Abstract

Many viruses employ ATP-powered motors for genome packaging. We combined genetic, biochemical, and single-molecule techniques to confirm the predicted Walker-B ATP-binding motif in the phage λ motor and to investigate the roles of the conserved residues. Most changes of the conserved hydrophobic residues resulted in >107-fold decrease in phage yield, but we identified nine mutants with partial activity. Several were cold-sensitive, suggesting that mobility of the residues is important. Single molecule measurements showed that the partially-active A175L exhibits a small reduction in motor velocity and increase in slipping, consistent with a slowed ATP binding transition, whereas G176S exhibits decreased slipping, consistent with an accelerated transition. All changes to the conserved D178, predicted to coordinate Mg2+•ATP, were lethal except conservative change D178E. Biochemical interrogation of the inactive D178N protein found no folding or assembly defects and near-normal endonuclease activity, but a ~200-fold reduction in steady-state ATPase activity, a lag in the single-turnover ATPase time course, and no DNA packaging, consistent with a critical role in ATP-coupled DNA translocation. Molecular dynamics simulations of related enzymes suggest that the aspartate plays an important role in enhancing the catalytic activity of the motor by bridging the Walker motifs and precisely contributing its charged group to help polarize the bound nucleotide. Supporting this prediction, single molecule measurements revealed that change D178E reduces motor velocity without increasing slipping, consistent with a slowed hydrolysis step. Our studies thus illuminate the mechanistic roles of Walker-B residues in ATP binding, hydrolysis, and DNA translocation by this powerful motor.

Keywords: terminase, molecular motor, virus assembly, nucleoprotein packaging complexes

INTRODUCTION

The assembly pathways of many large double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses, including the herpesviruses and many tailed phages, include a DNA packaging step in which newly replicated viral genomes are packaged into preformed protein shells [1-5]. The packaging substrate is typically a multi-genome concatemer and the reaction is performed by a viral-encoded terminase enzyme. Terminases recognize viral DNA and cleave the polymeric packaging substrate at the beginning of one genome sequence. Following the initial DNA cleavage, terminase remains bound to the newly created genome end. The terminase-DNA complex next docks on the portal vertex of the icosahedral procapsid shell; the portal vertex is a dodecamer of radially disposed subunits with a central channel for DNA transit. Upon docking, terminase’s packaging ATPase is activated to power translocation of the DNA into the procapsid. DNA packaging is terminated when terminase cleaves the DNA at the downstream end of the genome sequence and releases the DNA-filled capsid (Figure 1A) [6]. The ATP-fueled terminase motors are extremely powerful, generating very high forces (>50 pN) and translocating DNA rapidly (~600 bp/sec in phage λ) and with high processivity, ultimately packaging DNA to near crystalline density [2, 7-12]. While much is known about the structure function of these motors [13-27], the chemo-mechanics of translocation is not fully understood.

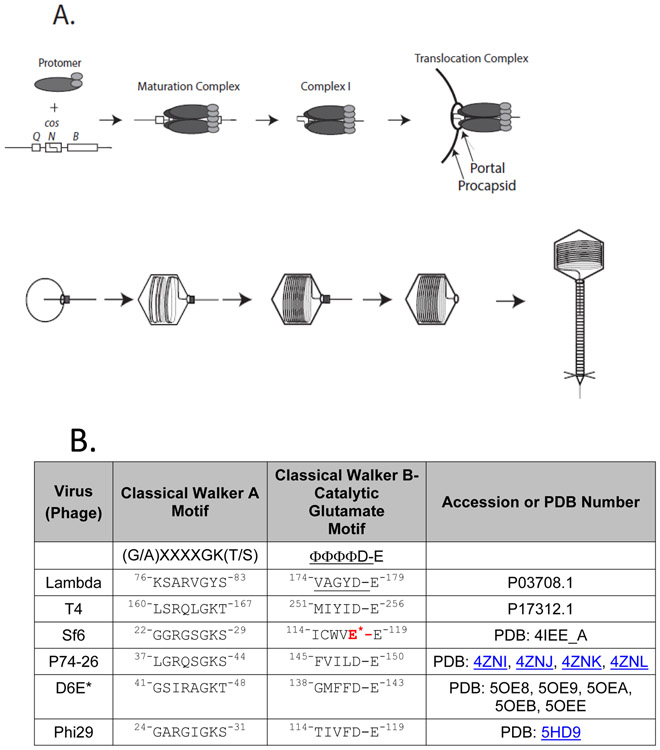

Figure 1. Model of lambda genome packaging.

A-Upper: Packaging initiation. The terminase protomer is a tight association of two TerSλ subunits and one TerLλ subunits. In the N-terminal domain (NTD) of TerSλ is a winged helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif and the TerSλ dimerization interface. The TerSλ C-terminal domain (CTD) includes a functional domain for interacting with TerLλ’s N-terminus. TerLλ consists of two globular domains connected by a linker. The TerLλ NTD contains the DNA packaging ATPase and the CTD contains the maturation endonuclease. Four protomers form into a ring-like structure at the cos site of a lambda genome concatemer, assembling the maturation complex. Maturation complex assembly involves interactions of TerSλ with cosB, and the TerLλ endonuclease with cosN, and requires ATP and/or IHF. Following duplex nicking by TerLλ and ejection of the upstream, cosQ-containing DNA end yields the post-cleavage complex (Complex I). Complex I docks at the portal of an empty procapsid, producing the packaging motor complex. Complex I docking involves an interaction between the TerLλ C-terminal tether and the portal protein. Docking activates the packaging ATPase, which powers translocation of DNA into the procapsid shell. We note that the stoichiometry of the protomer subunits bound to the procapsid, along with the subunit arrangement in the maturation complex, remain speculative at this time. A-Lower: Translocation and virion assembly. Progression of translocation is shown proceeding left to right. When ~30% of the DNA has been translocated, procapsid expansion is triggered, and translocation proceeds until the next cos along the concatemer is encountered. Interactions between the translocating terminase and cosQ and cosN lead to nicking of the downstream cos, and terminase undocking. Addition of gpW and gpFII to the portal is followed by tail attachment, generating a mature virion. B. ATPase motif sequences. Walker B motif and catalytic glutamate ASCE sequences are given for TerLs discussed in this paper. Beginning and ending residue numbers are given in superscripts. *Note that TerLSf6 contains a deviant glutamate (red) rather than the canonical aspartate found in most ASCE Walker B sequences

Terminases are generally hetero-oligomers of a small subunit (TerS) that specifically recognizes viral DNA and a large catalytic subunit (TerL) 1. The TerL subunits possess C-terminal DNA processing endonuclease and N-terminal ATP hydrolysis-powered translocase activities required to mature and package the viral genome [1, 5, 20, 28-30]. Atomic structures of TerL subunits from phages T4, Sf6, P74-26, and D6E, and the packaging ATPase of phi29 [13, 19, 21, 31, 32] show that the N-terminal ATPase fold belongs to the oligomeric ring ATPases group of Additional Strand, Catalytic Glutamate (ASCE) ATPases [33-35]. This oligomeric ring ATPases include many cellular ATPases of diverse function that act in protein unfolding and degradation, protein transport and translocation, ATP synthesis, and DNA recombination reactions [35-38]. The ASCE fold is strongly conserved in both viral and cellular molecular motors and contains Walker A (WA) and Walker B (WB) motifs involved in ATP binding and hydrolysis. Extensive studies in a variety of cellular systems including the elongation factor EF-Tu, adenylate kinase and myosin [39-41] and in many phage genome packaging motors including T4, Sf6, P74-26, and phi29 [13, 19, 21, 31, 42] implicate specific roles for residues in these motifs, as follows. The classical WA signature sequence is [(G/A)XXXXGK(T/S)], where “X” represents a variable amino acid [43]. The conserved lysine ε-amino group coordinates the β- and γ- phosphates and the serine/threonine hydroxyl group coordinates the Mg2+ of the bound Mg2+•ATP, positioning the β-and γ-phosphates for hydrolysis [19, 21, 31, 44, 45]. In addition, many viral packaging motors have been identified to have a conserved arginine at position 3 or 4 in the WA motif which has been implicated in ATP hydrolysis and chemomechanical coupling [13, 21, 25, 46]. Downstream from WA is the WB motif, whose classical signature sequence is ϕϕϕϕD, where ϕϕϕϕ indicates a quartet of hydrophobic residues; the conserved WB aspartic acid residue coordinates the Mg2+ of the bound Mg2+•ATP, along with the WA serine/threonine [19, 21, 31, 44]. This conserved aspartate is distinct from a conserved “catalytic glutamate” that directly follows in the WB of ASCE ATPases (Figure 1B) and evidence suggests activates a water molecule for nucleophilic attack of the γ-phosphate [19, 21, 35, 44, 47-49] .

Before any TerL structures were known, pioneering work by Rao and co-workers predicted the locations of WA and WB ATPase motifs in a number of TerL proteins based on sequence alignments (Figure 1B) and confirmed the predictions for TerLT4 via genetic and biochemical studies [29, 45-47, 50]. In genetic studies of the WA sequence, the Arg, Gln, Gly, and Lys residues could not be changed without loss of function, and for the Thr, only the conservative Ser substitution was functional [13, 29, 42]. Multiple residues in the TerLT4 WB “hydrophobic quartet” could be changed without loss of function although the results supported the importance of hydrophobicity [45]. Any changes to the Asp were lethal and found to impair photo-affinity cross-linking by azido-ATP, indicating a nucleotide binding defect. In contrast, changes of the catalytic Glu did not abrogate azido-ATP binding, but did abolish ATP hydrolysis and DNA packaging [45, 47]. Subsequently, crystal structures of the phage T4, Sf6, P74-26, phi29, and D6E motor proteins confirmed the predicted WA and WB motifs [19, 21, 31, 32, 44].

The phage λ DNA packaging system is highly developed for genetic, biochemical and biophysical studies. Genetic studies implicate the N-terminal domain of TerL in DNA translocation [28], and azido-ATP cross-linking studies identified residues indicating the locations of the adenine binding and WA motifs [51]. Biochemical studies have elucidated the assembly of the terminase multimer, as follows. Terminase subunits form a stable TerS2•TerL1 protomer, which assembles at cos, the packaging initiation site in the λ concatemer, to afford a catalytically competent nuclease complex that “matures” the genome end in preparation for packaging [52]. The post-cleavage nucleoprotein complex then binds to the portal to afford the packaging motor complex that translocates DNA into the shell; biochemical studies indicate that the protomers are functionally coupled during DNA translocation [53].

Given the conservation of structural and functional features of ASCE domains, and specifically in the terminase enzymes, we embarked on an integrated genetic, biochemical and biophysical dissection of the ATPase domain TerLλ as a model system. We previously applied this approach to characterize the functional roles of TerLλ residues in the adenine binding Q motif (N-linker), the coupling C motif (motif III) and a loop-helix-loop motif implicated in motor velocity [22, 23]. We further confirmed and characterized the proposed WA motif in TerLλ (76-KSARVGYSK−84) [25], in which the critical lysine is at the beginning of the WA motif (K76) rather than its typical position at the C-terminal end. The results from these studies led us to propose a model wherein ATP binding to TerLλ drives a conformational change that results in tight ATP binding and tight DNA gripping (Figure S1) analogous to the “tight binding transition” proposed previously for phage phi29 [17, 25] . More recently, we confirmed that TerLλ’s catalytic glutamate is residue Glu179. Changes eliminating the carboxylate functional group abolished ATP hydrolysis and DNA translocation [49]. Remarkably, we found that the conservative residue change E179D caused nearly identical perturbations of the translocation dynamics as change R79K to the conserved arginine in the WA motif. These findings suggested that both changes affect the chemo-mechanical ATP hydrolysis cycle in a similar way. Supporting this proposal, structure-based molecular dynamics simulations [49] predicted that the conserved catalytic glutamate, E179, and the conserved Walker A arginine, R79, interact and work in concert to bind ATP and align the hydrolysis transition state in an “open-to-closed” active site conformation that may be a common mechanistic feature in many terminases. In addition, the simulations and mutant findings provided evidence for an “arginine toggle” mechanism in which, after hydrolysis and product release, the WA arginine rotates away from the catalytic Glu to interact with a different Glu residue in the “lid” subdomain that is proposed to mediate chemo-mechanical coupling to drive DNA translocation. In summary, our integrated studies of TerLλ residues have confirmed many motif predictions and revealed that single amino acid changes affect not only ATP binding and hydrolysis, but also chemo-mechanical coupling, multi-subunit ring assembly and DNA translocation dynamics [22, 23, 25, 49].

In the present study, we extend our characterization of the ASCE domain and validate the assignment of the predicted 174-VAGYD−178 WB motif in TerLλ. More importantly, we define the role of these residues in motor function. Our findings indicate that the four hydrophobic residues, with a few exceptions, cannot be changed without loss of function, and suggest that they are important for both folding and domain mobility to facilitate interaction of the catalytic Glu with ATP. The data further confirm that D178 is critical for rapid DNA translocation, consistent with the predicted role in Mg2+•ATP binding, and suggest that WB residues play an important role in properly positioning charge groups to catalyze hydrolysis. Given the conservation of structure and function of the ASCE ATPase domains, both viral and cellular, these insights into viral terminase function provide information that broadens our understanding of ATP-powered biomotors.

Results

Genetic Analysis: Functional Effects of Residue Changes.

Genetic Screen of the WB Hydrophobic Quartet.

Sequence analysis revealed that TerLλ residues 174-VAGYD−178, followed by the putative catalytic glutamate E179, are a good fit to the WB signature sequence (Figure 1B) and we first examined their roles using a genetic screen. We surveyed the effects on phage yield of many single and double residue changes spanning the putative WB hydrophobic quartet (gene A codons 174 to 177). Mutagenesis was done using oligonucleotide primers with randomized bases in the target codons and, following sequencing, selected mutants were chosen for further study. A total of 32 residue changes were examined using a sensitive complementation assay [25] in which a plasmid was used to provide TerLλ (WT or mutant) to a defective phage at a level of expression approximating that during a normal virus infection. Specifically, the complementation plasmid supplies TerLλ to an inducible mutant prophage carrying two A amber mutations (λ Aam), used to block normal TerL expression. When the plasmid provides functional TerLλ subunits to the induced λ Aam prophage, packaging of the λ Aam phage genome occurs and the yield of λ Aam phage is determined by titering the lysate on a host containing the appropriate amber suppressor. This host allows the λ Aam phage to produce WT terminase and form plaques, which are counted to determine the virus yield. Complementation with WT TerLλ typically produces a virus yield of 3-10 phages/induced lysogen; mutants expressing partially active TerLλ show intermediate yields of λ Aam phages, reflecting the level of functional TerLλ. In this manner, mutant terminases that sponsor small amounts of viral assembly, down to ~10−7 the level for the WT TerLλ plasmid, can be quantified. This approach provides much higher sensitivity to terminase activity than achieved by directly introducing TerLλ mutations into the viral genome and studying their effect on plaque formation, because for a λ strain to produce a plaque its yield must typically be greater than ~10% that of WT (green, Figure 2). From the complementation results, we thus refer to a mutation as “lethal” if the yield is lower than this amount even though much lower levels of viral assembly assay can be detected by the complementation assay.

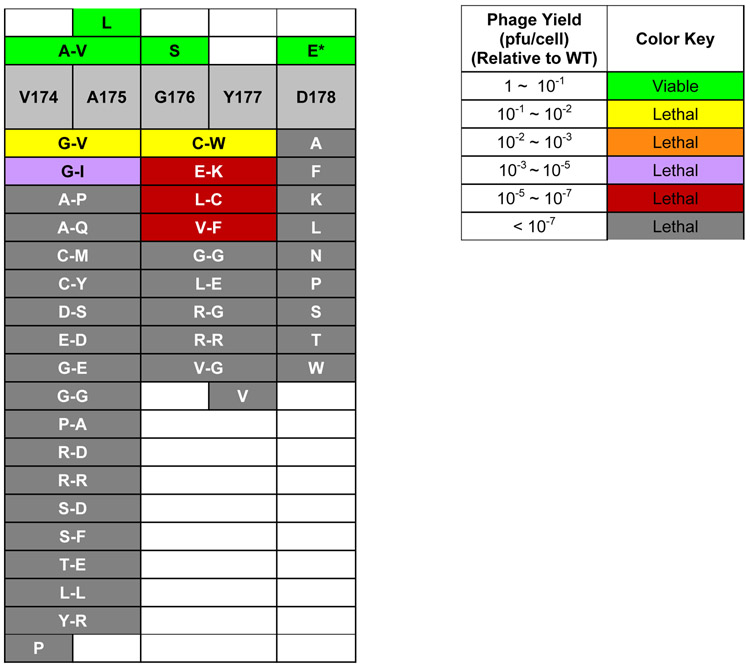

Figure 2: Effects of residue changes in the Walker B motif on virus yield.

Left table lists the mutants tested and a color-key is used to indicate the range of detected degrees of impairment expressed in terms of phage yield in plaque forming units per cell relative to WT (where the WT activity is defined to be 1). Right table lists the color-key that indicates the relative phage yields. Dark gray color is used to designate cases where no phage yield was detected (i.e., below the level of sensitivity of the assay). Pairs of codons were mutagenized for codons 174-175, and for 176-177, though single codon changes were made for the V174P, A175L, G176S, and Y177V mutants. Wildtype terminase sponsored yields of 3 – 10 λ Aam/induced cell. Two of the mutants, V174V+A175L and V174P+A175A were effectively single mutants because each contained a same-sense codon change in addition to a mutation causing a residue change. The same-sense changes were to codons with usage frequencies similar to that of the wildtype codon. For example, the codon changes producing TerLλ-V174V+A175L were GUG+GCG→GUA+CUG. The codon usages in E. coli for the wildtype and same-sense valine codons are 2.4% and 1.2%, respectively. The GUA codon is occurs twice in the wildtype A gene, indicating that the change to this codon is unlikely to affect gene expression. Accordingly, these two mutants are listed as single mutants V174P and A175L.

As an initial test, we mutagenized the adjacent codon pairs 174-VA−175. In total, 19 double mutants were characterized. In stark contrast to findings in the phage T4 system which tolerated many residue changes, we found that only the TerL with the highly conservative VA→AV change supported a normal virus yield while 18 of the 19 double mutants were lethal (<10% yield) (Figure 2). Of the 18 lethal mutations only two, VA→GV and VA→GI, supported detectable levels of terminase function, with virus yield levels of 0.13 and 3.3 × 10−5 that of WT, respectively (Figure 2). The other 16 were profoundly defective (<10−7 that of WT), including the conservative VA→LL change. We similarly mutagenized the adjacent 176-GY−177 codon pairs and all 9 of the double mutants were lethal changes, exhibiting various degrees of functional impairment; change GY→CW resulted in a lethal, 20-fold reduction while changes to EK, LC, or VF caused >105-fold reductions (Figure 2). The remaining tested residue changes were profoundly lethal, reducing the virus yield to a level below the sensitivity of the assay (i.e., by >107-fold). In addition to the double mutants above, a set of single mutants were tested to study the functional roles of individual hydrophobic quartet residues: Of these, A175L and G176S were viable, while V174P and Y177V were profoundly lethal (Figure 2).

Walker B Mutant Phages.

To confirm the results obtained from the complementation experiments above, we constructed lysogens carrying prophages with mutations expressing TerLλs with the viable VA→AV, A175L, G176S changes (Figure 2), as described in Materials and Methods. Induction of the viable mutant prophages allowed us to characterize each mutant phage’s ability to form plaques, which requires that a mutant phage produce a yield of at least about 15 virions/induced lysogen, i.e., ~10% of the wild type. The results confirmed the above complementation study: The viable mutants VA→AV, A175L, and G176S, produced robust, near-wild type yields at 37°C (Table S1).

We also tested the viable mutant phages for conditional lethality. The A175L phage forms small plaques at 42°C and 37°C, but none at 30°C, hence it is a cold-sensitive (cs), conditionally lethal mutant. The VA→AV phage formed small plaques at 42°C and 37°C, and tiny plaques at 30°C, indicating non-lethal cold sensitivity. The G176S phage, like the WT phage, forms large plaques at 42°C and 37°C and medium plaques at 30°C, indicating that this mutation has essentially WT phenotype.

Finally, we measured the virus yields for the non-plaque forming VA→GV and GY→CW mutant prophages. The parent phage into which WB mutations were placed carries a kanamycin resistance cassette (see Materials and Methods), which enables us to determine the yields of phages per cell for the lethal mutants, i.e., phages carrying the VA→GV and GY→CW changes, by measuring the number of kanamycin resistance transducing particles in a lysate. In agreement with the complementation results, we found that both mutant phage yields were somewhat below the threshold necessary for plaque, with the VA→GV and GY→CW phages having yields 2% and 4% that of the wild type phage, respectively (Table S1).

In sum, the complementation and phage yield assays indicate that all four of the hydrophobic residues spanning 174-VAGY−177 in TerLλ are functionally important and, except for a few conservative changes, they cannot be changed without loss of function. The results support the proposal that these residues comprise the hydrophobic quartet of TerLλ’s WB segment and, to a greater degree than for TerLT4, show that this specific sequence is critical for efficient viral assembly. These TerLλ results indicate that additional properties of these residues besides just hydrophobicity are important. We note that these four residues are at the end of β strand 3 in the ATPase domain and the specific amino acid sequence is likely important, presumably for residue packing within the domain and/or proper positioning of the downstream 178-DE−179 residues putatively involved in ATP binding and catalysis, respectively. That two of three viable mutants show cold sensitivity further suggests that mobility within the hydrophobic quartet, and thus β3, is important for terminase function; this is discussed further below.

The Conserved WB Aspartate.

We next examined the conserved TerLλ-D178 residue, which has been implicated in coordinating the Mg2+ cofactor of the Mg2+•ATP moiety in the ASCE enzymes. If D178 serves this role, then the expectation is that its carboxylate is critical for ATP binding and/or hydrolysis. The genetic results are in accord with these expectations; no changes to non-acidic residues (of 9 tested) produced terminase with detectable function (Figure 2). In addition to the complementation studies, a phage carrying the D178E codon, TerLλ -D178E, was constructed and found to form small plaques at 42°C, tiny plaques at 37°C and was unable to form plaques at 30°C, indicating that the D178E change is a cold-sensitive conditional lethal mutant (Table S1). Thus, even this conservative TerLλ-D178E change has significant functional effects.

Effects of WB mutations on gene expression and terminase assembly.

Based on studies in the T4 system, the lethal phenotypes of nearly all the TerLλ mutations examined was unexpected. A trivial explanation would be that the changes affect efficient expression of the protein as opposed to the desired effect of perturbing motor function (e.g., ATP binding, hydrolysis, chemo-mechanical coupling, etc.). To address this question, we examined WB mutant expression. Selected mutations, including 174-VA−175→GI, A175L, D178A, D178E, and D178N, were transferred to the terminase expression vector, pQH101alt. Following terminase expression, whole cell extracts were electrophoresed on SDS-PAGE gels and the Coomassie blue-stained gels showed that TerLλ is efficiently expressed by the WT and all the missense mutants examined (data not shown). Thus, these WB mutant enzymes do not have significant gene expression defects [25].

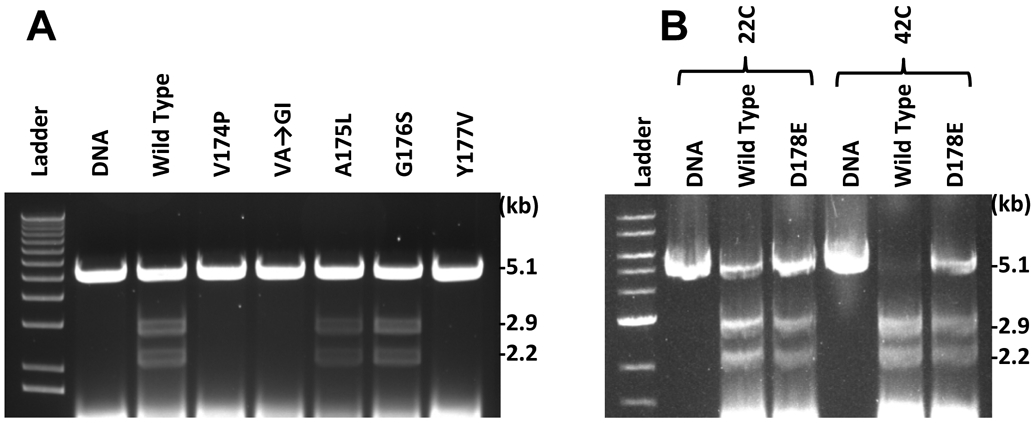

To test functional integrity, we next examined selected mutants, in vitro, to determine if they were folded and assembled properly, using the following approach. Because the introduced mutations reside in the N-terminal ATPase domain of TerLλ, we expected them to selectively affect the ATPase (and thus DNA packaging) activity. The cos-cleavage endonuclease center resides in the C-terminal domain and should be unaffected if the mutant protein is folded and can assemble a functional maturation complex [28, 54] (Figure 1A). Thus, if holoterminase is properly folded and assembled, the mutant enzymes should retain normal cos cleavage activity in crude cell extracts. In vitro cos cleavage assays, done at 22°C, showed that of eight mutant enzymes examined, V174P, 174-VA−175→GI, Y177V (Figure 3), and D178A (not shown), lacked cos cleavage activity. Thus, these four mutants likely have defects in folding and/or assembly, which explains their lethal defect. However, the other four mutant enzymes, A175L, G176S, D178E (Figure 3), and D178N (vide infra), retained cos cleavage activity, which requires a folded and functional enzyme. These findings suggest that the WB residues play specific and significant roles in the folding and stability of an active terminase enzyme.

Figure 3. In vitro cos cleavage activity of terminases.

Cleavage assay results for selected mutants. Cleavage of the 5.1 kb substrate DNA at cos produces 2.9 and 2.2 kb product DNAs. A. Standard reactions done at 30°C. B. Reactions done at 22°C and 42°C with the cold-sensitive gpA D178E terminase. Unlabeled lanes are 1 kb ladder (New England Biolabs). The A175L extracts contained an EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (“cOmplete Mini”, Roche, Inc.) at the recommended concentration.

Finally, we were also curious about the cold-sensitivity of the D178E mutant phage (Table S1) and asked if this is the result of a stability defect of the mutant enzyme. To examine this possibility, we compared cos-cleavage activity of the D178E mutant enzyme at 22°C and 42°C (Figure 3B). No significant differences from wild type were found, indicating that the cold sensitivity of the D178E mutant does not involve the endonuclease activity at these temperatures.

Biochemical and Ensemble Biophysical Analysis of the TerLλ-D178N Enzyme

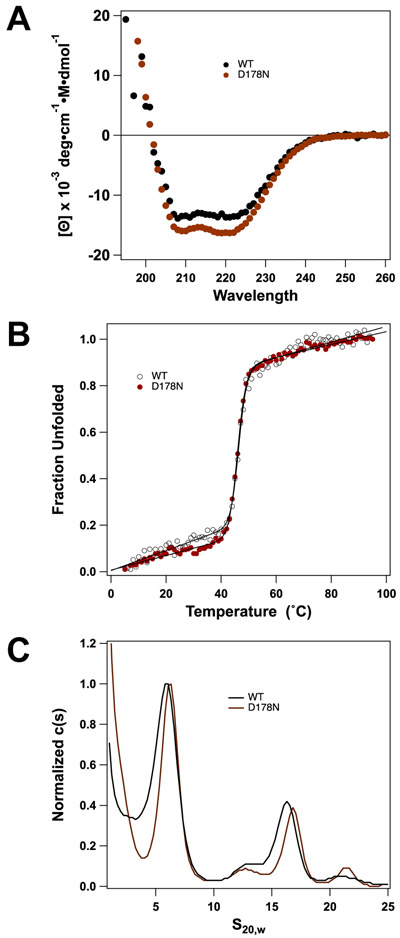

Based on the genetic studies described above, we chose the TerLλ-D178N mutant terminase for biochemical interrogation to probe for the mechanistic defect. This residue is proposed to coordinate Mg2+ to bind Mg2+•ATP at the active site. Consistently, the mutation is lethal to phage growth (Figure 2) but retains WT cos-cleavage activity in the crude extract assay (not shown). This suggests that the enzyme is selectively defective in ATPase activity, and thus genome packaging, as predicted. To test this hypothesis, TerLλ-D178N terminase was expressed and purified as previously described [25, 53, 55]. The yield of mutant enzyme is similar to that of WT (not shown), suggesting that no significant structural defects resulted from the residue change. Consistently, the circular dichroism spectrum of the mutant protein is essentially identical to WT, indicating that the mutation does not affect the secondary structure of the protein (Figure 4A). We next examined the stability of the mutant enzyme, and Figure 4B shows that thermal denaturation of the TerLλ-D178N enzyme mirrors that of the WT enzyme, an indication that tertiary structures have not been significantly affected. The terminase protomer is composed of one TerL subunit tightly associated with two TerS subunits and the protomers assemble into a functional ring-like complex [52, 55, 56]. Analytical ultracentrifugation analysis demonstrates that the mutant protein similarly associates into a stable protomer and that the protomer-ring equilibrium remains intact (Figure 4C). In sum, the data confirm that the TerLλ-D178N mutant enzyme is appropriately folded in solution and retains WT quaternary interactions required to assemble a functional motor.

Figure 4. Assessment of protomer folding and thermal stability.

(A) CD spectra show that secondary structure compositions for TerLλD178N are similar to WT (~37% α-helical, ~17% β-sheet). (B) Thermal denaturation was monitored by CD (222 nm) and the data were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods (solid lines). The data show that the TerLλ-D178N mutant has thermal stability similar to WT; Tm= 46.4 ± 0.21°C and Tm= 46.0 ± 0.1°C, respectively. (C) SV-AUC analysis indicates the TerL-D178N Walker B mutant has no major assembly defect. The WT protomer (~6S) is in slow equilibrium with a tetramer of protomers.

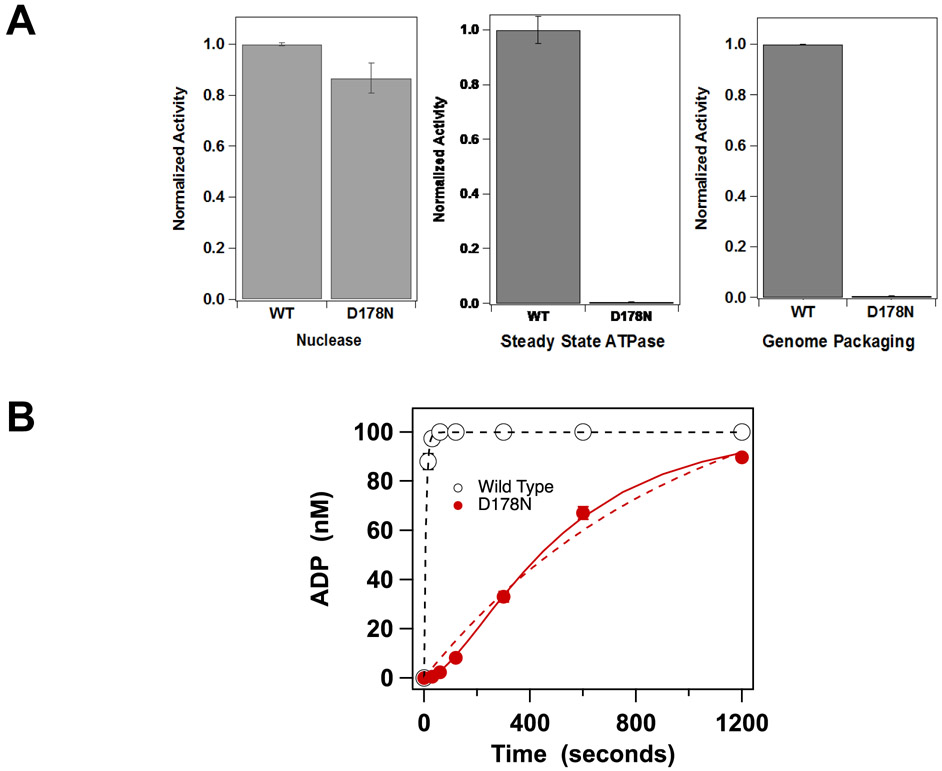

We next examined the catalytic activity of the enzyme. Consistent with the initial studies described above which used cell extracts, the cos-cleavage activity of purified TerLλ-D178N is intact (Figure 5A); this indicates that the C-terminal endonuclease domain has not been affected by the mutation. In contrast, the steady state ATPase activity of the mutant enzyme is severely compromised (0.5% activity compared to WT). Consistent with this result, DNA packaging activity, which is fueled by ATP hydrolysis, is similarly compromised by the mutation (0.7% activity compared to WT, Figure 5A). To further probe the mechanistic basis for the ATPase defect, we examined single turnover ATP hydrolysis by TerLλ-D178N terminase to probe the kinetics of the reaction. In this assay, enzyme is included in excess of the ATP substrate and catalysis is limited to a single event that includes ATP binding and hydrolysis steps; subsequent product release step(s) are not included in the kinetic time course. The data presented in Figure 5B demonstrate that while single turnover ATP hydrolysis is observed, it is severely compromised in the mutant enzyme compared to WT. The kinetic data were first analyzed according to a simple monophasic kinetic model, which describes the WT enzyme well (Figure 5B) and affords kobs = (0.139 ± 0.016) sec−1 (Table 1). In contrast, the kinetic time course for the TerLλ-D178N enzyme is poorly described by this simple model due to a distinct lag in product formation.

Figure 5. Catalytic Activity of TerLλ-D178N terminase.

cos-cleavage nuclease, DNA packaging and steady-state ATPase activities were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar represents the average of three separate experiments with error-bars indicating the standard errors in the mean. (B) Single turnover ATP hydrolysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods; the reaction was initiated by the addition of enzyme. The reaction time courses for WT (○) is well described by a single-turnover, monophasic exponential model (solid line). In contrast, TerLλ-D178N displays a significant lag phase (●), which is poorly described by the simple model (see text; dashed red line). The mutant data are better described by the three-state model that includes a slow step prior to catalysis (Equation 1, solid red line). The kinetic constants derived from non-linear regression analysis of each data set is presented in Table 3.

Table 1. Single Turnover ATPase Kinetic Analysis.

The data presented in Figure 5B were fit to a monophasic reaction time course and a three-state kinetic model as described in Materials and Methods. The derived rate constants are presented with standard deviations as indicated.

| Enzyme | Monophasic Model | Three-State Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| kobs (s−1) | k1 (M−1s−1) | k2 (s−1) | |

| WT | (0.139 ± 0.016) | - | - |

| D178N | (1.0 ± 0.4) x 10−3 | (1.7 ± 0.2) x 104 | (2.4 ± 0.1) x 10−3 |

| R79A | - | (1.3 ± 0.9) x 104 | (5.3 ± 2.9) x 10−3 |

We previously demonstrated that the TerLλ WA R79A mutant had a similar kinetic lag and required a more complex kinetic model to explain the data [25]. Thus, we proposed a model that includes a slow, reversible step prior to the chemical step (e.g., ATP hydrolysis);

| (1) |

where P represents the terminase protomer in solution, P4•DNA•ATP represents the catalytically competent ATP-bound multimer assembled on DNA, k1 and k-1 are the rate constants for the slow step prior to catalysis and k2 is the rate constant for ATP hydrolysis (the chemical step). Importantly, this model simplifies to the monophasic one when k1 is fast. As shown in Figure 5B, fitting of the ATP hydrolysis time course for TerLλ-D178N to the three-state model significantly improves the quality of the fit. The observed rate constant for ATP hydrolysis by TerLλ-D178N is 1.7% that of the WT enzyme (k2 vs. kobs, Table 1), consistent with the steady-state ATPase data (Figure 5A). Importantly, the slow step prior to hydrolysis (k1) is significantly slower than would be anticipated from a diffusion-controlled ATP binding encounter (108-109 M−1s−1), consistent with a slow conformational change prior to catalysis [25].

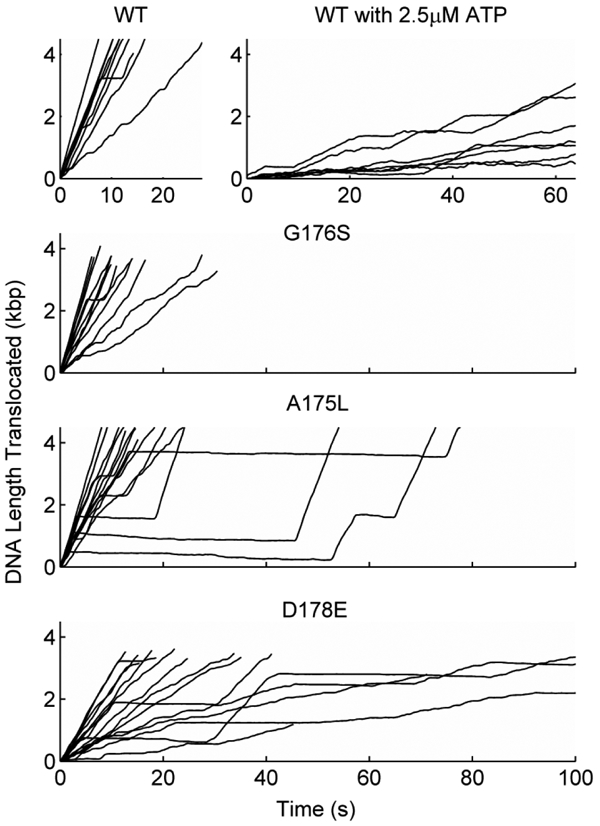

Single Molecule Measurements of DNA Translocation Dynamics

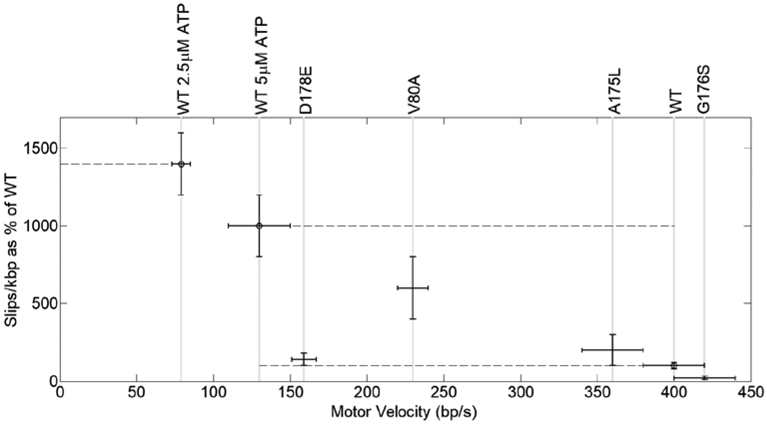

Selected mutants were chosen for further analysis by a single-molecule assay we developed that directly measures DNA translocation dynamics [9, 22, 23, 25, 49, 57]. Partly pre-packaged procapsid-motor-DNA complexes are attached to a microsphere trapped with optical tweezers and the external end of the DNA molecule being packaged is attached to a second trapped microsphere. As the DNA is packaged the two microspheres are pulled together and increasing DNA tension is measured. The separation between the two traps is controlled by a feedback system which maintains a small tension of 5 pN to keep the DNA stretched while it is translocated, allowing the length of DNA packaged vs. time to be measured (Figure 6) [9, 57]. The measurements were made with saturating ATP (0.5 mM), low capsid filling (0-20% of the genome length packaged), and at room temperature (~23 °C). From these measurements we derive the overall packaging rate, the “motor velocity” (translocation rate not including pauses and slips), the frequency of slipping and pausing, and duration of pauses. As discussed below and in prior work [25, 49], relative changes in motor velocity and slipping shed light on residues involved in the ATP binding step versus those involved in the chemical hydrolysis step, while changes in pausing shed light on residues involved in proper alignment of ATP in the binding pocket.

Figure 6. Examples of single DNA molecule translocation measurements for wildtype terminase (WT) and mutants G176S, A175L, and D178E as indicated.

All plots are of DNA length translocated (kpb) vs. time (seconds) and the bottom three plots share the same horizontal axis tick labels as indicated on the bottom plot. All measurements are with saturating ATP (500 μM) except for the WT measurements labeled 2.5 μM ATP.

The Hydrophobic Quartet.

To investigate roles of the four predicted hydrophobic WB residues we examined four examples of single residue changes, one at each position: V174P, A175L, G176S, and Y177V. We also studied one double residue change mutant (174VA175→GI), of interest because it exhibited a detectible, though highly reduced phage yield in the genetic studies (Figure 2).

Genetic studies found no detectible phage yield in the complementation assay for mutants V174P and Y177V and consistently, no DNA translocation activity was detected for either of these mutants despite hundreds of trials (Figure 7). As described above, this lack of activity is likely due to perturbation of the predicted hydrophobic β-sheet by these changes and defects in enzyme folding or assembly (Figure 3). The 174-VA−175→GI double mutant exhibited a small phage yield despite folding defects (vide supra) and Figure 7 shows there was no detectible DNA translocation activity despite hundreds of trials. Together, these findings suggest that while the efficiency of packaging initiation by 174-VA−175→GI is very low in vitro (<1%), at least some motors can package the full-length genome in vivo and afford infectious phages.

Figure 7. Effects of limiting ATP and Walker B residue changes on motor velocity and pausing.

Pausing frequency vs. motor velocity for wildtype terminase (WT) and mutants (indicated by labels on top of plot). Results for mutant V80A from a previous study are shown for comparison. Measurements were done with saturating ATP (500 μM) and, for WT, also with sub-saturating ATP (5 μM and 2.5 μM, where indicated). Dashed lines indicate pausing frequencies for WT with the different ATP concentrations. Note that the V80A mutant (measured with 500 μM) follows the trend that exhibited by the WT of increasing pause frequency with decreasing motor velocity, but mutant D178E does not.

In contrast to the above findings, change A175L, which increases hydrophobicity and side chain bulk, resulted in only minor impairments in translocation activity (Figure 7); this is consistent with the finding of a phage yield similar to WT in the genetic studies (Figure 2). More specifically, the average motor velocity nominally decreased by ~10%, slipping frequency increased ~2-fold, pausing frequency increased ~30%, and the duration of pauses increased ~2.4-fold (Figures 6 and 7). An increase in slipping with decreasing motor velocity is consistent with the trend measured for WT with decreasing [ATP] (Figures 7 and 8), which suggests that the residue change slightly slows the ATP tight binding transition (see Supplemental Figure S1) [25]. The increased pause duration further suggests that the residue change results in intermittent binding of ATP in a misaligned orientation that delays ATP hydrolysis and coupled DNA translocation.

Figure 8. Metrics of DNA translocation activity for wildtype (WT) and mutant terminases determined by analysis of the optical tweezers measurements.

The results are reported as mean values, except for the last column that reports viral assembly activity (phage yield per cell) as a fraction of WT (the color codes in this column are the same as used in Figure 2). All measurements were done with saturating ATP (500 μM), except for those labeled WT 5 μM ATP and WT 2.5 μM ATP, which report WT measurements with lowered [ATP]. Uncertainties are expressed as standard error in the mean.

The near wild-type translocation activity of the TerLλ-A175L enzyme at room temperature (23°C) appears to contrast with the cold-sensitive phenotype of the phage carrying the A175L change (Table S1). However, this likely reflects differences in what is measured in the two techniques. The single molecule study measures the initial stages of packaging (<20% of the genome length packaged) while virus yield requires packaging of the complete genome. Together these findings suggest that viral assembly is impaired because of failure to efficiently package the entire genome due to a failure of the motor to overcome the large internal forces resisting DNA confinement that build up during the latter stages of packaging the full-length genome. To investigate this further, we conducted translocation measurements with 5x higher applied force (25 pN), which mimics the load forces on the motor caused by forces resisting DNA confinement encountered in the latter stages of packaging [14, 26]. Under these conditions, we found that the average motor velocity for the WT enzyme is 41% that measured at low force, while for the mutant motor it is 32% that observed at low force. Thus, the mutant motor is more sensitive to load force and this could explain its failure to sponsor efficient viral assembly because this difference could be further magnified as packaging progresses towards the end of the genome.

Finally, we examined the TerLλ-G176S enzyme. This residue change, which did not significantly alter phage yield, also did not impair translocation activity. The average motor velocity and packaging rate are consistent with the WT values (Figure 7). A particularly striking finding is that the mutant motor exhibited 5-fold less frequent slipping (i.e., 5-fold higher processivity) than the WT motor, which suggests that the residue change results in an accelerated ATP tight binding transition (see Supplemental Figure S1) [25]. This is discussed further below.

The Conserved WB Aspartate.

We next analyzed the effects of changes in residue TerLλ-D178, predicted to coordinate the Mg2+ of the bound Mg2+•ATP. Changing the negatively-charged Asp to Ala or to Asn (an uncharged side chain of similar size) resulted in no measured translocation despite several hundred trials (Figure 7). These results are consistent with both the genetic study, which detected no virus yield with either of these mutant phages (Figure 2) and the biochemical studies, which demonstrated that ATP hydrolysis and DNA packaging by TerLλ-D178N protein is severely compromised (Figure 5).

Only the TerLλ-D178E mutant, having a conservative residue change that preserves negative charge, exhibited measurable translocation activity in the single-molecule assay. Even though this residue change lengthens the amino acid side chain by only one carbon bond length, the impairment in translocation dynamics is notably more severe that that observed in response to the A175L change discussed above. Specifically, the D178E change resulted in a ~2.5-fold reduction in motor velocity (Figures 6 and 7). However, the slipping frequency did not increase (Figure 8), suggesting that it is the ATP hydrolysis chemical step that is slowed, not the ATP tight binding transition [25, 49]. In addition, a ~3-fold increase in pausing frequency and ~2-fold increase in pause duration was observed, suggesting that the residue change also results in intermittent binding of ATP in a misaligned orientation in which hydrolysis does not occur. This finding of significantly impaired translocation dynamics at room temperature is consistent with the finding that the D178E change is lethal at 30°C.

In summary, the combined genetic, ensemble biochemical, and single molecule data support the conclusion that residue D178 plays a critical role in coupled ATPase and DNA translocation functions.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

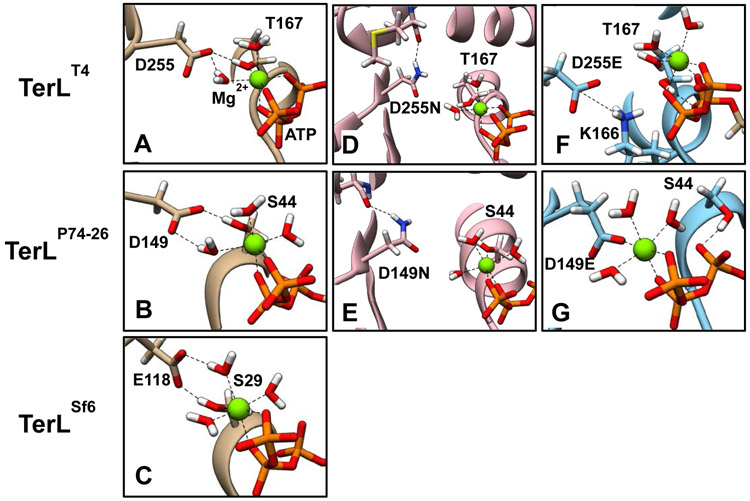

To gain further mechanistic insight into the observed defects introduced by TerLλ-D178 WB mutations discussed above, we employed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Since there is no solved structure of TerLλ, we used the available TerL crystal structures of phages T4 (TerLT4), P74-26 (TerLP74-26), and Sf6 (TerLSf6) as model systems; these three proteins are closely related to TerLλ within the terminase subfamily of ASCE ATPases. Importantly, TerLT4 and TerLP74−26 share the conserved WB C-terminal aspartate studied experimentally in TerLλ, whereas TerLSf6 possesses a deviant penultimate glutamate (E118) (labelled in red in Figure 1B). We reasoned that modeling TerLT4 and TerLP74−26 and contrasting with TerLSf6 could provide valuable insight into conserved WB mechanisms across the terminase enzyme family, which would complement our experimental data obtained with TerLλ. To this end, we performed all-atom, explicit solvent MD simulations of TerLT4-D255(N/E) and TerLP74−26-D149(N/E) mutant enzymes and compared them with corresponding WT simulations. Our goal was to elucidate the mutation-induced rearrangements within the ATP-binding pocket that are responsible for aberrant ATP hydrolysis and coupled DNA translocation.

Wild Type TerL Simulations and the ATP-Tight-Binding Transition.

Simulations of all three TerLs reveal that the conserved WB D (E in the case of TerLSf6) fulfills its predicted role of chelating Mg2+ through a water molecule (Figure 9A-C). In addition, the simulations highlight the importance of a conserved stabilizing hydrogen bond between the WB D/E carboxylate groups and the conserved WA C-terminal (T/S) hydroxyl group, which has also been implicated in Mg2+ coordination [19, 21]. This predicted interaction is apparent in the nucleotide-bound crystal structure of TerLP74−26 and is even maintained by the deviant TerLSf6-E118 residue, despite its 1.5 Å-longer side chain. To compensate for the longer side chain, the backbone of TerLSf6-E118 is farther away from the conserved WA (T/S) (Table 2) such that the WB E carboxyl group is placed in a nearly identical functional position relative to the WA (T/S) hydroxyl group. We note that while the WA-WB interaction is not observed in the TerLT4 crystal structure, the published structure is that of a WB D255E/E256D double mutant which directly affects this interaction; however, our simulations predict that this interaction is indeed present in the wild-type TerLT4.

Figure 9. Molecular dynamics simulations identify importance of interaction between WA and WB motifs.

MD simulations of the WT T4 (A), P74-26 (B), and Sf6 (C) terminase proteins highlight a conserved interaction between the WB Asp/Glu carboxylate group and the WA Thr/Ser hydroxyl group. This interaction helps the binding pocket close around the bound Mg2+-ATP as part of the tight binding transition. This interaction is maintained even with the deviant WB Glu found in Sf6 terminase due to a larger backbone-to-backbone distance (see Table 2). Simulations of Asp→Asn variants of the T4 (D) and P74-26 (E) terminase proteins show that these groups remain isolated to the WB motif and do not interact with the WA motif as found in WT. Simulations of the Asp→Glu variants of the T4 (F) and P74-26 (G) terminase proteins suggest unique defects arise in the binding pocket. The simulated T4 mutant D255E interacts with the critical WA K166, similar to mutant crystal structure (see Figure S4). The simulated P74-26 mutant D149E chelates Mg2+ directly as opposed to via a bound water molecule, displacing S44 (compare with panel B).

Table 2. Backbone distance (Cα-Cα) of the C-terminal WB D/E to the C-terminal WA T/S.

All values are reported in Å. Values from MD simulations are averaged across three independent 100 ns simulations, and the uncertainty is the standard error in the mean.

| Terminase | Apo Crystal | Apo MD | ATP-Bound Crystal | ATP-Bound MD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P74-26 | 8.08 | 8.64 ± 0.10 | 6.54 | 6.54 ± 0.03 |

| T4 | 9.35* | 9.45 ± 0.07 | 9.55* | 7.11 ± 0.01 |

| Sf6 | 7.91 | 7.63 ± 0.06 | 7.90 | 7.91 ± 0.07 |

| P74-26 D149E | - | - | - | 7.21 ± 0.10 |

| T4 D255E | - | - | - | 9.22 ± 0.20 |

TerLT4 crystal structures are of the WB D255E/E256D double mutant; D255E is directly involved in this measurement.

The active site geometry described above leads to “multibody” interactions, whereby the WB (D/E) not only positions the WA (T/S) such that its oxygen points towards Mg2+, but could also polarize its hydroxyl group to increase the strength of the coordination interaction with the Mg2+ ion. Moreover, we find that the WB Asp and WA (T/S) interaction is promoted by ATP binding. Specifically, apo state simulations of TerLT4 and TerLP74−26 predict a 9.5 and 8.6 Å backbone distance between the WB Asp and the WA (T/S) respectively, which shortens to 7.1 and 6.5 Å upon ATP binding (Table 2). Thus, the Walker motifs close around the Mg2+•ATP complex as part of the tight-binding transition (Figure S1). In contrast, the backbone distance does not change much from apo to ATP-bound state in the TerLSf6 system because the hydrogen bond between WB E118 and WA S29 is maintained in the apo state in both crystal structure and MD simulations [19].

Null WB Asp Mutant Simulations.

We next performed simulations of TerLT4-D255N and TerLP74−26-D149N mutant enzymes generated in silico to model the null TerLλ-D178N mutation studied experimentally. Unlike the WT proteins, these variants do not support the formation of a hydrogen bonding network which directly connects the WA and WB motifs discussed above. Rather, the δ-positive NH2 group promotes interactions with exposed backbone oxygen atoms which repositions the mutant WB Asn sidechain to the WB side of the binding pocket (Figure 9D-E); this increases the distance between the WA and WB motifs (Table 2). Notably, the Asp→Asn mutation also hinders the movement of the conserved WA Arg (the “arginine toggle”) into the binding pocket, which has been previously shown to be a crucial step in the tight-binding transition [49] (Figure S2 A-D). Accordingly, the lid subdomain of the ATP-bound Asp→Asn mutants is positioned like apo WT enzymes and not rotated as observed in the ATP-bound WT enzymes (Figure S3). This agrees with the experimental assignment that the Asp→Asn mutation not only affects ATP hydrolysis, but also impairs the tight-binding transition.

Functional WB Asp Mutant Simulations.

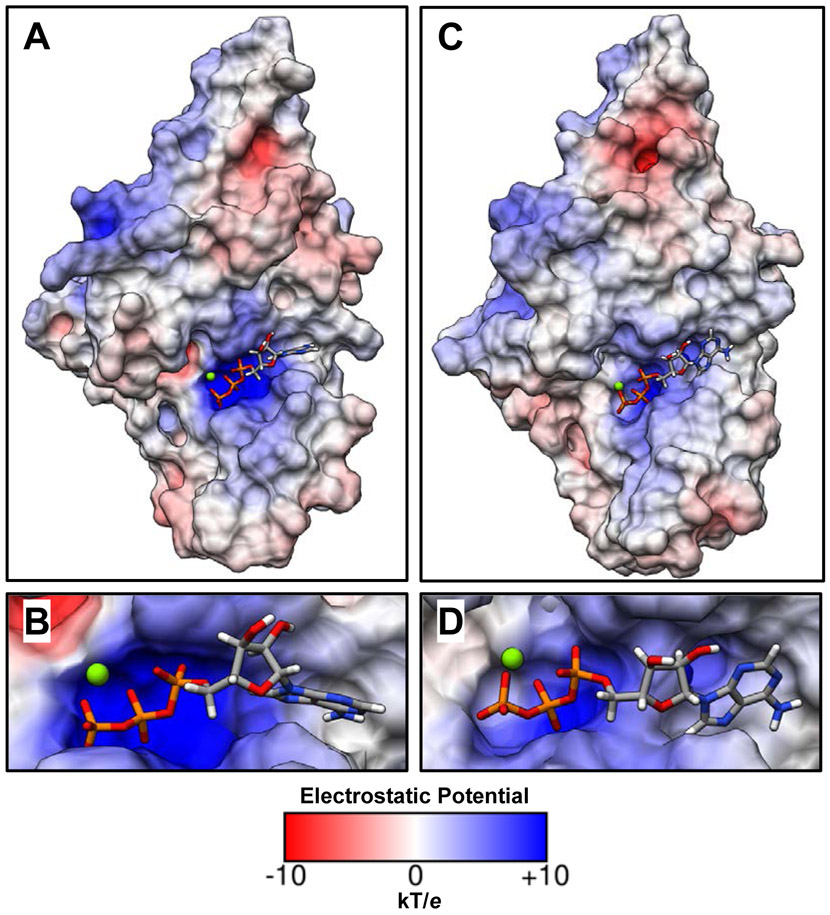

Finally, we performed simulations of TerLT4-D255E and TerLP74−26-D149E mutant enzymes to model the analogous TerLλ-D178E mutation studied experimentally. Simulations of both mutant systems predict defects which can account for a slowed rate of hydrolysis, via two distinct mechanisms. First, our simulations predict that the longer side chain in TerLT4-D255E forms a new interaction with the critical WA lysine K166 (Figure 9F, Figure S4). This causes the WA motif to improperly position the γ-phosphate of ATP, which in turn increases the distance between the γ-phosphate and the catalytic glutamate residue (Figure S5). Notably, a similar interaction between D255E and K166, along with the subsequent mis-coordination of γ-phosphate, are also observed in the crystal structure of the TerLT4-D255E/E256D double mutant enzyme (Figure S6). In contrast, TerLP74−26-D149E simulations do not predict that the mutant D149E would interact with the critical WA K43. Instead, the mutation is found to disrupt the ability of the WB residue to properly chelate Mg2+ through a water molecule. The mutant side chain directly chelates the Mg2+ ion, which displaces WA S44 and prevents it from coordinating with the Mg2+ ion (Figure 9G). Although this direct interaction does not significantly increase the distance between the catalytic glutamate and the γ-phosphate as observed in TerLT4-D255E simulations, the positive electrostatic potential within the binding pocket is reduced (Figure 10). This result implies the electron density on the γ-phosphate may not be as strongly polarized towards its surrounding oxygen atoms as in WT, which would destabilize the transition state and slow hydrolysis. Importantly, the WT-like interaction between the catalytic glutamate and the arginine toggle is conserved in both TerLT4-D255E and TerLP74−26-D149E (Figure S2E-F), suggesting that this mutation does not impair the tight-binding transition as dramatically as its D149N counterpart. Thus, our results discussed above suggest two distinct mechanisms by which the WB Asp→Glu change could impair the hydrolysis chemical step.

Figure 10. Electrostatic potential of WT and mutant P74-26 TerL binding pockets.

(A) The solvent-excluded surface of the WT P74-26 TerL ATPase domain colored according to its electrostatic potential. (B) A close up of the WT ATP binding pocket. (C) The solvent-excluded surface of the WB Asp→Glu variant P74-26 TerL ATPase domain colored according to its electrostatic potential. (D) A close up of the Asp→Glu variant ATP binding pocket. When compared to the WT binding pocket (B), the Asp→Glu binding pocket (D) has reduced positive electrostatic potential around the γ-phosphate of ATP due to the rearrangements described in Figure 9G. This could reduce the polarization of the γ-phosphate and destabilize the transition state, explaining the observed impairment of ATP hydrolysis observed experimentally in lambda phage.

Discussion

The data presented above clearly demonstrate that residues 174-VAGYD-178 in TerLλ are essential to motor function and phage development, and strongly support the WB motif assignment. More importantly, the results provide mechanistic insight into the role each residue plays in protein folding, motor assembly, and catalytic activities required to package the viral genome.

The TerLλ Hydrophobic Quartet.

WB residues 174-VAGY−177 are theorized to function in the folding and stability of the core β-sheet of the ATPase domain [45]. Thus, it is not surprising that most mutations strongly affect virus development, presumably due to protein folding defects and/or perturbations in the positioning of critical ATP binding (D178) and catalytic (E179) residues. Consistent with this hypothesis, almost all changes in the hydrophobic residues are profoundly defective in sponsoring λ phage assembly and many are devoid of in vivo endonuclease activity, an indication that the mutant proteins fail to fold properly. Interestingly, the observed degree of lethal phenotypes in TerLλ contrasts sharply with results observed in the phage T4 system where many WB hydrophobic mutants showed no evidence of assembly defects and many conservative changes are tolerated [45]. Similar differences in tolerance to residue changes were observed in studies of phage T4’s WA motif [25]. It is unclear why TerLT4 is more plastic than TerLλ, but speculative possibilities are: (1) many substitutions in TerLλ affect protein folding and/or stability while TerLT4 is more robust structurally; 2 (2) The λ motor is only known to function as a heterooligomer of TerL plus TerS subunits both in vitro and in vivo, whereas in vitro it has been found that the T4 motor can function as a pentamer of TerL only. Thus, there may be an additional layer of structural complexity in the λ motor that requires functional interactions with TerS and DNA and that may be more sensitive to mutation; (3) The expression of TerLλ is limited [58] and may be significantly lower than that of TerLT4 in vivo. This may reflect important life style differences between the two phages. TerLT4 endonuclease activity is toxic to E. coli [54, 59]. For a virulent phage such as T4, every infection kills the host cell, so production of a high level of TerLT4 is inconsequential. In contrast, temperate phages such as λ must allow lysogenization, which requires that a toxic level of TerLλ expression be avoided [59, 60]. Consequently, TerLλ expression during a productive λ infection is very low and a mutant enzyme with a partial defect in folding or assembly is expected to have a more detrimental effect on phage yield.

Among the viable WB mutants in TerLλ, we note that A175L is cold-sensitive and the 174-VA−175→AV is cold compromised, i.e., makes tiny plaques at the cold temperature. This mirrors observations with TerLT4 in which several WB mutants were found to be cold-sensitive [45]. One interpretation is that the activity of ATPase center has specific sequence requirements, beyond simple hydrophobicity, that are perturbed by mutation of residues within the quartet. Specifically, these residues may serve to properly position the Mg2+-coordinating D178 residue and the adjacent catalytic E179, and perhaps allow dynamic mobility to these residues to efficiently catalyze hydrolysis. Within this context, it is interesting that a variety of motor translocation phenotypes were observed in enzymes with altered hydrophobic residues in the optical tweezer studies, as discussed next.

In contrast to the lethal mutations in the hydrophobic quartet discussed above, the Terλ-A175L mutant, which increases residue hydrophobicity and side chain bulk, is viable and exhibits only minor impairments in DNA translocation. Our findings support that A175 plays a role in ATP binding, presumably by helping to position the nearby D178 residue that coordinates the Mg2+ of Mg2+•ATP. The near-WT level of activity of the A175L mutant suggests that A175 does not play as significant a role in protein folding as the other three hydrophobic WB residues.

The Conserved WB Aspartate.

TerLλ-D178 is the predicted conserved WB residue that chelates Mg2+•ATP to appropriately position the bound γ-phosphate for hydrolysis [45]. Our genetic studies found that all tested changes of TerLλ-D178 are lethal, with the most conservatively changed mutant, D178E, being a conditional (cold-sensitive) lethal mutant. In addition to structural defects associated with this mutant, single molecule studies reveal defects in DNA translocation dynamics and shed further light on the nature of the defect. First, the significant decrease in motor velocity without significant increase in slipping suggests that the defect is not due to a slowed ATP tight binding transition, but is caused by perturbation of the activity of the adjacent catalytic carboxylate (E179) and a concomitant decrease in ATP hydrolysis [25, 49]. Within our kinetic model (Figure S1), slowing the chemical step (ATP hydrolysis) slows the motor without causing increased slipping [25], as is observed.

Second, change D178E causes a ~3-fold increase in the average frequency of motor pauses and ~2-fold increase in average duration of pauses (Figure 7). Intermittent pausing of the WT motor increases with decreasing [ATP], which we previously attributed to an off-pathway state in which terminase intermittently grips DNA tightly despite not undergoing the ATP tight binding change [25]. However, since D178E’s infrequent slipping is inconsistent with a slowed ATP tight binding conformational change (vide supra), its increased pausing must be attributed to a different effect. A similar phenotype was observed previously in response to change R79K in the WA motif. Our interpretation is that both mutations result in intermittent binding of ATP in a misaligned orientation that allows tight DNA gripping but does not permit catalysis of hydrolysis, as proposed previously [25]. This finding implicates residue TerLλ-D178 as playing an important role in proper ATP alignment, which has also been suggested previously for the analogous residue in TerLT4 [45]. The temperature sensitive behavior of the D178E enzyme in the genetic studies, in which plaques were only obtained at 37°C and 42°C, may be related to these effects. Increased plasticity of the active site with increasing temperature may allow proper alignment of the bound Mg2+•ATP into a catalytically competent conformation and a functional packaging motor to accommodate the TerLλ-D178E change.

Despite the cold-sensitive phenotype, TerLλ-D178E mutant terminase sponsors viable phage production at elevated temperatures. Thus, mutant WB glutamate (E) in TerLλ functions as well as the WT aspartate (D), likely because both are acidic residues that have similar size and negative charge. Within this context, sequence alignments predict that some terminases such as those of phages SPP1 and Sf6, classified as “Deviant I” types, utilize a Glu at this position rather than an Asp [45]. Our finding that the TerLλ-D178E mutant can sponsor translocation, albeit impaired at room temperature, supports the notion that the Glu residues in those systems could function analogously to TerLλ-D178.

The biochemical characterization of the TerLλ-D178N mutant enzyme is also informative. This mutation does not affect folding or stability of the protein nor the maturation activity of the enzyme. The D→N change selectively affects ATP hydrolysis and thus packaging. Interestingly, there is a kinetic lag in the single-turnover time course which can be attributed to a rate limiting step prior to the chemical step that is not observed in the WT enzyme. Prior studies demonstrated a similar ATPase kinetic lag in the WA TerLλ-R79A mutant enzyme that also exhibited a kinetic lag in cos-cleavage activity. In that case, the mutation caused a slow rate of motor assembly on viral DNA [25]. In contrast, while there is a distinct kinetic lag in single turnover ATP hydrolysis by the D178N mutant enzyme, there is no indication of a lag in the cos-cleavage time course (not shown). Thus, the nature of the lag in ATP hydrolysis must be distinct from that observed with the WA mutant enzyme characterized previously and we suggest that it is the result of slowed ATP-binding. Since the rate constant obtained in the kinetic fit is significantly less than that expected for diffusion-controlled ATP binding (~107– 108 M−1•sec−1; [61]), it is likely that this represents the ATP tight binding transition discussed above, and the kinetic data provide a rate of (1.7 ± 0.2) x 104 M−1sec−1 for this conformational change (Table 1).

Insights from simulations.

Our MD simulations identify a stable hydrogen bond between the conserved WB (D/E) and WA (T/S) residues in TerL proteins that is promoted by Mg2+•ATP binding. In fact, simulations suggest that the backbones of the TerL proteins may be tuned to the size of the WB (D/E) side chain such that this interaction is conserved upon ATP binding. That is, TerLSf6 positions its “deviant” WB Glu ~1.4 Å farther away from the WA Ser than TerLP74−26 positions its WB Asp to accommodate a 1.5 Å longer side chain. Structural and mutagenesis studies suggest that a similar hydrogen bond between the conserved WB Asp residue and the conserved WA Ser is crucial for function in the MRP1-NBD1 multi-drug resistance ATPase [62].

Our MD studies on the two null mutant model systems, TerLT4-D255N and TerLP74−26-D149N, intended to be analogous to the TerLλ-D178N mutant studied experimentally, further suggest that this hydrogen bond is critical for motor function. The mutant residue no longer interacts with the WA (T/S) across the binding pocket, but instead remains isolated on the WB side due to new interactions between the mutant NH2 group and exposed backbone oxygen atoms. Loss of motor function is, in part, attributed to the loss of this hydrogen bond.

Our MD studies on the two functional mutant model systems, TerLT4-D255E and TerLP74−26-D149E intended be analogous to the TerLλ-D178E mutant studied experimentally, predict distinct mechanisms for the disruptive effects on packaging. However, we propose that the effect of the TerLλ-D178E mutation is more likely to be like that predicted for TerLP74−26 D149E, in which the longer side chain directly chelates Mg2+ and perturbs its interaction with the conserved WA serine residue. In contrast, simulation of TerLT4-D255E predicts that a new interaction is formed with the critical WA K166, consistent with mutant structural data.

We propose that the distinction in motor function between the two TerLλ variants (Asp→Asn and Asp→Glu) rests primarily in the tight-binding transition; while kinetic analysis implied that the Asp→Asn mutation impairs the tight-binding transition, the Asp→Glu mutation does not. One possible explanation is revealed by the MD simulations. While the Asp→Glu mutation does indeed affect binding pocket coordination, the mutant Glu exhibits defective coordination: it is predicted to directly chelate Mg2+ in TerLP74−26 D149E or to hydrogen bond to the critical WA Lys in TerLT4 D255E. In contrast, the Asp→Asn mutant does not directly participate in these types of interactions.

Engineering Improved Motor.

Unlike all other TerL mutants examined to date, the TerLλ-G176S enzyme sponsored translocation at a rate equal to or slightly higher than the WT rate and remarkably exhibited 5x higher processivity (Figure 8). This behavior may be contrasted with those of previously studied WA mutants TerLλ-Y82A and TerLλ-S83T; both enzymes similarly exhibited increased processivity but significant decreases in motor velocity. The TerLλ-G176S change thus causes an overall enhancement in function - increased processivity with no concomitant decrease in motor velocity. On the surface, this suggests that the motor can be engineered to have improved function through a single residue change. However, since slipping of the WT motor is quite infrequent, the improved processivity exhibited by TerLλ-G176S does not result in a significant increase in the overall packaging rate (Figure 7). This suggests there would not be much natural selection pressure for the motor to evolve in this manner. Moreover, the higher slipping exhibited by the WT motor could even be advantageous to slow packaging to help mitigate the formation of unfavorable or “jammed” non-equilibrium states of DNA packaged into the procapsid [63-65]. In any case, we note that the ability to artificially engineer the motor to have improved processivity (reduced slipping) could be useful for applications in biotechnology, such as in the use of DNA translocating motors in nanopore-based single DNA molecule sequencing [66].

Conclusions

We have examined the role of WB motif residues in viral packaging motor function using a combination of genetic, biochemical, biophysical, and computational techniques. Our studies validate the proposed WB motif assignment in phage λ terminase and identify several mutants with partly-impaired DNA translocation and viral assembly activities that shed light on the role of WB residues in motor function. Only a few residue changes are tolerated, and single molecule measurements show that WB residues play a role in determining motor velocity, processivity, and pausing. Our experimental results, and molecular dynamics simulations of related TerL enzymes, support the prediction that the conserved WB aspartates play an important role in ATP binding and further suggest that the hydrophobic WB residues play a role in positioning the catalytic glutamate to facilitate catalysis of ATP hydrolysis.

Materials and Methods

Microbiological techniques

Mutations affecting WB codons were introduced using splicing-by-overlap-extension and mutagenic PCR techniques to generate the desired codon changes [67]. Care was taken to avoid mutant codons rarely used in E. coli. Mutations were introduced into the complementation plasmid, pJM5alt, and the expression plasmid, pQH101alt, using standard molecular genetic manipulations. Complementation plasmid pJM5alt contains the λ DNA segment extending from the late gene promotor through cos and the terminase genes. Expression plasmid pQH101alt contains the terminase genes downstream of the strong early gene promotors PR and PL [68]. Transfer of mutations into both plasmids was facilitated by introduced restriction enzyme sites created by silent mutations in the A gene [25].

The method for introducing terminase mutations into phage λ [69] is described here briefly. The phage into which mutations were crossed was λ-P1:5R KnR cI857 nin5 cos2, hereafter called λ cos2. The cos2 mutation is a lethal deletion of cosN, the cohesive end site, so λ cos2 was maintained as a prophage. λ cos2 produces the heat-labile cI857 repressor and enters the lytic cycle when a culture growing at 30°C is shifted to 42°C to inactivate the repressor. After heat induction for 15 min, the culture is aerated at 37°C until cell lysis. The cos2 mutation prevents DNA packaging, so no infectious virions are produced. To cross an A gene mutation into phage, a mutation-containing derivative of pJM5alt is introduced into E. coli (λ cos2). The segment of λ DNA in pJM5alt includes cosN+. If induced λ cos2 rescues cosN+ from the plasmid, the resulting phage DNA can be packaged to form infectious virions. The segment of plasmid DNA recombined into λ cos2 frequently contains the plasmid A gene, including an A mutation. The lysate from such a cross is used to infect E. coli and resulting lysogens are selected by plating for kanamycin-resistant (KnR) transductants. KnR transductants are screened for inability to produce viable phages and/or sequencing the appropriate segment of the A gene.

Virus yield measurements were carried out as describe previously [25]. Note that in the complementation assay, the yield of the test phage (λ cI857 red3 Aam11 Aam32) was in the range from 6-to-10 phages/induced cell. The low yield is as expected for a red− phage in a recA− host [70].

Biochemical Methods.

Terminase expression, purification and structural characterization was performed by published procedures [25, 53]. The cos-cleavage, DNA packaging and ATPase assays were performed as previously described [25, 71, 72].

Single-Molecule Methods

The optical tweezers instrument was calibrated as described previously [73, 74] and samples were prepared and single-molecule measurements were conducted as described previously [25, 57, 75].

Simulation Methods

100 ns long, all-atom, explicit solvent simulations were performed in triplicate using Amber16. Systems were at 150 mM salt concentration, 310 K, and 1 bar as described previously [49]. WB Asp→Asn and Asp→Glu mutations were introduced to the TerLT4 and TerLP74-26 systems in the same manner as the catalytic Glu→Asp mutations described previously [49]. Electrostatic potential surfaces were calculated with the APBS extension implemented in UCSF Chimera [76].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. David Baker (University of Washington) for access to the CD spectrometer. This work was supported by NIH awards R01-GM088186 and R01-GM118817. A.V. was supported by NSF-REU program in the Department of Microbiology at The University of Iowa under Grant No. DBI-7290775. Computational resources were provided by the NSF XSEDE Program under grant ACI-1053575 and the Duke Computer Cluster.

Footnotes

For simplicity, we use TerL with a superscript designating the virus of origin; e.g., the large terminase subunit of T4 is designated TerLT4 and that of λ is designated TerLλ, etc.

We note, however, that the lethal TerLλ-D178N change does not cause a major folding defect and any mis-folding would be highly localized within the ATP binding pocket of the enzyme.

REFERENCES

- [1].Rao VB, Feiss M. Mechanisms of DNA packaging by large double-stranded DNA viruses. Annual review of virology. 2015;2:351–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chemla YR, Smith DE. Single-molecule studies of viral DNA packaging In: Rao V, Rossmann MG, editors. Viral Molecular Machines. Boston, MA: Springer; 2012. p. 549–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Catalano CE. Viral Genome Packaging Machines: Genetics, Structure, and Mechanism. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hetherington CL, Moffitt JR, Jardine PJ, Bustamante C. Comprehensive Biophysics Comprehensive Biophysics: Academic Press; 2012. p. 420–46. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Casjens SR. The DNA-packaging nanomotor of tailed bacteriophages. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2011;9:647–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Earnshaw WC, Casjens SR. DNA packaging by the double-stranded DNA bacteriophages. Cell. 1980;21:319–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Smith DE, Tans SJ, Smith SB, Grimes S, Anderson DL, Bustamante C. The bacteriophage phi29 portal motor can package DNA against a large internal force. Nature. 2001;413:748–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fuller DN, Raymer DM, Kottadiel VI, Rao VB, Smith DE. Single phage T4 DNA packaging motors exhibit large force generation, high velocity, and dynamic variability. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16868–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fuller DN, Raymer DM, Rickgauer JP, Robertson RM, Catalano CE, Anderson DL, et al. Measurements of single DNA molecule packaging dynamics in bacteriophage lambda reveal high forces, high motor processivity, and capsid transformations. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:1113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kindt J, Tzlil S, Ben-Shaul A, Gelbart WM. DNA packaging and ejection forces in bacteriophage. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13671–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Purohit PK, Inamdar MM, Grayson PD, Squires TM, Kondev J, Phillips R. Forces during bacteriophage DNA packaging and ejection. Biophys J. 2005;88:851–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Speir JA, Johnson JE. Nucleic acid packaging in viruses. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;22:65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sun S, Kondabagil K, Draper B, Alam TI, Bowman VD, Zhang Z, et al. The Structure of the Phage T4 DNA Packaging Motor Suggests a Mechanism Dependent on Electrostatic Forces. Cell. 2008;135:1251–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Liu S, Chistol G, Hetherington CL, Tafoya S, Aathavan K, Schnitzbauer J, et al. A Viral Packaging Motor Varies Its DNA Rotation and Step Size to Preserve Subunit Coordination as the Capsid Fills. Cell. 2014;157:702–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chistol G, Liu S, Hetherington CL, Moffitt JR, Grimes S, Jardine PJ, et al. High degree of coordination and division of labor among subunits in a homomeric ring ATPase. Cell. 2012;151:1017–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Moffitt JR, Chemla YR, Aathavan K, Grimes S, Jardine PJ, Anderson DL, et al. Intersubunit coordination in a homomeric ring ATPase. Nature. 2009;457:446–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chemla YR, Aathavan K, Michaelis J, Grimes S, Jardine PJ, Anderson DL, et al. Mechanism of force generation of a viral DNA packaging motor. Cell. 2005;122:683–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Black LW. Old, new, and widely true: The bacteriophage T4 DNA packaging mechanism. Virology. 2015;479:650–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhao H, Christensen TE, Kamau YN, Tang L. Structures of the phage Sf6 large terminase provide new insights into DNA translocation and cleavage. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:8075–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hilbert BJ, Hayes JA, Stone NP, Xu R-G, Kelch BA. The large terminase DNA packaging motor grips DNA with its ATPase domain for cleavage by the flexible nuclease domain. Nucleic acids research. 2017;45:3591–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hilbert BJ, Hayes JA, Stone NP, Duffy CM, Sankaran B, Kelch BA. Structure and mechanism of the ATPase that powers viral genome packaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E3792–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tsay JM, Sippy J, DelToro D, Andrews BT, Draper B, Rao V, et al. Mutations altering a structurally conserved loop-helix-loop region of a viral packaging motor change DNA translocation velocity and processivity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24282–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tsay JM, Sippy J, Feiss M, Smith DE. The Q motif of a viral packaging motor governs its force generation and communicates ATP recognition to DNA interaction. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14355–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Harvey SC. The scrunchworm hypothesis: Transitions between A-DNA and B-DNA provide the driving force for genome packaging in double-stranded DNA bacteriophages. J Struc Biol. 2015;189:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].delToro D, Ortiz D, Ordyan M, Sippy J, Oh CS, Keller N, et al. Walker-A Motif Acts to Coordinate ATP Hydrolysis with Motor Output in Viral DNA Packaging. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:2709–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Berndsen ZT, Keller N, Smith DE. Continuous Allosteric Regulation of a Viral Packaging Motor by a Sensor that Detects the Density and Conformation of Packaged DNA. Biophys J. 2015;108:315–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Migliori AD, Keller N, Alam TI, Mahalingam M, Rao VB, Arya G, et al. Evidence for an electrostatic mechanism of force generation by the bacteriophage T4 DNA packaging motor. Nature Communications. 2014;5:4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Duffy C, Feiss M. The large subunit of bacteriophage lambda’s terminase plays a role in DNA translocation and packaging termination. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:547–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Rao VB, Mitchell MS. The N-terminal ATPase site in the large terminase protein gp17 is critically required for DNA packaging in bacteriophage T4. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;314:401–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Alam TI, Draper B, Kondabagil K, Rentas FJ, Ghosh-Kumar M, Sun S, et al. The headful packaging nuclease of bacteriophage T4. Molecular microbiology. 2008;69:1180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mao H, Saha M, Reyes-Aldrete E, Sherman MB, Woodson M, Atz R, et al. Structural and Molecular Basis for Coordination in a Viral DNA Packaging Motor. Cell Rep. 2016;14:2017–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Xu R-G, Jenkins HT, Antson AA, Greive SJ. Structure of the large terminase from a hyperthermophilic virus reveals a unique mechanism for oligomerization and ATP hydrolysis. Nucleic acids research. 2017;45:13029–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Erzberger JP, Berger JM. Evolutionary relationships and structural mechanisms of AAA+ proteins. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 2006;35:93–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Burroughs AM, Iyer LM, Aravind L. Comparative genomics and evolutionary trajectories of viral ATP dependent DNA-packaging systems. Genome dynamics. 2007;3:48–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lyubimov AY, Strycharska M, Berger JM. The nuts and bolts of ring-translocase structure and mechanism. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:240–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hanson PI, Whiteheart SW. AAA+ proteins: have engine, will work. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2005;6:519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Allemand J-F, Maier B, Smith DE. Molecular motors for DNA translocation in prokaryotes. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2012;23:503–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Liu S, Chistol G, Bustamante C. Mechanical operation and intersubunit coordination of ring-shaped molecular motors: insights from single-molecule studies. Biophysical journal. 2014;106:1844–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kjeldgaard M, Nyborg J. Refined structure of elongation factor EF-Tu from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:721–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Müller CW, Schulz GE. Structure of the complex between adenylate kinase from Escherichia coli and the inhibitor Ap5A refined at 1.9 A resolution. A model for a catalytic transition state. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:159–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cremo CR, Grammer JC, Yount RG. Direct chemical evidence that serine 180 in the glycine-rich loop of myosin binds to ATP. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6608–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rao VB, Feiss M. The Bacteriophage DNA Packaging Motor. Ann Rev Genetics. 2008;42:647–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Walker JE, Saraste M, Runswick MJ, Gay NJ. Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sun S, Kondabagil K, Gentz PM, Rossmann MG, Rao VB. The structure of the ATPase that powers DNA packaging into bacteriophage t4 procapsids. Molecular cell. 2007;25:943–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mitchell MS, Rao VB. Functional analysis of the bacteriophage T4 DNA-packaging ATPase motor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:518–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Mitchell MS, Rao VB. Novel and deviant Walker A ATP-binding motifs in bacteriophage large terminase-DNA packaging proteins. Virology. 2004;321:217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Goetzinger KR, Rao VB. Defining the ATPase center of bacteriophage T4 DNA packaging machine: requirement for a catalytic glutamate residue in the large terminase protein gp17. Journal of molecular biology. 2003;331:139–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Story RM, Steitz TA. Structure of the recA protein–ADP complex. Nature. 1992;355:374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]