Abstract

Neonatal lupus erythematosus is a rare disorder with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. The disease can affect several systems, including the skin, heart, liver, and bone marrow. Thus, a recognition of its different presentations is vital for making a diagnosis. We describe the case of a neonate diagnosed with neonatal lupus, presenting with an acute onset of erythematous skin lesions as the sole manifestation. The patient’s mother was healthy with no known medical history or relevant family history

Keywords: lupus, pediatric dermatology, neonatology, pediatric rheumatology, pediatrics and neonatology

Introduction

Neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) is a rare condition that develops from the passive maternal transfer of antibodies across the placenta to the fetus. It can manifest with a wide range of manifestations [1,2]. We describe the case of a neonate diagnosed with NLE, presenting with an acute onset of erythematous skin lesions as the sole manifestation of the disease. The patient’s mother was healthy with no known medical history or relevant family history.

Case presentation

The patient is a male infant who was born full term at 39 weeks via spontaneous vaginal birth. His birth history was otherwise unremarkable. The mother is a 26-year-old female, gravida 3 para 2 with no reported significant past medical history or family history. The mother had an unremarkable pregnancy and reports having completed all of her prenatal visits.

The patient was admitted to our institution at 25 days of age when he developed an acute onset of skin lesions on the face, upper neck, and abdomen. The mother reports the skin lesions developed three days after the patient's first exposure to direct sunlight when she took him for a walk that lasted about 35 minutes.

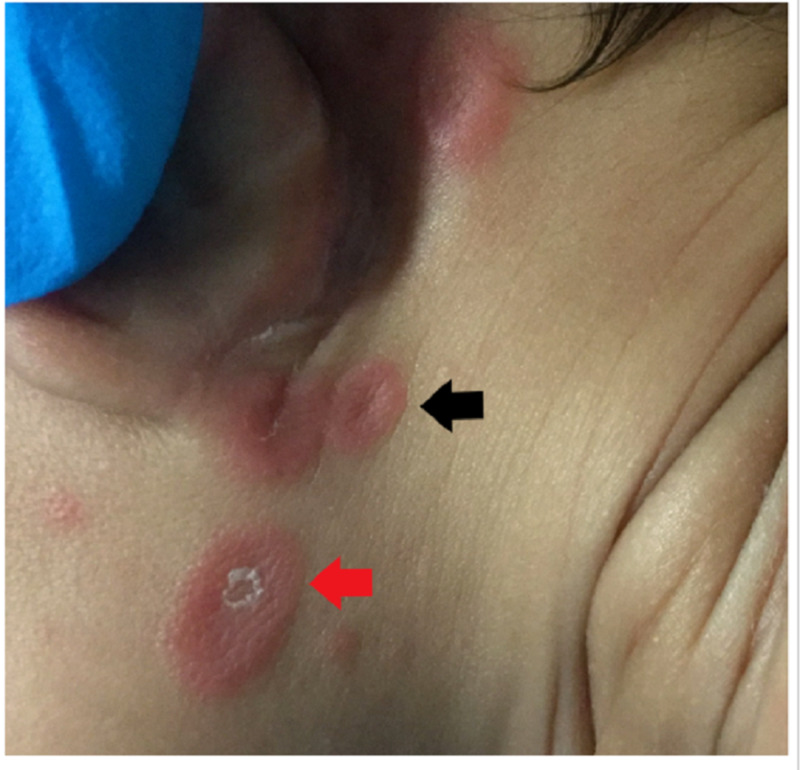

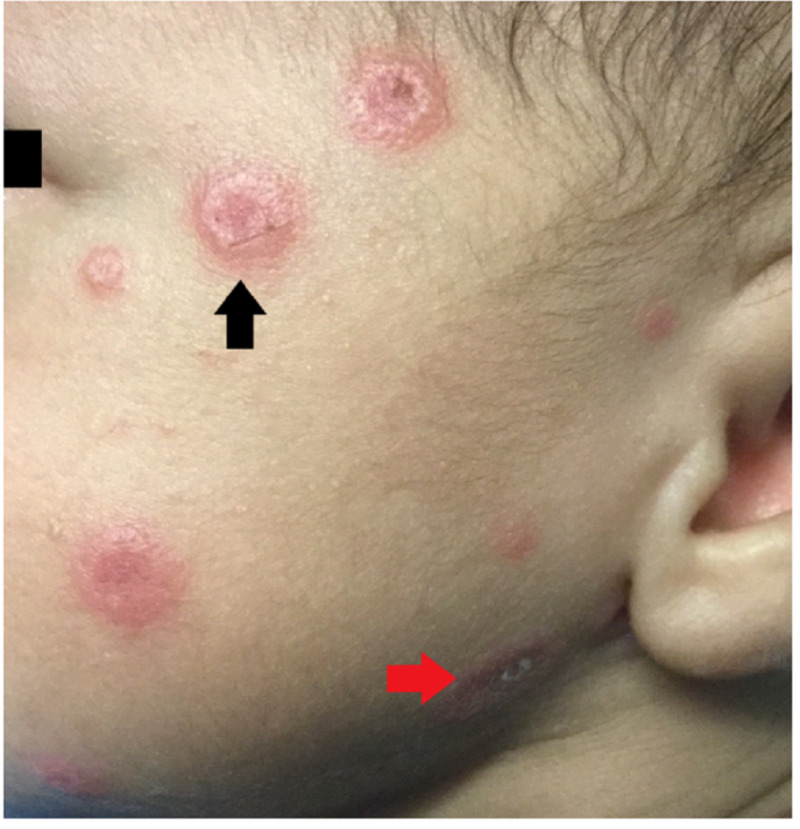

On physical exam, the patient was noted to be awake and active, the skin had multiple lesions described as circumscribed plaques of different sizes, erythematous, annular with central atrophy, and raised borders. Some of the plaques presented skin desquamation. The lesions were located over the post-auricular area, face, and scalp (Figures 1-3). The lesions were non-pruritic and non-migrating, and did not involve the peripheral areas of the body.

Figure 1. Annular erythematous lesions with central atrophy and raised borders observed behind the ear (black arrows).

Figure 3. The patient's neck area showing annular erythematous plaques with central atrophy and raised borders (black arrow) and an erythematous desquamating plaque (red arrow).

Figure 2. An example of an annular erythematous plaque with central atrophy and raised borders (black arrow) and an erythematous desquamating lesion (red arrow) observed in the patient's face.

The patient was otherwise doing well, afebrile, breastfed exclusively, and growing well. On admission, his baseline labs, including complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, hepatic panel, and urine analysis, were unremarkable. An electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed and did not show evidence of any conduction abnormalities.

To confirm the diagnosis, the child and mother were tested for antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and anti-Ro/anti-La. The child had positive anti-Ro/anti-LA and ANA positive in high titers with speckled pattern, and the mother tested positive for anti-Ro/anti-La but at the time was healthy and did not have any signs or symptoms of autoimmune disease

The dermatology team was consulted and recommended topical triamcinolone to hasten the resolution of the skin lesions.

After starting the treatment, the lesions were found to be improving. The patient was discharged on hospital day 3 and scheduled to be seen by cardiology as an outpatient.

Discussion

NLE is a rare condition and often present a diagnostic challenge. The differential diagnoses can range from benign self-resolving conditions to life-threatening systemic illnesses.

The most common manifestation of NLE is cutaneous involvement, which occurs in about 40% of patients [1,2]. There are multiple conditions with similar dermatologic findings, such as atypical erythema multiforme, erythema annulare, urticaria, tinea corporis, familial annular erythema, and erythema gyratum athopicans, and should be considered as differential diagnosis [3,4].

These conditions can be differentiated by the timing of onset, the morphology, and distribution of the rash along with associated symptoms and history.

The distribution of the lesions on our patient is typical for NLE which usually affects sun-exposed areas, and the lesions are usually exacerbated by ultraviolet light exposure [5]. The timing of the lesions can be present at birth but typically tend to occur between four to six weeks after birth, as in this patient. Other manifestations can include cardiac abnormalities, such as varying degrees of heart block, cardiomyopathy, or congenital abnormalities. Hepatobiliary abnormalities like liver failure, transaminase elevations, and hyperbilirubinemia are observed in about 10% of patients. Hematologic manifestations like thrombocytopenia and neutropenia have been reported as well [1-6].

NLE results from transplacental transfer of maternal autoantibodies to the fetus. The autoantibodies that are usually involved are anti-Ro, anti-La, or anti-RNP. In patients with cutaneous manifestations or with atrioventricular block, NLE is diagnosed when the mother has positive anti-Ro/anti-La antibodies. In this case, both the patient and mother tested positive for the antibodies [7,8].

The mother of the child may have an autoimmune disorder such as lupus, Sjogren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, or other connective tissue disorders in about 75% of the cases, but it is also important to note that in some cases as in this case, the child's mother can be asymptomatic and healthy at the time of diagnosis [2,7,8].

Once the diagnosis is established, these neonates should be screened for conduction abnormalities with an ECG in all neonates. Approximately 25% of patients present cardiac involvement. Follow up with an ECG and an echocardiogram is recommended for those with first degree and second degree. It is important to note that up to 2% of infants develop atrioventricular blocks within the first month [9].

Avoidance of sun exposure is the mainstay of management for cutaneous manifestations. The management of NLE is primarily expectant, but complete resolution of the skin lesions takes within six to nine months [5,6,10]. Topical steroids have been used to expedite the resolution of the lesions.

The counseling for parents of children diagnosed with NLE is utterly important. Children who have had NLE are at increased risk of autoimmune disease later in life, and the degree of the risk is still not clear as most data come from small case series, but it has been estimated to be around 2% [11,12]. The parents should be aware that subsequent pregnancies can be affected as well, and it has been reported that about 20% of subsequent pregnancies can be affected by NLE [11,12].

Conclusions

The presence of annular erythematous skin lesions in a neonate has a wide array of differentials. This case highlights the classic skin findings of NLE. A thorough history and physical exam are key for diagnosing this condition, being that skin involvement is the most common manifestation. Testing of the child and mother with ANA and anti-Ro/anti-La antibodies should be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

This patient did not present with any cardiac conduction abnormalities; nevertheless, all patients with a confirmed diagnosis should obtain an ECG and have cardiology follow-up as outpatients. The patient’s skin lesions improved after five days with the avoidance of sun exposure, and the use of topical steroids in the affected area.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Neonatal lupus syndromes. Tseng CE, Buyon JP. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9031373/ Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1997;23:31–54. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neonatal systemic lupus erythematosus syndrome: a comprehensive review. Vanoni F, Lava SAG, Fossali EF, et al. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:469–476. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Educational paper: neonatal skin lesions. Hulsmann AR, Oranje AP. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:557–566. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-1956-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Annular, erythematous skin lesions in a neonate. Palit A, Inamadar AC. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2012;3:45–47. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.93504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cutaneous manifestations of neonatal lupus without heart block: characteristics of mothers and children enrolled in a national registry. Neiman AR, Lee LA, Weston WL, Buyon JP. J Pediatr. 2000;137:674–680. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.109108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neonatal lupus: what we have learned and current approaches to care. Klein-Gitelman MS. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18:60. doi: 10.1007/s11926-016-0610-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Transplacentally transmitted autoimmune disorders of the fetus and newborn: pathogenic considerations. Giacoia GP. South Med J. 1992;85:139–145. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199202000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Autoantibodies of neonatal lupus erythematosus. Lee LA, Frank MB, McCubbin VR, Reichlin M. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8006461/ J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:963–966. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12384148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Progress in the pathogenesis and treatment of cardiac manifestations of neonatal lupus. Izmirly P, Saxena A, Buyon JP. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29:467–472. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cutaneous sequelae in neonatal lupus: a retrospective cohort study [Epub ahead of print] Levy R, Briggs L, Silverman E, Pope E, Lara-Corrales I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neonatal lupus: long-term outcomes of mothers and children and recurrence rate. Brucato A, Franceschini F, Buyon JP. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9307852. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1997;15:467–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neonatal lupus: follow-up in infants with anti-SSA/Ro antibodies and review of the literature. Zuppa AA, Riccardi R, Frezza S, et al. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]