Abstract

Background

While cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for many children and adolescents with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), therapeutic response is variable. Fear conditioning and extinction are central constructs underlying exposure-based CBT. Fear extinction learning assessed prior to CBT may be a useful predictor of CBT response for guiding treatment decisions.

Methods

Sixty-four youth who participated in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of CBT with and without d-cycloserine (DCS) completed a fear conditioning task. Skin conductance response (SCR) scores were used to measure fear acquisition and extinction to determine whether extinction learning could predict CBT response.

Results

CBT responders and non-responders appeared to acquire conditioned fear SCRs in a similar manner. However, differences between treatment responders and non-responders emerged during the extinction phase. A responder (responder, non-responder) by conditioned stimulus type (CS+, CS-) interaction showed that CBT responders differentiated the stimulus paired with (CS+) and without (CS-) the unconditioned stimulus correctly during early and late extinction, whereas the CBT non-responders did not (p=.004).

Conclusions

While the small sample size makes conclusions tentative, this study supports an emerging literature that differential fear extinction may be an important factor underlying clinical correlates of pediatric OCD, including CBT response.

Keywords: OCD, pediatric, skin resistance, fear extinction, CBT

1. INTRODUCTION

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) among children and adolescents has a prevalence of approximately 1–2% (Douglass, Moffitt, Dar, McGee, & Silva, 1995; Zohar, 1999), is a significant public health problem, causes impairment in academic, social and family functioning, and left untreated is frequently unremitting into adulthood (Leonard et al., 1993; Piacentini, Peris, Bergman, Chang, & Jaffer, 2007; Swedo, Rapoport, Leonard, Lenane, & Cheslow, 1989). Several randomized controlled trials examining cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention (E/RP; see McGuire, 2015 for a meta-analytic review) have provided strong empirical support for treating pediatric OCD (Freeman et al., 2014; POTS, 2004; Storch et al., 2007). Unfortunately, not all children respond to CBT. The Nordic Long-term OCD Treatment Study (NordLOTS) reported that, of 269 youth enrolled and treated with a standardized 14 session manualized protocol, 177 (66%) youth were considered responders (CY-BOCS ≤15) and 120 (45%) were considered remitted (CY-BOCS ≤10) (Højgaard et al., 2017). In a recent multisite trial examining the efficacy of augmenting CBT with d-cycloserine (DCS) in 142 youth with OCD using a rigorous standardized CBT protocol, 61% responded (CY-BOCS ≤14) and 48% remitted (CY-BOCS ≤12) (Storch et al., 2016). No moderators or predictors of treatment outcome were identified in either study that would guide clinicians in determining which youth were most likely to respond to CBT. While earlier studies identified several clinical correlates such as symptom severity, family accommodation or psychiatric comorbidity with CBT response (Garcia et al., 2010; Storch et al., 2008), replication is needed and no studies have identified any biological markers that predict response. Given the time, cost, effort and limited availability of well-trained pediatric CBT practitioners, such information could be very helpful.

One potential predictor of CBT effectiveness is fear extinction (FE) learning. In the cognitive-behavioral model, the mechanisms of fear acquisition and extinction play an important conceptual role in explaining symptom development and maintenance as well as treatment of OCD (Abramowitz, Taylor, & McKay, 2009). Conditioned fear occurs when an emotionally neutral stimulus (conditioned stimulus, CS) is paired with an aversive unconditioned stimulus (US) and then itself becomes aversive by association (CS+), in the absence of the US. Subsequent exposure to the CS+ produces a conditioned response (CR) such as fear/distress. During extinction learning, the fear response to the CS+ declines through repeated exposure without the US when anxiety is not otherwise assuaged by compulsive behavior and extinction is allowed to occur. CBT employs the principle of fear extinction learning through repeated exposure without engagement in safety behaviors (e.g., avoidance, compulsive washing) and absence of the feared outcome. Extinction does not eradicate the initial CS-US association, but rather represents a new “CS-no US” learned association that inhibits the previous conditioned fear response (Myers & Davis, 2007).

In an examination of conditioned fear and extinction in youth with OCD, McGuire and colleagues (McGuire et al., 2016) administered a differential fear-conditioning task to 41 youth aged 8–17 years (OCD: n=19; community controls: n=22). No group differences were found during fear acquisition (FA), with both groups exhibiting differential fear conditioning of a skin conductance response (SCR) when exposed to the CS+, compared to the CS-. However, youth with OCD exhibited a persistent fear to the CS+ relative to the CS- during the extinction phase providing evidence for a deficit in inhibitory learning. In the largest study to date that examined fear acquisition and extinction learning using SCR in youth with OCD prior to treatment with protocol-driven CBT, participants with OCD exhibited a stronger orienting SCR to initial presentations of stimuli, larger SCRs to a visual CS+ during fear acquisition, persistently larger SCRs overall, and a larger differential SCR to the CS+ (compared to CS-) during extinction, suggesting impaired inhibitory learning, compared with healthy controls (Geller et al., 2017). Inconsistent findings may be attributed to differences in sample characteristics, fear conditioning procedures, outcome measures, and the nature of the aversive unconditioned stimulus.

Given the deficits in inhibitory learning observed during extinction learning among youth with OCD across the two studies, parallel deficits in the development of the inhibitory response following E/RP may exist, reducing the effect of standardized CBT, even when delivered by well-trained practitioners using a structured protocol. Indeed, deficits in extinction learning could explain some of the variability in response to CBT and identify a subset of affected youth less likely to respond to such treatment. While no prior study has examined the impact of extinction learning on treatment outcomes in pediatric OCD, Waters and Pine (2016) compared physiological responses to fear acquisition and extinction in 32 non-anxious children and 44 children with anxiety disorders who were then treated with group CBT. Similar to the non-anxious comparison group, treatment responders displayed elevated SCRs during acquisition that declined significantly across extinction trial blocks. Hhowever, during extinction, treatment non-responders showed somewhat reduced SCRs that did not significantly change over trial blocks. Interestingly, the subjective arousal ratings of treatment non-responders did not differ from those of treatment responders and the non-anxious group. The SCR results suggest that extinction learning may moderate CBT response.

To our knowledge, no study has prospectively examined fear acquisition and extinction learning as predictors for CBT response in youth with OCD. If youth with OCD who demonstrate fear acquisition and extinction learning similar to healthy controls benefit from standard CBT approaches, whereas youth with impairments in fear acquisition and extinction learning do not, quantitative assay of SCR extinction learning may serve as a useful biomarker in guiding treatment selection, diverting some youth to alternate interventions to achieve optimal benefit (Riemann, Kuckertz, Rozenman, Weersing, & Amir, 2013; Shechner, Rimon-Chakir, et al., 2014).

The present study examined the predictive value of SCRs during fear acquisition and extinction learning assessed before treatment in a well-characterized sample of youth with OCD who participated in a randomized double blind trial of protocol-driven CBT augmented by DCS or placebo, using a novel computer-administered differential conditioning task (Lau, Lissek, & Nelson, 2008; Lissek et al., 2005). Our primary aim was to determine if fear extinction learning could be used to identify those children more likely to benefit from CBT using responder status as a categorical outcome. We hypothesized that children who demonstrated deficits in extinction learning would be less likely to respond to CBT compared to youth who showed robust extinction learning. A secondary aim was to examine the dimensional relationship between the rate and magnitude of extinction learning and subsequent improvement with CBT, as measured by the CGI-I scores. We predicted that more pronounced extinction learning would correlate with more rapid and complete treatment response.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 64 youth recruited from two sites (Massachusetts General Hospital [MGH] and the University of South Florida [USF] conducted under the approval of each participating institution’s Institutional Review Board, and with subjects and their legal guardians providing informed consent/assent. Full details of this multisite trial (1R01MH093402, R01MH093381) examining whether d-cycloserine could augment the short-term efficacy of CBT to a greater extent than placebo is described elsewhere (Storch et al., 2016). An exploratory aim of this multisite randomized clinical trial examined potential predictors and moderators of treatment outcome, including fear extinction learning using a computer-administered paradigm to assess fear acquisition and extinction (Lau et al., 2008; Lissek et al., 2005).

In brief, participants represent a subset of 142 youth who met the following inclusion criteria: a primary or co-primary diagnosis of OCD, between 7 and 17 years of age (inclusive), and a moderate level of obsessive-compulsive symptoms as evidenced by a CY-BOCS total score ≥ 16. All participants received a comprehensive psychiatric assessment that included the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (Kaufman et al., 1997). After completing an initial battery of assessments that included a fear conditioning task, eligible participants were randomly assigned to receive either CBT augmented with DCS or placebo. Youth were assessed by independent evaluators naive to treatment condition using clinician-rated scales before the 4th CBT session (study visit 5), 7th CBT session (study visit 8), and within one week after the 10th CBT session (study visit 12).

2.2. Measures

Fear Conditioning Computer Task

Full details of this assessment are reported elsewhere (Geller et al., 2017). Prior to starting CBT, a differential fear-conditioning paradigm was used in which participants learned to associate an unconditioned stimulus (US) with a paired conditioned stimulus (CS+), but not an unpaired conditioned stimulus (CS-). The US consisted of a loud 95 decibel scream delivered via headphones and a female fearful facial expression on the screen. This paradigm used two female faces with neutral facial expressions to serve as conditioned stimuli (Lau et al., 2008), and included three phases: pre-acquisition (4 presentations of each stimulus face), acquisition (10 presentations of each stimulus face), and extinction (8 presentations of each stimulus face). The CSs were presented for 8 seconds with an inter-stimulus interval ranging from 20–26 seconds. During the pre-acquisition phase, participants passively viewed the to-be CS+ and CS- without any presentation of the US. In the acquisition phase, one of the female faces (CS+) was paired with the US for 8 out of 10 presentations, whereas the other female face (CS-) was not paired with the US. The US (scream along with the fearful expression face) was presented immediately following CS+ offset and remained on for three seconds. During the extinction phase, the CS+ and CS- were presented repeatedly in the absence of the US. Children were permitted to exit the task at any time by raising their hand if they became too anxious to continue. This task has previously been used in studies with children who have anxiety disorders (Britton et al., 2013; Lau et al., 2011), as well as healthy control samples of youth (Britton et al., 2013; Glenn et al., 2012) and adults (Britton et al., 2013; Haddad, Xu, Raeder, & Lau, 2013).

Skin conductance response served as the primary dependent measure of fear conditioning. A computer and Coulbourn Modular Instrument System recorded SCR level throughout the task using a Coulbourn Isolated Skin Conductance Coupler. Skin conductance level was recorded through two 9-mm Ag/AgCl electrodes filled with isotonic paste and placed on the hypothenar surface of the participant’s non-dominant hand. The participant’s SC level was digitized by a Coulbourn Lablinic Analog to Digital Converter; 10 samples per second were retained for calculating SCR.

Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) (Scahill et al. 1997)

The CY-BOCS is a clinician-administered interview that assesses OCD symptom severity over the past week. The CY-BOCS total score has demonstrated good reliability, validity, and treatment sensitivity (Scahill et al. 1997; Skarphedinsson et al. 2017; Storch et al. 2010).

Clinical Global Impression of Improvement (CGI-I)(Guy, 1976)

The CGI-I is a 7-point clinician-rated scale that assesses global improvement from baseline, which ranges from “very much improved” to “very much worse”. A score of “much improved” or “very much improved” is considered a positive treatment response.

2.3. Data Analysis

Following the method used by Orr et al. (Orr et al. 2000), a SCR score for each CS presentation was calculated by subtracting the average SC level during the 2-second interval immediately preceding CS onset from the peak SC level during the 8-second CS interval. A SCR score for each US presentation was calculated by subtracting the average SC level during the last 2 seconds of the CS interval from the peak SC level during the 5-second interval following US onset. To address skewness in the SCR distribution, a square-root transformation was applied to the absolute values of all SCRs prior to analysis, with the minus sign replaced if the SCR was negative. Analyses of pre-acquisition, acquisition and extinction phases included the 4, 10 and 8 presentations (respectively) of the CS+ and CS-. Trial blocks were created by averaging across every two trials (of the same stimulus type); this step produced for each stimulus (CS+ and CS-), 2 trial blocks for the pre-acquisition phase, 5 trial blocks for the acquisition phase, and 4 trial blocks for the extinction phase. For each phase, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with SCR (√μS) as the dependent measure and outcome group (CBT responder vs. non-responder) as a between-group factor, stimulus type (CS+, CS-) as a within-subjects factor, and trial block as the repeated measure. Dependent sample t-tests were used to compare the groups’ SCR to the CS+ and CS- during the pre-acquisition phase. The unconditioned SCR during the acquisition phases was examined using a repeated-measure ANOVA, with CBT responder status as a between-group factor and trial block as the repeated measure. For all repeated-measure ANOVAs, significance levels reflect the Greenhouse-Geisser correction for sphericity.

To examine the relationship between change in extinction learning scores and rate of improvement, survival analysis was computed with CGI-I scores as the outcome. Significance was determined using two-tailed tests and an alpha of 0.05.

3. THEORY/CALCULATION

Predictors and moderators of response to any intervention and to CBT in particular among youth affected with OCD are lacking. Biomarkers that do not rely on subjective reports and that discriminate treatment responders from non-responders could be a powerful method to direct treatment. Psychophysiological measures of fear extinction provide a potential biomarker assay supported by the extant literature and have construct validity as articulated by Cronbach and Meehl (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955). Fear conditioning and extinction assays could be developed in a cost and effective and time efficient manner and be used as part of a preliminary evaluation prior to treatment assignment.

4. RESULTS

Demographic and baseline assessment measures are shown in Table 1 by CBT responder status. There were no group differences in terms of age (F(1, 62) = .44, p = .510), sex (χ2(1) = .46, p = .496), race (χ2(1) = .18, p = .675) or CY-BOCS total scores at visit 5 (randomization) (F (1, 62) = .07, p = .788). For current diagnoses, there were no statistically significant group differences in rates of depression (χ2(1) = 2.11, p = .146), anxiety (χ2(1) = .03, p = .859) or tics (χ2(1) = .18, p = .675). There were no significant group differences for children using SSRIs (χ2(1) = 2.63, p = .105), antipsychotics, tic (χ2(1) = 1.12, p = .289) or ADHD medications (χ2(1) = .06, p = .809).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Correlates of Responders and Non-Responders to CBT in Youth with OCD

| Variable | Total | Responder | Non-responder |

|---|---|---|---|

| N enrolled | 64 | 51 | 13 |

| Years of Age M (SD) | 12.79 (2.92) | 12.67 (3.02) | 13.28 (2.54) |

| Sex (% Female) | 53.1 | 50.9 | 61.5 |

| Race (% White) | 89.1 | 88.2 | 92.3 |

| CYBOCS M (SD) | 24.98 (5.93) | 24.88 (6.11) | 25.38 (5.38) |

| Current Comorbid Diagnoses (%) | |||

| Depression | 17.2 | 13.7 | 30.8 |

| Anxiety | 40.6 | 41.2 | 38.5 |

| Tics | 10.9 | 11.8 | 7.7 |

| Medication Use (%) | |||

| SSRI | 21.88 | 17.7 | 38.5 |

| Antipsychotic | 3.1 | 1.9 | 7.7 |

| ADHD/Tic | 6.3 | 5.9 | 7.7 |

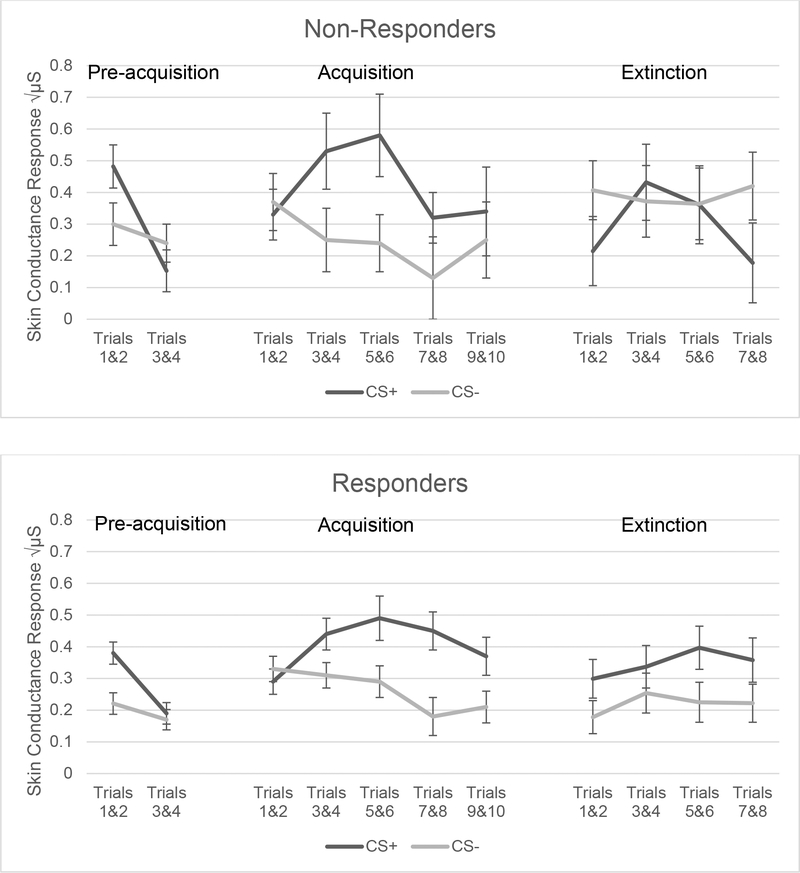

Illness severity at evaluation as measured by CY-BOCS scores did not correlate with differences between CS+ and CS- SCR scores during pre-acquisition (r = .130), acquisition (r= .136) or extinction (r = .036) indicating that baseline OCD severity was not a factor influencing fear acquisition and extinction learning. There were significant main effects for conditioned stimulus type during the acquisition phase, as would be expected, with CS+ producing a larger SCR (Table 2). SCR magnitude did not differ as a function of responder status during acquisition, an important finding demonstrating that both groups (treatment responders and non-responders) showed comparable acquisition of a conditioned fear SCR, which allows for a valid comparison of responder status during subsequent extinction learning. During extinction learning, the responder and non-responder groups showed comparable SCR magnitudes overall; however, a significant interaction between stimulus type (CS+ and CS-) and CBT responder group indicates that treatment responders demonstrated better discrimination of the CS+ and CS- compared to non-responders (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2.

SCR in each trial block as a function of responder status, stimulus type (CS+ or CS−) and their interaction.

| Trials | Stimulus Type CS+/CS− | Effect as p value Responder Status | Interaction | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-acquisition Phase | ||||

| Trials 1–2 | F (1, 61) = 20.14, p < .001 | F (1, 61) = 1.65, p = .203 | F (1, 61) = .15, p = .698 | 64 |

| Trials 3–4 | F (1, 58) = .96, p = .331 | F (1, 58) = .05, p = .825 | F (1, 58) = 2.48, p = .121 | 60 |

| Acquisition Phase | ||||

| Trials 1–2 | F (1, 49) = .98, p = .328 | F (1, 49) = .29, p = .594 | F (1, 49) = .57, p = .454 | 51 |

| Trials 3–4 | F (1, 45) = 14.99, p < .001 | F (1, 45) = .01, p = .923 | F (1, 45) = 2.44, p = .125 | 47 |

| Trials 5–6 | F (1, 41) = 15.69, p < .001 | F (1, 41) = .07, p = .788 | F (1, 41) = 1.03, p = .316 | 43 |

| Trials 7–8 | F (1, 39) = 9.96, p = .003 | F (1, 39) = .72, p = .400 | F (1, 39) = .26, p = .814 | 41 |

| Trials 9–10 | F (1, 38) = 2.68, p = .110 | F (1, 38) = .001, p = .982 | F (1, 38) = .16, p = .692 | 40 |

| Extinction Phase | ||||

| Trials 1–2 | F (1, 37) = .28, p = .602 | F (1, 37) = .23, p = .638 | F (1, 37) = 4.92, p = .033 | 39 |

| Trials 3–4 | F (1, 37) = 1.31, p = .260 | F (1, 37) = .45, p = .506 | F (1, 37) = .05, p = .820 | 39 |

| Trials 5–6 | F (1, 36) = 2.58, p = .117 | F (1, 36) = .17, p = .681 | F (1, 36) = 2.79, p = .103 | 38 |

| Trials 7–8 | F (1, 36) = .66, p = .422 | F (1, 36) = .01, p = .939 | F (1, 36) = 8.48, p = .006 | 38 |

Figure 1.

SCR Responses across Fear Acquisition and Extinction Trial Blocks by Stimulus and Responder Group

Table 2 also shows a marked drop off in subjects who participated in all phases of the fear conditioning protocol (38 subjects or 60% of subjects completed the entire extinction phase), indicating that the task was highly aversive, especially following exposure to the US. Twenty-six children dropped out during the fear conditioning protocol, nearly all during the acquisition phase. However, CBT response rate in children who dropped out did not differ from the rate among those completing the extinction phase.

The trial block by stimulus interaction also shows significant SCR change with consecutive presentations during acquisition for trials 3–8 (p<.002). In both pre-acquisition and acquisition phases, all interactions with CBT responder status are non-significant (with the noted exception of trial block 5 & 6 (p<.03). This indicates that both groups habituated and acquired a conditioned SCR to a comparable extent over trials and stimulus type. However, during extinction, a significant CBT responder by stimulus type interaction was present for trial blocks 1 & 2 and 7 & 8 (p = .01). This indicates that the CBT responder and non-responder groups showed different patterns of SCRs to the CS+, compared to the CS- (see Table 2, Figure 1).

Given the aims of the primary study to explore the value of DCS on extinction learning, as a first step we analyzed all data with DCS group assignment as a variable in the model (Table 3). As can be noted in Table 3, there was a significant interaction between DCS group assignment and stimulus type for the first trial block (trials 1&2) of the extinction phase, (p=.017). Consequently, following the primary analyses described, we next conducted a second set of analyses using DCS group as a covariate in the respective models to determine whether DCS group assignment might have influenced the results.

Table 3.

SCR for each phase of the fear conditioning protocol, stimulus type, d-cycloserine group, and responder status

| Pre-acquisition phase (n = 60) | Trials | ||||

| Effect | 1&2 | 3&4 | |||

| Stimulus Type (ST) | <.001 | .305 | |||

| ST X Group | .208 | .630 | |||

| ST X Respond | .755 | .106 | |||

| ST X Respond X Group | .913 | .200 | |||

| Group | .258 | .458 | |||

| Respond | .171 | .299 | |||

| Acquisition Phase (n = 40) | Trials | ||||

| Effect | 1&2 | 3&4 | 5&6 | 7&8 | 9&10 |

| Stimulus Type (ST) | .335 | <.001 | <.001 | .002 | .109 |

| ST X Group | .386 | .446 | .469 | .736 | .898 |

| ST X Respond | .584 | .129 | .266 | .546 | .706 |

| ST X Respond X Group | .571 | .050 | .029 | .215 | .654 |

| Group | .028 | .466 | .084 | .510 | .044 |

| Respond | .338 | .911 | .640 | .463 | .782 |

| Group X Respond | .067 | .750 | .198 | .702 | .654 |

| Extinction Phase (n = 38) | Trials | ||||

| Effect | 1&2 | 3&4 | 5&6 | 7&8 | |

| Stimulus Type (ST) | .553 | .305 | .121 | .390 | |

| ST X Group | .017 | .240 | .748 | .508 | |

| ST X Respond | .012 | .977 | .104 | .010 | |

| ST X Respond X Group | .318 | .753 | .860 | .705 | |

| Group | .606 | .015 | .020 | .598 | |

| Respond | .717 | .306 | .465 | .901 | |

| Group X Respond | .778 | .148 | .189 | .423 | |

An analysis of extinction learning differences between CBT responders and non-responders is shown in (see Table 2). For trial block 1, there was a statistically significant interaction between stimuli and CBT responder status (N=39, p=.033). In early extinction (trials 1 & 2) treatment responders show a significantly larger SCR to the CS+ (M = .32, SE = .06) than to the CS- (M = .20, SE = .06; t (29) = 2.07, p = .048). In other words, CBT responders discriminated aversively conditioned (CS+) faces from faces not paired (CS-) with the US; whereas, non-responders showed no initial SCR difference between the CS+ (M = .22, SE = .11) and CS- (M = .41, SE = .10; t (8) = −1.11, p = .300). This suggests a failure of the CBT non-responders to recognize the CS- as a safe signal. When individual trials were examined to determine the direction of effects within trial block 1, the interaction between stimuli and CBT responder status was significant (F(1, 37) = 6.49, p = .015). The treatment responders showed smaller, but non-significant, SCRs to the CS-, compared to CS+ (t (28) = 1.25, p = .222) for both initial extinction trials 1 and 2; whereas, non-responders showed a larger, marginally significant, SCR to the CS-, compared to CS+, for trial 1 (t (8) = −1.92, p = .091). For trial 2, the interaction between stimulus type and responder status was not statistically significant (F(1, 37) = 0.97, p = .332), as were none of the within-group differences as a function of stimulus type. CBT non-responders continued to show larger SCRs to the CS- (Table 2).

At the end of the extinction phase (trials 7 & 8) the responder by stimulus interaction remained significant (n=38, p=.006). For CBT responders, the SCR difference between CS+ and CS- (CS+: M = .36, SE = .07, CS-: M = .22, SE = .06; t(28) = 1.96, p = .061) was not significant; however, the non-responders showed significantly larger SCRs to the CS-, compared to CS+ (CS+: M = .18, SE = .10, CS-: M = .42, SE = .12; t (8) = −4.38, p = .002). Thus, CBT non-responders continued to show poor stimulus discrimination throughout the extinction learning task, i.e., all exposures following acquisition were responded to as potentially aversive, regardless of whether they had previously been associated with the US. CBT non-responders exhibited larger SCRs to the CS- at the end of extinction, but their SCR to the CS+ was smaller than that recorded in the treatment responders. Finally, after adjusting for DCS group assignment using ANCOVA, we found that the interaction between stimulus type (CS+, CS-) and CBT responder status remained statistically significant (F (1, 36) = 6.90, p = .013), as did the respective analyses of each trial block (see Table 4). Thus, adjusting for DCS group assignment status did not impact the findings.

Table 4.

SCR for extinction phase by stimulus type, responder status and their interaction with and without DCS group assignment as a covariate

| Effect as p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect/Trials | Stimulus Type CS+/CS− | Responder Status | Interaction | n |

| Extinction Phase | ||||

| Trials 1–2 | .602 | .638 | .033 | 39 |

| Trials 3–4 | .260 | .506 | .820 | 39 |

| Trials 5–6 | .117 | .681 | .103 | 38 |

| Trials 7–8 | .422 | .939 | .006 | 38 |

| Extinction Phase with DCS Group Assignment as Covariate | ||||

| Trials 1–2 | .269 | .723 | .013 | 39 |

| Trials 3–4 | .832 | .340 | .986 | 39 |

| Trials 5–6 | .138 | .505 | .098 | 38 |

| Trials 7–8 | .205 | .928 | .009 | 38 |

Note: For trials 1&2, with DCS group as a covariate in the models, the interaction between stimulus and CBT responder status remains statistically significant (F (1, 36) = 6.90, p = .013). Follow-up ANCOVAs with DCS group as a covariate revealed a significant effect of stimulus for the CBT responder group (Mplus = .322, SEplus = .060; Mminus = .204, SEminus = .052; F (1, 28) = 7.34, p = .011), but not for the CBT non-responders (Mplus = .215, SEplus = .116; Mminus = .407, SEminus = .127; F (1, 7) = .01, p = .942).

For trials 7&8, with DCS group as a covariate in the models, the interaction between stimulus and CBT responder status is still statistically significant (F (1, 35) = 7.67, p = .009). Follow-up ANCOVAs with DCS group as a covariate revealed a significant effect of stimulus for the CBT non-responder group (Mplus = .178, SEplus = .107; Mminus = .420, SEminus = .130; F (1, 7) = 10.81, p = .013), but not for the CBT responders (Mplus = .358, SEplus = .074; Mminus = .222, SEminus = .057; F (1, 27) = .26, p = .618).

To examine whether discrimination of CS+ versus CS- stimuli in early extinction could predict CBT response, a survival analysis was conducted for time-to-treatment response predicted by conditioning measures. For this analysis, a CGI-I score of > 4 (much or very much improved) was used from visits 5, 8 and 12 (active E/RP). Thirty children had CGI-I scores above 4 across the double-blind treatment period and nine did not. The difference between SCR scores for CS+ and CS- trials for extinction blocks 1 & 2 was used as a predictor in the analysis. Although not a significant predictor of response status, the scores showed a clear trend toward differences between responders and non-responders (HR = 2.20, 95% CI = .80 – 6.05, p = .127).

DISCUSSION

This study examined conditioned fear acquisition and extinction learning of an SCR in a large cohort of youth with well-characterized OCD treated in a randomized controlled trial using CBT augmented with DCS or placebo. Baseline measures of demographic variables, clinical correlates and severity were not different between youth who responded to CBT and youth who did not. Of 142 youth randomized, 86 (60.5%) were CBT responders defined by a post-treatment CY-BOCS score of ≤ 14 and 110 (77%) were responders defined by a CGI-I score of >4 (much or very much improved) at post treatment. The conditioning task used to assess fear conditioning in these youth (Lau et al., 2008) was poorly tolerated. Sixty-four of the total randomized cohort (44%) completed at least one trial block during fear acquisition and only 38 (27%) completed the entire task through extinction learning. The relatively small number of CBT non-responder completers (9 participants), hampered power to detect differences in responder status as a function of extinction learning.

Our main findings suggest that all youth with OCD, including both treatment responders and non-responders who were assessed with the fear acquisition and extinction task, acquired conditioned fear in a similar manner. However, CBT responders and non-responders did differ in their response to conditioned stimuli during the extinction learning phase of the task. Specifically, CBT responders were better able to discriminate in early extinction trials between the face stimulus paired with an aversive US (CS+) and the face not paired with the US (CS-). In contrast, CBT non-responders showed a poor appreciation between the CS+ and CS- during early and late extinction and did not discriminate between faces paired and not paired with the aversive US. While CBT responders maintained a differential response to the CS+ and CS-, a persistent differential response between the CS+ and CS- throughout extinction is often exhibited by unaffected children and adolescents (Pattwell et al., 2012; Tzchoppe et al. 2014). In comparison, CBT non-responders appeared to exhibit a contingency shift and exhibited fear to the CS- during extinction. A survival analysis to examine the predictive value of the ability to discriminate aversive stimuli during early extinction was not statistically significant, but showed a trend, likely due to low power afforded by the small number of non-responders who were able to complete the task. Dropout rates during the conditioning task did not support the notion that dropouts subsequently did less well with CBT over time. Nor did greater baseline illness severity adversely moderate fear extinction behavior. Our secondary hypothesis that rate and magnitude of extinction learning could predict the degree of treatment response is partly supported by the differences between CBT responders and non-responders in early and late extinction trials.

Our study highlights some of the difficulties in searching for reliable biomarkers to predict treatment response in youth with OCD, even when evidence of the benefits of those treatments are supported by an extensive literature. Of 206 children enrolled in the original treatment study and 142 randomized to receive CBT, only 38 completed the fear conditioning task through the extinction phase. CBT utilizing E/RP is a proven effective mode of treatment for a majority of youth with OCD. Our previous work (Storch et al., 2016) and that of others (Højgaard et al., 2017) show with a high degree of confidence that CBT is often helpful. However, these same studies demonstrate with equal confidence that a substantial minority of youth do not benefit, even when CBT is well delivered in a specialized center using a well-executed protocol.

Finding predictors and moderators of treatment response is an important next step. Given the important role, conceptual and practical, that mechanisms of fear acquisition and extinction play in explaining symptom development, maintenance and treatment in OCD, the study of this trait or capacity in individuals is a logical endophenotype to explore using psychophysiological measures and methods. That such translational approaches are fraught with difficulty in this cohort, i.e. youth with anxiety, is apparent from the conflicting findings in the literature (Craske et al., 2008; Geller et al., 2017; Liberman, Lipp, Spence, & March, 2006; McGuire et al., 2016; Pliszka, Hatch, Borcherding, & Rogeness, 1993; Shechner et al., 2015; Shechner, Hong, Britton, Pine, & Fox, 2014; Waters, Henry, & Neumann, 2009). Evidence suggests that anxious youth exhibit resistance to within-session extinction as evidenced by larger SCRs to the CS+ than to the CS- (i.e., persistence of differential fear learning) (Craske et al., 2008; Liberman et al., 2006; Pliszka et al., 1993; Waters et al., 2009). Yet other studies have reported no significant difference in extinction learning between anxious and non-anxious youth (Shechner et al., 2015; Shechner, Hong, et al., 2014). In our previous work examining fear acquisition and extinction learning in youth with OCD, we have reported on fear extinction findings in particular. Waters and Pine (2016) also found differences during fear extinction in their sample of anxious youth. In the present study, CBT non-responders appeared to generalize fear to non-conditioned stimuli (i.e., the CS-) or to develop an “anticipated contingency shift” in that they anticipated the CS- to now be paired with a scream.

Whether fear conditioning protocols will have clinical utility in guiding treatment for affected youth is unclear given the poor acceptance and tolerance of the procedure, specialized equipment that is required, and time involved in running the test and subsequent analysis. Nonetheless, our findings do support differences in physiological responses during extinction learning of previously conditioned fear between youth who subsequently respond to CBT and those who do not. This suggests that refinement of a conditioning protocol may yet be clinically helpful if its practical limitations can be mitigated. Our findings should be considered within the context of several limitations. Although several significant findings were as expected, e.g. larger SCR to the CS+ face and change in SCR over sequential exposures, some findings were not as expected. The larger SCR to the unpaired CS- stimulus in CBT non-responders is puzzling, although it does align with findings of Waters and Pine (2016). It can be explained as demonstrating a lack of discrimination between the CS+ and CS- in these youth; however, one would have expected to see no differences between faces, rather than somewhat larger responses to the CS-. Further, our survival analysis was not significant when early extinction response was used as a predictor of treatment response and was underpowered, despite robust study enrollment. Although we have not conclusively demonstrated that fear extinction learning is a valid and reliable predictor of treatment response, here we measured only extinction learning and not extinction recall. Extinction learning reflects reductions in fear that occur within a session, whereas extinction recall relates to between-session reductions in fear. When considering subjective distress rather than extinction learning using SCR, there is mixed evidence linking within- and between- session reductions in subjective distress during exposures with treatment outcome of CBT in pediatric OCD (Kircanski & Peris, 2014; Kircanski, Wu, & Piacentini, 2014). Therefore, extinction recall, consolidation and generalization, rather than within-session extinction, may provide better predictors of treatment outcome over a more prolonged treatment course.

Perhaps due to the small number of participants who completed the entire extinction task, our findings do not provide conclusive evidence of discriminant extinction learning between CBT responders and non-responders but should stimulate possible directions for future OCD research. First, replication and extension of these findings with a procedure that is better tolerated is warranted. Second, it would be interesting to examine associations with specific obsessions using a more dimensional approach that can separate “fear-based” symptoms (washing and aggression/harm obsessions) from those not associated with fear (symmetry, “just right” symptoms). Imaging to capture abnormalities in fear circuits and their associated brain regions during extinction learning would be of interest. Our findings of poorer extinction learning in CBT non-responders suggest that incorporation of inhibitory learning in exposure therapy may be especially important (Craske, Liao, Brown, & Vervliet, 2012) and helpful to augment observed inhibitory deficits and maximize the therapeutic benefit for youth with OCD (Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek, & Vervliet, 2014; McGuire & Storch, 2018).

5. CONCLUSIONS

Efforts to identify youth with OCD who can benefit from CBT are important but elusive. Psychophysiological measures as potential biomarkers for treatment response are still experimental but show some promise. While pre-acquisition and fear acquisition SCRs were similar between CBT responders and non-responders, non-responders showed a different fear extinction pattern, compared to responders, replicating findings from previous investigations. If user-friendly paradigms can be developed, they may offer the possibility for more individualized treatment approaches in the future.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under awards 1R01MH093402 and R01MH093381 to the first and last authors. The authors acknowledge Chelsea Ale, Ph.D., Noah Berman, Ph.D., David Greenblatt, M.D., Marni Jacob, Ph.D., Nicole McBride, B.S., Jennifer Park, Ph.D., Julia McQuade, Ph.D., David Pauls, Ph.D., Christine Cooper-Vince, Ph.D., Kathleen Carey, CNS, Anne Chosak Ph.D., Allison Cooperman B.A, Angelina Gómez, B.A., Ashley Brown, B.A., Kesley Ramsey, B.A., Robert Selles, M.A., Abigail Stark, B.A., Alyssa Faro, B.A., and Monica S. Wu, M.A.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Taylor S, & McKay D (2009). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Lancet, 374(9688), 491–499. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60240-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JC, Grillon C, Lissek S, Maxine A, Szuhany KL, Chen G, … Pine DS (2013). Response to learned threat: An fmri study in adolescent and adult anxiety. Am J Psychiatry, 170(December 2010), 1195–1204. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12050651.Response [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Liao B, Brown L, & Vervliet B (2012). Role of inhibition in exposure therapy. J Exp Psychopathology, 3, 322–345. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Treanor M, Conway CC, Zbozinek T, & Vervliet B (2014). Maximizing exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 10–23. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Waters AM, B.R., L., Naliboff B, Lipp OV, Negoro H, & Ornitz EM (2008). Is aversive learning a marker of risk for anxiety disorders in children? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(8), 954–967. 10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ, & Meehl PE (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52(4), 281–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass HM, Moffitt TE, Dar R, McGee R, & Silva P (1995). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in a Birth Cohort of 18-Year-Olds: Prevalence and Predictors. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(11), 1424–1431. 10.1097/00004583-199511000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J, Sapyta J, Garcia A, Compton S, Khanna M, Flessner C, … Franklin M (2014). Family-based treatment of early childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: The pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder treatment study for young children (POTS Jr) - A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(6), 689–698. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AM, Sapyta JJ, Moore PS, Freeman JB, Franklin ME, March JS, & Foa EB (2010). Predictors and moderators of treatment outcome in the pediatric obsessive compulsive treatment study (POTS I). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 1024–1033. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller DA, McGuire JF, Orr SP, Pine DS, Britton JC, Small BJ, … Storch E (2017). Fear conditioning and extinction in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry, 29(1), 75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Klein D., Lissek S, Britton JC, Pine DS, & Hajcak G (2012). The Development of Fear Learning and Generalization in 8 to 13 year-olds. Dev Psychobiol, 54(7), 675–684. 10.1109/TMI.2012.2196707.Separate [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad ADM, Xu M, Raeder S, & Lau JYF (2013). Measuring the role of conditioning and stimulus generalisation in common fears and worries. Cognition and Emotion, 27(5), 914–922. 10.1080/02699931.2012.747428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Højgaard DRMA, Hybel KA, Ivarsson T, Skarphedinsson G, Becker Nissen J, Weidle B, … Thomsen PH (2017). One-Year Outcome for Responders of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(11), 940–947.e1. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, … Ryan N (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircanski K, & Peris TS (2014). Exposure and response prevention process predicts treatment outcome in youth with OCD. J Abnorm CHild Psychol, 43, 543–552. 10.1080/10937404.2015.1051611.INHALATION [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircanski K, Wu M, & Piacentini J (2014). Reduction of subjective distress in CBT for childhood OCD: Nature of change, predictors, and relation to treatment outcome. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(2), 125–132. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J, Lissek S, & Nelson E (2008). Fear conditioning in adolescents with anxiety disorders: results from a novel experimental paradigm. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(1), 94–102. 10.1097/chi.0b01e31815a5f01.Fear [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JY, Britton JC, Nelson EE, Angold A, Ernst M, Goldwin M, … Pine DS (2011). Distinct neural signatures of threat learning in adolescents and adults. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(11), 4500–4505. 10.1073/pnas.1005494108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard HL, Hamburger SD, Swedo SE, Lenane MC, Rettew DC, Bartko JJ, & Rapoport JL (1993). A 2- to 7-Year Follow-up Study of 54 Obsessive-Compulsive Children and Adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 50(6), 429–439. 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820180023003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman LC, Lipp OV, Spence SH, & March S (2006). Evidence for retarded extinction of aversive learning in anxious children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(10), 1491–1502. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissek S, Powers AS, McClure EB, Phelps EA, Woldehawariat G, Grillon C, & Pine DS (2005). Classical fear conditioning in the anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(11), 1391–1424. 10.1016/j.brat.2004.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Lewin AB, Brennan EA, Murphy TK, & Storch EA (2015). A meta‐analysis of cognitive behavior therapy and medication for child obsessive–compulsive disorder: Moderators of treatment efficacy, response, and remission. Depression and anxiety, 32(8), 580–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Orr SP, Wu MS, Lewin AB, Small BJ, Phares V, … Storch EA (2016). Fear Conditioning and Extinction in Youth with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 33(3), 229–237. 10.1002/da.22468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, & Storch EA (2018). An Inhibitory Learning Approach to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Children and Adolescents. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, & Davis M (2007). Mechanisms of fear extinction. Molecular Psychiatry, 12(2), 120–150. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr SP, Metzger LJ, Lasko NB, Macklin ML, Peri T, & Pitman RK (2000). De novo conditioning in trauma-exposed individuals with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(2), 290–298. 10.1037//0021-843X.109.2.290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattwell SS, Duhoux S, Hartley CA, Johnson DC, Jing D, Elliott MD, … & Lee FS (2012). Altered fear learning across development in both mouse and human. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(40), 16318–16323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Peris T, Bergman R, Chang S, & Jaffer M (2007). Functional impairment in childhood OCD: development and psychometrics properties of the Child Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale-Revised (COIS-R). J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol, 36(4), 645–653. 10.1080/15374410701662790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka SR, Hatch JP, Borcherding SH, & Rogeness GA (1993). Classical conditioning in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and anxiety disorders: A test of Quay’s model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21(4), 411–423. 10.1007/BF01261601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POTS. (2004). Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The pediatric ocd treatment study (pots) randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 292(16), 1969–1976. 10.1001/jama.292.16.1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann BC, Kuckertz J., Rozenman M, Weersing VR, & Amir N (2013). Preliminary Augmentation of Youth Cognitive Behavioral and Pharmacological Interventions with Attention Modification: A Preliminary Investigation. Depression and Anxiety, 30(9), 822–828. 10.1002/da.22127.Augmentation [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechner T, Britton JC, Ronkin EG, Jarcho JM, Mash JA, Michalska KJ, … Pine DS (2015). Fear conditioning and extinction in anxious and nonanxious youth and adults: Examining a novel developmentally appropriate fear-conditioning task. Depression and Anxiety, 32(4), 277–288. 10.1002/da.22318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechner T, Hong M, Britton JC, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2014). Fear conditioning and extinction across development: Evidence from human studies and animal models. Biological Psychology, 100(1), 1–12. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechner T, Rimon-Chakir A, Britton JC, Lotan D, Apter A, Bliese PD, … Bar-Haim Y (2014). Attention bias modification treatment augmenting effects on cognitive behavioral therapy in children with anxiety: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(1), 61–71. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Geffken GR, Merlo LJ, Mann G, Duke D, Munson M, … Goodman WK (2007). Family-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: Comparison of intensive and weekly approaches. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(4), 469–478. 10.1097/chi.0b013e31803062e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Merlo LJ, Larson MJ, Geffken GR, Lehmkuhl HD, Jacob ML, … Goodman WK (2008). Impact of comorbidity on cognitive-behavioral therapy response in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(5), 583–592. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816774b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Wilhelm S, Sprich S, Henin A, Micco J, Small BJ, … Geller DA (2016). Efficacy of augmentation of cognitive behavior therapy with weight-adjusted D-cycloserine vs placebo in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(8), 779–788. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedo SE, Rapoport JL, Leonard H, Lenane M, & Cheslow D (1989). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Clinical Phenomenology of 70 Consecutive Cases. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 46(4), 335–341. 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810040041007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschoppe J, Nees F, Banaschewski T, Barker GJ, Büchel C, Conrod PJ, … & Martinot JL (2014). Aversive learning in adolescents: modulation by amygdala-prefrontal and amygdala-hippocampal connectivity and neuroticism. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(4), 875–884.24126454 [Google Scholar]

- Waters AM, Henry J, & Neumann DL (2009). Aversive Pavlovian Conditioning in Childhood Anxiety Disorders: Impaired Response Inhibition and Resistance to Extinction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(2), 311–321. 10.1037/a0015635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AM, & Pine DS (2016). Evaluating differences in Pavlovian fear acquisition and extinction as predictors of outcome from cognitive behavioural therapy for anxious children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 57(7), 869–876. 10.1111/jcpp.12522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar AH (1999). The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. Netherlands: Elsevier Science. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]