Abstract

Background

Good clinical practice (GCP) training is the industry expectation for ensuring quality conduct of registrational clinical trials. However, concerns exist about whether the current structure and delivery of GCP training sufficiently prepares clinical investigators and their delegates to conduct clinical trials.

Methods

We conducted qualitative semi-structured interviews with 13 clinical investigators and 10 research sponsors to 1) examine characteristics of the quality conduct of sponsored clinical trials, including critical tasks and concerns perceived as essential for trial quality, 2) identify key knowledge and skills required to perform critical tasks, and 3) identify gaps and redundancies in GCP training and areas of improvement to ensure quality conduct of clinical trials. Data were examined using applied thematic analysis.

Results

The top three tasks identified as critical for the quality conduct of clinical trials were obtaining informed consent, ensuring protocol compliance, and protecting participants’ health and safety. Respondents acknowledged that GCP principles address each of these critical tasks but also described many challenges and burdens of GCP training, including high training frequency and repetitive content. Respondents suggested moving beyond GCP training as a mere check-box activity by making it more effective, engaging, and interactive. They also emphasized that applying GCP principles in a real-world, skills-based environment would increase the perceived relevance of GCP training.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that although investigators and sponsors recognize that GCP training addresses tasks critical to the quality conduct of clinical trials, the need for significant improvement in the design, content, and presentation of GCP training remains.

Keywords: Good clinical practice, Clinical trials, Quality, Investigator training, Clinical investigator

1. Introduction

Regulations put forth by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [21 CFR 312.50, 21 CFR 312.53(a), 21 CFR 812.40 and 21 CFR 812.43(a)] require that sponsors of registrational clinical trials select qualified investigators to conduct these trials. Good clinical practice (GCP) describes the scientific and ethical considerations involved in the quality conduct of clinical trials, as well as specifying investigator qualifications, roles, and responsibilities. Although not required by FDA regulations, clinical trial sponsors typically mandate training on GCP principles for investigators and their delegates prior to participation in each clinical trial and often consider such training as one of the metrics for demonstrating that investigators are qualified to conduct clinical trials.

Concerns have been raised over the current structure and delivery of GCP training to prepare clinical investigators and their delegates to conduct registrational clinical trials [1,2]. GCP training has been described as time-consuming [3], emphasizing trial activities unrelated to research validity [4] and providing only the minimum of what is needed in the quality conduct of clinical trials [1]; redundant [1]; lacking specificity about the definition of site quality or clinical investigators’ perspectives on site quality [5]; and having monitoring standards that vary widely across research studies and sites [6,7]. Despite being the industry expectation, there is little evidence that completion of GCP training alone sufficiently qualifies investigators and their delegates in the quality conduct of clinical trials [1].

The Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI, www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org)—a public-private partnership to develop and drive adoption of practices that will increase the quality and efficiency of clinical trials—conducted a two-phased project to gain a broader, evidence-based perspective on the efficient and effective qualification of site investigators and their delegates for the quality conduct of clinical trials. The first phase consisted of a literature review [8], expert interviews, and a survey to assess current GCP training, culminating in recommendations for streamlining GCP training practices [1,9]. These recommendations focused on four components of training: minimum essential elements, training frequency, training format, and evidence of completion [1,9].

As part of the second phase, CTTI conducted interviews to gather the views and experiences of representatives who initiate and provide funding for biopharmaceutical clinical trials (i.e., clinical trial sponsors) and clinical investigators to 1) examine characteristics of the quality conduct of sponsored clinical trials, including critical tasks and concerns perceived as essential for trial quality, 2) identify key knowledge and skills required to perform critical tasks, and 3) identify gaps and redundancies in GCP training and areas of improvement to ensure the quality conduct of clinical trials.

This paper reports on a subset of these objectives. First we present the top three most frequently mentioned critical tasks for ensuring the quality conduct of clinical trials, including respondents' identification of the GCP principles that adequately address those tasks. This is followed by respondents' suggested changes to GCP training on the top three critical tasks. Next, we provide an overview of respondents' views on the burden and redundancies of GCP training. Finally, we present respondents’ suggestions for reconfiguring GCP training to better meet the needs of clinical trial investigators and sponsors.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

We conducted a qualitative descriptive study [10,11] using semi-structured interviews (SSIs) with clinical trial investigators and clinical trial sponsors.

2.2. Participant eligibility and selection

Clinical investigators were eligible to participate if they 1) are currently involved in a phase 3 clinical trial of drugs, biologics, and/or medical devices for registrational purposes; and 2) have participated in at least three phase 3 registrational trials within the past 5 years, for which GCP training was required for each trial. Research sponsors were eligible to participate if they required GCP training for investigators and their delegates for their trials.

The CTTI Team for this project—which consisted of FDA representatives, industry representatives (pharmaceutical, biotech, device, and clinical research organizations), and members of patient advocacy groups, professional societies, investigator groups, and academic institutions—identified numerous investigators and sponsors from among their professional networks whom they believed would be eligible. Using this list, the project manager together with the CTTI social science team purposefully selected [12] investigators to provide representation from a variety of research sites—academic, community-based health centers, and dedicated research sites—as well as those affiliated with research networks. Sponsors were purposefully selected on the basis of company size to ensure representation across small and large companies.

2.3. Data collection

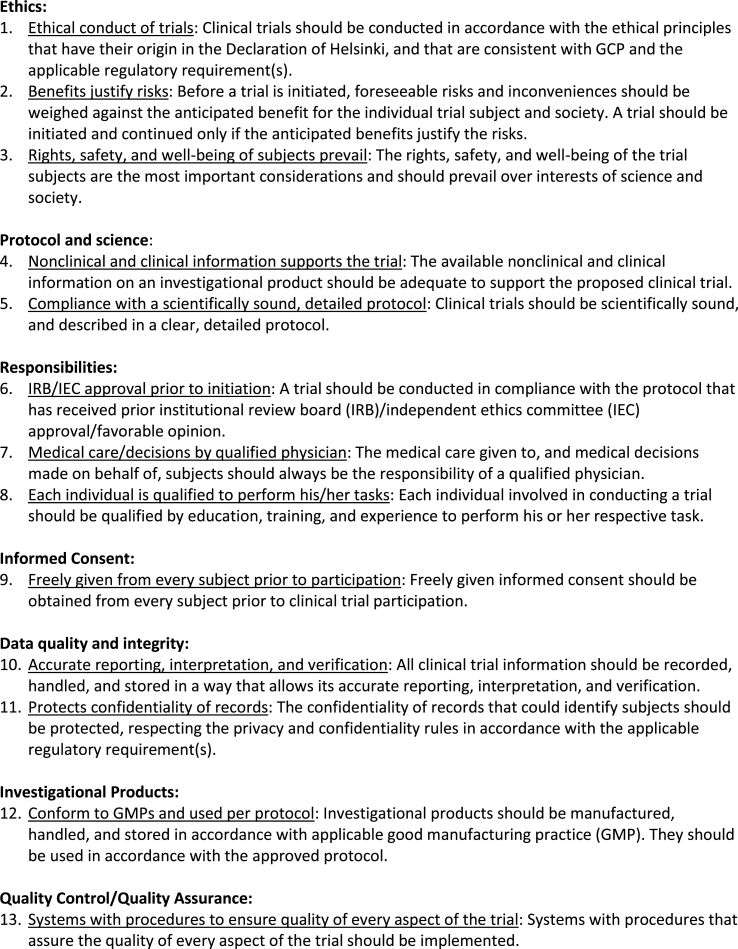

We contracted with RTI International, an independent nonprofit research institute, to conduct telephone interviews with clinical investigators and research sponsors between May 12 and August 4, 2017. Respondents were asked to share their thoughts on all of the critical tasks that must be conducted at sites to ensure the quality conduct of clinical trials; the three tasks they perceived as the most critical; the GCP principles that adequately address these top three critical tasks (participants were provided with the list in Fig. 1); the topics they believe are missing from GCP training for each of the top three critical tasks; and redundancies in clinical trial training, including GCP training. Participants also responded to questions about the types of changes they felt need to be made to GCP training to ensure the quality conduct of clinical trials. All interviews were digitally audio recorded with the participant's permission. We also collected demographic information from each respondent.

Figure 1.

2.4. Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the demographic data. All interviews were transcribed verbatim following a transcription protocol [15]. Applied thematic analysis [16] was used to analyze respondents’ narratives, using a two-stage deductive and inductive analysis approach. First, three analysts applied structural codes (based on the specific interview topics and organized according to the research objectives) using NVivo 11, a qualitative data analysis software program (QSR International Pty Ltd 2015). Inter-coder agreement was assessed on four interviews (17% of the transcripts, two investigator and two research sponsors). Discrepancies in code application were resolved through group discussion, and edits were subsequently made to the codebook. Analysts then inductively identified content-driven codes in each structural coding report and applied these content codes to the data using NVivo 11. The content-driven coding reports were reviewed to identify themes and sub-themes related to the objectives based on their frequency. Data summary reports were produced describing these themes and sub-themes, together with illustrative quotes.

2.5. Ethics

The Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board (IRB) and an IRB within the Office of Research Protection at RTI International reviewed the study protocol and determined that the research is exempt from IRB review.

3. Results

3.1. Study population

We interviewed 13 clinical investigators and 10 research sponsors. Clinical investigators represented various specialties and organizations, and had 10–35 years of experience in their field of medicine, which ranged from highly specialized clinical practice (e.g., oncology and hematology) to more general practice (e.g., general internal medicine and family medicine). Investigators were affiliated with a variety of types of research sites and most (62%) stated that their site belonged to a research network. The number of years leading phase 3 clinical trials of drugs, biologics, and/or medical devices for registrational purposes as the principal investigator (PI), co-PI, and sub-PI varied greatly among investigators (range 1–31 years), as did the number of trials the investigators had led (3–300) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Investigator demographics.

| Investigator Demographics (n = 13) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Organization of Current Affiliation | |

| Academic institution or academic health system with research and education opportunities | 4 (30.8) |

| Community-based out-patient clinic or private practice with primary clinical responsibilities | 2 (15.4) |

| Community-based hospital with no affiliated academic institution | 1 (7.7) |

| Dedicated research site with no affiliated clinical practice responsibility | 5 (38.5) |

| Othera |

1 (7.7) |

| Specialty | |

| Cardiology | 3 (23.1) |

| General Internal Medicine | 3 (23.1) |

| Pulmonary and Critical Care | 2 (15.4) |

| Primary Care | 1 (7.7) |

| Pediatrics | 1 (7.7) |

| Psychiatry | 1 (7.7) |

| Family Medicine | 1 (7.7) |

| Oncology and Hematology |

1 (7.7) |

| Years in Specialty | |

| 10–19 years | 3 (23.1) |

| 20–29 years | 3 (23.1) |

| 30–35 years |

7 (53.8) |

| Years as PI/co-PI/sub-I of Registrational Trials | |

| 1–10 years | 4 (30.8) |

| 11–20 years | 5 (38.5) |

| 21–30 years | 3 (23.1) |

| >30 years |

1 (7.7) |

| Number of Registrational Trials Conducted | |

| 3–20 trials | 3 (23.1) |

| 21–40 trials | 2 (15.4) |

| 41–60 trials | 2 (15.4) |

| 81–100 trials | 3 (23.1) |

| >100 trials |

3 (23.1) |

| Type(s) of Products Investigated in Registrational Trialsb | |

| Drugs, either therapeutic or preventive | 13 (100) |

| Biologics | 8 (61.5) |

| Vaccines | 7 (53.8) |

| Devices | 7 (53.8) |

| Combination Products | 6 (46.2) |

| Otherc |

2 (15.4) |

| Investigator’s Site Belongs to a Research Network | |

| Yes | 8 (61.5%) |

| No | 5 (38.5%) |

Hospital system.

Investigators selected all that apply.

Diagnostics, Sampling Studies/Sample Banking.

Research sponsors represented pharmaceutical or medical device companies of various sizes and types of products. Sponsor representatives’ roles varied and included vice presidents, senior or executive-level directors, departmental directors or heads, and managers; years of experience in these roles ranged from 1 to 23 years. All sponsor representatives had partnered with academic institutions to conduct some of their registrational trials; most had partnered with community-based outpatient clinics and hospitals (n = 9 and n = 7, respectively), and half had partnered with dedicated research sites (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sponsor demographics.

| Sponsor Demographics (n = 10) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Type(s) of Products Company Developsa | |

| Drugs, either therapeutic or preventive | 5 (50) |

| Vaccines | 1 (10) |

| Devices | 4 (40) |

| Biologics | 4 (40) |

| Combination products |

6 (60) |

| Size of Company | |

| A micro-size company (market cap under $300 million) | 0 (0) |

| A small-size company (market cap at $300 million to under $2 billion) | 2 (20) |

| A mid-size company (market cap between $2 billion and $10 billion) | 4 (40) |

| A large-size company (market cap over $10 billion) | 3 (30) |

| Prefer not to respond |

1 (10) |

| Years Sponsor Engaged in Registrational Phase III Clinical Trials | |

| 3–5 years | 1 (10) |

| 6–10 years | 0 (0) |

| 11–15 years | 3 (30) |

| 16–20 years | 3 (30) |

| 21–25 years |

3 (30) |

| Therapeutic Areas of Registrational Phase III Clinical Trialsb | |

| Cardiology | 5 (50) |

| Immunology | 2 (20) |

| Gastroenterology | 1 (10) |

| Hematology | 1 (10) |

| Infectious disease | 1 (10) |

| Neurology | 1 (10) |

| Oncology | 1 (10) |

| Ophthalmology | 1 (10) |

| Rheumatology | 1 (10) |

| Otherc | 8 (80) |

Sponsors selected all that apply.

Sponsors selected all that apply.

Pain, Neuromodulation, Surgical Products, Critical Care, Peripheral Artery Disease, Inflammation, Rare Disease, Anesthesiology, Endourology, Targeted Temp. Management, Home Care, Structural Heart.

3.2. Top three critical tasks and associated GCP principles

Fig. 1 in the eAppendix displays all critical tasks described by respondents. Table 1 in the eAppendix displays the top three critical tasks, their associated GCP principles as linked by participants, and representative quotes. The most frequently mentioned top three critical tasks were 1) obtaining informed consent, 2) ensuring protocol compliance, and 3) protecting participants’ health and safety. Most respondents cited more than one GCP principle as adequately addressing each of the top three critical tasks, and there was overlap between the principles cited for each task.

3.3. Informed consent

Informed consent was the most frequently identified critical task listed in respondents’ “top three.” Respondents stressed that informed consent was the foundation for clinical research. They also emphasized the importance of informed consent as a process for ensuring that potential participants are fully informed and understand all the risks and benefits of study participation and what they are being asked to do, so they can make a truly informed decision. Respondents linked the critical task of “informed consent” to the GCP domains of ethics, informed consent, and responsibilities.

3.4. Protocol compliance

The second top critical task identified was protocol compliance. Respondents described protocol compliance—especially to inclusion/exclusion criteria, proper screening, and enrollment—as critically important because it impacts the integrity of the data and ultimately the study's findings about whether or not the investigational product was beneficial. Protocol compliance also ensures study participants' safety. Respondents linked the critical task of “protocol compliance” to the GCP domains of responsibilities, protocol and science, and data quality and integrity.

3.5. Protecting participants’ health and safety

The third top critical task described by respondents was participant safety. Respondents stressed the importance of protecting study participants above all else. The critical task of “protecting participants’ health and safety” was linked to the GCP domains of responsibilities and ethics.

3.6. Suggested changes to GCP training on the top three critical tasks

Table 3 lists suggested changes to GCP training for the top three critical tasks, based on respondents’ views on content that is missing from GCP training. Suggested changes generally focused on adding to existing definitions, guidance, and training.

Table 3.

Suggested changes to GCP training for top three critical tasks.

| Top Three Critical Tasks | Type of Modification Needed |

|---|---|

| Informed Consent |

|

| Protocol Compliance |

|

| Protecting Participants' Health and Safety |

|

3.7. Burden and redundancies in GCP training

Investigators described several training components they felt were redundant and did not improve investigators’ ability to conduct critical tasks. The general review of the rationale for GCP was one of the most commonly cited complaints, with investigators particularly seeming to dislike having to repeatedly review historical background (e.g., the Belmont Report, the Tuskegee Experiment). Sponsors displayed an awareness of investigator frustration with the frequent repetition of general review of GCP and in many instances reported that their trainers had a tendency to gloss over GCP basics as a result.

Moreover, the most common challenge respondents cited about GCP training in general, prior to any specific questions on training redundancies, centered on frequent GCP trainings and its repetitive content. The majority of investigators felt that requirements to re-certify GCP training within a certain time frame or to re-certify for every trial were onerous, particularly given that the content of such training is often the same. An investigator stated that the requirement to participate in repetitious and redundant GCP training was a deterrent to physician participation in clinical trials.

We have actually had physicians in our practice who don't participate in clinical trials because of the requirement to re-certify frequently in things that they already know that takes several hours of time on the weekend. Asking people to re-do these things every three years for 4–6 h on a day off is a problem. It has impaired my ability to get half of the people in my practice to participate as sub-I's in clinical trials. They see it as a waste of time, and they see being asked to do the same things over and over again as insulting.

Other training topics investigators noted that tend to be repetitive included adverse events, data quality/integrity, forms/processes/labs, and informed consent. Sponsors noted that routine training on these topics tended to be “canned,” take a lot of time, and not necessarily be tailored to the protocol.

A few investigators and sponsors, however, viewed redundancy as a positive feature of GCP training. They explained that repetition of GCP material helped to reinforce key concepts and could be beneficial for some investigators and study staff to hear again, which may ultimately be beneficial for protecting patients.

A sponsor said:

Sometimes there's good in being redundant, particularly when we talk about protecting patients. I think when there is redundancy, it is appropriate. I wouldn't say that there's something on here that doesn't prepare physicians for conducting clinical studies. At least I don't think so.

Additionally, some sponsors noted that investigator inattention to GCP content does not necessarily translate to proficiency with GCP basics, despite frequent repetition:

… this is kind of a gut thing for me, both when you see the body language on sites when we start talking about GCP, it's like “I already know.” So, then we won't have any protocol deviations, we won't have any eligibility violations, there won't be any issues with reporting, right? Invariably there are. … I think there's a fine balance on all of it. I see physicians looking at their watch when I tell them how to deploy a stent. “I just did 30 of these this week so I don't need any help on that.” … I would tend to think some of the things we talk about in GCP, people act like, “I've been doing this for 20 years, I don't need to be told again.” That's probably the first thing that comes up, which is unfortunate, because that's what our whole conversation is about.

Investigators also described other burdens that they had experienced with GCP training. They noted that GCP training was time-consuming and had the potential to be perceived as just another box to check off and something to get through as quickly as possible, rather than as an important consideration for patient safety. An investigator explained:

It's often perceived as something just to get through. And you know what you're supposed to do, and you're kind of given this forced video feed to watch and answer a few questions to make sure you've gotten it, and if you don't get the questions right you just re-take the test.

Investigators further described GCP training as uninteresting, both as a result of the content covered and the format and style in which the training is delivered. Lack of centralized and standardized GCP training that is accepted by all sponsors is also perceived as a burden by some investigators because sponsors generally require investigators and their delegates to complete GCP training for each clinical trial.

3.8. Feedback on improvements to GCP training in general and suggested solutions

Respondents suggested changes to current GCP training to ensure the quality conduct of clinical trials, beyond the top three critical tasks. Investigators and sponsors focused on slightly different issues. Investigators touched on the frequency, standardization, methods, and content of GCP training, with some investigators commenting on only one of these areas, and others proposing changes to multiple aspects of training. Overall, investigator comments tended to focus both on strategies for alleviating training burden and for reviving interest in the training topics. Sponsors primarily focused on strategies for capturing trainees' interest and ensuring attention to the material. Investigators' and sponsors’ feedback are presented separately in Table 4.

Table 4.

Feedback on improvements to GCP training in general and suggested solutions by respondent type.

| Topic | Investigators |

Sponsors |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change Suggested | Representative Quotes | Change Suggested | Representative Quotes | |

| Training Frequency |

|

So, you say how do we improve GCP training? You know what, I want less GCP training. It's gotten so burdensome. I'm just one person, and if you have 40 staff at a site, so you have all that redundancy with 40 people, each one on 5 trials, except for me, I'm on all of them. It's stupid, really, how bad it is. So, I don't think there's any more need. I think they need to do less. I would like to see a centralized GCP training for whoever, whether it's investigators or whoever is participating in the clinical trial, I'd like to see something more centralized so we're not having to do all of these sponsor specific trainings. So, if I do CITI training, or whatever the recognized GCP training is, if that's done on-, and quite frankly, I don't think it would hurt to have it on an annual basis, rather than every two years. |

NA | NA |

| Training Standardization |

|

Well, I think there's, from what I understand, a national curriculum. … Almost like if a physician has a medical specialty, and they have to be re-certified every number of years. I would think that GCP might be that way, as opposed to allowing you to do it on the computer whenever you want, and you go through it and don't look at. You don't pay as much attention. … I think it provides a level of confidence for the public and for subjects. And it should for society for government, for whoever. But, it will also provide the recognition that you remain knowledgeable about the area. |

|

… if we could reach some kind of, “Hey, this is a standard that we're all going to follow,” I think that would be helpful, so that investigators who participate in a lot of research by a lot of different sponsors aren't undergoing the same GCP training multiple times. … I know we've tried that at CTTI and made recommendations, and it's just not quite there yet. |

| Training Conduct and Methods |

|

… in this day and age with so many inputs in our lives with the EMR, email, etcetera, the expectation is we need that information at the time you're using it. And I think that's where a little bit of the training, the missed opportunity, is figuring out, how do you provide the right information at the right time to the right person. … it's almost like how we initiated procedures in the clinical practice to reduce mistakes.…just to pause as part of the culture at the time you are doing that component of the protocol. … I think that's where if people had the mindset, “I'm about to consent this patient. There are things I need to remember about the consent process. It's making the appropriate explanation of the study, what randomization is, what your risks are, your cost, signing the forms on each page so that there's recognition that there's been a review, and appropriate signatures on the back page. OK, before I do this, I reminded myself what's required, and now I'm going to execute this procedure.” |

|

The question is how well are they presented and you get the point across, or are they just a “check the box discussion” that has to occur. I think GCP is the hardest part of site training often, because either the monitor or the trainer glosses over it, or the physician has convinced him or herself that they are experts on it, and so they don't pay attention to it. So, it's not so much redundant as its how to engage them in the dialog to make sure that you're pressure testing their understanding of it, and they are really engaged in their understanding beyond what they may have done in the past. … as a sponsor it's our responsibility to provide training, but when we provided these additional trainings, it's been really helpful to bring in our steering committee members to provide, like, case studies, because a lot of our steering committee members are leaders in the field. So, there is more incentive for the PIs to attend these trainings. Or research coordinators will think it's more valued to have a leader in the field speaking with them and providing information that's more valuable to them and to take time out of their day. … But, you know those real world examples, having someone presenting live in the teleconference that is the key opinion leader in the field as part of the presentation, and taking questions from the research coordinators and the PIs, I think you get better attendance, I think you get better interaction, and the information is retained. |

| Training Content |

|

But part of the problem is not that we repeat it, but we're trying to repeat everything, and that just doesn't help, and that's where I think people get frustrated. And they find they are hearing this big message, and they can't remember any of it, and they have to hear it again. And we're not doing a good job of communicating and prioritizing and being a little more strategic about how we communicate this information. I think some of the questions that they ask in the GCP exam are situational questions, and I think those are good, because they really force you to kind of think about how to apply the guidance. I also think that a lot of times the criteria aren't always black and white. They seem black and white when you're reading them, but there's a lot of gray area that comes up in the actual practice. If you look at communications that happen in different forms, like site forms, lots of people have the same questions and issues that come up over and over again. There are different ways to interpret the guidance. So, I think instead of having 13 points that are each one sentence long, maybe [add] some more context to it, and some examples or something with situations. |

|

I conduct lots of trials, and I hear the same thing every time, so I think it's incumbent on sponsors to freshen it up. Make it interesting, give recent examples of things, not just things that have gone wrong, although that certainly tends to get their attention, but also what's going right, has worked extremely well. If it's a repeat site for you, and you know them, and you know what they do well, then highlight that. But ultimately, it's about why each of the GCP principles are important, and I wonder if you can almost do a skit or a video of patients who go through trials where these items aren't followed. Because you would watch that video and say, “Oh my gosh, I would never do that.” Or, “that's horrible, how could they do that.” But then when you kind of go through the mistakes, they think they are minor mistakes, like, “I did get their consent, but they didn't date it.” Or, “They couldn't sign, so somebody else signed it.” Whatever it might be. I think that at the point in time where people make mistakes with GCP, they don't really always understand the repercussions of that. … I think maybe even vignettes are helpful. We started adding to our GCP training the most common forty-three findings that some inspectors are documenting each year. … Because at the end of the day, there are reasons we have to follow GCP, but again people get lazy, or they get busy and they become sloppy. And so just to kind of reiterate, there are reasons why we have to follow these, and there are consequences for not following them. |

4. Discussion

Our findings highlight that clinical investigators and sponsors recognize that one or more GCP principles can be linked to the critical tasks necessary for the quality conduct of clinical trials; however, they articulated the need for significant improvement in the design, content, presentation, and training of GCP guidelines. Respondents found the current content of GCP training materials to be redundant, unengaging, and uninteresting. While respondents acknowledged the importance of GCP principles, they disclosed that, due to the burden of trainings and time constraints, GCP training has become another item to mark off the study initiation checklist rather than a learning opportunity and way to meaningfully engage with GCP content. Ideally, as described by some respondents, GCP training should focus on the key takeaways of GCP principles and not require time spent on non-critical elements such as the history and development of GCP.

Respondents also suggested that GCP training should be formatted in a manner that actively engages trainees by providing real-world examples that focus on applications in daily clinical research practice. For example, the GCP principle of informed consent could be better operationalized by trainees if the training provided hands-on application of how to write consent forms that both satisfy ethical and scientific requirements as well as improve consent form comprehension for research participants. This follows the competency-based education approach to clinical trial education by the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Consortium, which calls for training on necessary skills to perform specific job tasks, such as proper handling of investigational products and financial management of clinical sites [17]. The Network of Networks (N2) program, a non-profit collaboration among clinical research organizations in Canada, pairs mentors with at least 5 years of clinical research experience and therapeutic area expertise with less experienced mentees to facilitate knowledge and skill building by filling in the gaps of formal research training [18]. In addition, the Rockefeller University Navigation Program, where experienced research coordinators mentor less experienced investigators, has shown success in expediting IRB approval of protocol submissions [19].

The findings from our study are in line with recommendations released by the CTSA Consortium Enhancing Clinical Research Professionals’ Training and Qualification (ECRPTQ) project calling for GCP trainings that are reciprocally accepted by sponsors in an effort to reduce redundant training requests [2]. The CTSA Consortium accepted the industry standard of having GCP refresher trainings every 3 years, but further research should be conducted to better ascertain the right training frequency to simultaneously reduce redundancy and protect patient safety [2].

Our study is not without limitations. This study represents only the viewpoints of those interviewed about the quality conduct of clinical trials and ways to modify GCP training, and thus may not represent the perspectives of other investigators and sponsors. However, we anticipate that these findings may be broadly applicable to many stakeholders who are expected to follow GCP guidelines in the course of engaging with the clinical trial enterprise.

Following the CTTI methodology [20], the findings contributed to the development of recommendations for stakeholders to improve GCP training to ensure the quality conduct of sponsored clinical trials [21]. By revising the methods and content of GCP training, we can move beyond qualification as a check-box activity and instead use GCP as a critical training tool to enhance the quality conduct of clinical trials. Of note, the current version of GCP—ICH E6(R2)—is under revision, although training frequency and other requirements are currently not prescribed by ICH but are instead being determined by research sponsors and institutions.

Funding

Funding for this work was made possible, in part, by the Food and Drug Administration through cooperative agreement U18FD005292 and grant R18FD005292. Views expressed in written materials or publications and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does any mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organization imply endorsement by the United States Government. Partial funding was also provided by pooled membership fees from the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative's (CTTI) member organizations.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank participants for sharing their perspectives with us. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of the CTTI Investigator Qualification team, former project managers Jennifer Goldsack and Kirsten Wareham, and to Liz Wing for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2020.100606.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Arango J., Chuck T., Ellenberg S.S. Good clinical practice training: identifying key elements and strategies for increasing training efficiency. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2016;50:480–486. doi: 10.1177/2168479016635220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shanley T.P., Calvin-Naylor N.A., Divecha R. Enhancing clinical research professionals' training and qualifications (ECRPTQ): recommendations for good clinical practice (GCP) training for investigators and study coordinators. J Clin Transl Sci. 2017;1:8–15. doi: 10.1017/cts.2016.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaur G., Smyth R.L., Powell C.V., Williamson P. A survey of facilitators and barriers to recruitment to the MAGNETIC trial. Trials. 2016;17:607. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1724-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mentz R.J., Hernandez A.F., Berdan L.G. Good clinical practice guidance and pragmatic clinical trials: balancing the best of both worlds. Circulation. 2016;133:872–880. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Society for Clinical Research Sites . 2014. The quest for site quality and sustainability: Perceptions, principles and best practices. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macefield R.C., Beswick A.D., Blazeby J.M., Lane J.A. A systematic review of on-site monitoring methods for health-care randomised controlled trials. Clin. Trials. 2013;10:104–124. doi: 10.1177/1740774512467405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston S.C., Lewis-Hall F., Bajpai A. It's time to harmonize clinical trial site standards [Discussion Paper] Natl. Acad. Med. Perspect. 2017;2019 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative . 2015. Good Clinical Practice Training for the Conduct of Clinical Trials: Literature Review Report. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative . 2015. CTTI Recommendations: Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Training for Investigators. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health. 2010;33:77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patton M.Q. third ed. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2001. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) 2016. Integrated Addendum to ICH E6(R1): Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R2) p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . 2019. Good Clinical Practice 101: an Introduction. Slides 12-14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLellan E., MacQueen K.M., Neidig J.L. Beyond the qualitative interview: data preparation and transcription. Field Methods. 2003;15:63–84. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guest G., MacQueen K., Namey E. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2012. Applied Thematic Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calvin-Naylor N.A., Jones C.T., Wartak M.M. Education and training of clinical and translational study investigators and research coordinators: a competency-based approach. J Clin Transl Sci. 2017;1:16–25. doi: 10.1017/cts.2016.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furimsky I., Arts K., Lampson S. Developing a successful peer-to-peer mentoring program. Appl. Clin. Trials. 2014;22:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brassil D., Kost R.G., Dowd K.A., Hurley A.M., Rainer T.L., Coller B.S. The Rockefeller University navigation program: a structured multidisciplinary protocol development and educational program to advance translational research. Clin Transl Sci. 2014;7:12–19. doi: 10.1111/cts.12134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corneli A., Hallinan Z., Hamre G. The Clinical Trial Transformation Initiative: methodology supporting the mission. Clin. Trials. 2018;15:13–18. doi: 10.1177/1740774518755054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bechtel J., Chuck T., Forrest A. Improving the quality conduct and efficiency of Clinical Trials with Training: recommendations for preparedness and qualification of investigators and delegates. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2020;89:105918. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.105918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.