Abstract

In barely nine months, the pandemic known as COVID‐19 has spread over 200 countries, affecting more than 22 million people and causing over than 786 000 deaths. Elderly people and patients with previous comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes are at an increased risk to suffer a poor prognosis after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection.

Although the same could be expected from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), current epidemiological data are conflicting. This could lead to a reduction of precautionary measures in these patients, in the context of a particularly complex global health crisis.

Most COPD patients have a long history of smoking or exposure to other harmful particles or gases, capable of impairing pulmonary defences even years after the absence of exposure. Moreover, COPD is characterized by an ongoing immune dysfunction, which affects both pulmonary and systemic cellular and molecular inflammatory mediators. Consequently, increased susceptibility to viral respiratory infections have been reported in COPD, often worsened by bacterial co‐infections and leading to serious clinical outcomes.

The present paper is an up‐to‐date review that discusses the available research regarding the implications of coronavirus infection in COPD. Although validation in large studies is still needed, COPD likely increases SARS‐CoV‐2 susceptibility and increases COVID‐19 severity. Hence, specific mechanisms to monitor and assess COPD patients should be addressed in the current pandemic.

Keywords: biomass smoke, COPD, coronavirus, pneumonia, SARS‐CoV‐2, smoking

Key messages.

Although COPD is under‐represented in the comorbidities reported for patients with COVID‐19, substantial evidence points to COPD patients as ‘at high‐risk’ population in this pandemic.

Most COPD patients have a long history of exposure to harmful particles or gases, capable of impairing pulmonary defences even years after the absence of exposure.

COPD mechanisms include an immune dysfunction state that renders patients a higher vulnerability to viral and bacterial infections.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the middle of December 2019, Chinese health authorities detected a series of pneumonia cases caused by an unknown agent in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province. The causative agent was soon identified as a new strain of human‐infecting coronavirus, 1 firstly named 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) and later renamed as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). The infection disease caused by SARS‐CoV‐2, known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), varied from asymptomatic or common cold‐like symptoms such as dry cough, fever and tiredness to severe dyspnoea and respiratory failure. 2 This initial outbreak alarmingly spread through China and other countries, and barely three months later, the World Health Organization (WHO) formally declared COVID‐19 a global pandemic. 3 As of August 19, there have been more than 22,418,000 cases and 786,664 deaths by COVID‐19 worldwide. 4

Like in other infectious diseases, certain population groups have been reported to suffer a higher risk of severe clinical course of COVID‐19. Among them, patients with hypertension and diabetes seem the most significant, comprising the 23.7% and 16.2% of patients in critical conditions, respectively. 5 , 6 To a lesser extent, patients with coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease have also been repeatedly reported in severe cases, while older adults are the age group with highest mortality rates by COVID‐19. 7 , 8 Moreover, it is reasonable to expect that patients with chronic respiratory diseases are also in the population risk group. Indeed, WHO acknowledges that conditions that increase oxygen needs or reduce the ability of the body to use it properly will put patients at higher risk of serious lung conditions such as pneumonia. 9

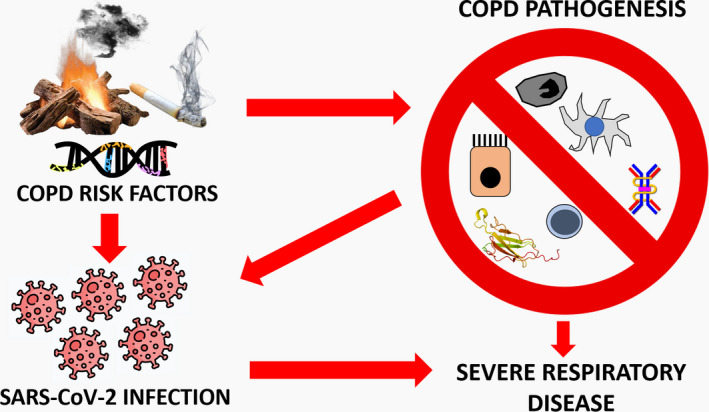

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of death and disability globally, characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation due to airway inflammation and/or alveolar abnormalities. 10 The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recognizes COPD patients among the worst affected by COVID‐19. 11 In the present review, the available evidence pointing to COPD patients as more prone to suffer a severe COVID‐19 clinical course is discussed, and the pathophysiological mechanisms linking both diseases are explained (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Pathophysiological mechanisms involved in COPD and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk factors include genetic predisposition and exposure to certain noxious particles or gases, among others. These factors could also favour COVID‐19 development. Hence, the increased genetic expression of ACE‐2 or the chronic exposure to cigarette or biomass smoke found in patients with COPD could favour SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in pulmonary cells. Moreover, COPD patients have been shown to have an immune dysfunction, affecting the mucociliary clearance and the activity of alveolar macrophages, dendritic cells, cytotoxic and regulatory T cells, as well as the production of antiviral molecules such as IFN‐β and sIgA. These make those individuals more susceptible to suffer respiratory infections and exacerbations that impair lung function. Consequently, COPD patients are at higher risk to be infected by SARS‐CoV‐2 and to suffer a severe prognosis of COVID‐19

2. THE INFLUENCE OF COPD RISK FACTORS ON COVID‐19

COPD emerges from a complex interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental factors. While over 97 independent genetic associations with lung parameters defining COPD and with COPD risk have been described, 12 cigarette smoking is by far the main environmental risk factor for COPD. Hence, between 15% and 50% of smokers develop COPD, whereas 80 to 90% of COPD patients are smokers or ex‐smokers. 13 , 14 To date, no definitive evidence on whether ever‐smokers is at an increased risk of COVID‐19. However, WHO argues that tobacco users may be at higher risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, since smoking implies repetitive hand‐to‐face contact and often sharing of mouthpieces and hoses, all of which could facilitate the virus entry. 9 In turn, a recent study on 1,099 COVID‐19 patients reported that 12.7% of current smokers died or suffered a severe clinical condition compared to only 4.7% among never‐smokers. 15 Moreover, 16.9% of severe cases were ever‐smokers compared to 11.8% of milder cases. 15 In this sense, a recent systematic review by Vardavas and Nikitara concluded that smoking is most likely associated with negative progression and adverse outcomes of COVID‐19. 16 On the other hand, a meta‐analysis conducted by Lippi and Henry based on data from Chinese patients suggests that active smoking is not significantly associated with COVID‐19 severity. 17

In spite of this contradictory data, the deleterious effects of cigarette smoking on lung defences are well‐known. 18 , 19 Smoking impairs the mucociliary clearance, alters humoral response to antigens and affects alveolar macrophages responsiveness, thus increasing the susceptibility to respiratory infections. 20 , 21 , 22 Moreover, it has also been reported that cigarette smoking decreases the number and cytotoxic activity of natural killer (NK) cells, one of the main lines of defence against viral infections. 23 , 24 It is not strange, thus, to find increased death rates from influenza and pneumonia among smokers. 25 , 26 Cigarette smoking is also associated with a systemic inflammatory pattern. 27

Importantly, it has been shown that the immune changes found in COPD patients are an amplification of those present in smokers who do not develop COPD. 28 , 29 In addition, these pulmonary and systemic alterations persist after smoking cessation. 30 , 31 Hence, an impaired response against SARS‐CoV‐2 or other pathogens could be expected despite current smoking status in COPD patients. Although the molecular basis for the amplification and ‘chronification’ of these alterations remains obscure, it is accepted that both genetic and epigenetic factors are involved. 28 In this sense, a recent study from Mostafaei and colleagues used machine‐based learning algorithms to find novel genes associated with COPD. 32 They identified 44 candidate genes whose expression was significantly regulated by smoking and/or COPD. Among the most significant, the authors stressed the novel PRKAR2B gene, which encodes an important protein kinase in cAMP signalling, a protective factor in the lung and COPD. Interestingly, PRKAR2B expression was significantly downregulated in COPD patients who smoked more than 50 packs per year. 32

In addition to cigarette smoking, other risk factors for COPD development could also be related to COVID‐19 incidence and prognosis. For instance, exposure to smoke coming from biomass burning (biomass smoke, BS), which affects 3 billion people worldwide, has also been recognized as one of the main risk factors for COPD, especially among nonsmokers. 33 Importantly, like tobacco smoke (TS), BS has been shown to alter pulmonary defences, and this effect could conceivably also be enhanced and sustained in COPD patients. 34 In this regard, although COPD caused by BS and TS present some differential hallmarks, patients with double exposure have worse blood oxygenation. 35 In any case, the impact of BS on lungs is supported by several epidemiological studies reporting increased risks of acute respiratory infections (ARIs) in people exposed to this environmental pollutant. 36 , 37 Also, in vitro studies confirm that BS exposure alters or impairs antiviral response of lung cells. 38 , 39 Although no study is available yet on the risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and BS exposure, a recent report from investigators of University of Harvard reported an increased mortality rate by COVID‐19 associated to long‐term exposure to PM2.5, one of the main components of BS. 40

Suffering from respiratory infections during childhood also been long recognized as a risk factor for COPD development. 41 However, whether this infancy infections are involved in COPD development per se or are a consequence of previous factors determining an impaired lung function is a subject of debate. Hence, although it has been reported that respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV) or a history of pneumonia during childhood are associated to impaired lung function and risk of developing COPD, 42 , 43 , 44 it has also been demonstrated that people born with a diminished airway function are more likely to suffer COPD symptoms and subsequent viral infections. 45 , 46 , 47 In any case, there is no doubt that subjects who develop COPD are at an increased risk of suffering respiratory infections, a matter of importance in the context of COVID‐19 pandemics. This subject is discussed in the next section.

3. SUSCEPTIBILITY TO RESPIRATORY VIRAL INFECTIONS IN COPD

Although COPD is mainly a chronic disease, a substantial number of patients suffer from exacerbations, defined as acute and sustained worsenings of the patient's condition from stable state and beyond normal day‐to‐day variations, requiring medication changes or hospitalization. 48 Exacerbations arise from several risk factors and triggers, being viral infections one of the most important causes. 49 Hence, viruses are responsible for a half to two‐thirds of COPD exacerbations, 50 while these pathogens are also identified in over 10% of all stable COPD patients, being associated with worse clinical outcomes. 51 Picornaviruses, influenza A, RSV and parainfluenza are among the most detected viruses in COPD exacerbations. 52 Regarding the incidence of coronaviruses infection in COPD patients, the available data are scarce. Notwithstanding, a study assessing the presence of SARS‐CoV through RT‐PCR in 141 patients with mild to moderate COPD reported no trace of infection. 53 By contrast, another study reported presence of coronavirus in 5.9% of stable COPD patients, 54 whereas several coronaviruses were associated with multiple respiratory and systemic symptoms, as well as with hospitalizations, in a cohort of 2,215 COPD patients. 55

The fact that COPD patients could be more susceptible to respiratory infections is sustained by mounting evidence. Thus, in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that patients with COPD have increased viral titre and copy numbers after rhinovirus infection than control subjects. 56 , 57 , 58 Moreover, an upregulation of intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 (ICAM‐1), which is the rhinovirus major group receptor, has been reported in airways and parenchyma of COPD patients. 59 , 60 Likewise, Seys and co‐workers showed an upregulated expression of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP4), a type II transmembrane glycoprotein that serves as receptor for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV), in COPD patients. 61 Interestingly, both DPP4 mRNA and protein levels were inversely correlated with lung function and diffusing capacity. The authors concluded that increased DPP4 expression could partially explain why COPD patients are more susceptible to MERS‐CoV. 61 Regarding COVID‐19, a recent paper by Leung and co‐workers investigated the expression of angiotensin‐converting enzyme II (ACE‐2) in the lower tract of COPD patients, 62 since this transmembrane metallocarboxypeptidase has been shown to act as the doorway that allows SARS‐CoV‐2 into the lungs. 63 The authors reported that COPD patients show an increased airway gene expression of ACE‐2 compared to control subjects and ACE‐2 were inversely related to FEV1, suggesting a dose‐dependent response. 62 Hence, these findings reinforce the idea of a higher risk for SARS‐CoV‐2 in subjects with COPD. Finally, it has been shown that viral infection may increase the number of bacteria in the lower airways and even facilitate a subsequent bacterial infection in COPD. 64 Indeed, 20 to 30% of COPD patients hospitalized for exacerbations present viruses and bacteria coinfection, and these coinfections increase the severity of the exacerbations. 65 , 66 , 67 Hence, one may anticipate that COPD patients with COVID‐19 are at higher risk to develop a more severe pneumonia.

4. IMMUNE DYSFUNCTION IN COPD

The increased susceptibility to respiratory infections leading to disease severity may reflect a defective immunity in COPD. 68 Indeed, both the innate response to pathogens and the role of adaptive immune system to such challenges are impaired in COPD, which can result in recurrent infections. 29 , 69 , 70

Hence, despite increased numbers of alveolar macrophages have been reported in COPD patients, their phagocytic ability is reduced as compared to smokers without COPD. 71 , 72 , 73 Moreover, alveolar macrophages of patients with COPD also exhibit an altered capacity to secrete proinflammatory mediators and proteases, express surface and intracellular markers, induce oxidative stress and engulf apoptotic cells. 74 In turn, some studies have found reduced numbers and impaired maturation of dendritic cells in COPD patients. 75 , 76 , 77 In addition, interferon (IFN) signalling which plays a key role in the innate antiviral response is also impaired in COPD. Thus, Mallia and co‐workers reported a reduced production of IFN‐β in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells from subjects with COPD after rhinovirus infection. 57 Recent results from our research group also showed a significative reduction expression of IFN‐β and its main transcription factor, IRF‐7, in lung epithelium and alveolar macrophages of COPD patients. 78 This reduction was also observed in pulmonary mRNA levels of these immune mediators. Since IFN‐β has proven to inhibit coronavirus replication, 79 , 80 COPD patients could be especially susceptible in front of COVID‐19.

Regarding adaptive immunity, a downregulation of the epithelial polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) has been observed in COPD patients. 81 PIgR is essential for generation of mucosal sIgA, an effective virus‐neutralizing molecule, 82 and its reduction was positively correlated with COPD's severity. 81 On another front, CD8 + T cells are critical for respiratory viral clearance and provide protection against secondary infections. 83 In this sense, McKendry and co‐workers have demonstrated a defective response of CD8 + T cells against H3N2 influenza virus in subjects with COPD. 84 Interestingly, they found a downregulation of the T‐cell receptor signalling molecule CD247 (ζ‐chain) in lung CD8 + of these patients compared with smokers and healthy controls. They also observed a reduced T‐cell cytotoxicity and an upregulation of programmed cell death protein‐1 (PD‐1), which renders immunosuppressive actions on CD8 + cells. 84 In another study, the same research group demonstrated that the impaired cytotoxic activity of CD8 + T cells was paralleled by a reduced proportion of CD4 + T cytotoxic cells in lung tissue from COPD patients. 85 In addition to cytotoxic T cells, other T subtypes seem to be altered in COPD. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are a subtype of lymphocytes that express the transcription factor FoxP3, which, among other functions, have been shown to limit the extent of tissue damage that occurs during a virus infection. 86 , 87 Importantly, COPD patients exhibit decreased numbers of pulmonary Treg cells, as well as reduced levels of FoxP3 mRNA and lung interleukin 10 secretion than controls. 88 Collectively, these findings indicate a characteristic immune dysfunction in COPD that could impact on the pulmonary antiviral defence.

Finally, it is noteworthy that the impaired immune response is not only restricted to pulmonary cells of COPD patients. Interestingly, a recent paper by Agarwal and co‐workers have demonstrated that human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from COPD patients have a reduced ability to metabolize carbohydrate or fatty acids, suggesting a metabolic impairment in systemic immune cells in COPD. 89 Moreover, the neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is increased both in stable and exacerbated COPD patients. 35 , 90 This is particularly relevant, since a recent paper by Liu and co‐workers has shown that NLR is an independent risk factor for the in‐hospital mortality for COVID‐19. 91 The study, which was performed on 245 COVID‐19 patients, reported that subject in the highest tertile had a 15.04‐fold higher risk of mortality (OR = 16.04; 95% CI, 1.14 to 224.95; P = .0395) after adjustment for potential confounders, when compared with patients in the lowest tertile. 91

5. COPD AND COVID‐19: AVAILABLE EPIDEMIOLOGICAL DATA

So far, information on COVID‐19 incidence and clinical course on COPD patients is scarce. A recent meta‐analysis by Lippi and Henry has reported that COPD is associated with a significant, over fivefold risk of severe COVID‐19 infection. 92 However, the reported prevalence of COPD in patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 is surprisingly low. Hence, the prevalence of chronic respiratory disease and COPD in two cohorts of Chinese COVID‐19 patients has been only 2.4% (44,672 patients studied) 93 and 1.4% (140 patients studied), 94 respectively. Moreover, in the USA population, chronic respiratory diseases were comorbidities in 8.5% of COVID‐19 patients. 95 In this regard, a group of investigators leaded by Dr Àlvar Agustí recently published a paper suggesting that the use inhaled corticosteroids could reduce the risk of infection or of developing COVID‐19 symptoms, since previous in vitro studies has shown that these drugs are capable of suppressing coronavirus replication. 96 The same authors, however, warned about the fact that systemic corticosteroids were counterproductive to treat SARS. 96 , 97 In this respect, it has also been shown that fluticasone propionate, an inhaled corticosteroid, impairs innate and acquired antiviral immune responses leading to delayed virus clearance and increases pulmonary bacterial load during virus‐induced exacerbations in a murine model of COPD exacerbation. 98

6. CONCLUSIONS

In nine months, the COVID‐19 pandemic has spread to more than 200 countries and now the main focus of infection is centred in North and South America. Consequently, governments and institutions work relentlessly to stop the spread of the SARS‐CoV‐2 worldwide, while trying to manage the sanitary, economic and social crisis we are facing. Since a vaccine against this coronavirus is not available yet, the most important thing is to take steps to stop its spread and to protect those people at highest risk of infection or developing a more serious clinical course.

While hypertension and diabetes are the two comorbidities most clearly related to COVID‐19 susceptibility, available data regarding COPD are contradictory. It is probable that COPD patients are under‐represented in intensive care settings due to their pre‐existing poor prognosis and decisions to limit the treatment to palliative care in situations of poor prognosis. Peoples in risk groups are advised to self‐isolate, and most severe COPD patients most probably do not move out of their homes due to the limits of the disease for their performance in general. Therefore, the incidence of COVID‐19 may be lower in COPD patients. Nevertheless, substantial evidence points to COPD patients as a particularly susceptible group to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and to a worst prognostic. Indeed, most COPD patients are or, at least, have been exposed to noxious gases or pollutants capable of altering pulmonary defences during many years. Also, the immune dysfunction observed in COPD may cause increased susceptibility to respiratory viral infections and an impaired inflammatory response against these challenges. Finally, it is noteworthy that SARS survivors showed a significative impairment of pulmonary function months after recovery. 99 If the same is confirmed for COVID‐19 patients, a serious impact in the clinical course and quality of life in those with COPD as comorbidity could be expected, since they already have a diminished lung function. In any case, more research in larger patient groups will bring more data on COPD and COVID‐19 severity and associations of immune dysfunction in COPD with COVID‐19 risk. It would be important to know whether the patients are more prone for severe infection due to impaired immune responses and whether the clinical picture of the disease and the cytokine storm differ in these patients. Also, genotyping and complete phenotyping (including serological, radiological and histopathological assessment) will help to understand the mechanistic insights of the susceptibility to COVID‐19. 100

In light of all these facts, COPD patients should be considered as a high‐risk group in COVID‐19. Hence, sanitary authorities must apply specific mechanisms to monitor and assess patients with COPD in the context of the current pandemic.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Dr Jack White for helping with the literature revision and Ms Marta Chmielewska for linguistic advice.

Olloquequi J. COVID‐19 Susceptibility in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;50:e13382. 10.1111/eci.13382

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhu NA, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R, Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID‐19). In: Abai B, Abu‐Ghosh A, eds. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID‐19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157‐160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed August 19, 2020.

- 5. Zhang L, Liu Y. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: a systematic review. J Med Virol. 2020;92(5):479‐490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X. COVID‐19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(5):259–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID‐19 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):21e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case‐fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID‐19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020.323(18):1775–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. (WHO) WHO . Q&A on smoking and COVID‐19. In: 2020.

- 10. 2020 GLOBAL STRATEGY FOR PREVENTION, DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF COPD. 2020. https://goldcopd.org/wp‐content/uploads/2019/12/GOLD‐2020‐FINAL‐ver1.2‐03Dec19_WMV.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2020.

- 11. GOLD COVID‐19 GUIDANCE. 2020. https://goldcopd.org/gold‐covid‐19‐guidance/. Accessed July 30, 2020.

- 12. Wain LV, Shrine N, Artigas MS, Erzurumluoglu AM. Genome‐wide association analyses for lung function and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease identify new loci and potential druggable targets. Nat Genet. 2017;49(3):416‐425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lokke A, Lange P, Scharling H, Fabricius P, Vestbo J. Developing COPD: a 25 year follow up study of the general population. Thorax. 2006;61(11):935‐939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim EJ, Yoon SJ, Kim YE, Go DS, Jung Y. Effects of aging and smoking duration on cigarette smoke‐induced COPD severity. J Korean Med Sci. 2019;34(Suppl 1):90e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guan W‐J, Ni Z‐Y, Hu Y, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020.382(18):1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vardavas CI, Nikitara K.COVID‐19 and smoking: A systematic review of the evidence. In: Tob Induc Dis. Vol 18. Greece 2020:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. Lippi G, Henry BM. Active smoking is not associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Eur J Intern Med. 2020.75:107–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Herr C, Beisswenger C, Hess C, et al. Suppression of pulmonary innate host defence in smokers. Thorax. 2009;64:144‐149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stampfli MR, Anderson GP. How cigarette smoke skews immune responses to promote infection, lung disease and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(5):377‐384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dye JA, Adler KB. Effects of cigarette smoke on epithelial cells of the respiratory tract. Thorax. 1994;49(8):825‐834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marcy TW, Merrill WW. Cigarette smoking and respiratory tract infection. Clin Chest Med. 1987;8(3):381‐391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gaschler GJ, Zavitz CCJ, Bauer CMT, et al. Cigarette smoke exposure attenuates cytokine production by mouse alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38(2):218‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tollerud DJ, Clark JW, Brown LM, et al. Association of cigarette smoking with decreased numbers of circulating natural killer cells. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139(1):194‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mian MF, Lauzon NM, Stampfli MR, Mossman KL, Ashkar AA. Impairment of human NK cell cytotoxic activity and cytokine release by cigarette smoke. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83(3):774‐784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wong CM, Yang L, Chan KP, et al. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for influenza‐associated mortality: evidence from an elderly cohort. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(4):531‐539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bello S, Menéndez R, Antoni T, et al. Tobacco smoking increases the risk for death from pneumococcal pneumonia. Chest. 2014;146(4):1029‐1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tibuakuu M, Kamimura D, Kianoush S, et al. The association between cigarette smoking and inflammation: The Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy (GENOA) study. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(1):16‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hogg JC. Pathophysiology of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2004;364(9435):709‐721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shapiro SD. End‐stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the cigarette is burned out but inflammation rages on. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(3):339‐340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu Y, Pleasants RA, Croft JB, et al. Smoking duration, respiratory symptoms, and COPD in adults aged >/=45 years with a smoking history. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1409‐1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mostafaei S, Kazemnejad A, Azimzadeh Jamalkandi S, et al. Identification of novel genes in human airway epithelial cells associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) using machine‐based learning algorithms. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Salvi S, Barnes PJ. Is exposure to biomass smoke the biggest risk factor for COPD globally?Chest. Vol 138. United States. 2010;3‐6. 10.1378/chest.10-0645 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34. Olloquequi J, Silva OR. Biomass smoke as a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effects on innate immunity. Innate Immun. 2016;22(5):373‐381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Olloquequi J, Jaime S, Parra V, et al. Comparative analysis of COPD associated with tobacco smoking, biomass smoke exposure or both. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dherani M, Pope D, Mascarenhas M, Smith KR, Weber M, Bruce N. Indoor air pollution from unprocessed solid fuel use and pneumonia risk in children aged under five years: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(5):390‐398c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith KR, McCracken JP, Weber MW, et al. Effect of reduction in household air pollution on childhood pneumonia in Guatemala (RESPIRE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9804):1717‐1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Capistrano SJ, Zakarya R, Chen H, Oliver BG. Biomass smoke exposure enhances rhinovirus‐induced inflammation in primary lung fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(9):1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McCarthy CE, Duffney PF, Wyatt JD, Thatcher TH, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Comparison of in vitro toxicological effects of biomass smoke from different sources of animal dung. Toxicol In Vitro. 2017;43:76‐86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wu X, Nethery RC, Sabath BM, Braun D, Dominici F. Exposure to air pollution and COVID‐19 mortality in the United States. medRxiv.. 2004. 2020.2004.2005.20054502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Savran O, Ulrik CS. Early life insults as determinants of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adult life. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:683‐693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Broughton S, Sylvester KP, Fox G, et al. Lung function in prematurely born infants after viral lower respiratory tract infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(11):1019‐1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hayden LP, Hobbs BD, Cohen RT, et al. Childhood pneumonia increases risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the COPDGene study. Respir Res. 2015;16:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chan JY, Stern DA, Guerra S, Wright AL, Morgan WJ, Martinez FD. Pneumonia in childhood and impaired lung function in adults: a longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):607‐616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pike KC, Rose‐Zerilli MJ, Osvald EC, et al. The relationship between infant lung function and the risk of wheeze in the preschool years. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46(1):75‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Narang I, Bush A. Early origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17(2):112‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stocks J, Sonnappa S. Early life influences on the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2013;7(3):161‐173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rodriguez‐Roisin R. Toward a consensus definition for COPD exacerbations. Chest. 2000;117(5 Suppl 2):398s‐401s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wedzicha JA. Role of viruses in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1(2):115‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Frickmann H, Jungblut S, Hirche TO, Gross U, Kuhns M, Zautner AE. The influence of virus infections on the course of COPD. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp). 2012;2(3):176‐185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kefala AM, Fortescue R, Alimani GS, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of respiratory viruses in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and exacerbations: a systematic review and meta‐analysis protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10(4):e035640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rohde G, Wiethege A, Borg I, et al. Respiratory viruses in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring hospitalisation: a case‐control study. Thorax. 2003;58(1):37‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rohde G, Borg I, Arinir U, et al. Evaluation of a real‐time polymerase‐chain reaction for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus in patients with hospitalised exacerbation of COPD. Eur J Med Res. 2004;9(11):505‐509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Seemungal T, Harper‐owen R, Bhowmik A, et al. Respiratory viruses, symptoms, and inflammatory markers in acute exacerbations and stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(9):1618‐1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gorse GJ, O'Connor TZ, Hall SL, Vitale JN, Nichol KL. Human coronavirus and acute respiratory illness in older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(6):847‐857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schneider D, Ganesan S, Comstock AT, et al. Increased cytokine response of rhinovirus‐infected airway epithelial cells in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(3):332‐340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mallia P, Message SD, Gielen V, et al. Experimental rhinovirus infection as a human model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):734‐742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Footitt J, Mallia P, Durham AL, et al. Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress and Histone Deacetylase‐2 Activity in Exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2016;149(1):62‐73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Di Stefano A, Maestrelli P, Roggeri A, et al. Upregulation of adhesion molecules in the bronchial mucosa of subjects with chronic obstructive bronchitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(3 Pt 1):803‐810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shukla SD, Mahmood MQ, Weston S, et al. The main rhinovirus respiratory tract adhesion site (ICAM‐1) is upregulated in smokers and patients with chronic airflow limitation (CAL). Respir Res. 2017;18(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Seys LJM, Widagdo W, Verhamme FM, et al. DPP4, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Receptor, is Upregulated in Lungs of Smokers and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(1):45‐53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Leung JM, Yang CX, Tam A, et al. ACE‐2 expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: implications for COVID‐19. Eur Respir J. 2020;2000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhou P, Yang X‐L, Wang X‐G, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wilkinson TM, Hurst JR, Perera WR, Wilks M, Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. Effect of interactions between lower airway bacterial and rhinoviral infection in exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2006;129(2):317‐324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Papi A, Bellettato CM, Braccioni F, et al. Infections and airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severe exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(10):1114‐1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Welte T, Miravitlles M.Viral, bacterial or both? Regardless, we need to treat infection in COPD. In: Eur Respir J. Vol 44. England 2014:11–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67. Wang H, Anthony D, Selemidis S, Vlahos R, Bozinovski S. Resolving Viral‐Induced Secondary Bacterial Infection in COPD: A Concise Review. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Su YC, Jalalvand F, Thegerstrom J, Riesbeck K. The Interplay Between Immune Response and Bacterial Infection in COPD: focus upon non‐typeable Haemophilus influenzae. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Brusselle GG, Joos GF, Bracke KR. New insights into the immunology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2011;378(9795):1015‐1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bhat TA, Panzica L, Kalathil SG, Thanavala Y. Immune dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(Suppl 2):S169‐175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Retamales I, Elliott W, Meshi B, et al. Amplification of inflammation in emphysema and its association with latent adenoviral infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(3):469‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Berenson CS, Garlipp MA, Grove LJ, Maloney J, Sethi S. Impaired phagocytosis of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae by human alveolar macrophages in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(10):1375‐1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Berenson CS, Wrona CT, Grove LJ, et al. Impaired alveolar macrophage response to Haemophilus antigens in chronic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(1):31‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kapellos TS, Bassler K, Aschenbrenner AC, Fujii W, Schultze JL. Dysregulated functions of lung macrophage populations in COPD. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:2349045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Demedts IK, Bracke KR, Van Pottelberge G, et al. Accumulation of dendritic cells and increased CCL20 levels in the airways of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(10):998‐1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lommatzsch M, Bratke K, Knappe T, et al. Acute effects of tobacco smoke on human airway dendritic cells in vivo. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(5):1130‐1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Freeman CM, Martinez FJ, Han MK, et al. Lung dendritic cell expression of maturation molecules increases with worsening chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(12):1179‐1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Garcia‐Valero J, Olloquequi J, Montes JF, et al. Deficient pulmonary IFN‐beta expression in COPD patients. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hensley LE, Fritz LE, Jahrling PB, Karp CL, Huggins JW, Geisbert TW. Interferon‐beta 1a and SARS coronavirus replication. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):317‐319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sainz B Jr, Mossel EC, Peters CJ, Garry RF. Interferon‐beta and interferon‐gamma synergistically inhibit the replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome‐associated coronavirus (SARS‐CoV). Virology. 2004;329(1):11‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gohy ST, Detry BR, Lecocq M, et al. Polymeric immunoglobulin receptor down‐regulation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Persistence in the cultured epithelium and role of transforming growth factor‐beta. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(5):509‐521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Li Y, Jin L, Chen T. The effects of secretory IgA in the mucosal immune system. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:2032057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Schmidt ME, Varga SM. The CD8 T cell response to respiratory virus infections. Front Immunol. 2018;9:678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. McKendry RT, Spalluto CM, Burke H, et al. Dysregulation of antiviral function of CD8(+) T cells in the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease lung. Role of the PD‐1‐PD‐L1 Axis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(6):642‐651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Staples KJ, McKendry RT, Spalluto CM, Wilkinson TMA. Evidence for cell mediated immune dysfunction in the COPD lung: the role of cytotoxic CD4+ T cells. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(suppl 59):PA2603. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Veiga‐Parga T, Sehrawat S, Rouse BT. Role of regulatory T cells during virus infection. Immunol Rev. 2013;255(1):182‐196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Karkhah A, Javanian M, Ebrahimpour S. The role of regulatory T cells in immunopathogenesis and immunotherapy of viral infections. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;59:32‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lee S‐H, Goswami S, Grudo A, et al. Antielastin autoimmunity in tobacco smoking‐induced emphysema. Nat Med. 2007;13(5):567‐569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Agarwal AR, Kadam S, Brahme A, et al. Systemic Immuno‐metabolic alterations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Respir Res. 2019;20(1):171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Günay E, Sarınç Ulaşlı S, Akar O, et al. Neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective study. Inflammation. 2014;37(2):374‐380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Liu Y, Du X, Chen J, et al. Neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio as an independent risk factor for mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Infect. 2020;81(1):e6–e12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lippi G, Henry BM, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Respir Med. 2020;167:105941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Team. TNCPERE . The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID‐19) —.China, 2020. China CDC Weekly. 2020;2:113–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Zhang J‐J, Dong X, Cao Y‐Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020;75(7):1730–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Team CC‐R . Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 — United States, February 12–March 28, 2020. In: 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96. Halpin DMG, Faner R, Sibila O, Badia JR, Agusti A. Do chronic respiratory diseases or their treatment affect the risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):436–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Stockman LJ, Bellamy R, Garner P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3(9):343e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Singanayagam A, Glanville N, Girkin JL, et al. Corticosteroid suppression of antiviral immunity increases bacterial loads and mucus production in COPD exacerbations. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Hui DS, Joynt GM, Wong KT, et al. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) on pulmonary function, functional capacity and quality of life in a cohort of survivors. Thorax. 2005;60(5):401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. von der Thüsen J, Eerden M. Histopathology and genetic susceptibility in COVID‐19 pneumonia. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;50(7): e13259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]