Abstract

Nicotine is only mildly rewarding, but after becoming dependent, it is difficult to quit smoking. The goal of these studies was to determine if low-nicotine cigarettes are less likely to cause dependence and enhance the reinforcing effects of nicotine than regular high-nicotine cigarettes. Male and female rats were exposed to tobacco smoke with a low or high nicotine level for 35 days. It was investigated if smoke exposure affects the development of dependence, anxiety- and depressive-like behavior, and nicotine-induced behavioral sensitization. Smoke exposure did not affect locomotor activity in a small open field or sucrose preference. Mecamylamine precipitated somatic withdrawal signs in male rats exposed to smoke with a high level of nicotine, but not in male rats exposed to smoke with a low level of nicotine or in females. After cessation of smoke exposure, there was a small decrease in sucrose preference in the male rats, which was not observed in the females. Cessation of smoke exposure did not affect anxiety-like behavior in the large open field or the elevated plus maze test. Female rats displayed less anxiety-like behavior in both these tests. Repeated treatment with nicotine increased locomotor activity, rearing, and stereotypies. Prior exposure to smoke with a high level of nicotine increased nicotine-induced rearing in the females. These findings indicate that exposure to smoke with a low level of nicotine does not lead to dependence and does not potentiate the effects of nicotine. Exposure to smoke with a high level of nicotine differently affects males and females.

Keywords: Tobacco smoke, dependence, withdrawal, low-nicotine cigarettes, anxiety, depression, rats

1. Introduction

Nicotine addiction is characterized by compulsive smoking, negative affective withdrawal signs upon smoking cessation, and relapse after periods of abstinence (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In the US, there are about 34 million people who smoke combustible cigarettes, and each year 480,000 people die due to smoking and second-hand smoke exposure (Creamer et al., 2019; HHS, 2014). Despite the adverse health effects of smoking, each day, almost 5,000 people start experimenting with cigarettes (SAMHSA, 2019). Most people start smoking at a young age and become addicted to nicotine quickly. Young people underestimate the addictive properties of nicotine, and they often believe that they can smoke for some time and then quit (Slovic, 2001). However, more than half the people who start smoking during adolescence still smoke as adults (Johnston et al., 2005; Malarcher et al., 2009).

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act provides the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with authority to regulate the manufacturing of cigarettes (FDA, 2018). The Tobacco Control Act allows the FDA to mandate lower nicotine levels in tobacco products and ban flavors. The FDA is considering reducing the amount of nicotine in cigarettes so that they become minimally addictive or even non-addictive (FDA, 2018). By setting new tobacco product standards, the FDA would like to achieve that young people do not become addicted to nicotine and help older smokers to quit smoking (FDA, 2018). Therefore, it is important to know if low-nicotine cigarettes are less addictive than conventional high-nicotine cigarettes. For ethical reasons, it cannot be investigated if low-nicotine cigarettes are less likely to cause dependence than regular cigarettes. However, clinical studies suggest that low-nicotine cigarettes may help people quit smoking. One study suggests that when people have only access to low-nicotine cigarettes, they smoke fewer cigarettes and have a lower level of dependence (Donny et al., 2015). Furthermore, people who use low nicotine cigarettes are more likely to make a quit attempt than people who use regular cigarettes (Donny et al., 2015; Piper et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2015). However, it has also been reported that high, but not low, nicotine-cigarettes decrease withdrawal symptoms, urges to smoke, and negative affect (Kamens et al., 2019). Therefore, it might be possible that heavy smokers who switch to low nicotine cigarettes experience withdrawal symptoms.

The goal of the present studies was to determine if low-nicotine cigarettes are less likely to cause dependence, negative affective states, and potentiate the reinforcing effects of nicotine than high-nicotine cigarettes. Therefore, we investigated the acute and long-term effects of exposure to smoke from SPECTRUM low- and high-nicotine cigarettes in males and females. Rats of both sexes were used because there is strong evidence for sex differences in the rewarding effects of nicotine and nicotine withdrawal (Flores et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2019). In our study, the rats were exposed to tobacco smoke for 4 h per day for 35 days. During the smoke exposure period, we investigated the development of dependence, locomotor activity, and sucrose preference. After the cessation of smoke exposure, we conducted tests for depressive-like behavior (sucrose preference and forced swim test) and anxiety-like behavior (large open field and elevated plus maze). Upon completion of these tests, it was investigated if pre-exposure to tobacco smoke affects the behavioral response to repeated injections with nicotine. The present studies suggest that low-nicotine cigarettes are less likely to cause dependence and long-term effects than regular cigarettes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male (n=36) and female (n=36) Wistar rats were purchased (Charles River, Raleigh, NC). The rats were socially housed (2 per cage) with a rat of the same sex in a climate-controlled vivarium on a reversed 12 h light-dark cycle (light off at 7 AM). Food and water were available ad libitum in the home cage. The experimental protocols were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Drugs and chemicals

Mecamylamine hydrochloride and (−)-nicotine hydrogen tartrate were purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and D-sucrose was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Mecamylamine and nicotine were dissolved in sterile saline (0.9 % sodium chloride) and administered subcutaneously (sc) in a volume of 1 ml/kg body weight. Mecamylamine doses are expressed as salt, and nicotine doses are expressed as base. To expose the rats to tobacco smoke, we used low-nicotine cigarettes with a yield of 0.07 mg/cig (NRC200) and high-nicotine cigarettes with a yield of 0.84 mg/cig (NRC600, NIDA Drug Supply Program). These cigarettes contain 600–700 mg of tobacco and have a nicotine concentration of 0.93 mg/g (NRC200) and 15.7 mg/g (NRC600)(Richter et al., 2016).

2.3. Experimental design

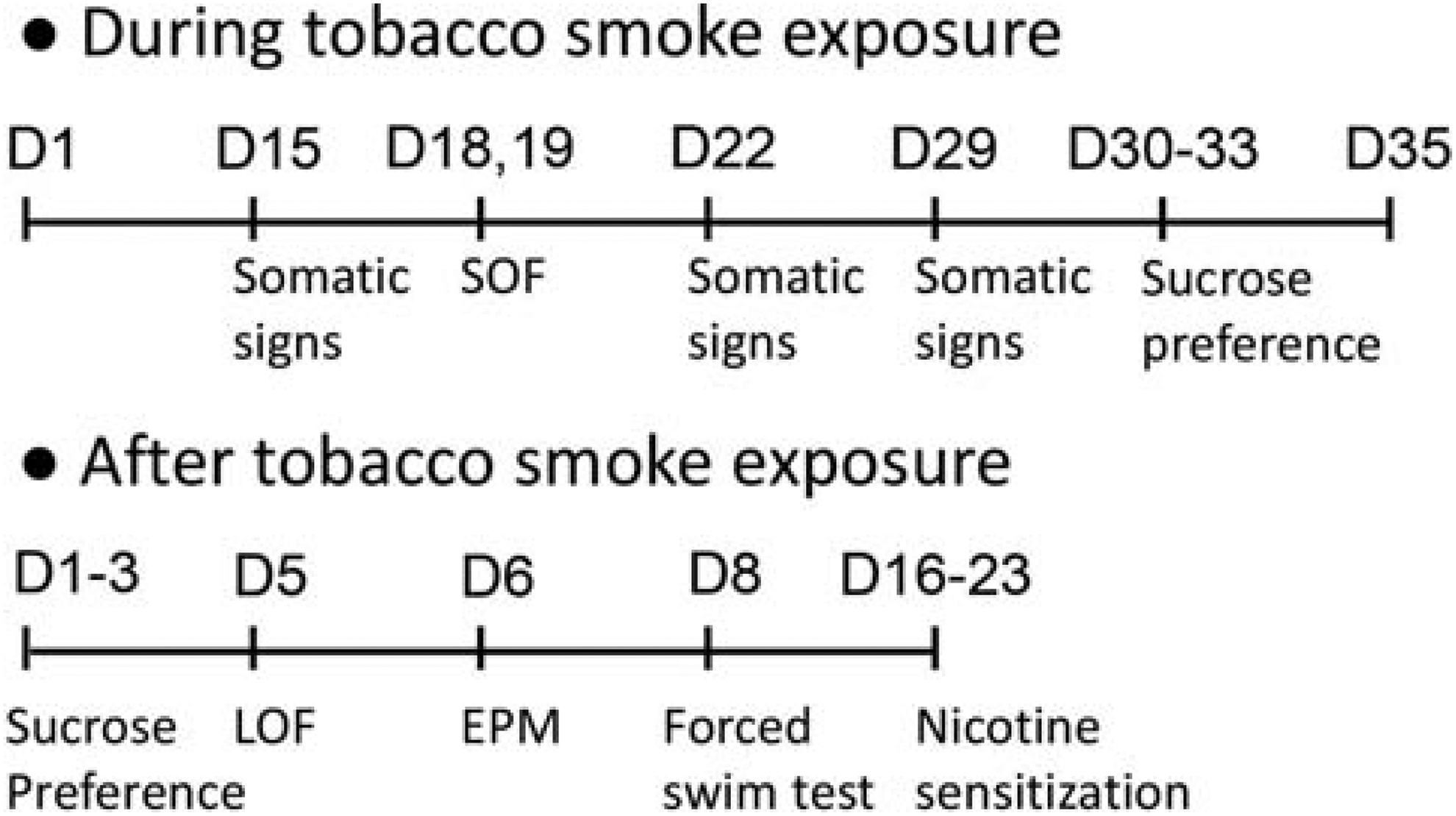

The rats were randomly divided into three groups (air-control, low-nicotine smoke, and high-nicotine smoke; n=12/group/sex, see Fig. 1 for a schematic overview of the experiment). The rats were exposed to tobacco smoke for 35 consecutive days. They were exposed to smoke twice a day; one 2-h session in the morning (9–11 AM) and one 2-h session in the afternoon (3–5 PM). On day 1 and 2, 12 cigarettes were burned per 2-h session (1 cigarette burned at a time), on day 3 and 4, 24 cigarettes were burned per 2-h session (2 cigarettes burned at a time), and on day 5–35, 36 cigarettes were burned per 2-h session (3 cigarettes burned at a time). Because some behavioral tests were conducted on the same days as the smoke exposure sessions, one smoke exposure session was conducted on day 14, 21,28, and 35 (morning session only), and one on day 15, 22, and 29 (afternoon session only). The body weights of the rats were measured daily throughout the experiment. During the smoke exposure period, somatic withdrawal signs, locomotor activity, and sucrose preference were determined. Somatic signs were recorded on days 15, 22, and 29. The rats were tested in a small open field on days 18 and 19, and the sucrose preference test was conducted on day 30–33. The rats were tested in the small open field for 15 min immediately after smoke exposure. Before the sucrose preference test, the rats were individually housed, and the test was conducted for three days. The sucrose solution was not available during the smoke exposure sessions. Smoke exposure was discontinued on day 35. After smoke exposure, we conducted the sucrose preference test (Day 1–3), large open field test (Day 5), elevated plus maze test (Day 6), forced swim test (Day 8), and determined the effects of smoke exposure on nicotine-induced behavioral sensitization in a small open field (Days 16–23). For the sensitization study, the rats of each experimental group were randomly divided into a nicotine and saline group (n=6/group/sex). The rats were placed in the small open field for 30 min and then received an injection with nicotine (0.4 mg/kg, sc) or saline for 6 days. Immediately after the 1st, 2nd, and 6th injection, locomotor activity, rearing, and stereotypies were measured for 60 min.

Figure 1. Schematic overview of the experiment.

The rats were exposed to cigarette smoke for 5 weeks (D1–35). Behavioral tests were conducted during and after cessation of smoke exposure. Abbreviations: D, day; LOF, large open field; SOF, small open field; EPM, elevated plus maze.

2.4. Tobacco smoke exposure

The rats were exposed to tobacco smoke, as described in our previous studies (Bruijnzeel et al., 2011; Small et al., 2010; Yamada et al., 2010). Briefly, the rats were placed in clean rodent cages (3 rats/cage; 38 × 28 × 20 cm; length [L] × width [W] × height [H]) with corncob bedding and a wire bar lid. The rats were not restrained (whole-body exposure) during the tobacco smoke exposure sessions, and water and food were available. The rats were moved to the tobacco smoke exposure chamber (4 cages/chamber) immediately before the exposure sessions and returned to their home cages after the exposure sessions. Tobacco smoke was generated using a microprocessor-controlled cigarette smoking-machine (model TE-10, Teague Enterprises, Davis, CA). The smoke was generated by burning SPECTRUM research cigarettes using a standardized smoking procedure (35 cm3 puff volume, one puff per minute, 2 seconds per puff). Mainstream smoke and sidestream smoke were mixed and diluted. The smoke machine produced a mixture of 10% mainstream smoke and 90% sidestream smoke, based on total suspended particle (TSP) matter. The smoke was aged for 2–4 min and diluted with air before being introduced into the exposure chambers. The exposure conditions were monitored for carbon monoxide (CO) and TSP. CO levels were assessed using a continuous CO analyzer that measures CO levels between 0–2000 parts per million (Monoxor II, Bacharach, New Kensington, PA USA). Smoke was pumped out of the exposure chamber into a chemical hood through a pre-weighed filter (Pallflex Emfab Filter, Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY USA) for 5 min to measure the TSP count. The TSP count per cubic meter was calculated by dividing the weight increase of the filter by the volume of the smoke. The TSP and CO level depends on the number of cigarettes that are burned during one 10-min round (i.e., burned at one time). Increasing the number of cigarettes per round leads to higher TSP levels. In this study, 1 to 3 cigarettes were burned per round, which leads to TSP level of 20–80 mg/m3 and CO levels of 100–450 ppm.

2.5. Behavioral tests

2.5.1. Somatic withdrawal signs

Somatic signs were observed in transparent Plexiglas observation chambers (25 cm × 25 cm × 46 cm; L × W × H) with 0.5 cm of corncob bedding (Bruijnzeel et al., 2010; Tan et al., 2019). The rats were habituated to the observation chambers for 5 min/day on 3 consecutive days before testing. On the test day, the rats were injected with mecamylamine (2 mg/kg, sc). Ten minutes after the mecamylamine injections, the rats were placed in the observation chamber, and somatic withdrawal signs were recorded for 10 min. The following signs were recorded: body shakes, head shakes, cheek tremors, chews, teeth chattering, gasps, writhes, ptosis, genital licks, foot licks, and yawns (Malin and Goyarzu, 2009). Ptosis was counted once per minute if present continuously. Somatic signs were observed in a quiet, brightly lit room. The total number of somatic signs was the sum of the individual occurrences.

2.5.2. Sucrose preference test

The sucrose preference test was used to determine if smoke exposure leads to a brain reward deficit (anhedonia-like behavior) in rodents (Willner et al., 1987). The test was done using a two-bottle choice procedure, as described in our previous work (Bruijnzeel et al., 2019). The sucrose solution (2%, w/v) was prepared daily with autoclaved water. The rats were individually housed, and one bottle (180 ml, Kaytee Chew Proof bottle) with water and one bottle with a sucrose solution (2%, w/v) were placed on top of the home cage. The bottles were switched (left/right position) daily to reduce the side bias. The weight of each bottle was recorded before and after the choice test. Fluid intake was not corrected for spillage. The difference in bottle weights was used to measure water and sucrose intake. Sucrose preference (percentage) was calculated using the following formula: (sucrose intake/ total fluid intake) × 100.

2.5.3. Small open field test

The small open field test was performed to assess locomotor activity, rearing, and stereotypies (Bruijnzeel et al., 2016; Qi et al., 2016). Horizontal and vertical beam breaks were measured using an automated animal activity cage system (VersaMax Animal Activity Monitoring System, AccuScan Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA). Horizontal beam breaks reflect locomotor activity, and vertical beam breaks reflect rearing. Repeated interruption of the same beam is considered a measure of stereotypies (Febo et al., 2003; Hayashi et al., 2007). The setup consisted of four animal activity cages made of clear acrylic (40 cm × 40 cm × 30 cm; L × W × H), with 16 equally spaced (2.5 cm) infrared beams across the length and width of the cage. They were located 2 cm above the cage floor (horizontal activity beams). An additional set of 16 infrared beams was located 16 above the cage floor (vertical activity beams). All beams were connected to a VersaMax analyzer, which sent information to a computer that displayed beam data through Windows-based software (VersaDat software). The small open field test was conducted in a dark room, and the cages were cleaned with a Nolvasan solution (chlorhexidine diacetate) between animals. Each rat was placed in the center of the open field, and activity was measured for 15 or 90 min.

2.5.4. Elevated plus maze test

The elevated plus maze test is used to measure the anxiety-like behavior in rodents (Walf and Frye, 2007), and was performed as described before (Qi et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2019). The elevated plus maze (Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, PA) consists of two open arms (i.e., without walls; 50 cm × 10 cm; L × W) and two closed arms (i.e., with black color walls, 50 cm × 10 cm × 30 cm; L × W × H). The open and closed arms were connected by a central platform, and the open arms had 0.5 cm ledges to prevent the rats from falling off the maze. The open arms were placed opposite of each other, and the maze was elevated 55 cm above the floor on the acrylic legs. The rats were placed in the central area facing an open arm and allowed to explore the apparatus for 5 min. Their behavior was recorded with a camera that was mounted above the maze. The test was conducted in a quiet, dimly lit room. The duration in the open arms and closed arms, number of open and closed arm entries, and total distance traveled were determined automatically (center-point detection) using EthoVision XT 11.5 software (Noldus Information Technology, Leesburg, VA). The apparatus was cleaned with a Nolvasan solution between tests.

2.5.5. Large open field test

The large open field test is another test widely used to assess the anxiety-like behavior in rodents (Liebsch et al., 1998; Prut and Belzung, 2003). This test was conducted as described in our previous work (Qi et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2019). The open field apparatus is a large arena measuring 120 × 120 × 60 cm (L × W × H) and is placed in a brightly lit (500 lux) room. The arena is made of black high-density polyethylene panels that are fastened together and placed on a black plastic bottom plate (Faulkner Plastics, Miami, FL). The rats’ behavior was recorded with a camera mounted above the arena and analyzed automatically (center-point detection) with EthoVision XT 11.5 software (Noldus Information Technology, Leesburg, VA). The open field was divided into two zones: a border zone (20 cm wide) and a center zone (60 × 60 cm; L × W). The following behaviors were analyzed: duration in border zone and center zone and distance traveled in border and center zone. The open field was cleaned with a Nolvasan solution between tests.

2.5.6. Forced swim test

The forced swim test is used to assess the depressive-like behavior in rodents (Detke et al., 1995; Slattery and Cryan, 2012). This test was conducted as described in our previous work (Bruijnzeel et al., 2019). The test consisted of two stages. First, a 15-min pre-test is conducted, and that is followed by a 5-min test 24 h later. Immediately before each test, a large Pyrex cylinder (21×46 cm; Fisher Scientific) was filled with 30 cm of tap water (23–25° C). The 5-min test session was recorded with a digital camcorder that was positioned 1 m above the cylinder. An experienced observer who was blind to the treatment conditions scored the behavior from the recordings. Three behaviors were scored continuously: immobility, swimming, and climbing. Swimming was defined as horizontal movements across the cylinder. Climbing was defined as the upward-directed movement of forepaws against the cylinder wall. Immobility was defined as the rat floating in the water and made only the small movements necessary to keep their heads above the water. Immediately after each session, rats were removed from the water and dried with a clean towel and returned to their home cages. After each test swim, the cylinders were cleaned and again filled with water.

2.6. Statistics

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 and GraphPad Prism version 8.4. The body weights were analyzed using a three-factor ANOVA, with exposure condition (air, low-nicotine smoke, and high-nicotine smoke) and sex as between-subjects factors, and day as within-subjects factor. Behavioral data were analyzed using two-factor ANOVA, with smoke exposure condition and sex as between-subjects factors. For all statistical analyses, significant interactions in the ANOVA were followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc tests to determine which groups differed from each other. P-values less or equal to 0.05 were considered significant. Significant main effects, interactions, and post hoc comparisons are reported in the Results section.

3. Results

3.1. Body weights

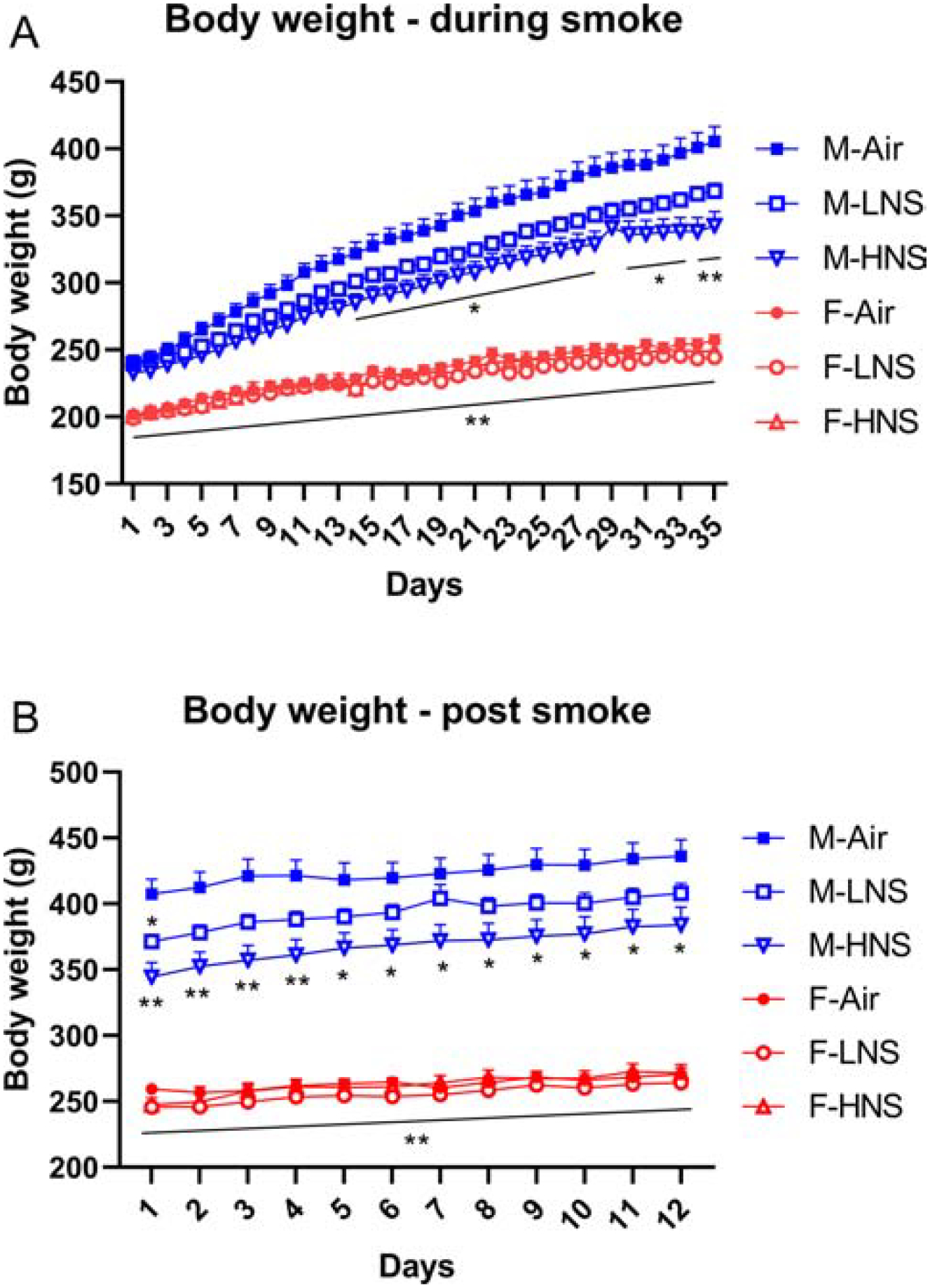

Before the start of the smoke exposure sessions, the females weighed less than the males (males 208 ± 2 g and females 196 ± 2 g; Sex, F1,66=17.24, p<0.0001). During the smoke exposure period, the males gained more weight than the females (Sex, F1,66=329.29, p<0.0001; Time, F34,2244=1254,22, p<0.0001; Time × Sex, F34,2244=287.91, p<0.0001; Fig. 2A). Exposure to tobacco smoke decreased body weight gain in the males but not in the females (Time × Sex × Treatment, F68,2244=6.98, p<0.0001; Treatment, F2,66=7.36, p<0.01; Time × Treatment, F68,2244=9.47, p<0.0001; Sex × Treatment, F2,66=5.13, p<0.01). A similar pattern of results was observed when the body weights were expressed as a percentage of the pre-smoke exposure baselines (Fig. S1). The males gained more weight than the females during the smoke exposure period (Sex, F1,66=574.76, p<0.0001; Time, F34,2244=1251,45, p<0.0001; Time × Sex, F34,2244=259.01, p<0.0001). Furthermore, smoke exposure reduced body weight gain in the males but not in the females (Time × Sex × Treatment, F68,2244=6.48, p<0.0001; Treatment, F2,66=15.62, p<0.0001; Time × Treatment, F68,2244=8.98, p<0.0001; Sex × Treatment, F2,66=10.20, p<0.0001). After the smoke exposure sessions, the males and females gained weight but the males gained more weight than the females (Time, F11,726= 137.03, p<0.0001; Sex, F1,66= 422.61, p<0.0001; Time × Sex, F11,726= 11.94, p<0.0001; Fig. 2B). The male rats that had been exposed to smoke continued to weigh less than the male rats that had not been exposed to smoke (Treatment, F2,66= 6.45, p<0.01; Time × Treatment, F22,726= 3.78, p<0.0001; Sex × Treatment, F2,66= 5.83, p<0.01).

Figure 2. Exposure to tobacco smoke with a high level of nicotine lowers body weight gain in male rats.

Bodyweight gain during the smoke exposure sessions (A), and after the cessation of smoke exposure (B). Asterisks indicate lower body weights compared to the male air-controls. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. N=12/group/sex. Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; LNS, low-nicotine smoke; HNS, high-nicotine smoke. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

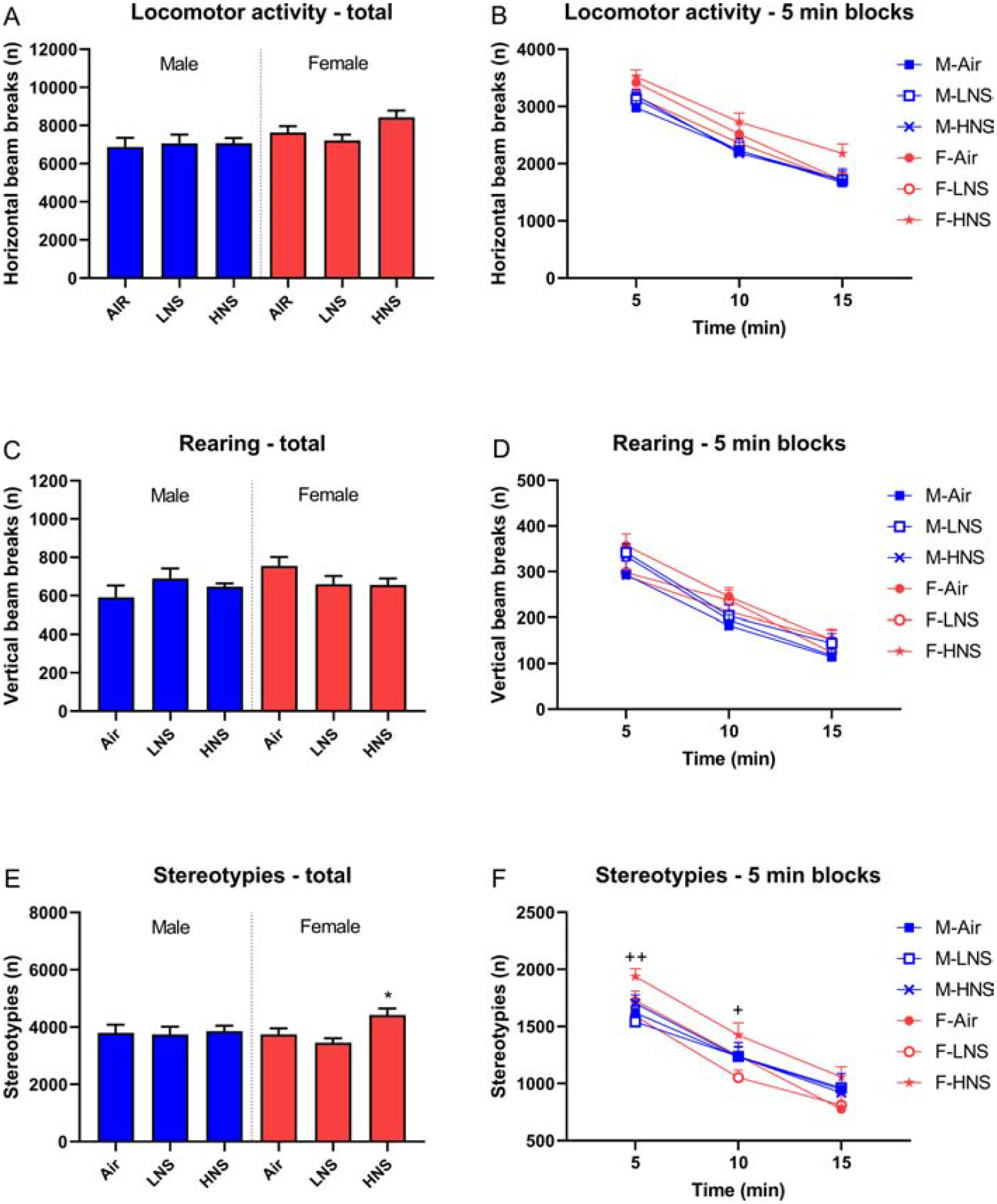

3.2. Small open field

The rats were tested in the small open field on Day 18 and 19 of smoke exposure. Locomotor activity decreased over time (5-min blocks) and the females were more active than the males (Time, F2,132=283.99, p<0.0001; Sex, F1,66=6.07, p<0.05; Fig. 3A, B). Rearing also decreased over time (Time, F2,132=189.34, p<0.0001; Fig. 3C, D). Stereotypes decreased over time and this decrease differed by sex (Time, F2,132=210.54, p<0.0001; Time × Sex, F2,132=3.34, p<0.05; Fig. 3E, F). The posthoc showed that the female rats exposed to smoke with a high level of nicotine displayed more stereotypies than females exposed to smoke with a low level of nicotine and the air-control females.

Figure 3. Exposure to tobacco smoke and behavior in a small open field.

Rats were tested in the small open field after smoke exposure and locomotor activity (A, B), rearing (C, D), and stereotypies (E, F) were recorded. Asterisks indicate more stereotypies compared to female air-control rats. Plus signs indicate more stereotypies compared to female rats exposed to smoke with a low level of nicotine. N=12/group/sex. *,+ p<0.05, **,++ p<0.01. Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; LNS, low-nicotine smoke; HNS, high-nicotine smoke. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

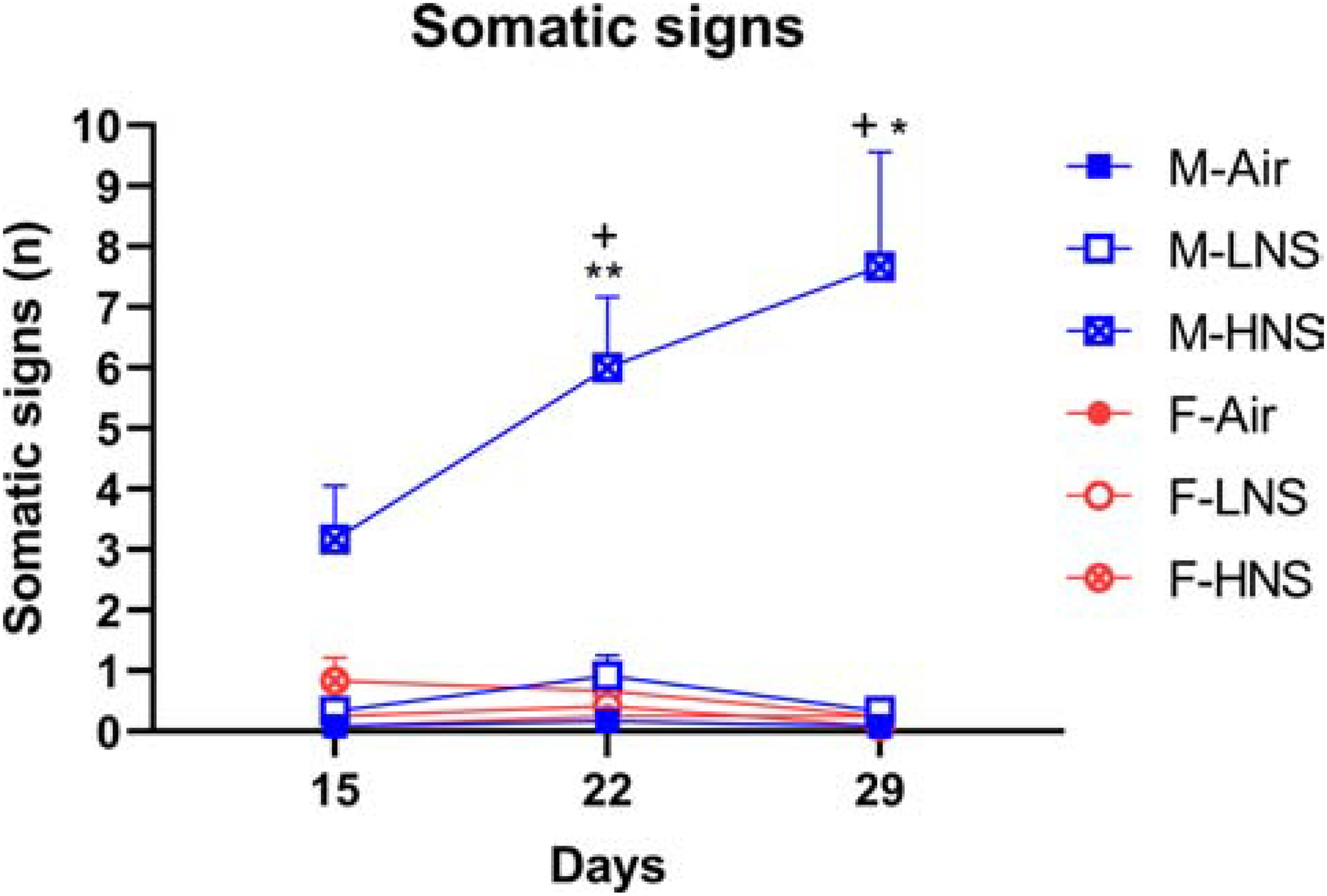

3.3. Somatic signs

The somatic signs were counted on days 15, 22, and 29 of smoke exposure. The somatic signs increased over time (F2,132=5.12, p<0.01, Fig. 4), and the number of signs increased more in the male high-nicotine smoke group than in the other groups (Time × Sex, F2,132=7.10, p<0.01; Time × Treatment, F4,132=4.24, p<0.01; Time × Sex × Treatment, F4,132=6.96, p<0.0001; Sex, F1,132=18.55, p<0.0001; Treatment, F2,132=21.85, p<0.0001). The posthoc showed that the males exposed to smoke with a high level of nicotine displayed more somatic withdrawal signs than all other groups.

Figure 4. Somatic withdrawal signs in male rats exposed to smoke with a high level of nicotine.

Mecamylamine increased withdrawal signs in male rats exposed to smoke with a high level of nicotine, but not in male rats exposed to smoke with a low level of nicotine or females. Plus-signs indicate higher levels compared to male rats in the same exposure group on Day 15. N=12/group/sex. Asterisks indicate higher levels compared to male air-control rats with the same dose of mecamylamine. *, + p<0.05, ** p<0.01. Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; LNS, low-nicotine smoke; HNS, high-nicotine smoke. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

3.4. Sucrose preference

Sucrose preference was determined during smoke exposure sessions and on the first two days after cessation of smoke exposure. During the smoke exposure sessions, there was no effect of sex or smoke exposure on sucrose preference (Table 1). On the first day after smoke exposure, sucrose preference was slightly decreased in the male rats (Sex × Treatment, F2,71=29.13, p<0.05). The posthoc tests did not reveal any significant differences between the groups. On the second day after smoke exposure, there was no effect of sex or smoke treatment on sucrose preference.

Table 1.

Exposure to tobacco smoke does not affect sucrose preference.

| Treatments | Sucrose preference % | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |

| During tobacco smoke exposure | ||

| Air | 96.1 ± 0.7 | 93.9 ± 1.1 |

| Low nicotine smoke | 92.6 ± 2.5 | 95.0 ± 0.5 |

| High nicotine smoke | 89.4 ± 1.5 | 91.8 ± 3.3 |

| Withdrawal Day 1 | ||

| Air | 97.7 ± 0.5 | 95.3 ± 1.1 |

| Low nicotine smoke | 94.5 ± 1.1 | 96.5 ± 0.7 |

| High nicotine smoke | 96.3 ± 0.7 | 96.0 ± 0.8 |

| Withdrawal Day 2 | ||

| Air | 97.6 ± 0.6 | 95.1 ± 2.5 |

| Low nicotine smoke | 97.3 ± 0.6 | 97.3 ± 0.5 |

| High nicotine smoke | 95.9 ± 0.7 | 98.0 ± 0.5 |

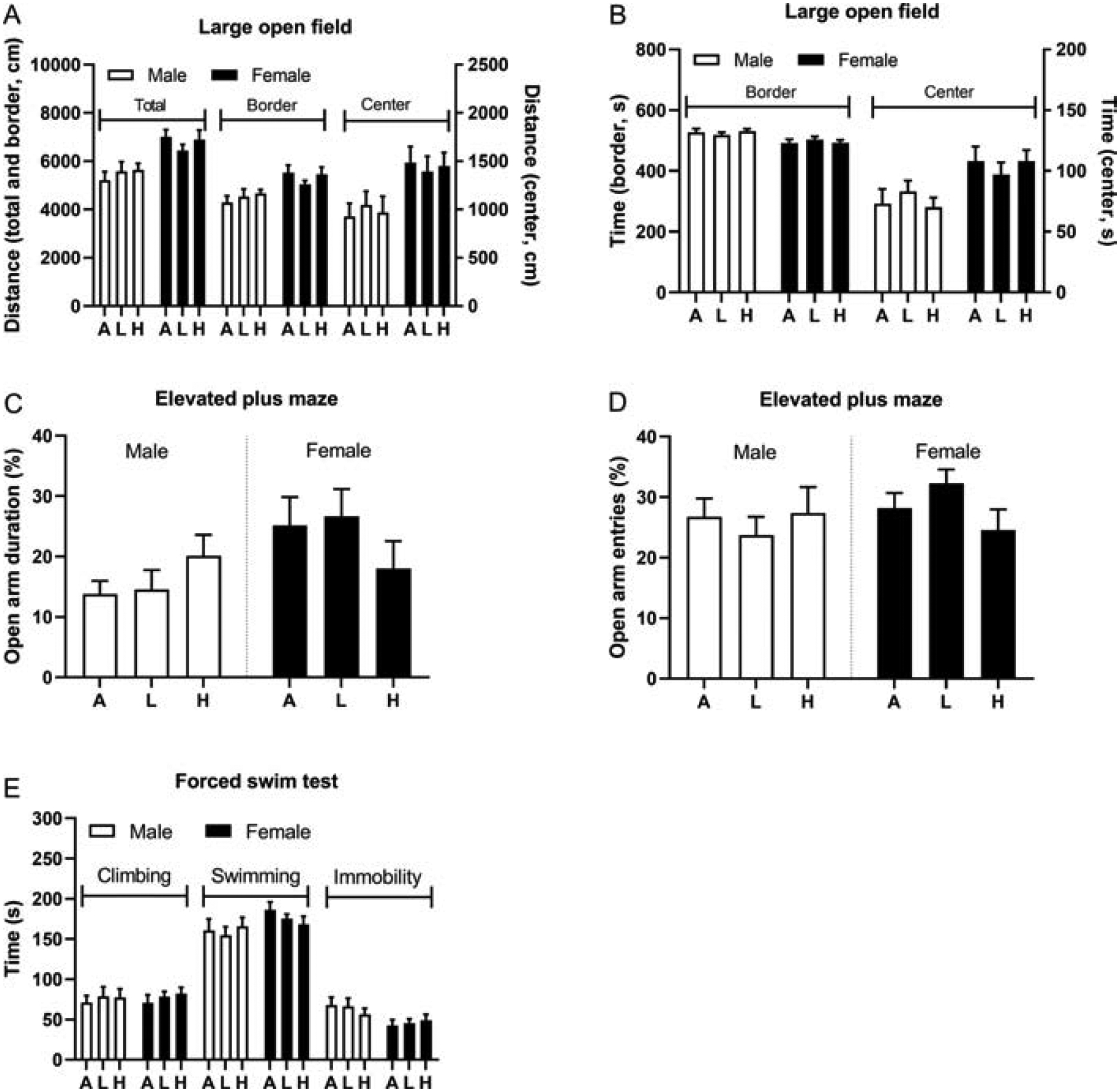

3.5. Large open field

There was no effect of smoke exposure on locomotor activity in the large open field (Fig. 5A). However, there were sex differences in the distance traveled. The females traveled a greater distance than the males (F1,66=23.45, p<0.05). The females traveled a greater distance in the border zone (F1,66=15.29, p<0.05) and in the center zone (F1,66=13.91, p<0.05). The males spent more time than the females in the border zone (F1,66=12.67, p<0.01), and the females spent more time in the center zone (F1,66=12.71, p<0.01, Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Exposure to tobacco smoke does not affect behavior in the elevated plus maze test, large open field, and forced swim test.

Male and female rats were exposed to tobacco smoke and tested in the large open field (A, B) elevated plus maze (C, D) and forced swim test (E). N=12/group/sex. Abbreviations: A, air; L, low-nicotine smoke; H, high-nicotine smoke. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

3.6. Elevated plus maze

There was no effect of smoke exposure on any of the measures in the elevated plus maze test (Fig. 5C, D). There were, however, sex differences, such that the females spent a greater percentage of time on the open arms (F1,66=5.08, p<0.05). The males and the females spent the same amount of time on the open arms (Fig. S2A), but the females made more open arm entries (F1,66=27.95, p<0.0001; Fig. S2B). The females spent less time in the closed arms than the males (F1,66=8.38, p<0.01; Fig. S2C), and made more closed arm entries (F1,66=104.07, p<0.0001; Fig. S2D). The females traveled a greater distance on the elevated plus maze than the males (F1,66=89.88, p<0.0001; Fig. S2E).

3.7. Forced swim test

There was no effect of smoke exposure on the behavior of the rats in the forced swim test (Fig. 5E). There were, however, sex differences. The female rats displayed less immobility than the males (F1,66=7.61, p<0.01). There were no significant sex differences in climbing and swimming behavior.

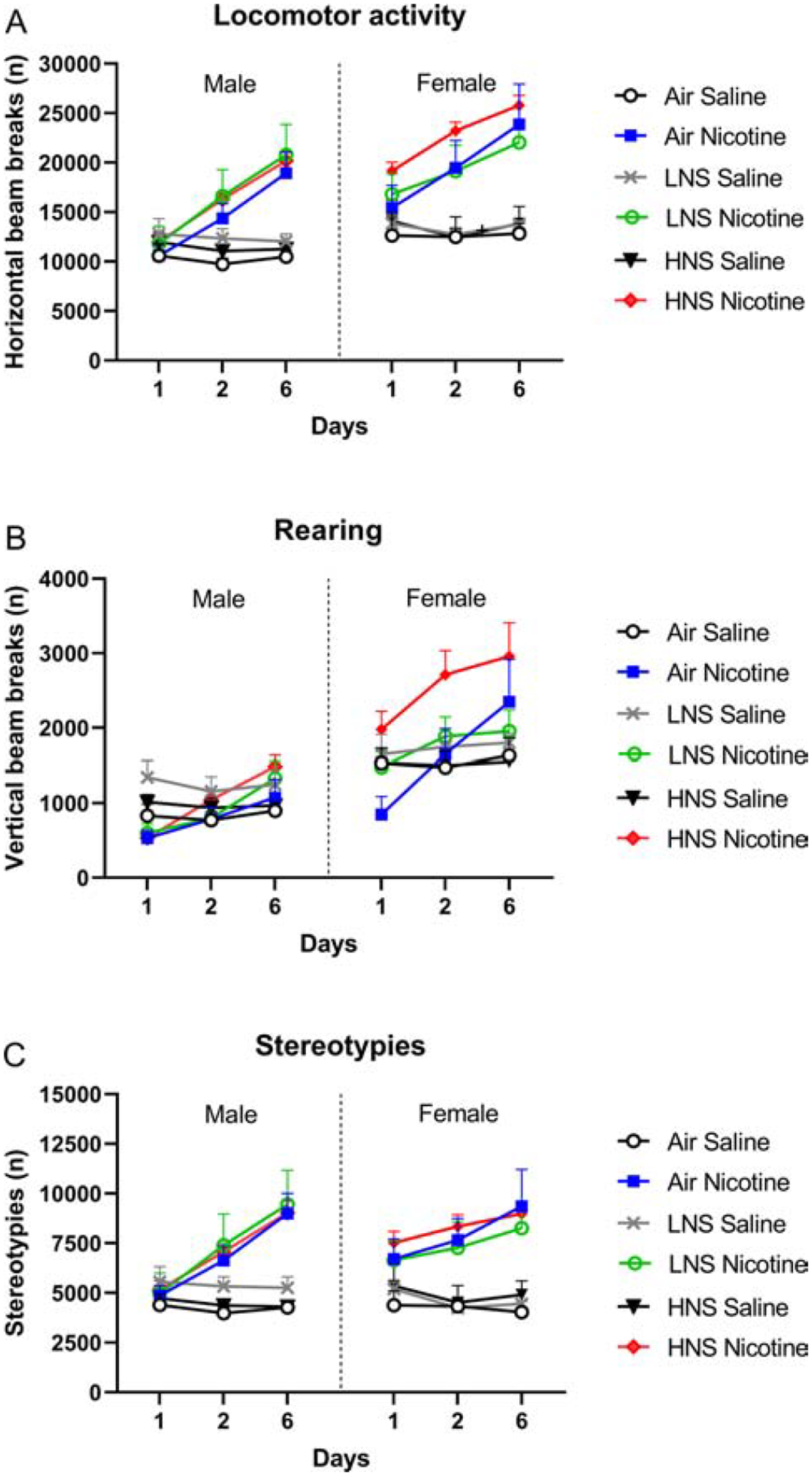

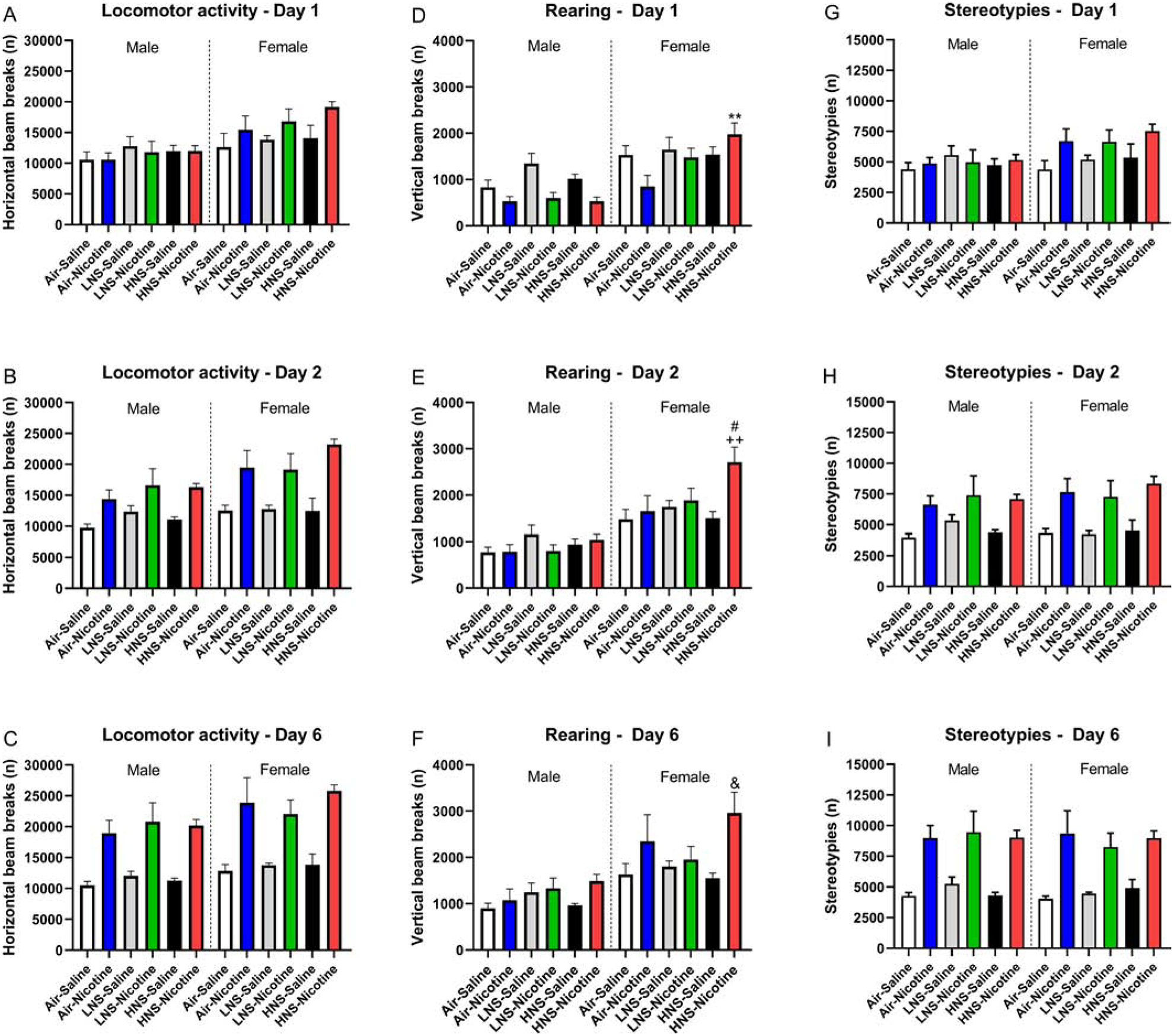

3.8. Nicotine treatment and small open field

The females had a higher level of locomotor activity than the males, and the nicotine-treated rats had a higher level of activity than the saline-treated rats (Sex, F1,60=13.66, p<0.0001; Nicotine treatment, F1,60=42.59, p<0.0001; Fig. 6A, 7A–C). Locomotor activity increased over time (days 1, 2, and 6) in the nicotine-treated rats (Time, F2,120=55.39; Time × Nicotine treatment, F2,120=64.54 p<0.0001). A separate analysis was conducted for days 1, 2, and 6. The females had a higher level of locomotor activity on days 1, 2, and 6 (Day-1 Sex, F1,60=16.70, p<0.0001; Day-2 Sex, F1,60=11.31, p<0.01; Day-6 Sex, F1,60=7.89, p<0.01). On day 1, nicotine increased locomotor activity in the females but not in the males (Sex × Nicotine treatment, F1,60=4.72, p<0.05). Nicotine increased locomotor activity in the males and females on days 2 and 6 (Day-2 Nicotine treatment, F1,60=45.63, p<0.0001; Day-6 Nicotine treatment, F1,60=76.47, p<0.0001).

Figure 6. Sensitization of behavioral responses after a history of smoke exposure.

Rats were tested in the small open field after the first, second, and sixth nicotine injection. Horizontal beam breaks (A), vertical beam breaks (B), and stereotypies (C) were recorded. N=6/group/sex. Abbreviations: LNS, low-nicotine smoke; HNS, high-nicotine smoke. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Figure 7. Gradual increase in behavioral response after repeated exposure to nicotine.

Rats were tested in the small open field after the first, second, and sixth nicotine injection. Horizontal beam breaks (A-C), vertical beam breaks (D-F), and stereotypies (G-I) were recorded. D) Asterisks indicate increased vertical beam breaks compared to the female air-nicotine group. E) Plus signs indicated increased vertical beam breaks compared to the female air-saline group and HNS-saline group, pound signs indicate increased vertical beam breaks compared to the female Air-nicotine and LNS saline group. F) Ampersand sign indicates increased vertical beam breaks compared to the female HNS nicotine group. N=6/group/sex. Abbreviations: LNS, low-nicotine smoke; HNS, high-nicotine smoke. &, # p<0.05; **, ++ p<0.01. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Treatment with nicotine led to an increase in rearing over time (Time, F2,120=33.98, p<0.0001; Time × Nicotine treatment, F2,120=30.18, p<0.0001; Fig. 6B, 7D–F). The females displayed more rearing than the males, and the effect of nicotine on rearing was greater in rats that had been exposed to tobacco smoke and in the females (Sex, F1,60=54.23, p<0.0001; Sex × Nicotine treatment, F1,60=4.71, p<0.05; Smoke treatment × Nicotine treatment, F2,60=3.36, p<0.05). When a separate analysis was conducted for day 1, 2, and 6, it was shown that on all test days the females displayed more rearing than the males (Day-1 Sex, F1,60=41.99, p<0.0001; Day-2 Sex, F1,60=61.10, p<0.0001; Day-6 Sex, F1,60=31.08, p<0.0001). Exposure to tobacco smoke increased the nicotine-induced increase in rearing the females on day 1 (Smoke treatment, F2,60=4.22, p<0.05; Nicotine treatment, F1,60=9.16, p<0.01; Sex × Smoke treatment × Nicotine treatment, F2,60=3.32, p<0.05). Smoke exposure also potentiated nicotine-induced rearing in the females on day 2 (Smoke treatment, F2,60=3.55, p<0.05; Sex × Nicotine treatment, F1,60=6.37, p<0.05), but on the sixth day no effect of prior smoke exposure was observed (Nicotine treatment, F1,60=10.54, p<0.01). The posthoc analyses show that exposure to smoke with a high, but not low, level of nicotine increased nicotine-induced rearing in the females (Figs 7D–F).

The number of nicotine-induced stereotypies increased over time and this effect was most pronounced in the nicotine-treated male rats (Time, F2,120=28.06, p<0.0001; Nicotine treatment, F1,60=42.30, p<0.0001; Time × Sex, F2,120=6.15, p<0.01; Time × Nicotine treatment, F2,120=46.35, p<0.0001; Time × Sex × Nicotine treatment, F2,120=4.01, p<0.05; Fig. 6C, 7G–I). The larger increase in stereotypies in the male rats was because the females treated with nicotine already had a high level of stereotypies during the first session. Prior exposure to smoke did not affect the stereotypies. A separate analysis was conducted for days 1, 2, and 6. On the first day, nicotine increased stereotypies in the females but not in the males (Sex, F1,60=5.52, p<0.05; Nicotine treatment, F1,60=5.75, p<0.05; Sex × Nicotine treatment, F1,60=4.61, p<0.05). On the second and sixth treatment day, nicotine increased stereotypies in both the males and the females (Day-2 Nicotine treatment, F1,60=40.22, p<0.0001; Day-6 Nicotine treatment, F1,60=69.78, p<0.0001).

4. Discussion

The goal of the present study was to investigate the acute and long-term effects of low- and high-nicotine smoke exposure in rats. The study showed that smoke exposure decreased body weight gain in the male but not in the female rats. The development of dependence was investigated by the administration of the nAChR antagonist mecamylamine to rats. Mecamylamine increased somatic withdrawal signs in the male rats that had been exposed to smoke with a high level of nicotine but notin male rats exposed to smoke with a low level of nicotine or in the female rats. In the first week after the cessation of smoke exposure, it was investigated if a history of smoke exposure affects anxiety- and depressive-like behavior. The male rats that had been exposed to smoke displayed a very small decrease in sucrose preference after the cessation of smoke exposure. Cessation of smoke exposure did not affect anxiety-like behavior in the large open field test or the elevated plus maze test and did not affect depressive-like behavior in the forced swim test. After the tests for anxiety and depressive-like behavior, it was determined if a history of smoke exposure affects the behavioral response to nicotine. Repeated nicotine administration increased locomotor activity, rearing, and stereotypies. A history of high-nicotine smoke exposure increased nicotine-induced rearing in the females but not in the males. Overall, these findings indicate that there are sex differences in the acute and long-term effects of tobacco smoke exposure. The males displayed more somatic withdrawal signs, and the females displayed an increased behavioral response to nicotine.

In the present study, plasma nicotine and cotinine levels were not determined. However, plasma nicotine and cotinine levels have been determined in several prior rodent smoke exposure studies. Exposure to smoke from 3R4F reference cigarettes (University of Kentucky, yield of 0.73 mg/cig) for several hours leads to high plasma nicotine (70–120 ng/ml) and cotinine levels (>500 ng/ml) in rats (de la Peña et al., 2014; Small et al., 2010). Plasma nicotine and cotinine levels in heavy smokers are about 35 and 300 ng/ml (Benowitz et al., 1982; Lawson et al., 1998; Wall et al., 1988). Therefore, nicotine levels that are similar or higher than those in smokers can be obtained by exposing rats to tobacco smoke. In the present study, the rats were exposed to smoke from SPECTRUM low- (NRC200) or high-nicotine (NRC600) cigarettes. In human smokers, there is a positive relationship between the nicotine yield of the SPECTRUM cigarettes and plasma nicotine levels (Kamens et al., 2019). In a previous study, we showed that exposure to smoke from high-nicotine cigarettes (NRC600) for 1 h leads to higher plasma nicotine levels (39 ng/ml) than exposure to smoke from low-nicotine cigarettes (7 ng/ml, NRC200)(unpublished observation). Therefore, exposure to smoke from high-nicotine cigarettes might have more severe long-term consequences than exposure to smoke from low-nicotine cigarettes. Indeed, the present findings indicate that exposure to smoke from high-nicotine cigarettes, but not low-nicotine cigarettes, mediates behavioral changes.

In the present study, we investigated the effects of smoke exposure on the development of nicotine dependence in male and female rats. It was shown that somatic signs gradually increased over time in the male rats that were exposed to tobacco smoke with a high level of nicotine. This suggests that the level of dependence increased over time. This is in line with clinical studies that show that a more prolonged smoking period leads to a higher level of nicotine dependence (Horn et al., 2003). This has important clinical implications because there is a positive relationship between withdrawal symptoms and relapse to smoking (Piasecki et al., 2003; West et al., 1989). Interestingly, we did not observe somatic withdrawal signs in the females that had been exposed to smoke with a high level of nicotine. This is in line with a previous study in which we compared mecamylamine-precipitated withdrawal signs between male and female rats (Tan et al., 2019). In that study, the rats were prepared with minipumps and chronically exposed to a high dose of nicotine. It is currently not well understood why precipitated somatic withdrawal signs are observed in males but not in females. Many studies have also reported that male rats and mice display more precipitated somatic opioid withdrawal signs than females (Craft et al., 1999; Kest et al., 2001; Radke et al., 2013). Furthermore, male rats and mice lose more weight during precipitated withdrawal than females (Cicero et al., 2002; Sadeghi et al., 2009). Although, precipitated nicotine withdrawal studies indicate that males display more somatic withdrawal signs than females, this is not observed in all studies during spontaneous withdrawal (Hamilton et al., 2009; Torres et al., 2013). One of the spontaneous withdrawal studies detected more somatic nicotine withdrawal signs in male than female rats (Torres et al., 2013). However, another study found that females display more somatic nicotine withdrawal signs than males in a dimly-lit environment but not in a brightly-lit environment (Hamilton et al., 2009). One limitation of the present study is that we only studied mecamylamine-precipitated somatic withdrawal signs. Mecamylamine is excreted in the urine, and there are sex differences in the renal elimination of drugs (Soldin et al., 2011). Furthermore, sex differences in the effect of mecamylamine on antinociception and brain reward function have been reported (Chi and de Wit, 2003; Chiari et al., 1999). Therefore, future studies may need to confirm our findings with other nAChR antagonists and investigate somatic withdrawal signs during spontaneous withdrawal from tobacco smoke. Importantly, the present study showed that in contrast to the male rats in the high-nicotine group, the males in the low-nicotine group did not display somatic withdrawal signs. This indicates the male rats exposed to smoke with a low level of nicotine do not develop dependence. This has important clinical implications because it suggests that lowering the nicotine content in cigarettes will decrease the number of people that becomes nicotine dependent.

It was also investigated if the cessation of tobacco smoke exposure leads to an increase in depressive- and anxiety-like behavior. Depressive-like behavior was investigated in the sucrose preference test on the first 2 days after smoke exposure and in the forced swim test 8 days after smoke exposure. In this study, there was a small decrease in sucrose preference in the male rats on the first day after smoke exposure. This suggests that cessation of smoke exposure might have led to some mild anhedonia in the male but not the female rats. It should be noted that the effect on sucrose preference was minimal (~3 percent decrease). Chronic mild stress leads to a 30 percent decrease in sucrose preference (Willner et al., 1987). Nicotine withdrawal also leads to a large decrease in sucrose preference. Withdrawal from a high dose of nicotine leads to a 30–40 percent decrease in sucrose preference during the first 2 days of nicotine withdrawal (Alkhlaif et al., 2017). In the present study, cessation of tobacco smoke exposure did not affect the behavior of the rats in the forced swim test. Therefore, our findings suggest that cessation of smoke exposure did not cause depressive-like state in the females and possible very mild depressive-like behavior in the males.

Anxiety-like behavior was investigated in the large open field test and the elevated plus maze test 5 and 6 days after the last smoke exposure session. There was no increase in anxiety-like behavior after cessation of smoke exposure. It might be possible that this was due to the time point at which anxiety-like behavior was investigated. Previous studies reported anxiety-like behavior on days 1 to 4 after the cessation of nicotine administration (Costall et al., 1990; Damaj et al., 2003; Pandey et al., 2001). One other study reported that adult rats do not display anxiety-like behavior in an elevated plus maze test and open field test several days after the cessation of smoke exposure (de la Peña et al., 2016). In contrast, adolescent rats displayed increased anxiety-like behavior after cessation of smoke exposure. Therefore, these findings suggest that adult rats do not display anxiety-like behavior after the cessation of smoke exposure. We found significant sex differences in anxiety-like behavior. In both the elevated plus maze test and the large open field test, the males displayed more anxiety-like behavior than the females. In the elevated plus maze test, the females spent a greater percentage of time on the open arms and made more open arm entries. In the large open field test, the females spent more time in the center of the open field, and they traveled a greater distance in the center of the open field. This is in line with previous studies that showed that males display more anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze test and large open field than females (Bruijnzeel et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2019).

We also investigated the effects of low- and high-nicotine smoke exposure on nicotine-induced behavioral sensitization in males and females. We studied the effects of a history of smoke exposure and nicotine on locomotor activity, rearing, and stereotypies. It is interesting to note that smoke exposure, nicotine-treatment, and sex differently affects locomotor activity, rearing, and stereotypies. Repeated administration of nicotine led to an increase in locomotor activity and this was not affected by a history of smoke exposure in the males or the females. On the first day of nicotine administration, nicotine differently affected the behavior of the males and the females. Nicotine increased locomotor activity in the females but not in the males. This suggests that females are more sensitive to the acute locomotor effects of nicotine than males. During the second and sixth session, nicotine increased locomotor activity to a similar degree in the males and the females. On a similar note, exposure to tobacco smoke did not affect stereotypies and nicotine-treatment differently affected stereotypies in the males and the females. Nicotine increased stereotypies in the females, but not males, on the first day of nicotine administration. However, after the second and sixth injection, a similar number of stereotypies was observed in the males and the females. Therefore, the females were more sensitive to the first injection, but the second and sixth injection had similar effects in the males and the females. In contrast to locomotor activity and stereotypes, tobacco smoke exposure affected rearing activity. Exposure to tobacco smoke with a high level of nicotine increased nicotine-induced rearing in the females. Furthermore, repeated treatment with nicotine led to an increase in rearing in the males and the females.

These findings indicate that exposure to tobacco smoke differently affects the behavior of male and female rats. Exposure to smoke with a high, but not low, level of nicotine led to dependence in male rats as indicated by precipitated somatic withdrawal signs. In the females, exposure to smoke with a high, but not low, level of nicotine increased nicotine-induced rearing. Exposure to smoke from low-nicotine cigarettes did not lead to the development of dependence and did not potentiate the effects of nicotine. These findings support the notion that low-nicotine cigarettes could lead to lower levels of nicotine dependence and smoking in young people.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Exposure to high-nicotine smoke leads to somatic withdrawal signs in male rats.

Exposure to high-nicotine smoke potentiates nicotine-induced rearing in female rats.

Exposure to low-nicotine smoke does not affect the behavior of male or female rats.

Repeated treatment with nicotine increases locomotor activity and rearing in rats.

Acknowledgments:

We thank the NIDA Drug Supply Program for providing the Nicotine Research Cigarettes.

Funding: This work was supported by a NIDA/NIH and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) grant (DA042530) and NIDA grant (DA046411) to AB. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Alkhlaif Y, Bagdas D, Jackson A, Park AJ, Damaj IM, 2017. Assessment of nicotine withdrawal-induced changes in sucrose preference in mice. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 161, 47–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Kuyt F, Jacob P III, 1982. Circadian blood nicotine concentrations during cigarette smoking. Clin.Pharmacol.Ther 32(6), 758–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnzeel AW, Bishnoi M, van Tuijl IA, Keijzers KF, Yavarovich KR, Pasek TM, Ford J, Alexander JC, Yamada H, 2010. Effects of prazosin, clonidine, and propranolol on the elevations in brain reward thresholds and somatic signs associated with nicotine withdrawal in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 212(4), 485–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnzeel AW, Knight P, Panunzio S, Xue S, Bruner MM, Wall SC, Pompilus M, Febo M, Setlow B, 2019. Effects in rats of adolescent exposure to cannabis smoke or THC on emotional behavior and cognitive function in adulthood. Psychopharmacology 236, 2773–2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnzeel AW, Qi X, Guzhva LV, Wall S, Deng JV, Gold MS, Febo M, Setlow B, 2016. Behavioral Characterization of the Effects of Cannabis Smoke and Anandamide in Rats. PloS one 11(4), e0153327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnzeel AW, Rodrick G, Singh RP, Derendorf H, Bauzo RM, 2011. Repeated pre-exposure to tobacco smoke potentiates subsequent locomotor responses to nicotine and tobacco smoke but not amphetamine in adult rats. Pharmacol.Biochem.Behav 100(1), 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H, de Wit H, 2003. Mecamylamine attenuates the subjective stimulant-like effects of alcohol in social drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 27(5), 780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiari A, Tobin JR, Pan H-L, Hood DD, Eisenach JC, 1999. Sex differences in cholinergic analgesia I: a supplemental nicotinic mechanism in normal females. Anesthesiology 91(5), 1447–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Nock B, Meyer ER, 2002. Gender-linked differences in the expression of physical dependence in the rat. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 72(3), 691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costall B, Jones B, Kelly M, Naylor R, Onaivi E, Tyers M, 1990. Ondansetron inhibits a behavioural consequence of withdrawing from drugs of abuse. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 36(2), 339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft R, Stratmann J, Bartok R, Walpole T, King S, 1999. Sex differences in development of morphine tolerance and dependence in the rat. Psychopharmacology 143(1), 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, Cullen KA, Day H, Willis G, Jamal A, Neff L, 2019. Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults—United States, 2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 68(45), 1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaj MI, Kao W, Martin BR, 2003. Characterization of spontaneous and precipitated nicotine withdrawal in the mouse. J.Pharmacol.Exp.Ther 307(2), 526–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Peña JB, Ahsan HM, Botanas CJ, Dela Pena IJ, Woo T, Kim HJ, Cheong JH, 2016. Cigarette smoke exposure during adolescence but not adulthood induces anxiety-like behavior and locomotor stimulation in rats during withdrawal. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 55, 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Peña JB, Ahsan HM, Botanas CJ, Sohn A, Yu GY, Cheong JH, 2014. Adolescent nicotine or cigarette smoke exposure changes subsequent response to nicotine conditioned place preference and self-administration. Behavioural brain research 272, 156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detke MJ, Rickels M, Lucki I, 1995. Active behaviors in the rat forced swimming test differentially produced by serotonergic and noradrenergic antidepressants. Psychopharmacology 121(1), 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Denlinger RL, Tidey JW, Koopmeiners JS, Benowitz NL, Vandrey RG, al’Absi M, Carmella SG, Cinciripini PM, Dermody SS, Drobes DJ, Hecht SS, Jensen J, Lane T, Le CT, McClernon FJ, Montoya ID, Murphy SE, Robinson JD, Stitzer ML, Strasser AA, Tindle H, Hatsukami DK, 2015. Randomized Trial of Reduced-Nicotine Standards for Cigarettes. The New England journal of medicine 373(14), 1340–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA, 2018. Tobacco product standard for nicotine level of combusted cigarettes. Fed Regist 83(52), 11818–11843. [Google Scholar]

- Febo M, Gonzalez-Rodriguez LA, Capo-Ramos DE, Gonzalez-Segarra NY, Segarra AC, 2003. Estrogen-dependent alterations in D2/D3-induced G protein activation in cocaine-sensitized female rats. Journal of neurochemistry 86(2), 405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores RJ, Uribe KP, Swalve N, O’Dell LE, 2019. Sex differences in nicotine intravenous self-administration: A meta-analytic review. Physiology & behavior 203, 42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton KR, Berger SS, Perry ME, Grunberg NE, 2009. Behavioral effects of nicotine withdrawal in adult male and female rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 92(1), 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi ML, Rao BS, Seo J-S, Choi H-S, Dolan BM, Choi S-Y, Chattarji S, Tonegawa S, 2007. Inhibition of p21-activated kinase rescues symptoms of fragile X syndrome in mice. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 104(27), 11489–11494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HHS, 2014. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General.

- Horn K, Fernandes A, Dino G, Massey CJ, Kalsekar I, 2003. Adolescent nicotine dependence and smoking cessation outcomes. Addictive behaviors 28(4), 769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, 2005. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2004: Volume I, Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 05–5727) National Institute on Drug Abuse, US Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Silva CP, Nye RT, Miller CN, Singh N, Sipko J, Trushin N, Sun D, Branstetter SA, Muscat JE, 2019. Pharmacokinetic profile of Spectrum reduced nicotine cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 22, 273–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kest B, Palmese CA, Hopkins E, Adler M, Juni A, 2001. Assessment of acute and chronic morphine dependence in male and female mice. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 70(1), 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson GM, Hurt RD, Dale LC, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Schroeder DR, Jiang NS, 1998. Application of serum nicotine and plasma cotinine concentrations to assessment of nicotine replacement in light, moderate, and heavy smokers undergoing transdermal therapy. J.Clin.Pharmacol 38(6), 502–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebsch G, Montkowski A, Holsboer F, Landgraf R, 1998. Behavioural profiles of two Wistar rat lines selectively bred for high or low anxiety-related behaviour. Behavioural brain research 94(2), 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malarcher A, Jones S, Morris E, Kann L, Buckley R, 2009. High School Students Who Tried to Quit Smoking Cigarettes: United States, 2007. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 58(16), 428–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin DH, Goyarzu P, 2009. Rodent models of nicotine withdrawal syndrome. Handb.Exp.Pharmacol 192, 401–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SC, Roy A, Xu T, Mittal N, 2001. Effects of protracted nicotine exposure and withdrawal on the expression and phosphorylation of the CREB gene transcription factor in rat brain. Journal of neurochemistry 77(3), 943–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB, 2003. Smoking withdrawal dynamics: II. Improved tests of withdrawal-relapse relations. Journal of abnormal psychology 112(1), 14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Drobes DJ, Walker N, 2019. Behavioral and subjective effects of reducing nicotine in cigarettes: A cessation commentary. Nicotine and Tobacco Research 21(Supplement_1), S19–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prut L, Belzung C, 2003. The open field as a paradigm to measure the effects of drugs on anxiety-like behaviors: a review. European journal of pharmacology 463(1–3), 3–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Guzhva L, Yang Z, Febo M, Shan Z, Wang KK, Bruijnzeel AW, 2016. Overexpression of CRF in the BNST diminishes dysphoria but not anxiety-like behavior in nicotine withdrawing rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 26, 1378–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke AK, Holtz NA, Gewirtz JC, Carroll ME, 2013. Reduced emotional signs of opiate withdrawal in rats selectively bred for low (LoS) versus high (HiS) saccharin intake. Psychopharmacology 227(1), 117–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter P, Pappas RS, Bravo R, Lisko JG, Damian M, Gonzales-Jimenez N, Gray N, Keong LM, Kimbrell JB, Kuklenyik P, 2016. Characterization of SPECTRUM variable nicotine research cigarettes. Tobacco regulatory science 2(2), 94–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi M, Sianati S, Anaraki DK, Ghasemi M, Paydar MJ, Sharif B, Mehr SE, Dehpour AR, 2009. Study of morphine-induced dependence in gonadectomized male and female mice. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 91(4), 604–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA, 2019. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19–5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. [Google Scholar]

- Slattery DA, Cryan JF, 2012. Using the rat forced swim test to assess antidepressant-like activity in rodents. Nature protocols 7(6), 1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P, 2001. Smoking: Risk, perception, and policy. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Small E, Shah HP, Davenport JJ, Geier JE, Yavarovich KR, Yamada H, Sabarinath SN, Derendorf H, Pauly JR, Gold MS, Bruijnzeel AW, 2010. Tobacco smoke exposure induces nicotine dependence in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 208(1), 143–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldin OP, Chung SH, Mattison DR, 2011. Sex differences in drug disposition. BioMed Research International 2011, Article ID 187103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Xue S, Behnood-Rod A, Chellian R, Wilson R, Knight P, Panunzio S, Lyons H, Febo M, Bruijnzeel AW, 2019. Sex differences in the reward deficit and somatic signs associated with precipitated nicotine withdrawal in rats. Neuropharmacology 160, 107756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres OV, Gentil LG, Natividad LA, Carcoba LM, O’Dell LE, 2013. Behavioral, biochemical, and molecular indices of stress are enhanced in female versus male rats experiencing nicotine withdrawal. Frontiers in psychiatry 4, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Frye CA, 2007. The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nat.Protoc 2(2), 322–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker N, Fraser T, Howe C, Laugesen M, Truman P, Parag V, Glover M, Bullen C, 2015. Abrupt nicotine reduction as an endgame policy: a randomised trial. Tobacco control 24(e4), e251–e257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall MA, Johnson J, Jacob P, Benowitz NL, 1988. Cotinine in the serum, saliva, and urine of nonsmokers, passive smokers, and active smokers. Am.J.Public Health 78(6), 699–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RJ, Hajek P, Belcher M, 1989. Severity of withdrawal symptoms as a predictor of outcome of an attempt to quit smoking. Psychol.Med 19(4), 981–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P, Towell A, Sampson D, Sophokleous S, Muscat R, 1987. Reduction of sucrose preference by chronic unpredictable mild stress, and its restoration by a tricyclic antidepressant. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 93(3), 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Bishnoi M, Keijzers KF, van Tuijl IA, Small E, Shah HP, Bauzo RM, Kobeissy FH, Sabarinath SN, Derendorf H, Bruijnzeel AW, 2010. Preadolescent tobacco smoke exposure leads to acute nicotine dependence but does not affect the rewarding effects of nicotine or nicotine withdrawal in adulthood in rats. Pharmacol.Biochem.Behav 95, 401–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.