the community maternal and child health personnel, trained investigators handed out questionnaires by calling at the house and collected them on the spot. Eight hundred and thirteen participants were given written information about the purpose of this study and signed a written informed consent. Participants were expected to filled out structured questionnaires by themselves. In addition, the trained research assistants from Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University would always available to provide assistance and ensure independent responding. Although we strongly encouraged all potential recruiters to participate in our research, there were still six people were excluded, because of refusals to respond and failure to contact. The response rate of questionnaires was 99.3% (813/819).

Patient and public involvement

We did not involve patients or the public in our work. Each participant received a report describing the results of our study.

Measures

The questionnaire included four sections: demographic characteristics, the revised Chinese version of Family APGAR, the General Self-efficacy Scale (GSES) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Demographic characteristics included marital status (stable, unstable), occupation (employed, unemployed), education level (senior school and below, college/university degree and above). In this study, being married was defined as being in a stable marriage. Unstable marriage including unmarried, divorce, widowhood.

Assessment tools for family functions

Family APGAR was originally developed by Smilkstein,20 which was a simple self-assessment tool for evaluating the subjective satisfaction of family functions. Five items were used to evaluate five different aspects of family function: family adaptation, family partnership, family growth, family affection and family resolve. Family APGAR index was answered on a 3-point Likert scale from ‘often’ (two points) to ‘rarely’ (zero point). The total score was 0–10 points, good family function has a high family APGAR index between 7 and 10, family dysfunction has a moderate family APGAR index between 4 and 6, and severe family dysfunction has a low family APGAR index less than 3. Family APGAR index has been widely used and has good reliability and validity.21 In this study, the Cronbach’s α is 0.876.

Assessment tools for self-efficacy

The GSES was publicised in 1981 by Ralf Schwarzer and translated into Chinese by Zhang in 1995,22 23 which was used to evaluate the self-efficacy level of pregnant women. There are 10 items, which were measured using a 4-point Likert scale from ‘absolutely wrong’ (1 point) to ‘absolutely right’ (4 points). According to the norm of using the GSES, the method of calculating the final self-efficacy score was to divide the total score by 10. The final score ranged from 1 to 4, based on partition criterion for scale, self-efficacy level could be divided into three levels: high (3.1–4), medium (2.1–3) and low (1–2).24 The Chinese version of GSES has good reliability and validity which has been validated by Zhang et al.23 The Cronbach’ α of this scale was 0.898 in this study.

Assessment tools for antenatal depression symptoms

PHQ-9 was used to assess the subjective depressive symptoms of pregnant women during the last 2 weeks in this study. PHQ-9 was revised according to the diagnostic criteria of DSM-Ⅳ,25 which was widely known as simple self-management tools and used in clinical and investigation research.26 PHQ-9 consisted of nine items, each item described a symptom of depression: (1) loss of pleasure; (2) be down in spirits or hopelessness; (3) sleep disorder; (4) lack of energy; (5) diet disorder; (6) self-deprecation; (7) trouble concentrating; (8) changes in physical behaviour and (9) thoughts of self-harm. Of this scale, subjects rated the frequency of each symptom using a scale of descriptors: not at all, sometimes, more than half the days, nearly every day (scored from 0 to 3). The total score is 27 points, usually 10 points were used as the positive critical value.27 The Chinese version of the PHQ-9 has been validated by Yu et al.28The Cronbach’ α of this scale was 0.773 in the study.

Statistical analysis

The method of double input with EpiData V.3.1 was adopted. SPSS V.19.0 software were used for statistical analysis. Categorical variables are expressed as n(%), the χ2 test was applied for comparing the different characteristics between participants in two groups (depressive symptoms vs no depressive symptoms). The crude ORs, adjusted ORs (AOR) and 95% CI were reported by multivariate binary logistic regression models. The adjusted variables including marital status, occupation and education. A structural equation model was established by AMOS V.24.0. Based on the assumption in this study, family APGAR index as predictors, self-efficacy as mediator and antenatal depression symptoms as outcome. The total effect of family functions on antenatal depression symptoms was composed of a direct effect of the family functions on the antenatal depression symptoms and an indirect effect of family functions on antenatal depression symptoms through a proposed mediator. Bootstrapping is a non-parametric resampling method that generates an empirical approximation of the sampling distribution of a statistic from the available data and constructs CIs for the indirect effect.29 Bootstrap method was used to examine the effect of self-efficacy in explaining the association among family functions and antenatal depression symptoms.30 The CI was set at 95%. Statistical significance level was accepted as p<0.05. All statistical tests were two sided.

Result

Characteristics of participants and the prevalence of antenatal depressive symptoms

In the study, the majority of participants were in a stable marriage (89.5%) and were employed (73.7%). More than half of them have college/university degree and above (58.1%). 60.4% of them have better family functions, 31.5% and 8.1% have moderate and severe family dysfunction, respectively. 60.9% of them have medium levels of self-efficacy, 22.6% and 16.5% have low and high level, respectively (table 1). According to the standard of division, taking 10 points as the positive critical value of PHQ-9, 75 (9.2%) participants reported antenatal depressive symptoms within 2 weeks (95 CI% 7.2% to 11.2%).

Table 1.

The characteristics of the two groups of participants were compared (depressive symptoms vs no depressive symptoms)

| Variables | Depressive symptoms (n=75) | No depressive symptoms (n=738) | Total (n=813) | χ2 value | P value |

| Marital status | 0.21 | 0.65 | |||

| Stable | 66 (88.0) | 662 (89.7) | 728 (89.5) | ||

| Unstable | 9 (12.0) | 76 (10.3) | 85 (10.5) | ||

| Occupation | 0.04 | 0.84 | |||

| Employed | 56 (74.7) | 543 (73.6) | 599 (73.7) | ||

| Unemployed | 19 (25.3) | 195 (26.4) | 214 (26.3) | ||

| Education | 0.39 | 0.53 | |||

| Senior school and below | 34 (45.3) | 307 (41.6) | 341 (41.9) | ||

| College/university degree and above | 41 (54.7) | 431 (58.4) | 472 (58.1) | ||

| Family functions | 23.77 | 0.00 | |||

| Severe family dysfunction (0–3) | 17 (22.7) | 49 (6.6) | 66 (8.1) | ||

| Moderate family dysfunction (4–6) | 22 (29.3) | 234 (31.7) | 256 (31.5) | ||

| Better family functions (7–10) | 36 (48.0) | 455 (61.7) | 491 (60.4) | ||

| Self-efficacy | 21.65 | 0.00 | |||

| Low level (1–2) | 33 (44.0) | 151 (20.5) | 184 (22.6) | ||

| Middle level (2.1–3) | 34 (45.3) | 461 (62.5) | 495 (60.9) | ||

| High level (3.1–4) | 8 (10.7) | 126 (17.1) | 134 (16.5) |

Data are presented as n (%).

The results of χ2 tests and multivariate binary logistic regression analysis

According to the results of χ2 tests shown in table 1, the differences in family functions and self-efficacy between the two groups were statistically significant (p<0.05). Besides, the results of multivariate binary logistic regression showed that severe family dysfunction (AOR 3.67; 95% CI 1.88 to 7.14) and low level of self-efficacy (AOR 3.16; 95% CI 1.37 to 7.27) were the risk factors for antenatal depressive symptoms, after adjusted for occupation, marital status and education. (table 2)

Table 2.

Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of family functions and self-efficacy associated with antenatal depression symptoms

| Variables | COR* (95% CI) | AOR† (95% CI) |

| Family functions | ||

| Severe family dysfunction | 3.67 (1.88 to 7.14) | 3.67 (1.88 to 7.14) |

| Moderate family dysfunction | 0.99 (0.56 to 1.74) | 0.99 (0.56 to 1.74) |

| Better family functions | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-efficacy | ||

| Low level | 3.16 (1.37 to 7.27) | 3.16 (1.37 to 7.27) |

| Middle level | 1.14 (0.51 to 2.55) | 1.14 (0.51 to 2.55) |

| High level | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Characters in bold indicate statistical significance, p<0.05.

*Multivariate binary logistic regression model.

†Some general characteristics were adjusted (marital status, occupation and education).

AOR, adjusted OR; COR, crude OR.

Mediating effect of self-efficacy level between family functions and depressive symptoms

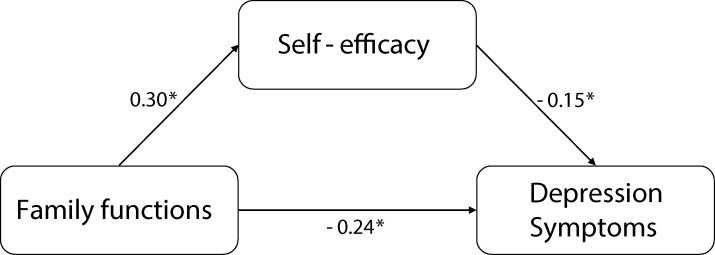

There was a significant correlation between family functions, antenatal depressive symptoms and self-efficacy in pregnant women. In indirect effects, family functions showed a positive correlation with self-efficacy(β=0.30, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.37, p<0.05) and self-efficacy showed a negative correlation with antenatal depression symptoms(β=−0.15, 95% CI −0.22 to −0.08, p<0.05). In direct effect, family functions showed a negative correlation with antenatal depression symptoms(β=−0.24, 95% CI −0.31 to −0.16, p<0.05)(table 3).

Table 3.

Mediation role of self-efficacy in the association between family functions and antenatal depression symptoms (n=813, Bootstrap=5000)

| Paths | β | SE | BCa 95% CI | P value | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Direct effects | |||||

| Family functions→self-efficacy | 0.30 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.00 |

| Family functions→antenatal depression symptoms | −0.24 | 0.04 | −0.31 | −0.16 | 0.00 |

| Self-efficacy→antenatal depression symptoms | −0.15 | 0.04 | −0.23 | −0.08 | 0.00 |

| Indirect effect | |||||

| Family functions→self-efficacy→antenatal depression symptoms | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.00 |

β, SE and 95% CI were the standardised regression effect value, SE and 95% CI of the direct and indirect effect estimated by the percentile bootstrap method.

Adjusted variables, marital status, occupation, education level; BCa, based-corrected and accelerated 5000 bootstrapping.

Self-efficacy level partially mediated the association between family functions and depressive symptoms, and the mediating effect accounted for 17.09% of the total effect. The mediation model of the association between family functions and antenatal depression symptoms by self-efficacy is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structural equation model testing self-efficacy as a mediator in the association between family functions and depressive symptoms. The model has been adjusted for marital status, occupation, education level. The above values have been standardised. *P<0.05.

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of antenatal depression symptoms is 9.2% (95CI% 7.2% to 11.2%), which was similar to the findings of previous studies.31 32 Besides, the findings showed that the risk of depression symptoms in participants who had family dysfunction was 3.67 times as much as that in the reference group (better functions group), family functions were directly and negatively associated with antenatal depression symptoms among women in the third trimester of pregnancy, the finding was in line with the study by Jin et al in China.33 A study which carried out in Taiwan, China also reported that pregnant women with antenatal depression symptoms tended to have lower family APGAR scores.34 Probably because Chinese people attach great importance to the family clan relations, they regard the family and its members as one of the most important sources of social support and spiritual sustenance. Pregnancy is viewed as a stressor, with the increasing of sensitivity and vulnerability of women in pregnancy, they are more likely to be influenced by the negative external environment and life events, which may lead to depression and other harmful emotional problems. In a well-functioning family, family members can detect the physical and psychological changes of women during pregnancy, and provide timely and effective spiritual and material help when pregnant women cope with stressor and crisis, so as to enhance their sense of family belonging, identity.35 However, family dysfunction reflects that pregnant women can’t acquire enough attention, love, identity and assistance from families, even family may be the source of mental pressure, so that depressive symptoms starts or aggravates. In this study, no significant association was found between moderate family dysfunction and depressive symptoms among women in their third trimester of pregnancy.

Furthermore, this study found that self-efficacy had a significant mediating effect on the association between family functions and antenatal depression symptoms, which was also recognised by Faure et al.36 Self-efficacy varies from person to person, and often changes within the individual over time and in response to specific experiences and environment. The level of self-efficacy could predict the mental activity and attitude in the face of difficulties and stressors, which would lead to different emotional response outcome.37 People with high self-efficacy are able to control self-abandoned thoughts, tend to handle situations rationally, are willing to accept the challenges of emergency. In other words, when a pregnant woman receives insufficient support, everyday life care, spiritual comfort and sympathy from her families, good self-efficacy can alleviate her negative emotions and depressive symptoms. On the contrary, people with low self-efficacy are prone to faltering, deal with problems emotionally, are helpless in the face of stress and easily are distracted by fear, panic and shyness, which are more likely to have depressive symptoms. Even in a family with good family functions, pregnant women with low self-efficacy could not make full use of family support and turn it into the motivation to improve their negative emotions.38 This may be a pathway for self-efficacy to play an intermediary role in the association between stressors and stress outcomes, which also in line with the model of Pearlin and Mccall.39 In addition, the mediation effect value is 17.09%, indicated partial mediation. The finding reflected that there were other mediators in the association between family functions and antenatal depression symptoms. Some other potential mediators have been proposed in previous studies among pregnant women. A study by Waqas et al in Pakistan showed that social support was mediated the association between total number of children, gender of children and antenatal depression.40 As a potential mediator, relational resilience affected the association between adverse childhood experiences and prenatal depression.41 However, the mediating effect of these variables has not been demonstrated in the association between family functions and antenatal depressive symptoms, which is worth exploring in future study.

The samples of this study were selected from pregnant women who were enrolled from community health service centres, with low no-response rate. Compared with the study with hospital samples, the samples were more representative of the truth of ordinary pregnant women. Women in the third trimester of pregnancy were selected to evaluate their antenatal depression symptoms for nearly 2 weeks, with less recall bias. There are some limitations in this study. First, this study was a cross-sectional study, although this study proved the association between family functions, self-efficacy and antenatal depression symptoms based on the established structural equation model, the validity of the theory still needs to be further followed up or tested through intervention experiments. Second, in this study, self-filled questionnaires were used, there was an inevitable reporting bias in this study, which might lead to the underestimation of positive reporting rate of depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

In summary, in this study the prevalence of antenatal depression symptoms is 9.2% among women in the third trimester of pregnancy. In this study, the findings suggested that pregnant women’s self-efficacy mediated the association between family functions and antenatal depression symptoms. On the one hand, family functions can negatively predict antenatal depression symptoms; on the other hand, self-efficacy can indirectly and negatively predict antenatal depression symptoms. Based on this finding, maternal and child health personnel can provide some early mental interventions to high-risk pregnant women, including family counselling courses for pregnant women’s families to improving family functions and peer education courses for pregnant women to increase their sense of self-identity and self-worth according to the actual needs. Reducing the pain and economic burdens of depression both by pregnant women themselves and their families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all teachers and students who generously shared their time and experience for this study. What’s more, we acknowledge the women who kindly gave constant to participate in research and the staff who cooperated with us in the investigation on the communities.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conceptualisation: BZ and ZH; Methodology: BZ, WZ and ZH; Investigation: BZ, ZH, WZ, YY, SY and XZ; Resources: XZ; Data Curation: BZ, YY and WZ; Writing-original draft preparation: BZ; Writing-review and editing, HX and ZH.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University (XYGW-2019–056).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. No data are available. For more original information, contact the corresponding author for appropriate reasons.

References

- 1.Weissman MM, Olfson M. Depression in women: implications for health care research. Science 1995;269:799–801. 10.1126/science.7638596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Hara MW, Wisner KL. Perinatal mental illness: definition, description and aetiology. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2014;28:3–12. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, et al. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:1071–83. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, et al. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:698–709. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin P-C, Hung C-H. Mental health trajectories and related factors among perinatal women. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:1585–93. 10.1111/jocn.12759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Harrington R. Life events, social support and depression in childbirth: perspectives from a rural community in the developing world. Psychol Med 2003;33:1161–7. 10.1017/S0033291703008286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, et al. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ 2001;323:257–60. 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, et al. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA 2006;295:499–504. 10.1001/jama.295.5.499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zayas LH, Cunningham M, McKee MD, et al. Depression and negative life events among pregnant African-American and Hispanic women. Womens Health Issues 2002;12:16–22. 10.1016/S1049-3867(01)00138-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kingston D, Tough S, Whitfield H, et al. Prenatal and postpartum maternal psychological distress and infant development: a systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2012;43:683–714. 10.1007/s10578-012-0291-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen C-H, Lin H-C. Prenatal care and adverse pregnancy outcomes among women with depression: a nationwide population-based study. Can J Psychiatry 2011;56:273–80. 10.1177/070674371105600506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross J, Hanlon C, Medhin G, et al. Perinatal mental distress and infant morbidity in Ethiopia: a cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2011;96:F59–64. 10.1136/adc.2010.183327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams SS, Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A. Fear of childbirth and duration of labour: a study of 2206 women with intended vaginal delivery. BJOG 2012;119:1238–46. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03433.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beavers R, Hampson RB. The beavers systems model of family functioning. J Fam Ther 2000;22:128–43. 10.1111/1467-6427.00143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CM M, Chen JY, Wang MX. Analysis of the anxiety status and influencing factors of pregnant women with second pregnancy in late pregnancy. J Nur Admin 2017;17:872–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lightsey OR, Burke M, Ervin A, et al. Generalized self-efficacy, self-esteem, and negative affect. Can J Behav Sci 2006;38:72–80. 10.1037/h0087272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol 1982;37:122–47. 10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A, Wood R. Effect of perceived controllability and performance standards on self-regulation of complex decision making. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;56:805–14. 10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayano G, Tesfaw G, Shumet S. Prevalence and determinants of antenatal depression in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019;14:e0211764:1–17. 10.1371/journal.pone.0211764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smilkstein G. The family Apgar: a proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam Pract 1978;6:1231–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smilkstein G, Ashworth C, Montano D. Validity and reliability of the family Apgar as a test of family function. J Fam Pract 1982;15:303–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarzer R, Aristi B. Optimistic self-beliefs: assessment of general perceived self-efficacy in thirteen cultures. World Psychology 1997;3:177–90. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang JX, Schwarzer R. Measuring optimistic self-beliefs: a Chinese adaptation of the general self-efficacy scale. Psychologia 1995;38:174–81. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung SK, Sun SY. Assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: further validation of the Chinese version of the general self-efficacy scale. Psychol Rep 1999;85:1221–4. 10.2466/pr0.1999.85.3f.1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. J Am Med Assoc 1999;282:1737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo B, Kaylor-Hughes C, Garland A, et al. Factor structure and longitudinal measurement invariance of PHQ-9 for specialist mental health care patients with persistent major depressive disorder: exploratory structural equation modelling. J Affect Disord 2017;219:1–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu X, Tam WWS, Wong PTK, et al. The patient health questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms among the general population in Hong Kong. Compr Psychiatry 2012;53:95–102. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roelofs J, Huibers M, Peeters F, et al. Effects of neuroticism on depression and anxiety: Rumination as a possible mediator. Pers Individ Dif 2008;44:576–86. 10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 2008;40:879–91. 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou JJ, Pan WG, Zhou J, et al. Depressive and anxiety symptoms during stages of perinatal period and influencing factors. J Neurosci Mental Health 2019;19:235–9. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Byatt N, Xiao RS, Dinh KH, et al. Mental health care use in relation to depressive symptoms among pregnant women in the USA. Arch Womens Ment Health 2016;19:187–91. 10.1007/s00737-015-0524-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin XY, Yu Y, DQ A. The study of the status of the family care and the anxiety of the second child pregnant woman. J Gen Nur 2019;17:109–10. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai SY. Relationship of perceived job strain and workplace support to antenatal depressive symptoms among pregnant employees in Taiwan. Women & Health 2018;59:1–26. 10.1080/03630242.2018.1434590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun S, Li J, Ma Y, et al. Effects of a family-support programme for pregnant women with foetal abnormalities requiring pregnancy termination: a randomized controlled trial in China. Int J Nurs Pract 2018;24:e12614–9. 10.1111/ijn.12614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faure S, Loxton H. Anxiety, depression and self-efficacy levels of women undergoing first trimester abortion. S Afr J Psychol 2003;33:28–38. 10.1177/008124630303300104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Stress processes and depressive symptomatology. J Abnorm Psychol 1986;95:107–13. 10.1037/0021-843X.95.2.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maddux JE, Meier LJ. Self-efficacy and depression : Self-efficacy, adaptation, and adjustment. New York: Springer, 1995: 143–69. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearlin LI, Mccall ME. Occupational stress and marital support. New York: Springer, 1990: 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waqas A, Raza N, Lodhi HW, et al. Psychosocial factors of antenatal anxiety and depression in Pakistan: is social support a mediator? PLoS One 2015;10:e0116510. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howell KH, Miller-Graff LE, Schaefer LM, et al. Relational resilience as a potential mediator between adverse childhood experiences and prenatal depression. J Health Psychol 2020;25:545–57. 10.1177/1359105317723450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.