Using extracellular vesicles for targeted delivery of IL-10 is an efficient therapeutic strategy against ischemic AKI.

Abstract

Recently, extracellular vesicles (EVs) have been attracting strong research interest for use as natural drug delivery systems. We report an approach to manufacturing interleukin-10 (IL-10)–loaded EVs (IL-10+ EVs) by engineering macrophages for treating ischemic acute kidney injury (AKI). Delivery of IL-10 via EVs enhanced not only the stability of IL-10, but also its targeting to the kidney due to the adhesive components on the EV surface. Treatment with IL-10+ EVs significantly ameliorated renal tubular injury and inflammation caused by ischemia/reperfusion injury, and potently prevented the transition to chronic kidney disease. Mechanistically, IL-10+ EVs targeted tubular epithelial cells, and suppressed mammalian target of rapamycin signaling, thereby promoting mitophagy to maintain mitochondrial fitness. Moreover, IL-10+ EVs efficiently drove M2 macrophage polarization by targeting macrophages in the tubulointerstitium. Our study demonstrates that EVs can serve as a promising delivery platform to manipulate IL-10 for the effective treatment of ischemic AKI.

INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI), an abrupt loss of kidney function, is associated with high in-hospital morbidity and mortality (1). In addition, AKI frequently increases the risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (2). However, there are no definitive therapies to treat established AKI or prevent it from progressing to CKD.

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a powerful immune modulator with strong anti-inflammatory and tissue regenerating capabilities (3). In AKI, studies have shown that IL-10 can protect against ischemia, cisplatin, or ureteric obstruction–induced renal injury by limiting inflammatory cytokine production and immune cell infiltration (4, 5), indicating that IL-10 may be a potential therapy to tackle the current clinical challenges of AKI treatment. However, cytokines are susceptible to chemical and physical instability (6) and inevitably activate leukocytes in the circulation, which may lead to patient harm or reduce the therapeutic efficacy. The key to solve the problem is to improve IL-10 stability and selectively targeting to the injured kidney.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), such as exosomes and microvesicles, are small membrane particles (40 to 1000 nm in size) secreted by cells in a constitutive or inducible manner (7, 8). The released EVs naturally function as intercellular messengers by transporting nucleic acids and proteins to distal or nearby cells (7, 8). Recent research has demonstrated the potential for using EVs as robust and feasible nanocarriers for drug delivery in diverse contexts ranging from chemotherapeutics to gene therapy (9–12). Compared with existing delivery systems, the singular advantage of EVs is their natural origin, which enables them to evade phagocytosis, extend the half-life of the therapeutic agent, and reduce immunogenicity (9, 10). Thus, an EV-based drug delivery system may be an attractive candidate to manipulate IL-10 for the effective treatment of AKI.

Here, we reported an effective method for preparing IL-10–loaded EVs (IL-10+ EVs) that were derived from macrophages and investigated the therapeutic efficacy of IL-10+ EVs in a murine model of ischemic AKI. IL-10+ EVs were able to enhance the stability of IL-10 and effectively target the injured kidney due to the adhesive components including integrin α4β1, α5β1, αLβ2, and αMβ2 on the EV surface. Treatment with IL-10+ EVs significantly ameliorated renal ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury and prevented the AKI to CKD transition by targeting not only macrophages in the tubulointerstitium but also tubular epithelial cells (TECs) in the kidneys. Specifically, we showed that IL-10+ EVs suppressed mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity and consequently promoted mitophagy to maintain mitochondrial fitness in TECs. Our findings strongly supported that the use of EVs as a versatile delivery system for IL-10 as an effective strategy for the treatment of ischemic AKI.

RESULTS

Preparation and characterization of the IL-10+ EVs

To develop IL-10+ EVs, RAW 264.7 macrophages were transfected with a plasmid coding for murine IL-10 and were stimulated with dexamethasone to induce an M2c macrophage phenotype, which is the major source of IL-10 (8, 13). Then, EVs including exosomes and microvesicles in the supernatants were isolated by a centrifugation method. To verify the feasibility and validity of the proposed method, we first transfected red fluorescent protein (RFP)–tagged IL-10 to RAW cells to observe the intracellular distribution of IL-10. As shown in Fig. 1A, copious punctate IL-10 signals were observed in the cytoplasm or near the membrane region, suggesting that IL-10 might be encapsulated in certain subcellular structures. To further confirm the presence of IL-10–positive EVs, immunostaining was performed using CD63 as a marker of multivesicular bodies and exosomes. Colocalization of IL-10 and CD63 was shown not only in cells but also in the extracellular environment (Fig. 1B), suggesting that IL-10 was enriched in multivesicular bodies and could be released via EVs.

Fig. 1. Preparation and characterization of the IL-10+ EVs.

(A) RAW cells were transfected with RFP-tagged IL-10 and then were stimulated with dexamethasone. The intracellular distribution of IL-10 was examined by immunostaining against RFP. The right box is a heatmap visualization of the boxed region. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Immunostaining of IL-10 (green) and the EV marker CD63 (red) in engineered RAW cells. The yellow box is a higher magnification of the boxed region in the merged image. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Western blotting analysis of EV-associated (Alix, CD63, and CD81) and macrophage-associated markers (CD68 and CD206) in IL-10+ EVs. (D) Size distribution and representative TEM images of IL-10+ EVs. (E) A heatmap showing the protein levels (normalized to array reference) of each cytokine obtained from antibody array analysis. M0 EVs, EVs from untreated RAW cells. G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor–α. (F) ELISA analysis of IL-10 in EVs, and Western blotting analysis of IL-10 and IL-10 receptor in IL-10+ EVs (n = 3 or 6). (G) IL-10 mRNA in IL-10+ EVs was measured by real-time quantitative PCR (n = 3). (H and I) Comparison of the stability of IL-10+ EVs and free IL-10 under different conditions, including put in 37° or − 80°C for a week, suspended in pH 5.5 solution for 12 hours. Then, IL-10 concentration was detected by ELISA analysis at different time points (n = 3). Data are presented as means ± SD. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, two-tailed t test (F, G, and I) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (H). BLC, B lymphocyte chemoattractant; IP-10, interferon gamma induced protein 10; I-TAC, interferon-inducible T-cell alpha chemoattractant; KC, C-X-C motif chemokine 1; JE, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MCP-5, monocyte chemoattractant protein-5; MIG, monokine induced by interferon-gamma; MIP-1a, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α; RANTES, regulated on activation, T-cell expressed, and secreted; SDF-1, stromal cell-derived factor 1; TARC, thymus and activation regulated chemokine; TIMP-1, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on monocytes 1.

Next, we isolated the EVs from the supernatants and verified them on the basis of protein markers, size, morphology, and IL-10 content. Western blotting showed that the isolated EVs expressed both EV-associated (Alix, CD63, and CD81) and macrophage-associated proteins (CD68 and CD206) (Fig. 1C). Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) revealed that these EVs had diameters ranging from 10 to 500 nm, with a mean diameter of 134 nm (Fig. 1D). The morphology appeared heterogeneous under a transmission electron microscope (TEM), with a mixture of both small exosome-like and large microvesicle-like particles (Fig. 1D). Cytokine array analysis showed that EVs prepared by the above method contained much higher amounts of IL-10, compared to those from control cells (Fig. 1E and fig. S1A). Consistently, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay showed that IL-10 plasmid transfection resulted in a prominent increase in IL-10 concentration in EVs, and with dexamethasone stimulation, the level of IL-10 could be further enhanced sevenfold (Fig. 1F), as well as the expression of IL-10 receptor and IL-10 mRNA (Fig. 1G). These data suggested that the strategy that we devised for preparing IL-10+ EVs is feasible and valid.

Further, we determined the stability of IL-10+ EVs in our setting and noted that the number of EVs and the IL-10 levels within these EVs did not show noticeable degradation after 7 days of −80°C storage (Fig. 1H and fig. S1B). When compared to free IL-10, EV encapsulation helped to preserve more IL-10 over 7 days of 37°C storage (Fig. 1H). In addition, IL-10 in the EVs was well protected in acid solution (Fig. 1I), which was consistent with previous reports that nucleic acids and proteins show high stability inside EVs (9, 10). Given that the instability of IL-10 has greatly hindered its clinical use (3, 6), the method we devised to deliver IL-10 using EVs can overcome the key translational barrier.

Kidney targeting of IL-10+ EVs

A targeted IL-10 approach can improve its pharmacokinetic properties and limit unwanted side effects. In regard to the treatment of AKI, targeting IL-10 more specifically to the injured kidney should provide therapeutic benefits. EVs have lipid bilayer membranes decorated with multiple ligands and receptors that can interact with target cells, rendering them promising candidates for targeted delivery (14, 15). Therefore, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was performed to assess the protein composition of IL-10+ EVs with their parent cells as the control. The proteomic profiling of IL-10+ EVs resulted in the identification of 1549 distinct proteins, and 367 of them were associated with the plasma membrane (fig. S1C). A functional classification identified proteins involved in transport (42%), signaling (25%), cell adhesion (12%), immunity (10%), and lipid metabolism (9%) (fig. S1D). We found that integrin expression profiles of IL-10+ EVs were more plentiful than those of parent cells (Fig. 2A and fig. S1E), suggesting that integrins are enriched in the EVs. Further, the presence of integrins α4, α5, αL, αM, β1, and β2 in IL-10+ EVs were confirmed through Western blotting (Fig. 2B). Several studies have identified that exosomal integrins (ITGα4β1, ITGα5β1, ITGαLβ2, and ITGαMβ2) can interact with vascular cell adhesion molecule–1, fibronectin, and intercellular adhesion molecule–1 (ICAM-1), respectively, mediating exosome uptake in the inflammatory sites (12, 16). Thus, we proposed that IL-10+ EVs could target into the injured kidney with the help of these unique integrin interactions.

Fig. 2. Kidney targeting of IL-10+ EVs.

(A) LC-MS/MS analysis of the protein composition of IL-10+ EVs, with the parental RAW cells as the control. Integrin expression identified in IL-10+ EVs and parental cells was shown. (B) Western blotting analysis of ITGα4, ITGα5, ITGαL, ITGαM, ITGβ1, and ITGβ2 on IL-10+ EVs. (C to E) For in vivo distribution, mice were injected intravenously with DID-labeled IL-10+ EVs (n = 3). (C) Imaging of fluorescence intensity of indicated organs at 6, 12, 24, 48, and 96 hours after injection (35 min ischemic time). (D) Imaging of fluorescence intensity at 12 hours in IRI kidneys of 20-, 28-, and 35-min ischemic time. (E) Representative confocal images showing the accumulation of DID-labeled IL-10+ EVs in tubules including proximal tubule [aquaporin 1 (AQP1)] and distal tubule [NaCl cotransporter (NCC)], endothelia cells (CD31), and macrophages (CD68) in frozen kidney sections. DT, distal tubule; PT, proximal tubule. Scale bars, 10 μm. (F and G) Cellular uptake of PKH67-labeled IL-10+ EVs in H/R-induced TECs (n = 3). (F) Representative confocal images and quantification of PKH67-labeled IL-10+ EVs in each cell after 12 hours of incubation. Immunostaining of TNF was used to indicate the cellular inflammation. Scale bar, 10 μm. (G) Flow cytometry analysis of the CD54+PKH67+ cells. PE, phycoerythrin. Data are presented as means ± SD. #P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, two-tailed t test (C, E, and F) and one-way ANOVA (D and G).

First, the biodistribution of IL-10+ EVs was investigated by labeling the EVs with 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine perchlorate (DID). In healthy mice receiving IL-10+ EVs intravenously, DID fluorescence was mainly distributed in the liver, with only small amounts in the kidneys (Fig. 2C and fig. S2A). By contrast, renal DID fluorescence was significantly increased in the ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI) group and peaked at 12 hours after injection, whereas there were no noticeable changes in other organs (Fig. 2C and fig. S2A). With the prolongation of ischemia time, the accumulation of IL-10+ EVs in I/R kidneys was increased gradually (Fig. 2D), suggesting that IL-10+ EVs can target into the kidney increasingly with the aggravation of injury. Moreover, it was found that robust amounts of IL-10+ EVs localized to the TECs, endothelial cells, and macrophages (Fig. 2E). Proximal tubules internalized more IL-10+ EVs than distal tubules (Fig. 2E), which might be because proximal TECs are more sensitive to ischemic injury (17). Subsequently, we explored the targeting ability of PKH67-labeled IL-10+ EVs in vitro. Compared with the control cells, the uptake of IL-10+ EVs by hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R)–stimulated TECs was three times more efficient (Fig. 2F). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that PKH67–labeled EVs were mainly taken up by CD54+ (ICAM-1+) cells (Fig. 2G), suggesting that IL-10+ EVs could target ICAM-1 on the injured cells through ITGαLβ2 on the EV surface. These results suggested that IL-10+ EVs exhibited preferential targeting to the injured kidney, both in vivo and in vitro. Our strategy of delivering IL-10 using EVs enhanced both the stability and kidney-targeting of IL-10, which we believe are essential for its use in the treatment of ischemic AKI.

IL-10+ EVs protect against renal I/R injury in mice

To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of IL-10+ EVs, a murine model of renal I/R injury was established, and IL-10+ EVs were administered intravenously after reperfusion and continued every 24 hours for 3 days (Fig. 3A), because three-dose treatment was more effective in protecting tubular injury than those of single or two doses (fig. S3A). Bilateral renal injury resulted in markedly elevated levels of serum creatinine, necrosis and detachment of TECs, cellular debris accumulation, and casts formation in the IRI group, whereas these injury parameters were dose-dependently ameliorated by IL-10+ EV treatment (Fig. 3, B to D). To fully assess the efficacy of IL-10+ EVs, kidney sections were subjected to terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) assays to determine the apoptotic index and stained with anti–kidney injury molecular-1 (KIM-1) antibody for the detection of injured tubules. The results demonstrated that the apoptotic cells were reduced in mice treated with IL-10+ EVs (Fig. 3, E and G), and KIM-1 was also expressed at lower levels in the IL-10+ EV group (Fig. 3, F and H), accompanied by decreased expression of cleaved-caspase-3 (Fig. 3I). Moreover, the mRNA expressions for tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL- 6, IL-1β, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL-2), and CCL-5 were also down-regulated by IL-10+ EVs in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3J). These data suggest that IL-10+ EVs can alleviate murine ischemic AKI.

Fig. 3. IL-10+ EVs protect against renal I/R injury in mice.

(A) Schematic diagram of the experimental design. Briefly, mice were concurrently treated with IL-10+ EVs (100 and 200 μg) or vehicle every 24 hours after renal I/R injury and were euthanized at 3 days after disease induction. (B) Effects of IL-10+ EVs on serum creatinine (n = 10). (C) The quantification of tubular injury based on H&E staining (n = 10). (D) Representative images of H&E staining of renal cortex and medulla. Scale bars, 100 μm. (E and G) Representative images of TUNEL staining and quantification of the apoptotic cells (n = 6). Scale bars, 50 μm. HFP, High power field; (F and H) Representative confocal images and quantification of KIM-1+ tubules (n = 6). Scale bars, 20 μm. (I) Western blotting analysis of caspase-3 in kidney tissues (n = 3). HPF, high power field. (J) real-time quantitative PCR analysis of inflammatory cytokine mRNA levels in kidney tissues (n = 6). Data are presented as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus IRI group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA.

Considering that TECs are the nidus of injury during ischemic AKI (18) and large amounts of IL-10+ EVs were accumulated in the tubules (Fig. 2E), we posited that IL-10+ EVs protected against renal I/R injury, at least in part, through targeting tubular cells. Corroborating our in vivo findings, IL-10+ EVs markedly inhibited H/R-induced apoptosis of TECs in vitro, along with reduced mRNA expression of TNF, IL- 6, and IL-1β when compared to EVs derived from control cells (fig. S3, B and C).

We also evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of IL-10+ EVs in cisplatin-induced AKI and confirmed a significant accumulation of IL-10+ EVs in the injured kidneys including both proximal and distal tubules (fig. S4, A and B). IL-10+ EV administration tended to reduce cisplatin-induced mortality at 96 hours, although without reaching statistical significance (fig. S4D). In addition, the loss of weight, kidney dysfunction, and histological damage were markedly prevented by IL-10+ EV treatment (fig. S4, E to G), suggesting that IL-10+ EVs have therapeutic effects on AKI in different experimental models.

IL-10+ EVs inhibit mTOR signaling and induce mitophagy

Next, we investigated the mechanism by which treatment with IL-10+ EVs ameliorated renal tubular injury. A recent study observed a key role for IL-10 in controlling macrophage metabolism via inhibiting mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) (19); however, it is unclear how IL-10+ EVs act on epithelial cells. We first examined the mTOR signaling in kidney tissues and found that IL-10+ EVs inhibited mTORC1 activation, as indicated by decreased phosphorylation of its downstream targets including S6K, S6, and 4E-BP1 (Fig. 4A). By contrast, IL-10+ EVs led to a notable increase of LC3-II expression (Fig. 4A), which was consistent with the notion that mTORC1 is a master negative regulator of autophagy (20). TEM analysis of kidney cortex confirmed that IL-10+ EVs induced higher levels of autophagosomes and autolysosomes in TECs compared to the IRI group, as well as the number of autophagosomes/autolysosomes enclosed within mitochondria (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, IL-10+ EVs also inhibited mTOR signaling and induced mitophagy in cultured TECs in vitro (fig. S5, A and B). Autophagosomes mature into autolysosomes upon fusion with the lysosome (21). For this reason, we costained for mitochondria and lysosomes and found a significant increase in colocalization of mitochondria with lysosomes after IL-10+ EV treatment (fig. S5C). Collectively, these data clarified that IL-10+ EVs can promote mitophagy in TECs both in vivo and in vitro.

Fig. 4. IL-10+ EVs inhibit mTOR signaling and induce mitophagy to maintain mitochondrial fitness.

(A) Western blotting analysis of mTOR signaling and LC3 in kidney tissues (n = 3). (B) Representative TEM images of autophagic events in renal tubules. The number of autophagosomes and autolysosomes in each cell were quantified (n = 3). Red arrowheads, autophagy; green arrowheads, mitophagy. Scale bars, 2 μm. (C to E) Assessment of the effects of IL-10+ EVs on mitochondrial function in cultured TECs (n = 3). (C) Real-time changes in the OCR of TECs were detected by Seahorse assay. OCR, oxygen consumption rate; BR, basal respiration; MRC, maximal respiratory capacity; N.S., not significant. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of the mitochondrial ROS production in TECs labeled with MitoSOX. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of the mitochondrial membrane potential in TECs labeled with JC-1. (F) Representative TEM images of mitochondria in renal tubules. Scale bars, 1 μm. (G) Immunohistochemical analysis of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (MT-CO1) expression in kidney sections. Scale bars, 100 μm. (H) Mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I enzymatic activity (n = 6). Data are presented as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus IRI group or HR group, one-way ANOVA.

Maintaining mitochondrial fitness by IL-10+ EVs is essential for renal recovery

Autophagy is being recognized as playing an important role against tubular injury and cell death during AKI (22). The renoprotective functions of mitophagy are mostly mediated by the clearance of damaged mitochondria to maintain organelle quality and function (23). Given the observed effects of IL-10+ EVs on mitophagy, we examined whether IL-10+ EVs are capable of maintaining mitochondrial fitness. As shown in Fig. 4 (C to E), IL-10+ EVs exposure resulted in notable reductions in mitochondrial dysfunction after H/R stimulation, as determined by the increase in the oxygen consumption rate (OCR), mitochondrial membrane potential level, and reduction in mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (mitoSOX). Moreover, we also checked the status of renal mitochondrial function in vivo and found that the altered mitochondrial morphology characterized by mitochondrial swelling, brightened matrix, and disorganized fragmented cristae (Fig. 4F), as well as the reduction in cytochrome c oxidase subunit I expression (Fig. 4G) and complex I activity (Fig. 4H), in the TECs of IRI group was ameliorated markedly after IL-10+ EV treatment. When IL-10 signaling was inhibited with the blocking antibody against IL-10 receptor, IL-10+ EVs failed to restore mitochondria function (Fig. 4, C to H) and no longer afforded renoprotection (fig. S6). These findings clarified that IL-10+ EVs protect against tubular injury by inducing mitophagy to maintain mitochondrial fitness.

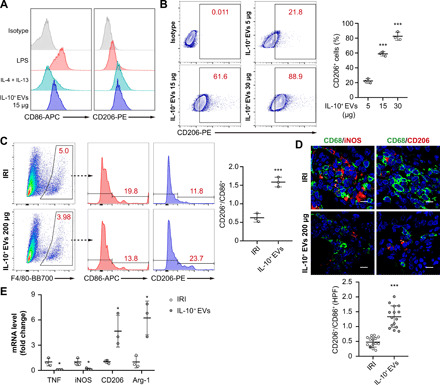

IL-10+ EVs induce a shift in renal macrophages

Macrophages are, in general, the main target cells of IL-10, which has the potential to promote M2 macrophage polarization, thus contributing to the tissue repair (24, 25). Given that considerable numbers of IL-10+ EVs accumulated in the macrophages within renal tissues with I/R injury (Fig. 2E), we postulated that IL-10+ EVs could resolve renal I/R injury through modulating macrophage phenotype. As shown in Fig. 5 (A and B), IL-10+ EVs dose-dependently increased CD206 expression in bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) but failed to induce CD86, indicating a key role for IL-10 from EVs in M2 macrophages induction. Consistent with this idea, IL-10+ EV–treated mice presented a shift in renal macrophage population to the CD206+ M2 phenotype as compared with the IRI group (Fig. 5, C and D). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis of renal macrophages also showed substantial increases in the M2 phenotype after IL-10+ EV treatment, as evidenced by the increased transcriptional levels of M2 markers (CD206 and Arg-1) and decreased levels of M1 markers [TNF and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)] (Fig. 5E). These results demonstrated that IL-10+ EVs efficiently drive M2 macrophage polarization, which can suppress inflammation and promote kidney repair.

Fig. 5. IL-10+ EVs induce a shift in renal macrophages.

(A and B) BMDMs were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml), IL-4 (20 ng/ml) + IL-13 (20 ng/ml), or different doses of IL-10+ EVs (5, 15, and 30 μg) for 48 hours, respectively (n = 3). (A) Expression analysis of CD86 and CD206 by flow cytometry. (B) Dose-dependent effects of IL-10+ EVs on CD206 expression. (C to E) Exploration of the phenotype changes of renal macrophages between IRI group and IL-10+ EV group. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of F4/80+CD86+ or F4/80+CD206+ macrophages in the kidneys (n = 3). (D) Representative confocal images of CD68+CD86+ or CD68+CD206+ macrophages in kidney sections (n = 5). Scale bars, 10 μm. The shift of macrophages was indicated by CD206+/CD86+. (E) real-time quantitative PCR measuring M1-like (TNF and iNOS) and M2-like (CD206 and Arg-1) markers in macrophages isolated from the kidneys (n = 3). Data are presented as means ± SD. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 versus IRI group, one-way ANOVA (B), two-tailed t test (C to E).

IL-10+ EVs attenuate AKI-CKD transition

We next analyzed the effects of IL-10+ EVs on the AKI to CKD transition. To permit long-term survival after AKI, a 35-min warm unilateral IRI approach was adopted (26). As expected, histological analysis of kidney sections at 4 weeks after unilateral IRI revealed significant tubulointerstitial damage, including tubular atrophy, flattening and sloughing of TECs, cast formation, patchy infiltrates of leukocytes, and fibrosis, all of which were markedly ameliorated by IL-10+ EV treatment (Fig. 6, A and B). Additional measures of the features of CKD showed a similar pattern with a reduction of collagen I and α-smooth muscle actin deposition in renal tissues of IL-10+ EV–treated mice (Fig. 6C) and blunted infiltration of macrophages and T cells (Fig. 6D). These data suggested that IL-10+ EVs can interrupt AKI to CKD progression. On the basis of our findings and previous reports (18, 27), we speculate that aiding in tubular repair and restoring mitochondria function are the critical mechanisms responsible for the therapeutic benefits of IL-10+ EVs in this setting.

Fig. 6. IL-10+ EVs attenuate AKI-CKD transition.

A 35-min unilateral IRI was adopted, and IL-10+ EVs (200 μg) were administered intravenously after reperfusion and continued every 24 hours, three times in total. Mice were euthanized at 4 weeks after disease induction. (A) Representative images of PAS staining (n = 6). The bottom was a higher magnification of the boxed region. Scale bars, 500 μm (top) and 200 μm (bottom). (B) Representative images of Masson trichrome staining on sagittal sections (n = 6). The bottom was a higher magnification of the boxed region. Scale bars, 1 mm (top) and 200 μm (bottom). (C) Western blotting analysis of collagen I (Col. I) and α–smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in kidney tissues (n = 4). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (D) Representative confocal images of CD68+CD86+ or CD68+CD206+ macrophages in kidney sections (n = 6). Scale bars, 10 μm. (E) Schematic illustration of the preparation of IL-10+ EVs for the treatment of ischemic AKI. Data are presented as means ± SD. ***P < 0.001 versus IRI group, one-way ANOVA (A to C) and two-tailed t test (D).

Assessment of toxicity and inflammation in IL-10+ EV–treated mice

We next examined IL-10+ EVs toxicity on the major organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, and lung. The histological analysis showed no evidence of in vivo toxicity of IL-10+ EVs (fig. S7A). The concentrations of hepatic enzyme—alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase—in the serum of IL-10+ EV–treated mice showed no obvious differences from those of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–treated mice (fig. S7, B and C). Similarly, inflammatory parameters in the heart, liver, spleen, and lung were not affected by the loaded EVs (fig. S7, D and E), consistent with previous studies that cell-derived EVs are biocompatible and not significantly toxic or immunogenic (9, 10).

To determine the possibility of using primary cells (BMDM) to prepare IL-10+ EVs, we adopted the same manufacturing method to BMDMs and found that IL-10 plasmid transfection and dexamethasone stimulation resulted in a prominent increase of IL-10 in BMDM-derived EVs, which also showed strong capacity to suppress H/R-induced inflammation in TECs (fig. S8). Therefore, the approach of IL-10+ EV manufacturing can be applied to both autologous and primary macrophages.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we reported an approach to manufacture IL-10+ EVs and assessed the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of IL-10+ EVs in the treatment of ischemic AKI. Impressively, delivering IL-10 by EVs enhanced both the stability of IL-10 and its targeting to the injured kidney, resulting in notable renoprotective effects, specifically by promoting mitophagy to maintain mitochondrial fitness in TECs and driving M2 polarization of tubulointerstitial macrophages. Our findings suggest that IL-10+ EVs constitute an effective nanotherapeutic for the treatment of AKI.

IL-10 is a potential therapeutic candidate for multiple diseases; however, its clinical translation is severely hindered by its short half-life and off-target effects (3). Recently, because of their great versatility, low immunogenicity, and favorable safety profile, EVs have attracted considerable attention as drug delivery vehicles for various protein therapeutics, such as IL-4 (28) and IκBα (inhibitor of nuclear factor κBα) (29). Thus, we attempted to develop a EV-based nanotherapeutic to improve the pharmacokinetic properties of IL-10. In our study, IL-10 was efficiently encapsulated into EVs from RAW macrophages that were engineered to overexpress IL-10 following the stimulation of dexamethasone, which was demonstrated to be a feasible, valid, and reproducible approach. Furthermore, we were excited to find that EV-mediated encapsulation protected IL-10 from degradation, consistent with previous reports that the membranous structure of EVs can maintain the stability of cargos in vivo (9, 10). In general, membrane proteins present on EVs determine their specific cell interactions. It has been shown that integrins expressed on macrophage-derived EVs can dictate EV adhesion to the inflamed tissues (12, 16). Notably, a plenty of integrins were identified on IL-10+ EVs, including ITGα4β1, α5β1, αLβ2, and αMβ2, which promoted the homing of IL-10+ EVs toward the injured kidney. In addition to their stability and targeting advantages, EV-mediated delivery altered the cellular distribution of IL-10 in the kidney, affecting both macrophages and renal parenchyma cells, including endothelial cells and TECs. In addition, the glomerular filtration barrier is a serious challenge for the application of EV-based therapy. In the setting of kidney injury, the breakdown of the barrier, especially enlarged endothelial gaps, can aid the accumulation of EVs in kidney cells and components (30, 31). However, the level of EVs is highly restricted depending on the degree of injury. Hence, strategies that promote EVs to pass through the glomerular filtration barrier as much as possible could be highly valuable.

TECs are exquisitely sensitive to ischemic, toxic, or septic insults, and protecting TECs from such insults is the key to promoting renal recovery from AKI (17, 18). IL-10 inhibits ischemia and cisplatin-induced tubular cell apoptosis (4). However, the underlying mechanism still requires clarification. Recent work suggests that IL-10 plays a key role in controlling macrophage metabolism through inhibiting mTORC1, thereby reducing lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–induced glycolysis and promoting oxidative phosphorylation (19). In this study, we found that there was a significant suppression of mTOR signaling in TECs caused by IL-10+ EV treatment, and as a result, mitophagy was activated, which removes damaged mitochondria to maintain organelle quality and function (22). Many studies implicate mitochondrial dysfunction as an initiator of AKI (23, 32), as damaged mitochondria are able to trigger tubular cell apoptosis (33), activate the NLRP3 inflammasome (27, 34), and ultimately induce the loss of kidney function. Thus, improving mitochondrial homeostasis and function has the potential to ameliorate ischemic renal injury, even retard the progression of AKI to CKD (27). Impressively, here, we demonstrated that IL-10+ EVs markedly improved the severe morphological changes and dysfunction in mitochondria caused by I/R injury, as characterized by improved OCR and mitochondrial membrane potential, and decreased ROS production, indicating that IL-10+ EVs could attenuate tubular injury and promote renal recovery by maintaining mitochondrial fitness.

Tissue macrophages are crucial players in renal injury and repair. Traditionally, M2 macrophages are viewed in the literature as anti-inflammatory and reparative. Many studies have shown that macrophages can be manipulated toward an M2 phenotype ex vivo or in vivo for treatment of AKI (24, 25). In general, IL-10 preferentially targets immune cells, such as macrophages, leading to M2 macrophage polarization in murine myocardial infarction (35) and particle-induced osteolysis (36). In our study, a robust number of IL-10+ EVs were localized in macrophages in the tubulointerstitium, which induced a remarkable shift in renal macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype relative to M1. In turn, M2 macrophages help with resolution of inflammation and tubular repair. These data clearly suggested that early treatment with IL-10+ EVs would not only protect tubular cells from injury but also potentially halt the AKI to CKD transition.

Together, we have constructed a platform for targeted delivery of IL-10 by using EVs and highlighted the potential of IL-10+ EVs as a promising nanotherapeutic for ischemic AKI treatment. Our study demonstrated that EV-medicated delivery exhibits unique advantages: (i) improving the pharmacokinetic properties of IL-10, making it more stable, safe, and targetable to injury sites, and (ii) extending the therapeutic targets of IL-10 to include not only immune cells but also renal tubular cells. Mechanistically, we showed that IL-10+ EVs suppress mTOR signaling and consequently promote mitophagy to maintain mitochondrial fitness in TECs. In addition, treatment with IL-10+ EVs polarized macrophages to a M2 phenotype to support renal repair. Our study provides a novel insight and potential for the clinical translation of IL-10+ EVs in the treatment of ischemic AKI.

METHODS

Cell culture

RAW 264.7 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection and cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). BMDMs were harvested from femurs of C57BL/6 mice and differentiated into macrophages using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F12 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and mouse recombined macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (40 ng/ml; 416-ML, R&D System) for 7 days as described previously (37). An immortalized mouse TECs (a gift from J. B. Kopp, National Institutes of Health) were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

Preparation of IL-10+ EVs

(i) Transfection of IL-10 plasmid into the donor RAW cells: To overexpress IL-10 in RAW cells, transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) with CMV-MCS-SV40-Neomycin IL-10 plasmid (GeneChem). Briefly, a total of 5-μg plasmid and 10 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 were mixed with Opti-MEM for the transfection of about 2 × 106 cells. (ii) Stimulation of RAW cells with dexamethasone: After 8 hours of transfection, the medium was replaced with fresh RIPM supplemented with dexamethasone at the dose of 200 nM (Sigma-Aldrich). (iii) Production and isolation of EVs: After 48 hours of stimulation, the supernatants were subsequently subjected to sequential centrifugation steps at 2000g for 20 min and 10,000g for 5 min to get rid of cells and debris. The resulting supernatants were concentrated using 100-kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) (Millipore) at 4000g for 20 min and then were ultracentrifuged at 200,000g for 2 hours. The pellet was washed one time and resuspended in sterile PBS or culture medium for the following experiments.

Characterization of IL-10+ EVs

The size distribution was detected by NTA (ZetaView PMX 110, Particle Metrix). The morphology was examined by TEM (H-7650, Hitachi). Surface markers including EV-associated (Alix, CD63, and CD81) and macrophage-associated proteins (CD68 and CD206) were detected by Western blotting. The concentration of IL-10 in EVs was determined by the mouse IL-10 Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems). The protein concentration of the isolated IL-10+ EVs was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Animal models and therapeutic experiments

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with standard guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male C57BL/6 mice (8 to 10 weeks old, weighing 20 to 22 g) were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich) by intraperitoneal injection, and renal I/R injury was established as previously reported (38). For the bilateral I/R injury, both renal pedicles were clamped by microaneurysm clamps for 35 min. Then, clamps were released, and the kidneys were monitored by a color change to confirm blood reflow before suturing the incision. Sham operations were performed with exposure of both kidneys but without renal pedicle clamping. The body temperature was controlled at 36.6° to 37.2°C by a sensitive rectal probe throughout the procedure. For the unilateral I/R injury, only the left renal pedicle was clamped for 35 min. IL-10+ EVs (100 and 200 μg) or vehicle were administered intravenously after reperfusion and continued every 24 hours for three times. Mice subjected to bilateral I/R injury were euthanized at 3 days after reperfusion, while mice subjected to unilateral I/R injury were euthanized at 4 weeks after reperfusion. For blockade of the IL-10 signaling, a mixture of IL-10+ EVs (200 μg) and anti-IL10R (200 μg; clone: 1B1.3a, BioLegend) was injected intravenously. For cisplatin-induced AKI, mice were administered cisplatin (solution of 1 mg/ml in sterile saline; Sigma-Aldrich) or vehicle (saline) at 20 mg/kg in a single intraperitoneal injection and were euthanized after 4 days. IL-10+ EVs (200 μg) were injected intravenously at day 1 and continued every 24 hours for 3 days.

Kidney histology and quantification

Kidneys were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned to 4-μm thickness. Renal sections were used for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), or Masson’s trichrome staining. To evaluate tubular injury score, 10 random tissue sections per mouse were assessed on H&E or PAS staining and semiquantitatively scored as follows: 0, no damage; 1, <25%; 2, 25 to ~50%; 3, 50 to ~75%; 4, >75%. Results were averaged for each mouse. To evaluate interstitial fibrosis, at least five random tissue sections per mouse were assessed on Masson’s trichrome staining. Tissue fibrosis as defined by blue staining was scored by three experienced observers masked to experiment conditions, and the average values of the fibrosis scores were reported.

Labeling of IL-10+ EVs

To obtain DID-labeled or PKH67-labeled IL-10+ EVs, the donor RAW cells were labeled with DID (Invitrogen) or PKH67 (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s protocol before dexamethasone stimulation, respectively. Then, cells were washed twice with 0.5% FBS/RIPM to remove excess dye. After 48 hours of dexamethasone stimulation, the supernatants were collected and IL-10+ EVs were isolated as described above. In this way, we can remove the free dye in pellet to the greatest extent.

In vivo distribution of IL-10+ EVs

To assess in vivo tissue distribution of IL-10+ EVs, 100-μg DID-labeled IL-10+ EVs were injected intravenously into Sham mice or IRI mice after reperfusion. At 6, 12, 24, 48, and 96 hours after injection, mice were euthanized. Tissues including the liver, heart, lung, spleen, and kidney were excised and imaged using the IVIS Spectrum imaging system (PerkinElmer). In addition, the specific organs were also obtained and mounted in optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound and frozen. Sectioned tissue was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear stain, and images were then captured using a confocal microscope (FV1000, Olympus). Images were quantified by counting the number of nuclei within DID-labeled IL-10+ EVs surrounding it and dividing by the total number of nuclei, in 10 random tissue sections per organ. In kidneys, the specific cellular internalization of IL-10+ EVs was analyzed by immunofluorescent staining of frozen sections with aquaporin 1 (AQP1; ab15080, Abcam), NaCl cotransporter (NCC; ab95302, Abcam), CD31 (ab28364, Abcam), and CD68 (ab955, Abcam).

Cellular uptake of IL-10+ EVs in vitro

PKH67-labeled IL-10+ EVs (15 μg) were incubated with TECs that administered with or without H/R for 6 or 12 hours, respectively. Then, PKH67-positive cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy or flow cytometry. For confocal microscopic analysis, the number of PKH67-labeled IL-10+ EVs in each cell was counted in at least 10 randomly selected fields from each well, and results were averaged for each cell. Immunostaining against TNF (ab1793, Abcam) was used to indicate the cellular inflammation. For flow cytometry analysis, TECs were further stained with CD54–phycoerythrin (PE; 553253, BD Biosciences) and PKH67+CD54+ cells were counted.

Membrane-based antibody array

IL-10+ EVs and M0 EVs were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor (Roche). Total protein (300 μg) of each sample was analyzed by using the Mouse Cytokine Antibody Array (ARY006, R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The arrays were scanned and quantified with ImageJ software. Presented data showed relative protein levels normalized to array reference.

Proteomic analysis

Mass spectrometry analysis of IL-10+ EVs and corresponding donor RAW cells was performed at GeneChem using 200 μg of total protein. Samples extracted with SDS- and dithiothreitol (DTT)–based buffer were precipitated using acetone. After repeated rinsing with acetone, the protein pellets were freeze-dried and denatured using 8 M urea, reduced using 10 mM DTT, and alkylated using 100 mM iodoacetamide. This was followed by digestion with trypsin for 16 hours at 37°C. For the analysis, approximately 10 μg of each sample was analyzed by reversed phase nano–LC-MS/MS (EASY-nLC coupled to Q Exactive Plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, peptides were separated using a 50–μm–inner diameter C18 column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. Precursor mass spectra were recorded in a 350 to 1800 m/z (mass/charge ratio) mass range at 70,000 resolution and 17,500 resolution for fragment ions. Data obtained were analyzed using Proteome Discoverer 2.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) against the UniProt database using the following parameters: maximum number of missed cleavages, 2; precursor tolerance, 20 ppm; dynamic modification, oxidation (M) and N-terminal protein acetylation, deamidated (NQ); static modification, carbamidomethyl (C); and false discovery rate, <0.01.

Flow cytometry analysis of macrophage phenotype

For the detection of macrophage phenotype in kidneys (39), total kidney tissues were minced in a petri dish and digested by 5 ml of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 3% FBS (Gibco), collagenase IV (1 mg/m; Worthington), and deoxyribonuclease (10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). After 60 min of incubation at 37°C, the resulting cell suspension was filtered through 70- and 40-μm cell strainers and washed twice with wash buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS and 2 mM EDTA). The cells were treated with FC Block (553141, BD Biosciences) and then were incubated with F4/80-BB700 (746070, BD Biosciences) and CD86-allophycocyanin (APC) (558703, BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C. Next, cells were washed and fixed with Fix/Perm buffer (BD Biosciences) and were incubated with CD206-PE (141706, BioLegend) for 30 min at 4°C. Flow cytometry was performed on FACSAria II (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed with FlowJo software. For the detection of macrophage phenotype in vitro, BMDMs were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml), IL-4 (20 ng/ml) + IL-13 (20 ng/ml), or different doses of IL-10+ EVs (5, 15, and 30 μg) for 48 hours, respectively. The method for staining BMDMs is as described above. Isotype control antibodies were used as negative controls.

Transmission electron microscopy

Kidneys or collected TEC clusters were immersed in a fixative containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. Sample handling and detection were performed by electron microscopic core lab at Southeast University (H-7650, Hitachi). The autophagosomes and autolysosomes in TECs were quantified for the analysis of autophagy.

Cell treatment

TECs were plated in 35-mm dishes at a density of 1 × 106 cells per dish and incubated until they reached approximately 80 to 90% confluence for experiment. The cells in H/R group were cultured for 12 hours under hypoxic conditions (94% N2 and 5% CO2) in medium without nutrients (glucose-free, FBS-free). In addition, cells were then transferred back to regular culture medium with oxygen for 2 hours of reoxygenation. Control cells were incubated in complete culture medium in a regular incubator (5% CO2 and 95% air). For the IL-10+ EV treatment, cells were incubated with IL-10+ EVs (5 and 15 μg) or together with anti-IL10R (10 μg/ml; clone: 1B1.3a, BioLegend) for 12 hours during hypoxia.

Measurement of mitochondrial function

Oxygen consumption rate

Analysis of OCR was performed using the Seahorse XF96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience) as described previously (40). Briefly, TECs were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well on Seahorse plate and stimulated as described above. Before starting the assay, cells were washed and incubated in Seahorse assay medium in 37°C incubator without CO2 for 1 hours before assessing basal OCR. After calibration, basal OCR was recorded for 20 min, and OCR measurements were performed over time upon addition of mitochondrial inhibitors: (i) Oligomycin (adenosine triphosphatase inhibitor, 1 μM) was used to determine ATP-synthesis coupling efficiency. (ii) Carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (0.5 μM) was used to calculate the maximal respiratory capacity. (iii) Last, a mixture of rotenone (0.5 μM) and antimycin A (0.5 μM) were used to assess the nonmitochondrial consumption of O2.

Mitochondrial ROS

Mitochondrial ROS production in TECs was measured using MitoSOX (M36008, Invitrogen). Briefly, about 2 × 106 cells were harvested and incubated with 10 μM MitoSOX at 37°C for 20 min. The mean fluorescence intensity was detected by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences).

Mitochondrial membrane potential

Mitochondrial membrane potential in TECs was determined using JC-1 (5,5’,6,6’-tetrachloro-1,1’,3,3’-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide) (551302, BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Fluorescence quantitation was examined with flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences), and the relative mitochondrial membrane potential was calculated using the ratio of red/green (590/520 nm).

Mitochondrial complex I activity

Mitochondria from kidney cortex were isolated using a commercial kit (ab110168, Abcam) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Mitochondrial OXPHOS complex I enzyme activity was measured by the Complex I Enzyme Activity Microplate Assay Kit (Colorimetric) (ab109721, Abcam). Briefly, isolated mitochondrial samples were loaded to the wells of the microplate at a final protein concentration of 5.5 mg/ml and were incubated at room temperature for 3 hours. Then, 200 ml of assay solution was added to each well. Optical density at 450 nm was measured in a kinetic mode at room temperature for 40 min.

Apoptosis analysis

Apoptosis was tested with TUNEL (Roche) in mouse kidney sections and through annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate and propidium iodide staining (BD Biosciences) in cultured TECs.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining

For immunohistochemistry staining, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies against MTCO1 (ab14705, Abcam), CD68 (ab955, Abcam), or CD3 (ab16669, Abcam) and then analyzed using streptavidin peroxidase detection system (Maixin) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Maixin) was used as a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–specific substrate. For immunofluorescence staining, formaldehyde-fixed cells or kidney sections were performed with primary antibodies against RFP (ab62341, Abcam), CD63 (sc5275, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), IL-10 (ab9969, Abcam), KIM-1 (MA5-28211, Invitrogen), CD68 (ab955, Abcam), iNOS (ab15323, Abcam), CD206 (ab64693, Abcam), and CD3 (ab16669, Abcam), followed by incubation with secondary antibodies. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Immunostained samples were visualized under a confocal microscope (FV1000, Olympus).

Quantitative real-time PCR assay

The total RNA from cells or kidney cortex was extracted using the TRIzol (Takara), and complementary DNA was then synthesized using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara). PRT-qPCR was performed using a 7300 real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). All the primer sequences were listed in table S1.

Western blotting

The protein lysates from the IL-10+ EVs, cells, or kidney tissues were prepared following standard protocols, and the protein content was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Then, the proteins samples were separated by Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore) using a wet-transfer system. Membranes were blocked in 5% BSA in TBS-T (tris buffered saline –Tween 20) for 1 hour at room temperature and were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Then, membranes were washed and incubated with secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature, and the signals were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence advanced system (GE Healthcare). Intensity values expressed as the relative protein expression were normalized to β-actin. Primary antibodies used were anti-Alix (sc-53540, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-CD63 (sc5275, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-CD81 (10037, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-CD68 (ab955, Abcam), anti-CD206 (ab64693, Abcam), anti–IL-10 (ab9969, Abcam), anti–IL-10R (ab225820, Abcam), anti–integrin α4 (8440, Cell Signaling Technology), anti–integrin α5 (98204, Cell Signaling Technology), anti–integrin αL (ab186873, Abcam), anti–integrin αM (ab133357, Abcam), anti–integrin β1 (4706, Cell Signaling Technology), anti–integrin β2 (ab185723, Abcam), anti–caspase-3 (ab13847, Abcam), anti–p-p70 S6K (9234, Cell Signaling Technology), anti–p-S6 (4857, Cell Signaling Technology), anti–p-4E-BP1 (2855, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-S6 (2317, Cell Signaling Technology), anti–collagen I (ab34710, Abcam), and anti–α smooth muscle actin (ab5694, Abcam). Secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies used were anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) and anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the means ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge C.C. Zhang for the assistance with the electron microscopic sample handling and detection and Y. L. An for the assistance with tissue imaging. Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 81720108007, 81670696, 81470922, and 31671194), the National Key Research and Development Program (2018YFC1314000), the Clinic Research Center of Jiangsu Province (no. BL2014080), the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (no. 2012CB517706), and the Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (no. KYCX18_0171). Author contributions: T.-T.T., L.-L.L., and B.-C.L. designed the experiments, performed the data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. T.-T.T., B.W., Y.F., and Z.-L.L. carried out the animal experiments. T.-T.T., B.W., J.-Y.C., D.Y., and M.W. were responsible for the in vitro study. H.L. and R.-N.T. provided the pathology analysis. S.D.C. advised on the experimental design and assisted with manuscript writing. Competing interests: B.-C.L. and T.-T.T. are inventors on (202010134391.1, the patent is in the Preliminary Examination Procedure) related to this work filed by State Intellectual Property Office of P.R. China (28 February 2020). The authors declare that they have no other competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/33/eaaz0748/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Ronco C., Bellomo R., Kellum J. A., Acute kidney injury. Lancet 394, 1949–1964 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chawla L. S., Eggers P. W., Star R. A., Kimmel P. L., Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 58–66 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouyang W., O'Garra A., IL-10 Family Cytokines IL-10 and IL-22: From Basic Science to Clinical Translation. Immunity 50, 871–891 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng J., Kohda Y., Chiao H., Wang Y., Hu X., Hewitt S. M., Miyaji T., McLeroy P., Nibhanupudy B., Li S., Star R. A., Interleukin-10 inhibits ischemic and cisplatin-induced acute renal injury. Kidney Int. 60, 2118–2128 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin Y., Liu R., Xie J., Xiong H., He J. C., Chen N., Interleukin-10 deficiency aggravates kidney inflammation and fibrosis in the unilateral ureteral obstruction mouse model. Lab. Invest. 93, 801–811 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipiäinen T., Peltoniemi M., Sarkhel S., Yrjönen T., Vuorela H., Urtti A., Juppo A., Formulation and stability of cytokine therapeutics. J. Pharm. Sci. 104, 307–326 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karpman D., Ståhl A. L., Arvidsson I., Extracellular vesicles in renal disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 13, 545–562 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W., Zhou X., Zhang H., Yao Q., Liu Y., Dong Z., Extracellular vesicles in diagnosis and therapy of kidney diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 311, F844–F851 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiklander O. P. B., Brennan M. Á., Lötvall J., Breakefield X. O., El Andaloussi S., Advances in therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaav8521 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang T.-T., Lv L.-L., Lan H.-Y., Liu B.-C., Extracellular Vesicles: Opportunities and Challenges for the Treatment of Renal Diseases. Front. Physiol. 10, 226 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao X., Ran N., Dong X., Zuo B., Yang R., Zhou Q., Moulton H. M., Seow Y., Yin H., Anchor peptide captures, targets, and loads exosomes of diverse origins for diagnostics and therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaat0195 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang T.-T., Lv L.-L., Wang B., Cao J.-Y., Feng Y., Li Z.-L., Wu M., Wang F.-M., Wen Y., Zhou L.-T., Ni H.-F., Chen P.-S., Gu N., Crowley S. D., Liu B.-C., Employing macrophage-derived microvesicle for kidney-targeted delivery of dexamethasone: An efficient therapeutic strategy against renal inflammation and fibrosis. Theranostics 9, 4740–4755 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anders H.-J., Ryu M., Renal microenvironments and macrophage phenotypes determine progression or resolution of renal inflammation and fibrosis. Kidney Int. 80, 915–925 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agrahari V., Agrahari V., Burnouf P. A., Chew C. H., Burnouf T., Extracellular Microvesicles as New Industrial Therapeutic Frontiers. Trends Biotechnol. 37, 707–729 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He C., Zheng S., Luo Y., Wang B., Exosome Theranostics: Biology and Translational Medicine. Theranostics 8, 237–255 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan D., Zhao Y., Banks W. A., Bullock K. M., Haney M., Batrakova E., Kabanov A. V., Macrophage exosomes as natural nanocarriers for protein delivery to inflamed brain. Biomaterials 142, 1–12 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonventre J. V., Yang L., Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4210–4221 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu B.-C., Tang T.-T., Lv L.-L., Lan H.-Y., Renal tubule injury: A driving force toward chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 93, 568–579 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ip W. K. E., Hoshi N., Shouval D. S., Snapper S., Medzhitov R., Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 mediated by metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science 356, 513–519 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxton R. A., Sabatini D. M., mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 169, 361–371 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolman N. J., Chambers K. M., Mandavilli B., Batchelor R. H., Janes M. S., Tools and techniques to measure mitophagy using fluorescence microscopy. Autophagy 9, 1653–1662 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang M., Wei Q., Dong G., Komatsu M., Su Y., Dong Z., Autophagy in proximal tubules protects against acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 82, 1271–1283 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhargava P., Schnellmann R. G., Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 13, 629–646 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricardo S. D., van Goor H., Eddy A. A., Macrophage diversity in renal injury and repair. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3522–3530 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen T., Cao Q., Wang Y., Harris D. C. H., M2 macrophages in kidney disease: Biology, therapies, and perspectives. Kidney Int. 95, 760–773 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu Y., Tang C., Cai J., Chen G., Zhang D., Dong Z., Rodent models of AKI-CKD transition. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 315, F1098–F1106 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szeto H. H., Liu S., Soong Y., Seshan S. V., Cohen-Gould L., Manichev V., Feldman L. C., Gustafsson T., Mitochondria Protection after Acute Ischemia Prevents Prolonged Upregulation of IL-1β and IL-18 and Arrests CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 1437–1449 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casella G., Colombo F., Finardi A., Descamps H., Ill-Raga G., Spinelli A., Podini P., Bastoni M., Martino G., Muzio L., Furlan R., Extracellular Vesicles Containing IL-4 Modulate Neuroinflammation in a Mouse Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Mol. Ther. 26, 2107–2118 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi H., Kim Y., Mirzaaghasi A., Heo J., Kim Y. N., Shin J. H., Kim S., Kim N. H., Cho E. S., In Yook J., Yoo T. H., Song E., Kim P., Shin E. C., Chung K., Choi K., Choi C., Exosome-based delivery of super-repressor IκBα relieves sepsis-associated organ damage and mortality. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz6980 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ståhl A.-L., Arvidsson I., Johansson K. E., Chromek M., Rebetz J., Loos S., Kristoffersson A. C., Békássy Z. D., Mörgelin M., Karpman D., A novel mechanism of bacterial toxin transfer within host blood cell-derived microvesicles. PLOS Pathog. 11, e1004619 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamaly N., He J. C., Ausiello D. A., Farokhzad O. C., Nanomedicines for renal disease: Current status and future applications. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 12, 738–753 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishimoto Y., Inagi R., Mitochondria: A therapeutic target in acute kidney injury. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 31, 1062–1069 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho S.-G., Du Q., Huang S., Dong Z., Drp1 dephosphorylation in ATP depletion-induced mitochondrial injury and tubular cell apoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 299, F199–F206 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu D., Xu M., Ding L. H., Lv L. L., Liu H., Ma K. L., Zhang A. H., Crowley S. D., Liu B. C., Activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: A novel mechanism of albumin-induced tubulointerstitial inflammation. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 57, 7–19 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung M., Ma Y., Iyer R. P., DeLeon-Pennell K. Y., Yabluchanskiy A., Garrett M. R., Lindsey M. L., IL-10 improves cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction by stimulating M2 macrophage polarization and fibroblast activation. Basic Res. Cardiol. 112, 33 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang J., Jia T., Gong W., Ning B., Wooley P. H., Yang S.-Y., Macrophage Polarization in IL-10 Treatment of Particle-Induced Inflammation and Osteolysis. Am. J. Pathol. 186, 57–66 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lv L.-L., Feng Y., Wu M., Wang B., Li Z. L., Zhong X., Wu W. J., Chen J., Ni H. F., Tang T. T., Tang R. N., Lan H.-Y., Liu B.-C., Exosomal miRNA-19b-3p of tubular epithelial cells promotes M1 macrophage activation in kidney injury. Cell Death Differ. 27, 210–226 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang T. T., Lv L. L., Pan M. M., Wen Y., Wang B., Li Z. L., Wu M., Wang F. M., Crowley S. D., Liu B. C., Hydroxychloroquine attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting cathepsin mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Death Dis. 9, 351 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudemiller N. P., Crowley S. D., Characterization and Functional Phenotyping of Renal Immune Cells via Flow Cytometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 1614, 87–98 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo Y., Ni J., Chen S., Bai M., Lin J., Ding G., Zhang Y., Sun P., Jia Z., Huang S., Yang L., Zhang A., MicroRNA-709 Mediates Acute Tubular Injury through Effects on Mitochondrial Function. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 29, 449–461 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/33/eaaz0748/DC1