Virtual conferences and educational platforms facilitate global connectivity.

Central Message.

The online move of conferences and education leads to an improved ability of trainees, international colleagues, and underrepresented members of the surgical team to access educational opportunities.

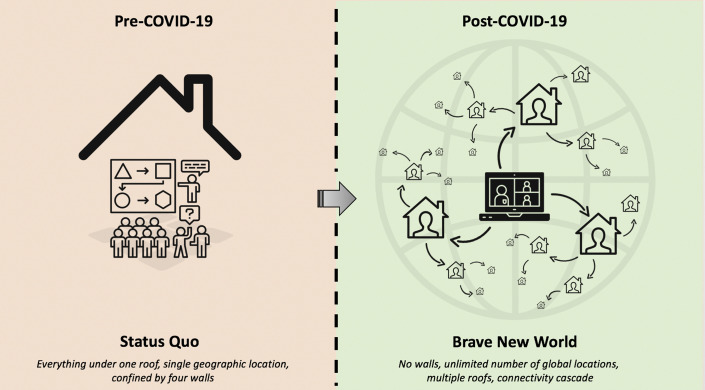

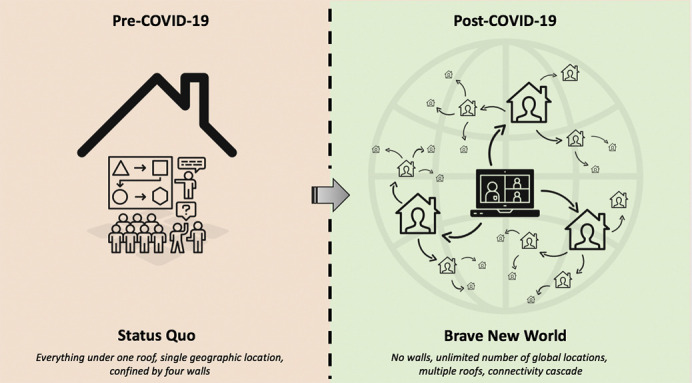

We are in a “Brave New World” that is unchartered and open for progress and potential paradigm shifts. What was supposed to be a memorable year for the American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) became one with an unexpected turn of events but one fitting for the era we live in. The centennial (100th) meeting of the AATS moved to a virtual platform for the first time in its history, and the leadership should be credited for their nimble response. Themed “A Virtual Learning Experience,” it was the most attended meeting in the Association's history and was supposed to take place in New York City, the country's epicenter at the time—fitting for a historic centennial experience. Approximately 6000 attendees from all corners of the world, of all pertinent cardiothoracic surgical subspecialties, across all stages of one's career, and among all socioeconomic backgrounds joined to learn and discuss the latest developments in our field. After decades of societal separation without the presence of an overarching world federation in the field of cardiothoracic surgery, the geographic entry barriers and walls to academic conferences had been lowered (Figure 1 ). For the first time, there was a collection of speakers from around the globe providing presentations to attendees from around the globe at significantly lower costs for organizers and participants. This paradigm shift illustrative of the important widespread impact of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may set a new standard with encouraging consequences for the future of surgical education and conferences.

Figure 1.

Virtual conferences and educational platforms facilitate global connectivity. COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019.

While the eyes of many are on the immediate impact of COVID-19, the collateral damage on patient care and the pandemic's financial, educational, and psychosocial consequences require reflection and all-round paradigm shifts.1 The educational and academic impact, especially for the advancement of our field and the training of future generations of surgeons, cannot be understated. Scheduled diagnostic and therapeutic procedures had been canceled, and the resurgence comes with great concern of the unique disease manifestations of concurrent COVID-19 infection.2, 3, 4 This temporary reduction in case volume, a shift to COVID-19 care and deployment to other areas of the hospital, and the reduction in in-person teachings (eg, Grand Rounds, workshops, simulation labs) have left trainees concerned about the impact on their training.5 , 6 This is particularly important during the final part of their training, where increasing autonomy is given, expected, and vital for successful transition to the initial staff year. In addition, multidisciplinary (eg, heart team) meetings have been reduced to adhere to social distancing protocols.7 Equally so, the suspension of gatherings in public venues led to a cancellation of major conferences, a postponement of others, and a virtual shift of a few. Last, the pandemic has complicated licensing exams, job and fellowship interviews, and learning visits by surgeons to experienced colleagues to take place as they traditionally did, requiring prompt adaptations by educational bodies and programs.8

The Concerns

The initial concerns from an academic perspective of halting in-person scientific meetings were substantial. First, conferences are an opportunity to share research, groundbreaking results, and novel techniques. These opportunities are especially critical for trainees for whom these presentations serve as practice and learning moments, as well as the ability to share their hard work and engage with peers and attendings. For junior faculty, conferences contribute to academic advancement within societies and institutional tenure tracks. Second, the large gatherings of clinicians, researchers, and trainees facilitate invaluable networking opportunities from which career-defining mentorship relationships and academic collaborations ensue. Relationships and camaraderie are fostered between trainees and with faculty that have lifelong ripple effects through specialty-specific support networks. Unsurprisingly, networking opportunities are often raised as the biggest strength of meetings in postconference surveys. Third, hands-on workshops and navigating exhibit halls to interact with industry representatives and learn about technical developments in the field are indispensable strengths of major conferences. Fourth, job interviews and research team meetings (eg, multicentric collaboratives) commonly take place at conferences.

The Triumphs

This “new normal” is a silver lining of the pandemic and a welcomed opportunity for the future of surgical fields, illustrated by the first virtual AATS conference. Additionally, thousands of participants joined across different webinars hosted by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS), the American College of Surgeons, and the Cardiothoracic Surgery Network—the latter convening approximately 2000 participants within 1 week of preparation, highlighting the ability of virtual events to be impactful and nimble. The STS has been a leader in pivoting to a biweekly webinar-based educational platform prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with topics ranging from cardiothoracic surgery continued medical education to various COVID-related topics pertinent for all specialties. For the first time, the “Global Summit on Reactivating Cardiothoracic Surgery Programs,” hosted in May 2020 by the STS, featured the presidents representing the most prominent professional societies of our specialty globally (STS, AATS, American College of Surgeons, European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery, European Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Asian Society of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery) and attracted a live audience of more than 1000 unique viewers from 57 countries—a far-reaching achievement that would have never been possible in an in-person meeting. This illustrates the possibilities of and necessity for professional societies to swiftly and effectively collaborate to bring out much-needed guidelines and recommendations during times of darkness.9 COVID-19 has unique repercussions on the perioperative and postoperative disease course, requiring careful reconsideration to best inform surgeons and trainees about novel risk factors and new best practices.10

The requirement to take time off from work to travel for academic conferences made it difficult for some to attend meetings (eg, those who are junior; not presenting; on medical, pregnancy, or parental leave; or who cannot leave their clinical practice for a prolonged period of time). In addition, the financial barriers to pay for registration, accommodations, flights, and sometimes visas impede an equitable balance of participants across different stages of their careers and different parts of the United States and the world. This led to a self-selection of those privileged to attend and contribute to conferences.11 Likewise, these positive changes can help bridge gaps in the workforce and continued medical education between high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) by ensuring openly accessible and inclusive educational platforms.12 , 13 The scaling of virtual conferences and e-learning may support more efficient training of our colleagues in LMICs, where specialty training programs are scarce.14 , 15 Ultimately, this ensures that underrepresented voices get a seat at the table, able to attend, network, and speak up.

The Lessons Learned

Important lessons can be drawn from experiences during the pandemic, including the following:

-

1.

Whole audience participation: Although question rounds enable some discussion after presentations, the limited time available and the hesitancy of some participants to ask questions (eg, trainees intimidated by audience's experience or individuals uncomfortable with speaking English) result in limited audience participation at in-person conferences. In contrast, online chat boxes allow for simultaneous discussions with participants and presenters and lower the threshold to ask questions, mitigating residual power differentials between participants from different stages in one's career. Individuals uncomfortable raising a question or comment at a microphone in a crowded hall can now be more empowered to do so—leveling the playing field. Moreover, speakers and moderators are able to poll participants and crowdsource ideas or practice patterns to inform case-based discussions. Lastly, participants can more easily attend multiple sessions by shifting browsers, as opposed to being required to traverse an entire venue.

-

2.

Scaling of medical education: Virtual platforms scale access to education opportunities regardless of participants' location in the world. By ensuring the ability of platforms to carry thousands of participants while requiring limited bandwidth, gaps in access to content are narrowed. Moreover, recordings can immediately be uploaded for rapid dissemination, especially important for groundbreaking research and discussions. Furthermore, participants are able to view these recorded webinars at their own leisure and repeatedly.

-

3.

Research presentations: Although some virtual conferences have presented a limited number of original research abstracts or late-breaking trials, the opportunity should arise to enable more participants to share their research similar to poster and podium presentations at in-person conferences. Accepted abstracts should be made available online and can be supplemented with prerecorded presentations linked to the abstracts. This ensures widespread scholarly dissemination and participation, especially for young faculty and trainees, and will add to the development of a societal repository and institutional memory.

-

4.

Streamlining networking: Virtual conferences should leverage the possibilities of technology and social media to optimize networking. In many ways, in-person networking at conferences is a hit-or-miss for trying to connect with like-minded individuals, especially for early-career participants. Virtual platforms can allow participants to log on with profiles with preregistered interests to more easily identify others with common interests or expertise.

-

5.

Innovation and industry immersion: Ensuring means of integrating immersive virtual exhibit halls and, where possible, remote hands-on workshops can maintain specialty advancement similar to the STS/AATS Tech-Con.16 Additionally, unlike large and crowded in-person exhibit halls, such virtual halls allow participants to more easily navigate different stands.

-

6.

Social media and data analytics: The AATS virtual meeting had more than 3000 tweets and more than 10 million impressions in just 2 days, highlighting the growing role of social media discussions and connectivity complementing conferences.17 These features can be further integrated in conference platforms but illustrate the more personal, instantaneous, and global discussions taking place to a larger than ever extent. Additionally, online gatherings enable instant assessment of the number of participants, demographics, and participant engagement in various sessions. These data are crucial for organizers to fine-tune future events, while better tailoring conferences and sponsors to participants.

The Limitations

Naturally, several limitations remain, in part due to the novelty of virtual conferences. To date, virtual conferencing is still quite impersonal with mere text-based interaction. Technologic issues have led several virtual conferences to opt for prerecorded presentations. While presenters are often online and available for questions via the chat box, this does not allow for interactive engagement similar to live, audible questions and discussions at in-person meetings. Further, reliable internet may not always be available for everyone, potentially limiting participants' ability to fully absorb content or engage in discussions. Last, virtual platforms lack general networking areas (eg, lobby) to discuss and meet other participants. Despite the many advantages of virtual platforms, there is still an essential role and value of face-to-face interaction, which is simply human nature. The ultimate resolution may be a hybrid approach: a virtual element for didactics combined with shortened in-person meetings that focus on genuine “hands-on” learning and direct face-to-face interaction. Such an approach ensures that anyone, anywhere, is able to participate to some extent. Technology is rapidly advancing and so is our learning curve with virtual conferences—approaching a point where the ability to network, educate, and connect people virtually may eventually outperform or at the very least complement physical meetings.

The Possibilities

The possibilities are numerous. In terms of surgical education, several important recommendations have already been raised.6 These include developing standardized technical metrics to assess competency during times of decreased surgical volume, whereby faculty play an important role in ensuring mastery of techniques in a gradually more autonomous manner. This increased reliance on faculty to “sign off” on trainees' skills versus conventional case logs comes with the need to more widely train faculty as effective educators. Moreover, they can include the following:

-

1.

Virtual Grand Rounds and teaching forums: Largely speaking, departments and divisions have weekly Grand Rounds or resident teaching forums that vary from institution to institution. Opportunities arise to standardize such forums in a way that enables all cardiothoracic surgical residents to attend the same (virtual) teaching sessions. Experiences with debate-style journal clubs, for example, suggest the possibility of virtually extending traditional educational paradigms beyond single institutions and geographic regions.18 Broadcasting journal clubs through social media has been successful in reaching larger audiences.19 Similar opportunities arise for educational groups, such as the Thoracic Education Cooperative Group, to expand their networks into the virtual world.20

-

2.

Context-specific learning: Virtual learning may enable similar programs (eg, geographic based on ethnical and genetic variations or resource constraints) to share lessons and find common solutions to specific patient problems or institutional barriers. This may enable underrepresented voices to share their findings and expertise to an extent not previously possible. Such shared learning can equally benefit programs by adapting practices to adopt lower-cost or resource-conscious techniques.

-

3.

Multidisciplinary discussions: Where conferences and surgical case discussions tend to only minimally include nonsurgical (eg, cardiology, intensivist, nurse) voices, often due to schedule, location, or work hour conflicts, virtual platforms can encourage multidisciplinary discussions and be recorded for future review. Case studies may run through the entirety of patients' hospital flow (eg, emergency visit, imaging, operation, outpatient clinics) with panels of specialty-specific experts and educators, ultimately benefiting all team members alike.

-

4.

Extended reality integration: Using a combination of virtual reality, augmented reality, and mixed reality platforms, surgical education can be complemented in a remote but interactive manner.21 Introducing such innovations is highly needed given the field's strong interface with technology, where surgeons and trainees benefit from reconstructions of complex 3-dimensional structures.22 Virtual learning platforms, whether through simulation models that can be used at home or e-learning platforms that guide learners through procedures and anatomic structures, are especially helpful to address the difficulties in surgical education during the pandemic.23 These experiences may eventually be scaled at lower costs to enable LMIC trainees and surgeons to improve their skills without requiring expensive travels and workshops abroad.

-

5.

Resource centralization: The costs associated with conventional workshops and curriculums and the decentralization of procedure-specific trainings hinder the ability to train the maximal number of individuals—only benefiting those participants able to obtain time off or financial support. The Cardiothoracic Surgery Network, STS, and AATS have succeeded to collate operative videos, convene panels and case discussions, and select training resources on a centralized platform that can further be leveraged to bring together open-access curriculums to more widely train individuals around the world.24 Other platforms, such as Heart University, attempt to complement this with multidisciplinary, disease-specific, and free educational modules.25

The Future

The future is positive. Ultimately, virtual modalities for conferences will not serve as substitutes after the pandemic but important complements to foster a hybrid approach with broader and more inclusive reach—critical to bridge gaps in access to numerous opportunities in our field.

No crisis should go to waste, and opportunities to upgrade will always be present and should provide a substrate for improvement. Recovering from COVID-19 will only be possible if we embrace the changes needed to prevail as surgical specialties. The silver lining is improved collaboration among specialties, societies, peers, colleagues, and experts from around the world through more equitable and accessible virtual practices that not only advance science and clinical care during times of uncertainty but also bring us all closer together—even if apart. The COVID-19 pandemic and post–COVID-19 era are our “Brave New World,” full of paradigm shifts and opportunities that require readiness, decisive leadership, bold innovation, and unity. The only question that remains: Are we brave enough to embrace it?

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr Nguyen is a consultant for Edwards LifeSciences, Abbott, and LivaNova. All other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Vervoort D., Luc J.G.Y., Percy E., Hirji S., Lee R. Assessing the collateral damage of the novel coronavirus: a call to action for the post-COVID-19 era. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110:757–760. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nepogodiev D., Bhangu A. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg. May 12, 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11746. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher B., Seese L., Sultan I., Kilic A. The importance of repeat testing in detecting coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a coronary artery bypass grafting patient. J Card Surg. 2020;35:1342–1344. doi: 10.1111/jocs.14604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vervoort D., Nguyen T.C. Commentary: coronary artery bypass grafting in COVID-19 patients: darkness cannot drive out darkness. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. June 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.05.061. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caruana E.J., Patel A., Kendall S., Rathinam S. Impact of Covid-19 on training and wellbeing in subspecialty surgery: a national survey of cardiothoracic trainees in the United Kingdom. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. June 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.05.052. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller S., Vaporciyan A., Dearani J.A., Stulak J.M., Romano J.C. COVID-19 disruption in Cardiothoracic surgical training: an opportunity to enhance education. Ann Thorac Surg. June 1, 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.05.015. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wahadat A.R., Sadeghi A.H., Tanis W. Heart team meetings during COVID-19. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1872–1874. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olive J.K., Luc J.G.Y., Cerqueira R.J., Eulert-Grehn J.J., Han J.J., Phan K., et al. The cardiothoracic surgery trainee experience during the COVID-19 pandemic: global insights and opportunities for ongoing engagement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. June 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.06.060. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood D.A., Mahmud E., Thourani V.H., Sathananthan J., Virani A., Poppas A., et al. Safe reintroduction of cardiovascular services during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidance from North American Society Leadership. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3177–3183. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.COVIDSurg Collaborative Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2020;396:27–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31182-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vervoort D. The Visa Conundrum in Global Health. BMJ Opinion. 2019. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2019/06/21/dominique-vervoort-the-visa-conundrum-in-global-health/ Available at:

- 12.Vervoort D., Meuris B., Meyns B., Verbrugghe P. Global cardiac surgery: access to cardiac surgical care around the world. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;159:987–996.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma X., Vervoort D. Leveraging e-learning for medical education in low- and middle-income countries. Cardiol Young. 2020;30:903–904. doi: 10.1017/S1047951120001109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nissen A.P., Smith J.A., Schmitto J.D., Mariani S., Almeida R.M.S., Afoke J., et al. Global perspectives on cardiothoracic, cardiovascular, and cardiac surgical training. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. February 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.12.111. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vervoort D., Velazco-Davila L.D. Closing the gap by filling the gaps: leveraging international partnerships to train the world's cardiac surgical workforce. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;160:E51–E52. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.03.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levitsky S., Chitwood W.R., Orringer M.B., Mack M.J. Education above and beyond: innovative STS educational initiatives. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(1 Suppl):S29–S33. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luc J.G.Y., Antonoff M.B. Live tweet the Society of Thoracic Surgeons annual meeting: how to leverage twitter to maximize your conference experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106:1597–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luc J.G.Y., Nguyen T.C., Fowler C.S., Eisenberg S.B., Wolf R.K., Estrera A.L., et al. Novel debate-style cardiothoracic surgery journal club: results of a pilot curriculum. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104:1410–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ni hIci T., Archer M., Harrington C., Luc J.G.Y., Antonoff M.B. Trainee thoracic surgery social media network: early experience with TweetChat-based journal clubs. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.05.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antonoff M.B., Nguyen S., Nguyen T.C., Odell D.D. Conducting high-quality research in cardiothoracic surgical education: eecommendations from the thoracic education cooperative group. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157:820–827.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.09.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen K., Bjerrum F., Hansen H.J., Petersen R.H., Pedersen J.H., Konge L. A new possibility in thoracoscopic virtual reality simulation training: development and testing of a novel virtual reality simulator for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015;21:420–426. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivv183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sacks L.D., Axelrod D.M. Virtual reality in pediatric cardiology: hype or hope for the future? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2020;35:37–41. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKechnie T., Levin M., Zhou K., Freedman B., Palter V., Grantcharov T.P. Virtual surgical training during COVID-19: operating room simulation platforms accessible from home. Ann Surg. May 1, 2020 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003999. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Replogle R.L. Origins of the cardiothoracic surgery network (CTSNet) Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(1 Suppl):S25–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tretter J.T., Windram J., Faulkner T., Hudgens M., Sendzikaite S., Blom N.A., et al. Heart University: a new online educational forum in paediatric and adult congenital cardiac care. The future of virtual learning in a post-pandemic world? Cardiol Young. 2020;30:560–567. doi: 10.1017/S1047951120000852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]