Abstract

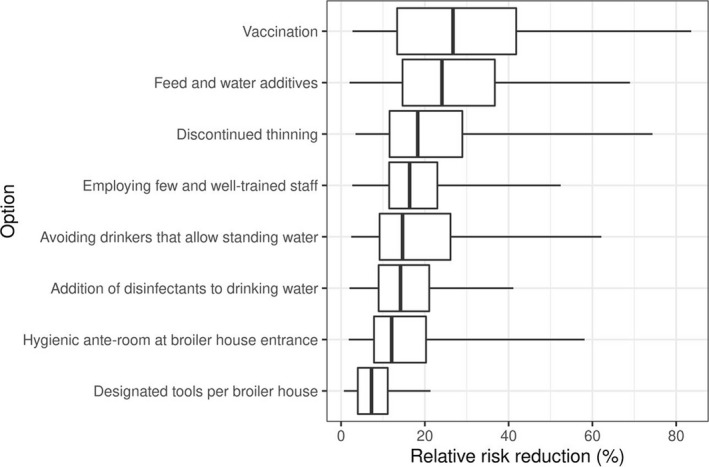

The 2011 EFSA opinion on Campylobacter was updated using more recent scientific data. The relative risk reduction in EU human campylobacteriosis attributable to broiler meat was estimated for on‐farm control options using Population Attributable Fractions (PAF) for interventions that reduce Campylobacter flock prevalence, updating the modelling approach for interventions that reduce caecal concentrations and reviewing scientific literature. According to the PAF analyses calculated for six control options, the mean relative risk reductions that could be achieved by adoption of each of these six control options individually are estimated to be substantial but the width of the confidence intervals of all control options indicates a high degree of uncertainty in the specific risk reduction potentials. The updated model resulted in lower estimates of impact than the model used in the previous opinion. A 3‐log10 reduction in broiler caecal concentrations was estimated to reduce the relative EU risk of human campylobacteriosis attributable to broiler meat by 58% compared to an estimate larger than 90% in the previous opinion. Expert Knowledge Elicitation was used to rank control options, for weighting and integrating different evidence streams and assess uncertainties. Medians of the relative risk reductions of selected control options had largely overlapping probability intervals, so the rank order was uncertain: vaccination 27% (90% probability interval (PI) 4–74%); feed and water additives 24% (90% PI 4–60%); discontinued thinning 18% (90% PI 5–65%); employing few and well‐trained staff 16% (90% PI 5–45%); avoiding drinkers that allow standing water 15% (90% PI 4–53%); addition of disinfectants to drinking water 14% (90% PI 3–36%); hygienic anterooms 12% (90% PI 3–50%); designated tools per broiler house 7% (90% PI 1–18%). It is not possible to quantify the effects of combined control activities because the evidence‐derived estimates are inter‐dependent and there is a high level of uncertainty associated with each.

Keywords: Campylobacter, Control, Broiler, primary production, biosecurity, population‐attributable fraction, modelling

Summary

In 2011, EFSA published an opinion on ‘Campylobacter in broiler meat production: Control options and performance objectives and/or targets at different stages of the food chain’. In 2018, the European Commission requested the Panel on Biological Hazards to deliver a scientific opinion updating and reviewing control options for Campylobacter in broilers, focussing on primary production. In particular, the Panel was requested to review, identify and rank the possible control options at the primary production level, considering and, if possible, quantifying the expected efficiency in reducing human campylobacteriosis cases. Advantages and disadvantages of different options at primary production should be assessed, as well as the possible synergic effect of combined control options.

The update of the previous opinion was carried out by reviewing the scientific literature published since then and by estimating the relative risk reduction, expressed as the percentage reduction in human campylobacteriosis in the EU associated with the consumption of broiler meat that could be achieved by implementing control options at primary production of broilers. The relative risk was estimated for on‐farm control options using population attributable fractions (PAF) for interventions that reduce Campylobacter flock prevalence, updating the modelling approach for interventions that reduce caecal concentrations and reviewing the scientific literature. The effect of control options that reduce the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in broilers was estimated by calculating PAF, derived from epidemiological risk factors studies, and assuming a proportionate relation between flock prevalence prior to slaughter and the associated public health risk. The effect of control options that reduce Campylobacter spp. concentration in broilers was estimated by using a regression model, associating concentrations in the caeca and on skin samples, combined with a consumer phase and a dose response model. For some control options, the relative risk reduction could not be calculated by these methods and their effect was estimated using evidence from the scientific literature.

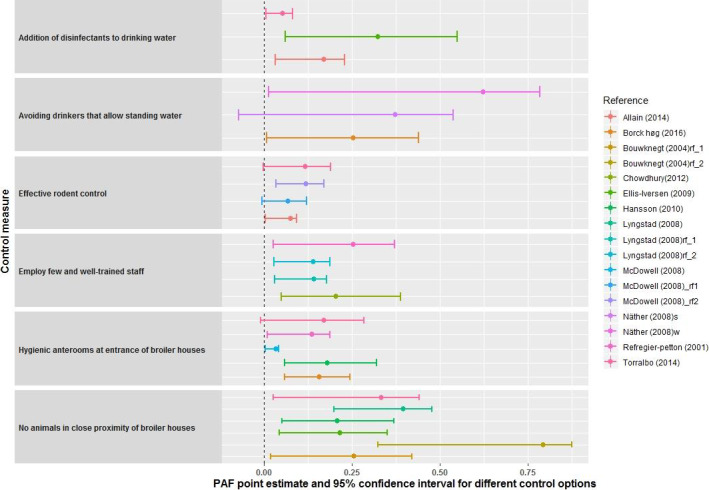

The PAF were calculated for six control options from several studies and included hygienic anteroom; effective rodent control; having no animals in close proximity to the broiler house; addition of disinfectant to drinking water; employing few and well‐trained staff and avoiding drinkers that allow standing water. The variation was greater between the different control options than for the same control options in different studies, which increased the confidence in the extrapolation potential of the results to the European Union (EU).

According to the PAF analyses, the mean relative risk reductions that could be achieved by adoption of each of these six control options individually are estimated to be substantial but the width of the confidence intervals of all control options indicates a high degree of uncertainty in the specific risk reduction potentials. For example, the mean estimate of the relative risk reduction for the control option ‘Addition of disinfectants to drinking water’ was between 5 (95% CI 0.6–8.2) and 32% (95% CI 6.0–54.9) based on three available studies.

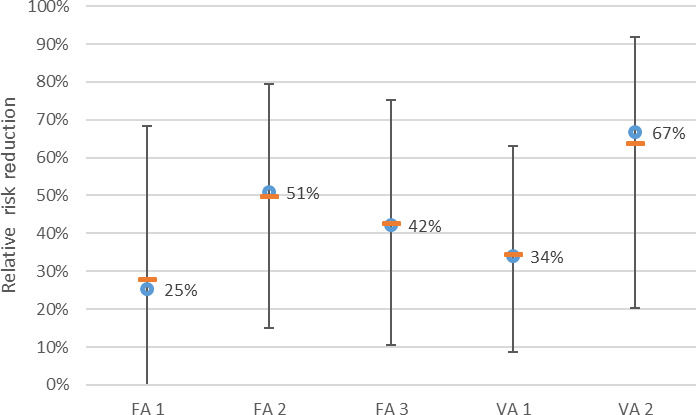

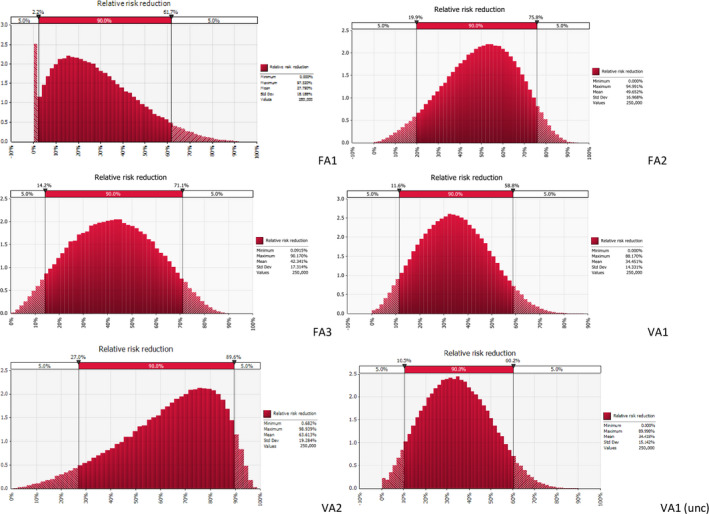

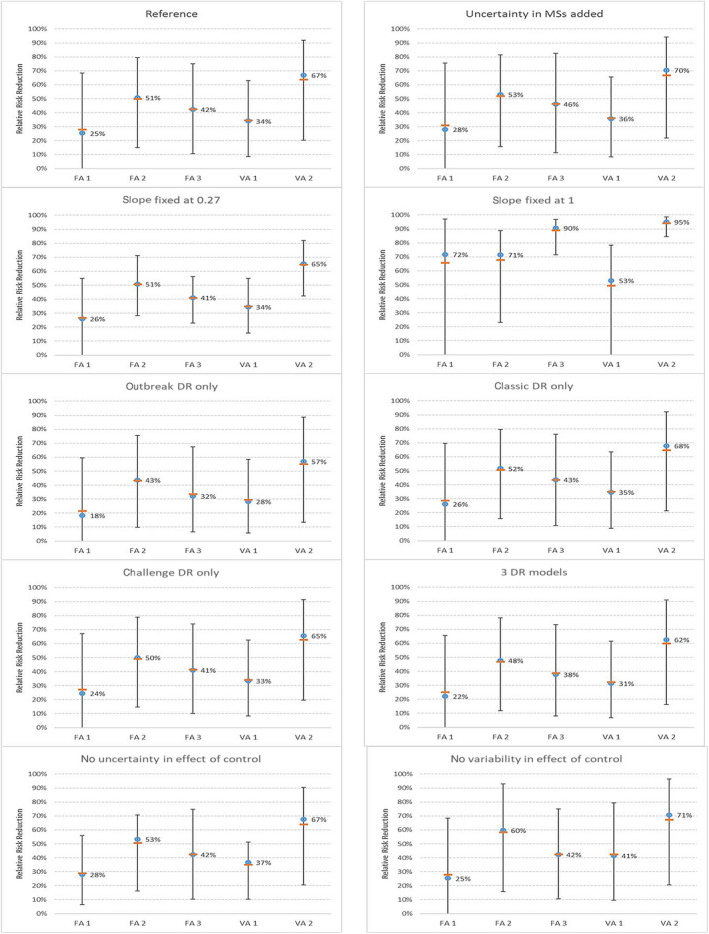

The modelling approach for relative risk reductions achieved by a reduction of Campylobacter concentrations in the caeca, previously used in the 2011 opinion, was updated. A wider variety of consumer phase models and a newly published dose response model were also included. Furthermore, newly and more extensive published data on the relationship between Campylobacter concentrations in the caeca and corresponding broiler carcass skin samples were used. The updated model resulted in lower estimates of the slope of the linear regression line describing the relation between concentrations in caecal contents and on skin. As a result of the decrease of this slope, lower estimates were obtained for the effectiveness of control options directed at a reduction in the caecal concentrations. For example, for a 2‐log10 reduction in caecal concentrations, the median estimate was now a relative risk reduction of campylobacteriosis attributable to the consumption of broiler meat produced in the EU of 42% (95% CI 11–75%), whereas in the previous opinion, this relative risk reduction was 76–98% based on data from four Member States (MSs). Similarly, a 3‐log10 reduction in broiler caecal concentrations was estimated to reduce the relative EU risk of human campylobacteriosis attributable to broiler meat by 58% (95% CI 16–89%), compared to a relative risk reduction estimate of more than 90% in four MSs, which was found previously.

Overall, the ranking of control options was informed by three different evidence streams: effect of control options to reduce flock prevalence (supported by PAF calculations based on literature data), effect of control options to reduce the concentrations in broiler caeca (supported by estimates obtained by a combination of models) and effect of control options directly obtained from literature (not supported by either PAF or modelling). Also, the evidence from regional studies and laboratory experiments had to be translated into EU wide effects in field conditions, and the current application of control measures, as well as the modelling assumptions, had to be taken into account when assessing the effectiveness of the control options. Therefore, expert judgement was required for ranking the control options considering the associated uncertainties. The Panel agreed on the use of a structured approach, based on EFSA's (2014) guidance on expert knowledge elicitation (EKE), to ensure that all the identified evidence and uncertainties were considered in a balanced way and to improve the rigour and reliability of the judgements involved.

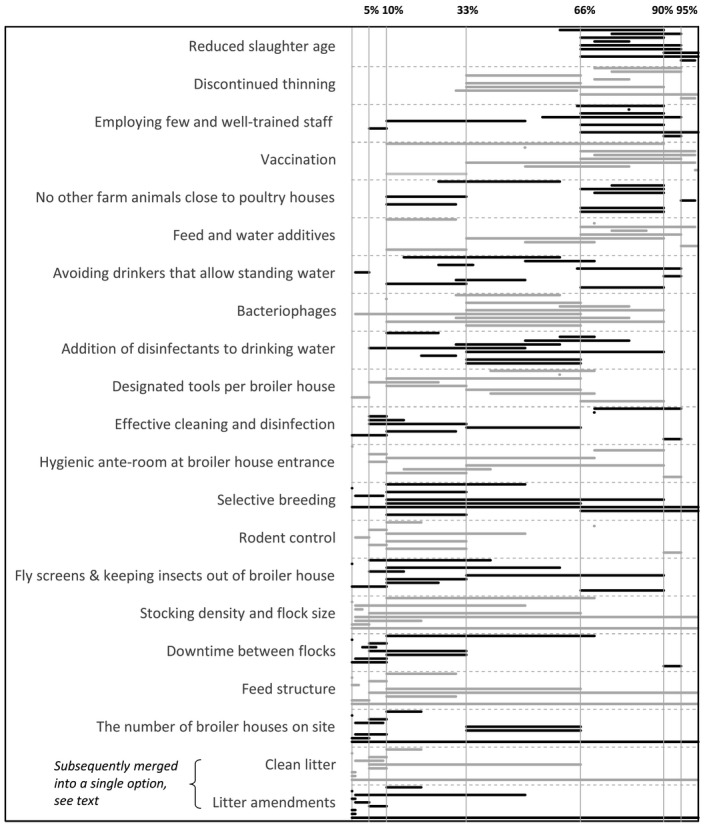

The effectiveness of 20 control options if implemented by all broiler farms in the EU, taking into account the current level of implementation, was estimated using a two‐step EKE process informed by the results from modelling of the updated scientific evidence, literature review (including the previous EFSA opinion) and also the experts’ knowledge and experience. Within the time frame of this opinion, experts made selections through the first step where all the options were considered and for the second step where eight control options were prioritised for further assessment of the magnitude of their effects.

In the first step of the EKE, for each of the control options, experts (i.e. working group members and selected EFSA staff) individually estimated the probability that the relative risk reduction would be larger than 10%. This 10% was chosen for its discriminative power in differentiating between the effectiveness of control options. The relative risk reduction was judged to have a higher probability to be larger than 10% for 12 control options: hygienic anterooms at broiler house entrance; no animals in close proximity of the broiler houses; employing few and well‐trained staff; addition of disinfectants to drinking water; avoiding drinkers that allow standing water; effective cleaning and disinfection between flocks; reduced slaughter age; discontinued thinning; designated tools for each broiler house; feed and water additives; bacteriophages and vaccination. The remaining eight control options, which were judged to have a lower probability to give more than 10% relative risk reduction included: effective rodent control; adjusting downtime between flocks; fly screens and keeping insects out of the broiler house; clean or amended litter; stocking density and flock size; the number of houses on site; selective breeding and feed structure.

From the 12 selected control options, eight options were selected for risk prioritisation based on the quality of evidence available and practical feasibility in the implementation of the control option.

The median values of the relative risk reduction of the eight prioritised control options were judged to be as follows; vaccination 27% (90% probability interval (PI) 4–74%); feed and water additives 24% (90% PI 4–60%); discontinued thinning 18% (90% PI 5–65%); employing few and well‐trained staff 16% (90% PI 5–45%); avoiding drinkers that allow standing water 15% (90% PI 4–53%); addition of disinfectants to drinking water 14% (90% PI 3–36%); hygienic anterooms at broiler house entrance 12% (90% PI 3–50%); designated tools per broiler house 7% (90% PI 1–18%). It was not possible to rank the selected control options according to effectiveness based on the EKE judgements because there is a substantial overlap of the probability intervals, due to the large uncertainties involved.

There are advantages and disadvantages associated with each control option. The advantages include ease of application (e.g. hygiene barrier, adding additives to feed), improved bird health (e.g. biosecurity actions), better broiler welfare (e.g. discontinued thinning), cross‐protection against other pathogens (e.g. drinking water treatments, feed additives). The disadvantages for a given control option may include a requirement for investment (e.g. if structural changes are required to install an anteroom), lack of control (e.g. the farmer may not own the fields adjacent to the broiler house and therefore cannot prevent other animals being close by), reduced broiler growth due to decreased consumption of feed and/or water (e.g. if an additive affected the sensory (odour, taste or appearance) properties making the feed or water less palatable).

Multiple control activities are expected to have a higher effect preventing Campylobacter spp. from entering the broiler house and infecting the birds. To minimise the risk of Campylobacter colonisation, all control activities relating to biosecurity would have to be implemented in full. It is not possible to reliably assess the effect of combined control activities because they are inter‐dependent and there is a high level of uncertainty associated with each. Some control options enhance while others reduce the effect of others. Combining two control measures targeting prevalence and concentration, respectively, may result in an additive effect, if their specific targets are unrelated.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the requestor

The 2012 EFSA opinion on the public health hazards to be covered by inspection of poultry meat1 identified the need to address Campylobacter spp. as a high priority. Since 2005, Campylobacter spp. was the most frequently reported food‐borne pathogen in the EU (more than 200,000 confirmed cases per year). The reported number of confirmed cases of campylobacteriosis represented almost 70% of the 13 reported confirmed human zoonoses in the EU in 2016. Most patients are young children and elderly people. Its occurrence was high in broiler flocks (27.3%) and in fresh meat from broilers (36.7%) in Europe. In 2010, EFSA published an opinion on ‘Quantification of the risk posed by broiler meat to human campylobacteriosis in the EU’2 and estimated that broiler meat may account for 20–30% of campylobacteriosis cases in humans, while 50–80% of these may be attributed to the chicken reservoir as a whole.

In April 2011, EFSA published an opinion on ‘Campylobacter in broiler meat production: control options and performance objectives and/or targets at different stages of the food chain’.3 Taking into account EFSA's recommendations on poultry meat inspection, the Commission proposed the introduction of a process hygiene criterion for Campylobacter spp. on poultry carcases to be respected in slaughterhouses. If not respected, the criterion leads to corrective measures taken to improve both slaughter hygiene and farm biosecurity.

Secondly, the revision of poultry meat inspection includes enhanced control of Campylobacter spp. (and Salmonella spp.), in line with the high priority set by the EFSA opinion on poultry meat inspection. Competent authorities must sample themselves for these pathogens or carefully verify the implementation of the process hygiene criterion by the operator.

According to the 2011 EFSA opinion, the public health benefits of controlling Campylobacter spp. in primary broiler production are expected to be greater than control later in the chain as the bacteria may also spread from farms to humans by other pathways than broiler meat. Nevertheless, limited information was available about such pathways, and quantification of the impact of interventions at farm level was done only for broiler meat‐related cases.

Since 2011, new scientific information is available on this matter (e.g. CAMCON, CAMPYBRO, CAMPYSAFE, CAMPYLOW projects). Thus, the time is right to request an update of the assessment of the impact of interventions at farm level and identify effective control options at primary production.

Examples of some relevant projects are provided below:

-

–

CAMCON project (https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/95053 en.html), looking at Campylobacter control at primary production level (2010–2015), with participants from different countries. Publications derived from this project are available at https://www.vetinst.no/camcon-eu;

-

–

CAMPYBRO project (http://campybro.eu), looking at Campylobacter control at primary production through nutrition and vaccination, with several partners including producers.

-

–

CAMCHAIN project (http://gtr.rcuk.ac.uk/projects?ref=BB%2FK004514%2F1) looking at transmission of Campylobacter at primary production level;

-

–

CAMPYSAFE and CAMPYLOW projects looking at the use of probiotics to control Campylobacter populations;

-

–

Other scientific papers are also reported in the literature since 2011.

Terms of Reference (ToR)

To further support food business operators in the fight against Campylobacter at farm level, in accordance with Article 29(1) (a) of Regulation (EC) No 178/2002, the Commission requests EFSA to provide an update of the scientific opinion on ‘Campylobacter in broiler meat production: control options and performance objectives and/or targets at different stages of the food chain’, more in particular to review, identify and rank the possible control options at primary production level, taking into account, and if possible quantifying, the expected efficiency in reducing human campylobacteriosis cases. Advantages and disadvantages of different options at primary production should be assessed, as well as the possible synergic effect of combined control options.

1.2. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference

In 2011, EFSA published a scientific opinion on ‘Campylobacter in broiler meat production: control options and performance objectives and/or targets at different stages of the food chain’. The aim of this mandate was interpreted to be to review and update the 2011 opinion but focussing on control options at primary production of broiler chickens in the EU/EEA.

Moreover, it was considered that the mandate included a quantitative assessment of the effectiveness of control options at primary production using risk assessment models and expressing the relative risk reduction in terms of the number of cases of human campylobacteriosis attributable to the consumption of broiler meat from the EU that could be avoided if a specific control option is implemented in all farms across Member States in EU. While the cost of implementation or feasibility of control options was outside of this remit, the advantages and disadvantages of each were discussed. Throughout the opinion, control options were assessed in terms of effectiveness. The efficiency was considered in the section discussing advantages and disadvantages of control options. ‘Biosecurity’ was defined as in the previous opinion to be, ‘a set of preventative measures implemented to reduce the risk of transmission of infectious disease from reservoirs of the infectious agent to the target host’.

To address the different parts of the ToR, assessment questions (AQ) have been formulated as:

AQ: What new scientific evidence about control options has become available since the previous opinion of 2011 and what is their relative risk reduction on campylobacteriosis?

AQ: What is the ranking in terms of effectiveness of the selected control options in reducing human campylobacteriosis cases at the primary production level?

AQ: What are the advantages and disadvantages of the selected control options?

AQ: What would be the effect of combining control options?

1.3. Additional information

1.3.1. Previous scientific opinions of the BIOHAZ Panel

In 2008, the European Commission requested EFSA to deliver a scientific opinion on the quantification of the risk posed by broiler meat to human campylobacteriosis in the EU, which was expressed as a percentage of the total number of human campylobacteriosis cases. It was concluded that handling, preparation and consumption of broiler meat may account for 20% to 30% of human cases of campylobacteriosis, while 50% to 80% may be attributed to the chicken reservoir as a whole. However, the conclusions of this scientific opinion had to be interpreted with caution because, as stated in that opinion, data for source attribution in the EU were limited and unavailable for the majority of Member States (MS) and there were indications that the epidemiology of human campylobacteriosis differed between regions. Among several recommendations, the BIOHAZ Panel recommended the establishment of active surveillance of campylobacteriosis in all MS and also to quantify the level of under‐ascertainment and underreporting of the disease, in order to more precisely estimate the burden of the disease and facilitate evaluation of the human health effects of any interventions (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2010).

In 2011, EFSA delivered a scientific opinion on Campylobacter in broiler meat production: control options and performance objectives and/or targets at different stages of the food chain. A quantitative microbiological risk assessment (QMRA) model was used to estimate the impact on human campylobacteriosis arising from the presence of Campylobacter spp. in the broiler meat chain. The model also used available quantitative data to rank/categorise selected intervention strategies in the farm to fork continuum. At the primary production level, the quantitative risk assessment concluded that there was a proportionate relationship between the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in broiler flocks and public health risk from broiler meat. The opinion described how reducing either the level of Campylobacter spp. in chicken caeca or the prevalence of positive flocks could reduce the risk to humans. The risk reduction associated with interventions in primary production was expected to vary considerably between MS. Reducing the numbers of Campylobacter spp. in the caeca at slaughter by 3 log10 units was estimated to result in a reduction of the public health risk by at least 90%. However, no feasible intervention that would achieve a reduction in the level of Campylobacter spp. in chicken caeca was identified. The models calculated that in one MS (among four MS used in the model), a 50–90% risk reduction could be achieved using fly screens in conjunction with other strict biosecurity measures. Primary production interventions assessed included fly screens (in one MS), biosecurity (in one MS), earlier slaughter and discontinued thinning. Their impact was estimated as a reduced incidence of campylobacteriosis in humans attributable to the consumption of broiler meat. However, data were sparse, introducing uncertainty in the estimates and the applicability for all EU MS was also uncertain. Thus, it was recommended that individual MS pilot any control measure before full implementation to assess the efficiency in that specific environment (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011).

Following the previous opinions, a request from the European Commission in 2010 asked EFSA to deliver a scientific opinion on the public health hazards (biological and chemical, respectively) to be covered by inspection of poultry meat and to consider any implications for animal health and animal welfare of any changes proposed to current meat inspection methods. For biological hazards, a decision tree was developed and used for risk ranking poultry meat‐borne hazards. The ranking was based on the magnitude of the human health impact, the severity of the disease in humans, the proportion of human cases that can be attributed to the handling, preparation and consumption of poultry meat and the occurrence of the hazards in poultry flocks and carcasses. Campylobacter spp. and Salmonella spp. were considered to have high public health relevance for poultry meat inspection. As none of the main biological hazards of public health relevance and associated with poultry meat can be detected by traditional visual meat inspection methods, the BIOHAZ Panel proposed the establishment of an integrated food safety assurance system including improved food chain information (FCI) and risk‐based interventions (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2012). A series of recommendations were made regarding biological hazards in relation to data collection, interpretation of monitoring results, future evaluations of the meat inspection system and hazard identification/ranking, training of all parties involved in the poultry carcass safety assurance system and needs for research on optimal ways to use FCI and approaches for assessing the public health benefits.

1.3.2. Legal background

A Process Hygiene Criterion (PHC) (Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/1495 of 23 August 2017 amending Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005) for Campylobacter spp. came into effect in January 2018. The objective of the PHC is to control contamination of carcases during the slaughtering process through monitoring and taking corrective actions when the mandated targets are breached. These actions include, in the case of unsatisfactory results (from 1.1.2020, if 15 out of 50 samples of carcasses after chilling have counts > 1,000 CFU/g) improvements in the slaughter hygiene, the review of process controls and improvement in the biosecurity measures in the farms of origin.

1.3.3. Approach to answer the term of reference

A literature search focussing on the time period after the previous scientific opinion (i.e. between 2011 and 2019) was carried out to update the scientific opinion on ‘Campylobacter in broiler meat production: control options and performance objectives and/or targets at different stages of the food chain.’

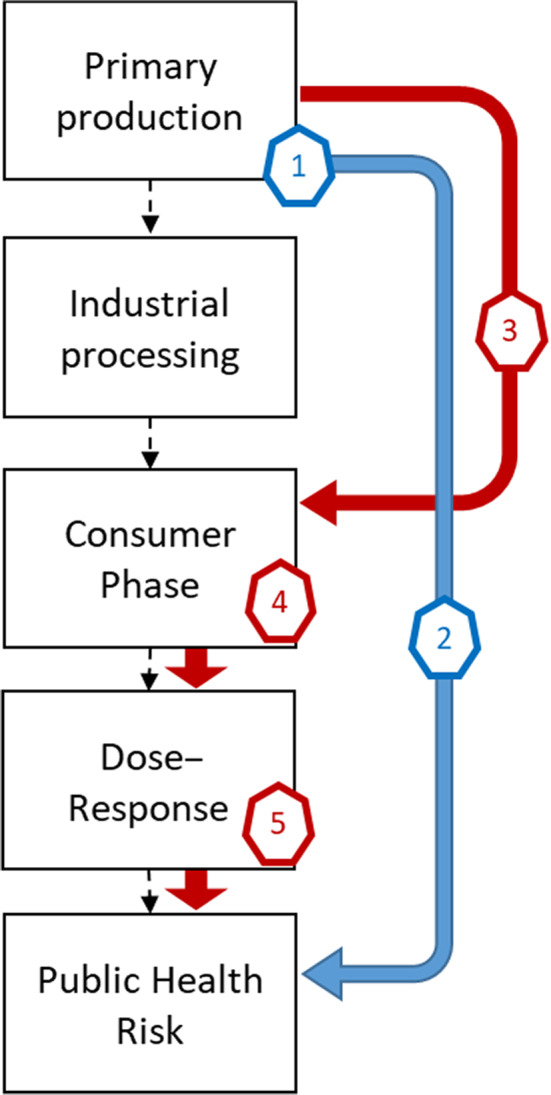

The effectiveness of control options was estimated using two different modelling approaches for (a) control options reducing the Campylobacter spp. prevalence in broiler flocks sent to slaughter and (b) control options reducing the Campylobacter spp. concentration in their caecal content. The modelling steps used to estimate the effect on public health by reducing Campylobacter spp. flock prevalence (1–2) and concentrations in caecal content (3–5) are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Modelling steps used to estimate the effect on public health by reducing Campylobacter spp. flock prevalence (blue arrow) and concentrations in caecal content (red arrows) in broilers. The numbers show the steps used in the two models, respectively

The reduction of flock prevalence was estimated by using (1) population attributable fractions (PAF)4 derived from epidemiological risk factors studies and (2) assuming a proportionate relationship between flock prevalence and public health risk (see Section 2.2 for details).

The effect of reduced Campylobacter spp. concentrations was modelled by (3) a regression model relating the concentration in the caeca with the concentration on the broiler meat, (4) a consumer phase model describing the effect of food preparation and (5) a dose response (DR) model (see Section 2.3 for details). In both approaches, the effectiveness of the control options is expressed as the relative risk reduction, that is the relative reduction in the incidence of human campylobacteriosis caused by the consumption of broiler meat, if the control option is implemented at all farms in the EU:

where

-

–

RRR is the relative risk reduction,

-

–

Inccurr is the current incidence of human campylobacteriosis attributable to broiler meat in the EU,

-

–

Incint is the new estimated incidence of human campylobacteriosis attributable to the consumption of broiler meat after implementation of the control option at all farms in the EU.

The ranking of control options is based on the assessment of their potential effectiveness, using Expert Knowledge Elicitation (EKE) to combine the different streams of evidence and consider their associated uncertainties.

Advantages and disadvantages of selected control options were assessed using literature search and expert judgement.

The impact of combinations of two or more selected control options, including the potential for synergism, was assessed based on the literature search and expert judgement.

2. Data and methodologies

2.1. Literature search

A literature search was undertaken, focusing on papers published between 2011 and 2019 (inclusive) on Campylobacter, risk factors and control options on broiler farms. In addition, manual searching of the reference list of these documents was performed to identify additional relevant information. This was supplemented by relevant published studies identified by the members of the Working Group (WG) and EFSA Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ) Panel throughout the term of the mandate until the WG members were satisfied that a thorough coverage of the subject had been achieved.

2.2. Modelling the effect of control options to reduce the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in broilers

2.2.1. Literature search to inform calculation of population‐attributable fractions (PAF)

For the analysis of the PAF, the timeframe searched was expanded to 2004–2019 (inclusive) because epidemiological risk factor studies are limited and PAF analyses had not been carried out in the previous opinion. Only those studies that contained all of the following were included: [1] presentation of multi‐variable model outputs including estimates to calculate adjusted odds ratio (OR) and confidence intervals; [2] descriptive data showing the proportion of farms/flocks in the different categories, [3] data on biosecurity/on‐farm practices and [4] the sample size was ≥ 35 study units.

The search string used was: ((campylobacter AND (risk AND factor*) AND (farm* OR husbandry* OR (primary AND production*)) AND (chicken* OR broiler* OR poultry OR Gallus gallus)) and yielded 245 studies.

Abstracts of these papers were screened and, if no multivariable analysis was reported, the studies were excluded because, if the model does not adjust for confounding effects, where farming practices interact and are associated with each other (Stafford et al., 2008), the risk factor specific estimates are likely to be highly distorted. Overall, 31 studies were retained.

Full papers of these 31 studies were assessed and excluded if they did not contain all of the following: [1] presentation of multi‐variable model outputs including estimates to calculate adjusted OR and confidence intervals; [2] descriptive data showing the proportion of farms/flocks in the different categories and [3] data on biosecurity/on‐farm practices. Studies were also excluded if the sample size was less than 35 study units. This resulted in 17 studies in 15 articles for inclusion in the PAF analysis (see Table 6 in chapter 3.3.1).

Table 6.

Overview of the selected studies for calculation of the population attributable fraction for control options to reduce the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in the primary production of broilers

| Reference | Country | Year of study | Number of flocks/farms | Campylobacter spp. prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allain et al. (2014) | France | 2008 | 121/121a | 71.9 |

| Barrios et al. (2006) | Iceland | 2001–2003 | 1091/36 | 15.4 |

| Borck Høg et al. (2016) | Denmark | 2010–2012 | 3328/104 | 9.5 |

| Borck Høg et al. (2016) | Norway | 2010–2012 | 1381/173 | 3.5 |

| Bouwknegt et al. (2004) | Netherlands | 1997–2000 | 495/461a | 26.3 |

| Chowdhury et al. (2012) | Denmark | 2009–2010 | 2835/187 | 14 |

| Ellis‐Iversen et al. (2009) | United Kingdom | 2003–2006 | 603/137 | 34.2 |

| Hansson et al. (2010) | Sweden | 2005 | 37/37 | 56.8 |

| Jonsson et al. (2012) | Norway | 2002–2007 | 18488/623 | 4.7 |

| Lyngstad et al. (2008) | Norway | 2005 | 131/131 | n.a. |

| McDowell et al. (2008) | Northern Ireland | 2001–2002 | 388/88 | 42 |

| Näther et al. (2009) Summer | Germany | 2004–2005 | 146/146 | 53 |

| Näther et al. (2009) Winter | Germany | 2004–2005 | 146/146 | 34 |

| Refregier‐Petton et al. (2001) | France | 2001 | 75/75 | 42.7 |

| Torralbo et al. (2014) | Spain | 2010–2012 | 291/134 | 62.5 |

Estimated from information provided in the articles.

2.2.2. Calculation of population attributable fractions (PAF)

Control measures to reduce the prevalence in broilers are aimed at preventing the introduction of Campylobacter spp. into the broiler house and the subsequent colonisation of the birds. A wide variety of measures and practices improve hygiene and biosecurity and are described in the literature review (Section 3.3). To assess the magnitude of control obtained by an intervention, studies that measure the prevalence with and without a control option are required. Intervention studies on the effect of improving biosecurity and changing farmer behaviour are limited. Assessing the effect of changes to multiple practices, with large variability in behaviours before and after interventions, varying compliance levels and interaction between practices, requires a very large sample size and repeated sampling to identify even large effects of interventions (Ellis‐Iversen et al., 2008). Therefore, most studies on biosecurity practises and their association with Campylobacter status are designed as risk factor studies providing a cross‐sectional picture of what happens more often during rearing of positive flocks than during rearing of negative flocks. Such epidemiological risk factor studies allow for multivariate modelling and the possibility to adjust for confounding factors and thereby provide an estimate of risk of a specific behaviour or practice.

Epidemiological risk factor studies are by their nature field studies. The data include the heterogeneity, diversity and variability in human and animal populations, e.g. different genetics or behavioural differences, differences in biosecurity practices, etc., reflecting real life. This contrasts with the standardisation used for experimental studies, where the study design usually removes diversity and minimises variability.

The strength of association derived from epidemiological risk factor studies is often much smaller than the measure of the effect of the same control option in an experimental study, due to the variability and heterogeneity of the population in the epidemiological study. Epidemiological risk factor studies are not able to detect small associations, which fully controlled experimental studies may be able to identify with statistical significance. On the other hand, the effects measured in the epidemiological risk factor studies include the heterogeneity of the farm environment, human factors and variety in practices and the results can be extrapolated to ‘real life’ situations with higher certainty than experimental studies in a small designed setting.

To interpret the effect of changing farm management practices on the risk of colonisation of broiler flocks with Campylobacter spp., the ORs can be transformed into PAF. This provides a measure of the proportion of cases (positive flocks) estimated to be linked to a specific risk factor. The World Health Organisation defines PAF as ‘the proportional reduction in population disease or mortality that would occur if exposure to a risk factor were reduced to an alternative ideal exposure’. It is assumed that the interventions are applied on the new farms to a similar degree as on farms that already applied the intervention at the time of the risk factor study. PAF is also applied to food‐borne zoonotic diseases in public health and has been calculated in at least two published studies on Campylobacter spp. in chicken (Georgiev et al., 2017; Rosner et al., 2017). For the scope of this opinion, population disease or mortality is interpreted as colonised broiler flocks, and only modifiable risk factors, for which control options within the farmer's control exist, were considered for the PAF analysis. Non‐modifiable risk factors such as the season or factors related to the geographical location of the farm were excluded. Only control options identified in at least two MS were included.

In epidemiological studies exploring associations with risk factors, there is a marked heterogeneity not only in the risk factors included in the analysis but also in the definition or wording of the risk factors related to the explanatory variables. As an example, a French study (Allain et al., 2014) found ‘No rodent control outside the house’ to be significantly associated with the occurrence of Campylobacter spp. in the broiler flocks while ‘presence of rodents in the poultry house’ was identified as a risk factor in a Spanish study (Torralbo et al., 2014).

Although these definitions relate to two different aspects, they are assessing the presence of the same underlying risk (i.e. presence of rodents); hence, ‘Having an effective rodent control program in place’ is the control practice reducing the risk recommended in both studies. Widening the wording of the control option to address several narrowly defined risk factors may also help account for variability in farming systems within and between MS.

PAF estimates need to be as precise as possible for the control option, despite farming practices which often interact or are associated with each other (confounding) (Stafford et al., 2008). In epidemiological risk factor studies, confounding is adjusted for by statistical modelling, usually by regression analysis, providing adjusted ORs to reduce this bias. In this opinion, we have only used adjusted OR.

From the selected studies, we extracted the following variables: (1) country, (2) number of units in study, (3) year of data collection. We also extracted the following parameters for each modifiable risk factor:

Wording of risk practice

Baseline practice (comparison)

Adjusted OR + confidence intervals

% positive in exposed group

% positive in non‐exposed group

% in study carrying out risk practice

If any of the above estimates were not directly available in the publication, they were calculated by inversing ‘protective ORs’ into ‘risk ORs’ including their confidence intervals or estimated from other model outputs, e.g. the standard error (SE).

After the extraction, adjusted OR and their confidence intervals were transformed to adjusted Relative Risk with confidence intervals using the formula (Equation (1)) from Zhang and Kai (1998).

| (1) |

with P0 the Campylobacter spp. prevalence in the group without implementation of the control option and ORadj the adjusted OR.

If a risk factor was identified as significant and data needed in the equation were available from the literature, the PAF was estimated using Levin's formula (Equation (2), Levin, 1953):

| (2) |

where pexp is the proportion of the population exposed to the risk factor and RRadj is the calculated adjusted relative risk between colonised and non‐colonised flocks as described above (Equation (1)).

Risk factors from all studies were then grouped by the practice or action needed to control the risk. For each control measure the representativeness was considered and factors were only included in the final modelling if PAF estimates were available from at least two MS.

2.2.3. The proportionate relationship between flock prevalence and public health risk

The model assumes that the relative reduction in flock prevalence caused by an intervention at primary production translates directly into a relative reduction in risk from the broiler meat to humans. Hence, with Inccurr and Incint as defined in Section 1.3.3; and FPcurr being the current flock prevalence and FPint being the flock prevalence after implementation of a control option, it is assumed that Incint/Inccurr = FPint/FPcurr.

This assumption is also made in several previous published risk assessment models and in the previous EFSA opinion (Nauta et al., 2009; EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011). The underlying argument is that analyses performed by these risk assessment models suggest that meat from flocks that are not colonised does not add significantly to the public health risk. Even though cross‐contamination between carcases of birds from flocks is known to occur during slaughter, it is assumed to only have a small effect on the public health risk, because Campylobacter spp. concentrations on meat from cross‐contaminated flocks will be several orders of magnitude lower than those from flocks colonised at primary production (Havelaar et al., 2007; Nauta et al., 2009; EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011).

In this opinion, the PAF values were interpreted as the proportional reduction in flock prevalence that would occur if exposure to a risk factor was eliminated (i.e. the associated control option was applied throughout the EU). This means that the PAF is equivalent to: 1−FPint/FPcurr and also to the estimated RRR defined in Section 1.3.3.

2.3. Modelling the effect of control options to reduce the concentration of Campylobacter spp. in broilers

The modelling approach applied for the effect of control options to reduce the concentration of Campylobacter spp. is explained below; details are given in Appendix A.

2.3.1. Literature search

A generic literature search has been carried out to identify studies that analysed the association between concentrations in the caeca of broilers and broiler meat products after industrial processing (see Appendix B).

2.3.2. Linear regression for concentration in caecal content and on skin of broiler meat

A model for the effect of control options that reduce the caecal concentration of Campylobacter spp. in broilers at primary production should describe how the caecal concentrations relate to concentrations on the meat. Two approaches have been used to describe this relationship: (i) the use of QMRA models that describe the dynamics of transfer and survival of Campylobacter spp. through the broiler meat production chain after primary production (Nauta et al., 2009; Chapman et al., 2016); (ii) the study of the association between concentrations of Campylobacter spp. found in the caecal content (usually called ‘caecal samples’) and on the end products (whole carcass, skin or meat samples) after the industrial processing, by means of linear regression. When the two approaches (QMRA and regression models) were compared, the results were similar, even though the QMRA models predicted the relation between the two concentrations as not linear, but J‐shaped (Nauta et al., 2016).

As in the previous opinion (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011), a linear regression approach was applied using a regression model to translate a change in bacterial concentration in the chicken caeca into a change in concentration on broiler skin, which assumes to represent a change in concentration on the meat. The approach allows the use of observational data from different European studies and does not require assumptions and data interpretation on the complex dynamics of transfer and survival of Campylobacter spp. during industrial processing. As explained in Appendix A, the slope of the regression line is needed to estimate the change in concentrations on broiler skin after industrial processing, given that the mean effect of an intervention (in terms of log reduction) and its standard deviation (expressing the variability in effect) are known. Data on Campylobacter spp. concentration on broiler skin were obtained from the EU baseline survey from 2008 (EFSA, 2010). Although these data are more than 10 years old and do not take into account the improvements in Campylobacter control arising from the measures implemented in MSs since then, they are, none‐the‐less, the only data available for all MSs, obtained using a harmonised sampling strategy.

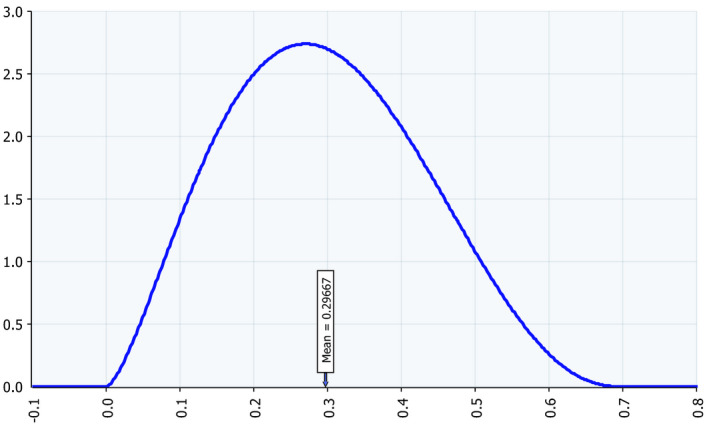

The results of the literature review for the association between concentrations in the caeca and on skin samples or broiler meat after industrial processing are summarised in Appendix B and Table 1. In total, 15 studies were retrieved, that used different analytical methods for enumeration. Six of those studies reported no significant correlation and nine found values of the slope of the regression line between 0.21 and 1.15. In one of the six largest studies, with more than 50 batches analysed, Reich et al., 2018, found no positive correlation; the four studies publishing a regression line found slopes varying between 0.21 and 0.32. In this assessment, the uncertainty of the slope was expressed as a BetaPert distribution with minimum of 0, maximum of 0.7 and a most likely value of 0.27. This last value corresponds to the slope value obtained by linear regression on the largest data set, from the APHA/FSA monitoring programme for Campylobacter spp. in broiler flocks and broiler carcases in the UK (2012–2017) (FS241051, FS101126). The data set included paired caeca–skin microbiological data (enumeration according to ISO 10272‐2) for 1752 batches slaughtered in different abattoirs in UK.

Table 1.

Summary table of regression lines found in the literature

| Reference | Significant correlation?(a) | Slope | r or r2(a) | Number of batches | Number of slaughter plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al. (2007) | No | – | – | 26 | 4 |

| Boysen et al. (2016) | Yes | 0.70 | r2 = 0.72 | 15 | 3 |

| Brena et al. (2013) | Yes | 0.21 | r2 = 0.23 | 76 | 3 |

| Duffy et al. (2014) | No | – | – | 4 | 2 |

| Elvers et al. (2011) | No | – | – | 5 | – |

| Hue et al. (2011) | Yes | 0.32 | r = 0.33 | 425 (297 pos.) | 58 |

| Laureano et al. (2013) | Yes | 0.28 | r2 = 0.26 | 80 | 10 |

| Malher et al. (2011) | Yes | ND | r = 0.28 | 140 (91 pos.) | 3 |

| Nauta et al. (2009) | No | – | – | 22 | – |

| Reich et al. (2008) | Yes | ND | r = 0.64 | 40 | 1 |

| Reich et al. (2018) | No | – | – | 365 | 3 |

| Rodgers (2020) | Yes | 0.27 | r2 = 0.48 | 1,146 | 19 |

| Rosenquist et al. (2006) | Yes | 1.15 | – | 6 | 2 |

| Stern and Robach (2003) | No | – | – | 20 | 1 |

| Vinueza‐Burgos et al. (2018) | Yes | 0.50 | r2 = 0.57 | 15 | 3 |

An extended version of this table is given in Appendix B.

As reported in the given reference.

r = linear correlation coefficient; r2 = coefficient of determination.

– = not determined or no value given.

2.3.3. Consumer Phase model (CPM)

The consumer phase is the last part in the food chain, where exposure to Campylobacter spp. occurs. As explained in more detail in Appendix A, it describes how the concentration on the skin or on the meat is linked to the dose ingested by the consumer. Food preparation and associated cross‐contamination of other foods have an important effect on the exposure. Modelling the consumer phase is challenging because data are scarce and difficult to obtain, the variability in food handling practices between (groups of) consumers is large and the effect on transfer and survival of Campylobacter spp. is not easily described.

As reviewed by Chapman et al. (2016), a large variety of CPMs are available that may include different routes of Campylobacter spp. transfer (cross‐contamination) and undercooking. Recently, another model estimating the effects of consumer habits during preparation of chicken meat has been proposed (Poisson et al., 2015; ANSES, 2018). From an initial level of contamination of 1.4 log10 CFU/g, the authors estimated a risk reduction of 50% if 100% of consumers adopted best practice during preparation or the initial load is reduced to 0.4 log10 CFU/g. A comparative analysis, Nauta and Christensen (2011) studied eight different CPMs and compared their performance in terms of the predicted effect of intervention measures before the consumer phase on the risk estimates. It was found that the difference between the relative risk estimates of the different models is often small. A CPM that performs intermediately (i.e. providing results falling in the range of the others) is based on the observational data described by Nauta et al. (2008) and has been applied in the previous EFSA opinion as the ‘classic +’ DR model (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011; Nauta et al., 2012).

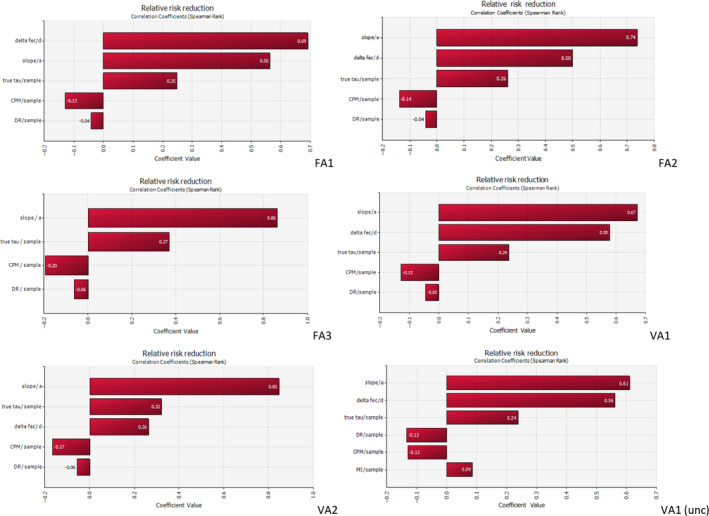

In this opinion, the eight available CPMs (Christensen et al., 2001; Mylius et al., 2007; van Asselt et al., 2008; Brynestad et al., 2008; Calistri and Giovannini, 2008; Lindqvist and Lindblad, 2008; Nauta et al., 2008; WHO, 2009) that were compared by Nauta and Christensen (2011) were used to evaluate the uncertainty due to the choice of the CPMs. These CPMs apply a broad range of different cross‐contamination scenarios and use different data on food handling practices, routes of cross‐contamination, transfer rates and meat product and/or cross contaminated food product. None of the models specifically addresses undercooking, although it is implicitly included in the Nauta et al. (2008) model, which is solely based on observational data. No additional CPMs were included as the selected eight already represent a large variety of models and it appeared that the choice of the CPM had only limited impact on the uncertainty of the results (Nauta and Christensen (2011); see also the tornado plots for correlation coefficients in Appendix C).

2.3.4. Dose response model

A dose response model describes how an ingested dose relates to the probability of infection and/or the probability of illness in humans. Until now, the majority of Campylobacter QMRA studies, including the previous EFSA opinion (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011), have applied the ‘classic’ dose response model published by Teunis and Havelaar (2000), based on a human challenge study (Black et al., 1988) in which the strain A3249 was used. After an analysis of several additional data sets from both human and primate challenge studies, as well as a set of outbreak studies, the choice of this model was recently criticised by Teunis et al. (2018) as ‘an unfortunate choice’ as the default model for many risk assessments for Campylobacter spp., because A3249 seems to be of low virulence and is therefore a non‐representative strain. Therefore, next to the classic dose response model, two additional dose response models were used that were considered representative for the challenge studies and the outbreak studies reported by Teunis et al. (2018), as explained in Appendix A.

2.3.5. Selection of control options

A set of control options affecting the concentrations in the caecal content was selected, based on the literature study as described in Section 2.1.

Control options to reduce Campylobacter spp. concentration in the caeca were primarily selected based on new information that became available since the EFSA 2011 Opinion was published. From these, several control interventions (vaccines, prebiotic/other feed additives and bacteriophages) were selected for inclusion in model analysis based on: [1] evidence that the control activity had a reductive effect on the Campylobacter spp. concentrations in the caeca and/or faeces; [2] type of study (experimental and field trials using broilers); [3] inclusion of control (untreated) birds in the study; [4] sufficient data including mean log reduction and standard error (or equivalent); [5] number of birds included in the trial and frequency of sampling (statistically‐ based experimental design), [6] samples tested (at least caecal content samples); and [7] the length of the trial including the period of sampling (close to field practices, 35–42 days).

From the selected studies, the most and least effective values of different control options found (i.e. for vaccines and feed additives) were selected for modelling. The values were used to indicate the range of potential beneficial effects found in the literature, but references to specific vaccines or feed additives are not made, as the reproducibility of the quantitative results obtained by simulations in the present opinion, if applied in field conditions, remains unknown.

2.3.6. Model description and implementation

Appendix A provides a more detailed description of the modelling approach for the effect of control options to reduce the concentration of Campylobacter spp. in broilers. The linear regression model, consumer phase model and DR model are combined and implemented in an Excel spreadsheet (Nauta, 2020), using the model implementation approach described by Nauta and Christensen (2011).

The model allows an estimation of the RRR to be made based on a mean and standard deviation of the effect of the intervention in terms of log reduction in caecal concentration (d and sd); the regression line slope (a); the choice of an EU MS or the EU average (for current concentrations of broiler skin after processing (mskin and sskin)); a value of the log difference between skin samples and meat (τ); the choice of a CPM; the choice of a DR model. A version of the model implemented in @Risk version 7.6 allows analysis of the uncertainty by providing the uncertainty of the input parameters a, d, and τ, as well as the uncertainty in the choice of the MS (mskin and sskin), the choice of the CPM and the choice of the DR. Variability is included into the model analytically, uncertainty is modelled by Monte Carlo simulation, using 250.000 iterations per simulation.

Table 2 shows the options included in this model. For the uncertainty analysis of the model that informed the EKE, the difference between skin concentrations found in different MSs was not included, as the effect of control options is expressed at EU level.

Table 2.

Overview of the default model values chosen, if uncertainty is not included, and the way the uncertainty about the choice of the model or model parameter is described, if uncertainty is included. The options given in bold are used for the uncertainty analysis that informed the Expert Knowledge Elicitation (the reference model)

| Default values | Reference | Uncertainty | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope of regression line caeca – skin samples | a = 0.27 | Rodgers (2020) | BetaPert (0, 0.27, 0.7) | This opinion |

| Log difference between concentration on skin and meat | τ = 1 | EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (2011) | Uniform (0,3) | Nauta et al. (2012) |

| Member States (skin concentrations measured in EU baseline 2008) | EU‐weighted mean | Nauta et al. (2012) (derived from EU baseline study 2008) | Randomly select 1 Member State | Nauta et al. (2012) (derived from EU baseline study 2008) |

| Consumer phase model | Nauta et al. (2008) | EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (2011) | Randomly select one of eight models | Nauta and Christensen (2011) |

| Dose response model | Classic model | EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (2011) | Randomly select ‘classic’ or ‘median challenge’ model | This opinion |

A sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of different modelling choices on the estimated effects of the selected control options.

2.4. Ranking and Uncertainty assessment

The ToR required a ranking of the possible control options at primary production level, and, if possible, quantifying the expected effectiveness of control actions on the broiler farm in terms of reducing human campylobacteriosis cases. Uncertainties affecting both the effectiveness estimates and the ranking of the different control options were considered by application of the framework provided by EFSA's uncertainty guidance (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2018).

For some control options, the expected reduction in campylobacteriosis cases could be estimated in one of two ways: calculate the PAF for control options that reduce the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in broilers (Section 2.2); or by means of quantitative probabilistic modelling for control options aimed at reducing the level of intestinal Campylobacter spp. concentrations in broilers (Section 2.3). Statistical uncertainty affecting these estimates was described and quantified by confidence intervals for the PAF and sensitivity analysis for the stochastic model (See Appendix C). Other uncertainties are addressed as described below.

The expected effect of the control options in reducing the incidence of human campylobacteriosis in EU by all MS was made by means of expert judgement; thus taking into account sources of systematic uncertainty arising when trying to infer the analytical evidence from the PAF analysis and simulation model at EU level. Expert judgement was also used to take additional evidence on these control options from the 2011 Opinion and subsequent publications (for which PAF could not be calculated or quantitative effects could not be simulated) into account.

Ranking of control options was therefore informed by three different evidence streams: effect of control options to reduce prevalence (supported by PAF and literature), effect of control options to reduce the level of contamination in broilers (supported by probabilistic modelling) and the effect of control options from the scientific literature (not supported by either PAF or probabilistic modelling). Expert judgement was therefore essential for ranking the control options, both for weighing and integrating the different streams of evidence and for considering their associated uncertainties. The BIOHAZ Panel agreed on the use of a structured approach, based on EFSA's (2014) guidance on expert knowledge elicitation (EKE), to ensure that all the identified evidence and uncertainties were considered in a balanced way and to improve the rigour and reliability of the judgements involved.

Due to the large number of control options to be considered within the time available, the EKE was conducted in two steps to allow for greater focus on the control options that were more likely to be effective. In the first step, experts assessed the probability that each control option would, if implemented by all EU broiler producers, reduce the incidence of campylobacteriosis in the EU by at least 10%. This step provided an initial ranking that was used to identify a subset of control options for more detailed assessment in the second step.

In the second step, experts assessed the magnitude of reduction in campylobacteriosis in the EU that each of the prioritised control options would achieve, if implemented by all EU broiler producers. In both steps, each control option was assessed separately, assuming all other control options remained at their present level of implementation. The detailed process is described in Section 3.5, together with the results and in Appendix D.

In both steps, the expert judgements were made by members of the EFSA Working Group and EFSA staff that were involved in the drafting of this Opinion. When assessing the effects of control options, all the relevant evidence available to the Working Group was considered. This included evidence from the 2011 Opinion, evidence from scientific literature published since 2011 and results from both the modelling approaches. The sources of systemic uncertainty identified by the Working Group as relevant to the assessment of the control options were also considered. To help experts take all the relevant evidence and uncertainties into account in a balanced way, the Working Group prepared two tables summarising key aspects of the evidence on control options affecting concentrations and prevalence, and a third table summarising the identified sources of uncertainty (Appendix D).

2.4.1. Step 1. Screening of all control options

A list of 21 control options was agreed to be considered for ranking. This list resulted from the review of the 2011 opinion and updating the information provided (Section 2.1), the PAF analysis (Section 2.2) and modelling (Section 2.3):

Reduced slaughter age

Discontinued thinning

Employing few and well‐trained staff

Vaccination

No animals in close proximity to the broiler houses

Feed and water additives

Avoiding drinkers that allow standing water

Bacteriophage

Addition of disinfectants to drinking water

Designated tools per broiler house

Effective cleaning and disinfection

Hygienic anterooms at broiler house entrance

Selective breeding

Effective rodent control

Fly screens and keeping insects out of the broiler house

Stocking density and flock size

Downtime between flocks

Feed structure

The number of houses on site

Clean litter

Litter amendments

In the first step of EKE, for each control option, each expert assessed the probability that it would reduce the campylobacteriosis incidence in humans in the EU associated with the preparation and consumption of broiler meat by 10% or more, if implemented by all broiler farmers in the EU. The threshold was set at 10% to obtain sufficient discriminatory power in the EKE. If a lower threshold was used (i.e. 5%), most of the control options would have been considered as potentially effective, undermining the identification of the most promising control options that would be subject to detailed assessment in step 2. Note that the 10% was not meant to indicate a threshold level in terms of effectiveness and does not imply that 10% would be a sufficient reduction or not. To ensure that questions for eliciting probability judgements were well defined (EFSA, 2014), it was agreed to define the question for step 1 in more detail as follows:

What is the probability that, if the specified control option was implemented by all broiler producers in the EU that are not currently using it, the average annual incidence of campylobacteriosis cases in the whole EU population caused by Campylobacter spp. in broiler meat produced from chickens raised in the EU would reduce by more than 10% (compared to the current level), all other things being equal?

The following subsidiary definitions were used:

The meaning of ‘campylobacteriosis cases’ was clear for the experts and does not require further definition.

‘Other things being equal’ includes other control options remaining at the current level of implementation, production and processing practices remain unaltered and no change in the consumption in the EU of meat from broilers raised in the EU.

If a control option acts on both prevalence and concentration, both should be considered when answering the question.

For each control option, the experts answered the question assuming that, of the specific practices for this control option which are referred to in this Opinion (e.g. different vaccines, or different methods of rodent control), the practice that would, on its own, achieve the largest reduction in campylobacteriosis would be implemented by all EU broiler producers.

Experts expressing their judgement as precise or ranges of probabilities (see Table 3) (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2018).

Table 3.

Approximate probability scale adopted for harmonised use in EFSA (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2018)

| Probability term | Subjective probability range | Additional options | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Almost certain | 99–100% | More likely than not: > 50% |

Unable to give any probability: range is 0–100% Report as ‘inconclusive’, ‘cannot conclude’ or ‘unknown’ |

| Extremely likely | 95–99% | ||

| Very likely | 90–95% | ||

| Likely | 66–90% | ||

| About as likely as not | 33–66% | ||

| Unlikely | 10–33% | ||

| Extremely unlikely | 1–5% | ||

| Almost impossible | 0–1% | ||

2.4.2. Step 2. Detailed assessment of selected control options

The subset of the control options to be prioritised for detailed assessment in step 2 was informed by experts’ discussion upon results of step 1, the quality of evidence available, practical feasibility in the implementation of the control option and unequivocal definition of the control measure.

Selection resulted in eight control options (i.e. discontinued thinning, employing few and well‐trained staff, vaccination, feed and water additives, avoiding drinkers that allow standing water, addition of disinfectants to drinking water, designated tools per broiler house, hygienic anterooms at broiler house entrance) for which it was considered that the second step of EKE process could be done within the time frame of this opinion.

The question for the experts to consider in the second step was:

If the specified control option is implemented by all broiler producers in the EU that are not currently using it, what will be the resulting percentage reduction (compared to the current level of implementation) in average annual incidence of campylobacteriosis cases in the whole EU population caused by Campylobacter spp. in broiler meat produced from chickens raised in the EU, other things being equal?

The individual experts were asked to quantify their uncertainty about the percentage reduction in the form of a probability distribution, elicited by a version of the Sheffield or SHELF protocol (EFSA, 2014; Oakley and O'Hagan, 2019) adapted to the needs of the current assessment. Each probability distribution was assessed by estimating by a median, lower bound and upper bound, and the two remaining quartiles.

Thereafter, the judgements of the different experts were aggregated for each control option by calculating the equal‐weighted linear pool of the distributions providing the best fits to the individual judgements, using the SHELF software app for multiple experts.5 The linear pool distributions were plotted together with the individual expert distributions (See Appendix D) and discussed in the expert group. Following the discussions, the group of experts decided on a consensus distribution for the effect of each of the eight control options considered.

Finally, the resulting consensus distributions reflecting the uncertainty of the estimated effectiveness of each of the prioritised control options were presented in figures and tables that included uncertainty around each estimate (See Section 3.5).

3. Assessment

3.1. Update on broiler production

The EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (2011) describes the broiler meat production chain in the EU in detail.

Production of poultry meat in the EU increased from ~ 12 million tons in 2008 to ~ 15 million tonnes in 2018, comprising largely broilers (75% in 2008 and 83% in 2018), followed by turkeys (16% in 2008 and 13% in 2018) and ducks (~ 3%). Based on FAO and OECD data from 2017, the EU is the third largest poultry meat producer in the world (US 21.3 million tonnes, followed by China 17.0 million tonnes and EU 15.9 million tonnes, at an estimated world production of 118.1 million tonnes) (Damme et al., 2017).

Export of poultry meat increased from 1.3 million tonnes in 2014 to 1.5 million tonnes in 2017 (Table 4). The level of imported poultry meat remained the same during this time period (0.82 million tonnes in 2014 and 0.83 million tonnes in 2017). The rate of self‐sufficiency was estimated at 104.7% (2017) (AVEC, 2018).6

Table 4.

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross production in the EU | 12,716 | 12,805 | 13,263 | 13,788 | 14,495 | 14,570 | 15,248 | 15,557f |

| Export | 1,324 | 1,311 | 1,361 | 1,508 | 1,679 | 1,671 | 1,780 | n.a. |

| Import | 841 | 791 | 821 | 875 | 902 | 807 | 813 | n.a. |

| Consumption | 12,233 | 12,285 | 12,719 | 13,254 | 13,831 | 13,827 | 14,457 | 14,761b |

| Consumption per head, kg | 21.3 | 21.3 | 22.1 | 22.9 | 23.9 | 24.1 | 25.0a | 25.5a |

n.a.: data not available.

Estimated.

Forecast.

Poultry meat consumption per capita in the EU was 24.1 kg in 2017 (22.1 kg in 2014) with large differences between Member States (e.g. 36.2 kg in Portugal vs. 20.8 kg in Italy). Broiler meat consumption dominated (19.4 kg per head), followed by turkey meat (4.0 kg per head) (Damme et al., 2017).

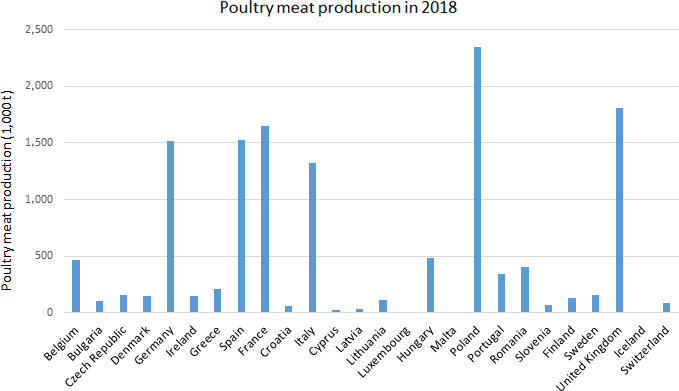

Six Member States account for 71% of the total EU poultry meat production (PL‐16%, UK 13%, FR 11%, ES 11%, DE 10%, IT 9%) (Figure 2) (Eurostat, 2018).8

Figure 2.

Poultry meat production in 2018 (source: Eurostat)5 (Estimated: Croatia; Provisional: Spain, France; Confidential: Estonia, The Netherlands, Austria, Slovakia; Not available: Liechtenstein, Norway)

The EU statistics showed a 14% yearly increase in the overall organic poultry production between 2005 and 2015 (European Commission, 2016).9 An EU‐wide baseline survey on Campylobacter spp. in broiler batches and on broiler carcasses was carried out in 2008 (results are given and analysed in EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2010). Although these data are out of date and pre‐date major Campylobacter control initiatives in many MSs, it is nonetheless the most recent EU‐wide study. The prevalence of Campylobacter spp. colonisation in broiler batches was 71% (determined from caecal contents) and the prevalence of Campylobacter‐contaminated broiler carcasses was 75.8% (based on neck and breast skin samples).

In general, large differences were seen among MSs, with prevalence in broiler batches ranging from 2.0% to 100.0%, and prevalence on broiler carcasses ranging from a 4.9% to 100.0%.

Table 5 shows the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in broiler meat and broilers based on data reported in the annual European Union summary reports on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food‐borne outbreaks. It appears that the Campylobacter spp. prevalence in broilers and on broiler meat has remained quite constant over the years. However, since the number of countries reporting prevalence data changed over the years, the data are not directly comparable.

Table 5.

Campylobacter spp. prevalence (% positive (total tested)) in the EU, 2010–2018

| Year | Campylobacter spp. prevalence % (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh broiler meat at retail | Fresh broiler meat at processing plant | Broilers (flock based) | Reference | |

| 2018 | 37.5 (7,441)a | 26.0 (13,636) | EFSA and ECDC (2019) | |

| 2017 | 37.4 (13,445)a | 12.3 (10,077) | EFSA and ECDC (2018) | |

| 2016 | 36.7 (11,495)a | 27.3 (13,558) | EFSA and ECDC (2017) | |

| 2015 | 59 (3,652) | 37.7 (297) | 15.3 (7,033) | EFSA and ECDC (2016) |

| 2014 | 36.4 (1,570) | 9.9 (1,248) | 27.2 (9,907) | EFSA and ECDC (2015a) |

| 2013 | 25.2 (3,102) | 12.0 (1,904) | 15.1 (n. n.) | EFSA and ECDC (2015b) |

| 2012 | 24.9 (3,495) | 15.8 (2,049) | 13.2 (6,001) | EFSA and ECDC (2014) |

| 2011 | 34 (5,059) | 29.3 (1,260) | 17.8 (6,656) | EFSA and ECDC (2013) |

| 2010 | 22.9 (3,508) | 44.65 (1,010) | 18.2 (9,212) | EFSA and ECDC (2012) |

Not specified in the corresponding report.

3.2. Update on risk factors for Campylobacter spp. in broiler production

There are multiple sources and dissemination routes for Campylobacter spp. on broiler farms. The EFSA ‘Campylobacter in broiler meat’ Opinion (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011) identified several risk factors for Campylobacter spp. in primary production. All those risk factors were reviewed and, when there was new information (since 2011), updated. Factors for which there was more recent information included vertical transmission, slaughter age, season, thinning, Campylobacter‐contaminated drinking water, a previous Campylobacter‐positive flock in the house (carry‐over) and the use of therapeutic antimicrobials for treatment. The remaining risk factors either did not have new information or were discussed in terms of control options (Section 3.3).

3.2.1. Vertical transmission

Vertical transmission is the internal contamination of the egg within the genital tract and before intact shell deposition. As stated in the last EFSA opinion (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011), vertical transmission does not appear to be an important risk factor for broiler colonisation with Campylobacter spp. Recent articles reported no evidence of vertical transmission of Campylobacter spp. from hatching eggs to commercial flocks (Battersby et al., 2016b; Tangkham et al., 2016; Colles et al., 2019).

3.2.2. Slaughter age

Most conventionally housed broilers test Campylobacter‐negative for the first 21 days of rearing (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011). This may be due to maternal antibodies and/or the inability of current testing methods to detect low concentrations of the organism in a small subset of the flock population. Slaughter age is still found among the risk factors identified in epidemiological investigations with conventionally produced birds almost always having higher prevalence and caecal concentration towards the end of the production cycle (Sommer et al., 2013; Legaudaite‐Lydekaitiene et al., 2017; Higham et al., 2018). Higham et al. (2018) showed that age was significantly positively associated with Campylobacter spp.

3.2.3. Season

It is still generally agreed that season is a risk factor with increased prevalence in broilers in the summer months. This was reflected in the EU baseline survey which suggested an increased risk in the period of July–September as compared to January–March (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011). Based on data collected in six EU MSs, the CAMCON project (Sommer et al., 2016a) found that seasonality affected prevalence values and so did the monthly mean temperatures reported in the study. Although the reason for this observation is not clear, and different studies report conflicting findings, enhanced survival of Campylobacter spp. in the farm environment during the warmer months, more water consumption by the birds, heat stress of the birds and/or increased numbers of insects and dust from the neighbouring environment entering the broiler house (facilitated by increased additional ventilation), may be some of the factors contributing to the increased prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in broilers during the warmer months.

3.2.4. Thinning

Thinning or partial depopulation is a practice where a subset of the birds is removed for slaughter and processing, leaving the remaining birds to grow to the required size (Allen et al., 2008). Sometimes several rounds of thinning are performed in a flock (Millman et al., 2017). The 2011 EFSA Opinion highlighted thinning as a major risk factor and this is supported by research since then. Lawes et al. (2012) and Millman et al. (2017) reported thinning as a risk factor for Campylobacter spp. infection as it breaches the biosecurity barrier and catching crews, cages, modules and trucks visit multiple farms. Catching crews bring Campylobacter spp. into the house on their boots, forklift trucks or broiler harvester machines, trolley wheels, crates etc. (Ellis‐Iversen et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2016; Georgiev et al., 2017). In addition to breaching biosecurity, thinning also stresses the birds and the presence of stress hormones in the gastrointestinal tract may promote the growth, proliferation and virulence of Campylobacter spp. (Aroori et al., 2014). Thus, Campylobacter spp. introduced at thinning, spread rapidly throughout the flock reaching levels in the birds of up to 108 cells per gram of caecal matter within 4–5 days after thinning (Koolman et al., 2014). In a recent investigation, Higham et al. (2018) confirmed previous findings and showed that thinned houses had a 309% increase in the odds of being highly contaminated and concluded that further investigations are required to elucidate farm and individual factors related to thinning (Higham et al., 2018).

3.2.5. Campylobacter spp. contaminated drinking water

Contaminated water was previously considered an important source of Campylobacter spp. on farms (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011). Campylobacter spp. are commonly found in surface water on farms (Mughini‐Gras et al., 2016) and, if used without proper treatment, water may serve as a vehicle of transmission (Jonsson et al., 2012; Agunos et al., 2014; Allain et al., 2014; Torralbo et al., 2014; Borck Høg et al., 2016).

3.2.6. A previous Campylobacter‐positive flock in the house (carry‐over)

When a flock is Campylobacter‐positive the broiler house and surrounding environment is often heavily contaminated and, if not cleaned and disinfected properly between flocks, a previous positive flock will become an important source of Campylobacter spp. for the new flock (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2011). More recent studies also support this conclusion. Damjanova et al. (2011) and Battersby et al. (2017) both demonstrated that inadequate cleaning and disinfection was a risk factor in the spread of Campylobacter spp. from one flock to the next. Other studies detected the same genotypes of Campylobacter spp. in broiler house samples before or during flock placement (Allen et al., 2011; Damjanova et al., 2011). Broiler house surroundings such as the tarmac apron, anteroom, house door, feeders, drinkers, walls, columns, barriers and bird scales may act as a source of direct or indirect infection resulting in carryover of persistent genotypes through several rearing cycles (Battersby et al., 2016b). The failure to eliminate Campylobacter spp. at these sites between flocks has been attributed to a range of factors including the design of feeders and drinkers, insufficient down time, a lack of knowledge or utilisation of proper cleaning methods and bacterial resistance to the disinfectants used (Agunos et al., 2014).

3.2.7. The use of therapeutic antimicrobials

The EFSA 2011 Opinion reported conflicting results on the effect of antibiotics on Campylobacter spp. carriage and shedding, with Herman et al. (2003) observing no effect while Refregier‐Petton et al. (2001) concluded that administering antibiotics to the birds decreased the risk of colonisation with this organism. Similar results were reported by Allain et al. (2014). These conflicting results may be due to the resistance of Campylobacter spp. to the antimicrobial administered or that Campylobacter spp. was introduced after the treatment. More recent research examining the effect of antibiotic treatments on the microbiome of the broiler gastrointestinal tract is similarly inconclusive (Allen and Stanton, 2014; Mancabelli et al., 2016). The use of antimicrobials to reduce Campylobacter spp. carriage and shedding may induce resistance in bacteria colonising the birds and is contrary to current EU policy to reduce antibiotic usage in animal husbandry. Therefore, it is not be considered further in this opinion.

3.2.8. Concluding remarks

New information was published since the EFSA 2011 Opinion that provides additional evidence indicating slaughter age, season, thinning, contaminated drinking water and carry‐over from a previous flock are still important risk factors for Campylobacter spp. colonisation of a broiler flock. Vertical transmission does not seem to be a relevant risk factor and the results on the use of antimicrobials are still inconclusive.

3.3. Control options to reduce the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in broilers

In the following section, the updated knowledge on the expected effect of the individual biosecurity options that can be implemented at primary production level to control for the identified risk factor is summarised. In Section 3.3.1, the results of the control options associated with the risk factors for which PAF could be calculated are presented. In Section 3.3.2, the observed effects of the control options associated with the risk factors for which PAF could not be calculated are provided.

3.3.1. Calculation of population attributable fraction for control options