Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Behavioral health homes, which provide primary medical care onsite in mental health clinics, face challenges in integrating information across multiple health records. This study tested whether a mobile personal health record improves quality of medical care for individuals treated in these settings.

METHODS:

This randomized study enrolled 311 participants with a serious mental illness and one or more cardiometabolic risk factor across two behavioral health homes to receive a mobile personal health record app (n=156) or usual care (n=155). For the intervention group, a secure mobile personal health record app (mPHR) provided participants with key information about diagnoses, medications, and lab values, and allowed them to track health goals. The primary study outcome was a chart-derived composite measure of quality of cardiometabolic and preventive services.

RESULTS:

At 12-month follow up, participants in the mPHR group maintained high quality of care (70% of indicated services at baseline and 12-month follow-up), in contrast to a decline in quality for the usual care group (71% at baseline and 67% at follow up) resulting in a statistically significant but clinically modest differential impact between the intervention and usual care group. No differences between the study groups were found in secondary self-reported outcomes including delivery of chronic illness care, patient activation, or mental or physical health related quality of life.

CONCLUSIONS:

A mobile personal health record was associated with a statistically significant but clinically modest differential benefit for quality of medical care in individuals with serious mental illness and cardiovascular comorbidity.

Clinicaltrials.gov registry number: NCT01890226. The study was approved by the EmoryUniversity Institutional Review Board

Introduction

Patients with serious mental illness are at risk for poor quality of general medical care. (1, 2) Challenges in illness self-management, (3), stigma among general medical providers, (4) and poor coordination between medical and mental health delivery systems (5) can limit these individuals’ ability to obtain appropriate and timely medical services.(2) Poor quality of care, in turn, represents an important risk factor for disability and early mortality in this population.(6, 7)

Behavioral health homes, in which routine medical services are provided onsite at a community mental health center (CMHC), are increasingly being used to improve access and coordination of care in this population.(8, 9) However, while these models hold promise for improving quality medical care,(10) there remain challenges to their effective implementation.(11, 12). Health IT limitations, including the ability to integrate information across medical and mental electronic health records, remain among the most important barriers to effective implementation of these models. (13)

In the general population, electronic Personal Health Records (PHRs) have been identified as a promising approach for shifting the ownership and locus of health records from being distributed across multiple providers to an approach that is longitudinal and person-centered.(14) Still, early efforts to develop web-based PHRs have been hampered by challenges in interoperability across different platforms and in patient accessibility, with rates of meaningful use below 10%.(15, 16)

With the growing use and capability of smartphones, there is an opportunity to develop PHRs for mobile platforms, or mobile Personal Health Records (mPHRs).(17) These new technologies offer the potential for ubiquitous access to medical information, and with the adoption of new interoperability standards, the ability to harmonize data across multiple different records. (18) More than four fifths of Americans now own smartphones, up from just 35% in 2011, with growing penetration among vulnerable populations including those with serious mental illnesses.(20) The recent introduction of a mobile PHR capability within Apple Health may herald the more widespread use of mobile PHRs by the general public.(21)

High rates of comorbidity and poor coordination between medical and mental health care among populations with serious mental illness could make them a particularly important population in whom to develop and implement mobile personal health records. However, few data exist assessing the potential impact of these programs in these individuals. Several studies have found that electronic health records are feasible to implement in populations with serious mental illness, either in isolation(22, 23) or as part of larger care manager interventions.(24), and hold potential to improve quality of medical care. (25) Reflecting the technologies available at the time, these PHRs were all web-based and were either tethered to a single electronic health record or required manual data entry.

This randomized trial tested an integrated mobile PHR designed for patients with serious mental illnesses and medical comorbidity treated in behavioral health homes. The goals of the study were to assess the intervention’s impact on quality of medical care and on other clinical outcomes.

Methods

Overview

Recruitment, Eligibility, and Randomization:

The study was conducted in two behavioral health homes, one urban and suburban community mental health center. Potential participants were referred by mental health providers or selected from a roster of active patients in the clinics. The inclusion criteria were 1) presence of a serious mental illness (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder, with or without comorbid substance use)(26) confirmed by chart review, and 2) One or more cardiovascular risk factor (diabetes, hypertension, or hypercholesterolemia), confirmed by chart review. The exclusion criterion was cognitive impairment based on a score of ≥ 3 on a 6-item, validated screener. (27) Subjects who met eligibility criteria and provided informed consent to participate were randomly assigned stratified at the patient level within each clinic to either the intervention group or usual care.

Each behavioral health home provided preventive screening, general medical care, and ob/gyn services onsite at the mental health clinic. One of the clinics had two separate records for mental health and medical care, and the other, which was a part of a larger safety net health system, had a combined record.

Study arms:

The intervention group received the mobile personal health record app. A total of 64 (41%) of participants in the intervention group did not have smartphones; to ensure representativeness to the broader population, these participants received study smartphones loaded with the mPHR app.

The study app was developed using principles of user-centered design, (28), with a particular focus on usability in a medically complex population who commonly have limited health and computer literacy. Results from two focus groups were used to identify key domains for inclusion in the mPHR, and to develop and refine a user interface appropriate for the population.

The app was programmed using Sencha Touch in conjunction with the native Java Android HealthVault software development kit (SDK), a platform developed by Microsoft to store health information for the PHR. Patient portals from EHRs were used to upload data to the MPHR; the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standard(18) was used to populate fields on the handheld device from data across the EHRs and to harmonize data.

The HealthVault security system works with cryptographic constructs available more widely on smartphones to preserve user privacy. All information was stored on a HIPAA-compliant server.

The mPHR included fields for current medications; allergies; and anthropomorphic measures including blood pressure, weight, BMI, and waist circumference, medical records information including list of conditions, allergies, immunizations, anthropomorphic measures (i.e, blood pressure, weight), and lab values (i.e., glucose, cholesterol, hemoglobin A1c). Data were refreshed from the health record whenever a participant used the app. The app also included a field for participants to identify long-term health goals. These goals were broken down into action plans, which involved setting and tracking short-term, feasible clinical targets, and tracking progress towards those targets.(29)

Two trained Certified Peer Specialists (CPS) subcontracted through the state’s mental health consumer network served as clinical technology specialists,(30) providing training and support for participants in the use of the app. The role of the clinical technology specialists was limited to assistance with the use of the smartphone and mPHR app. The training sessions included both instruction in use of the app and as needed, in the use of the mobile phones. Teach-back approaches were used to assess participants ability to demonstrate key functions of the smartphone and app. (31)Subsequently they met monthly with participants to troubleshoot any issues with the study app or smartphone. They did not provide any care management services such as scheduling appointments or laboratory tests, and did not assist with data entry.

Each CPS received a two-week training program in use of the personal health record from the research staff. The program included a manual providing structured guidance in use of the health record. The research team provided weekly supervision for the CPS providers, reviewing caseloads and troubleshooting any problems that arose.

The usual care group had access to the full array of services offered through the behavioral health homes, but did not receive a PHR app and did not have access to the clinical technology specialists.

Outcomes:

The primary study outcome was a composite measure of quality of preventive medical services and cardiovascular care. Indicators from RAND’s Community Quality Index study (32) were constructed using chart reviews by unblinded research interviewers from participants’ medical and mental health charts. These measures have been validated in general populations based on their demonstrated link with improved health outcomes. (33) Quality of preventive medical services and eligible populations were derived from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, with 11 indicators used for the study: screening for blood pressure; cholesterol; colorectal cancer; diabetes; HIV; obesity; tobacco; sexually transmitted diseases; mammography; pap smear; and chlamydia (22). A list of all of the quality indicators, along with the eligible populations for each, are attached. Because most of the individual subscales only applied to limited demographic or clinical subsets of the population, a single, aggregate quality score across all conditions was used as the primary study outcome. The aggregate score represents the total number of eligible services received for an individual generated by dividing all instances in which recommended care was delivered by the number of times a participant was eligible for the indicator.

The study also collected secondary self-reported outcome measures. Coordination of care was assessed using the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care measure, a 20-item patient self-report instrument that assesses the extent to which patients with chronic illness report receiving care that aligns with the Chronic Care Model. (34–36) Activation, which assesses a patients’ perceived ability to manage their illnesses and their healthcare visits, was assessed using the Patient Activation Measure (PAM),(37) Health-related quality of life was measured using the Physical and Mental Component Summary scales of the SF-12. (38–40)

App usage was collected for all study participants in the intervention group. A threshold of at least weekly app usage was established a priori as a minimum usage representing fidelity to the study intervention.

The study protocol was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted as intent-to-treatusing [SAS/STAT] software, Version [9.4] of the SAS System for [PC] (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and SPSS v21.0. The ANOVA test and Chi-square test were used to compare the distribution of baseline characteristics between the intervention and the control group. Marginal Linear Models (MLM) and Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) were used to analyze outcomes measured over time, and the restricted maximum likelihood and maximum likelihood estimation approach were used to account for the longitudinal nature of the data and to handle missing data. SAS PROC GLIMMIX procedure was used for continuous variables and PROC GENMOD procedure was used for binary variables and the likelihood ratio tests were conducted to evaluate a meaningful and reasonable symmetric covariance structure for each MLM model. For each outcome measure, the model assessed the outcome as a function of 1) randomization, 2) time since randomization, and 3) group-by-time interaction. The group-by-time interaction, which reflects the relative difference in change in the parameters over time, was the primary measure of statistical significance.

To assess whether there was a differential effect by study site or baseline patient characteristics, moderator analyses were conducted for: 1) clinic site 2) CVD morbidity (1 vs. 2 or more CVD conditions 3) and smartphone ownership status at the time of enrollment. Analyses examined the group*time*moderator interaction across each of these categories.

To account for possible loss to follow-up or missing responses, multiple imputation procedures were performed as sensitivity analyses. Little’s MCAR test was used to examine the missing mechanism assumption for multiple imputation, and there was no evidence suggesting that the missing data was not missing completely at random (p value for Little’s test=0.73).(41) The multiple imputation model included all key analysis variables, variables that were correlated with the analysis variables and variables that might predict missing data on the analytic variables. Twenty datasets were imputed using a fully conditional specification method. The variability between the estimates from the twenty imputations and those from the main analysis were minimal due to the missing completely at random mechanism of the data.

Hypotheses were two sided and tested at a 0.05 significance level. We pre-specified a single primary outcome (composite quality of medical care) to minimize Type I error and used a p value of 0.05 for exploratory analyses of secondary outcomes in order to minimize the potential for Type II error. (42–44)

Results

Of 458 participants screened for eligibility, 311 were eligible and consented to participate (Figure 1). The most common reason for lack of eligibility was not meeting inclusion criterion of having a cardiometabolic condition. Participants were randomized to either the intervention (n=156) or to usual care (n=155).

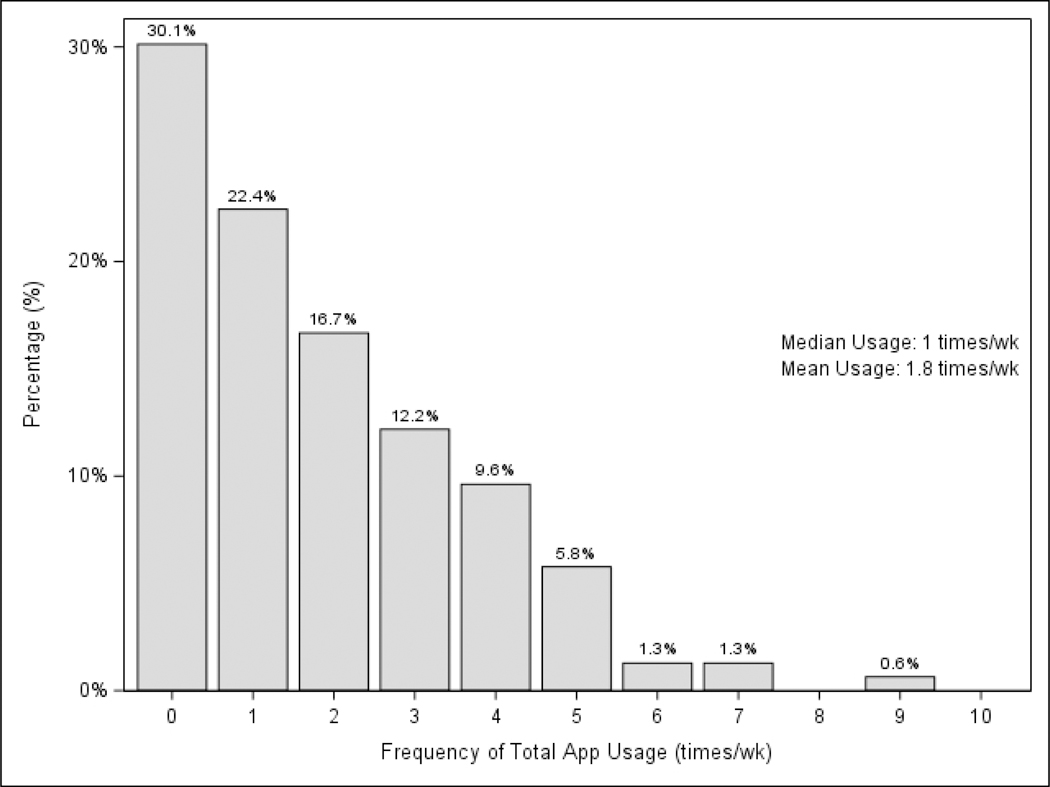

Figure 1: mPHR Usage.

Chart review data, which were used to assess overall quality of care, were available for all participants at baseline and 12-month follow-up. Completion rates for patient interviews were 91.9% at 6-months and 84.6% for 12 months, with similar rates of attrition in both groups. (Figure 1)

The mean age of participants was 51, a total of 60% of participants were female, 77% were African American, and most were either uninsured (50.5%) or covered by Medicaid (35%). (Table 1). The most common mental health diagnosis was major depression (76.5%) and the most common cardiometabolic comorbidities were hypertension (82.6%) and diabetes (43.7%). None of the demographic or clinical characteristics differed significantly between the intervention and control groups. (Table 1)

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics

| Case (n=156) | Control (n=155) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Mean (N) | Percentage (%) | Mean (N) | Percentage (%) | P-value |

| Age, years (M±SD) | 50.78±8.45 | 50.54±9.08 | 0.81 | ||

| Male | 61 | 39 | 63 | 41 | 0.78 |

| Single | 94 | 60 | 82 | 53 | 0.19 |

| Race | 0.21 | ||||

| White | 29 | 19 | 29 | 19 | |

| Black | 118 | 76 | 123 | 79 | |

| Other Race | 9 | 6 | 3 | 2 | |

| Hispanic | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0.41 |

| Education, years (M±SD) | 12.15±2.30 | 12.11±2.36 | 0.87 | ||

| Stable Housing | 124 | 79 | 136 | 88 | 0.05 |

| Total Annual Income | 0.99 | ||||

| $0–$5,000 | 86 | 55 | 83 | 54 | |

| $5,000–$10,000 | 42 | 27 | 43 | 28 | |

| $10,000–$15,000 | 18 | 12 | 17 | 11 | |

| More than $15,000 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 5 | |

| Stable Employment | 18 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 0.26 |

| Disability | 63 | 40 | 63 | 41 | 0.96 |

| Medicaid | 57 | 37 | 52 | 34 | 0.58 |

| Medicare | 28 | 18 | 35 | 23 | 0.31 |

| None of the above | 77 | 49 | 80 | 52 | 0.69 |

| Private Insurance | 24 | 15 | 35 | 23 | 0.17 |

| Medical Diagnosis | |||||

| Diabetes | 68 | 46 | 68 | 47 | 0.83 |

| Heart Disease/CAD/CHD | 13 | 9 | 13 | 9 | 0.96 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 72 | 49 | 70 | 48 | 0.86 |

| Hypertension | 134 | 86 | 123 | 83 | 0.35 |

| Mental Diagnosis | |||||

| Schizophrenia | 34 | 22 | 33 | 21 | 0.91 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 43 | 30 | 41 | 28 | 0.63 |

| Depression | 116 | 76 | 122 | 81 | 0.24 |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 4 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 0.54 |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 35 | 24 | 26 | 18 | 0.2 |

Within the intervention group, a total of 78.2% used the app at least once per week, the minimum pre-specified for fidelity to the intervention (Figure 2). Most app events involved viewing, with a smaller percentage editing or adding items (See online supplement).

The primary study outcome was receipt of indicated cardiometabolic and preventive services. At follow up, participants in the intervention group received 70% of indicated services on the measure at baseline and 12-month follow-up, as compared to a decline from 71% to 67% in the usual care group. The group*time effect for this interaction was statistically significant. (F=4.18, DF=1, n=309, p=0.04). (Table 2)

Table 2:

Study Outcomes: Intervention Versus Usual Care

| Intervention | Usual Care | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | F Value | Num DF | Den DF | P-value for Group*time interaction |

| Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care | 0.61 | 2 | 854 | 0.54 | ||||||

| Baseline | 156 | 3.20 | 0.95 | 155 | 3.23 | 1.00 | ||||

| 6-Month | 145 | 3.32 | 0.93 | 141 | 3.32 | 1.01 | ||||

| 12-Month | 132 | 3.25 | 0.94 | 131 | 3.18 | 0.95 | ||||

| Patient Activation Measure | 0.71 | 2 | 855 | 0.49 | ||||||

| Baseline | 156 | 58.78 | 14.65 | 155 | 57.83 | 13.65 | ||||

| 6-Month | 145 | 59.82 | 15.89 | 141 | 60.88 | 15.18 | ||||

| 12-Month | 132 | 61.61 | 16.19 | 132 | 62.08 | 14.77 | ||||

| SF-12 PCS | 0.32 | 2 | 821 | 0.73 | ||||||

| Baseline | 147 | 35.74 | 11.83 | 150 | 35.70 | 11.62 | ||||

| 6-Month | 138 | 37.20 | 11.94 | 133 | 36.32 | 11.52 | ||||

| 12-Month | 129 | 37.03 | 12.15 | 130 | 36.09 | 11.75 | ||||

| SF-12 MCS | 0.56 | 2 | 821 | 0.57 | ||||||

| Baseline | 147 | 35.50 | 12.54 | 150 | 36.55 | 13.25 | ||||

| 6-Month | 138 | 39.16 | 13.48 | 133 | 38.70 | 13.18 | ||||

| 12-Month | 129 | 41.68 | 14.04 | 130 | 41.16 | 11.61 | ||||

| BMI | 0.16 | 2 | 851 | 0.86 | ||||||

| Baseline | 155 | 33.00 | 8.18 | 155 | 33.37 | 8.18 | ||||

| 6-Month | 145 | 32.87 | 7.74 | 139 | 33.71 | 8.31 | ||||

| 12-Month | 132 | 32.49 | 7.78 | 131 | 33.27 | 8.46 | ||||

| Smoking1 | 5.65 | 2 | 0.06 | |||||||

| Baseline | 70 | 45.00 | - | 60 | 39.00 | - | ||||

| 6-Month | 65 | 45.00 | - | 49 | 35.00 | - | ||||

| 12-Month | 49 | 37.00 | - | 46 | 35.00 | - | ||||

| Composite Quality | 4.18 | 1 | 309 | 0.04 | ||||||

| Baseline | 156 | 0.70 | 0.11 | 155 | 0.71 | 0.12 | ||||

| 12-Month | 156 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 155 | 0.67 | 0.16 | ||||

(N, %, χ2, DF, P)

Moderator analyses were conducted to assess whether this outcome differed significantly by site or clinical characteristics. The moderator*group*time variables were not significant for study site, cardiovascular comorbidity, or smartphone ownership over time, suggesting that none of these variables moderated the main study effect. (see online supplement).

There were no clinically significant group*time interactions for the intervention versus usual care on self-reported coordination of chronic illness care, patient activation, or mental or physical health related quality of life. (Table 2) Scores for the patient activation measure and mental component summary of the SF-12 showed statistically significant improvement in both the intervention and control groups. (Table 3)

Table 3:

Study Outcomes: Within-Group Changes

| Intervention | Usual Care | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | P Value | N | Mean | SD | P Value |

| Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care | 0.35 | 0.58 | ||||||

| Baseline | 156 | 3.20 | 0.95 | 155 | 3.23 | 1.00 | ||

| 6-Month | 145 | 3.32 | 0.93 | 141 | 3.32 | 1.01 | ||

| 12-Month | 132 | 3.25 | 0.94 | 131 | 3.18 | 0.95 | ||

| Patient Activation Measure | 0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Baseline | 156 | 58.78 | 14.65 | 155 | 57.83 | 13.65 | ||

| 6-Month | 145 | 59.82 | 15.89 | 141 | 60.88 | 15.18 | ||

| 12-Month | 132 | 61.61 | 16.19 | 132 | 62.08 | 14.77 | ||

| SF-12 PCS | 0.16 | 0.70 | ||||||

| Baseline | 147 | 35.74 | 11.83 | 150 | 35.70 | 11.62 | ||

| 6-Month | 138 | 37.20 | 11.94 | 133 | 36.32 | 11.52 | ||

| 12-Month | 129 | 37.03 | 12.15 | 130 | 36.09 | 11.75 | ||

| SF-12 MCS | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Baseline | 147 | 35.50 | 12.54 | 150 | 36.55 | 13.25 | ||

| 6-Month | 138 | 39.16 | 13.48 | 133 | 38.70 | 13.18 | ||

| 12-Month | 129 | 41.68 | 14.04 | 130 | 41.16 | 11.61 | ||

| BMI | 0.12 | 0.32 | ||||||

| Baseline | 155 | 33.00 | 8.18 | 155 | 33.37 | 8.18 | ||

| 6-Month | 145 | 32.87 | 7.74 | 139 | 33.71 | 8.31 | ||

| 12-Month | 132 | 32.49 | 7.78 | 131 | 33.27 | 8.46 | ||

| Smoking1 | 0.07 | 0.75 | ||||||

| Baseline | 70 | 45.00 | - | 60 | 39.00 | - | ||

| 6-Month | 65 | 45.00 | - | 49 | 35.00 | - | ||

| 12-Month | 49 | 37.00 | - | 46 | 35.00 | - | ||

| Composite Quality | 0.86 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Baseline | 156 | 0.70 | 0.11 | 155 | 0.71 | 0.12 | ||

| 12-Month | 156 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 155 | 0.67 | 0.16 | ||

(N, %)

Discussion

The study found that a mobile personal health record was associated with a statistically significant but clinically modest differential benefit for quality of medical care in individuals with serious mental illness and cardiovascular comorbidity. There were not changes in self-reported outcomes including delivery of chronic illness care, patient activation, or mental or physical health related quality of life.

More than ¾ of participants in the intervention group used the mobile app at least weekly. Promoting regular use of personal health records has been challenging, with low rates of uptake attributed to cumbersome data entry and availability of the records.(45) In the current study, rates of use were relatively high, although this largely involved viewing results rather than actively entering or editing data such as health goals. Future research, including qualitative studies, should continue to delineate and help overcome the barriers to meaningful use of these technologies in populations with serious mental illness. Research should also examine the best roles for PHRs, which can support but are also dependent on patient engagement, versus health system-level approaches to integration of medical and psychiatric health information.

One feature in the current study that may have facilitated participants’ use of the PHR is the role of peer specialists in engaging participants in using the intervention. Clinical technology specialists, who provide training and supporting patients in the use of health IT interventions, have been proposed as a strategy for promoting uptake and ongoing use of mHealth interventions.(30). Peer specialists have particular expertise in supporting engagement in interventions and fostering positive health behavior change. (46) With appropriate training, these providers may be able to play a useful role in supporting implementation of mHealth interventions in populations with serious mental illness.(47)

The quality of medical services in the behavioral health homes was substantially higher than seen in usual care for community mental health centers (48) and the general population, (32) These findings provide evidence supporting the potential for behavioral health homes to deliver high quality of medical services to their patients with mental illness.(10) However, for the current study, it may also have created a ceiling effect limiting the ability to detect an impact of the intervention on quality of care as compared with mental health settings that do not have integrated medical services.(25)

Other secondary outcomes including health related quality of life and cardiovascular risk did not differ significantly between the intervention and usual care group. The study’s findings provide support to the observation from general populations that while mHealth interventions may be important facilitators of patient change, their use in isolation may have a more limited impact on distal health improvements. (49)

The findings should be interpreted in the light of several limitations. First, the project did not include a formal qualitative aim, limiting our ability to assess participants’ perspectives on the app and how it affected their service use. Second, while use of structured data collection forms were used to mitigate against potential bias, (50) it was not feasible to fully blind the reviewers for the chart review or patient interviews. Finally, the pragmatic design and broad inclusion criteria resulted in heterogeneity across patient and clinic characteristics, and may have reduced the ability to detect a larger effect of the mPHR.(51)

With the growing use of smartphones and patient portals for electronic health records, patients, including those with serious mental illness, will increasingly have easy access to their health records. The study’s findings suggest that particularly when used in integrated settings, that the incremental value of these interventions may be limited. More work is needed to understand how they can be incorporated into broader efforts to improve quality and outcomes of medical care in this population.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

This randomized study tested whether a mobile personal health record could improve quality of medical care for individuals treated in behavioral health homes that provide primary medical care onsite in mental health clinics.

We enrolled 311 participants with a serious mental illness and one or more cardiometabolic risk factor across two behavioral health homes to receive a mobile personal health record app. The mPHR provided participants with key information about diagnoses, medications, and lab values, and allowed them to track health goals.

At 12-month follow up, participants in the mPHR group had a statistically significant but clinically modest differential benefit for the intervention relative to the control group.

Acknowledgements:

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health R01MH100467. The sponsor provided financial support for the study only and had no role in the analysis and interpretation of the data or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mitchell AJ, Malone D, Doebbeling CC. Quality of medical care for people with and without comorbid mental illness and substance misuse: systematic review of comparative studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGinty EE, Baller J, Azrin ST, Juliano-Bult D, Daumit GL. Quality of medical care for persons with serious mental illness: a comprehensive review. Schizophr Res. 2015;165:227–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siantz E, Aranda MP. Chronic disease self-management interventions for adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone EM, Chen LN, Daumit GL, Linden S, McGinty EE. General Medical Clinicians’ Attitudes Toward People with Serious Mental Illness: A Scoping Review. The journal of behavioral health services & research. 2019:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horvitz-Lennon M, Kilbourne AM, Pincus HA. From silos to bridges: meeting the general health care needs of adults with severe mental illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25:659–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell AJ, Lord O. Do deficits in cardiac care influence high mortality rates in schizophrenia? A systematic review and pooled analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kugathasan P, Horsdal HT, Aagaard J, Jensen SE, Laursen TM, Nielsen RE. Association of Secondary Preventive Cardiovascular Treatment After Myocardial Infarction With Mortality Among Patients With Schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:1234–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alakeson V, Frank RG, Katz RE. Specialty care medical homes for people with severe, persistent mental disorders. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:867–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scharf DM, Eberhart NK, Schmidt N, Vaughan CA, Dutta T, Pincus HA, Burnam MA. Integrating Primary Care Into Community Behavioral Health Settings: Programs and Early Implementation Experiences. Psychiatr Serv. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Glick GE, Deubler E, Lally C, Ward MC, Rask KJ. Randomized Trial of an Integrated Behavioral Health Home: The Health Outcomes Management and Evaluation (HOME) Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy KA, Daumit GL, Stone E, McGinty EE. Physical health outcomes and implementation of behavioural health homes: a comprehensive review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fortuna KL, DiMilia PR, Lohman MC, Cotton BP, Cummings JR, Bartels SJ, Batsis JA, Pratt SI. Systematic Review of the Impact of Behavioral Health Homes on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors for Adults With Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2019:appips201800563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scharf D, Vaughan C, Eberhart N, Schmidt N, Dutta T, Burnham A: Inegrating primary care services in to behavioral health settings for persons with serious mental illness: first lessons learned from SAMHSA’s Primary and Behaviroal Health Care Integration (PBHCI) grants program. in PBHCI annual grantee presentation San Diego, CA2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roehrs A, da Costa CA, Righi RD, de Oliveira KS. Personal Health Records: A Systematic Literature Review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markle Foundation. PHR Adoption on the Rise; 1 in 10 Say TheyHave Electronic PHR,. 2011http://www.markle.org/sites/default/files/5_PHRs.pdf

- 16.Abd-alrazaq AA, Bewick BM, Farragher T, Gardner P. Factors that affect the use of electronic personal health records among patients: A systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J: Smart health: Concepts and status of ubiquitous health with smartphone in ICT Convergence (ICTC) 2011. pp. 388–389. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bender D, Sartipi K: HL7 FHIR: An Agile and RESTful approach to healthcare information exchange. in Proceedings of the 26th IEEE International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems, IEEE; 2013. pp. 326–331. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pew Research Center. Mobile technology fact sheet. 2019https://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/

- 20.Fortuna KL, Aschbrenner KA, Lohman MC, Brooks J, Salzer M, Walker R, George LS, Bartels SJ. Smartphone ownership, use, and willingness to use smartphones to provide peer-delivered services: results from a national online survey. Psychiatr Q. 2018;89:947–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dameff C, Clay B, Longhurst CA. Personal Health Records: More Promising in the Smartphone Era? JAMA. 2019;321:339–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robotham D, Mayhew M, Rose D, Wykes T. Electronic personal health records for people with severe mental illness; a feasibility study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ennis L, Robotham D, Denis M, Pandit N, Newton D, Rose D, Wykes T. Collaborative development of an electronic Personal Health Record for people with severe and enduring mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly EL, Braslow JT, Brekke JS. Using Electronic Health Records to Enhance a Peer Health Navigator Intervention: A Randomized Pilot Test for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness and Housing Instability. Community Ment Health J. 2018;54:1172–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Druss BG, Ji X, Glick G, von Esenwein SA. Randomized Trial of an Electronic Personal Health Record for Patients With Serious Mental Illnesses. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:360–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schinnar AP, Rothbard AB, Kanter R, Jung YS. An empirical literature review of definitions of severe and persistent mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1602–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40:771–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnall R, Rojas M, Bakken S, Brown W, Carballo-Dieguez A, Carry M, Gelaude D, Mosley JP, Travers J. A user-centered model for designing consumer mobile health (mHealth) applications (apps). Journal of biomedical informatics. 2016;60:243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorig K Action planning: a call to action. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:324–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ben-Zeev D, Drake R, Marsch L: Clinical technology specialists. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dinh TTH, Bonner A, Clark R, Ramsbotham J, Hines S. The effectiveness of the teach-back method on adherence and self-management in health education for people with chronic disease: a systematic review. JBI database of systematic reviews and implementation reports. 2016;14:210–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, Kerr EA. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shekelle PG, Kahan JP, Bernstein SJ, Leape LL, Kamberg CJ, Park RE. The reproducibility of a method to identify the overuse and underuse of medical procedures. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1888–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, Greene SM. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Med Care. 2005;43:436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glasgow RE, Whitesides H, Nelson CC, King DK. Use of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) with diabetic patients: relationship to patient characteristics, receipt of care, and self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2655–2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsai AC, Morton SC, Mangione CM, Keeler EB. A meta-analysis of interventions to improve care for chronic illnesses. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:478–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1005–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, Bullinger M, Kaasa S, Leplege A, Prieto L. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jenkinson C, Layte R, Jenkinson D, Lawrence K, Petersen S, Paice C, Stradling J. A shorter form health survey: can the SF-12 replicate results from the SF-36 in longitudinal studies? J Public Health. 1997;19:179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salyers MP, Bosworth HB, Swanson JW, Lamb-Pagone J, Osher FC. Reliability and validity of the SF-12 health survey among people with severe mental illness. Med Care. 2000:1141–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Little RJ. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American statistical Association. 1988;83:1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Multiplicity in randomised trials I: endpoints and treatments. Lancet. 2005;365:1591–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feise RJ. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2002;2:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang PC, Ash JS, Bates DW, Overhage JM, Sands DZ. Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:121–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sterling EW, von Esenwein SA, Tucker S, Fricks L, Druss BG. Integrating Wellness, Recovery, and Self-management for Mental Health Consumers. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46:130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fortuna KL, Brooks JM, Umucu E, Walker R, Chow PI. Peer support: a human factor to enhance engagement in digital health behavior change interventions. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science. 2019:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Compton MT, Rask KJ, Zhao LP, Parker RM. A Randomized Trial of Medical Care Management for Community Mental Health Settings: The Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:151–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel MS, Asch DA, Volpp KG. Wearable Devices as Facilitators, Not Drivers, of Health Behavior Change. JAMA. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gamerman V, Cai T, Elsäßer A. Pragmatic randomized clinical trials: best practices and statistical guidance. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2019;19:23–35. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kraemer HC, Frank E, Kupfer DJ. Moderators of treatment outcomes: clinical, research, and policy importance. JAMA. 2006;296:1286–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.