Abstract

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness of oral versus intramuscular (IM) vitamin B12 (VB12) in patients aged ≥65 years with VB12 deficiency.

Design

Pragmatic, randomised, non-inferiority, multicentre trial in 22 primary healthcare centres in Madrid (Spain).

Participants

283 patients ≥65 years with VB12 deficiency were randomly assigned to oral (n=140) or IM (n=143) treatment arm.

Interventions

The IM arm received 1 mg VB12 on alternate days in weeks 1–2, 1 mg/week in weeks 3–8 and 1 mg/month in weeks 9–52. The oral arm received 1 mg/day in weeks 1–8 and 1 mg/week in weeks 9–52.

Main outcomes

Serum VB12 concentration normalisation (≥211 pg/mL) at 8, 26 and 52 weeks. Non-inferiority would be declared if the difference between arms is 10% or less. Secondary outcomes included symptoms, adverse events, adherence to treatment, quality of life, patient preferences and satisfaction.

Results

The follow-up period (52 weeks) was completed by 229 patients (80.9%). At week 8, the percentage of patients in each arm who achieved normal B12 levels was well above 90%; the differences in this percentage between the oral and IM arm were −0.7% (133 out of 135 vs 129 out of 130; 95% CI: −3.2 to 1.8; p>0.999) by per-protocol (PPT) analysis and 4.8% (133 out of 140 vs 129 out of 143; 95% CI: −1.3 to 10.9; p=0.124) by intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. At week 52, the percentage of patients who achieved normal B12 levels was 73.6% in the oral arm and 80.4% in the IM arm; these differences were −6.3% (103 out of 112 vs 115 out of 117; 95% CI: −11.9 to −0.1; p=0.025) and −6.8% (103 out of 140 vs 115 out of 143; 95% CI: −16.6 to 2.9; p=0.171), respectively. Factors affecting the success rate at week 52 were age, OR=0.95 (95% CI: 0.91 to 0.99) and having reached VB12 levels ≥281 pg/mL at week 8, OR=8.1 (95% CI: 2.4 to 27.3). Under a Bayesian framework, non-inferiority probabilities (Δ>−10%) at week 52 were 0.036 (PPT) and 0.060 (ITT). Quality of life and adverse effects were comparable across groups. 83.4% of patients preferred the oral route.

Conclusions

Oral administration was no less effective than IM administration at 8 weeks. Although differences were found between administration routes at week 52, the probability that the differences were below the non-inferiority threshold was very low.

Trial registration numbers

NCT 01476007; EUDRACT (2010-024129-20).

Keywords: vitamin B 12 deficiency; administration oral; equivalence trial,; injections intramuscular; primary health care; patient preference

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the largest and longest follow-up randomised clinical trial in patients aged ≥65 years with VB12 deficiency.

In addition to VB12 levels, this study incorporates patient-reported outcomes such as symptoms, quality of life and patient preferences.

The study design did not allow patient blinding; however, the main outcome measurement was objective.

The rates of loss to follow-up were low at week 8 and week 26 and higher at week 52, consistent with pragmatically designed clinical trials.

Introduction

Vitamin B12 (VB12) is an essential nutrient for the synthesis of cellular DNA. It is generally accepted that daily needs in adults range from 1 to 2 µg/day,1 but other standards recently recommend 3–4 µg/day.2 The Western diet is estimated to contain 7–30 µg/day of cobalamin, of which 1–5 µg is absorbed and stored (estimated reserves of 2–5 mg); therefore, symptoms resulting from a VB12 deficit would not appear until 3–5 years after establishing a low-ingestion or poor-absorption regimen.1 VB12 deficiency can lead to haematological and neuropsychiatric disorders,3 as well as cardiovascular risk factors.4 The prevalence of VB12 deficiency in the elderly is highly variable across studies, which report values of 1.5%–15%.5–8

In primary care, the most commonly observed causes of VB12 deficiency are related to abnormalities in digestion (atrophic gastritis, achlorhydria) or absorption (autoimmune pernicious anaemia, chronic pancreatitis, Crohn’s disease, the effect of medications that alter the mucosa of the ileum such as metformin, antacids -proton-pump inhibitors and H2-receptor antagonists, antibiotics and colchicine)9 or the consequences of surgical resection.10 A deficiency stemming solely from dietary habits is rare and usually affects strict vegans.11 In the elderly, different alterations in the processes involved in VB12 absorption increase the prevalence of this deficit, which can appear in the absence of specific symptoms, thereby hindering its diagnosis.12

The traditional treatment for VB12 deficiency consists of intramuscular (IM) injection of cyanocobalamin, generally 1 mg/day for 1 week, followed by 1 mg/week for 1 month and then 1 mg every 1 or 2 months ad perpetuum.10 13 14 The vitamin may, however, be administered orally. Several studies have shown serum VB12 concentrations to normalise after taking large oral doses.15 16 Studies taking into consideration the patients’ preferences have found differences in favour of the oral route.17 18 Furthermore, oral treatment could avoid injection nuisances, reduce unnecessary travel for the patients or nurses and minimise treatment costs.19

Some authors have questioned the use of oral administration while others favour it, although no firm conclusions can be drawn due to the methodological limitations of the evidence the authors provide.10 20–22 The 2018 Cochrane Review5 includes three randomised clinical trials comparing the effectiveness of oral and IM administration. There are differences among the trials in terms of treatment regimens and follow-up duration, ranging from 3 to 4 months, and average age of the patients, as well as the frequency and VB12 daily dose for both routes. In terms of outcomes, adverse events and cost, the overall quality of the evidence was low due to the small number of studies and limited sample sizes.23–25 In their conclusions, the authors state the need for trials with improved methods for random allocation and masking, larger sample sizes and information on other relevant outcome variables that are preferably conducted in the primary care setting.

The aim of this study was to compare the effectiveness of oral-administered and IM-administered VB12 in the normalisation of serum VB12 concentrations at 8, 26 and 52 weeks in patients aged ≥65 years with VB12 deficiency treated at primary healthcare centres (PHC). Secondary outcomes included safety (adverse events), quality of life and adherence to treatment. Additional aims were to describe patient preferences and satisfaction with treatment and to explore the immediate response (8 weeks) as a normalisation predictor of 1 year outcomes to propose clinical recommendations.

Methods

Study design and participants

A pragmatic, randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority clinical trial with a duration of 12 months was conducted in a PHC. On ethical grounds, a placebo-controlled trial was not appropriate.26 Methodological issues of this trial have been published elsewhere (online supplementary 1).27

bmjopen-2019-033687supp001.pdf (242.5KB, pdf)

Competitive recruitment was performed in 22 PHC in Madrid (Spain) from July 2014 to November 2016. Eligible patients were 65 years of age or older and had been attending a PHC for consultation on any medical matter. Patients were assessed for eligibility and invited to participate consecutively by their general practitioners. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. A blood test was performed, and in patients with a serum concentration of VB12 of <211 pg/mL, the remaining inclusion and exclusion criteria were evaluated. The cut-off value selected in the trial register/trial protocol was <179 pg/mL; this value was modified by the laboratory following the recommendations of the provider. This change took place prior to the beginning of the recruitment. Patient recruitment was always performed using the same methodology and cut-off point. The procedures for measurement of the biomarkers were ADVIA Centaur XP (Siemens Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY, USA).

Randomisation and masking

Patients were allocated by simple randomisation at a 1:1 ratio to oral or IM administration of VB12. The randomisation system was incorporated into the electronic data collection system to assure allocation concealment. Because of the nature of the intervention, patients and general practitioners were aware of their treatment allocation. Analysis was performed by the trial statistician, who was blinded to allocation.

Intervention

The pharmaceutical formulations used in the study are commercially available in Spain (Optovite vials). Its pharmaceutical presentation is in silk-screen-printed clear glass ampoules that are presented in blister support. The treatment regimen was : (a) IM route: 1 mg of cyanocobalamin on alternate days during weeks 1–2, 1 mg/week during weeks 3–8 and 1 mg/month during weeks 9–52; (b) oral route: 1 mg/day of cyanocobalamin for 8 weeks and 1 mg/week during weeks 9–52. The period between 1 and 8 weeks was considered the charging period.

In the oral route, the medication was provided to the patient at the health centre, along with instructions for self-administration at home. The information sheet explained to the patient the procedure for oral administration, that is, how to open the ampoule and dilute its contents in a glass, then drink it.

In the IM route, the medication was administered by the nurse at the health centre.

Outcomes

The main outcome was the normalisation of serum VB12 concentrations (≥211 pg/mL) at 8, 26 and 52 weeks. The secondary outcomes were the serum VB12 concentrations (pg/mL), adverse events, adherence to treatment (number of vials for the oral arm and the number of injections for the IM arm during each visit; good adherence was considered greater than 80%), quality of life (EQ-5D-5L)28 and patient preferences and satisfaction were assessed. Anamnesis, demographic and lifestyle information, clinical variables, analytical variables and concomitant treatment were recorded.27

Procedures

After signing the consent form, those who agreed to participate had serum VB12 concentrations determined. If the VB12 value was <211 pg/mL, a haemogram, biochemical analysis and anti-intrinsic factor antibody levels were assessed.27 The patients also received a medication diary to be filled out daily. Baseline data were collected by the family physician and/or a nurse. IM treatments were administered by nurses in the health centres. The follow-up visits were conducted during weeks 8, 26 and 52.27

Statistical analysis

Sample size

Assuming that 70% of patients reach a serum VB12 concentration of ≥211 pg/mL in both groups, for a threshold of non-inferiority of 10%, statistical power of 60% with significance set at p<0.05 and a 5% loss to follow-up, the final sample size was word 320 (160 in each arm).

As recommended for non-inferiority studies, both per-protocol (PPT) and intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses were performed, with the null hypothesis being that there were differences between treatments at the three monitoring points. Comparing both arms, we calculated the difference between the percentage of patients in each treatment arm whose serum VB12 concentrations became normalised at 8, 26 and 52 weeks, with their 95% CI. If the CIs do not fall outside the non-inferiority limit (10%), it can be concluded that the oral treatment is not inferior to the IM treatment.29 30 In ITT analyses, missing values for the main outcome variable were added using the ‘last observation carried forward’ method.31

To explore factors affecting the normalisation of serum VB12 concentration at 52 weeks, serum VB12 levels were studied at 8 weeks. A receiver operating characteristic curve was built to determine the likelihood ratios of each cutpoint after the charging period to ‘predict’ the normalisation of levels at the end of the study. After this, a generalised linear model was built (function logit).32 33 The normalisation of serum VB12 levels at 52 weeks was the dependent variable, and the treatment group was the independent variable. Variables considered significant by the researchers from a clinical perspective were included in the model. To test the non-inferiority hypothesis, adding the information contained in these data to previous knowledge, additional statistical analyses were performed using a Bayesian approach. Secondary outcome variables were analysed using the appropriate statistical tests, and their means or proportions were used to estimate differences between groups. All analyses were performed using STATA V.14 and EPIDAT V.4.2 software.

Patient involvement

Patients were not involved in the development of plans for recruitment, design, outcome measures or implementation of the study conduct. No patients were asked to advise on the interpretation or writing of the results. Patients explained the experience of participating in the study on the occasion of International Clinical Trial’s day in Radio Nacional de España. We will pursue patient and public involvement in the development of an appropriate method for further dissemination.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

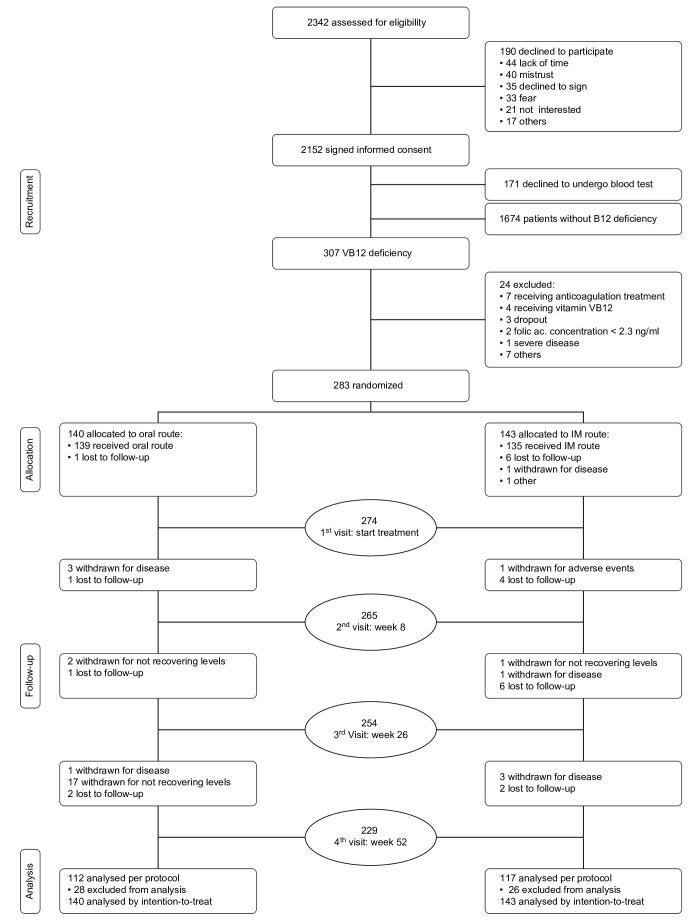

A total of 2342 patients were offered participation, and 2152 provided informed consent. A total of 307 patients showed a VB12 deficit (14.3%), 283 of whom were allocated to receive VB12 treatment via the IM route (n=143) or orally (n=140). The follow-up period (52 weeks) was completed by 229 patients (80.9%). Losses to follow-up were similar in both regimens, 28 out of 140 and 26 out of 143 losses in the oral and IM arms, respectively (p=0.697) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trial profile.

The average age was 75.2 (6.34), and 58.3% of the patients were women. Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the patients included in the trial. No relevant differences were found between groups at baseline for demographic and medical characteristics or for the study endpoints.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at baseline by group

| Variable | No (%) | ||

| Oral route (n=140) | IM route (n=143) | Total (n=283) | |

| Sociodemographic data | |||

| Women | 87 (62.1) | 78 (54.5) | 165 (58.3) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 74.2 (5.8) | 76.2 (6.7) | 75.2 (6.3) |

| Educational level | |||

| Illiteracy | 4 (2.9) | 7 (5.1) | 11 (4.0) |

| Incomplete education | 48 (34.5) | 46 (33.6) | 94 (34.1) |

| Primary education | 58 (41.7) | 63 (46.0) | 121 (43.8) |

| Secondary education | 16 (11.5) | 10 (7.3) | 26 (9.4) |

| Tertiary education | 4 (2.9) | 4 (2.9) | 8 (2.9) |

| Higher education | 9 (6.5) | 7 (5.1) | 16 (5.8) |

| Social occupational class* | |||

| Classes I–IV | 31 (27.7) | 33 (27.3) | 64 (27.5) |

| Classes V–VI | 81 (72.3) | 88 (72.7) | 169 (72.5) |

| Living alone | 32 (21.4) | 30 (22.2) | 62 (21.9) |

| Clinical data | |||

| Tobacco habit | |||

| Ex-smoker | 27 (19.7) | 25 (18.4) | 52 (19.0) |

| Smoker | 9 (6.6) | 10 (7.4) | 19 (7.0) |

| Non-smoker | 101 (73.7) | 101 (74.3) | 202 (74.0) |

| Vegetarian | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Having undergone gastrectomy | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| Symptoms | |||

| Paresthesia | 33 (23.6) | 45 (31.5) | 78 (27.6) |

| Asthenia | 43 (30.7) | 54 (37.8) | 97 (34.3) |

| Loss of appetite | 12 (8.6) | 30 (21.0) | 42 (14.8) |

| Sadness | 37 (26.4) | 53 (37.1) | 90 (31.8) |

| Showing ≥1 symptom | 70 (50.0) | 83 (58.0) | 153 (54.1) |

| Signs | |||

| Glossitis | 2 (1.4) | 9 (6.3) | 11 (3.9) |

| Position sensitivity | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (1.1) |

| Vibration sensitivity | 15 (10.7) | 13 (9.1) | 28 (9.9) |

| Showing ≥1 altered sign | 16 (11.4) | 21 (14.7) | 37 (13.1) |

| Haemogram-clinical biochemistry | |||

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL), mean (SD) | 173.1 (27.3) | 166.4 (32.6) | 169.7 (30.2) |

| Anaemia† | 16 (11.4) | 27 (18.9) | 43 (15.2) |

| Haematocrit (%), mean (SD) | 42.4 (4.0) | 41.9 (4.2) | 42.1 (4.1) |

| MCV (fL), mean (SD) | 92.1 (6.7) | 94.3 (7.4) | 93.2 (7.1) |

| Anti-intrinsic factor antibody | 15 (11.0) | 15 (10.5) | 30 (10.8) |

| Medication | |||

| Proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) | 57 (40.7) | 64 (44.8) | 121 (42.8) |

| Metformin | 69 (49.3) | 56 (39.2) | 125 (44.2) |

| PPI and metformin | 33 (23.6) | 30 (21.0) | 63 (22.3) |

| Scales | |||

| MMSE‡, mean (SD) | 30.8 (4.6) | 30.2 (4.8) | 30.5 (4.7) |

| EQ-5D-utilities, mean (SD) | 0.817 (0.169) | 0.855 (0.139) | 0.836 (0.171) |

*Neoweberian occupational social class (CSO-SEE12).41

†Anaemia was defined by the WHO criteria (haemoglobin <12 g/L in women and <13 g/L in men). https://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin.

‡Maximum score=35 points. Normal score=30–35. Borderline score=24–29 points. Scores <24 points in patients aged >65 years and scores <29 points in patients aged <65 years suggest cognitive impairment.

IM, intramuscular; MCV, Mean Corpuscular Volume; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination.

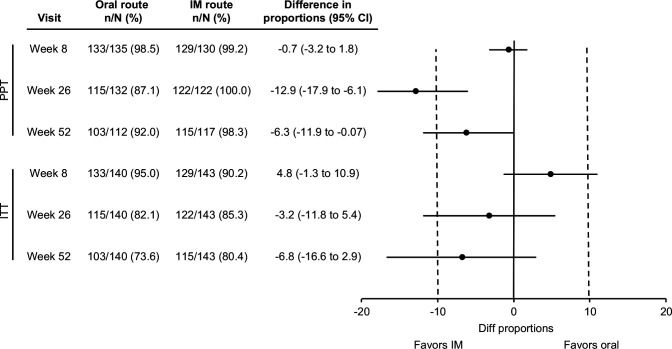

Primary outcomes

At week 8, the difference in the success rate between the oral and IM routes was −0.7% (95% CI: −3.2% to 1.8%; p=0.0999) and 4.8% (95% CI: −1.3% to 10.9%; p=0.124) with the PPT and ITT analyses, respectively. At week 26, these differences were −12.9% (95% CI: −17.9% to −6.1%; p<0.001) and −3.2% (95% CI: −11.8% to 5.4%; p=0.470), respectively. At week 52, these differences were −6.3% (95% CI: −11.9% to −0.07%; p=0.025) and −6.8% (95% CI: −16.6% to 2.9%; p=0.171), respectively (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Difference between the oral and intramuscular routes in the proportion of patients whose VB12 levels returned to normal (≥211 pg/mL). IM, intramuscular; ITT, intention-to-treat; PPT, per-protocol.

In the PPT analysis under a Bayesian approach, the probabilities of differences in the treatment effectiveness being >10% between the oral and IM groups were 0.001, 0.201 and 0.036 at weeks 8, 26 and 52, respectively. In the ITT analysis, these values were 0.000, 0.015 and 0.060 at weeks 8, 26 and 52, respectively (online supplementary 2). The result of the likelihood ratio for the cutpoints at the main percentiles of the distribution of VB12 serum levels at week 8 to predict normalisation at the end of the study is shown in online supplementary 3. The level at the fifth percentile of the distribution was selected as the most useful value because it showed the best classification ability. When patients did not reach this level at week 8, they were almost 12 times more likely to not reach suitable VB12 levels at the end of the study than if they had reached levels over 281 pg/mL (12~1/negative likelihood ratio).

bmjopen-2019-033687supp002.pdf (143KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033687supp003.pdf (169.4KB, pdf)

In the ITT analysis, the factors affecting the success rate at week 52 were age, for each year of increase in age, the success rate decreased by 5%, and having attained VB12 levels of ≥281 pg/mL at week 8, which yielded a success rate 8.1 times higher (table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with VB12 concentrations ≥211 pg/mL at week 52

| Variable | OR | Robust SE | P>z | 95% CI |

| IM vs oral route | 1.10 | 0.370 | 0.776 | 0.57 to 2.13 |

| Age | 0.95 | 0.022 | 0.025 | 0.91 to 0.99 |

| VB12 concentration >281 pg/mL at week 8 | 8.10 | 5.014 | 0.001 | 2.41 to 27.25 |

| Constant | 0.78 | 0.622 | 0.755 | 0.16 to 3.72 |

GLM, N=265. Variance function: V(u) = u*(1−u/1) [Binomial]. Link function: g(u) = ln(u/(1−u)) [Logit]. Akaike Information Criterion= 0.89967. Bayesian Information Criterion= −1225.89.

The mean levels of VB12 for each follow-up visit were above the normalisation threshold in both groups, although these values were much greater in the IM group (online supplementary 4). In 51 patients (46 IM and 5 oral), the levels of VB12 in week 8 were above the normal range limit of the laboratory (≥911 pg/mL), so the treatment regimen was changed from the initial planned pattern.

bmjopen-2019-033687supp004.pdf (83.6KB, pdf)

Secondary outcomes

In terms of quality of life and the presence of signs related to VB12 deficiency, no significant differences were found between treatment arms at any of the follow-up visits (table 3).

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes (quality of life and exploratory findings) at weeks 8, 26 and 52

| Visit | Oral route | IM route | P value | Mean difference (95% CI) | ||

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | |||

| Quality of life (EQ-5D-5L Index) | ||||||

| Baseline | 139 | 0.855 (0.139) | 137 | 0.817 (0.197) | 0.066 | 0.038 (−0.002 to 0.078) |

| Week 8 | 134 | 0.853 (0.158) | 130 | 0.822 (0.204) | 0.173 | 0.031 (−0.013 to 0.075) |

| Week 26 | 128 | 0.853 (0.153) | 122 | 0.826 (0.191) | 0.219 | 0.027 (−0.016 to 0.070) |

| Week 52 | 112 | 0.824 (0.179) | 117 | 0.823 (0.194) | 0.958 | 0.001 (−0.047 to 0.049) |

GLM, generalised linear model; IM, intramuscular.

| At least one altered sign (glossitis and/or altered vibration sensitivity and/or altered position sensitivity) | ||||||

| Visit | N | n (%) | N | n (%) | P value | Proportion difference (95% CI) |

| Baseline | 140 | 16 (11.4) | 143 | 21 (14.7) | 0.416 | −3.3 (−11.1 to 4.6) |

| Week 8 | 135 | 15 (11.1) | 130 | 13 (10.0) | 0.769 | 1.1 (−6.3 to 8.5) |

| Week 26 | 131 | 14 (10.7) | 122 | 12 (9.8) | 0.824 | 0.9 (−6.6 to 8.3) |

| Week 52 | 122 | 14 (12.5) | 117 | 9 (7.7) | 0.226 | 3.8 (−3.7 to 11.2) |

Eleven adverse events were reported and none of them were severe; five (3.57%) occurred with patients in the oral arm and six (4.20%) with patients in the IM arm, yielding a difference of −0.63% (95% CI: −5.12% to 3.87%, p=0.786). Three patients withdrew from the study: one patient in the oral group due to urticaria, and two in the IM group due to reddening and pruritic facial erythema and generalised itching (mainly in the cheeks with scarce urticariform lesions). In three other cases, treatment for the adverse events was prescribed (constipation and erythema), and in five cases, it was not necessary to take further measures (table 4).

Table 4.

Description of adverse events by patient and route of administration

| Route | Adverse event | Action |

| IM route | Constipation | Administration of specific treatment |

| Generalised itching and hives on the cheeks | Withdrawal | |

| Dyspepsia | Treatment not required | |

| Constipation | Administration of specific treatment | |

| Redness and pruritic facial erythema | Withdrawal | |

| Erythema on forearms | Administration of specific treatment | |

| Oral route | Urticaria on the neck and arms | Treatment not required |

| Occasional postprandial dyspepsia | Treatment not required | |

| Occasional postprandial dyspepsia | Treatment not required | |

| Urticaria | Withdrawal | |

| Increased irritability and nervousness | Treatment not required |

IM, intramuscular.

At week 8, adherence to treatment was evaluated in 265 patients, of whom 95.5% were adherent (97.8% oral and 93.8% IM); the difference between the groups was 4% (95% CI: −0. 1% to 8.7%; p=0.109). At week 52, adherence was evaluated in 229 patients, of whom 220 (96.1%) were adherent (98.2% oral and 94.0% IM); the difference was 4.2% (95%CI: −0.7% to 9.1%; p=0.172).

Overall, 89.5% of the patients reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the treatment via the oral route (91.3%) and the IM route (87.6%). The difference was 3.7% (95% CI: −4.0% to 11.3%; p=0.348).

A total of 83.4% of patients preferred the oral route (97.6% among the patients receiving VB12 orally vs 68.6% of the patients in the IM group); the difference was 29.0% (95% CI: 20.3 to 37.7; p<0.001). The preferences expressed by the patients referred to their potential choice regardless of the arm to which they were assigned.

Discussion

Main findings of the study

Supplementing VB12 in patients with VB12 deficiency, whether orally or intramuscularly, achieves the normalisation of VB12 levels in most cases. The oral route was not inferior to the IM route during the charging period. Formally, the pre-established conditions for determining the non-inferiority of oral administration were not met for the complete follow-up period, but these results merit a deeper analysis.

Differences between the administration routes were found at 26 and 52 weeks. The IM maintenance treatment of 1 mg/month was effective in maintaining VB12 levels, while oral administration of 1 mg/week had a probability of being inferior (by more than 10%) to the IM route by 20% in the most unfavourable scenario (PPT). However, given that no strategy was superior in the charging period, and in view of the model results showing that when VB12 levels reached ≥281 pg/mL during the charging period, the success rate at 12 months was eight times higher, the probability that the differences between groups would exceed Δ was very low, independent of the administration route. The most plausible explanation for the observed difference between routes might be that in patients below this threshold, the maintenance oral dose should be higher than the dose used in the present study. Some authors have recommended that an oral dose of 2 mg/week be administered as a maintenance dose.34

The incidence of adverse events was very low and similar for oral and IM administration, and non-serious adverse events were found. These findings were similar to other studies.5 Patients’ preferences can be a decisive factor for determining the administration route. In this trial, similar to previous studies,17 there was a clear preference for the oral route, especially among the patients assigned to this group.

The effect of VB12 supplements on quality of life remains unclear,35 36 but the present results show that the treatment route does not improve patients’ perception of their health-related quality of life or related symptoms.

We did not find significant differences in adherence. Adherence to the treatment via the IM route was lower than expected. Although drug administration was assured once the patient attended the consultation, the patient could choose not to attend appointments for various reasons. However, in usual practice, adherence with the oral route could be more compromised than with the IM route, and this factor should be taken into consideration to personalise prescription.

Comparison with other studies

The comparison with other studies is difficult, due to the treatment different doses used, but especially because of the follow-up length had been inferior to 4 months and the number of patients included was small.

As far as we know, the present trial is the largest clinical trial with the longest follow-up period, and it is the first to evaluate, in addition to VB12 levels, clinical signs and symptoms, health-related quality of life and patient preferences. The three clinical trials23–25 described in the 2018 Cochrane Systematic Review5 had a duration between 3 and 4 months and included a total of 153 patients. In the Saraswathy trial, patients in the oral route at 3 months normalised levels 20/30 (66.7%) versus 27/30 (90%) of the patients in the IM route.25 In Kuzminski’s trial, patients in the oral route at 4 months normalised levels 18/18 (100%) versus 10/14 (71.4%) of the patients in the IM route.23 These differences were statistically non-significant in both studies.

Two studies have recently been published and add evidence in favour of oral and sublingual administration of VB12.37 38 The follow-up of Moleiro’s study reached 24 months versus 12 months in our study. However, Moleiro et al performed a prospective uncontrolled study that included 26 patients submitted to total gastrectomy. All patients received oral VB12 supplementation (1 mg/day), and all of them maintained normalisation V12 at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months. There was a progressive increase in serum V12 levels within the first 12 months, which remained stable thereafter.37 The long-term effectiveness of the oral route in absorption-deficient people such as gastrectomised patients would support the results of our study.

Bensky et al compared the efficacy of sublingual versus IM administration of VB12 in a retrospective observational study from the computerised pharmacy records of Maccabi Health Service. Among 4281 patients treated with VB12 supplements (830 (19.3%) with IM and 3451 (80.7%) with sublingual tablets), the IM group achieved a significant increase in VB12 levels compared with the sublingual group, OR 1.85, CI 95% 1.5 to 2.3.38 Although this study has a large sample size, the important methodological limitations on its effectiveness (retrospective design; reliance on clinical records; absence of epidemiological information such as patient age and sex or the aetiology of the deficit) should be considered in the interpretation of their results.

Strengths and limitations

Our study was pragmatic39 in both the inclusion and diagnostic methods criteria. The majority of the patients with deficits included in this study presented no symptomatology or very low-level symptoms, with no anaemia, which is the common profile of most patients who present with VB12 deficits in primary care. The study design did not allow for masking the patients to the received treatment. However, these limitations were compensated for by the objective measurement of the main outcome variable.

As occurs in all pragmatic clinical trials, patient recruitment was complicated, and the sample size reached only 88.4% of the calculated necessary size, which implies that the power of the study was limited. Hence, the analysis was complemented using Bayesian methods that allow for studying a posteriori the likelihood of a difference between two outcomes to exceed a certain limit.40 Under this approach, the a posteriori probability for differences to exceed the proposed Δ=−10% was not significant during the charging period, and the probabilities were low but not negligible in the PPT analysis and low in the ITT analysis over the complete follow-up period.

Loss to follow-up was low at 8 and 26 weeks and higher at 52 weeks. This effect has been observed in pragmatic clinical trials with long follow-up periods. Missing data were greater in the IM arm, during the interval between randomisation and initiation of treatment (6% IM vs 1% oral), over 8 weeks (9% IM vs 4% oral) and over 26 weeks (15% IM vs 6% oral). These differences could represent a lower acceptability of the IM route by patients, since the missing data were mostly due to patient dropout. At 52 weeks, the numbers of losses in the two arms were similar (20% oral and 18% IM), and in the case of oral treatment, several of those losses were withdrawals occasioned by not achieving particular levels of VB12.

Implications of the study findings

On the basis of our results and the available evidence, we propose the oral administration of VB12 at 1 mg/day during the charging period. Subsequently, the recommended dose would vary as a function of the VB12 levels reached during the charging period. For VB12 concentrations between the normal levels of 211 pg/mL (in our laboratory) and 281 pg/mL (the fifth percentile of the distribution in this trial), a dose of 2 mg/week is suggested. When the levels reached in the charging period are between 281 and 380 pg/mL (the 20th percentile of the distribution), it may be appropriate to perform an analysis between 8 and 26 weeks to confirm that normal levels are maintained. All patients who reach a level of 380 pg/mL by week 8 could be maintained at the initial dosage (1 mg/week) without subsequent analyses during the year of follow-up.

If the IM route is chosen, the proposed dose for this route during the first few weeks may be excessive for patients with VB12 deficiency. The scheduled IM dose should be reconsidered in the first 2 weeks based on VB12 levels, and the scheduled dose could be limited to 1 mg/week if warranted by the outcome. Nevertheless, these recommendations must be assessed in further research.

Oral administration of VB12 in patients older than 65 years is probably as effective as IM administration, and it also lacks adverse effects and is preferred by patients. We must also highlight the potential benefit of the oral route in terms of safety for patients with coagulation problems, for whom IM-administered medication is often contraindicated. A small number of patients may require additional follow-up after 8 weeks if a certain concentration of VB12 in blood is not reached.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

To Margarita Blázquez Herranz, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, for making the impossible possible. To Juan Carlos Abánades Herranz for trusting us and his contribution to facilitate our work. To Antonio Jesús Alemany López and Marta Sánchez-Celaya, Managing Director of Primary Healthcare for accepting to sponsor this research after the dissolution of CAIBER. To the Fundación para la Investigación e Innovación Biomédica de Atención Primaria (FIIBAP) for the grant awarded for the publishing of the research. To Fernando Cava Valencia and Raquel Guillén Santos from the Clinical Laboratory BRSALUD. To Elena Tolosa Oropesa from the Pharmacy Department, Gerencia Asistencial de Atención Primaria de Madrid. To our colleagues from the Research Unit, including the assistants Marcial Caboblanco Muñoz, Juan Carlos Gil and Isabel Morales Ropero for their unconditional support; project manager Pilar Pamplona-Gardeta, researchers Juan A. López Rodríguez, Jaime Barrio Cortes, Cristina Lozano Hernandez and Medical Residents Daniel Toledo Bartolomé, Irene Wijers and Palmira Jurado Macías for their technical advice in finalising this paper. To Javier Zamora Romero, head of the Unit of Biostatistics, Hospital Ramón y Cajal of Madrid, for revising the manuscript. To all the professionals from the participating healthcare centres. To all patients who contributed to this research.

Footnotes

Deceased: Esperanza Escortell-Mayor passed away before the submission of the final version of this manuscript

Collaborators: OB12 group collaborators: Clinical investigators: Healthcare Centre (HC) Guayaba: Isabel Gutiérrez-Sánchez; Ángeles Fernández-Abad; José Antonio Granados-Garrido; Javier Martínez-Suberviola; Margarita Beltejar-Rodríguez; Carmen Coello-Alarcón; Susana Diez-Arjona. HC El Greco: Ana Ballarín-González; Ignacio Iscar-Valenzuela; José Luis Quintana-Gómez; José Antonio González-Posada-Delgado; Enrique Revilla-Pascual; Esther Gómez-Suarez; Yolanda Fernández-Fernández; Fernanda Morales-Ortiz; Isabel Ferrer-Zapata; Esperanza Duralde-Rodríguez; Milagros Beamud-Lagos. HC Barajas: Mª del Pilar Serrano-Simarro; Cristina Montero-García; María Domínguez-Paniagua; Sofía Causín-Serrano; Josefa San Vicente-Rodríguez; Germán Reviriego-Jaén; Margarita Camarero-Shelly; Rosa Gómez-del-Forcallo. HC Cuzco: María Ángeles Miguel-Abanto; Lourdes Reyes-Martínez; Alejandro Rabanal-Basalo; Carolina Torrijos-Bravo; Pilar Gutiérrez-Valentín; Jorge Gómez-Ciriano; Susana Parra Román; Judit León-González; Mª José Nebril-Manzaneque; Juana Caro-Berzal. HC Mendiguchía Carriche: Alberto López-García-Franco; Sonia Redondo-de-Pedro; Juan Carlos García-Álvarez; Elisa Viñuela-Beneitez; Marisa López-Martín; Nuria Sanz-López. HC Buenos Aires: Ana María Ibarra-Sánchez; Cecilio Gómez-Almodóvar; Javier Muñoz-Gutiérrez; Carmen Molins-Santos; Cristina Cassinello-Espinosa. HC Presentación Sabio: Antonio Molina-Siguero*; Rafael Sáez-Jiménez; Paloma Rodríguez-Almagro; Eva María Rey-Camacho; María Carmen Pérez-García. HC Santa Isabel: Antonio Redondo-Horcajo; Beatriz Pajuelo-Márquez; Encarnación Cidoncha-Calderón; Jesús Galindo Rubio; Rosa Ana Escriva Ferrairo; José Francisco Ávila-Tomas; Francisco De-Alba-Gómez; Mª Jesús Gómez-Martín; Alma María Fernández-Martínez. HC Fuentelarreina: Rosa Feijoó-Fernández; José Vizcaíno-Sánchez-Rodrigo; Victoria Díaz-Puente; Felisa Núñez-Sáez; Luisa Asensio-Ruiz; Agustín Sánchez-Sánchez; Orlando Enríquez-Dueñas; Silvia Fidel-Jaimez; Rafael Ruiz-Morote-Aragón; Asunción Pacheco-Pascua; Belén Soriano-Hernández; Eva Álvarez-Carranza; Carmen Siguero-Pérez. HC Juncal: Ana Morán-Escudero; María Martín-Martín; Francisco Vivas-Rubio. HC Miguel de Cervantes: Rafael Pérez-Quero; Mª Isabel Manzano-Martín; César Redondo-Luciáñez. HC San Martín de Valdeiglesias: Nuria Tomás-García*; Carlos Díaz-Gómez-Calcerrada; Julia Isabel Mogollo-García; Inés Melero-Redondo; Ricardo González-Gascón. HC Lavapiés: María Carmen Álvarez-Orviz; María Veredas González-Márquez; Teresa San Clemente-Pastor; Amparo Corral-Rubio. HC General Ricardos: Asunción Prieto-Orzanco*; Cristina de la Cámara-Gonzalez; Mercedes Parrilla-Laso; Mercedes Canellas-Manrique; Maria Eloisa Rogero-Blanco; Paulino Cubero-González; Sara Sanchez-Barreiro;

Mª Ángeles Aragoneses-Cañas; Ángela Auñón-Muelas; Olga Álvarez-Montes. HC María Jesús Hereza: Petra María Cortes-Duran; Pilar Tardaguila-Lobato; Mar Escobar-Gallegos; Antonia Pérez-de-Colosia-Zuil; Jaime Inneraraty-Martínez; María Jesús Bedoya-Frutos; María Teresa López-López; Nelly Álvarez-Fernández; Teresa Fontova-Cemeli; Josefa Marruedo-Mateo; Josefa Díaz-Serrano; Beatriz Pérez-Vallejo. HC Reyes Magos: Pilar Hombrados-Gonzalo*; Marta Quintanilla-Santamaría; Yolanda González-Pascual; Luisa María Andrés-Arreaza; Soledad Escolar-Llamazares; Cristina Casado-Rodríguez; Luz del Rey-Moya; Jesús Fernández-Valderrama; Alejandro Medrán-López; Julia Alonso-Arcas. HC Barrio del Pilar: Alejandra Rabanal-Carrera*; Araceli Garrido-Barral; Milagros Velázquez-García; Azucena Sáez-Berlanga; Pilar Pérez-Egea; Rosario del Álamo-Gutiérrez; Pablo Astorga-Díaz; Carlos Casanova-García; Ana Isabel Román-Ruiz; Carmen Belinchón-Moya; Margarita Encinas-Sotillo; Virtudes Enguita-Pérez. HC Los Yébenes: Ester Valdés-Cruz*; Consuelo Mayoral-López; Alejandro Rabanal-Basalo; Teresa Gijón-Seco; Francisca Martínez-Vallejo; Jesica Colorado-Valera. HC María Ángeles López Gómez: Ana Sosa-Alonso*; Jeannet Sánchez-Yépez*; Dolores Serrano-González; Beatriz López-Serrano; Inmaculada Santamaría-López; Paloma Morso-Peláez; Carolina López-Olmeda; Almudena García-Uceda-Sevilla; Mercedes del Pilar Fernández-Girón. HC Arroyo de la Media Legua: Leonor González-Galán*; Mariano Rivera-Moreno; Luis Nistal Martín-de-Serranos; Mª Jesús López-Barroso; Margarita Torres-Parras; María Verdugo-Rosado; Mª Reyes Delgado-Pulpón; Elena Alcalá-Llorente. HC Federica Montseny: Sonsoles Muñoz-Moreno*; Isabel Vaquero-Turiño; Ana María Sánchez-Sempere; Francisco Javier Martínez-Sanz; Clementa Sanz-Sanchez; Ana María Arias-Esteso. HC Calesas: Diego Martín-Acicoya*; Pilar Kloppe-Villegas; Francisco Javier San-Andrés-Rebollo; Magdalena Canals-Aracil; Isabel García-Amor; Nieves Calvo-Arrabal; María Milagros Jimeno-Galán. HC Manuel Merino: Gloria de la Sierra-Ocaña*; María Mercedes Araujo-Calvo. HC Doctor Cirajas: Julia Timoner-Aguilera*; María Santos Santander-Gutiérrez; Alicia Mateo-Madurga. Technical Support Group**- Research Unit: Ricardo Rodríguez-Barrientos; Milagros Rico-Blázquez; Juan Carlos Gil-Moreno; Mariel Morey-Montalvo. Amaya Azcoaga Lorenzo. Multiprofessional Teaching Units of Primary and Community Care: Gloria Ariza-Cardiel; Elena Polentinos-Castro; Sonia Soto-Díaz; Mª Teresa Rodríguez-Monje. Dirección Asistencial Sur: Susana Martín-Iglesias. Agencia Pedro Laín Entralgo: Francisco Rodríguez-Salvanés; Marta García-Solano; Rocío González-González; María Ángeles Martín-de la Sierra-San Agustín; María Vicente Herrero. Hematology Department (Severo Ochoa): Ramón Rodríguez-González. Endocrinology Department (HGCM): Irene Bretón-Lesmes. UICEC Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Plataforma SCReN; Unidad de Farmacología Clínica, Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, España; Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria, IRYCIS: Marta del Alamo Camuñas, Anabel Sánchez Espadas, Marisa Serrano Olmeda, Mª Angeles Gálvez Múgica.

Contributors: Trial Management Committee: TSC, EEM, ICG, JMF, RRF, SGE. Healthcare Centres (managers)*: JEMS, TGG, MAV, IGG, PGE, CV-MC, MNA, FGdBG, RBM, CDL, NCR, AHdD, RFG, JHH, BPG study coordination development in each healthcare centre with principal investigator supervision. Technical Support Group**: participated in different phases of the design and development of the research. MLSP, CMR, BMB, MAJ coordinated the pharmaceutical aspects. Clinical investigators: collected the data for the study, which included recruiting patients, obtaining consent, performing blood tests, applying interventions, collecting data and arranging and performing follow-up for patients. Statistical analysis: TSC, JMF, ICG, EEM with the collaboration of the Research Unit (JGM and MMM). Writing committee: TSC, EEM, ICG, JMF, SGE and RRF wrote the manuscript. All authors in the OB12 Group read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The trial was financed by Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo Español through their call for independent clinical research, Orden Ministerial SAS/2377, 2010 (EC10-115, EC10-116, EC10-117, EC10-119, EC10-122); CAIBER—Spanish Clinical Research Network, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) (CAI08/010044); and Gerencia Asistencial de Atención Primaria de Madrid. This study is also supported by the Spanish Clinical Research Network (SCReN), funded by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación y Fomento de la Investigación, project number PT13/0002/0007, within the National Research Program I+D+I 2013-2016 and co-funded with European Union ERDF funds (European Regional Development Fund). This project received a grant for the translation and publication of this article from the Foundation for Biomedical Research and Innovation in Primary Care (FIIBAP) Call 2017 for grants to promote research programs.

Disclaimer: The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, onsite monitoring, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Madrid Region Clinical Research Ethics Committee on 8 February 2011.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Individual de-identified participant data will be shared upon reasonable request. These data will include every variable used in the analysis shown in this report, and they will be available for 5 years upon request to corresponding author.

Contributor Information

and OB12 Group:

Tomás Gómez-Gascón, Isabel Gutiérrez-Sánchez, Ángeles Fernández-Abad, José Antonio Granados-Garrido, Javier Martínez-Suberviola, Margarita Beltejar-Rodríguez, Carmen Coello-Alarcón, Susana Diez-Arjona, José Enrique Mariño-Suárez, Ana Ballarín-González, Ignacio Iscar-Valenzuela, José Luis Quintana-Gómez, José Antonio González-Posada-Delgado, Enrique Revilla-Pascual, Esther Gómez-Suarez, Yolanda Fernández-Fernández, Fernanda Morales-Ortiz, Isabel Ferrer-Zapata, Esperanza Duralde-Rodríguez, Milagros Beamud-Lagos, Mª del Pilar Serrano-Simarro, Cristina Montero-García, María Domínguez-Paniagua, Sofía Causín-Serrano, Josefa San Vicente-Rodríguez, Germán Reviriego-Jaén, Margarita Camarero-Shelly, Rosa Gómez-del Forcallo, María Ángeles Miguel-Abanto, Lourdes Reyes-Martínez, Alejandro Rabanal-Basalo, Carolina Torrijos-Bravo, Pilar Gutiérrez-Valentín, Jorge Gómez-Ciriano, Susana Parra Román, Judit León-González, Mª José Nebril-Manzaneque, Juana Caro-Berzal, Alberto López-García-Franco, Sonia Redondo de-Pedro, Juan Carlos García-Álvarez, Elisa Viñuela-Beneitez, Marisa López-Martín, Nuria Sanz-López, Ana María Ibarra-Sánchez, Cecilio Gómez-Almodóvar, Javier Muñoz-Gutiérrez, Carmen Molins-Santos, Cristina Cassinello-Espinosa, Antonio Molina-Siguero, Rafael Sáez-Jiménez, Paloma Rodríguez-Almagro, Eva María Rey-Camacho, María Carmen Pérez-García, Antonio Redondo-Horcajo, Beatriz Pajuelo-Márquez, Encarnación Cidoncha-Calderón, Jesús Galindo Rubio, RosaAna Escriva Ferrairo, José Francisco Ávila-Tomas, Francisco De-Alba-Gómez, Mª Jesús Gómez-Martín, Alma María Fernández-Martínez, Rosa Feijoó-Fernández, José Vizcaíno-Sánchez-Rodrigo, Victoria Díaz-Puente, Felisa Núñez-Sáez, Luisa Asensio-Ruiz, Agustín Sánchez-Sánchez, Orlando Enríquez-Dueñas, Silvia Fidel-Jaimez, Rafael Ruiz-Morote-Aragón, Asunción Pacheco-Pascua, Belén Soriano-Hernández, Eva Álvarez-Carranza, Carmen Siguero-Pérez, Ana Morán-Escudero, María Martín-Martín, Francisco Vivas-Rubio, Rafael Pérez-Quero, Mª Isabel Manzano-Martín, César Redondo-Luciáñez, Nuria Tomás-García, Carlos Díaz-Gómez-Calcerrada, Julia Isabel Mogollo-García, Inés Melero-Redondo, Ricardo González-Gascón, María Carmen Álvarez-Orviz, María Veredas González-Márquez, Teresa SanClemente-Pastor, Amparo Corral-Rubio, Asunción Prieto-Orzanco, Cristina dela Cámara-Gonzalez, Mercedes Parrilla-Laso, Mercedes Canellas-Manrique, Maria Eloisa Rogero-Blanco, Paulino Cubero-González, Sara Sanchez-Barreiro, Mª Ángeles Aragoneses-Cañas, Ángela Auñón-Muelas, Olga Álvarez Montes, Petra María Cortes-Duran, Pilar Tardaguila-Lobato, Mar Escobar Gallegos, Antonia Pérez-de-Colosia-Zuil, Jaime Inneraraty-Martínez, María Jesús Bedoya-Frutos, María Teresa López-López, Nelly Álvarez-Fernández, Teresa Fontova-Cemeli, Josefa Marruedo-Mateo, Josefa Díaz-Serrano, Beatriz Pérez-Vallejo, Pilar Hombrados-Gonzalo, Marta Quintanilla-Santamaría, Yolanda González-Pascual, Luisa María Andrés-Arreaza, Soledad Escolar-Llamazares, Cristina Casado-Rodríguez, Luzdel Rey-Moya, Jesús Fernández-Valderrama, Alejandro Medrán-López, Julia Alonso-Arcas, Alejandra Rabanal-Carrera, Araceli Garrido-Barral, Milagros Velázquez-García, Azucena Sáez-Berlanga, Pilar Pérez-Egea, Pablo Astorga-Díaz, Carlos Casanova-García, Ana Isabel Román-Ruiz, Carmen Belinchón-Moya, Margarita Encinas-Sotillo, Virtudes Enguita-Pérez, Ester Valdés-Cruz, Consuelo Mayoral-López, Alejandro Rabanal-Basalo, Teresa Gijón-Seco, Francisca Martínez-Vallejo, Jesica Colorado-Valera, Ana Sosa-Alonso, Jeannet Sánchez-Yépez, Dolores Serrano-González, Beatriz López-Serrano, Inmaculada Santamaría-López, Paloma Morso-Peláez, Carolina López-Olmeda, Almudena García-Uceda-Sevilla, Mercedes delPilar Fernández-Girón, Leonor González-Galán, Mariano Rivera-Moreno, Luis Nistal Martín-de-Serranos, Mª Jesús López-Barroso, Margarita Torres-Parras, María Verdugo-Rosado, Mª Reyes Delgado-Pulpón, Elena Alcalá-Llorente, Sonsoles Muñoz-Moreno, Isabel Vaquero-Turiño, Ana María Sánchez-Sempere, FranciscoJavier Martínez-Sanz, Clementa Sanz-Sanchez, AnaMaría Arias-Esteso, Diego Martín-Acicoya, Pilar Kloppe-Villegas, Francisco Javier San-Andrés-Rebollo, Magdalena Canals-Aracil, Isabel García-Amor, Nieves Calvo-Arrabal, María Milagros Jimeno-Galán, Gloriade la Sierra-Ocaña, María Mercedes Araujo-Calvo, Julia Timoner-Aguilera, María Santos Santander-Gutiérrez, Alicia Mateo-Madurga, Ricardo Rodríguez-Barrientos, Milagros Rico-Blázquez, Juan Carlos Gil-Moreno, Mariel Morey-Montalvo, Amaya Azcoaga Lorenzo, Gloria Ariza-Cardiel, Elena Polentinos-Castro, Sonia Soto-Díaz, Mª Teresa Rodríguez-Monje, Susana Martín-Iglesias, Francisco Rodríguez-Salvanés, Marta García-Solano, Rocío González-González, María Vicente Herrero, Ramón Rodríguez-González, Irene Bretón-Lesmes, Martadel Alamo Camuñas, Anabel Sánchez Espadas, Marisa Serrano Olmeda, and Mª Angeles Gálvez Múgica

References

- 1. Hunt A, Harrington D, Robinson S. Vitamin B12 deficiency. BMJ 2014;349:g5226. 10.1136/bmj.g5226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ströhle A, Richter M, González‐Gross M, et al. . The Revised D‐A‐CH‐Reference Values for the Intake of Vitamin B 12 : Prevention of Deficiency and Beyond. Mol Nutr Food Res 2019;63:1801178 10.1002/mnfr.201801178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dharmarajan TS, Norkus EP. Approaches to vitamin B12 deficiency. early treatment may prevent devastating complications. Postgrad Med 2001;110:99–105. quiz 106. 10.3810/pgm.2001.07.977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pawlak R. Is vitamin B12 deficiency a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in vegetarians? Am J Prev Med 2015;48:e11–26. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang H, Li L, Qin LL, et al. . Oral vitamin B 12 versus intramuscular vitamin B 12 for vitamin B 12 deficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. García Closas R, Serra Majem L, Sabater Sales G, et al. . Distribución de la concentración sérica de vitamina C, ácido fólico Y vitamina B12 en Una muestra representativa de la población adulta de Cataluña. Medicina Clínica 2002;118:135–41. 10.1016/S0025-7753(02)72309-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Henríquez P, Doreste J, Deulofeu R, et al. . Nutritional determinants of plasma total homocysteine distribution in the Canary Islands. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007;61:111–8. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lindenbaum J, Rosenberg IH, Wilson PW, et al. . Prevalence of cobalamin deficiency in the Framingham elderly population. Am J Clin Nutr 1994;60:2–11. 10.1093/ajcn/60.1.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Niafar M, Hai F, Porhomayon J, et al. . The role of metformin on vitamin B12 deficiency: a meta-analysis review. Intern Emerg Med 2015;10:93–102. 10.1007/s11739-014-1157-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Andrès E, Dali-Youcef N, Vogel T, et al. . Oral cobalamin (vitamin B(12)) treatment. An update. Int J Lab Hematol 2009;31:1–8. 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2008.01115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Watanabe F, Yabuta Y, Tanioka Y, et al. . Biologically active vitamin B12 compounds in foods for preventing deficiency among vegetarians and elderly subjects. J Agric Food Chem 2013;61:6769–75. 10.1021/jf401545z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Langan RC, Zawistoski KJ. Update on vitamin B12 deficiency. Am Fam Physician 2011;83:1425–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dali-Youcef N, Andrès E. An update on cobalamin deficiency in adults. QJM 2009;102:17–28. 10.1093/qjmed/hcn138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Federici L, Henoun Loukili N, Zimmer J, et al. . Manifestations hématologiques de la carence en vitamine B12: données personnelles et revue de la littérature. La Revue de Médecine Interne 2007;28:225–31. 10.1016/j.revmed.2006.10.319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nilsson M, Norberg B, Hultdin J, et al. . Medical intelligence in Sweden. vitamin B12: oral compared with parenteral? Postgrad Med J 2005;81:191–3. 10.1136/pgmj.2004.020057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vidal-Alaball J, Butler CC, Cannings-John R, et al. . Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005:CD004655. 10.1002/14651858.CD004655.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Metaxas C, Mathis D, Jeger C, et al. . Early biomarker response and patient preferences to oral and intramuscular vitamin B12 substitution in primary care: a randomised parallel-group trial. Swiss Med Wkly 2017;147:1–9. 10.4414/smw.2017.14421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kwong JC, Carr D, Dhalla IA, et al. . Oral vitamin B12 therapy in the primary care setting: a qualitative and quantitative study of patient perspectives. BMC Fam Pract 2005;6:8. 10.1186/1471-2296-6-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Houle SKD, Kolber MR, Chuck AW. Should vitamin B12 tablets be included in more Canadian drug formularies? an economic model of the cost-saving potential from increased utilisation of oral versus intramuscular vitamin B12 maintenance therapy for Alberta seniors. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004501. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Graham ID, Jette N, Tetroe J, et al. . Oral cobalamin remains medicine's best kept secret. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2007;44:49–59. 10.1016/j.archger.2006.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shatsky M. Evidence for the use of intramuscular injections in outpatient practice. Am Fam Physician 2009;79:297–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rabuñal Rey R, Monte Secades R, Peña Zemsch M, et al. . ¿Debemos utilizar La vía oral como primera opción para El tratamiento del déficit de vitamina B12? Revista Clínica Española 2007;207:179–82. 10.1157/13101846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuzminski AM, Del Giacco EJ, Allen RH, et al. . Effective treatment of cobalamin deficiency with oral cobalamin. Blood 1998;92:1191–8. 10.1182/blood.V92.4.1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bolaman Z, Kadikoylu G, Yukselen V, et al. . Oral versus intramuscular cobalamin treatment in megaloblastic anemia: a single-center, prospective, randomized, open-label study. Clin Ther 2003;25:3124–34. 10.1016/S0149-2918(03)90096-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saraswathy AR, Dutta A, Simon EG, et al. . Sa1100 randomized open label trial comparing efficacy of oral versus intramuscular vitamin B12 supplementation for treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency. Gastroenterology 2012;142:S-216 10.1016/S0016-5085(12)60808-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. D'Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Sullivan LM. Non-inferiority trials: design concepts and issues - the encounters of academic consultants in statistics. Stat Med 2002;22:169–86. 10.1002/sim.1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sanz-Cuesta T, González-Escobar P, Riesgo-Fuertes R, et al. . Oral versus intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 for the treatment of patients with vitamin B12 deficiency: a pragmatic, randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority clinical trial undertaken in the primary healthcare setting (project OB12). BMC Public Health 2012;12:394. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herdman M, Badia X, Berra S. El EuroQol-5D: Una alternativa sencilla para La medición de la calidad de vida relacionada Con La salud en atención primaria. Atención Primaria 2001;28:425–9. 10.1016/S0212-6567(01)70406-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, et al. . Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA 2012;308:2594–604. 10.1001/jama.2012.87802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jones B, Jarvis P, Lewis JA, a LJ, et al. . Trials to assess equivalence: the importance of rigorous methods. BMJ 1996;313:36–9. 10.1136/bmj.313.7048.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Wetterslev J, et al. . When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials - a practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017;17:162. 10.1186/s12874-017-0442-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Blough DK, Madden CW, Hornbrook MC. Modeling risk using generalized linear models. J Health Econ 1999;18:153–71. 10.1016/S0167-6296(98)00032-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hardin J, Hilbe J, Models GL, et al. . College Station. Stata Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andrès E, Vidal-Alaball J, Federici L, et al. . Clinical aspects of cobalamin deficiency in elderly patients. epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestations, and treatment with special focus on oral cobalamin therapy. Eur J Intern Med 2007;18:456–62. 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van Uffelen JGZ, Chin A Paw MJM, Hopman-Rock M, Chin A, Paw M, et al. . The effect of walking and vitamin B supplementation on quality of life in community-dwelling adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized, controlled trial. Qual Life Res 2007;16:1137–46. 10.1007/s11136-007-9219-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hvas A-M, Juul S, Nexø E, et al. . Vitamin B-12 treatment has limited effect on health-related quality of life among individuals with elevated plasma methylmalonic acid: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Intern Med 2003;253:146–52. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01067.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moleiro J, Mão de Ferro S, Ferreira S, et al. . Efficacy of long-term oral vitamin B12 supplementation after total gastrectomy: results from a prospective study. GE Port J Gastroenterol 2018;25:117–22. 10.1159/000481860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bensky MJ, Ayalon-Dangur I, Ayalon-Dangur R, et al. . Comparison of sublingual vs. intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 for the treatment of patients with vitamin B12 deficiency. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2019;9:625–30. 10.1007/s13346-018-00613-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, et al. . The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 2015;350:h2147. 10.1136/bmj.h2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Berger JO, Bayarri MJ. The interplay of Bayesian and Frequentist analysis. Stat Sci 2004;19:58–80. 10.1214/088342304000000116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Domingo-Salvany A, Bacigalupe A, Carrasco JM, et al. . Propuestas de clase social neoweberiana Y neomarxista a partir de la Clasificación Nacional de Ocupaciones 2011. Gac Sanit 2013;27:263–72. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2012.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033687supp001.pdf (242.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033687supp002.pdf (143KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033687supp003.pdf (169.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033687supp004.pdf (83.6KB, pdf)