Abstract

Poor quality diet, physical inactivity, and obesity are prevalent, covariant risk factors for chronic disease, suggesting that behavior change techniques (BCTs) that effectively change one risk factor might also improve the others. To examine that question, registered meta-review CRD42019128444 synthesized evidence from 30 meta-analyses published between 2007 and 2017 aggregating data from 409,185 participants to evaluate whether inclusion of 14 self-regulatory BCTs in health promotion interventions was associated with greater improvements in outcomes. Study populations and review quality varied, with minimal overlap among summarized studies. AMSTAR-2 ratings averaged 37.31% (SD = 16.21%; range 8.33–75%). All BCTs were examined in at least one meta-analysis; goal setting and self-monitoring were evaluated in 18 and 20 reviews, respectively. No BCT was consistently related to improved outcomes. Although results might indicate that BCTs fail to benefit diet and activity self-regulation, we suggest that a Type 3 error occurred, whereby the meta-analytic research design implemented to analyze effects of multi-component intervention trials designed for a different purpose was mismatched to the question of how BCTs affect health outcomes. An understanding of independent and interactive effects of individual BCTs on different health outcomes and populations is needed urgently to ground a cumulative science of behavior change.

Keywords: Multiple behavior change, self-regulation, diet, obesity treatment, physical activity, health promotion

Introduction

Chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancers, are the leading causes of disease and disability worldwide (World Health Organization, 2018). Poor quality diet, physical inactivity, and obesity are risk factors that account for a significant part of the global chronic disease burden, either directly or through their effects on cardiometabolic conditions (Ezzati & Riboli, 2013).

Diet quality is suboptimal throughout much of the world. For example, 41% of U.S. adults report consuming fruit less than once per day; 22% report consuming vegetables less than once per day (Pickens, Pierannunzi, Garvin, & Town, 2018), and globally, 78% of men and women from low- and middle-income countries consume less than five fruits and vegetables per day (Hall, Moore, Harper, & Lynch, 2009). Physical inactivity is at least as prevalent as poor quality diet. In the U.S., 26% of adults report no leisure time physical activity, and fewer than 23% meet public health guidelines for aerobic activity and strength training (Benjamin et al., 2019; Pickens et al., 2018). Already, by grades 9–12, only 27% of students meet physical activity guidelines (Benjamin et al., 2019). Globally as well, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 31% of adults (28% of men, 34% of women) are insufficiently active (World Health Organization, 2019). In the U.S., 72% of adults are either overweight or obese (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Obesity, specifically, characterizes 30–39% of adults, 21% of 12–19-year-old adolescents, and 18% of 6–11-year-old children. Worldwide as well, 37% of men and 38% of women are obese (Benjamin et al., 2019). Because these three risk factors are as strongly linked as traditional risk biomarkers with the onset of chronic disease (Folsom et al., 2011), interventions to promote diet quality, physical activity, or healthy weight are necessarily a centerpiece of efforts to prevent disease and improve public health.

Not only is each risk factor prevalent on its own, but risks tend to co-occur (Fine, Philogene, Gramling, Coups, & Sinha, 2004; Pronk et al., 2004), raising hopes that a single intervention targeting multiple risk behaviors might efficiently improve long-term health. Systematic reviews of multiple behavior change interventions have been disappointing, however, showing primarily modest improvement in diet and physical activity behaviors, insufficient to reduce medical events or mortality in unselected community samples (Ebrahim et al., 2011; Meader et al., 2017). Awareness that the self-regulatory burden of changing multiple healthy diet and activity behaviors grows as the number of needed changes increases and as the surrounding context becomes less supportive of healthy choices (Schulz et al., 2012; Spring, King, Pagoto, Van Horn, & Fisher, 2015; Spring et al., 2012) has prompted a search for ways to reduce burden by introducing treatment efficiencies. One strategy has been to design interventions that harness complementary and substitute relationships among the health behaviors targeted for change (e.g., increase fruit and vegetable consumption to increase fullness and thereby passively decrease intake of saturated fat) (Spring et al., 2018; Spring et al., 2012). Such interventions have been constructed so that one behavior change brings along another “tag-along” healthy change without additional effort. That is, two or more behaviors change “coactively” because they are interrelated (Johnson et al., 2014). A second strategy, which we examine here, has been to identify generalized behavior change principles, strategies, or techniques that might have utility in improving many different risk behaviors. One group’s search for cross-cutting efficient behavior change strategies yielded a taxonomy of 26 different BCTs (Abraham & Michie, 2008), which has since been revised to a 40-BCT version (Michie, Ashford, et al., 2011), and a 93-BCT version (Michie et al., 2013). Eleven of Michie et al’s (2013) self-regulatory BCTs were analyzed in the current research, as were three additional self-regulatory intervention components drawn from related research on self-regulation.

Numerous meta-analyses have synthesized substantial clinical trial evidence evaluating the efficacy of multicomponent behavioral interventions, as compared to control, to improve diet quality (Browne, Minozzi, Bellisario, Sweeney, & Susta, 2019). physical activity (Howlett, Trivedi, Troop, & Chater, 2018), or obesity (LeBlanc et al., 2018; Lv et al., 2017). To our knowledge, no clinical trials have been designed explicitly to test the effect on diet, physical activity, or weight outcomes of including specific behavior change techniques (BCTs) in the active intervention condition and omitting them from the control condition. Nevertheless, variation in BCTs has occurred between the intervention and control arms of some trials included in meta-analytic reviews. Capitalizing on this variation, we systematically analyzed these meta-analyses to learn whether the inclusion of any self-regulatory BCT in the active intervention and its omission from control was associated with greater improvement in a diet, physical activity, or weight outcome by the active intervention group.

The current meta-review went beyond prior systematic reviews by performing a synthesis, not of the primary clinical trial evidence, but rather of prior meta-analyses systematically aggregating the results of behavioral interventions to improve diet, physical activity, or weight loss. It built upon a recent meta-review of diverse types of behavior change (Hennessy, Johnson, Acabchuk, McCloskey, & Stewart-James, 2019) by focusing specifically and in greater depth on 30 included meta-analyses that examined outcomes within the scope of this review, and by analyzing additional coded characteristics (i.e., mHealth usage, comparator group type, intervention duration – see methods for full list). Also, the current review analyzed associations between BCTs and the fine-grained outcomes that the trials were designed to assess (e.g., specific dietary changes including increased intake of fruit and vegetables and decreased intake of fat/salt/sugar-sweetened beverages, in physical activity outcomes such as increased walking and decreased sedentary behavior, or in weight change for particular at-risk populations), rather than broader, outcome constructs superimposed by reviewers (e.g., promoting healthy behavior, cardiovascular health, diabetes). The study’s overall aim was to explore which self-regulatory behavior change techniques showed evidence of association with improvement in which outcomes.1

Method

A broad, overarching meta-review (designated as the “parent review”) was conducted to explore self-regulatory BCTs in interventions spanning diverse risk and health promoting behaviors linked to chronic disease incidence (PROSPERO No. CRD42017074018). A separate protocol for the present review, which specifically focuses on physical activity, diet, and weight loss studies identified in the parent review, was registered prior to the synthesis of results (PROSPERO CRD42019128444). Prior to each stage of the review, researchers (EAH, BTJ, RLA) experienced in systematic review processes trained undergraduate and graduate students on the protocol, the screening instruments, data extraction, and the assessment of study quality. Literature screening was facilitated by Eppi-Reviewer (Thomas, Brunton, & Graziosi, 2010). Data extraction, including AMSTAR-2 quality assessment, was conducted using the survey function in RedCAP (Harris et al., 2009) and Excel. Analysis was conducted using Stata 15.1 (Stata Corp., 2017).

Inclusion Criteria

The parent meta-review sought to identify associations between interventions’ use of BCTs prompting specific self-regulatory mechanisms and a broad array of outcomes or conditions that are linked to chronic disease. Varied outcomes, including diet, medication adherence, oral health, physical activity, sleep, substance use, tobacco use, and weight/weight loss were examined and grouped into broad categories (e.g., preventing risk behaviors, diabetes). Meta-analyses were eligible for inclusion if they (a) evaluated trials of interventions for any type of health behavior related to chronic disease risk; (b) quantitatively assessed outcome differences associated with variation in any intervention component prompting one or more BCTs; (c) examined the general public or non-institutionalized individuals. To ensure relevancy to current practice, meta-analyses published before 2006 were ineligible unless they were linked to an updated review published after that date.

Eligible self-regulatory techniques used as intervention components were any that fell into one of three categories: emotion regulation, cognitive regulation, and self-related processing. To determine which intervention components were relevant proxies for self-regulation, senior research team members (EAH, BTJ, RLA) reviewed the most current (and most exhaustive) behaviour change taxonomy (Michie et al., 2013) as well as previous BCT taxonomies and articles by Michie and others for any single BCT intervention components that are considered related to self-regulation. From the taxonomies, the team selected 11 components plus the broad category of “inhibitory control training” as particularly relevant to self-regulation. Goal setting, prompt review of goals, prompt self-monitoring, prompt self-talk, action planning, and provide feedback were eligible from the most current taxonomy (Michie et al., 2013), whereas stress management and time management were identified as eligible from the 2009 taxonomy (Michie, Abraham, Whittington, McAteer, & Gupta, 2009), and barrier identification/problem solving and relapse prevention/coping planning were identified as eligible from the 2011 taxonomy (Michie, Hyder, Walia, & West, 2011). Emotional control training was identified as eligible from a 2011 manuscript that presented a taxonomy specific to healthy eating and physical activity (Michie, Ashford, et al., 2011). Even though the 2013 taxonomy is the most up-to-date, because a number of the reviews in our sample analyzed indiviudal components from earlier taxonomies, and we presented the results as reported in the individual reviews. Also, in accord with our broad interest to map self-regulation mechanisms, we allowed for new potential self-regulation mechanisms to be added if identified during the screening process. Potential new mechanisms identified by team members were discussed during weekly meetings. This process led to the addition of two BCT intervention components relevant to self-regulatory processes: self-management training and implementation intentions. BCT coding definitions appear in Supplementary Table 1.

Reviews eligible for the parent meta-review were categorized by three senior investigators into different focal health domains. Those eligible for this specific meta-review address the promotion of healthy eating, physical activity, or weight regulation (l = 30). Reviews examining health-related outcomes in addition to our primary outcomes of interest, diet, physical activity or weight were also eligible, provided they did not focus on behaviors linked to the management of chronic diseases (i.e., medication adherence) or purely risk-based behaviors (i.e., substance use/abuse), as these topics were eligible for other thematic analysis.

Dietary behaviors of interest include consuming a balanced, varied, nutritionally dense diet rich in nutrients, vitamins, and fiber, and low in empty calories. Physical activity behaviors of interest include spending time in moderate-vigorous physical activity or, conversely, in sedentary pastimes. It should be noted that most interventions aiming primarily to improve diet quality are not designed to produce weight loss, nor do they achieve it (Spring et al, 2012, 2015). Healthy diet interventions more typically target modifications in specific eating behaviors, such as fruit and vegetable intake, consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, or vitamin D intake. Conversely, interventions aiming to produce weight loss typically target both reduction in calorie and saturated fat intake and increase in physical activity, with the goal of producing a negative energy balance. Weight change is the directly measured primary outcome in such trials, and is usually mediated largely by calorie intake behaviors during the period of weight loss and by physical activity behaviors during the phase of weight loss maintenance. Effects of primary interest were associations between the eligible (and reported) BCTs, which are thought to activate specific self-regulatory mechanisms, and diet and physical activity changes or weight loss outcome, which might suggest that healthy changes are at least partially attributable to improved self-regulation.

Search and Screening Process

Two reference librarians piloted searches to refine the search strategy, and two team members (JSJ, EAH) searched multiple electronic databases (hosts) in August 2017 (Supplementary Table 2 lists all databases queried as well as the PubMed search strategy, which was modified to suit other databases). The bibliographies of eligible meta-analyses were reviewed for additional eligible publications. Any type of publication status (e.g., book chapters, dissertations, conference abstracts) or language of publication was eligible.

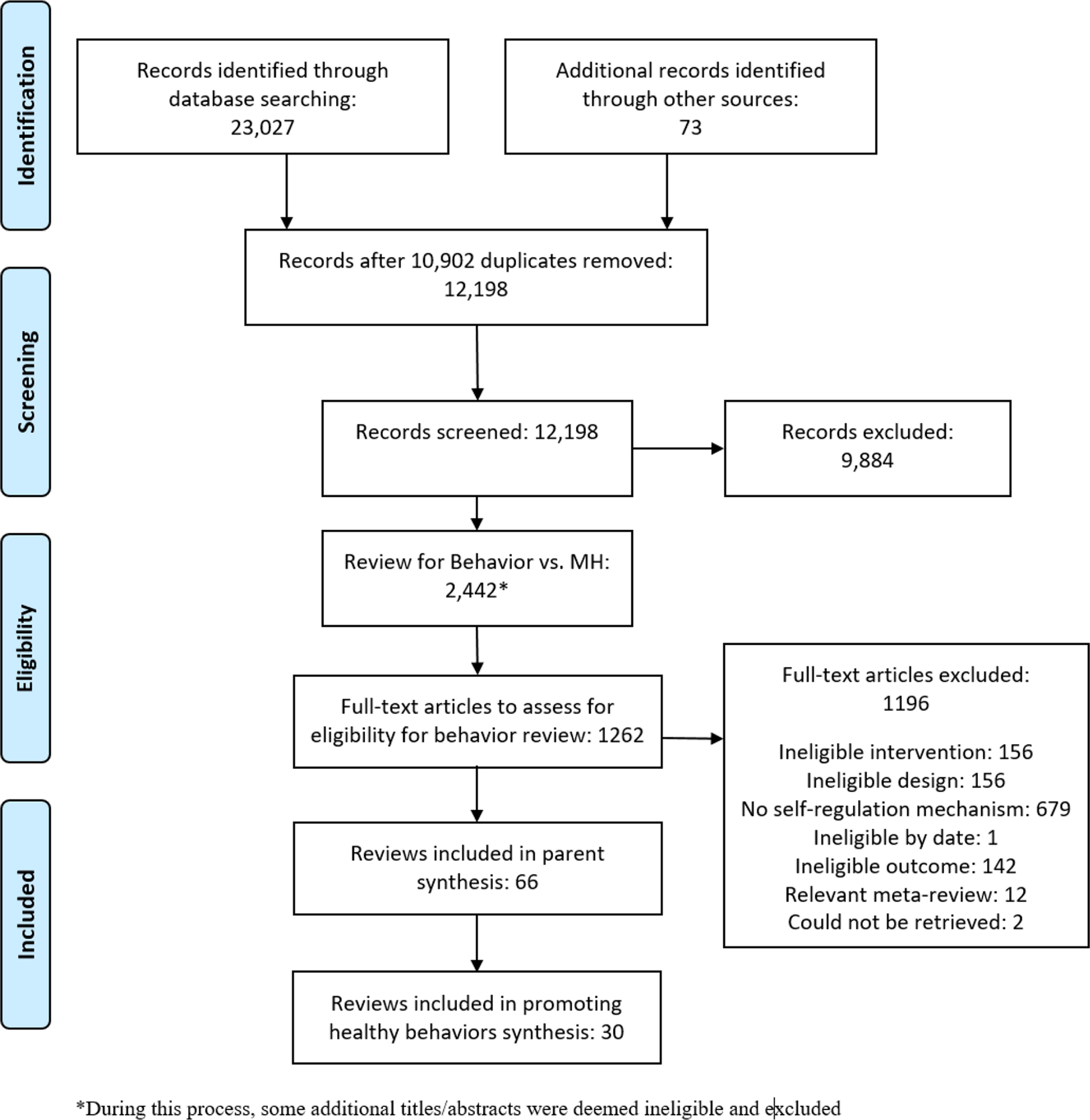

After a training period, 10% of identified meta-analyses were screened independently and in duplicate at the title/abstract level. Training for full text screening commenced with eight team members independently screening the same 15 reports, followed by splitting the remaining full texts between the team of eight. The first 25 meta-analyses in each set were screened independently and in duplicate to assess screener agreement. Junior team members were then paired with a senior team member for double-screening and senior team members screened the remaining full texts independently. All of the reviews included in the parent meta-review were again reviewed by three senior team members (EAH, BTJ, RLA) and thematically categorized via discussion and consensus into health domains of interest; the 30 reviews included in this meta-review were deemed eligible based on this process (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search and selection process for the promoting healthy behaviours review.

Data Extraction

Reviews were first coded for the items of interest in the parent meta-review. The first third (l = 22) of the 66 meta-analyses eligible for the parent review were coded independently and in duplicate by three independent reviewers using a standardized coding form. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. For the remaining studies, one coder (JSJ) independently extracted data that were checked for accuracy by one senior team member (EAH). Discrepancies were discussed and resolved. Additional items of interest, identified after completion of the parent meta-review, were included for collection in this meta-review’s protocol registration. These characteristics included: whether the setting of the primary studies and the type of delivery method were coded, reported, and assessed for impact on outcomes; whether mHealth intervention tool use was characterized in the review (described narratively if applicable); the length of the interventions included in the review (range in weeks); length of the studies included in the review (range in weeks); whether the types of control groups in the primary studies were reported and, if so, the type; authors’ interpretation of the effectiveness of the self-regulation mechanisms/BCTs they assessed (described narratively); and authors’ appraisal of study quality or other limitations of the primary studies included in the review (described narratively). For these items, all meta-analyses were coded independently and in duplicate by a team of four independent reviewers using a standardized coding form. Extracted data were checked by a senior team member (RLA) and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. Finally, after review registration, we added three additional items which were coded by a single, trained coder: whether or not review teams attempted to collect intervention manuals and study protocols, and what the success rate of those attempts were.

Assessment of Meta-Analysis Quality

Two independent reviewers (JSJ, EAH) used the AMSTAR-2 instrument (Shea et al., 2017) to assess the quality of the included meta-analyses. The AMSTAR-2 tool was slightly modified for the two questions that address the primary study design of included studies. These two questions were broken into two parts to capture those reviews that only included RCTs versus those that included both RCTs and non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (NRSIs) because the appropriate methods for addressing each type of study design in a review differ. The first third (l = 22) of meta-analyses were rated independently and in duplicate using the modified AMSTAR-2 tool, followed by discrepancy resolution. For the remaining studies, one coder independently assessed risk of bias (JSJ), and ratings were checked for accuracy by one senior team member (EAH). Discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

AMSTAR-2 items with No/Yes options were given scores of 0/2, respectively, while items with No/Partial Yes/Yes options were given scores of 0/1/2, respectively. The AMSTAR-2 score for each meta-analysis represents the proportion of items satisfying the total number of relevant quality dimensions, with a score of 100% signifying all quality dimensions were satisfied; a total calculation for each study was estimated out of the applicable items only (e.g., in cases where reviews only included RCTs). The present meta-review reports the results for all 30 meta-analyses, with qualifiers based on the AMSTAR-2 proportion scoring. For the purpose of this meta-review, meta-analyses that satisfied at least 70% of the eligible AMSTAR 2 items were considered high quality meta-analyses, while those with 50–69% completion were considered moderate quality, and reviews with less than 50% completion were considered low quality.

Synthesis

We conducted a narrative synthesis of outcomes broadly categorized into four major types: diet, physical activity, weight loss, and hybrid/multiple outcomes. The hybrid/multiple outcomes reflected aggregated change in multiple health behaviors (e.g., combined changes in diet, alcohol consumption, and caffeine consumption) or combined voluntary change in appetitive behaviors (e.g., eating and alcohol intake or inhibitory responses). Given the diversity of analyses across the included reviews, we present results in the metric originally presented in the reviews. We supplement this synthesis with quantitative descriptive summaries and examine trends across topics.

The corrected covered area (CCA; Pieper, Antoine, Mathes, Neugebauer, & Eikermann, 2014) was estimated to determine the overlap among primary studies included in the meta-analyses, and this information was used to interpret and discuss review findings. The CCA was calculated overall and for each of the four outcome domains. Meta-analyses with substantial overlap in references by the same authors/study team (i.e., if there was a primary meta-analysis and then additional meta-analyses of secondary questions) were reviewed as a single review and unique outcomes with unique samples were prioritized so as to ensure independence (e.g., van Genugten, Dusseldorp, Webb, & van Empelen, 2016; Webb, Joseph, Yardley, & Michie, 2010). Meta-analyses with minimal overlap (<10%) and unique outcome data were considered as separate reviews, although we report similar and contrasting findings with attention to overlap and reasons for similarities or differences in outcome findings.

Results

The 30 reviews eligible for this meta-review were published between 2007 and 2017 (Myear = 2014). Twenty out of 30 reviews reported total participant counts, summing to 409,185 participants (range 1,091–99,011). Searches were conducted as early as 2004, and reviews on average identified 57 articles as eligible (SD = 69.36, range 14–358). There was variability in the type of health behaviors and health promotion interventions that reviews addressed: six reviews focused on weight loss, seven focused on dietary outcomes, 16 on physical activity, and seven on hybrid/multiple outcomes. (These numbers sum to more than the total of 30 reviews synthesized because some reviews analyzed more than one outcome.) Only a small number of reviews reported collecting intervention (l = 3) and study (l = 1) protocols from study authors to assist in their coding of study-level data including the use of BCT components. Of those reviews that reported doing this, only one reported success rate of collection and it was very low: 35%. Of the 30 reviews, 16 used an established BCT classification system; 7 (23.3%) used the 40-BCT version (Michie, Ashford, et al., 2011), 6 (20%) used the 26-BCT version (Abraham & Michie, 2008), one (3%) used the 93-BCT version (Michie et al., 2013), and one (3%) used Cugelman and colleague’s (Cugelman, Thelwall, & Dawes, 2009) Communication-Based Influence Components Model. See Table 1 for characteristics of each included review, and see the supplementary files (Tables 3–6) for quantitative data regarding each outcome included in each of the four health behavior domains.

Table 1.

Characteristics of reviews included in meta-review

| Domains covered | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citation | Primary review aim | K (N) | % RCT | AMSTAR- 2 Quality | Intervention length (range, weeks) | Study length (range, weeks) | WL | DQ | PA | HB | BCT Type | # of SR-BCTs Assessed |

| Abraham & Graham-Rowe, 2009 | Effectiveness of worksite interventions to enhance PA | 37 (16516) | 70.27 | 0.39 | 0.14–52 | 0.14–78 | X | A | 4 | |||

| Adriaanse et al., 2011 | Effectiveness of implementation intentions for healthy diet changes | 21 (NR) | NR | 0.14 | 0.14–4 | 0.14–39 | X | NA | 1 | |||

| Bélanger-Gravel et al., 2013 | Investigate effectiveness of implementation intentions on physical activity among adults | 24 (6366) | 100.00 | 0.22 | 0.14–16 | 1–46 | X | NA | 3 | |||

| Brannon & Cushing, 2015 | Identify interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diet in samples of healthy children and adolescents | 74 (75541) | 100.00 | 0.41 | NR | NR | X | A | 1 | |||

| Bravata et al., 2007 | Evaluate association between pedometer use, step goals, physical activity, and health outcomes among adults in outpatient settings | 26 (2767) | 30.77 | 0.31 | 3–104 | 3–104 | X | NR | 2 | |||

| Casey et al., 2017 | Evaluate evidence of modifiable, individual-level psychosocial constructs associated with physical activity participation in people with MS | 26 (3363) | 7.69 | 0.31 | 0.14–13 | 6–26 | X | B | 1 | |||

| Conn et al., 2008 | Effectiveness of interventions to increase PA behavior among adults with chronic illnesses | 163 (22527) | NR | 0.28 | 1–208 | 1–208 | X | NR | 4 | |||

| Conn et al., 2011 | Effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity among healthy adults | 358 (99011) | NR | 0.28 | 0–303 | 0–303 | X | NR | 4 | |||

| Cugelman et al., 2011 | Online intervention features to guide the development of population-wide campaigns targeting voluntary lifestyle behaviors` | 31 (17524) | 77.42 | 0.31 | 0.14–56 | 0.14–56 | X | D | 10 | |||

| Darling & Sato, 2017 | Effectiveness of mHealth technologies on weight status, dietary and physical activity behavioral change-associated healthy weight management | 14 (2369) | 71.43 | 0.08 | 1–36 | 1–36 | X | X | X | NR | 1 | |

| Dombrowski et al., 2012 | Examines behavior-change interventions for obese adults with additional risk factors or co-morbidities | 44 (NR) | 100.00 | 0.38 | 1–48 | 1–60 | X | A | 2 | |||

| Epton et al., 2015 | Effectiveness of self-affirmation in promoting responsiveness to health-risk information | 41 (NR) | NR | 0.31 | NR | NR | X | NA | 1 | |||

| French et al., 2014 | Examine whether BCTs increase self-efficacy and physical activity behavior in non-clinical community- dwelling adults 60 years or over | 24 (NR) | 83.33 | 0.11 | NR | NR | X | B | 6 | |||

| Harkin et al., 2016 | Effectiveness of interventions on the frequency of progress monitoring and rates of goal attainment | 138 (19951) | 100.00 | 0.47 | NR | NR | X | C | 4 | |||

| Higgins et al., 2014 | Effectiveness of randomized controlled physical activity interventions that included physical activity behavior and either EXSE or BSE as outcomes | 20 (3941) | 100.00 | 0.38 | 2–104 | 2–104 | X | NR | 2 | |||

| Jones et al., 2016 | Examine mechanisms of action in aboratory studies of ICT for appetitive behavior change | 14 (1091) | 100.00 | 0.53 | 0.14–0.14 | 0.14–0.14 | X | X | NA | 1 | ||

| Knittle et al., 2010 | Efficacy of psychological interventions to increase physical activity and reduce pain, disability, depressive symptoms, and anxiety among patients with RA | 27 (NR) | 100.00 | 0.41 | 0.14–313 | 0.14–313 | X | NR | 1 | |||

| Lara et al., 2014 | Identify BCTs associated with more effective dietary interventions | 22 (63189) | 100.00 | 0.47 | 16 – 252 | 16 – 252 | X | B | 4 | |||

| Lim et al., 2015 | Effectiveness of lifestyle intervention components on weight loss in post-partum women | 46 (4342) | 71.74 | 0.56 | 1–156 | 1–156 | X | NR | 1 | |||

| Lin et al., 2017 | Effectiveness of self-management programs on medical management (i.e., interdialytic weight gain), role management (i.e., self-efficacy), and emotional management (i.e., anxiety and depression), and health-related quality of life in CKD patients | 18 (1647) | 100.00 | 0.53 | 4–26 | 4–26 | X | NA | 1 | |||

| McDermott et al., 2016 | Examine the evidence on the impact of a change in intention on behavior and (1) BCTs associated with changes in intention and (2) whether the same BCTs are also associated with changes in behavior | 25 (6306) | 0.00 | 0.14 | NR | NR | X | X | A | 7 | ||

| McEwan et al., 2016 | Effectiveness of goal setting interventions on individual PA behavior | 45 (5912) | 100.00 | 0.63 | 2–52 | 2–52 | X | A | 3 | |||

| Michie et al., 2009 | Effectiveness of individual intervention techniques and of combining five theoretically derived self-regulation techniques | 101 (44747) | 100.00 | 0.47 | 0.14–130 | 0.14–156 | X | X | A | 9 | ||

| O’Brien et al., 2015 | Effectiveness of long-term effects of PA interventions in adults aged 55–70 years | 19 (10423) | 100.00 | 0.75 | NR | NR | X | B | 4 | |||

| Olander et al., 2013 | Identify BCTs associated with increases or decreases in self-efficacy for physical activity and physical activity behavior in obese adults | 58 (NR) | NR | 0.25 | NR | NR | X | B | 10 | |||

| Sheeran et al., 2016 | Examine extent to which changing attitudes, norms, or self-efficacy leads to changes in health-related intentions and behavior | 151 (NR) | NR | 0.50 | NR | NR | X | NA | 1 | |||

| Sykes-Muskett et al., 2015 | Effectiveness of weight loss-related monetary contingency contracts | 30 (NR) | 100.00 | 0.63 | 4–52 | 4–119 | X | B | 4 | |||

| Toli et al., 2016 | Effect of if-then planning on goal attainment among people with a DSM-IV/ICD-10 diagnosis (i.e., clinical samples) or scores above a relevant cut-off on clinical measures | 29 (1652) | NR | 0.31 | NR | NR | X | X | NA | 1 | ||

| Turton et al., 2016 | Compare effectiveness of methods that have been found to change eating behaviors (i.e., implementation intentions, food-specific inhibition training and attention bias modification training) | 44 (NR) | 100.00 | 0.44 | 1–18 | 1–52 | X | NA | 2 | |||

| van Genugten et al., 2016 | Develop a taxonomy for coding the usability of online interventions: Identify what combinations of BCTs, MoDs, and usability factors influence effectiveness of online interventions to promote health behavior | 52 (NR) | 100.00 | 0.25 | X | B | ||||||

Note. BCT = Behavior change technique. A = 26-BCT version (Abraham & Michie, 2008). B = 40-BCT version (Michie et al., 2011). C = 93-BCT version (Michie et al., 2013). D = Communication-Based Influence Components Model (Cugelman et al.). CKD = Chronic kidney disease. DQ = Dietary quality. HB = Hybrid/Multiple outcome. K = Number of studies included in a review. N = Number of participants included in a review. NA = Not applicable. NR = Not reported. PA = Physical activity. RA = Rheumatoid arthritis. WL = Weight loss.

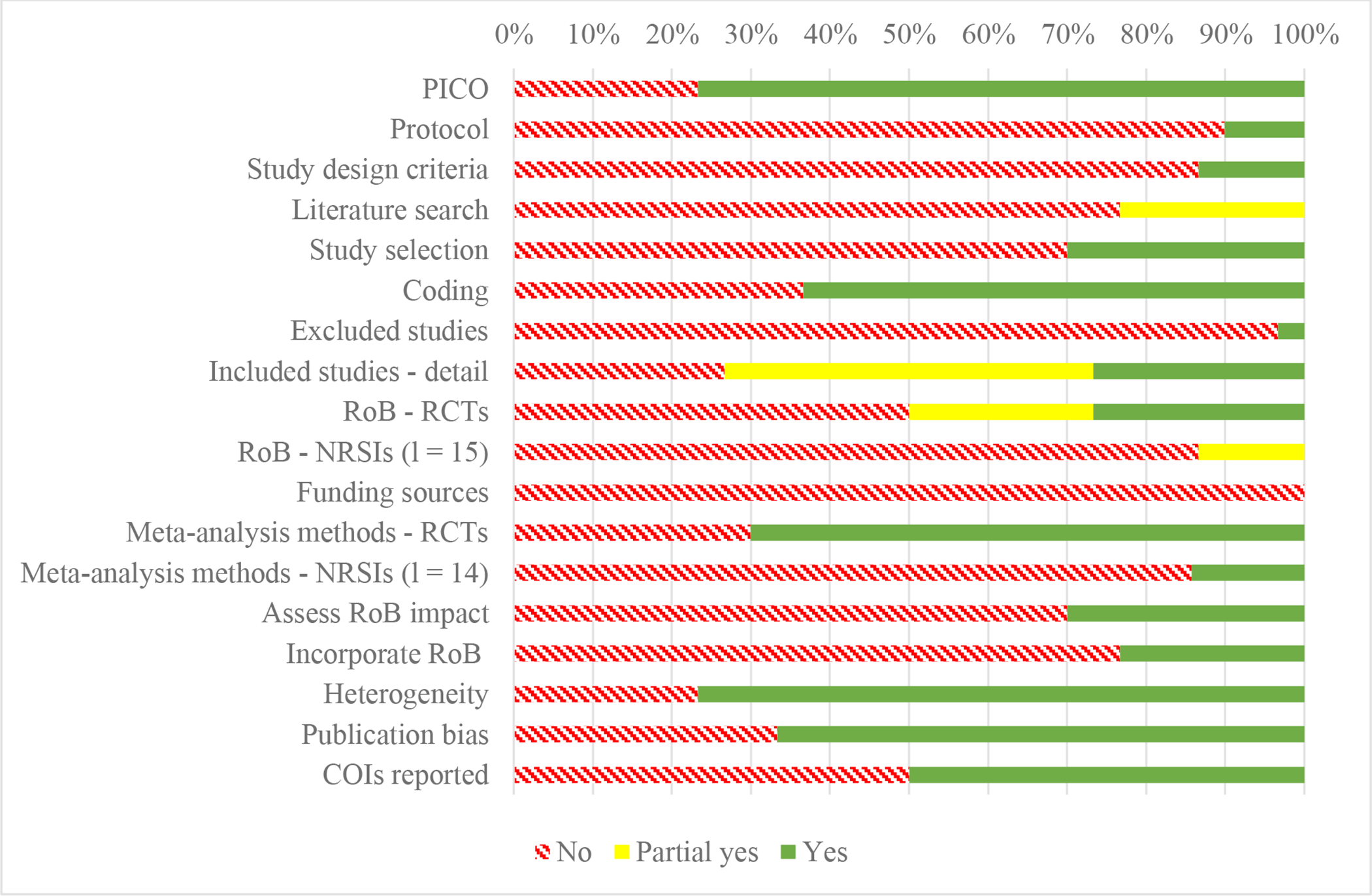

Overall review quality according to the AMSTAR-2 ratings varied but was poor, on average (M = 37.31%; SD = 16.21%; range 8.33–75%). Although the majority of reviews detailed inclusion criteria (77%), conducted data extraction in duplicate (63%), used appropriate meta-analytic techniques for combining results from RCTs (70%), examined and reported heterogeneity (77%), and examined publication bias (67%), other rigorous methods were only completed part of the time or never (reporting of funding sources of primary studies= 0%). Most reviews had not pre-registered a protocol (89%) and none had fully adequate searches (no = 77%, partial = 23%). Reviews often did not use appropriate meta-analytic methods for the examination of findings from non-randomized studies of interventions (NRSIs; 40%) and often failed to appropriately examine risk of bias for these designs (never = 43%, partially = 7%). See Figure 2 for summaries of AMSTAR-2 items across included reviews. (See supplementary tables 2 for each review coded on each AMSTAR-2 item).

Figure 2.

Quality Assessment Results according to AMSTAR-2 ratings, across all reviews. NRSI: non-randomised studies of interventions; PICO: specification of inclusion criteria including the population, intervention, comparison, outcome; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RoB: risk of bias; COI: conflict of interest.

Control Group Analysis.

Nine out of thirty-five meta-analyses in this review reported control group type. Of those nine, only two compared effects for interventions with active and inactive controls separately, but this analysis was not performed at the BCT level (Adriaanse et al., 2011; Cugelman B, Thelwall M, Dawes P, 2011). As expected, both reviews found larger overall effects when interventions used inactive controls, and reduced overall effects when interventions were compared to active controls. Specifically, one review demonstrated that that online behavior change interventions appear more efficacious when compared to waitlist and placebo, followed by comparison with lower-tech online interventions; no significant difference was found when online interventions were compared with more sophisticated control interventions (Cugelman et al, 2011). The other review demonstrated that control group type was a significant moderator for healthy diets (Adriaanse et al., 2011).

Interestingly, recommendations for best practices regarding control group design were not consistent across reviews. One review recommended future studies use no-intervention controls to avoid underestimating effectiveness (Abraham 2009), while two other reviews recommended the exact opposite - that studies use strong high quality active controls in order to avoid overestimating intervention/BCT effectiveness (Adriaanse et al, 2011, Cugelman et al, 2011).

mHealth

Only four reviews investigated mHealth tools. Two examined mHealth interventions in youth: one found BCTs present in 235 of 383 iTunes™ apps assessed, and concluded that self-monitoring via an app was beneficial for improving youth physical activity (Brannon and Cushing, 2015). The other found self-monitoring via mHealth technologies had a small but significant positive effect on diet and pediatric weight loss, but not physical activity (Darling & Sato, 2017). This second review defined mHealth more broadly to include smartphones, tablets, and other handheld devices, as well as sensors, text messages, and wearable devices. Two additional reviews looked at mHealth interventions in populations of a broader age range. One investigated the effectiveness of different online intervention features for health behavior change, as compared to placebo or traditional paper interventions: results for online interventions were positive, but effect sizes varied according to the rigor of the comparison group (Cugelman et al., 2011). The final review investigated BCT effectiveness in online interventions designed to promote healthy behavior change (hybrid/multiple outcomes), and found positive results for some BCTs but not others (van Genugten et al, 2016). The remaining reviews did not evaluate the impact of mHealth, although mHealth may have been used to deliver BCTs in some of the included studies (e.g., Casey et al. noted that one reviewed study used a goal tracking app). These findings from aggregated studies using mHealth tools to deliver interventions suggest that there may be some benefit of BCTs delivered by mHealth tools, although effects are variable across outcome, BCT, and control group rigor.

Dietary Change

Seven meta-analyses examined dietary outcomes, of which five focused solely on diet (Adriaanse, Vinkers, De Ridder, Hox, & De Wit, 2011; Darling & Sato, 2017; Jones et al., 2016; Lara et al., 2014; Turton, Bruidegom, Cardi, Hirsch, & Treasure, 2016), and two examined diet and physical activity (McDermott, Oliver, Iverson, & Sharma, 2016; Michie et al., 2009). All reviews were of low to moderate quality (9% to 61%) and, on average, achieved 43% completion of all AMSTAR-2 items. Overlap of primary studies across the reviews was minimal overall (2%). Nevertheless, two studies (Adriaanse et al., 2011; Turton et al., 2016) had high overlap due to their similar focus on how implementation intention interventions affect eating behaviors: approximately one-quarter of studies (27%) overlapped for these two meta-reviews. Of the seven reviews, three used an established BCT classification system; two used the 40-BCT version (Michie, Ashford, et al., 2011); and one used the 26-BCT version (Abraham & Michie, 2008). The most commonly reported BCTs were self-monitoring (l = 3), feedback on performance (l = 3), goal setting of behavior (l = 3), prompt review of goals (l = 3), and barrier identification/problem solving (l = 3). Two reviews focused on inhibitory control training (Jones et al., 2016; Turton et al., 2016), and two examined implementation intention interventions (Adriaanse et al., 2011; Turton et al., 2016). Populations varied, ranging from obese/overweight adolescents to people of retirement age, and there was diversity in the type of dietary outcomes assessed in the meta-analyses.

Self-monitoring.

Of the three reviews examining self-monitoring, only one found this BCT to be effective in improving dietary outcomes. Among children and adolescents, there was a small, but significant improvement in dietary outcomes when sugar-sweetened beverage and fruit and vegetable consumption were self-monitored using mHealth tools (Darling & Sato, 2017). Yet, the quality of this review was very low (achieving 9% of AMSTAR-2 items), and the meta-analysis was based on a small number of studies (k = 8). Another low-quality review (AMSTAR-2 = 16%) by McDermott and colleagues (2016) found no effect of self-monitoring on improving healthy eating/physical activity. Finally, a low quality review (AMSTAR-2 = 43%) by Michie and colleagues (2009) found that interventions combining self-monitoring with at least one other self-regulation technique derived from control systems theory (Carver & Scheier, 1982) were significantly more effective than interventions without these techniques for improving dietary quality among adults. However, this review cautioned that the magnitude of intervention effects may be overestimated due to publication bias (asymmetry in funnel plot) and weak control conditions (lack of active controls).

Goal setting.

Three reviews examined goal setting (Lara et al., 2014; McDermott et al., 2016; Michie et al., 2009), yet only one review found this component to be related to dietary behavior change. Specifically, among adults of retirement age, there was significantly greater improvement in fruit and vegetable consumption for interventions that included a ‘goal setting of outcome’ component (k = 11), in which individuals set a target for the number of fruits and vegetables to be consumed, as compared to interventions that did not set a target (k = 14) (Lara et al., 2014). Yet, no benefit was observed from ‘goal setting of behavior,’ in which the person is encouraged to make a resolution to change behavior without planning specifically how the behavior will be done.

Prompt review of goals.

Of the three reviews that examined prompting participants to review the extent to which previously set goals were achieved) (Lara et al., 2014; McDermott et al., 2016; Michie et al., 2009), none found this technique to be associated with improvements in fruit and vegetable intake (Lara et al., 2014) or healthy eating/physical activity outcomes (McDermott et al., 2016; Michie et al., 2009).

Barrier identification/problem solving.

Of the three reviews that examined identification of anticipated barriers and problem solving about how to overcome them, one moderate-quality review found evidence to support the effectiveness of this component for improving dietary outcomes (Lara et al., 2014). Specifically, among older adults, barrier identification and/or problem solving was associated with greater improvement in fruit and vegetable consumption, compared to studies that did not use this BCT (Lara et al., 2014). Yet, two other reviews failed to find a differential change in healthy eating and/or exercise between studies that included barrier identification/problem solving versus those that did not (McDermott et al., 2016; Michie et al., 2009). These reviews were of low and moderate quality, respectively.

Feedback.

There was mixed evidence for whether providing feedback improves dietary outcomes. In one moderate quality review (AMSTAR-2 = 54%), providing feedback was associated with improved fruit and vegetable intake among older adults (Lara et al., 2014). In another (McDermott et al., 2016), providing feedback was associated with reduced diet quality and physical activity, albeit this review was of poor quality; the analysis was based on a small number of studies (k = 5); and diet and exercise were combined into one effect. A third review (Michie et al., 2009), found no differences between studies that provided feedback (k = 61) versus those that did not (k = 61) on the combined outcome of healthy eating and/or physical activity.

Relapse prevention/coping planning.

Two reviews examined relapse prevention as a component of health behavior change interventions for dietary outcomes (McDermott et al., 2016; Michie et al., 2009). Neither review found evidence to support the effectiveness of this technique in improving healthy eating and/or physical activity.

Time management.

One review (Michie et al., 2009) examined time management. This review found no evidence to support the use of this technique to promote healthy eating and/or physical activity outcomes among adults; however, findings were based on a small number of studies (k = 7).

Action planning.

The single review that examined action planning, which involves detailed planning of when and where the behavior will be performed, found no differential change in healthy eating and/or exercise between studies with this component (k = 20) versus those without it (k = 14) (McDermott et al., 2016). However, this review was of very low quality.

Stress management.

Michie and colleagues’ (2009) review was the only one to investigate effects on healthy eating and/or physical activity of whether an intervention used stess management. Results showed no difference in the outcomes of studies that included this BCT (k = 4) versus those that did not (k = 118).

Prompt self-talk.

A single low-quality review (Michie et al., 2009) examined the BCT, prompt self-talk, in relation to dietary outcomes. This review found no evidence to support the effectiveness of this technique in improving health eating and/or physical activity in adults; however only a small number of studies with the BCT were included (k=4).

Inhibitory control training.

Two moderate quality reviews examined inhibitory control training, and both found evidence of a benefit in relation to improved eating behaviors. During inhibitory training, participants practice responding as rapidly as possible to neutral stimuli, while suppressing responses to target stimuli (e.g., unhealthy foods). The rationale for the training is to help people learn generalizable skills that will assist them in resisting real-world temptations. In a review of laboratory studies (Jones et al., 2016) (AMSTAR-2 = 61%), participants who received inhibitory control training chose or consumed significantly less food than controls. Effects were robust when Go/No-Go tasks were used, and more modest for Stop Signal tasks. Yet, there was high and significant heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 76%); the overall effect was small; and studies were primarily conducted among healthy young adults. In another review (Turton et al., 2016) (AMSTAR-2 = 50%), there was a significant effect of food-specific inhibition training (i.e., Stop-Signal training and Go/No-Go training), in reducing unhealthy food intake among healthy controls, but this analysis was based on only five studies. Primarily examined among undergraduate students, Stop-Signal training produced a small to medium reduction in unhealthy food intake, whereas Go/No Go training produced a medium effect. Review authors point to an urgent need to test inhibitory control training in patients with obesity, as opposed to healthy young females (Jones et al., 2016).

Implementation intention interventions.

An implementation intention is an “if-then” plan that specifies the when, where and how of a goal-directed behavior. Setting implementation intentions is a self-regulatory strategy that can improve goal attainment by planning a specific action to be undertaken in response to an anticipated cue. Two reviews examined implementation intentions (Adriaanse et al., 2011; Turton et al., 2016). Effect sizes for reducing unhealthy food intake were small, yet similar, across both reviews. In terms of an association with increased healthy food intake, implementation intentions were deemed effective in both reviews; however, Turton and colleagues (Turton et al., 2016) found a smaller effect size (d = 0.26), with high and significant heterogeneity (I2=70%), than did Adriaanse and colleagues (2011; d = 0.51). According to Turton and colleagues (2016), the difference between effect sizes in the two meta-reviews may reflect the fact that the Turton et al. (2016) review included only studies that involved randomized designs, whereas Adriaanse et al. (2011) also included nonrandomized correlational studies. However, some of the difference may also be attributable to differing scopes of the two reviews, as Turton was more recent and included twice as many studies as the Adriaanse review, reflecting a large growth in the literature. Also, the quality of Adriaanse and colleagues’ (2011) review was poor (AMSTAR-2 = 16%).

Summary.

In sum, evidence was mixed regarding the effectiveness of self-regulatory BCTs for improving dietary outcomes, and overall, the quality of the evidence was low to moderate. There was some evidence to suggest that providing feedback may improve dietary behaviour; however higher quality reviews examining more studies are needed to make conclusive statements. The results support the effectiveness of inhibitory control training, yet further research is warranted on populations other than healthy young adults. In addition, it seems possible that implementation intention interventions are associated with improved eating behaviors, but the quality of the reviews and small number of included studies should be noted. There was inconsistent evidence regarding effects of self-monitoring, goal setting and barrier identification, and no evidence to support the effectiveness of relapse prevention, prompt review of goals, time management, action planning, stress management, or prompting self-talk.

Physical Activity

Sixteen reviews investigated 12 self-regulatory BCTs for promoting physical activity. Reviews ranged from low to high- quality (8% to 75%) but, on average, only achieved 34% completion of all AMSTAR-2 items. Of the 16 reviews, nine used an established BCT classification system; five reviews used the 26-BCT version (Abraham & Michie, 2008); and four reviews used the 40-BCT version (Michie, Ashford, et al., 2011). Review publication dates ranged from 2007 and 2016, covering a combined total of 1,004 studies. Overall, overlap among the physical activity reviews was minimal: there was < 1% overlap among the 13 reviews whose primary studies overlapped. Yet, it is worth noting that one of the largest reviews (101 studies; Michie et al., 2009) had a high percentage of shared citations (24%) with the other reviews, probably because of its broad scope and size.

The most commonly examined BCTs for physical activity promotion were goal setting (l = 12), self-monitoring (l = 10), and barrier identification/problem solving (l = 8). Four reviews examined a single BCT; six reviews examined 2–4 BCTs; and four reviews examined six or more BCTs. A review by Olander et al. (2013) investigated the most BCTs (38 in total, with 13 relating to self-regulation). Study populations included healthy/non-clinical adults (l = 5), clinically ill individuals (l = 5), older adults (l = 2), and youth with and without obesity (l = 2).

Self-monitoring.

Self-monitoring of physical activity can be performed through apps, worn accelerometers or pedometers, or paper diaries. Results regarding the benefits of this BCT for physical activity promotion are mixed. Eight reviews, examining effects on 10 outcomes, found no benefit of self-monitoring on physical activity, whereas four reviews, examining five outcomes, found that adding self-monitoring significantly improved physical activity. Overall, review quality was low, with AMSTAR-2 ratings slightly higher for reviews finding null effects versus benefit (42% versus 33%). Two reviews had significant heterogeneity: one found an effect and one did not (Conn, Hafdahl, Brown, & Brown, 2008; Conn, Hafdahl, & Mehr, 2011). Conn’s (2011) meta-analysis, which included the largest number of studies (k = 69), found no significant effect for self-monitoring as an isolated BCT. However, this review also grouped interventions into behavioral strategies (e.g., goal setting, self-monitoring) and cognitive strategies (e.g., health education), then performed moderator analysis. Here, they found superior benefit in interventions with behavioral strategies, leading the authors to recommend combining self-monitoring with other behavioral strategies (Conn et al., 2011). One review found that self-monitoring improved physical activity outcomes but did not improve fitness outcomes in worksite interventions (Abraham & Graham-Rowe, 2009).

Age might be an important moderator of whether self-monitoring improves physical activity. One review found that asking older adults to self-monitor behavior reduced both actual physical activity and self-efficacy about being active. The authors (French, Olander, Chisholm, & Mc Sharry, 2014) speculated that older adults might find it unduly burdensome to perform self-regulatory BCTs. Also, a very sedentary population can find it discouraging and demotivating to become aware of how inactive they truly are. Conversely, among adolescents, Brannon and Cushing (2015) found that using an app to self-monitor resulted in significantly increased physical activity. Yet, another review examining youth with obesity did not find a significant benefit associated with self-monitoring via mHealth (e.g., using apps, text messaging) (Darling & Sato, 2017), although this review was of low quality.

Goal setting.

Of the twelve reviews that examined goal setting, six found this component positively associated with intervention effectiveness for improving physical activity (Abraham & Graham-Rowe, 2009; Bravata et al., 2007; Casey et al., 2017; Higgins, Middleton, Winner, & Janelle, 2014; McEwan et al., 2015; Olander et al., 2013), and six reviews did not (Conn et al., 2008; Conn et al., 2011; French et al., 2014; McDermott et al., 2016; Michie et al., 2009; O’Brien et al., 2015). Average review quality was poor, and the AMSTAR-2 proportion met was similar for reviews that found goal setting effective (41%) versus reviews that did not find goal setting effective (38%). Significant heterogeneity (I2=73.5%) characterized one review that found a positive effect (McEwan et al., 2015) and two reviews that did not (Conn et al., 2011, I2= 61%; Conn et al., 2008, τ2 = 0.305). Two reviews separated goal setting outcome and goal setting behavior and, in both reviews, results for goal setting outcome and behavior were consistent. However, one identified both goal setting BCTs as effective for overweight adults (Olander et al., 2013), while the other identified them both as ineffective for older adults (O’Brien et al., 2015). One suggested explanation for discrepant findings regarding goal setting’s association with increased physical activity has been that adults over age 60 may fail to benefit fully from goal setting because of reduced cognitive function and diminished interest in physical activity (French et al., 2014).

Notably, three of the four reviews that focused on more specific elements of goal setting [e.g., have a step goal (Bravata et al., 2007), set graded tasks (Abraham & Graham-Rowe, 2009), tailor exercise goals to participants (Higgins et al., 2014)] showed favorable effects for goal setting. Bravata et al. (2007) found that having a step goal was the key predictor of increased physical activity. The fourth review that examined specific elements of goal setting did not show increased benefit for prompting specific goal setting in our analysis (both conditions improved), but the authors concluded that benefit of specific goal setting was demonstrated (Michie et al., 2009).

Some of the included reviews indicate that whether goal setting is efficacious depends upon physical activity intensity and goal timeframe. McEwan et al. (2015) found goal setting associated with greater benefit when physical activity intensity level was moderate, but not when it was high. The authors speculate that goal setting’s lack of enhancement of high intensity physical activity might reflect an inability of a cognitive strategy to overcome physical limitations in fitness (i.e., most participants were quite sedentary). The same authors (McEwan et al., 2015) suggest that goal timeframe may be an important effect modifier. Whereas goal setting was associated with increased physical activity when daily or daily plus weekly goals were set, benefits were no longer present when only a (more distant) weekly goal was set.

Prompt review of goals.

Two of the six meta-reviews that investigated prompting review of goals found this BCT to be associated with increased physical activity and/or physical fitness levels (Abraham & Graham-Rowe, 2009; Olander et al., 2013). The six reviews with this BCT ranged from low to high quality (11% to 75%) but, on average, only achieved 35% completion of all AMSTAR-2 items. Of the reviews that did not show an effect, one still recommended including this BCT in interventions to improve physical activity (Michie et al., 2009). Two of the four reviews failing to find benefit from goal review examined only older adults (French et al., 2014; O’Brien et al., 2015). One review suggested that framing physical activity goals in terms of enhancing physical health may be insufficiently motivating to older adults, who may care more about maximizing meaning and positive emotions (French et al., 2014; Löckenhoff & Carstensen, 2004).

Barrier identification/problem solving.

Barrier identification/problem solving involves detecting obstacles to behavior change and figuring out how to overcome them. The problem solving draws upon an understanding of the current situational context, prior experiences with similar obstacles, and a generalized knowledge of effective strategies. Four low quality reviews found evidence of an association between problem solving about identified barriers and improved physical activity outcomes, whereas six reviews found no evidence of benefit. Of the reviews that found this BCT to be effective, one involved a non-clinical older adult population (French et al., 2014); another involved a population of adults with obesity (Olander et al., 2013); the two others used general/healthy adult populations (Bélanger-Gravel et al., 2013; Conn et al., 2011). The barriers tackled in these studies were obstacles to the goal of exercising: for example, lack of time, energy, motivation, resources.

Feedback.

A substantial evidence base indicates that, as an isolated BCT, providing performance feedback fails to enhance an intervention’s ability to increase physical activity, and may even be slightly detrimental. Specifically, five reviews (34% average on AMSTAR-2) found lack of benefit from adding this BCT; two (25% and 75% on AMSTAR-2) demonstrated smaller effect sizes for interventions with the BCT compared to without it (French 2014; McDermott 2016). Only two reviews found favorable results, but used a much smaller evidence base (a total of k = 22 with the BCT in the two favorable reviews, versus a total of k = 183 with the BCT in the six unfavorable reviews). Of the two reviews that observed favorable effects, one was Olander and colleagues’ (2013) (AMSTAR-2 = 25%), which found favorable effects for many BCTs as we have seen thus far (34 out of 38 BCTs for a population of adults with obesity). The other positive review was O’Brien’s (2015), a high quality review (AMSTAR-2 = 75%), for which the specific effect of feedback is difficult to tease apart because it always occurred with at least one other self-regulatory technique (e.g., self-monitoring, goal setting).

Relapse prevention/coping planning.

Whereas barrier identification/problem solving aims to overcome current obstacles, relapse prevention/coping planning aims to maintain a newly achieved healthier state by anticipating emergent threats that could trigger relapse and planning how to overcome them. Including relapse prevention/coping planning in an intervention was not associated with a treatment’s ability to increase physical activity in four out of five reviews that examined this BCT. Of the four negative reviews (Conn et al., 2011; French et al., 2014; McDermott et al., 2016; Michie et al., 2009), one (Conn et al., 2011) actually found physical activity to be twice as great in interventions with this BCT (0.34), versus without it (0.17), but the difference was not statistically significant. The one review that reported benefit for including relapse prevention/coping planning was again, Olander et al. (2013), using a population of adults with obesity. Reviews with discrepant outcomes for including relapse prevention in activity promotion interventions were comparable in the percent of studies with versus without this BCT (both approximately 20%) and on AMSTAR-2 ratings (both 30%).

Time management.

Two reviews (total k = 23 with BCT) of low to moderate quality (AMSTAR-2=25% & 47%) investigated time management strategies in workplace interventions and in the general population, but neither found this BCT to be beneficial for increasing physical activity (Abraham & Michie, 2008; Michie et al., 2009).

Action planning.

There is relatively strong evidence that action planning (specifying when, where, and how the physical activity behavior will be performed) shows lack of a benefit for physical activity outcomes. Four meta-reviews comparing approximately equal numbers of studies with and without action planning (65 versus 79) found null results (French et al., 2014; McDermott et al., 2016; McEwan et al., 2015; Olander et al., 2013). AMSTAR-2 ratings for these reviews ranged from 13% to 71%. In contrast, the single review that found a significant benefit of action planning (Bélanger-Gravel, Godin, & Amireault, 2013) examined only six studies with this BCT and was of low quality (AMSTAR-2 = 25%).

Stress management.

Three reviews investigated the benefits of stress management to improve physical activity; one low quality review found positive results (Olander et al., 2013), while two reviews with mixed quality did not (French et al., 2014). The number of studies with and without stress-management was more balanced in the positive review (13 out of 42 studies; k with BCT: 31%), and the study population was adults with obesity (Olander et al., 2013). The reviews that found null results for stress-management compared very few (7) studies with the BCT (5%) to many without it (100+), and examined either the general population (Michie et al., 2009) or older adults (French et al., 2014).

Self-talk.

Two reviews (total k = 15 with BCT) investigated the use of self-talk to bolster physical activity interventions, and yielded mixed results. The review that found null effects used a general adult population and was of moderate quality (53% on AMSTAR-2) (Michie et al., 2009). It is important to note that the negative Michie et al. review only compared four studies that included self-talk to 118 studies without it. In contrast, the Olander et al. (2013) review, albeit of poorer quality (AMSTAR-2 = 28%), compared a more balanced number of studies with and without self-talk (11 studies with, 31 without), and found a benefit for this BCT in a population of obese adults.

Implementation Intention interventions.

Only one review that scored 22% on AMSTAR-2 examined whether including implementation intentions in a physical activity intervention was associated with more greatly increased physical activity (Bélanger-Gravel et al., 2013). This review detected a small but significant beneficial effect for including implementation intentions in an intervention (k = 19 with BCT), and these benefits held at follow-up. Moderator analyses conducted by the authors indicated that this BCT was more effective for student and clinical samples than for samples involving the general population, and when used in conjunction with barrier management.

Self-Regulation (combined).

One low-quality review (AMSTAR-2 = 41%), examined adults with rheumatoid arthritis and took a different approach to assess the impact of including self-regulation strategies in physical activity intervention (Knittle, Maes, & De Gucht, 2010). The authors created a variable representing the extent to which an activity-promoting intervention included five self-regulation techniques: goal setting, planning, self-monitoring, providing feedback, and relapse prevention (Knittle et al., 2010). Although interventions generally increased physical activity at post-treatment (d = 0.45) and follow-up (d = 0.36), physical activity outcomes did not differ depending upon whether the intervention included high versus low levels of self-regulatory strategies.

Summary.

Physical activity meta-analyses comprised of the largest portion of the dataset for this meta-review, with sixteen meta-analyses investigating twelve different BCTs. Populations varied in age (children, l = 2; older adults, l = 2), and in health status (obesity, l = 2; chronic illness, l = 3), with one review focusing on worksite interventions, and another on iTunes apps. Overall, results were mixed for almost all BCTs, with similar numbers of reviews finding benefits and null results for each. Goal setting was the most commonly assessed BCT for physical activity, with six reviews (two high quality) finding goal setting to be effective, particularly when it is for specific, daily physical activity of moderate intensity. However, the same number of reviews with a similar range in quality failed to find support for goal setting. Other potentially promising BCTs that had at least two or more reviews showing significant benefits for improving physical activity were review of goals (one low, one medium quality), relapse prevention/coping planning (two low quality), and providing feedback (one low, one high quality). Self-monitoring also showed benefits in four low quality reviews; however, double that number of reviews showed null results for self-monitoring. Implementation intentions, which appear beneficial in improving dietary and hybrid outcomes, showed positive effects for physical activity also, but were only evaluated in one review. Evidence from existing reviews does not support benefits of time management, action planning, stress management or combined self-regulatory strategies to aid physical activity.

Weight Loss

Six meta-analyses examined weight loss outcomes (Darling & Sato, 2017; Dombrowski et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2015; Lin, Liu, Hsu, & Tsai, 2017; Sykes-Muskett, Prestwich, Lawton, & Armitage, 2015; Turton et al., 2016). Reviews were of low to moderate quality (8% to 63%) and, on average, achieved 44% completion of all AMSTAR-2 items. There was no overlap among the primary studies presented in these reviews, likely due to differences in review scope and eligible study populations. Populations were varied and included children and adults with overweight/obesity, adults with chronic kidney disease, women in the first-year post-partum, and college students. Of the six reviews, two used an established BCT classification system: one used the 26-BCT version (Abraham & Michie, 2008), and one used the 40-BCT version (Michie, Ashford, et al., 2011).

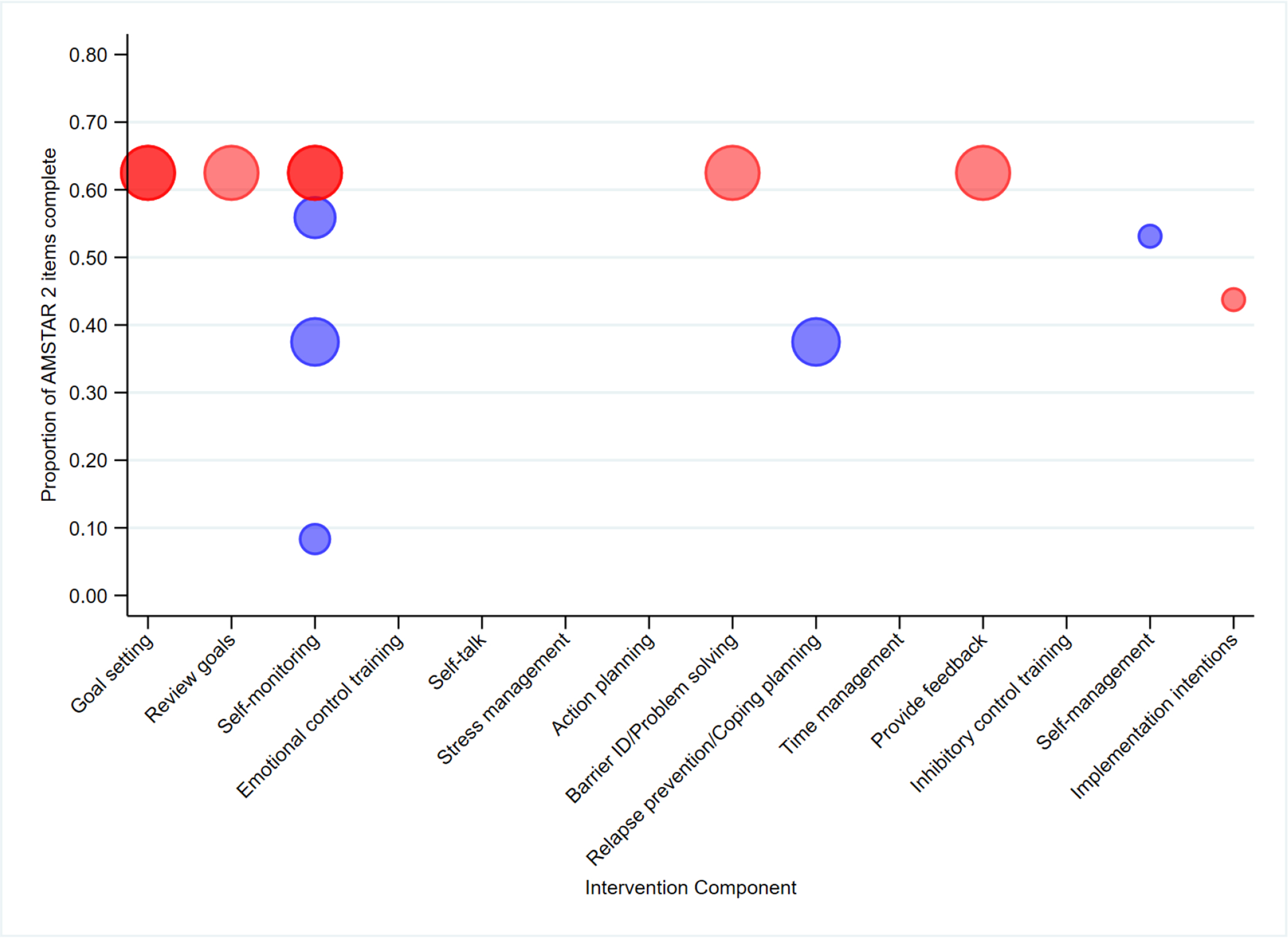

As shown in Figure 5, the most commonly analyzed BCT (l = 4) and the only one examined in more than one meta-analysis was prompt self-monitoring (Darling & Sato, 2017; Dombrowski et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2015; Sykes-Muskett et al., 2015). Other BCTs, each examined in one meta-analysis of obesity interventions were: relapse prevention (Dombrowski et al., 2012), goal setting (Sykes-Muskett et al., 2015), prompt review of goals (Sykes-Muskett et al., 2015), barrier identification (Sykes-Muskett et al., 2015), and providing performance feedback (Sykes-Muskett et al., 2015). Inhibitory control training (Turton et al., 2016), implementation intention interventions (Turton et al., 2016), and self-management interventions (Lin et al., 2017) were also each examined in one review.

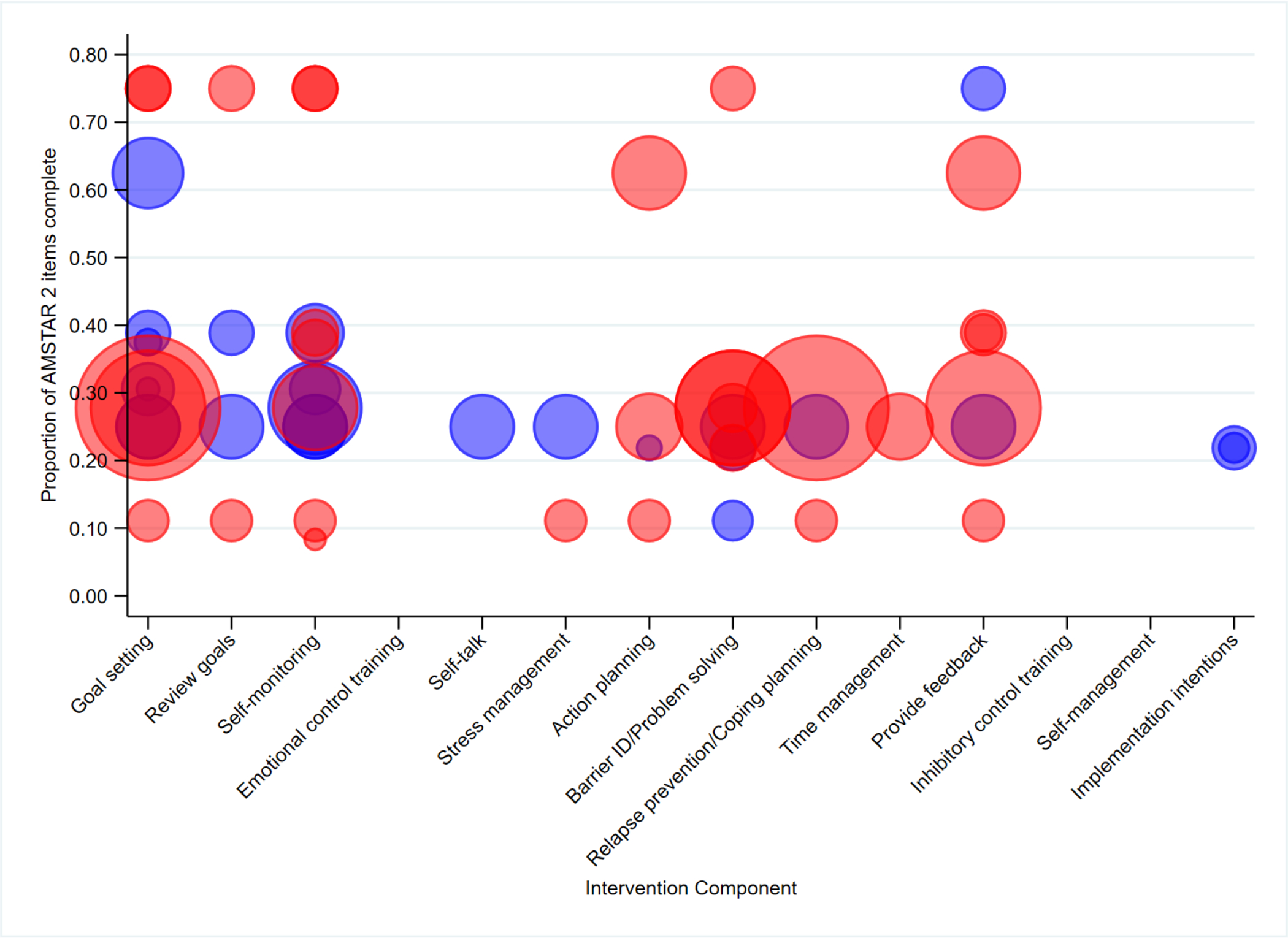

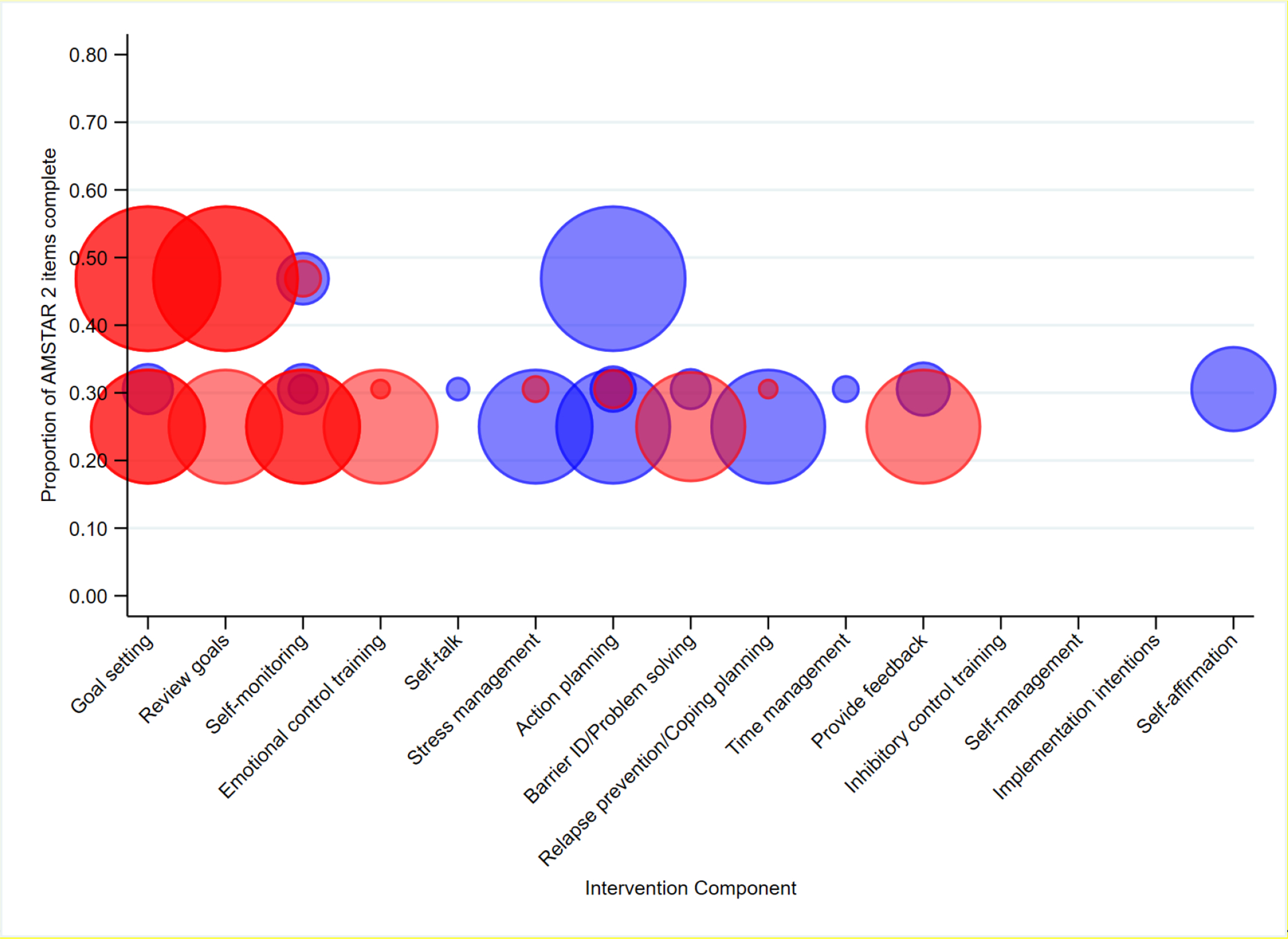

Figure 5.

Quality and supportiveness of meta-analyses supplied in favour (blue) or opposed (red) for individual self-regulation mechanisms across reviews focused on weight loss. Bubbles for each meta-analysis are sized proportional to the numbers of studies each meta-analysis included. Darker shades indicate that multiple meta-analyses rated as the same overall quality examined the same BCT.

Self-monitoring.

Of the four reviews examining self-monitoring, three found that interventions that used this BCT produced greater weight loss than interventions that did not (Darling & Sato, 2017; Dombrowski et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2015). Results for the fourth review, which included the most participants and had the highest quality rating of the obesity treatment meta-analyses, were in the same direction but not significant (Sykes-Muskett et al., 2015). This review tested whether adding self-monitoring to a monetary contingency contract (i.e., a deposit contract) augmented weight loss (Sykes-Muskett et al., 2015).

A weight loss benefit for self-monitoring was observed in reviews of quite different populations. For adults with cardiometabolic risk factors, weight loss was greater for studies whose interventions included self-monitoring (k = 15) than for those that did not (k = 8) (Dombrowski et al., 2012) in one low-quality (AMSTAR-2 = 38%) review. For post-partum women as well, a moderate-quality review (AMSTAR-2 = 56%) found that weight loss interventions that incorporated self-monitoring (k = 9) produced greater weight loss than those that did not (k = 8) (Lim et al., 2015). That review showed significant heterogeneity among the studies that included self-monitoring (Q = 62.12, p < 0.00001, I2 = .87, T2 = 10.12), but not among the studies that lacked this BCT (Q = 7.64, p = 0.37, I2 = .83, T2 = 0.02). Heterogeneity of treatment effects for interventions that use self-monitoring to foster weight loss may reflect variability in the number of energy balance indicators that an intervention requires to be tracked (e.g., weight, calories, fat, moderate-vigorous physical activity), as well as study differences in the required frequency and documentation of tracking.

Turning to weight loss interventions that use digital tools, a review of studies using mHealth technology for the treatment of childhood obesity also found significant benefits associated with self-monitoring (Darling & Sato, 2017) but had very low quality (AMSTAR-2 = 8%). Its analysis was also constrained by limited data and use of varying methods of self-monitoring (e.g., using an app to track behavior versus reporting behavior by sending weekly text messages to the researchers).

Whereas adding more BCTs to self-monitoring and monetary incentives produced a small, significant increase in weight loss (g=.14) in the review by Sykes-Muskett et al. (2015), adding a greater number of BCTs to self-monitoring did not increase weight loss in the review of interventions to treat adults with obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors (Dombrowski et al., 2012).

As Figure 5 shows in aggregate, the largest, highest quality review (Sykes-Muskett et al., (2015) failed to find a benefit for self-monitoring in weight loss, whereas three reviews of variable quality and size found a benefit. Discrepant findings are likely attributable to lack of overlap among included studies; also, review eligibility criteria indicate differing target populations and unique features of the studies included in the negative review. Interventions included in the negative Sykes-Muskett et al (2015) review included financial incentives, which constrained the study question to be whether self-monitoring augments weight loss over and above monetary incentives. Based on the review, the answer to that question appears to be no, but based on the other reviews, self-monitoring does seem to hold potential for enhancing weight loss when used alone or with other BCTs.

In addition to being associated with weight loss across varied populations, benefits of self-monitoring were seen across different monitoring tools. In the reviews examined here, the method used to track weight and energy balance behaviors differed across studies and included: paper log/diary, PDA or smartphone app, worn devices (heart rate monitor, pedometer, accelerometer), and weekly text messaging to the research team about self-reported behavior. Despite variability among assessment techniques, one review (on treatment of postpartum weight loss) reported that lifestyle interventions that included self-monitoring resulted in weight loss three times greater than those without (Lim et al., 2015).

Goal setting.

Goal setting was investigated in a single moderate quality (AMSTAR-2=63%) review (Sykes-Muskett et al., 2015) that primarily included studies of college students and used monetary contingency contracts to promote weight loss. Sykes-Muskett et al. (2015) failed to find that goal setting augmented the amount of weight loss brought about by a contingency contracting intervention.

Prompt review of goals.

Sykes-Muskett et al. (2015) was the only review to examine the effects on weight loss of prompting goal review (i.e. re-evaluation of previously set goals in light of performance). This review examined whether different BCTs, when added to financial incentives, augment weight loss; however, no effects were found for prompting review of goals.

Barrier identification/problem solving.

The effects of barrier identification/problem solving were examined in a single review (Sykes-Muskett et al., 2015). This review failed to find any evidence to support the effectiveness of this technique in augmenting weight loss.

Feedback.

Feedback was explored in one review, which focused on using monetary contingency contracts to promote weight loss, primarily among college students. Results provided no evidence to suggest that feedback was beneficial over and above the effect of contingency contracting.

Relapse prevention/coping planning.

Only one low-quality review (Dombrowski et al., 2012; AMSTAR-2 = 38%) examined the effect of relapse prevention on weight change. This meta-analysis, examining adults with cardiometabolic comorbidities, found that studies whose interventions included relapse prevention (k = 10) produced greater weight loss than those that did not (k = 13),.

Self-management training.

Self-management training comprises a package of BCTs intended to help chronically ill patients improve their self-care. Treatment components address medical adherence, role performance, and management of emotions. Among patients with chronic kidney disease, for whom weight gain between dialysis sessions constitutes a medical problem, a moderate quality review (AMSTAR-2 = 63%) found that self-management training had a small but heterogeneous effect (g = −0.36; 95% CI, [−0.60, −0.12] p < 0.01; Q = 1.78, p = 0.78, I2 < 0.001) on reducing interdialytic weight gain (Lin et al., 2017).

Inhibitory control training.

The effect of inhibitory control training was examined in one low-quality review (AMSTAR-2 = 44%) by Turton et al. (2016), which primarily evaluated studies of university students. Short-term weight loss was not increased in the one trial within the Turton review that evaluated the impact of this BCT on weight loss (Veling, van Koningsbruggen, Aarts, & Stroebe, 2014).

Implementation intention interventions.

A single low-quality review (Turton et al., 2016) examined implementation intention interventions. Across a large number of studies of weight loss among university students of ages 18 and older, there was no association between whether an intervention used implementation intentions and the amount of weight loss it produced, and there was no significant heterogeneity in this analysis (Turton et al., 2016).

Summary.

The six meta-analyses examining the association of BCTs with improved weight loss outcomes were diverse in their study populations and the BCTs they examined, and were of low to moderate quality. Results suggest that self-monitoring may be an effective component of behavioral weight loss interventions, with three out of four reviews, including one review of digital health interventions, finding inclusion of this BCT to be associated with greater weight loss. Nevertheless, replication remains needed because the largest, highest quality review found null results for self-monitoring, albeit in the specific context when this BCT was added to financial incentives. There was some evidence to suggest that relapse prevention/coping planning and self-management training might be beneficial for weight loss, and no evidence to suggest a benefit from goal setting, prompt goal review, barrier identication/problem solving, feedback, inhibitory control training, or implementation intentions. Additional research is needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn, however, since self-monitoring was the only BCT whose association with weight loss was evaluated in more than a single meta-analysis.

Hybrid/Multiple Outcomes

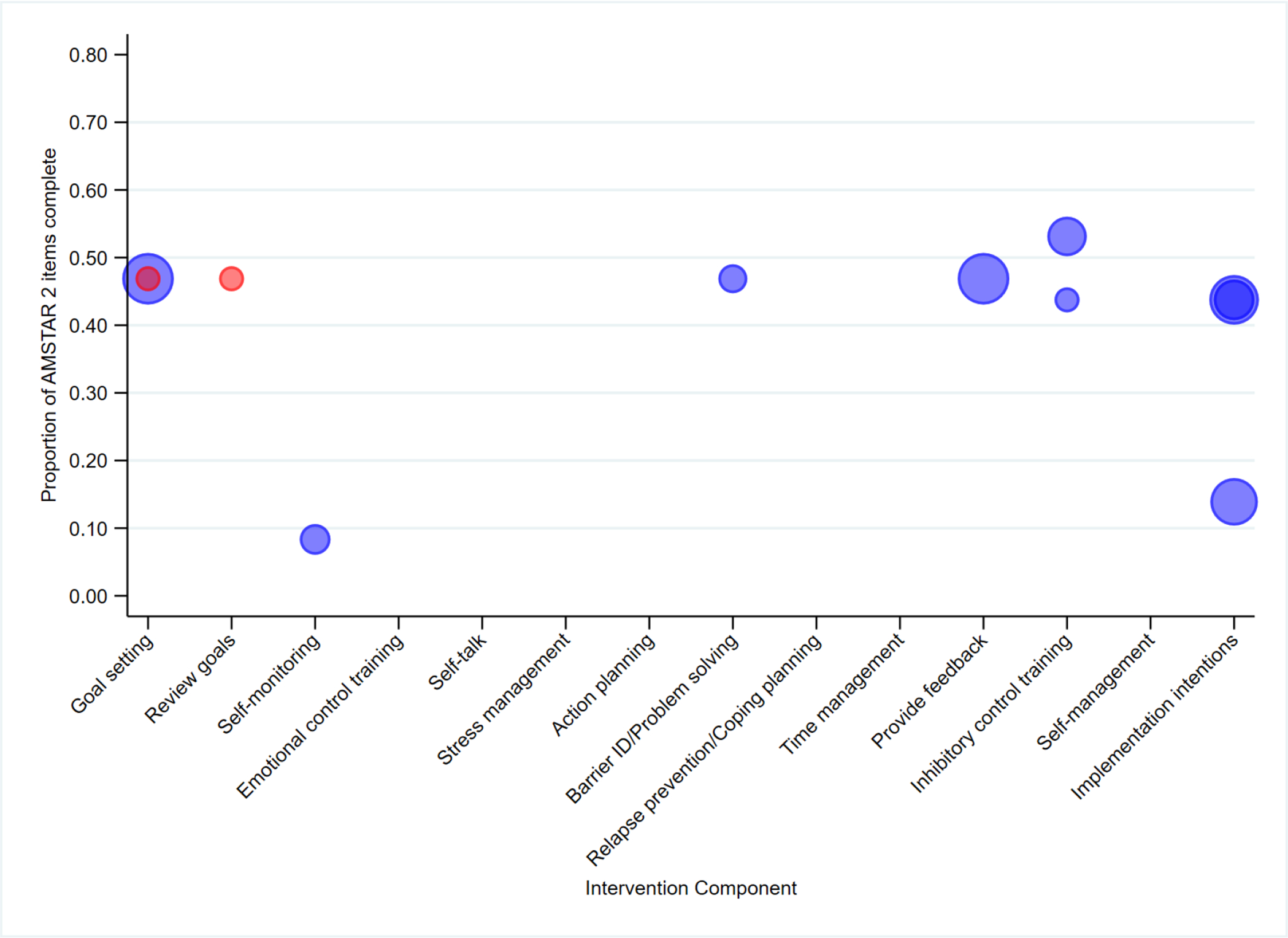

Seven meta-analyses examined other outcomes in addition to diet, physical activity, and weight-related change. Outcomes were more diverse than those discussed previously, and included multiple health-related behaviors (combined changes in physical activity, diet, and alcohol consumption), health behavior changes (combined changes in diet, alcohol consumption, and caffeine consumption), and voluntary behavior changes (appetitive and inhibitory behaviors). These reviews were of low to moderate quality (25% to 53%), achieving, on average, 38% completion of all AMSTAR-2 items. Overlap among these seven reviews was low (<1%), but two reviews (Cugelman, Thelwall, & Dawes, 2011; van Genugten, Dusseldorp, Webb, & van Empelen, 2016) had more noticeable overlap. The most commonly reported BCTs were self-monitoring (l = 3), goal setting (l = 3), and action planning (l = 3). A single review examined a direct link between change in self-regulation and health behaviors (Sheeran et al., 2016).

Self-monitoring.

Three reviews examined the effectiveness of self-monitoring, with all three distinguishing between self-monitoring of behavior versus self-monitoring of outcomes. In a meta-review of online social marketing campaigns for health behavior change (Cugelman et al., 2011), both self-monitoring of outcome and self-monitoring of behavior were associated with greater voluntary behavior change, but had significant remaining heterogeneity (I2 = 89% and I2 = 71%, respectively). In contrast, another review of online interventions (van Genugten et al., 2016) had homogenous results and found that neither prompting self-monitoring of behavior nor prompting self-monitoring of outcome was effective for changing a combination of health behaviors including physical activity, dietary intake, and alcohol consumption. The quality of this review was low, however, only achieving 25% of AMSTAR-2 items. Finally, a medium-quality review of interventions designed to promote monitoring of goal progress (Harkin et al., 2016) found that including monitoring of behavior had large positive effects on behavior (d = 0.79), but no reliable effect on outcomes (d = 0.14). In contrast, monitoring of outcome had a medium-to-large effect on outcome (d = 0.62), but did not reliably affect behavior (d = 0.17).

Goal Setting.

Of the three reviews that examined goal setting, only two found inclusion of this BCT in an intervention to be associated with improved outcomes. Cugelman and colleagues (2011) found goal setting of behavior to be an effective component of online interventions for voluntary behavior change, but also identified significant heterogeneity (I2 = 70%). In contrast, another review (van Genugten et al., 2016) found that including either goal setting of behavior or goal setting of outcome in an intervention was associated with improvement in a combination of health-related behaviors that included physical activity, dietary intake, and alcohol consumption. Finally, neither goal setting of behavior nor goal setting of outcome was associated with goal attainment in interventions designed to promote monitoring of goal progress (Harkin et al., 2016).

Prompt review of goals.

Two reviews examined prompt review of goals, but neither review found this BCT to be associated with improved outcomes. In their meta-analysis, van Genugten and colleagues (2016) found that including goal review in an intervention bore no association with whether it effectively promoted health-related behavior change, but the analysis included only two studies. In their meta-analysis, Harkin and colleagues (2016) examined the impact of prompting review of both behavioral goals and behavioral outcomes but failed to find evidence that either technique improved outcomes.

Barrier identification/problem solving.

Two reviews examined feedback on performance and barrier identification/problem solving. Quality was low in both reviews (25% to 31%). In Cugelman and colleagues’ (2011) analysis of online interventions promoting voluntary behavior change, both BCTs were effective. However, the analysis of barrier identification/problem solving was based on a relatively small number of studies (k = 10). In another review (van Genugten et al., 2016), neither feedback on performance, nor barrier identification/problem solving were effective for changing health-related behaviors (which were a combination of changes in physical activity, dietary intake, and alcohol consumption).

Feedback.

Feedback on performance was investigated in two low-quality reviews. This technique was shown to be ineffective in relation to both voluntary behavior change (Cugelman et al., 2011) and combined change in physical activity, dietary intake, and alcohol consumption) (van Genugten et al., 2016).

Relapse prevention/Coping planning.

Two reviews examined relapse prevention/coping planning as a component of health behavior change interventions. One review of online interventions found that interventions including this BCT were not effective in promoting voluntary behavior change, and there was no significant heterogeneity (Cugelman et al., 2011). Yet, the number of studies with this BCT was very small (k = 2), compared to those without (k = 29). In another review, relapse prevention/coping planning was effective in changing health-related behaviors, including physical activity, dietary intake, and alcohol consumption (van Genugten et al., 2016).

Time Management.